Government response: Consolidation of defined benefit pension schemes

Updated 17 July 2023

Ministerial Foreword

10 million people rely on defined benefit (DB) pension schemes for a substantial proportion of their retirement income. Although many schemes are now closed they hold £1.7 trillion worth of funds that I want to see working for members, employers and the economy and I welcome innovation in the DB landscape that will increase protection for members whilst also supporting wider economic initiatives.

For sponsors for whom insurance buyout is out of reach, Superfunds have the potential to improve the likelihood of members getting their benefits in full, whilst providing employers with a new, affordable way to manage their legacy pension liabilities.

Superfunds are also ideally placed with the benefits of scale, significant new capital and a well-diversified portfolio to contribute to greater investment in assets that support the UK as a whole. They align with wider Government initiatives designed to stimulate economic growth and will provide access to new sources of capital investment for UK firms, major infrastructure projects, other illiquid type investments, and fresh finance for sustainable technology, areas which up to now have suffered with under investment.

This consultation response has been developed as part of a broader collaboration with stakeholders across government and the pensions and insurance sector, and I am grateful for the time and thought so many have invested in this project. Work will now begin to finesse the detail required to enable us to develop and progress the permanent legislative regime.

The vast majority of the responses to the consultation were supportive of the proposals and keen to see Superfunds up, running and regulated in the UK. Setting up this system will ensure that Superfunds operate on a secure footing and support scheme members so they can confident that their position is being enhanced by this form of consolidation.

I am pleased that at least one Superfund, Clara Pensions, has met TPR’s key expectations but I want to see this market develop further, and soon. I hope that reiterating the Government’s support for Superfunds, alongside TPR’s interim review, and committing to having a permanent regulated regime, as soon as parliamentary time allows, will help to maintain momentum and investor confidence and cement the legacy of this important innovation.

The DWP has published a number of documents today, all designed to drive better outcomes for pension savers. These are all part of a wider government agenda to improve opportunity for investment in alternative assets including in high growth businesses and improve saver outcomes. We believe that a higher-allocation to high-growth businesses, as part of a balanced portfolio, can increase overall returns for pensions savers leading to better outcomes in retirement. In addition, we want to ensure that our high-growth businesses of tomorrow can access the capital they need to start up, scale up and list in the UK. DWP have been working closely with HMT on this wider package which was set out by the Chancellor in his Mansion House speech.

Laura Trott MP

Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Pensions

Introduction

1. The defined benefit (DB) sector has changed significantly over the years, both in terms of the number of schemes and members. Most pension schemes being set up now are defined contribution schemes (DC), while the vast majority of DB schemes are either closed to new members or further accrual. For closed schemes the time horizon until the pensions have to be paid contracts. Schemes rely on a combination of investment returns and support from the sponsoring employer to meet the pension promise and to pay the benefits Investments do not always perform as well as expected or liabilities are higher than planned for, and in these circumstances, employers need to pay additional contributions. This relies on the employer covenant – the ability and willingness of the employer to support the scheme now, and in the future – which is far from guaranteed.

2. Since the 2018 consultation the overall funding position of DB schemes has substantially improved, to the point where the estimated total shortfall of all schemes in deficit on the PPF s179 basis is now a tenth of what it was 2 years ago. However, whilst the overall funding position of DB schemes has substantially improved it remains volatile. The S179 aggregate deficit was £86Bn in Dec 2020, moving to a surplus of £129Bn in Dec 21 and recent market changes have created a surplus of £359.3bn as of Mar 23.

3. Whilst aggregate scheme funding has improved markedly members benefits are still at risk, even where a scheme is fully funded on the “Statutory Funding Objective” basis. If the employer of such a scheme were to become insolvent, it is unlikely that there would be sufficient resources in the scheme to secure full benefits for members with an insurer, as sponsors are not required to fund their schemes to full insurance buyout levels. In the event of an insolvency, if the scheme has sufficient resources, it would buy out benefits at a level greater than PPF compensation, but members would still suffer a loss. This is the risk from which Superfunds can help to protect members, as they provide a better prospect of delivering full benefits than the exporting scheme.

4. DB scheme funding has improved significantly in recent years and is very different to when we consulted. Despite this the need for Superfunds still exists. Recently we have seen Covid 19, changes brought about by globalisation, other significant world events. The buyout market is also not fundamentally interested in schemes that cannot afford their products and also has a natural ceiling to the value of schemes that can effect buy out in any calendar year. Buy out and Buy in volumes have averaged around £25-30bn pa over the last 5 years and capacity is estimated by some to be circa £45bn pa and the increases we have seen in scheme funding levels, means the potential demand is expected to be significantly higher than this.

5. Superfunds provide a real opportunity to take significant risk to members out of the system and increase their likelihood of receiving full benefits. A Superfund has the potential to get new additional funding to support the scheme in the short term that might not otherwise be available. An uncertain covenant is replaced with a known and accessible capital buffer provided by investors. The combination of additional scheme funding, capital buffer, benefits of scale and improved governance increases the probability of members getting their benefits in full. In return for their investment and expertise the Superfund provider will be expected to make a profit but not at the detriment of scheme members.

6. Employers, members and the wider economy will be helped by Superfunds. For employers, Superfunds provide an option for managing their legacy liabilities. There is an opportunity for them to draw a line under the uncertainty and potential drag of long-term legacy liabilities. Legacy DB schemes can prove to be a serious and unpredictable cost burden for employers over the long term, which can be particularly burdensome for smaller companies. The main advantage is that once a pension scheme is moved into a Superfund, employers are freed of their obligations to the scheme. This allows them to then focus on their core business, potentially benefitting the wider UK economy.

7. Superfunds are likely to invest in a more productive way than many closed DB schemes. Studies have shown that larger schemes invest in alternatives such as infrastructure, property and private equity, moving away from fixed-income assets such as bonds. Superfunds benefit not only from scale achieved through consolidation but through the additional support delivered by the entry price paid by the employer, and a significant capital buffer provided by the investors. As with other DB schemes we are not specifying the long-term objective for Superfunds. Those that choose to run on for some time before securing laibiilities will be in a good position to take advantage of patient capital. Even Superfunds developed with the aim of shepherding schemes to the insurance market are expected to invest more productively because of their size, expertise and focus on scheme management.

8. Superfunds may also be able to help in situations where an employer has become insolvent, but the scheme itself is funded above PPF levels. In the current system members in such a situation would still be likely to suffer losses relative to full scheme benefits.Very few schemes are funded to a level which would enable them to buyout the full value of member benefits in the insurance sector. In these instances members benefits are compromised before being taken on by the insurer. In these ‘PPF+’ cases, a Superfund may be able to offer a good prospect of paying benefits in full, despite there being insufficient funds to secure these benefits on the insurance market, with members continuing to enjoy the security of PPF protection.

9. Our proposals are designed to attract billions of pounds of capital into the pensions industry. Existing Superfund providers have already announced that they have secured significant investment from UK and Overseas investors, and we expect this to continue as the Superfund market develops. We also expect significant sums will be generated from employers and parent group companies based in the UK and abroad, that will be willing to pay the significant entry premium to release their long-term pension liability. This new capital will be used to accelerate scheme funding and improve the security of member benefits.

10. We believe our approach will help to ensure that the capital regime for Superfunds remains affordable for some employers, for whom the prospect of buying out is simply unaffordable now or in the foreseeable future. For many schemes, a Superfund’s combination of a significant financial buffer fund, economies of scale, professional governance and access to wider and more diverse investment opportunities, offers a substantial improvement on their current situation.

Proposed Regime - Key Features

Schemes in Scope

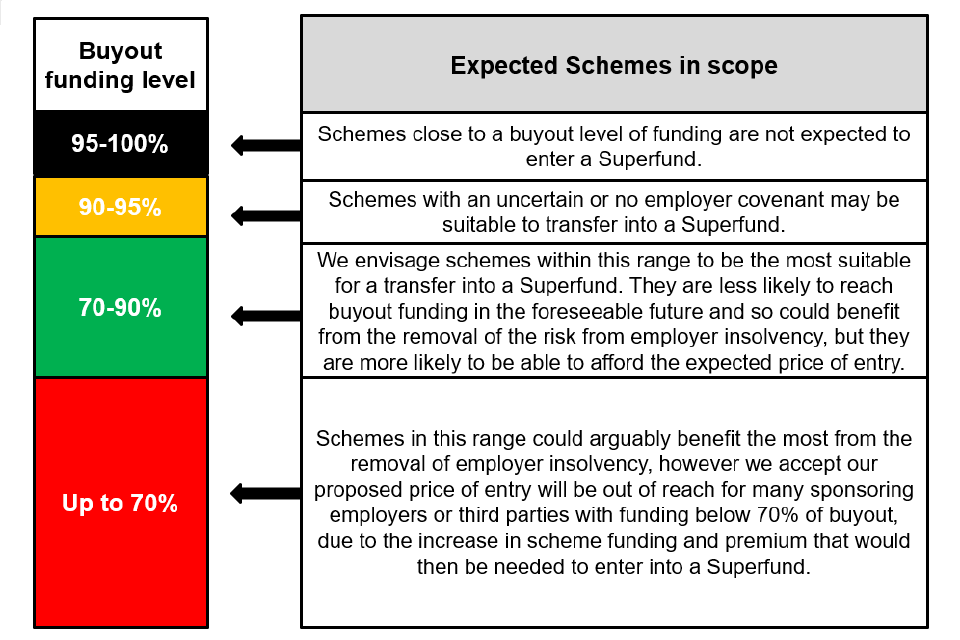

11. In terms of which schemes the Government is hoping Superfunds will appeal to, we are trying to reach those schemes that cannot yet afford or access full insurance buyout, but are also suitably funded to avoid the introduction of too much risk into the regime. The schemes we realistically think the policy could help are shown below, based on scheme funding level prior to receiving the capital injection from the employer (or the wider corporate group) and Superfund. As well as the funding level, there are other factors determining whether a Superfund is a suitable destination for a given scheme, including the size of the scheme and its employer covenant.

Size

12. Although we would like Superfunds to help smaller schemes, we understand that in the early phase of the evolution of commercial consolidators, for a Superfund to be viable, it needs to get to scale quickly and there is more value in on-boarding larger schemes initially. Therefore, we think it is unlikely that Superfunds will be targeting very small schemes at the outset. This does not however rule out the industry developing innovative financial products that may appeal to these schemes.

13. It’s important that the future regulatory framework for Superfunds can enable them to reach the scale needed to allow them to be successful. An excessively restrictive regime, which limits Superfunds to a small tranche of the best funded schemes, would result in a very small Superfund market. This would limit the opportunity to bring more new capital into the pension system and would be of minimal added value to the wider UK economy. A large and vibrant Superfund market however has the potential to introduce significant pools of capital into the UK economy. We believe that this approach would be a positive step from a wider public finance perspective.

Superfund Definition

14. We will look to develop the definition to account for DB schemes where the ceding employer’s link is severed or substantially altered either on entry to a Superfund or at some point in the future. Further detail of these proposals can be found in paragraphs 44 – 48, in the response to the first question in the consultation.

15. We have seen, and expect to continue to see, the market developing in a way that will bring differing capital backed solutions. We want to ensure our definition captures appropriate models which look to sever the covenant while allowing the market to innovate other models in parallel.We expect a more expanded, detailed definition will be worked up with industry input in time for the consultation on the regulations. For now though we can say that a Superfund will have at it’s core some, or all of, the following characteristics:

- is an occupational pension scheme set up for the purposes of effecting consolidation of DB pension schemes’ liabilities;

- the link to a ceding employer is severed or substantially altered following the transfer to or by the involvement of the Superfund;

- the ‘covenant’ is replaced by a capital buffer provided through external investment that sits within the Superfund structure. The capital buffer in the context of Superfunds is the money ringfenced by the employer and investors to replace the covenant for the scheme; and,

- there is a mechanism to enable returns to be payable to persons other than members or service providers.

Structure

The key structural question for Superfunds is whether to divide the schemes between multiple standalone sections, with ringfenced capital requirements, or to ‘co-mingle’, meaning that all incoming schemes will be pooled together. We recognise that there are advantages for both approaches. A segregated approach could reduce the overall risk to scheme members and the PPF, and it will lessen the impact of ‘cross-subsidisation’ of weaker funded schemes. Alternatively, a co-mingled Superfund will benefit from economies of scale with the consolidation of schemes into a single pool.

Each approach introduces risks and complexities from a regulatory and legal perspective. For a sectionalised Superfund, the effective application of intervention triggers could be complex, particularly where multiple sections are underperforming simultaneously. With a co-mingled Superfund, questions may be raised about fairness if weaker funded – often less mature - schemes are ‘subsidised’ by schemes with strong funding levels. We do not consider it conducive to a successful and innovative Superfund market, to restrict providers within a single structure or approach, and therefore we will not mandate that a Superfund is either sectionalised or co-mingled. The structure of a given Superfund will be a key consideration for ceding trustees as they assess the benefits and risks of consolidation.

Supervision and Authorisation

16. The intention is that Superfunds will be authorised and supervised by TPR. Supervision and authorisation will include checks to ensure that Superfunds are corporate bodies registered in the UK and fall under the jurisdiction of UK regulators and courts.

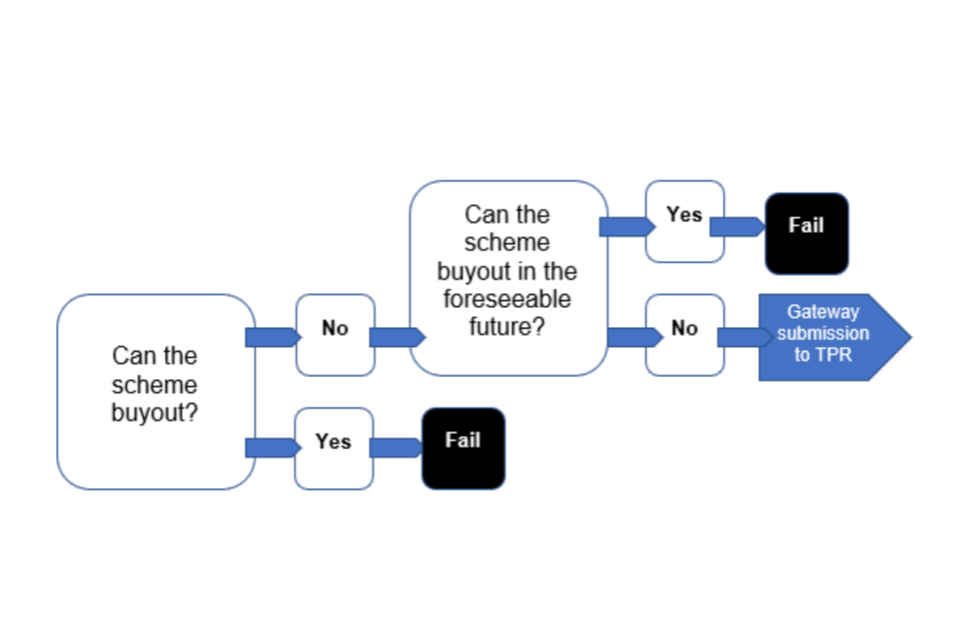

17. A key element of the authorisation process will be a regulatory Gateway. This gateway will ensure pension schemes that can afford to secure members’benefits with insurers do so. Future legislation will also ensure that trustees have taken appropriate legal, actuarial, investment and covenant advice when determining the suitability of consolidation into a Superfund.

18. Since June 2020 Superfunds have been governed by an interim regime overseen by TPR. This interim regime is currently under review and we are keen to learn any lessons which can be built into the permanent regime. Further work will be required to establish the processes and timeframe for Superfunds that exist under TPR’s interim guidance to be authorised under, and transition to, the permanent regime although we have worked closely with TPR on their interim regime and are confident that the direction of travel of both are well aligned.

Governance

19. A key principle of the Superfund policy is to improve the likelihood that members will receive full benefits and as part of this the Superfund regulatory framework needs to ensure that systems and processes are in place to ensure effective governance and to maximise this aim by reducing the risk inherent in the system. The bulk of our consultation focussed on topics that are designed to reduce the risk of failure. As stated previously whilst a lot of the finer detail is still to be clarified there are some broad principles we can state now:

- risk - We consider an acceptable level of risk to be a 2% chance of a scheme within a Superfund not paying full benefits and subsequent modelling by the Government Actuary’s Department along these lines allows for an entry price into a Superfund approximately 10% below the price of insurance buyout. The frameworks will also need to move in a consistent manner to account for the changes in the reform of Solvency II. We will require Superfunds to have a monitored risk of failure and believe that an annual assessment, which allows for an appropriate level of risk, can achieve this. The annual assessment will be based on an appropriately prudent set of Technical Provisions (TPs) and a 1 year 1-in-100 Value-at-Risk (VaR) capital requirement. The success of a Superfund will be largely determined by the investment strategy and in particular level of risk being taken. These factors will inform the capital requirements and calibration of the Superfund regulatory framework. There will be a requirement for Superfunds to make regular public disclosures in respect of their financial position, governance, performance, and risk management. A risk management framework is needed to require commercial consolidators to demonstrate how the level of risk they are taking is proportionate, how they mitigate these risks to protect scheme members, and action to take when risk limits are breached.

- intervention triggers - The regime will impose intervention triggers. The triggers will control profit taking, recapitalisation/taking on new schemes, transfer of the capital buffer and where necessary, enforce the wind up of a scheme or section. The triggers will be based on TPs plus a multiple of the 1-in-100 VaR capital requirement depending on the level of intervention, except for the winding-up trigger that will be based on PPF liabilities and TPR will be provided with the required powers to intervene and enforce these triggers.

- profit trigger - Superfunds rely on private investors for part of their security, and the investors need to be rewarded if the scheme is successful in creating value. But profits can only be taken once additional value has been created, and members benefits are more secure. There will be rigorous controls on profit taking, so that members benefits are protected. The basic principle is that profit would only be taken from the scheme when the value of the assets increased by a specified margin above the initial authorisation level of funding for the scheme – so after an additional capital buffer providing member security had been generated. We will define the precise parameters for profit taking in Regulations, but it would be set so as not put future benefits at risk.

- the profit trigger will be implemented only allowing extraction when assets are at a suitably prudent level above TPs. In cases where a segregated model is in place, the Superfund will only be able to distribute the profits from a section only after that section’s assets exceed TPs and a percentage over the authorisation capital requirement or transfer of a scheme/Superfund to an insurer occurs. Permitting Superfunds to extract profit above a certain level of capitalisation allows for the commercial viability of the funds. The profit requirement will be based on an assessment of the long-term sustainability of the annual balance sheet approach that would allow Superfunds to pay profits on an annual basis. Long-term modelling has been used to calibrate the approach although the regime will be based on an annual assessment of funding and capitalisation.

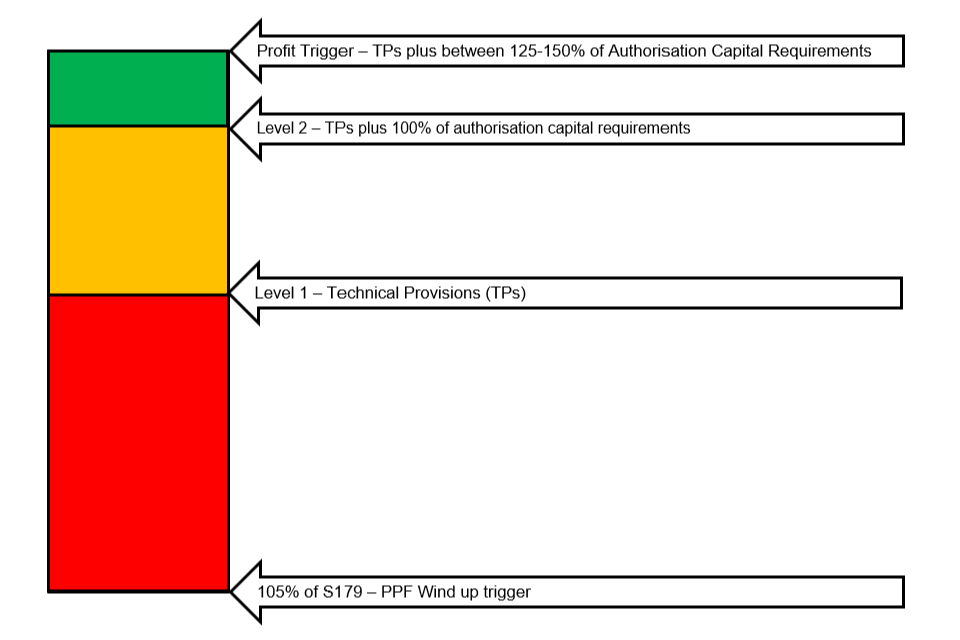

20. The security of members’ benefits will be supported not only by the absolute level of financial requirements, but by a ladder of intervention which will ensure these requirements are supervised and enforced. In addition to the profit trigger, three further triggers will be used.

- a ‘Level 2’ trigger will be set equivalent to the authorisation level requirements for an individual section or Superfund (i.e. sufficient assets to meet TPs plus 100% of the authorisation capital requirement). When funding falls below the requirements for initial authorisation, the ‘Level 2’ trigger is breached. At this point the section or Superfund is unable to take on new business but will be allowed to continue to run on. For sectionalised Superfunds, this only applies to an individual section. If the Superfund manages to return to the required authorisation funding levels it will then be permitted to resume taking on new business as normal.

- a Level 1 trigger will be set where funding and capitalisation falls below a certain level. At this point any remaining funds in the Superfund or individual section’s capital buffer are tipped into the scheme , under full control of the Superfund Trustees, and the section or Superfund would be allowed to then run on without a substantive sponsor or to transfer liabilities to another entity, if such a transfer is available.

- the wind up trigger will be determined using a PPF (s179 or s143, if more appropriate, of Pensions Act 2004) valuation of pension liabilities. The trigger will be set above PPF level benefits to protect members form the loss of some of their pension promise in situations they receive compensation formt he PPF.There will be some flexibility for amendment when appropriate and with TPR agreement (similar to TPRs current interim guidance).

21. Superfunds will have the opportunity, within certain limits, to take corrective action if any triggers are breached. The diagram below demonstrates where we envision the intervention and profit triggers will be set. These are discussed in greater detail from paragraph 105 onwards.

22. Long Term Objective - Having considered the responses to the consultation carefully, we do not think it would be appropriate for legislation to mandate that Superfunds should be required to target buyout with an insurer. We believe this requirement would threaten the viability of the Superfund market by preventing innovation and variety amongst the prospective market offerings. A requirement to buyout through the bulk annuity market does not apply to the wider DB pension market and could have serious commercial implications.

23. Superfunds will be expected to make their long-term objective for individual schemes they intend to onboard abundantly clear, so that trustees considering moving into a Superfund understand whether the transfer meets their fiduciary duties. This will be part of the due diligence process, which will need to be undergone as part of any gateway process.

Financial Adequacy

24. The financial sustainability and capital adequacy will be the most critical part of the new legislative framework. Government will have to strike the right balance between improving member security, keeping the entry price affordable for employers unable to afford an insurance buyout in the foreseeable future, whilst developing a regime commercially viable for providers and investors. This will be important for ensuring that Superfunds can make a sustainable contribution to achieving the Government’s policy goals.

25. Whilst we accept that there will be more risk in the Superfund regime than full insurance buyout, the Government’s current risk appetite for Superfund failure remains low. The proposed Superfund regime is designed to retain an adequate level of prudence, albeit this will need to be maintained below the level applicable under the Solvency II framework for insurance companies, which provide a fully guaranteed product for members’ pensions. This recognises a comparatively greater appetite for Superfund failure, consistent with the difference between risk profiles in pensions and insurance. Whilst we accept that Superfunds are not standard DB schemes they are still pension schemes and will have their financial requirements set under a pensions regime. Whilst there are elements of the Solvency II regime that can be incorporated to reduce risk (such as use of Value at Risk metrics) we will not be asking schemes to capitalise in line with Solvency II.

26. We therefore propose the following financial requirements under an annual balance sheet approach:

- TPs based on a best estimate approach to cash-flow projection and a discount rate based on a prudent assessment of the expected returns on an appropriate low risk strategy similar in nature to a “low dependency investment strategy”. See paragraph 89 - 90. In line with the approach adopted by TPR in its interim requirements, an explicit longevity reserve as a margin for prudence, as well as a reasonable reserve for member expenses, will be included for this purpose in the TPs.

Consultation on Superfunds

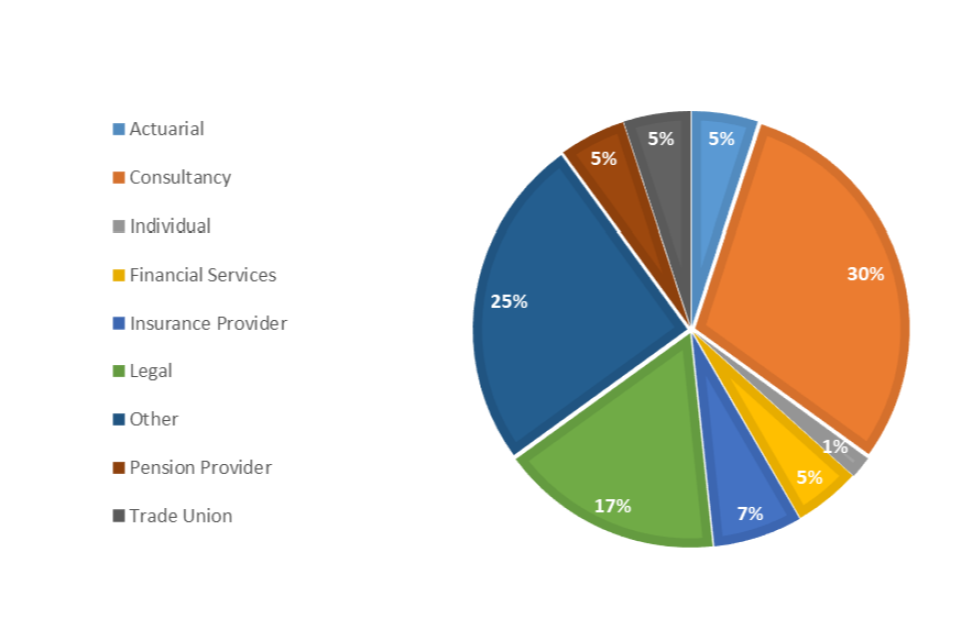

27. On 7 December 2018 we published a consultation: ‘Consolidation of Defined Benefit Schemes’. We set out our thinking on how Superfunds would operate and asked for views on the practicalities of our approach. In total we received 60 responses from a wide range of organisations and individuals (see Figure 1) highlighting the level of interest in this new form of consolidation in the UK. In addition, we held three industry roundtables, which focused on a future gateway for Superfund entry as well as governance and financial sustainability requirements.

28. A list of organisations that attended these roundtables can be found in Annex A and we were grateful for the insightful and informed contributions to the debate. We also appreciate the quantity and the quality of the responses we received. Most respondents to our consultation recognised the benefits Superfunds can bring and the need for bespoke legislation to authorise and supervise Superfunds to ensure they operate safely.

Figure 1

29. Following the publication of the consultation we have worked closely with a range of stakeholders from across government, the pension and insurance industry to develop proposals for an effective regulatory and authorisation regime. This discussion has focussed primarily on:

- the size of the capital buffer that would need to be provided to replace the employer covenant, and protect members’ benefits

- the nature of the rules governing the control of investment risk

- the nature and extent of rules governing Superfund structure, including whether they should have to target buyout as a long-term objective, and when and how profit can be taken

- the criteria that have to be met to enter a Superfund, including rules to avoid giving some sponsors a choice between a Superfund and insurance buyout (the Gateway)

- whether there are wider economic risks from the Superfund approach which need to be mitigated

30. Many of the responses we received focussed on the extent to which our proposals could balance three competing interests: providing security to members’ benefits, keeping the entry price affordable for employers, and providing a sufficient return on capital to ensure the Superfund concept is commercially viable.

31. Whilst there was broad agreement that robust authorisation and ongoing regulatory oversight was needed, opinion on what form this should take varied considerably. The majority of respondents from the pensions industry argued that the risks Superfunds present are best controlled by a strengthened pensions regime. The majority of respondents from the insurance sector wanted an insurance-based regime, with some suggesting levels of security that would only be marginally below the existing insurance buyout regime would be appropriate.

32. The Government considers that a Superfund is an occupational pension scheme. If Superfunds were required to adopt Solvency II capital requirements in their entirety, we would simply be recreating insurance. We were also clear at consultation that our intention was not to simply create a cheap form of insurance buyout, that there should be clear blue water between the two, and that employers should never have a choice between the “gold standard” for security of insurance, and a weaker, cheaper option; where insurance buyout is achievable in the foreseeable future. We remain committed to this approach.

33. In developing our proposals, we have looked closely at how effectively they deliver our original policy objectives. These were helping schemes and employers where members’ benefits are at risk due to the risk of future employer insolvency, and where an insurance buyout now or in the foreseeable future is unlikely. The regime we are proposing is designed to ensure that members can have confidence in Superfunds, should their pension be transferred into one in the future. We are aware that there are complex technical issues to be worked through here, so we will continue to engage with stakeholders as the fine detail of the new regime is developed.

34. While developing these proposals we have had ongoing contacts with relevant Government Departments and Regulators who have been informing our work. This has been especially important due to the growing and developing nature of this emergent market.

35. In June 2020 the Pension Regulator published their interim regime for Superfunds and this is currently under review. This review is taking on lessons learned from its initial operation as well as the changing circumstances in the market. It will include the approach on profit extraction, the discount rate to enable Superfunds to operate more competitively, the Gateway and improving the assessment process. We have been working closely with TPR in reviewing the interim regime to better suit today’s market environment and direction of travel for the legislation. We will ensure that the transition from the interim to the permanent regime is managed in a safe, effective and secure manner ensuring that members’ benefits and the PPF are not put at undue risk. The requirements set out in this consultation document set a clear direction of travel for the future legislative requirements. After a transition period, the details of which will be developed in collaboration with interested parties, Superfunds will be required to comply with the legislative framework once it has come into force in order to continue to accept new transfers in.

36. We have also had detailed discussions within Government and with financial regulators about the potential risks to the wider economy of insurance companies participating in the Superfund market. The Government is keen that the insurance industry should be able to participate in the Superfund market. They have great experience in pensions risk transfer arrangements, and we would welcome their experience, expertise and innovation. It is ,however, important that any risks generated by such participation, to existing policyholders of insurance groups or to wider financial stability, be considered and if necessary mitigated by the existing regulatory authortities for the insurance sector, in pursuit of their statutory objectives.

Consultation responses

Defining Superfunds

Question 1: Whether these characteristics were wide enough to define a Superfund?

37. The consultation set out a number of key differences between Superfunds and more ‘traditional’ DB pension schemes based on the Superfund models that had started to emerge in the DB market. The consultation initially proposed the following defining features:

- a Superfund is, or contains, an occupational pension scheme set up for the purposes of effecting consolidation of DB pension schemes’ liabilities;

- a transferring scheme’s link to a ceding employer is severed or substantially altered following the transfer to or by the involvement of the Superfund;

- the ‘covenant’ is replaced by a capital buffer provided through external investment that sits within the Superfund structure; and,

- there is a mechanism to enable returns to be payable to persons other than members or service providers.

38. This definition was broadly accepted by most respondents.

The Government’s response

39. The market has continued to develop in the intervening period after the consultation and we are now seeing commercial models looking to come to market offering different types of ‘innovative’ capital backed solutions that would provide DB pension schemes with new ways of enhancing members’ benefit security.

40. It is in this context that we believe the scope of the definition for Superfunds needs to be sufficiently broad to accommodate these and any future developments ensuring a level playing field as solutions develop. Expanding the scope allows us to future proof our definition, rather than having a narrower focus that runs the risk of becoming more limited in use as the market develops. It would also allow us a means to consider how we manage other scheme structures, such as those schemes without a substantive sponsor (SWOSS).

41. We will continue to consider this thinking further in time for the primary legislation for Superfunds and are aware that TPR are considering these issues and plan to publish guidance on new models later this year. Our intention is to have the general requirement for TPR’s authorisation established in the primary legislation. This would probably be supplemented by carve outs in the subsequent secondary legislation, whether in part or in full, for those forms of consolidation or other models we do not think will benefit from being regulated under TPR’s Superfund regime.

42. This is an evolving picture and the specifics of the definition will be worked up in time for the consultation on the regulations, but we will look to develop the definition to account for DB schemes where the ceding employer’s link is severed or substantially altered either on entry to a Superfund or at some point in the future.

Criteria

Questions 3 & 4: Whether these were the right criteria, and whether they should apply to the sections rather than an overarching entity.

43. The consultation proposed a number of criteria (the “authorisation criteria”) which the Superfund would need to meet in order to become authorised. These were that the Superfund:

- can be effectively supervised

- is run by fit and proper persons

- has effective administration, governance and investment arrangements

- is financially sustainable

- has contingency plans in place to protect members

44. While there was broad support for these criteria, a number of respondents had other suggestions.

The Government’s response

45. In the period since consultation, as the policy discussion around Superfunds has developed and considering the broad support of respondents, we remain satisfied by the proposed authorisation criteria, which were incorporated into TPR’s interim guidance for Superfunds and we propose replicating this in forthcoming legislation.

The criteria will apply to the Superfund as a whole, rather than to individual sections in a segregated model. However, it is worth noting that each section will be required to individually meet capital adequacy requirements, and this is discussed in greater depth below.

Supervisability

Questions 5 & 6: Will these restrictions ensure that a Superfund can be effectively supervised, and should the corporate entities of Superfunds be permitted to be established as partnerships, or should they be required to be set up as a UK limited company?

46. The consultation proposed a number of requirements regarding the corporate structure of Superfunds to drive transparency and ensure that Superfund models are compatible with regulatory supervision. The requirements proposed were that the Superfund’s corporate entity be established as a body corporate with its head office and registered office maintained in the United Kingdom. In addition, we also asked whether partnership arrangements should be permitted within a Superfund’s structure.

47. The vast majority of responses agreed that an entity establishing a Superfund should be required to be a body corporate, with its head office and registered office maintained in the UK. The main reasons for this focussed around TPR’s regulatory reach and its ability to use enforcement powers.

48. On the use of partnerships in Superfund structures, a number of respondents raised concerns. The concerns largely focused around partnerships being less transparent than other corporate arrangements.

The Government’s response

49. We propose legislating to make it a requirement that an entity establishing a Superfund must be a body corporate with its head office and registered office maintained in the United Kingdom (UK). We do not propose that other entities within a Superfund group be required to be body corporates, (i.e. partnerships would be allowed) but that they must be established in such a way so as to fall under the jurisdiction of UK regulators and courts.

50. We propose to legislate to make it a requirement that a Superfund is to be supervised by TPR if certain conditions (to be set out in secondary legislation) are satisfied. It is anticipated that the conditions would include matters such as the manner in which the Superfund is organised, whether it is a member of a corporate group, and any close links it has to other entities.

51. This will likely be similar to those matters set out in section 4F of Schedule 6 of FSMA 2000 for PRA regulated firms[footnote 1].

52. Since consultation HMT have also announced a review of the treatment of Superfunds for tax purposes. Discussions on the detail of possible structures will need to ensure the pensions tax system applies appropriately with respect to Superfunds.

Fit and proper

Questions 7-10: Who should be subject to the fit and proper persons requirement, its scope, and the powers TPR would need to establish that they have been met?

53. The main aim of the fit and proper persons requirement is to ensure that those in a position to influence or directly impact member outcomes act with honesty, integrity and have the skills and knowledge to occupy the positions that they hold. As part of the fit and proper persons requirement, the collective competence of both the trustee and executive board will also be assessed to ensure that they have the right mix of skills and knowledge appropriate to the Superfund’s business model. The fit and proper persons requirement seek to mirror requirements under the Senior Managers and Certification Regime (SMCR), therefore furthering the Government’s wider ambition to increase individual accountability for actions and conduct.

54. The vast majority of responses were supportive of introducing some form of fit and proper test. A commonly raised concern centred around ensuring that any requirement captures an appropriate breadth of individuals and responsibilities which are involved with or apply to Superfunds.

The Government’s response

55. We intend to introduce a fit and proper persons requirement in legislation as part of authorisation and ongoing supervision. It is proposed that the fit and proper persons requirement will mirror SMCR but be adjusted to reflect a pensions context. This will include introducing ‘key functions’ and certain ‘prescribed responsibilities’. TPR will have the power to take action should an individual seeking to hold a key function not meet the requirements.

56. Superfunds must conduct due diligence on whether an individual would likely pass fit and proper requirements, taking into account TPR codes of practice and guidance. TPR must be satisfied that the individual acts with honesty and integrity and that they have the appropriate skills and knowledge (“competence”).

57. A Superfund will be required to produce and maintain a statement of responsibilities for each key function and submit this when applying for approval or when there is a significant change in an individual’s responsibilities. A Superfund will also be required to produce and maintain a responsibilities map, setting out its management and governance arrangements, and submit this as part of its application to become authorised and subsequent to any changes made. Other features that are not listed above may be included in the future fit and proper persons requirement and processes.

Questions 11-14: Whether it would be beneficial to introduce standards of conduct for Superfund corporate boards to complement the fiduciary duties placed on Superfund trustee boards.

58. There was a split reaction to this proposal with some respondents questioning whether it was necessary given provisions elsewhere. Furthermore, some wondered whether this would prove problematic with a corporate board’s obligation to its shareholders. Some also thought that more simply it could end up duplicating trustee powers. Where respondents did agree with this idea, the general view was that additional requirements should be considered in the context of existing trust and corporate law. A small minority thought additional requirements may be needed as Superfunds were new entities set to achieve significant scale.

The Government’s response

59. We will introduce a set of conduct requirements and a certification regime with an exemption for ancillary staff. These requirements will include - but will not be limited to the following:

- approval for a key function will not be transferable; if an individual moved to another Superfund they would have to reapply;

- an individual may hold more than one key function but must be approved for each function they hold;

- TPR may interview a candidate as part of fit and proper requirements;

- a ‘statement of responsibilities’ must be kept up to date; and, *statements of responsibilities and the responsibilities map must be submitted in a method and format determined by TPR.

Governance

Questions 15-18: A number of questions were asked regarding the makeup, constitution and levels of member representation on Superfund trustee boards?

60. The majority of respondents recognised the challenges with ensuring adequate member representation in a Superfund structure made up of different schemes from different industries. Many also argued that one of the key benefits of Superfunds was the improved stewardship and governance they offer, and that requirements to have member nominated trustees could potentially undo one of these key benefits.

The Government’s response

61. We recognise the importance of ensuring that members’ interests and views are properly taken into account within a Superfund. We are not convinced that member nominated trustees (MNTs) or member nominated directors (MND’s) are appropriate in a Superfund context. After carefully looking at this issue in light of the consultation responses, we believe the issues are essentially no different to DB master trusts and other industry-wide DB pension schemes or other large schemes without MNT/MNDs.

62. We want to avoid introducing a process that creates barriers that do not exist elsewhere and will engage with industry to ensure systems replicate what already exists in similar schemes. In developing a superfund regulation regime we will continue to consider how best to ensure members’ interests remain central and their voices are properly heard.

Questions 19 & 20: Whether these were all the areas needed to enable TPR to evaluate a Superfund’s systems and processes? If not, we asked you to propose alternatives.

63. The main aim of the systems and processes requirement is to ensure that a Superfund is effectively run. The consultation suggested a number of areas that TPR would evaluate as part of the process of authorisation.

64. The vast majority of responses thought that the areas outlined in the consultation would enable TPR to make an accurate assessment of how effective a Superfund’s systems and processes are.

The Government’s response

65. In order to grant authorisation, TPR must be satisfied that the Superfund has effective systems and processes in place appropriate to its size and structure.

Options for regulating financial adequacy

66. This was the most contentious part of the consultation and there was no consensus on the right approach. Responses were predominantly divided between capital requirements being based on existing “stochastic” long term pension methods or the “adjusted market consistent balance sheet” approach used in the existing insurance regime. The responses we received highlighted what a difficult and challenging issue this is to resolve, and we are extremely grateful to experts from both the pension and the insurance industry for their insightful and informed contributions to this debate.

Questions 21 & 22: We asked if Superfund financial adequacy should be regulated through a pensions-based funding requirement approach with an added test of probability of success, or an insurance-based approach using a Solvency II type balance sheet and suggested some models to ensure appropriate financial adequacy.

67. There was a clear division between respondents when answering these questions. The division was most visible between industries the respondents predominantly worked in. Some respondents thought that a pensions-based funding approach was most appropriate given that the pension schemes in Superfunds are classified as occupational pension schemes and will be regulated using pensions legislation. Concerns raised with adopting a Solvency II type approach were that it would increase the cost of entering a Superfund, reduce innovation and restrict the assets a Superfund could invest in. This could potentially prevent investment in some assets that might still be suitable for long term pension liabilities and consistent with the Governments levelling up agenda.

68. Conversely, some respondents highlighted the clear similarities between Superfunds and insurance products. They acknowledged that to meet the policy objectives the Superfunds would need to be regulated to a lower level of security than insurance companies. However, Solvency II was considered a suitable regime, given that it is tried and tested and would allow for a direct comparison between the security offered in a Superfund and the security provided by an insurance company.

69. There was also a significant number of respondents who called for Government to develop a hybrid model based on existing pensions and insurance regimes.

The Government’s response

70. Having considered the many varied and comprehensive responses, we recognise there are elements of the Solvency II framework that have been effective in managing risk in the insurance sector. We therefore propose basing the financial requirements for Superfunds on a pensions approach, drawing limited elements of the Solvency II approach, where these will prove beneficial to the Government’s policy objectives.

71. It is critical that the capital requirement for Superfunds be risk-based and not an absolute or factor-based amount. We believe that capital requirements for Superfunds should be proportionate to the investment, longevity, and other financial risks taken, to provide a capital buffer that is consistent with Government’s stated tolerance for Superfund failure. This is also consistent with the principle of supportable risk that is central to the revised funding regime for mainstream DB which the Government recently consulted on. This will provide a capital buffer in the event of adverse economic stresses or demographic shocks. It will also match the level of resources held to the level of risk being run by the entity, which is critical for member security and avoiding excessive inappropriate risk taking.

72. The total capital required will be based on a suitably prudent set of TPs and calibrated to a 1-in-100 VaR over a one year period. This does not mean a Superfund would need to recapitalise every year however there will be a need to recapitalise if they fall below the total capital required when onboarding new schemes. We will consider whether to consult further on draft regulations, which will set out the specific technical details.

Question 23: We asked if a 99% probability of paying or securing members’ benefits over the lifetime of the scheme would provide an effective balance between employer affordability and member security.

73. A significant number of respondents had concerns about a 99% probability of paying or securing members’ benefits over the lifetime of the scheme. They argued this requirement was too onerous for Superfunds to be viable, commenting that it could be seen as stricter than a 99.5% probability of an insurer remaining solvent over a one-year period.

74. Others also claimed that this was too close to the 99.5% security offered by insurers and could lead to confusion when trying to compare the security offered in a Superfund with that offered by an insurer.

75. Another criticism of the approach was about the reliability of stochastic modelling for assessing the probability of failure over the lifetime of the scheme to an acceptable degree of accuracy. Many respondents pointed out the subjectivity and sensitivity to small changes in assumptions of long term stochastic modelling.

The Government’s response

76. We looked closely at the effects of having a very low risk of failure, including members achieving full benefits. This showed that a high level of security would come at a price, which our modelling estimates to be at 95% of current buyout pricing. Whilst it is clearly attractive to make the regime as secure as possible, we agree with the comments above that a regime set very close to buyout pricing would not be viable for Superfunds to operate in. Moreover it would not meet the original policy objective of providing an alternative solution to insurance buyout. This level of security would likely only be affordable to strong schemes which we believe could afford insurance buyout anyway.

77. Government Actuary’s analysis shows typical schemes with average employer covenants funded to 75% on a buyout basis, topped up by the employer’s contribution to 90% funded (our estimated entry threshold) and transferred to a Superfund, could reduce the risk of members not receiving full benefits from 20% to less than 2%. This is a small risk and represents a much better prospect of receiving benefits in full than would have been possible in the exporting scheme.

78. We have therefore decided that an estimated risk of a Superfund scheme entering the PPF of 2% would represent an acceptable level of risk for the new regime. Further modelling suggests that a Superfund running at this level of risk, which is within our risk appetite, would cost around 90% of buyout or below. This cost would be affordable for many schemes and employers that were unlikely to be able to afford an insurance buyout in the foreseeable future. Questions 25, 26 & 28: We explored some other issues around ensuring financial adequacy in a number of questions including a suitable authorisation basis and additional requirements on minimum standards and reporting.

79. Regarding the approach to regulation there was very little support for the legislation to require Superfunds to take a risk based long-term modelling approach when assessing the viability of a Superfund proposal.

The Government’s response

80. We do not intend to take forward the proposal for a risk based long-term modelling approach for individual Superfunds. However, we use long term modelling to inform our approach to a risk based capital assessment, calibrated to meet the broad objectives we set out in terms of member security, affordability and commercial viability and when setting minimum requirements for intervention, authorisation and most importantly profit taking.

81. Superfunds will have some flexibility to decide how they operate, their funding and investment strategies, and the basis on which they will accept schemes and take profits. What is set out below is a basis on which we can ensure certain minimum requirements are met in taking regulatory action or authorising new business and profit extractions. We accept that by doing so we may limit the potential for innovation and we consider this is acceptable when balanced against the need for adequate member protection.

82. Schemes will have a set of regulatory Technical Provisions (TPs) to ensure effective provision against future financial commitments and appropriate triggers. The discount rate used to calculate the TPs will be based on a prudent assessment of the expected investment returns that might be achieved on a suitable “low risk investment strategy”. This may be similar in nature to the low dependency investment strategy as discussed in the draft Occupational Pension Schemes (Funding and Investment Strategy and Amendment) Regulations 2023. The other assumptions used to calculate TPs will be determined on a best estimate basis . The TPs will also include an explicit reserve for member expenses and a longevity reserve as a margin against the risk of members living longer than expected. The longevity reserve will allow for a best estimate assumption for future improvements in life expectancy broadly in line with TPR interim requirements.

83. When we consulted in 2018 it was reasonable to have expected the discount rate to be of the order of gilt yields plus 0.5% pa based on market conditions at the end of December 2018.. More recent modelling suggests that up to gilts plus 1% may be appropriate under recent market conditions It is intended that legislation and guidance will set out more detailed proposals around how the discount rates will be set. For Regulatory purposes, it is envisaged that the same term structure for discount rates will be applied to all Superfunds. We believe the discount rate is in line with a low risk investment strategy and supported by analysis carried out by the Institute for Actuaries End-state for Defined Benefit Pension Schemes Working Party Report. The relevant pages are 20-23.

84. For a Superfund to be authorised and to continue writing new business it will need to be able to demonstrate a minimum level of funding and capitalisation. Superfunds would be expected to have sufficient assets to back TPs and 100% of the authorisation capital requirements, where authorisation capital requirements are calculated using a 1-in-100 VaR approach. This was the approach taken in the modelling and isn’t necessarily the standard model that will be used for calibration. The 1-in-100 VaR will include allowance for market risk, longevity and other demographic risks, and also operational risks.

85. Superfund’s liabilities and capital requirements will be determined as a single entity, except where a Superfund is set up on a sectionalised basis. For sectionalised Superfunds the requirements on capital adequacy, capital buffers, intervention and profit triggers will be applied to individual sections. Each section will then be expected to meet its capital requirements on a standalone basis. There will be no allowance for diversification of risks or capital requirements between individual sections within a Superfund.

Prudent versus best estimate basis

86. Having considered the varied responses, we propose that the regulatory TPs should be based on a best estimate of future cash-flows without any implicit allowance or bias for prudence. However, they would be required to hold explicit reserves for member expenses and also to retain an explicit reserve against adverse longevity experience particularly with regard to future improvements in life expectancies. For this purpose we would look to set best estimate and prudent reserve assumptions in line with TPR interim requirements, which also set assumptions for this particular purpose.

Yield curves and discount rates

87. We considered setting discount rates relative to the published gilt yield curve, which is a common approach used in calculating a DB scheme’s TPs, albeit discount rates usually include a prudent allowance for expected out-performance over gilts. Another approach might be to use the “risk-free” yield curve underlying an insurance company’s TPs.

88. We determined that the former option (setting discount rates relative to gilt yield curve) should be the approach to the discount rate used for Superfund liabilities; however, a dynamic approach would be used in the allowance for expected out-performance. It is intended that legislation and guidance will set out more detailed proposals around how the discount rates will be set to best achieve the broad policy objectives.

Allowance for modest out-performance

89. Some respondents argued that a pure gilts-based approach was a very prudent basis for determining TPs in a pensions context. TPR are currently considering discount rates in the range of gilts plus 0.5% pa as a basis for setting a low dependency basis for DB schemes for Fast Track but with greater flexibility to go above this in Bespoke, subject to appropriate justifications and relevant stress test parameters. This is broadly the approach we intend to take using a dynamic basis to setting expectations based on gilt on market conditions.

Long term objective

Questions 24 & 30: We asked if the scheme within a Superfund should have a long-term objective to buyout, and whether Superfunds should be required to secure benefits with an insurance company as soon as practicable, once the scheme assets reach the buyout level of liabilities.

90. Many respondents felt that although it is a sensible objective to target an insurance buyout, it should not be a legislative requirement. Some from the insurance sector did think that a legal objective to buyout would be needed, mainly to avoid arbitrage, where buyout is avoided in favour of keeping a scheme in a Superfund.

91. Other respondents pointed out that the aim of Superfunds is to enhance the security of those schemes that cannot afford to secure benefits with an insurer in the medium term, and that a requirement for an objective to buyout will impair innovation and lead to sub optimal outcomes.

92. The responses provided on whether Superfunds should be required to secure insurance buyout once scheme assets allow, followed a similar pattern to this discussion around the long term objective. A significant number of respondents raised that it was a logical step and part of the fiduciary duties of trustees to consider securing benefits with an insurer, if the assets within the scheme were sufficient.

The Government’s response

We accept that the emerging Superfund market requires flexibility and space to innovate, and it is crucial that consolidators do not become ‘forced buyers’ of insurance bulk annuities. As set out from paragraph 41, like all DB schemes, each Superfund will be required to operate with a long term objective, intended to clarify the Superfund’s ‘endgame’, and this may include a plan to gradually transfer liabilities into the bulk annuity market or look at moving to a lower risk dependency model for investment strategies. It is important that this objective is coherent and transparent to all trustees of ceding schemes, in order that they are able to properly understand the impact of consolidation on their members. Further we propose that TPR monitor a Superfund’s progress against their respective long term objectives as part of their supervisory approach.

Intervention levels

Minimum funding level

93. The schemes within a Superfund are classed as DB pension schemes and so will be eligible for protection from the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) in the event of a Superfund insolvency. The consultation proposed that the measure of failure, and the point at which the scheme in the Superfund is wound up occurs where financial resources fall below 105% of PPF s179 liabilities, in order to provide some protection against further deterioration in the funding level during the time taken to wind up the scheme.

Questions 32, 34 & 36: We asked if the failure test in relation to the PPF funding level is proportionate and at what level above fully funded on the s179 basis should the minimum funding trigger be set?

94. The majority of respondents were supportive of a proposal to have a failure test in relation to the PPF funding level. However, there was a divergence of views on the level and some helpful suggestions of other factors that should be taken into account.

The Government’s response

95. Having considered the responses, we propose to define failure, and the minimum funding level as the financial resources of the scheme falling below 102.5% of the s179 liabilities and have modelled on this. We consider that 102.5% provides an appropriate margin, without necessarily increasing the number of schemes that are wound up unnecessarily, although this will depend ultimately on the types of schemes being taken on in terms of benefits and liability profile. We will also consider how this works, if it’s a fixed rate, or if there are means of offering some flexibilities where this may be required. Along with this we will also consider if TPR need an ability to consider exceptional circumstances and vary the rate for the minimum funding level accordingly as they set out in their interim guidance.

Questions 37 & 38: We asked stakeholders if they agreed that there should be a Level 1 funding level trigger to protect members’ benefits at this level and how this should be expressed.

96. Most respondents agreed with the level 1 proposition to protect members’ benefits at a level higher than PPF benefits. Although some argued that introducing too many levels might over-complicate the management of Superfunds with some suggestions of a more bespoke approach to funding levels and dialogue with Superfunds, for TPR to determine when intervention is needed. There were also mixed views about how to best express the trigger.

The Government’s response

97. We propose to set the Level 1 level at or around 100% of TPs. This might be marginally lower than the level proposed in the consultation for a typical scheme. Some responses suggested the Level 1 trigger proposed in the consultation was set at too high a level and could discourage potential investors. However, setting the Level 1 trigger at or around 100% of TPs should be sufficient to continue to run-off the scheme under the supervision of the existing trustees. However, this might give little margin for further poor performance. This is one area where further work may need to be completed to assess the risks of an intervention level set at or around this level and the implications for potential investors.

Question 41: We asked if a Level 2 trigger was a reasonable basis on which to prevent new business being written, or whether this should this be left to the discretion of the Superfund trustees on the basis they should not be accepting new business if it would have a detrimental effect on existing Superfund members.

98. The consultation proposed a Level 2 funding level trigger to prevent a Superfund from acquiring new schemes if it no longer meets the funding level requirements for authorisation. In these circumstances the Superfund would remain authorised to run on with existing schemes, subject to the minimum and Level 1 funding level triggers not also being breached. As previously mentioned, if a Superfund manages to return to the authorisation funding level it will then be allowed to resume taking on new business.

99. We received a range of responses with some respondents agreeing that Level 2 was sensible for the protection of beneficiaries. However, a number of respondents argued that this decision should be left to the Superfund trustees.

100. Again, a reiteration of trust law and guidance from TPR will be important for trustees in this position and could help to self-police this area. Also, the independence of the trustees, or at least robust governance and understanding of their duties, will be important given they may come under commercial pressure from the Superfund sponsor to accept new business.

The Government’s response

101. On balance, we propose to set the Level 2 trigger at TPs plus 100% of the authorisation capital requirement. This would mean that if the Superfund is below this funding level it will not be able to take on new schemes. This authorisation capital requirement would be broadly equivalent to a 1-in-100 VaR measure over one year.

Profit trigger: A trigger to allow when profit can be taken either by investors or members.

Questions 42, 43 & 44: We asked several questions around the requirements for profit extraction.

102. We received a mix of responses, with some respondents arguing that profit shouldn’t be taken until after benefits had been secured with an insurer. Others took a more flexible view that consolidators should be able to propose their own rules for future profit extraction and that this should form part of the authorisation process.

103. Some respondents argued that profit should be allowed to be taken as long as the Superfund remained in a financially secure enough position to remain authorised. However, others argued that there should be a required margin above the authorisation level before any profit could be taken.

104. Many respondents were keen to point out that the primary aim of the Superfund was to improve the probability of members receiving full benefits.

105. Regarding the temporary retention of profits to mitigate against extraction due to market volatility rather than genuine outperformance, many respondents were supportive of such a restriction. However, the argument was raised that rather than setting a fixed period to retain profits, Superfunds should be required to extract profits in a sustainable manner.

The Government’s response

106. We agree that member’s interests must come first, whilst acknowledging that the Superfund must be able to attract the investors needed to provide the external capital. We propose that a Superfund may draw profits prior to securing buyout with an insurance company, but only after funding levels surpass the ‘profit trigger’, set at an appropriately high level as to mitigate against the risk of value extraction at a level that may put members’ benefits at risk. The profit trigger will therefore be set at a suitably prudent level above TPs .Once scheme funding is beyond this level, the Superfund will be able to extract profits.

107. In response to the discussion around temporary retention of profits after reaching the trigger, we agree that it is a reasonable safeguard against market volatility and will continue to work through the detail of how such a restriction would apply in practice.

108. We are also aware of concerns around ‘disguised’ profit extraction, through excessive expenses or charges levied by a Superfund against scheme assets or the capital buffer. The following section provides more detail on the careful supervision of this form of value extraction.

Expenses

109. In exchange for the provision of services, Superfunds may need to levy fees and charges on a scheme and/or capital buffer. We envisage that the future Superfund regime with regard to fees and charges, will expand on the existing TPR guidance for Superfunds prior to permanent legislation. The Regulator’s guidance places a series of expectations on the corporate entities managing Superfunds around value extraction, whilst not setting a prescriptive limit or cap on the acceptable level of fees and charges levied against a scheme. This is because of the wide variety of models that we anticipate entering the Superfund market in both size and complexity, and the additional expectations placed on Superfunds relative to the wider Defined Benefit market. Therefore, we feel it would be impractical to set a fixed cap on costs at this stage.

110. However, the principles for value extraction and the requirements on Superfunds around transparency, particularly in providing evidence of value for money on an ongoing basis, will be sufficiently comprehensive and secure as to prevent inappropriate transactions against either a scheme or capital buffer. When imposing fees and charges it is important that Superfunds perform benchmarking analysis to demonstrate that their costs are equitable, and all relevant parties must have prior notice of any fee or charge. As fees and charges may be levied against scheme assets, it is essential that any costs do not disrupt the financial security, capital requirements and funding triggers which will affect a Superfund.

111. Trustees will be expected to continually monitor and ensure that all service providers offer value for money, and will need to report material changes to their policies on fees and charges to the regulator. It is important that if relevant funding triggers (Level 1 or Minimum funding) are hit any contracts, which restrict the control of trustees over the direction of the Superfund, should fall away.

112. We will also expect a high level of transparency from Superfunds around their fees and charges, both in ensuring that prospective ceding employers and trustees are fully aware of all associated costs ahead of a transfer, and in the initial and periodic assessments by the regulator. During authorisation, the regulator will expect Superfunds to demonstrate how its expense allowance was calculated, where costs will fall, and provide detail of performance-related fee structures, amongst other information including ongoing costs.

Regulator intervention

Questions 33 & 40: We asked questions around the powers that TPR should hold should a funding level trigger be breached, or if triggers are not acted on in the best interests of members.

113. A majority of the respondents agreed with the principle behind this question.

114. In addition, respondents noted that consideration should be given to individual member redress, if they feel their best interests have not been represented. For instance, it should be considered whether scheme members should be able to go back to the original trustees and employer in the event of commercial consolidator insolvency or misconduct, and how trustees and employers can be protected against that. Furthermore, scheme members should be able to utilise the Pensions Ombudsman Service, or the Financial Ombudsman Service, where they have felt their best interests have not been met.

115. We received a range of responses suggesting TPR powers, detailed in legislation, that could be used to intervene should the funding level trigger be breached. These suggestions included, but were not limited to:

- power to request information from anyone involved in running a Superfund and/or third party service providers and advisers

- power to replace Superfund trustees or scrutinise them

- power to require a recovery plan and/or close to new business

- power to stop investor returns and fees

- power to prevent excessive dividend payments to commercial consolidators’ shareholders

- power to transfer liabilities to a new Superfund; and,

- power to trigger a wind up

The Government’s response

116. We propose that TPR will have the power to intervene and require certain actions to be taken in the running of the Superfund, for example in running on a scheme or section without a significant sponsor. The Government will continue to work with TPR and other relevant parties to examine the above proposals and determine what is necessary and can be practically and effectively implemented.

Recovery period

Questions 35 & 39: We asked if 3 months would be an appropriate period of grace to allow for any volatility in investments to recover when a triggering funding level if breached.

117. We received a range of responses, with some agreeing that 3 months would be an appropriate period of grace as it will enable decisions to be made based on a more representative funding level rather than one derived from short term market movements. There were some respondents who argued this was too short and a longer period of 6 or 12 months would be more appropriate, although the argument was also made that 3 months could be too long as the capital buffer may significantly reduce in value.

The Government’s response

118. Having considered the responses we appreciate that one approach might not be suitable for all situations. Therefore, we will continue to work with TPR and others and learn from the experiences of their interim guidance, to determine what might be a reasonable approach in practice to put in the legislation.

Sectionalised schemes

Questions 45 & 46: We asked questions about the regulation of sectionalised Superfunds, with particular focus on funding level triggers and profit taking.

119. Views on whether it is reasonable to allow a sectionalised Superfund to take profit or write new business if one or more sections are inadequately funded were largely split. Those who agreed that it is a reasonable approach to treat sections in isolation, argued that the individual sections would be similar to separate Superfunds.

120. Those respondents in opposition to this proposal argued that consolidators should be reviewed on an aggregate basis with all sections being adequately funded as the first priority.

121. We also asked how should each section within a sectionalised Superfund be treated for the purposes of assessing financial adequacy and funding level triggers. The responses were varied, with many pointing out that the suitability of a particular approach will depend on whether the capital buffer is sectionalised, or whether there are cross subsidies between schemes from the capital buffer.

The Government’s response

122. Having considered the responses we consider that on balance each Superfund should be authorised as a single entity. Where a Superfund is sectionalised, the requirements on capital adequacy, capital buffers, intervention and profit triggers will be applied to individual sections. When a particular section breaches the funding triggers, this section will be treated in isolation, in terms of any regulatory action that might be required, or to be individually wound-up. We will consider the necessary response in the event that a Superfund has a significant number of sections failing simultaneously, given the regulatory attention this would require. This would necessarily reference materiality, as in a section with a large amount of assets compared to a larger amount of smaller sections.

Control of assets and access to the capital buffer

Questions 47, 48 & 49: We asked questions about the minimum requirements and standards for the capital buffer, to strike an effective balance between adequate protection for members and the commercial viability of Superfunds.

123. We asked about the suitability of a proposed approach to ring fence the assets in the capital buffer instead of transferring them into the scheme as the deficits emerge. Although some respondents felt this was an adequate arrangement, there were others who felt this was too restrictive to attract investment or did not provide enough protection to member benefits.

124. We received a range of responses suggesting suitable minimum requirements on a buffer fund, in order for a scheme to be able to rely upon the assets being available in the event they are needed. The common theme in those responses was that the buffer should be structured in a way that ensures trustees can access the funds when required. However, some pointed out that mitigations should be put in place to discourage excessive risk taking, i.e. stressing the value of assets depending on the nature of risk they pose. This would incentivise appropriate risk-taking.

The Government’s response

125. We intend that the Superfund body corporate will be required to hold the capital buffer in an escrow arrangement within the UK. Where a Superfund is structured to hold assets outside the scheme, whose purpose is to protect the scheme in the absence of a traditional employer covenant, it is essential that those assets are held securely and are available when needed (not least because the assets within the buffer fund will go towards the assessment of the financial sustainability of the proposal). Superfunds must provide assurance and evidence that the following key principles are met:

- buffer fund assets cannot be released outside of defined circumstances (for example, in line with a defined profit extraction rule)

- the risks within buffer fund investments cannot be materially increased after TPR’s initial assessment without approval or re-assessment of the Superfund’s financial sustainability (that is, through the significant events framework). Any required capital is then to be provided and proposed changes advised in advance

- changes in buffer fund asset allocation and risk profile cannot be made without consultation with scheme trustees; and supported by additional risk capital where appropriate

- evidence must be provided of a legally enforceable mechanism for the assets of the buffer fund to transfer to the scheme if there is a trigger event

- The design details for the buffer fund will also need to be considered in line with any review of the Superfund tax regime by HMRC.

126. The consultation made clear that for authorisation the expectation will be that financial reserves should be ring-fenced, with trustees having first call on any assets. It also sets out that a proportion of the financial reserves would be expected to be held in cash, or near cash, to address any short-term liquidity issues in the event of failure. For authorisation Superfunds must be able to demonstrate the following:

- the pension scheme is financially sustainable and has an adequate capital position. The pension scheme should have a high probability of success in paying benefits in full, and should have access to financial reserves to cover the costs arising from a triggering event. Access to these reserves should not be impacted by the insolvency of the commercial entity