Statutory guidance: Disclose and Explain asset allocation reporting and performance-based fees and the charge cap

Updated 30 January 2023

Guidance for trustees of relevant occupational pension schemes

Background

About this guidance

1. The Occupational Pension Schemes (Administration, Investment, Charges and Governance) and Pensions Dashboards (Amendment) Regulations 2023 (“the 2023 Regulations”) introduce new requirements for trustees and managers of certain occupational pension schemes.

2. For the first scheme year that ends after 1 October 2023, trustees or managers of relevant[footnote 1] occupational pension schemes, are required to disclose their full asset allocations of investments from their default arrangements. Where a relevant scheme is a qualifying collective money purchase scheme[footnote 2], trustees/managers must disclose its full asset allocations of investments as such schemes will not have default arrangements[footnote 3]. This information must be recorded in the annual chair’s statement and is to be published alongside other relevant parts[footnote 4] of the statement on a publicly accessible website.

3. This guidance is intended to help and assist trustees and managers of relevant occupational pension schemes in the calculation and format of asset allocation disclosures.

4. From 6 April 2023, the 2023 Regulations also introduce an option for trustees and managers to enter investment arrangements that include performance-based fees, in the knowledge that they will be able to exempt these from their charge cap calculations[footnote 5]. The 2023 Regulations attach conditions on what qualifies as a performance-based fee structure for the charge cap exemption. These are referred to in the 2023 Regulations as ‘specified performance-based’ fees.

5. This guidance provides support on the broad range of performance-based fee structures that exist and an understanding of the merits of these. It does not provide an exhaustive list of what performance-based fees do, or which fee structures are considered most appropriate. Trustees and managers must have regard to this guidance, but they should also seek their own independent professional and legal advice before entering into any agreement which involves the use of performance-based fees.

6. This guidance, issued by the Secretary of State for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), should be read in tandem with the 2023 Regulations.

7. Existing legislation places duties on trustees in relation to scheme administration and governance and trustees must ensure they are familiar with these duties. Trustees should also refer to The Pensions Regulator (TPR) codes of practice and guidance on the standards expected when complying with their legal duties and seek their own independent legal advice.

Who this guidance is for

8. This guidance is for trustees and managers of relevant occupational pension schemes who, regardless of size, must comply with the requirements to calculate and report their asset allocation in accordance with regulations 23(1)(aza) (annual statement regarding governance) and 25A (assessment of asset allocation) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996 (“the Administration Regulations”[footnote 6]), and publish this information under regulation 29A of the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 (“the Disclosure Regulations”[footnote 7]), as amended by the 2023 Regulations.

9. This guidance is also for trustees and managers of occupational pension schemes which provide money purchase benefits who wish to exclude ‘specified performance-based fees’ from the regulatory charge cap set at 0.75% p.a. A specified performance-based fee is defined in Regulation 2 of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015 (“the Charges and Governance Regulations”[footnote 8]) and must be disclosed in accordance with Regulations 23 and 25 of the Administration Regulations and published in accordance with Regulation 29A of the Disclosure Regulations, as amended by the 2023 Regulations.

10. The guidance is not relevant to:

-

an executive pension scheme;

-

a relevant small scheme;

-

a scheme that does not fall within paragraph 1 of schedule 1 (description of schemes) to the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013;

-

certain public service pension schemes;

-

a scheme which provides no money purchase benefits other than benefits which are attributable to additional voluntary contributions.

Legal status of this guidance

11. This statutory guidance is produced under the powers in:

-

Paragraph 1(2)(b) of Schedule 18 to the Pensions Act 2014

-

Paragraph 2(2)(b) of Schedule 18 to the Pensions Act 2014

-

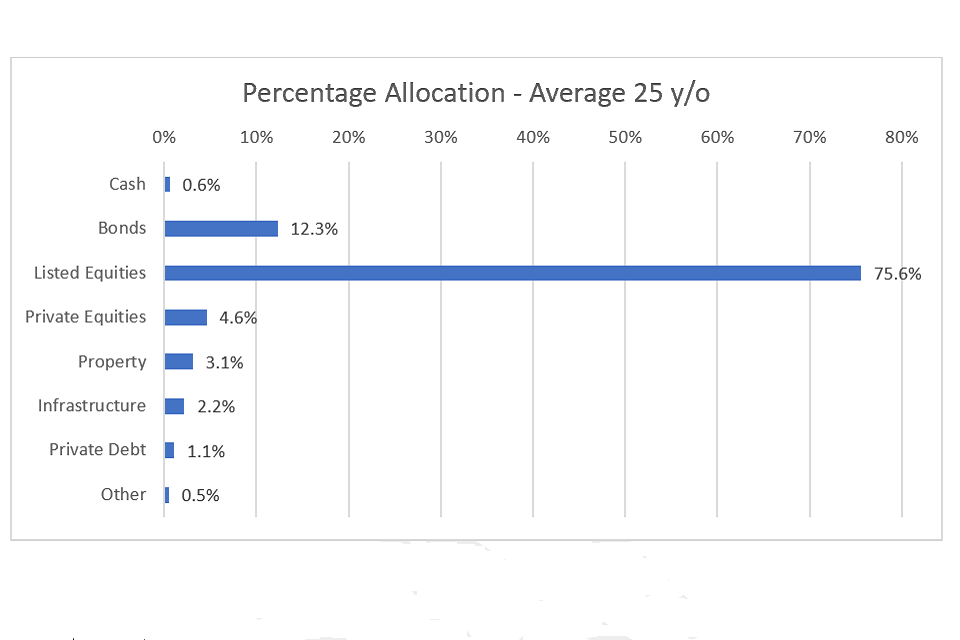

Section 113 (3A) of the Pension Schemes Act 1993

Compliance with this guidance

12. TPR regulates legislative compliance for all occupational pension schemes and publishes guidance on the roles of employers and trustees. Neither the Government nor TPR can provide a definitive interpretation of legislation, which is a matter for the courts.

13. Where schemes do not comply with a relevant legislative requirement TPR can take enforcement action depending on the nature of the breach. This could include a financial penalty.

14. Enforcement of the requirements contained in Part V of the Administration Regulations, including the production and content of the chair’s statement, is provided for in Part 4 of the Charges and Governance Regulations.

Expiry or review date

15. This guidance will be reviewed, as a minimum, every three years, from the date of first publication, and updated when necessary. When the guidance is reviewed, established and emerging good practice and user testing may be included.

Disclose and explain asset allocation disclosure

16. The 2023 Regulations require trustees or managers of relevant occupational pension schemes to disclose the percentage of assets allocated in the default arrangement to specified asset classes. Where a relevant scheme is a qualifying collective money purchase scheme, this breakdown is required in respect of the asset classes held by the scheme.

17. Publication of asset allocation data will be an important step towards transparency, standardisation, and comparability across the occupational pensions market. It is important that members have access to all relevant information surrounding the investments being made using their savings and the outcomes these investments could have on their future retirement. Public disclosure should also enable trustees, employers, and members to compare the value for money that differing asset allocations bring to members when read alongside the net returns on investments, also published in the annual chair’s statement.

18. The information on asset disclosure must be stated in the annual chair’s statement for the first scheme year ending after 1 October 2023, be updated annually, and be published alongside other relevant parts of the statement on a publicly available website.

19. This section of the guidance is designed to assist schemes in the reporting of their asset allocations. For illustration purposes, we suggest how this information could be displayed in the required disclosures.

Scope

20. The 2023 Regulations require all relevant schemes providing money purchase benefits or collective money purchase benefits to disclose and explain their asset allocation in their annual chair’s statement. This includes any hybrid scheme which offers money purchase or collective money purchase benefits.

21. Where these disclosures relate to a default arrangement within a relevant scheme, a “default arrangement”[footnote 9] is where contributions are placed without the member having expressed a choice as to where the contributions are allocated, or in which 80% or more of members have actively chosen to invest. Some exceptions apply (for example, arrangements relating solely to AVCs). Legal requirements applicable to default arrangements differ depending on whether they are used by employers to comply with their duties under automatic enrolment. The legal definition of “default arrangement” is set out in regulation 3 of the Charges and Governance Regulations, with the modifications set out in regulation 1 of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005[footnote 10].

22. Where a scheme has more than one default arrangement, trustees/managers should look to disclose the asset allocation for each default arrangement, regardless of how or when they became default arrangements, where members are still invested in the fund at the end of the scheme year. This is so that members invested outside of the main default can also benefit from this information. The calculation of asset percentages operates at the level of each default arrangement, rather than across all default arrangements combined.

23. If a qualifying collective money purchase scheme is divided into sections[footnote 11] (or if there is a qualifying collective money purchase section or sections within a scheme) then the asset allocation within each section’s fund should be reported on separately.

Asset allocation disclosure

24. The 2023 Regulations require trustees to disclose in their annual chair’s statement the percentage of assets allocated to each of the following asset classes in their default arrangement, or scheme if a qualifying collective money purchase scheme:

a. cash

b. bonds creating or acknowledging indebtedness, issued by a company or issued by His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom or issued by the government of any country or territory other than the United Kingdom

c. listed equities - shares listed on a recognised stock exchange

d. private equity (that could include venture capital and growth equity) - shares which are not listed on a recognised stock exchange

e. infrastructure - physical structures, facilities, systems, or networks that provide or support public services including water, gas and electricity networks, roads, telecommunications facilities, schools, hospitals, and prisons

f. property/real estate - property which does not fall within the description in paragraph (e)

g. private debt/credit - instruments creating or acknowledging indebtedness which do not fall within the description in paragraph (b)

h. other - any other assets which do not fall within the descriptions in paragraphs (a) to (g).

Asset class definitions

25. Explanations of the asset classes that must be disclosed in a clearly identifiable manner are provided below. Further detail is then included on sub-asset classes that schemes may wish to also disclose to help member understanding:

-

Cash: Cash and assets that behave similarly to cash e.g., treasury bills. This only includes invested cash and not cash held in a bank account or accounting values such as net current assets.

-

Bonds: Loans made to an issuer (such as a government or a company) which undertakes to repay the loan at an agreed later date. The term refers generically to corporate bonds or government bonds (such as gilts). Schemes must disclose the percentage of their default asset allocation, or asset allocation if a CMP scheme, held in corporate and government bonds. Schemes may wish to provide further information about specific types of bonds they invest in, where applicable, such as:

-

Fixed interest government bonds

-

Index-linked government bonds

-

Investment grade bonds

-

Non-investment grade bonds

-

Securitised credit

-

-

Listed equities: Shares in a company which is listed on a stock exchange and can be bought and sold on that stock exchange. Owning shares makes shareholders part owners of the company in question and usually entitles them to a share of the profits (if any), which are paid as dividends. Where applicable, schemes may wish to provide further detail on their listed equity regional allocations as follows:

-

UK equities

-

Developed market equities (excluding UK)

-

Emerging markets

-

-

Private equity: Unlisted equities which are not publicly traded on a stock exchange. Private equity funds can encompass a broad range of investment styles. Schemes should provide a sub-asset allocation to show members the nature of their exposure. This may include:

-

Venture capital: Private equity generally for small, early-stage business that are expected to have high growth potential but with access to other forms of financing.

-

Growth equity: investment in a relatively mature company that is going through a transformational event in their lifecycle, with potential for growth

-

Buyout or leveraged buyout funds: Invest in more mature businesses, often taking a controlling interest.

-

Where applicable, schemes may wish to provide further detail on their private equity investments as follows:

-

Proportion of UK-based companies invested in

-

Proportion of non-UK based companies invested in

-

Proportion in particular sectors (example: technology, life sciences, climate-based solutions, sustainable energy, etc.)

-

Whether invested through a pooled fund / collective investment scheme / Long Term Asset Fund etc.

-

Infrastructure: physical assets that support functioning society such as water, gas and electricity networks, roads, telecommunications, schools, hospitals, prisons etc. Schemes should state their infrastructure investment (UK and/or overseas) under this asset class category, even if that exposure is through one of the other asset classes listed in this guidance. Schemes may wish to provide a breakdown of their infrastructure assets by:

-

Economic infrastructure – includes investments in renewable energy, utilities, transport, and telecommunications.

-

Social infrastructure - mainly involves public health, education and building, construction, and maintenance.

-

Schemes may wish to provide further details of the type of infrastructure assets presently held and how they may be developed over the life of the investment, this could be aided using a case study.

-

Property: Real estate.

- Freehold, (In Scotland, ‘heritable’) or leasehold land or buildings.

Schemes may wish to provide narrative to help members understand the types of property that have been invested in (such as offices, retail, etc.) and the nature of that investment (such as long-term leases, short term development etc).

-

Private debt: non-bank lending to companies, not issued or traded publicly. Private debt can encompass a broad range of investment styles, schemes may wish to provide a sub-asset allocation to show the reader of the disclosures the nature of their exposure. This could include:

-

Seniority of debt

-

Geography

-

Sector

-

-

Other: Assets which are not considered to be part of any of the asset classes described above.

In addition, if schemes wish to disclose their fund fact sheets and have already adhered to all disclosure requirements, they can, however this is not a requirement.

The total asset allocation should add up to 100%.

Importance of look-through for asset allocation disclosure

26. Where schemes use funds that allocate to more than one asset class, or their fund then invests in other funds, trustees should look through the fund(s) and state the underlying asset allocation of each fund vehicle. For example, with a multi-asset fund, when you look through to the underlying assets, there is exposure to private equity, infrastructure, private debt, property etc. Examples of such funds can include funds that are often categorised or named as managed, balanced, multi-asset or diversified funds.

27. There are a range of legal fund structures that determine the ownership of the underlying assets within a fund. For example, underlying assets may belong to the trustees, or the trustees may own units of the fund. The value of those units is closely linked to the value of the pool of underlying assets, rather than just the fund overall.

28. Trustees must look through the ownership structure of the fund vehicle to the allocation of the underlying asset classes[footnote 12]. For example, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) are a type of company that invest in property, we would therefore expect its allocation to appear under a property heading. However, where REITs operate as listed funds and if trustees or their investment managers are holding REITs as part of an equity portfolio, they may wish to assign these REIT holdings to listed equities.

29. Where schemes use assets that do not use a physical allocation, such as derivatives, trustees should aim to state what their synthetic allocation would provide in physical asset terms. Where that is not possible, schemes should provide an explanation to help members understand the situation but class the assets as “other” so that the total asset class percentage remains at 100%. The nature of such synthetic exposures can be complex and may not clearly transcribe into the specified asset allocation list where the total of all assets is expected to sum to 100%.

30. Schemes should only state the exposure to their invested assets and should not include non-invested assets, such as cash at bank or accounting values such as net current assets.

Age-specific disclosures

31. Schemes are recommended to use age profiles as part of the default asset allocation disclosure to represent the different asset allocation phases in accumulation. We would suggest that schemes may wish to consider using ages that are consistent with existing disclosures. For example, we advised in ‘Completing the annual Value for Members assessment and Reporting of Net Investment Returns’ guidance[footnote 13], age specific asset allocations for savers aged 25, 45, 55 years. We would also recommend using “1 day prior to State Pension Age” as a further age cohort for disclosure to capture asset allocations close to retirement age and just before decumulation begins, when de-risking is more prevalent. It is also intended to make the disclosures more consistent where different schemes have different default end ages and members select different retirement ages.

32. Such an approach is not expected in collective money purchase schemes given their collective nature.

33. The table below provides an example as to how schemes could report their asset allocation by the four recommended age cohorts. The example is presented in both table and graph form since disclosure of this kind must be accessible to members as well as industry experts. To note, the examples provided below act as an illustrative representation of a pension scheme’s asset allocation and do not represent DWP’s understanding of best practice or attempt to represent any particular scheme in reality.

Composition of returns & example presentations of data

| Asset class | Percentage allocation – average 25 y/o (%) | Percentage allocation – average 45 y/o (%) | Percentage allocation – average 55 y/o (%) | Percentage allocation – average 1 day prior to State Pension Age (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | 0.6 | 6.3 | 31.6 | 54.3 |

| Bonds | 12.3 | 39.3 | 37.2 | 38.1 |

| Corporate bonds | 8.1 | 22.6 | 18.7 | 18.4 |

| Government bonds | 2.7 | 9.4 | 12.3 | 16.2 |

| Other bonds | 1.5 | 7.3 | 6.2 | 3.5 |

| Listed equities | 75.6 | 43.7 | 22.9 | 5.5 |

| Private equity | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| Venture capital/growth equity | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Buyout funds | 3.7 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Property | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| Infrastructure | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.4 |

| Private debt | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Other | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

34. The graph below is an example of how schemes may like to disclose the asset allocation for an individual age cohort.

An example of how schemes may like to disclose the asset allocation for an individual age cohort.

Reporting Period

35. Schemes should calculate and report the allocation of assets as part of their annual chair’s statement. The first chair’s statement to include this asset allocation disclosure is for the first scheme year ending after 1 October 2023. This information must also be published alongside other relevant parts of the statement on a publicly available website.

Averaging

36. If a scheme’s asset allocation has fluctuated or changed significantly throughout a scheme year, trustees/managers may wish to use averaging to represent their allocation, however, this is not a requirement. Where completed, this could be done by selecting four valuation points throughout the year, no closer than three months apart, at which the percentage allocation to each asset class is calculated. A mean average of these percentages could then be calculated and disclosed as an average from across the scheme year.

Performance-based fees and the charge cap

Applies to default funds of occupational money purchase pension schemes used for automatic enrolment or collective money purchase benefits.

37. Regulation 2 of the 2023 Regulations amends the Charges and Governance Regulations to add ‘specified performance-based fees’ (paid in relation to an investment fund in which a pension scheme invests) to the list of charges that fall outside the regulatory charge cap limit of 0.75% p.a.

38. Specified performance-based fees are considered to be designed so that the fee is incurred when a fund’s performance exceeds a pre-agreed investment return. This section of the guidance is designed to assist schemes determine which criteria must be met for a specified performance-based fee to be considered outside the scope of the charge cap. Performance-based fees that are not considered to meet the criteria can still be used by schemes, however they will be subject to the charge cap.

39. Schemes should be aware that the exemption from the charge cap does not apply to fees that are not related to performance. This includes annual fixed management fees or other charges that may form part of an overall fee agreement where performance-based fees are also present. These will continue to be subject to the charge cap calculation.

40. Schemes must ensure that any specified performance-based fees relating to funds that their scheme has invested in are disclosed in the annual chair’s statement. This information must also be published on a publicly available website. This disclosure is to ensure full transparency to members.

41. The provision allowing specified performance-based fees to be excluded from the cap is intended to make it easier for schemes to be able to access a broader range of asset classes where performance-based fees are more prevalent, and where the trustees or managers of the scheme believe investing in these assets is in the best financial interests of members. These financial interests will become evident through an increase in member’s retirement outcomes (net of fees), but could be measured in other ways, such as improving diversification which can help provide resilience in the market.

42. Trustees and managers should aim to maximise returns, but at the same time consider, as part of a holistic assessment, the risks taken in order to achieve those returns.

43. From the outset schemes should consider whether the additional incentive provided by a specified performance-based fee to a fund manager, is expected to lead to additional value to members that outweighs the expected cost to members, including where this value could not be achieved through a flat fee-based structure.

44. In addition to this guidance, schemes should also seek professional advice on their investments where performance-based fees may be incurred.

45. This guidance does not cover the strategic or operational aspect of investing in illiquid assets. The operational aspect includes valuation, member flows and fairness to members. Schemes should seek professional advice on these practical challenges as part of their evaluation of how funds with performance-based fees will form part of their scheme’s overall investment arrangements.

What are performance-based fees?

46. Performance-based fees aim to align the financial interests of the investment/fund manager and investors, in their joint aspiration for profit. They are commonly associated with investments where there is a high level of involvement by the fund manager in executing the fund’s investment strategy and the management of underlying assets.

47. Performance-based fees are often found in privately traded assets such as private equity, venture and growth capital, and private credit as well as liquid alternative funds. Such funds may also invest in publicly traded assets. A performance-based fee can therefore be applied to any asset class or a fund that blends multiple asset classes.

48. The structure of performance-based fees varies. The most common structure being the combination of a fixed annual management fee linked to the size or value of the committed capital and paid regardless of return, and a performance element which is payable upon investment returns exceeding a certain pre-agreed rate of return. To note, it can also be possible to invest in privately traded assets just through a fixed management fee structure.

49. In this guidance performance-based fee relates to where the fund manager or investment partner (in the case of profit-sharing arrangements) is rewarded based on the performance of the investment exceeding a specified pre-agreed rate of return, or where the value of investments exceeds a specified pre-agreed amount.

50. A profit share mechanism, such as, ‘Carried Interest’ is classified as a performance-based fee, even though the remuneration is generally paid by way of a share of profits in a collective investment scheme, rather than a direct fee paid to a fund manager. In the case of profit-sharing arrangements, this occurs when there is a return above a pre-agreed rate, and when the investment is eventually sold, the proceeds are distributed.

51. Schemes should take professional advice from a competent advisor on performance-based fees when evaluating any investments. For those with performance-based fees, schemes should consider these in the context of other investment opportunities, their fee structures and the operational implications of including those types of investments in the scheme’s investment arrangement. Schemes should also consider the extent to which there may be scope to work with fund managers to develop terms that best serve member outcomes.

Specified performance-based fees

52. The 2023 Regulations determine that only a performance-based fee that meets the following criteria can be excluded from the charge cap calculation:

“Specified performance-based fees” means fees, profit-sharing arrangements, or any part of fees or profit-sharing arrangements, which are—

(a) payable by or on behalf of the trustees or managers of a pension scheme to a fund manager in relation to investments (“the managed investments”) managed by the fund manager, either directly or as part of a collective investment scheme, for the purposes of the scheme;

(b) calculated only by reference to investment performance, whether in terms of the capital appreciation of the managed investments, the income produced by the managed investments or otherwise;

(c) only payable when—

(i) investment performance exceeds a pre-agreed rate, which may be fixed or variable; or

(ii) the value of the managed investments exceeds a pre-agreed amount;

(d) calculated over a pre-agreed period of time; and

(e) subject to pre-agreed terms designed to mitigate the effects of short-term fluctuations in the investment performance or value of the managed investments.”

Investment performance

53. The performance of the fund should be derived from realised returns from disposal or the change in valuation of the fund’s underlying assets and any income that those assets have produced. The calculation of the return will be in accordance with the fund’s investment vehicle and the regulatory guidelines for that fund vehicle, with further detail specified in the terms of the fund.

54. We would expect the fund authorisation regime to require verification of performance. It is recommended that trustees ensure that there is independence in the valuation, such as from an independent valuation function or the use of a third-party valuer, or an independent audit.

Pre-agreed rate or amount

55. Trustees or managers of the scheme should agree with the fund manager the agreed rate or amount which the investment must reach, or which must be realised i.e., the asset is sold before the fund manager is entitled to a performance-based fee, or that the fund may calculate a performance-based fee on a fixed date against an agreed rate. Where schemes invest in a fund alongside (and on the same or substantially the same terms as) other third-party investors not linked to the fund manager, there is no need for the performance-based fee to be separately negotiated by the scheme in order for it to be exempt from the charge cap, as long as the scheme ensures that the performance-based fee is in line with the definition set out in the 2023 Regulations and this guidance.

56. The pre-agreed rate or amount is often referred to as a hurdle rate, other variants of this term can be used such as ‘preferred return’. We refer to the pre-agreed rate as a hurdle rate in this guidance, but other terms are acceptable, providing that they can be:

a. An agreed rate – level of outperformance above a relevant benchmark/index that allows for appropriate comparison - before a performance-based fee is paid out. This could be a variable rate, such as a published financial performance index that will vary based on the index’s published constituents or may consist of a blend of more than one index or (the most commonly encountered hurdle) may simply be a compound rate of interest applied to net investment in a fund from time to time.

b. An amount – this could be a fixed amount. This is commonly a fixed percentage amount, or a series of fixed percentage amounts.

57. Performance-based fees only become due when that pre-agreed rate or amount is exceeded.

58. Before schemes agree with the fund manager to the investment proposition, they must have given full consideration to how the rate or amount directly links to the net benefit return scheme members could receive.

59. Schemes should also consider if the rate is appropriate to the type of assets being invested in, the fund’s strategy and the economic outlook and the level of return that might be achieved through similar funds that do not charge performance-based fees.

60. The rate or amount will influence how the fund manager is incentivised, so for example a high rate or amount may incentivise the fund manager to take more risk to try and achieve that hurdle e.g., a 15% hurdle rate would mean that the manager needs to deliver performance above that level before the performance-based fee commences, whereas a 5% hurdle rate would incur the performance-based fee at lower levels of performance.

61. To compare a hurdle rate of 5% and 15% would require details of how the fund invests, as higher return targets typically require more risk to be taken which implies a greater chance of high returns as well as the potential for high losses. The appropriate hurdle rate or amount is for the trustee or manager of the scheme to agree having considered the options outlined by the fund manager, considered these in context of the fund’s peer group, with consideration for the scheme’s overall investment strategy and on taking professional advice.

62. Schemes should engage with the fund manager and their advisers to consider their preferred structure for the agreed rate or amount of return, the level that it is set at, and may wish to look at scenarios to ensure that the level is understood in context of potential performance-based fees paid and their impact on member outcomes. Schemes may choose to review pre-agreed terms after entering into an investment with a specified performance-based fee where justified, for example, to reflect changes that were unforeseen at the outset. Changes to pre-agreed terms that become frequent, or for purely commercial reasons, may imply that the terms are not pre-agreed and so the performance-based fee structure may not be considered to be within the specified structure set out in the 2023 Regulations and this guidance.

63. It is possible to invest in assets that include a performance-based fee through a fund of funds structure. A fund of funds is a portfolio that predominantly invests in other collective investment schemes (constituent funds). If one or more of the constituent funds has, or will have, a performance-based fee component to their charges, the nature of each of the constituent funds’ performance-based fees must be considered in order to determine where it meets the criteria of a specified performance-based fee and thus can be excluded from the charge-cap calculation.

64. As with a single fund with a specified performance-based fee, trustees must be assured of the nature of the arrangements regarding the agreed rate or amount that triggers a performance-based fee within those fund of funds arrangements. This should be set out in the investment policy of the fund of funds to which the trustees and managers agreed when they invested into the fund of funds. Before trustees agree with the fund manager to the investment proposition, trustees must also have considered how the rate or amount directly links to the net benefit scheme members could receive.

When performance-based fees are measured

65. The specified performance-based fee will be calculated by the performance over a pre-agreed period of time. This pre-agreed period of time, or measurement period, is a pre-determined time period between two consecutive points over which performance-based fees are accrued. For some funds, the period may be that between two consecutive valuation points (for example, a fund may compare net asset value figures from time to time to calculate investment returns and the proportion of that which makes up the performance-based fee). Whereas for others, such as closed-ended funds, it may be the time between the drawdown of funds (and there may be more than one such date) and a distribution or other payment by the fund. Note that the measurement period may differ to the payment period, covered in the next section.

66. The measurement period can be set to reflect the characteristics of the underlying assets given the assets are often illiquid. By their nature, illiquid assets are not listed on an exchange and so there is not a readily available quoted price. Therefore, measurement periods could be monthly, quarterly, annually, or longer. However, performance-based fees could still apply to funds that are valued on a daily basis and fund managers may devise fund types and valuation periods that blend the requirements of investors, such as DC schemes, with the characteristics of the invested assets.

67. An example of an investment that could have a valuation period of annual or longer, might be a large national infrastructure project that will take many years to design and build before it can then deliver utility. An example of an investment with more frequent valuations, which could be weekly or monthly, could be short term credit provided to small and medium businesses.

68. Schemes should consider the appropriateness of the proposed valuation frequency with the fund manager and their independent advisers.

When performance-based fees are paid

69. The payment period, also sometimes known as the crystallisation period, is the timing point at which the fund manager is paid any performance-based fees that they are due.

70. The payment period is often set to coincide with when underlying physical assets are developed and then sold, or credit assets mature, as that relates to the fund’s cashflow and an appropriate time at which payments can be made.

71. However, payment is not always made to the fund manager as cash, they could for example be paid with units of the fund in question, taken from the investor’s unit allocation. This can alleviate the need to have cash available over the life of fund, with the manager only receiving cash at such time as the underlying fund assets are sold.

72. To note, the payment period will not always align with the valuation period. The trustees should work with the fund manager to develop a suitable period over which performance can be measured, and over which payment is then made.

Fairness for members

73. Trustees should work with fund managers to consider how performance-based fees should be charged in such a way to ensure fair allocation towards members. This is particularly important in open-ended funds, whereby members can enter/ exit the fund at various points and may not always benefit from periods in the investment cycle where there is positive performance

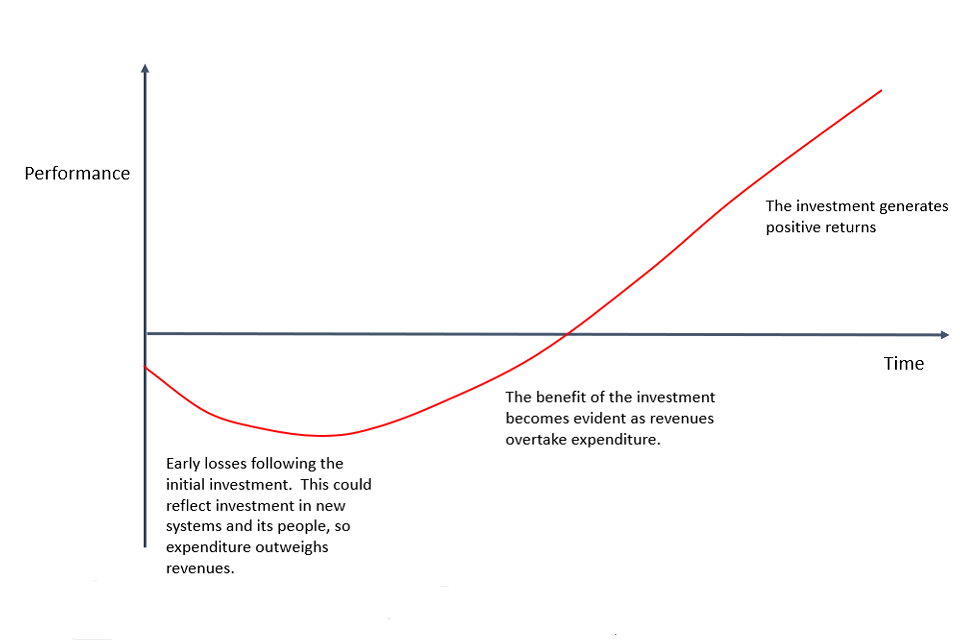

Fund journey example

Consider an example of a private equity investment where the returns can be characterized by their profile which is often called the “J-curve” effect. This J curve effect is being used as an example to illustrate member fairness, it is not an endorsement of J curve performance profiles or their use, for example, in DC schemes, the merits of which would have to be considered strategically by trustees and their advisers.

Fund journey example

Consider a scheme that invested over the full J curve.

-

A member that was in the scheme before the investment was made, but left just after the initial investment, would have suffered the costs of the investment but not enjoyed the benefits of the performance that followed.

-

A member joining at the bottom part of the J curve would have missed the worst of the poor returns and benefitted from the positive performance.

-

A member that was invested throughout the J curve would have experienced performance midway between the two previous members.

Trustees should be aware of the potential profile of returns that may lead to material differentials in outcomes by participation periods of members. Some assets can be more prone to this pattern of returns, with mitigations such as the scheme selecting its investment period or making several overlapping investments.

Another differential based on member participation is if the payment period differs to the valuation period. For this J curve example, if there are performance-based fees that are paid with a delay to the valuation point, a member could join near the end of the investment (the right-hand side of the J curve) and may have to pay those fees without having benefitted from the returns.

This J curve example is not representative of the timing or pattern of returns of all funds with performance-based fees but is illustrative of the type of challenges they can present, compared to funds with just fixed management fees. The potential for high expected returns and so high fees, particularly compared to what many money purchase schemes use as the staple of their default funds, could lead to large differentials in member outcomes, with regards to impact on member outcomes versus fees paid.

74. Trustees should work with fund managers and their advisers to ensure that the spread of cost/benefit is fair for all scheme members, with respect to the measurement and payment of performance-based fees. We would expect this advice to be holistic, so as well as including an evaluation of an investment with performance-based fees, it would consider the use of such investments over the evolution of the scheme’s investment strategy and consider the benefits such investments may bring to the investment strategy as well as possible compromises or complexities, such as those arising in relation to fairness to members.

75. Trustees may also find it useful to utilise industry guides[footnote 14] published in 2022, which provide advice on addressing member fairness regarding performance-based fees. These guides provide other key considerations for DC pension scheme decision makers, when investing in illiquid assets through their default arrangements.

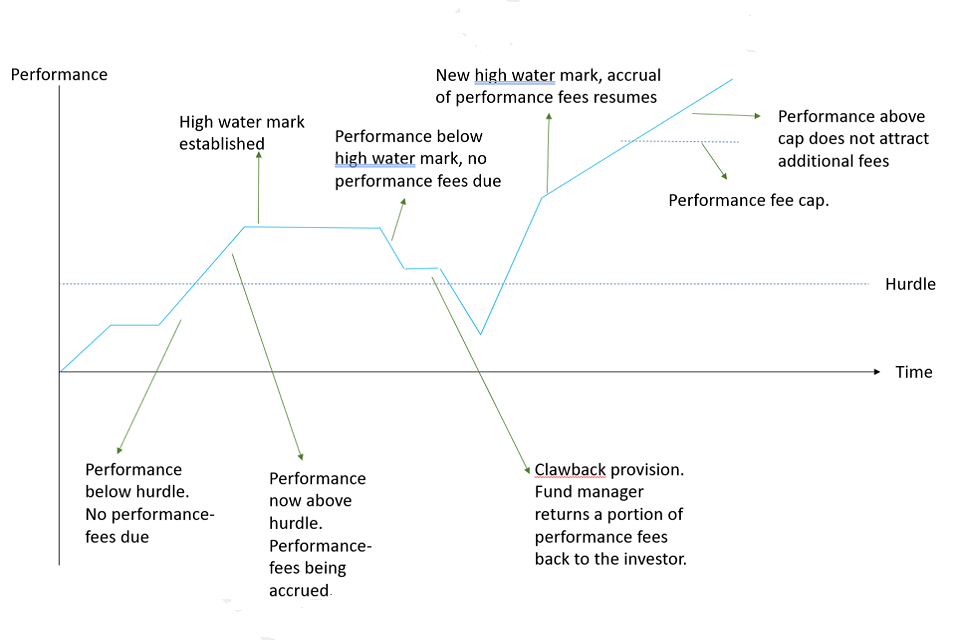

Volatility of returns and performance-based fees

76. The 2023 Regulations require that specified performance-based fees structures must include mechanisms that offer protections to pension schemes and their members. This is so fund managers are not taking excessive risk or being paid twice for the same level of performance or for performance which turns out to be impermanent.

77. Some of the more common mechanisms that can provide protection are provided below, but this is not an exhaustive list or reflective of terminology that is in universal use.

-

High water mark - a protection mechanism for investors to ensure that the fund manager only receives performance-based fees for generating additional levels of performance. This avoids an investor paying performance-based fees repeatedly on the same level of performance during periods of volatility.

-

‘Whole fund’ structures – in certain closed-ended structures the manager is only entitled to performance-based fees to the extent that all the fund’s investments, when taken as a whole and once realised, provide sufficient returns to allow investors to receive back all their initial investment, plus any hurdle or similar threshold. This prevents the manager retaining a reward for early successful investments where those are then followed by later losses that cumulatively exceed the extent of the fund’s initial gains.

-

Clawback mechanism – this is a provision that requires fund managers to pay back previously received performance-based fees (net of tax) if the fund manager subsequently underperforms in future time periods. Trustees may consider that this helps to align member and fund manager interests and provide some mitigation should a period of poor performance ensue after previous gains. Such mitigation is only in respect of fees. The capital that has been invested is still at risk.

-

Escrows – performance-based fees to which the manager is entitled may be placed into an escrow account for a period of time and only become accessible to the manager once the fund has achieved a certain level of consistent or permanent performance.

-

Caps – there can be a cap on the total amount of performance-based fees that could be due. Trustees may decide that a cap would help ensure that the fund manager’s incentive for performance was in line with their expectations, and not far beyond which could entail taking more risk than the trustees would be expecting. Trustees may decide that a cap also helps when presenting performance-based fees to members, assuring members as to the total amount of fees that could be due. At the same time, a cap on performance-based fees may also disincentivise the fund manager to expend effort on generating further strong performance once the cap has been reached.

Performance-based fee structure example

78. The example below illustrates how some of the performance-based fee mechanisms may be combined and work together. Trustees and managers of schemes should take appropriate advice on how the fees can be applied.

Performance-based fee structure example

Pro-rated and smoothing performance-based fees

79. As a result of adding specified performance-based fees to the list of those charges excluded from the charge cap, options allowing schemes to pro-rate or smooth the effects of performance-based fees for part year members or over multiple years, respectively for the purposes of the charge cap that can be currently applied[footnote 15] are to be repealed.

80. However, with respect to the multiple year smoothing option, the 2023 regulations do allow for any schemes, currently making use of this, to continue up to the date which is 5 years after the end of the first charges year in which regulatory provisions were brought in allowed this to be applied.

Disclosure reporting

81. The 2023 Regulations amend the Administration Regulations and the Disclosure Regulations to require that the amount of any specified performance- based fees incurred in relation to each default arrangement (if any) or, in the case of a qualifying collective money purchase scheme, the scheme during the scheme year, is stated as a percentage of the average value of the assets held by that default arrangement or collective money purchase scheme during the scheme year. This information must be included in the annual chair’s statement and made available on a publicly available website.

82. Schemes should consider carefully how they present the monetary amount of performance-based fees in the annual chair’s statement as there may be periods when their magnitude differs considerably to the other fees paid on their default fund or other industry default funds. There may also be periods when the year-on-year changes are very significant.

83. Schemes may want to consider supplementing the regulatory disclosures with detail to add context to performance-based fees, such as,

a. The assets and funds to which the specified performance-based fees relate.

b. The application of the hurdle rate, and additional mitigations used that make up the fee structure such as high-water marks, caps, clawback etc.

c. A timeline of how performance-based fees are measured and paid.

84. Additional information may also include for example, previous years’ information, and additional narrative to relate to the fund’s performance and how that is expected to impact member outcomes.

85. Depending on the performance-based fee timing, schemes could also consider providing additional disclosure at periods more frequently than annually. This could be relevant if that aligns with measurement or payment periods, and if there may be a desire to disclose information in relation to fair treatment of members that may join or leave a scheme, or alter contributions, part way through a scheme year.

86. This additional information could take the form of literature or interactive graphics to help members understand how performance-based fees have been considered by their trustees, including such scenarios of fees that are in the disclosures in question. The chair’s statement does not need to contain this additional information and could refer the reader to an alternative outlet, such as a web page that is freely available to members. This could be bespoke to the scheme or could refer to the fund manager’s website, which may be relevant for pooled funds where the same information could be relevant for multiple schemes.

Fund sheets

87. We suggest that further information on performance-based fees could be reported to members in the normal course of reporting, for example by making use of guides and fund sheets. This would involve trustees working with fund managers to prepare a document that can be shared with members that could include examples of the types of assets that the fund will invest in and how the fund manager will manage those assets, to help members relate the activity of the fund manager to the potential fees becoming due.

88. We suggest that any fund sheet produced is updated annually, so that it can be used to explain performance-based fees that have been incurred, in context of the stage of the fund’s life cycle.

Value for Members

89. The 2023 Regulations require that trustees of relevant occupational DC schemes that do pay specified performance-based fees must assess the extent to which these represent good value for members in accordance with the provisions set out in regulation 25(1)(b) of the Administration Regulations (as amended by the 2023 Regulations).

90. Schemes with under £100m in assets under management are not required to include this as part of their extended value for member comparison against larger schemes exercise set out in regulation 25(1A) of the Administration Regulations.

-

A relevant scheme is an occupational pension scheme which provides money purchase benefits or collective money purchase benefits (excluding money purchase benefits solely related to Additional Voluntary Contribution (AVC) arrangements), which is not a scheme with only one member, a relevant small scheme or an executive pension scheme ↩

-

Collective money purchase schemes are commonly known as collective defined contribution schemes. ↩

-

As defined in regulation 3A of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015. Where there is sectionalisation, the information on the assets held must be broken down by section. ↩

-

In accordance with “the Disclosure Regulations” ↩

-

The regulatory charge cap limit is 0.75% which applies to the default funds of occupational pension schemes used for automatic enrolment and to qualifying collective money purchase schemes. ↩

-

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/2734/contents/made ↩

-

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2015/9780111128329/contents ↩

-

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2015/9780111128329/regulation/3 ↩

-

This sectionalisation might occur where it has been decided to adjust the design of the collective benefits offered to automatically enrolled employees going forward. The old section and new section would continue to be considered qualifying collective money purchase schemes and subject to these disclosure requirements. ↩

-

As set out in regulation 25A(3) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996, as amended by the 2023 Regulations. ↩

-

See paragraph 33 of Completing the annual Value for Members assessment and Reporting of Net Investment Returns ↩

-

https://www.plsa.co.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Policy-Documents/2022/Investing-in-less-liquid-assets-key-considerations.pdf ↩

-

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2015/9780111128329/regulation/3 ↩