Government response to Automatic enrolment: Alternative quality requirements for defined benefits and hybrid schemes being used as a workplace pension

Updated 6 February 2024

Introduction

1. This document contains the findings of the 2023 review of the alternative quality requirements for pension schemes being used for automatic enrolment. Part of the review process included a call for evidence which ran from 15 May 2023 to 19 June 2023. The aim of this call for evidence was:

- to ascertain whether the government’s policy intentions in this area are continuing to be achieved

- to look at how the simplifications and flexibilities of the alternative quality tests work in practice

- to identify if any new issues have arisen since the last triennial review in 2020

Why have we carried out these reviews?

2. The Secretary of State is required to review the regulations made under powers in the Pensions Act 2008 which introduced the alternative quality requirements for pension schemes being used for automatic enrolment into workplace pensions. There are two statutory reviews set out in the legislation which must take place at no more than three-yearly intervals[footnote 1]. The last reviews were carried out in 2020.

3. Regulations made under section 23A of the Pensions Act 2008 cover the alternative quality requirement for defined benefit pension schemes and defined benefit sections of hybrid schemes (section 24(1)(b)). The legislation provides for a simpler alternative test that schemes and employers sponsoring defined benefit schemes can use to demonstrate that such a scheme is suitable to be used for automatic enrolment by meeting the relevant minimum quality requirements.

4. The findings of this review are set out from paragraph 30 onwards.

5. Section 28(2C) of the Pensions Act 2008 requires triennial reviews to be carried out into whether the test in subsection (2A) continues to be satisfied. The provisions of section 28 apply to schemes as set out in sub-sections (3), (3A) and (3B). The schemes listed in sub-section 3, cover money purchase schemes, Collective Defined Contribution schemes, personal pension schemes, hybrid schemes, and defined benefit schemes of a nature description under section 23A(1)(a).

6. The findings of this review are set out from paragraph 47 onwards.

Background to the reviews

7. Automatic enrolment into workplace pensions was introduced in 2012 to enable more people to save for their retirement and to make retirement saving the norm for most people in work. The law requires employers to enrol all their eligible[footnote 2] workers into a qualifying workplace pension scheme and pay pension contributions.

8. Employers who choose to use a defined benefit or hybrid pension scheme to meet their automatic enrolment duties must ensure their scheme meets the minimum quality requirements[footnote 3] set out in the Pensions Act 2008 and the accompanying secondary[footnote 4] legislation.

9. Up until 6 April 2016 a defined benefit scheme with its main administration in the UK could meet the quality requirements for a workplace pension scheme by:

-

being contracted out of the State Second Pension (also known as the Additional State Pension); or

-

meeting the test scheme standard (TSS) provided for in legislation and statutory guidance[footnote 5] which allow defined benefit schemes to demonstrate they meet the minimum necessary standard

10. The ‘test scheme’ is a hypothetical defined benefit scheme and, in simple terms, a scheme satisfies the TSS if it provides pension benefits broadly equivalent to those of the ‘test scheme’. Following the abolition of contracting-out (on 6 April 2016) only those defined benefit schemes that satisfy the TSS in relation to all relevant jobholders[footnote 6] could be used as a qualifying workplace pension scheme. The TSS remains an option for all employers.

11. In straightforward cases, Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) guidance sets out how employers can certify that their scheme meets the TSS. In more complex cases, the scheme actuary will need to certify the scheme.

12. In a public consultation in 2013[footnote 7] (followed by a further consultation in 2014[footnote 8], DWP invited views on whether there was a less onerous way for defined benefit schemes to demonstrate the quality requirement for the purposes of automatic enrolment. The majority of respondents expressed the view that the TSS was unnecessarily complex, and employers would benefit from the flexibility to use an alternative, simpler test.

13. Consequently, the framework for alternative quality requirement tests for defined benefit or hybrid schemes was introduced through the Pensions Act 2014 (which inserted section 23A into the Pensions Act 2008). Details of the operation of the alternative quality requirement tests are set out in regulations (made under section 23A(1))[footnote 9].

Policy intent

14. The policy objective behind both alternative quality tests is to provide a simpler mechanism for employers and their advisers to determine if defined benefit or hybrid schemes meet the quality requirements for automatic enrolment.

The alternative quality requirements for Defined Benefit (DB) and hybrid schemes

15. Since 1 April 2015, there have been two alternative tests of scheme quality available to employers offering defined benefit schemes or hybrid schemes to meet their automatic enrolment duties:

16. Test one: A test enabling schemes, which meet prescribed requirements, to use the money purchase quality requirements – based on meeting the existing quality requirements for defined contribution schemes, i.e. a minimum contribution equivalent to 8% of qualifying earnings (Section 20 of the Pensions Act 2008).

17. Test two: A ‘cost of accruals’ test – based on the cost to the scheme of the future accrual of active member benefits.

The alternative tests

Test one

18. This is a test enabling schemes which meet prescribed requirements to use the money purchase quality requirements.

19. In response to feedback from a public consultation in 2014, a test was introduced whereby a defined benefit scheme will be able to use the money purchase quality requirement for defined contribution schemes (Section 20 of the Pensions Act 2008).

20. To determine whether the scheme may apply this test, a number of conditions need to be satisfied:

(a) members’ benefits are calculated by reference to factors which include the contributions made to the scheme by, or on behalf of, the member

(b) the contributions in sub-paragraph (a) are converted, in accordance with scheme rules, as soon as reasonably practicable and no later than a month after receipt, into a right to an income for life

(c) the benefits payable to the member under the scheme become payable no later than the member’s State Pension Age

(d) following the conversion of the benefits in sub-paragraph (b), the amount of the members’ benefits cannot be reduced unless this is at the member’s request

(e) following any actuarial valuation, the trustees or managers have absolute discretion to use any excess funds to increase members’ benefits; and

(f) where benefits have been increased using the excess assets referred to in (e), they cannot be reduced except at the member’s request

Test two

21. This is the cost of accruals test. The cost of accruals test is based on the cost to the scheme of the future accrual of active member benefits. The test is normally applied at scheme-level and, broadly speaking, a defined benefit scheme (or defined benefit elements of a hybrid scheme) meets the quality requirement for automatic enrolment if the cost of providing the benefits accruing for, or in respect of, the relevant members over a relevant period would require contributions to be made of a total amount equal to at least a prescribed percentage of the members’ total relevant earnings over that period[footnote 10]. In other words, the cost of providing benefits would at least require the minimum levels of contribution rates prescribed in legislation.

22. Prescribed percentages in relation to members’ earnings are set at a level that broadly represents the cost of providing the benefits under the TSS. To maintain the existing quality standards for schemes, section 23A of the Pensions Act 2008 provides that the percentage prescribed in regulations cannot be below the 8% total contribution rate required for a qualifying defined contribution scheme.

23. The cost of accruals test generally applies at a scheme-level. However, where there is material difference in the cost of providing benefits for different groups, the test is applied at a benefit scale level.

Analysis under section 28 Pensions Act 2008

24. DWP has conducted analytical modelling of the section 28 test, based on the Office for National Statistics’ Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), which is the primary data source on employees’ earnings. Our analysis examines all jobholders, regardless of whether they are contributing into a pension. The analysis has been used to determine if total and employer contributions in these alternative schemes are exceeding minimum contributions under Automatic Enrolment. Because these tests have been satisfied for over 90% of jobholders for each of the alternative sets analysed, the alternative scheme quality requirements have been met.

The Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) test

25. For the 2023 Review, we have included the CDC test for the first time. CDC schemes were introduced by the Pension Schemes Act 2021 and the legislative framework for single and connected employer CDC schemes came into effect on 1st August 2022. Under that framework employers who choose to use a CDC scheme to meet their AE duties are required, as with other schemes, to ensure that the scheme meets the minimum quality requirements for qualifying schemes under the Pensions Act 2008.

26. It therefore made sense to include a review of the AE quality test which applies to CDC schemes as part of the Triennial Review of alternative AE tests thus syncing all the review timings (AE and CDC) together on the same cycle.

27. CDC schemes need to satisfy the quality requirement for UK money purchase schemes under section 20 of the Pensions Act 2008 in order to be a qualifying scheme for AE purposes, or the alternative quality requirements for a money purchase scheme set out in regulation 32E of the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Automatic Enrolment) Regulations 2010 or the alternative quality requirements which have been prescribed for CDC schemes in regulation 32EA of those regulations. Regulation 32EA was inserted by paragraph 2 of Schedule 7 to The Occupational Pension Schemes (Collective Money Purchase Schemes) Regulations 2022.

28. The alternative AE quality test for single or connected employer CDC schemes, taking all relevant jobholders together, looks at monetary contributions by, or on behalf of, or in respect of those jobholders over the certification period, and these are assessed against prescribed percentages of their total relevant earnings over that period. DWP intends that the test will be applied to all relevant jobholders together, unless there is a material difference in the cost of providing rights to benefits to different groups (as set out in the regulations).

29. This alternative quality requirement for CDC schemes will operate alongside the valuation requirements in the CDC regulations. The Call for Evidence included a question which allowed respondents to share their views on the CDC test.

The 2023 Reviews

Review of Alternative Quality Requirements for defined benefit and hybrid schemes (Pensions Act 2008, Section 23A)

30. The review process fulfils the requirement set out in legislation to periodically reconfirm that government policy intent continues to be achieved, i.e. to deliver broad administrative easement for the majority of pension schemes that would otherwise have to fall back on the TSS.

31. DWP carried out a call for evidence from 15 May to 19 June 2023 to seek the views of interested stakeholders on the effectiveness of the alternative quality tests, and whether issues have arisen that would make this deregulatory easement ineffective for schemes that choose to make use of it. We thank our stakeholders for their thoughtful responses.

32. DWP received responses from 8 organisations with an interest in this aspect of the automatic enrolment framework. In addition, we received an informal response suggesting that AE certification guidance should be reviewed and updated to include greater reference to CDC schemes.

To what extent have policy objectives been achieved?

33. Through a series of questions, the call for evidence asked whether or not the alternative tests were continuing to deliver, in broad terms, a simplified mechanism for demonstrating a pension scheme met the quality requirements.

34. On the basis of the evidence gathered, we have concluded that, in broad terms, the alternative quality tests continue to provide a simplified option and are suitable for the majority of DB and hybrid schemes who use them. We have also concluded that the CDC test remains sufficient, and the policy objective continues to be met.

Are the alternative quality requirements for defined benefit and hybrid schemes continuing to deliver the intended simplifications and flexibility for sponsoring employers and pension schemes that are unable to use the TSS?

Is there anything sponsoring employers or pension schemes want to bring to DWP’s attention about the operation of the alternative quality requirements, in particular regarding previously unforeseen issues when compared to the TSS?

35. Overall, respondents felt that the alternative quality requirements do continue to deliver the intended simplifications to the AE testing regime. Respondents were content with the ‘cost of accruals test’, as this provided a simpler version of the TSS.

We are satisfied that the alternative quality requirements remain adequate’. Pensions Management Institute.

36. A minority of respondents did suggest a carve out exemption for legacy DB schemes with 1 to 2 active members from the cost of accruals test, as 90% could be a hard definition to meet, alongside issues surrounding the definition of pensionable pay – and some schemes are unable to utilize one of the five definitions. However, this was a minority of respondents, and it is the view of DWP that most DB and hybrid schemes using the Cost of Accruals test can slot into the existing definitions of pensionable pay. Although the easements are less straight forward for a number of schemes who use them, we are not yet persuaded that changes to the framework need to be made at this time, given schemes continue to operate the alternative test(s).

37. It remains the position of DWP as stated in 2020, that making further bespoke arrangements for schemes to address the concerns raised about pensionable pay definitions is not appropriate, due to the risk of complicating what should be a simplified test. Schemes may also find the TSS to be more appropriate in some of these circumstances. DWP would welcome detailed evidence from industry of circumstances where the definitions act as barriers to conducting the tests or worked proposals of definitions which they deem to be more suitable.

38. Some respondents raised, as they did in 2020, questions around capped pay. As many respondents noted in their call for evidence submissions, DWP continue to believe that in these circumstances, schemes should look to see if the TSS will be the more appropriate test to meet their automatic enrolment obligations.

Definition of relevant members

39. A couple of respondents raised – as they did in 2020 – questions around the issue of the definition of ‘relevant members’ under the cost of accruals test, in particular if they had opted down (opted to decrease or cease pension saving) but still received benefits from another qualifying scheme for the same employer. The legislative definition of ‘relevant members’[footnote 11] does not allow employers to exclude members who have ‘opted-down’, to make contributions below the qualifying rate, from their cost of accruals assessment as this creates a possible risk that a scheme fails to meet the cost of accruals test.

40. DWP’s position remains that we wish to avoid adding further layers of complexity to the alternative tests, as the TSS is intended for those circumstances where definitions of earnings and calculations of contribution rates remain complex for example, because they are formed of multiple definitions. This is because, the scheme must be able to certify in order to ensure that those workers being placed into the scheme are enrolled into a scheme that does meet the AE quality standard. Therefore, if the alternative tests are not appropriate, the TSS is the alternative option to meet the criteria. We will, however, continue to monitor these concerns and will look to respond to any new issues that may be raised over the next three years.

The expansion of the AE framework

41. Most respondents noted The Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Act[footnote 12] could have a potential impact on the alternative quality tests – including the impact on Reg 32M (10) of SI 2010/772[footnote 13]. In considering the implementation of the 2017 Review measures, a detailed consultation and impact assessment will take place, this will pay due regard to any potential interactions with the alternative tests. Stakeholders will have the opportunity to share their views further during this consultation.

The legislation is not prescriptive about who should apply the alternative quality requirements. In practice, who is carrying out the tests: the employer (i.e. self-certification) or its professional advisers?

42. Overall, who carries out the alternative tests can vary on a case by case and scheme by scheme basis. The consensus is that most employers would have sought the views of an actuarial adviser. However, there is a mixture dependent on if the case is simple – in which an employer may apply the tests or larger more complex schemes, which would use an actuary or a professional advisor.

In our experience, it is invariably the scheme actuary for the cost of accruals test, as evidenced in their report on the triennial actuarial valuation’ Lane Clark & Peacock LLP.

43. Therefore, the consensus from respondents is in line with the evidence gathered in the 2020 reviews and that the current flexibility which is allowed by not defining who should carry out the tests is appropriate. We do not intend to introduce a prescriptive definition.

Does the alternative quality requirements for CDC schemes remain appropriate for single and connected employers, and does it remain appropriate for the new types of CDC schemes?

44. The majority of respondents are satisfied with the new quality requirements for CDC schemes. Most noted that there should be care when considering changes to the CDC tests as CDC provision begins to broaden beyond single or connected employer schemes. In particular, as we develop a legislative framework to accommodate whole-life multi-employer schemes, consideration should be given as to how they meet their automatic enrolment obligations and if further changes to the testing regime should be made.

We see the current alternative CDC test as appropriate for schemes that may operate under the current regulations’. Willis Towers Watson.

45. DWP agrees with this assessment, and as government policy surrounding CDC schemes develops further, we will of course, consider the impact on the CDC test to ensure new scheme types will be able to certify their compliance with the AE quality requirements.

Responses with proposals outside of the questions asked

46. The Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) and Universities UK jointly raised the issue of the potential development of new, future tests, to enable schemes to meet their automatic enrolment obligations through alternative models. DWP has had constructive engagement with USS and will continue to engage with them further at the appropriate time as their modelling develops[footnote 14].

Analysis of the Alternative Quality Requirements for Section 28 schemes

47. The statutory review requires that each of the alternative quality requirements are satisfied for at least 90% of jobholders. That is, if every scheme satisfied these requirements, both employer and total contributions would be equal to or exceeding minimum contributions under automatic enrolment.

48. In this analysis, we present figures for the proportion of jobholders in different sets for whom total contributions are at least as much as under minimum contributions on qualifying earnings. The minimum contributions required for the 3 sets are outlined in table 1.

Table 1: Minimum employer and total contribution level requirement for Set 1,2 and 3 at different staging periods[footnote 15]

| Set | Contribution levels until 5th April 2018 | Contribution levels from 6th April 2018 until 5th April 2019 | Contribution levels since 6th April 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The scheme must provide for at least a 3% contribution of pensionable earnings (inclusive of at least a 2% employer contribution) for all of the relevant jobholders in the group or in the scheme. The pensionable earnings of the jobholder must be equal to, or more than the jobholder’s ‘basic pay’. | The scheme must provide for at least a 6% contribution of pensionable earnings (inclusive of at least a 3% employer contribution) for all of the relevant jobholders in the group or in the scheme. The pensionable earnings of the jobholder must be equal to, or more than the jobholder’s ‘basic pay’. | The scheme must provide for at least a 9% contribution of pensionable earnings (inclusive of at least a 4% employer contribution) for all of the relevant jobholders in the group or in the scheme. The pensionable earnings of the jobholder must be equal to, or more than the jobholder’s ‘basic pay’. |

| 2 | The scheme must provide for at least a 2% contribution of pensionable earnings (inclusive of at least a 1% employer contribution) for all of the relevant jobholders in the group or scheme. The pensionable earnings of the jobholder must be equal to or more than the jobholder’s basic pay. Total pensionable earnings of all relevant jobholders (taken in aggregate) to whom this set applies must constitutes at least 85% of their total earnings. | The scheme must provide for at least a 5% contribution of pensionable earnings (inclusive of at least a 2% employer contribution) for all of the relevant jobholders in the group or scheme. The pensionable earnings of the jobholder must be equal to or more than the jobholder’s basic pay. Total pensionable earnings of all relevant jobholders (taken in aggregate) to whom this set applies must constitutes at least 85% of their total earnings. | The scheme must provide for at least an 8% contribution of pensionable earnings (inclusive of at least a 3% employer contribution) for all of the relevant jobholders in the group or scheme. The pensionable earnings of the jobholder must be equal to or more than the jobholder’s basic pay. Total pensionable earnings of all relevant jobholders (taken in aggregate) to whom this set applies must constitutes at least 85% of their total earnings. |

| 3 | Total contributions of at least 2% of the jobholder’s earnings (including an employer contribution of at least 1%) for each relevant jobholder in the group or scheme. | Total contributions of at least 5% of the jobholder’s earnings (including an employer contribution of at least 2%) for each relevant jobholder in the group or scheme. | Total contributions of at least 7% of the jobholder’s earnings (including an employer contribution of at least 3%) for each relevant jobholder in the group or scheme. |

Methodology

49. Our analysis uses the latest available data, up to 2021, from the Office for National Statistics’ Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), which is the primary data source on employees’ earnings. Our analysis examines all jobholders, regardless of whether they are contributing into a pension. A jobholder is defined as:

- an employee working in Great Britain

- aged 16 to 74

- earning above the lower earnings limit (currently £6,240)

50. For these jobholders, we compare their minimum notional pension contributions under the automatic enrolment framework against their notional contributions under each alternative requirement.

Results

Set 1

51. Table 2 shows that since the introduction of automatic enrolment in 2012, certification under Set 1 would have delivered at least as good an outcome for total contributions for over 90% of jobholders during all three staging periods.

Table 2: Proportion of jobholders for whom total contributions under Set 1 (contributions on basic pay from pound one) are at least as much as under minimum contributions on qualifying earnings, 2012 to 2021

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3% basic pay from pound one at least as much as 2% of qualifying earnings | 99% | 99% | 99% | 99% | 99% | 99% | - | - | - | - |

| 6% basic pay from pound one at least as much as 5% of qualifying earnings | - | - | - | - | - | - | 97% | - | - | - |

| 9% basic pay from pound one at least as much as 8% of qualifying earnings | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 96% | 96% | 96% |

Source: DWP estimates derived from ONS ASHE, GB, 2012 to 2021

52. From 2018 onwards, there has been a slight decrease in the proportion of jobholders for whom Set 1 would deliver at least as good an outcome as minimum contributions on qualifying earnings. This has fallen from 99% in 2017 to 96% between 2019 and 2021. This is attributable to the phased increases in minimum contribution rates in April 2018 and April 2019.

53. Across all years, for an individual with gross pay equal to basic pay, the test for Set 1 is automatically satisfied. This is because basic pay would be greater than qualifying earnings and therefore, a greater percentage of the larger basic pay would be greater than a smaller percentage of the lower qualifying earnings. However, for an individual with gross pay greater than basic pay, satisfying the test for Set 1 depends on the amount of additional pay the individual receives.

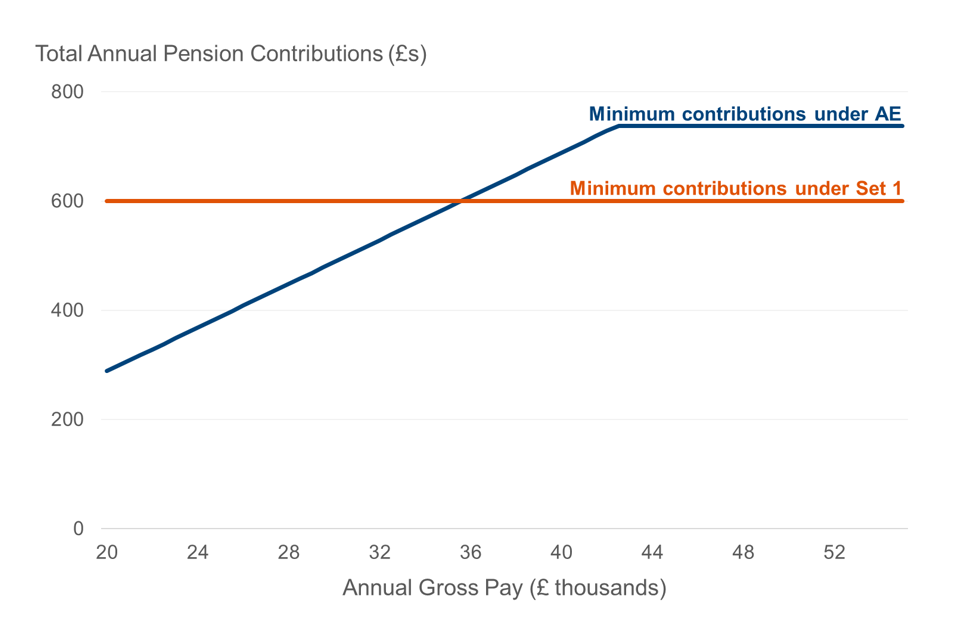

54. For example, consider an employee earning £20,000 basic pay per annum. The chart below shows how total pension contributions vary with gross pay, for an employee in 2012 with a basic pay of £20,000.

55. Up to the point of intersection at a gross pay of £36,000, the minimum contribution this individual would receive under Set 1 is greater than the minimum contribution they receive under automatic enrolment. Therefore, they satisfy the test for earnings up to £36,000.

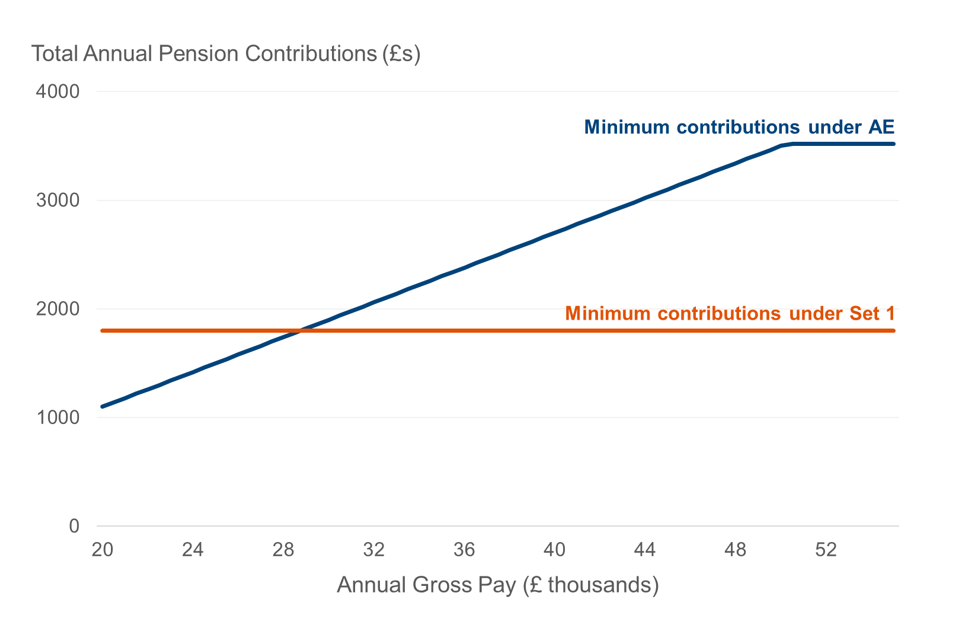

56. The following chart shows how total pension contributions vary with gross pay, for an employee in 2021 with a basic pay of £20,000.

57. An individual in 2021, despite having the same basic pay at £20,000, would now only satisfy the test if gross pay is less than £29,000. Because there is a greater likelihood of an individual with a basic pay of £20,000 earning above £29,000 in 2021, compared to earnings above £36,000 in 2012, they are more likely to fail this test in 2021.

58. For any employee under a Set 1 arrangement whose total contributions are at least as much as minimum contributions on qualifying earnings would be, the same is automatically true of their employer contributions.

59. Total contributions under Set 1 being greater than minimum contributions under automatic enrolment implies that between 2019 and 2021, 9% of basic pay is greater than 8% of qualifying earnings. With a minimum employer contribution of 4%, it follows:

- 4% of basic pay is greater than 4/9 x 8% of qualifying earnings

- This is equivalent to 32/9% (=3.6%) of qualifying earnings, which is greater than 3% of qualifying earnings

- This is therefore greater than the minimum employer contributions required under AE

60. The same argument can be presented between 2012 and 2019.Therefore, since the total contributions element of the statutory test is met for Set 1, the employer contributions element of the test is also met.

Set 2

61. An individual receives at least as good an outcome under Set 2 as under minimum contributions on qualifying earnings, for both total and employer contributions, if and only if their entire basic pay is at least as much as qualifying earnings. Table 3 shows that since the introduction of automatic enrolment in 2012, this has been the case for over 90% of jobholders. Therefore, both elements (i.e. total contributions and employer contributions) of the quality tests are met for Set 2.

Table 3: Proportion of jobholders with basic pay from pound one at least as much as qualifying earnings, 2012 to 2021

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of jobholders with basic pay from pound one at least as much as qualifying earnings | 91% | 92% | 92% | 92% | 92% | 92% | 92% | 93% | 94% | 93% |

Source: DWP estimates derived from ONS ASHE, GB, 2012 to 2021

62. Certification for a scheme under Set 2 also requires that the total pensionable earnings of all relevant jobholders (taken in aggregate) in each scheme to whom this Set applies must constitute at least 85% of their total earnings.

63. As ASHE is a survey of employee jobs, it is not possible to use it to look at total employer aggregates.

64. Therefore, for the purpose of our analysis we assume that this condition of Set 2 plays no part. However, any additional condition on a scheme can only increase necessary contributions under that scheme. Therefore, by not accounting for this, the true proportion of jobholders that would receive at least as good an outcome under Set 2 would be even greater than our estimate. Since our estimates are greater than 90% when only accounting for condition 1, by also including condition 2, these proportions would have been even greater.

Set 3

65. For all jobholders, gross earnings are greater than qualifying earnings. This automatically means the employer contributions test is met for all years, and the total contributions test is met up to 2018.

66. Table 4 also shows that since 2019, certification under Set 3 would have delivered at least as good an outcome for total contributions for over 90% of jobholders.

Table 4: Proportion of jobholders for whom total contributions under Set 3 (contributions on gross pay from pound one) are at least as much as under minimum contributions on qualifying earnings, 2019 to 2021

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7% of gross pay from pound one at least as much as 8% of qualifying earnings | 99% | 100% | 99% |

Source: DWP estimates derived from ONS ASHE, GB, 2019 to 2021

67. Therefore, both elements of the quality test are met for Set 3. Certification under Set 3 would have delivered at least as good an outcome for total contributions for over 99% of jobholders.

Tests for Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) schemes

68. Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) schemes have been recently introduced. It is not presently possible to perform separate analysis of the tests for these CDC schemes. Currently, Royal Mail is the only employer seeking to establish a single or connected employer CDC scheme and as their scheme exceeds the 8% minimum defined under the automatic enrolment framework, employees in this CDC scheme satisfy the requirements of the test.

Equalities Analysis

69. The following tables compare the breakdown - by age group and gender - of jobholders who would receive a sub-par outcome against the equivalent overall population in 2021. We do this by comparing the outcomes of jobholders contributing under Sets 1, 2 and 3 as opposed to minimum contributions on qualifying earnings.

70. Age and gender are the only protected characteristic in relation to the public sector equality duty that are captured in ASHE. No other data sources are readily available to analyse the impact of alternative quality requirements on other protected characteristics. The number of people negatively impacted by the alternative quality requirements is small, in comparison to the total number of jobholders. The analysis conducted for the quality tests assesses the number of jobholders who would be potentially worse off if they were in an alternative scheme compared to having minimum contributions under qualifying earnings, but many of these will be individuals who are not in fact saving under an alternative scheme arrangement[footnote 16]. Therefore, any potential positive or negative impact on protected groups is likely to be small in comparison to the total number of jobholders in each protected group.

Distribution of jobholders by gender, 2021

71. For Sets 1, 2 and 3, a smaller proportion of jobholders who would have worse outcomes than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings are female than in the overall population of all jobholders. Higher earning jobholders are more likely to be worse off under the different sets when compared against minimum contributions on qualifying earnings. Because there are a greater number of males in higher salaried roles, they are more likely to be negatively impacted by using the alternative requirement definitions.

Table 5: Gender breakdown of jobholders, 2021

| Gender | Jobholders who would be worse under Set 1 than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings | Jobholders who would be worse under Set 2 than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings | Jobholders who would be worse under Set 3 than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings | All jobholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 75% | 75% | 74% | 56% |

| Female | 25% | 25% | 26% | 44% |

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2021

Distribution of jobholders by age, 2021

72. For Sets 1, 2 and 3, the distribution by age of jobholders who would have worse outcomes than with minimum contribution on qualifying earnings is similar to the distribution by age for the overall population of all jobholders.

Table 6: Age breakdown of jobholders, 2021

| Age Group | Jobholders who would be worse under Set 1 than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings | Jobholders who would be worse under Set 2 than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings | Jobholders who would be worse under Set 3 than with minimum contributions on qualifying earnings | All jobholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 to 21 | 4% | 4% | 0% | 5% |

| 22 to 29 | 18% | 18% | 15% | 18% |

| 30 to 39 | 23% | 24% | 32% | 25% |

| 40 to 49 | 23% | 23% | 27% | 22% |

| 50 to 59 | 23% | 23% | 20% | 21% |

| 60 to 69 | 8% | 8% | 5% | 8% |

| 70 to 74 | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2021

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100%, due to rounding

Note: Percentages supressed where ASHE sample size is small (less than 20).

Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED)

73. The Secretary of State has paid due regard to the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) as set out in section 149[footnote 17] of the Equality Act 2010 in carrying out this review. Overall, the alternative quality requirements are designed to offer schemes and their sponsoring employers simplified tests to demonstrate scheme quality. The policy is intended to encourage employers to continue using legacy pension schemes to discharge their automatic enrolment duties. Therefore, continuing to leave the tests unchanged is likely to ensure that schemes are still available to workers covered by AE who have protected characteristics and is not expected to have any material negative impacts on protected groups

74. The PSED is on an ongoing duty and DWP is committed to continually monitor the impacts of its policies. We will use the next triennial review to make a further assessment of whether there are any unintended consequences or adverse impacts on protected groups arising from this policy. In addition, we will continue to monitor feedback from stakeholders and individuals through our normal feedback channels to assess the broader impact of the policy.

Conclusion

75. Overall, considering the evidence gathered and the analysis set out in this response, the Secretary of State has concluded that:

- the alternative quality requirements for UK defined benefit schemes set out in regulations made under section 23A(1) of the Pensions Act 2008 should continue to remain in place without changes at this time

- the tests set out in section 28(2A) of the Pensions Act 2008, continue to be satisfied

76. The evidence and analysis demonstrate that the overall objectives of the alternative quality requirements to act as simplified quality tests for relevant pension schemes are being met and in broad terms continue to operate as intended and that continued stability is essential in reducing the burdens on employers through changes to the testing regime.

77. DWP acknowledges the suggestions for technical changes to the tests and corresponding regulations, particularly around the cost of accruals test, definitions of pensionable pay and relevant members. As well as updating the guidance for DB and hybrid schemes and including updated CDC guidance. As we seek to broaden CDC provision to include whole-life multi-employer schemes, we will engage with stakeholders as further consideration is given to what would be an appropriate test for these new types of CDC scheme.

78. DWP has had constructive engagement with USS and will continue to engage with them further at the appropriate time as their proposals develop[footnote 18].

79. As the AE framework continues to evolve, due regard will be paid to how the alternative quality tests interact with the implementation of the 2017 Review measures. There will be opportunities for stakeholders to share their views on the implications of AE expansion on the alternative quality requirements when the consultation is conducted on implementing the 2017 Review.

80. Ahead of making changes, DWP will seek to understand, where and to what extent there might be scope for proportionate easements in the tests, while maintaining the integrity of the automatic enrolment framework and continuing to deliver the simplified operation of the alternative quality tests for the benefit of DB and hybrid schemes.

81. The next statutory reviews will take place in 2026.

Glossary

Hybrid schemes

82. Hybrid schemes are defined, for the purposes of automatic enrolment only, as schemes that are neither money purchase nor defined benefits. They generally have elements of both types of benefits, and depending on the type of scheme involved, they may need to satisfy a combination of the defined benefits quality requirement (including the alternative quality requirements prescribed under Pensions Act 2008 section 23A) and the money purchase quality requirement, or they may only need to satisfy either of the requirements[footnote 19].

Contracting out

83. Up to and including 5 April 2016, individuals were able to ‘contract out’ of the Additional State Pension. This meant that workers and employers could pay less NI contributions into the NI fund. It was not possible to contract out of the Basic State Pension. Individuals could only opt out (‘contract out’) of the Additional State Pension if they were part of a private pension – such as a workplace or personal pension scheme – that could accrue similar benefits. New State Pension was introduced by the Pensions Act 2014 for those reaching state pension age on or after 6 April 2016, and contracting out was abolished under the Act.

Defined benefit contracting out

84. Many workplace pension schemes where the pension is linked to the individual’s earnings contracted out all of their scheme members as part of their scheme rules. The new State Pension has replaced the previous Basic and Additional State Pension for those reaching state pension age on or after 6 April 2016 and ended contracting out for defined benefit pension schemes.

Terms in the ‘cost of accruals’ test[footnote 20]

85. Under the test, a defined benefits scheme (or defined benefits element of a hybrid scheme) satisfies the quality requirement if the cost of providing benefits accruing for or in respect of the relevant members over a relevant period would require contributions to be made of a total amount equal to at least a prescribed percentage of the member’s total relevant earnings over that period.

Relevant members

86. Relevant members for the purposes of the cost of accrual test are the active members of the scheme of which the jobholder is a member. However, where there is or was a material difference in the cost of providing the benefits accruing for different groups of relevant members over the relevant period, then (subject to the transitional arrangement) the testing is carried out separately for each sub-group (i.e. benefit scale). The actuary, having considered a range of factors, will determine whether there is a material difference in cost[footnote 21].

Relevant period

87. The relevant period is the period over which the cost of providing the accruing benefits is estimated. The period is normally to be taken from the most recent written report signed by the actuary, containing information about the cost of future benefit accrual by reference to a period which begins later than the date report takes effect[footnote 22].

Relevant earnings

88. The relevant earnings are the earnings which the scheme uses to determine pensionable earnings, provided that they are at least equal to or more than the earnings calculated using one or more of the definitions set out in the table below, for all of the relevant members. To ensure that the cost of providing benefits, under the alternative quality requirements, is broadly equivalent to the cost of similar benefits, under the test scheme standard, the earnings definitions have a corresponding prescribed percentage (see table below) contribution rate[footnote 23].

Earnings definition and corresponding minimum contribution rate[footnote 24]

| Legislative definitions: Relevant earnings must be at least equal to or more than: | Prescribed percentage of relevant earnings: Survivors’ pension benefits provided by scheme | Prescribed percentage of relevant earnings: Survivors pension benefits not provided by scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Qualifying earnings | 10% | 9% |

| Basic pay | 11% | 10% |

| Basic pay and, taking all of the relevant members together, the pensionable earnings of those members constitute at least 85% of the earnings of those members in the relevant period | 10% | 9% |

| Earnings | 9% | 8% |

| Basic pay above the single person’s basic State Pension or the Lower Earnings Limit | 13% | 12% |

List of respondents

- Association of Consulting Actuaries (ACA)

- Lane, Clark & Peacock LLP (LCP)

- Society of Pension Professionals (SPP)

- Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) & Universities UK (UUK)

- Willis Towers Watson (WTW)

- Pensions Management Institute (PMI)

- ISIO Group Limited

- Royal Mail

- Aon (Informal Response)

-

Section 23A(7); Section 28(2C) Pensions Act 2008 ↩

-

Section 3(1) Pensions Act 2008: a jobholder who is aged between 22 and pensionable age, earning over £10,000. ↩

-

Sections 21 to 23 Pensions Act 2008 ↩

-

S.I. 2010/772 ↩

-

Automatic enrolment: Guidance for employers on certifying defined benefit and hybrid pension schemes ↩

-

Jobholder is defined as a worker: (a) who is working or ordinarily works in Great Britain under the worker’s contract; (b) who is aged at least 16 and under 75; and (c) to whom qualifying earnings are payable by the employer (Section 1, Pensions Act 2008). ↩

-

Workplace pensions: proposed technical changes to auto enrolment ↩

-

Workplace pensions automatic enrolment: simplifying the process and reducing burdens on employers ↩

-

The Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Automatic Enrolment) Regulations 2010 ↩

-

Pension schemes under the employer duties: automatic enrolment detailed guidance for employers ↩

-

Used for the ‘cost of accruals’ test (Regulation 32M S.I. 2010/772). ↩

-

Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Act - Parliamentary Bills - UK Parliament ↩

-

The Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Automatic Enrolment) Regulations 2010 (legislation.gov.uk) ↩

-

Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Automatic Enrolment) Regulations 2010, S32E ↩

-

We do not have available data to assess the number of individuals actually saving under alternative scheme arrangements. ↩

-

Details of the duty are contained in the Equality Act 2010 (s149(1)) and (s149(7)). ↩

-

Section 99, Pensions Act 2008. ↩

-

Regulation 32M S.I. 2010/772. ↩

-

Regulation 32M S.I. 2010/772. ↩

-

Section 23A(2) Pensions Act 2008 ↩

-

Section 23A(2) Pensions Act 2008 ↩

-

Section 23A Pensions Act 2008 and Regulation 32M S.I. 2010/772. ↩