Police powers and procedures: Stop and search and arrests, England and Wales, year ending 31 March 2022

Published 27 October 2022

Applies to England and Wales

Frequency of release: Annual

Forthcoming releases: Home Office statistics release calendar

Home Office responsible statistician: Jodie Hargreaves

Press enquiries: pressoffice@homeoffice.gov.uk

Telephone: 0300 123 3535

Public enquiries: policingstatistics@homeoffice.gov.uk

Privacy information notice: Home Office Crime and Policing Research and Annual Data Requirement (ADR) data – Privacy Information Notices

1. Introduction

1.1 Key findings

There were 526,024 stop and searches conducted under section 1 PACE by police in England and Wales (including British Transport Police). This is a decrease of 179,888 (25%) compared with the previous year, and 8% below the level of stop and search in the year ending March 2020 (the year preceding the pandemic). The increased level of stop and search in the year ending March 2021 was partly due to proactive policing during COVID-19 lockdowns.

Of those 526,024 searches under section 1 PACE (and associated legislation), 66,772 led to an arrest. While the volume of arrests is 18% lower than the previous year, the arrest rate increased from 11% to 13%.

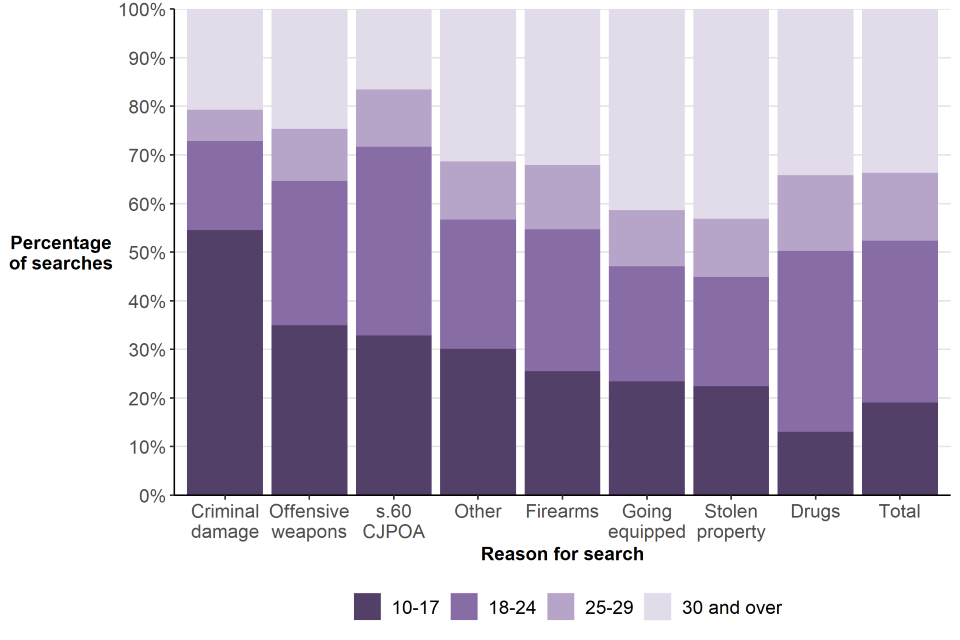

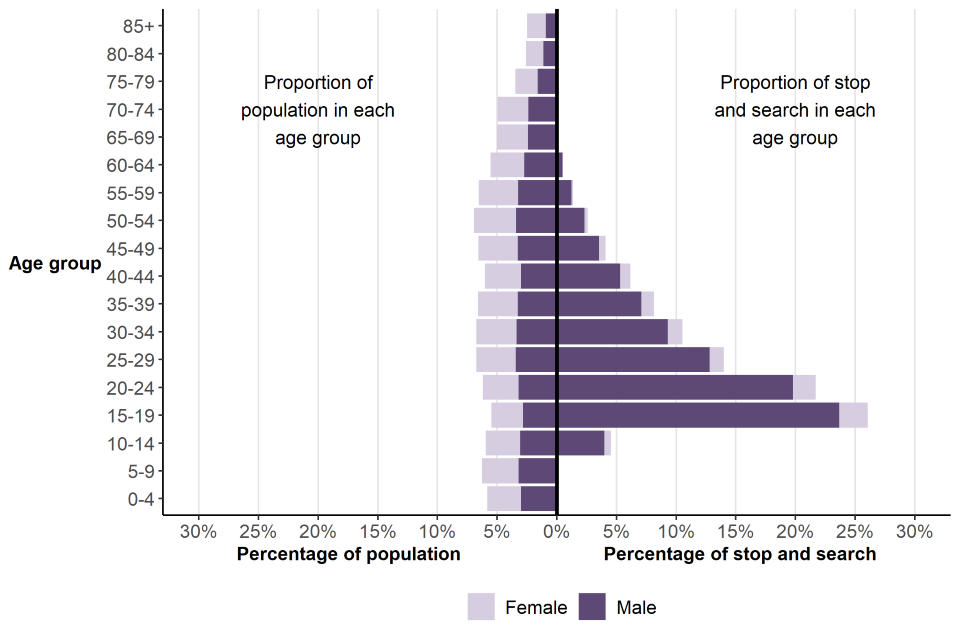

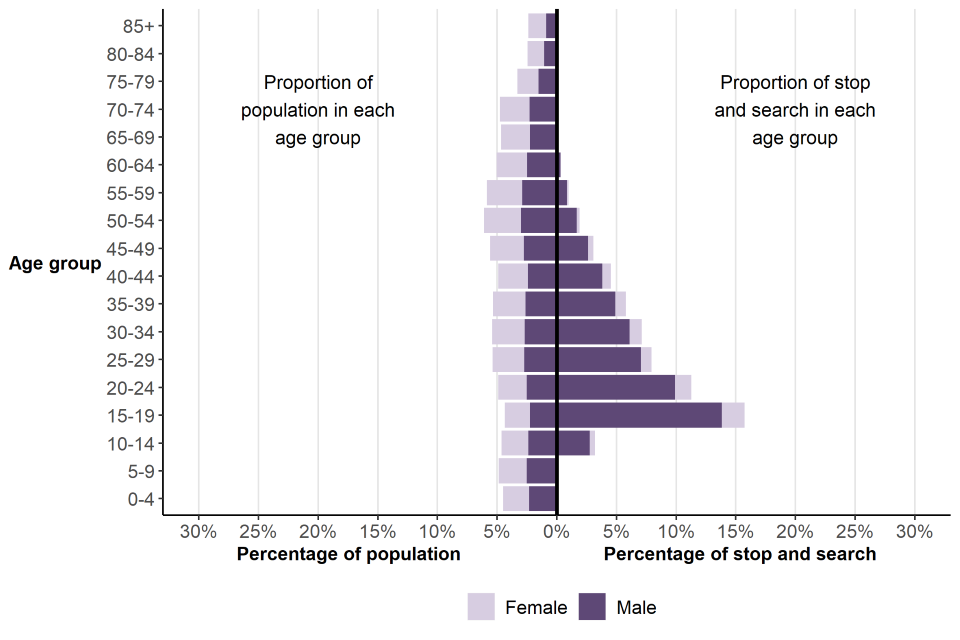

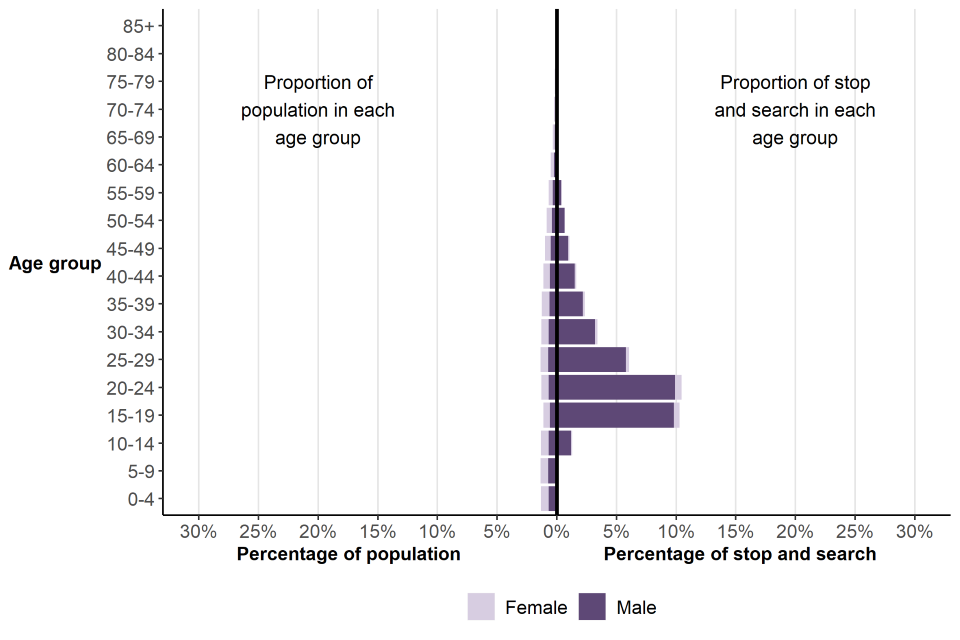

Two thirds (66%) of stop and searches in the year ending March 2022 were of males aged between 15 and 34, while this cohort comprises 13% of the overall population. Males aged 15-19 had the highest rate of stop and search, at 70 stop and searches per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2022.

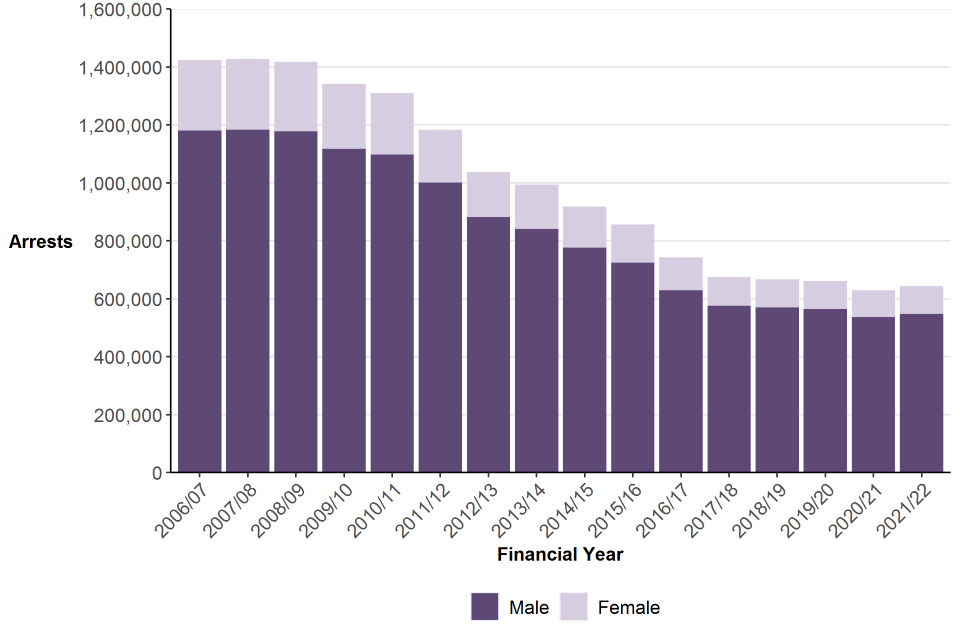

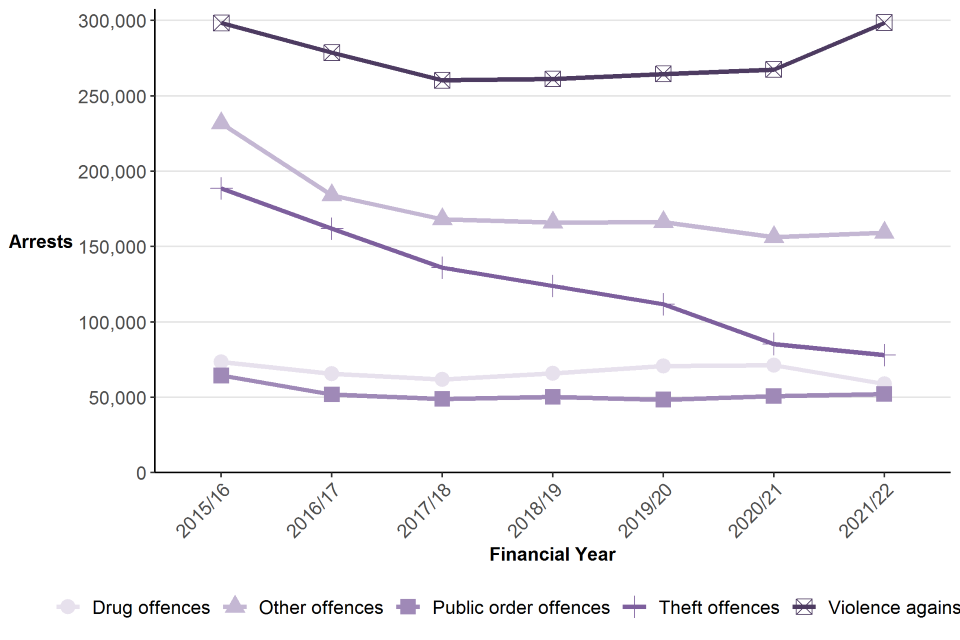

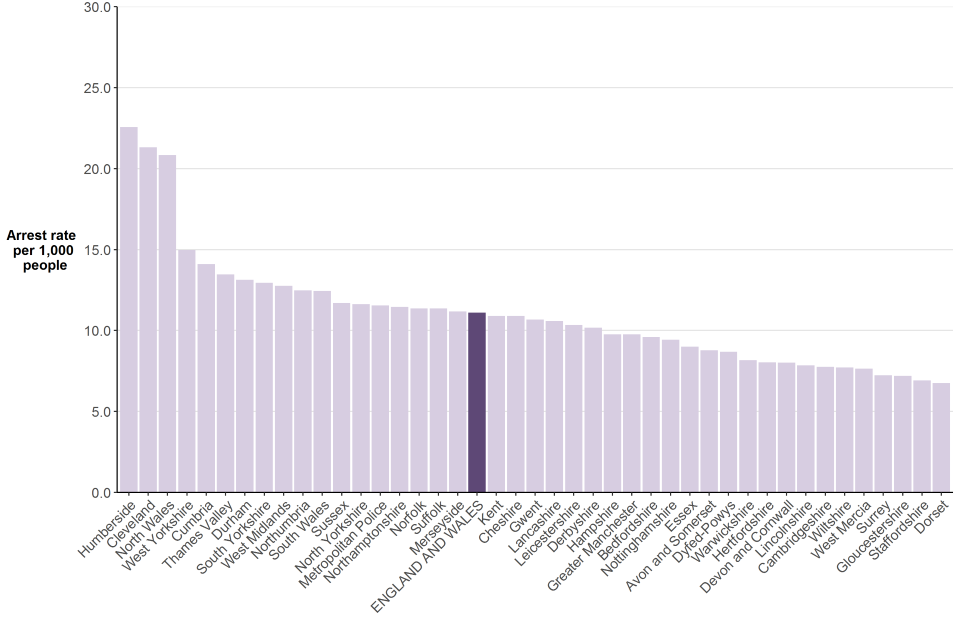

There were 663,036 arrests carried out by territorial police forces in England and Wales, an increase of 3% compared to the previous year in which there were 645,225 arrests, but down 2% from the year preceding the pandemic (ending March 2020).

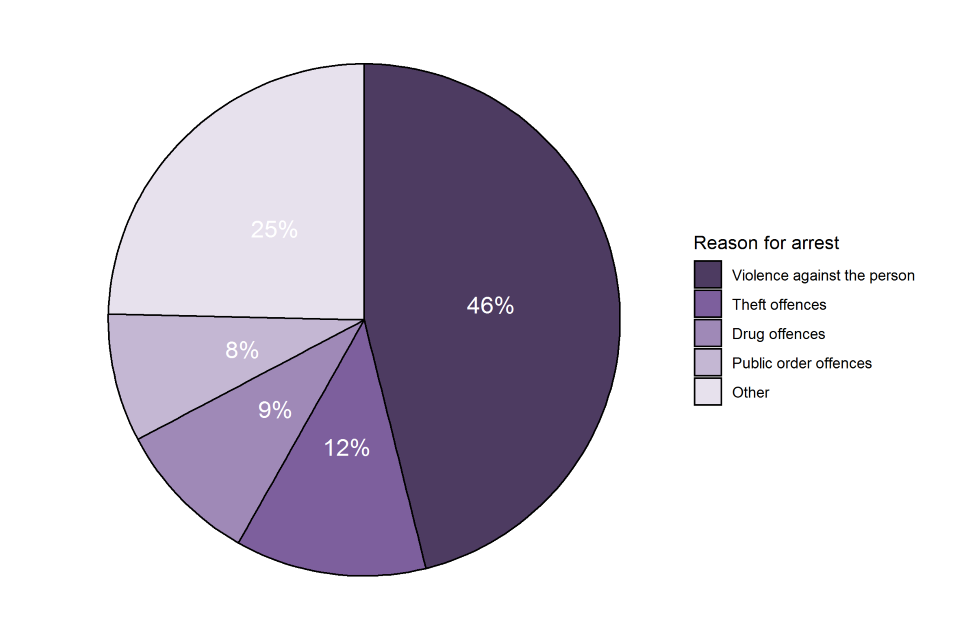

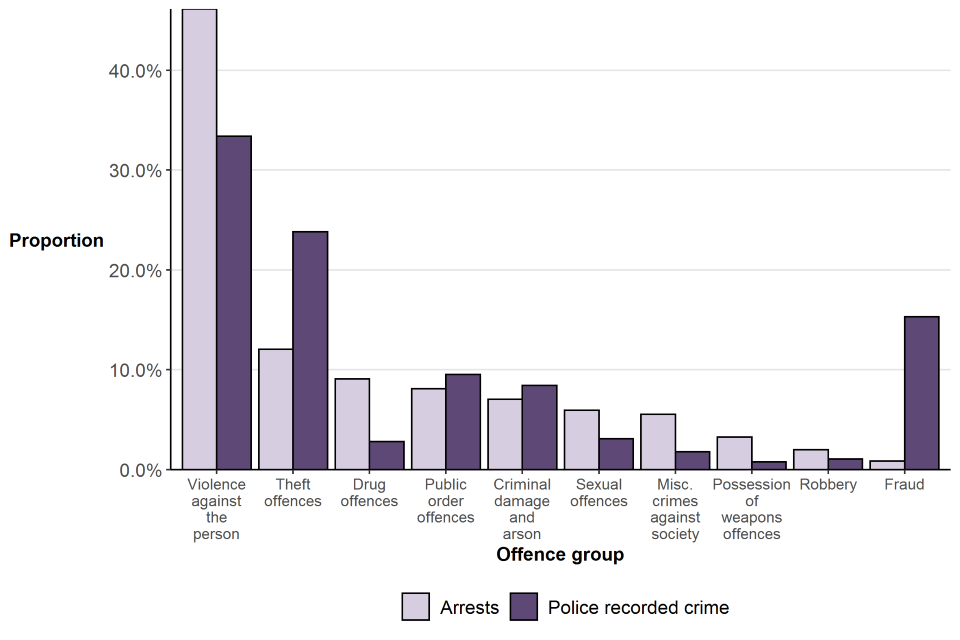

The change in the number of arrests in the latest year varied across different offence groups. Arrests for sexual offences increased by almost a third (32%), whereas arrests for drug offences fell by 17%. The overall volume increase in arrests was driven by a 12% increase (32,100) in arrests for violence against the person offences, the largest arrest type.

The pattern across forces was mixed, with 26 forces showing an increased number of arrests compared with last year while 17 police forces made fewer arrests.

1.2 Police Powers and Procedures statistics release

Prior to October 2021, statistics on stop and search and arrests were published as part of the annual ‘Police powers and procedures’ statistical bulletin, which covered other topics including the use of other police powers under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, fixed penalty notices and other outcomes for motoring offences, breath tests, pre-charge bail, released under investigation and detentions under the Mental Health Act. Given the volume and variety of topics covered, a decision was made in 2021 to split the release into two separate statistical bulletins.

This release is therefore the first of the two to be published on police powers in 2022 and contains statistics on the use of the powers of stop and search and arrest by the police in England and Wales up to the year ending 31 March 2022.

The second release, which is due to be published on 17 November 2022, will contain statistics on the use of other police powers under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, fixed penalty notices and other outcomes for motoring offences, breath tests, pre-charge bail, released under investigation and detentions under the Mental Health Act. It will also contain new data on the use of police powers to conduct a strip search.

1.3 Contents of this release

The stop and search section of this release contains information provided by the 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales, and the British Transport Police (BTP). It presents statistics on the:

- change in the use of stop and search throughout the years ending March 2021 and March 2022

- number of stop and searches carried out under a range of legislative powers, including:

- section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) and associated legislation

- section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994

- section 47A (previously section 44) of the Terrorism Act 2000

- reason for conducting a search

- outcomes following stop and search

- weapons found from stop and search

- ethnicity, sex and age of persons searched

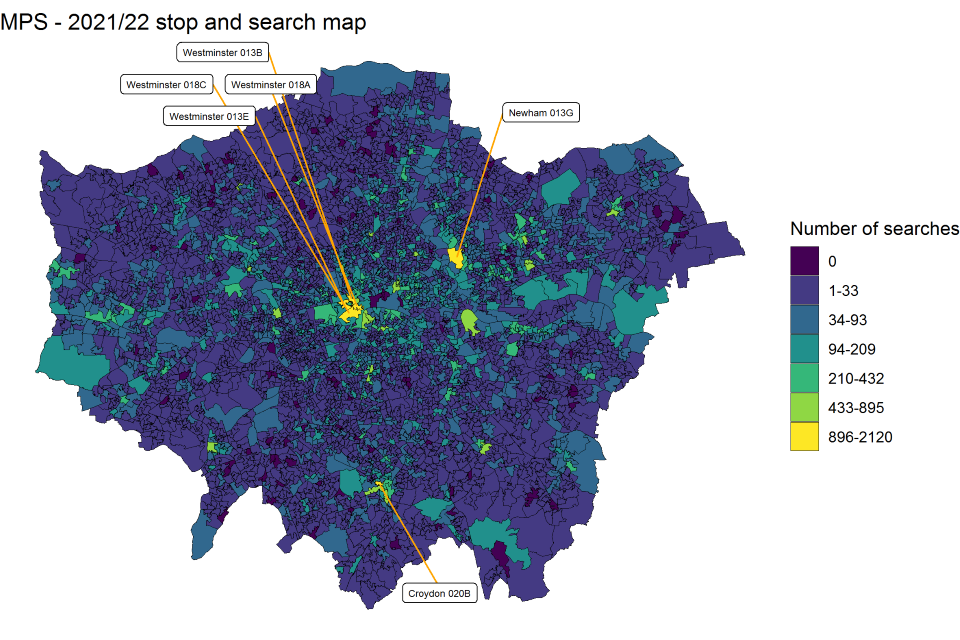

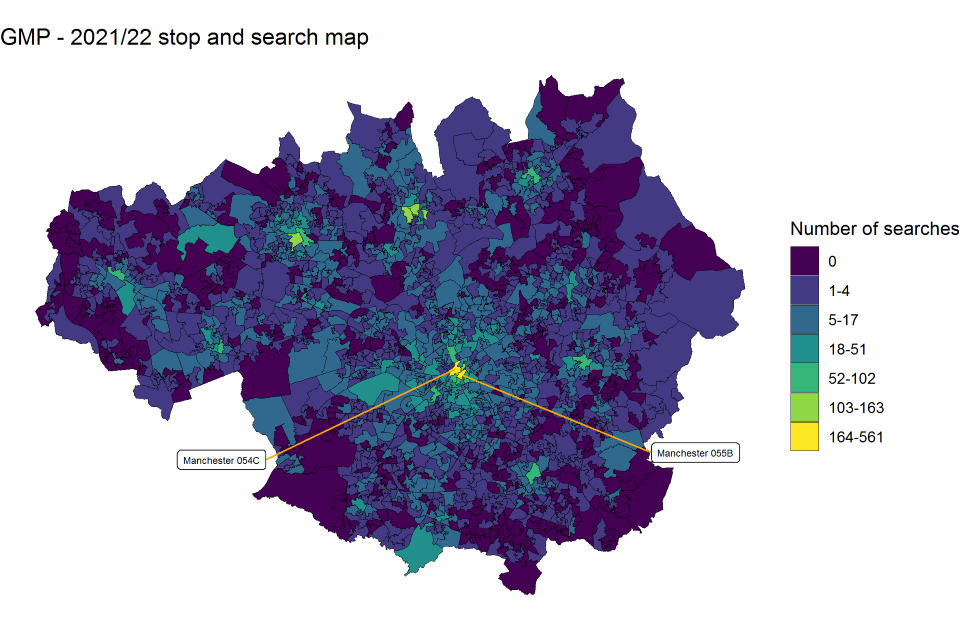

- hotspot analysis of stop and search locations in different parts of England

- relationship between stop and search and deprivation

The arrests section contains information provided by the 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales on a financial-year basis. It includes statistics on the:

- number of arrests for notifiable offences

- reason for which persons were arrested

- ethnicity, sex and age of those arrested

Key findings can be found at the start of each chapter.

1.4 Stakeholder engagement and new analysis in this release

For the first time in the year ending March 2021, the Home Office collected incident-level data on stop and search from police forces, meaning that each row of data relates to a single incident of stop and search. This publication contains data from the second year of the incident-level data collection.

The improved method of data collection, as well as the additional data collected, allows for more in-depth analysis of stop and search in England and Wales than was previously possible. More information on the change to the data collection is available in the year ending March 2021 release.

Furthermore, in light of this improved collection, and in response to the Commission for Race and Ethnic Disparities report, Home Office officials have worked with force representatives, stakeholders, and users of this publication to understand what more could be done to improve this release, which has led to additional analysis and outputs.

Moreover, analysts have developed a stop and search data tool to query the open data tables. This allows users with beginner Excel skills to produce customised data tables more easily.

Additionally, for the first time, data on stop and searches at Community Safety Partnership level is being published as part of this release. Those data can be found in the summary data tables.

Findings from an engagement survey conducted in Spring 2022 showed that most people who accessed these statistics did so as they had interest in policing in their local area. Additionally, the majority of respondents indicated that they found it easy to access and use the data tables that accompany the publication.

In line with the Code of Practice for Statistics and as part of our commitment to continuous development and improving the statistics, we invite users to provide feedback on the statistics and analysis presented in this bulletin and associated data tables. Users can contact Home Office statisticians at policingstatistics@homeoffice.gov.uk

1.5 National Statistics status

These statistics have been assessed by the UK Statistics Authority to ensure that they continue to meet the standards required to be designated as National Statistics. This means that these statistics meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, impartiality, quality and public value, and are fully compliant with the Code of Practice for Statistics. While the new method of data collection at the incident-level has yet to be specifically assessed, the source of the data (police stop and search records) remains the same and it is only the format in which the Home Office receives the data that has changed.

The Home Office worked closely with the UK Statistics Authority to improve information on the quality and limitations of the various datasets, and the ways in which the Home Office engages with users of the statistics. This is documented in the User Guide, which is published alongside this release.

Given the known issues around the quality of the data, statistics in this release on outcomes and whether the outcome was linked to the reason for the search (formerly referred to as ‘Best Use of Stop and Search’ data) are designated as Official Statistics, and not National Statistics.

2. Stop and search

Record-level data on stop and search from police forces, which means that each row of data relates to a single incident of stop and search, has been collected for searches since April 2020 This expansion of the data collection also covers information on the age and sex of the person searched, details on whether a weapon was found, the date and time information of the search, and the precise geographic location (using X-Y coordinates) of where the search was recorded.

Greater Manchester Police (GMP) were only able to provide robust data for part of the year ending March 2020. Their stop and search data has been removed from long-term year-on-year comparisons, to provide a consistent time series. However, they are included in comparisons using data solely from the year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022.

Key results

In the year ending March 2022:

There were 526,024 stop and searches conducted under section 1 PACE by police in England and Wales (including British Transport Police). This is a decrease of 179,888 (25%) compared with the previous year, and 8% below the level of stop and search in the year ending March 2020 (the year preceding the pandemic). The increased level of stop and search in the year ending March 2021 was partly due to proactive policing during COVID-19 lockdowns.

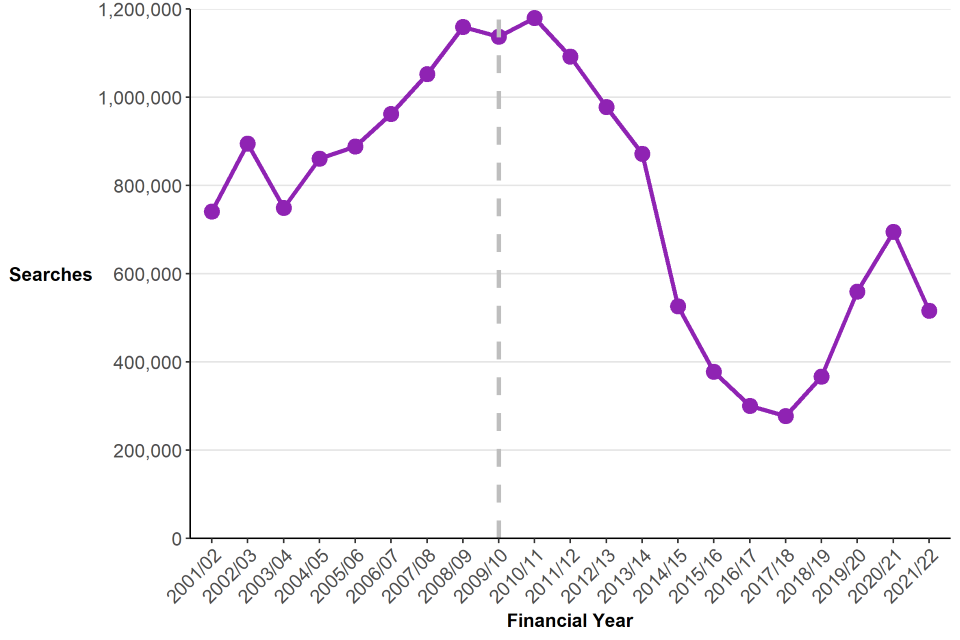

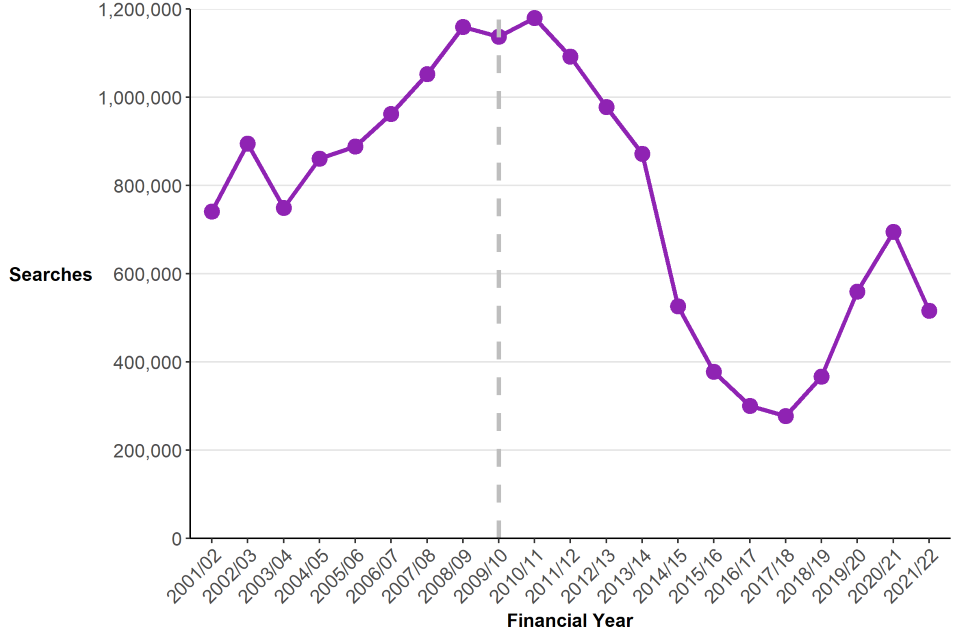

Figure 2.1: Number of stop and searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation, England and Wales, year ending March 2002 to March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_02, Home Office

Notes:

- Data prior to the year ending March 2010 do not include the British Transport Police (BTP). Data from the year ending March 2010 onwards includes the BTP but excludes GMP. Due to this, stop and search data before the year ending March 2010 are not directly comparable with more recent years. BTP usually account for between 1.0% and 2.0% of all and search across England and Wales per year.

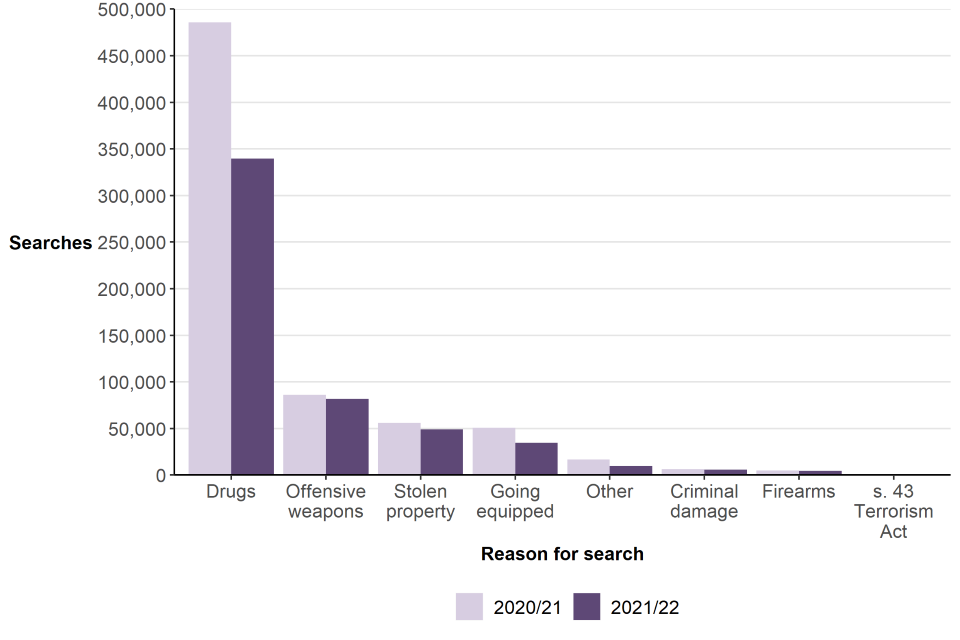

The decrease was driven by a 30% reduction in the number of searches for drugs, which fell from 484,917 in the year ending March 2021 to 339,662 in the year ending March 2022. The number of drugs searches in the latest year was only 5% below the number in the year ending March 2020 though. There were smaller decreases in searches for offensive weapons (down 5%) and firearms (down 4%), and a small increase in the number of criminal damage searches (up 1%).

Although overall searches under section 1 PACE (and associated legislation) are down by 8% in the year ending March 2022 compared with the year ending March 2020 (the year preceding the pandemic), 23 out of 43 police forces (including British Transport Police, but excluding Greater Manchester Police) saw an increase in the use of stop and search over that two-year period.

Of those 526,024 searches under section 1 PACE (and associated legislation), 66,772 led to an arrest. While the volume of arrests is 18% lower than the previous year, the arrest rate increased from 11% to 13% (since the decrease in the number of arrests is smaller than the fall in stop and searches). In 71% of stop and searches the outcome was recorded as needing ‘No further action’, similar to the previous year.

Police in England and Wales carried out 4,341 stop and searches under section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in anticipation of violence, a decrease of 52% compared with the number of searches under the same power in the year ending March 2021 (down from 9,002 to 4,341).

In total, police in England and Wales carried out 530,365 stop and searches, a decrease of 26% compared with the previous year (down 184,549 from 714,914 to 530,365). This is also 10% lower than the total number of stop and searches carried out in the year ending March 2020 (the year preceding the pandemic).

Two thirds (66%) of stop and searches in the year ending March 2022 were of males aged between 15 and 34, while this cohort comprises 13% of the overall population. Males aged 15-19 had the highest rate of stop and search, at 70 stop and searches per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2022.

Based on self-defined ethnicity, individuals from a black or black British background were searched at a rate 6.2 times higher than that of those from a white ethnic group (compared with 7.0 times in the previous year), across England and Wales. Individuals identifying as Asian or Asian British were searched at a rate 2.1 times that of those from a white ethnic group (compared with 2.4 in the previous year). Individuals identifying as mixed ethnicity were searched at a rate 2.3 times that of those from a white ethnic group (compared with 2.4 in the previous year). People from other ethnic groups were searched at a rate 2.7 times higher than that of those from a white ethnic group, the same as the previous year. These differences do not account for different likelihoods of being either a suspect or a victim of crime.

2.1 Introduction

This section presents the latest statistics on stop and searches conducted by the territorial police forces in England and Wales (as well as the British Transport Police) under three different legislative powers. These are:

- section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence (PACE) Act 1984 and associated legislation[footnote 1]

- section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (CJPOA) 1994

- section 47A (previously section 44) of the Terrorism Act (TACT) 2000

These powers allow police to search persons and vehicles without a warrant in specific situations. Details of the above legislation and the legislation associated with section 1 of PACE are included in the User Guide.

This section includes statistics on the:

- change in the use of stop and search throughout the last two years

- number of stop and searches, and subsequent arrests carried out under different legislation

- reason for the stop and search

- ethnicity of persons stopped

- sex of persons stopped

- age of persons stopped

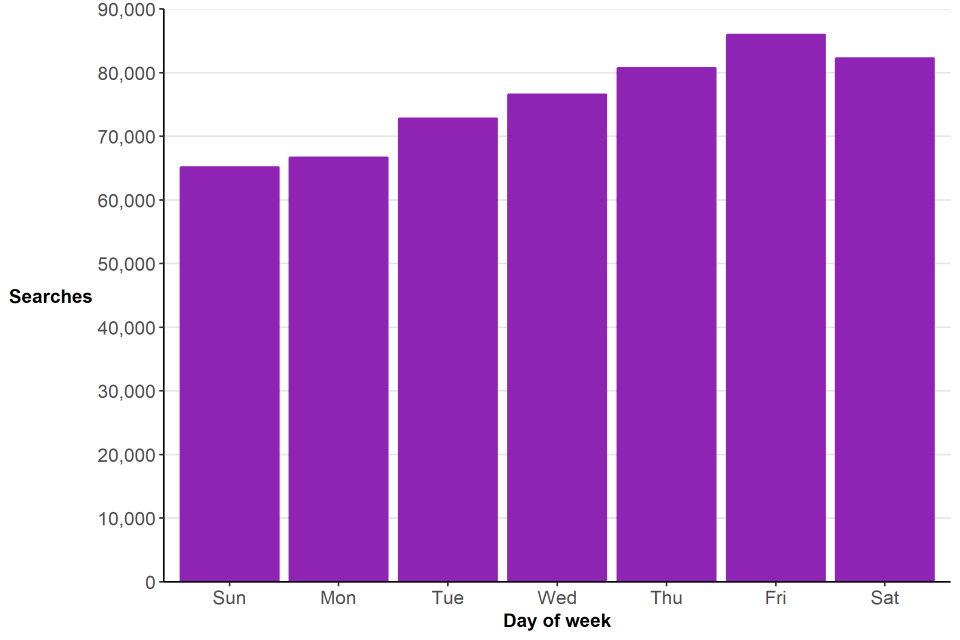

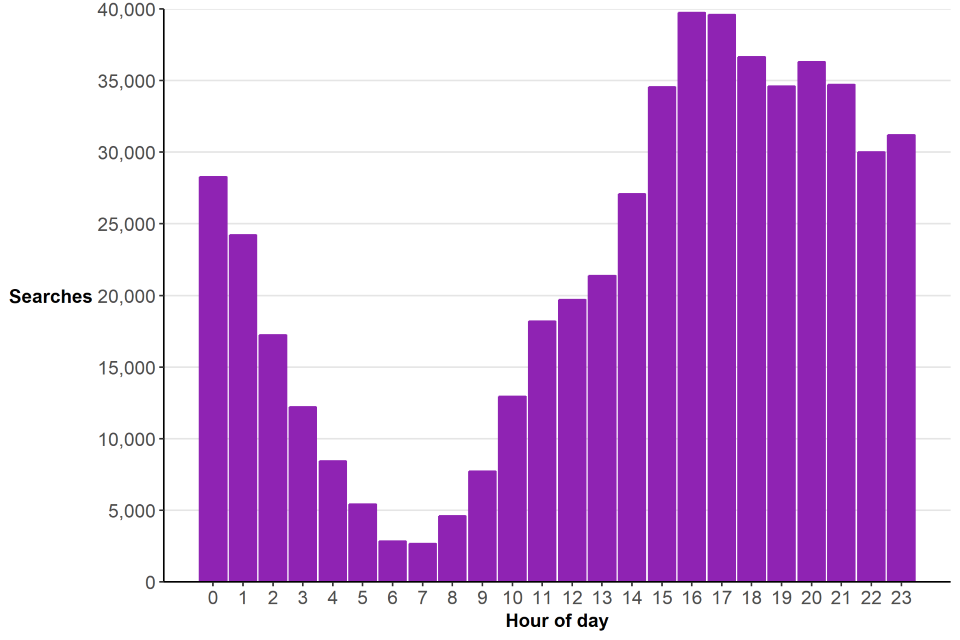

- day-of-week and time-of-day trends in stop and search

- stop and search hotspots

- an exploration of the relationship between stop and search activity and deprivation

Missing data

Following the transition from a legacy IT system to a new force system, Greater Manchester Police (GMP) were unable to provide data returns to the Home Office, including stop and search, for the full year ending March 2020. Data for the first quarter of the year ending March 2020 was collected prior to these issues, and is included in stop and search open data tables accompanying this publication. Work is ongoing to rectify and improve the information held on their system, and GMP have provided full data for the years ending March 2021 and March 2022. However, given ongoing improvement work, the data should be interpreted with caution, and is likely to be revised in future editions of these statistics. Additionally, as the force were only able to provide robust data for part of the year ending March 2020, Greater Manchester’s stop and search data has been removed from long-term comparisons in this chapter, to provide a consistent time series. However, their data is included in comparisons of the latest two years of data only.

2.2 Two-year trend in stop and search and the impact of COVID

Since the year ending March 2021, the Home Office collected information on the exact date on which stop and searches took place, enabling more insightful seasonal analysis on the data.

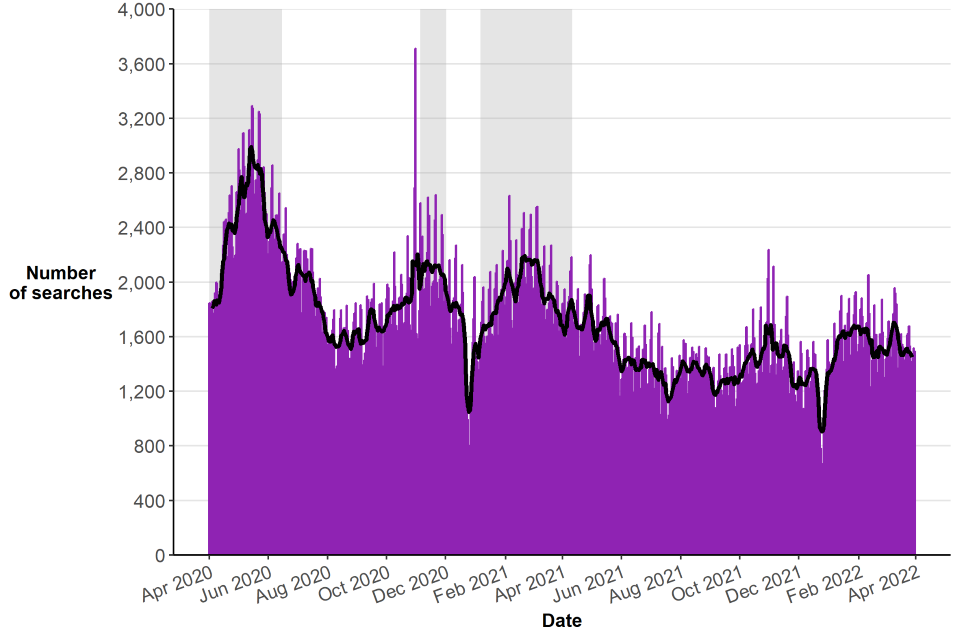

Figure 2.2 shows the daily and rolling 7-day average number of searches in the two years from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022, with periods in lockdown highlighted in grey. Whilst it is difficult to define exactly what constitutes a “national lockdown” given differing rules in different areas, and also when lockdowns start and finish, in this analysis “national lockdown” refers to dates when the majority of “non-essential retail” was closed.

Figure 2.2: Daily number and rolling 7-day average number of searches, year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_37, Home Office

Notes:

- 7-day rolling average is calculated by taking the average of the number of searches on the three days prior to a certain date, the date itself, and the three following days.

In the year ending March 2022, using the 7-day rolling average measure, the number of stop and searches peaked at 1,904 on 28 April 2021. By contrast, the 7-day rolling average had a much higher peak in the year ending March 2021, at 2,990 on 14 May 2020.

In the year ending March 2021, the peak number of searches in May 2020 coincided with the middle of the first national lockdown. During this period, persons or vehicles travelling against regulations were more visible, and may have been more likely to be stopped and searched. Police forces reported that engagement with people may have started in relation to lockdown movement restrictions, but then led to a stop and search, for example due to suspicion that the person was in possession of drugs. On average, there were 2,148 searches per day during lockdowns, compared with 1,755 during non-lockdown periods.

In the year ending March 2022, the day with the most searches was 31 October 2021, on which 2,237 searches took place. In the year ending March 2021, the day with the most searches was 31 October 2020, on which 3,713 searches took place. This shows the heightened level of policing activity during Halloween gatherings and celebrations.

In the year ending March 2022, the day with the fewest searches was 25 December 2021, on which only 401 searches took place. This date is the same low point in the year to March 2021 (518 searches on 25 December 2020). This reflects the fact that more people are likely to be at home on Christmas day, and there may also be fewer police officers on duty.

2.3 Section 1 PACE and associated legislation

In this section we refer to ‘section 1 PACE’ searches which includes other legislation such as searches conducted under section 23 Misuse of Drugs Act (1971). For examples of other legislation included under section 1 searches see the User Guide.

In the year ending March 2022 there were 526,024 stop and searches conducted under section 1 PACE by police in England and Wales (including British Transport Police). This reverses the trend from the last three years, in which the number of stop and searches had been increasing. The number of searches under section 1 PACE in the year ending March 2022 was down by 179,888 (or 25%) compared with the year ending March 2021 (705,912).

Given the unique circumstances of policing during the year ending March 2021, the following section compares the year ending March 2022 with the year ending March 2020, which was largely unaffected by the pandemic. Greater Manchester Police (GMP) were unable to provide complete data in the year ending March 2020, and are therefore excluded from this section.

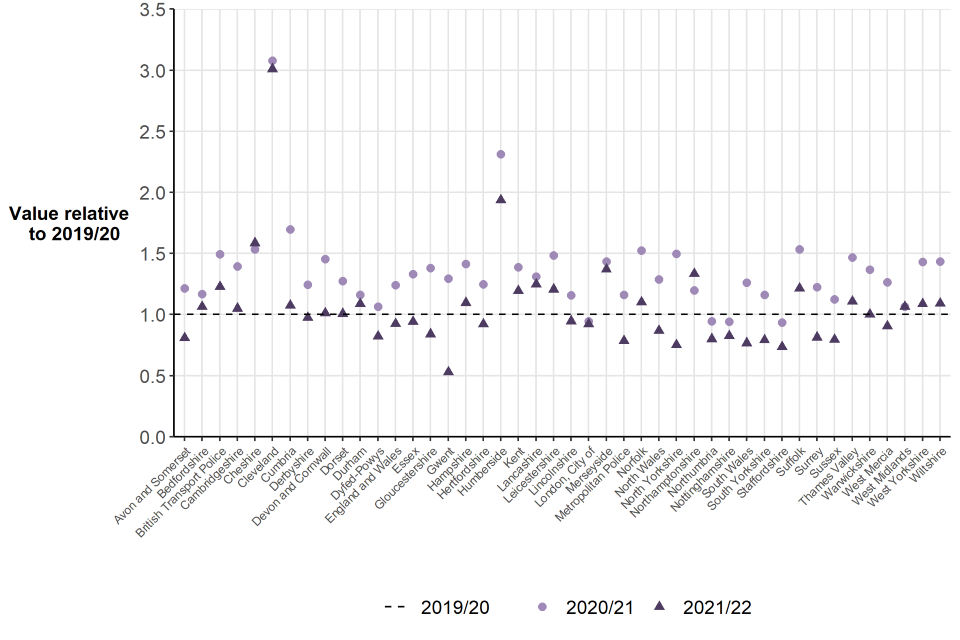

Excluding Greater Manchester Police, there were 516,642 stop and searches in the year ending March 2022, a fall of 8% compared with the year ending March 2020, in which there were 559,201 stop and searches under section 1 PACE. The change over this period has been driven by a reduction in stop and searches undertaken by the Metropolitan Police (down 22% from 268,384 to 210,347). Excluding Greater Manchester Police and Metropolitan Police, the number of stop and searches under section 1 PACE increased by 5% between the year ending March 2020 and year ending March 2022. Overall, 23 police forces in England and Wales have seen an increase in the use of stop and search over that two-year period, and 20 have seen a decrease (Figure 2.3). Cleveland had the largest relative increase in their use of stop and search between the year ending March 2020 and year ending March 2022, with stop and search at levels about 3 times higher now than they were then (from 2,063 in 2020 to 6,210 in 2022). This increase has been attributed to an increase in officer numbers, and increased training and confidence in their use of stop and search powers.

Figure 2.3: Number of searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation, relative to the year ending March 2020

Source: Stop and Search open data tables, Home Office

Notes:

-

Values shown for each PFA are relative to the number of stop and searches that took place in the year ending March 2020, which is represented by a value of 1.0.

-

Excludes Greater Manchester Police, as they were unable to provide complete data in the year ending March 2020.

Looking at longer term changes, the number of stop and searches conducted in the year ending March 2022 was 57% below the peak recorded in the year ending March 2011 (when there were 1,229,324). The rate of reduction between the year ending March 2011 and the year ending March 2018 in stop and searches accelerated following the then Home Secretary’s decision in 2014 to re-focus the use of such powers. This trend reversed the three years between the year ending March 2019 and year ending March 2021. This was in part thought to reflect willingness to make greater use of such powers as part of the operational response to a rise in knife crime, and encouragement to the police from the current Home Secretary to use stop and search powers.

Furthermore, the Government’s pledge to recruit an additional 20,000 officers by March 2023, of which 13,566 had been recruited by March 2022, may have an impact on these figures. However, in the year ending March 2022, the number of stop and searches decreased to a figure below the number of stop and searches in the years ending March 2020 and March 2021. The fall in stop and search has been driven by a decrease in the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) force area, which accounted for 56% of the total decrease in England and Wales in the year ending March 2022.

Figure 2.4: Number of stop and searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation, England and Wales, year ending March 2002 to March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_02, Home Office

Notes:

- Data prior to the year ending March 2010 do not include the British Transport Police (BTP). Data from the year ending March 2010 onwards includes the BTP but excludes GMP. Due to this, stop and search data before the year ending March 2010 are not directly comparable with more recent years. BTP usually account for between 1.0% and 2.0% of all and search across England and Wales per year.

Forty one of the 44 forces showed a decrease in stop and searches in the year ending March 2022 compared with the previous year, with most of the decreases in the range of 15% to 35%. Three forces showed small increases in the latest year with Northamptonshire Police showing the largest percentage rise (up 11% from 2,835 in the year ending March 2021 to 3,156 in the year ending March 2022).

In the year ending March 2021, several police forces reported that a reduction in demand for other calls to service, such as response to crime, during periods in which there were restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, gave increased capacity for proactive policing. In the year ending March 2022, with the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, several police forces reported that police activity was close to pre-lockdown normality, with lessened opportunity for proactive policing.

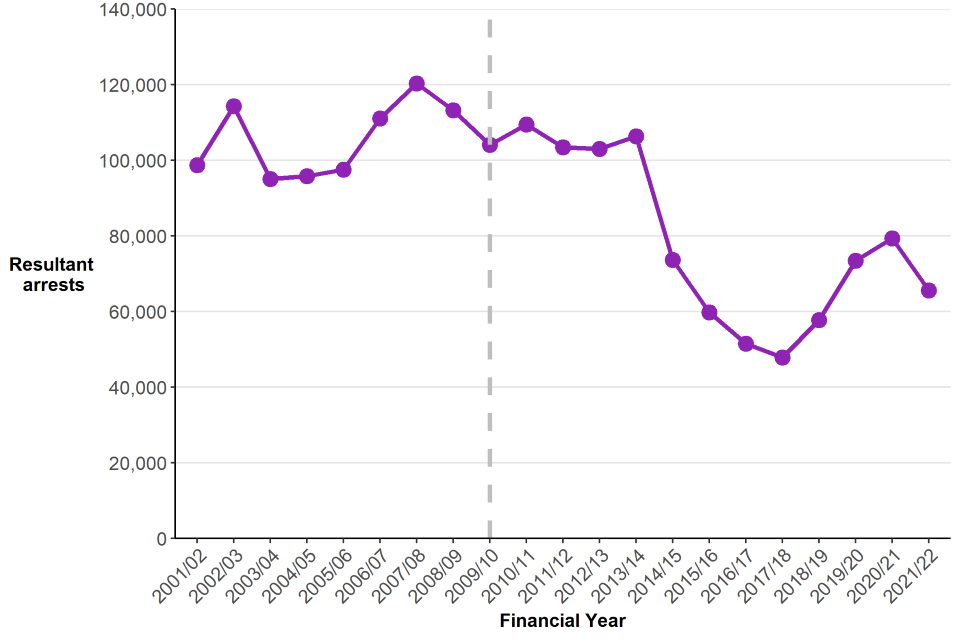

Arrests following stop and search

The number of resulting arrests following a stop and search decreased by 18% compared with the previous year. As Figure 2.5 shows, the number of arrests following a stop and search generally follows a similar pattern to the total number of stop and searches (Figure 2.4 above). However, arrest numbers remained fairly flat while there was a large fall in the number of searches between the years ending March 2011 and 2014, suggesting improved targeting of the power during this period.

Figure 2.5: Number of resultant arrests under section 1 PACE and associated legislation, England and Wales, year ending March 2002 to March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_02, Home Office

Notes:

- Data prior to the year ending March 2010 do not include the British Transport Police (BTP). Data from the year ending March 2010 onwards includes the BTP but excludes GMP. Due to this, stop and search data before the year ending March 2010 are not directly comparable with more recent years. BTP usually account for between 1.0% and 2.0% of all and search across England and Wales per year.

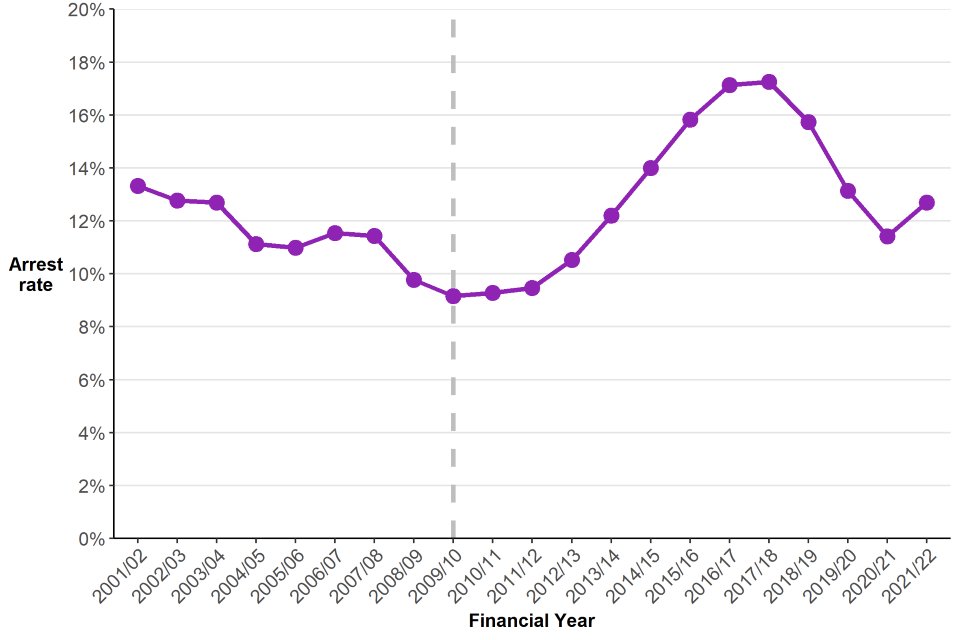

Arrest rate – the proportion of stop and searches resulting in an arrest

While the number of arrests following a section 1 PACE search fell by 18% in the latest year (down from 80,940 to 66,772), this was a smaller decrease than the fall in the total number of section 1 PACE searches over the same time period (down 25%). This led to a rise in the arrest rate, up from 11% in the previous year to 13% in the latest (Figure 2.6). The lower arrest rate in the year ending March 2021 may be partly due to the increased number of searches in that year as a result of proactive policing during lockdowns. The arrest rate in the latest year has returned to a level in line with policing prior to the pandemic.

Figure 2.6: Arrest rate under section 1 of PACE, England and Wales, year ending March 2002 to March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_02, Home Office

Notes:

1.Data prior to the year ending March 2010 do not include the British Transport Police (BTP). Data from the year ending March 2010 onwards includes the BTP but excludes GMP. Due to this, stop and search data before the year ending March 2010 are not directly comparable with more recent years. BTP usually account for between 1.0% and 2.0% of all and search across England and Wales per year.

Arrest is just one possible outcome following a stop and search. Data on other outcomes resulting from stop and search can be found in section 2.7 - Stop and search outcomes.

Reason for search

There are several reasons why the police may carry out a section 1 PACE stop and search, such as having reasonable grounds to suspect that an individual is carrying drugs or a weapon. Any subsequent arrests resulting from a PACE search may not be related to the initial reason for the search; for example, an officer may suspect that an individual is carrying drugs but arrest them if they are found to be carrying a weapon. As a result, while arrest rates give an overall picture of the number of searches leading to arrests, they do not give insight into arrest rates for specific offence categories. More information on how frequently arrests (and other outcomes) are linked to the initial reason for the search can be found in the link between search reason and outcome section. The Data Quality section also includes information on data collected on reason for arrest.

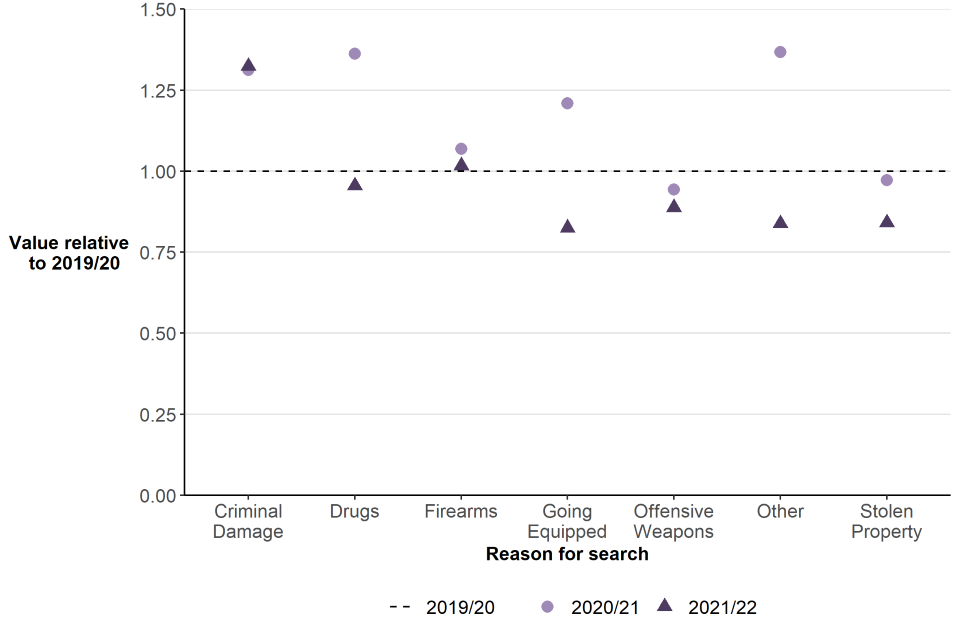

Year ending March 2022 compared with year ending March 2020

As stated in the section above, the police were operating in unprecedented circumstances during the year ending March 2021, therefore the following analysis compares the year ending March 2022 with the year ending March 2020, which was largely unaffected by the pandemic. GMP were unable to provide complete data in the year ending March 2020, and are therefore excluded from this section.

With the exception of criminal damage searches (up 32%) and firearm searches (up 2%), the number of searches for all other objects under section 1 PACE was lower in the year ending March 2022 than the year ending March 2020 (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7 PACE stop and searches by reason for search, England and Wales (excluding Greater Manchester Police), the year ending March 2020 compared with the year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search open data tables, Home Office

Notes:

-

Values shown for each PFA are relative to the number of stop and searches that took place in the year ending March 2020, which is represented by a value of 1.0.

-

Excludes Greater Manchester Police, as they were unable to provide complete data in the year ending March 2020.

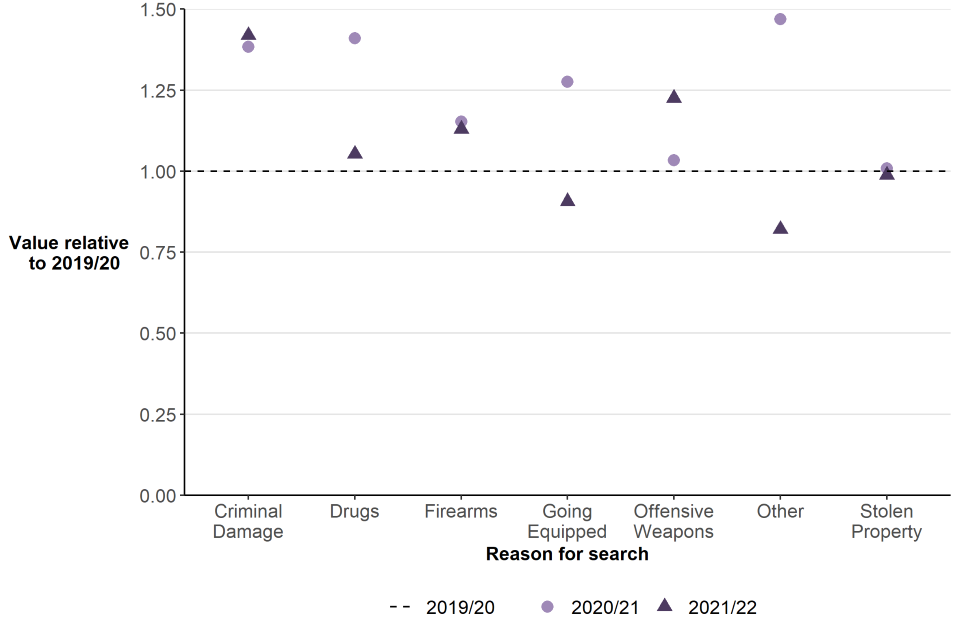

The change over this period has been driven by a reduction in stop and searches undertaken by the Metropolitan Police (down 22% from 268,384 to 210,347). Excluding Greater Manchester Police and Metropolitan Police, the number of stop and searches increased across additional search types between the year ending March 2020 and year ending March 2022, including offensive weapon searches (up 23%) and drug searches (up 5%) (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 PACE stop and searches by reason for search, England and Wales (excluding Metropolitan Police and Greater Manchester Police), the year ending March 2020 compared with the year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search open data tables, Home Office

Notes:

-

Values shown for each PFA are relative to the number of stop and searches that took place in the year ending March 2020, which is represented by a value of 1.0.

-

Excludes Greater Manchester Police, as they were unable to provide complete data in the year ending March 2020.

As in previous years, the most common reason for carrying out a PACE stop and search was on suspicion of drug possession. These accounted for 65% of all stop and searches in the latest year, a lower proportion than the previous one (69%) (Table 2.1). The proportion and volume of drugs searches steadily increased between the year ending March 2018 and year ending March 2021. That peak in the year ending March 2021 may have been impacted by proactive searches for drugs during lockdowns. In the latest year, the proportion of searches for drugs has fallen to a level closer to that from before the pandemic.

The proportion of searches on people suspected to be in possession of offensive weapons, articles to commit criminal damage or stolen property all increased in the latest year.

Table 2.1: Proportion of PACE stop and searches, England and Wales, years ending March 2020, March 2021 and year ending March 2022

| Reason for search | Proportion in year ending March 2020 | Proportion in year ending March 2021 | Proportion in year ending March 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | 63 | 69 | 65 |

| Offensive weapons | 16 | 12 | 16 |

| Stolen property | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| Going equipped | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Criminal damage | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Firearms | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Source: Stop and Search table SS_03, Home Office

Notes:

-

The ‘other’ search category includes searches under section 43 of the Terrorism Act 200 and for reasons such as fireworks.

-

Due to rounding, percentages may not sum to 100.

Apart from searches for articles to commit criminal damage, which rose slightly by 1%, the number of searches conducted in the latest year decreased across all other search reasons (Figure 2.9). The largest volume decrease was in the number of searches for drugs, which decreased by 30% from 484,917 in the year ending March 2021 to 339,662 in the year ending March 2022. The decrease in stop and searches for drugs matches trends observed in police recorded crime data, where there was an decrease in drug offences, which reflects that these offences are often discovered through stop and search.

Figure 2.9: PACE stop and searches by reason for search, England and Wales, the year ending March 2021 compared with the year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_03, Home Office

Notes:

- The ‘other’ search category includes searches for reasons such as fireworks.

Trends in the levels of stop and search across England and Wales overall are largely driven by the policing activity of the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS). Excluding MPS from year-on-year comparisons, there was a 19% increase in the number of searches for offensive weapons in the year ending March 2022 compared with the previous year. 32 police forces had a higher number of searches for offensive weapons in the year ending March 2022 compared with the previous year, with many of those reporting that they have renewed their focus on driving down serious violence.

2.4 Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act

Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (CJPOA) 1994 enables officers to conduct ‘no suspicion’ stop and searches for dangerous instruments or offensive weapons for a limited time within a specified area, in anticipation of violence occurring in that area. This will often follow a major incident or from intelligence gathered by the police. Further details can be found in the User Guide.

From April 2019, under a pilot scheme agreed by the then Home Secretary, some changes were made to the conditions under which a section 60 search could be carried out. The changes aimed to make it easier for the police to use such powers when they judged it necessary to do so and included:

- reducing the rank of authorising officer from senior officer to inspector

- relaxing the grounds from a reasonable belief that serious violence will take place to a belief that it may take place

A phased approach was taken with 7 forces joining the pilot from 1st April 2019 whilst the remaining 37 forces joined from August 2019. Three further changes were made at that time:

- increasing the length of time the initial Section 60 order can be in place from 15 to 24 hours

- reducing the rank of officer who can extend the order for up to a further 24 hours from senior officer to superintendent

- removing the requirement for forces to communicate to local communities in advance, where practicable, where a Section 60 order is in place

In July 2021, as part of the Beating Crime Plan, the then Home Secretary announced a permanent relaxation of all five voluntary conditions outlined above.

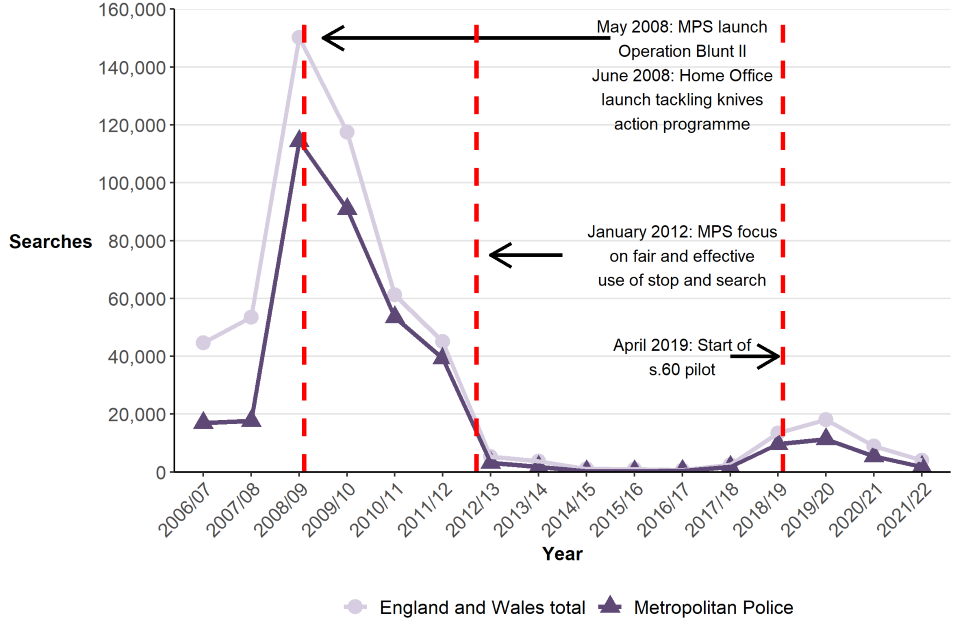

In the year ending March 2022, police in England and Wales carried out 4,341 stop and searches under section 60 CJPOA, a decrease of 52% compared with the previous year (when 9,002 such searches were undertaken). This is the second consecutive decrease in the number of searches under section 60, following three years of increases between the year ending March 2018 and the year ending March 2020 (Figure 2.10).

The decrease in the latest year was driven by a reduction in stop and searches conducted by the Metropolitan Police Service, which decreased by 67% from 5,395 to 1,760. Other forces, including Merseyside and Thames Valley also saw large decreases in the number of searches under section 60 CJPOA in the latest year. However, some forces conducted more section 60 searches in the latest year, including West Midlands, West Yorkshire and Greater Manchester Police.

Figure 2.10: Stop and searches under section 60 CJPOA, England and Wales, year ending March 2007 to March 2022

Source: Stop and Search open data tables, Home Office

Notes:

- Data from the year ending March 2010 onwards includes the British Transport Police (BTP) but excludes Greater Manchester Police. Prior to this data are not directly comparable with more recent years.

The number of forces making at least one stop and search under section 60 powers decreased from 20 to 18 of the 44 forces in England and Wales (including BTP) in the latest year. As in previous years, most section 60 stops took place in London with the MPS accounting for more than two-fifths (41%) of all section 60 searches in England and Wales. This was followed by Kent Police and West Midlands Police, each of which accounted for 12% of the total number of section 60 searches.

The proportion of section 60 searches that resulted in an arrest in the latest year was 3.4%, down slightly from the previous year (3.7%).

Between the year ending March 2003 and the year ending March 2016, the arrest rate fluctuated between 2% and 6% then, in the year ending March 2017 the arrest rate peaked at 12% (72 of 622 searches resulted in arrest). However, since then, the arrest rate has steadily declined to 8% in the year ending March 2018, 5% in the year ending March 2019 and 4% in the years ending March 2020 and March 2021. As in previous years, the arrest rate for section 60 searches (3.4%) was much lower than those under section 1 of PACE (13%).

2.5 Section 47A (previously section 44) of the Terrorism Act 2000

Section 47A (as amended by the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012) of the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) allows the police to exercise stop and search powers when there is reasonable suspicion an act of terrorism will take place, and only when such powers are considered necessary to prevent such an act taking place. This must be authorised by a senior officer, at least at the rank of Assistant Chief Constable, and the area and duration of the authorisation must be no greater than is necessary to prevent such an act. Section 47A of TACT stop and search powers replaced similar powers under section 44 of TACT on 18 March 2011. Further information on these searches can be found in the User Guide.

In the last four years, stop and search powers under section 47A of TACT were not used. In year ending March 2018, there were 149 stop and searches under section 47A of TACT, details of which can be found in the bulletin from that year.

2.6 Stop and search by Police Force Area

The MPS continued to account for a large proportion of all stop and searches[footnote 2] conducted in England and Wales (40% in the year ending March 2022), though this is down slightly on the previous year, in which the MPS accounted for 44% of the total number of searches.

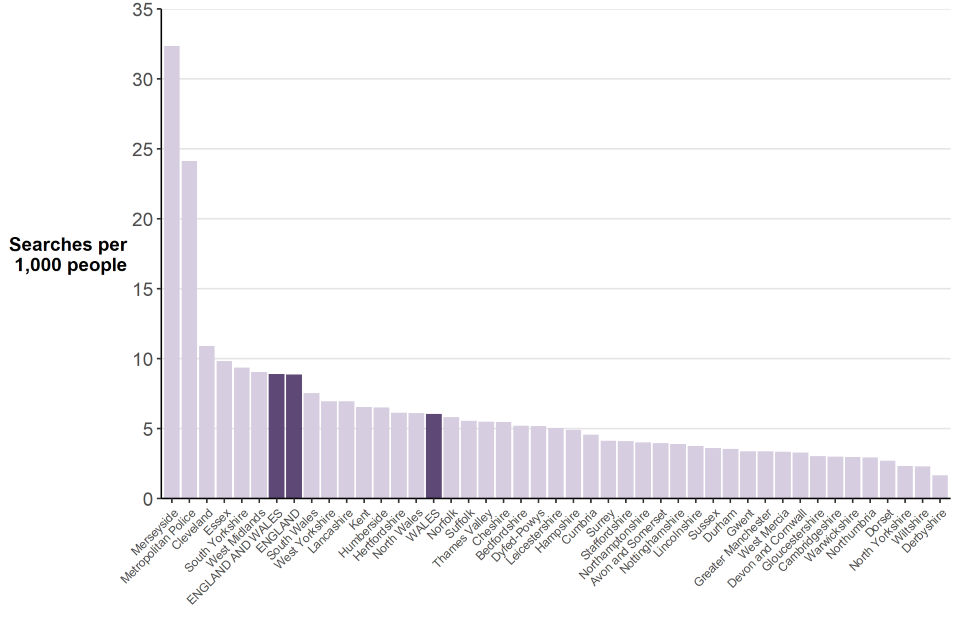

When examining the use of stop and search amongst different police forces, a traditional approach is to express rates of stop and search per head of resident population, using population figures produced by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). This allows for more meaningful comparisons between areas than solely using the volume of searches in that area. However, calculating the rate based on the resident population has several limitations, such as not accounting for the volume of commuters and tourists in areas with substantial influx of non-residents. Additionally, looking at the rate across the Police Force Area (PFA) as a whole masks variation within the area (see section 2.11 - hotspot analysis). Lastly, looking at the overall population within a PFA ignores the fact that stop and search is particularly concentrated on young men (see section 2.9 – Age of sex of persons stopped and searched).

PFA analysis to compare overall rates per 1,000 population and disparity rates for each ethnic group compared with the white group can be found in section 2.8 (Ethnicity of persons searched).

In England and Wales there were 9 stop and searches per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2022. Merseyside PFA had the highest rate at 32 per 1,000 population[footnote 3], followed by Metropolitan Police Service PFA, which had a rate of 24 per 1,000 population (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11: Stop and search per 1,000 population, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_21, Home Office

Notes:

- Includes stop and searches under section 1 of PACE and associated legislation, and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

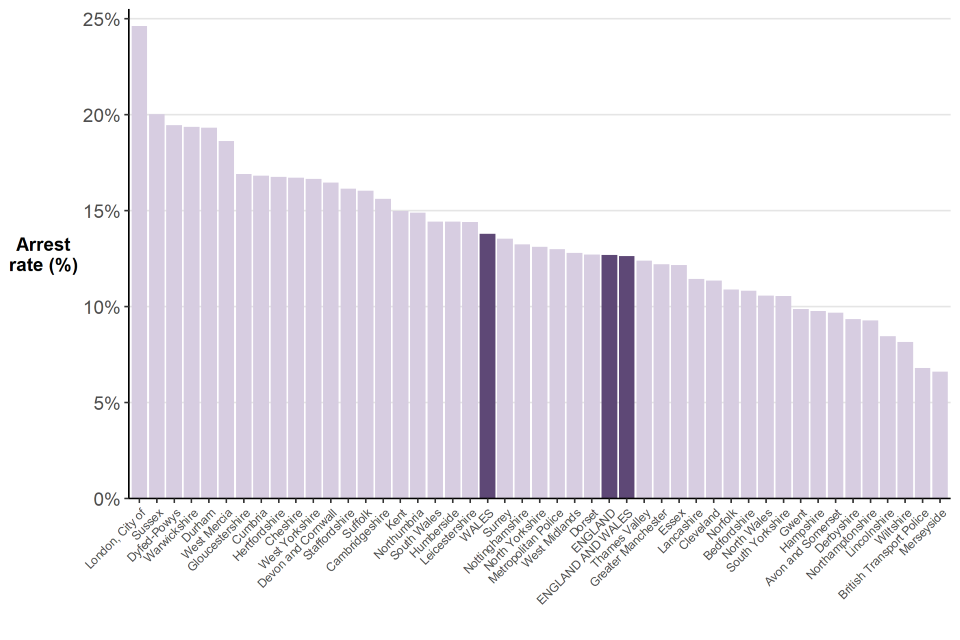

Searches conducted under section 1 PACE and section 60 CJPOA combined resulted in an 13% arrest rate in England and Wales for the latest year (Figure 2.12). By comparison, stop and searches in the City of London resulted in the highest arrest rate (25%) followed by Sussex (20%). Merseyside had the lowest arrest rate, with 7% of searches leading to an arrest.

Figure 2.12: Arrest rate following a stop and search, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_21, Home Office

Notes:

- Includes stop and searches under section 1 of PACE and associated legislation, and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

While an arrest is one possible outcome of a stop and search, there are a range of other outcomes that could indicate a successful search, including the issuing of police cautions, cannabis or khat warnings, community resolutions and summonses. These are included in the stop and search outcomes section 2.7.

2.7 Stop and search outcomes

Historically, forces have provided data on the number of stop and searches conducted, and the number of resultant arrests. Arrests represent only one of several possible outcomes available to the police when conducting a stop and search. Since the year ending March 2017, police forces have reported on a wider range of outcomes including:

- arrests

- cautions

- summons

- penalty notices for disorder

- cannabis or khat warnings

- community resolutions

- no further action

Since the year ending March 2021, the Home Office have expanded the list of viable outcomes to also include:

- voluntary attendance

- verbal warning or words of advice

- seizure of property

- guardian intervention

- other action

In years prior to the year ending March 2021, the new options would have been classed as ‘no further action’. Therefore, comparisons with previous years on the proportion of searches that resulted in ‘no further action’ should be interpreted with caution. A full breakdown of stop and search outcomes is available in the data tables accompanying this publication.

One outcome per stop and search

For each stop and search, only the first outcome is recorded. For example, where a criminal sanction follows an arrest, only the arrest will be shown in these statistics. Therefore, outcomes that follow an arrest (such as cautions) will be an under-count of the actual number of such outcomes. The data should therefore not be used to infer, for example, the total number of cautions that result from stop and searches.

Outcome linked to reason for stop and search

Forces are also required to report on whether the outcome was linked to the initial reason for conducting the search. For example, police may stop someone on suspicion of carrying drugs. If cannabis is found during the search and the person is given a cannabis warning, then the outcome is linked to the reason for the search. However, if a weapon is found instead of cannabis and the person is arrested, the outcome is not linked to the initial reason for the search.

Tracking whether or not the outcome is linked to the reason for the search aims to increase transparency by allowing for a distinction between outcomes where the officer found what they were searching for, those where the item found was not what the officer was initially searching for, or where nothing was found.

Limitations of outcomes data

The findings in this section should be considered with caution. They give a reasonable indication of the picture at the national level, but users should be wary of making force level comparisons.

While the outcome of each stop and search is relatively straightforward to record, the link between the reason for the search and the search outcome is more complex. In many forces, officers themselves assess whether a link is involved, and so there is an element of subjectivity involved. It is likely that different officers may classify whether there is a link or not in different ways.

Furthermore, a number of forces have adopted mobile devices to allow officers to directly record stop and searches at the scene, as well as the outcome following a stop and search. Some forces have reported inconsistencies in the way officers use these devices, leading to difficulties when deciding whether the outcome of the search was linked to the reason for the search (for example, more than one outcome was recorded, or the officer had marked the outcome as “linked” to the reason for the search where it did not appear that the outcome was linked).

Given the known issues around the quality of stop and search link and outcome data, these statistics are designated as Official Statistics, and not National Statistics.

Principal outcome following a stop and search

These data include the initial outcome given following the search only. It should be noted that ‘no further action’ can include a wide range of scenarios. It is therefore possible that, in some cases, an outcome of ‘no further action’ could be given where the officer finds what they were looking for (outcome linked) but decides not to deal with it by means of arrest, cautions, community resolutions or another outcome. For example, a person could have a lawful reason for carrying an item which the officer might have been perceived as a weapon. Additionally, if a child has been used to carry a prohibited article for an adult, the carrier may be treated as a witness rather than have action taken against them. Lastly, in circumstance where a person may be found with weapons or drugs with the intent to harm themselves, the subjects may be treated in a supportive way rather than arrested.

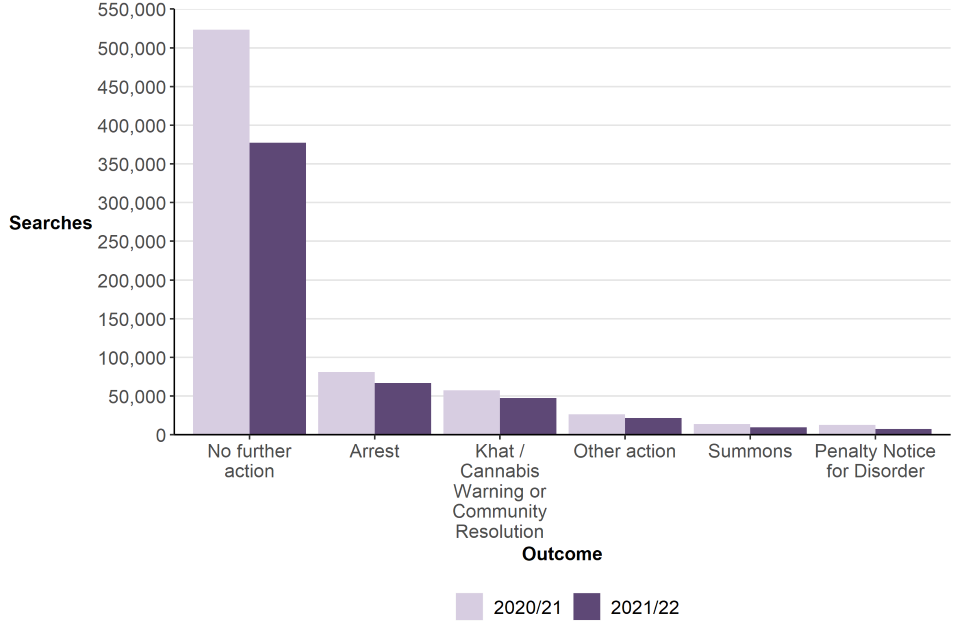

These data include searches under both section 1 Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. In 71% of stop and searches the outcome was recorded as needing ‘No further action’. In a further 13% the initial outcome was an arrest and an alternative outcome was given in the remaining 16% of cases. These proportions are all similar to the previous year (Table 2.2).

Figure 2.13: Principal outcome following stop and search, England and Wales, year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search outcomes table SSO_01, Home Office

Notes:

- Includes stop and searches under section 1 of PACE and associated legislation, and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

- Includes vehicle only searches.

- Includes British Transport Police.

- Other action includes cautions, voluntary attendance, verbal warnings or words of advice, seizure of property, guardian intervention or other action.

- Comparison against 2019/20 is not included due to changes in the outcome framework, which started in 2020/21.

Table 2.2: Proportion of outcomes following a stop and search, in the year ending March 2021 and the year ending March 2022

| Outcome | Proportion in year ending March 2021 | Proportion in year ending March 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Arrest | 11.4 | 12.6 |

| Community Resolution | 6.2 | 7.7 |

| Summons | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Verbal Warning / Words of Advice | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Penalty Notice for Disorder | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| Khat / Cannabis Warning | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Other Action | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Seizure of Property | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Voluntary Attendance | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Caution | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Guardian Intervention | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| No further action | 73.2 | 71.2 |

Source: Stop and Search outcomes table SSO_01, Home Office

Notes:

- Includes British Transport Police.

If the outcomes introduced in the year ending March 2021 are considered to be ‘No further action’ (as they would have been prior to that year), then 75% of searches in the year ending March 2022 resulted in ‘No further action’. This is down slightly from the year ending March 2021, in which 77% of searches resulted in ‘No further action’, by that same measure.

Link between outcome and reason for a stop and search

In the latest year, 23% of stop and searches resulted in an outcome that was linked to the reason for the search, a slightly higher figure than last year (20%). However, this varied by the reason for search. For example, 28% of drugs searches resulted in a linked outcome, whereas only 3% of searches under Section 60 of Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 resulted in a linked outcome. This lower rate for Section 60 searches reflects the fact that they are undertaken to try and resolve violent situations swiftly in a specific area, without reasonable grounds to suspect the people being searched.

Table 2.3: Proportion of stop and search where the outcome of the stop was linked to the reason for the stop and search, by reason for stop, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

| Reason for search | Outcome linked to reason for search | Outcome not linked | Nothing found |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | 28 | 3 | 70 |

| Stolen property | 21 | 6 | 73 |

| Firearms | 15 | 7 | 78 |

| Offensive weapons | 11 | 6 | 82 |

| Criminal damage | 11 | 6 | 83 |

| Going equipped | 10 | 8 | 82 |

| S.43 (Terrorism) | 6 | 5 | 90 |

| Other | 21 | 6 | 72 |

| Total Section 1 PACE | 23 | 4 | 73 |

| S.60 (Violence) | 3 | 5 | 92 |

| Total | 23 | 4 | 73 |

Source: Stop and Search open data tables, Home Office

Notes:

-

Proportions are calculated excluding cases where an object was found however the link between the reason for search and outcome is unknown, or where it’s unknown whether an object was found.

-

The ‘other’ search category includes searches under Section 1 PACE that do not fall into other categories.

-

Due to rounding, percentages may not sum to 100.

Weapons found from stop and search

The Home Office stop and search data collection was expanded in the year ending March 2021 to allow for provision of more detailed information on whether an offensive weapon or firearm was found in a stop and search encounter. Previously, data were only collected on whether an offensive weapon was found from a search conducted under s.60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act.

Different police forces may have different ways of recording the property found during a stop and search, and it may not always be clear whether an offensive weapon or firearm was found. For example, a record may state that a search was carried out for an offensive weapon, and that the outcome was related to the reason for the search, suggesting that an offensive weapon was found. However, the specific ‘property found’ part of the record may not mention an offensive weapon. Alternatively, a record of search for an offensive weapon may include information that states a stolen or prohibited article was not found as the link between the reason for search and outcome, but have items that could be considered to be offensive weapons (such as surgical or construction equipment) within the details of property found.

Additionally, other Home Office statistical collections have highlighted the challenges of determining whether a knife or sharp incident was involved in a crime, particularly when reliant on officers to tag records with that information. Additionally, the data collected does not indicate whether multiple weapons were found in a single search. Therefore, the figures presented here are estimates and should be used with caution.

Approximately 14,900 (3%) of searches in the year ending March 2022 resulted in an offensive weapon or firearm being found. Approximately 3,500 of those weapons or firearms were found when the initial search reason was for drugs.

Outcomes by Police Force Area

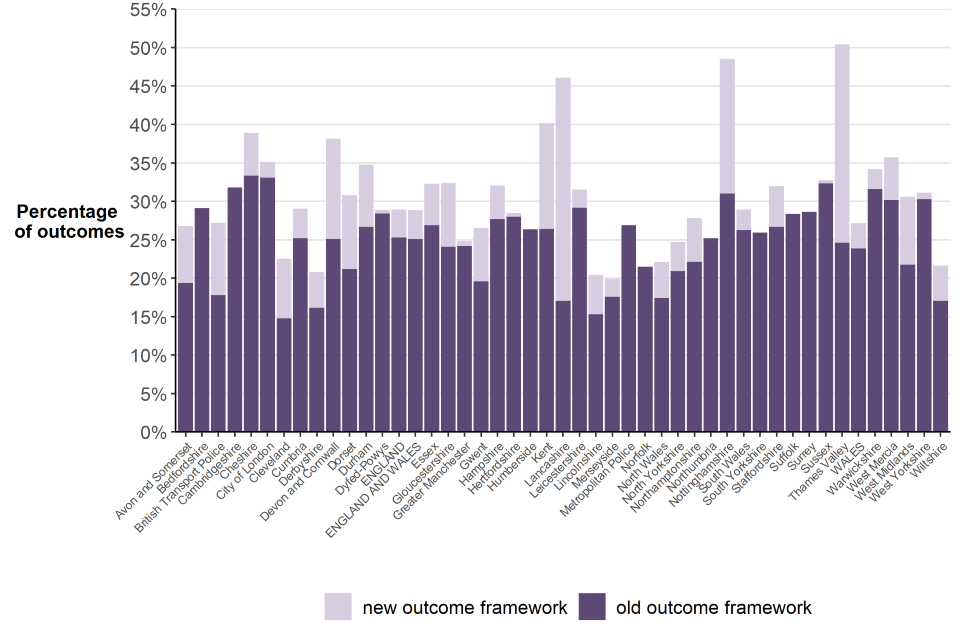

Figure 2.14 shows the outcome rate for each Police Force Area in the year ending March 2022. The figures are broken down by searches that resulted in action being taken as part of the old outcome framework (which consisted of arrest, summons, caution, khat or cannabis warning, penalty notice for disorder or a community resolution), or as part of the new outcome framework (voluntary attendance, verbal warning or words of advice, seizure of property, guardian intervention or other action). Due to inconsistency between forces in how the new outcome framework Is being applied, the figures should be interpreted with caution. Based solely on the old outcome framework, Cheshire Constabulary had the highest percentage of searches where action was taken (33%). Overall, Thames Valley Police had the highest number of searches where action was taken (50%), however, a large proportion of those were verbal warnings or words of advice (21%)

Figure 2.14 Outcome rate following a stop and search, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search outcomes table SSO_10, Home Office

Outcomes by ethnicity of person searched

Table 2.4 shows the outcome rates for each ethnic group. This uses the method whereby if the self-defined ethnicity of the person searched was ‘not stated’, then the officer-defined ethnicity is used instead.

People who self-defined their ethnicity as black, mixed or other (or perceived by the officer to belong to one of those ethnicities, if not stated) had an arrest rate of 14%. White people had an arrest rate of 12.3%, and people who self-defined or were perceived to be of Asian ethnicity had the lowest arrest rate (11.1%).

Despite having equal arrest rates, black people had the highest rate of ‘No further action’ outcomes, whereas people from a mixed or other background had the lowest rate of no further action outcomes. This is largely due to the difference in community resolution or cannabis warning outcomes between these two groups (7.8% for black, 10.6% for mixed or other).

Table 2.4 Proportion of outcomes following a stop and search, by ethnic group

| Outcome | White | Black | Asian | Mixed or Other | Not known | All person searches |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrest | 12.3 | 14.0 | 11.1 | 14.0 | 7.8 | 12.6 |

| Community Resolution or Cannabis Warning | 9.1 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 6.7 | 9.0 |

| Penalty Notice for Disorder | 0.9 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Summons | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| Other | 4.8 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| No Further Action | 70.9 | 72.8 | 71.8 | 68.8 | 78.0 | 71.3 |

Source: Stop and Search outcomes table SSO_11, Home Office

Notes:

-

Due to rounding, percentages may not sum to 100.

-

Excludes vehicle only searches.

-

Cannabis warnings and community resolutions are grouped as many police forces no longer issue cannabis warnings.

-

‘Other’ outcomes include caution, voluntary attendance, verbal warning, seizure of property, guardian intervention or other action.

2.8 Ethnicity of persons searched

When a stop and search is undertaken, the person being searched is asked by the police which ethnic group they consider themselves to belong to. This is a measure of “self-defined” ethnicity rather than “officer observed” and is the preferred measure of ethnicity. For the purpose of analysis, the 18 ethnicity categories as defined by the ONS 2011 Census, were grouped into the following categories:

- White

- Black (or black British)

- Asian (or Asian British)[footnote 4]

- Mixed

- Other Ethnic Group

- Not Stated

Additionally, officer-observed ethnicity may also be recorded as one of the following:

- White

- Black

- Asian

- Other

Since the year ending March 2021, the Home Office have collected stop and search data on both the “officer observed” ethnicity and the self-defined ethnicity of the person searched, for individual records. This means that if the self-defined ethnicity of the person searched was not stated, officer-observed ethnicity can be used as a proxy, for analytical purposes.

This section begins by examining the ethnicity of people stopped and searched using the traditional method, based solely on self-defined ethnicity. The latter section uses the newer approach, in which when the self-defined ethnicity of the person searched was not stated, officer-observed ethnicity is used instead. The approach is an attempt to reduce uncertainty in disparity rates based solely on self-defined ethnicity, caused by the growing proportion of records in which this information is not stated (20% in the year ending March 2022). This latter approach is only possible for data in the latest two reporting years.

Self-defined ethnicity of persons searched

The MPS consistently account for a large proportion of all stop and searches in England and Wales (40% in the year ending March 2022) and also has a larger proportion ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities) within its resident population (40%) than the rest of England and Wales (10% - excluding MPS)[footnote 5]. Table 2.5 presents the data for the MPS area separately, as well as distinct England and Wales totals, with one including and the other excluding the MPS area. Table 2.5 shows that for both section 1 PACE searches and section 60 searches, stops of individuals who define themselves as black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups accounted for a larger proportion of all stops in the MPS area when compared with forces in the rest of England and Wales.

Table 2.5: Proportion of stop and searches by self-defined ethnic group, England and Wales and the MPS area, year ending March 2022

| Legislation | Police Force Area(s) | White | Black | Asian | Other | Mixed | Not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | E&W excl. MPS | 68 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 15 |

| Section 1 | MPS | 32 | 23 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 27 |

| Section 1 | England & Wales | 53 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 20 |

| Section 60 | E&W excl. MPS | 46 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 5 | 19 |

| Section 60 | MPS | 18 | 28 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 38 |

| Section 60 | England & Wales | 35 | 18 | 14 | 2 | 4 | 26 |

| All searches | E&W excl. MPS | 68 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 15 |

| All searches | MPS | 32 | 23 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 27 |

| All searches | England & Wales | 53 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 20 |

| Population | E&W excl. MPS | 90 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Population | MPS | 60 | 13 | 18 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Population | England & Wales | 86 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Source: Stop and Search table SS_23, Home Office

Notes:

-

Excludes vehicle only searches.

-

Includes searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

-

Due to rounding, percentages may not sum to 100.

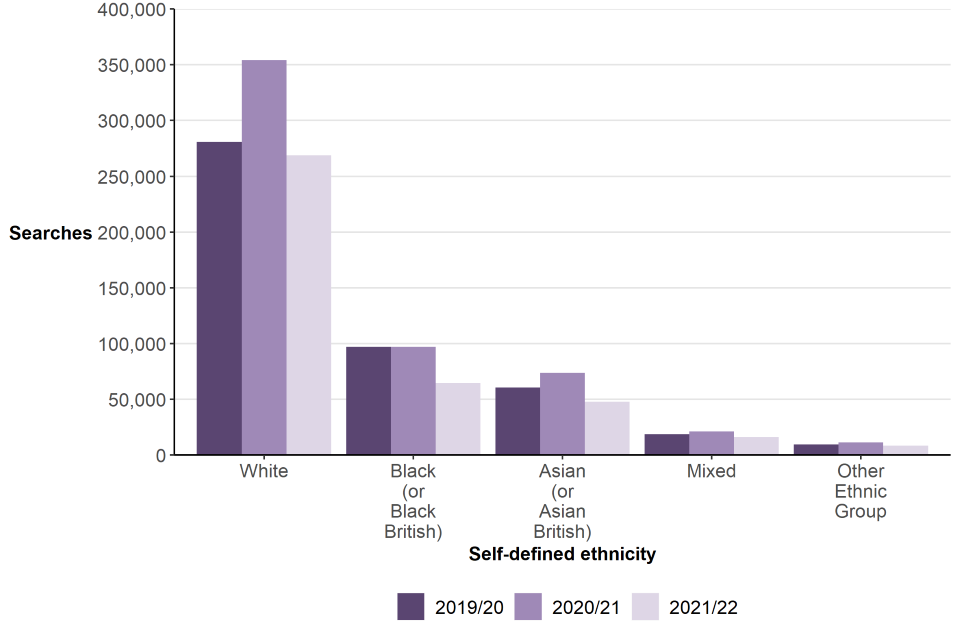

The number of searches of people who self-defined as white decreased by 84,986 (24%), from 359,273 to 274,287 in the latest year (a decrease of 4% since the year ending March 2020). The next-highest volume decrease was for those from the black (or black British) group, which decreased by 32,488 (33%) from 97,990 to 65,502. There was a similar decrease in searches of people from the Asian (or Asian British) group, which decreased by 26,047 (35%) from 74,976 to 48,929. There were slightly smaller decreases in the number of searches of people from mixed ethnic backgrounds (which decreased by 5,205 (24%) from 21,412 to 16,207) and people from other ethnic groups (which decreased by 2,935 (26%) from 11,473 to 8,538. The proportionate decreases were smaller for individuals from a white ethnic group (down 24%) than from all other ethnic groups combined (down 32%).

Figure 2.15: Change in stop and searches by ethnicity, England and Wales, the year ending March 2022 compared with the year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2020

Source: Stop and Search open data tables, Home Office

Notes:

-

Includes searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation, section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, and section 47A of the Terrorism Act 2000.

-

Includes British Transport Police. Excludes Greater Manchester Police.

The above aggregate numbers do not take into account the variation in the size and geographical distribution of different ethnic groups. The following analysis considers the self-defined ethnicity of those searched relative to the population as a whole, by calculating search rates for each ethnic group. Population data is based on the 2011 Census, and so should be considered with caution given the length of time since the figures were collated and the likely changes in the size and distribution of the population in the last decade. The figures in this section will be revised once estimates of ethnic groups from the 2021 Census are available, which are expected to be published in late 2022.

Caution should be taken when interpreting search rates at the national level because, as stated above, force areas vary in their ethnic composition; an average national figure presumes that all stop and searches and ethnic groups are spread evenly across forces, whereas these differ considerably between forces. Furthermore, even within a PFA there can be significant variation in terms of the distribution of different ethnic groups, which may be masked by the force level averages. One notable example of this is the Metropolitan Police PFA[footnote 6] which is comprised of several boroughs where ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities) comprise the majority of the resident population, and others where they form a minority of the resident population. For this reason, more insightful analysis is possible at smaller geographical levels than PFA.

It is also important to be mindful of the fact that the population data are based on residential estimates and do not account for the transient population – people who move into and out of an area, but do not live there.

Furthermore, when calculating rates, individuals who have not provided their ethnicity have been excluded. In the latest year, the level of missing ethnicity data (self-defined) was 20%, a higher proportion compared with the previous year (19%). This proportion has steadily increased since the year ending March 2014, in which self-defined ethnicity was not stated for only 5% of searches. This adds further uncertainty to the trends discussed below.

Data are presented in terms of the rate that ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities) were searched compared with white people.

In the year ending March 2022, based on the traditional measure of using self-defined ethnicity and the ONS 2011 Census population estimates to calculate rates, people identifying as black or black British were searched at a rate 6.2 times higher than those from a white ethnic group across England and Wales. Between the year ending March 2011 and the year ending March 2015 the differential generally reduced (going from 7 to 4 times higher respectively). However, it started to rise from the year ending March 2016, reaching a peak in the year ending March 2018 and year ending March 2019, with the rate around 9.5 times higher for those identifying as black or black British compared with those who identify as white), before falling to 8.8 in the year ending March 2020 and then to 7.0 in the year ending March 2021.

In the latest year, people identifying as Asian or Asian British were searched at a rate 2.1 higher than those from a white ethnic group. Similarly to people of a black or black British background, this differential has widened since the year ending March 2015, when the rate was 1.3 times higher for Asian or Asian British people compared with white people. A similar pattern has also occurred for those from a mixed ethnic background or from other ethnic groups. In the latest year, people identifying as mixed were searched at a rate 2.3 higher than white people, and people from other ethnic groups 2.7 higher (Table 2.6).

Table 2.6: Comparison of the rate at which people were searched relative to individuals who self-define their ethnicity as white

| Year | Black (or Black British) | Asian (or Asian British) | Other Ethnic Group | Mixed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010/11 | 6.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| 2011/12 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| 2012/13 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| 2013/14 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| 2014/15 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| 2015/16 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| 2016/17 | 8.4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| 2017/18 | 9.5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| 2018/19 | 9.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| 2019/20 | 8.8 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| 2020/21 | 7.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| 2021/22 | 6.2 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

Source: Stop and Search table SS_18, Home Office

Notes:

-

Includes searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

-

Population breakdowns used to calculate the disparity figures are based on the 2011 census. Given the length of time since the last Census, figures in this table should be considered estimates only.

-

Greater Manchester Police are excluded as they were unable to provide complete data in 2019/20.

Officer-observed ethnicity of people searched

As shown in table 2.5, in the year ending March 2021, self-defined ethnicity was ‘not stated’ for approximately 1 in every 5 searches of people. This increases the uncertainty in the figures presented above. Table 2.7 presents the data in a different way; where the self-defined ethnicity of the person searched is not stated, officer-observed ethnicity is used instead. This reduces the proportion of stops with unknown ethnicity from 20% to 1%.

Table 2.7: Proportion of stop and searches by ethnic group, England and Wales and the MPS area, year ending March 2022

| Legislation | Police Force Area(s) | White | Black | Asian | Mixed or Other | Not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | E&W excl. MPS | 76 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| Section 1 | MPS | 40 | 35 | 17 | 8 | 1 |

| Section 1 | England & Wales | 61 | 19 | 12 | 6 | 1 |

| Section 60 | E&W excl. MPS | 55 | 16 | 18 | 9 | 1 |

| Section 60 | MPS | 25 | 47 | 19 | 9 | 1 |

| Section 60 | England & Wales | 43 | 28 | 19 | 9 | 1 |

| All searches | E&W excl. MPS | 76 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| All searches | MPS | 40 | 35 | 17 | 8 | 1 |

| All searches | England & Wales | 61 | 19 | 13 | 6 | 1 |

| Population | E&W excl. MPS | 90 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Population | MPS | 60 | 13 | 18 | 8 | 0 |

| Population | England & Wales | 86 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

Source: Stop and Search table SS_24, Home Office

Notes:

-

Excludes vehicle only searches.

-

Includes searches under section 1 PACE and associated legislation and section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

-

Table uses officer-observed ethnicity in place of self-defined ethnicity for records where self-defined ethnicity is ‘not stated’.

-

Due to rounding, percentages may not sum to 100.

Looking at the data in this way increases the disparity rates for people from ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities), especially for black people. This suggests that self-defined ethnicity is more likely to be ‘not stated’ or missing when the person searched was from one of those ethnic groups. Using officer-observed ethnicity in place of self-defined ethnicity (when the latter is ‘not stated’) the disparity for ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities) in the year ending March 2022 was 3.8 (compared with 3.1 using the measure solely using self-defined ethnicity data). There was a relatively larger increase when looking at the differential for black people, who had a disparity of 8.0 using this methodology (compared with 6.2 using the measure solely using self-defined ethnicity data), and a relatively smaller increase in the differential for Asian people, who had a disparity of 2.3 using this methodology (compared with 2.1 using the measure solely using self-defined ethnicity data).

Stop and search rates by Police Force Area and ethnicity

The following analysis compares the overall rate of stop and search per 1,000 population for each ethnic group based on self-defined ethnicity (using the 2011 5+1 Census categories) against the relative rate at which people from each ethnicity are stopped and searched in comparison to white individuals, at Police Force Area level. A relative rate of 1 indicates that individuals from the minority ethnic group (excluding white minorities) are stopped at the same overall rate as white individuals. If the relative rate is less than 1, it indicates that individuals from the minority ethnic group are stopped at an overall rate less than white individuals, and if greater than 1, they are stopped at a greater overall rate. For example, a relative rate of 2 would mean that a group is stopped twice as much as the white group.

As the 2011 Census resident population estimates are over a decade old and the population is known to have changed considerably since 2011, both in size and its ethnic composition, this section should be treated as indicative only. This analysis will be updated in a future release to use the 2021 Census estimates once they are available.

When making comparisons between forces on disparity rates, the following should be borne in mind:

-

both the relatively low number of stop and searches and the relatively small size of the resident population of ethnic minorities in some force areas can produce large differences in rates per 1,000 population which are the result of a very small difference in the absolute numbers.

-

police resourcing and priorities – the level of stop and search in a police force area will be influenced by operational priorities and decisions.

-

transient populations – the Race Disparity Unit highlighted the impact of population changes on stop and search rates, the stop and search rates are based on resident population estimates at a specific time and do not take into account individuals temporarily visiting an area, for example tourists and students.

-

variations within Police Force Areas – as section 2.11 shows, some force areas with have many smaller areas (LSOAs) that have little to no stop and search activity, with a small proportion of areas accounting for the majority of stop and search.

Black ethnic group

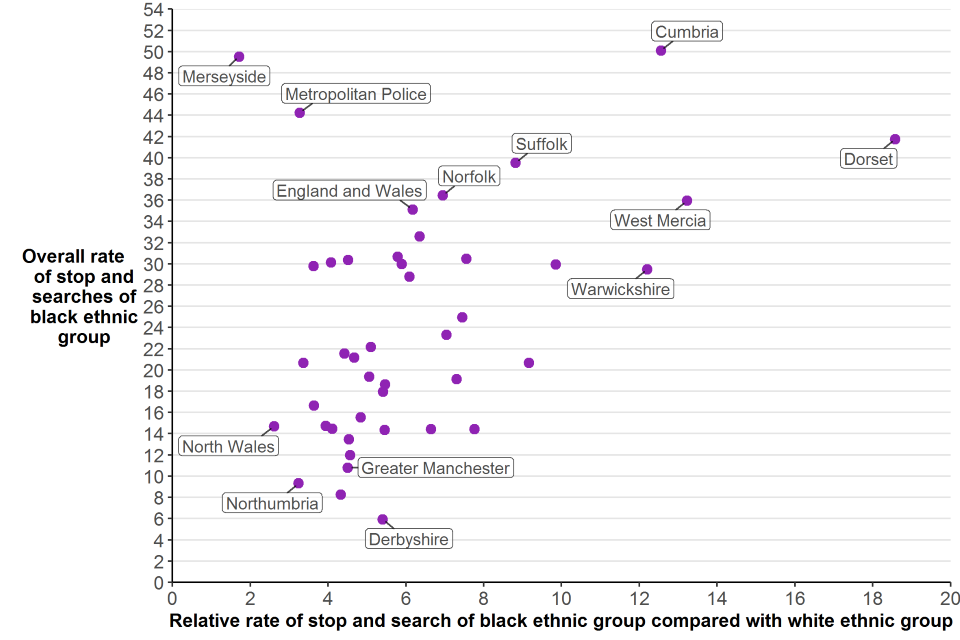

Figure 2.16: Overall stop and search rates and relative rates for black individuals, by Police Force Area, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_16, Home Office

Notes:

-

City of London and British Transport Police are not shown, but they have been included in the England and Wales total.

-

Rates of stop and search are calculated using Census 2011 Estimates. These are likely to be outdated so should be treated as indicative only.

In England and Wales there were 35 stop and searches of individuals from a black background per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2022. This is the highest overall rate compared with all other ethnic groups and 6.2 times higher compared with the white group, who were stopped and searched at an overall rate of 6 per 1,000 population. Cumbria and Merseyside had the highest overall rates at 50 stop and searches per 1,000 population, followed by Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) with an overall rate of 44 stop and searches per 1,000 population. Despite Cumbria having one of the highest overall rates of stop and search it is based on a very small number of searches (29 searches) compared to Merseyside and MPS (721 and 48,158 respectively). The lowest overall rate of stop and search of individuals from a black background was by Derbyshire, at an overall rate of 6 stop and searches per 1,000 population. Derbyshire also had a low number of stop and searches (60 searches).

Although Merseyside and the MPS showed two of the highest overall rates for individuals from a black background, they were among the forces with the lowest relative rates, along with North Wales and Northumbria (1.7, 3.3, 2.6, and 3.2 respectively). When considering the relative rates, it is important to note the variation between forces in the number of stop and searches on individuals from a black background. For example, North Wales and MPS had similar relative rates but carried out very different numbers of searches of people from a black ethnic background (22 and 48,158 searches respectively).

Dorset and West Mercia had the highest relative rates of all police forces, with individuals from a black background being stopped 18.6 and 13.2 times more than white individuals respectively. Although these forces have high relative rates, it should be noted that, as indicated by the Table A1, these forces had relatively low numbers of stop and searches of individuals from a black background (134 and 182 searches respectively). Conversely, although Greater Manchester Police (GMP) carried out relatively high numbers of searches against individuals from a black background (801 searches), the overall search rate and relative rate in this force area was relatively low compared with other forces (11 and 4.5 respectively). This may be in part explained by GMP’s residential population which has a larger proportion of residents from minority ethnic backgrounds (excluding white minorities) compared with other forces.

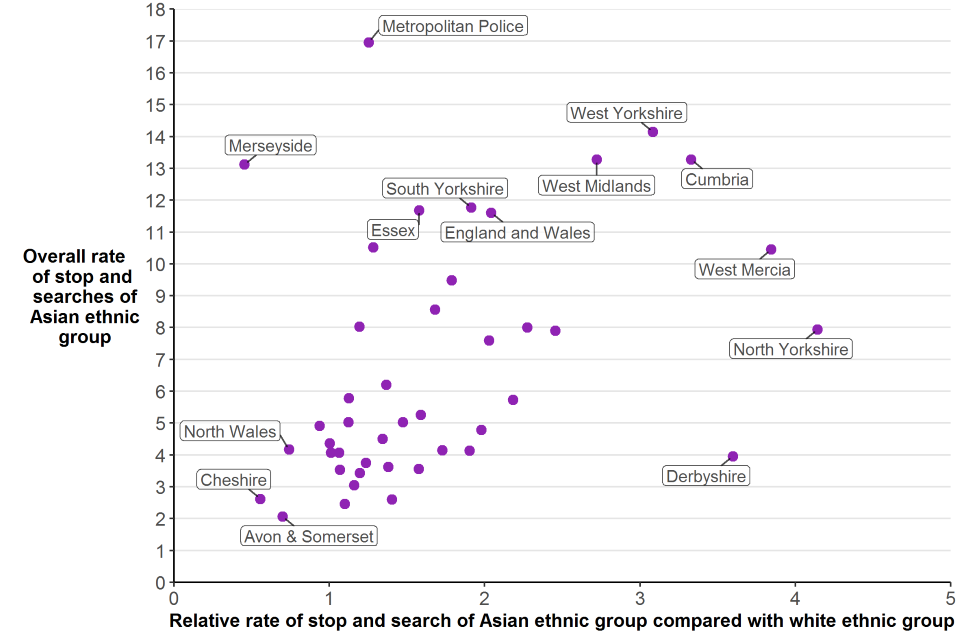

Asian ethnic group

Figure 2.17: Overall stop and search rates and relative rates for Asian individuals, by Police Force Area, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_16, Home Office

Notes:

-

City of London and British Transport Police are not shown, but they have been included in the England and Wales total.

-

Rates of stop and search are calculated using Census 2011 Estimates. These are likely to be outdated so should be treated as indicative only.

In England and Wales there were 12 stop and searches of individuals from an Asian background per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2022. The MPS had the highest overall rate of stop and search of individuals from an Asian background at 17 stop and searches per 1,000 population, followed by West Yorkshire (14 per 1,000 population). Both forces also carried out a relatively high number of stop and searches of Asian individuals (25,624 and 4,126 searches respectively). The lowest overall rate of stop and search of individuals from an Asian background was by Avon and Somerset (2 per 1,000 population).

In England and Wales individuals from an Asian background were stopped at a relative rate 2.0 times higher than white individuals. This relative rate varied between forces. North Yorkshire had the highest relative rate of 4.1. Merseyside showed a relative rate of less than 1 (0.5), suggesting that Asian individuals were stopped at a rate lower than white individuals.

The majority of forces showed a relatively low number of stop and searches against individuals from an Asian background, including some forces which showed as having high relative rates, for example North Yorkshire, Cumbria, West Mercia, and Derbyshire (112, 54, 264, and 158 respectively). The high relative rates and low volumes of searches in these areas may be partially explained by the ethnic composition of these areas, see Table A2.

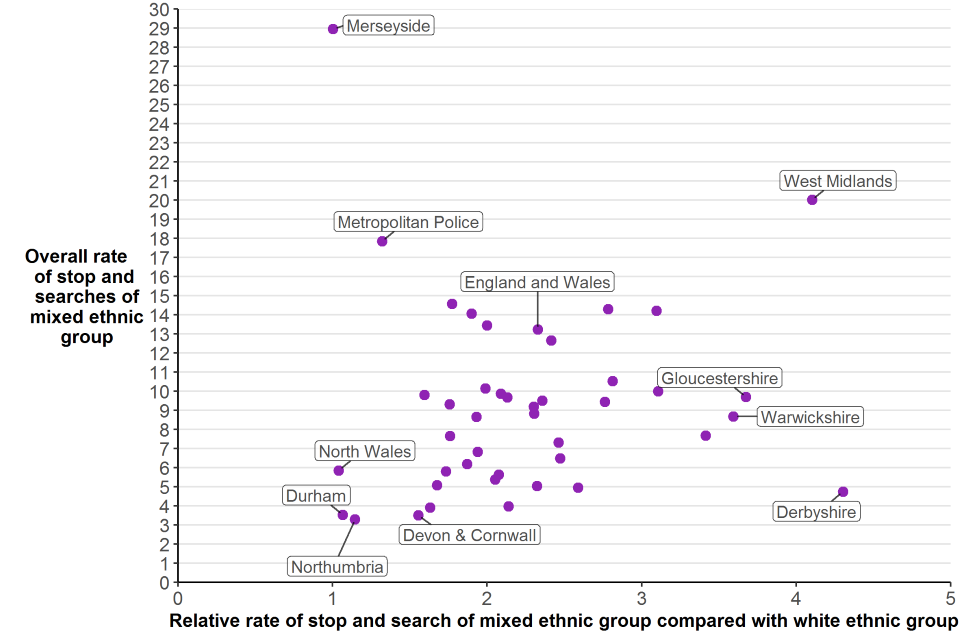

Mixed ethnic group

Figure 2.18: Overall stop and search rates and relative rates for individuals from a mixed ethnic background, by Police Force Area, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_16, Home Office

Notes:

-

City of London and British Transport Police are not shown, but they have been included in the England and Wales total.

-

Rates of stop and search are calculated using Census 2011 Estimates. These are likely to be outdated so should be treated as indicative only.

There were 13 stop and searches of individuals from a mixed ethnic background per 1,000 population in England and Wales in the year ending March 2022. Merseyside displayed the highest overall rate of stop and search at 29 stop and searches per 1,000 population, followed by West Midlands with an overall rate of 20 stop and searches per 1,000 population. Both of these police forces also had some of the highest number of stop and searches of individuals from a mixed ethnic background (607 and 1,926 searches). Northumbria had the lowest overall rate of stop and search of individuals from a mixed ethnic background, at an overall rate of 3 stop and searches per 1,000 population, followed by Devon and Cornwall (4 stop and searches per 1,000 population).

In England and Wales individuals from a mixed ethnic background were stopped at a relative rate 2.3 times higher than white individuals, the lowest relative rate compared with all other ethnic groups. This relative rate varied between forces. Derbyshire had the highest relative rate of 4.3 whilst Merseyside and North Wales had the lowest relative rate; at 1.0 times higher than white individuals. This suggests Merseyside and North Wales have an equally high search rate per 1,000 population of white individuals. However, despite similar relative rates, Merseyside carried out a higher number of stop and searches than North Wales (607 and 29 searches respectively).

West Midlands had the second highest relative rate and the second highest overall search rate and had relatively high search numbers (1,926 searches).

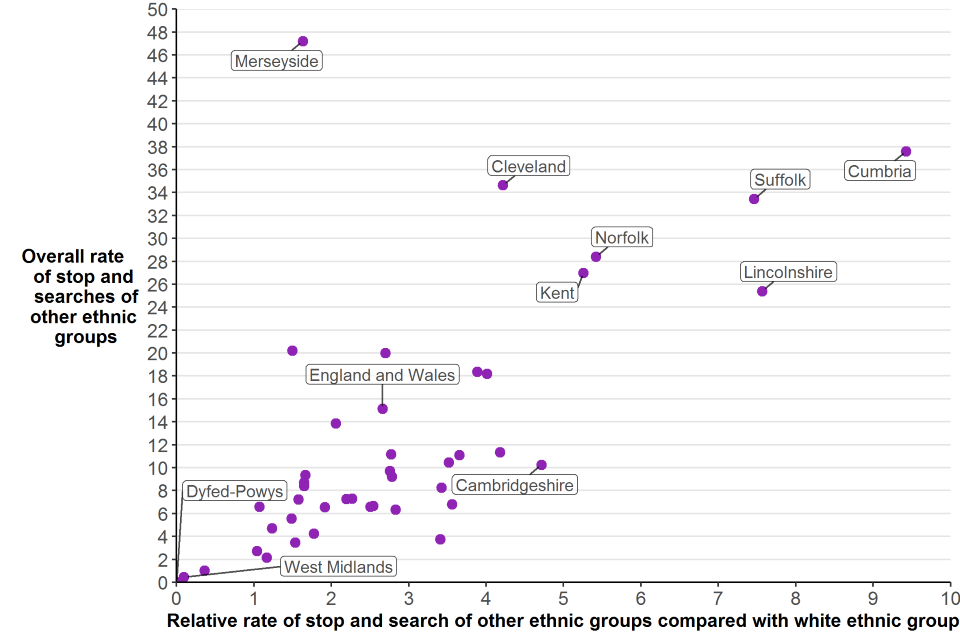

Other ethnic groups

Figure 2.19: Overall stop and search rates and relative rates for individuals from other ethnic groups, by Police Force Area, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Stop and Search table SS_16, Home Office

Notes:

-

City of London and British Transport Police are not shown, but they have been included in the England and Wales total.

-

Dyfed-Powys did not conduct any stop and searches on individuals from other ethnic groups in the year ending March 2022.

-

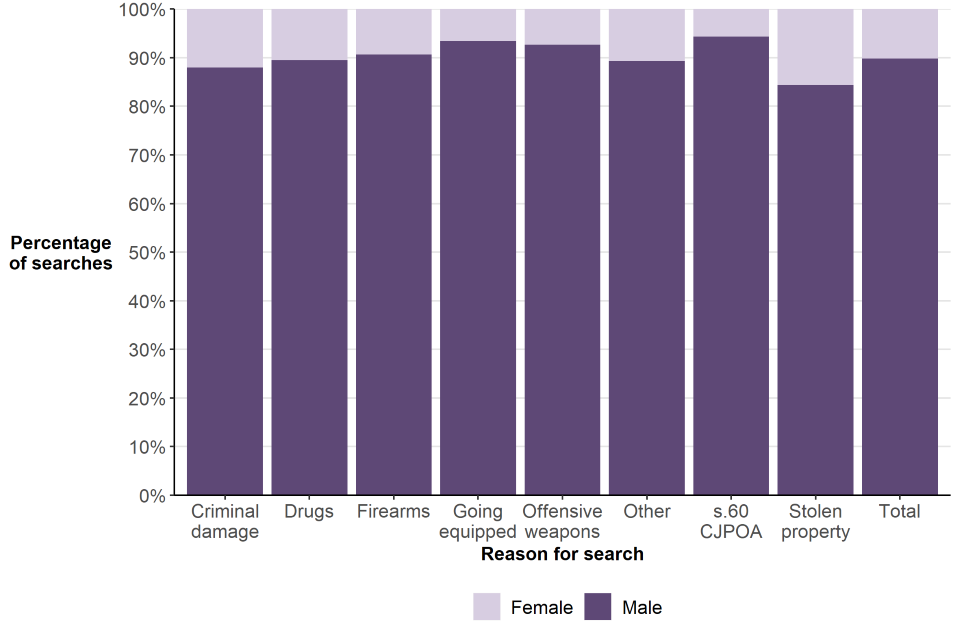

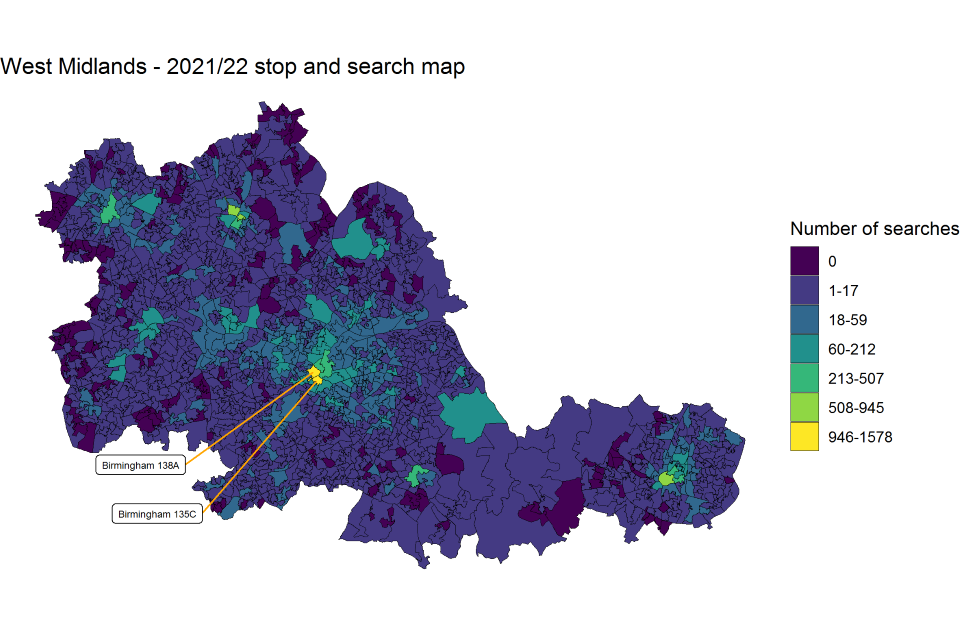

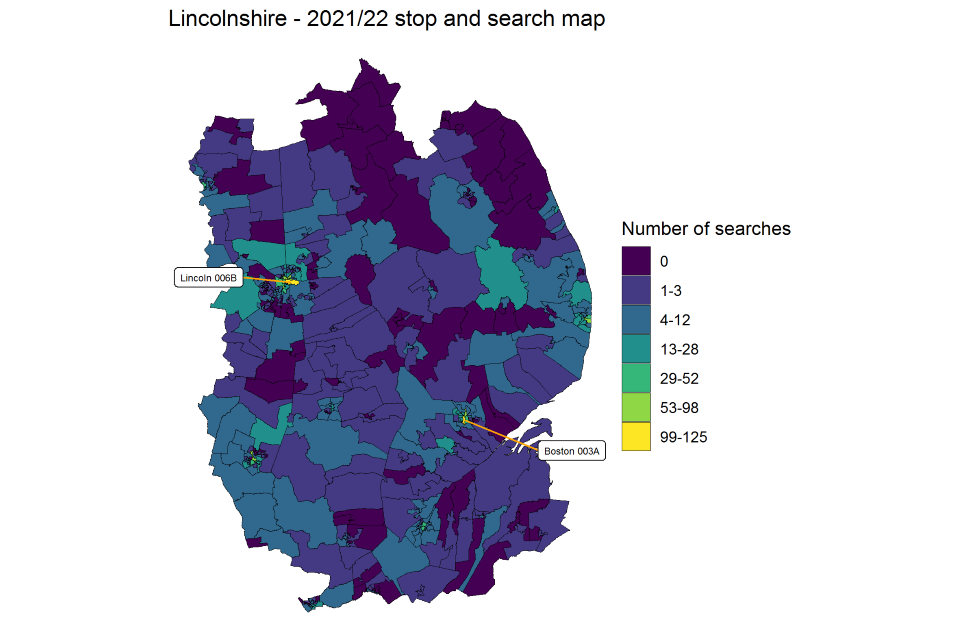

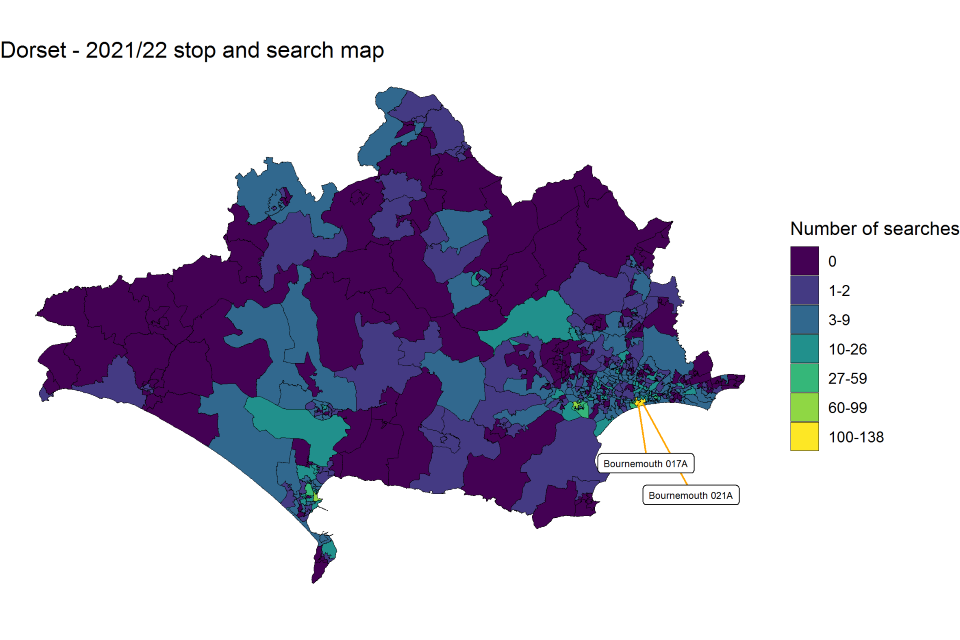

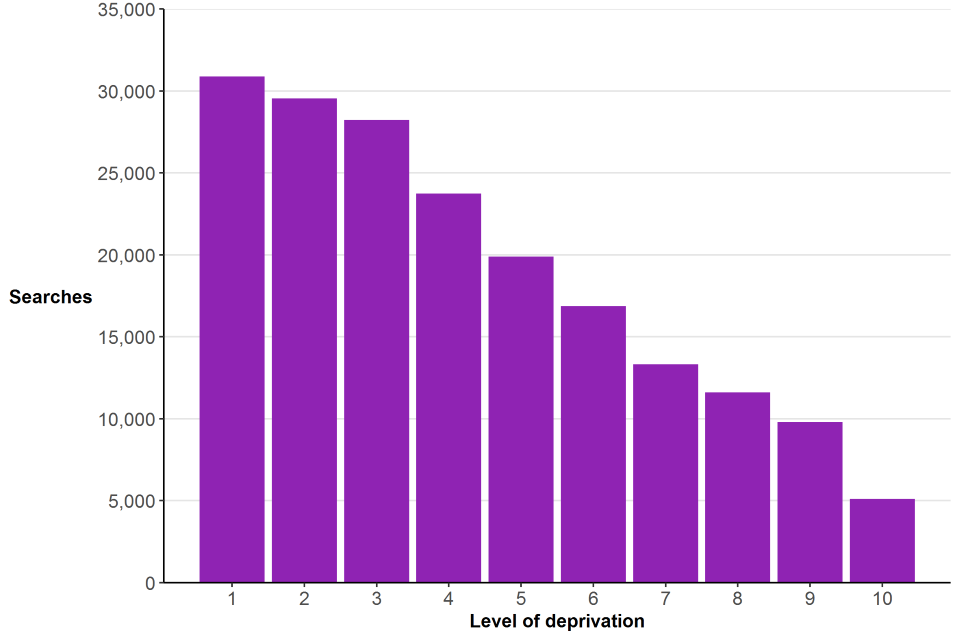

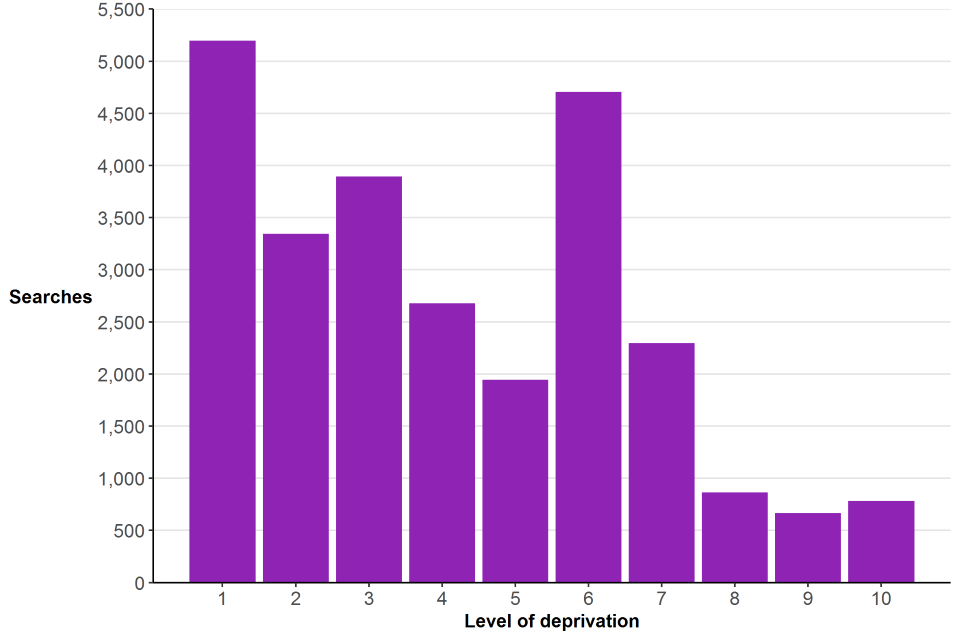

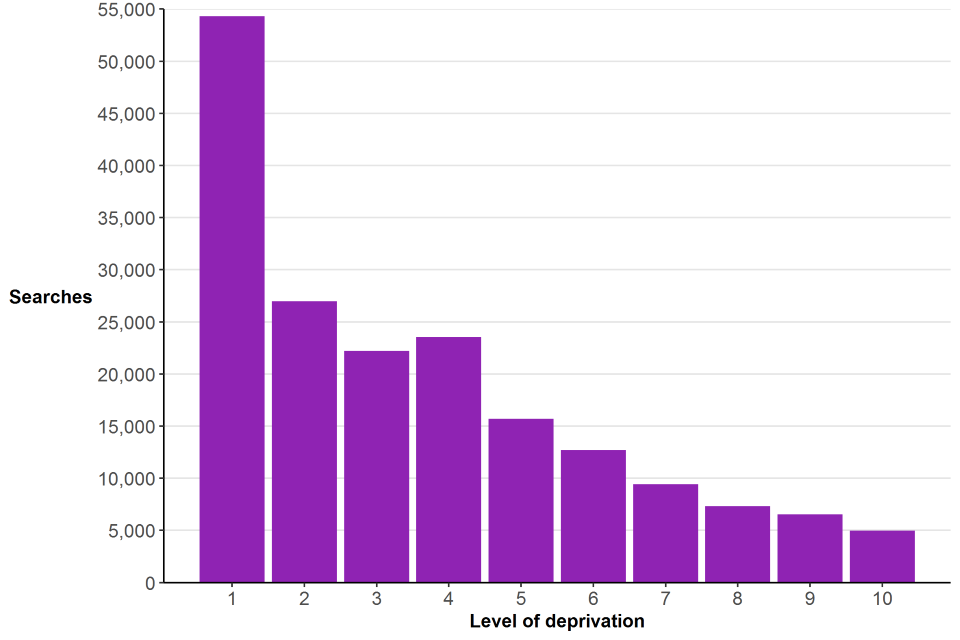

Rates of stop and search are calculated using Census 2011 Estimates. These are likely to be outdated so should be treated as indicative only.