Evaluation of the 2021/22 Funding Pilot for Local Resilience Forums

Published 30 January 2023

Applies to England

Foreword

In 2021, the Department for Levelling Up Housing and Communities (DLUHC) provided £7.5 million of funding, alongside plans for an evaluation, to Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) for one year as a pilot project. This pilot represented the first-time central government has provided direct funding to LRFs outside of funding for specific events and was a first step towards meeting the government’s Integrated Review (IR) commitment to consider strengthening their roles and responsibilities.

The aim of the pilot was to collect evidence on the potential efficacy, challenges and opportunities of providing a degree of central funding to LRFs and to provide LRFs with an opportunity to build new capacity and capability and encourage innovation within the sector, without displacing their existing partner contributions.

The evaluation used a theory-based approach to assess the outcomes, additionality, and value for money of the funding. The evaluation considered the results of three DLUHC-led surveys with all 38 LRFs and qualitative case study research with a purposive sample of 15 LRFs conducted by ICF.

We are pleased to see from the evaluation that the Funding Pilot was well received by LRFs and has allowed them to take significant steps towards delivering new capacity and capability to support focussed work on delivering improvements to specific capabilities and nationally and locally defined priorities.

Building on the success of the pilot, in late 2021 DLUHC announced a £22 million 3-year funding settlement for LRFs in England starting in the 2022/23 financial year. This additional funding will complement the contributions of partners and will allow LRFs to continue to build on the excellent progress they have made during the pilot.

We would like to thank ICF for their work on the evaluation. Our thanks also go to all LRFs for participating in the surveys conducted by DLUHC and those who undertook the qualitative case study research conducted by ICF. Finally, another thank you goes to the policy makers and analysts in DLUHC who provided input to the evaluation – reflecting the department’s broader commitment to an evidence-based approach to policy and delivery.

Stephen Aldridge

Director for Analysis and Data and Chief Economist,

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Rosehanna Chowdhury

Director for Resilience and Recovery,

Department for Levelling Up Housing and Communities

List of acronyms and abbreviations

CCU - Civil Contingencies Unit

DLUHC - Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

HMG - His Majesty’s Government

HMT - His Majesty’s Treasury

HR - Human Resources

KPI - Key Performance Indicator

LRF - Local Resilience Forum

MAIC - Multi-Agency Information Cell

RED - Resilience and Recovery Directorate

VCFS - Voluntary, Community and Faith Sector

VfM - Value for Money

WSR - Whole Society Resilience

Executive summary

Introduction

1. This report presents the findings from an evaluation of the 2021/22 funding pilot administered by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) for Local Resilience Forums (LRFs).

2. LRFs are non-statutory multi-agency partnerships that play a critical role in bringing local responders together to plan and prepare for emergencies. This is underpinned by the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (CCA) which provides a common framework for multiagency working. There are 38 LRFs in England. In April 2021 a £7.5 million LRF funding pilot was announced for the 2021/22 financial year. This represented the first direct funding of LRFs by central government, unrelated to specific risks, emergencies or events. Each LRF received £120,000 to build their capacity and £40,000-£125,000 to build their capability.

3. The aims of the evaluation were: to understand how, why and in what ways LRFs had used the pilot funding and to assess the outcomes, additionality, and value for money of this. The evaluation has drawn on the results of three surveys conducted by DLUHC of all LRFs and qualitative case study research with a purposive sample of 15 of the LRFs. It was recognised from the outset that quantitatively assessing the outcomes of the funding would not be feasible within the timeframe of evaluation. Instead, reflecting HMT Magenta Book good practice, a theory-based approach has been used to assess progress made towards outcomes in the longer term.

How LRFs have used the pilot funding

Decision-making

4. All LRFs described going through a similar process to determine how they would use their pilot funding. This was based on identifying potential new staff roles and projects the funding could be used for, consulting with local partners, and approval by an executive committee. This was not reported to be a problematic or contentious process but LRFs said it had been time constrained. This was new funding and as LRFs received their grant determination letters on 24 May 2021, already part way into the financial year, interviewees reported this had in some cases limited their ability to consult and plan strategically.

5. LRF decisions about how to use their allocated funding were informed primarily by the initial guidance issued by DLUHC, ongoing communications from the Department, and the local needs and priorities of the LRF. LRFs appreciated the flexibility to prioritise local needs afforded them by the generally well received guidance, although some felt this could have been clearer with regard to DLUHC’s expectations and strategic priorities.

How LRFs have used the pilot funding to build capacity

6. Most LRFs have used their pilot funding to increase their staff resource. By the end of 2021/22, 28 LRFs said they had taken on new staff and a further four LRFs said they had new staff who would be starting after the end of the financial year. In total, 93 new staff were identified (an average of more than 2.5 per LRF).

7. Nearly a half (45%) of new staff had been recruited for project officer roles, 15% for senior strategic roles, and 9% for project manager roles. A further 33% of new staff were recruited for ‘other’ roles (which included both senior and more junior posts). Most new staff had been recruited through either external recruitment (44%) or secondment (37%), while extensions to existing staff contracts accounted for 19%.

8. Overall the pilot funding can be seen to have appreciably boosted LRF capacity. Previously LRFs were reliant on as little as one FTE staff and in-kind contributions of staff time from partners. The addition of two or more staff was therefore significant. It enabled LRFs to take forward areas of work that they could not have otherwise progressed, reduced pressures on existing senior staff, and brought in new specialist skills and expertise.

9. Initially there were concerns that these benefits would only be temporary. Due to the one-year duration of the pilot funding, most new staff had reportedly only been employed on 6–12-month contracts. However, it was announced in December 2021 that LRFs would receive a further three years funding after 2021/22. Many LRFs said this meant they were now able to extend the contracts of new staff they had taken on using the pilot funding.

How LRFs have used the pilot funding to build capability

10. In total, 205 pilot-funded projects were reported by LRFs, with most having used their pilot funding on 3-5 projects. The scale and nature of these projects varied.

11. Over a third of projects were classified by LRFs as focusing on ‘activity in support of key national and local priorities, including supporting HMG as set out in the Integrated Review’. This included local research and consultations to inform contributions to the current national policy discourse on resilience, concerning the Resilience Strategy, Civil Contingencies Act and DLUHC’s Big Resilience Conversation[footnote 1].

12. Nearly a half of projects had a focus on ‘strengthening data, intelligence, and information flows’. This commonly included projects to scope out and/or develop a multi-agency information cell (MAIC), which would have the potential to increase the effectiveness of the LRFs response to local emergencies.

13. A third of projects had a focus on ‘promoting a whole of society approach to resilience’. This was something that LRFs commonly recognised as a key area they wanted to make progress on, reflected in projects to enhance LRFs online presence and build links with local communities and VCFS organisations.

14. A quarter of projects also had a focus on ‘other’ priorities. This included training for LRF and local partner staff to enhance their preparedness and response to local emergencies, independent reviews of LRFs structures, needs and capabilities to inform future planning, and outward-looking research into leading practice in other LRFs.

Implementation of funded activities

15. Overall, LRFs had made mixed progress in implementing their plans for using the pilot funding within the 2021/22 financial year with the short implementation time being the key limiting factor.

Progress on capacity building

16. Most LRFs reported that the new staff they planned to take on using the pilot funding had been recruited and taken up their post towards the middle or end of 2021/22, and exceptionally some new staff were only going to start after the end of the financial year.

17. Recruitment was the biggest single challenge met by LRFs in delivering on their capacity building plans. The one-year duration of funding - meaning LRFs only felt able to advertise jobs on a short fixed-term contract basis - was described as a barrier to recruiting staff at all levels but in particular to more senior roles. LRFs also had to recruit staff through the HR functions of their host organisation, and these were described as being often slow and bureaucratic. A shortage of suitably experienced and skilled personnel to fill posts and misgivings about “poaching” staff from other organisations were also cited as barriers.

Progress on capability building

18. Delays in implementing planned projects were reported by LRFs. While many had been successfully completed in 2021/22, some were expected to run over into, or only start in earnest in, the next financial year.

19. This was closely linked to the challenges LRFs encountered in recruiting new staff, because these staff were often intended to take forward projects. There was also huge diversity among LRFs in terms of their internal capacity to manage and deliver pilot funded activities on top of their day-to-day responsibilities. Some LRFs described a Catch 22 situation whereby staff were too busy to progress projects or undertake the recruitment that would potentially ease the pressures on them. Other challenges LRFs highlighted were competing demands on their time from local emergencies and events in 2021/22, and difficulties in maintaining the buy-in and coordination of local partners.

20. Despite these challenges LRFs had effectively delivered many projects within 2021/22. Having an established structure and experienced people with capacity in post to advance this work were key enablers, as was the ability to procure external expertise. Interviewees who had commissioned external contractors commented on the value of their independent status and ability to maintain momentum on pilot-funded projects.

Outcomes, outputs, and perceived benefits

21. Within the timescale of the 2021/22 financial year, there wasn’t yet clear evidence of tangible outcomes arising from the pilot funding. This is to be expected given the implementation challenges LRFs encountered and, more fundamentally, the long term nature of efforts to increase local resilience.

22. LRFs have, however, already delivered a number of outputs (including new staff in post, training, new technology, and new relationships with a wider number of VCFS organisations). It is reasonable to expect that these will result in outcomes in future. LRFs also highlighted that their pilot-funded projects often represented the foundation for follow-on activities that would deliver outcomes in the longer term. For example, independent reviews of LRFs’ needs, and capabilities undertaken using pilot funding were going to inform investment in new resources and training, which would in the longer term result in more effective response and recovery to local emergencies. Some LRFs also highlighted wider benefits of the pilot funding that had already been realised, in terms of increased buy-in from local partners and collaboration with other LRFs.

Value for money

23. It was not feasible to conduct a full assessment of the value for money of the pilot funding due to the lack of monetisable outcomes within the timeframe of the evaluation. Nonetheless, the evidence available at this point suggests the pilot funding is likely to deliver value for money in the long term. The pilot funding amounted to a total investment by central government of £7.5 million and the potential monetisable savings arising out of this are significantly larger. For example, Storm Desmond was estimated to inflict damage of up to £500 million in Cumbria in December 2015. The UK Treasury also currently uses £2 million as the value of one single prevented fatality in economic appraisal. Therefore, the pilot funding would need to have only a small effect in reducing the costs of responding to major emergencies to provide good value for money.

24. There was no evidence that the pilot funding had displaced funding that LRFs receive through local partner contributions. Every interviewee reported that the activities initiated using the pilot funding by their LRF were additional to what could have been undertaken otherwise.

Looking ahead and reflections on the pilot funding

Reception to future funding

25. LRFs welcomed the news of the further 3-year funding to follow the 2021/22 pilot funding. Equally, they did also often argue the case for LRFs to be funded on an even longer-term statutory basis in order to ensure they can meet their increasing responsibilities from central government and reflect the long-term nature of the kinds of project work they need to undertake to do this effectively.

26. LRFs expressed an appetite for more dialogue and guidance from DLUHC over how the next 3 years’ funding should be spent and how plans should align to government priorities and the revised National Resilience Strategy and Civil Contingencies Act. Some also suggested the implementation of future funding should be more closely monitored, for example against key performance indicators, although these would potentially have to be established on a case-by-case basis given the diversity of LRF activities.

Plans for using the future funding

27. LRFs were generally in the early stages of planning how they would use the future funding when interviewed but anticipated deploying it for the following purposes:

- To consolidate and further grow their capacity – this included plan to extend contracts on existing pilot-funded posts and create further new posts.

- To implement programmes of training and exercises – often acting on the needs and priorities they had identified through pilot-funded reviews and research.

- To initiate or expand the scope of work on whole society resilience – in some cases building on initial progress make through pilot-funded projects.

- To continue to strengthen data and intelligence flows and establish a MAIC – this included plans for LRF collaboration to develop regional systems and solutions.

Reflections on the pilot funding

28. LRFs were grateful for the pilot funding and felt it addressed a real and growing need for additional resourcing. There was widespread appreciation of the freedom to use funding to meet local priorities given that LRFs cover diverse areas and populations. Equally, some LRFs said they would have liked more strategic oversight and ongoing guidance from DLUHC. A few also queried the formula (based on population size and deprivation) used to calculate how much capability funding each LRF received.

29. There was an appetite amongst LRFs for greater collaboration and shared learning (to avoid duplication of effort, combine intelligence, and find economies of scale). LRFs were also keen for more opportunities to share expertise and thinking with DLUHC, particularly around newer and more complex areas of work such as MAICs and whole society resilience. In addition, while the pilot funding was felt to signal government’s recognition of the importance of LRFs, it raised questions about their future status and remit. Many said they would welcome a continued dialogue with DLUHC about this.

Recommendations

30. The following recommendations are made to help inform future central government funding and support for LRFs:

- Central government funding for LRFs should continue beyond 2021/22 (something that has now been enacted with the announcement of a further 3-year’s funding from 2022/23) – to reflect the ongoing challenges LRF’s face, the breadth of their remit, and the variable and often modest access they have to local funding.

- The timing and terms of future support should be communicated to LRFs with as long a lead-in time as possible – to maximise the effectiveness of how it is used.

- Continue to include flexibility for funding to be used across more than one financial year – to reflect their day-to-day challenges and the long-term nature of their remit.

- Provide a framework for the expected uses of future funding but continue to allow significant freedom within this – to reflect the fact each LRF and the local population they are there to support is different.

- Continue to communicate an unambiguous message (including in future funding guidance) on the additionality of central government support – to aid LRF discussions with local partners about their contributions and protect against displacement.

- Maximise opportunities for shared learning and collaboration between LRFs – given the potential added value and value for money gains from this.

- Facilitate support around effective project planning and management for LRFs – to help ensure future funding is deployed effectively and efficiently.

- Enhance the role of DLUHC’s team of local area-based Resilience Advisors to advise on – and support – the deployment of future funding by LRFs.

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1 This report presents the findings from an evaluation of the funding pilot that the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) provided to Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) in 2021/22. The evaluation has been undertaken by ICF.

Overview of the LRF funding pilot

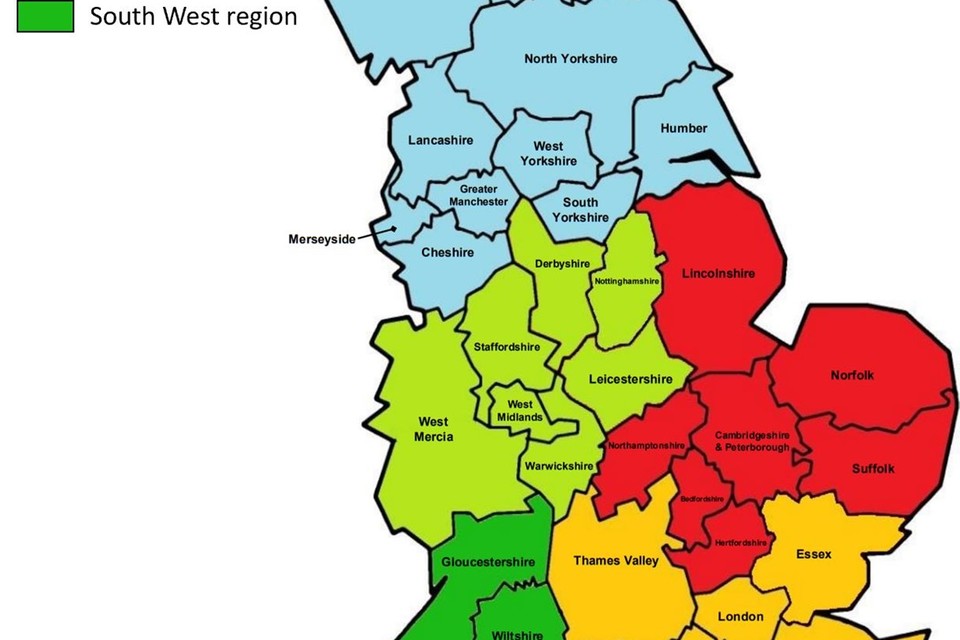

1.2 LRFs are non-statutory multi-agency partnerships that play a critical role in bringing local responders together to plan and prepare for emergencies. There are 38 LRFs in England (geographically based on police force areas) which each bring together local ‘category 1’ and ‘category 2’ responder organisations.[footnote 2]

1.3 In March 2021, the government’s Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (IR) included a commitment to, “consider strengthening the role and responsibilities of local resilience forums (LRFs) in England”. DLUHC’s Resilience and Recovery Directorate leads on this commitment and as a key first step, DLUHC announced a one-year LRF funding pilot (2021/22 financial year) in April 2021 to test the efficacy, challenges and opportunities of HMG providing a degree of central funding to LRFs.

1.4 The funding pilot represented the first direct funding of LRFs by central government. Previously LRFs only received central government funding related to specific risks, emergencies or events (e.g., COVID-19, and preparations for a possible ‘no deal’ EU exit). Other funding for LRFs currently comes from financial and in-kind contributions from partners, although the scale of these varies from LRF to LRF. The amount of staff resource that LRFs had prior to the funding pilot also varied, with some reliant on one FTE member of staff plus in-kind contributions of staff time by local partners.

1.5 The total funding available for the pilot was £7.5 million. Grant determination letters specifying how much pilot funding each LRF would receive were circulated on 24 May 2021 and LRFs received their allocation on 1 June 2021. The funding was issued to LRFs through one upfront Section 31 grant. The grant was un-ringfenced which gave LRFs the flexibility to use the funding according to their own local priorities. DLUHC provided guidance for the fund to support LRFs in deciding how they may like to target their funding. To prevent LRFs holding funding in reserve, DLUHC encouraged LRFs through the guidance that LRFs to spend their funding within the pilot year.

1.6 There were two strands to the pilot funding:

- Capacity building: £120,000 per LRF was allocated with the broad expectation that this would be used to fund core staffing capacity to work on new strategic projects or initiatives.

- Capability building: Between £40,000 and £125,000 per LRF was allocated (based on population size and deprivation with upper and lower limits applied) to support focused develop new or improved capabilities, strategic projects, or wider initiatives.

1.7 This meant that each LRF received a minimum of £160,000 of combined capacity and capability funding.

1.8 A further £230,000 of the funding pilot settlement was reserved for an Innovation Fund. The Innovation Fund was a biddable fund, designed to encourage LRFs to innovate across boundaries and partners to deliver projects that tested ideas for new ways of working. Following the strength of bids from LRFs, the Innovation Fund was later increased by an additional £252,352. Due to the timing of the Innovation Fund (projects funded by the Innovation Fund began in January – February 2022), the Innovation Fund was out of scope of this evaluation and will be evaluated internally by DLUHC. Annex 4 provides an overview of the eight projects that were awarded innovation funding.

1.9 In December 2021, it was announced to LRFs that the 2021/22 pilot funding would be followed by a further three years of central government funding from 2022/23. The future funding was beyond the planned scope of this evaluation but initial reflections on this from LRFs were collected and are included in this report.

Aims of the evaluation

1.10 The aim of the evaluation was to address the following research questions:

Inputs

1. How did LRFs administer the money throughout the financial year?

2. How did LRFs decide what to spend the money on?

3. Did this funding displace existing local funding arrangements?

4. What do LRFs think about future funding?

Activities/Outputs

5. Did the money fund new activities?

6. Did the funded activities increase capability within the LRF (the ability to do something)?

7. Did the funded activities increase the capacity of the LRF (the bandwidth/ resources to actually do it)?

Outcomes/Impact

8. What outcomes have these activities delivered?

9. Does it change the relationship between LRFs and central government?

10. Did the funding represent value for money?

11. Were the outcomes additive, or did the funding displace existing local funding arrangements?

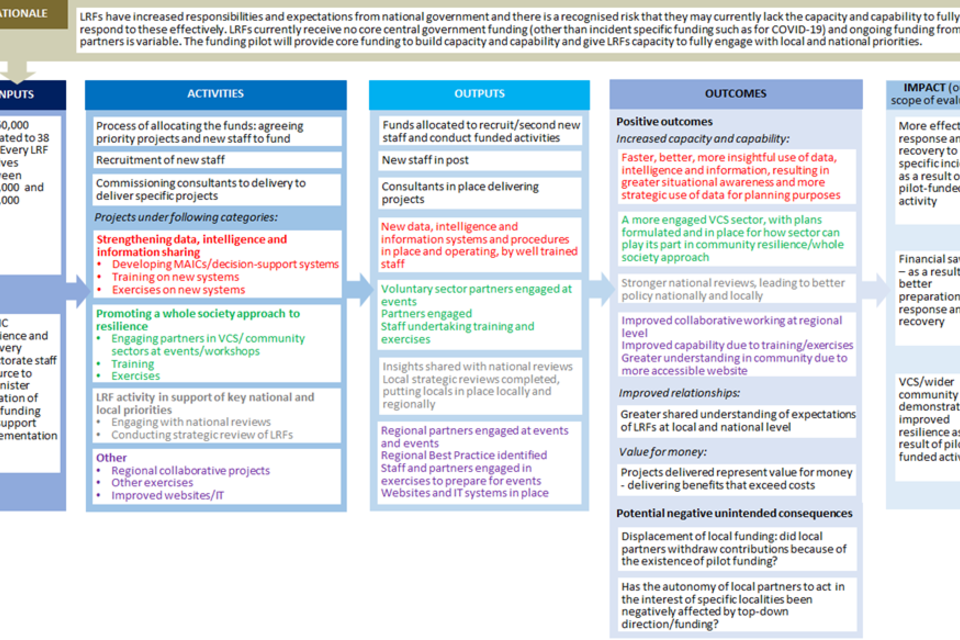

1.11 The research questions were modelled on a Theory of Change for the funding pilot initially developed by DLUHC and further refined in the course of the evaluation (see Annex 2).

Evaluation methodology

1.12 The evaluation has been based on two main evidence sources:

DLUHC surveys of LRFs

1.13 DLUHC conducted surveys of all 38 LRFs at three timepoints following the announcement of the pilot funding. The Phase A survey in May 2021 asked LRFs to provide baseline information on their pre-pilot staffing and funding contributions they receive from local partners. The Phase B survey in July-August 2021 focused on how LRFs planned to use their pilot funding. The Phase C survey in March 2022 asked LRFs to provide information on the implementation of their planned activities, future partner contributions, and reflections on the pilot funding.

1.14 Results from the surveys were shared in full by DLUHC with ICF to feed into the evaluation.

Case study research with LRFs

1.15 Qualitative case study research was conducted by ICF with a sample of 15 LRFs. The sample was purposively selected to represent different LRF characteristics, in terms of population size, geography including region and rural versus urban make up, and lead organisation.

1.16 A total of 38 individuals were interviewed across the case study LRFs. This comprised:

- 11 LRF Chairs.

- 14 Secretariats (or managers/coordinators of the LRF’s Secretariat team).

- 3 Project managers.

- 10 Project officers/executives.

1.17 Interviews were conducted in February-March 2022 by telephone or on Microsoft Teams. A topic guide (see Annex 3) was used in each interview to ensure consistent coverage of key areas of interest.

Strengths and limitations of the evaluation

1.18 The combination of survey results for every LRF (all 3 of the DLUHC surveys achieved a 100% response rate) and qualitative research with a representative sample of over a third of LRFs provided a strong basis for the evaluation and provided scope for triangulating findings across the two evidence sources. There was also a high degree of commonality in the key themes that emerged out of each evidence source, suggesting no great bias or misrepresentation in either set of results.

1.19 One limitation is the extent to which it has been possible to quantitatively assess outcomes, impacts and the value for money of the pilot funding. This is partly because of the diversity of what LRFs used their funding for (not amenable to standardised metrics or KPIs) and, more substantially, because changes to capacity and projects to increase the capability of local areas to respond to major incidents take time. Major incidents also occur sporadically in place and time, meaning outcomes may take years to materialise. It was unfeasible to expect many quantifiable outcomes arising out of the pilot funding within the 2021/22 financial year and the timescale of the evaluation (although, as the report goes on to discuss, there is a reasonable basis to expect outcomes materialising from the funding pilot in the longer term). DLUHC intend to continue to capture the longer-term outcomes and impact of the pilot funding through the future evaluation of the three-year funding settlement.

1.20 This limitation was recognised from the start and the evaluation did not set out to quantitatively estimate impact using an experimental or quasi-experimental approach. Instead, reflecting HMT Magenta Book good practice, a theory-based approach has been used to qualitatively assess progress made towards future outcomes and impacts. The value for money element of the evaluation has also been based on a predominantly qualitative assessment, considering whether the funded activities are expected to be beneficial and proportionate to the resources used, and whether the process of allocating resources to the funded activities is conducive to delivering value for money.

Structure of the report

1.21 The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 presents findings on how LRFs have used the pilot funding.

- Chapter 3 reports on the implementation of pilot funded activities.

- Chapter 4 provides a value for money assessment of the pilot funding.

- Chapter 5 details LRFs’ reflections on the pilot funding and their thoughts on future funding.

- Chapter 6 provides conclusions and recommendations.

Chapter 2. How LRFs have used the pilot funding

2.1 This chapter provides findings on how LRFs decided what they would use their allocation of pilot funding for and how they subsequently used it – both in terms of building capacity and building capability.

Decisions about how to use the pilot funding

2.2 After the announcement of the pilot funding and communication of the amount they would be allocated, all LRFs described going through a similar process to determine how they would use their funding.

2.3 The first stage in determining how they would spend their funding was identifying potential job roles (capacity building) and projects (capability building) their pilot funding could be used for. Some described this as straightforward – they had a long list of roles and/or projects that they and their local partners had wanted to invest in for several years but had never previously had the resource to do so. Others described a more extensive process – starting with a blank sheet – and involving consultations with partners to first identify priorities and ideas for the use of the funding and then develop these into proposals. The next stage was for proposals to be considered and approved by the LRF’s executive board or committee (usually composed of the chief officers of the local partners).

2.4 Overall, interviewees did not present this as a problematic or contentious process. There were no reported cases, for example, of serious disagreements arising between local partners about how to use the funding or of proposals being rejected out of hand by an LRF’s executive board or committee. However, interviewees frequently described it as a time-constrained process. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the funding became available and was allocated to LRFs after the start of the 2021/22 financial year. This was highlighted as a particular challenge by some of the LRFs with the largest numbers of partners to consult with and secure approval from for how the pilot funding would be used. Ultimately LRFs felt they had done as well as they could in determining how to use the funding in the time available to them. Equally, with the benefit of more time, it was suggested that proposals could have been developed further.

2.5 The main factors informing LRFs’ funding decisions were:

The grant determination letter and initial DLUHC guidance

2.6 In May 2021 LRFs received their grant determination letter, and DLUHC issued a detailed 23-page guidance document which included expectations for how the funding would be used. Interviewees cited these as influential in how they had decided to use their funding. Both set out that £120,000 of their funding should be used towards capacity building and the remainder towards capability building, and the guidance gave examples of job roles (mentioning ‘strategic personnel’) and project types the funding might be used for. At the same time, it stated that: “We are not specifying exactly how this funding should be used or targeted, as each LRF will want to adapt their use of the funding to their specific circumstances.”. The funding was intentionally issued to LRFs in one upfront grant which was un-ringfenced, meaning there were no explicit conditions dictating how or when the funding should be spent.

2.7 In some cases interpretations of how proscriptive the guidance was varied. Initially most interviewees said they perceived they were expected to stick closely to it, particularly in terms of how much they put towards capacity (£120,000) versus capability (the rest). At the most extreme, one LRF had interpreted from the guidance that they were expected to use their funding to fill two senior strategic roles (despite the reference to ‘strategic personnel’ being given as an example) and this was what they initially embarked on doing. Conversely there were some LRFs who indicated that from the outset they had felt comfortable in planning to use either more or less than £120,000 of their funding on capacity building, depending on their local needs.

Ongoing DLUHC communications

2.8 LRFs described ongoing communications from the Department as “light touch” and some expressed surprise there had not been closer direct oversight of how LRFs were using their funding. Most LRFs welcomed the freedom this gave them to modify and adapt their use of the funding over time, in response to new emerging local needs. For example, one LRF has abandoned plans to recruit one new member of staff after several months of unforeseen delays and reallocated the funding earmarked for this to a project. Another LRF redirected some of their pilot funding to meet the costs of responding to a local need that emerged partway through the financial year. A couple of interviewees suggested there could have been more tightly defined guidance and more subsequent scrutiny by DLUHC but there was no evidence that the light-touch approach adopted had resulted in any inappropriate use of the pilot funding.

Their own local challenges and needs

2.9 In line with the guidance and communications from DLUHC, this was the other main factor determining how LRFs decided to use their funding. LRFs are diverse and much of the decision-making process described above was concerned with identifying what the most pressing needs were within the LRF and developing proposals for using the funding accordingly.

Conversations with other LRFs

2.10 Despite their diversity, all LRFs have common responsibilities and - even prior to the pilot funding – reported that they are often in communication with each other to share ideas and best practice. After the announcement of the pilot funding some had developed proposals for pooling a proportion of their allocation to take forward joint projects. Steps were implemented by DLUHC to facilitate this early on, through bi-weekly engagement sessions for LRFs to share their ideas, although some LRFs suggested the Department could have done more to this end.

Consideration of what was achievable within the financial year

2.11 The extent to which LRFs factored this into their decisions appeared to vary. Some had interpreted the guidance as directing them to use all their funding by the end of 2021/22 and had planned accordingly. Others reported that they saw the pilot funding as an opportunity to demonstrate to central government their ability to use funding effectively and achieve something tangible with it in the time available. In some cases it appeared that the LRF had not fully considered whether their proposals were achievable in this timeframe or, had expected from the outset that they may overrun into the next financial year but did not perceive this to be a concern.

What LRFs have used the pilot funding for

Capacity building

2.12 The Phase C survey conducted towards the end of the 2021/22 financial year asked LRFs what new staff they had taken on using the pilot funding. Twenty-eight LRFs said they had taken on one or more new members of staff within the financial year and a further four said they had new staff who would be starting after the end of the financial year. In total, 93 new staff were identified (an average of more than 2.5 per LRF). Equally, as illustrated in Table 2.1, numbers varied between the LRFs and six LRFs reported no new staff in their survey returns.

Table 2.1 New staff appointed using pilot funding

| Number of new staff (inc. staff expected to start after end of financial year) | Number of LRFs |

|---|---|

| 0 | 6 |

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 11 |

| 4 | 6 |

| 5 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 |

| Total | 93 |

2.13 Details of each new staff role were not always given in the survey returns but, where they were, the majority were reported to be full time roles on fixed-term 6- or 12-month contracts. This is consistent with the case study interview findings in which only one LRF across the sample of 15 reported that a new member of staff had been recruited using the pilot funding on a permanent rather than fixed-term contract.

2.14 It is also evident from the survey and case studies that the differences between the number of new staff each LRF had taken on – ranging from 0 to 7 – may be less marked than they first appear.

2.15 LRFs reporting the highest numbers of new staff included some relatively low-cost extensions to existing contracts rather than brand-new full-time roles. At the other end of the spectrum, LRFs reporting no new staff appeared to fall into two camps: those that had pragmatically decided from the outset, or as things progressed, to use their funding towards capability rather than capacity building (generally LRFs that already had higher levels of staff resource); and those that had encountered significant delays in using their pilot funding for any purpose (but who still might conceivably use it towards new staff in the next financial year). LRFs were positive about the flexibility they had been granted with the pilot funding to make these sorts of decisions and potentially carry over some of it into the next financial year.

2.16 The Phase C survey also asked LRFs about the types of job role they had recruited new staff to fill. As shown in Table 2.2, nearly a half (45%) of these were mid-level project officer roles, while senior strategic roles accounted for 15%. The ‘other’ category contained a mix of what might be classified as senior roles and more mid-level and junior roles (including, for example, a communications manager, a training and development lead, a business support officer, and admin assistants).

Table 2.2 Types of staff role filled using pilot funding

| Type of role of new staff (inc. ones who will start after end of the 2021/22 financial year) | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| LRF Senior Strategic Officer | 14 | 15% |

| LRF Project Manager | 8 | 9% |

| LRF Project Officer | 41 | 45% |

| Other | 30 | 33% |

2.17 The case study interview findings highlighted that many of the new project officer and project manager roles had been recruited to work on the projects that LRFs also planned to deliver using the pilot funding – meaning their efforts towards capacity and capability building were closely linked. More senior roles were also generally perceived to be harder to fill, especially when a 6 or 12 month fixed-term contract was all most LRFs felt able to offer due to the time-limited nature of the pilot funding, and at least one LRF indicated they had abandoned initial attempts to recruit a senior role and focused on less senior project officer roles instead for this reason.

2.18 LRFs reported in the Phase C survey that most new staff had been recruited through either external recruitment or secondment – typically from partner organisations such as a local authority. There were also a minority where pilot funding had been used to extend the contract of staff who had previously been contracted to work part or full time for the LRF.

Table 2.3 How new staff were recruited

| How staff role recruited | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| External recruitment | 38 | 45% |

| Secondment | 31 | 36% |

| Extension of current staff contract | 16 | 19% |

2.19 Chapter 3 discusses the challenges and opportunities that LRFs found in recruiting new staff in detail, but it is worth noting here that there were particular challenges reported with external recruitment, while secondments and contract extensions were – in relative terms – generally reported as less challenging.

2.20 Overall, and despite the differences between LRFs and some of the challenges already alluded to, the evidence shows that the pilot funding did appreciably boost the capacity of LRFs. Prior to the pilot funding some LRFs were reliant on as little as one FTE staff and sporadic in-kind contributions of staff time from partner organisations. In that context, the addition of two or more staff was described as significant. It enabled such LRFs to take forward areas of work that they could not have otherwise progressed and that should contribute to increased resilience in the longer term. This was through new staff resource recruited directly to work on new projects but also indirectly through new staff taking some of the day-to-day admin burden off senior LRF staff so they could bring their expertise to bear on key work streams.

2.21 In addition, it was reported that the pilot funding had enabled LRFs to bring in new specialist skills and expertise. Most of the new staff taken on using the pilot funding appeared to have come from a general resilience/emergency planning background but some LRFs said they had taken a conscious decision to recruit individuals from a consultancy background or those with specialist IT or analytical skills. Such experience and skills were considered increasingly valuable for LRFs in order to perform their role.

2.22 The one caveat with these positive findings is that most of the benefits reported here were potentially temporary. Most LRFs made it clear that their need to build their core staffing capacity is ongoing and anticipate that this may even increase year to year as central government develop their Integrated Review commitment to strengthen LRFs. After the short-term contracts of staff employed using the pilot funding came to an end, LRFs interviewed early in the evaluation indicated they would not have the resources to continue to employ them or described this as uncertain.

2.23 However, the announcement of a further three-years of funding from 2022/23, which occurred midway through the evaluation, changed the picture. As Chapter 5 goes on to discuss, some LRFs interviewed after the announcement were already giving consideration to using the future funding to extend the contracts of staff, they had taken on using the pilot funding.

Capability building

2.24 Capacity building in practice meant projects, initiatives or streams of work undertaken by LRFs using pilot funding. In total, 205 pilot-funded projects were reported by LRFs in the Phase C survey. Table 2.4 shows that the majority of LRFs reported 3-5 projects but also that there was a range above and below this.

Table 2.4 Pilot-funded projects reported by LRFs

| Number of projects | Number of LRFs |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 8 |

| 4 | 5 |

| 5 | 8 |

| 6 | 4 |

| 7 | 4 |

| 8 | 1 |

| 9 | 1 |

| 10+ | 4 |

| Total | 205 |

2.25 Again, some of the apparent differences between LRFs is potentially misleading. Interpretations of what qualified as ‘a project’ differed between LRFs. Those reporting the highest numbers of projects included quite small-scale areas of work as a project in their survey returns. Equally, some of the disparity evident in Table 2.4 reflected real differences in how LRFs had used their pilot funding.

2.26 The nature of the projects that LRF had instigated using the pilot funding was very diverse and defies easy classification. The guidance provided by DLUHC to LRFs set out a broad expectation that funding: “should be focussed on addressing key national priorities as set out in the Integrated Review and to support the development and delivery of the National Resilience Strategy” and gave the following as examples of what this may include:

- LRF activity in support of key national and local priorities, including supporting HMG as set out in the Integrated Review

- Strengthening data, intelligence, and information flows

- Promoting a whole of society approach to resilience

2.27 LRFs were subsequently asked in the DLUHC surveys to indicate which of these strategic priorities their pilot-funded projects were focused on. LRFs were allowed to select more than one priority for a project and there was also an ‘other’ response option. Table 2.5 shows the results from the Phase C survey.

Table 2.5 Focus of pilot-funded projects on strategic priorities

| Strategic priority | Number of projects focused on this | % of all projects |

|---|---|---|

| LRF activity in support of key national and local priorities, including supporting HMG as set out in the Integrated Review | 78 | 38% |

| Strengthening data, intelligence and information flows | 92 | 45% |

| Promoting a whole of society approach to resilience | 65 | 32% |

| Other | 47 | 23% |

2.28 This indicates good coverage across the 3 strategic priorities, with around a third or more of pilot-funded projects focusing on each. It also provides one high-level means of classifying the different pilot-funded projects that LRFs described. The following sections do not attempt to convey the full diversity of this but give an overview of common types of project for each strategic priority.

LRF activity in support of key national and local priorities, including supporting HMG as set out in the integrated review

2.29 The inclusion of both national and local priorities in this description, and the fact that local priorities vary for different LRFs, meant that a lot of different types of project were reported to have this focus.

2.30 One common type of project that fell under this banner was work focused on contributions to the national policy discourse on resilience - including government-led work ongoing in 2021/22 to develop a new Resilience Strategy and review the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, and DLUHC’s ‘Big Resilience Conversation’. LRFs have a critical contribution to make to this given they are the principal mechanism for multi-agency co-operation and co-ordination under the Civil Contingencies Act. Some LRFs had used a proportion of their pilot funding to undertake quite extensive programmes of local research and consultation to inform submissions to government.

2.31 For example, one LRF reported that they had conducted 18 workshops with local partners and community groups to inform a joint submission to the 2021 national call for evidence for the National Resilience Strategy on behalf of the local area. As well as the contribution this made to the national discourse it was perceived to have wider benefits in terms of greater shared understanding and enhanced relationships between the LRF and other local organisations with a stake in resilience.

Strengthening data, intelligence and information flows

2.32 Projects with this focus were generally technology-based and involved the development of new tools, online repositories and software to enhance the ability of the LRF to respond more effectively to emergencies.

2.33 For example, several LRFs had projects that were either scoping out or developing a MAIC (Multi-Agency Information Cell). MAICs provide a shared platform to quickly analyse, display and disseminate information in the case of an emergency, drawing on information and expertise from many sources rather than a single organisation.

2.34 There were also LRFs that had projects to develop other tools including, for example, a situational awareness app to allow real-time share of information and images by different individuals on the ground during local emergencies.

Promoting a whole of society approach to resilience

2.35 The need for a whole society approach to resilience was highlighted in the government’s 2021 Integrated Review. It was also something that LRFs commonly recognised as a key area they wanted to make progress on. This was reflected in projects using the pilot funding that focused on increasing engagement with resilience information and activities amongst LRFs’ local communities and voluntary sector organisations.

2.36 Several projects were focused on enhancing an LRF’s online presence, in order to make information about resilience and their role more accessible and engaging to a wider audience. This included upgrades to LRFs’ existing websites, which one interviewee acknowledged could be “stylistically old-fashioned”. One LRF had also researched and developed a social media presence on the Nextdoor.com platform. This allowed the LRF to target information at specific post code areas in their area – potentially critical for reaching local communities during an emergency. Content was also being created and posted for all residents on the platform, including explainer videos, infographics, polls, and a resilience quiz developed by a local university.

2.37 As well as these online-based approaches, some projects under the whole society heading focused on face-to-face engagement and consultations with local community and voluntary sector organisations. These were to share information and start the conversation about their respective roles in responding locally to emergencies and opportunities for future, greater, coordination. Additionally, two LRFs had provided small grant funding to local groups and organisations to enable communities to better prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies and major incidents. Grants had been used, for example, to purchase new equipment (such as radio sets and defibrillators for community venues) and for community first aid training.

2.38 Interviewees generally emphasised that these projects were early steps for their LRF in realising a true whole society approach to resilience but were positive about progress made and keen, funding-permitting, to continue and build on this over the next few years.

‘Other’

2.39 Some of the projects LRFs were undertaking using the pilot funding did not fall neatly under any of the three strategic priorities discussed above but were often highlighted as significant by interviewees, and as having potential longer-term benefits for the capabilities of their LRF.

2.40 This included several reported reviews of the internal structures, capabilities and needs of an LRF itself (often commissioned out to provide an independent expert perspective) and outward-looking research into best practice in other LRFs (for example around newer resilience risks such as cyber security). The output of such projects was typically a report and a set of recommendations that interviewees highlighted would be impactful in future in informing subsequent changes to enable the LRF to function more efficiency and/or effectively, for example by demonstrating the business case to local partners for additional resource or training.

2.41 Projects with an ‘other’ focus also included programmes of training for core LRF staff and staff in wider local partner organisations concerning different aspects of resilience (including cyber exercises, immersive training for chief officers to achieve ‘gold commander’ accreditation, major emergency centre training events, courses delivered by the national Emergency Planning College, and social media training) intended to increase the effectiveness of local responses to future emergencies.

Chapter 3. Implementation of funded activities

3.1 This chapter presents evidence of the progress made by LRFs in building capacity and capability through pilot funding. It draws primarily on qualitative data collected through interviews with stakeholders in case study LRFs triangulated with evidence from Phase B and C surveys.

Progress on capacity building

3.2 Overall LRFs have made different rates of progress in implementing their planned programmes of funded work as set out in their Phase B returns. The key factor impinging on progress was the short-term nature of the funding which both presented a challenge to recruiting to new posts in an already difficult labour market and limited the time available to consult with partners, plan and execute programmes of activity.

3.3 Interviewees noted that LRF partner agencies do not have the agility to spend money quickly and Phase C returns indicate that of all 38 LRFs only six (16%) expected to have spent all their pilot funding by the end of the 2021/22 financial year. It should be noted however that LRFs have been enabled to carry forward pilot funding into the next financial year and were confident when interviewed that they would be able to spend against their original plans.

3.4 Recruitment was the biggest single challenge met by LRFs in delivering on their capacity building plans with five LRFs reporting to the Phase C survey that they had taken on no additional staff. The 12-month duration of funding was described as a barrier to recruiting staff at all levels but in particular to more senior roles.

3.5 One LRF had established an agreement to carry the risk of appointing to a longer-term contract in order to secure a high calibre postholder.

3.6 Interviewees highlighted a national shortage of suitably experienced and skilled personnel to fill posts and expressed misgivings about “poaching” staff from other organisations. A number reported recruiting people with either little or no previous experience in resilience work. Interviewees also reflected that LRFs were all recruiting to similar posts at the same time thus exacerbating the supply problem. This, alongside the uncertainties and capacity issues thrown up by the COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult to recruit externally and in some cases to secure secondments; both because organisations were less willing to part with people and people were less confident about moving.

3.7 The recruitment processes of the public sector organisations hosting the new LRF roles were reported to have impeded progress in many cases. Multiple accounts were given of positions taking many months (in some cases up to eight months) to fill meaning that where people had been appointed this was often late in the funding period. Some LRFs were slow to agree which organisation should host new posts with “political wrangling” dragging out the process of recruitment further. While the majority of LRFs had finally managed to appoint, Phase C survey results suggest that four would not have new staff in post until 2022/23 rather than 2021/22 as planned. For some of these posts LRFs reported the intention to use the 2022-2023 funding to offer longer-term contracts.

3.8 LRFs had pursued various recruitment strategies including approaching people who had recently retired, secondments from partner agencies, taking on younger inexperienced staff and apprenticeships. Factors supporting successful appointments included the deliberate targeting of people with whom the LRF had worked with before either through external recruitment or secondment; low-cost contract extensions and internal recruitment that speeded up the recruitment process; and recruitment of individuals with specialist skills and experience that were able to “hit the ground running”. Examples of the latter included the appointment of people with expertise in website development and/or social media recruited to build or improve existing LRF websites and improve comms and, in one LRF, the appointment of an experienced VCFS coordinator tasked with advancing their community resilience work.

Progress on capability building

3.9 Delays in implementing planned projects were commonly reported by case study LRFs with many expected to run over into 2022/23. The Phase C survey returns showed a zero-forecast expenditure by end of 2021/22 on nearly a quarter (48 of 205 projects) of planned pilot funded projects suggesting that these might only get underway in 2022/23.

3.10 Reported challenges included those at the national system level most prominently recruitment and its knock-on effects on capability, the on-going necessity of dealing with COVID-19 and the impact of national restrictions. and those related to local factors including internal capacity and the nature of local partnerships.

Impact of recruitment difficulties

3.11 Challenges with recruitment had clearly had a major impact on LRFs ability to deliver against their plans for growing capability where these depended on the appointment of new staff. Even where recruitment had been successful, delays meant staff had, in many cases, not been in post long enough to begin effective delivery within the timeframe of the pilot funding. Furthermore, where new postholders were relatively inexperienced, interviewees reported that they had to spend time and energy inducting and training people thereby reducing their own capacity to advance planned work.

Local capacity and partnerships

3.12 There is a huge diversity among LRFs in terms of internal capacity to deliver on their everyday portfolio of activity, with some having only one paid member of staff while others have teams of 5 or more dedicated officers. Where internal resources were stretched some LRFs described a Catch 22 situation whereby staff were too busy to progress projects or undertake the recruitment that would make them less busy. For example, one LRF reported that between June 2021 and March 2022 the secretariat had run with only one dedicated officer, and that during this time significant resource had been tied up with dealing with multiple national and local events and emergencies holding up progress against spending proposals and recruitment. In a small number of cases LRFs felt that they had been over ambitious in setting out their intentions commenting that planned workstreams were too far-reaching and reflecting that they should have focused on a smaller number of more achievable goals.

3.13 Most LRFs reported good relationships with local partner organisations. However, for some a pre-existing challenge was the buy-in and coordination of partners described by one interviewee as “like herding cats”. Another described what he saw as a lack of both inclination and capacity amongst partners meaning he had to ‘chase them up’ on agreed actions. In some cases, difficulties in engaging partners had led to delays in agreeing or progressing planned activities either because they had not undertaken tasks that they had agreed to or because consultation and coordination had been protracted:

Dealing with COVID-19 and other events

3.14 In a small number of cases the on-going impacts of COVID-19 in some cases presented a challenge to progress against funding proposals. Interviewees reported that COVID-19 had created a back-log of work that they were still struggling to catch-up on. One LRF reported that the training events they had planned to be delivered with pilot funding had been postponed to 2022/23 due to COVID restrictions.

3.15 A number of LRFs described partners as lacking capacity to engage with the LRF due to the demands of their statutory responsibilities. Interviewees stressed that progress had been significantly held up by the necessity of dealing with emergencies and events including those that require a major response, such as the storms and flooding affecting many LRFs in 2021, and events peculiar to individual areas, for example the Commonwealth Games in the West Midlands and the G7 in Cornwall.

3.16 There was some evidence however that once the direct benefits of funding were felt, this had engendered a greater degree of engagement with the LRF and better appreciation of its value.

More complex strands of work

3.17 In some instances, LRFs felt they were working in the absence of clear government policy directives particularly on issues related to a whole of society approach to resilience. Here LRFs had grappled to come to a shared definition or vision for a whole society approach and were waiting for a policy steer before progressing this work further. In general, there was a sense that this work required a lot more scoping, consultation and collaboration between LRFs than originally anticipated.

3.18 The process of establishing a MAIC was in the early stages in those LRFs that had planned to do this, and, in some cases, there was lack of coherent vision about how it would be progressed. Some interviewees reported that their work on MAIC had been held up due delays in delivery of government guidance “we are working in a vacuum of government guidelines on MAIC” or felt that more needed to be done to promote sharing and learning between LRFs to advance this work. Incremental progress had been made by others including establishing task and finish groups to undertake scoping and consultation, data gathering and liaison with other LRFs.

3.19 Both MAIC and Whole of Society Resilience (WSR) were described as long-term big pieces of work with varying degrees of confidence expressed over how far this could or would be progressed in 2022.

3.20 Despite these challenges many LRF’s had shown considerable progress in delivering pieces of work that were time-limited or relatively short-term in nature such as programmes of training and exercises. Good progress had also been made against work that could be understood as the groundwork for more complex pieces of work or designed to have a legacy effect on the capacity of LRFs to perform and respond to future demands. Examples of the latter include need assessments, external audits and evidence reviews and workshops with local partners and community groups to inform the national policy discourse on resilience. Having an established structure and experienced people with capacity in post to advance this work were key enablers as was the ability to procure external expertise. Interviewees who had commissioned external experts commented on the value of their independent status and ability to maintain momentum on pilot-funded projects.

Outcomes, outputs and perceived benefits

3.21 Given the early stage in the implementation of many planned activities it is not surprising that pilot funding has not yet achieved the kinds of outcomes that might measure the impact of funded interventions. LRFs have, however, delivered a number of outputs (including new staff in post, training events delivered, enhanced websites, new technology, and new relationships with a wider number of VCFS organisations). It is reasonable to expect that these will deliver measurable outcomes in future – as outlined in the theory of change for the pilot funding (see Annex 2).

3.22 LRFs also highlighted that their pilot-funded projects often represented the foundation for follow-on activities that would deliver outcomes in the longer term.

3.23 Table 3.1 gives some illustrative examples of the outcomes and impacts we may expect to see based on projects that LRFs have undertaken with the pilot funding.

Table 3.1 Longer-term outcomes and impacts from pilot funded activities

| Pilot-funded activities | Outputs / immediate benefits | Follow-on activities | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scoping and development of decision-support tools (e.g., MAICs) | Intelligence on suitability / fit of different technology solutions for LRF needs Creation of new decision-support tools |

Training to support effective deployment of tools Exercises to test and improve effective use of tools |

Improved situational awareness Faster sharing of intelligence / data between partners Better information and intelligence to inform decision making during an emergency |

| Reviews of LRF structures, needs and capabilities | Reports and recommendations Increased intelligence about LRF effectiveness and best practice Identification of potential weaknesses / gaps / areas for enhancement Buy-in of local partners to address this |

Implementation of changes and improvements to LRF structures Training for staff in priority areas |

Increased capability of LRF More efficient and effective functioning of LRF |

| Engagement with local voluntary sector and community groups | Meetings / conversations / exchanges of information between LRF and local VCFS organisations Increased intelligence on needs and capabilities across local VCFS Increased awareness amongst them of the LRF New/improved relationships |

Development of joint LRF-VCFS plans and processes Provision of training for VCFS staff Provision of equipment for VCFS |

Increased capability of LRF and wider local VCFS ecosystem Increased cooperation (and less duplication of effort) between agencies and groups |

| Impact (from Pilot-funded activities) |

|---|

| Contributing to more effective responses to emergencies / incidents, such as storm response, meaning e.g. less property damage, fewer hospital admissions, transport and energy infrastructure maintained Better organisational recovery from emergencies / incidents, e.g., businesses and local services return to BAU sooner Financial savings – as a result of LRF efficiencies, reduced duplication of effort better response and recovery VCFS/wider community demonstrate improved resilience aligned to local risks |

3.24 LRFs were clearly grateful that DLUHC has allowed pilot funding to be carried over into the next financial year and were generally confident of completing planned recruitment and projects in 2022/23. Interviewees were also confident that much of the work they had set in train, would reap future benefits broadly expressed as a greater and more coordinated ability to respond effectively to emergencies and protect local communities. This was particularly the case where LRFs had established a surer footing for their secretariat or undertaken scoping exercises and needs assessments that had helped them identify gaps and plan strategically.

3.25 As well as outputs interviewees in case study LRFs reported further benefits delivered as a result of pilot funding. Where capacity had been added to the secretariat this had helped spread workload and enabled people to focus on new initiatives as well as progress things that “have been parked on the too difficult step for a long time”. Interviewees also reported that the work of their LRF had been significantly set back by COVID-19 and that pilot funding had helped them to begin the process of catching up.

3.26 There was also evidence that pilot funding had begun to deliver benefits that would contribute to the Integrated Review commitment to consider strengthening the role and responsibilities of LRFs. Case study interviewees felt that the fact that government had allocated money to them had enhanced partners’ perception of the importance of LRFs which they felt had put them in a stronger strategic position.

3.27 This was allied to an increased level of buy-in and engagement from partners also aided by the fact that funding had delivered direct benefits to them, for example through access to resources and training they had not had to pay for from their own budgets. Interviewees also stressed that more active engagement from partners had relieved the workload for some individuals and secretariats.

3.28 Some interviewees reported an increased appetite for collaboration with other LRFs and looked forward to working across a broader footprint on MAIC as well as sharing learning and access to the resources they were developing.

Chapter 4. Value for money

4.1 This chapter sets out the approach taken to assessing the value for money of the 2021/22 pilot funding for LRFs for the evaluation and then discusses the findings from this.

Assessing value for money

4.2 Assessment of value for money requires an analysis of the resources invested in the pilot funding and a comparison with the outcomes delivered. In theory, pilot funding for the LRF should deliver measurable outcomes over time. By enhancing the capacity and capability of LRFs, the funding should lead to more effective response and recovery to incidents. This should have benefits which can be valued in monetary terms, for example by reducing the costs of incident response, reducing the damage caused by incidents, and potentially by saving lives and reducing costs to the NHS and other services. This may enable quantitative analysis of the benefits relative to costs over time.

4.3 However, it is not possible to quantify or value the benefits of the programme (at least at this stage), because:

- The outcomes of pilot-funded activities have yet to be seen, and may take many years to materialise; and

- Even if outcomes could be measured, it would be difficult to separate out the effects of the pilot funding from effects of other factors and other sources of funding that LRFs have.

4.4 Therefore, at this stage, it is only possible to quantify the costs of the activities funded by the Pilots, and not the benefits. A quantitative assessment of value for money is not possible. However, a more qualitative assessment can be made, considering whether the funded activities are expected to be beneficial and proportionate to the resources used, and whether the process of allocating resources to the funded activities is conducive to delivering value for money. This is in line with HMT Magenta Book guidance, which recognises the role of theory-based methods in complex evaluations.

Costs of the funding pilot

Budget

4.5 The funding pilot had a budget of £7.5 million. Most of this was expected to contribute to the objectives of enhancing LRF capacity (£4.6 million) and capability (£2.7 million), with smaller amounts set aside for an Innovation Fund (out of scope of this evaluation), and the evaluation itself. An additional top up of £252,352 was later added to the Innovation Fund.

Table 4.1 LRF Funding Pilot Budget, 2021/22

| Objective | Funding | £ |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity | £120k per LRF x 38 | 4,560,000 |

| Capability | Variable funding x 38 | 2,660,000 |

| Innovation | £230k innovation fund to support c.2/3 projects | 230,000 * |

| Evaluation | £50k towards external evaluation support | 50,000 |

| Total | 7,500,000 |

* Innovation Fund received a later top up of an additional £252,352.

Source: DLUHC - Introduction to LRF Funding and the LRF Funding Pilot

4.6 To put this pilot funding into some context, it compares to the £11.5 million in total funding received by LRFs in 2020/21, as reported in the Phase A survey conducted by DLUHC. Of this, £3.85 million (34%) was partner funding and £7.6 million (66%) was central government incident-specific funding. Incident specific funding was exceptionally high in 2020/21 in response to COVID-19. In addition, the work of LRFs benefits from in-kind resources provided by partner organisations, including office and meeting space and IT equipment. Nonetheless, these figures show that LRF Pilot funding significantly increased the resources available to LRFs in 2021/22.

Expenditure vs Budget

4.7 LRFs were asked in the Phase C survey whether they had spent their allocation of pilot funding as originally planned, and whether they expected to have spent all the funding by the end of the 2021/22 financial year. While the majority (21 of the 38) reported they were spending the funding as planned, only six of the 38 expected to have spent all the money in the 2021/22 financial year.

Table 4.2 Responses to questions regarding expenditure compared to budget

| Question | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Have you spent LRF pilot funding as originally planned? | 21 | 17 |

| Do you expect to have spent all your pilot funding by the end of the 2021/22 financial year? | 6 | 32 |

4.8 This is consistent with the various challenges LRFs had in implementing all their planned pilot-funded activities – as reported already in Chapter 3 and DLUHC have confirmed that LRFs can carry over this funding to complete their planned work.

Expenditures on staffing

4.9 The Phase C survey returns identified pilot funding allocated to staffing totalling £3.45 million across the LRFs. This compares to the budget of £4.56 million allocated to capacity building.

Project expenditures

4.10 The Phase C survey returns identified a total of 205 projects, and financial information was provided on 187 of these. Out of the 187 projects, no expenditure was forecast for 48 projects by the end of the 2021/22 financial year. The indications in the survey responses are that planned expenditure on such projects was still expected to occur in 2022/23.

4.11 Total project expenditure to date (excluding staffing costs above) amounts to £1.8 million, with a forecast total for the year of £2.4 million.

4.12 These project expenditures compare to the Capability budget of £2.66 million. The forecast project expenditures amount to an average of £17,600 per project for which expenditure is forecast.

4.13 Table 4.3 provides an itemised breakdown of total project expenditures by the LRFs. This indicates that the largest project expenditures have been on professional fees (25%), training (19%), and other (20%, which includes additional project staffing costs not included above). Expenditures on professional and contractor fees supported a wide range of activities, including community and cyber resilience projects, risk assessments, development of websites and portals, strategic reviews, governance analyses and project management services.

Table 4.3 Itemised breakdown of forecast LRF project expenditures, 2021/22

| Item | Expenditure | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| IT hardware | £186,397.42 | 8% |

| IT Other | £223,581.83 | 9% |

| Equipment | £108,780.00 | 5% |

| Professional/ contractor fees | £599,916.99 | 25% |

| Accommodation costs | £95,524.20 | 4% |

| Training | £460,468.50 | 19% |

| Other | £470,195.57 | 20% |

| Unspecified | £263,972.23 | 11% |

| Total | £2,408,836.75 | 100% |

Displacement and additionality

4.14 A potential unintended consequence of the pilot funding, recognised from the outset, was displacement. The risk was that local partners would reduce their contributions to LRF work because of the introduction of this new central government funding. Such a reduction could take various forms – reduced partner funding for LRFs, use of LRF funding to pay for actions that would otherwise have been undertaken by local partners, or partners charging for contributions to LRF activities that they would otherwise have made free of charge. This would represent poor value for money. The pilot funding was intended to be used for capacity and capability building activities that were additional to what LRFs could have achieved without it, rather than funding LRFs to undertake actions that they would have undertaken anyway using partner contributions and resources.

4.15 There is no evidence from the evaluation to suggest displacement occurred. LRF interviewees in the case study research reported that the 2021/22 pilot funding had no impact on the level of their partner contributions and that pilot-funded activities were additional.

4.16 LRFs were also asked to report their partner contributions before, during, and after 2021/22 in the DLUHC Phase A and Phase C surveys. Gaps in the data make detailed comparisons difficult but, indicatively, total partner contributions appear stable across the three years prior to the introduction of the pilot, in 2021/22, and looking forward in 2022/23. A change in partner contributions would have also been difficult to attribute exclusively to the pilot funding in any eventuality given these are likely to affected by multiple factors.

4.17 Interviewees highlighted the value of the clear statement the DLUHC pilot funding guidance gave on the need for additionality. It stated that: “The purpose of the funding is to ensure a key focus on additionality which must not displace existing funding or fund routine core activity”. This had reportedly helped to short-circuit any queries from local partners about the pilot funding potentially replacing or reducing the need for their annual contribution in 2021/22. After the further three years of central government funding for LRFs from 2022/23 had become common knowledge, some interviewees said they could foresee potentially “tricky” future conversations with local partners about the amounts of funding they contributed to the LRF in the longer term, and therefore felt that DLUHC continuing to communicate a clear message on additionally would be valuable.

Potential future monetisable savings from pilot funding

4.18 Chapter 3 described the kinds of outputs and benefits that the pilot funding has already delivered but also that these are yet to translate into measurable (and therefore monetisable) outcomes.

4.19 Nonetheless, in the longer term the outputs that LRFs have delivered using the pilot funding are very likely to result in more effective responses to local emergencies. There is wider evidence to suggest this will equate to significant monetary savings. The pilot funding amounted to a relatively small sum (£7.5 million in 2021/22), while the costs of major incidents and responses to them are potentially very large. For example:

- The public sector costs of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic have been estimated at between £310 and £410 billion.

- Storm Desmond was estimated to inflict damage of up to £500 million in Cumbria in December 2015.

- A recent report by the LSE states that the UK Treasury currently uses £2 million as the value of a prevented fatality in economic appraisal.

4.20 From the above it is therefore clear that pilot funding would need to have only a small effect in reducing the costs of major incidents and responses to them to provide good value for money. It is also clear, however, that while government funding is distributed as small sums to all LRFs, major incidents occur sporadically in place and time. Investments in LRFs are therefore designed to deliver benefits in building resilience across all local areas, and in helping local partners to manage and respond to risks, which could otherwise result in major and uneven future costs.

Qualitative reflections on value for money

4.21 LRF representatives interviewed for the evaluation generally believed the pilot funding represented good value for money. This was primarily based on their belief in the long-term benefits of what they had used their pilot funding for, rather than any immediate efficiency gains or savings they could quantitatively evidence. There were also a minority that perceived there could have been closer scrutiny by DLUHC of how every LRF was using their pilot funding in order to provide more assurance around value for money.