Sugar ATQ: government response

Updated 16 December 2020

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

1) The UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020 and is developing its independent trade policy for the first time in nearly 50 years. The UK has always been a champion of free trade and firm believer in the vital role trade plays in boosting wealth and lifting billions of people out of poverty. The UK is shaping its own trade policy to deliver prosperity for the whole of the UK.

2) The UK government intends to achieve an FTA with the EU by December 2020 in line with the Political Declaration and is working hard to achieve that.

3) The UK Global Tariff (UKGT) schedule will apply to goods imported into the UK from 1 January 2021, at the end of the transition period, unless an exception such as a preferential arrangement or tariff suspension applies. For example, the UKGT will not apply to goods coming from developing countries that benefit under the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP), or to goods originating from countries with which the UK has negotiated a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The Northern Ireland Protocol in the Withdrawal Agreement provides for certain specific arrangements for trade with Northern Ireland.

4) As part of the new UK Global Tariff (UKGT) announced on the 19 May 2020, the government proposed an autonomous tariff rate quota (ATQ) to allow for a set volume of raw cane sugar to enter the UK tariff free, in an effort to balance support for UK producers, processers and UK consumers whilst maintaining preferential trade with developing countries.

5) Autonomous Tariff Rate Quotas (ATQs) allow imports up to a given quantity of a good to enter the UK at a lower or zero tariff during a specified period of time. Once imports exceed this given quantity, the UKGT rate would apply. ATQs are applied in line with the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) principle as part of the UK’s applied tariff regime.

6) This ATQ was announced with a quota of 260,000 tonnes of raw cane sugar to apply from 1 January 2021 as part of the UKGT. The quota would apply for 12 months, with an in-quota rate of 0% and the volume will reset each year on the 1 January, subject to any future review. Once the quota threshold is met, the out of quota tariff rate, the UKGT MFN rate of £28.00/100kg, would apply.

7) The government made clear at the time that this ATQ would be reviewed. In order to support this review, the government launched a 3-week public consultation from 14 September to 5 October 2020 on the future of this sugar ATQ. The government considered as part of this review the potential increase, maintenance, or reduction, of the volume of the ATQ, or the complete removal of the ATQ.

1.2 This report

8) This document sets out the government’s response to the public consultation and the decisions taken in relation to an ATQ on raw cane sugar. It includes the strategic approach and analysis of the results and the decision that has been made. This document should be read alongside the Summary of Responses document, which sets out a detailed breakdown of the consultation responses.

9) The consultation received domestic and international interest and expertise from a wide range of businesses and organisations. Overall, respondents broadly welcomed the opportunity to provide views on the proposed raw cane sugar ATQ. The range and depth of the responses varied, covering a range of potential impacts and considerations including: environmental standards, the interests of developing countries, the value of a level playing field for domestic competition, food security and the diversity of the UK sugar market, as well as specific information related to the respondent’s interests. Some respondents submitted additional supplementary documents to support their view, which were considered as part of the assessment process.

10) The feedback received has been carefully analysed and assessed, which has informed the government’s approach to the raw cane sugar ATQ.

11) It is important to highlight that, when considering its decision, the government considered all evidence.

1.3 Policy summary

12) In deciding the outcome of the review, the government had regard to the principles set out in the Taxation (Cross-border Trade) Act 2018 (TCTA), namely the:

- interests of consumers in the UK

- interests of producers in the UK of the goods concerned

- desire to maintain and promote the external trade of the UK

- desire to maintain and promote productivity in the UK

- extent to which the goods concerned are subject to competition

13) The government has sought to balance strategic trade objectives, such as the delivery of the UK’s trade ambitions and FTA trade agenda, whilst maintaining the government’s commitment to developing countries to reduce poverty through trade.

14) The government has carefully considered all available evidence, including the consultation responses, when making a final decision on whether to increase, maintain or reduce the volume of the raw cane sugar ATQ, or the complete removal of the ATQ.

2. Raw cane sugar ATQ – outcome

2.1 Outcome

15) The government is announcing that it will maintain an ATQ quota of 260,000 tonnes for raw cane sugar to apply from 1 January 2021. The quota will apply for 12 months, with an in-quota rate of 0% and then the volume will reset each year on the 1 January, subject to any future review. It will be allocated on first come, first served basis. Once the quota threshold is met, the out of quota tariff rate, the UKGT MFN rate of £28.00/100kg, will apply.

16) We have taken this decision based on the evidence the government had, alongside the evidence provided as part of the consultation and its analysis across Whitehall. Supporting evidence for this decision is displayed throughout this report.

2.2 Executive summary

17) In its analysis, the government has found that this ATQ will benefit the UK in relation to the 5 TCTA principles set out above. It will support UK raw cane sugar refining capacity and promote consumer choice and competition in the UK sugar market. This, in turn, will ensure the UK can act as a reliable market for raw cane sugar from developing countries and support our FTA negotiations.

18) Based on the evidence set out below, we do not expect an ATQ of 260,000 tonnes to have a material impact on the price of sugar in the UK. This is because the UK is currently a deficit market for sugar. UK prices are set by import parity from the EU where prices for refined white sugar are at or around world price levels because of the EU’s net trade position. Evidence suggest that with an ATQ of 260,000 tonnes the price of sugar would be no different compared to a situation where such an ATQ was not available, and therefore UK consumers and producers of sugar, including domestic beet sugar growers and the beet sugar refining industry, should not be impacted negatively as a result of this ATQ. Based on our expectation that an ATQ with a volume of 260,000 will not have a material impact on the price of sugar in the UK, we do not believe it will affect consumption levels but the government will monitor this. Standards will also not be compromised, as all imported food is required to meet the UK’s high food standards.

3. Analysis

3.1 UK sugar industry

19) The UK sugar market produces around 1.5 million tonnes of refined white sugar per annum and is made up of cane sugar refining and sugar beet refining. A further 500,000 tonnes or so of white sugar is imported from the EU per annum. Until recently, sugar has been a highly regulated sector within the EU, with an annual production quota of 13.5 million tonnes of sugar beet divided between 20 Member States, including the UK.

20) The UK’s sole cane sugar refinery is based in London, where raw cane sugar is imported and converted into white sugar and other products for consumption. These products are mainly sold in the UK with some exported abroad. Most of the raw cane sugar is imported from African Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries and Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and other cane producers such as Brazil (Figure 1). Due to our commitment to support developing countries, the UK provides tariff-free entry for raw cane sugar from ACP producers (those that have an Economic Partnership Agreement in place) and LDC producers (through unilateral duty-free quota-free access), although their average raw cane sugar prices are above world levels due to higher costs of production as seen in Figure 5 on page 6.

21) The UK’s sugar beet refining industry processes sugar beet that has been grown domestically centred on strong regional centres in the East of England. This sugar beet is processed in 4 factories, where sugar is produced and refined into a variety of products for consumption. These products are both sold in the UK and exported to the rest of the world.

Figure 1 - UK imports of raw cane sugar (HS code 170114, 2017-19 average)

Pie chart showing UK imports of raw cane sugar (HS code 170114, 2017-19 average)

Source: HMRC overseas trade statistics

3.2 Imports, exports and production

22) The UK is a structural net importer of sugar (Table 1). Until 2010, the UK raw sugar market was shared roughly 50-50 between the UK cane refining sector and the UK beet producing sector (Figure 2). Once this raw cane sugar has been refined into white sugar it is either consumed domestically (the majority) or exported. White sugar refined from beet or cane sugar is very similar and substitutable.

Table 1 – UK imports and exports of sugar (‘000 tonnes, refined basis, 2017-19)

| Imports and exports | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK imports: From the EU (mainly refined sugar) | 530 | 526 | 511 |

| UK imports: From rest of the world (mainly raw cane sugar for refining) | 458 | 422 | 430 |

| UK exports: To the EU | 157 | 236 | 197 |

| UK exports: To rest of the world | 46 | 125 | 68 |

| Net imports | 785 | 587 | 676 |

Source: Agriculture in the United Kingdom, 2019. Defra.

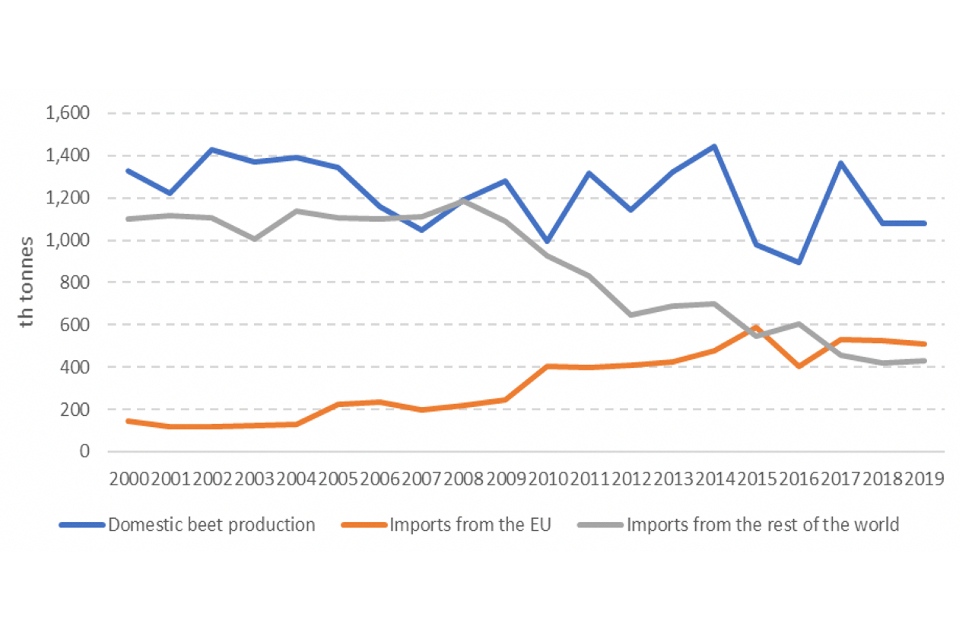

Figure 2 - UK domestic beet sugar production and imports of sugar (refined basis)

Line graph showing UK domestic beet sugar production and imports of sugar (refined basis)

Source: Agriculture in the UK, Defra - Imports from the EU are predominantly in the form of white sugar apart from imports from French overseas territories and re-exports from elsewhere; imports from the rest of the world are mainly in the form of raw cane sugar (98%).

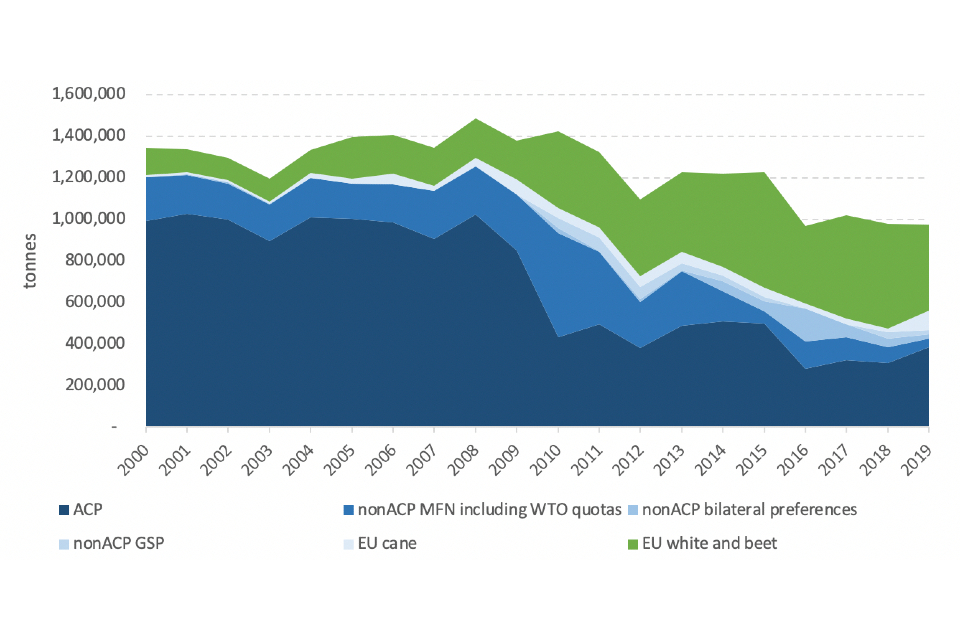

23) The UK’s imports of sugar (HS1701: cane, beet sugar and chemically pure sucrose) have decreased over the period 2000-2019, from over 1.3 million tonnes in 2000 to just under 1 million tonnes in 2019 (Figure 3). The composition of UK sugar imports has also changed significantly over the period.

Figure 3: UK imports of HS1701 (Cane, beet sugar and chemically pure sucrose) by source (tonnes)

Chart showing UK imports of HS1701 (Cane, beet sugar and chemically pure sucrose) by source (tonnes)

Source: Data from Eurostat

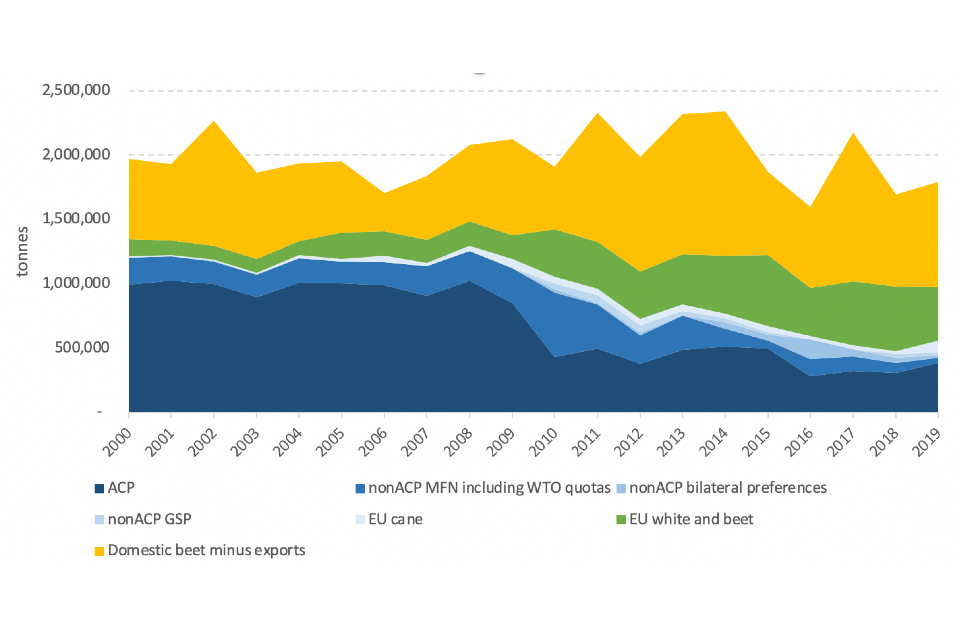

24) UK domestic beet sugar production (minus exports) has increased over the period, from just under 630,000 tonnes in 2000 to just over 815,000 tonnes[footnote 1] in 2019 (Figure 4). This is driven by a reduction in UK exports of sugar, rather than an increase in UK beet sugar production.

Figure 4: UK imports of HS1701 and domestic production of sugar (minus exports)

Chart showing UK imports of HS1701 and domestic production of sugar (minus exports)

Source: Trade values from Eurostat. Domestic production values from Agriculture in the UK.

Note: Trade data is in product weight while production data is in white equivalent.

3.3 Price

25) The price of white sugar has been on a downward trend over time, although with some fluctuations. Prior to the ending of sugar production quotas in the EU in 2017, the EU’s white sugar prices were high and generally above world prices, reaching as much as three times the level of world prices as recently as 2007. This gap was in large part due to very high external tariffs. In recent years however, EU sugar prices have been at a similar level to world prices (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Comparison of EU white price, import price of raw cane from Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (ACP) countries and world white price

Line graph showing comparison of EU white price, import price of raw cane from Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (ACP) countries and world white price

Sources: European Commission, ICE

3.4 Developing countries

26) The trends in raw cane sugar imports from ACP countries differ considerably across the ACP group. Prior to the start of the EU reforms in 2006, between 2004 and 2006, Mauritius accounted for 35% of all UK imports of sugar (by volume), Fiji (13%), Jamaica (9%), Guyana (7%) and Eswatini (5%). On average, from 2017-19, raw cane sugar from Belize accounted for 11% of UK imports of sugar, Guyana (7%), South Africa (6%), Mozambique (2%) and Fiji (5%). Supply from Mauritius fell to 3% (Figure 6).

Figure 6: UK Imports of raw sugar (HS 1701) from ACP Countries 2000-2019

Chart showing UK Imports of raw sugar (HS 1701) from ACP Countries 2000-2019

Source: HMRC

27) Looking specifically at raw cane sugar[footnote 2] import shares (Figure 7) shows that the overall share of the ACP group in UK’s imports has declined since 2006, although there have been periods of expansion from 2010-14 and 2016-18. From 94% on average from 2004-06, to a low of 34% in 2010, the share of ACP countries in total supply of raw sugar to the UK stood at 73% in 2019. The trend for the EU has been broadly comparable, although the initial decline was sharper, followed by a much shallower fall in 2010.

28) Total ACP exports to the world have followed a downward trend over the reform period, from an annual average of just over 4 million tonnes between 2004-06 to 2.8m tonnes on average from 2017-19. This demonstrates that ACP countries have not been able to divert away from the EU towards other markets when the price was not favourable, which would be evident if total ACP exports to the world remained constant over the time period in question.

Figure 7: Share of ACP countries in total imports of raw cane sugar

Line graph showing share of ACP countries in total imports of raw cane sugar

Source: UN Comtrade, data based on trade in tonnes using HS code 170111 from 1996 which is then modified as revisions to HS are made in subsequent years. This includes raw cane sugar for refining and not for refining.

29) The relative UK import shares of raw cane sugar for refining[footnote 3] from the ACP countries have changed markedly following the reforms. In the 2004-2006 period, Mauritius and Fiji accounted for the largest UK import shares in the ACP country group at 40% and 16%, respectively. Jamaica, Guyana and eSwatini also held large shares between 6-11% in the group prior to reforms. In the 2017-2019 period, Belize and Guyana accounted for the largest UK import shares in the ACP country group at 30% and 23%, respectively. Meanwhile the share from Fiji had remained at 16% and there were no imports from Mauritius in the period. The relative shares of Jamaica and eSwatini had approximately halved in the later period, while the relative shares of South Africa and Mozambique had markedly increased.

30) Analysing data trends pre and post reforms shows that several ACP producers’ reliance on the UK market has fallen dramatically. The table below shows the changes in reliance on the UK market pre reform (2004-06) and post reform (2017-19).

Table 2: Trends in selected ACP countries’ reliance on the UK market for raw cane sugar exports

| ACP producer | Reliance on the UK market for raw cane sugar exports, average 2004-06 (pre-reform) | Reliance on the UK market for raw cane sugar exports, average 2017-19 (post-reform) |

|---|---|---|

| Barbados | 100% | 14% |

| Jamaica | 91% | 54% |

| Mauritius | 90% | 16% |

| Malawi | 22% | 6% |

| Eswatini | 32% | 2% |

| Tanzania | 96% | 0% |

| Zimbabwe | 44% | 0% |

| Belize | 44% | 65% |

| Guyana | 40% | 72% |

| Mozambique | 16% | 13% |

| Fiji | 56% | 32% |

Source: UN Comtrade, data based on trade in tonnes using HS code 170111 from 1996 which is then modified as revisions to HS are made in subsequent years. This includes raw cane sugar for refining and not for refining. For data availability reasons and for consistency with other analysis in this document the figures are based on mirror import flows. The figures would differ if export data was used, although the trade flow patterns remain largely unchanged.

31) For countries in which the reliance on the UK market has reduced, alternative markets have offered better returns. The US and regional markets grew in importance for Barbados, Jamaica, Mauritius and Malawi, whilst the UK diminished. For Belize and Guyana their reliance on the UK market has increased and although Fiji’s reliance on the UK market has fallen by over 20 percentage points over the period in question, it is still significant and represents the largest recipient of Fiji sugar, followed by Spain and the US[footnote 4].

4. Conclusions

32) This report will now outline the government’s analysis in the context of the supporting evidence provided above, addressing the results of the public consultation with regard to the five TCTA principles defined in the policy summary on page 2, namely: the interests of consumers and producers, competition and the desire to promote productivity and external trade. The impact to consumers and consideration of consumer interests can be found throughout this analysis. It is important to highlight that, when considering its decision, the government considered all evidence.

4.1 UK producers and competition

33) Some public consultation respondents asserted that the introduction of an ATQ on raw cane sugar would lead to domestic beet sugar producers and beet sugar refiners having to reduce their prices in order to compete with imports.

34) Based on the evidence provided earlier in this report, the ATQ volume of 260,000 should not have a material impact on prices. This is because the UK is currently a deficit market for sugar and UK prices are set by import parity from the most competitive source of imports. This is currently the EU, due to its proximity and its near-world price refined white sugar. n ATQ of 260,000 tonnes would constitute a lower volume than the UK’s current white sugar imports from the EU (around 500,000 tonnes in recent years) and we therefore expect our ATQ will not tip the UK into a surplus supply of sugar.

35) The government’s intention is to achieve a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU, and so the price of refined white sugar is not expected to change substantially in the medium term since the marginal supplier of refined white sugar is expected to continue to be the EU. This ATQ of 260,000 tonnes is not large enough to substantially change market conditions in the UK and based on the evidence the government has, we do not expect consumer prices to be impacted.

36) Some public consultation respondents expressed concerns that an ATQ would undercut UK sugar beet growers and UK beet sugar refiners as the increased competition would harm the viability of the industry.

37) Evidence suggests that a diverse UK sugar market, and the introduction of an ATQ, will not undercut domestic production of sugar, but will, in fact, return a more level playing field to the UK sugar market, as was the case before the 2017 sugar reform, where the removal of sugar quotas in 2017 left UK raw cane sugar refiners’ share of the UK market at around 20%. We expect domestic beet production to stay at 50-55% of the market share, with the ATQ of 260,000 tonnes set to displace EU white sugar in favour of raw cane sugar. The increase in EU domestic production of beet sugar following quota abolition, combined with the subsequent fall in the EU white sugar price without any commensurate reduction in the cane import duty, significantly reduced the quantity of raw cane sugar imports on the EU market. The relatively low white sugar price in the EU, together with high EU external tariffs on imports of raw cane sugar– in addition to the high production costs of raw cane sugar in ACP countries – results in little raw cane sugar entering the UK competitively.

38) Some public consultation respondents suggested that protecting the UK cane sugar refining industry is important to the UK’s food security, and that a diverse sugar market helps to allocate resources more efficiently. The government notes the need to ensure a viable sugar refining industry within the UK market and this ATQ helps to maintain a diverse sugar market. This is in the interests of UK consumers, while providing purchasing options and competition.

39) The UK currently has a large sugar deficit, meaning that it consumes more than it produces, so it is important that a diversity of supply is available. The UK’s refined white sugar consumption is around 1.7 million tonnes of refined sugar per annum. UK beet sugar refiners produce around 1.1 million tonnes per annum, with raw cane sugar refiners producing around 400,000 tonnes. Each year the UK also imports around 500,000 tonnes of refined sugar from the EU, which is produced primarily from the EU sugar beet industry. This provides a total supply to the UK of around 2 million tonnes a year of refined sugar. However, the UK also exports around 275,000 tonnes of the refined sugar it produces each year, primarily to the EU. It is therefore important for the UK to have a diverse sugar market of beet and cane sugar in order to cover this sugar deficit and any external factors that may impact the supply of either source.

4.2 Developing countries

40) As shown in the evidence provided above, the UK imported 94% of its sugar from African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries, on average, between 2004-2006, which declined to 73% in 2019. Analysing data trends shows that ACP producers’ reliance on the UK market has fallen dramatically for countries like Jamaica, Barbados and Mauritius, however several other countries are still significantly reliant on the UK market, such as Belize and Guyana.

41) Some respondents suggested that any sugar imported at world prices under an ATQ would offset the fixed unit cost of producing sugar from ACP countries, which is historically above global prices. They stated that ACP countries produce a different quality of sugar that importing companies require for non-white sugar products. Raw cane sugar that is required for this cannot be sourced from other sugar exporters like Australia and Brazil.

42) Whilst raw cane sugar continues to be imported from ACP countries tariff free, the higher costs of production mean it cannot compete, in terms of cost to the importer, against European beet growers and refiners.

43) At the end of the Transition Period the UK will apply the UKGT. Without further intervention, this would mean that the UK sugar cane refining sector will continue to have duty-free access to raw cane sugar from ACP countries that the UK has signed continuity agreements with, and from LDCs through the UK’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences. However, the price of raw cane sugar from ACP and LDCs is relatively high compared to other sources due to higher costs of production, and the sector will face high tariffs on raw cane sugar from countries that do not have a trade agreement or preferential access. The inability of the cane refining sector in the UK to source competitively priced raw cane sugar could undermine its long-term viability and its role as a market for raw sugar cane exports from developing countries.

44) Several consultation respondents highlighted their concern that any ATQ would lead to decreased demand for ACP country sugar. Whilst the government understands that there is a risk that imports could be diverted away from ACP countries, the government anticipates that the volume of 260,000 tonnes would still allow the UK cane refining sector companies that are currently refining raw cane sugar the ability to continue to import ACP sugar, but also additional raw cane sugar from non-ACP countries to remain competitive. An ATQ of 260,000 tonnes of raw cane sugar, on top of current levels of imports from ACP countries, would still leave the UK cane sector operating at below full capacity. The inability of the cane refining sector in the UK to source some competitively priced raw cane sugar could undermine its long-term viability and its role as a market for raw sugar cane exports from developing countries.

45) The presence of a viable raw cane sugar refiner is necessary to ensure the UK remains a viable export market for developing countries’ raw cane sugar. An ATQ will help to ensure the viability of the UK’s raw cane sugar refining industry and ensure it remains a viable export market for these ACP countries. In the absence of domestic cane refining capacity, the UK would be limited in its ability to import raw cane sugar. Accordingly, the presence of at least some raw cane refining capacity in the UK is necessary to import raw cane sugar from ACP countries and LDCs, thereby maintaining the government’s commitment to reduce poverty through trade. It has become apparent through the consultation responses that an ATQ could encourage further diversity of the UK sugar industry, by encouraging other companies to consider entering the raw cane sugar refining market.

46) Overall, the government believes that the ATQ will not have a negative impact on external trade regarding developing countries. This is because our ATQ will help the viability of the UK’s raw cane sugar refining industry and provide a desirable export market for ACP sugar, while limiting the competition faced by ACP producers on their exports of raw cane sugar to the UK, so preserving their preferential access.

4.3 Negotiating position

47) Some respondents to the consultation suggested that any liberalisation of the market should be done through Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with new trading partners and not through an ATQ, as a tariff-free quota on raw cane sugar would undermine our future negotiating position.

48) Whilst the government recognises that sugar is an important domestic sector for trade negotiations, an ATQ of 260,000 tonnes, which lasts for 12 months subject to any future review, should not diminish our negotiating position. Future trading partners will want to secure permanent, preferential access for their raw cane sugar sectors through an FTA.

49) This would eliminate the need for them to compete with other sugar exporting nations as they would under an ATQ. The autonomous nature of this mechanism will also incentivise FTA partners to seek to secure a more reliable and permanent preference.

50) The government remains steadfast on the view that an ATQ is the most appropriate mechanism available to HMG at this time. Any ATQ on raw cane sugar would be open to all global suppliers. As such, we do not believe our ATQ of 260,000 would have a negative impact on our negotiating position, given this volume only represents a proportion of the UK’s cane refining capacity.

51) Furthermore, for the UK to offer a viable market for sugar imports, it will need some raw cane sugar refining capacity. Responses suggest that an ATQ of 260,000 provides opportunity for investment into the UK’s raw cane sugar refining industry, therefore making the UK sugar market more desirable for raw cane sugar exports from future trading partners.

52) Overall, the government believes that an ATQ will not have a negative influence on our external trade agenda. This is because an ATQ with the volume of 260,000 tonnes is not a permanent solution to securing preferential market access with countries which we might negotiate FTAs, as the ATQ will reset after 12 months subject to any future review, and indeed, is not large enough to be an alternative to access gained through an FTA. The ATQ will also ensure the UK can act as a reliable market for raw cane sugar from developing countries and support our FTA negotiations.

4.4 Health

53) A few respondents to the public consultation raised concerns that a raw cane sugar ATQ could lead to a reduction of sugar prices due to an increase in supply. They argued public health would be negatively impacted due to increased consumption of sugar because of this reduction of price.

54) Based on the evidence set out at the beginning of this report, the government does not expect an ATQ of 260,000 for raw cane sugar to have a material impact on the price of refined white sugar for consumers. However we will monitor this. This is our expectation because the UK is a net importer of white sugar (a deficit market for sugar). Therefore, domestic prices will be driven by import parity (cost of imports at origin plus inward transport costs) from the most competitive source of imports. The EU has near-world prices on refined white sugar (due to being a surplus market) and high Common External Tariffs (CET) on white sugar for MFN trading partners. Whilst we continue to import the balance of our requirements for refined white sugar from the EU, the UK’s sugar price is unlikely to be affected, relative to the counter-factual.

55) Based on our expectation that an ATQ with a volume of 260,000 will not have a material impact on the price of sugar in the UK, we do not believe it will affect consumption levels but we will continue to monitor this.

4.5 Standards

56) Several respondents to the public consultation suggested that any raw cane sugar coming into the UK should have the same standards as sugar that is produced in the UK. They also argued that any raw cane sugar being imported into the UK should only be treated by pesticides that are legal in the UK.

57) The government has always been clear that we will not compromise on our food safety standards. All food in the UK market, irrespective of origin, needs to meet the prescribed Maximum Residue Levels for all active substances. As a result, any raw cane sugar regardless of whether it is imported under this ATQ, through a trade agreement or via the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) from developing countries will need to meet this standard. Raw cane is produced in countries that have markedly different climates and environmental conditions to the UK. As a result, raw cane sugar producers will likely use different pesticides from those used to grow sugar beet in the UK. This use of pesticides does not pose an additional risk to UK consumers.

58) We will maintain our high human health and environmental standards when operating our own independent pesticides regulatory regime after the Transition Period. We will ensure decisions on the use of pesticides are based on careful scientific assessment and will not authorise pesticides that may carry unacceptable risks. The statutory requirements of the EU regime on standards of protection will be carried across unchanged into domestic law.

59) Maximum Residue Levels (MRLs) help to ensure pesticide residues in or on food and animal feed are both safe and legally permissible and that Plant Protection Product (PPP) usage is based on good agricultural practice. An import tolerance is an MRL that is set based on PPP uses registered in non-EU countries. An import tolerance application facilitates international trade by allowing the importation of food products that have been treated with pesticides containing active substances that have not been approved for that use domestically. Import tolerances will be granted following an application if regulators are content that the residues are not a risk to consumer health.

60) An ATQ provides the opportunity for UK refineries to purchase their sugar from sources that adhere to assurance schemes are currently inaccessible due to high tariffs. For example, Bonsucro-standard cane, which requires producers to meet environmental and sustainability criteria, will also benefit from tariff reductions.

61) The government remains committed to upholding the highest environmental and ethical standards. Implementing this ATQ does not lower or change standards that are required today for imported sugar cane. Imports under it will have to meet MRL requirements as with all other imports of plants and plant products as they do now.

5. Wider policy considerations

5.1 ATQ administration

62) Some public consultation respondents argued that an ATQ should be administered via a licencing system, to ensure transparency, regulatory standards, and to prevent the ATQ from being dominated by large companies.

63) The government believes there is no need for the ATQ to be administered via a licence and therefore it will be allocated on a first come, first served basis. We agree with respondents who argued that a licensing system would impose an administrative burden on the ATQ. This would create a non-tariff barrier to access the UK market. A licencing system could also encourage speculators in the market which could lead to an inefficient allocation of the quota.

6. Next steps

64) The government will continue to ensure that future trade policy works for the whole of the UK, Parliament, local government, business, trade unions, civil society and the public from every part of the UK will continue to have the opportunity to engage and contribute. This will be delivered by:

- continued engagement with the public, to inform our overall approach and the development of our policy objectives

- engagement outreach events across the United Kingdom

65) The UK Global Tariff schedule was announced on 19 May 2020. For the remainder of the transition period the UK will continue to apply the Common External Tariff on an MFN basis to imported goods. The UK Global Tariff, which includes this raw cane sugar ATQ of 260,000 tonnes, will be operational at the UK border on 1 January 2021. The complete UK Global Tariff schedule can be found on GOV.UK.

6.1 Review mechanism

66) In January 2022, and each year onwards, the quota will reset to the 260,000 tonnes volume, subject to any future review.

-

This figure underestimates the amount of UK beet on the domestic market because some of the UK’s exports will be from cane sugar or re-exports. This is particularly true at the beginning of the period where cane production in the UK was higher. ↩

-

Using HS code 170111 from 1996 which is then modified as revisions to HS are made in subsequent years. This includes raw cane sugar for refining and not for refining. Data sourced from UN Comtrade: WITS. ↩

-

HS codes 17011110, 17011310 and 17011410. Data source: HMRC. ↩

-

Source: UN Comtrade, using average trade flows (in tonnes) across 2017-2019 ↩