OIM Annual Report on the Operation of the Internal Market 2022-23

Published 22 March 2023

Chair’s Foreword

I was delighted to be appointed as OIM Chair in April 2022, and over the last year have had the pleasure of representing the OIM, speaking to a variety of organisations both to hear their views and to spread the word on our role.

Trading between the nations of the UK is a crucial part of our economy, and it is vital that the operation of our internal market remains effective. The OIM has the important role of helping to facilitate this. We do this by providing reports to the governments on the potential impacts of specific regulations, as well as by providing independent reports on the regime of the internal market and on the operation of the internal market, which is the focus of this document – our first annual report.

We recognise the importance of gathering evidence from a wide range of stakeholders to inform our work, and I have been pleased to play a part in this. I have held meetings with ministers and officials from all 4 governments of the UK. I have also engaged with business groups and attended several roundtables with businesses, trade associations, academics, researchers, think tanks and members of the legal profession, to hear first-hand their views about the UK internal market.

Alongside this annual report, we have published our first periodic report on the UK internal market regime, which provides the first detailed analysis of how the infrastructure set out in the UK Internal Market Act and those in Common Framework agreements are supporting the internal market. We have also published our ‘Data Strategy Road Map’ which sets out the projects being undertaken to fill the gaps we have identified in intra-UK trade data, leading to much improved analysis in the future.

I am also very pleased that, last month, we published our first report on a proposed ban concerning peat in response to a request to look at how proposed peat legislation might impact on that market within the UK.

As this is our first statutory annual report, our appreciation of the key factors underpinning the effective operation of the UK internal market is likely to evolve over time. We welcome feedback and input from interested stakeholders on this report.

Lastly, I would like to extend my warmest thanks both to the staff at the OIM and in the wider CMA for all their efforts and would also like to thank the 4 governments of the UK for their constructive and open engagement, at Ministerial and official level, as well as the businesses, trade associations, policy and legal professionals and academics who took part in our roundtables and qualitative research.

Murdoch MacLennan, Chair of the Office for the Internal Market Panel

Executive Summary

This report is the Office for the Internal Market’s (OIM) first annual report on the operation of the internal market. It covers the period from April 2022 to March 2023 and builds on our ‘Overview of the UK Internal Market’ report published in March 2022. We are publishing this report alongside our first statutory periodic report on the UK internal market regime.

Our role is to assist the 4 governments across the UK by applying economic and other technical expertise to support the effective operation of the UK internal market. We have an advisory, not a decision-making role. Given our focus on the economic impacts of different regulatory choices across the UK nations, we recognise that the findings and issues raised in our reports are likely to constitute 1 consideration, among others, when a government or legislature determines its preferred policy and regulatory approaches.

We have prepared this report to meet the requirement under section 33(5) of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (the Act) that we prepare a report no later than 31 March 2023 (and at least once in every relevant 12-month period) on the operation of the internal market in the UK and on developments as to the effectiveness of the operation of that market.

Since the United Kingdom left the European Union (EU), significant powers have returned to the UK Government and to the Devolved Governments of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, increasing the autonomy for these governments to shape their own regulations and also therefore the possibility of regulatory differences emerging between the 4 nations of the UK post-Brexit.

In preparing this report, we gathered evidence from a range of sources, including statistics from the Devolved Governments, from the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE) and from the Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS) which is conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). We held roundtable discussions with a variety of stakeholders, such as businesses and trade associations, academics, members of the policy community, and legal professionals.

We commissioned qualitative research from an independent consultancy, Thinks Insights & Strategy (TIS), which obtained views of businesses based in all UK nations and who trade across the UK. We also monitored UK regulatory developments and reviewed publicly available information relevant to the operation of the UK internal market, and used information provided by businesses and other stakeholders through the OIM’s webform.

In preparing this report, we heard from a number of stakeholders who raised issues associated with the Northern Ireland Protocol (the Protocol). Under the Act, our remit does not extend to the Protocol, and so we are unable to undertake a review of the Protocol or of legislation implementing it. For the purposes of our reporting functions, Northern Ireland is part of the UK internal market, and this report refers to the Protocol where appropriate.[footnote 1]

We found that the available data on intra-UK trade was limited, with long lags before figures were available for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and no data at all for England. There are inconsistencies in the way data is collected and produced which hampered comparability. However, some clear indications emerged. We found that intra-UK trade was very important to the UK nations, representing around 45% to 65% of the external sales and purchases of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, although less so for England as a result of the relative size of its economy.

Given the limitations in the data currently available, we have published a ‘Data Strategy Road Map’ alongside this report which sets out initiatives to improve intra-UK trade data being undertaken by the ONS, the Devolved Governments and others. These projects aim to improve significantly what can be known and monitored of how the UK’s internal market is working, by improving the available data.

We found from the BICS that the majority of businesses that trade within the UK do not experience challenges when selling to other UK nations, and less than 1 in 10 of firms that engaged in trade cited challenges due to differences in rules and regulations. Our qualitative research also found that few businesses had encountered challenges in trading with other UK nations.

Businesses were also largely unaware of the potential for regulatory differences between UK nations to arise. When the potential for such changes was raised with the participants in our qualitative research and at our roundtables, they considered that it could raise challenges and that consistency was preferable. Despite this, the businesses we heard from mostly said they would be able to adapt to regulatory difference, although our evidence suggests that some smaller firms may find adaptation more challenging due to more limited resources and a lack of experience in adapting to regulations.

Our report covers a number of policy areas potentially impacting the internal market including: the proposed ban on the sale of horticultural peat; the development of Deposit Return Schemes; government prohibitions on single-use plastic products; proposed changes to genetic technologies; food and drink which is high in fat, salt and sugar; and glue traps and snares. Looking forward, we also identify some potential areas of note for the future including the impact of the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill 2022.

In reviewing these regulatory developments, we have identified common themes in relation to different regulations between the nations which we hope will assist policymakers when considering the potential impacts of future regulatory change on the UK internal market.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, where businesses express a concern about a regulatory development this is often because they expect compliance to entail additional costs or because they expect that a development will place some businesses at a disadvantage relative to others. We heard from businesses who were concerned that similar policy goals across the nations may be introduced at different speeds and/or in different forms. We also found a general lack of awareness of the Act (including the Market Access Principles) and noted some uncertainty as to the potential effects of the Act on specific regulations.

We also heard from governments, businesses and third sector organisations that intergovernmental discussion at an early stage of policy development (for example, via a relevant Common Framework) could help enable a coordinated approach across nations and/or ensure that differences between the nations’ approaches are managed well. We will report on the impact of regulatory developments on the effective operation of the UK internal market in subsequent annual reports.

The Report’s purpose and context

Introduction

The Office for the Internal Market (OIM) was launched in September 2021 to provide independent advice, monitoring and reporting to the 4 governments of the UK in support of the effective operation of the UK internal market.

This report is our first statutory report covering the operation of the UK internal market and developments as to its effectiveness which has been prepared to meet our reporting requirements under s.33(5) of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (the Act).

Chapter 1 provides background to the OIM and the legislation behind it. It covers our general functions and describes the statutory purpose of this report. It includes a discussion of what we mean by the effective operation of the internal market and concludes with a summary of our evidence gathering.

Chapter 2 provides an assessment of the available economic data on trade flows between the UK nations, in addition to an analysis of the experiences and views of businesses of trading across the UK including a discussion of their current knowledge and perception of the internal market and the Market Access Principles (MAPs).

Chapter 3 discusses some current and upcoming regulatory developments that may affect the UK internal market. It summarises our findings on the proposed ban on the horticultural use of peat. It then provides brief background and a summary of stakeholder commentary for various important regulatory developments we have observed in the past 12 months and identifies potential areas of note for the future. It concludes by setting out a number of findings which draw out common themes and examine some of the practical implications of differences of approach between the nations.

Background to the Act

Since the United Kingdom left the European Union (EU), significant powers have returned to the UK Government and to the Devolved Governments of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, increasing the autonomy for these governments to shape their own regulations and also therefore the possibility of regulatory differences emerging between the 4 nations of the UK post-Brexit.[footnote 2]

Given this potential for increased regulatory differences between the UK nations, the Act was introduced with the aim of ensuring that the UK internal market continues to function as effectively as possible.[footnote 3]

In preparing this report, we heard from a number of stakeholders who raised issues associated with the Northern Ireland Protocol (the Protocol). Under the Act, our remit does not extend to the Protocol, and so we are unable to undertake a review of the Protocol or of legislation implementing it.[footnote 4] For the purposes of our reporting functions, Northern Ireland is part of the UK internal market[footnote 5] and this report refers to the Protocol where appropriate. This report also includes an analysis of trade flows between the nations including Northern Ireland (chapter 2), as well as noting where regulations in Northern Ireland are required to remain aligned to the EU as a result of the Protocol (chapter 3).

Parts 1 to 3 of the Act

Part 1 of the Act establishes the MAPs of mutual recognition and non-discrimination in relation to goods. The mutual recognition principle means that if goods meet the regulatory requirements[footnote 6] for their sale in 1 part of the UK[footnote 7], those goods can be sold in any other part of the UK without having to meet any different requirements which are applicable there.[footnote 8] The non-discrimination principle means that direct or indirect discrimination based on differential treatment of local and incoming goods is prohibited.[footnote 9]

Part 2 of the Act establishes the MAPs of mutual recognition and non-discrimination in relation to services. For service providers, the Act makes provisions for the mutual recognition of ‘authorisation requirements.’[footnote 10] This allows for a service provider who is authorised by a regulator to provide a particular service in 1 part of the UK, to rely upon that authorisation to provide those services in other parts of the UK.[footnote 11] The non-discrimination principle for service providers means that where some types of regulations imposed in 1 part of the UK discriminate against service providers from another part of the UK, these discriminatory parts of the regulation will be disregarded and have no effect.[footnote 12]

Part 3 of the Act introduces a system for the recognition of professional qualifications across the UK. The Act sets out the ‘automatic recognition principle’ which states that a UK resident qualified in 1 part of the UK is automatically treated as qualified in respect of that profession in another part of the UK.[footnote 13] It also makes it unlawful, in certain circumstances, for 1 nation to regulate in a way that gives less favourable treatment to qualified UK residents from other UK nations than that afforded to its own.[footnote 14]

Common Frameworks

Another key part of arrangements in relation to the operation of the UK internal market is the scope for Common Frameworks. The Act defines a ‘Common Framework agreement’ as a consensus between a Minister of the Crown and 1 or more of the Devolved Governments as to how devolved or transferred matters previously governed by EU law are to be regulated after 31 December 2020. Common Framework agreements typically set out intergovernmental meeting and decision-making structures, agreed principles for ways of working and a dispute resolution process.

Since 2017, the UK Government and the Devolved Governments have been working together to develop Common Frameworks in some areas that were previously governed by EU Law. The majority of these Common Framework agreements have been drafted and published and are operating in provisional form. One has been finalised following parliamentary scrutiny in the 4 legislatures.

In this report, we consider Common Frameworks where relevant in chapter 3 below; a fuller description and analysis of Common Frameworks is provided in chapter 3 of our periodic report on the UK internal market regime.

General functions of the OIM

Our statutory objective is to support, through the application of economic and technical expertise, the effective operation of the UK internal market, with particular reference to the purposes of Parts 1, 2 and 3 of the Act.[footnote 15]

Our main functions broadly fall into 2 main categories:

-

providing reports (or advice, as applicable) on specific regulatory provisions on the request of a Relevant National Authority (RNA)[footnote 16], [footnote 17]

-

monitoring and reporting on the operation of the UK internal market – for example, discretionary reviews and reports[footnote 18] and annual and periodic statutory reports[footnote 19]

-

in fulfilling our functions, our approach is to ensure that we demonstrate transparency, independence and analytical rigour. We are required by the Act to act even-handedly in respect of the 4 RNAs[footnote 20]

-

further information on our role and powers can be found in our Operational Guidance published in September 2021 (OIM1)[footnote 21]

The focus of this report

This report forms part of our monitoring and reporting functions. More specifically, this report has been prepared to discharge the requirement that an annual report be prepared by 31 March 2023 on:

-

the operation of the internal market in the UK

-

developments as to the effectiveness of the operation of that market[footnote 22]

The report builds on our first published report, ‘Overview of the UK Internal Market’ published in March 2022[footnote 23], which provided a review of intra-UK trade data, presented findings from a business survey and identified some areas where regulatory differences seemed most likely to arise across the UK nations.

The OIM’s role

We aim to assist the 4 governments across the UK by applying economic and other technical expertise to support the effective operation of the UK internal market. We have an advisory, not a decision-making role. Given our focus on the economic impacts of different regulatory choices across the UK nations, we recognise that the findings and issues raised in our reports are likely to constitute 1 consideration, among others, when a government or legislature determines its preferred policy and regulatory approaches.

This report focuses on the effective operation of the UK internal market in relation to goods, services and professional qualifications. Our role does not extend to considering other differences which may arise between the UK nations (for example, in relation to matters of public policy), nor to matters of broader economic policy. In considering our reports, it is also important to recognise the policy context in which governments act. Governments may make policy interventions for a number of reasons which may, in turn, lead to differences in regulation emerging between the UK nations. These actions may include interventions to address a specific issue in relation to the circumstances of that nation (such as to address particular health needs of the local population), or to take action to address broader strategic priorities (for example, to address environmental priorities).

Differences in regulation can also lead to valuable innovation in policy making – as noted in the Resources and Waste Provisional Common Framework, ‘[t]he ability for divergence is retained in line with the devolution settlements, recognising that divergence can provide key benefits such as driving higher standards and generating innovation and improved standards, while taking account of its impact on the functioning of the UK internal market.’[footnote 24] For example, the Scottish Government was the first to introduce a smoking ban in the UK, and the Welsh Government was the first to introduce a charge for single use plastic bags. These successful policies gave opportunities for the other UK nations to see the policies in action before making their own decisions to enact similar legislation.[footnote 25]

As with all our work, our focus on economic factors needs to be considered within the context of the public policy decisions of governments, including the manner in which governments consider the (often unquantifiable) costs and benefits of policy choices.

The effective operation of the internal market

In this section, we set out some of the economic factors relevant to our role to report on the effective operation of the UK internal market.

Our operational guidance, published at the time we were launched, sets out the need for us to acknowledge ‘the balance to be struck between frictionless trade and devolved policy autonomy.’[footnote 26] It also states that the ‘effective operation’ of the UK internal market includes the following:

-

‘minimised barriers to trade, investment, and the movement of labour between all the nations of the UK (subject to relevant exclusions in the Act)

-

ensuring that businesses or consumers in 1 of the UK nations are not favoured over those in other UK nations

-

effective management of regulatory divergence (including through the use of Common Framework agreements)’

These considerations provide a useful starting point when identifying the characteristics of an effectively operating UK internal market.

The Act provides a non-exhaustive list of factors which may be considered by us when monitoring and reporting on the effective operation of the UK internal market. Section 33(8) of the Act provides, ‘So far as a report under … [section 33] is concerned with the effective operation of the internal market in the United Kingdom, the report may consider (among other things) –

-

developments in the operation of the internal market, for example as regards –

-

competition

-

access to goods or services

-

volumes of trade (or of trade in any direction) between participants in different parts of the United Kingdom

-

-

the practical implications of differences of approach embodied in regulatory provisions […] that apply to different parts of the United Kingdom.’

The potential relevance of the factors listed as ‘developments in the operation of the internal market’ can be summarised as follows:[footnote 27]

-

competition: Where businesses in the UK are able to trade across UK nations, this is likely to lead to some businesses in each nation competing with those from other nations. This will increase competition which is likely to lead to improved outcomes, such as lower prices or better products and services, for consumers

-

access to goods or services: Similarly, trade across UK nations can result in consumers having a greater choice of goods and services by making available products or brands which are not produced within their ’home’ nation

-

volumes of trade: Evidence of high volumes of trade across the UK nations may suggest that barriers to trade are surmountable; and increases in trade may indicate that consumers could be benefiting from increased competition and improved access to goods and services

-

differences of approach: The practical implications of differences of approach embodied in regulatory provisions are important as the details of how regulations work can have a significant impact on firms and individual markets

There are other ways that intra-UK trade may improve efficiency in addition to the stimulus from increased competition. A larger overall market may enable businesses to benefit from economies of scale. Trade may also enable each nation to focus on the goods and services which it is most efficient at producing, leading to a higher output from the same resources for the UK overall. These efficiency benefits may result in higher growth and productivity.

The indicators and factors which we look at are likely to vary depending on the specific issue we are analysing – for example, in relation to a request for a report under ss34 to 36 of the Act, depending on the regulatory provision under consideration, we may focus more on impacts on competition (for example, between businesses) as opposed to other factors (for example, intra-UK trade data) to advise governments most effectively.

We recognise that the ‘UK internal market’ is, in reality, made up of interactions between a range of buyers and sellers across many markets, each with their own characteristics. While measures such as the volume of trade, GDP growth or productivity can give some indication of the effectiveness of the internal market overall or in relation to broad sectors, data is not currently typically available to assess the effectiveness of individual markets, either in particular sectors or regions.

In this first annual report, we have focussed primarily on data on trade volumes at the national level as well as an analysis of differences in regulatory approach to report on the effective operation of the internal market.

Going forward, we intend to use data on volumes of intra-UK trade as a priority indicator when assessing the effective operation of the UK internal market, at the macro level. The OIM Data Strategy Roadmap, which we are publishing alongside this report, sets out current initiatives to improve intra-UK trade data being undertaken by the ONS, the Devolved Governments and others. These projects aim to resolve some of the limitations in the available data, including difficulty comparing the statistics for each UK nation due to methodological differences. The Roadmap forms part of an OIM Data Strategy that seeks, through engagement and collaboration with partners, to achieve a significant improvement in what can be known and monitored of how the UK’s internal market is working. While intra-UK trade has been the key focus of the Data Strategy to date, over time we will look to expand it to cover other relevant indicators.

Evidence gathering

This report draws on a wide range of evidence including statistics from the Scottish Government, Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA)[footnote 28], as well as research initiatives on the value of intra-UK trade purchases (imports) and sales (exports) to the other UK nations. We draw on data from the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE) as well as data from the Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS) which is conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). More detail on the trade data we have used is provided in Appendix A to this report.

We also commissioned qualitative research that was carried out by an independent consultancy, Thinks Insights & Strategy (TIS). This research gathered views from businesses based in all UK nations, in different sectors, and of varying size who trade across internal UK borders. The research covered the importance of intra-UK trade to their business, their experiences of adapting to regulatory difference, and how they might react to hypothetical examples of it and covered their awareness of the MAPs. Findings from this research are published alongside this report.[footnote 29]

In addition, we gathered information from 4 roundtable discussions with a variety of stakeholders. The focus of the discussions with businesses and trade associations was on identifying sectors that are seeing, or are likely to see, regulatory divergence and the implications of this on businesses. In our roundtables with academics, members of the policy community and legal professionals, there was a greater focus on the MAPs and Common Frameworks and their implications.

We have reviewed publicly available information in relation to regulatory developments which may impact on the effective operation of the internal market. Where relevant, we have also used information provided by businesses and other stakeholders via the OIM’s webform[footnote 30] on how the UK internal market is working. In addition, we undertook a desktop review of published documents and research.

We also engaged with the governments on various matters connected with the internal market. We are grateful for the inputs of the governments and of all the stakeholders with whom we have engaged in preparing this report.

Operation of the internal market[footnote 31]

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the evidence on the operation of the internal market. As discussed in chapter 1, there are a variety of factors that can be considered when thinking about the effective operation of the internal market, but as noted in paragraph 1.33 above, this report focuses on trade volumes. We anticipate this this will remain an important indicator, although we may expand our Data Strategy to consider other indicators in future.

This chapter draws upon a number of sources, as outlined in chapter 1. Several of these sources have not published updated releases since our Overview of the UK internal market report;[footnote 32] where that is the case we have included material from the Overview report so that this report is a standalone document.

This chapter firstly analyses the trade that takes place within the UK, both in terms of the volume traded and who trades between UK nations. Although the data that is available on intra-UK trade is limited, this analysis sheds some light on the differences in trading patterns between the UK nations, and between businesses of different sizes and in different sectors. This chapter then discusses businesses’ experiences of intra-UK trade, drawing on the qualitative research commissioned by us, and information gathered from our roundtable discussions.

What trade takes place in the UK internal market?

This section outlines information we have reviewed about trade across the UK internal market. Data on intra-UK trade is limited, with only 3 of the 4 UK nations (Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) publishing dedicated statistics on intra-UK trade which gather information on the value of purchases (imports) and sales (exports) to the other UK nations. However, lags in the publication of the datasets differ, as do their respective methodologies for data collection and production, which hampers comparability and estimates of total intra-UK trade. Additional explanation of the differences in approach taken in different nations is detailed in Appendix A. Research initiatives have also attempted to estimate the volumes of trade flows within the UK, and questions on the proportion and types of businesses that trade within the UK are included in the Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS), a fortnightly business survey conducted by the ONS. By using a combination of these data sources, this section examines the volume of intra-UK trade and then analyses who trades within the UK.

Volume of intra-UK trade

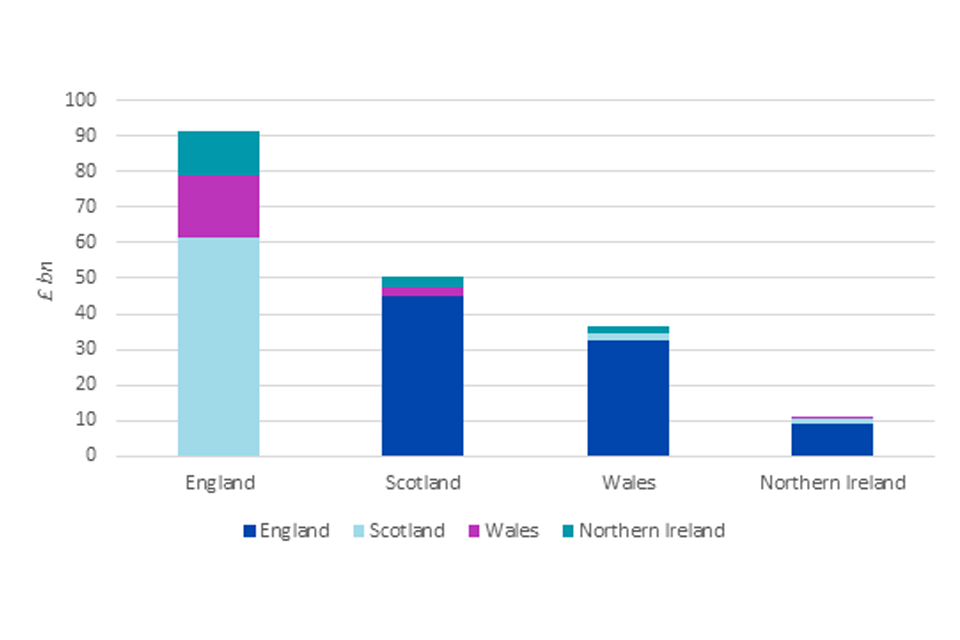

The most recent estimate of intra-UK trade that includes figures for England was published by the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE) in 2021, based on trade in 2015 (see Figure 1). ESCoE estimates that intra-UK sales (exports) in 2015 amounted to around £190bn. For context, this would represent over one-quarter of all UK exports (both intra-UK and extra-UK)[footnote 33] and around 10% of total GDP.[footnote 34] It shows that over 85% of intra-UK sales from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were made to England.

Figure 1: 2015 estimates of intra-UK sales (exports) by UK nation (£bn)

Image description: A bar graph of 2015 ESCoE data showing the value of sales in £s that each UK nation sold to each of the other UK nations. England sales to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were around £61m, £17.5m and £13m respectively. Scotland sales to England, Wales and Northern Ireland were around £45m, £2m and £3m. Wales sales to England, Scotland and Northern Ireland were around £33m, £2m and £2m respectively. Northern Ireland sales to England, Scotland and Wales were around £9m, £1m and £0.4m respectively.

Source: ESCoE (2021)

Note: Excludes non-resident flows (goods or services which move between UK nations but may be produced or provided by a non-resident to the UK).

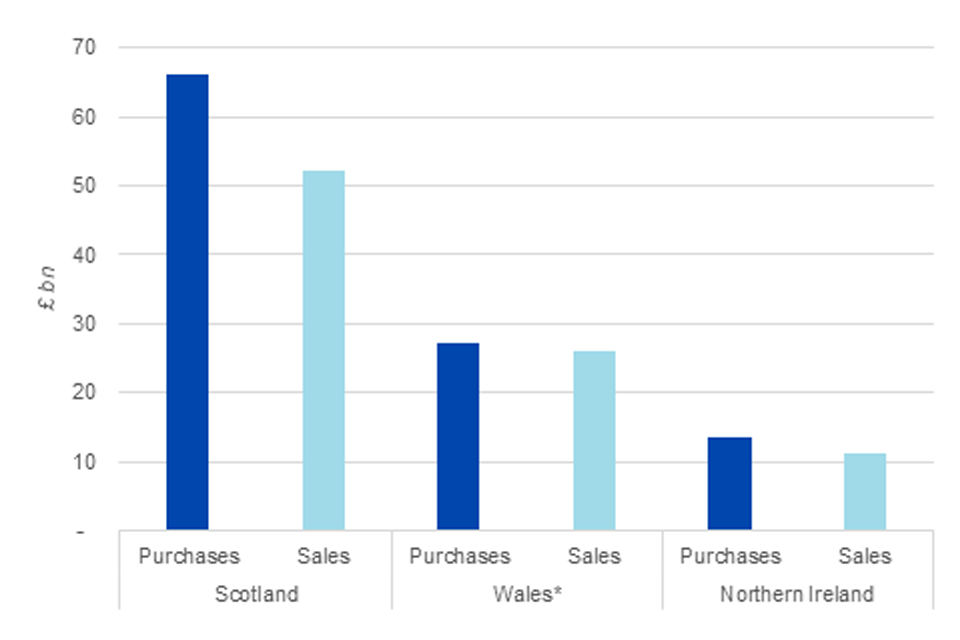

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland publish their own data on intra-UK trade covering both imports and exports. As of the date of finalisation of this report, the most recent year available for all 3 nations was 2019. This data, presented in Figures 2 and 3, shows that:

-

total intra-UK sales for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2019 amounted to £89bn

-

of these 3 nations, Scotland traded the most with the rest of the UK in absolute terms in 2019, followed by Wales and then Northern Ireland, with these absolute differences likely driven primarily by the relative sizes of their economies. Figure 2 also indicates that all 3 nations were net importers, suggesting that in 2019 England was a net exporter to the rest of the UK internal market

-

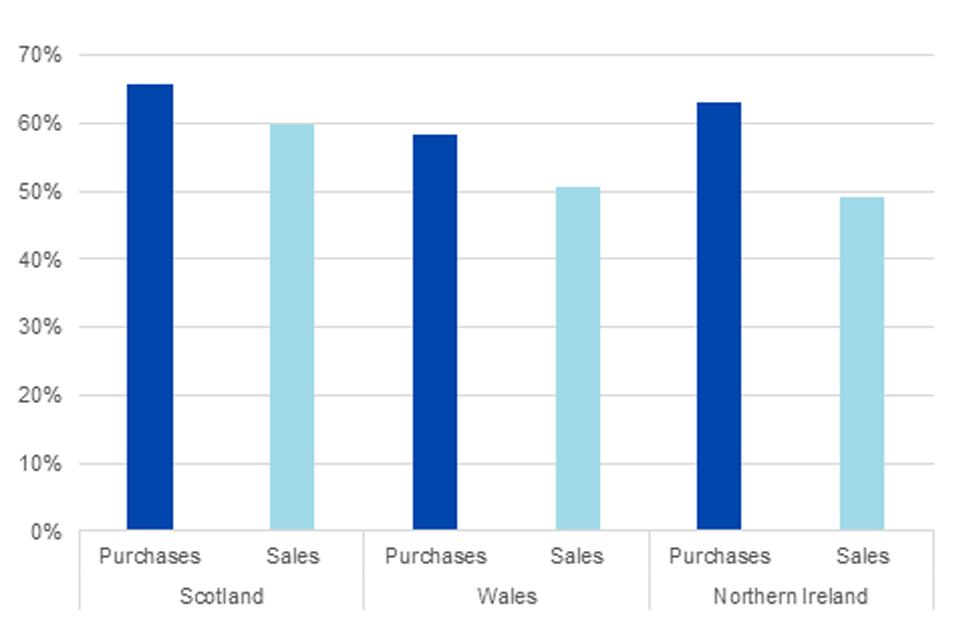

the volume of intra-UK trade as a proportion of each nation’s total external sales/purchases[footnote 35] was broadly similar for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland (see Figure 3). The proportion of external sales accounted for by intra-UK trade is significantly higher for each of these nations than the figure for the UK as a whole in 2015 (27%), suggesting that England accounts for a much bigger proportion of sales outside the UK[footnote 36]

Figure 2: Total external purchases and sales from/to the rest of the UK in 2019 for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland (£bn, 2019 prices)

Image description: A bar graph that gives purchases and sales from each of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to the rest of the UK for 2019. Scotland purchased £66bn from the rest of the UK and sold £52bn to the rest of the UK. Wales purchased £27bn from the rest of the UK and sold £26bn to the rest of the UK. Northern Ireland purchased £13bn from the rest of the UK and sold £11bn to the rest of the UK.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2019; Trade Survey Wales, 2019; Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, 2019; Export Statistics Scotland, 2019.

*Over 15% (c £16.5bn) of the value of internal market trade from Wales is ‘unallocated’ where respondents have been unable to allocate this trade to a specific destination therefore these figures are a lower estimate of Welsh trade with the rest of the UK.

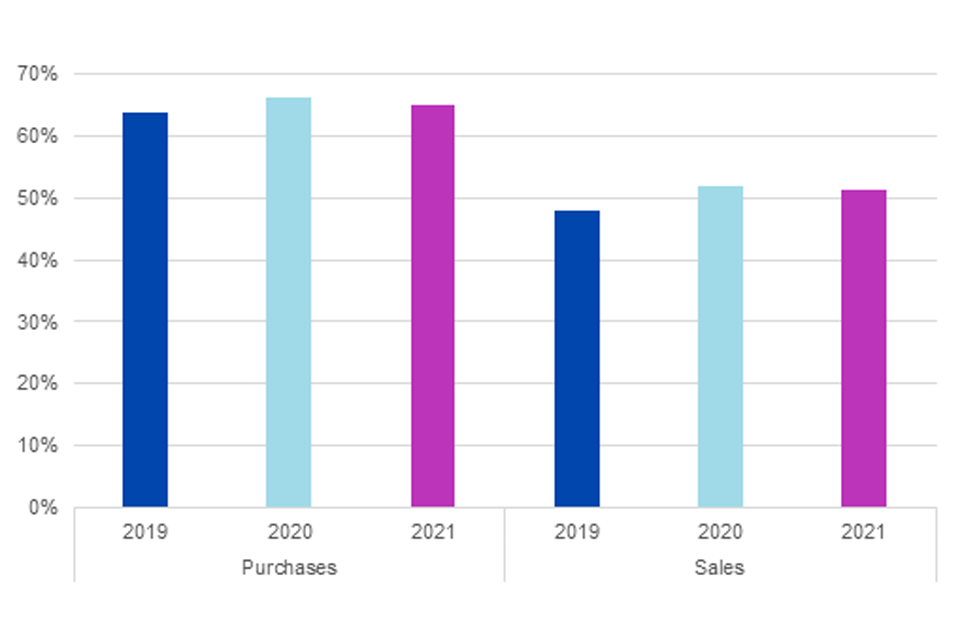

Figure 3: Intra-UK trade as a proportion of total external purchases/sales in 2019 for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

Image description: A bar graph showing the proportion of the value of intra-UK trade as a proportion of total external purchases/sales for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for 2019. For Scotland, 66% of purchases and 60% of external sales were to/from the rest of the UK. For Wales 58% of purchases and 51% of external sales were to/from the rest of the UK. For Northern Ireland 64% of purchases and 48% of external sales were to/from the rest of the UK.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2019; Trade Survey Wales, 2019; Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, 2019; Export Statistics Scotland, 2019.

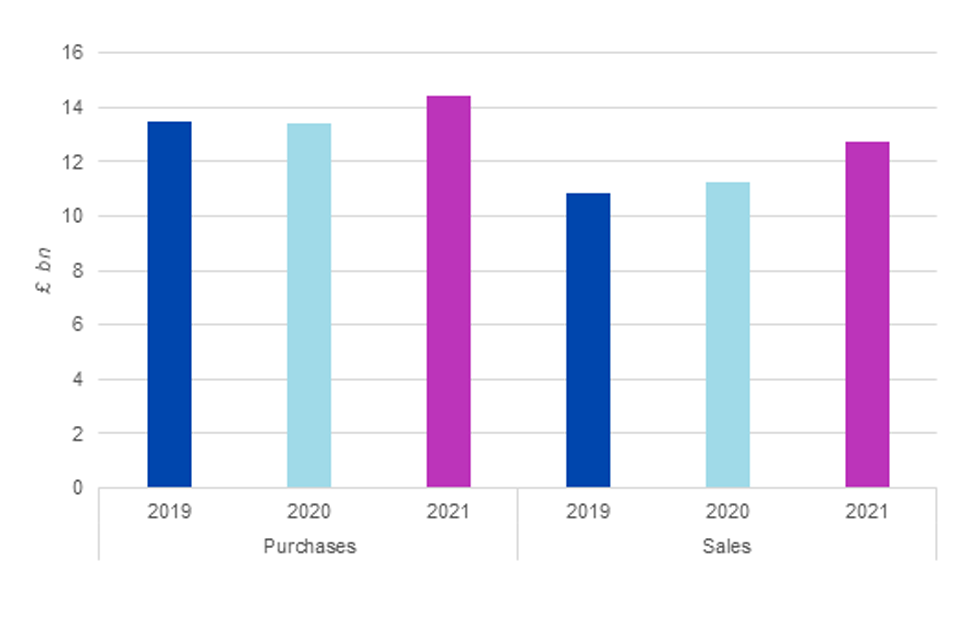

Northern Ireland has also published data for 2020 and 2021. The data suggests that trade between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK remained broadly unchanged during 2020, but grew in 2021, as shown in Figure 4. Whilst it is too early to fully understand what impacts COVID-19 had on trade patterns, it is likely to have constrained the absolute volumes and values of trade as economies locked down, mirroring the impact of COVID-19 on the economy of Northern Ireland more generally.[footnote 37] Figure 5 suggests that as a proportion of total external purchases/sales, Northern Ireland’s trade with the rest of the UK was slightly higher in 2020 and 2021 compared with 2019.

Figure 4: Total external purchases and sales from/to the rest of the UK for Northern Ireland 2019-2021 (£bn, 2021 prices)

Image description: A bar graph that gives purchases and sales to/from Northern Ireland to the rest of the UK for 2019, 2020 and 2021. Northern Ireland purchased £13bn from the rest of the UK in 2019, £13bn in 2020 and £14bn in 2021. It sold £11bn to the rest of the UK in 2019, £11bn in 2020 and £13bn in 2021.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2021.

Figure 5: Intra-UK trade as a proportion of total external purchases/sales for Northern Ireland 2019 to 2021

Image description: A bar graph showing the proportion of the value of intra-UK trade as a proportion of total external purchases/sales for Northern Ireland for 2019, 2020 and 2021. For Northern Ireland, purchases from the rest of the UK made up 64% of total external purchases in 2019, 66% in 2020 and 65% in 2021. Sales to the rest of the UK made up 48% of total external purchases in 2019, 52% in 2020 and 51% in 2021.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2021.

Who trades within the UK?

Our analysis of the available evidence suggests that a minority of businesses trade with other UK nations and that larger businesses and those in the manufacturing industry are more likely to trade with other nations in the UK than smaller businesses and ones in other sectors.

Evidence on who trades within the UK is available from the Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS), a fortnightly business survey conducted by the ONS. The ONS included the following question in 3 waves of the survey between August 2022 and February 2023:[footnote 38]

- ‘in the last 12 months, has your business sold goods or services to customers in other UK nations?’[footnote 39]

Results suggest that around 15% of businesses trade with customers in other UK nations.[footnote 40] For comparison, in the same waves of the survey, 10% of businesses had exported internationally in the last 12 months.[footnote 41]

The proportion of businesses with sales to customers in other UK nations varies significantly by industry. Across all 3 waves of the BICS, businesses in the manufacturing industry and wholesale and retail trade industry were the most likely to sell to customers in other UK nations, with over 20% of firms doing so in all 3 waves.[footnote 42]

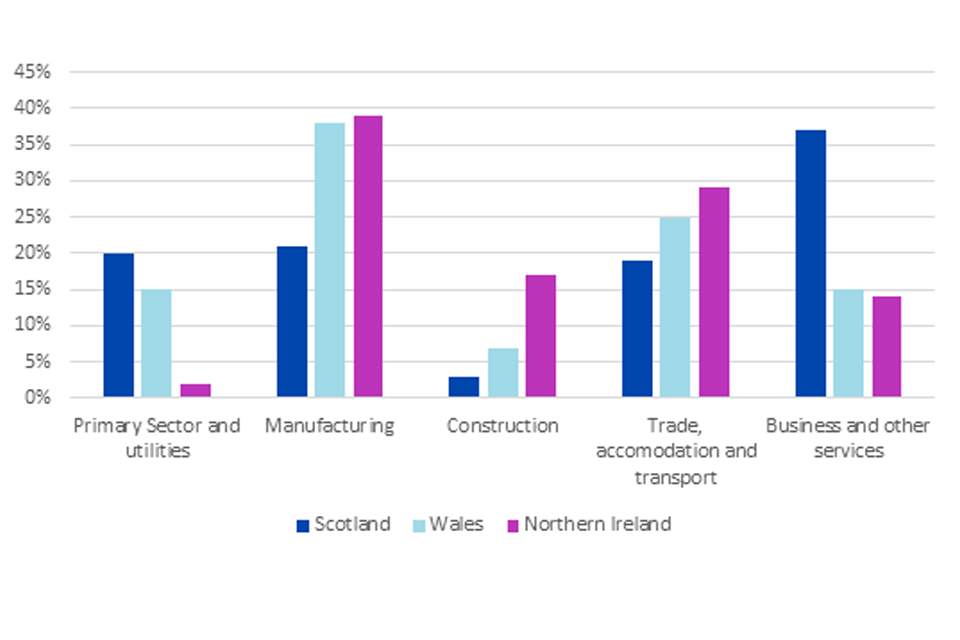

Evidence from the BICS is largely supported by other intra-UK trade data, as examined in our Overview Report, published in March 2022,[footnote 43] using intra-UK trade data from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (see Figure 6). The analysis suggested that for Wales and Northern Ireland the manufacturing sector made up the greatest proportion of sales to other UK nations in 2019, accounting for over a third of their sales to the rest of the UK. The business and other services sector was the largest in Scotland, followed by manufacturing.

Figure 6: Proportion of business that engage in intra-UK trade by broad industry sector, 2019

Image description: A bar graph showing estimates of sales to other UK nations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for five broad industry sectors (Primary sector and utilities; Manufacturing; Construction; Trade accommodation and transport; and Business and other services). For Scotland, 37% of sales to other UK nations were made by business and other services sector, 21% by manufacturing, 20% by primary sector and utilities, 19% by accommodation and transport and 3% by construction. For Wales, 38% were made by the manufacturing sector, 25% by the trade, accommodation and transport, 15% by primary sector and utilities, 15% by the business and other services, and 7% by construction. For Northern Ireland, 39% were made by the manufacturing sector, 25% by trade, accommodation and transport, 17% by construction, 14% by business and other services, and 2% by primary sector and utilities.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2021; Trade Survey Wales, 2019; Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, 2019; Export Statistics Scotland, 2019.

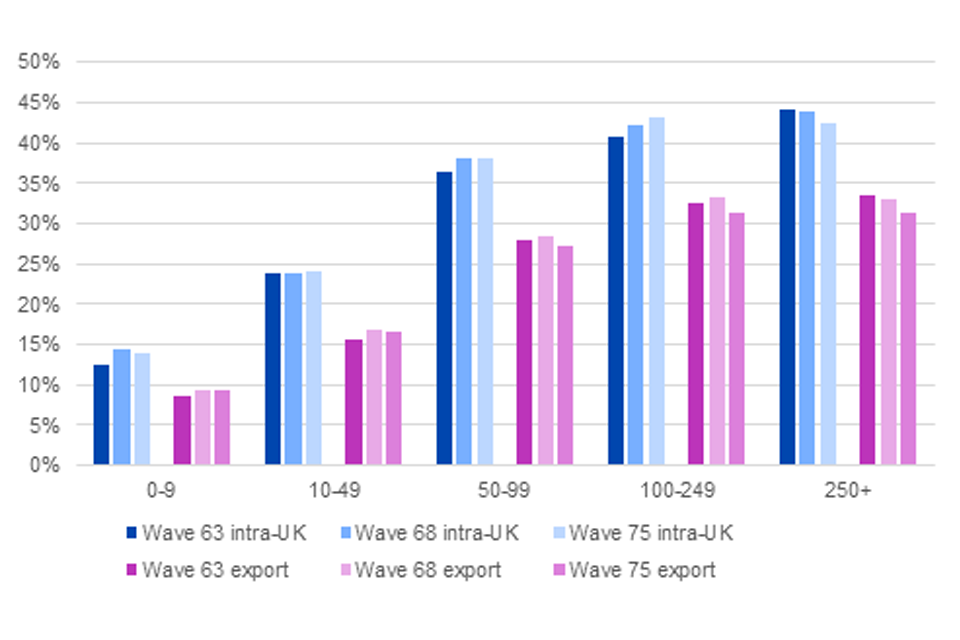

Evidence from the BICS suggests that larger businesses are more likely to trade across the UK than smaller ones. As shown in Figure 7, across all 3 waves of the BICS[footnote 44] less than 15% of micro businesses[footnote 45] made sales to other UK nations, compared with over 40% of large businesses.[footnote 46] Figure 7 also shows that the same pattern emerges for international trade, but with fewer firms exporting internationally than within the UK in the last 12 months.[footnote 47]

Figure 7: Proportion of businesses with sales to customers by destination and size band (employees)[footnote 48]

Image description: A bar graph showing the proportion of businesses with sales to customers by destination and size band. The graph shows that less than 15% of businesses with less than 10 employees made sales to other UK nations, compared with over 40% of businesses with more than 100 employees. The graph also shows that the same pattern emerges for international trade, but with fewer firms trading internationally than within the UK (just under 10% of businesses of businesses with less than 10 employees and just under 35% of businesses with more than 100 employees).

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey

Experiences of intra-UK trade

In addition to understanding the extent and patterns of intra-UK trade, we have considered how businesses are experiencing intra-UK trade.

The ONS included the following question in 3 waves of the BICS:[footnote 49]

- ‘in the last 12 months, which of the following challenges, if any, has your business experienced when selling goods or services to customers in other UK nations?[footnote 50]

Evidence from the BICS suggests that the majority of businesses that trade within the UK do not experience challenges when selling to other UK nations. In all 3 waves of the BICS, more than half of businesses that sold goods and services to customers in other UK nations did not face any challenges when doing so.[footnote 51] Of those businesses who did engage in trade with other UK nations, only a small number said they experienced challenges due to differences in rules or regulations, with less than 1 in 10 citing this as an issue in all 3 waves.[footnote 52]Transport costs were cited as the biggest problem to those businesses who experienced challenges when trading with other UK nations, with over 1 in 6 businesses citing this as an issue in all 3 waves.[footnote 53]

To get a deeper understanding of business experience of intra-UK trade, we commissioned qualitative research with 45 businesses who trade across UK borders. The sample group was selected in relation to 3 parameters: by nation, by size, and by sector, with a focus on agriculture, food and drink manufacture and retail, manufacturing and construction.[footnote 54] This approach ensured that the researchers could capture a range of business experiences, across the UK nations.

Given the low levels of intra-UK regulatory change since Brexit, an important feature of our qualitative research was the use of ‘hypothetical scenarios’ (scenarios) to provide businesses with an illustrative, generic example of intra-UK regulatory difference. The scenarios were:

-

scenario 1: ‘In your business, the main good/product you manufacture contains a specific input. One UK nation bans the sale of goods/products containing this specific input’

-

scenario 2: ‘1 UK nation imposes new labelling requirements on the main good/product that you manufacture’

-

scenario 3: ‘1 UK nation bans the supply of your services in its nation unless service providers like you comply with a new and additional (regulatory) requirement’

Evidence from this research found that few businesses had any experience of regulatory difference when trading within the UK. For participants in the research, intra-UK trade was often vitally important, accounting for a large proportion of their business. For small businesses who were much less likely to trade internationally, trade within the UK was considered especially important for their survival and growth.

Overall, intra-UK trade was seen to be working smoothly, with the majority of participants experiencing no or few problems trading across UK borders, a finding corroborated by our analysis of responses to the BICS, noted above. Indeed, for the research participants, borders within the UK did not appear to be a consideration when deciding where businesses would buy or sell. With little experience of regulatory difference across UK nations, businesses continue to see the UK as 1 market. Businesses reported that their planning and decision making was based on customer demand, supplier availability, and cost and travel distances, more than any consideration of borders within the UK and businesses did not typically seem to regard intra-UK trade as ‘trading across borders’.

The businesses who participated in our qualitative research focused on the current operating environment, in which challenges related to Brexit were a particular concern. The experience of a move away from EU regulations and standards had created a perception that regulatory difference within the UK would also be disruptive. The fact that intra-UK regulatory difference is a potential consequence of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU was not well understood by businesses in the research.

When presented with the concept of regulatory difference between UK nations, businesses struggled to understand who benefits from that difference. Some participants recognised that political aspirations or consumer pressure might drive regulatory change. But businesses were concerned that intra-UK differences could be costly and complex and disadvantage the economy overall, particularly in the context of other headwinds such as inflationary pressures.

Broadly speaking, businesses said that they should be able to cope with intra-UK divergence in the future, but when confronted with specific scenarios they reported that it felt challenging. For those who rely heavily on another UK nation’s market, the challenges would be more acute, and smaller businesses may find it more difficult to deal with due to more limited resources and a lack of experience in adapting to regulations. None of the participants in our sample had put in place specific plans to prepare for or mitigate against the potential challenges that might be created through regulatory change. This could reflect lack of awareness of potential change and also highlights that some businesses found their preparations for Brexit could not keep pace with events. Businesses reported that this prompted them to take a ‘wait-and-see’ approach until the specific details of further changes were known.

We also held roundtables with trade associations and businesses, legal professionals, and academics and policy professionals to understand stakeholder views on the effective operation of the UK internal market and the functioning of the arrangements set out in the Act. Evidence from these roundtables highlights that intra-UK trade is of critical importance and that generally businesses want to see consistency across the 4 nations, a finding also seen in our qualitative research.

Some participants commented that trade outside the UK is important, including for start-ups and newer companies. We heard that any additional barriers to trade could have impacts on the appetite for investment, which in turn might impact on the ability to export, and participants suggested that a well-functioning internal market is important for trade more widely.

Trade associations suggested that regulatory difference will disproportionately affect smaller businesses as increased cost implications will have a more significant impact on small businesses. Participants at the roundtables also suggested that regulatory differences could also affect consumers as any cost implications for businesses were likely to be passed on to the consumer.

Conclusion

The available data on intra-UK trade is currently limited, with long lags before figures are available for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and no data at all for England, and there are inconsistencies in the way data is collected and produced which hamper comparability. However, some indications have emerged. In particular, we found that intra-UK trade is very important to the UK nations, representing around 45% to 65% of the external sales and purchases of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, although less so for England as a result of the relative size of its economy.

We found that only a minority of businesses trade with other UK nations, and such trading is more common among larger businesses and in certain sectors, in particular manufacturing. These patterns, along with differences between the nations in terms of the relative importance of different sectors and differences in the distribution of firm sizes in their economies, impact on the importance of intra-UK trade to different nations.

Businesses are generally finding it easy to trade with other UK nations, with firms responding to both the BICS and our qualitative research generally indicating that they have not encountered challenges. Businesses are also largely unaware of the potential for regulatory differences between UK nations to arise. When the potential for such changes was raised with the participants in our qualitative research, and when discussed at our roundtables, stakeholders considered that it could raise challenges and that consistency was preferable, although the businesses we heard from mostly said that they would be able to adapt to regulatory difference. Our evidence, however, suggests that some smaller firms may find adaptation more challenging, and some concerns have been raised in relation to current key regulatory developments which may impact on the effective operation of the internal market, which we describe in the following chapter.

Regulatory developments

Introduction

This chapter discusses some current and upcoming regulatory developments that are affecting, or have the potential to affect, the UK internal market. It provides some brief background on each nation’s approach to the policy area or regulation in question and a summary of stakeholder commentary on its implications for the UK internal market. We then take a brief forward look at upcoming regulatory developments that could affect the UK internal market over the next 2 years. The conclusion draws out some common themes which we hope will assist policymakers when considering the potential impacts of regulatory change on the UK internal market.

Broadly speaking, developments are ordered based on the level of interest they have generated among stakeholders, primarily businesses and trade associations, and the level of policy detail that is publicly available to inform our analysis.

To identify the regulatory developments with the greatest potential to affect the UK internal market, we drew primarily on our desk-based monitoring of government consultations and the activity of the 4 legislatures. At our roundtables, we also asked participants about the areas in which they anticipated future change. The key areas that participants identified were agriculture (including agricultural subsidies, gene editing and biotech, pesticides and plant protection products, and animal transport), the environment (extended producer responsibility obligations, deposit return schemes, packaging, and waste) and food and drink (mycotoxins and HFSS foods). Other areas that were also raised included the automotive industry, the construction industry, chemicals, and cosmetics.

These topics are also consistent with the policy areas that were identified in the Overview of the UK Internal Market report as having potential to impact on the UK internal market; these were, regulatory developments relating to the environment, agriculture, animal welfare, food, drink and health.[footnote 55] In the future the OIM may look more closely at 1 or more of these areas, for example upon the request of a relevant national authority or through discretionary reviews or reports.[footnote 56]

In December 2022, we shared with the governments our emerging assessment that the following sectors were the most relevant developments from a UK internal market perspective: single-use plastic restrictions, deposit return schemes, genetic technology, and measures relating to food and drink that is high in fat, salt and sugar. We invited their input and the governments’ views were in line with our assessment.

Stakeholder commentary has been drawn from a range of sources, including submissions via our webform and the insights we gathered at our roundtables. We have also referenced published material such as evidence submitted to parliamentary committees, government correspondence and news reports. In many cases, the regulatory changes and associated issues set out in this chapter have elicited strong views from governments, businesses, trade bodies and third sector organisations. However, as noted in the previous chapter, our research suggests that most businesses trading across borders within the UK have not yet encountered regulatory differences between nations (as noted above, this report does not review the impact of the Protocol or its implementing legislation on the operation of the UK internal market).

The developments that we focus on in this chapter predominantly relate to goods. We saw no evidence of, and are not aware of, developments relating to services or professional qualifications which have occurred over the past 12 months which are expected to impact significantly on the UK internal market. We will continue to monitor these areas.

Requests to the OIM for advice/reporting under ss34 to 36 of the Act

In the last 12 months, we received 1 request, which was for a report under section 34 of the Act. This was in respect of Defra’s proposal to ban the sale of horticultural peat and horticultural peat-containing products in England.[footnote 57] Our report was published in February 2023.

Under the MAPs, if peat-containing growing media is lawfully produced in (or imported into) a part of the UK where it is also lawful to sell it, it can be sold in any UK nation, including England, without needing to comply with any requirements imposed by the regulation in England.

Our research and analysis identified that the use of peat in horticulture has fallen over the last decade, driven by greater use of peat-free growing media and reductions in the proportion of peat used in peat-containing growing media. This trend reflects changing environmental awareness amongst consumers, retailers’ desire to meet their Environmental, Social and Governance commitments, and manufacturers’ anticipation of government action to ban peat use. Despite these developments, in our report we found that peat would continue to be used in England for the next few years without the proposed ban.

Overall, we concluded that there will be limited incentives for manufacturers and retailers to sell peat-containing growing media in England once Defra’s proposed ban takes effect. However, that finding depends on good availability of the inputs needed to make peat-free growing media. While large-scale shortages are thought to be unlikely, some shortages may arise, creating the possibility that manufacturers and retailers will turn to peat-containing growing media.

The Welsh Government has announced that it intends to ban the retail sale of peat in horticulture in Wales and has said that it will work with the UK Government on next steps to implement the ban in Wales.[footnote 58] The Scottish Government has set out plans to restore degraded peatlands and has also committed to phasing out the use of peat in horticulture. The timescale for this will be informed by a consultation on ending the sale of peat in Scotland, which was published in February 2023.[footnote 59] The Northern Ireland Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) has consulted on an Equality Impact Assessment for the Northern Ireland Peatland Strategy in August 2022 and consultation responses are expected to be published in early 2023. The draft Northern Ireland Peatland Strategy contains a proposal to conduct a review and publish a key issues paper on peat extraction and the use of peat and peat products by 2023 and take forward any recommendations made.[footnote 60]

Deposit return schemes (DRS)

Description

All 4 governments in the UK are in the process of introducing deposit return schemes (DRS). These schemes aim to maximise recycling rates for drinks containers by incentivising consumers to return them. A charge is applied to in-scope containers, which can be redeemed when the container is returned. Retailers who operate a return point for containers will receive a handling fee for managing the returned containers. Producers will be required to pay a producer fee, which contributes to the operating costs of each scheme and to meet certain obligations.

The Scottish Government’s scheme is due to become operational on 16 August 2023.[footnote 61] The scheme in England, Northern Ireland and Wales are due to be launched on 1 October 2025.[footnote 62]

The schemes are designed along broadly similar lines, with 1 or more scheme administrator and obligations placed on producers and retailers. Circularity Scotland Ltd will be the scheme administrator in Scotland. Producers placing drinks on the Scottish market will be subject to certain obligations, including to repay deposits and take back returned containers. They can opt to meet these obligations directly or the scheme administrator can act on their behalf.[footnote 63] We understand that it is intended that the scheme in England, Northern Ireland and Wales will be administered by a single Deposit Management Organisation (DMO), which is due to be appointed by summer 2024.[footnote 64] Producers in these nations will need to register with the DMO before they can place in-scope containers on the market, and the DMO will collect returned containers on their behalf.

In all nations, retailers selling relevant containers will have to host a return point unless they have been exempted. In Scotland, exemptions will be granted by Scottish Ministers.[footnote 65] An exemption can be requested on grounds of proximity or environmental health. Broadly speaking, these mean that a nearby return point is willing to accept returns on a business’s behalf, or that operating a return point would put a business in breach of other legislation, such as environmental health, food or fire safety.[footnote 66] In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the DMO will be responsible for exemptions.[footnote 67] The consultation response setting out details of the schemes in England, Wales and Northern Ireland suggests that the grounds for exemption will be similar to those in the Scottish scheme.[footnote 68] The environmental regulator in each part of the UK and Trading Standards will be responsible for enforcement of the proposed schemes.[footnote 69]

While there are similarities between the schemes, there are expected to be differences between the schemes in Scotland and the rest of the UK, as well as differences between the schemes in England, Northern Ireland and Wales. One difference concerns labelling: in Scotland, the scheme administrator has determined that the producer fee will be higher for products that do not carry Scotland-specific labels and barcodes. Defra, the Welsh Government and DAERA intend to mandate the use of a mark to identify products as part of a DRS and the use of an identification marker such as a barcode or QR code, to enable the container to be recognised at the return point. The details and design of these markings will be decided by the DMO.

Another difference concerns the materials in scope. The proposed scheme in England and Northern Ireland will cover polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic, steel and aluminium containers. Schemes in Scotland and Wales will also include glass containers.

A potential difference may also concern the deposit and producer fees across the various DRS. For the DRS in Scotland, the deposit level and producer registration fee are set by the regulations at the fixed rate of 20p and £365, respectively.[footnote 70] The deposit level and producer registration fee for the proposed scheme in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are to be set by the DMO and may differ from those set in Scotland.

The Scottish Government has begun the process of seeking to exclude the deposit return scheme regulations from the MAPs.[footnote 71]

Stakeholder commentary

DRS is the issue on which we have received the most webform submissions via our online reporting service. We set out below some of the points stakeholders have raised with us.

Producers and retailers have raised concerns about glass being in scope in Scotland and Wales, but not in England and Northern Ireland. They indicated that glass is costlier to process than other container materials, being heavier and non-compressible. It must therefore be collected more often and transported in smaller quantities.[footnote 72] Environmental groups have expressed disappointment that glass will not be included in the DRS in England and Northern Ireland.[footnote 73]

As a higher producer fee will be charged to producers who use a UK-wide label in Scotland, producers have told us that they will face additional costs: either via the higher producer fee, or via the cost of designing and printing different labels and managing the logistics of tracking which stock will be sold in Scotland (including the risk that some stock becomes obsolete if it is accidentally sent to the wrong nation). Producers have indicated that they will face a new administrative and logistical burden in determining in advance how much of their stock will be sold in Scotland. We have also heard from importers who have told us that overseas drinks producers are unlikely to adopt a Scotland-specific label or barcode, meaning that their products will either be withdrawn from sale in Scotland, or they will need to incur the cost of relabelling products that are destined for the Scottish market.

A significant concern for retailers initially was that they would be required to offer an online takeback service for containers under the Scottish Government scheme – ie, customers who ordered containers for delivery could also arrange for them to be collected. The Scottish Government will amend the DRS regulations so that online takeback will be offered from 2025 and only by the largest grocery retailers.[footnote 74]) Defra, the Welsh Government and DAERA have said that they are ‘keen to ensure large supermarkets delivering grocery shopping’ offer a takeback service as soon as their scheme launches. They are considering how other online businesses could offer a takeback service where feasible.[footnote 75]

Some producers have said that they may consider withdrawing from the Scottish market, either permanently or until harmonised DRS are in place across the UK.[footnote 76] This is because they feel that the additional cost of complying with the requirements of a DRS in Scotland alone could mean that operating there ceases to be financially viable.

To date, most commentary on the proposed DRS in England, Northern Ireland and Wales – which is less advanced in terms of the policy and implementation detail than in Scotland – has focused on the environmental implications of excluding glass from the scope of the scheme, and on the 2025 launch date. Commentators have also noted the potential complexity of complying with different approaches across the UK, with the British Retail Consortium saying, ‘If the UK Government is to press ahead, it must ensure the scheme is aligned with the devolved nations, allowing efficiencies of scale to reduce the costs and complexity which will face consumers.’ [footnote 77]

Single-use plastic products

Description

Proposals have been, or are being, brought into force across all parts of the UK to tackle the issue of single use plastic waste, but there are some differences amongst the approaches across the 4 nations.[footnote 78]

The Scottish Government implemented a ban that came into force on 1 June 2022 on the supply and, in many cases, the manufacture of certain single use plastic products, including drink stirrers, drinking straws, plates, cutlery, balloon sticks and expanded polystyrene containers.[footnote 79]

The Senedd passed the Environmental Protection (Single-Use Plastic Products) (Wales) Bill in December 2022. [footnote 80] This will provide for the banning of certain single use plastic products. Three of the items included in this Bill are not encompassed by existing or announced forthcoming bans in England and Scotland. These items are single use carrier bags, items made from oxo-degradable[footnote 81] plastic and polystyrene lids for cups or takeaway food containers. The Bill also introduces the power for Welsh Ministers to add to or amend the list of single use products.

The UK Government has announced plans to ban the supply in England of some single use plastic items that have been banned in Scotland and are due to be banned in Wales, including plates and cutlery – although the English ban will not apply to plates, trays and bowls used as packaging in shelf-ready pre-packaged food items (such as pre-packaged salad bowls), as these will be covered by an extended producer responsibility scheme.[footnote 82]The supply of cotton buds had already been banned in England and Scotland prior to the entry into force of the Act, along with single-use plastic straws and drink stirrers in England.[footnote 83]

Under the Protocol, Northern Ireland is subject to the EU Directive on Single Use Plastics which came into force on 1 January 2022. The Directive bans the supply of single-use plastic plates, cutlery, straws, balloon sticks, cotton buds, expanded polystyrene cups and food containers, and oxo-degradable plastic products. Northern Ireland is required to implement the Directive’s requirements.

The Scottish Government regulations ban both the supply and manufacture of many of the products in question. This contrasts with the bans in England, Northern Ireland and Wales, which cover supply only. The Scottish Government secured an exclusion that would disapply the MAPs in relation to the supply of the plastic products banned under the Scottish Government’s regulations. The exclusion was agreed under the Resources and Waste Common Framework.[footnote 84]

Stakeholder commentary

There has been very little commentary from businesses and consumers on the practical impacts of the differences between bans on single-use plastic items in different nations, and the differing timescales on which they have been introduced.

In the Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment accompanying the Scottish Government regulations, trade associations from the packaging and food and drink sectors noted that there had been a shift away from single-use plastic items to alternatives in recent years.[footnote 85] It was noted that this trend was driven by several factors: pressure from consumers; a belief that investing in products perceived as more environmentally friendly is a sound business decision; the direction of travel set by the EU Single Use Plastics Directive; and the ready availability of substitutes.

Following engagement with stakeholders, including manufacturing organisations and retailer organisations, the Welsh Government’s impact assessment reached a similar conclusion, namely that there are suitable non-plastic alternative items already on the market for most of the items that the Welsh Government proposes to ban.[footnote 86]

While an exclusion to disapply the MAPs for the supply of the relevant plastic products was secured, the Scottish Government has raised concerns about the length of time it took for the exclusion to be agreed and about its scope (the Scottish Government and the Welsh Government had supported a broader exclusion).[footnote 87] Both the Scottish Government and the Welsh Government have noted that the scope of the current exclusion makes requests for further exclusions in this area likely.[footnote 88]

There was a period of a little over 2 months when the Scottish Government’s ban was in force, but the statutory instrument creating the exclusion was not. During this time, there was some discontent from catering suppliers who had chosen to comply with the ban but were concerned about losing sales to competitors who continued to supply cheaper plastic products.[footnote 89] Suppliers also reported feeling pressured into ceasing to sell products that were not yet illegal. They called for clear messaging about what they could and could not sell legally, and from when.[footnote 90]

Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding)

Description

In May 2022, the UK Government introduced the Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Bill,[footnote 91] which alters the definition of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in England to exclude certain organisms created via precision breeding technologies. Precision breeding uses genetic technology to modify plants and animals in ways that could have occurred naturally or been produced via traditional breeding. The proposed change is intended to simplify the process of obtaining authorisation to market precision-bred plants and animals, relative to the requirements for authorising GMOs. The UK Government has stated that new genetic technologies can ‘increase yields, make our food more nutritious and result in crops that are more resistant to disease and weather extremes.’[footnote 92] The Bill covers gene edited crops and animals and the food and feed derived from them, but the provisions relating to gene editing of animals will not come into force until an appropriate regulatory regime is in place.[footnote 93]

The proposed substantive changes are intended to take effect in England only. Under the MAPs, if precision-bred plants and animals are lawfully produced in (or imported into) a part of the UK where it is also lawful to sell them, they can be sold in any UK nation without needing to comply with requirements imposed by regulations there.

The EU has consulted on developing a legal framework for plants obtained via certain new genomic techniques, similar to those described as precision bred by the UK Government.[footnote 94] Its proposals could have a similar effect to some of the proposed changes in England; namely, making it easier to market gene edited plants in the EU. However, any change to the EU regulatory regime is likely to come into force later than the change to the law in England, and the European Commission proposals consulted on to date would not apply to animals.

In relation to Common Frameworks, we understand that the Bill has the potential to intersect with (potentially, at least) 4 provisional Common Frameworks: namely, Animal Health and Welfare, Food Compositional Standards and Labelling, Food and Feed Safety and Hygiene, and Plant Varieties and Seeds Common Frameworks.

Stakeholder commentary

Concerns have been raised that farmers in England who use precision-bred crops may acquire a competitive advantage over farmers elsewhere in the UK, as gene-edited crops have the potential to be more resistant to pests and diseases and more resilient to the effects of climate change.[footnote 95]

In addition, representative bodies for agriculture have raised a concern that, if plant breeders in England start to rely on precision breeding techniques and discontinue their previous products, this could limit the supply of seeds available to farmers in Wales and Scotland and create a ‘two-track system for breeding crops.’[footnote 96]

The Scottish[footnote 97] and Welsh Governments[footnote 98] have also raised concerns that the draft primary legislation does not require precision-bred products to be labelled as such. They note that this has potential implications for consumers’ ability to make informed choices about what they buy, and for enforcement of the devolved GMO regimes in Scotland and Wales. The Food Standards Agency is considering how to provide consumers with information about products produced using precision breeding techniques, including the possibility of voluntary or mandatory labelling schemes, a public register of authorised precision bred organisms (PBOs) and more general consumer awareness campaigns.[footnote 99]

Both the Scottish Government and the Welsh Government have publicly expressed dissatisfaction with the level of intergovernmental engagement before the Bill was published. The Welsh Government Minister for Climate Change said that the Bill ‘although nominally restricted to England, will have important effects across the whole of the UK.’[footnote 100] The Minister said that there was no meaningful engagement at Ministerial level before the Bill was published, and that officials were only presented with limited policy detail shortly beforehand. The Scottish Government Minister for Environment and Land Reform has expressed similar sentiments and her disappointment at the ‘invitation for Scotland to join in the legislation coming the day before the Bill was introduced in the UK Parliament.’[footnote 101]

Both Ministers raised concerns about relevant discussions having only been initiated under Common Frameworks after the Bill had been introduced, saying that discussion before publication would have enabled advance consideration of potential policy divergence.[footnote 102]

Food and drink that is high in fat, salt and sugar (HFSS)

Description

The UK Government has introduced restrictions on volume price promotions and placement of HFSS food and drink in England under the Food (Promotion and Placement) (England) Regulations 2021.[footnote 103] These restrictions on the location of HFSS products in key selling locations such as checkouts, store entrances, aisle ends, and their online equivalents came into force in October 2022. Restrictions on the selling of HFSS products by volume price such as ‘buy 1 get 1 free’ or ‘3 for 2’ will come into force on 1 October 2023. Since April 2022, large businesses in England have also been required to display calorie information on out-of-home food, for example on menus.

In summer 2022, the Scottish Government[footnote 104] and the Welsh Government[footnote 105] separately consulted on proposals to restrict promotions of HFSS food and drink. The Scottish Government’s consultation sought views on price and location restrictions including proposals to include meal deals within the category of price promotions. The consultation closed at the end of September 2022. Responses are being analysed to help inform the development of the policy and external analysis will be published shortly. In addition, the Welsh Government’s consultation covered proposed policies including mandatory calorie labelling at the point of choice in the out-of-home sector and exploring ways to reduce the density of hot food takeaway outlets, especially near secondary schools. The Welsh Government published a summary of the responses to its consultation in January 2023.

There is potential for regulations across Scotland, Wales and England to differ. The Welsh Government proposes to include temporary price reductions on HFSS food and drink, such as ‘50% off’ offers, in the scope of its restrictions. The Welsh Government intends to count meal deals as a volume promotion, meaning that legislation would prohibit HFSS products from being included in meal deal offers. The UK Government regulations for England ban neither temporary price reductions, nor the inclusion of HFSS food and drink in meal deals.

We are not aware of any plans to restrict the promotion of HFSS food and drink in Northern Ireland.

Stakeholder commentary

A number of retailers across the UK have voluntarily removed multi-buy promotions of less healthy products and are looking to support consumers to make healthier choices. They have also told us that differences between restrictions on the promotion and placement of HFSS food and drink in each nation may make it harder to sell products across the UK.

Businesses responding to the Welsh Government’s consultation on proposed restrictions emphasised the value of alignment with the English legislation in order to avoid, in their view, unnecessary complexity.[footnote 106] Businesses said that the legislation should align with the recent restrictions in England to avoid logistical challenges, extra costs and confusion for businesses.[footnote 107]

In addition, 1 of the OIM’s roundtable participants suggested that differences in restrictions may make e-commerce harder, creating costs and an administrative burden for businesses who need to direct different information to customers in different parts of the UK. This view was echoed in responses to the Welsh Government’s consultation: the complexity of differing from England was highlighted by online-only businesses who argued that they do not have country-specific ‘apps’ that comply with the legislation of each nation. They suggested that creating an alternative app for Wales would be costly and confusing for customers.[footnote 108]

Glue traps and snares

Description

The Scottish Government, the UK Government and the Welsh Government are all taking steps to ban the use of glue traps, which are small boards covered with strong, non-drying, adhesive that are generally used to catch rodents in indoor settings. There are concerns that glue traps are inhumane, often causing prolonged suffering, and sometimes capture non-target species such as hedgehogs and pet cats.[footnote 109]The Scottish Government is proposing to ban the sale and use of glue traps, including for pest control professionals, during the current parliamentary term (ie, before May 2026).[footnote 110] The Welsh Government is planning to ban all use of glue traps (through the Agriculture (Wales) Bill, which is currently in the Senedd) for vertebrates,[footnote 111] and the UK Government is banning the use of glue traps from April 2024, but with the ability for pest control professionals to apply for a licence to continue using them in exceptional circumstances.[footnote 112] We are not aware of any plans to ban the sale or use of glue traps in Northern Ireland.

Governments are also considering their approach to the use of snares, a type of trap used to catch or restrain wild animals, most commonly foxes. Self-locking snares have been illegal across the UK since 1981, but governments are considering their approach to free-running snares.[footnote 113]The Agriculture (Wales) Bill includes a prohibition on the use of all snares, and the Scottish Animal Welfare Commission[footnote 114] has published a position paper recommending that the Scottish Government ban their sale and use.[footnote 115] There are no known current plans to make free-running snares illegal in England or Northern Ireland.

Stakeholder commentary