Health matters: smoking and mental health

Published 26 February 2020

Summary

This edition of Health Matters focuses on smoking among the population of people living with a broad range of mental health conditions, ranging from low mood and common conditions such as depression and anxiety, to more severe conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Definitions

Poor mental health: linked with other risk factors, such as smoking, physical health conditions, drug use or alcohol misuse, poor mental health refers to thoughts, emotions or behaviours that we often perceive as signs of a possible mental health problem, which can range from common to severe conditions

Long-term mental health condition: similar to severe mental health conditions, but often including severe anxiety and depression

Severe mental health condition: also referred to as severe mental illness, it covers a range of needs and diagnoses, including but not limited to:

- psychosis

- bipolar disorder

- ‘personality disorder’ diagnosis

- eating disorders

- severe depression

- mental health rehabilitation needs - some of which may be co-existing with other conditions such as frailty, cognitive impairment, neurodevelopmental conditions or substance use

Scale of the problem

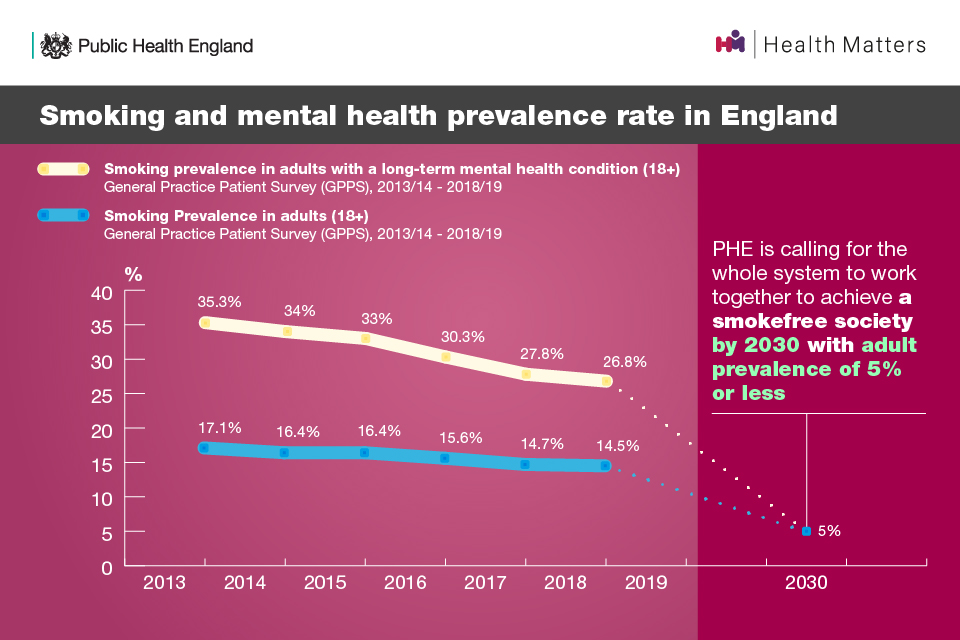

Smoking rates are declining in England, with prevalence in adults (aged 18+) having decreased from 17.1% in 2013 to 2014 to 14.5% in 2018 to 2019 (General Practice Patient Survey data).

While a decrease in smoking rates has also been seen among adults with a long-term mental health condition – falling from 35.3% in 2013 to 2014 to 26.8% in 2018 to 2019 – prevalence remains substantially higher, despite the same levels of motivation to quit.

The gap in smoking prevalence between the general population and people with a mental health condition appears to have narrowed in recent years. However, more data and further analysis are needed to confirm these findings, as other population surveys, such as the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) suggest that smoking prevalence rates are declining for both groups, but the gap is remaining the same.

The association between smoking and mental health conditions

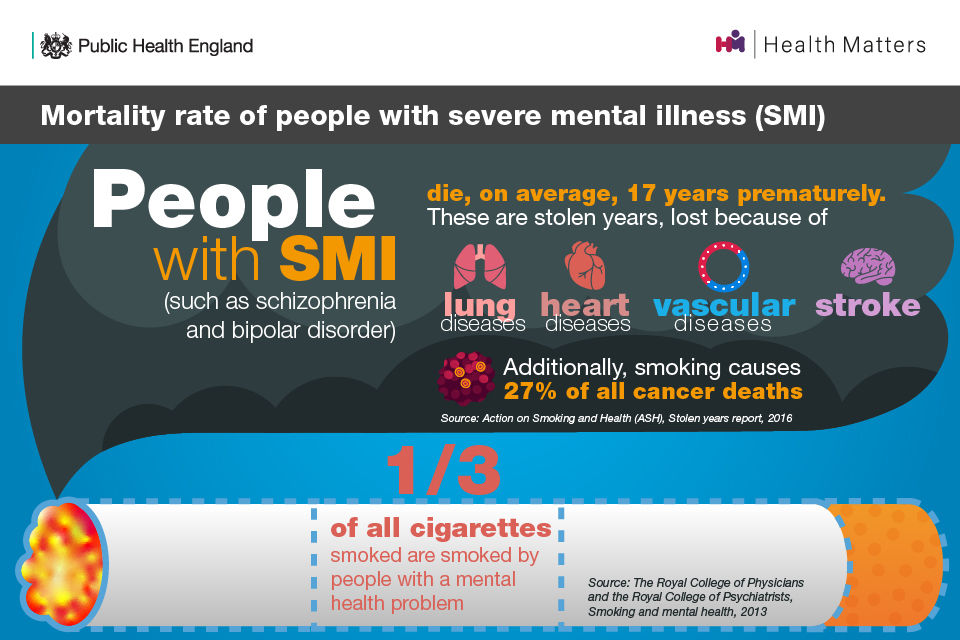

People with poor mental health die on average 10 to 20 years earlier than the general population, and smoking is the biggest cause of this life expectancy gap. A third of cigarettes smoked in England are smoked by people with a mental health condition.

Research has found that having a mental health condition is associated with:

- current smoking

- heavy smoking and high levels of tobacco dependence

- desire to quit

- difficulty remaining abstinent

- perceived difficulty remaining abstinent

This is the same for all mental health conditions individually, but the strength and significance of the associations vary depending on the condition.

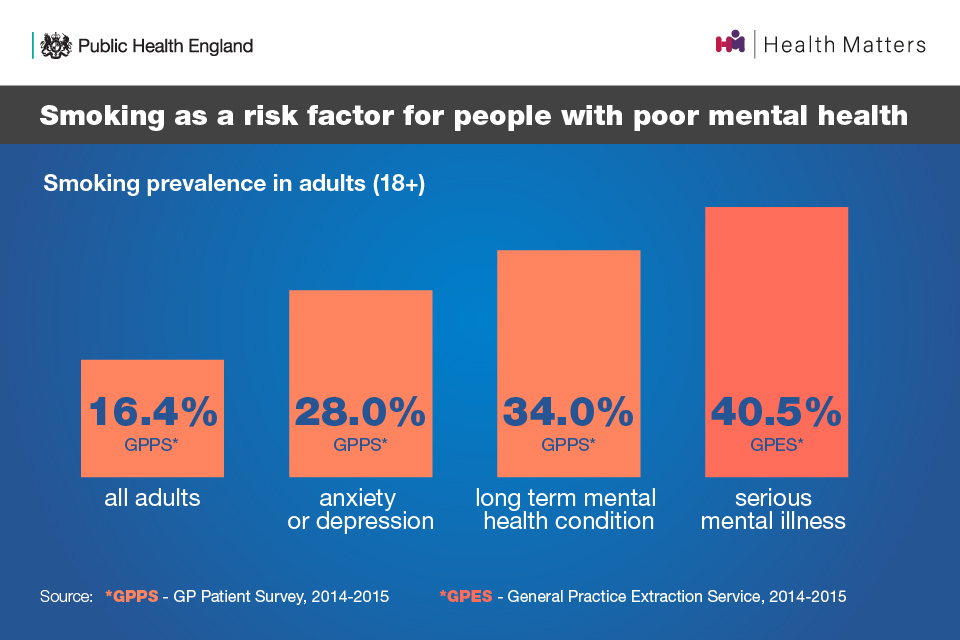

PHE’s Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England have 3 indicators that report smoking prevalence depending on the severity of mental health conditions. These show that as the severity of mental health conditions increases, smoking prevalence is higher.

In 2014 to 2015, prevalence in all adults (aged 18+) was 16.4% and prevalence in adults living with:

- anxiety or depression was 28%

- a long-term mental health condition was 34%

- serious mental illness was 40.5%

Evidently, even common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, are associated with a greater likelihood of smoking and of being highly dependent.

People with poor mental health are also more likely to live in circumstances of socioeconomic deprivation. This is partly because deprivation plays a role in the causal pathway to developing a mental health condition (the stress-vulnerability model), and partly because living with poor mental health can lead to loss of employment, housing, income and other attributes.

This relationship is also likely to impact on the prevalence of smoking in people with poor mental health because smoking is strongly associated with socioeconomic deprivation and can itself exacerbate socioeconomic deprivation.

Addressing higher dependence on tobacco is likely to support smoking cessation, and in turn, reduce health disparities.

The government’s commitment on mental health and smoking

The NHS Long Term Plan commits to offering NHS-funded tobacco treatment services to all inpatients (including mental health) and pregnant women, as well as high-risk outpatient groups. On the advice of Public Health England (PHE), this will include the option to switch to e-cigarettes while in inpatient settings.

The plan also acknowledges that people with a long-standing mental health condition are twice as likely to smoke, with the highest rates among people with psychosis or bipolar disorder. To address this, the plan says that by 2020 to 2021, the NHS will ensure that at least 280,000 people living with severe mental health conditions have their physical health needs met.

By 2023 to 2024, the NHS will further increase the number of people receiving physical health checks to an additional 110,000 people per year. This will bring the total to 390,000 checks delivered each year, including the ambition in the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health.

The government’s Prevention Green Paper also highlights that smoking rates remain stubbornly high among people living with mental health conditions. It acknowledges that tackling this inequality is the core challenge in the years ahead and that if England is to achieve being a smokefree society by 2030, bold action is required to both discourage people from starting in the first place and support smokers to quit.

It also states that the government is committed to monitoring the safety, uptake, impact and effectiveness of e-cigarettes and to assess further innovative ways to deliver nicotine with less harm than smoking tobacco.

The benefits of quitting smoking for mental health

One systematic review of mental health professionals’ attitudes towards smoking and smoking cessation found that a ‘significant proportion of mental health professionals held attitudes and misconceptions that may undermine the delivery of smoking cessation interventions’. It also found that many report a lack of time, training and confidence as the main barriers to addressing smoking in their patients.

There is also the common misconception among both the public and health professionals that smoking relieves depression and anxiety, and that quitting will cause unnecessary discomfort for those with poor mental health. However, the opposite is true - smoking cessation improves both physical and mental health, even in the short term, and reduces the risk of premature death.

Stopping smoking can be as effective as antidepressants

A meta-analysis and systematic review of change in mental health after smoking cessation found that compared to continuing to smoke, quitting smoking was associated with reduced depression, anxiety and stress, and improved positive mood and psychological quality of life. The effect size seems as large for those with poor mental health as those without.

Furthermore, the effect sizes are equal to or larger than those of antidepressant treatment for mood and anxiety disorders.

Although tobacco withdrawal can reduce happiness in the short term, ‘staying quit’ is associated with greater happiness. Happier and less depressed smokers are more likely to quit successfully and, once they have quit, report reduced depression.

Videos produced by Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) in partnership with the University of Bath and University of York show the journey of smokers with mental health conditions who have successfully quit and call on health professionals to do more to help others do the same.

Stopping smoking can reduce the amount of psychiatric medication needed

Tobacco smoke interacts with some psychiatric medicines, often increasing the rate of their metabolism. This makes them less effective, resulting in increased dosages being required and more side effects associated with these drugs.

Therefore, smokers on these medicines who reduce or eliminate their tobacco consumption can expect to be prescribed lower doses.

Read more about this in ASH’s fact sheet on smoking and mental health.

Smoking cessation support for people with poor mental health

The smoking cessation intervention for severe mental illness (SCIMITAR+) trial found that quit support is effective in this population. The incidence of quitting at 6 months shows that cessation can be achieved, but the waning of this effect by 12 months means more effort is needed for sustained quitting.

Smokers reporting depression or anxiety are more likely to be offered stop smoking support by their GPs, but this does not appear to translate into the use of quitting aids, despite high motivation to quit. As higher tobacco dependence is seen among this group, mental health-specific support may need to be offered and more must be done to make this offer attractive.

Dr Emily Peckham spoke to Health Matters about SCIMITAR and SCIMITAR+

ASH’s Progress towards smokefree mental health services report found that all surveyed trusts offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to their patients, but only 47% offered the choice of combination NRT or varenicline in line with NICE best practice.

Very Brief Advice (VBA)

VBA is a model of support designed for opportunistic use by healthcare professionals to trigger a quit attempt among smokers. It is defined by a 3-step process:

- establishing and recording smoking status (ask)

- advising on the most effective way to stop (advise)

- referring to specialist stop smoking support or prescribing stop smoking medicines (act)

All healthcare professionals should use VBA to support smokers to quit.

Varenicline

One in 4 people in the UK who successfully quit smoking used varenicline prescribed by their GP or a stop smoking service. With only 47% of mental health trusts offering the choice of combination NRT or varenicline, it is evident that this medicine is not being prescribed in significant amounts for patients in secondary care.

While prescriptions of varenicline have reduced, a study has suggested that varenicline is more effective than NRT for smoking cessation in patients with mental health conditions. Specifically, the study found that smokers with mental health conditions who were prescribed varenicline were 19% more likely to have successfully quit at 2-years follow-up, than NRT.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ (RCPsych) position is that psychiatrists should consider the prescription of varenicline when clinically indicated as 1 of the options to support patients with severe mental health conditions to stop smoking. RCPsych is also working with other organisations to raise awareness among psychiatrists and other prescribers of its efficacy and safety.

Read more about the RCPsych’s position on the prescription of varenicline in their position statement.

E-cigarettes

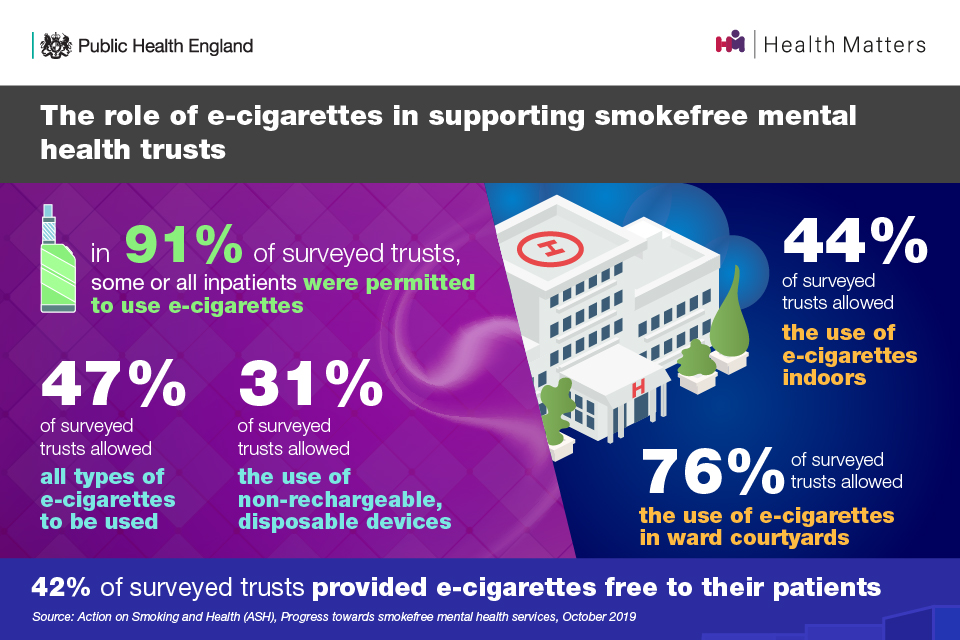

E-cigarettes are now widely used within acute mental health services but their use is restricted in a variety of ways. ASH’s Progress towards smokefree mental health services report found that in 91% of surveyed trusts, some or all inpatients were permitted to use e-cigarettes:

- 47% of surveyed trusts allowed all types of e-cigarettes to be used

- 31% of surveyed trusts only allowed the use of non-rechargeable, disposable devices

Secondly, it found that all but 1 trust restricted where e-cigarettes could be used:

- 44% of surveyed trusts allowed the use of e-cigarettes indoors

- 76% of surveyed trusts allowed the use of e-cigarettes in ward courtyards

Thirdly, it found that 42% of surveyed trusts provided e-cigarettes free to their patients.

RCPsych’s position statement, The prescribing of varenicline and vaping (electronic cigarettes) to patients with severe mental illness states that psychiatrists should advise patients who smoke that e-cigarettes are substantially safer than continued tobacco use and may help them to quit, particularly when used in conjunction with stop smoking treatments.

The report also states that the college supports the recommendation of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee that all mental health provider organisations should ensure they have policies in place that facilitate the safe and effective use of e-cigarettes.

There are resources available to inform the safe use of e-cigarettes in inpatient settings, covering the use and charging of e-cigarettes, which can provide reassurance to Health Fire Officers and Health and Safety Officers.

The National Fire Chiefs’ Council (NFCC) has published guidance on e-cigarette use in smokefree NHS settings. The guidance explains the different types of e-cigarettes available, how batteries should be cared for and how the devices can be charged safely.

Read more in the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency Central Alerting System guidance on fire risk from personal rechargeable electronic devices.

Smokefree mental health trusts

In 2016, NHS England’s Five Year Forward View for Mental Health recommended that all inpatient mental health services should be smokefree in 2018. The government’s Tobacco Control Plan for England then set out a commitment to implement comprehensive smokefree policies, including integrated tobacco dependence treatment pathways, in all mental health services by 2018.

By April 2019, 82% of trusts that responded to a survey of mental health trusts in England had a fully comprehensive smokefree policy in operation.

There are 3 things that make a trust smokefree:

- every frontline professional discussing smoking with their patients

- stop smoking support offered on site or referral to local services

- no smoking anywhere in buildings or grounds

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has guidance on establishing smokefree policies and supporting patients to quit in mental health care settings.

A study evaluating the experience of 12 mental health wards before and after implementing the NICE guidance found:

- an increase in patients being offered smoking cessation advice

- a decrease in challenging behaviour incidents

- patients reporting positive changes in their smoking behaviour

- patients reporting motivation to maintain change after discharge

The most commonly identified barriers to smokefree policy implementation were:

- staff resistance

- patient resistance

- insufficient resources

- lack of senior management leadership

Stop smoking services in community mental health settings

An ASH survey of community-based mental health nurses and psychiatrists and local authority stop smoking services was carried out to gauge the level and quality of support available to smokers with mental health conditions living in the community.

It is important to note that this survey received 103 valid responses from mental health nurses representing 33 trusts, and 171 from psychiatrists representing 48 trusts. Therefore, the results should not be considered representative of all mental health clinicians or local authorities in England.

However, the survey found that additional action must be taken to ensure community mental health staff are equipped with the appropriate training and expertise they need to deliver very brief advice (VBA) and prescribe stop smoking medicines.

Watch Dr Mary Yates talk to Health Matters about smokefree NHS settings

Very Brief Advice (VBA)

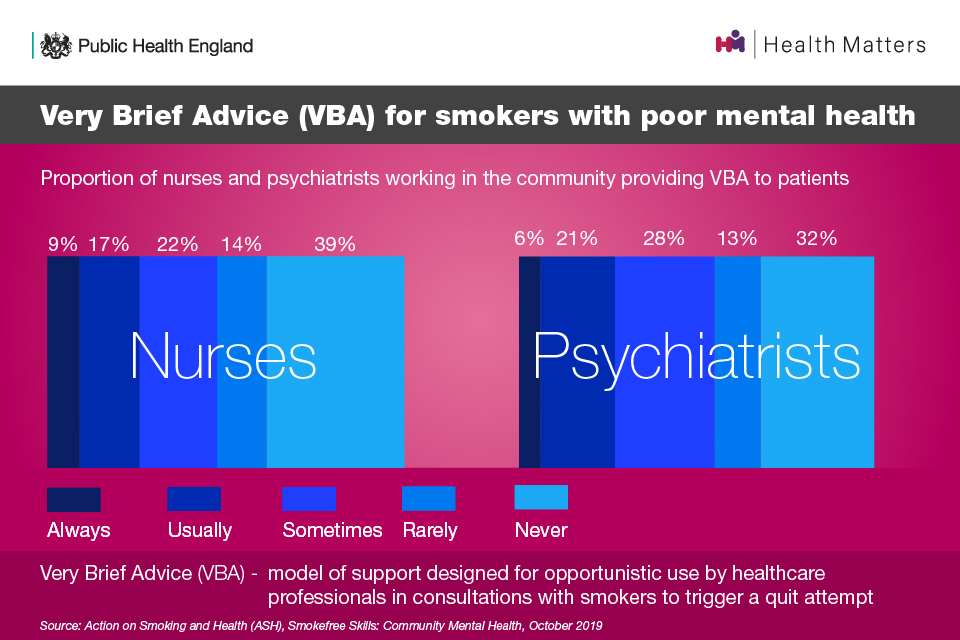

The survey found that:

- only around a quarter of respondents said that they ‘always’ or ‘usually’ use VBA

- the most frequent response was ‘never’, chosen by 39% of community mental health nurses and 32% of community psychiatrists

However, 88% of nurses and 85% of psychiatrists said that they both asked and recorded clients’ smoking status in line with the first step of the VBA model.

A free online training module on delivering VBA is provided through the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) or NHS Health Education England.

Training

The survey found that:

- only 58% of nurses had received any smoking cessation training

- only 43% of psychiatrists had received any smoking cessation training

This does not meet the NICE recommendation that trusts should ensure all frontline staff are annually trained in delivering stop smoking advice and referring patients to intensive support.

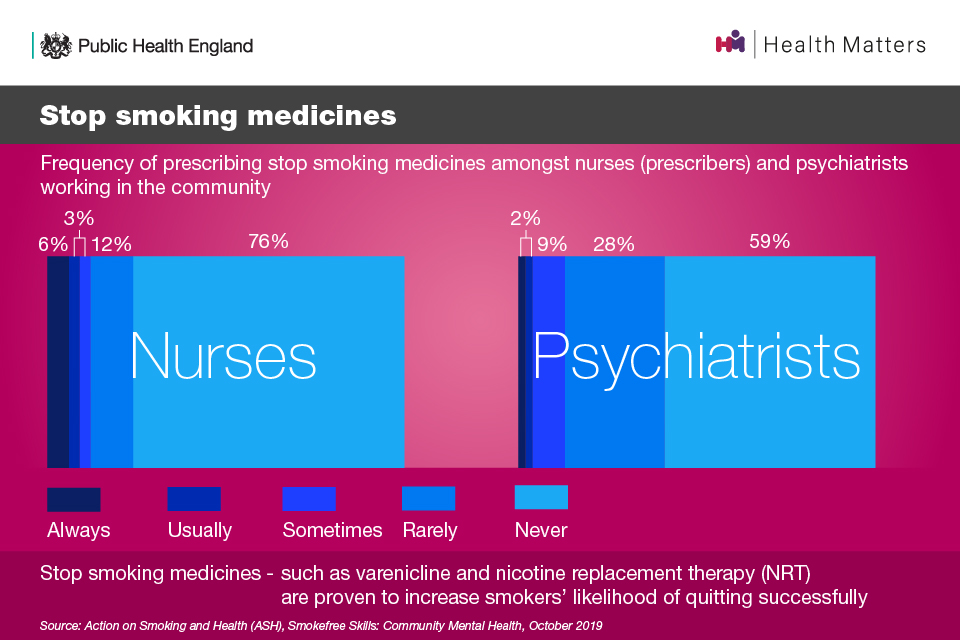

Prescribing stop smoking medicines

The survey also found that prescribing stop smoking medicines is not common practice among community mental health professionals:

- 76% of nurses who were qualified to prescribe said they ‘never’ prescribed stop smoking medicines

- 59% of psychiatrists said they ‘never’ prescribed stop smoking medicines

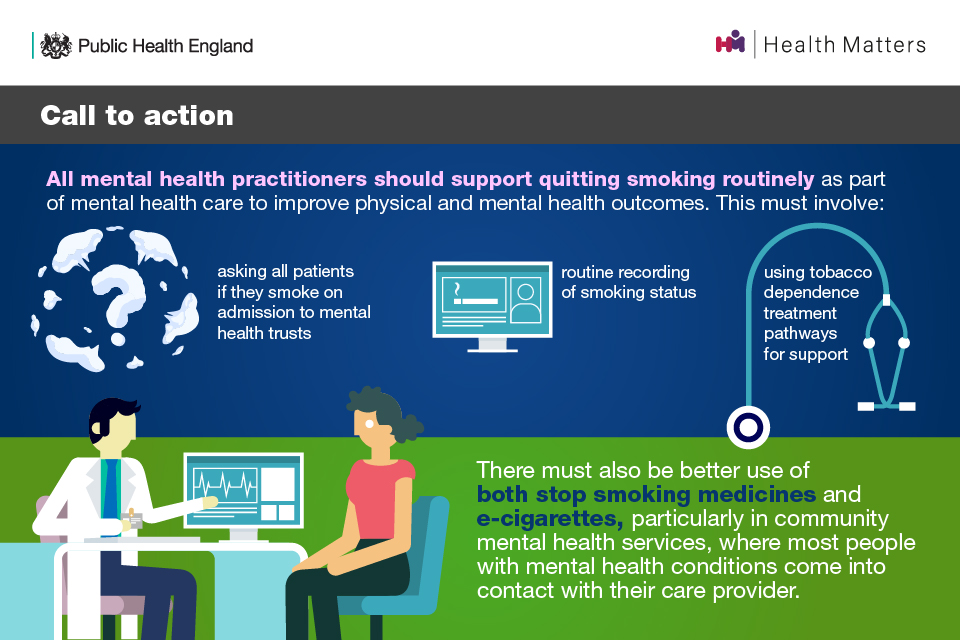

Call to action

All mental health practitioners

All mental health practitioners should support quitting smoking routinely as part of mental health care to improve physical and mental health outcomes. This must involve:

- asking all patients if they smoke and recording the data

- using tobacco dependence treatment pathways for support

There must also be better use of both stop smoking medicines and e-cigarettes, particularly in community mental health services where most people with mental health conditions come into contact with their care provider.

The Mental Health and Smoking Partnership has developed a suite of resources that can support health professionals in their role to reduce smoking among people with mental health conditions.

The NCSCT also provides a range of free online training materials including their mental health speciality module and briefings:

- Smoking cessation and smokefree policies: Good practice for mental health services

- Smoking cessation and mental health: A briefing for front-line staff

Mental health services

Importantly, all mental health trusts without a comprehensive smokefree policy in place should implement one as a matter of priority.

ASH’s report Smokefree skills: Community mental health highlights the need for community mental health professionals and stop smoking services to be properly resourced and trained.

To achieve this, there are several calls to action for NHS Trusts (although these go beyond inpatient settings and are relevant for all mental health services):

- ensure all frontline staff are trained in VBA on stopping smoking as part of NHS mandatory training (in line with NICE guidance)

- monitor uptake of VBA training amongst community mental health nurses and psychiatrists

- ensure that mental health professionals know how and where to refer patients to stop smoking support

- ensure that staff receive education and training about evidence-based interventions, including on e-cigarettes and stop smoking medications

- offer both combination NRT and varenicline to smokers, with behavioural support

- work with commissioners to seek adequate funding for the prescribing of stop smoking medicines in community mental health settings

Mental health trusts should also consider how best to use e-cigarettes in acute settings to reduce the harm of smoking. Where e-cigarettes are not available on site, trusts should consider taking steps to make them available.

Additionally, mental health service managers and smokefree leads should work with ward managers and staff to audit and eliminate the time spent by staff escorting patients on smoking breaks.

Read this edition’s case study on undertaken by Dr Gemma Taylor to design a smoking cessation intervention for people with mental health problems.

Dr Gemma Taylor speaks to Health Matters ###Local authorities

Local authorities are required to:

- work with mental health services to ensure that people with mental health conditions in the community can access appropriate specialist support to enable them to quit

- ensure there is a tailored evidence-based pathway for smokers with a mental health condition to access local stop smoking services

- ensure all stop smoking advisors have undertaken the mental health speciality course provided free through the NCSCT

Commissioners

PHE has guidance for commissioners on smoking cessation in secure mental health settings. Commissioners should encourage services to monitor and evaluate the impact of smokefree policies and this guidance includes some examples of good practice.

NICE’s public health guideline on smoking in mental health services can also be used by commissioners as it includes recommendations on commissioning smokefree secondary care services.

Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspectors

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) guide on smokefree policies in mental health inpatient services informs its inspectors on how to assess smokefree mental health trust policies in a consistent way.

It states that CQC inspections should not challenge smokefree policies, including bans on tobacco smoking in the services. Instead, the inspections should focus on whether such a ban is mitigated by adequate advice and support for smokers to stop or temporarily abstain from smoking with the assistance of behavioural support, and a range of stop smoking medicines and/or e-cigarettes.

Ongoing assessment of progress towards smokefree mental health services

Each finding from ASH’s Progress towards smokefree mental health services survey acts as a potential indicator for ongoing assessment of progress towards successful implementation of smokefree policy, locally and nationally.

These measures could be used, alongside national guidance from NICE, PHE and NHS England, in assessing progress:

- universal recording of patients’ smoking status on admission to acute mental health services (45% of trusts in 2019)

- the provision of treatment and behavioural support for tobacco dependence to inpatients of acute mental health services (93% of trusts in 2019)

- the offer within acute services of the choice of combination NRT or varenicline (47%)

- reduction of the frequency of smoking incidents within private bedrooms and adult mental health wards to less than once a week (52% of trusts in 2019)

- investment in stop smoking support within community mental health services (62% of trusts in 2019)