Are household formation decisions and living together fraud and error affected by the Living Together as a Married Couple policy? An evidence review

Published 6 July 2023

DWP research report no. 1031

A report of research carried out by RAND Europe on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2022.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at GOV.UK

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2023.

ISBN: 978-1-78659-532-4

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report summarises evidence on living together fraud and error (LTFE) and the social and economic context in which LTFE is embedded, with a view to informing DWP’s living together policy and its application to reserved GB benefits. LTFE refers to situations where a claimant has a partner but is receiving benefits as a single person (whether intentionally – i.e. fraud – or due to error). LTFE is a widespread issue in the UK, costing the taxpayer an estimated £760m per year.[footnote 1] The evidence review on which this report is based employed a literature search (quick scoping review) complemented by in-depth interviews with subject experts.

Although claims for Universal Credit (UC) are made on an individual basis, in couple households both partners’ circumstances are taken into consideration in determining the benefit amount. Reflecting the economies of scale associated with living with a partner, the couple rate is lower than the amount paid to single adults. DWP guidance on Living Together as a Married Couple (LTAMC)[footnote 2] is used by decision makers to assess whether unmarried adults living in the same household are a couple. UC payments are usually paid to one adult in the household, although under certain circumstances (e.g. domestic abuse) separate payments may be made to each partner.

An important finding from this evidence review is that there is little evidence on LTFE and how this is shaped by living together policy. Despite the lack of direct evidence, the wider literature points to factors that may affect or contribute to LTFE. Research suggests that living together policy may discourage some people from living with a partner (although there is scarce evidence on whether these factors also contribute to LTFE). Claimants may be concerned about the financial implications of being jointly assessed with a partner, for example whether their income will go down (reflecting the couple rate) and whether they will have full access to benefit income and control over how it is spent (particularly if UC is paid to a partner). However, conclusions about the effects of living together policy on claimant experiences and behaviour should be taken as indicative only, due to the lack of direct evidence on this topic.

Living together policy inevitably reflects assumptions and expectations about who will financially support each other, and in what circumstances. Certain principles underpinning living together policy may be out of step with the behaviour and preferences of some couples. For instance, living together policy is based on the idea that couples pool resources and that financial support in couples is coterminous with living together, but evidence suggests that, increasingly, couples choose to keep their income separate. However, there is a lack of direct evidence on how changing social norms and behaviours contribute to LTFE, so conclusions must remain tentative.

Drawing on the available evidence, this report considers whether there is scope to reform living together policy with a view to reducing LTFE. Reflecting the complexity of the issue and the lack of policy evaluations in this space, the policy discussion is descriptive rather than directive (i.e. no recommendations are made). Reducing reliance on household means-testing represents one option for reform, for instance by taking certain components out of UC and establishing them as separate, individual benefits. However, household means-testing is designed to target support to those most at risk of experiencing financial hardship (who are disproportionately adults living without a partner). Another policy option is to only take a partner’s income into consideration above a certain threshold of individual income. This would in effect mean that the couple rate for UC would only apply to those earning above this threshold. Widening the circumstances in which split payments can be used or making this the default might also help to address LTFE. Finally, it has been suggested that DWP could introduce a transition period in which couples do not have to undergo joint assessment. This would entail an initial period, for example the first six months that the couple is living together, when the partners can still be assessed individually if they choose to be.

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by DWP. Grateful thanks are owed to the following experts who took part in an interview (in alphabetical order): Dr Silva Avram, Fran Bennett, Dr Julia Carter, Professor Simon Duncan, Dr Michael Fletcher, Professor John Haskey, Professor Sue Himmelweit, Dr Rita Griffiths, Miranda Phillips, Professor Holly Sutherland. Thanks are also owed to RAND Europe colleagues Lillian Flemons and Lucy Hocking, for their helpful feedback on work produced for this study. All interviewees gave their permission to be named in this report.

The authors

Dr Madeline Nightingale, RAND Europe

Giulia Lanfredi, RAND Europe

Joanna Hofman, RAND Europe

Lucy Gilder, RAND Europe

Dr Chris van Stolk, RAND Europe

Glossary

Benefit error (claimant error): This refers to when a claimant unintentionally claims a benefit they are not entitled to – either because they have provided inaccurate or incomplete information or because they have failed to report a change in their circumstances promptly – but DWP assesses the claimant’s intent as having been not fraudulent.

Source: National Audit Office (2015)[footnote 3]

Benefit error (official error): This refers to when DWP pays the wrong amount because of a lack of action, delay or mistaken assessment by DWP, a Local Authority or Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs.

Source: National Audit Office (2015)[footnote 4]

Benefit fraud: This refers to when a claimant intentionally claims a benefit they are not entitled to, for example by deliberately providing false information or withholding information.

Fraud occurs when the following three conditions apply:

- the claimant does not meet basic conditions for receipt of the benefit or the rate of benefit

- it is reasonable to expect the claimant to be aware of the effect on their entitlement of providing incomplete or wrong information

- benefit is stopped or reduced as a result of DWP’s review

Source: National Audit Office (2015)[footnote 5]

Benefit unit (or unit of assessment): This refers to the unit that is used for the purposes of calculating benefit entitlement or payment; it could be a single claimant, a couple (joint claimants) or a household (joint claimants).

Source: UK Government (2013)[footnote 6]

Individualisation: A fully individualised means-tested social security system would have the following four main aspects:

- each person would have an individual right to claim financial support, and no one would be able to claim support simply as an adult dependent of another claimant

- assessments of financial need would take place on an individual basis, without taking into account the needs or resources of other adults in the family or household

- the award would cover the needs of that individual only and would not include any payments for adult ‘dependants’

- payments would be made to the individual, so that each individual adult would receive money in their own right

In technical terms, this means that the individual becomes the assessment unit, the resource unit and the payment unit.

Source: Millar (2004)[footnote 7]

Living together fraud and error: This refers to cases where a claimant declares to be single when they actually live with another person and maintain a joint household.

Source: DWP (2020)[footnote 8]

Means-tested benefits (or conditional benefits): This is a type of selective benefit (cash transfers and services limited to individuals or households with limited resources), access to which requires the DWP to check applicants’ resources (i.e. incomes, assets or both).

Source: Gugushvili and Hirsch (2014)[footnote 9]

Universal benefits (or unconditional benefits): These are cash transfers or services that are available to all citizens or residents or to large categories of citizens (e.g. pensioners) without a means-testing requirement or other form of selectivity. The term ‘universal’ encompasses some benefits that to do not go to everybody – they may be demographically targeted or dependent on prior contributions, without being specifically targeted at less well-off households.

Source: Gugushvili and Hirsch (2014)[footnote 10]

Introduction

This report presents findings from an evidence review conducted by RAND Europe on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) about household formation and LTFE in the UK and other OECD[footnote 11] countries.

Living together fraud and error

Benefit fraud is where the conditions for receipt of benefit (or the rate of benefit in payment) are not being met and the claimant can reasonably be expected to be aware of this.[footnote 12] The distinction between welfare fraud and error (Table 1.1) relates to whether behaviour is deliberate or reflects an unintentional mistake on behalf of claimants or officials. Welfare fraud and error can result in overpayment, reducing the money available for other government services, or underpayment, reducing the amount that claimants receive, potentially causing hardship and distress. [footnote 13] Both fraud and error create administrative costs for departments as they try to identify and correct errors.[footnote 14]

Table 1.1: Definitions of fraud and error in the welfare system

| Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fraud | People deliberately declare false information or withhold information in a claim |

| Claimant error | People mistakenly declare the wrong information in a claim |

| Official error | Departmental staff make mistakes when checking awards or do not respond quickly in processing information |

Source: National Audit Office[footnote 15]

The rate of overpayment and underpayment for all UK benefits and UC is shown in Table 1.2. Across all benefits, overpayment represented 3.9% of expenditure in 2021, compared with 2.1% in 2019. For UC, the overpayment rate was 14.5% in 2021, compared with 8.7% in 2019.

Table 1.2: Rate of fraud and error[footnote 16] (2019 to 2021), in terms of percentage of expenditures overpaid and underpaid

| Overpaid | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All benefits | 2.1% | 2.4% | 3.9% |

| Universal Credit | 8.7% | 9.4% | 14.5% |

| Underpaid | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All benefits | 1.1% | 1.1% | 1.2% |

| Universal Credit | 1.3% | 1.1% | 1.4% |

Source: DWP[footnote 17]

LTFE refers to situations where a claimant has a partner but is receiving benefits as a single person. LTFE was the third-largest reason for UC overpayments in 2020 and 2021, as illustrated in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Main reasons for Universal Credit fraud overpayments (2021)

| Total overpayments | Overpayments due to fraud | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-employed earnings fraud | 3.8% | 3.6% |

| Capital | 2.5% | 2.2% |

| Living together fraud and error | 2.0% | 2.0% |

Source: DWP[footnote 18]

UC overpayments related to living together were higher in 2021 than in 2020 (£760m compared with £215m), as illustrated in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Universal Credit overpayments due to living together fraud and error (2020 and 2021)

| Overpayments | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Amount | £215m | £760m |

| Percentage | 1.2% | 2.0% |

Source: DWP[footnote 19]

Living together policy

Although claims for UC are made on an individual basis, in couple households, both partners’ circumstances are taken into consideration in determining the benefit amount. Reflecting the economies of scale associated with living with a partner, the couple rate is lower than the amount paid to single adults.

The current DWP definition in legislation classifies couples living together as either:

- two people who are married to, or civil partners of, each other and are members of the same household

or

- two people who are not married to, or civil partners of, each other but are Living Together as a Married Couple

DWP guidance on LTAMC[footnote 20] is used by decision makers to assess whether unmarried adults living in the same household are a couple. UC payments are usually paid to one adult in the household, although under certain circumstances separate payments may be made to each partner. DWP’s living together policy is described in more detail in Chapter 3.

Research questions

The aim of this evidence review is to gather evidence on how the UK’s LTAMC policy affects LTFE and how this relates to such contextual factors as changing social attitudes, gender relations and patterns of household formation. While the review focuses on the UK context, where possible international evidence is used to locate the UK in an international perspective, drawing on examples from other OECD countries.[footnote 21]

This evidence review seeks to answer five research questions:

1. What are the prevailing attitudes and approaches to household formation in the UK and internationally (OECD countries)?

- Do these attitudes impact on the dynamic cycle of household formation and break up?

- Do these approaches impact welfare fraud and error rates?

2. How can a household or benefit unit be defined in social policy?

- What are the criteria for a stable or unstable household unit in the UK?

- What types of households are re-partnering in the UK?

- How does this compare with international policy (OECD countries)? Does this impact on welfare fraud and error rates?

3. What is the relationship between household composition and household finances?

- Is it shaped by socio-economic, geographical or age factors?

- How has this changed over time?

- How does this compare internationally (OECD countries)? Is this reflected in social policy?

4. What is the role of women in the household?

- Do women want, need or seek financial independence from male partners?

- Has this changed over time? And is this represented in UK and international social policy (OECD countries)?

- How does this impact on welfare fraud and error rates?

5. Does the living together policy affect partnering and cohabitation decisions? If so, how?

Methodology

This evidence review is based on a review of literature and in-depth interviews with experts.

Literature review

Two quick scoping reviews (QSRs) were conducted, one focusing on how to define the household or benefit unit for the purposes of social policy and the other on broader social and economic changes: household formation and composition, household finances and money management. QSR was chosen over more systematic approaches to evaluating evidence (i.e. systematic review, rapid evidence assessment) because of the broad scope of the research and the fact that critically appraising the evidence was not a key consideration for this study.[footnote 22] The choice of QSR was also informed by pragmatic considerations about the timeline of the research, which took place between November 2021 and March 2022.

The QSRs focused on sources published in English, relating to the UK or other OECD countries and published between 2011 and 2021. The search strategy is outlined in Annex 1. Additional sources were identified via snowballing,[footnote 23] including some highly relevant sources published prior to 2011. Additional targeted searches were conducted to follow up on areas of interest where fewer sources were identified from the structured search, for instance living together policies in other countries.

After being assessed against inclusion and exclusion criteria, data from included sources were input in a data extraction template in Excel (see Annex 1), enabling systematic analysis against key themes and questions.

In-depth interviews with experts

Interviews were conducted to complement the QSRs and fill any outstanding gaps in understanding of the LTAMC policy, its effects on LTFE or the role of contextual factors. A total of 10 interviews were conducted, in February and March 2022. Interview participants were selected among academic and policy experts in the field of household formation and welfare fraud in the EU and OECD countries. Two main approaches were used to compile a list of potential interviewees:

- literature-based approach: authors of key bibliographical sources deemed particularly insightful during the literature review phase were shortlisted as potential interviewees

- snowballing approach: interviewees were asked for recommendations of other relevant experts to approach to take part in an interview

The list of potential interviewees was approved by DWP before experts were invited to take part in an interview. A total of 10 interviews were conducted to enable data to be gathered from experts with differing backgrounds and expertise, within a small and specialised research community.

Interviews were conducted remotely via Microsoft Teams and lasted approximately 60 minutes each. Interviews were semi-structured to enable comparability while allowing some flexibility to tailor the discussion according to the interests and expertise of the individual. The topic guide for the interviews can be found in Annex 2. Interviews were recorded (with the interviewee’s permission) and the transcripts were analysed thematically.[footnote 24]

Strengths and limitations of this evidence review

This study brings together the available evidence on LTFE in the UK context, providing a novel synthesis of current knowledge. The review was conducted in a structured, comprehensive and transparent way, drawing on evidence published in the past 10 years. The report is informed by interviews with key experts who are leading research and policy analysis in this area.

A number of limitations to this methodology should be noted. While it takes a structured approach, a QSR does not follow the same levels of rigour as a systematic review or rapid evidence assessment.[footnote 25] It is possible that certain relevant sources were missed, particularly those published prior to 2011. The focus on English-language sources may, likewise, have resulted in certain findings being excluded. Although the review focused on the past 10 years, some sources may have been published (or draw on data published) prior to important policy changes, such as the introduction of UC in 2013. In terms of the qualitative research, the study draws on a relatively small number of in-depth interviews; different viewpoints or additional findings might have emerged if the pool of interviewees had been larger.

As an evidence review, the study is constrained by the nature of the evidence available on the topic of household formation and LTFE. Relatively few studies addressing LTFE directly were identified as part of this evidence review, and literature in this area is predominantly comprised of small-scale, qualitative studies. In addition, the evidence gathered approached policy analysis mainly from a theoretical point of view, and there is a lack of empirical studies and policy evaluations in this area. While these studies generate rich data and valuable insights, no impact assessments of living together policy were identified from which to draw causal inferences. Conclusions about the effects of living together policy on claimant experiences and behaviour should therefore be taken as indicative rather than definitive.

Structure of this report

Drawing on evidence from the UK and other OECD countries, Chapter 2 summarises the changing context in which LTFE is situated in terms of household formation and composition, household finances and money management. Chapter 3 focuses on UK policy and how the configuration of the benefits system may affect or contribute to LTFE. Informed by evidence from the UK and overseas, Chapter 4 considers policy options that might be used to address or mitigate LTFE. Chapter 5 draws out key implications of the findings for LTAMC policy.

The changing context of living together fraud and error

This chapter summarises evidence from the UK and other OECD countries on the social and economic context in which LTFE is situated, focusing on patterns of household formation and composition, households at risk of experiencing financial hardship, and the management of money within households, including gendered roles and expectations. The sociodemographic changes described in this chapter set the backdrop for living together policy and LTFE. However, it was not possible to identify any evidence to link these changes directly to the policy context. The data and evidence presented in this chapter are intended to add contextual insights rather than to draw direct lessons about LTFE and living together policy.

Patterns of household formation and composition

Increase in the number of adults living without a partner

Data from the past 10 years show an increase in the number of households in the UK, driven by a surge in the number of people living alone.[footnote 26] These trends are observed across EU member states too. The latest Office for National Statistics bulletin[footnote 27] on families and households[footnote 28] estimated that in 2020 there were 27.8 million households in the UK[footnote 29], representing a 5.9% increase over the previous 10 years. The average household size in the UK was 2.4 people. [footnote 30] Overall, the number of people living alone (single-person households) in the UK has been growing at a rate of 4% over the past decade. [footnote 31] A quantitative study focusing on demographic changes in the UK reported that the proportion of families with dependent children headed by a lone parent has tripled in the past 40 years.[footnote 32] Furthermore, an EU study from 2012 based on an analysis of the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey data found that the UK and Ireland had the highest rates of lone parents in the EU.[footnote 33]

Data by Eurostat[footnote 34] showed that during the decade 2010 to 2020, the total number of households in the EU increased by 7.2%. In 2020, the average household size in the EU was 2.3 people, and all member states recorded a decrease in the average number of persons per household in the past decade. Single-adult households (i.e. households consisting of only one adult, living with or without children) increased by 19.5% over the decade 2010 to 2020.

Table 2.1: Trends in household formation in the UK and EU (2010 to 2020)

| Household formation | UK | EU |

|---|---|---|

| Increase in the number of households (2010 to 2020) | 5.9% | 7.2% |

| Average household size (2020) | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Increase in single-adult households (2010 to 2020) | 4% | 19.5% |

Source: ONS[footnote 35] and Eurostat[footnote 36]

Fewer people are choosing to get married, and marriage occurs later in life

A trend that emerged clearly, both in the UK and in the EU, is the increase of cohabitation as a living arrangement. According to the ONS,[footnote 37] the share of unmarried adults living with a partner in England and Wales increased from 11.3% of the population aged 16+ in 2010 to 13.1% in 2020. However, ‘married’ or ‘in a civil partnership’ remained the most common partnership statuses in 2020, accounting for 50.6% of the adult population. In 2020, the highest number of people (in absolute terms) cohabitating without having been previously married or in a civil partnership in the UK was in the 16 to 29 years age bracket (1.98m people), followed by the 30 to 34 years age bracket (997,393 people).[footnote 38] A quantitative study[footnote 39] conducted in the EU based on census data found similar trends to the UK, estimating that in most EU member states, people aged 25 to 34 are most likely to choose cohabitation as a living arrangement.

The ONS estimated that, in 2020, the highest number of people cohabitating while having been previously married or in a civil partnership was in the 55 to 59 years cohort (248,535), followed by the 50 to 54 years cohort (201,569).[footnote 40] According to a quantitative study based on ONS data,[footnote 41] this is part of a broader trend that has seen a progressive move away from the ‘traditional’ family formation (i.e. the nuclear family of a married couple with or without dependent children) and the rise of ‘new’ family forms, such as cohabiting couple families, single-parent families[footnote 42] and blended families.[footnote 43] The same trend was identified also at EU level, mostly driven by changes in societal and family norms and economic contexts – as explained in a recent policy brief.[footnote 44] A qualitative study[footnote 45] exploring the meaning of ‘commitment’ in different types of relationships among a sample of young heterosexual women in the UK found that a committed relationship is not necessarily associated with marriage and that other relationship forms (such as cohabitation or living apart together) can involve equal, if not more, commitment. Nonetheless, research found that cohabitating couples are overall more likely to dissolve in comparison with married couples – as explored later in the chapter. Qualitative social research on social norms around partnership status found that in the UK, cohabitation has begun to take on new meanings, with other indicators of commitment, such as childbearing and shared housing, becoming more important than marriage in defining a relationship.[footnote 46]

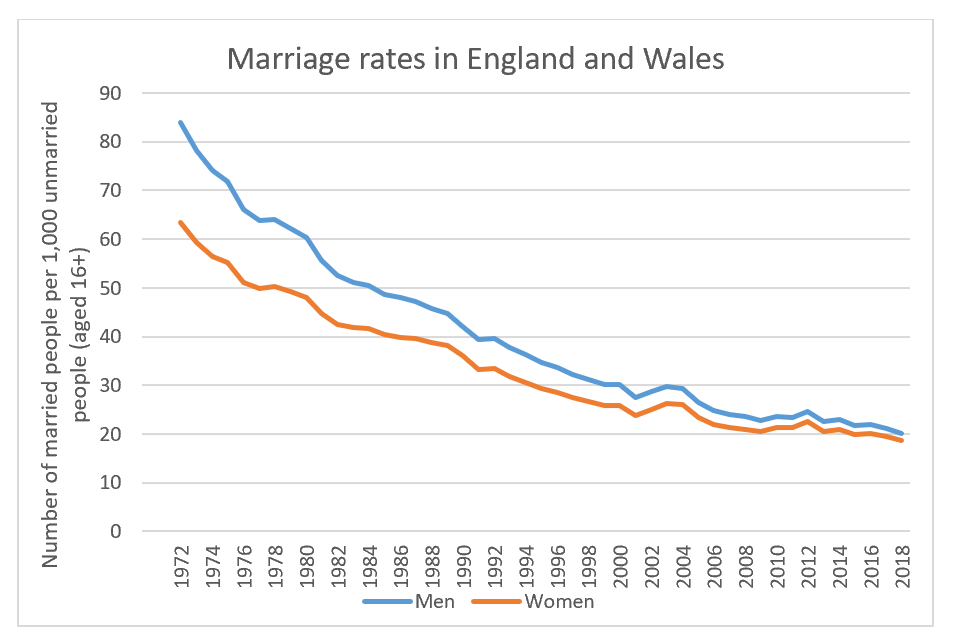

Figure 2.1: Marriage rates in England and Wales (1972 to 2018)

Source: ONS (2021)[footnote 47]

The other side of the rise in cohabitation is the decline of marriage − in terms of both the number of people getting married and the cultural role that this institution seems to hold. The British Social Attitude survey showed major changes in marital behaviour in Britain the past 30 years, with growing numbers of people not getting married or delaying this step.[footnote 48] A major trend associated with this phenomenon is couples choosing cohabitation as a precursor to marriage. When the British Social Attitudes survey began, in 1983, the majority of couples (7 out of 10) did not live together before getting married.[footnote 49] Nowadays, marriage without first living together is as unusual as premarital cohabitation was in the 1970s[footnote 50]: ONS data show that in 2018, 88.5% of men and women in opposite-sex couples cohabited before getting married.[footnote 51] A quantitative study on cohabitation and marriage in Britain found that the decline of marriage is especially prevalent among younger cohorts, as recent data from the ONS show.[footnote 52] In fact, Figure 2.1 illustrates how the overall number of married people in England and Wales has decreased over the past four decades. Similarly, a quantitative study[footnote 53] exploring the meaning of cohabitation across Europe through the analysis of the Generations and Gender Programme surveys found that most participants[footnote 54] were reluctant to prescribe a specific time point for marriage. This indicates that the sequence or timing of marriage is no longer normative in most European countries.

Research found that, overall, cohabitating couples in the UK are less stable than married ones. A quantitative study using data from the ONS Longitudinal Study on couples found that 82% of adults aged 16 to 54 who were married in 1991 were living with the same partner in 2001, while only 61% of those cohabitating 1991 remained with the same partner in 2001.[footnote 55] Among those who remained with the same partner, around two thirds had converted their cohabitation to a marriage by 2001.[footnote 56] These figures are consistent with an analysis based on the first wave of the Generations and Gender Programme surveys (2004 to 2011): in the UK, nearly 40% of individuals whose first union was a cohabiting relationship not leading to marriage have dissolved their union.[footnote 57] The percentage of couples dissolving their partnership then drops to slightly more than 10% for individuals who cohabited before marrying, and to less than 10% for those whose first union was a marriage (not preceded by cohabitation).[footnote 58] A study by the Centre for Population Change, based on the Understanding Society Survey, explained that instability of cohabitation is mostly attributed to the sociodemographic circumstances of the couple in this arrangement.[footnote 59] In fact, cohabitants, on average, are younger and have lower incomes − both characteristics that are associated with a higher risk of partnership instability.[footnote 60] For example, data from the The Way We Are Now survey, conducted in the UK in 2016, showed that the biggest external strain on relationships is financial worries, with 26% of respondents experiencing this pressure.[footnote 61]

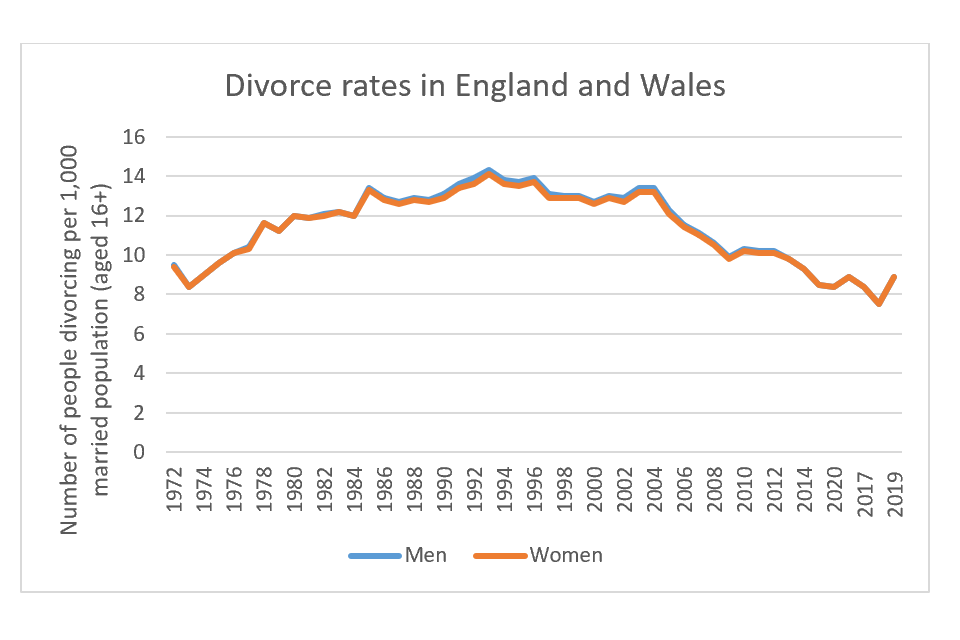

Figure 2.2: Divorce rates in England and Wales (1972 to 2019)

Source: ONS (2020)[footnote 62]

Note: The ONS dataset provides only disaggregated data for men and women.

The greater dissolution of cohabitating couples is among the reasons that explain why, overall, divorce rates are declining. A quantitative study based on the National Survey of Family Growth in the USA argued that the dissolution of a cohabitating union is, in many ways, an ‘averted divorce’.[footnote 63] This explanation is in line with trends identified in England and Wales by ONS data, where divorce rates have been declining since the early 2000s, as compared with the 1980s and 1990s (Figure 2.2). In older cohorts, people would have faced stronger societal pressures to marry, and these people experienced the same relationship problems that led to marital dissolution.[footnote 64] The pressure to marry has decreased, and people are more likely to cohabit if they are not strongly interested in marriage.[footnote 65] This is visible in ONS data (Figure 2.1), which show that the UK marriage rate has been steadily decreasing since the 1970s.

Consistent with the trends described above, the number of children born out of wedlock or from single parents is on the rise. Data from ONS shows that births outside of marriage in the UK went from 39.5% in 2000, to 46.8% in 2010, to 49% in 2020.[footnote 66] Similarly, in the EU, the proportion increased from 27.3% in 2000 to 42.6% in 2016.[footnote 67] The British Social Attitudes survey observed a concurrent change in social and cultural attitudes.[footnote 68] In 1989, 71% of people agreed with the statement “people who want children ought to get married” and 17% disagreed. In 2013, only 42% agreed, while 34% disagreed with the same statement. A more recent edition (2020) of the British Social Attitudes survey reported that between 1996 and 2017, the proportion of dependent children living in cohabitating households rose from 7% to 15%, and slightly more than one fifth lived in lone-parent families in 2020.[footnote 69]

Research has shown that a growing number of couples in the UK decide to live apart while being together (in a relationship) – especially among the older and higher-income cohorts. This arrangement is in line with the rise of ‘new’ family formations over ‘traditional’ ones. A mixed methods study exploring the living apart together (LAT) phenomenon[footnote 70] explained that a new relationships paradigm is emerging and that family life is no longer equated with the married couple.[footnote 71] Among the reasons mentioned for deciding to live apart while in a relationship, 31% of participants in a mixed methods study conducted in 2013 said that they live apart because the relationship is at an early stage and they do not feel ready to cohabit yet.[footnote 72] At the same time, 30% of participants expressed a preference for not living together due to wanting to keep their own home, prioritising other responsibilities over the relationship (including own children), and ‘just not wanting to live together’.[footnote 73] Furthermore, 12% reported geographical constraints, such as their partner having a job or studying elsewhere or living in an institution (i.e. a nursing home or prison).[footnote 74] The active decision to live apart while being together seems to be perceived as holding considerable benefits, especially among older cohorts.[footnote 75]

A review of the literature[footnote 76] on couples found that among the main advantages of this arrangement is an increase in autonomy for women (who in this way can avoid being burdened with additional unpaid domestic work); the enhanced ability to manage relationships with own children, parents and friends; and the reduced risk of asset depletion in the face of a relationship breakdown. This last element was identified by another study (based on the analysis of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics survey) as the main reason why 73% of the older (over 45), previously married cohort in Australia had made a definite decision to live apart.[footnote 77] Further quantitative research conducted in the UK on the phenomenon found that older individuals and those who have experienced divorce or widowhood are more likely to be in a LAT union than married, mostly for reasons of independence.[footnote 78] Conversely, younger people are more likely to say that they are not ready to live together.[footnote 79] Overall, though, living apart seems to be less feasible for low-income couples, because having fewer financial resources makes it a necessity to share household expenses (i.e. housing, food, bills), and the term LAT itself seems to be associated more with the middle class.

Decisions about household formation and composition are partly influenced by economic and financial factors

This section presents evidence on how economic and financial factors have been found to play a role in shaping decisions on household formation. This is especially relevant in the context of the LTAMC rule discussed in Chapter 3, which determines that two individuals living together (in a sexual and romantic partnership) are to be assessed jointly for benefit purposes.

In some European countries, the high social and economic cost of divorce acts as a deterrent to the dissolution of households. One quantitative study found that in Italy and Poland, both characterised by strong (Catholic) religious views, the process of getting a divorce is often lengthy and expensive, and this discourages couples from taking this path.[footnote 80] Another element that acts as a deterrent is women’s economic dependence on men, which results in some women struggling to separate from their spouse due to a lack of means to support themselves financially.[footnote 81] For these reasons, separation is more than just a short-term transition to divorce, as many separated couples avoid official divorce proceedings and remain legally married despite being de facto separated.[footnote 82] All these factors figure as drivers of low divorce rates.

Living in a welfare state influences marriage and fertility rates, due to the ways in which public policies (i.e. benefits, tax deductions) provide financial support to families. A quantitative study of OECD countries found that the amount of public social spending in support of families has an impact on trends of family formation.[footnote 83] For example, living in a generous welfare state (i.e. a welfare state with larger public social spending) increased both marriage and divorce rates, with a stronger effect on the former.[footnote 84] The research also found a positive association with fertility rates, especially among non-married couples. The authors’ argument is that this association happens because welfare states tend to subsidise births by providing benefits and tax deductions in support of families with children. The authors also explained that welfare states take on some of the financial burden of the support functions that would traditionally be provided within the family − such as care for children and older people, and support in case of unemployment and illness. Consequently, they concluded, welfare states support family formation.[footnote 85]

Conversely, when insufficient support is provided by the state, intergenerational households can afford protection from financial hardship. Quantitative research conducted in the EU and the USA shows that, while in the past households composed of multiple generations were meant to provide care for their elders, now families that choose this living arrangement tend to do so to draw on the financial support their elders can provide.[footnote 86] In fact, this type of co-residence is generally opted for by groups that experience socio-economic disadvantage. It is also more prevalent among women, the widowed, those with lower education, those without paid employment and those from a migrant background. In Romania, for example, the decision to live with grandparents as a coping strategy for financial hardship is driven by two factors: (i) the high number of parents who have migrated abroad for work and have left the extended family to look after their children; and (ii) the system of social assistance benefits being largely tied to earnings, which therefore favours middle-class working parents.[footnote 87] Thus, lower-income and jobless families, as well as those with irregular work histories, tend to rely more on relatives for financial support.[footnote 88]

Financial considerations also influence decisions about cohabitation. A mixed methods study exploring the phenomenon of intermittent cohabitation in the USA reported that women in this arrangement did so primarily for practical motives.[footnote 89] In particular, the financial dimension was found to be particularly important for mothers, who often decided to cease cohabitation if a partner no longer contributed adequately to the household, regardless of romantic feelings.[footnote 90] Similarly, housing policy was found to strongly determine mothers’ ability to cohabit.[footnote 91] The article explained that public housing vouchers in the USA generally include only the mother and her children, and there are specific provisions regulating who else is allowed to stay in the home. Therefore, mothers reported undergoing involuntary separations when they felt under scrutiny, for fear of losing the entitlement.[footnote 92] Housing benefits in the UK are now part of UC, but one interviewee remembered encountering a similar situation when conducting research on housing benefits under the ‘legacy’ system.[footnote 93] They mentioned the episode of a woman whose husband was posted overseas and was not financially supporting her. She was therefore on housing benefits. When he came home, he could not stay at his parents’ house, though, and ended up staying with his wife, who was later prosecuted for benefit fraud.

Households at risk of experiencing financial hardship

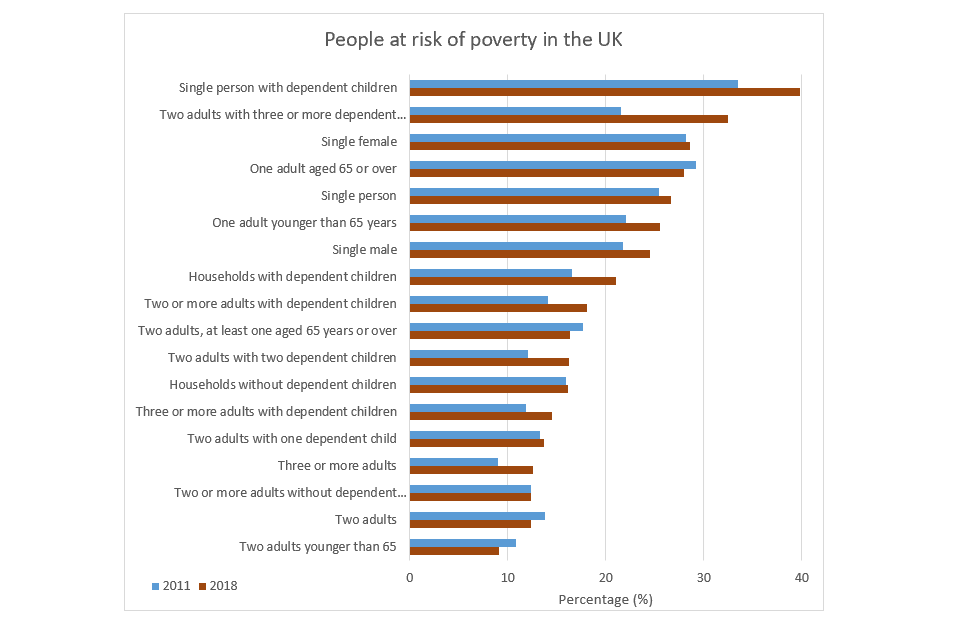

Figure 2.3: Rate of people at risk of poverty in the UK, by household type (2011 and 2018)

| 2011 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Single person with dependent children | 33.5% | 39.8% |

| Two adults with three or more dependent children | 21.5% | 32.5% |

| Single female | 28.2% | 28.6% |

| One adult 65 years or over | 29.2% | 28.0% |

| Single person | 25.4% | 26.7% |

| One adult younger than 65 years | 22.1% | 25.5% |

| Single male | 21.8% | 24.5% |

| Households with dependent children | 16.5% | 21.0% |

| Two or more adults with dependent children | 14.1% | 18.1% |

| Two adults, at least one aged 65 years or over | 17.7% | 16.3% |

| Two adults with two dependent children | 12.1% | 16.2% |

| Households without dependent children | 15.9% | 16.1% |

| Three or more adults with dependent children | 11.9% | 14.5% |

| Two adults with one dependent child | 13.3% | 13.7% |

| Three or more adults | 9.0% | 12.6% |

| Two adults | 13.8% | 12.4% |

| Two or more adults without dependent children | 12.4% | 12.4% |

| Two adults younger than 65 years | 10.8% | 9.1% |

Source: Eurostat (2022)[footnote 94]

Adults living without a partner (alone or as a single parent) face an elevated risk of poverty

Quantitative evidence shows that poverty is concentrated in smaller households, such as single-person households (especially single pensioners) and single-parent households (especially single mothers) (Figure 2.3).[footnote 95] [footnote 96] [footnote 97] [footnote 98] Couples, with or without children, on the other hand, are less exposed to the risk of poverty.[footnote 99] According to a recent study, this is partly due to the way in which welfare provision is directed at families with children, leaving single-person households with less support from the state.[footnote 100] Furthermore, experts interviewed as part of this study pointed to the fact that living together provides some financial advantages, such as sharing housing costs and economies of scale. Quantitative research found that in all European Union countries,[footnote 101] the relative risk of a child being poor is higher in lone-parent households (47% of families in this group are at risk of poverty) than in two-parent households (21% of families in this group are at risk of poverty).[footnote 102] However, solo living is more strongly associated with poverty in Nordic and north-western European countries (including the UK) compared with eastern and southern European countries.[footnote 103] According to Eurostat data from 2017, the UK had the third highest number of single adults with dependent children at risk of poverty in the EU (almost 60%), behind Bulgaria and Ireland.[footnote 104] Additionally, the risk of experiencing income poverty is more strongly positively associated with having two or more children in the household (rather than one), as well as with the lone parent being single or separated (rather than widowed or divorced), the single parent being a woman (rather than a man), not having upper secondary education, and not being in full-time employment.[footnote 105] [footnote 106]

Female poverty stands out as a relevant pattern across Europe. Results from a multilevel regression study showed that children are significantly less likely to be poor if they live with lone fathers rather than with lone mothers, everything else being equal.[footnote 107] A quantitative study conducted in the UK confirmed this pattern, and illustrated that 60% of lone mothers experience poverty, versus 30% of lone fathers.[footnote 108] Furthermore, as shown in Figure 2.3, single female adults are, overall, poorer than single male adults in the UK.

The configuration of the benefits system can also contribute to financial hardship

Households relying on benefits in the UK may be exposed to financial hardship due to the practical implications of policy design. A mixed methods study exploring the provision of UC in the UK found that this benefit was not designed to reflect changes in family circumstances in a dynamic way.[footnote 109] Entitlement to UC depends on the income and earnings of both members of a couple (for as long as they cohabit) and on family needs and costs (i.e. housing and childcare). This makes it more difficult for claimants to budget for the upcoming month if they have experienced a change in family circumstances. Low-income families, though, often face multiple and unexpected alterations in type or amount of income, housing costs and household composition – which all have an impact on the amount of payment they are entitled to receive. Some of these changes are inherently short-term and unstable, such as children in separated families living at intermittence with either parent, and the system is slower to adapt to variations in terms of family composition, in comparison with variations of other circumstances (i.e. wages) – as the report explained:

With UC monthly assessment, if claimants report a change of circumstances before their assessment date, it will apply for the whole of the month prior to that date. Hence UC is likely to be more responsive to wages (via the Real Time Information system) than other changes, and so may be unpredictable, making it more difficult for claimants to budget. UC was intended as a ‘dynamic’ benefit in relation to the labour market, focused on changing ‘pro-work social norms’, rather than dynamic in relation to family circumstances.”[footnote 110]

In fact, as described in Chapter 3, UC inherited the household as the unit of assessment from the previous, ‘legacy’ system.

Gender equality and household income

Increasingly, couples choose not to pool all financial resources

Social research has found that the ‘unitary model’ of the household (see Box 2.1) is no longer well aligned with people’s preferences and behaviour in terms of managing household finances. According to an EU-level study based on EU-SILC data, a significant proportion of adults reported keeping at least some of their personal income separate from that of their partner, and overall fewer than half (45%) of households were fully pooling resources.[footnote 111] Similarly, data from the 2012 Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey in the UK showed that 49% of couples pooled and managed finances jointly (with a further 15% pooling some of the money and keeping the rest separate), and 23% stated that one member of the couple is responsible for all the household money except for the other partner’s personal spending money.[footnote 112]

Quantitative evidence also showed that, although the majority of couples do not pool all their income, the unitary model (see Box 2.1) is still more likely to be true for couple households (compared with other types of multi-person households).[footnote 113] Furthermore, a traditional division of work between spouses (where the man is the sole breadwinner and the woman is a full-time homemaker) increases the likelihood of full income pooling, while dual‑earner couples and unmarried couples are less likely to report full income pooling[footnote 114] [footnote 115] (even more so when the woman’s earnings represent more than 30% of the couple’s earnings[footnote 116]). Other factors positively associated with full income pooling for couples are having dependent children together, being retired (suggesting a generation effect but also, perhaps, signalling lower incomes), being in a long-term relationship and being from older demographic cohorts.[footnote 117] [footnote 118] In contrast, people who are financially tied to other households (e.g. blended families[footnote 119]) are less likely to pool resources, as are higher-educated and higher-income couples, and couples in the early stages of their relationship.[footnote 120] [footnote 121]

On the whole, research estimated that, considering the trends of decreasing marriage and increasing cohabitation, as well as the increasing proportions of dual-earner couples,[footnote 122] the share of ‘full pooling’ households is likely to continue decreasing.[footnote 123] as one interviewee pointed out, socio-cultural norms around finances are becoming increasingly more individualised, and overall, at societal level, there is a greater desire for individual resources, even when people are part of a couple.

Box 2.1: Economic models explaining the division of household finances

Economic theory has identified two major ways in which people who are part of the same household use their financial resources to support their living.

- The unitary model[footnote 124]: In this approach, the household is assumed to behave as a single entity, a rational consumer maximising a unique utility function under a single budget constraint. For households to function ‘as if’ they were individuals, two main assumptions have to be met: (i) individual preferences have to converge, so that the household can be considered a single decision unit; and (ii) household members’ resources have to be pooled and (enhanced by economies of scale) subjected to only one budget constraint. The fact that individuals’ preferences may diverge is overlooked, and issues of intra‑household distribution (i.e. inequalities among members of the household) are bypassed. Individuals are not discernible within the household, which operates as a ‘black box’. No account is taken of the possibility that some members of the family are rich while others are poor. Individuals’ economic well‑being is conventionally measured on the basis of household-level information and is assumed to be the same for all household members.

- Alternative, non-unitary models[footnote 125]: Non‑unitary models consider that each household member (most models consider two decision makers) has their own utility function, and incomes are not assumed to be pooled. Estimating these models, though, is also quite complex and not easy to operate for statistical purposes. There seems to be consensus that applying a unitary model logic overlooks inequalities present within the household (in terms of distribution of resources) but that operationalising alternatives is not a simple task. For example, understanding how and to what extent resources are pooled requires an in-depth understanding of the individual household situation, which is not always attainable with statistical computations.

Women are more concerned than men about autonomy and independence around household finances. Both the literature and interviews highlighted that pooling income into a joint bank account does not necessarily entail joint management of finances or equal power.[footnote 126] For example, a quantitative study examining intra-household distribution of consumption in 12 countries found that equal sharing rarely happens, creating gender inequality in consumption and poverty, with men benefiting from a larger share of resources.[footnote 127] Abusive partners may also force their partners to use a joint bank account, and this financial dependence can prevent the victim from seeking support or make it more difficult for them to do so.[footnote 128] Overall, qualitative research found that women seem to value the access to an independent income more, either from wages or benefits, as compared with men.[footnote 129] This reveals a desire for individual control over financial decision making within the household, and for being able to spend money in autonomy without having to justify this to a partner.[footnote 130] Qualitative research found that women in low-income households in the UK expressed a preference to maintain a certain degree of autonomy from the partner.[footnote 131]

UK policy and living together fraud & error

This chapter introduces DWP’s living together policy and summarises the evidence on how this policy may affect LTFE.

Defining the household or benefit unit

The UK relies to a great extent on household means-testing

Welfare systems in different countries rely on targeted (rather than universal) benefits to varying degrees,[footnote 132] and they take different approaches to this. The unit of assessment (or benefit unit)[footnote 133] can be an individual or a household.[footnote 134] In most OECD countries, the unit of assessment is the household or the family, usually defined in terms of the nuclear family, i.e. the spouse or partner and any dependent children.[footnote 135] However, there are different ways of defining the household or family for the purposes of social policy. In some OECD countries (Austria, Japan and Luxembourg), other non-dependent adults who live together (i.e. those who do not have a romantic or sexual relationship) form part of the benefit unit.[footnote 136] In some OECD countries (Austria, Germany, Japan and Switzerland), financial support from family members outside the household – parents, grandparents and even siblings – is taken into account when determining the level of benefit.[footnote 137] This cross-national variation reflects assumptions and expectations about who will financially support each other, and in what circumstances. Within the same country, the unit of assessment may differ across different types of benefits. This is the case in the UK, which, as described by one interviewee, does not have – and has never had – a single benefit unit; it varies across different benefits. However, the introduction of UC in the UK means that a larger proportion of social welfare is directed towards a single benefit unit.

This evidence review identified relatively few sources addressing LTFE in countries other than the UK. LTFE may be less prevalent, or the issue may be less high on the policy plan in countries where there is greater reliance on contributory benefits and means-tested welfare occupies a more residual position (there is less scope for LTFE where there is greater reliance on the household as the unit of assessment). Administrative factors, such as the existence of comprehensive population registers (which do not exist in the UK), may also make LTFE less prevalent in other countries, although this could not be established from the literature. The emphasis placed on LTFE in the UK may also reflect the relatively large number of single-parent households in the population.[footnote 138] [footnote 139] International evidence is predominantly drawn from Australia and New Zealand (see Box 4.2 and Box 4.3: in Chapter 4), two countries which share with the UK a strong emphasis on means-tested welfare.

In the UK, a key element of targeting is the household means-test, which has come to occupy a more central position in the benefits system over time.[footnote 140] The rationale for targeting based on household income is to direct resources at those most at risk of experiencing financial hardship. Targeting based on household income also accounts for economies of scale associated with living with a partner.

Unmarried couples form a single benefit unit if they are Living Together as a Married Couple

Under the current system, UC claims are made by individual claimants, and, where relevant, this claim is linked to a claim from a partner. In couple households, both partners’ circumstances will be taken into consideration when determining the benefit amount.[footnote 141] For the purposes of assessing eligibility for UC, DWP guidance[footnote 142] states that two people should be considered a couple if they live in the same household and are one of the following:

- married to each other

- civil partners of each other

- living together as if they were married

DWP guidance states that the household should be given “its normal everyday meaning … It [the household] is a domestic establishment containing the essentials of home life”.[footnote 143] According to this guidance, members of a household share a dwelling,[footnote 144] and both members should live there regularly. In addition to sharing a dwelling, other factors that may be considered in assessing whether individuals form a joint household include:[footnote 145]

- the circumstances in which the two people came to be living in the same house

- the arrangements for paying for the accommodation

- the arrangements for the storage and cooking of food

- the eating arrangements (whether separate or not)

- the domestic arrangements, such as cleaning, gardening and minor household maintenance

- the financial arrangements (who pays which bills? is there a joint bank account? whose name is shown on utility bills?)

- evidence of family life

If they are not married or in a registered partnership, two individuals who are members of the same household need to be LTAMC to be considered a couple and therefore subject to joint assessment.[footnote 146] The LTAMC rule (known until 2005 as Living Together as Husband and Wife) exists to ensure that people who are living together and not married are not treated any more favourably than people who are married (see Box 3.1). The term Living Together as a Married Couple is not defined in legislation.[footnote 147] Decision makers must determine on the basis of available evidence whether the relationship of two people who are not married to each other is comparable to that of a couple who are married.

The LTAMC definition is complex because it considers several different dimensions, not all of which have to be present. According to the guidance,[footnote 148] “Marriage is where two people join together with the intention of sharing the rest of their lives. There is no single template of what the relationship of a married couple is. It is a stable partnership, not just based on economic dependency but also on an emotional relationship of lifetime commitment rather than one of convenience, friendship, companionship or the living together of lovers”. Various characteristics of the relationship may be considered, including mutual love, faithfulness, endurance, interdependence and devotion.[footnote 149] Other factors taken into consideration are the management of household finances (“in most marriages it would be reasonable to expect financial support of one partner by the other, or the sharing of household costs”), the stability of the relationship (including whether such activities as shopping, cooking, cleaning and caring are undertaken jointly), having children, public acknowledgement of the relationship (for instance, in claiming benefits, from friends or family members or sharing a surname) and shared plans for the future.[footnote 150] A signed statement or letter from the claimant that they are LTAMC or intend to marry or enter into a civil partnership is considered sufficient evidence of LTAMC.[footnote 151] Due to the complexity of the LTAMC policy, claimant guidance refers simply to “a partner moving in”.

Box 3.1: Historical evolution of the cohabitation rule

The LTAMC policy has been in effect since 2005. Prior to this date, a similar policy existed, known as Living Together as Husband and Wife (LTAHAW), dating back to 1977. Following the introduction of civil partnerships, in April 2005, the LTAHAW rule was further extended to same sex couples and renamed to reflect gender-neutral language.

Source: Griffiths (2016)[footnote 152]

Continuity between Universal Credit and the ‘legacy’ system

The emphasis on household means-testing in the current UK benefits system is not new. UC – introduced in 2013 – replaced six means-tested benefits.[footnote 153] Although it represents a radical change in creating a single, unified system, UC maintains the focus on the household as the unit of assessment. In the words of one interviewee, “fundamentally, the way in which a household unit is conceived [in UK social policy] hasn’t changed”. The rule is the same under UC as it was under the previous, ‘legacy’ system. However, one notable change under UC is that benefit is paid to one adult on behalf of the household by default. Split payments are possible in certain circumstances (domestic abuse, serious financial mismanagement), but these alternative payment arrangements (APAs) are used infrequently, and generally are only on a temporary basis.[footnote 154]

Implications of the benefit unit for living together fraud and error

There is relatively little research on the topic of living together fraud and error

Only two of the sources identified in this evidence[footnote 155] [footnote 156] review describe living together fraud or welfare fraud.[footnote 157] Other sources acknowledge that the phenomena they describe could contribute to what would for official purposes be deemed fraud but state that evaluating or assessing this falls outside their remit.[footnote 158] Other sources reject the term fraud on the grounds that such behaviour is often inadvertent or accidental (i.e. error)[footnote 159] or that the discussion around welfare fraud often fails to recognise the complex reasons why it occurs.[footnote 160] One interviewee acknowledged that this can be a grey area: people may deliberately downplay the existence or seriousness of their relationship, but this does not constitute fraud if they genuinely maintain separate households:

I wouldn’t call it fraud, because if somebody is living in a separate household, then that isn’t fraud. It [fraud] is only when partners are living there, quite clearly, and don’t have alternative households and so on. So, in terms of those unintended consequences of women living apart from the partner, I would call it ‘living apart together’, which is what it’s called in the sort of middle class, well not just in the literature. But people do it right throughout the income spectrum, don’t they, but it’s called different things depending on whether you’re claiming benefits or not, so I wouldn’t call it fraud.

The distinction between fraud and error also constitutes a grey area. In practice, it may be difficult to distinguish between deliberate actions and inadvertent mistakes and misunderstandings (which is why this report refers to ‘living together fraud and error’ rather than ‘living together fraud’).[footnote 161] Despite the lack of direct evidence on welfare fraud, the literature points to mechanisms that may plausibly affect or contribute to LTFE. It is important to recognise, however, that these relationships are often not directly tested or evaluated. Conclusions about the effects of living together policy on claimant experiences and behaviour should be taken as indicative rather than definitive.

The couple rate may create financial disincentives to living with a partner

The couple rate (i.e. the lower benefit rate paid to claimants living with a partner compared with those who are single), means that some households may be worse off financially if they live together compared with if they live apart. According to analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies[footnote 162] the majority of couple households in the UK (68%) would be better off if they were living apart,[footnote 163] rising to 95% of couples with children. However, another study (which takes into consideration economies of scale associated with living with a partner) suggests greater variation in the financial implications of living together as a joint household.[footnote 164] This source finds that financial disincentives to living with a partner are greater for working families (particularly dual-earner families) compared with families where both partners are unemployed or economically inactive.[footnote 165] However, there is a lack of up-to-date evidence on the financial implications of living with a partner (and how this is shaped by the benefit system). The two studies cited above were published in 2010 and 2012, prior to the introduction of UC. Compared with the previous system, UC is designed to direct more resources to couples (particularly those with children) relative to single adults.[footnote 166] A large proportion of couple households with children have seen an increase in their entitlement under UC compared with the previous system.[footnote 167] In light of this, further research is needed to establish whether there are financial disincentives to living with a partner under UC.

Regardless of the economic realities, research highlights a perception among benefit claimants that they may be worse off living with a partner compared with living alone.[footnote 168] [footnote 169] [footnote 170] Griffiths found that the expectation of loss or reduction in entitlement to benefits associated with moving in with a partner could deter low-income mothers from taking this step.[footnote 171] Some women who took part in this research study commented that they would be worse off financially under joint assessment with a partner compared with living as a single mother. In the words of one of claimant interviewed as part of this research study:

I work part time and … get Working Tax Credits … Housing Benefit and help towards childcare costs.… That gets me by.… I’d lose all that if I moved in with him.… We’d have to live on his wage if we were living together … we’d have hardly anything to live on.… We struggle as it is … so we just can’t do it at the moment”. (Miriam, 23, one child aged 18 months)[footnote 172]

Financial support may extend beyond couple relationships, and couples may share resources and support one another financially even if they do not live together. Claimants interviewed as part of one study commented on how economies of scale may be present in other types of households that are not considered to form a benefit unit and subject to joint assessment.[footnote 173] In the words of one claimant interviewed by Griffiths et al.:

[When we first moved in together] I wasn’t entitled to Universal Credit at all, but I was when I was living with my parents, so that made no sense to me.… I don’t get, like, why people who live with their parents are entitled to it, more than … someone who lives with their partner … because when you live with your partner … he shouldn‘t be, like, fully, like, responsible for me because we’re living together”. (Isla, joint claimant, female, Cumbria, single-earner couple, two children)[footnote 174]

Interviewees discussed the possibility of couples who are LAT (who are not considered to form a household for the purposes of joint assessment) financially supporting one another. LAT couples may be considered couples according to other aspects of a relationship considered by decision makers, for instance public recognition of the relationship:

Most people living apart together in our sample wouldn’t be seen as living together in those terms. Some of those terms would apply, like being recognised by others, or acting as a sort of couple in a social sense. But of course most of them had different houses and different bank accounts and that sort of thing.

Financial support may also be offered by other (resident or non-resident) adults, such other family members, particularly in more complex family forms:

Extended families living within a single domestic unit might provide … financial support for a nuclear family within that that’s not recognised by the system at all.

Research highlights low awareness and understanding of the rules around cohabitation and benefit entitlement. Qualitative research from the UK suggests that many people living on low incomes are unaware of how their household circumstances affect eligibility for means-tested benefits.[footnote 175] [footnote 176] [footnote 177] For instance, several of Griffiths’ research participants were surprised to find themselves better off after splitting up with a partner.[footnote 178] There is low awareness and understanding of the LTAMC rule and how it is applied; for instance, there is a widespread myth among claimants that staying over for at least three nights a week constitutes LTAMC. This suggests that the financial implications of moving in with a partner – or disclosing such a move to the authorities – may not be a central factor in decision making, even for those for whom there may be negative financial implications.

It has been stressed in the literature[footnote 179] that claimants’ decision making is not purely rational and motivated by self-interest. As one interviewee argued, individuals do not act with a strict economic rationality, motivated simply to take the course of action where they will be financially better off:

My worry is that [DWP] are focusing … [on] decision making as being a rational economic choice when it’s actually more of a moral and social choice”.

Research on couples LAT indicates that entitlement for benefits can be a motivating factor for a small proportion (around 1%) of such couples, although the evidence base is not robust enough to draw firm conclusions about this. Although there is some evidence to suggest that older couples sometimes decide to LAT to preserve pension entitlements or to avoid taking on a partner’s debt, experts commented that financial considerations, particularly relating to means-testing and benefits, were rarely mentioned by their research participants in relation to decisions about partnership and household formation. There was also some scepticism among interviewees about the idea that benefit entitlement was a key factor affecting partnership decisions and household formation:

People will not make major decisions in their lives because of a benefit. It might temporarily play some role, but they are not going to decide ‘I’m going to marry someone’ just to get a benefit or ‘I’m going to divorce someone’ just to get a benefit.

Similarly, while financial stability and independence are important factors, most people on low incomes reject the idea that decisions about partnership are influenced by benefit entitlement.[footnote 180] [footnote 181] Research suggests that many claimants do not want to be dependent on benefits. Recent research with couples claiming UC found that claimants “wanted to escape the constant scrutiny, their feeling of a lack of control, the fluctuations in income, and the time and effort involved in managing their [UC] claim”.[footnote 182] Furthermore, people on low incomes are acutely aware of the severe consequences that could befall them if they are caught committing welfare fraud. [footnote 183] [footnote 184] [footnote 185] Some interviewees talked about the challenges of conducting research in this area because stigma associated with welfare fraud may make people hesitant to discuss anything that could be considered potentially fraudulent.

In sum, the couple rate, or at least an expectation of being worse off when living with a partner, may affect decisions about partnership and household formation (although there is no evidence to link this directly to LTFE). However, financial considerations do not exist in a vacuum; they sit alongside a range of other factors in shaping decision making in this area.

Partnership decisions may be driven by concerns about financial independence and autonomy

Research highlights the high value placed on financial independence and autonomy in relationships. Couples who LAT are a diverse group, with varying circumstances, but a desire for financial independence is identified as a key factor motivating decisions to LAT. Qualitative studies highlight the importance of financial independence and autonomy to people on low incomes specifically,[footnote 186] [footnote 187] [footnote 188] [footnote 189] [footnote 190] particularly those who have experience of controlling or abusive relationships.[footnote 191] As described in Chapter 2, financial independence is particularly important for women,[footnote 192] who are more likely to be responsible for day-to-day management of household finances and who are more likely than men to have experienced financial abuse.[footnote 193]

Qualitative research shows how concerns about financial independence and autonomy can influence decisions about partnership and household formation. [footnote 194], [footnote 195] Griffiths’ research, conducted with 51 low-income mothers in the UK, found that in some cases women chose not to move in with a partner because they were concerned about the loss of financial independence associated with living as a couple, including undergoing joint assessment for benefits.[footnote 196] Conversely, not having (full) access to joint income could be a factor contributing to the decision to end a relationship.[footnote 197] For Griffiths’ research participants:

Rather than simply the absolute value of household income or the aggregate monetary value of benefits to which a household may be entitled, more influential in decisions affecting partnering dissolution was thus the extent to which the female partner had access to, and some level of control over, the family’s income and benefits.”[footnote 198]

Financial independence and autonomy are particularly important for people who have reasons to doubt the reliability of their partner, for instance if their partner is over-indebted; has a history of insecure employment; or has issues with drug, alcohol or gambling addiction.[footnote 199] [footnote 200] [footnote 201] [footnote 202] As a broad trend, people tend to partner with individuals who have a similar educational and income profile to them – a phenomenon known as ‘homogamy’.[footnote 203] This means that many benefit claimants, who tend to be on the lower end of the income distribution, may be considering moving in with a partner who does not offer strong prospects for financial stability. For Griffiths’ research participants, being assessed as a single parent offered greater financial stability than being jointly assessed with an unreliable partner:

Although lone motherhood was not without its own challenges and risks, the financial safety net provided by the welfare state was perceived by these mothers to offer a better chance of security and family stability than becoming dependent on an unreliable ‘breadwinner’ or on a new, unproven partner.”[footnote 204]

After conducting interviews with benefit claimants who have failed to disclose a partner to the authorities, Kelly observed that in several cases, this failure was because the partner was perceived to be unreliable or unpredictable.[footnote 205] People may also be reluctant to rely financially on or expose their children to a new partner whose reliability has not yet been established.[footnote 206] In instances when the new partner is not the (biological) parent, there may be concerns about whether they will expect to financially support children in the household, or whether they will do so in practice, particularly if they are paying child support to children in a another household from a previous relationship.[footnote 207] Uncertainty about relationships is a key factor affecting decisions about household formation[footnote 208] [footnote 209] [footnote 210]; when people are still testing out the stability of a relationship, joint assessment raises the stakes associated with committing to and moving in with a partner. In the words of one expert interviewed as part of this study:

There’s such a huge risk on the part of [claimants], particularly when lone parents were re-partnering with somebody who wasn’t the father of their child. To actually give up all of your financial independence and all your own benefits and expect to be supported by a new partner that you haven’t potentially lived with before is a massive ask”.

Protecting benefit income for dependent children may be a particular concern under UC since benefits are not earmarked.[footnote 211] Historically, there has been a drive to label specific benefits as targeted for children (e.g. Child Benefit,[footnote 212] Child Tax Credit[footnote 213]) and directing these benefits towards mothers, with a view to increasing the likelihood of that money being spent on children.[footnote 214] Although child benefit remains a separate benefit, Child Tax Credit has been replaced by UC, and low-income mothers may be concerned that the portion intended for children may be ‘lost’ if their partner has full or partial control over this money.

Under UC, claimants are jointly liable for benefit repayments, including those incurred by their partner under a previous claim.[footnote 215] [footnote 216] [footnote 217] In signing up for a joint claim, claimants take on any debt owed to the government by their partner. This may deter claimants from moving in with a partner or disclosing a partner to the authorities. This was not addressed directly in any of the identified sources, although one interviewee mentioned that a desire to avoid taking on a partner’s debt came up in their research as a factor motivating the decision to live separately from a partner.

Particularly when paid to only one member of the household (as is the default under UC), benefit income may not be shared equally among household members. One partner may have greater control over household resources and restrict the other partner’s access to benefit income, even in cases where UC is paid into a joint bank account.[footnote 218] [footnote 219] [footnote 220] This could lead to financial or material hardship for the other partner, even in households not officially counted as living under the poverty line.[footnote 221] Research suggests there is a gender dimension to this issue, where men are more likely to exert disproportionate control over household resources, including income from benefits.[footnote 222] [footnote 223] One source described this as “enforced financial dependency”,[footnote 224] since claimants may find themselves reliant on their partner to share benefit income equally or fairly. Qualitative research highlights how financial dependence can adversely affect relationship dynamics, for instance making the partner who contributes less financially feeling less able to speak up and assert themselves.[footnote 225] [footnote 226] [footnote 227] [footnote 228] [footnote 229] Having access to independent income may give the individual more ‘say’ in household finances.[footnote 230] In the words of one source based on interviewees with UC claimants:

Having to ask the other partner for money could change the relationship dynamic and undermine a sense of equality; it was described by some as demeaning and infantilising, though partners might not realise this”.[footnote 231]

Concerns have been raised that assessment may increase the risk of financial and other forms of domestic abuse