Use of Health and Disability Benefits

Published 15 March 2023

DWP research report no.998

A report of research carried out by National Centre for Social Research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2023.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit The National Archives or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

This document/publication is also available on GOV.UK.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-326-9

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report presents findings from a large-scale qualitative study exploring how health and disability benefits (including Personal Independence Payment, Disability Living Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance and Universal Credit) are used by recipients alongside other sources of provision and support to meet health and disability related needs.

Drawing on data from in-depth interviews with 120 participants across England, Scotland and Wales, the report provides an overview of additional needs stemming from participants’ health conditions and disabilities; how these needs are met; the role and uses of health and disability benefits in meeting needs and participants’ suggestions for improvements to support available for people with health conditions and disabilities.

Participants of this study had a broad range of health conditions and disabilities that varied in type and severity and they commonly had multiple conditions. Their financial circumstances varied widely and were affected by a range of factors, beyond simply their level of income. These factors included: the level and stability of income; debt levels; the numbers and types of health condition in the household; housing type and quality and proximity to healthcare.

Participants’ health conditions and disabilities prompted additional health-related needs across all areas of their lives including personal care, treatment and aids, support within the home, support going out and help with social participation. These additional needs often resulted in extra costs, ranging from health-specific costs such as for care, medical equipment or therapies, to increased essential day-to-day living costs such as for utilities, clothing and transport. Those with severe or multiple conditions often had more needs, or more consistent needs, than those with less severe conditions or single conditions. However, some participants, particularly those with mental health conditions, had needs such as emotional support, which were less immediately visible, despite having a significant impact on their lives.

Health and disability benefits, alongside other income streams, helped to meet almost all identified areas of additional need relating to health conditions and disabilities. However, informal support networks, health and social care services and the community and voluntary sector also played an important role in helping to meet additional needs.

Health and disability benefits were incorporated into household finances in two main ways: pooled with other income or treated distinctly. The precise use of health and disability benefits was obscured when they were pooled with other income. This approach was widespread across the sample. This meant it was not always possible to identify how health and disability benefits were used to help meet needs. When looking at household income as a whole, the most significant expenditure was on essential day-to-day living costs, including utility bills, groceries, mortgage/rent payments and car expenses.

Health and disability benefits also played a specific role in meeting additional needs through access to passported benefits, such as free prescriptions and support from local authorities with travel and parking. The Motability Scheme helped to meet participants’ travel needs through either making access to a car more affordable, providing a good quality, reliable vehicle; or enabling participants to leave the house independently. Nonetheless there were participants in the sample who were eligible but chose not to use the scheme.

The way in which benefits were used was highly influenced by the wider context of resources available to participants, including their financial circumstances, availability and awareness of free formal support and the strength of their informal support networks. These factors also influenced the degree to which additional health-related needs were met, with those with limited financial resources having to prioritise essential day-to-day living costs over other health-related needs. However, participants across the financial spectrum described a range of unmet needs in relation to social participation and mental health support.

Participants made a number of suggestions for improving support both from DWP and other agencies. Suggestions included greater awareness-raising and signposting to benefit entitlements, enhancing services provided by Jobcentre Plus (JCP) and increasing the amount of certain benefits and giving claimants more choice over when, how frequently in and in what way payments are made.

This research shows that for this group health and disability benefits are a key element of the support that is available. For those with restricted financial circumstances they offered a regular income which provided reassurance that some of their essential day-to-day living costs would be met. However, some of this group reported that they were still unable to meet essential living costs such as food and utility bills.

Health and disability benefits were also key in passporting to other essential benefits such as free prescriptions and support from local authorities, such as free travel. Among those with more financial resources their importance centred more fully on covering emotional wellbeing needs and future-proofing for younger claimants living with their parents.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Department for Work and Pensions colleagues, particularly Yvette Hartfree and Joshua Meakings who managed the project and provided valuable input and support throughout. We would also like to thank Lucy Glazebrook and Clare Morley for their input and support.

We would also like to thank Professor Roy Sainsbury of York University for providing his expertise and support throughout the project.

We are also grateful to colleagues Mehul Kotecha, Emma Forsyth, Irene Miller, Amelia Benson, Laura Izod, Hannah Biggs, Maria David, Georgia Lucey, Josh Vey and freelance consultant Andrew Thomas for supporting the project and conducting the project fieldwork.

Finally, we would like to thank all the people who gave up their time to participate in this research and share their experiences with us.

The authors

Alison Beck is a Researcher at NatCen

Thomas Barber is a Researcher at NatCen

Malen Davies is a Research Director at NatCen

Ella Guscott is a Researcher at NatCen

Dr Helen McCarthy is a Senior Researcher at NatCen

Dr Martin Mitchell is a Research Director at NatCen

Nilufer Rahim is a Research Director at NatCen

Lana Yee is a Research Assistant at NatCen

Glossary of terms

Additional health-related costs – includes additional expenses incurred because of a health condition or disability. These relate to clothing, transport, utilities, dietary requirements, medical goods/equipment, personal care, home help/ support and social participation.

Carer’s Allowance – A benefit for people who are giving regular and substantial care of at least 35 hours a week to disabled people in receipt of a qualifying extra-costs disability benefit. Carer’s Allowance is a taxable benefit.

Child Tax Credit – Paid to parents responsible for at least one dependant under the age of 16. Child Tax Credit is also available to parents responsible for dependants under the age of 20, so long as these children are in eligible education or training. It is being replaced by Universal Credit.

Council Tax Support – Each local council is responsible for operating their own Council Tax Support scheme, so the amounts of support given across the country may vary.

Disability Living Allowance (DLA) – a tax-free, non-means-tested benefit that contributes towards the extra costs of long-term ill health or a disability for disabled people under the age of 16, or who were aged 65 or over on 8 April 2013 who need help with mobility or care costs. DLA is being phased out for people who were aged 16-64 on 8 April 2013 or who reach the age of 16 and claimants are being invited to claim PIP.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) – A type of unemployment benefit offering financial support to people who are out of work due to long-term illness or disability. People claiming ESA are placed into two groups depending on the extent to which their illness or disability affects their ability to work. Its’ non-contributory element (income-related ESA) is being replaced by Universal Credit while its contributory element (contribution-based ESA) is being replaced by New Style ESA.

ESA Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG) – The ESA Work Related Activity Group is for contribution-based or income-related ESA claimants whose Work Capability Assessment outcome considers that they have limited capability for work but will be capable of work at some time in the future and who are considered capable of taking steps towards moving into work (work-related activities). People are required to have regular interviews with an adviser and undertake work-related activities. Its’ equivalent in Universal Credit and New Style ESA is known as the Work Preparation Group.

ESA Support Group – The ESA Support Group is for contribution-based or income-related ESA claimants whose Work Capability Assessment outcome considers they have limited capability for work and work-related activity. People in this group are not required to take part in work-related activities. Its’ equivalent in Universal Credit and New Style ESA is known as the No Work Related Requirements group.

Essential day-to-day living costs – these include housing, utilities, food, transport and clothing costs.

Housing Benefit – A means tested, income related benefit, paid to contribute to the rent for people of both working and pension age, in or out of work. Universal Credit is replacing Housing Benefit for most working age claimants.

Income Support – A type of benefit paid to support people on a low income who are not eligible for ESA or Jobseeker’s Allowance. It is being replaced by Universal Credit.

Jobcentre Plus Work Coach – Front-line DWP staff based in Jobcentres who support claimants into work by challenging, motivating, providing personalised advice and using knowledge of local labour markets.

Motability Scheme – A scheme open to recipients of the mobility component of DLA or PIP at the higher or enhanced rate. Eligible claimants who wish to join the scheme exchange part or all of this benefit to lease a car, accessible wheelchair car, mobility scooter or powered wheelchair.

Passported benefits – Claimants who are on out-of-work means tested benefits or tax credits are also eligible for a range of other support including free prescriptions.

Personal Independence Payment (PIP) – is a tax-free, non-means-tested benefit that contributes towards the extra costs of long-term ill health or a disability for working age people (16 to the day before State Pension age when first claiming) who need help with mobility and/or daily living costs. It replaced DLA for working age people and is available to those both in and out of work.

Scottish Independent Living Fund (ILF) – a fund to support disabled people with high support needs in Scotland.

Universal Credit (UC) – A payment to help with living costs for people on low income or out of work. UC has replaced, for most claimants, six means-tested benefits and tax credits: Child Tax Credit; Housing Benefit; Income Support; income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA); income-related Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) and Working Tax Credit.

Working Tax Credit – A national benefit paid to workers who are employed for a certain number of hours a week and have an income below a certain level. Also includes support for those who have childcare costs for children they are responsible for. It is being replaced by Universal Credit.

List of abbreviations

DLA - Disability Living Allowance

DWP - Department for Work and Pensions

ESA - Employment and Support Allowance

JCP - Jobcentre Plus

PIP - Personal Independence Payment

UC - Universal Credit

1. Introduction

This report presents findings from a large-scale qualitative study, carried out by NatCen Social Research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). This report contributes to the evidence base on the experiences of disabled claimants and how health and disability benefits are used in order to inform the design and delivery of future services.

1.1 Context and aims

In recent years the Government has committed to improving support for disabled people and building an evidence base to inform the design and delivery of future services. DWP has announced its intention to publish a Green Paper which will set out how the Government will continue to improve the system, now and in the future, to support disabled people back into work when ready and live independently.

This report has been commissioned as part of this agenda and explores how health and disability benefits, alongside other sources of provision and support, are used by claimants to meet their health and disability related needs.

The key aim of the research was to examine:

- How claimants incorporate different benefits into their household budgeting;

- How they spend these benefits and

- What drives these spending behaviours.

The health and disability benefits explored in this research include those that are intended to help with some of the extra costs of long-term ill health or disability (Personal Independence Payment (PIP) and Disability Living Allowance (DLA)) and those that are intended to help with living costs for those who are out of work (Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) and Universal Credit (UC)).[footnote 1]

1.2 Research design

The study adopted a qualitative approach, using in-depth interviews, each lasting up to 90 minutes. The majority of interviews were conducted face-to-face in participants’ homes, or a location chosen by them (a minority requested an interview over the phone). Interviews took place between August and November 2019.

A topic guide, designed in collaboration with DWP, was used to guide interview discussions (see Appendix A.3). The themes covered included:

- Participant background and contextual information;

- Overview of finances, including key forms of expenditure and debt;

- Impact of health condition or disability on day-to-day life;

- How health-related needs are met and

- Overall views on quality of life.

A purposive approach was used to design the sample of 120 achieved interviews. The interviews were clustered in eight locations in England, Scotland and Wales, encompassing rural villages, rural towns, urban towns and a major urban conurbation. The sample included individuals receiving different combinations and rates of benefits, with a variety of health conditions or disabilities. To ensure the achieved sample included participants with conditions that varied in severity, DLA/PIP rates and ESA/UC groups were used as a proxy to categorise the severity of conditions as high, medium or low. Participants were aged 18 to 64 and included an even split of men and women. While most of those in the sample were not working, a number of participants were in paid employment. A breakdown of the sample and further detail on how the severity levels were defined is given in Appendix A.1 of this report.

Accessibility was a key consideration in the design of the research. Participants had the option of taking part independently (n=77); having a ‘proxy’ interview whereby a formal appointee, relative or carer participated on their behalf (n=16); or participating in a paired interview with a relative, friend or support worker/carer present in a supportive capacity (n=27).

A Research Engagement Group convened by DWP and consisting of expert practitioners working in the field of health and disability was consulted on the research design. The study was subject to ethical review by NatCen’s in-house Research Ethics Committee.

The data was analysed using NatCen’s Framework approach which allows in-depth exploration of the data by case and by theme.[footnote 2]

1.3 Reporting conventions

The report avoids giving numerical findings, since qualitative research cannot support numerical analysis. This is because purposive sampling seeks to achieve range and diversity among sample members rather than to build a statistically representative sample and because the questioning methods used are designed to explore issues in depth within individual contexts rather than to generate data that can be analysed statistically. What qualitative research does do is to provide in-depth insight into the range of experiences, views and recommendations. Wider inference can be drawn on these bases rather than on the basis of prevalence.

Verbatim quotations and case illustrations are used to illuminate the findings. They are labelled to indicate gender, age and whether the quote is from a proxy participant. Further information is not given in order to protect the anonymity of research participants. Quotes and case illustrations are drawn from across the sample.

1.4 Overview of the report

The findings from the research are presented in the following chapters:

Chapter 1: About the participants

Chapter 2: Financial circumstances and money management

Chapter 3: Areas of additional need

Chapter 4: How additional needs are met

Chapter 5: Drivers for how health and disability benefits are used

Chapter 6: Participants’ suggestions for improvements

Chapter 7: Conclusions

2. About the participants

This chapter describes the lives of the study participants in receipt of health and disability benefits. It outlines their characteristics and their varied life circumstances to contextualise the research findings in subsequent chapters of this report.

Key findings

-

Participants in this study had a broad range of health conditions and disabilities that varied in type and severity. Having more than one health condition was widespread across the sample.

-

Participants either lived alone, with others in shared housing, in supported accommodation or with family. The first three groups relied more heavily on care and support from outside their family.

-

Levels of social interaction fell into three broad categories: no social interaction, interaction with household members and close friends only and interaction with the wider community.

-

Participants with severe mobility problems were receiving social care support. Social care support was accessed through local authority funding, the Independent Living Fund Scotland and charitably funded specialist nurses.

-

It was only possible to include eleven people in the study who were in paid work. Their jobs tended to be low-paid, low-skilled and part-time or flexible, although some participants were in full-time or skilled work. Job flexibility was key in maintaining employment. Participants not in work ranged from those not capable of work due to their health condition or disability to those capable and actively seeking work.

-

Four key factors influenced participants’ sense of wellbeing: participants’ health conditions, their financial circumstances, their levels of social interaction and their outlook on life.

2.1 Health conditions and disabilities

2.1.1 Types of health conditions and disabilities

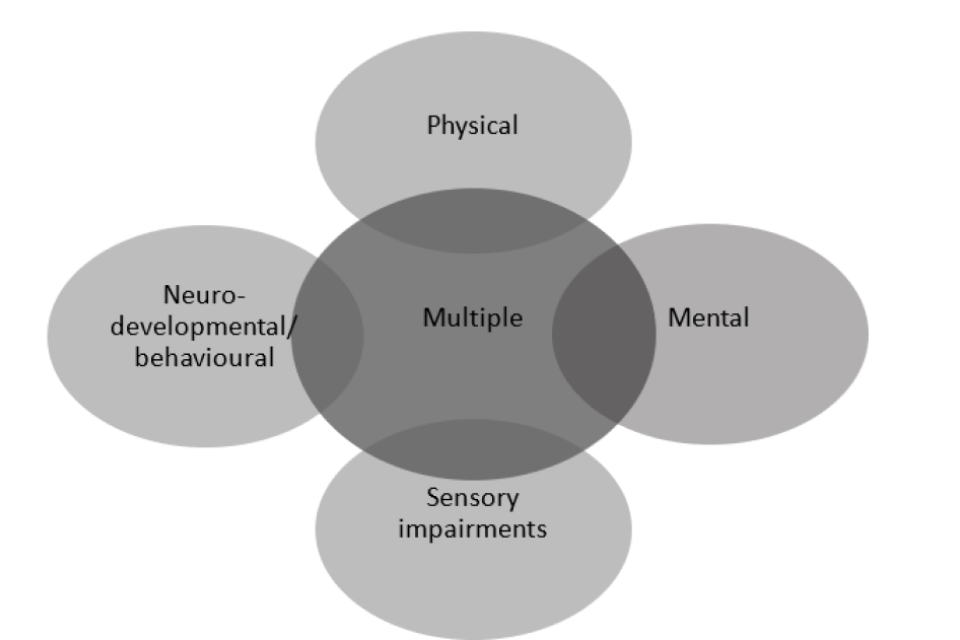

Participants described a vast range of health conditions and disabilities which can be grouped into four types of conditions illustrated in Figure 1.1

While some participants had just one health condition or disability, others had several conditions of the same type, or multiple conditions or disabilities across two or more types. Having more than one health condition and/ or disability was widespread across the sample.

Figure 1.1 Types of health conditions and disabilities

Text only version of figure 1.1:

- Physical

- Neuro-developmental/behavioural

- Mental

- Sensory impairments

- Multiple (combination of above)

The range of health conditions and disabilities included in the research by type of condition can be found in Appendix A.2.

There were four different ways that participants reported diagnosed and perceived links between their health conditions, these were:

- Conditions being or appearing unrelated;

- Conditions where one condition was a known risk factor for another;

- Conditions that were directly or indirectly causally linked or believed to be; or

- Conditions that were collectively caused by an adverse event or incident.

The daily experience of health conditions and disabilities was described as either improving, stable, fluctuating, or progressive. Improving physical and mental health was related to new or better managed treatment, or to a period of rest and recovery. Stable conditions included learning disabilities, unchanging sensory impairments and physical conditions with persistent mobility impairment and/ or constant pain. Fluctuating conditions were characterised by differing levels of pain, mobility, mental state and/or degree of sensory impairment. Progressive conditions showed worsening symptoms over time and were in some cases terminal.

2.2 Household circumstances

Participants broadly described four types of household circumstance which along with other factors, affected their level of perceived care and social support. These were:

- One-person households – claimants living by themselves;

- Claimants living in shared households – for example, as a lodger, or several people sharing the cost of a home (usually unrelated to each other);

- Claimants in supported living or residential care and

- Claimants living with other family members – including those living with partners and single parents with dependent or (adult) non-dependent children.

The first three types of households were more heavily reliant on care and support from outside their family. Participants in supported living stressed the importance of receiving regular formal care or support from an on-site carer, or someone they could call if they needed assistance. Those living with other family members emphasised the difficulties they would face in relation to their care and financial circumstances if they lived alone.

2.3 Social networks

Informal support networks, and the ability for participants to build them, was important in terms of whether their additional health and disability-related needs were met (see chapters 5 and 6 for further details). The level of social interaction, social support or social isolation that participants felt reflected the household circumstances described above, but also a range of other factors. These were:

- Whether participants enjoyed spending time by themselves or with others, including their own family;

- Proximity of their home to family and/ or friends, particularly in terms of their ability to travel easily between them;

- The accessibility of public spaces, including how accommodating they were to participants’ disabilities;

- Financial constraints on their ability to socialise where a cost or charge was involved;

- The ability and desire to involve themselves in activities or events that would enhance their social networks (e.g. volunteering, attending places of worship, going to workshops or conferences) and

- Only being able to socialise on ‘good days’ where they had a condition that fluctuated, or as their condition worsened.

These factors interacted to produce three patterns of social interaction and support networks:

No social interaction

Participants who said they had no social interaction tended to be living in one-person households. They often had no (or infrequent) visitors, but the extent to which this made them feel socially isolated varied. For some participants being alone was their preference. Others described feeling socially isolated, despite living with family members.

Interaction with household members and close friends only

Participants with severe mobility issues interacted only with people in their immediate household (e.g. immediate family or people in supported housing). These participants felt restricted because of the additional planning they had to undertake to establish the accessibility and suitability of social spaces when socialising or attending events, many of which were not found to be accommodating. Having a visual impairment could also limit socialising beyond family members. In some cases, participants were restricted to their home because they felt embarrassed about their health condition or disability, either by poor accommodation of their needs in public spaces, or negative reactions to them from other people.

Interaction within the wider community

Here, participants described higher levels of social interaction with family, friends and the wider community within and outside their immediate household. They expressed their good fortune in having the ability to engage with external networks and noted that without this, they feared boredom and anticipated feelings of social isolation.

Nonetheless, loneliness and isolation could still be experienced by participants with this pattern of social interaction if they had fluctuating conditions or when their condition worsened.

2.4 Social care

The research sought to understand where social care support was accessed and how it was used to help participants meet their health and disability related needs.

Twelve participants said that their needs were being met additionally through social care. These participants had severe mobility problems which meant they could not move around by themselves; conditions such as Alzheimer’s required participants to have 24-hour care; or learning disabilities which meant they were given access to a day care centre provided by their local authority.

Participants were not always clear or explicit about the way in which their social care was funded. Sources included local authority funding, the Independent Living Fund Scotland and specialist nurses funded charitably (e.g. Admiral Nurses who support families living with a family member with dementia). It was unclear whether other sources of care were funded as social care or as health care via the NHS. These sources included an incontinence nurse, occupational therapy and physiotherapy.

The types of social care discussed were:

- Residential care in care homes or retirement villages, sometimes with places funded by local authorities;

- One or more carers funded by local authorities coming into the participant’s home to dress, support them in going to the toilet, wash and feed them;

- Attendance at a local authority funded day care centre, regularly or occasionally, to occupy and stimulate participants and/ or provide respite for their carer;

- Receipt of funding for and installation of, adaptations to their home.

2.5 Work

As PIP is not a means-tested benefit, people are entitled to work while claiming PIP. ESA claimants can also do permitted work to help them make a gradual move into full-time work. This means people claiming ESA can work for less than 16 hours per week with earnings of up to £140 per week (April 2020), for an indefinite period, without it affecting their benefit entitlement. UC claimants in the Work Preparation and No Work Related Requirements groups can have earnings up to a work allowance threshold (which varies depending on claimants’ circumstances- the allowance is higher if they have housing costs or are in the No Work Related Requirements group) without it affecting their benefit award. Any earnings above this work allowance threshold are tapered at 63 per cent.

The research sought to include both participants who were in paid work and those who were not, to achieve a diversity of circumstances and experiences and understand how health and disability benefits were used by those in work. However, it was only possible to include eleven working participants, as very few who met the inclusion criteria for the research were in paid work. They were typically receiving PIP at the standard rate, except one who received PIP at the higher rate. One participant regularly received UC alongside PIP. Another participant only received UC occasionally, when they were between jobs.

Nature of employment

Participants in work tended to be in low-paid, low-skilled, part-time and/or flexible work, on an employed or freelance basis. Although there were examples of participants in full-time or skilled work.

Low pay was associated with low hourly wages and part-time hours. Among those on low pay were participants receiving working tax credits, housing benefit or council tax reductions to compensate for their low income.

Participants’ working patterns varied, from working one day a month on average, to 40 hours a week. On the whole participants said they preferred to work part-time because full-time work would be too tiring or painful (for those with physical health conditions) or stressful or overwhelming (for those with mental conditions). Limitations associated with health conditions were also combined with other reasons for working part-time, including:

- Believing that they would not be eligible for benefits if they worked more than 15 hours a week;

- Because they were raising a child or had other caring responsibilities; or

- Because they were also a full-time student.

Those who had flexibility at work said this was important because it enabled them to organise their work to coincide with periods of relatively good health. Some participants (who were self-employed or signed up to an agency) could choose whether to accept offers of short-term work based on their health at the time. Others worked a set number of hours every week but had flexibility about when to do those hours.

Some of those who were working had conditions that fluctuated daily. There were three reasons why participants managed to hold down a job despite this:

- They had an understanding employer;

- Their hours were flexible so could be adjusted when needed; or

- They were able to take the occasional unpaid sick day because PIP or a partner’s earnings provided a financial cushion.

Aspirations and barriers to work

Participants who were not working fell into one of three groups in relation to their circumstances and aspirations:

- Not capable of any form of work now or in the future due to the severity of their condition(s)/ disability;

- Not capable of paid work currently due to their condition(s)/ disability but could be in future if their health improved (this included participants who had volunteered as a stepping-stone to possible future work); or

- Capable of some forms of paid work now, with some actively looking for work.

Among those who felt capable of paid work, several barriers to work or to seeking work were given. These were:

- The experience or perception that employers would not employ them, or that if they did they would not be willing to make the adjustments necessary to employ them (especially in relation to fluctuating conditions);

- Lacking confidence about working and being a reliable employee; or

- Mistakenly believing that work would affect entitlement to PIP.

Nevertheless, a group of participants who were not working expressed the desire to work because they felt that work offered positive benefits such as relief from boredom, a sense of pride and contact with the outside world.

This case illustration provides an example of a participant who had to stop work because of their condition and had not found work since.

The participant suffers from uncontrolled seizures meaning she cannot be left alone. She has tried 13 different medications to control the seizures but nothing has worked; she is now awaiting brain surgery. Twenty years ago, she worked in a supervisory role in a supermarket but when her seizures worsened, she had to leave because of the risk posed by using equipment. Then she got a job working at a friend’s café, but when a new owner took over the business, they “couldn’t handle” the seizures and she was let go. After that, she started a job with night shifts, but the shift patterns made her seizures worse, so she had to leave that job. Finally, she was offered a new job in a café, but the owner decided she could not employ her because she was an insurance risk. Each time she has an interview and mentions that she has uncontrolled seizures she finds that she has been unsuccessful in her application. She is due to have surgery in the future which is hoped to stop the seizures. If this is successful she is keen to try and begin looking for work again.

Female, 30-49

2.6 Wellbeing

Where wellbeing was concerned participants ranged from being positive, neutral to more negative. Feelings of negativity were widespread across the sample and ranged from participants ‘feeling down’ to wanting an end to their life. Four main factors, often experienced in combination, affected participants’ sense of wellbeing:

-

Number and type of health conditions: those with a poor sense of wellbeing tended to have multiple health conditions, including mental health conditions for which they were not receiving treatment, or which had not stabilised. Those whose wellbeing fluctuated regularly had mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder.

-

Financial circumstances: participants who reported having positive wellbeing described themselves as financially comfortable and were often almost entirely debt-free. In contrast, persistent and significant money worries were common among those with poor wellbeing. This included people who were in debt and a group who were worried about their financial situation worsening in future.

-

Level of social interaction: participants with lower levels of social interaction tended to have a poorer sense of wellbeing, which was linked to feelings of social isolation and sometimes to depression. However, this was not always the case. Receiving good mental health treatment or support, owning a pet and having access to the Internet and digital entertainment could also help improve a sense of wellbeing where levels of interaction were lower.

-

Outlook on life: a group of participants said that although their quality of life was poor, they were grateful that things were not worse and tried to maintain a positive outlook on life. They had either come to terms with their poor health or were favourably comparing their current health to much worse health in times past. Another group, who had poorer wellbeing, described feeling powerless to improve their circumstances. They felt it was pointless to imagine a better life because their health conditions made that an impossibility.

3. Financial circumstances and money management

This chapter describes participants’ financial circumstances and the factors that affected them. It explores how claimants incorporated health and disability benefits into their household budgeting and how they managed their income in order to understand what role health and disability benefits played and the factors that drive how they are used.

Key findings

- There were a range of factors that affected participants’ overall financial circumstances including the level and stability of their income; their debt level; the numbers and types of health condition in the household; their housing type and quality and their proximity to healthcare.

- Participants with limited financial resources beyond their health and disability benefits reported that they were often unable to meet essential day to day living costs which caused difficulties with their household budgeting. Those with additional resources outside their benefits were better able to budget to meet essential and additional health related costs.

- Health and disability income was incorporated into households in two main ways: pooled with other income or treated separately. Neither way appeared to be directly linked to a more successful money management approach, although those treating their benefits distinctly did so as part of budgeting techniques.

- Health conditions affected participants’ ability to manage their money in a range of ways and in some cases meant participants were unable to manage their money themselves.

3.1 Financial circumstances

Participants’ financial circumstances varied widely and were affected by a range of factors, beyond simply the level of their income. The extent to which participants could meet essential day-to-day living costs[footnote 3] as well as their additional health-related costs[footnote 4] varied and was influenced by their financial circumstances. Participants fell on a spectrum in this regard. At one end were those with the most restricted financial resources, these participants were sometimes unable to afford essential day-to-day living costs, such as rent, heating or food and almost always unable to pay for additional health-related costs, such as additional therapies or medical goods. At the other end were participants with more financial resources who could afford all essential and additional health-related costs, such as therapies, equipment and higher additional everyday expenses. Where participants fell on this spectrum was influenced by the factors discussed below.

3.1.1 Level and stability of income

One of the key factors impacting participants’ financial circumstances was the value of their personal and wider household income streams and the extent to which they had other assets to draw upon.

Health and disability benefits

The research was designed to include participants on at least one of four main health and disability benefits: DLA or PIP; ESA or UC; or a combination of these. As was described in chapter 1, the research also included a range of different award levels, meaning that the value of health and disability benefits that participants were receiving varied considerably. In some cases, participants were not always aware of which benefits they were receiving or the rates that they were paid at.

Among participants who were in receipt of just one benefit type i.e. UC/ESA or PIP/DLA, this was largely due to being ineligible for the other type. Some participants may have been eligible for the other benefit, but were either unaware of this, or had decided against claiming because they wanted to avoid further contact with the benefit system or believed they would find work soon. In some cases, claimants said that past claims had stopped without participants knowing why.

Other income streams

In addition to health and disability benefits, some participants had a number of other income streams including: pensions (from the participant or someone else); earnings (from the participant or someone else); other benefits that the participant or another member of the household received (Income Support, Working and Child Tax Credits, Housing Benefit, Child Benefit, Carer’s Allowance) and other types of income (income protection insurance, rental income, student loans and investment income).

The level of income in households did not neatly align with differences between working and non-working households. In working households, the most significant income stream depended on the numbers of people in work and the type of work being done. Health and disability benefits were the most significant income streams where only one person was working, was on a low income and/or was working part-time. Often if family members were working part-time, this was because they had caring responsibilities for the participant, which prevented them from taking up full-time employment.

Stability of income

Stability of income was also a factor that determined financial circumstances alongside the level of income. While health and disability benefits provided a certain reliability of income, decreases in award levels following reassessments or transitions between different benefit types (e.g. from DLA to PIP) could cause participants to turn to borrowing. For in-work households, the unpredictable nature of health conditions could also lead to fluctuating income levels, as participants took unpaid leave due to ill health or family members took unpaid leave to provide care. This could also lead to households experiencing a shortfall in their finances.

3.1.2 Levels and types of debt

Debt was widespread across the sample and covered a range of types of borrowing. These included bank loans, credit cards, rent and utility arrears, doorstep lending, catalogue debts, DWP budgeting loans[footnote 5] or overpayments and borrowing from family or friends. Debt was considered unmanageable where participants listed repayments as a significant expenditure and/or where they did not have an active debt management plan in place. Unmanageable debt was found across in-work and out-of-work households and often comprised multiple forms of debt.

This case illustration provides an overview of the level and forms of debt participant experienced.

The participant lives with her two daughters aged 10 and 3. She receives PIP, alongside Income Support, Child Benefit and Child Tax Credits. She has suffered from anxiety and depression all her life, with epileptic seizures beginning nine years ago. She is £8,000 in debt and 70-80% of her income is used to pay debt. The debt was incurred through having to fix damage to her house caused by tenants when she was staying with her parents during a period of particularly poor health. What’s left of her income goes on food, bills and her children.

Female, 30-49

There were a range of reasons as to why participants had fallen into debt, some of which were linked to their health condition or disability. The most common reasons included:

- Unexpected costs (such as for funerals, new white goods);

- Special occasions with additional costs (such as Christmas or birthdays);

- Change in circumstances (for instance job loss or periods of homelessness);

- Issues with financial management (sometimes linked to health conditions) and

- Changes to benefit levels (as result of re-assessments, sanctions, or overpayments).

3.1.3 Number and type of health conditions and disabilities

Households in which more than one individual had a health condition or disability tended to have higher costs and more restricted financial resources. This included households where both partners had health conditions or where a parent and dependent had health conditions.

3.1.4 Housing tenure

Housing tenure and quality also emerged as a factor that impacted on participants’ overall financial circumstances. Participants who were owner-occupiers, particularly those who had already paid off their mortgage, tended to have greater financial resources, as did those who were living in accommodation provided by family members. Those with more restricted resources included those in private rented accommodation and those in socially rented accommodation where housing benefit did not cover their full rent. The quality of housing also impacted on utility costs, with poorly built or insulated housing leaving some participants in fuel poverty. In particular, those in rural areas often discussed the additional costs of heating oil.

3.1.5 Proximity to healthcare services

Proximity to healthcare services was another factor that impacted on participant’s overall financial circumstances. Some participants had a high number of healthcare appointments and so longer distances to doctor’s surgeries, health centres and hospitals meant participants incurred higher travel costs, particularly affecting those who lived in rural areas. This was either as a result of unreliable public transport meaning that participants had to take taxis, or long distances meaning that multiple forms of transport had to be used, with several separate fares needing to be paid each time to reach their healthcare appointments.

3.2 How health and disability benefits are incorporated into household budgets

Health and disability benefits were incorporated into household finances in two main ways: they were either pooled together with other forms of income and spent on general expenditure or treated distinctly to cover specific costs[footnote 6]. However, the different approaches were not completely distinct and did not always determine how spending was prioritised.

3.2.1 Pooling income

Pooling of income was widespread across the sample. This approach was used in both in-work and out-of-work households, across the range of health and disability benefits and award levels covered in this research and in households with varying types and numbers of income streams. Pooling occurred at the individual level (i.e. the participant pooled their health and disability benefit with their own other income streams such as earnings, pensions, or other benefits) and at the household level (i.e. income was pooled with other members’ income streams either earnings, pensions, or other benefits).

Having one ‘general pot’ was seen as the common-sense approach and so the reasons for doing so were not always fully articulated. However, specific explanations given included that additional health-related costs had to be paid for when they arose rather than when health and disability benefit payments were made and that income streams were too small to divide up.

The thing is, we have such a limited income that at the end of the day, it’s absolutely pointless putting money into little pots and saying, ‘Oh, that’s for so-and-so and that’s for something else’. (Male, 50+)

3.2.2 Treating health and disability benefits distinctly

Participants who treated their health and disability benefits distinctly also had a range of benefits and financial circumstances and included in-work and out-of-work households. However, there were three explanations for treating income from health and disability benefits distinctly:

- Firstly, health and disability and other benefits were conceptualised as serving specific purposes. For example, ESA covered household costs, PIP covered health-related expenses and child benefits and child tax credits were for children. In these instances, benefits were used to structure budgeting approaches or to reflect participants’ perceptions of the intended purpose of different benefits.

- Secondly, health and disability benefits were used for different expenses based on the timing of each payment. Here, different payment dates of health and disability benefits, or more frequent payments of the same benefit (e.g. fortnightly ESA payments) were used as a money management tool, forming the structure of participants’ budgeting processes.[footnote 7]

- Thirdly, health and disability benefits were allocated to specific needs, such as costs relating to health or wellbeing (e.g. gym classes), social activities, transport and pets, which helped with wellbeing. This approach was used in households where wider living costs, such as bills and food, were covered by a parent or partner. If financial resources in the household were limited, health and disability benefits were sometimes used to contribute to living expenses, with the remainder spent specifically on participants’ additional needs. Among this group were participants who could not manage their own finances due to their health conditions or disabilities. In these cases, family members were sometimes putting health and disability benefits aside as savings to cover future care needs.

These different approaches to treating health and disability benefits distinctly were also not always completely clear cut and in some circumstances, shortfalls in one area were simply covered by another.

3.3 Approaches to money management

The way health and disability benefits were incorporated into household budgets reflected to some extent how participants managed their money. This varied from very passive management with virtually no strategies to manage their money, to very active management with close monitoring of money and careful budgeting.

3.3.1 Passive management

Participants in this group who managed their income passively spent money when they received it. They had little idea of the state of their finances and reported very few techniques to keep track of their income and expenditure. This group included participants who had little grasp of which benefits they received or the rates of those benefits. They were either pooling their income or had health and disability benefits as their only income source.

Two main barriers to actively managing their money were reported: limited income which made them feel that budgeting was not worthwhile and health conditions that affected their ability to manage their money (see 3.3.3). People who managed their money passively were most likely to be unable to pay for additional health-related costs or sometimes essential living costs. Some participants in this group reported that they borrowed from friends and family or support services, such as foodbanks, to get by.

3.3.2 Active management

Active management ranged from those who had a general overview of their income and had some loose form of management, to participants who had detailed techniques and strategies[footnote 8] and were keeping a close eye on their money. Active management was found both among those who pooled their health and disability income with other income streams and among those who treated it distinctly. Active management did not always fully align with better financial circumstances, in some cases it was a response to having a low income.

3.3.3 The impact of health conditions on money management

Individuals with both physical and mental health conditions described how their conditions affected their ability to manage their money effectively. For instance, fatigue left participants too exhausted to budget and memory problems caused difficulties keeping track of payments. Mental health conditions meant some participants experienced a high level of anxiety in relation to their finances, while others experienced erratic and compulsive spending. Participants with sensory impairments, such a sight loss, experienced difficulties accessing information about their finances and those with neuro-developmental conditions, such as autism, found it difficult to understand the concept of budgeting as well as the costs of everyday things.

Participants responded to these constraints in different ways. For some these barriers severely limited their ability to manage their money, resulting in a completely passive approach or someone else managing their money. Others had developed a range of active techniques and strategies to try to mitigate their difficulties, for instance by noting down payments and dates.

3.3.4 Money managed by others

Finally, there were participants who did not manage their own money or only managed a portion of their own income due to their health condition or disability. Participants in this situation fell into one of three groups:

- Young claimants living with parents who were unable to manage their own money due to their health condition or disability. In these circumstances, parents managed their money and often provided some form of allowance.

- Adults, living with family, whose health condition or disability made it difficult to manage their own money and whose partner managed it for them.

- Adults who lived alone who were unable to manage their own money due to their health condition or disability, had someone external to their household managing their money as part of a paid for service.

4. Areas of additional need

This chapter identifies the additional needs that stem from participants’ health conditions and disabilities to contextualise how health and disability benefits were used.

Key findings

- Participants’ health conditions and/or disabilities gave rise to a wide range of additional needs.

- Those with severe or multiple conditions often had more needs, or more consistent needs, than those with less severe condition or a single health condition.

- There were participants with mental health conditions who had needs which were less immediately visible but had an equally significant impact on their lives to those with severe or multiple conditions.

4.1 Additional needs

The research sought to identify the ways in which participants’ health conditions and disabilities led to additional needs in different areas of their lives, to contextualise findings relating to how health and disability benefits were used, which are discussed in chapter 5.

In this chapter, the needs identified are grouped into eight broad categories described in turn below[footnote 9] . The extent and frequency with which support was needed in these areas depended on the severity of health conditions or the combined effect of multiple conditions. Specific conditions are given as examples of how additional needs arose amongst participants of this research. However, this is not to say that everyone with each named condition identified with the same needs.

4.1.1 The person

Specific dietary requirements

Physical conditions or disabilities, mental health conditions, sensory impairments and neurodevelopmental or behavioural disorders, gave rise to specific dietary needs.

There were participants who required soft, moist food or could not eat solid food, for example due to facial numbness caused by cancer. Other participants were restricted to eating very small portions or needed to follow a specific diet, such as a gluten free diet. Participants with mental health conditions such as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), anxiety and eating disorders, were sometimes compelled to eat specific types of food or to buy food only from certain shops, driven by a need to know exactly what was in their food.

Clothing and footwear

Participants were required to replace clothing more frequently due to soiling from incontinence from conditions such as Crohn’s disease, from ointments required by skin conditions such as psoriasis, or wear and tear caused by epileptic seizures. Side-effects of medication for those with mental health conditions, such as rapid weight gain, could also require additional clothing purchases. Loose clothing was needed to avoid aggravating skin conditions and to allow room for kidney dialysis equipment.

Participants with an uneven gait, arthritis in the foot and misaligned vertebrae required orthotics or specialist footwear. Others with limited mobility required Velcro shoes to minimise bending down to tie shoelaces or shoes with softer materials, to support their feet.

Care and assistance

Across the sample participants required assistance with eating, preparing food, bathing, dressing and taking medication.

In some circumstances conditions such as visual impairments, Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, memory loss and learning disabilities meant participants could not safely cook or prepare food independently. In these instances, participants required care and assistance to cook for them or used aids and adaptations to help with cooking. Help with bathing, dressing, going to the toilet and going to bed was also required by participants with a wide range of conditions, disabilities and impairments which affected mobility or cognition. This included conditions such as osteoarthritis, multiple sclerosis, learning disabilities and Clonus (muscular spasms).

Mental health conditions or learning disabilities could sometimes necessitate the need for others to monitor their medication, to avoid under or overdosing, or to provide reminders.

The frequency of these needs depended on the severity of participants’ health conditions and disabilities. Participants who required 24-hour care tended to have severe or multiple conditions, whilst daily or less frequent care needs resulted from single physical conditions, learning difficulties, less profound multiple conditions and conditions which fluctuated. There were also participants who had a range of health conditions or disabilities across a spectrum of severity levels who lived in supported housing, where they had their care needs met.

4.1.2 The home

Additional needs arising in the home included structural adaptations and help with chores such as cleaning, laundry, DIY and gardening.

Structural adaptations

Structural adaptations, such as walk-in showers, bath rails, chair lifts, hand rails and widened doorways for wheelchair access, were required by participants with a range of physical health conditions, including amputees and participants with various spinal and back conditions. Extra rooms were required by those needing a live-in carer or because some felt unable to share a room if they wanted privacy when dealing with physical conditions (e.g. use of a colostomy bag) or when managing neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g. autism) and mental health conditions (e.g. anxiety). Bigger, accessible bathrooms were required by those who used a wheelchair. Home adaptations were provided for those who needed them in supported living settings.

Help around the home

Help with household chores such as cleaning, laundry, DIY, gardening and ad hoc tasks like changing a lightbulb were required by participants across a range of physical and mental health conditions, neurodevelopmental and behavioural disorders and sensory impairments. This was due to symptoms such as fatigue, chronic pain, anxiety, lack of mobility, lack of motivation or memory loss making these tasks difficult.

My mobility is not good and I can’t bend like I normally could, […] I like getting into all the nooks and crannies and washing down my skirting boards and things. Things like that I would need to get my sister or one of my friends… to help me with that. (Female, 50+)

As with personal care and assistance, the frequency and extent of need varied and depended on the severity of participants’ health conditions and disabilities. For instance, those with physical health conditions that were chronic in nature, such as osteoporosis, required daily help. Others needed more light-touch support, for instance those with learning disabilities or epilepsy which caused memory loss.

4.1.3 Travel

Public transport

Public transport was particularly important for participants who did not have access to a car, could not drive or could not afford taxis to appointments, run errands or go grocery shopping.

Participants reliant on public transport sometimes needed support to access it. Participants with learning disabilities required chaperones to help with navigation and ensure they stayed safe. Wheelchair users in particular could only use accessible public transport. Participants with mental health conditions, such as bipolar disorder or neurological disorders such as autism or Tourette’s Syndrome required emotional support, as using public transport could be anxiety provoking.

She [participant’s daughter] always meets me at the station… Then she’ll walk me back to the station, see me get on my train, because I’m never good with travelling, especially trains […]. (Female, 30-49)

Car

Travel by car was the preferred option for participants who found it difficult to use public transport. This included participants who experienced unpredictable incontinence due to Crohn’s disease, those with conditions such as arthritis for which the bumps and jolts on busses caused too much pain and wheelchair users who could not always use accessible public transport.

In some circumstances, participants needed adaptations to their vehicle such as hoists or specialist steering equipment to be able to drive or be a passenger. This included those with back problems and wheelchair users, who had multiple conditions such as cerebral palsy and epilepsy.

The need to travel by car was greater in rural areas, where public transport was less available or reliable, or where taxis were too expensive due to long distances to the nearest amenities.

He can’t go on a bus because there aren’t any buses, there aren’t any trains, he can’t ride a bike, so he relies on his mother or his father for taking him places. (Male, 50+, proxy interview)

There were also participants with spinal problems or Multiple Sclerosis who used a mobility scooter to travel short distances.

Taxis

Travelling by taxi was an important alternative for participants who could not drive or who did not have friends or family who could offer lifts or accompany them on public transport.

The extent of taxi use varied, participants who could not use public transport, but did not have access to a car, used them regularly. This included participants with conditions or disabilities such as Crohn’s disease, a visual impairment, autism, PTSD and schizophrenia. Others used taxis for specific purposes or situations, such as when they were too exhausted to get public transport, or as a return journey from grocery shopping.

Attending healthcare appointments

Participants who had to travel regularly to hospital appointments incurred additional costs, such as increased mileage and hospital parking or increased taxi or public transport costs. Those who lived in more rural areas, who had to travel longer distances, incurred higher costs. This is discussed further in chapter 6.

4.1.4 Utilities

Specific health conditions and disabilities could lead to greater use of utilities such as power, gas and water.

Power and Water

Power and water were in regular use when participants had to wash clothing or bedding regularly because of incontinence from Crohn’s, leakage from colostomy bags or bleeding from skin conditions. Participants who spent a lot of time at home also cited higher use of electricity from having their television and lights on for long periods of time.

Heating

Participants across a range of physical and health conditions spent long periods of time at home and therefore needed the heating on more often. This included participants with epilepsy, whose seizures kept them at home and those who had anxiety and depression who found it difficult to leave the house. Participants with cancer or chronic pain, experienced mobility issues and limited energy levels which caused them to be housebound.

Others had conditions which caused them to become cold easily or meant they needed to stay warm. For example, cerebral palsy caused poor circulation, HIV and cancer caused shivers and COPD caused a poor immune system, meaning the heating needed to be on most of the time.

4.1.5 Medical goods/equipment

A wide range of medication, medical products and items, equipment and aids and therapies and treatments were being used on a regular basis.

Medication

The use of prescribed medication and treatments was widespread across the sample. The amount, type and regularity within which it was taken varied and depended on a participants’ health condition or disability. Medication was required to relieve symptoms and in some cases, it was life critical to take.

Medical products

Medical products in use included incontinence pads, skin treatments, food supplements and arm splints. Incontinence was related to several health conditions, including Crohn’s disease, learning disabilities, microcephaly and irritable bowel syndrome. Participants with cerebral palsy required arm splints that provided support for their hands. Skin treatments and shampoos were used by those with psoriasis.

Equipment and aids

The use of equipment and aids was widespread across the sample. Products included items to aid mobility, such as wheelchairs, hoists, ramps, walking sticks and standing frames. Participants who used these types of equipment had conditions such as paralysis, arthritis and myopathy (muscle disease). Amputees also had prosthetic legs. Bath boards and shower seats, perching stools in the kitchen and devices for putting on socks or doing up zips were needed for participants with conditions such as lung cancer, spinal conditions and chronic arthritis.

Larger equipment such as hospital beds and special chairs were used by participants with quadriplegia and misaligned vertebrae and safety products including community alarms were used by those with epilepsy, chronic arthritis, microcephaly and cancer.

Devices such as hearing aids and personal listeners for televisions were used by those with hearing loss and voice recognition equipment was used by participants with arthritis to avoid typing. Participants who were unable to communicate verbally due to conditions like quadriplegia used special communication equipment.

Therapeutic services

Participants with chronic pain, depression and sciatica accessed therapies such as cupping, acupuncture, hydrotherapy and oxygen therapy, to relieve pain.

Accessing talking therapies was also mentioned in relation to mental health conditions, which varied from regular use to use when symptoms flared.

Participants with a range of physical or mental health conditions reported that general exercise, including attending the gym or exercise classes, was also needed to manage physical health conditions and support wellbeing. In addition, animals, typically pet dogs, played a therapeutic role in supporting mental wellbeing.

4.1.6 Outside the home

Participants with a range of conditions and disabilities needed to be accompanied outside the home to attend medical appointments, run errands like shopping or banking and go to social activities.

Physical support

Some participants with physical health conditions and disabilities like multiple sclerosis or who had suffered a stroke, needed physical support to leave the house (e.g. help to get into their wheelchair) and to walk around.

Practical support

Participants with visual impairments and learning disabilities expressed the need for practical support when navigating public spaces, and some participants with chronic memory loss required practical help with shopping.

Well, I can’t get out anywhere on my own. I don’t know the times of the buses or anything, even if I wanted to go out. I just wait for [friend’s name] to take me shopping… (Female, 50+)

Emotional support

Participants with visual impairments or mental health conditions such as severe anxiety and schizophrenia required emotional support and often required someone to go with them when going out. These participants found tasks such as shopping highly stressful and anxiety provoking, and crowds caused panic attacks.

Participants with neurodevelopmental and neurological disorders also required help outside the home. Parents or support workers who participated as proxies for participants with learning disabilities explained that they could often lack a sense of danger or could be vulnerable to exploitation. They therefore needed to be accompanied out for safeguarding purposes.

She does get tired very quickly and she doesn’t walk very well, so that’s why we have the wheelchair. She’s got no sense of danger either so it’s also a safety capacity as well. No, she’s safer in the house walking around than she is outside. (Female, 18-29, proxy interview)

4.1.7 Money and administration

Support with money management was required by participants with both mental and physical health conditions, as described in chapter 3. Where participants were unable to physically write, had memory loss or experienced anxiety, help was also needed to complete forms. Participants who found it difficult to process new information, for example due to brain damage, required someone to make phone calls on their behalf.

4.1.8 Social participation / leisure

Having access to forms of entertainment and services at home, along with the ability to keep in touch with others or feel connected with the outside world, was valuable for those who were largely housebound.

Participants who spent most of their time at home due to their mental or physical health condition, such as depression, anxiety, epilepsy and chronic pain, relied heavily on the internet or mobile phones to keep in contact with friends and family or to lift their mood.

It lifts my mood. It’s not always me that rings them or goes to them. Quite often now they’ll ring me, … it’s just nice to have that human interaction, just to hear someone talking… (Female, 30-49)

The internet enabled participants to access games consoles, use laptops and watch the TV. DVDs, mobile phones and music were also used for these purposes. The internet was also used to buy groceries and other products for those who were unable to leave the house due to a physical or mental health condition. Others used the internet for online banking on their phone, meaning they could keep track of money going in and out of their account, or could transfer money between accounts easily.

There were also examples of participants keeping a mobile phone with them at all times in case of an emergency, such as a fall or accident.

4.1.9 Work

Flexibility and the ability to reduce working hours to part-time were the key needs identified amongst those in work. Flexibility was required to allow participants with mental health conditions, who were having ‘low’ days or experiencing adverse effects from their medication, to take sick leave.

In other circumstances where participants had physical health conditions, part of the reason they were able to maintain work was due to their ability to work part-time. Needs in the workplace included ensuring the work environment was accessible for those using wheelchairs. In circumstances where workplaces were not accessible, participants had to turn down job offers.

4.2 Additional needs in relation to severity of condition

This section presents case illustrations that demonstrate how health conditions prompted additional needs and how needs tended to vary according to a participant’s condition. Participants within the sample who had multiple or severe physical health conditions often had a wide variety of additional needs as a result, which were often significant in nature. On the whole, single or less severe health conditions gave rise to fewer additional needs. However, in some cases needs were simply different and could not be considered as greater or lesser due to condition type.

This case illustration demonstrates how multiple additional needs arise from having severe and multiple physical health conditions.

Participant has cerebral palsy, severe epilepsy, learning difficulties, and is profoundly deaf and partially sighted. He lives at home with his parents and brother, who also has complex physical health conditions and disabilities. He uses a wheelchair and requires 24-hour care. He has constant low-level seizure activity and has seizures every day. The type of epilepsy he has also causes gradual loss of abilities and mobility. In the home, he has a stairlift, wide doorways for his wheelchair, and a playroom with specialist play equipment. He needs help with all aspects of personal care, and because he has no speech, relies on others to interpret his wants and needs. His mother acts as his main carer, although NHS carers regularly take him out, and he has access to respite services and attends various clubs operated by the charity Mencap.

Male, 18-29

This case illustration demonstrates how a less severe physical health condition gives rise to fewer additional needs.

Participant lives at home with his partner and works part-time. He has a disease in his back which has worsened with age. His condition is chronic and causes him significant back pain and muscle tension, making it difficult to be mobile or work for extended periods. He uses a combination of rest, medication, muscle relaxants and laser treatment to manage the pain and muscle tightening. He has various adaptations in the home such as a double bannister and walk in shower. If he has a fall at home, he calls his brother to help him up, as his partner is not strong enough. At work his employer has agreed to give him additional breaks so that he can rest his back.

Male, 30-49

Participants with a single or multiple mental health condition sometimes had multiple needs which were less immediately visible, but which had a significant impact on participants’ lives and the lives of those around them.

This case illustration demonstrates how multiple needs, that are sometimes invisible needs, arise from a range of mental health conditions.

The participant lives with her husband and young children. She has psychosis and mania and in 2018 she experienced psychosis episode which lasted for a year. Due to her conditions she experiences heightened states of anxiety when left alone with the children, and also suffers from very heavy sleeping and sometimes cannot be woken. These factors mean she cannot be left alone with the children, and her husband decided to leave work to care full-time for the children and the participant. The participant’s husband is also her appointee, due to her high spending when experiencing mania. She is also not able to leave the house alone, due to experiencing severe paranoia and has to be accompanied by her husband or a family or friend.

Female, 30-49

5. How additional needs were met

This chapter discusses the range of ways in which the additional needs described in chapter 4 were met, including the role played by health and disability benefits. It also explores the uses and views of the Motability Scheme to help meet the costs of mobility.

Key findings

- A combination of general income (including income from health and disability benefits); informal support networks; health services; social services and community and voluntary sector organisations were used to help meet participants’ health-related needs.

- The most significant expenditure of health and disability benefits, alongside other income, was for essential day-to-day living costs, including utility bills, groceries, mortgage/rent payments and car expenses.

- Health and disability benefits played a unique role in helping to meet additional needs through access to passported benefits such as free prescriptions and support with travel and parking provided by the local authority.

- The Motability Scheme helped to meet participants’ travel needs through making access to a car more affordable, providing a good quality, reliable vehicle; or giving participants independence to leave the house. There were also eligible participants who did not use the scheme either because they were unable to drive, felt there was stigma attached to driving a mobility scooter, preferred to keep their PIP payment, anticipated incorrectly that another assessment might take place, or were unaware of the scheme.

5.1 How health and disability benefits are used to help meet needs

5.1.1 Main sources of support

Participants’ additional needs were usually met through a combination of the following sources of support:

- General personal/ household income, including health and disability benefits, earnings, pensions, savings, other benefits and forms of income (e.g. investment income)

- Informal support networks, primarily relatives, also friends, neighbours and faith groups

- Healthcare services, mainly the NHS (including occupational therapy), as well as private providers

- Social care services provided through the Local Authority (LA)

- The community and voluntary sector (CVS) including charities and community interest companies.

The sources of support participants drew on and the extent of their use varied widely across the sample. This mainly depended on a participant’s level of need, wider household and financial circumstances and access to and use of informal support networks. Table 5.1 summarises the sources of support used to meet each health-related need identified.

Table 5.1 How each of area of additional need was met

| Area of need | Income (inc. H&D) | Healthcare services (i.e. NHS) | LA social care services | Informal support networks | CVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person (Specific dietary requirements) | Paid | ||||

| Person (Clothing & footwear) | Paid | Free | |||

| Person (Care & assistance) | Paid, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | |

| Home (Structural adaptations) | Paid, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free | |

| Home (Larger home) | Paid | Free | |||

| Home (Help around home) | Paid | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | |||

| Travel (Car) | Paid | Free | |||

| Travel (Public transport) | Paid | Free | |||

| Travel (Taxis) | Paid | Paid for through funds from multiple sources | |||

| Utilities (Water) | Paid | ||||

| Utilities (Heating) | Paid, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Paid for through funds from multiple sources | |||

| Utilities (Power) | Paid | ||||

| Medical goods (Medication) | Paid | Free | |||

| Medical goods (Products/items) | Paid | Free | |||

| Medical goods (Equipment & aids) | Paid, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | Free, Paid for through funds from multiple sources | ||