How DWP involves disabled people when developing or evaluating programmes that affect them: occasional paper 25

Updated 1 March 2021

Chair’s foreword

In March 2019, the Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions at the time, signalled that a new approach was needed in the way her Department engaged with disabled people. She acknowledged then that there was a lack of trust, and that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) needed to find a way to re-engage with disabled people.

Amber Rudd’s successor, current Secretary of State The Rt. Hon Thérèse Coffey MP, and her Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work (Justin Tomlinson MP) have demonstrated their clear support for the ambition she set out.

In particular, Justin Tomlinson engages regularly with disabled people’s organisations, and is also taking steps to ensure that preparation for the Disability and Health Green Paper involves direct engagement of disabled people, organisations who work with disabled people and organisations led by disabled people in a series of ‘listening’ events around the UK. But we need to be realistic.

The scale of the challenge facing DWP – particularly given the size of the organisation – is considerable. The cultural change that the then Secretary of State was keen to deliver was never going to happen overnight and – like turning around a super-tanker – a degree of patience is required before the desired destination can be reached. This report examines how far DWP has come in that journey, and explores what more can be done to further strengthen their approach.

The report represents a new departure for this committee. Most of our independent advice to Ministers focuses on the actual or potential impacts of policies that have been implemented. But, through our scrutiny of draft regulations, we also have a long-standing interest in the quality of the policy-development process and plans for operational delivery.

During our scrutiny of regulations, we often ask questions about the evidence base, the risks, how the proposals will be communicated and the impacts on different groups of people.

I am therefore pleased that we have been able to use that experience to provide advice on how government approaches social security policy development. With a Disability and Health Green Paper on the horizon, it is particularly timely to share our assessment of the degree to which DWP builds a good understanding of the experiences of disabled people who use the benefit system, and how far it involves them in evaluating and designing its services for disabled people.

This report provides evidence of some good examples of where DWP has engaged disabled people in the past – more so than many might have thought. But it is clear that the level of trust had deteriorated over a period of successive administrations, during which a number of significant benefit changes have been introduced. We are pleased that DWP recognises this, and that it is – through work personally led by the Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work – aiming to rectify that.

Our report makes a number of recommendations setting out where we consider the Department can go further and embed best practice across its organisation. But in doing so, my SSAC colleagues and I have come to the realisation that there are lessons from this exercise that we could – and should – take on board ourselves.

Whether that be making our consultation exercises and workshops are more accessible, or ensuring that more of our communications are available in Easy Read. We are committed to doing better and look forward to working alongside DWP to deliver some positive change.

Dr Stephen Brien

SSAC chair

Executive summary

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is in the middle of a programme intended to transform the delivery of social security to disabled people, and has plans to consult widely early next year on policy changes that will be outlined in a health and disability Green Paper.

It has also made a strong commitment to deliver policies and strategies that are co-produced with disabled people, and intends to explore how the welfare system can better meet the needs of claimants with disabilities and, or health conditions[footnote 1].

The Social Security Advisory Committee (SSAC) regularly examines how the social security system is working, its rules of entitlement and how they are delivered as part of its statutory scrutiny of secondary legislation and our other advisory work. In doing so we see an end product that has been shaped by varying levels of DWP’s consultation of, and engagement with, relevant stakeholders.

We wanted to build on our experience of the end of the design process by looking back at earlier stages of the journey and offering constructive advice on how it might be further strengthened. In particular, by examining how DWP designs and implements aspects of the social security system and how it determines whether or not it is working.

We have focused on how DWP involves disabled people when developing, delivering and evaluating programmes that affect them[footnote 2]. We believe that this focus is particularly relevant and timely as DWP takes forward its programme to transform the delivery of social security to this group.

Co-production with disabled people has long been accepted as best practice in other areas of social policy, particularly health and social care. DWP has commendably set the bar high, by framing its ambition in terms of co-production. But involvement can mean many things. It includes:

- seeking to understand the experiences of disabled people

- asking for views from disabled people

- working with disabled people to develop new policies or operational changes. At its most reciprocal this is co-production.

We have looked at how DWP involves disabled people across this broad spectrum of involvement.

In many of our meetings with DWP officials, we were told it was vital for the Department to work with and learn from disabled people if it was going to achieve its strategic business objectives. They told us that lack of trust was a major issue; and a barrier not only to joint working but to the effective delivery of their services. They said they wanted our study to give them feedback on how far they had come, and to provide advice on how to improve further. This report is written in that spirit.

How we approached this

This is a very broad subject so, to ensure that the scope of our work was both realistic and deliverable, we concentrated on how DWP has been involving disabled people in relation to working age benefits (rather than focussing on disabled children or disabled people of pensionable age).

We chose benefits for working age people because these have raised some of the most contentious issues. Our project coincided with DWP’s preparation for its Green Paper – a process in which the Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work[footnote 3] and DWP officials have sought to engage directly with disabled people, organisations who work with disabled people and organisations led by disabled people.

However, our report is not a review of the Green Paper process. It looks at how DWP has been involving disabled people more generally.

In establishing how DWP is viewed by others, we spoke to officials from different parts of the Department to better understand DWP’s own perspective, and also held focus groups and meetings with disabled people, their organisations and wider stakeholders to develop an understanding of their views and experiences. Inevitably the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted our project, in particular by limiting our fieldwork, so our findings are tentative in some areas.

We also looked at examples of how other organisations approach the same issues.

There are many pockets of excellence across central and local government in involving disabled people and citizens generally, as well as a huge depth of experience in many health and social care organisations[footnote 4]. While there is a lot of difference, there are also many commonalities – for example, the need to sustain long term engagement, structure, diversity, connecting with disabled people’s own organisations, and the importance of cultural factors – leadership, openness, mutual respect, and courage.

We cannot substitute for expertise of other organisations, so our advice highlights areas of potential further improvement, drawing on themes from that practice, rather than offering detailed guidance on how to achieve that. We encourage the Department to consult and learn from that existing knowledge and experience as it develops its practice further.

Our findings – including recent improvements

Our key findings are set out below.

The Department has a lot more mechanisms for understanding how disabled people experience social security and what they think about changes to it than is often assumed.

DWP involves disabled people in a variety of ways. Some of its methods are longstanding, for example the use of user-centred design in operational processes, or gathering views through large scale regional listening events. Others are relatively new for the Department, like adopting user-centred design techniques in policy development. Some were more common in the past than now, for example, regular meetings with disabled people’s organisations.

In terms of the ‘ladder of participation’ (a way of thinking about the depth of an organisation’s involvement which we explain more fully later in the report) there is evidence that DWP has operated at all its rungs – from ‘informing’ to ‘full engagement’.

DWP’s intention to engage is genuine. There is clear evidence that DWP is not just “talking the talk”, but is beginning to “walk the walk” in terms of engaging disabled people around the UK, as well as how they talk to larger organisations.

There is also evidence that the Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work is taking action that is designed to rebuild bridges and lines of communication with some disabled people which had fallen into disuse. Civil servants working on the Green Paper have arranged a series of listening events with disabled people throughout the country, as well as a programme of discussions with national organisations. We are pleased that DWP recognises the issue of trust and is committed to tackle it.

DWP’s intention to engage applies not just in relation to the forthcoming Green Paper, and its work to reshape the delivery of some of its benefits. In very different parts of the Department we spoke to officials who could describe confidently why working with disabled people was important and could provide very clear examples of what they were doing – for example, in thinking through how their own jobcentre could become more accessible to people with autism.

In our discussions with external organisations that have longstanding relationships with DWP it was clear that some had experienced a definite improvement. One said:

‘The door is now open. DWP used to have a fortress mentality and didn’t feel able to engage. But the Department is now more transparent and, in some parts, reaches out at an earlier stage. So we are asked to help develop options. Not comment on pre-set solutions’.

However, this change in the Department’s approach is relatively recent and exploratory, particularly in policy development. It is too early to say how far the DWP is acting act on what it hears, or whether it will lead to demonstrable improvements. The Green Paper and any accompanying operational changes will be the litmus test of this.

It will also take time for this approach to fully bed down throughout the organisation. It also takes time for trust and confidence to build up amongst disabled people. The stakeholders we spoke to saw room for improvement.

We also saw, at first hand, ways in which DWP could listen more effectively. We therefore conclude that there is scope for the Department to strengthen its approach further in a number of areas. These include:

Clarity of ground rules

Some of the other organisations we looked at had clear and explicit disciplines for how and when they involved citizens and stakeholders. DWP, which is evolving its approach, could benefit from this. For example:

- As DWP introduces new methods of engagement, it will be important that it provides clarity around its ambition. The Department’s Single Departmental Plan set out a commitment to: ‘Deliver policies, strategies and structures that are co-produced with disabled people.’.

But it is not clear that co-production is what the Department actually means, and it was not what we saw happening, in the sense of an equal relationship between the DWP and other players. One senior official described what he was engaged in as ‘participative design’ and observed that the organisations he was working with did not want the process to be described as co-production.

Moreover, it is debatable how far co-production is achievable at all in social security benefits policy, as compared with social security delivery or other aspects of DWP’s work like its health and work programme.

-

This ambiguity was reflected in uncertainty expressed by some officials about how open they could be about ideas the Department was considering. Some of the officials we spoke to were not confident they could discuss policy options. So, diagnosing and exploring problems were clearly on the table, but not necessarily potential or emerging solutions.

-

There was scope for DWP to do more to ensure it was hearing from a sufficiently wide range of voices, particularly BAME representation, or from people whose voices are often not heard. Public Health England’s stakeholder engagement exercise in May 2020 is an example of involvement of such involvement at scale. Set up to explore the effects of COVID-19 on BAME communities, it involved over 4,000 people with a broad range of interests in BAME issues in 17 stakeholder sessions[footnote 5].

-

The Department has tended to rely, both centrally and locally, on relationships with organisations that provide services to disabled people. At national level this reliance was on large, national charities. This meant it was on the whole missing user-led organisations, and missing local organisations that had particular perspectives, expertise or constituencies from which DWP could learn, and which would help it hear a wider range of voices. Where engagement with these types of groups was occurring, evidence provided to us suggested that it was more ad hoc and fragile.

-

The practice of giving feedback to disabled people and organisations which DWP had consulted often came across as an afterthought, even in otherwise well-planned events.

-

Some of the officials we talked to about the value of involvement tended to emphasise the benefits of DWP getting information out to disabled people. They sometimes did not mention the benefits of learning from disabled people.

These presenting problems appear to be symptoms of an underlying issue – a need for greater consistency and ground rules. Despite the clear lead by Ministers and senior officials, it inevitably takes time for a new openness to be fully embedded in an organisation as large as DWP. Involving disabled people has yet to become part of the standard way of doing business in DWP, with a clear discipline.

We conclude that DWP should establish a methodology that enables a consistent, understanding throughout the Department of the purpose of engagement and the methods to deploy in different circumstances. Done well, this should lead to:

- consistent implementation

- greater confidence by officials, improved mutual understanding between DWP and diverse disabled people, and their organisations, on the approach to engagement, with potential gains in both culture and trust

NHS England’s Patient and Public Participation Policy[footnote 6], and its suite of accompanying material, is an example of a similar methodology, though obviously designed for a very different business context.

Recommendation 1

Our primary recommendation is therefore that DWP should develop a clear protocol for engagement. This protocol should be co-produced. It should be applied consistently and comprehensively. It should cover both national and local engagement, and policy design and operational development and evaluation. It should be evaluated and improved over time. It should set out clearly:

- the principle that DWP will engage to the greatest extent possible in the prevailing context; setting out what models of engagement should be adopted in which broad circumstances

- principles about feedback and openness, so that disabled people know what they can reasonably expect when they are engaged by DWP

- principles for accessibility, so that disabled people with different impairments can have an equal voice

- what DWP means by co-production and co-design, incorporating steering arrangements that give disabled people an influential say

- how DWP will engage with different sorts of organisations, ensuring that user-led organisations, including small and local user-led organisations are actively and systematically engaged

- a discipline for assessing whether DWP is hearing from a sufficiently wide variety of voices across the range of protected characteristics, and how it will proactively seek out people with particular experiences to remedy any gaps, for example people with experiences across the spectrum of different impairments, BAME disabled people with different heritages, homeless disabled people, disabled survivors of domestic violence – learning ways of doing it from best practice in government and in national health and social care organisations

- a commitment that DWP will routinely provide feedback on the outcomes of engagement in terms of action taken, and engage disabled people in assessing whether changes have worked

There are a number of other areas where we are making more specific recommendations as described below. And some of these would also lend themselves to being included in such a protocol.

Transparency

DWP officials themselves acknowledge that the Department is not trusted by many disabled people and by some of the organisations who are led by, or work with, disabled people. Our own research confirmed this. Some of the individuals we spoke to did not believe that the Department engaged with disabled people’s organisations or sought views from individual disabled people.

There was also a widespread belief that DWP would not represent accurately disabled people’s views when they did seek them. When we looked at other organisations which have made participation with citizens a central part of their practice, we were struck by the importance they attached to openness. They continually demonstrate that they are engaging with citizens, how they are engaging, what they hearing, and what happens as a result.

By contrast, in a highly contested political environment, DWP sometimes prefers to discuss potential changes in confidence with stakeholders they trust. But this tends to perpetuate DWP’s reliance on the organisations it already has a history of working with, which limits the views it hears. And it often rules out the opportunity for participants to prepare or research, which limits the depth of what it hears.

To demonstrate that its commitment to engage is real, DWP should show how they are involving disabled people, and organisations of and for disabled people. To ensure DWP can fully embrace involvement as part of its standard way of doing business it also needs a culture in which there is a presumption of openness. We recognise that there will be times when Ministers and officials need to have confidential discussions; and there may also be times when organisations want their discussions to be kept confidential however these occasions should be a conscious choice; not a default position.

Recommendation 2

We recommend that DWP routinely publishes information about its engagement. This should include not only terms of reference, membership and minutes of advisory groups, but also how citizens are involved in processes like user-centred design, the lessons that are learnt in that process and what happens as a result. Where it is necessary that the content of discussions remain confidential DWP could, in line with the approach already taken by Ministers[footnote 7], quarterly publish a list of meetings and subjects discussed.

Direct engagement

As described above, DWP’s Departmental Plan commits the Department to co-production with disabled people (our italics). We have seen that in social security operations DWP has adopted user-centred design as a standard methodology. We have also been told about model offices which learn from disabled people locally about how to make services more accessible. In developing social security policy DWP has been running local listening events involving disabled people directly.

However, much of DWP’s engagement remains with large national charities which are nearly all service providing organisations run for disabled people, rather than by them. This offers officials certain advantages. It means that they can deal with full-time policy professionals who understand how government operates, can respond relatively quickly to DWP’s questions, can often draw on large databases of individual experiences, and can put DWP in touch with disabled claimants directly. However, it is not the same thing as involving disabled people, or co-production with disabled people.

However professional or well informed an organisation might be, it cannot be treated as speaking for disabled people unless it is set up to do so. There are also clear risks that disabled people’s voices will be filtered through the policies of the organisations. An over-reliance on the big national organisations goes hand in hand with DWP’s lack of engagement with BAME and other less heard groups.

For these reasons there is no substitute for engaging with disabled people directly. The Cabinet Office is establishing Regional Networks of disabled people and disabled people’s organisations for government to consult. Some of the Regional Chairs have helped DWP set up local listening events ahead of the Disability and Health Green Paper.

We have looked at whether the Network will address DWP’s need for regular and sometimes intensive involvement of disabled people. However, while the Network will provide an important avenue for DWP engagement with disabled people, the volume of DWP’s business is likely to overwhelm it as currently constituted.

An alternative could be frequent large-scale surveys and ad-hoc exercises in which disabled people are engaged in more long term, intensive pieces of work. However, we have been advised by several of our participants that it can take some time for individual people to develop the confidence and skills that enable them to contribute fully to complex policy discussions.

Recommendation 3

We recommend that DWP recruit a large-scale panel of disabled people with experience of social security that it can consult regularly, and draw from, to work on detailed projects. The panel should be sufficiently large that surveys of its members produce valid results, but it should be weighted to include people with different life experiences who can often be overlooked. In Scotland the equivalent panel has over 2,000 members. When asking panel members to joined sustained pieces of work, DWP should support them with facilitators and capacity building as necessary. DWP should also consider recruiting similar panels at local level to support jobcentres.

Learning from the pandemic

DWP has traditionally relied on face to face meetings for its engagement. This can not only reduce the amount of time available for meetings, but it can narrow the range of people who can easily attend. At national level this tends to mean people who can get to meetings in London, and to a lesser extent other big city centres. One of the beneficial effects of the current pandemic is that it has shown that other ways of engaging with people are effective and are sometimes – for many – more accessible. We welcome the fact that DWP is now actively using these.

Recommendation 4

We recommend that DWP should make increasing use of publicly available, accessible, networking tools, including video-conferencing, to make meetings and other forms of contact more accessible to disabled people. Officials who use such tools should be familiar with their accessibility features. However, DWP should supplement these methods with other ways of reaching people who may not be able to use such technology, for example because the software does not work for them, or because of lack of skills, or good access to IT.

Third Party Providers

The services that DWP provides for disabled people are often delivered through third parties – e.g. for carrying out Personal Independence Payment (PIP) assessments and Work Capacity Assessments (WCA). We have been told by some of the participants in our research that DWP officials’ responses tend to be more formulaic when the questions are about the organisations that work for it.

As a matter of principle, it would not be right if involvement with disabled people stopped at the doors of third parties. These third parties are a crucial part of the interaction that disabled people have with the social security system. The discontent that people express about PIP and about Universal Credit (UC) is not just about the rules of PIP and, UC but about the ways in which assessors work[footnote 8].

Recommendation 5

We therefore recommend that DWP routinely build its principles of engagement into its contracting processes. For example, by involving disabled people in co-designing contracts, the methods by which it evaluates bids, and potentially directly assisting it to evaluate bids. DWP might also build evidence of co-design into the way bids are assessed; and require user-experience metrics.

Accessibility

In taking steps to build trust with disabled people. DWP should take care to minimise barriers that could create challenges in their day to day dealings with the Department. Though we did not ask specific questions about accessibility, we received several evidence-based representations about shortfalls in accessibility. Some of these were difficulties that some people face accessing generic services like Universal Credit. Some were access challenges to long-established disability specific services, like Access to Work.

We are therefore pleased that DWP is setting up a Reasonable Adjustment Forum on Accessible Communications to identify, test and recommend improvements to the services provided for those with accessible communication needs.

Recommendation 6

We recommend that DWP rapidly assesses areas in which it needs to improve the accessibility of their services and make it a priority to implement solutions.

Culture

Ultimately, many of these recommendations are about culture. The people we spoke to who had experience of working not only with DWP but with other large public sector organisations sometimes also spoke as if a different cultural mind-set was involved in organisations which routinely engaged with others. They used words like ‘flexible’, and ‘not defensive’ to describe them.

DWP’s level of openness has varied over time. Currently, it is making a major positive effort to be more inclusive in its approach. To maximise the success of this approach, and to sustain it over time DWP should:

a. Convince organisations and citizens the change is real. b. Effect behavioural change among its own staff, ensuring that they understand what is expected of them and that they are able to confidently deliver that expectation.

This would be hard to do without cultural change. The civil service generally, and DWP in particular, has improved its hard evidence base, and the professionalism of its analysis. It has achieved this through well-established rules about the standards for statistics, how social research is commissioned and published, and how economic analysis is conducted.

This is comparable. There is a strong case that involving the people who are most affected will improve the quality of policy making and operational design processes, and may improve their experience of the outcome.

Cultural change in any organisation needs to be developed and owned throughout the organisation and led from the top. It would not be enough for DWP to have the right apparent policies if in practice they were not valued by the organisation or implemented consistently.

Recommendation 7

We recommend that DWP shows through its leadership actions and – messages – from all leaders across the organisation that actively involving people claiming social security, including disabled people, is central to the Department’s values and way of working. The Department should build its expectations about involving disabled people into its corporate governance arrangements.

The Executive Team should receive regular reports on progress. In addition, a non-executive member of the Departmental Board should be given responsibility to champion disability engagement and to have oversight of the progress being made, reporting back to the Board on the Department’s performance at regular intervals.

Conclusion

We believe that these recommendations can go a long way to reinforcing the changes that the department has started to make to involve disabled people more effectively in its work.

They will help it build the trust it needs to make a success of its policy objectives, and make it more likely that future changes work with the grain of disabled peoples’ lives.

Introduction

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP’s) single departmental plan sets out its intention to:

“Deliver policies, strategies and structures that are co-produced with disabled people. We will continue to facilitate a public conversation on the health and disability agenda. Including exploring how the welfare system can better meet the needs of claimants with disabilities and health conditions. It’s our ambition to go further: to listen harder and reform effectively[footnote 9].”

Disabled people are a major focus for DWP, which hosts the Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work who has cross-government responsibility for disabled people. The second objective in its departmental plan is to:

“Improve outcomes and ensure financial security for disabled people and people with health conditions, so they view the benefits system and the department as an ally[footnote 10]”

The Department leads on the government’s commitment to increase the number of disabled people in paid employment by 1 million between 2017 and 2027. The total social security spending on disability benefits amounted to £56 billion in 2019 to 2020[footnote 11].

Data shows that as at February 2020:

- 3.9 million people were in receipt of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) or Disability Living Allowance (DLA)

-

1.9 million people were in receipt of an incapacity benefit such as Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)[footnote 12]

-

almost 42 thousand people were in still in receipt of Incapacity Benefit and Severe Disablement Allowance over a decade after ESA was launched[footnote 13]

- the number of UC households in receipt of Limited Capability for Work Entitlement was 430,412 (May 2020)

Towards the end of 2019, this committee started to examine how the Department for Work and Pensions involved disabled people when it was developing, implementing and evaluating policies and practices which affect them.

There were several reasons why we chose this topic.

In other areas of social policy – particularly social care, health and housing – co-production has become accepted as best practice and is written into statutory guidance issued by the Department of Health and Social Care under the Care Act 2014[footnote 14].

In part this has been a response to a longstanding campaign by many disabled people for support that gives them control of their own lives, and to be heard directly rather than be spoken for – encapsulated in the slogan, ‘Nothing about us without us’. But it also reflects an increasing trend in social policy for governments to involve citizens actively. We wanted to see what point DWP had reached in this trajectory, and the scope for its use in social security.

The qualifying criteria and assessment processes for disability-related benefits have also long been problematic. In April to June 2019, the overturn rate for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) and Personal Independence Payment (PIP) appeals was 75 per cent, and 67 per cent for Disability Living Allowance (DLA) appeals.

The ESA and PIP overturn rates had increased by 4 percentage points compared to April to June 2018[footnote 15]. A number of changes were made to these benefits after several independent reviews[footnote 16] but a speech to Scope in March 2019 by former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Amber Rudd, signalled that the government had accepted that improvements were needed[footnote 17].

“Some disabled people have said to me that they feel as though they are put on trial for seeking the state’s support”

Amber Rudd

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

March 2019

We wanted to explore whether these problems stemmed in part from DWP not engaging with disabled people effectively.

It was also apparent that many disabled people, and many disabled people’s organisations assumed that the Department did not talk to, let alone listen to, disabled people. We wanted to find out whether, or how far, this was true.

This was a challenging project to undertake. First, the potential scope was very wide. We decided to focus on the Department’s policies relating to adults of working age, rather than for children or those who had reached state pension age.

We chose this group because some of the most contentious issues concern working age people. We also decided not to look at issues of accessibility as there are many organisations much better qualified than this committee to offer advice on this issue[footnote 18].

Nor have we been able to look in depth at the Department’s quantitative systems.

Secondly, the initial COVID-19 national lockdown was introduced shortly after we began our fieldwork. We had planned to spend time observing some of DWP’s own listening events and finding out how DWP connected with disabled people in Scotland and Wales and locally.

This aspect of our review was substantially curtailed when the Department understandably closed its offices to all but essential visitors and redeployed all available staff into handling the upsurge in Universal Credit claims.

Indeed, we also redirected our resources to examine the many changes to the social security system that government made in response to the pandemic. Similar challenges in Northern Ireland meant that our ambition to consider the Department for Communities’ approach to engaging disabled people was not practical at this time. Likewise, many of the regional stakeholders that we wanted to talk to had similar restrictions on their availability.

Our findings are therefore more tentative in some areas than we had originally intended.

This review has also made the committee reflect on its own practice. Some of the criticisms that disabled people’s organisations level at DWP can also be levelled at us. Do we communicate in accessible ways? Do we allow enough time for people to respond to our consultations? When people who have invested time, thought and energy in contributing to our work, do we give sufficient feedback on how we will use their input, and what happens to it? So, in addition to sharing our learning with the Department, the committee plans to go further by making a commitment to do better itself.

We will also need to develop the sort of protocol we are recommending to DWP and establish a set of principles. In particular, we need to ensure we are inclusive in the way that we engage with our stakeholders, for example by allowing more time for people to respond to our consultations wherever that is possible (and explaining ourselves if it is not), making available Easy Read versions of our documents where appropriate, and through making use of technology to enable greater engagement of individuals and organisations throughout the UK, alongside face to face and written communications.

Finally, disabled people often observe that a world which is more accessible for disabled people is more accessible for people generally. Buildings which are easy to navigate for wheelchair users, are also easier for people with children in pushchairs, or carrying luggage. Information that is easy for people with learning disabilities to understand can aid comprehension for everyone.

The same applies to many of the lessons in this report. The practices and disciplines of involving disabled people effectively, apply to citizens generally.

To inform this project, SSAC undertook a public consultation through a call for evidence, to which we received responses from 64 organisations and 57 individuals[footnote 19].

We also spoke to policy experts and organisations led by and, or working directly with disabled people, jobcentre staff, and support workers across the UK.

We are grateful to everyone who participated and provided valuable insight which helped inform this report.

Our approach to this work

Our aim has been to find out how the Department involves disabled people, and organisations who work with disabled people, throughout the policy lifecycle and to consider whether improvements were needed.

For the purposes of this report, the policy lifecycle is:

- developing policy and strategy

- turning policy into practice and delivering services

- finding out what works and what does not

The Department is a huge and complex organisation and we wanted to establish how it involves disabled people at different levels, from its corporate hubs in London and Leeds through to its local jobcentres.

Our definition of the following words and phrases used in this report:

Disabled people – people with impairments or long-term health conditions which affect their day to day lives.

Disabled people’s organisations – organisations led run by disabled people

Organisations for disabled people – organisations which advocate with or for disabled people or provide services for them, but which are not led by them.

Disability organisations – we use this term when we are talking about both categories of the above organisations.

Service providing organisations – organisations which provide services to disabled people. They may include both organisations led by disabled people and organisations for disabled people.

Co-production – there are many definitions. We’re using a strong definition which emphasises equality and power sharing. The New Economics Foundation says that co-production is:

‘The relationship where professionals and citizens share power to design, plan, assess and deliver support together. It recognises that everyone has a vital contribution to make in order to improve quality of life for people and communities[footnote 20]’.

Co-production also rests on values. The Social Care Institute for Excellence notes that the values of equality, diversity, accessibility and reciprocity are needed for co-production to work.

Co-design – A closely related concept, which also has many definitions. We’re again using it in a strong sense. A process of working with disabled people in an equal and reciprocal relationship but where ultimate decision-making authority remains with DWP.

Within these overall aims, we asked the following questions:

-

What are DWP’s policies or practices on involving disabled people? Are they consistent, and have they led to identified improvements?

-

Does DWP reflect on its experience of involving disabled people? Does it share lessons across the organisation?

-

Does it include people from all impairment groups – people with cognitive, sensory, and mental impairments as well as physical impairments? Does it consider gender, race, sexual orientation and other protected characteristics? How does it include disabled people who are often overlooked in disability-related discussions, such as homeless disabled people?

-

What is DWP’s practice in learning from feedback?

-

Do the Department’s quantitative systems, IT systems and surveys, enable it to learn about disabled people’s experience of social security?

-

What are the relevant lessons from other large organisations which involve disabled people and/or service users?

-

How should DWP handle mismatches of expectations – for example, when there is likely to be a gap between what disabled people want and what DWP is able to agree? How can mutual trust be built and maintained in these circumstances?

-

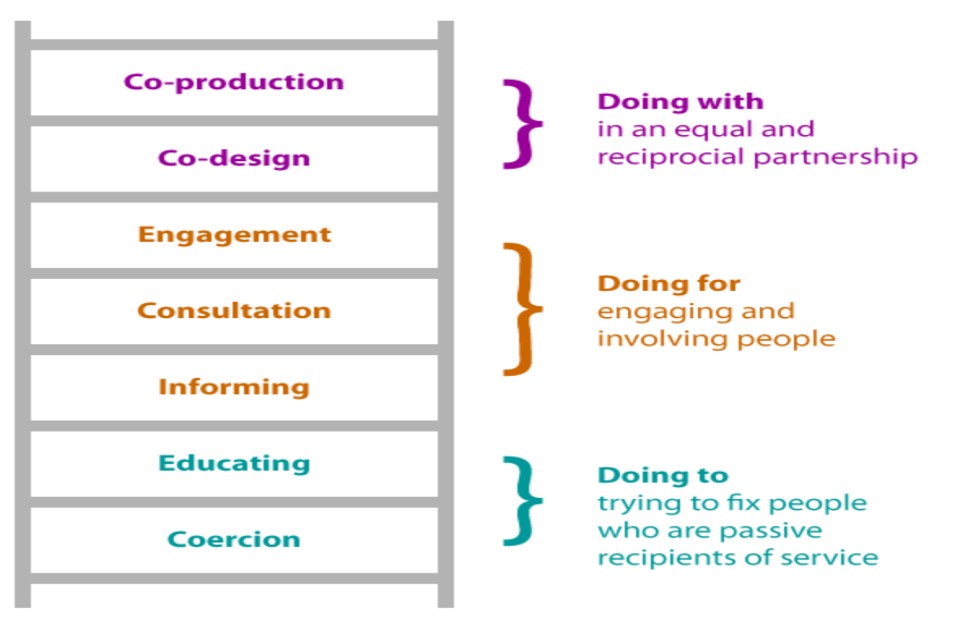

Where is DWP on the ‘ladder of participation’ below?[footnote 21]

Ladder of participation

A way of distinguishing various levels of engagement. There are several different models.

This is this the one we’ve used.

We have limited our research to how the Department involves working age disabled people, and focused in particular on disability benefits like Personal Independence Payments (PIP) and Employment Support Allowance (ESA), and the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) for Universal Credit.

We have not looked at how the Department engages with disabled people on other aspects of Universal Credit (UC).

We have not focused on whether its services are properly accessible – although many people have offered a view on this, which has influenced our findings and recommendations.

Nor have we looked in detail at the Department’s Work and Health Programme, a joint programme with the Department of Health and Social Care to help manage health issues to reduce their impact on work, and support disabled people in finding long-term work – for example through arranging training or contact with employers.

We used several different research methods, including a literature review,[footnote 22] a call for evidence, not least to give individuals who have engaged with DWP a chance to feed in their experience and views, interviews with DWP officials to identify DWP’s policies on involving disabled people, and gain an understanding of specific examples of involvement in practice, observation of a DWP listening event, and interviews and focus groups with external stakeholders.

Our interviews and focus groups were more limited than we had planned because of the COVID-19 national lockdown introduced on 23 March 2020. While we were able to convert several face-to-face focus groups into telephone calls and video-conferences, we had to suspend work on the research for several months – not least because officials in DWP were fully occupied in responding to COVID-19, and because we ourselves redirected our resources to looking at the government’s COVID-19 response[footnote 23].

This has led to gaps in our evidence – principally in seeing how DWP interacts with people at local level, and in their detailed design processes, but also in the range of communities of disabled people with whom we were able to speak. A particular casualty was our ability to undertake the same inquiry in Northern Ireland. Nonetheless, our fieldwork included:

-

Interviews and focus groups with organisations and individual disabled people who have worked with DWP on policy and operational projects

-

Discussions with disability groups in Scotland and Wales on their interaction with DWP, and on how the Scottish government is developing its social security system

-

Local focus groups in local regions in the UK to explore how involvement works at local level

-

Discussions with people who have experience of other sorts of organisations: for example, local authorities, the NHS, the Cabinet Office, Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee, and the recently formed Regional Stakeholder Network which has been established to bring the views of disabled people closer to government

What are DWP’s aims?

We have talked to officials at all levels of seniority throughout DWP, from policy makers in its corporate hubs through to regional and local operational staff responsible for delivering it. Despite their different perspectives, they provided a fairly consistent picture of what they wish to achieve.

One of the principal themes was that the last decade had seen a deterioration in the relationship between DWP and disabled people which was hindering DWP’s ability to improve its services or to meet its policy objectives. The Department told us it wants to eliminate that breakdown. If not, much of the support that could be given to PIP claimants or to disabled people who are not in paid work or under-employed will not happen.

The Department has stated that it wants to deliver a compassionate and effective welfare system for disabled people, providing a supportive environment – e.g. for people with mental health conditions - rather than a system which appears to be solely predicated on fitness for work judgements.

DWP says it needs to have a more joined up approach towards its services, for example, considering streamlining WCA and PIP assessments so that disabled people only have to give core information to the state once – whilst recognising the anxieties of many disabled people if the assessments were actually brought together more fundamentally.

To achieve this DWP officials have told us that they want to do much more in engaging disabled people want to deploy a user-centric perspective in developing policy as well as delivery, and that they are doing so in developing the forthcoming Green Paper.

Over the last year DWP has been working with individual disabled people and disability organisations, to deliver what it describes as operational transformation in 3 key areas:

1. The claimant experience:

A more personalised service, designed in partnership with stakeholders:

-

offering a modern digital experience (whilst continuing to offer support for those claimants who are unable to engage digitally), more empowerment through greater control and visibility of their journeys

-

seeking to reduce anxiety and to increase trust and transparency through better communications and clarity of decisions

2. More effective and efficient service delivery:

- greater automation freeing up time for DWP staff to provide more support for the most vulnerable claimants and complex cases. Better data to provide a richer picture of a claimant’s needs.

2. Greater capability to enable change:

- a flexible delivery model enabling continuous improvement in service delivery and supporting policy change.

At the same time the Department is also considering broader changes to disability benefit policy which it plans to consult on these in its forthcoming Green Paper[footnote 24].

How well do disability organisations and disabled people think DWP is doing?

When the committee asked disability organisations and disabled people for their view of how DWP is delivering against its aspirations, we received a variety of views. Organisations which have recently interacted closely with DWP (mainly large service providing charities) tended to be more positive.

Some local service providers were also fulsome in their praise of the Disability Employment Advisers with whom they worked. Other organisations, particularly disabled people’s organisations and individual respondents were more critical. Some were very suspicious of DWP’s motives.

There is also a time dynamic. The experiences of those we spoke to go back several years, sometimes decades. Therefore, many were commenting on what it had been like in the past, not necessarily on DWP’s current approach.

Some disabled people’s organisations which had previously enjoyed a period of reasonably healthy, if robust, interactions with DWP Ministers and officials subsequently felt ‘frozen out’. Others considered the recent trajectory to be positive.

However, within this variety of perspectives, experiences and views, a number of strong and consistent themes emerged.

Trust

Most of the organisations and individuals we talked to, or who have responded to our consultation, confirm DWP official’s own view that trust of DWP is an issue amongst disabled people. This often derives from personal experiences of PIP, WCA, Universal Credit, or the publicity which surrounds them.

One national charity, a ‘for’ organisation, reported that some of its own disabled clients question whether it should even have meetings with DWP in case the Department misrepresented the evidence provided. Several organisations said that they needed to reassure to the people they were supporting that giving feedback to DWP would not adversely affect their claim.

One General Practitioner who responded to our consultation noted that: ‘I warn patients that whatever illnesses I write or print onto the report it will be completely ignored…When they attend assessments their responses will be ignored and falsely recorded.’

Several respondents argued that this erosion of trust stemmed from the cumulative impact of benefit changes which were designed to reduce spending on disability benefits and the numbers of people who were receiving them.

They began with the Benefits Integrity Project in 1997 which aimed to check the evidence underlying Disability Living Allowance (DLA) claims, followed by the introduction of Employment Support Allowance with its Work Capability Assessment in 2008, and finally the introduction of Personal Independence Payments in 2013, which was intended to reduce spending on DLA by 20%.

Some disability rights activists said that relations completely broke down with government when the conflict over benefit changes was exacerbated further by tensions over the handling of the first report of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Positives

However, many people and organisations which have interacted with DWP are often positive about many aspects of that interaction, especially more recently.

The following quotations speak for themselves:

-

‘The door is now open. DWP used to have a fortress mentality and didn’t feel able to engage. But the Department is now more transparent and, in some parts, reaches out at an earlier stage. So we are asked to help develop options. Not comment on pre-set solutions’ (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘Officials and Ministers have been open to hearing how their policies and processes impact disabled people and people with health conditions’. (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘Contact with DWP led to collaborative working relationships with individuals in DWP which worked well’ (organisation for disabled people). People with these working relationships talked about knowing who to contact in DWP and getting a response to questions or problems. ‘When I raise a specific issue I can speak direct to the civil servant responsible’ (disabled people’s organisation).

-

‘Experience of engaging with DWP at forums has often been constructive; has helped to develop a better understanding of the work the Department is undertaking, and to provide insight, and an opportunity to clearly understand policies and their intent’ (organisation for disabled people).

-

‘The meeting I attended was well run, and its purpose was clear’ (disabled people’s organisation)

-

‘Officials sought my help in planning and organising a listening event with disabled people’ (disabled people’s organisation)

-

‘Many recommendations made in engaging with DWP were implemented.’ (disabled people’s organisation)

-

‘DWP officials are prepared to come to meetings with often hostile audiences to explain DWP policies.’ (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘DWP make sure that people with learning disabilities are included in the design of some of the new documents and letters to ensure that communications with people with learning disabilities are accessible.’ (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘DWP are good at formal consultations on major policy issues’. (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘DWP’s formal evaluation of their programmes are of high quality and take account of the views of users’. (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘At local level DWP partnership managers work well with other partner organisations and are accessible to them’. (organisation for disabled people)

-

‘Disability Employment Advisers form good working relationships with local service providing organisations.’ (organisation for disabled people)

Negatives

We also heard that DWP fell short in other ways. Common themes include the following.

Over-reliance on individual relationships

Once a personal contact within DWP moves on, engagement can break down. More thought needs to be given to continuity of engagement.

Inconsistency

Some parts of DWP are better at engagement than others. There is no common practice throughout the organisation.

We were also told that while DWP consults on all major changes, it often makes minor changes to regulations or procedures without any prior consultation. DWP is open to modifying them at a later date when they receive negative representations, but earlier consultation would be better for all concerned.

Poor feedback

Many participants expressed frustration about DWP’s feedback – both prospective (what will happen next), and retrospective (what did happen).

We were told that it is often unclear at meetings with DWP what is going to happen to the evidence people have provided. One participant at a listening event told us that it was well managed throughout, until the end when a delegate asked what was going to happen with all the contributions DWP had received, and the facilitator was unable to provide a clear answer.

But we heard it is also rare to receive subsequent feedback on what decisions were ultimately made and the rationale for that outcome. Clearly there can often be a considerable gap between DWP being given evidence and a subsequent announcement, and it can also be the case that nothing happens and no announcement is made.

Participants expressed the desire for some form of feedback in these circumstances to close the loop, even if the outturn is disappointing to them.

No-go areas

Participants told us there are also issues on which it seems the Department is unwilling to open a dialogue and hide behind formulaic answers, for example where DWP’s IT systems or clinical assessment partners are involved.

Talking badged as listening

Forums organised by DWP were often described to us as listening to presentations from officials, without much opportunity for a meaningful dialogue on a specific topic. In our own meetings with officials some described engagement as an opportunity to explain DWP’s position, and were less likely to say it was an opportunity to listen to stakeholders.

Inadequate planning

Participants attending DWP meetings have sometimes found that accessibility standards have not been adequate, for example when non-working microphones led to hearing-impaired participants not being able to follow the discussion, or where officials use presentations that are hard to see, or are held in rooms that wheelchair users cannot access.

Many respondents suggested to us that DWP often sets deadlines that are too challenging. For example:

-

organising meetings at short notice (often with an unclear purpose), mean organisations are not always sure who to send or what preparation is needed

-

Setting challenging deadlines to respond to consultations (6 weeks or less), is difficult for all organisations which need to canvass members or their service users. This is particularly difficult for small, grass roots organisations, with limited resources, including disabled people’s organisations.

Organisations that have regular contact with DWP have no sense of a forward business agenda, in contrast with their dealings with some other government departments, local authorities and NHS organisations.

Lack of trust – in both directions

Some respondents said that DWP Ministers occasionally present discussions with organisations as endorsing or co-producing a policy when they had not done so.

‘It is concerning when the Department seeks to represent engagement as an endorsement of a particular policy or process. This approach is not conducive to effective and rigorous engagement, or to building positive relationships on which meaningful engagement can be built in the future’[footnote 25].

Similarly, some organisations believed that decisions had sometimes already been made before consultations had been completed, but that it was politically beneficial to be able to say that consultation had taken place. Both of these erode trust and imply that engagement is seen by the Department simply as a ‘tick-box’ exercise.

Some organisations reported that untrusting behaviour by DWP was getting in the way of a more productive engagement. One observed that being asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement was both insulting and rendered it unable to consult with its supporters to establish whether what was being developed by the DWP would meet their needs.

Another pointed out that the emphasis on trust was limiting DWP’s productive engagement to the organisations they’d always worked with, whilst their lack of trust, even with ‘inner circle’ organisations limited participants’ ability to prepare for discussion or respond to proposals. For example, to prevent leaks papers were often not circulated in advance, and were gathered up at the end of the meeting.

It seems that DWP’s engagement with organisations can occasionally be a substitute for engaging directly with disabled people, but without understanding that disabled people’s organisations need to consult their members, and organisations for disabled people need to engage with disabled people in order to offer well evidenced advice.

A bias towards the ‘big battalions’

DWP has good relationships with the major, well-established national charities, but are less proactive in contacting or building relationships with organisations with whom they are less familiar.

This particularly applies to disabled people’s organisations or user-led organisations, which tend to be local or regional, offer distinct perspectives, or expertise in issues like independent living, and may also represent specific communities, particularly black and minority ethnic groups.

We have spoken to several well-established local organisations who say they have never been approached by local jobcentres for advice, let alone by DWP at a national level.

Several disabled people’s organisations reported that DWP had stopped having any contact from DWP after they had been critical of them or had engaged in legal action against them.

They observed that DWP’s practice was contrary to the UN Convention of Rights of Disabled Persons which requires governments to actively involve disabled people through their representative organisations[footnote 26].

Culture

Several contributors reported that individual officials are normally helpful and responsive and will try to sort out problems raised with them. However, there was a view that they work in an inflexible environment, which limits how responsive they can be – and ultimately the extent it is possible to work as partners. Some suggested that other departments that they interacted with were much more flexible.

One participant put this down to the fact that the majority of DWP is operational in nature. Unusually for government, DWP delivers its own policies and ‘this restricts policy makers’ capacity to think flexibly’.

Access barriers

Some people also told us that accessibility challenges gave an impression that DWP was not interested in them or did not value them or their time.

Examples shared with us include: assessment centres which were difficult to access, difficulties arranging British Sign Language interpreters, and paper-based processes – e.g. for Access to Work – which expected visually impaired people to sign documents they could not read.

Other more general barriers were raised too, for example being put on hold by DWP helplines for an hour or more, and poor digital accessibility in rural areas.

Our findings

Based on our research, the contributions of people we have talked to both inside and outside of DWP, the responses to our call for evidence, and our own observations we have reached the following conclusions.

Finding number 1

DWP has a lot more mechanisms for understanding how disabled people experience social security, and what they think about changing it, than is often assumed.

They include:

a. Generic mechanisms for picking up issues

-

Annual Customer Service and Customer Experience Surveys: disabled people tend to account for a large proportion of the responses received, for example in 2018 to 2019, of the 15,000 responses received by the Department almost 9,000 were submitted by disabled people.

- Regular meetings with national charities of and, in particular, for disabled people[footnote 27].

- Regular forums with national organisations including charities for disabled people.

- Correspondence and representations from individuals and Members of Parliament.

- Ministers’ constituency surgeries and other direct contacts.

b. Particular mechanisms for involving and hearing the voices of disabled people on specific issues.

- Formal consultation processes like green papers on major policy questions.

- Meetings with organisations of and for disabled people to discuss a particular question.

- Meetings, focus groups, listening events with disabled people.

- Steering committees and advisory groups.

- Commissioning organisations and individuals to:

- review departmental programmes (e.g. the independent reviews of PIP and WCA)

- develop new approaches (e.g. the Farmer and Stevenson review of mental health and employers)[footnote 28].

- develop new products (e.g. Possibility People were commissioned to help develop Disability Confident).

- Co-production – though we found no examples in social security.

- Long established user-centred design techniques in developing operational processes using Design Council’s Double Diamond process.

- More recent use of user-centred design in social security policy – particularly in developing the government’s health and disability green paper exploring wider change in the benefits systems.

- Independent, externally commissioned research; For example, in February 2020 DWP published research into the work aspirations, daily lives and support needs of people in the ESA support group and those on Universal Credit in the limited capability for work-related activity category. Based on 50 in-depth face-to-face interviews, 6 focus groups, 4 peer-to-peer interviews and a survey of 2,012 claimants, the research is intended to inform the government’s health and disability green paper[footnote 29].

DWP uses these mechanisms at different times and for different purposes. Many of them are well established – e.g. green papers, focus groups, listening events. Some are new to DWP policy development – for example, user centred design – but widely used in operational development. Some are relatively untried in social security in the UK – like co-production.

c. In Scotland and Wales

DWP has long-established relationships with Welsh and Scottish service providing organisations and have stakeholder groups containing those organisations, with regular Director-level meetings.

d. Locally

- DWP offices have access to Customer Insight systems which use information from a range of sources, including management information, analyses of Universal Credit journal entries, and direct customer feedback.

- Jobcentres may seek views through claimant surveys or inviting claimants to meetings.

- Partnership managers establish and maintain relationships with local organisations from local Public Health organisations responsible for strategic planning to service providers.

- Disability Employment Providers have their own networks.

- Every site has a Place Based Toolkit, effectively a summary of local needs, allowing offices to tune their response to local priorities. Sites use contacts with local organisations to inform this.

- DWP’s Health Model Office Project has created a network of eleven Jobcentre Plus Model Offices that test different ways of engaging with disabled customers. These are intended to build trust, and encourage voluntary participation in employment support.

DWP use different techniques at different stages of the policy development process:

- Problem exploration and developing possible solutions – user-centred design, commissioning independent reviews.

- Refining proposed solutions – green papers, user centred design.

- Evaluating whether a programme has worked – research, customer experience surveys.

- Some of these are techniques for listening at scale, and tend to be broad brush.

- Some work best with small numbers of people working intensively on specific issues.

Some mechanisms involve DWP talking to and listening to disabled people directly - in which case DWP needs to consider whether it has listened to a sufficiently diverse spread of disabled people, or whether it has overlooked groups who might be particularly affected.

It should also consider whether it has included disabled people who are often overlooked in disability-related discussions, such as homeless disabled people.

Some mechanisms mean that DWP hears the views of disabled people through intermediaries – researchers, independent reviewers, or policy leads of organisations.

This may be useful in itself, and essential where disabled people are reluctant to engage personally with DWP officials. But there is no substitute for engaging people directly.

It is also important that DWP considers whether the intermediaries themselves are listening to a diverse enough spread of disabled people; or whether they are over-filtering views. And of course if the Department is only involving intermediaries then it cannot claim it is co-producing policies, plans or services directly with disabled people.

Example of the stages in policy to implementation lifecycle

The following example shows the stages that a fairly typical review process might go through:

1. The Coalition government in December 2010 asked Liz Sayce then the Chief Executive of RADAR, the largest national pan-disability organisation led by disabled people, to review disability employment support.

2. After receiving her report [footnote 30]in June 2011 the government published its initial reactions and consulted on her proposals[footnote 31].

3. The Disability and Health Employment Strategy[footnote 32], published in 2013, set out a vision for future specialist disability employment support including greater personalisation and more choice for disabled people in the support they receive.

4. Following this, the Personalisation Pathfinder trial was introduced in April 2015.

5. Researchers were commissioned to evaluate the trial, and their report was published in June 2018[footnote 33]. The results were based on surveying 3,326 participants, and 90 in-depth qualitative interviews with participants, as well as in-depth focus groups with stakeholders.

This was not co-production by any means. But it was a relatively open process; which at several stages offered ways for disabled people to make their views and influence the government. It was not uncontentious.

And some of the Sayce recommendations were fiercely criticised by some disabled people[footnote 34]. But debate and disagreement does not of itself mean that government is not listening and acting on what it hears.

DWP therefore regularly uses many mechanisms for understanding how its programmes are experienced by disabled people. But:

- Is it genuine?

- Is DWP actually listening and hearing?

- Is the Department acting on what it hears?

- How far are disabled people co-designing or co-producing policy or operational processes?

- Is it working? Is it leading to demonstrable improvements?

The following sections explore these questions in more detail.

Finding number 2

From the above evidence we’ve seen, talking to officials, and observing a listening event we can conclude that the intention to engage is genuine.

We are clear, from many meetings with different senior officials in DWP, that they:

-

acknowledge there are issues with PIP, with WCA, and with the support they want to offer disabled people to get into and sustain employment. They are also aware that the lack of trust limits the extent to which they can improve the service DWP provides. It also makes disabled people reluctant to engage with work coaches and the employment help DWP can offer.

-

are committed to engaging with disabled people to understand these problems fully and to find solutions.

-

are currently doing this in developing the health and disability green paper, and in designing improvements to the way the Personal Independence Payment and the Work Capacity Assessments operate.

However, it is not clear that this is yet part of the DNA of DWP, and organisations who have regular contact with the Department suggested to us that it is patchy. It appears to be much more part of the way that the Health Transformation Programme and the Green Paper process operate than in other areas.

Nor is it clear that this is how DWP intends to operate on all its programmes – whether with disabled people specifically or all people affected by its services. It is making a concerted effort now in some parts of the organisation, but will that be maintained or extended to all parts of the Department’s business?

Finding number 3

DWP is listening, but could be listening more effectively.

In its preparatory work ahead of its forthcoming health and disability green paper, DWP has held listening events in many different parts of the country, designed to pick up views from disabled people who are not normally reached by government consultations.

Previous exercises like this have in the past tended to be based in big cities, requiring disabled people to travel. This process has been much more geographically spread.

They have also deployed their user-centred design expertise to drill down into user needs, to define the problem and start to develop solutions. They have started work with a group of stakeholder organisations to test out some of the design issues at a more strategic level.

An Assessment Advisory Panel is also helping them think through how to make assessment processes more effective. This is composed of academics, organisations of and for disabled people and others.

However, inevitably, there are improvements that can be made. Several officials told us they were not sure how far they could go in opening up potential policy options for discussion.

It was also apparent that some officials, who were confident when working with their contacts in professional stakeholder organisations, were not sure how to go about setting up productive conversations with claimants who were not used to having policy discussions.

The lack of a structure is also evident in other areas:

-

DWP does not seem to have a clear strategy for knowing whether they have engaged all groups of disabled people, or whether there are some that they have not reached and, if so, which. Nor do they seem to have a methodology for reaching them. BAME groups appears to be a major lacunae and, given they are not that difficult to engage (Public Health England’s listening exercise in May this year heard about the impact of COVID-19 from 4,000 mainly BAME people in 17 stakeholder events)[footnote 35], we wondered how the Department is going to reach other disabled people with poor communication channels and or skills, for example homeless disabled people.

-

The Department’s dependence on big national charities appears to be related to this. It needs to build (or in some cases rebuild) relationships with smaller disabled people’s organisations. We therefore welcome the fact that the Cabinet Office Disability Unit has recently established a Disabled People’s Organisations Forum, chaired by the Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work, which will enable DWP to re-engage with a broader group of user-led organisations again. We understand the first meeting discussed plans for the Health and Disability Green Paper.

-

Neither do DWP’s IT systems support a fine-grained approach. We were told that, with some exceptions, limitations in the way that information about claimants is captured, coded and stored, mean it is difficult for DWP to use its claimant data to understand how people with particular impairments, or belonging to particular minority groups fare in its programmes. This is evident in many of the equality analyses we see.

-

At local level, our (limited) sampling suggests that the Department can have really good networks with local partner organisations – but they tend to be service delivery organisations, in some cases funded by the jobcentre. In other words, organisations that DWP works with to provide support to their shared clients; not other organisations which might offer a different perspective. We have met local, long established, organisations of disabled people who are actively engaged with local social service departments or NHS providers, who say they have never been approached by their local jobcentre. And these are organisations that we have managed to reach, despite very modest resources.

-

When the Department’s partnership or stakeholder managers have talked us through their stakeholder analysis, they tend to show that organisations are valued for what use they can be to DWP in getting its messages across (e.g. explaining to claimants how to use the social security system) or how influential they are. How good they are at representing the views of disabled people does not seem to be so strong a factor.

Does listening inform what DWP does?

Finding number 4

It is hard to be definitive on how far DWP is acting on what it hears.

The forthcoming health and disability green paper is work in progress for DWP, so on this particular question it is too early to say. The essence of user-centred design processes is that design happens interactively with users. So if DWP are deploying the process properly, then the answer ought to be yes.

DWP officials also convincingly describe how it operates. However, we have not had an opportunity to observe the process and, as DWP does not routinely publish what happens inside the design process, we have had to accept this on trust.

However, user-centred design is only one of the ways in which DWP is involving or listening to disabled people. DWP has given us examples of policy and other changes being made as a direct result of feedback gained in discussions with disabled people. One example cited was how information provided by Macmillan Cancer Support helped shape and strengthen the support in place for cancer patients.

The clearest example of tangible improvement following engagement with the Department is the development of a prototype within the UC programme to improve how people provide third party consent.

In response to this feedback, and in line with a recommendation made by the Social Security Advisory Committee (SSAC), the Department developed a prototype which will sit within the UC journal and is intended to allow claimants to provide consent quickly and easily.

Macmillan Cancer Support

Another example shared with us was the appreciation that people with autism can find jobcentres difficult places to be, and so need appointments at quiet times and preferably in a calm part of the office. All jobcentres have been asked to assess the changes they need to make to make their service more accessible to people with autism.

We were also told that linking the PIP and WCA assessment processes would stand a good chance of improving the quality of both – and relieve people from having to repeat information they’ve already given.

Objectively it could improve claimants’ experience and lead to better decisions being made. However, some disabled people reacted negatively to this, questioning DWP’s intentions.

So the Department is being very careful about how this possible improvement is being tested and developed.

Finding number 5

At different times, and in different contexts, DWP has operated at all the rungs of the ladder of participation.

| Ladder of participation |

|---|

| Co-production |

| Co-design |

| Engagement |

| Consultation |

| Informing |

| Educating |

| Coercion |

In non-social security contexts, like its health and work programme, it is much more likely to work in a fully participative way. And it has several times developed policies and procedures using co-production or co-design – e.g. working with disabled and employer representatives to develop Disability Confident.

In social security policy and operational design, it is normally in the middle ‘Doing For’ tier, ranging from informing to high levels of engagement. Disabled people are actively participating in the operational design process. But the process is managed by DWP officials.

At a more strategic level, a senior DWP official has described the current process as ‘participative design’. It is not co-production as that means shared decision taking and responsibility. However, in the current reform context, there is clearly a high degree of engagement.

Finding number 6

It is too early to say how far this is leading to demonstrable improvements.