Country policy and information note: female genital mutilation (FGM), Nigeria, July 2022 (accessible)

Updated 12 August 2022

Version 3.0

July 2022

Preface

Purpose

This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme.

It is split into 2 parts: (1) an assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below.

Assessment

This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note - that is information in the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw - by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies:

-

a person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm

-

that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

-

that the security situation is such that there are substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm because there exists a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules

-

a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

Country of origin information

The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency and traceability.

The structure and content of the country information section follows a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to this note.

All information included in the note was published or made publicly available on or before the ‘cut-off’ date(s) in the country information section. Any event taking place or report/article published after these date(s) is not included.

All information is publicly accessible or can be made publicly available. Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include:

- the motivation, purpose, knowledge and experience of the source

- how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used

- the currency and detail of information

- whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources.

Multiple sourcing is used to ensure that the information is accurate and balanced, which is compared and contrasted where appropriate so that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture is provided of the issues relevant to this note at the time of publication.

The inclusion of a source is not, however, an endorsement of it or any view(s) expressed.

Each piece of information is referenced in a footnote. Full details of all sources cited and consulted in compiling the note are listed alphabetically in the bibliography.

Feedback

Our goal is to provide accurate, reliable and up-to-date COI and clear guidance. We welcome feedback on how to improve our products. If you would like to comment on this note, please email the Country Policy and Information Team.

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

The Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI) was set up in March 2009 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration to support him in reviewing the efficiency, effectiveness and consistency of approach of COI produced by the Home Office.

The IAGCI welcomes feedback on the Home Office’s COI material. It is not the function of the IAGCI to endorse any Home Office material, procedures or policy. The IAGCI may be contacted at:

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

5th Floor

Globe House

89 Eccleston Square

London, SW1V 1PN

Email: chiefinspector@icibi.gov.uk

Information about the IAGCI’s work and a list of the documents which have been reviewed by the IAGCI can be found on the Independent Chief Inspector’s pages of the gov.uk website.

Assessment

Updated: 13 July 2022

1. Introduction

1.1 Basis of claim

1.1.1 Fear of persecution and/or serious harm by non-state agents because:

(a) there is a reasonable degree of likelihood that girl/woman will be subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM); or

(b) the person is a parent who is opposed to FGM where there is a real risk of it being carried out on their daughter.

1.2 Points to note

1.2.1 Sources may use various terms to refer to FGM, including female circumcision, female genital circumcision or female genital cutting, which may be abbreviated to FGC or FGM/C. For the purposes of this note, the practice is referred to as FGM (see Definition and types of FGM).

1.2.2 Statistical information referenced in this assessment is largely drawn from the Nigeria Demographic Health Surveys (NDHS) of 2013 and 2018, and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) of 2017, undertaken by the Nigerian government with support from international aid agencies, as these are the most recent, comprehensive and authoritative sources on prevalence of FGM across the population (see Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys).

1.2.3 Parents cannot be dependants on a minor child’s asylum claim. You must therefore consider whether, on the basis of the facts in the individual case, accompanying parents qualify for refugee status on the basis of a well-founded fear of persecution in their own right. This may be either as a member of a PSG (accompanying parents of a daughter at risk of FGM) or for other reasons in the country of return. You must consider the relevant country policy and information notes and each case must be considered on its individual merits. You must establish whether the parents are opposed to FGM, explore why they would not be able to protect their daughter from a real risk of enforced FGM and consider whether there is sufficiency of protection or if internal relocation is reasonable. The case of K and others (FGM) Gambia CG [2013] established that where claimants are granted refugee status the accompanying parents may also be eligible for a grant of leave. If the accompanying parents do not qualify for protection you must consider whether discretionary leave is appropriate.

1.2.4 General guidance on considering FGM is available in the Asylum Instructions, Gender Issues in Asylum Claims, and the Multi-Agency statutory guidance on FGM.

2. Consideration of issues

2.1 Credibility

2.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

2.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider the need to conduct language analysis testing (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: End of section

2.2 Exclusion

2.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

2.2.2 If the person is excluded from refugee status under Article 1F, they will also normally be excluded from Humanitarian Protection.

2.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: End of section

2.3 Convention reason(s)

2.3.1 Women and girls, including those in fear of FGM, form a particular social group (PSG) in Nigeria within the meaning of the Refugee Convention because they share an innate characteristic or a common background that cannot be changed, or share a characteristic or belief that is so fundamental to identity or conscience that a person should not be forced to renounce it and have a distinct identity in Nigeria because the group is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

2.3.2 Although women and girls in Nigeria, including those fearing FGM, form a PSG, establishing such membership is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question to be addressed is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of their membership of such a group.

2.3.3 For further guidance on Convention reasons see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.4 Risk

2.4.1 Whether a woman or girl is at real risk of undergoing FGM will depend on her personal circumstances. There are various factors that affect the prevalence rates of FGM across the population, which may overlap but age, ethnicity, and education appear most important. The factors to be considered by decision makers when assessing risk include:

-

ethnicity, including taking into account high levels of intermarriage

-

the prevalence of FGM amongst the extended family and local community

-

home region and whether they live in an urban or rural area

-

family history of FGM, particularly whether the girl’s mother has been subject to FGM

-

religion

-

wealth

-

age

-

level of education

2.4.2 Each case will need to be considered on its facts, with the onus on the applicant to demonstrate that they are at a real risk of FGM.

2.4.3 A parent of girl or woman who is opposed to/rejects her undergoing FGM may experience social pressure and stigmatisation from their family and/or community. In general, this treatment is unlikely to amount to persecution or serious harm but each case must be considered on its facts (see Society and family and Opposing FGM).

2.4.4 Around a fifth of women have experienced FGM. The available data indicates a general trend towards a reduction in the prevalence of FGM, although this trajectory seems to have slowed in the youngest cohorts, if not reversed (see Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, Mothers’ background and Age when FGM is performed).

2.4.5 FGM is mostly carried out on girls between the ages of 0 and 15 years and involves ‘nicking’ of the clitoris and/or some flesh removed (the most common type of FGM in Nigeria). Other forms of FGM include infibulation (narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal), ‘angurya cuts’ (scraping of tissue surrounding the opening of the vagina) and ‘gishiri cuts’ (cutting of the vagina). The large majority of girls and women experience FGM by ‘traditional midwives’, with less than 10% undertaken by medical professionals (see Type of FGM practised in Nigeria and Age when FGM is performed).

2.4.6 Generally, the majority of women undergo FGM before the age of 5. Of the 20% of women estimated to have undergone FGM, 86% of women aged 15-49 experienced FGM before the age of 5. However the ages at which women are subject to FGM can vary (see Age when FGM is performed).

2.4.7 Girls and women of all faiths are subject to FGM. FGM was most prevalent amongst Catholics with 24.8% having been subject to FGM in 2018, and those holding traditional beliefs lowest at 11.9% (also having experienced the largest decline from 2013 when 34.8% had experienced FGM) (see Religion).

2.4.8 According to NDHS 2018 data FGM prevalence was highest among Yoruba and Igbo women at 34.7% and 30.7% respectively, a significant decline from 2013 when 55% and 45% respectively were reported to have had FGM. Prevalence among Hausa is 20%, Fulani 13% and Ekoi in the South East is 12% (with the latter being reported as having the largest fall in FGM rates, down from 56.9% in 2013). By comparison FGM was rarer among Igala (0.9%) and Tiv (0.8%) women who mostly live in the south and central belt of the country (see Ethnic group).

2.4.9 FGM prevalence varies but is slightly higher in urban than rural areas. Women living in urban areas are more likely than rural women to have experienced FGM (24% and 16% respectively). The prevalence of FGM is highest in the South East (35%) and South West (30%) and lowest in the North East (6%). While girls 0-14 years old living in rural areas (21%) are reported to have a higher incidence of FGM for that age range compared to girls in urban areas (16%). However, prevalence by place of residence is not necessarily an indicator of where FGM is carried out, as a woman may have lived in a different area at the time she underwent FGM (see Residence/zone).

2.4.10 A girl’s/woman’s mother’s education has a significant bearing on whether she is subject to FGM. The NDHS 2018 survey showed that daughters of women with more than secondary education (8%) are less likely than daughters of women with no education (24%) to have been subject to FGM (see Prevalence: By education).

2.4.11 A girl’s/woman’s wealth (or that of her family) does not appear to be a significant factor in the likelihood of FGM. There are similar FGM rates across the 5 income quintiles identified in the NDHS, with lowest rates of 16.4% amongst the lowest (poorest) quintile, highest rates (22.6%) amongst the fourth (second wealthiest) quintile in 2018. However, FGM rates were reported to have dropped most significantly in the highest and fourth quintiles, falling by around a third between 2013 and 2018) (see Wealth quintile).

2.4.12 No information could be found in the sources consulted to suggest that repeat FGM is practised in Nigeria (see Bibliography).

2.4.13 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.5 Protection

2.5.1 The state is generally willing and/or able to provide protection, and is accessible to girls or women in fear of FGM. However, this will depend on the capability of the criminal justice system to enforce the law in that territory or state. This is because not all states outside of the Federal Capital Territory of Abuja have introduced legislation criminalising FGM and/or, in some areas, the state lacks capacity to maintain the rule of law because of high rates of general insecurity.

2.5.2 FGM is criminalised under federal law and by some, but not all, states. The federal government introduced the Violence against Persons (Prohibition) Act in 2015 which criminalises FGM. According to a VAPP tracker, 19 of the 36 states outside of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) have introduced laws that make FGM illegal in their territories, although the penalties vary (see Law and policy).

2.5.3 Each case will need to be considered on its particular circumstances. A person’s reluctance to seek protection does not mean that effective protection is not available. The onus is on the person to demonstrate that the state is not willing and able to provide them with effective protection.

2.5.4 The Nigerian government has put in place a criminal justice system that is generally capability of providing protection to persons who fear non-state actors (see country and policy information note on Nigeria: Actors of Protection).

2.5.5 The Nigerian government has enacted laws to eliminate the practice of FGM, such as the VAPP Act, banning FGM/C and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV). The VAPP Act applies within the Federal Capital Territory, however it still needs to be passed in each of the 36 states, as not all have yet introduced legislation criminalising FGM (see Federal law, State law and Policies and strategies).

2.5.6 Nigeria has also adopted the Maputo Protocol (African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa) and has addressed FGM through its National Policy and Plan of Action for Elimination of FGM/C in Nigeria. However, sources indicate that Nigeria lacked specific guidelines for the prevention and management of FGM/C (see Law and policy).

2.5.7 However, implementation of the law varies across the country and depends on state and federal police capacity, willingness and understanding of anti-FGM legislation. Sources report that there is sometimes a lack of awareness amongst the police and other state actors involved in enforcement and protecting victims about law on FGM. NGOs have found that they have to convince local authorities that state laws apply in their districts. Police are also reported to treat the practice as a family or community affair, meaning that survivors often remain with the perpetrator, and where police respect the tradition themselves, may not intervene at all, while there are low rates of reporting given that family members are often the perpetrators and to date there have been no prosecutions. Sources also observe that the police rarely implemented the law, with the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs in its report covering the period June 2018 to March 2021 stating that there had been no prosecutions or convictions for FGM in this period (see Police capability and response and country and policy information note on Nigeria: Actors of Protection).

2.5.8 COVID-19 has also had a negative impact on legal services. This has resulted in survivors of FGM experiencing significant delays in accessing justice and legal protections and the closure of some shelters. The laws are harder to enforce in rural areas where there is limited police presence and activity (see Police capability and response and country and policy information note on Nigeria: Actors of Protection).

2.5.9 There are several Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in Nigeria that work to reduce the practice of FGM. However, NGO and state run shelters for women or girls fearing FGM are generally inadequate, and sources indicate that support is limited (see Support groups and shelters).

2.5.10 In some parts of the country, the capacity of the Nigerian State to provide effective protection is limited, in particular in the states of Borno, Adamawa, Yobe, Plateau, Benue, Nasarawa, Taraba, and Zamfara (see Police capability and response).

2.5.11 For further guidance on assessing the availability of state protection, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.6 Internal relocation

2.6.1 In general, a girl or women who fears FGM, or a family who refuse to allow their daughter to be subject to FGM, may be able to internally relocate to escape localised threats from other members of their family or other non-state actors. Whether it is viable for a girl/women, or a family, to relocate will depend on their background, personal circumstances and available support network in the place of relocation. Each case must be considered on its facts (see the country policy and information notes on Nigeria: Internal Relocation)

2.6.2 For further guidance on internal relocation see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.7 Certification

2.7.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

2.7.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

Section 3 updated: 12 July 2022

3. FGM context

3.1.1 It should be noted that as reported by UNICEF in August 2021:

‘Nationally representative data on FGM/C are mainly available from two sources: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS)…

‘The first indicator for measuring FGM/C prevalence is the percentage of girls and women of reproductive age (15 to 49) who have experienced any form of the practice. This is derived from self-reports. Typically, girls and women are also asked about the type of FGM/C performed, at what age they were cut and by whom…

‘The second indicator used to report on the practice measures the extent of cutting among daughters of girls and women of reproductive age (15 to 49)…

‘A key point to be kept in mind is that the prevalence data for girls aged 0 to 14 reflect their current, but not final, FGM/C status, since some girls who have not been cut may still be at risk of experiencing the practice once they reach the customary age…

‘Self-reported data on FGM/C needs to be treated with caution for several reasons. First, women may be unwilling to disclose having undergone the procedure because of the sensitivity of the topic or the illegal status of the practice. In addition, they may be unaware that they have been cut or of the extent of the cutting, especially if FGM/C was performed at an early age. …

‘Information on the FGM/C status of daughters is generally regarded as more reliable than women’s self-reports, since any cutting would have occurred relatively recently and mothers presumably would have had some involvement in or knowledge of the event. However, even these data need to be interpreted with a degree of caution. Mothers may be reluctant to disclose the actual FGM/C status of their daughters for fear of repercussions, especially in countries where the practice has been the target of campaigns or legal measures to prohibit it.’[footnote 1]

3.2 Definition and types of FGM

3.2.1 The World Health Organisation (WHO) gives the following definition of FGM: ‘Female genital mutilation (FGM) involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.’[footnote 2]

3.2.2 In a January 2022 online article, WHO classified FGM into 4 major types:

‘Type 1: this is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals), and/or the prepuce/ clitoral hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans).

‘Type 2: this is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without removal of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

‘Type 3: Also known as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoral prepuce/clitoral hood and glans.

‘Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.’[footnote 3]

3.2.3 According to the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS 2018) Type 4 FGM includes: ‘… pricking, piercing, or incising of the clitoris and/or labia; stretching of the clitoris and/or labia; cauterization by burning of the clitoris and surrounding tissue; scraping of tissue surrounding the opening of the vagina (angurya cuts) or cutting of the vagina (gishiri cuts); and introduction of corrosive substances or herbs into the vagina to cause bleeding or to tighten or narrow the vagina.’[footnote 4]

3.2.4 See also Points to note and for details of how FGM has no health benefits along with a list of complications that can arise following FGM see World Health Organisation, ‘Female Genital Mutilation: Key facts’, 21 January 2022

3.3 Type of FGM practised in Nigeria

3.3.1 The table below documents the most common type of FGM in Nigeria and shows the percentage distribution of women who had FGM by type of FGM. Data is taken from the National Bureau of Statistics/United Nations Children’s Fund (NBS/UNICEF) Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2016-17. The results show that the most common type of FGM is Type 1 and 2 which both involve some form of cutting and removal of the female genital area[footnote 5]

| Type of FGM | % of women 15-49 who had been subject to FGM | % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM |

|---|---|---|

| Cut, flesh removed | 61.8 | 76.6 |

| Nicked | 3.4 | 7.5 |

| Sewn closed | 4.9 | 5.3 |

| Don’t know/missing | 29.8 | 10.6 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

3.3.2 The table below compiled using the National Population Commission (NPC) 2 most recent surveys - Nigeria Demographic Health Survey (NDHS 2018) and NDHS survey 2013 (NDHS surveys)[footnote 6][footnote 7]shows the percent distribution of girls aged 0-14 who had been subject to FGM, by current age and women aged 15-49, according to type of FGM.

| Type of FGM | 2013: % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM | 2018: % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM | 2013: % of women 15-49 who had been subject to FGM | 2018: % of women 15-49 who had been subject to FGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sewn closed | 2.7 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 5.6 |

| Not sewn closed | 92.5 | 96.5 | 77.4 | 77.7 |

| Don’t know/missing | 4.9 | 0 | 17.3 | 16.8 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

3.3.3 The NDHS 2018 survey stated:

‘The most common type of FGM in Nigeria is Type II (some flesh removed), with 41% of women undergoing this procedure. Ten percent of women underwent a Type I procedure (clitoris nicked, no flesh removed), and 6% underwent a Type III procedure (also known as infibulation)…

‘… According to researchers, three major forms of FGM are practiced in Nigeria: female circumcision, hymenectomy (angurya), and gishiri cuts …’ [footnote 8]

The NDHS 2018 survey collected additional information on different types of circumcision procedures women have undergone, particularly procedures that are unclassified. All women who had been circumcised were asked whether they had experienced angurya (hymenectomy), gishiri, or use of corrosive methods to narrow the virginal tract. The findings showed that

-

‘40% of women who had been circumcised had angurya performed, while

-

‘13% had gishiri cuts…

-

7% experienced use of corrosive substances…’[footnote 9]

3.3.4 The NDHS 2018 survey also

‘… included questions to ascertain the prevalence of various types of FGM among daughters. Women who said their daughter was circumcised were asked whether her genital area had been sewn closed (a process known as infibulation)…

-

‘4% of girls in Nigeria have been infibulated.

-

‘Girls from the Kanuri and Beriberi ethnic groups are most likely to have been infibulated (10%).

-

’Girls whose mothers had experienced infibulation were more likely to have undergone the procedure themselves (44%) than girls whose mothers were circumcised but not infibulated (2%) and girls whose mothers are not circumcised (4%).’ [footnote 10]

3.4 Actors of harm – who performs FGM

3.4.1 The table below compiled using data from the 2 most recent NDHS surveys shows the percent distribution of girls who had been subject to FGM aged 0-14 by current age and women aged 15-49, according to person performing the FGM[footnote 11][footnote 12]:

| Person who performed the FGM | 2013: Girls 0-14 | 2018: Girls 0-14 | 2013: Women 15-49 | 2018: Women 15-49 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional agent | 86.6% | 92.8% | 79.5% | 85.4% |

| Medical professional | 11.9% | 7.0% | 12.7% | 8.6% |

| Don’t know/missing | 1.5% | 0.1% | 7.9% | 6.0% |

3.4.2 The data from the above table shows that almost 93% of girls who had been subject to FGM between the ages of 0 and 14 had experienced FGM by a traditional agent, which includes traditional circumcisers 82.4%, traditional midwives 7.5% and other traditional agents 2.9% in 2018, an increase of just over 6 per centage points from 2013. This figure was 85.4% for women between 15 and 49 years old (traditional circumciser 75.7%, traditional midwives 8.4%, other traditional agent 8.6%), an increase of almost 6 per centage points from 2013[footnote 13].

3.4.3 The proportion of FGM conducted by medical professionals declined in both age ranges between 2013 and 2018, from 11.9% to 7% for girls aged 0-14 and 12.7% to 8.6% for women aged 15 to 49 respectively[footnote 14].

3.4.4 Nurses and midwives carried out the majority of FGM carried out by medical professionals who accounted for 6.5% (girls 0-14) and 7.7% (women 15-49)[footnote 15].

3.4.5 The DFAT country information report of December 2020, based on a range of public and non-public available sources including on-the-ground knowledge and discussions with a range of sources, stated: ‘There are no reports that FGM/C has occurred without the consent of parents.’ [footnote 16]

3.4.6 The EASO country guidance, updated October 2021, and based on COI found in section 4.2.9 of EASO Country Focus report 2017 stated: ‘The final decision whether to circumcise their daughter is most often with the parents, but there is a considerable variation both individually and among different ethnic groups whether it is the father or the mother who makes this decision. The grandparents or the eldest female on the paternal side may also have a decisive role…’ [footnote 17]

3.4.7 A Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MofFA) COI report on Nigeria, published in March 2021, covering the reporting period June 2018 to March 2021 and citing various sources, stated

‘In most cases involving young girls, the parents decide whether or not their daughters will be circumcised… Sources consulted for this report had differing views on whether fathers or mothers had more influence on the decision whether or not to circumcise a daughter. Several confidential sources emphasised that mothers play a vital role in the decision in favour of FGM for their young daughters… There is also a strong link between whether a not a mother is circumcised and the likelihood that a daughter will be circumcised.

‘Several sources indicated that fathers rather than mothers played a decisive role in this choice… Based on 40 interviews with parents and health professionals from four states, the Population Council concluded that while mothers were responsible for arranging circumcision, fathers played a key role in the decision about FGM… The study suggested that mothers did not allow their daughters to undergo FGM without the father’s consent… One confidential source confirmed this observation,… and also stated that if a father wanted his daughter to undergo FGM but the mother did not, the daughter would probably be circumcised anyway.

‘However, several sources of this country of origin information report indicated that there were cases where young girls were circumcised without parental consent, at the instigation of grandmothers. Confidential sources indicated that they knew of cases in which grandmothers played a decisive role in the decision to have a girl circumcised by putting pressure on mothers and fathers to have their daughters circumcised… One confidential source knew of a specific example from 2019 where a step-grandmother in Borno had her two granddaughters circumcised after the mother died… This source also estimated that in south-eastern Nigeria, in about one in 15 cases it was the extended family or wider community that determined whether a girl would be circumcised. According to this source, this happened when parents themselves were financially or otherwise unable to take care of their children and had thus in practice lost control over their children… The negative impact that grandmothers can have on the probability of a granddaughter being circumcised was also acknowledged by Emmanuel Abah, the director of the National Orientation Agency (NOA) in Ebonyi in an article in Business Day in 2020… The Population Council study from 2018 also referred to grandmothers’ considerable influence over decision-making about FGM, citing an example where a grandmother took her granddaughter to be circumcised against the mother’s will.’[footnote 18]

3.4.8 An Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRBC) response to information request update from October 2021 and citing various sources stated:

‘…In an interview with the Research Directorate, the Executive Director of Safehaven Development Initiative (SDI), a Nigerian NGO that provides support services to vulnerable women and girls through education on “issues of sexual and reproductive health, HIV/AIDS, malaria, human rights and gender-based violence”…, stated that “most of the time” the paternal grandparents will “order [FGM/C] to be done” and the “grandmother always has the upper hand” and the mother “does not have the right to question her”…’ [footnote 19]

3.4.9 The same source stated:

‘According to the Research Analyst, “[i]t also depends on the family structure and the relationships that exists”… The same source further stated that if the family is detached from their extended family, then only the mother and father make the decision, while also noting the power dynamic between the mother and the father are an important factor with Nigeria being “a very patriarchal society where even decisions pertaining to health and wellbeing are made solely by the male partner”… In an interview with the Research Directorate, the Executive Director of Value Female Network, a Nigerian NGO working to end the practice of FGM/C in Osun state …, noted that the decision goes beyond the family and involves the “community and society”; it would be challenging for parents to refuse as they would be seen as “not complying with the community” … However, the same source added that “it varies from community to community”…’[footnote 20]

3.5 Medicalisation of FGM

3.5.1 28 Too Many Nigeria: The Law and FGM’, June 2018 noted that ‘The VAPP [The Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act, 2015] Act does not clearly address FGM carried out by health professionals or in a medical setting; the broad nature of the law, however, would suggest that any member of the medical profession who performs or assists in FGM would also be guilty of a criminal offence and punished accordingly.’[footnote 21]

3.5.2 The Population Council published paper ‘Understanding Medicalisation FGM/C: A Qualitive study of parents and health workers in Nigeria’, January 2018, noted that:

‘Despite the local and international call to abandon the practice, there is evidence that some Nigerian families, instead of abandoning the practice outright, are opting for medicalised forms. Medicalisation of FGM/C involves the use of health care providers-doctors, nurses/midwives, or other health professionals-to perform the practice either at facilities or at home…

‘Although medicalisation is presumed to reduce the risk of complications, it does not eliminate them and does not alter the fact that FGM/C is a violation of women’s and girls’ rights to life, health, and bodily integrity. Medicalisation accounts for 12.7 percent of FGM/C practice in Nigeria [based on the DHS survey from 2013]. There is minimal information on medicalisation in Nigeria beyond the prevalence rates available in the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS). Additionally, there is limited understanding of how medicalisation has evolved or is evolving in Nigeria especially as it relates to the prospect of abandonment. The context of decision-making and rationale around medicalisation for families and health workers and the effect of medicalisation on the severity of cutting is also poorly understood…

‘Contrary to widely held views that medicalisation occurs because parents are knowledgeable about the health risks of FGM/C and are attempting to mitigate them through the use of health professionals, we found that parents reported being unaware of FGM/C’s possible physical and psychological complications but chose to use health workers because they perceived them as more careful, knowledgeable, skilled, and hygienic when dealing with any health related matter. Health workers were also viewed as providing more options in cases of emergency and complications. Due to the early age at cutting, typically during infancy, the choice of FGM/C provider was often tied to the type of birth attendant (health worker or traditional birth attendant) who delivered the child. The dynamics of convenience, trust, and cost saving drove the choice of birth attendants. For some parents, FGM/C was offered to them as part of routine neonatal care services. The transition to medicalisation in these communities may be an unintended consequence of improved health seeking behaviours and safe birthing messages.

‘Although health workers were more knowledgeable than parents about the risks of FGM/C, they performed FGM/C mostly because they shared the same beliefs as community members, on its supposed benefits and perceived approval (or lack of disapproval) by their professional peers.’[footnote 22]

3.5.3 In the UNFPA-UNICEF, ‘Reflections on Phase II of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation’ 2018, it was stated that:

‘Nigeria is one of the five countries with the highest rates of FGM medicalization in the world. Parents turning to trained health workers to avert the health concerns of FGM has become more common, especially in more developed countries.

‘The increase in medicalization among Nigerian girls in younger cohorts suggests the trend is not improving. Moreover, a study of 250 health workers in south-western Nigeria found that almost half had been asked to perform FGM. About a fourth of 182 nurses in Benin City, Nigeria reported that some forms of FGM are not harmful, with 2.8 per cent supporting the practice. In the same sample, well over half of respondents (57.7 per cent) reported that they would still perform FGM in certain circumstances, such as under significant pressure from a girl’s or woman’s family, for significant financial benefits or to prevent patients from going to traditional cutters.’[footnote 23]

3.5.4 The report continued to state that:

‘To counteract these tendencies, service providers have been given relevant information, education and communication materials. But clearly this is an area where more progress is needed. Part of the planned strategy to address medicalization in the third phase of the Joint Programme is to engage more with medical associations and regulatory bodies at national, state and community levels. In addition, the Joint Programme will scale up the use of community and health surveillance systems to monitor health workers.’[footnote 24]

3.5.5 However, data from both the 2013 and 2018 DHS surveys, as shown in section 3.4 Actors of harm – who performs FGM, indicates that the practice of FGM being carried out by a medical professionals has declined for both girls and women. CPIT was not able to find more recent information on the current rate of medicalisation of FGM in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

3.5.6 WHO in a December 2019 online article stated:

‘The World Health Organization (WHO)and partners are harmonizing efforts by the Nigerian Government to put a stop to the medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

‘Speaking further on the topic, Dr Christopher Ugboko, the Division Head of Gender, Adolescent/School Health and Elderly Care (GASHE) unit, Federal Ministry of Health said, “The revised National Policy on the elimination of FGM (2020 – 2024) has mapped out roles for health workers, health regulatory bodies, professional health associations and other stakeholders to prevent FGM in Nigeria.”

‘He added, ”Specific strategies include wide sensitization and awareness creation, capacity building of health workers as well as setting up of surveillance systems to detect such practices amongst medical personnel. The Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) law has prescribed sanctions against persons implicated in FGM and its medicalization.”’[footnote 25]

Section 4 updated: 12 July 2022

4. Prevalence of FGM

4.1 Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys

4.1.1 The most comprehensive sources of data on the prevalence of FGM in Nigeria is the National Population Commission (NPC) - Nigeria Demographic Health Survey (NDHS 2018) and The National Bureau of Statistics/United Nations Children’s Fund (NBS/UNICEF), Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2016-17). Both reports are widely cited by several of the sources used (see sources consulted in the Bibliography).

4.1.2 The most recent NDHS survey and data collection took place in 2018 and was published in October 2019. This report also uses the NDHS survey 2013. The DHS Program is funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and used a ‘representative sample of approximately 42,000 households … for the survey.’[footnote 26]

4.1.3 The 2018 NDHS survey noted that: ‘Although the prevalence of FGM in the 2018 NDHS cannot be compared with the prevalence in NDHS surveys before 2013 due to variations in definitions, a comparison can be made with the results of the 2013 NDHS as both surveys used the same definition.’ [footnote 27]

4.1.4 Data is limited as observed by an Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRBC) response to information request update from October 2021, and citing various sources, however the MICS/NDHS surveys as mentioned above in this section have undertaken good quality sampling. IRBC stated:

‘In correspondence with the Research Directorate, the Campaign Leader of the No-FGM Campaign, a campaign against FGM/C in Akwa Ibom State … wrote that

‘“[t]he practice of FGM is a hidden one. There is an express ban on the practice so persons who perpetrate this act do it discreetly. The level of prevalence is measured by how many victims get to speak up and because of this, there are not too many public accounts of FGM available. There are many victims but their unwillingness to speak up accounts for the unavailability of statistics.”’ [footnote 28]

4.2 Overview

4.2.1 The NDHS 2018 found that overall 20% of women aged 15-49 years had undergone FGM, this has dropped from 25% in 2013, with a decline in all age cohorts between 15 to 49[footnote 29]. There has also been a decline in FGM rates between generations, with girls aged 15 to 19 less than half as likely (just under 14%) to have experienced FGM compared with 31% of women aged 45-49 in 2018[footnote 30][footnote 31]. However, NDHS 2018 data did show a slight increase in girls aged 0-14 having experienced FGM from 16.9% in 2013 to 19.2% in 2018, but which is still much lower than rates reported in women aged 45 to 49[footnote 32][footnote 33]. When considering this data it should be noted that FGM can occur at different points in a woman’s life, so the prevalence of girls in the 0-4 cohort who have experienced FGM will not be the final number of girls in that generation who are circumcised.

4.2.2 However, according to the NBS/UNICEF, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2016-17, published in February 2018, a lower rate of women who had undergone FGM was recorded:

-

MICS found that the overall rate of women 15-49 years old who were recorded to have experienced FGM was 18.4%, which is lower than the rate of 20% found in the NDHS survey conducted in 2018.

-

Meanwhile, the percentage of daughters 0-14 years old who have experienced FGM was reported to be 25.3% in the 2016-2017 MICS, almost 6% higher than the figure reported in the subsequent NDHS survey conducted in 2018.

-

Rates for older cohorts tended to be lower than the NDHS 2018 data although there was a similar increase in occurrence with age. The table below breaks the data further down into age ranges[footnote 34].

| Age | % Women and daughters who have had any FGM/C | Number of women/girls aged 0-49 | Number of women/girls who have had FGM/C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 | 26.6 | 7,265 | 1,936 |

| 5-9 | 23.9 | 5,709 | 1,363 |

| 10-14 | 25.1 | 4,556 | 1,144 |

| 15-19 | 12.3 | 6,822 | 8,42 |

| 20-24 | 15.4 | 5,816 | 8,96 |

| 25-29 | 16.9 | 5,915 | 1,000 |

| 30-34 | 20.1 | 5,390 | 1,084 |

| 25-39 | 21.3 | 4,339 | 924 |

| 40-44 | 24.4 | 3,571 | 871 |

| 45-49 | 27.6 | 2,524 | 696 |

4.2.3 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 35][footnote 36], shows the percentage distribution of girls aged 0-14 by age who had undergone FGM.

| Current age | % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM: 2013 | % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM: 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| 0-4 | 15.9 | 19.0 |

| 5-9 | 17.5 | 19.3 |

| 10-14 | 17.8 | 19.5 |

| Total | 16.9 | 19.2 |

4.2.4 UNICEF in a February 2022 press release referred to the increase in girls who had FGM from 16.9% in 2013 to 19.2% in 2018 as a ‘worrying trend’[footnote 37].

4.2.5 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 38][footnote 39], shows the prevalence of FGM in women in 5 year cohorts aged between 15 and 49 who had been subject to FGM:

| Background characteristic | 2013 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 15-19 | 15.3 | 13.7 |

| 20-24 | 21.7 | 15.9 |

| 25-29 | 22.9 | 18.0 |

| 30-34 | 27.4 | 19.7 |

| 35-39 | 30.4 | 21.9 |

| 40-44 | 33.0 | 26.7 |

| 45-49 | 35.8 | 31.0 |

| Total | ||

| Total number of women | 38,948 | 26,705 |

| Number of women who had been subject to FGM | 9,652 | 5,202 |

4.2.6 The above data for 2018 indicates that there is a decrease in the prevalence of FGM between NDHS surveys, with just under 14% of women aged 15 to 19 having undergone FGM compared to over twice that number of women aged 45-49 (31%)[footnote 40].

4.2.7 An Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRBC) response to information request update from October 2021 and citing various sources stated: ‘In an interview with the Research Directorate, the Director of the Centre for Women’s Studies and Intervention (CWSI)… stated that FGM/C is “not prevalent now” and “has been decreasing,” but that it is difficult to change the culture…’[footnote 41]

4.2.8 In contrast to this view, a UNICEF article from February 2022 stated: ‘Female genital mutilation (FGM) remains widespread in Nigeria. With an estimated 19.9 million survivors, Nigeria accounts for the third highest number of women and girls who have undergone FGM worldwide.’[footnote 42]

4.3 Age when FGM is performed

4.3.1 The table below compiled using data from the 2 most recent NDHS surveys[footnote 43][footnote 44]showed that:

| Age when FGM occurred | 2013 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| % Women who had been subject to FGM before they were 5 years old | 82 | 83 |

| % FGM between 5 and 9 years | 4 | 4 |

| % FGM between 10 and 14 years | 5 | 4 |

| FGM between 15 and older | 7 | 5 |

4.3.2 The 2018 NDHS asked women with female children at what age their daughters had been subject to FGM, the survey showed that 17% were subject to FGM before they celebrated their first birthday, compared to 15.8% in 2013[footnote 45][footnote 46].

4.3.3 The NDHS 2018 report also noted:

-

‘Women less than age 25 are more likely than women aged 45-49 to have been circumcised before age 5 (91%-92% versus 79%).

-

‘Nine in 10 women (92%) of Islamic faith were circumcised before age 5, as compared with 77% of women of Catholic faith.

-

‘By zone, the proportion of women circumcised before age 5 is highest in the North West (97%) and lowest in the South South (59%). A quarter (24%) of circumcised women in the South South had the procedure done at age 15 or later.’[footnote 47]

4.3.4 Among ethnic groups in age at FGM the NDHS 2018 report stated:

-

96.6% of Hausa women and 86.2% of Fulani women underwent the procedure before age 5.

-

62.9% of Ijaw/Izon women were subject to FGM at age 15 or older[footnote 48].

4.3.5 A Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MofFA) COI report on Nigeria, published in March 2021, covering the reporting period June 2018 to March 2021 and citing various sources, commented: ‘The first periods/signs of puberty, prior to marriage and during pregnancy/childbirth are the main trigger points for FGM in teenagers and adult women…’[footnote 49]

4.3.6 With regards to FGM during pregnancy or childbirth, the same source stated:

‘FGM also occurs during pregnancy and childbirth, according to several confidential sources… In the south FGM during pregnancy is more common, whereas in the north yankan gishiri (the making of incisions in the vaginal wall) is practised during childbirth… Research for this report found no evidence that FGM was practised after childbirth. According to a confidential source, there are also several reasons for the use of FGM during pregnancy/childbirth in northern and southern Nigeria. In the south, according to confidential sources, FGM is mainly used to protect the male baby against the ‘evil influence’ of the clitoris during childbirth… In the north, circumcisers apply yankan gishiri before and during childbirth to make it quicker and easier… In reality, it does not have these effects, and the use of yankan gishiri can lead to serious complications such as obstetric fistulas that can cause general incontinence… A confidential source stated that the use of this practice was partly due to the lack of professional midwives and health care services in this region…’[footnote 50]

4.3.7 The same source commented: ‘No information was available on the fate of uncircumcised girls and women who returned to Nigeria after their asylum application had been rejected. Given that the ages at which women are circumcised vary, it is difficult to assess whether a woman is at no or less risk if she has passed the ‘usual age of circumcision’ by the time she returns.’ [footnote 51]

4.4 Religion

4.4.1 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 52][footnote 53], shows the percentage of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM, by the background characteristic of religion:

| Religion | 2013 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 31.4 | 24.5 |

| Other Christian | 29.3 | 19.4 |

| Islam | 20.1 | 18.7 |

| Traditionalist | 34.8 | 11.9 |

| Other | - | 2.2 |

| Total | ||

| Total number of women in sample | 38,948 | 26,705 |

| Number of women who had been subject to FGM in sample | 9,652 | 5,202 |

4.4.2 The above data shows that FGM was practised across all religions. Data from the NDHS Survey 2013 showed that FGM was most prevalent among women practising traditionalist religions (34.8% of women aged 15–49) and the least prevalent among Muslim women (20.1%)[footnote 54].

4.4.3 However, the NDHS Survey from 2018 showed that FGM was most prevalent among women practicing Catholicism (24.5%) and the least traditionalist at 11.9%[footnote 55]. In both NDHS surveys less than 1% of respondents were traditionalists, it is not clear from the data why there has been a 23% decrease in the prevalence of FGM among women practising traditionalist religions.

4.4.4 The NDHS 2018 survey found ‘Among women who have heard of FGM, 78% believe that female genital mutilation is not required by their religion and 67% believe that it should not be continued.’[footnote 56]

4.4.5 Nnanatu and others in a PLoS ONE publication combining data from multiple NDHS and MICS surveys found: ‘[There was a] (h]igher likelihood of undergoing FGM/C [in Nigeria] were found among girls whose mothers believed that FGM/C was a religious obligation and prevents premarital sex.’[footnote 57]

4.4.6 UNICEF observed on an FGM webpage updated in June 2021 stated: ‘FGM is not endorsed by Islam or Christianity, but religious narratives are commonly deployed to justify it.’[footnote 58]

4.4.7 In a January 2022 online article, WHO stated:

‘Some people believe that the practice has religious support, although no religious scripts prescribe the practice. Religious leaders take varying positions with regard to FGM: some promote it, some consider it irrelevant to religion, and others contribute to its elimination. Local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice. Likewise, when informed, they can be effective advocates for abandonment of FGM. In most societies, where FGM is practised, it is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation.’[footnote 59]

4.5 Ethnic group

4.5.1 The NBS/UNICEF, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2016-17, February 2018 shows the following data with regard FGM by ethnic group. The figures suggest that FGM is experienced more commonly by Yoruba women aged 0-49 but is more prevalent for Hausa girls 0-14[footnote 60][footnote 61][footnote 62].

| Ethnicity of household head | % Women who have had any form of FGM/C | % Girls who have had any form of FGM/C |

|---|---|---|

| Hausa | 13.9 | 38.6 |

| Igbo | 29.2 | 11.3 |

| Yoruba | 45.4 | 27.3 |

| Other | 8.3 | 8.3 |

4.5.2 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 63][footnote 64], shows the percentage of women ages 15-49 who had experienced FGM, by the background characteristic / ethnicity of household head ethnic group:

| Ethnic group | NDHS 2013 | NDHS 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Ekoi | 56.9 | 11.6 |

| Fulani | 13.2 | 12.6 |

| Hausa | 19.4 | 19.7 |

| Ibibio | 12.8 | 9.3 |

| Igala | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Igbo | 45.2 | 30.7 |

| Ijaw/Izon | 11.0 | 6.9 |

| Kanuri/Beriberi | 2.6 | 5.6 |

| Tiv | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Yoruba | 54.5 | 34.7 |

| Others | 13.4 | 10.0 |

| Don’t know/Missing | 14.8 | - |

| Total | ||

| Total number of women | 38,948 | 26,705 |

| Number of women who had been subject to FGM | 9,652 | 5,202 |

4.5.3 The NDHS 2018 survey found that all ethnic groups practise FGM, and the highest prevalence of FGM is among Yoruba women (34.7%) (but there had been a significant drop from 54.6% in 2013), followed by Igbo women (30.7%) (amongst whom there had also been a significant decline from 45.2% in 2013). The lowest prevalence is among Tiv and Igala women (1% each)[footnote 65]. NDHS 2018 also stated: ‘Girls from the Kanuri and Beriberi ethnic groups are most likely to have been infibulated [genital area sewn closed]’ although rates amongst this group were relatively low at 5.6% (albeit one of only 4 ethnic groups where an increase in FGM had been documented between 2013 and 2018) [footnote 66]

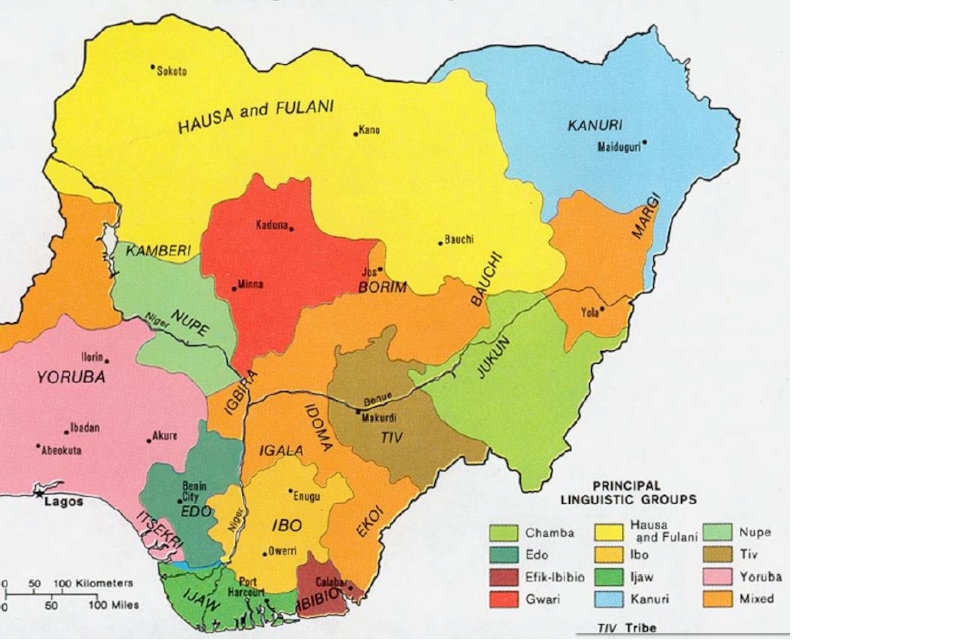

4.5.4 A Map of Nigeria Ethnolinguistic groups reproduced below is available on the Perry Castaneda Library Map Collection webpage.

The map shows that the largest groups are Hausa and Fulani, Kanuri, and Yoruba.

4.6 Residence / zone

4.6.1 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 68][footnote 69], shows the percentage of women aged 15-49 who had experienced FGM, by the background characteristic of residence and zonal region group:

| Residence | 2013 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Urban | 32.3 | 24.2 |

| Rural | 19.3 | 15.6 |

| Zone / State | 2013 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| North Central | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| FCT – Abuja | 5.1 | |

| Benue | 5.3 | |

| Kogi | 1.0 | |

| Kwara | 46.0 | |

| Nasarawa | 1.8 | |

| Niger | 10.5 | |

| Plateau | 3.0 | |

| North East | 2.9 | 6.1 |

| Adamawa | 0.0 | |

| Bauchi | 10.7 | |

| Borno | 2.4 | |

| Gombe | 0.1 | |

| Taraba | 3.9 | |

| Yobe | 14.2 | |

| North West | 20.7 | 20.2 |

| Jigawa | 34.1 | |

| Kaduna | 48.8 | |

| Kano | 22.2 | |

| Katsina | 1.4 | |

| Kebbi | 1.6 | |

| Sokoto | 5.4 | |

| Zamfara | 5.3 | |

| South East | 49.0 | 35.0 |

| Abia | 12.2 | |

| Anambra | 21.4 | |

| Ebonyi | 53.2 | |

| Enugu | 25.3 | |

| Imo | 61.7 | |

| South South | 25.8 | 17.7 |

| Akwa Ibom | 10.2 | |

| Bayelsa | 6.7 | |

| Cross River | 11.9 | |

| Delta | 33.7 | |

| Edo | 35.5 | |

| Rivers | 9.3 | |

| South West | 47.5 | 30.0 |

| Ekiti | 57.9 | |

| Lagos | 23.7 | |

| Ogun | 8.2 | |

| Ondo | 43.7 | |

| Osun | 45.9 | |

| Oyo | 31.1 | |

| Total | ||

| Total number of women | 38,948 | 26,705 |

| Number of women who had been subject to FGM | 9,652 | 5,202 |

4.6.2 The NDHS 2018 survey found that FGM was lower in rural areas (16%) than in urban areas (24%). Prevalence was highest in the South East (35%) and South West (30%) and the lowest in the North East (6%). Imo State has the highest prevalence, at 62%, followed by Ekiti (58%), Ebonyi (53%) and Kaduna (49%). Prevalence was lowest in Adamawa and Gombe with 0% and 0.1% respectively[footnote 70]. Adamawa had a nil response with regard the number of women who had been subject to FGM. The Federal Capital Territory of Abuja, where the VAPP act applies had a rate of 5.1% [footnote 71](see Law and policy).

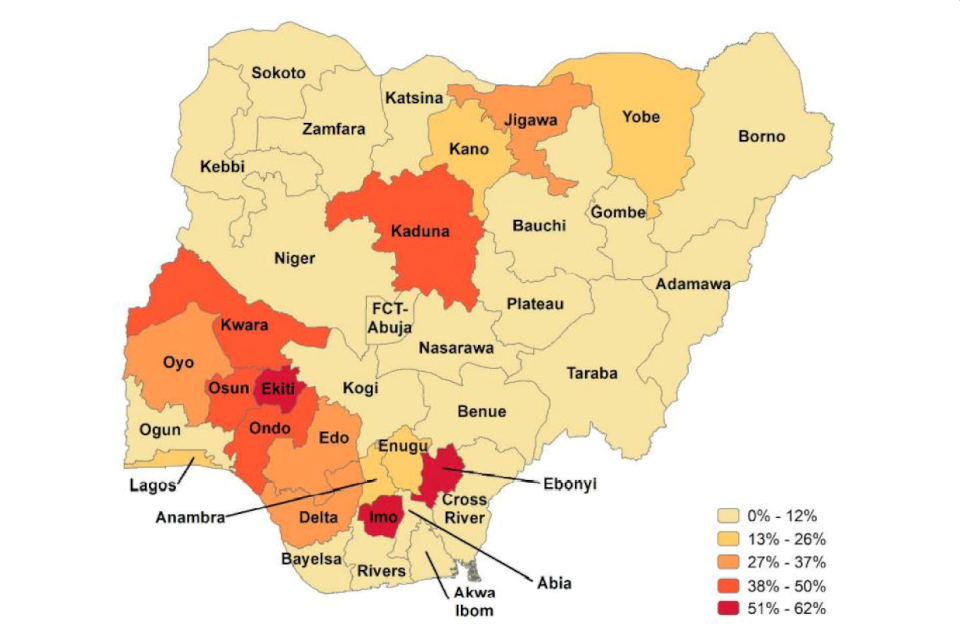

4.6.3 The map below charts the percentage of women aged 15-49 who have been subject to FGM by State:

The map shows that the states with the highest percentage of FGM (51% to 62%) are Ebonyi, Ekiti and Imo. The second highest (38% to 50%) are Kaduna, Kwara, Ondo and Osun. Delta, Edo, Jigawa and Oyo: 27% to 30%. Anambra, Enugu, Kano, Lagos and Yobe: 13% to 26%. All other states: 0% to 12%.

4.6.4 28 Too Many in an FGM report from December 2019, based on the MICS 2016/17 data stated: ‘The majority of Nigeria’s population (57%) live in rural areas. The most densely populated Zone, with 30% of Nigeria’s population, is North West…’[footnote 72]The same source also noted with regard data reliability and regional prevalence in an earlier report: ‘Prevalence by place of residence is not necessarily an indicator of where FGM is carried out, as a woman may have lived in a different area at the time she underwent FGM. This is particularly relevant in relation to the urban/rural split, as girls or women now living in urban areas may have undergone FGM in their familial village and relocated upon marriage…’[footnote 73]

4.7 Wealth quintile

4.7.1 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 74][footnote 75], shows the percentage of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM, by the background characteristic of wealth quintile and also the percentage of those by wealth quintile who have heard of FGM:

| Wealth quintile | % of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM: 2013 | % have heard of FGM: 2013 | % of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM: 2018 | % have heard of FGM: 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest (wealth) | 16.5 | 64.6 | 16.4 | 57.9 |

| Second | 20.3 | 61.4 | 17.8 | 51.8 |

| Middle | 23.5 | 60.5 | 20.0 | 57.7 |

| Fourth | 30.6 | 70.5 | 22.6 | 64.6 |

| Highest (fifth) | 31.0 | 78.0 | 20.0 | 70.0 |

4.7.2 The above data for 2018 shows that the prevalence of FGM is highest among wealthier women in Nigeria (20%), and that those women with the highest wealth quintile are more knowledgeable about FGM (70%). There has been a fall in prevalence among women across all wealth quintiles between 2013 and 2018 NDHS surveys. The fourth and fifth quintiles of women experienced the highest drop in prevalence of FGM.

4.7.3 The NDHS 2018 survey noted: ‘…those in the highest wealth quintile are least likely to believe that FGM is required by their religion.’[footnote 76]

4.8 Education

4.8.1 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 77][footnote 78], shows the percentage of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM, by the background characteristic of education and the percentage of those by education who have heard of FGM:

| Education | % of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM: 2013 | % have heard of FGM: 2013 | % of women ages 15-49 who were subject to FGM: 2018 | % have heard of FGM: 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No education | 17.2 | 64.0 | 17.2 | 55.5 |

| Primary | 30.7 | 67.0 | 25.6 | 62.5 |

| Secondary | 28.8 | 67.2 | 19.4 | 60.9 |

| More than secondary | 29.1 | 84.3 | 19.5 | 74.9 |

4.8.2 The above data for 2018 shows that the prevalence of FGM is similar among women who have received secondary and more then secondary levels of education. It also shows that those with a higher level of education are more knowledgeable about FGM (75%) than those who have had a secondary education (61%) or no education (55%). There has been a fall in prevalence among women who have been educated at primary and above levels with those women who have been educated to secondary and above levels experiencing the highest drop in prevalence of FGM. Prevalence rates between 2013 and 2018 have remained the same for women who have no education.

4.8.3 The NDHS 2018 survey noted

-

‘Women … with more than a secondary education (75%) are more knowledgeable about FGM than those … with no education (56%).

-

‘The percentage of women who have had angurya cuts declines with increasing education, from 71% among those with no education to 18% among those with more than a secondary education.

-

‘…Women with more than a secondary education … are least likely to believe that FGM is required by their religion.’[footnote 79]

4.9 Mothers’ background

4.9.1 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 80][footnote 81], show the percentage of women ages 0-14 who are subject to FGM according to mothers background characteristic:

| Mother’s background characteristic | % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM, according to mother’s background characteristic: 2013 | % of girls 0-14 who had been subject to FGM, according to mother’s background characteristic: 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| No education | 19.3 | 24.4 |

| Primary education | 16.3 | 16.7 |

| Secondary | 14.2 | 14.1 |

| More than secondary | 9.3 | 7.5 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 16.8 | 16.3 |

| Rural | 17 | 21.1 |

| Religion | ||

| Catholic | 10.2 | 10.0 |

| Other Christian | 10.6 | 8.1 |

| Islam | 21.0 | 25.1 |

| Traditionalist | 11.0 | 1.8 |

| Other | 13.6 | 0.0 |

| Ethnic group | ||

| Ekoi | 3.0 | 1.2 |

| Fulani | 16.1 | 25.4 |

| Hausa | 26.0 | 29.1 |

| Ibibio | 0.9 | 2.5 |

| Igala | - | 0.4 |

| Igbo | 18.2 | 13.5 |

| Kanuri/Beriberi | 4.0 | 12.7 |

| Tiv | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Yoruba | 28.9 | 17.2 |

| Others | 4.6 | 9.0 |

| Don’t know/Missing | - | - |

| Zone | ||

| North Central | 4.1 | 7.6 |

| North East | 4.8 | 20.7 |

| North West | 27.0 | 28.6 |

| South East | 20.7 | 15.5 |

| South South | 6.6 | 5.3 |

| South West | 22.9 | 13.2 |

| Wealth Quintile | ||

| Lowest (wealth) | 19.4 | 26.6 |

| Second | 20.4 | 20.8 |

| Middle | 14.9 | 18.8 |

| Fourth | 15.6 | 16.4 |

| Highest (fifth) | 12.6 | 9.8 |

4.9.2 The above data shows that daughters of women with more than a secondary education (7.5%) are less likely than daughters of women with no education (24.4%) to have been subject to FGM[footnote 82].

4.9.3 The above data also shows some increases in the prevalence of FGM in girls who are subject to FGM, according to age and mother’s background characteristics. Girls whose mothers were resident in the North East rose from 4.8% in 2013 to 20.7% in 2018. Increases can also be seen where the girls’ mothers lived in rural areas, from 17% in 2013 to 21.1% in 2018, and mothers who had no education from 19.3% to 24.4%. An increase and reduction can be seen between the two NDHS surveys within ethnic groups, where the mothers’ ethnicity was Fulani, where there was an increase from 16.1% (2013) to 25.4% (2018), and Ijaw/Izan 0.3% to 12.7%. Decreases were seen amongst mothers were Igbo (18.2% to 13.5%) and Yoruba (28.9% to 9%).

4.9.4 The table below, compiled using data from the 2 most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys[footnote 83][footnote 84], show the percentage of women ages 0-14 who are subject to FGM according to mothers’ FGM status:

| Mother’s FGM status | % of girls 0-14 who are subject to FGM, according to mother’s background characteristic: 2013 | % of girls 0-14 who are subject to FGM, according to mother’s background characteristic: 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Subject to FGM | 47.4 | 55.9 |

| Not subject to FGM | 8.0 | 16.6 |

| Don’t know/missing | 23.4 | - |

4.9.5 The above data shows that daughters whose mothers have had FGM are more likely to be subject to FGM themselves (56%), compared to 17% of girls whose mothers have not been subject to FGM[footnote 85]. It is not clear from the data whether there is an actual increase in FGM rates between 2013 and 2018 given that 23.4 % of girls responses are either a ‘don’t’ know’ or ‘missing’.

4.9.6 The 2018 NDHS survey stated: ‘The 2018 NDHS asked women with female children whether their daughters aged 0-14 had been subject to FGM and, if so, at what age. Eighty-one percent of daughters have not been subject to FGM, while 17% were subject to FGM before they celebrated their first birthday.’ [footnote 86]

4.9.7 The 2018 NDHS survey also found: ‘25% of girls aged 0-4 whose mothers are Muslims have been subject to FGM.’[footnote 87]

4.10 Repeat FGM

4.10.1 The Netherlands MofFA COI report on Nigeria, published in March 2021 and citing various sources, stated in respect of the possibility of repeat FGM practised during childbirth:

‘None of the publications consulted for this report mentioned any cases in which women were subjected to FGM again during a second or third delivery. Confidential sources indicated that they were not aware of such a practice… Yankan gishiri could in theory be repeated in consecutive deliveries. It was not known whether this occurred in practice. One confidential source indicated that women who had already undergone infibulation (the most severe form of circumcision) needed to be cut open before childbirth and then ‘constricted’ again… In such cases, incision is necessary for the child to be born at all.’[footnote 88]

4.10.2 CPIT was not able to find further specific information on repeat FGM in Nigeria in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

Section 5 updated: 12 July 2022

5. Law and policy

5.1 Federal law

5.1.1 28TOOMANY’s ‘Nigeria: The Law and FGM’, June 2018, citing the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999), noted:

‘The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999) does not specifically refer to violence against women and girls, harmful traditional practices or FGM; Articles 15(2) and 17(2) prohibit discrimination and set out equality of rights respectively, and Article 34(1) provides that every individual is entitled to respect for the dignity of their person and, accordingly, no one shall be subject to torture, or to inhuman or degrading treatment.

‘The Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act, 2015 (the VAPP Act), which came into force on 25 May 2015, is the first federal law attempting to prohibit FGM across the whole country. The VAPP Act aims to eliminate gender-based violence in private and public life by criminalising and setting out the punishment for acts including rape (but not spousal rape), incest, domestic violence, stalking, harmful traditional practices and FGM…’[footnote 89]

5.1.2 The VAPP Act 2015 prohibits female circumcision, making it a federal offence, and includes the following penalties:

‘6(1) The circumcision or genital mutilation of the girl child or woman is hereby prohibited.

‘6(2) A person who performs female circumcision or genital mutilation or engages another to carry out such circumcision or mutilation commits and offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 4 years or to a fine not exceeding N200,000.00 [£368[footnote 90]] or both.

‘6(3) A person who attempts to commit the offence provided for in subsection (2) of this section commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 2 years or to a fine not exceeding N100,000.00 [£184[footnote 91]] or both.

‘6(4) a person who incites, aids, or counsels another person to commit the offence provided for in subsection (2) of this section commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 2 years or to a fine not exceeding N100,00.00 [£184[footnote 92]] or both.’[footnote 93]

5.1.3 28TOOMANY’s ‘Nigeria: The Law and FGM’, June 2018 observed that: ‘The VAPP Act does not provide a clear definition of FGM; Section 6(1) of the law opens with the simple statement, “The circumcision or genital mutilation of the girl child or woman is hereby prohibited.” …

‘The VAPP Act does not expressly criminalise failure to report FGM that has taken place or is due to take place.’[footnote 94]

5.1.4 The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) 2020 Annual Report on FGM: Country Case Studies - Progress in the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation (UNFPA 2020 Annual Report on FGM) explained: ‘…, the VAPP Act does not explicitly address FGM carried out by health care providers or in a medical setting; the broad nature of the law, however, would suggest that any member of the medical profession who performs or assists in FGM would also be guilty of a criminal offence and punished accordingly.’[footnote 95]

5.1.5 The Population Council – FGM 2020 report further stated: ‘…Nigeria’s ratification of international and regional human rights instruments however means that where laws are not being enforced to protect women and girls, it is possible for the Federal State of Nigeria to be held responsible for failure to protect women’s rights under the Maputo Protocol …’ [footnote 96]

5.1.6 The USSD Human Rights report 2021 stated: ‘Federal law criminalizes female circumcision or genital mutilation, but there were few reports that the government took legal action to curb the practice. ‘The law penalizes persons performing female circumcision or genital mutilation or anyone aiding or abetting such a person. Enforcement of the law was rare.’[footnote 97]

5.2 State law

5.2.1 28TOOMANY’s ‘Nigeria: The Law and FGM’, June 2018, citing the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999), noted

‘Nigeria has a federal system of government comprising 36 states, and a mixed legal system of English common law, Islamic law (in 12 northern states) and traditional law. The legal system is complex and both levels of government play a role in the enactment of laws prohibiting FGM in Nigeria: although the federal government is responsible for passing general laws, the state governments must then adopt and implement them in their respective states…’[footnote 98]

5.2.2 28TOOMANY in a December 2019 publication stated ‘In May 2015, a federal law was passed in Nigeria banning FGM and other harmful practices, but [the] Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act only applies to the Federal Capital Territory of Abuja. It is up to each of the 36 states to pass similar legislation in its territory. 13 states already have similar laws in place; however, there remains an inconsistency between the passing and enforcement of laws.’[footnote 99]

5.2.3 The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) 2020 Annual Report on FGM: Country Case Studies - Progress in the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation (UNFPA 2020 Annual Report on FGM) explained: ‘… the VAPP Act, as a federal law, is only effective in the Federal Capital Territory of Abuja, and, as such, the remaining states must pass mirroring legislation to prohibit FGM across the country. Prior to the VAPP Act, several states had already enacted state laws dealing with child abuse, child protection issues, violence against women and girls and criminalizing the practice of FGM, requiring harmonization of laws.’[footnote 100]

See also Actors of harm – who performs FGM

5.2.4 A Population Council review of FGM policy and law in Nigeria from June 2020 stated: ‘An example of legislation passed by individual state is the FGM Prohibition Law of 2017, in Imo State with the aim of prohibiting FGM/C and other related matters. The law has provisions that prohibit/criminalise FGM/C regardless of custom or tradition. The Act defines offences and punishments for performing of FGM/C…’[footnote 101]

5.2.5 The Population Council – FGM 2020 report further stated: ‘… several states are yet to take legislative measures to mirror the federal legislation.’ [footnote 102]

5.2.6 A Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MofFA) COI report on Nigeria, published in March 2021, covering the reporting period June 2018 to March 2021 and citing the online VAPP Tracker [Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative (Partners West Africa Nigeria (PWAN)] stated that 17 states had adopted the federal VAPP law[footnote 103]. This differs from 13 states cited by other sources. Further, the VAPP tracker at the time of writing shows that 19 of the 36 states outside the FCT have introduced laws that make FGM illegal in their territories[footnote 104].

5.2.7 The USSD Human Rights report 2021 stated ‘While 13 of 36 states banned FGM/C, once a state legislature had criminalized FGM/C, NGOs found they had to convince local authorities that state laws applied in their districts.’[footnote 105]

5.3 Policies and strategies

5.3.1 The Population Council in the February 2020 report - Female genital mutilation/cutting in Nigeria: Is the practice declining? A descriptive analysis of successive demographic and health surveys and multiple indicator cluster surveys (2003–2017) (Population Council – FGM 2020), and citing a variety of sources, commented:

‘Nigeria has responded to the international call for the elimination of FGM/C in several important ways. … Along with other African states, Nigeria also adopted the Maputo Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol) in 2003, ensuring that survivors of GBV and of gross human rights violations can obtain redress before a domestic or regional court such as the Court of Economic Community of West Africa States or ECOWAS… Further, an inter-ministerial department committee launched the 2013/2017 National Policy and Plan of Action for Elimination of FGM/C in Nigeria…’[footnote 106]

5.3.2 A Population Council review of FGM policy and law in Nigeria from June 2020 stated:

‘In Nigeria, FGM/C is addressed through a nationwide policy titled the National _Policy and Plan of Action for the Elimination of FGM of 2013–2017 … as well as other sector-specific policies including: the National Gender Policy of 2006, the National Policy on the Health and Development of Adolescents and Young People of 2007, and the National Reproductive Health Policy of 2017 … This review’s main focus is on the National Policy and Plan of Action for the Elimination of FGM of 2013–2017…

‘In Nigeria only the National Policy and Plan of Action for the Elimination of FGM defines the practice as per the WHO guidelines. The policy is aligned with the global and national legal/policy contexts that address FGM/C on the premise of respect for human rights as a guiding principle and as a medico-social issue. The policy is within the framework of the National Gender, Health, and Strategic Development Plan in Nigeria. It outlines the response from government and civil society organisations to include community-level education, capacity-building for stakeholders on the negative impact of FGM/C, advocacy for legislation and treatment of FGM/C complications, intersectoral collaboration and integration of anti-FGM/C programmes in relevant sectors, and anti-FGM/C legislation at state levels…’ [footnote 107]

5.3.3 The same Population Council report stated:

‘In Nigeria the National Strategic Framework on the Health and Development of Adolescents and Young People in Nigeria 2007–2011, National Gender Policy Strategic Framework (Implementation Plan) 2008–2013, and the Plan of Action component of the national policy were examined. The Plan of Action for the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation in Nigeria (2013–2017) had relevant FGM/C-related prevention and management components…