Country policy and information note: military service, Egypt, March 2023 (accessible)

Updated 2 January 2024

Version 2.1

March 2023

Preface

Purpose

This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme.

It is split into 2 parts: (1) an assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below.

Assessment

This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note - that is information in the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw - by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies:

-

a person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm

-

that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

-

that the security situation is such that there are substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm because there exists a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules

-

a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

Country of origin information

The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency, and traceability.

The structure and content of the country information section follows a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to this note.

All information included in the note was published or made publicly available on or before the ‘cut-off’ date(s) in the country information section. Any event taking place or report/article published after these date(s) is not included.

All information is publicly accessible or can be made publicly available. Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include:

-

the motivation, purpose, knowledge, and experience of the source

-

how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used

-

the currency and detail of information

-

whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources.

Multiple sourcing is used to ensure that the information is accurate and balanced, which is compared and contrasted where appropriate so that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture is provided of the issues relevant to this note at the time of publication.

The inclusion of a source is not, however, an endorsement of it or any view(s) expressed.

Each piece of information is referenced in a footnote. Full details of all sources cited and consulted in compiling the note are listed alphabetically in the bibliography.

Feedback

Our goal is to provide accurate, reliable and up-to-date COI and clear guidance. We welcome feedback on how to improve our products. If you would like to comment on this note, please email the Country Policy and Information Team.

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

The Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI) was set up in March 2009 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration to support him in reviewing the efficiency, effectiveness and consistency of approach of COI produced by the Home Office.

The IAGCI welcomes feedback on the Home Office’s COI material. It is not the function of the IAGCI to endorse any Home Office material, procedures or policy. The IAGCI may be contacted at:

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

5th Floor

Globe House

89 Eccleston Square

London, SW1V 1PN

Email: chiefinspector@icibi.gov.uk

Information about the IAGCI’s work and a list of the documents which have been reviewed by the IAGCI can be found on the Independent Chief Inspector’s pages of the gov.uk website.

Assessment

Section updated on 25 October 2022

1. Introduction

1.1 Basis of claim

1.1.1 Fear of persecution or serious harm by the state because of:

a. the treatment and/or conditions likely to be faced by the person during compulsory military service duties; or

b. the penalties likely to be faced by the person’s refusal to undertake, or their desertion from, military service duties; or

c. military service would involve acts, with which the person may be associated, which are contrary to the basic rules of human conduct

1.1.2 For guidance on military service generally, decision makers must see the Asylum Instruction on Military Service and Conscientious Objection for guidance on the general principles and relevant caselaw on considering claims based on evading or deserting from military service.

Official – sensitive: Start of section

1.2 The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: end of section

Official – sensitive: Start of section

2.

2.1 The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: end of section

2.2 Refugee convention reason

2.2.1 Simply evading / deserting from military service does not in itself give rise to a Refugee Convention ground.

2.2.2 Some persons may claim that refusing to do military service, including as a conscientious objector, will be perceived by the state as an act of political opposition.

2.2.3 The Asylum Instruction on Military Service and Conscientious Objection and paragraph 22 of the House of Lords judgement in the case of Sepet & Another v. SSHD [2003] UKHL 15 explain that it is necessary to carefully examine the reason for the persecution in the mind of the persecutor rather than the reason which the victim believes is why they are being persecuted.

2.2.4 The available country evidence indicates that Egyptian authorities would not consider evading or deserting military service an act of political opposition, unless done on political grounds. If a person is penalised on return, it is for the criminal offence of evading or deserting national service (see Authorities’ perception of evaders and conscientious objectors).

2.2.5 Persons who have deserted or evaded military service including as conscientious objectors do not form a particular social group (PSG) within the meaning of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention. This is because though they may share the experience of having deserted or avoided military service they do not have a distinct identity which is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

2.2.6 For further guidance on particular social groups, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.3 Exclusion

2.3.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

2.3.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

2.3.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: end of section

2.4 Risk of persecution / serious harm

a. Requirement to undertake national/military service

2.4.1 The law states that men aged between 18 and 30 are required to undertake military service in the armed forces (including military businesses), police or prison service. A 2010 amendment to The National Military Service Act stipulated only men over 18 could perform military service. In practice, most men doing their military service were over 20. There is no alternative to military service (see Alternatives to military service, General requirements and Age, recruitment, and length of service).

2.4.2 The following categories of men don’t have to undertake military service and are therefore not at real risk of persecution or serious harm for evading conscription:

a. men under the age of 18 or over the age of 30

b. men who have completed military service

c. students who are exempted

d. only son /sole breadwinner of deceased father or a father who is unable to earn a living

e. oldest son /brother of a citizen killed or injured in military operation

f. son of an officer, soldier, or volunteer who died or was injured in military operation

g. men with medical conditions

h. dual nationals

i. those who have already served in the army of a foreign state

j. repeat criminal offenders and those arrested as Islamists

k. students enrolled in colleges and military institutes who after graduation will become officers in the military, police and government departments

(See Age of recruitment and length of service and Exemptions)

2.4.3 A man who is required to undertake compulsory national/military service will generally not face treatment amounting to persecution or serious for not undertaking it (see Punishment for evaders below 30, Punishment for leaving the country to evade military service and Practical impact of evading military service). Each case must be considered on its own facts, with the onus on the man to demonstrate that he may face such a risk.

2.4.4 Most, but not all, men undergo some form of military service. Sources indicate, however, that a significant number of eligible men do not appear to undergo military service. The total male population aged 18 to 30 in 2021 was estimated to be more than 8 million, with anywhere between 957,941 and 1,596,559 turning 18 annually. During 2021 there were reportedly around 438,500 active armed forces of which anywhere between 200,000 and 320,000 were conscripts, a difference of up to over 1 million. Conscripts also constituted a considerable portion of the 300,000 Central Security Force (CSF) There is no information in the sources consulted on the number or proportion of conscripts in the police and prison services (see Size of the military).

2.4.5 Exemption from military service is possible based on age, family circumstances (only sons), medical conditions, and personal circumstances (those studying and certain categories of government workers). Exemptions can be both temporary and permanent. For example, students who are exempt from national service must complete it, but they might be able to defer it until they have finished their studies (see Exemptions and Study).

2.4.6 There is no exemption, however, for conscientious objection. While there have been a couple of reported cases of individuals who were conscientious objectors being exempted, these were without an official explanation of why they were exempted. There is no indication that the government has changed its general position on conscientious objection: that it is not a ground for an exemption (see Conscientious objection).

2.4.7 Some men may be excluded from military service. These include persons already serving officers in the armed forces, persons in certain professions, Islamists and repeat criminal offenders (see Exclusion from military service).

b. Treatment and conditions in military service

2.4.8 In general, conditions of military service are not so harsh as to amount to persecution or serious harm. However, each case will need to be considered on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they face such a risk.

2.4.9 Roles and conditions for conscripts in the Egyptian military vary. They range from serving in a military post to more quasi-civilian posts, such as guarding embassies or working in military or private run factories, offices, hotels, or companies (see Deployment and roles). Some skilled graduates are deployed to work for private companies (see Conscripts working in military-owned business).

2.4.10 Where a person is deployed, and therefore the conditions they work under, can be influenced by any ‘connections’ – family links which can used to influence those determining deployments – with individuals in authority. Conscripts who can afford to reportedly pay bribes might be assigned to units or locations they prefer (see Bribes (“rishwa”) and connections (“wasta”)).

2.4.11 Sources describe the pay of recruits as low and the work in the quasi-civilian posts as largely mundane. There are reports of recruits being exploited as cheap labour but there is no evidence in the sources consulted to indicate that recruits are systematically mistreated (see Pay).

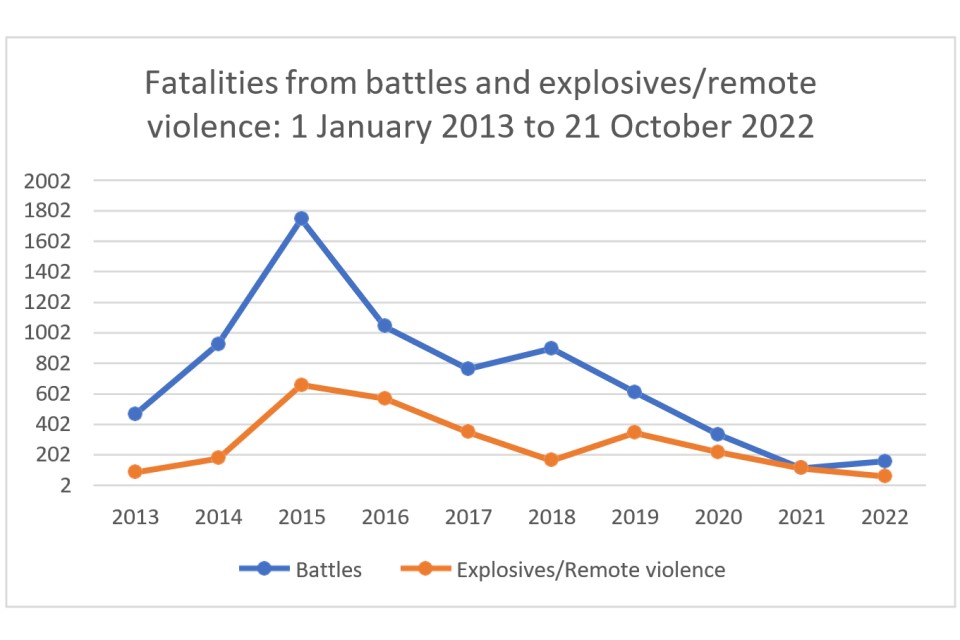

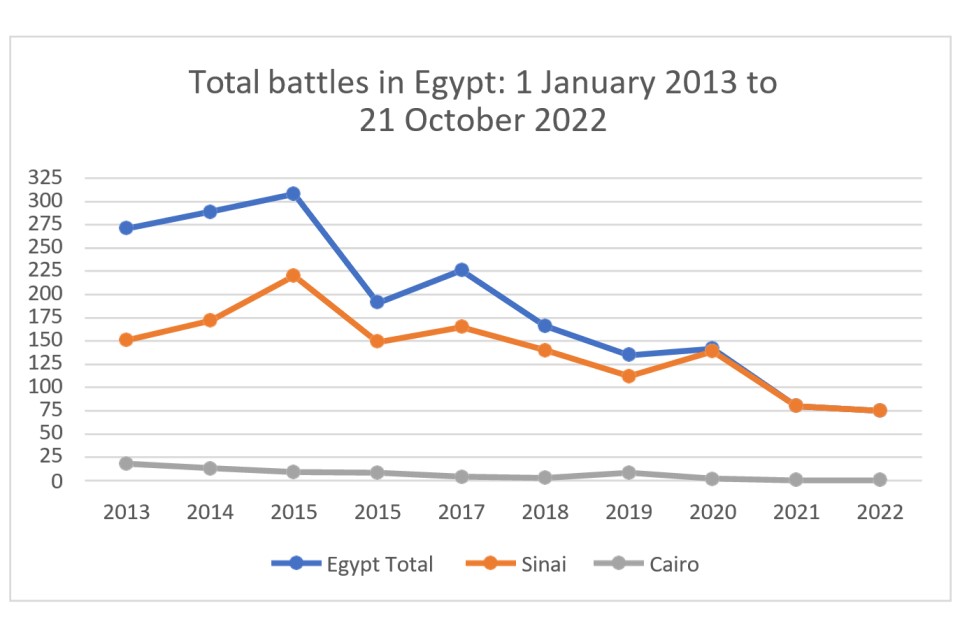

2.4.12 Simply fearing combat is not sufficient grounds to grant protection. Some conscripts may be posted to a place where they may be exposed to military combat or a risk of being exposed to security-related incidents, for example the Sinai region (see Combat roles). Sources indicated that conscripts are poorly trained and equipped leading to high number of casualties among the minority deployed to Sinai for combat and other roles (see Training and equipment). However, the number of attacks and resulting number of fatalities in Sinai have been declining since 2016. The Global Terrorism Database and Armed Conflict Location & Event Project data indicated that attacks decreased from 330 in 2016 to 45 in 2021 and fatalities, both civilian and military, also fell from 729 in 2017 to 69 in 2021 (see Combat roles).

2.4.13 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Asylum Instruction on Military Service and Conscientious Objection.

c. Penalties for draft evasion or desertion

2.4.14 In general, a person who deserts or evades military service or refuses to perform military service on the basis of conscientious objection is unlikely to be subject to a punishment that amounts to serious harm or persecution (see Punishment for evasion - overview and Punishment for desertion). A man who refuses to undergo military service for religious, moral or other convictions must demonstrate that any punishment he would face would be disproportionate as a direct result of their deeply held convictions. Each case must be considered on its facts, with the onus on the man to demonstrate that they face a risk of serious harm or persecution.

2.4.15 The penalty for draft evasion under the military Conscription Law 127 of 1980 depends on the situation and on the age of the person (see Punishment for evasion - overview)

2.4.16 If the draft evader is under 30 years of age and simply did not show up for the medical examination or did not submit documentation to confirm his military status upon turning 18, the penalty is an extra year of service (see Punishment for evaders below 30).

2.4.17 If the draft evader is 30 years or over and simply did not show up for the medical examination or did not submit documentation to confirm his military status the penalty up to 2 years imprisonment and/or a fine of 2,000 to 5,000 Egyptian pounds (EGP, approximately £90 – 224). In 2015 one source indicated that in most such cases there is a short hearing in a military court and impose a fine ranging from 2,200 to 2,300 EGP (approximately £99 -103) but not a prison sentence (see Punishment for evaders over 30).

2.4.18 A draft evader who submitted fraudulent documents to avoid conscription, could face 3 to 7 years imprisonment under article 50 of the Military Conscription Law (see Punishment for leaving the country to evade military service).

2.4.19 Leaving the country to avoid military service is punished under Article 54 of the Conscription Law which addresses all other violations and imposes a penalty of no less than 2 years in prison or a fine between 2,000 and 5,000 Egyptian pounds EGP approximately 90 – 224 GBP) or both. Leaving the country to avoid military service can also be punished under stricter provisions in the Penal Code for civilians if the Military Prosecutor seeks the assistance of the General Prosecutor. If a draft evader leaves Egypt, returns, and is asked to contact the conscription office, then leaves again without doing so, he is considered a repeat evader and faces up to 7 years in prison under Article 50 of the Military Conscription Law. In such cases, the Military Prosecutor may also seek the assistance of the General Prosecutor, and the evader may be classified as ‘wanted’ a ‘stricter’ penalty may be imposed in accordance with the Penal Code (see Punishment for leaving the country to evade military service).

2.4.20 Sources indicated that conscientious objection is criminalised in Egypt. One source stated that the military can use many laws within the penal code, Law 127 on Conscription, or Law 25 of 1966 on military courts to criminalize those opposing the military service (see Punishment for conscientious objectors).

2.4.21 The punishment for desertion has no limitation period and a man who deserts the battlefield can, in theory, be punished by death. However, if the crime of desertion is not committed on the battlefield it is punishable by prison sentence, or a lesser punishment (the relevant provisions do not provide the length of the prison sentence or amount of fine to be paid for desertion) (see Punishment for desertion).

2.4.22 Sources indicate that the penalties for draft evasion are usually enforced. However, there are no statistics in the sources consulted on the number of draft evaders / deserters imprisoned or fined, or length of detention for refusing to undertake military service in practice. Amnesty International reported that there are restrictions on civilians’ right to freedom of expression and access to information regarding military activities, and reporting on the military is criminalised (see Punishment for evasion - overview).

2.4.23 Detention conditions generally are poor due to widespread overcrowding, lack of adequate access to medical care, proper sanitation and ventilation, food, and potable water. The sources also indicate that some detainees, particularly members of opposition or government critics, may be subjected to human rights violations, including torture or other harm. Treatment and conditions are likely to vary according to the reasons why a person is detained, the facility they are detained in and their personal circumstances (see Practical impact of evading military service). Amongst the sources consulted (see Bibliography) none suggest that draft evaders or deserters were specifically targeted for ill treatment.

2.4.24 Persons who have not completed military service and not obtained an exemption may not be able to travel or migrate, obtain a passport, and may find it difficult to obtain employment or complete their studies (see Evasion and desertion in practice).

2.4.25 The punishment for draft evasion and desertion varies depending on the circumstances in which the man avoided military service. While exact data on the number and type of punishments are not clear, there is no indication that a man is likely to face a disproportionate punishment or held in conditions that are inhuman or degrading for draft evasion or desertion during peacetime which amounts to serious harm or persecution. However, deserting from a battlefield would potentially attract a death sentence (see Punishment for evasion - overview and Punishment for desertion).

d. Acts contrary to the basic rules of human conduct

2.4.26 In general, a conscript is not likely to be required to commit an act that is contrary to the basic rules of human conduct. However, whether or not a conscript is likely to be required to commit an act that is contrary to the basic rules of human conduct will need to be considered on a case by case with the onus on the claimant to demonstrate that are likely to be required to do so.

2.4.27 The Military Judiciary Act imposes the death penalty on members of the armed forces, including conscripts, for several offences involving the enemy, such as mistreating prisoners of war or those injured in battle, looting, loss, and vandalism, and abuse of power, implying that such acts are prohibited and illegal. The constitution and penal code also prohibit torture against detainees. However, Egyptian security forces, including the military, have been accused of human rights violations including torture and ill-treatment against detainees and of violating article 3 Common to the Geneva Convention and customary humanitarian law applicable to non-international armed conflict (see Abuses by security forces). Sources indicated that perpetrators of torture and other human rights violations almost universally enjoyed impunity (see Torture and other abuses).

2.4.28 Egyptian forces are engaged in fighting against Islamist insurgents in North Sinai. Some conscripts may be deployed in combat roles in North Sinai however the large majority will not (see Deployment and roles undertaking military service). In 2018, there 88 battalions with 42,000 soldiers stationed in Sinai Peninsula up from 41 battalions and 25,000 men the previous year. The World Factbook 2022 observed that there were thousands of soldiers, police officers, and other security professionals stationed in the Sinai, and tribal militias supported the security forces (see Conscripts and the Sinai).

2.4.29 Some sources claimed that security forces engaged in human rights violations including torture against detainees (see Abuses by security forces) and that security forces and affiliated militias engaged in counter-insurgency operations in Sinai carried out activities such as torture, enforced disappearances, and deliberate targeting of civilians which amounted to violations of humanitarian law. However, one source indicated that Egyptian armed forces had shifted their counterinsurgency strategy and tactics which reduced indiscriminate attacks and the targeting of civilians (see Violations of humanitarian law and article 3 common to the 1949 Geneva Conventions).

2.4.30 For guidance on Article 1F see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion: Article 1F of the Refugee Convention, and guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Asylum Instruction on Military Service and Conscientious Objection.

2.5 Protection

2.5.1 As the person’s fear is of persecution/serious harm at the hands of the state, they will not be able to avail themselves of the protection of the authorities.

2.5.2 For further general guidance on assessing the availability of state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.6 Internal relocation

2.6.1 As the person’s fear is of persecution/serious harm at the hands of the state, they will not be able to relocate to escape that risk.

2.6.2 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.7 Certification

2.7.1 A claim made by the following persons is likely to be certified as clearly unfounded:

-

Women (as they are not required to perform military service)

-

Men who are exempt or excluded from, or have completed, military service

-

Men over 30 years of age as they in practice cease to be eligible for military service

2.7.2 Where another claim based on a refusal to undertake military service is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

2.7.3 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

Section updated on 25 October 2022

3. Military

3.1 Size

3.1.1 The CIA World Factbook updated May 2022 (World Factbook 2022) noted:

‘Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF): Army (includes Republican Guard), Navy (includes Coast Guard), Air Force, Air Defense Command, Border Guard Forces; Interior Ministry: Public Security Sector Police, the Central Security Force, National Security Sector (2022)

‘[N]ote 1: the Public Security Sector Police are responsible for law enforcement nationwide; the Central Security Force protects infrastructure and is responsible for crowd control; the National Security Sector is responsible for internal security threats and counterterrorism along with other security services

‘[N]ote 2: in addition to its external defense duties, the EAF also has a mandate to assist police in protecting vital infrastructure during a state of emergency; military personnel were granted full arrest authority in 2011 but normally only use this authority during states of emergency and “periods of significant turmoil”.’[footnote 1].

3.1.2 USSD 2021 annual report on human rights in Egypt (USSD 2022) noted:

‘The Interior Ministry supervises law enforcement and internal security, including the Public Security Sector Police, the Central Security Force, the National Security Sector, and the Passports, Immigration, and Nationality Administration. The Public Security Sector Police are responsible for law enforcement nationwide. The Central Security Force protects infrastructure and is responsible for crowd control. The National Security Sector is responsible for internal security threats and counterterrorism along with other security services. The armed forces report to the minister of defense and are responsible for external defense, but they also have a mandate to assist police in protecting vital infrastructure during a state of emergency. On October 25, President Sisi announced he would not renew the state of emergency that expired on October 24 and had been in place almost continuously nationwide since 2017 after terrorist attacks on Coptic churches … Defense forces operate in North Sinai as part of a broader national counterterrorism operation with general detention authority … Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous abuses.[footnote 2]

3.1.3 The World Factbook 2022 estimated EAF size at 450,000 active personnel consisting of 325,000 Army, 18,000 Navy, 30,000 Air Force and 75,000 Air Defense Command[footnote 3]. The annual Global Firepower Index review which provides data concerning 142 modern military powers and ranks them based on their potential war-making capability in its 2022 report (GPF 2022) ranked Egypt 12th and further noted that Egypt had 450,000 active personnel, 300,000 paramilitary personnel and 480,000 reserves[footnote 4].

3.1.4 The Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index, ‘Egypt Country Report 2022’ (BTI 2022) in 2021, stated that the Egyptian military and security apparatus largely control the political sphere and had considerable power to shape policies and to place or remove individuals from office[footnote 5]. Freedom House, ‘Freedom in the world report 2022’ covering events in 2021 (FH 2022) similarly noted that ‘[s]ince the 2013 coup, the military and intelligence agencies dominate the political system, with most power and patronage flowing from Sisi and his domestic allies in the armed forces and security agencies … Most of Egypt’s provincial governors are former military or police commanders’[footnote 6]

3.2 Conscripts

3.2.1 An article published by the Washington-based media site Al-Monitor stated that ‘…[a] lack of transparency in Egypt’s state institutions makes it hard to obtain concrete figures on the number of conscripts enlisted each year, how many evade service and how many end up in prison.’[footnote 7]

3.2.2 The US Library of Congress study, ‘Egypt: a country study’ edited by Helen Chapin Metz (USLC, 1991) stated ‘[a]lthough 519,000 men reached the draft age of twenty each year, only about 80,000 of these men were conscripted to serve in the armed forces.’[footnote 8] The Conscience and Peace Tax International (CPTI 2021), an international peace movement whose aim is to obtain recognition of the right to conscientious objection to paying for armaments and war preparation and war conduct through taxes, noted in its submission on Egypt at the 134th Human Rights Committee that 957,941 males reached recruitment age annually[footnote 9]. According to GPF 2022 report, Egypt had a population of 106,4327,241 out of which 41.0% (43,639,269) was available for military service, 34.4% (36,614,411) was fit for service and 1.5% (1,596,559) reached military age annually.[footnote 10]

3.2.3 The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in a June 2019 report (DFAT 2019) assessed ‘that most (but by no means all) Egyptian males will undergo some form of national service.’[footnote 11]

3.2.4 Lifos, the Swedish Migration Agency’s expert institution for legal and country of origin information, report, ‘The state of the justice and security’, of September 2015 (Lifos 2015) noted that ‘[t]he CSF is the largest paramilitary group, with a force of 350,000 Individuals … The CSF recruits its personnel primarily from army conscripts with no former education.’[footnote 12] An article in the Egypt Independent, the English-language publication of Al-Masry Al-Youm daily, the country’s flagship independent paper based on interviews with former conscripts dated 11 November 2012 also noted that ‘[t]he CSF is composed of men called up for Egypt’s obligatory military service but who — usually because of a lack of educational qualifications or vocational skills — fail to make the cut for the army.’[footnote 13]

3.2.5 The Malcolm H Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center paper ‘The Egyptian military: A slumbering giant awakes’ by Robert Springborg, a retired professor of national security affairs and research fellow at the Italian Institute of International Affairs and F. C. ‘Pink’ Williams, retired major general and former US defense attaché in Cairo, of 28 February 2019 (Springborg and Williams 2019) noted that ‘of the total number of active duty and reserve personnel of some 850,000, poorly educated conscripts comprise the overwhelming majority.’[footnote 14] Similarly, the World Factbook 2022 observed that as of 2020, conscripts were estimated to comprise over half of the military and a considerable portion of the 300,000 CSF[footnote 15]. CPTI 2021 also noted that of Egypt’s 438,500 active armed forces 320,000 were conscripts[footnote 16].

Section updated on 25 October 2022

4. General requirements

4.1 Law

4.1.1 War Resisters’ International, a global pacifist and antimilitarist network with over 90 affiliated groups in 40 countries, noted, ‘[a]ccording to article 58 of the constitution of Egypt, “defence of the homeland and its territory is a sacred duty and conscription is compulsory, in accordance with the law”. Military service is regulated by the 1980 Military and National Service Act no. 127.’[footnote 17] [footnote 18] The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) report released in June 2019 (DFAT 2019) noted that ‘Military service is regulated by the Law on the Military and National Service (Law 127/1980).’[footnote 19]

4.1.2 Article 86 of the 2014 (rev. 2019) Egyptian Constitution, published by Constitute, an organisation which provides access to the world’s constitutions and translated by International IDEA [Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance] with updates by the Comparative Constitutions Project, stated, ‘[P]reservation of national security is a duty, and the commitment of all to uphold such is a national responsibility ensured by law. Defense of the nation and protecting its land is an honour and sacred duty. Military service is mandatory according to the law.’[footnote 20]

4.2 Age of recruitment and length of service

4.2.1 War Resister’s International noted that under the1980 Military and National Service Act no. 127 ‘… All men between 18 and 30 are liable for military service, which lasts for 3 years. Graduated students serve for a period of 18 months. After serving, conscripts belong to the reserves for 7 years.’[footnote 21]

4.2.2 The DFAT report 2019 stated, ‘[a]ll Egyptian males older than 18 are required to serve. Recruits face up to three years of mandatory service …’ [footnote 22]

4.2.3 Child Soldiers International, formerly the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers, which was incepted in 1998 by individuals from Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Save the Children, and other NGO actors to press the UN to adopt a treaty outlawing the recruitment and use of children, and which ceased to operate in June 2019[footnote 23], in its ‘Child Soldiers Global Report 2008 – Egypt’ (CSI 2008), noted that, ‘m]ajor constitutional amendments in March 2007 did not affect military service, which, in accordance with Article 58 of the constitution and Article 1 of the 1980 Military and National Service Act, remained compulsory for men aged between 18 and 30. Standard military service lasted three years; lesser terms were stipulated for those with certain types of education, such as higher education graduates.’[footnote 24]

4.2.4 The World Factbook last updated 4 May 2022 (World Factbook 2022) noted that voluntary enlistment is possible from age 16 for men and women and compulsory for men aged 18-30 years. The length of service is between 14 and 36 months followed by a 9-year reserve obligation. Active service length depends on education with high school dropouts serving the full 36 month while college graduates served for lesser periods of time, depending on their education[footnote 25].

4.2.5 The Egyptian representative informed the 1624th meeting, fifty-seventh session of the Committee for the Rights of the Child (CRC) on the question of Egypt’s the implementation of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict’ that, ‘National Military Service Act, amended in 2010, stipulated that only persons over 18 could perform their military service. In practice, most persons doing their military service were over 20 …’[footnote 26] CPIT did not find other independent sources to corroborate this claim in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

4.2.6 However, a call up for new conscripts for April 2021 appear to have targeted those at least 19 years old. The Armed Forces News of 15 December 2020 reported:

‘General Mohamed Zaki, the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, Minister of Defense and Military Production, approved the acceptance a new batch of recruits for April 2021. The new recruits shall be received on the 26th DEC 2020, and according to the following conditions:

‘First, Postgraduates:

-

Born in the period from 1st January till 30th June, of all years up to the year 2000.

-

Graduates of all government and private colleges and higher institutes who obtained their academic qualifications and approved their results during the period from 1st October 2020 till January 2021.

-

Graduates of faculties of medicine … who completed the internship year and their training period from the 1st of October 2020 till January 2021. As well, who were born between 1st, January and 30th, June of the year 2001, also, Graduates that did not apply for conscription the past years.

‘… Second: Upper-Intermediate Degree Holders:

- Born in the period from 1st January till 30th June, of all years up to the year 2000 who obtained their upper-intermediate degree during the period from 1st October 2020 till January 2021. As well, those who were born in the period from 1st January till 30th June, of all years up to the year 2001, who obtained their upper-intermediate degree during the period from 1st February 2020 till the end of January 2021. In addition to those who did not apply for conscription the past years.

‘… Third: Intermediate Degree Holders:

- Born in (April- May - June) of 2001 who obtained their intermediate degree during the 2019-2020 educational year. In addition to those who were born in (April- May - June) of 2000 or earlier who obtained their intermediate degree during the 2019-2020 educational year. Who did not apply for conscription the past years,

‘… Fourth: No Educational Degrees:

-

Born in (April – May – June) of 2001.

-

Those who did not apply for conscription the past years.’[footnote 27]

4.3 Procedures for drafting conscription

4.3.1 USLC 1991 observed:

‘The government required all males to register for the draft when they reached age sixteen. The government delineated several administrative zones for conscription purposes. Each zone had a council of military officers, civil officials, and medical officers who selected draftees. Local mayors and village leaders also participated in the selection process. After the council granted exemptions and deferments, it chose conscripts by lot from the roster of remaining names. Individuals eligible to be inducted were on call for three years. After that period, they could no longer be drafted.’[footnote 28]

4.3.2 The Armed Forces News (AFN) of 15 December 2020 reported that new conscripts for April 2021 should go to the conscription and mobilization offices to register and then go to conduct a medical check in the conscription and mobilization areas. The new conscripts were required to take the following document: national ID, military and national service card (Form#6), original copy of the birth certificate or an official copy, an approved criminal sheet issued from the police station of residence, fingerprints (Form#1) issued from the conscription representative of the police station of residence (applies only for no educational degrees recruits), blood type, original copy of the educational degree, internship-training certificate for doctors, marriage certificate (if applicable), driver’s license (if applicable), original dismissal letters for those who have been dismissed that specifies the date and reason of the dismissal decision (if applicable), and the appointment decision and letter for teaching assistants, teachers, or resident doctors (if applicable) [footnote 29].

4.3.1 In email correspondence with CPIT on 22 July 2022 a senior Middle East and North Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch observed:

‘The process to be drafted is very well structured and it has several phases. Normally, as a university graduate you go after your graduation to finalize some paperwork with the police station then there’s a day when you go to a military base to hear whether you’re exempted or drafted and for how long. If you’re drafted there’s a scheduled day when hundreds or thousands of soldiers-to-be go to the military base in Zayton East Cairo to be medically examined and then the same day or maybe some other day you see a few senior officers (Kash al-Hay’a) who ask you a few questions. During this process people are also handed forms they have to fill that ask about your background including questions like: Have you been politically active? Have you been convicted before? Do you have any weird beliefs (like being atheist)? do you have any relatives who are foreigners or dual nationals? … etc. The medical examination also includes the infamous anal examination perceived to identify gay people. When they find out someone is gay, they get exempted on security grounds too.’[footnote 30]

Section updated on 25 October 2022

5. Exemptions

5.1 Overview

5.1.1 USLC1991 noted, ‘although it was no longer possible for a prospective conscript to pay a fee in lieu of service, he could still apply for an exemption.’[footnote 31] The DFAT 2019 report observed that ‘exemptions and deferrals are common’ and these dependent on personal and family circumstances[footnote 32].

5.1.2 The Immigration and Refugee Bureau of Canada response to information request dated 25 October 2021 (IRB RIR October 2021), noted that Egypt’s Ministry of Defence is responsible for issuing military service records:

‘… Military documents indicating military service status, whether it is completion, exemption, exclusion, or payment of a penalty for absence, can be obtained in person at an Egyptian embassy or within Egypt at the local authority’s office, and through a proxy or family member of the first degree located in Egypt, should the applicant reside abroad and the nearest embassy or consulate is not able to provide the required services; however, “it is unlikely that in practice that would be accepted because the authority in Egypt will likely rule that the applicant can present themselves at an embassy or consulate abroad that does provide these services”… military service documents cannot be obtained through a proxy at an embassy…’[footnote 33]

5.1.3 Ahram Online, an English language news website, reported on 27 December 2018 the launch of an online portal by the ministry of defence for conscription services where Egyptian males can apply for travel authorization and exemption certificates[footnote 34].

5.2 Age

5.2.1 A Middle East Eye (MEE), a London-based online news outlet covering events in the Middle East and North Africa, article from 21 October 2016 noted that under the Law on the Military and National Service (Law 127/1980) all Egyptian men between 18 and 30 years of age are obligated to undertake military service. However, men are no longer required to enlist in the military once they reach the age of 30[footnote 35]. The IRB RIR dated 17 August 2018 (IRB August 2018), based on a range of sources observed that many young Egyptians leave the country and then come back after they reach the age of 30, which is the cut off for conscription[footnote 36]. According to the DFAT 2019 report men are permanently exempt once they turn 30 [footnote 37].

5.2.2 On 4 November 2012, the online newspaper, The Daily News, reported:

‘Four groups of military personnel representing the Ministry of Defence and Military Production departed overseas on Sunday to contact Egyptians living abroad with regards to fulfilment of their mandatory military service. The groups will travel to Europe, America, the Gulf, and other Arab states for two weeks …

‘The purpose [of the visit] … is to locate young Egyptians living abroad who have not completed their mandatory military service and try to settle their status regarding military service. Those over 30 will be considered to have defaulted on their service and will be fined ….’[footnote 38]

5.2.3 In an article on 1 November 2012, Khaleej Times, a UAE English language daily newspaper, reported that Egyptian youth in the UAE who fail to appear for the mandatory military service can approach the Embassy of Egypt in Abu Dhabi from November 16 to 20 to amend their position and pay the set fine. The report quoted Col Mahmud Saad, Military Attaché of Egypt in Abu Dhabi who said, ‘“[a]ll those above 30 years in age are eligible to apply. Instead of travelling to Egypt, they can appear before the military judicial commission in the Egyptian embassy, pay the set fine of Dh 2,163 [equivalent 511 GBP[footnote 39]] and amend their military position and be released …”’[footnote 40]

5.2.1 A news article on Ahram Online dated December 2017 stated, ‘Egyptian Armed Forces committee decided that men from the southern Halayeb, Shalateen, Abu Ramad and Wadi Al-Allaqi areas, who passed the age of 30 without performing mandatory military service, will be issued ‘final certificates of exemption for military service as part of the efforts by the Armed Forces to assist citizens of these border areas.’[footnote 41]

5.2.2 In 2018 the Armed Forces News (AFN), Egypt’s Ministry of Defense web portal, reported that the Minister of Defense and Military Production, had approved the travel of 11 military judicial committees to US, Italy, Kuwait, Germany, Saudi Arabia, England, Greece, France, UAE, Jordan and Bahrain to resolve the conscription statuses of the Egyptian youths abroad, and to issue certificates to terminate the conscription statuses of those who failed to perform military service and are over 30 years of age, and subject to a fine prescribed by law.’[footnote 42]

5.2.3 The Egyptian Embassy in Washington website stated:

‘… Temporary settlement of the conscription position of the case of failure to perform military service and exceeding the age of 30 (the age of abstention from conscription):

‘The conscription position can be temporarily settled by paying the penalty for failure to perform military service to the Defense Office in Washington ($ 588) and the citizen is issued a letter approving the issuance of a passport with full validity (7 years) for only two consecutive times, after which the final position of the conscription must be settled.’[footnote 43]

5.3 Medical

5.3.1 The European Asylum Support Office (EASO), an agency of the European Union set up by Regulation (EU) 439/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council to among other things provide country of origin information (COI) on key countries, relevant for the asylum decision‑makers in the field of asylum [footnote 44] which was re-established as the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA)[footnote 45] in a query response dated 9 October 2015 (EASO October 2015) cited the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees which noted that ‘[u]nder the National Military Service Act, anyone medically unfit for military service is permanently exempt.’[footnote 46] The same source cited Landinfo, the Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, which noted that medical reasons are among the legal grounds for final exemption from military service on the Egyptian Directorate of Conscription and Mobilisation’s website. However, there was no specific information on which illnesses are deemed sufficient to grant final exemption nor on the documentation required[footnote 47].

5.3.2 The website of the Egyptian Consulate General in Montreal also stated that Egyptian men can be exempted from military service on medical grounds, and conscripts can be permanently exempted from military service if they are medically unfit. This information was cited in the IRB RIR dated 20 July 20, 2018 (IRB July 2028)[footnote 48]. DFAT 2019 also noted that exemptions are possible for health reasons[footnote 49]. Sources indicated that medical examination was one of the stages for conscription.[footnote 50]

5.3.3 The EASO COI query -Egypt of 30 April 2018 observed, ‘[a] United Nations report dated 17 March 2010 enumerates the various grounds for exemption: … Under the National Military Service Act, anyone medically unfit for military service is permanently exempt …’[footnote 51]

5.4 Family circumstances

5.4.1 USLC 1991 noted, ‘an only remaining son whose brothers died in service … and family breadwinners were all eligible for exemptions.’[footnote 52]

5.4.2 According to the Egyptian Ministry of Defence’s website, as cited in the IRB July 2018 response, a conscript can be temporarily exempted from military service if he is:

-

the only son of his living father

-

the sole supporter of his father who is unable to earn a living, as well as his brothers who are also unable to earn a living

-

the sole supporter of his widowed or [translation] “irrevocably divorced” mother, or if the latter’s husband is unable to earn a living.[footnote 53]

5.4.3 The same report noted that a conscript can be permanently exempted of military service if he is:

-

the only son of his deceased father or of a father who is unable to earn a living;

-

eligible for recruitment, but is the oldest son or brother of a citizen killed or injured in military operation and then unable to earn a living;

-

eligible for recruitment, but is the brother or son of an officer, soldier, or volunteer who died or was injured in military operation;

-

is permanently unable to earn a living;

-

30 years old or older and is entitled to temporary exemption[footnote 54].

5.4.4 Likewise, DFAT 2019 observed:

‘Exemptions… can occur for family reasons, including: when an individual is an only son, is the only breadwinner, has brothers who have migrated and is supporting the family, has a brother already serving in the military, or has a father or brother who died while serving in the military. Other family reasons may also be considered. This exemption is renewed every three years for reassessment of the situation until the subject is 30 years old, at which time he receives a permanent exemption.’[footnote 55]

5.5 Students

5.5.1 DFAT 2019 observed that ‘university students can be granted exemptions up to the age of 28 …’[footnote 56] The Egyptian Consulate in London website also stated that students can apply for military exemption[footnote 57].

5.5.2 The IRB reported in July 2018 stated:

‘The Ministry of Defense of Egypt states on its website that, in peace time, students can postpone their military service until they obtain their academic degree for which the postponement was granted … The same source defines “students” as follows: [translation] Secondary school students or equivalent in the Republic up to the age of (22) years. Students up to the age of (25) years who are enrolled in colleges and will obtain a two-year college degree. Students up to the age of (28) years who are enrolled in the universities, faculties, and colleges of the Arab Republic of Egypt and equivalent in the Republic. Students studying abroad at different stages of education. … If a student - not over the age of 29 years - exceeds in the final year of study the maximum conscription deferrals referred to, the deferral shall continue until the end of the academic year of colleges and faculties.[footnote 58]

5.5.3 Similarly, a MEE article of 28 November 2016 observed that postponement of military service is possible for students for the duration of their studies[footnote 59].

5.6 Dual nationals

5.6.1 The Consulate General of the Arab Republic of Egypt in the UK website stated that dual nationals can apply for exemption from military service[footnote 60]. The Egyptian Embassy in Washington D.C also noted that dual nationals including those who have acquired Egyptian nationality from the mother and those who have acquired foreign nationality can apply for exclusion from the performance of military service.[footnote 61] The MEE report of 28 November 2016 also stated that a ground for exemption is if the person ‘has dual nationality.’[footnote 62]

5.7 Excess number of conscripts

5.7.1 The DFAT 2019 report stated, ‘the military may exempt individuals if it has an excess number of conscripts.’[footnote 63]

5.7.2 There current sources consulted ( see Bibliography) did not have information on what happened to conscripts who are exempted due to excess numbers. Nonetheless, USLC 1991 noted that ‘… [a]fter the council granted exemptions and deferments, it chose conscripts by lot from the roster of remaining names. Individuals eligible to be inducted were on call for three years. After that period, they could no longer be drafted.’ [footnote 64]

5.8 Certain professions

5.8.1 A 2017 report on Egypt’s military by GlobalSecurity.org noted that ‘men employed in permanent government positions, … [and] men employed in essential industries … were all eligible for exemptions.’[footnote 65] The same information is provided by USLC1991 which noted, ‘[m]en employed in permanent government positions … [and] men employed in essential industries … were all eligible for exemptions.’[footnote 66]

5.8.2 IRB July 2018 noted, ‘[o]n its website, the Egyptian Ministry of Defense lists four cases of exclusion from military services: [translation] … Individuals appointed to the rank of Lieutenant in the Armed Forces or in a government body with a military system …’[footnote 67]

5.9 Conscientious objection

5.9.1 UNHCR ‘Guidelines on international protection no 10: Claims to Refugee Status related to Military Service within the context of Article 1A (2) of the 1951 Convention and/or the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees of 12 November 2014 (UNHCR 2014) stated:

‘Conscientious objection to military service refers to an objection to such service which “derives from principles and reasons of conscience, including profound convictions, arising from religious, moral, ethical, humanitarian or similar motives.” Such an objection is not confined to absolute conscientious objectors [pacifists], that is, those who object to all use of armed force or participation in all wars. It also encompasses those who believe that “the use of force is justified in some circumstances but not in others, and that therefore it is necessary to object in those other cases” [partial or selective objection to military service]. A conscientious objection may develop over time, and thus volunteers may at some stage also raise claims based on conscientious objection, whether absolute or partial.’[footnote 68]

5.9.2 The UN Human Rights Commission publication , ‘Conscientious objection to military service’ dated 2012 stated:

‘… In official reports to the Commission, a number of States regularly reported their objections to its resolutions on conscientious objection. For example, in a joint letter to the Commission on Human Rights dated 24 April 2002, 16 Member States [including Egypt] stated that they did “not recognize the universal applicability of conscientious objection to military service”.[footnote 69]

5.9.3 The ‘Report of the Secretary-General prepared pursuant to Commission resolution 1995/83 to the Commission’ to the Commission on Human Rights fifty-third session on the question of conscientious objection to military 16 January 1997 also noted that Egypt does not recognise conscientious objection.[footnote 70] The Conscience and Peace Tax International (CPTI) noted in its Submission to the Human Rights Committee: 134th session on Egypt regarding of Military service, conscientious objection and related issues stated, without explaining the source of its information, that ‘there is no legal provision for conscientious objection and no alternative service.’[footnote 71]

5.9.4 The IRB August 2018 report quoted representatives of European Bureau for Conscientious Objection (EBCO) and War Resisters’ International (WRI) who indicated that ‘Egypt does not have legislation regulating conscientious objection to military service.’[footnote 72] A Human Rights Watch (HRW)researcher cited by the IRB stated ‘“[n]o respect or protection is granted for any objector”.’[footnote 73]

5.9.5 The 2019 DFAT report observed:

‘Conscientious objection to military service is not a common phenomenon in Egypt. However, there is a small conscientious objector movement, launched by prominent conscientious objector, Maikel Nabil, who refused to be enlisted in 2009. Nabil was detained five times for publicly campaigning against compulsory military service and was imprisoned for two years for insulting the military. In June 2015, two conscientious objectors (including Nabil’s brother) were granted an exemption from service by the office of the defence minister. The exemption did not state a reason or recognise the two as conscientious objectors. It is unlikely that these exemptions represent any formal move towards recognition of conscientious objection.’[footnote 74](See Punishment for evasion and Punishment of conscientious objectors).

5.9.1 The MEE report of 28 November 2016 noted that conscientious objectors can wait months, if not years, for the army’s decision on their exemption, and that objectors are regularly summoned by the army and subjected to interrogations. According to the 2016 report, only 9 young men in Egypt are known to have refused mandatory military service in the last few years[footnote 75].

5.10 Exclusion from military service

5.10.1 According to the Egyptian Ministry of Defence website, as cited in the IRB August 2018, there are 4 grounds for exclusion from military service:

-

individuals appointed to the rank of lieutenant in the Armed Forces or in a government body with a military system

-

those who have already served in the army of a foreign state and have established normal residence

-

students enrolled in colleges and military institutes where after graduation they will become officers in the Armed Forces, police, and government departments

-

excluded individuals according to rules and terms issued by the Minister of Defence such as people who acquired a foreign nationality or repeat (criminal) offenders[footnote 76].

5.10.2 The EASO COI report of 30 April 2018 and the DFAT 2019 report also stated that those arrested as Islamists will not be recruited as conscripts[footnote 77] [footnote 78]. USLC 1991 defined Islamists ‘as politically organized Muslims who seek to purge the country of its secular policies …’[footnote 79]

5.11 Alternatives to military service

5.11.1 War Resisters’ International, citing other sources, last updated in 1998 stated, ‘“[t]here is… no substitute service”’[footnote 80]. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) report, ‘Views adopted by the Committee under article 5(4) of the Optional Protocol, concerning communication No 5(4) (CCPR/C/122/D/2015) dated 28 June 2018 noted that ‘… in Egypt there is no alternatives to compulsory military service.’[footnote 81]

Section updated on 25 October 2022

6. Deployment and roles

6.1 Policing roles

6.1.1 Various sources noted that conscripts may be required to serve either in the police force or the prison-guard service.[footnote 82] [footnote 83] [footnote 84]

6.1.2 Lifos 2015 noted that CSF’s primary responsibility is to protect infrastructure as well as key domestic and international officials. It also assists the National Police with capabilities such as traffic management and public order maintenance, such as riot control.[footnote 85] AL- Monitor also noted in its 22 July 2015 report that some conscripts are dispatched to police urban centres[footnote 86].

6.1.3 Lifos (2015) observed:

‘General working conditions remain difficult within the police force. Long working hours, up to 12 hours per shift, is not uncommon. Wages remain low, despite the 300 percent salary raise issued by the Morsi regime in 2013 … Bribes – Rashwa - and other additional sources of income are, therefore, not uncommon.

With regard to the conscript soldiers within the CSF, the situation is the same, if not worse. Living conditions at the camps are both bleak and meagre. Soldiers are repeatedly subjected to humiliation and abuse by their superiors. Reportedly, soldiers are beaten and mistreated by officers. Soldiers who complain risk being charged with insubordination. Their missions outside often involve risk for violence, as when engaging in riot control; however, there is also boredom from standing in one place for hours on end.’[footnote 87]

6.1.4 The Egypt Independent in an article dated 11 November 2012 noted, ‘[o]f all army conscripts, CSF soldiers are drawn from the most disadvantaged social backgrounds. With no recourse to justice, they endure incessant humiliation and abuse in already bleak living conditions, as well as the risk of violence — and boredom — during missions outside camps that often involve standing in one place for hours on end.’[footnote 88]

6.2 Combat roles

6.2.1 Since 2011, Egypt has been actively engaged in counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism operations in the North Sinai governorate against several militant groups, particularly the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham – Sinai Province (IS-SP).[footnote 89] [footnote 90] [footnote 91]

6.2.1 DFAT 2019 noted that ‘some conscripts have been sent to the military front lines in North Sinai.’[footnote 92]The Times of Israel, an English-language online newspaper, in an article dated 1 March 2018 cited Egypt’s military chief of staff who indicated that 88 battalions with 42,000 soldiers were stationed in Sinai Peninsula up from 41 battalions and 25,000 men the previous year[footnote 93]. The World Factbook 2022 observed that there were thousands of soldiers, police officers, and other security professionals stationed in the Sinai, and tribal militias supported the security forces[footnote 94].

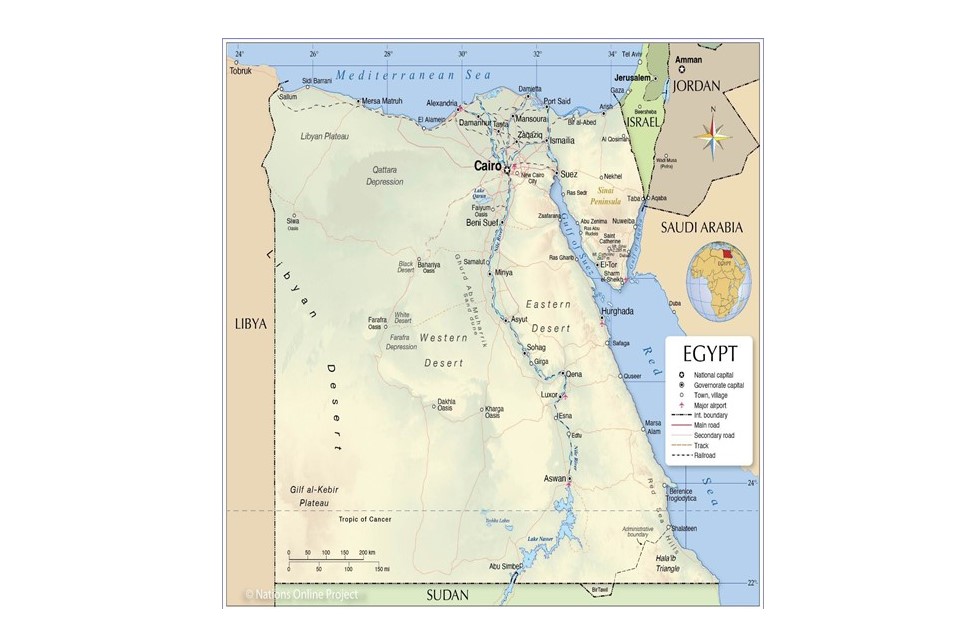

6.2.2 ‘Political map of Egypt; the map ‘shows Egypt and surrounding countries with international borders, the national capital Cairo, governorate capitals, major cities, main roads, railroads, and major airports.’[footnote 95]

Image from Nations Online Project

6.2.3 The paper ‘The Egyptian Military’s Terrorism Containment Campaign in North Sinai’, in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, by Allison McManus, senior fellow at the Center for Global Policy, a US think tank, dated 30 June 2020 (McManus 2020) observed:

‘The current strategy [containment strategy] has largely been successful in mitigating the threat from its peak in 2015 and has more or less kept the threat isolated to North Sinai. Militants’ capacity to conduct large scale assaults has clearly been degraded since their brief July 2015 success in overtaking the city center of Sheikh Zuweid; the EAF, according to official statements, claimed to have killed around a hundred fighters affiliated with the self-proclaimed Islamic State in ensuing clashes and airstrikes. Today, militant attacks have abated overall in Egypt: while 2015 and 2016 saw sustained political violence throughout the country, with intermittent sectarian or civilian-targeted attacks, only a few have been reported outside of North Sinai since January 2018.’[footnote 96]

6.2.4 Levy 2021, an associate research fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a US think tank whose mission is to advance a balanced and realistic understanding of American interests in the Middle East and to promote the policies that secure them, (Levy 2021) observed based on data from the Global Terrorism Database and Armed Conflict Location & Event Project (ACLED), that attacks in Sinai had decreased from 330 in 2016 to 43 in 2018 before rising to 169 in 2020 and then falling to 45 as of October 2021. Fatalities, both civilian and military, also fell from 729 in 2017 to 69 in 2021.[footnote 97]

6.2.5 Similarly, the US Congress Research Service in report ‘Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations’ by Jeremy M Sharp dated 13 July 2022 (Sharp 2022) noted that ‘Egyptian counterterrorism efforts in Sinai appear to have reduced the frequency of terrorist attacks.’ The report cited former Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker wrote in June 2022 that ‘“The Egyptian military finally appears to be making progress in rolling back the group. Not only have there been fewer attacks, but Cairo’s funnelling of economic development funds to the peninsula has also generated some goodwill among the long-restive population.”’ [footnote 98].

6.2.6 However, the sources indicated that IS-IP remained a threat and continued to stage attacks albeit in a small scale. Levy 2021 noted that ‘[s]maller-scale assaults were still occurring as late as July 2020, when the group [Wilayat Sinai] occupied four villages. Displaced residents were unable to return until the military dislodged the jihadists that October.’[footnote 99] Similarly Sharp 2022 noted, ‘[t]hough the pace of IS-SP attacks have dropped, other experts believe that IS-SP remains a significant security threat, especially when pitted against poorly trained Egyptian conscript soldiers serving in the Sinai.’ The reported noted that in May 2022, IS-SP launched two separate attacks against Egyptian forces killing 16 people.[footnote 100]

6.2.7 The graph below shows number of fatalities from battles and explosives /remote violence in the whole of Egypt and Sinai (latest date is 12 August 2022). Data from ACLED dashboard[footnote 101].

6.2.8 Graph below shows number of battles in Egypt and Sinai based on data from ACLED dashboard. [footnote 102]

6.3 Training and equipment

6.3.1 Al-Monitor report of 22 July 2015 observed, ‘[e]ach year, Egypt enlists hundreds of thousands of young men to serve in the military, but critics say they are not trained well …’[footnote 103] Springborg and Williams 2019 stated ‘[c]onscripts continue to be treated as cannon fodder — as indicated by their relatively high casualty rate in the Sinai.’[footnote 104] MEE reported on 1 February 2019 ‘while IS militants are trained in guerrilla and desert warfare and house-to-house combat, with possible military experience in Gaza, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, the bulk of Egypt’s fighting forces are conscripts who have spent only 45 days in boot camp to learn how to be soldiers.’ [footnote 105] The MEE article quoted a special forces police officer who stated, ‘the 45-day boot camp for conscripts, paired with a lack of sufficient equipment, had left many of the young men serving in the peninsula more of a liability than an effective fighting force.’ [footnote 106]

6.3.1 The article ‘Egypt’s armed forces today: A comparison with Israel’ in Middle East Center for reporting and Analysis (MECRA) which stated on its website that it aims to bridge the gap between field reporting and analysis in the region through working with policymakers, scholars, local experts and journalists, by David Mitty, a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel and Foreign Area Officer and an adjunct professor at Norwich University’s Online Security Studies Program, (Mitty 2020) noted that ‘[c]onscripts receive only 45 days of training, are mistreated by officers, and are ill-trained infantrymen at best.’[footnote 107]

6.4 Pay

6.4.1 A July 2015 news article by Al-Monitor noted that conscripts receive a nominal wage of 250 Egyptian pounds ($35) a month [approximately £30[footnote 108]] a month[footnote 109]. TI 2018 stated that the conscripts remarkably low monthly salaries were raised to between $34 and $35 in 2013 [£29 and £30[footnote 110]][footnote 111]. The DFAT 2019 report also noted that recruit earned a nominal monthly wage of EGP250 (AUD37) [approximately £30].[footnote 112]

6.4.2 Yezid Sayigh, a senior fellow at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, noted in ‘Owners of the Republic: An Anatomy of Egypt’s Military Economy’ dated 2019 (Sayigh 2019) also noted that ‘[a]ctive, reserve, retired, and honorary EAF personnel as well as conscripts and civilian employees of the defense sector may use discount vouchers to buy domestically produced and imported goods—the latter already subsidized by virtue of being exempt from customs duties.’[footnote 113]

6.5 Conscripts working in military-owned business

6.5.1 According to World Factbook 2022, ‘the military has a large stake in the civilian economy, including running banks, businesses, and shipping lines, producing consumer and industrial goods, importing commodities, and building and managing infrastructure projects, such as bridges, roads, hospitals, and housing.’[footnote 114]

6.5.2 The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) report ‘The Generals’ Secret: Egypt’s Ambivalent Market’ of February 2012 by Zeinab Abul-Magd, an associate Professor of Middle Eastern History at Oberlin College, observed that ‘[t]here are three major military bodies engaged in civil production: the Ministry of Military Production, the Arab Organization for Industrialization, and the National Service Products Organization …’[footnote 115]

6.5.3 USLC 1991 noted, conscripts may be required to serve in one of the military economic service units[footnote 116]. AL- Monitor noted in its 22 July 2015 report that [t]he more fortunate [conscripts] can pull strings to find shelter amid the relative safety of the military’s pasta factories and petrol stations.’[footnote 117]

6.5.4 Transparency International report, ‘The Officer’s Republic: The Egyptian Military and Abuse of Power’ dated March 2018 (TI 2018) observed:

‘An exemption from the ban of forced labour has enabled the military to continue to use conscript labour in the service of military-owned business … The practice started in the 1980s and largely involved unskilled conscripts working in agriculture and food production. It has however expanded and become more sophisticated …

‘Since the expansion of military business into large industries, draftees who hold higher technical degrees have been similarly used in factories, hotels, gas stations, hospitals, trading companies and more …’[footnote 118]

6.5.5 Sayigh 2019 noted:

‘EAF conscripts are used as cheap labor in virtually all sectors of the military economy. The practice started in 1986 when then minister of defense … announced that 30,000 conscripts would be organized into so-called development battalions to contribute to the national economy. Over thirty years later, these battalions (now known as civilian construction brigades) are still employed to implement publicly funded projects, especially in construction, agriculture, and land reclamation, whether undertaken by public or private contractors. MOD [Ministry of Defense], MOMP [Ministry of Military Production], and AOI [Arab Organization for Industrialization] companies also employ conscripts who are in their final six months of service, and sometimes for considerably longer, and interviews confirm that skilled conscripts are routinely loaned to private sector companies.’[footnote 119]

6.5.6 Sayigh 2019 further noted that:’ [b]y January 2015 [NSPO] claimed 20,000 employees, of whom 5,000 were from the EAF according to [the] company director general, … although another source claimed it employed 7,500 EAF enlisted personnel and conscripts.’ [footnote 120]

6.5.7 FH 2022 also noted that ‘[m]ilitary conscripts are exploited as cheap labor to work on military - or state-affiliated development projects.’[footnote 121]

6.6 Bribes (‘rishwa’) and connections (‘wasta’)

6.6.1 Defence Post, an independent security and defense news publication, noted in a report dated April 2018 that ‘in service Egyptian conscripts are often forced to bribe superiors to avoid mistreatment or to pay extra for rations and certain equipment.’[footnote 122] DFAT 2019 also noted that ‘individuals with significant connections are likely to have an easier experience than those without them.’[footnote 123]

6.6.2 On the same issue Sayigh 2019 noted:

‘Major General Michael Collings, who served as senior U.S. defense representative and chief of the Office of Military Cooperation in Cairo from 2006 to 2008, later told the New York Times that corruption was endemic in the senior EAF officer corps … The pattern extends all the way down the chain of command: conscripts who can afford to reportedly pay bribes to be assigned to units or locations they prefer—up to EP15,000 [approximately £668[footnote 124]]in 2015 (then $2,000).’[footnote 125]

6.6.3 David M Witty, a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel, Foreign Area Officer with experience in the Middle East, currently with North Carolina’s Advanced Computer Learning Company (ACLC) and adjunct professor at Norwich University’s Online Security Studies Program’ observed in ‘Egypt’s armed forces today: A comparison with Israel’ of September 2020 that ‘conscription methods are flawed, corrupt, and involve the exploitation of personal connections and bribes to avoid tough assignments. Conscription by the enlisted ranks is viewed as “unfortunate,” and university graduates do everything possible to avoid it’.[footnote 126]

Section updated on 25 October 2022

7. Evasion and desertion of military service

7.1 Overview

7.1.1 UNHCR, ‘Guidelines on international protection No. 10’ of 12 November 2014 stated:

‘Draft evasion occurs when a person does not register for, or does not respond to, a call up or recruitment for compulsory military service. The evasive action may be as a result of the evader fleeing abroad, or may involve, inter alia, returning call up papers to the military authorities. In the latter case, the person may sometimes be described as a draft resister rather than a draft evader… Draft evasion may also be pre-emptive in the sense that action may be taken in anticipation of the actual demand to register or report for duty. Draft evasion only arises where there is mandatory enrolment in military service [“the draft”]. Draft evasion may be for reasons of conscience or for other reasons.’[footnote 127]

7.1.2 Regarding desertion, the UNHCR, ‘Guidelines on international protection No. 10’ stated:

‘The Desertion involves abandoning one’s duty or post without permission or resisting the call up for military duties. Depending on national laws, even someone of draft age who has completed his or her national service and has been demobilized but is still regarded as being subject to national service, may be regarded as a deserter under certain circumstances. Desertion can occur in relation to the police force, gendarmerie or equivalent security services, and is also the term used to apply to deserters from non-State armed groups. Desertion may be for reasons of conscience or for other reasons.’ [footnote 128]

7.2 Authorities’ perception of evaders and conscientious objectors

7.2.1 The IRB August 2018 report quoted a representative of The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights (EOHR) and Jean Jaurès, a lecturer in public law at the University of Toulouse, who noted that, ‘Egyptian authorities do not consider evading military service or being a conscientious objector a form of political opposition.’ According to the EOHR representative ‘“someone who refuses to perform [their] military service” will face consequences as imposed by Egyptian law”.’[footnote 129]

7.2.2 The IRB August 2018 report also quoted a HRW researcher who stated that the default position of the Egyptian authorities is that avoiding military service would be considered ‘“an offence and punished as stated by [the] law.”’[footnote 130] The same report quoted a representative of the “No to Compulsory Military Service Movement” (NoMilService), an Egyptian non-governmental organisation that was co-founded in 2009 by Nobel Peace Prize nominee and Egyptian conscientious objector Maikel Nabil, who stated, ‘“because Egyptians of all political affiliations - even those who support the government - tend to avoid conscription, Egyptian authorities consider avoiding conscription an act of political opposition only if it is done on political grounds.”’[footnote 131]

7.2.3 A HRW researcher quoted in the IRB August 2018 report indicated that Egyptian authorities would consider the actions of conscientious objectors to be political dissidence.[footnote 132] The IRB August 2018 report also quoted a NoMilService representative who stated:

‘“The Egyptian army considers conscientious objection an existential threat. Conscripts in Egypt are forced to pledge their allegiance to the president of Egypt and the political regime and refusing to serve in the army is effectively refusing to pledge one’s allegiance to the president and the regime. Conscientious objection is not seen as an act of conscience or belief, but an act of challenging the regime, its laws, its authority, and its legitimacy.”’[footnote 133] (see Conscientious objection).

7.3 Societal perception of evasion/ conscientious objection

7.3.1 The IRB August 2018 report quoted a representative from the European Bureau for Conscientious Objection (EBCO), who stated that ‘”conscientious objection is treated as a taboo in Egyptian society; consequently, the little group of Egyptian conscientious objectors prosecuted by the military administration does not find any support, even from national human rights groups.”’[footnote 134]

7.3.2 HRW Researcher specialising Egypt contacted by CPIT by email on 22 July 2022 (HRW response July 2022) stated on the question of how society perceive evaders that, ‘[t]he society would be more neutral towards evaders because many people perceive mandatory conscription as a negative experience that delays career pathways and practical and family life (e.g., getting married). When a man proposes to a woman, one of the first question the woman’s family will ask is whether the man finished his service”’.[footnote 135]

7.3.3 A MEE 2016 article reported that:

‘Talking about conscription is a taboo subject in Egypt. Those who have served are reticent to discuss their experiences, fearing a backlash from the army. Even human rights groups in the country are wary of giving statements in case they are punished by the courts (rights groups based in Egypt refused to discuss the matter with MEE). And for the local media, reporting on the issue is a red line they refuse to cross.’[footnote 136]