Part 1: introducing opioid substitution treatment (OST)

Published 21 July 2021

Applies to England

1. What OST is and how it works

1.1 Core elements of OST

People who become dependent on heroin or other illicit opioids often benefit from opioid substitution treatment (OST). The same is true, but much less common, for people who become dependent on opioids prescribed for pain.

OST has 2 core elements: pharmacological and psychosocial.

The pharmacological element involves replacing illicit opioids with a prescribed replacement opioid, such as methadone or buprenorphine.

The psychosocial (talking) element supports people to stabilise on the replacement opioid and to then make positive changes to their lives and recover from their drug use. OST is most commonly used for illicit heroin use so that is the focus of this guidance.

The long-term goal of OST is for the service user to completely stop using illicit opioids. In the shorter term, reduced illicit opioid use can reduce risk. OST is effective in reducing:

- illicit opioid use

- drug-related injecting

- blood-borne virus (BBV) transmission

- offending

- premature mortality (early death)

The national clinical guidelines on drug misuse and dependence outline best practice for OST.

1.2 Countering some myths about OST

There are some beliefs about OST that are commonly held by people who use opioids and drug treatment staff but have little basis in fact. These myths can deter people who use opioids from choosing OST and lead to doses that are not optimised. So it’s vital that drug treatment and recovery workers can debunk the myths that some service users starting treatment have about OST.

Below are responses you can give to counter some commonly-held beliefs about OST.

It’s harder to get off OST medication than heroin, so going on OST will make it too difficult to detox in the future.

Methadone and buprenorphine are long-acting opioids (longer than heroin). This means that coming off them can take longer and, if you come off too quickly, withdrawal symptoms can last longer. For people to successfully detox, it is important to start from a stable situation, and this is often best achieved by taking a long-acting opioid.

OST replaces heroin addiction with addiction to the OST medication.

OST medicines work in similar ways to heroin, so they do create dependence, with tolerance, and withdrawal if someone stops taking them. But dependence is not addiction. When you take away the other elements of addiction (such as craving, withdrawals, money and drug-seeking), it’s easier to end the dependence when someone is ready.

Methadone gets in your bones.

Methadone does not get into your bones or do any harm to your skeletal system. It is common for service users to report having aches in their arms and legs. This discomfort is likely to be caused by mild withdrawal symptoms and suggests that their dose is not yet optimised.

Reducing an OST maintenance dose gradually is best.

Evidence suggests that it’s best for service users to stay on a stable maintenance dose that works for them and then, if and when they’re ready, have a clearly defined detoxification. This can be up to 12 weeks for most people or up to 28 days for inpatients.

If a dose is working for the service user and they do not have side effects, then there’s no reason it should be lowered unless this is part of an agreed plan. Lowering their dose might mean it does not work as well, so service users should not be encouraged to gradually reduce. However, some people do want to try a longer, slower, gradual reduction and they should be supported if they make an informed decision to do so.

You should be ready to increase the dose again if the lower dose does not prevent withdrawals or the service user starts using illicit opioids again.

Methadone rots your teeth and makes you gain weight.

Methadone oral solution is available with and without sugar. The sugar-containing solution contains about the same amount of sugar as a cola drink so is unlikely to damage teeth if someone has good dental hygiene and care. It is usually poor dental hygiene, not going to the dentist and cravings for a high sugar diet associated with opioid dependence that cause many people who use opioids to have bad teeth.

Weight gain is usually caused by a poor diet and lack of exercise, not the sugar in a daily methadone dose.

OST would not actually help me to use less heroin anyway.

There is good evidence that OST reduces the use of illicit opioids, and that the higher the methadone dose, the lower the amount of heroin people will use.

1.3 How OST works

OST medications broadly work by reducing or stopping withdrawal and cravings without producing the extreme highs that heroin and other illicit opioids cause. At the right dose, they also stop heroin from causing a high. This is known as the blockade effect.

The 2 medications used for OST in the UK are methadone and buprenorphine. These are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for opioid substitution treatment.

Methadone is a synthetic opioid agonist, which means it acts on the opioid receptors in the brain. These are the same receptors that other opioids such as heroin act on. Although it occupies and activates these opioid receptors, it does so more slowly than heroin. It produces some opioid effects like emotional detachment and relaxation, but in an opioid-dependent person, it does not produce a high. Methadone is most commonly prescribed as a liquid that is swallowed (oral solution) but it is also available as a tablet or as a daily injection.

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, meaning that it acts on the same opioid receptors in the brain but activates them less strongly than full agonists do. It has some of the same opioid effects as methadone but has less of a sedating effect. Buprenorphine is most commonly prescribed as a tablet that dissolves under the tongue or as a film that dissolves on the tongue, but it is increasingly likely to be available as a long-acting (7 days or 1 month) depot injection.

One formulation of buprenorphine comes with naloxone in the same tablet (sometimes branded as Suboxone). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist, meaning that it blocks the opioid receptors in the brain preventing opioid drugs from having an effect. Combined buprenorphine-naloxone tablets work the same way as normal buprenorphine tablets if taken as intended (dissolved on the tongue), but if the combined tablet is crushed and injected or snorted, the naloxone will stop the buprenorphine working.

2. Why you should use OST

2.1 Reasons for using OST

There are a number of good reasons for using OST, because:

- it reduces drug use, injecting, mortality and offending

- methadone and buprenorphine are recommended by NICE

- it maintains a service user’s tolerance for opioids and reduces withdrawal symptoms and cravings for heroin

- it gives people the stability to focus on broader recovery

- it helps people come off heroin and OST medication altogether

2.2 Evidence base for OST

There is a strong evidence base for the effectiveness of OST, which is outlined in the NICE guidance on methadone and buprenorphine. The evidence base includes the following:

- OST is the most widely evaluated of all treatments for heroin dependence.

- There is strong evidence that OST is effective at suppressing heroin use.

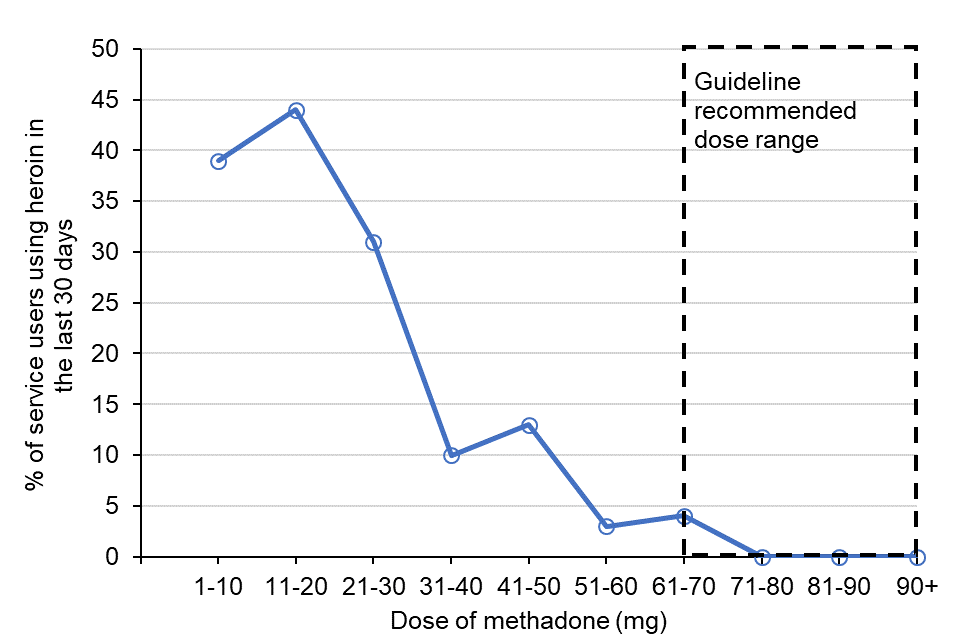

- Higher doses of OST, within guideline-recommended margins (60 to 120mg for methadone and 12 to 16mg (up to 32mg for some) for buprenorphine), are associated with less illicit drug use and better treatment outcomes.

- OST is very effective at keeping service users in treatment: people are 3 to 4 times more likely to stay in treatment if on methadone compared to no OST.

- Being on OST halves the risk of fatal overdose.

- OST is associated with decreases in illicit drug injecting and sharing of injecting equipment, so dramatically reduces the rate of BBV infections such as HIV and hepatitis C.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between methadone dose and the proportion of service users on that dose who were still using heroin. This chart shows the percentage of service users who used heroin in the last 30 days decreased from 44% at 11 to 20mg of methadone to 0% at 71 to 80mg and higher. The data is taken from research in the United States in the early 1990s.

Figure 1: the relationship between methadone dose and heroin use (adapted from studies by Ward, Mattick and Hall 1992 and Ball and Ross 1991)

3. Roles and responsibilities

This section outlines the main functions that different professionals have when working together to deliver OST.

3.1 Your role in OST

As a drug treatment and recovery worker, you are at the frontline of drug treatment and recovery and you will usually be the service user’s main point of contact with the service.

You play a crucial role in engaging and supporting service users through treatment and recovery. This involves having conversations about OST so they can make informed choices.

The main parts of your role are:

- identifying people who may be suitable for OST

- providing information about treatment options, including OST medications, and arranging a further discussion with the prescriber if OST might be appropriate

- identifying what service users want from OST

- exploring the benefits and limitations of OST with the service user

- giving harm reduction advice, information and interventions, including supplying and advising on the use of take-home naloxone

- preparing service users for prescriber assessment for OST

- arranging medicine pick-ups and supervised consumption in a way that works for the service user’s lifestyle

- reviewing and changing supervision arrangements and treatment and recovery care plans with service users and your multidisciplinary team (MDT)

- working with service users and your MDT to make sure that OST is working for the service users

3.2 Prescribing and dispensing

OST prescribing is typically done by a consultant psychiatrist or other medical specialist, non-medical prescriber (nurse or pharmacist) or GP (usually where there are shared care arrangements in place). A decision to prescribe, which medicine and how much to prescribe will depend on:

- the service user’s physical, mental and social wellbeing

- the overall treatment and recovery goal and care plan agreed with the individual service user

- the clinical guidelines (orange book)

- locally agreed protocols

Pharmacists are responsible for dispensing and supervising consumption of substitute medications. This includes:

- dispensing medication in specified instalments, ensuring the service user takes supervised doses correctly and monitoring their responses

- liaising with the drug treatment team to contribute to treatment and recovery care planning

- maintaining contact with the service user, checking they are safe and healthy, and encouraging them to get physical and mental health problems seen to

Pharmacists can further support OST service users through:

- needle and syringe programmes

- harm reduction services, including basic assessment and harm reduction advice and screening

- providing take-home naloxone

- providing BBV testing, treatment and vaccinations

3.3 Specialist physical and mental healthcare

Drug specialist doctors and nurses support OST outcomes by offering physical and mental healthcare interventions. This might include managing infections from injecting wounds or treating depression associated with drug use.

Psychologists working in your services can help you to think about service users in a psychological way, understanding the role of previous experiences such as trauma in the way they may relate to treatment.

3.4 Peer support

Peer support from people who are further on in their recovery journey is an effective way to show people in treatment that recovery is possible and also to help motivate them to work towards recovery.

Peer supporters can support service users on OST in one-to-one or group psychosocial sessions, and by accompanying them to appointments or mutual aid meetings.

4. Drug treatment conversations: what works

Service users starting treatment usually have mixed feelings about reducing or stopping using heroin. Drug treatment and recovery workers can use some techniques to help service users with these feelings.

Approaches to drug treatment conversations that work include:

- taking a non-judgmental and collaborative approach

- asking open-ended questions

- recognising reasons for continuing to use heroin and exploring the service user’s perspective

- reflecting back and summarising what they have said

- eliciting change talk by asking questions that identify how important it is to make a change

- asking the service user if they are happy for you to provide information and advice

- setting clear goals and reviewing them regularly

- building on learning from previous drug-free periods and affirming personal strengths and resources

- identifying recovery support needs and offering peer support opportunities

Approaches to drug treatment conversations that typically do not work include:

- taking a judgemental, blaming, punitive approach

- giving your point of view and telling them what to do

- arguing with the service user

- not listening carefully to what the service user has to say

- assuming the client is ready, willing and able to change

- following a rigid script and tick box approach to providing information whether the service user is interested or not

- not setting goals or forgetting to review them

- focusing on weaknesses and failures

- focusing on the medicine-only and your relationship with the service user rather than their wider needs

A good therapeutic relationship between you and the service user should allow for discussion about drug use without them fearing they will be discharged from treatment. However, you must be prepared to actively discuss their concerns and encourage them to reduce risks.

4.1 Motivational interviewing

A good therapeutic approach is typically empathetic, non-confrontational, collaborative and non-judgmental, and uses elements of motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a set of therapeutic principles and techniques that help service users increase their motivation to change. With MI, you take the position of a collaborative partner in discussions with the service user about their drug use. MI can include:

- providing feedback on structured assessments or test results

- asking open questions

- listening

- summarising the ideas that the service user has expressed that support behaviour change

- reflecting the service user’s thoughts and ideas back to them

- providing affirmations that support the change process

The underlying principle is that service users persuade themselves that change is desirable, achievable and will bring benefit.

The 3 main elements of basic MI are outlined below.

Adopt a guiding communication style

A guiding communication style is not the same as directing or following. You should act as a well-informed guide, engaging and working together with the service user but emphasising their autonomy. To do this you should:

- ask open-ended questions

- listen to the service user and provide brief summaries and reflections of what they have said

- elicit the service user’s own knowledge then ask permission to give advice and information, exploring their reactions to this information

Add strategies to elicit change talk

People tend to believe what they hear themselves say. So, working with the service user to help them set their own goals and explore the reasons behind them will be more effective than simply telling them that they need to change. Some strategies to help you do this are listed below.

- Setting an agenda for keyworking sessions helps the service user explore what they want to change. Invite them to select an issue to work on.

- Invite the service user to explore the advantages and disadvantages of changing their behaviour.

- Ask the service user how important it is for them to change their behaviour and how confident they feel that they can do it. Using a scale is useful for this (for example, a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most important and most confident). This will help you target interventions.

Respond appropriately to change talk

Pay special attention to any change talk you hear from the service user. You can repeat these statements back to them in your reflections and summaries. Ask if they are ready to make the change and what you can do to help.

5. Initial conversations about treatment options including OST

In your role as a frontline drug treatment and recovery worker, you’re often the first person to discuss the treatment options including OST with service users and their goals for treatment. By starting with the service user’s reasons for coming to treatment, you can begin to understand what matters to them right now. This context will help you to work together with them to develop a treatment and recovery care plan tailored to their needs, strengths and motivations.

You play a vital role in discussing the benefits of OST with people who use heroin.

Thinking about the evidence base for OST, how would you explain the benefits to a service user?

The first step is to find out what the service user already knows so that you can provide information that is helpful to them and make them an active, rather than passive, participant in the conversation. In MI, this approach is called ‘elicit-provide-elicit’.

Below are some example explanations of the evidence for OST that you can use in discussions about OST with service users. They will help you to talk about the evidence for OST’s effectiveness in simple language that any service user can understand.

- OST should stop withdrawal symptoms and can reduce cravings too so you’re less likely to take heroin. It can take a while to get on the right dose and we understand that some people keep using heroin for a while until the right dose is reached.

- You’re more likely to stay in treatment and get the benefits from it if you’re on OST, and on a dose that works for you.

- Generally, people do better on higher doses of OST medicine, but we’d work with you to get the right dose for you.

- If you’re on OST, you’re much less likely to have an overdose that kills you.

- OST helps people to stop injecting so you’re much less likely to get BBV infections like hepatitis C and B, or HIV.

6. Types of interventions when entering treatment

Your early conversations about treatment with people who use opioids should explore the range of pharmacological, psychosocial and harm reduction interventions.

6.1 Pharmacological options when entering treatment

For people who use opioids, there are 2 pharmacological options when they enter treatment:

- Induction and stabilisation on OST.

- Opioid detoxification.

Induction and stabilisation on OST

The aim of induction and stabilisation is to quickly but safely get the service user to a dose of OST medication that treats withdrawals, reduces cravings and stops or significantly reduces illicit drug use. It also supports the service user to reduce their health risks. This process of adjusting dose to effect is called titration.

Methadone plasma levels can build up over the first few days of treatment sometimes to toxic levels. This can happen even at relatively low doses, so titration should always be done carefully. Buprenorphine titration can usually be done more quickly and with less risk than methadone.

Opioid detoxification

You should explore the option of opioid detoxification with service users in early conversations about OST (but it should be available at any stage of treatment). Opioid detoxification is not the same as gradually cutting down. Gradually cutting down might be a later option that’s suitable for some service users. Detoxification is a clearly defined process, agreed with the service user, that supports them to safely and effectively stop using all opioids while minimising withdrawals.

At the very beginning of treatment, detoxification can mean:

- gradually coming off an illicit opioid (sometimes using OST medications but often just medicines that treat withdrawal symptoms)

- being titrated onto OST but then quickly, safely and comfortably reducing it to zero

More commonly, detoxification occurs later in treatment and means safely and comfortably reducing OST to zero after a period of maintenance. Maintenance means the prescriber and service user agree that the service user needs to stay on OST for longer than just a few months. Detoxification usually lasts up to 28 days as an inpatient or up to 12 weeks as an outpatient.

Service users considering detoxification may want you to reassure them that they can manage withdrawals. Assure them that you will offer them support during the detoxification process and that the prescriber can prescribe medication to minimise the discomfort of withdrawal.

6.2 Psychosocial and harm reduction interventions

Whatever pharmacological treatment a service user chooses, psychosocial and harm reduction interventions such as overdose prevention training are also vital. If someone chooses opioid detoxification, you need to provide psychosocial support before and during detoxification and support the service user to remain drug-free after detoxification.

A service user might only start treatment to get medication, but the contact with them creates an opportunity to provide psychosocial and harm reduction interventions and access to peer support. Services should offer an accessible and flexible programme that service users can engage with voluntarily.

You can offer service users psychosocial interventions that support safe prescribing including identifying their goals and regularly reviewing these. Having a therapeutic relationship with the person allows you to recognise and affirm their strengths while supporting them to consider what matters to them and work towards making positive changes.

Some services use contingency management (CM) to encourage and acknowledge progress (for example, negative drug test results) by rewarding the service user with cash or shopping vouchers. CM requires a clear protocol and staff supervision to make sure it is done ethically and effectively.

7. When OST is suitable for a service user

7.1 Conditions that need to be met to prescribe OST

An MDT should discuss anyone who has come to a service using opioids or is at risk of returning to opioid use. Outlined below are the conditions that would normally need to be met for a prescriber to prescribe OST.

Regular opioid use

You will need to consider if the service user is taking opioids regularly.

People who only occasionally use opioids are usually unsuitable for OST. The service user needs to be either using opioids regularly right now or likely to start using them regularly again very soon. If there is any regular opioid use, or risk of returning to it, an MDT should discuss the case.

Current opioid dependence

You will need to consider if there is convincing evidence that the service user is currently opioid dependent. This includes evidence of tolerance or opioid withdrawals when they do not take opioids (see section 7.2: Signs of opioid withdrawal or use a withdrawal scale such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and the Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS)), or other indicators of dependence – see Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) criteria.

Assessment confirms the service user needs OST

You will need to consider if the assessment, including the service user’s history, examination and drug testing confirms their need for treatment and that OST medications can be safely used.

This includes evidence of injecting sites or of opioid withdrawals (see section 7.2: Signs of opioid withdrawal) and no physical or mental health problems contraindicating prescribing.

The service user can stick to what they’ve been prescribed

You will need to consider if the prescriber is satisfied that the service user will be able to stick to the prescribing regimen.

The service user will need to pick up and take their OST medicine regularly and make efforts to avoid using other drugs, excess alcohol and unprescribed medicines. There may be challenges along the way during treatment, and you would not usually deny someone treatment that could be life-saving, but there may be no point starting OST if someone cannot stick to it.

The service user is only on one OST prescription

You will need to make sure that the service user is not receiving an opioid prescription from another service to manage their opioid dependence.

It’s vital to avoid ‘double scripting’ to reduce the risk of overdose or drug diversion.

7.2 Signs of opioid withdrawal

Observable signs of opioid withdrawal include:

- yawning

- coughing

- sneezing

- runny nose

- lachrymation (weeping eyes)

- raised blood pressure

- increased pulse

- dilated pupils

- cool, clammy skin

- diarrhoea

- nausea

- fine muscle tremor

Self-reported signs of opioid withdrawal include:

- restlessness

- irritability

- anxiety

- sleep disorders

- depression

- drug craving

- abdominal cramps

Restlessness, irritability and anxiety may also be observed by professionals.

8. Choosing an appropriate opioid substitute

People who use heroin will often already have views on OST medications based on their own or others’ experiences.

Oral methadone and buprenorphine are both effective and recommended by NICE. We will focus on these as they are the most commonly used. Other medicines are sometimes available, including injectable diamorphine and long-acting or depot injections of buprenorphine.

Service users should be involved in the decision about which medication to choose based on the pros and cons of each. It’s not a case of one being better. It depends on the service user and the current clinical situation.

Your initial conversation with a service user will explore their current attitudes to the medications and prepare them for their prescriber assessment. Clinical factors that guide which medication to choose include:

- the service user’s pre-existing preference for either medicine – though it is important to ask why as they may be misinformed

- past good or bad experiences of being prescribed either medicine

- safety concerns

- likely need for strong opioids for pain management (for example for upcoming surgery)

- interactions with other drugs or medication the service user is taking

- local factors, such as lack of availability of supervised consumption (which may then favour buprenorphine)

8.1 Pros and cons of methadone

Advantages of choosing methadone as an OST medication include the following:

- It is a replacement for heroin so, at the right dose, it will completely prevent withdrawal symptoms.

- Although people are unlikely to get a high from it, they might get some opioid effects like emotional detachment, relaxation or drowsiness.

- Supervised appointments are quick because methadone comes in a liquid form that is easily swallowed, rather than a tablet or film that takes longer to dissolve.

- People taking methadone are more likely to stay in treatment and usually stay for longer than people taking buprenorphine.

Disadvantages of choosing methadone as an OST medication include the following:

- Starting methadone treatment is more difficult and slower than buprenorphine and carries more risk of overdose as even small doses of methadone can build up in your blood over time.

- Methadone can be harder to come off than buprenorphine for some people because methadone is a full agonist while buprenorphine is a partial agonist.

- Even on its own, methadone can cause fatal overdose. Finding the right dose needs to be done carefully and can take time.

- Overdose is more likely if methadone is taken with other central nervous system depressants such as alcohol, benzodiazepines and gabapentinoids.

- Methadone is more likely to make people drowsy than buprenorphine but, if this happens, it suggests the dose is not right.

- Methadone has more drug interactions and some people with heart problems should avoid it.

- A small amount of methadone ingested by someone not used to taking opioids can cause overdose. Safety measures should be put in place to prevent this, for example, supervised consumption and locked drug storage boxes, particularly where the service user is living with or around children.

8.2 Pros and cons of buprenorphine

Advantages of choosing buprenorphine as an OST medication include the following:

- Buprenorphine comes as a tablet or film and so is easier to carry.

- Buprenorphine is less likely than methadone to cause a fatal overdose.

- It is less sedating than methadone so service users should have a clearer head.

- It is easier to wean off at the end of treatment.

- Can be used less than once per day and sometimes just a few times a week if dose is adjusted.

Disadvantages of choosing buprenorphine as an OST medication include the following:

- People can experience withdrawal symptoms at the beginning of titration. These can be minimised with more rapid but still careful titration.

- People may have to use different strengths of tablet to get the right dose.

- Since buprenorphine usually comes in tablets that are dissolved under the tongue, or film dissolved on top of the tongue, supervision takes longer than methadone and it does not work if it’s swallowed.