Evaluation of the LORCA programme

Published 4 August 2023

Executive summary and key findings

Background: Through the National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS) (2016-2021) and National Cyber Security Programme, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) worked with partners across government and industry to develop an ambitious programme of interventions to help grow the UK’s cyber security sector and ecosystem. This included two cyber innovation centres in London and Cheltenham.

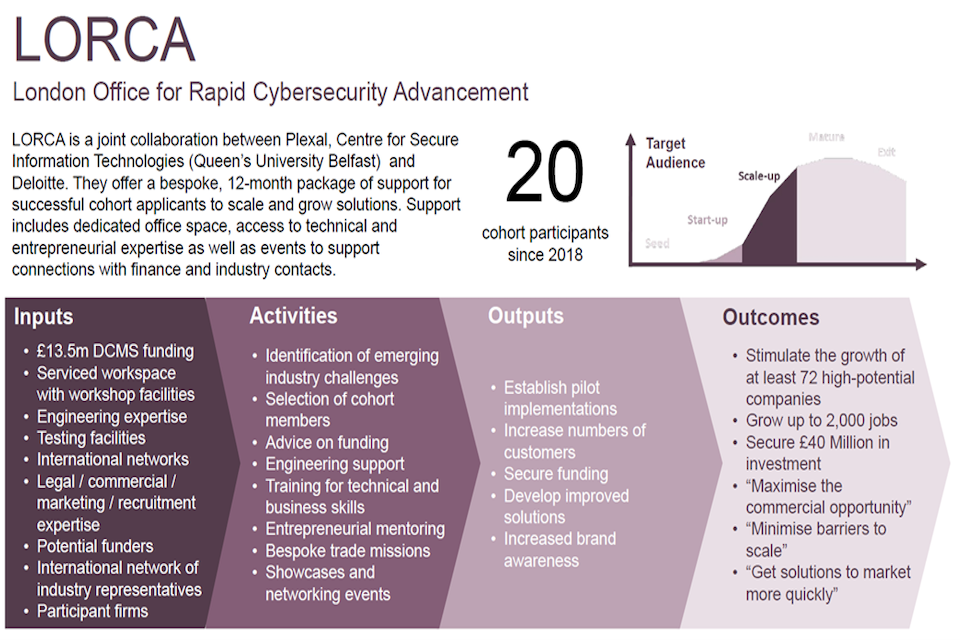

LORCA: The cyber innovation centre in London is called LORCA (London Office for Rapid Cybersecurity Advancement) and it is a joint collaboration between Plexal, the Centre for Secure Information Technologies at Queen’s University Belfast, and Deloitte. LORCA offered a bespoke package of support for successful cohort companies to scale and grow cyber solutions. Support included dedicated office space, access to technical and entrepreneurial expertise as well as events, such as LORCA Live and LORCA Challenges, to support connections with finance and industry experts. Over four years LORCA was tasked with stimulating the growth of at least 72 companies; growing up to 500 jobs; securing £40 million in investment and getting solutions to market more quickly

Scope of the Evaluation: RSM UK Consulting LLP was appointed by DCMS in March 2022 to undertake the evaluation of LORCA with the following aims.

- To determine how the LORCA Programme has performed over the last four years

- To clarify if the programme has produced benefits

- To help DCMS understand the impact of the programme and issues related to government intervention to help grow the cyber security ecosystem

- To explore whether the same benefits would have been achieved without government intervention

This evaluation addresses the complete timeline of the LORCA project, detailing the performance and impact of the project since its inception in 2018 through to March 2022, with a particular focus on:

- the bespoke support LORCA offered through providing space, arranging events, such as the annual LORCA Live conference and networking opportunities, and fostering collaboration

- the LORCA Ignite programme which ran between April 2021 and March 2022 and the extent to which it has supported the scaling growth of six of the most promising companies from within the LORCA graduate community

- the three challenge-led programmes and assessing the extent to which they have encouraged start-ups and industry to co-create new solutions that address these challenges

Methods: The evaluation methodology was agreed with DCMS and included the following:

- a rapid Evidence Assessment to inform the evaluation about the types of variables that should be considered in assessing the success of cyber accelerators;;

- a Theory of Change Workshop to get a sense of how LORCA fitted into the cyber ecosystem and what some of the wider outcomes and impacts were intended

- Mapping the Cyber Security Ecosystem;

- analysis of Programme Monitoring Information and Impact Data from direct beneficiaries of LORCA, including information about (a) growth of companies, (b) jobs secured and (c) investments, to assess the cohort companies’ growth relative to average UK cyber security market growth;

- interviews with 22 strategic stakeholders and an online workshop with programme beneficiaries in May 2022 to explore perceptions of how well LORCA met its core aims and objectives, and suggestions for improvement; and

- recommendations for the future given ongoing changes in the cyber security market.

RSM also completed three different online surveys with (a) all five cohorts of LORCA with a separate section for participants in LORCA Ignite; (b) participants from the three LORCA Challenges; and (c) a counterfactual group of companies matched to the successful LORCA cohort companies. We analysed the impact of LORCA by comparing participating companies to a matched group of similar firms based upon certain Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) such as equity transactions, number of employees, and turnover.

Key Findings: Plexal was awarded the contract from DCMS in 2018, with the initial contract intending this to spread between 2018 and 2021. However, the programme was extended by one year to 2022. LORCA delivered on budget for each of the four years the programme took place. The granting of the extension and the additional costs were due to the addition of several contract variations and an extension of the original programme. LORCA was designed to interact with, and counterbalance, the threats and challenges faced by the industry alongside other programmes within the national cyber security programme.

LORCA captured monitoring information on participants at the beginning of the programme, at a 3-month and a 6-month interval, and at the end of the programme at 12 months. Job growth, investment growth, revenue, number of new contracts and Proof of Concepts, have been collected across all 5 cohorts for the participating firms. The programme delivered on its key economic performance indicators, with the figures below representing the programme’s cumulative performance from the 5 cohorts delivered over 3 years. This includes:

- 72 businesses supported

- 865 jobs created

- £37m of revenue uplift

- £210m investment raised [footnote 1]

In general, the people we interviewed and surveyed in our analysis felt that the Executive Team had done a good job in terms of governance. This is particularly notable when discussing the LORCA management team, who were extremely well thought of by the majority of those interviewed. In terms of the cohorts our review of the criteria used by LORCA to evaluate firms applying to join LORCA concludes that the processes were fair and transparent, and our stakeholder interviews confirmed that the decision making processes were robust and transparent.

Our report describes what worked well and less well in LORCA and there were a variety of different themes that emerged. A dominant theme that emerged was the positive attitudes about the technical support provided during the programme. A key theme that also emerged on the topic of what worked less well was the fact that some aspects of the programme were too generic. This view was held by interviewees in larger companies or who had worked previously in start-ups.

All stakeholders felt that the bespoke elements of the programme and the opportunities for networking pre-COVID-19 were some of the key reasons for the programme’s success. This should be considered in any future iterations of accelerator programmes. As well as this, the success of the challenges should be noted as something to take into future delivery, allowing for an increased connection between government, participants and industry in a way that provides greater support to the sector through its problem-solving focus and attention paid to real-world cyber issues.

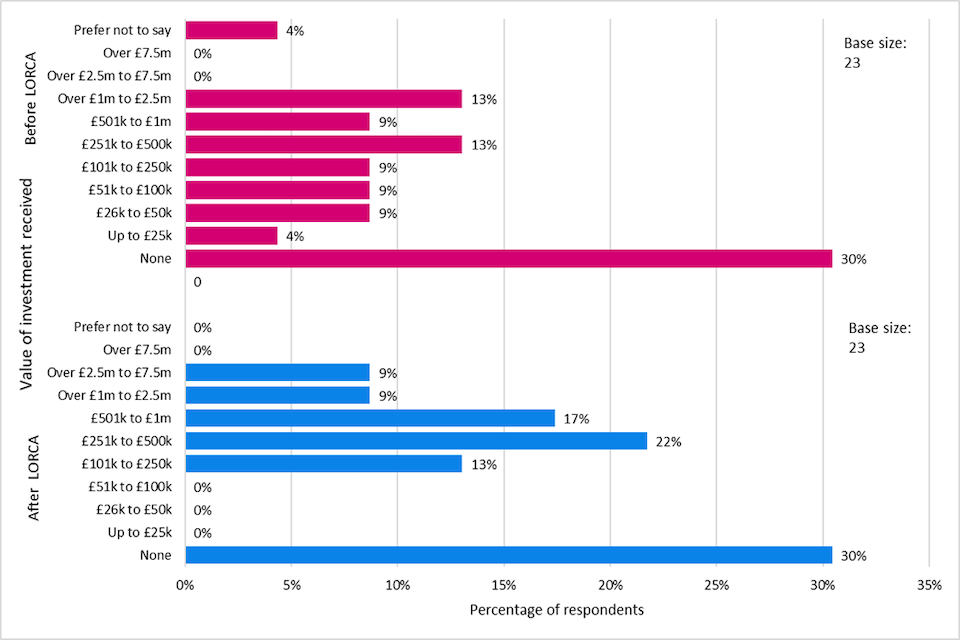

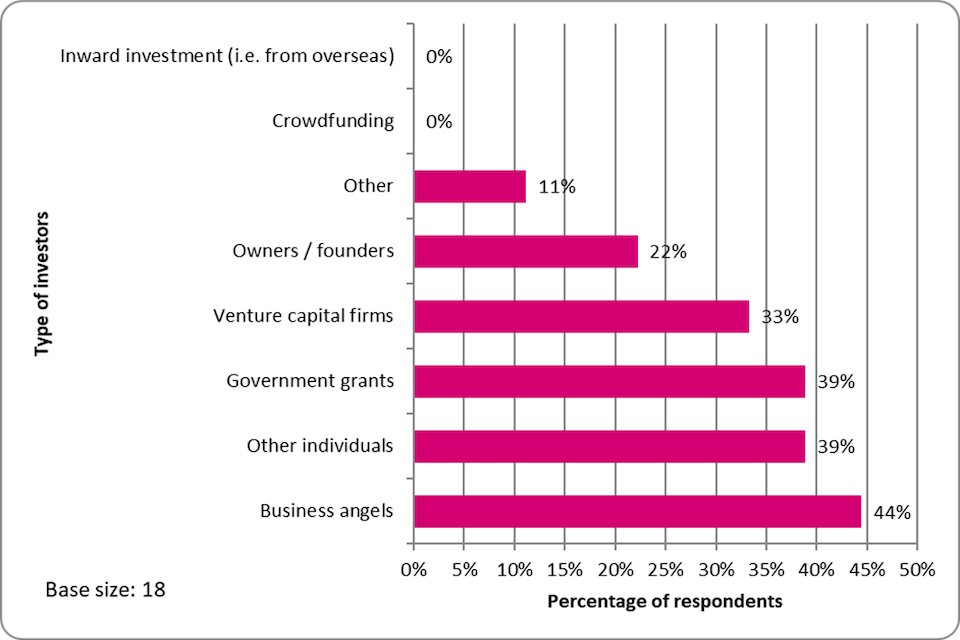

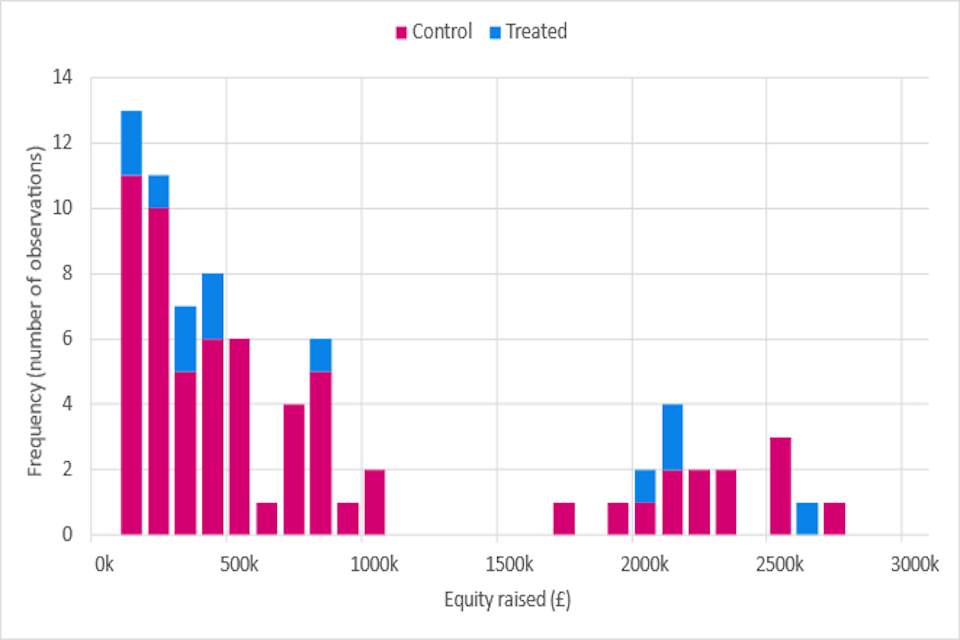

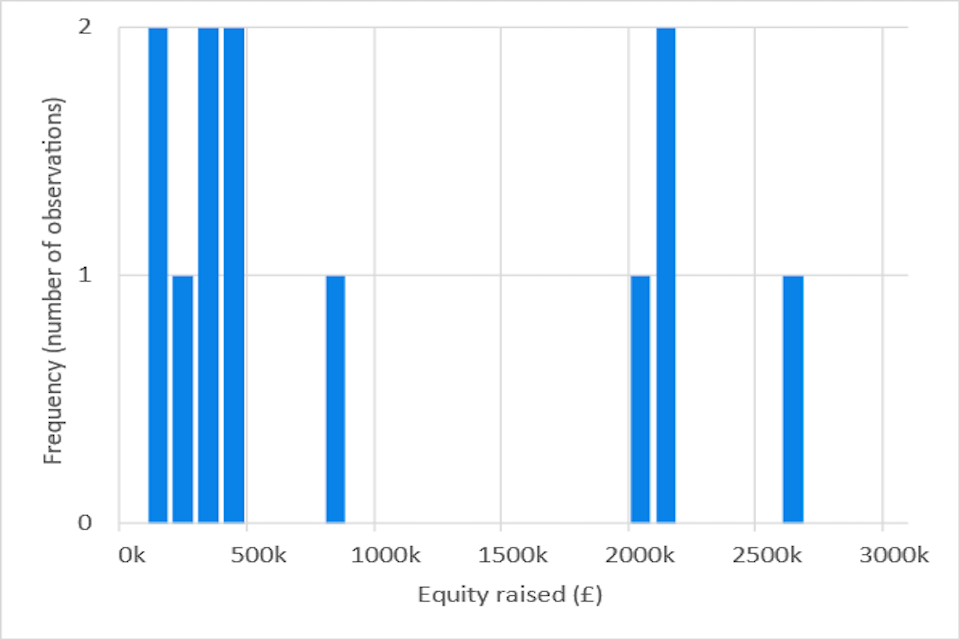

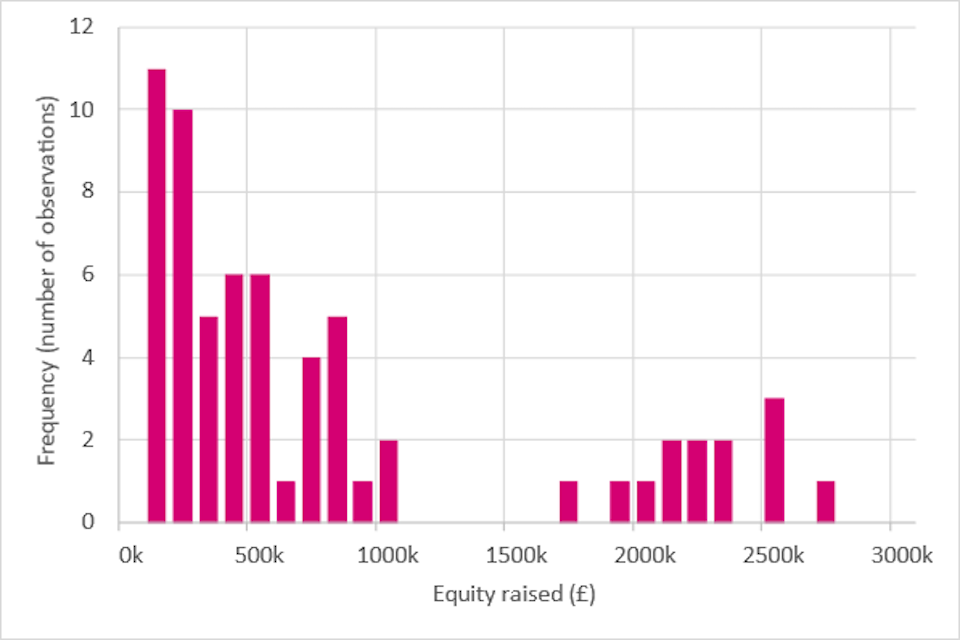

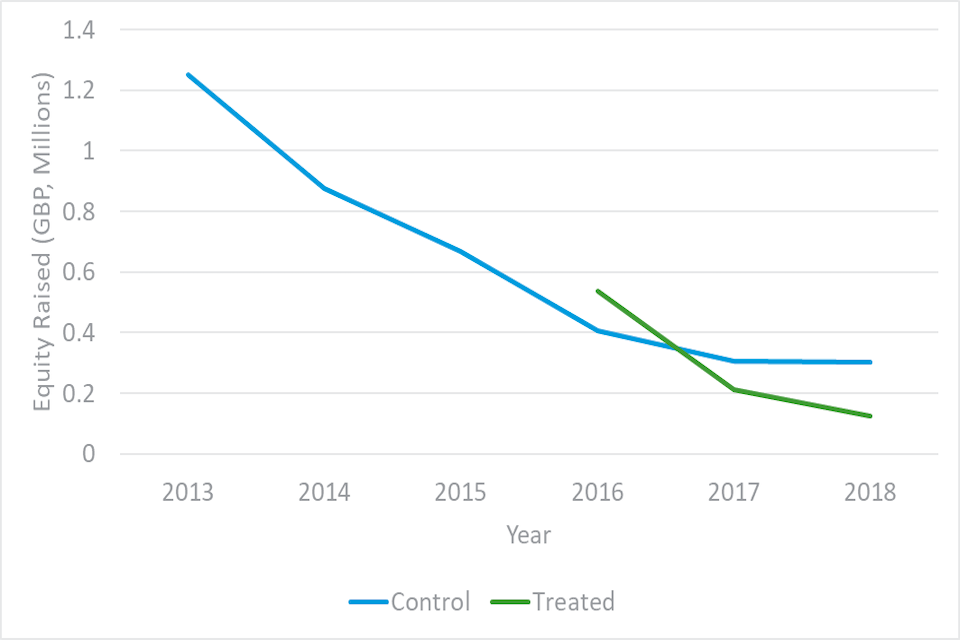

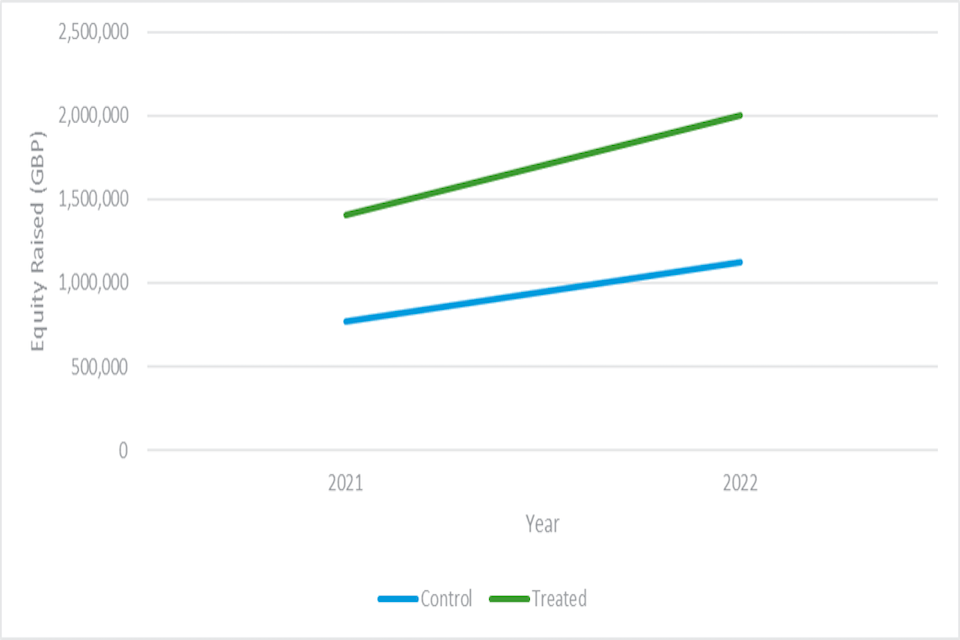

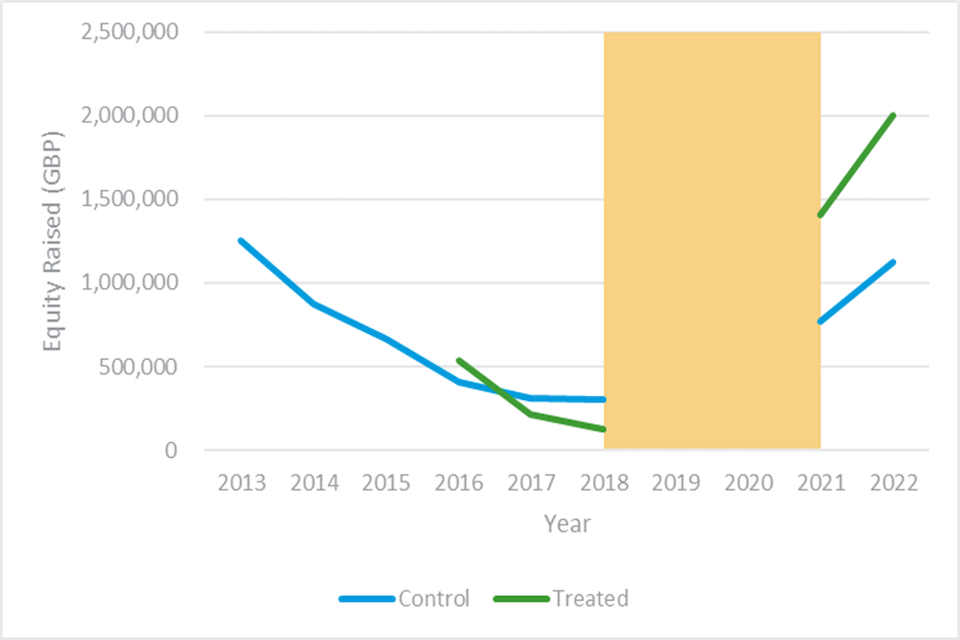

We analysed secondary data using the Beauhurst database, which tracks the performance of 82,463 growth firms in the UK, where 1,424 firms operate in the digital security sector. The KPI we used for our assessment was equity fundraising, which was selected as a precursor for business investment; as early-stage firms are more likely to show any potential impacts from the LORCA programme through this metric, given that finance is usually directed towards research and development (R&D) and business development. We found that post-LORCA participation, there has been an upswing in equity fundraisings for participating firms compared to non-participants. The increase in equity raised by participating companies is steeper than that of non-participants, which is an interesting observation; however, caution must be taken when attributing any difference to the LORCA programme given this is an early-stage evaluation and fuller data are still yet to be realised through KPIs such as revenue.

Limitations: Our evaluation had some challenges and hence there are key limitations which must be acknowledged. First of all, the engagement of LORCA firms with our surveys was lower than expected. The nature of the sector and the sensitive nature of some of the questions we were asking perhaps contributed to this low response rate. Secondly, it was difficult to establish a like-for-like counterfactual group of firms to undertake the Difference in Difference (DiD) analysis to evaluate the impact of the LORCA programme. Good data about impact is typically collected over a long period of time. For LORCA, quantifying impacts is difficult as very little time has passed since participants completed the programme, and COVID-19 may have impacted in ways that we are not yet aware of. Typically, realisations of impacts through increased investment in R&D and other broader business activities to generate sales revenue have a lagged element. A future consideration to estimating the impact of the LORCA programme would be through DiD econometric modelling.

Recommendations

- In terms of the future funding, we recommend that funding for the Challenges and some type of annual in-person event for the cyber sector should continue. LORCA has been successful in showcasing a model for future support; whilst DCMS continues to support the UK cyber security sector through programme such as Cyber Runway and CyberASAP, other organisations are also now active in the ecosystem and capable of delivering similar support.

- We recommend that the Challenges continue to be developed further. Several key stakeholders acknowledged the importance of the Challenges in developing closer relationships between participants, industry, and government. The Challenges’ potential for providing actionable solutions to cyber problems was also noted, with some of the findings from challenges already being used to inform government policy. If this potential is realised, it could also develop into a self-sustaining programme, with industry being more likely to fund activities that directly contribute to solving the real-world issues they are facing.

- The bespoke elements of the programme of support should be recognised as a key reason behind LORCA’s positive reviews and should be central in the development of future programmes. This element of the delivery process provided participants with a more well-rounded and useful support mechanism to contribute to future growth. A crucial element in the success of this element of delivery is ensuring a baseline needs analysis is undertaken for all participants when entering any programme to develop a precise understanding of their requirements and areas of interest. We recommend that this baseline needs analysis is undertaken in all future programmes of this nature.

- Transforming an entirely government-funded programme into a self-sustaining model over a relatively short period of time was arguably unrealistic and, therefore, we recommend DCMS consider alternative funding models in their Invitations to Tender for this type of work in the future. From our analysis, it would appear that a shift from this government-funded model to one focused on private funding was simply too great to achieve in the time period given.

- We recommend DCMS considers evaluating the LORCA Programme at a later stage. As with many evaluations of this nature it is too early to be able to draw out any meaningful impacts from the programme. We need more evidence about key performance indicators such as investment and revenue, so that econometric modelling can then be applied to better determine LORCA specific impacts.

Conclusion: Although the evidence we have is limited in some respects, on balance it is fair to conclude that LORCA was delivered on time, to budget and met or exceeded almost all of the original targets it had been set. Aspects of LORCA worked extremely well, such as facilitating networking, and a regular in-person event should continue as well as the challenge-led approach to solving real world problems. LORCA met a need in the cyber security ecosystem at a point in time. However, post-COVID-19, there is not enough evidence to suggest that the decision to cease funding of LORCA should be overturned.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

The government is committed to making the UK the safest place in the world to be online and the best place in the world to start and grow a digital business. A key aspect of this commitment was the government’s National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS) (2016-2021) which set out ambitious policies to protect the UK in cyberspace, supported by the National Cyber Security Programme which included £1.9 billion of transformative investment to provide the UK with the next generation of cyber security. [footnote 2]

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) was responsible for the ‘Develop’ strand in the National Cyber Security Strategy 2016-2021, and worked with partners across government and industry to develop policy for this pipeline. As part of the Strategy, DCMS undertook an ambitious programme of interventions to help grow the UK’s cyber security sector and ecosystem. This included two cyber innovation centres in London and Cheltenham; a programme to support cyber security clusters in spurring economic growth and prosperity across the regions and nations of the UK; a programme to support academics to convert their research into businesses; a series of bootcamps for cyber SMEs, and a scale-up programme to showcase and support the best of the UK’s cyber businesses.

The cyber innovation centre in London is called LORCA (London Office for Rapid Cybersecurity Advancement) and it is a joint collaboration between Plexal, the Centre for Secure Information Technologies at Queen’s University Belfast, and Deloitte.

LORCA offered a bespoke package of support for successful cohort companies to scale and grow cyber solutions. Support included dedicated office space, access to technical and entrepreneurial expertise as well as events, such as LORCA Live and LORCA Challenges, to support connections with finance and industry experts. Over four years LORCA was tasked with:

- Stimulating the growth of at least 72 companies

- Growing up to 500 jobs

- Securing £40 million in investment

- Getting solutions to market more quickly

1.2 Overview of evaluation objectives and methods

Evaluation objectives

The specification for this evaluation stated that DCMS required a comprehensive evaluation of LORCA from its inception in 2018 to March 2022 to measure the impact of the programme and to generate learning to help develop future interventions. [footnote 3]

RSM UK Consulting LLP was appointed by DCMS in March 2022 to undertake the evaluation of the LORCA Programme [footnote 4] and has conducted both an impact and process evaluation with the following aims.

-

To determine how the LORCA Programme has performed over the last four years, and if the programme has met its objectives and policy goals

-

To clarify if the programme has produced benefits other than those outlined in the original business case, including benefits in relation to diversity, reputation and socioeconomic benefits

-

To help DCMS understand the impact of the programme and issues related to government intervention to help grow the cyber security ecosystem and any policy considerations around this

-

To explore whether the same level of benefits would have been achieved without government intervention.

This evaluation addresses the complete timeline of the LORCA project, detailing the performance and impact of the project since its inception in 2018 when the Centre was established through to March 2022, with a particular focus on:

-

the bespoke support LORCA offered through providing space, arranging events, such as the annual LORCA Live conference and networking opportunities, and fostering collaboration

-

the LORCA Ignite programme which ran between April 2021 and March 2022 and the extent to which it has supported the scaling growth of six of the most promising companies from within the LORCA graduate community

-

the three challenge-led programmes organised by LORCA and assessing the extent to which the approach adopted has encouraged start-ups and industry to co-create new solutions that specifically address these challenges.

The full list of Evaluation Questions can be found in Appendix A.

Method

Our approach was based on three key elements:

- A theory-based evaluation using Theory of Change supported by Contribution Analysis

- Comparing KPIs for participants against a counterfactual group of firms. A preferred approach would have been a counterfactual based on DiD modelling to compare outcomes between non-participants and participants; however, due to the lack of data this approach was not statistically viable.

- A rigorous analytical framework to allow the evidence to be triangulated and systematised using a Realist Evaluation approach that identifies what worked, for whom, in what contexts and why.

The evaluation methodology was agreed with DCMS and included the following:

- Rapid Evidence Assessment: We conducted a rapid review of the literature on other cyber security accelerators to inform the evaluation about the types of variables that should be considered in assessing the success of such interventions. This Rapid Evidence Assessment can be found in Appendix B with references in Appendix C.

- Theory of Change Workshop: We conducted a workshop with DCMS staff involved in the design and management of the programme to refine the Theory of Change. The original Theory of Change was quite underdeveloped, so we used the workshop to get a better sense of how LORCA fitted into the cyber ecosystem and what some of the wider outcomes and impacts were intended.

- Mapping the Cyber Security Ecosystem: After reviewing the context in which LORCA was developed, and the business environment within which it operated, we explored how the current cyber ecosystem evolved. This was extremely useful in helping us make recommendations about which elements of LORCA should continue or not be given the establishment of other, newer programmes.

- Analysis of Programme Monitoring Information and Impact Data: We analysed data from direct beneficiaries of LORCA, including information about (a) growth of companies, (b) jobs secured, and (c) investments, to assess the cohort companies’ growth relative to average UK cyber security market growth.

- Stakeholder Interviews: We completed 22 interviews with strategic stakeholders and ran an online workshop with programme beneficiaries in May 2022 to explore perceptions of how well LORCA met its core aims and objectives; suggestions for improvement, and recommendations for the future given ongoing changes in the cyber security market.

- Online Surveys of Innovators: We completed three different online surveys with (a) all five cohorts of LORCA with a separate section for participants in LORCA Ignite; (b) participants from the three LORCA Challenges and (c) a counterfactual group of companies matched to the successful LORCA cohort companies. Response rates in all surveys were low, notwithstanding the challenges around asking businesses to take part in surveys generally. We have attributed the lower than usual response rate to the sensitive and confidential nature of the cyber security sector and the questions we were asking about growth and investment. Whilst we reassured respondents about the GDPR process we would use in collecting and using their data, disclosing financial information and information about equity or, more generally, investment raised by the surveyed companies might have been too sensitive for them to share.

- Counterfactual: We analysed the impact of LORCA by comparing participating companies to a matched group of similar firms based upon certain KPIs such as equity transactions, number of employees, and turnover. Moreover, further filtering was carried out in order to ensure that the counterfactual sample matched the treated firms that participated in LORCA and to obtain a like-for-like comparisons by restricting for geographic location, turnover, and investment Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code, and other observable characteristics of the companies participating in LORCA. We used the Beauhurst business database in order to retrieve this sample of counterfactual firms.

2. Programme overview

2.1 Introduction

This section outlines the strategic context within which LORCA operates, the rationale for the LORCA programme, how it is delivered and funded, and the extent to which delivery has changed over time since 2018.

2.2 Strategic context

Cyber strategy

LORCA was set up in 2018 to act as a focal point for innovators and cyber security start-up companies in the early stage of their development, as they strove to develop ideas and concepts in collaboration with industry, leading ultimately to the creation of new products and solutions with potential end customers in mind.

The original intention was that LORCA would provide a unique environment where talent, creativity, entrepreneurship, and innovation could flourish. The centre in London would provide an environment in which cyber security start-ups and companies were supported to develop products and solutions in collaboration with industry partners. To support that endeavour, start-ups were provided with access to high-quality support relative to their needs through a holistic and tailored approach

To that end, LORCA was situated within a landscape of core and supporting strategies delivered by DCMS as part of the wider National Cyber Security Strategy 2016-2021. LORCA sits within the ‘Develop’ aim of this strategy in order to:

- improve the UK’s ability to defend and respond to cyber security incidents

- increase the UK’s ability to deter cyber criminals

- develop the pool of cyber security talent in the nation and increase innovation.

The National Cyber Security Strategy recognises that cyber security is also relevant to the following UK strategies:

- Net Zero Strategy: by promoting innovation in a space that has the potential to be low-carbon and build towards the 2050 net zero target issued by the government and delivered by the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy. The importance of this transition is shown by the government’s commitment of £5.8 billion since the launch of the Ten Point Plan in November 2020 [footnote 5]

- National Data Strategy: ensuring the systems which are used are secure and allowing the four key pillars [footnote 6] of the strategy to be properly addressed. The cyber security industry is crucial to this, with it being able to contribute to the improvement of data quality and availability, data processing skills, and ensuring that the data is responsibly sourced. The programme, delivered by DCMS with support from key institutions including the University of Cambridge and government departments such as the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy, will clearly be positively influenced by a strong UK cyber security sector

- Innovation Strategy: cyber security is key for economic development, and new technologies have an important role. Examples include the Digital Security by Design challenge fund and Security of Digital Technologies at the Periphery (SDTaP) programmes [footnote 7] that will act as key contributors to the UK’s target of becoming a global hub for innovation by 2035 [footnote 8]. Both seek to ensure that cyber spaces are safe, and problems are addressed through academia and industry.

All of the issues that form core parts of these strategies, whilst not directly linked to LORCA in terms of explicit KPIs, had a bearing on how LORCA delivered its programme.

Cyber security context

The UK cyber security industry is growing rapidly. DCMS recorded over 1,800 cyber security firms in the UK in their Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis Report (2022), [footnote 9] which reported double-digit growth in several key business performance indicators. An example of this is the sector’s revenue, which has increased to more than £10 billion for the first time (a 14% growth on the number identified in last year’s Sector Analysis Study [footnote 10]. In addition, the 2022 report highlighted that the sector has added over 6,000 jobs in the past year, with this representing a 13% growth to 52,700 full time equivalents working in cyber security related roles within the industry.

These numbers illustrate the considerable size of the industry and also its potential for further growth, highlighting the significant potential of the industry. The UK is also a global leader in cyber security research, with 19 academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research, four Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC-NCSC) Research Institutes, four Centres for Doctoral Training, the Centre for Security Information Technologies (CSIT) and the PETRAS National Centre of Excellence for Internet of Things Systems Cybersecurity. [footnote 11]

Investments in cyber security start-ups are also increasing. Over £821 million was raised in 2020 by dedicated cyber security firms across 73 deals, more than twice what was raised in 2019. [footnote 12] The sector has a critical role in responding to emerging cyber threats and challenges, and in the rapid proliferation of connectable products. However, research in 2020 by the University of Bristol, Imperial College London and the University of Surrey, found that significant long-term investments in other nations, especially the USA, France and Germany, are leading to the development of large clusters of research excellence. [footnote 13] Consequently, based on 2012-2019 levels of investment, the UK is at risk of not only a brain drain, but also endangering its position as a leader in cyber security research and innovation.

According to this research, UK investment in cyber security research falls significantly behind major competitors in absolute terms, and particularly as a percentage of GDP [footnote 14]. Furthermore, said competitors are ahead of the UK regarding their ability to accelerate research commercialisation in order to support innovators to scale-up their businesses. This is done through the provision of a network of partners, investors and corporates providing contacts, information, and capital. Overseas cyber hubs in the US and Israel excel in this area and the UK is facing significant competition despite its strong cyber security industry.

The challenges within the sector and the innovation landscape in the UK include:

- investment being skewed towards larger companies, preventing start-ups and SMEs receiving necessary funding [footnote 15]

- commercialising academic research into cyber security is difficult and there are barriers related to funding, ability to dedicate time to market research and validation, and the need to balance teaching, research, and commercial activity [footnote 16]

- the regional divide in the cyber security sector (33% of registered firms are in London, with only 3% in Wales) [footnote 17]

- half of businesses reported cyber security skills gaps at a basic level in 2021 [footnote 18]

- a lack of diversity in the sector: 22% of the workforce is female (compared to 30% across the digital sectors as a whole). However, ethnic minorities make up 25% of the cyber security sector workforce, which is higher than the 15% of people from ethnic minorities represented across all digital sectors [footnote 19]

- due to Brexit, the UK no longer has access to EU cyber security funding introduced as a priority for the 2021-2027 spending cycle. These programmes include Digital Europe and Horizon Europe, with significant funding. [footnote 20]

Although many of these challenges are general in nature, it is important to recognise how LORCA specifically interacts with some of them. One example is the issue of skewed investment towards larger companies. As highlighted in the LORCA Report 2020, there is a growing issue with investment being heavily weighted in favour of more mature companies. [footnote 21] This could possibly pose a barrier to new cyber security SMEs and start-ups, preventing them from growing or even from forming.

LORCA sought to address this problem through its development of accelerator programmes, providing support for these smaller companies to develop their entrepreneurial skills, their connections within the industry, and their ability to capture funding from investors in order to ensure a higher number reach stability and maturity. LORCA also recognised the issue of a separation between academia, investors and industry support and made collaboration one of its primary goals. Key examples of LORCA activities are listed below:

- Included academics from key institutions within the cyber security space to act in a programme delivery, mentoring and support capacity for participants

- Promoted interaction between investors and participants, as well as other delivery partners, through workshops and networking events

- Included representatives from industry to aid in the delivery and support of the programme and its participants.

COVID-19, on the other hand, was not identified as a challenge to the cyber security industry, according to investors that contributed to the Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis 2022. Most investors believed the pandemic had little or no impact on the sector, and in fact could be said to present a new opportunity for the sector that otherwise would not have been available, by increasing demand for remote working and fostering public awareness of potential secure technology solutions.

2.3. Market context

Growing number of cyber security firms in the UK

As outlined above, the sector is growing with small-sized (24%) [footnote 22] and micro-sized firms (57%) [footnote 23] making up the majority of the registered companies within the cyber security sector. The remainder of the cyber security firms comprised either medium or large-sized firms (18%). [footnote 24] This compares to just about 4% of all businesses across the whole of the UK that were medium or large-sized firms, revealing that businesses in cyber security sectors had a relatively higher proportion of scaling operators. [footnote 25]

Although the total number of cyber security firms increased in 2021, around 6% of the firms were reported to have either dissolved, were under administration, liquidised, or were no longer active. [footnote 26] This is higher than the 5% that was reported the year before, potentially indicating the challenges that some cyber businesses faced over the last 12-months due to the pandemic. [footnote 27]

The number of cyber professionals continues to grow but falls short of demand

The number of Full-Time Equivalent employees (FTEs) also grew from 2020 to 2021, increasing by 13% from 46,673 to 52,727. [footnote 28]In the previous year, employment grew by 9%, showing the sector continued to attract new entrants. [footnote 29]

Despite the overall increase in the cyber security workforce, there exists a shortage of cyber security professionals in the sector overall. [footnote 30] A recent study [footnote 31], for instance, shows that approximately 697,000 businesses (around 51% of 947 surveyed business samples) incurred a basic cyber skill gap [footnote 32], representing the lack of qualified professionals who could carry out the basic level of tasks listed in the government-recognised Cyber Essentials scheme. [footnote 33]

Around 451,000 businesses (33%) have reported that they were affected by a more advanced skills gap, which commonly involved technical skills such as penetration testing, forensic analysis, and security architecture. [footnote 34]

Deal value continued to rise in 2021 despite pandemic pressures

In 2021, the cyber sector saw the number of investment deals decline to 108 from 139 the previous year. [footnote 35] The pandemic may have been a contributing factor to this fall with caution spreading throughout financial markets. However, qualitative investor responses in the Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis 2022 highlighted that investors were likely becoming more selective. [footnote 36] Maturity was becoming increasingly important to investors as firms that were more experienced were favoured in addition to teams underlying cyber expertise. The focus for investors also turned towards innovative and growth areas such as cloud computing, smart cities or internet-based firms. Some investors felt other areas in cyber were already crowded markets and required de-risking through government support. This is echoed through an increase in the total value of deals, from just over £0.8 billion in 2020 up to over £1.4 billion in 2021. The value per each investment deal was higher on average, with £9.4 million per deal in 2021 compared to £5.9 million in 2020. [footnote 37] The investment environment within the cyber security sector also showed signs of gradual maturity and upscaling as cyber firms were successfully enticing more investors who have higher capacity for funding. [footnote 38] Thirty-five investors stated they were able to offer more than £25 million worth of funding by 2021, compared to only twenty-four investors from the 2019 - 2020 period. [footnote 39]

2.4 Delivery context

Programme rationale

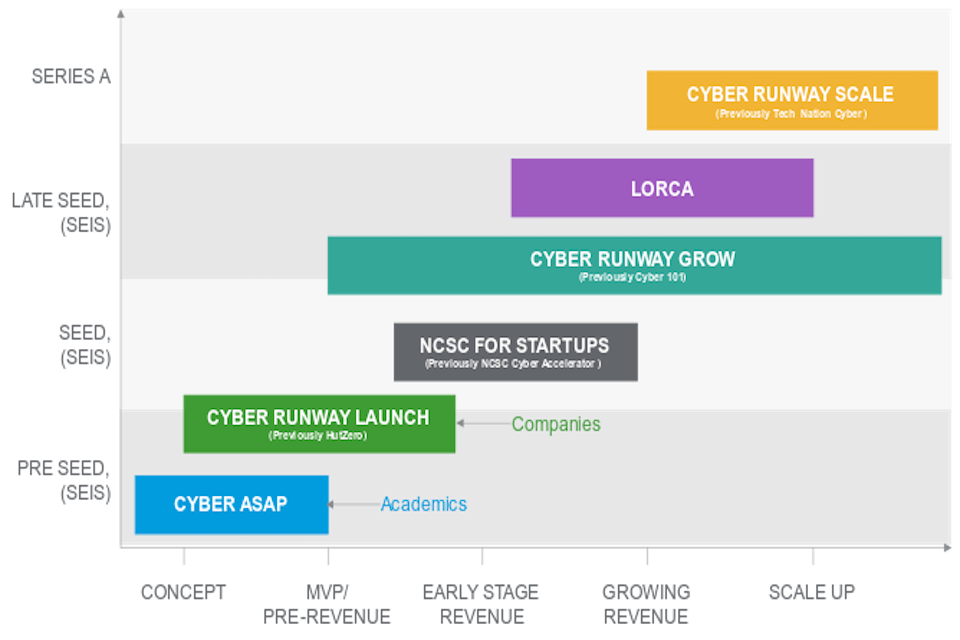

LORCA builds on the work of programmes such as Cyber ASAP, HutZero, and NCSC Accelerator. These programmes address the formative stages of start-up and SME development, supporting companies in the development of initial understanding of value propositions, proof of concept and the attraction of seed and pre-seed capital.

LORCA has also been used to inform programmes such as Cyber Runway Grow and Scale. LORCA differs from Cyber Runway Grow and Scale, with Cyber Runway Grow helping start-ups and SMEs to establish sound business foundations and commercialise their ideas and Cyber Runway Scale focusing on removing barriers to national and international growth once the company has developed. Therefore, LORCA overlaps and runs alongside both of these stages of development, with the programme rationale section below providing detail on how it does this and the results of this process thus far.

Figure 1: DCMS Growth and Innovation Ecosystem for Cyber Security

The rationale behind LORCA was to support collaborations between product developers and users by offering support and business mentoring to SMEs and start-ups in order to avoid common circumstances that can often lead to market failure within the cyber security industry. At the time LORCA was established, these market failure-inducing circumstances included:

- information asymmetries

- failures in financing, commercial and entrepreneurial expertise

- access to market, technical and legal advice

- the need for often unrealistic time and financial resources to develop a strong knowledge base.

Funded activities and contract variations

LORCA was awarded an initial contract to run between 2018 and 2021. However, the programme was extended by one year to March 2022. Plexal and the LORCA delivery team intended to use their DCMS funding across the timeline agreed in the initial contract, incorporating individual costs from these areas:

- Programme governance

- Rental/leasing costs

- Training and mentoring costs

- Business advisory support

- Marketing

- Programme outreach

- Monitoring

- Development of programme sustainability

- Cohort recruitment.

LORCA delivered on budget for each of the four years the programme took place. The granting of the extension and the additional costs were due to the addition of several contract variations and an extension of the original programme.

In the first variation in funding received from the original contract, Plexal was asked to carry out research to provide DCMS with evidence regarding the underlying data that drives the cyber security sector and internet-based SMEs, which was then fed into initiatives across the National Cyber Security Programme.

DCMS granted Plexal additional funds in the 2020-2021 Financial Year, due to the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. Plexal requested this extra funding to recover expenses incurred when organising the LORCA Live 2020 event, which was cancelled.

DCMS and Plexal extended their contract to 31st March 2022, a year longer than originally anticipated to allow for the engagement of six more companies in the programme LORCA Ignite.

During this extra year, Plexal also received additional funding to develop a third industry-led security challenge based on prior research exploring and documenting 5G security threats. This was carried out to:

- Explore and resolve critical gaps identified in the 5G Security Threat Landscape analysis

- Test the output in a real-world scenario, demonstrating to the UK 5G ecosystem that the output meets the objectives of supporting regionalisation and enabling resilience by tackling critical security challenges in 5G networks.

2.5 Summary

In summary, this section provides detail around the context within which the UK’s cyber security industry operates in order to enhance understanding around the key findings presented in this report. In order to do this, the UK’s position as a global leader in the cyber security space was discussed, and also the core challenges and barriers being faced by the industry as a whole. This facilitates understanding how LORCA was designed to interact with, and counterbalance, these threats and challenges faced by the industry alongside other programmes within the national cyber strategy. In addition, a closer assessment of the LORCA programme itself was carried out, describing programme funding in order to provide an overall context for both the wider cyber security space and LORCA itself.

3. Methodology

3.1. Approach

The Invitation to Tender for the LORCA evaluation required the production of a high-level Theory of Change mapping the inputs and activities that lead to programme goals [footnote 40]. At RSM, our general approach is to situate all evaluative thinking within a Theory of Change. This provides stakeholders with a clear, concise, communicable framework within which to frame the evaluation. Our model looked at:

- Context, Rationale and Assumptions: Why LORCA was needed at that time

- Objectives: What the programme intended to achieve in terms of outcomes

- Inputs and Activities: The ways and means by which the programme achieved its objectives

- Outputs, Outcomes and Impacts: Measurable changes that the programme achieved for those participating in terms of growth in relation to jobs and investment.

The rationale is that if the links between inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts can be confirmed, and achievement measured by reference to agreed indicators for each link in the chain, then there is a basis for reaching conclusions on the performance delivered by the programme. Where it is found that there are weaknesses in some linkages within the Theory of Change, then this has an effect on the strength of the conclusions that can be reached. This approach also makes it easier to measure success.

This chapter sets out:

- our approach to producing the Theory of Change

- the research that was carried out to provide evidence for the specified outputs, outcomes and impacts using primary and secondary research.

The section on research methods covers both the process and impact evaluations, as these both drew heavily upon primary research for evidence.

3.2 LORCA Theory of Change

The original Theory of Change for LORCA, as provided by DCMS, is shown in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2: Original LORCA Theory of Change

Based on our review of the documentation and after discussion at a workshop with key DCMS stakeholders a revised Theory of Change was employed to guide the evaluation. There were two major classes of revision:

- The revised Theory of Change explicitly distinguishes between short-, medium-, and long-term effects of the programme

- The revised Theory of Change incorporates many more quantitative indicators drawn from management information on the programme and secondary sources such as the regularly updated DCMS Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis.

Figure 3 shows how the new Theory of Change encapsulates the way in which LORCA fits within the overall change being brought about in the cyber ecosystem. The outputs, outcomes, and impacts were built into our evaluation plan and, where information was not available from secondary sources, questions investigating these were built into our surveys and interviews. Whilst we are unable to report on every single outcome and impact due to the lack of available information, this Theory of Change lens informed all aspects of the evaluation.

Figure 3: Revised LORCA Theory of Change

3.3. Primary data collection

Interviews

We conducted 22 interviews with people from a variety of stakeholder groups related to LORCA and the cyber security ecosystem. The groups to which they belonged were as follows:

- DCMS Policy Staff

- LORCA Programme Staff

- Wider Stakeholders

- Industry/Enterprise Members

- Investors

- Challenge Cohort Problem Owners

During these interviews, a range of key topics were identified as being relevant to all discussions, and a list of questions were developed for each group including:

- Whether delivery of the programme was successful

- What elements of delivery worked, which worked well, and less well, for participants

- How suited the programme’s activities were to the priorities of participants

- What lessons there are to be learned from the delivery methods used

- How external factors influenced the programme

- How the programme could be improved to become more effective

- Whether the programme contributed or led to economic displacement

- The impact of LORCA on participants (investment, business wins, international development).

Surveys

As well as stakeholder interviews, we developed surveys to further our understanding of the LORCA cohort and LORCA challenge experience for the participants. The surveys were aimed at LORCA participants who successfully applied to the programme. They focused on identifying what has worked well and less well in the implementation and delivery of the programme, as well as trying to understand what has motivated firms to apply for the programme and what outcomes have been achieved. The surveys were developed on the SmartSurvey platform, and were categorised as follows:

- LORCA cohort participant survey

- LORCA challenge participant survey.

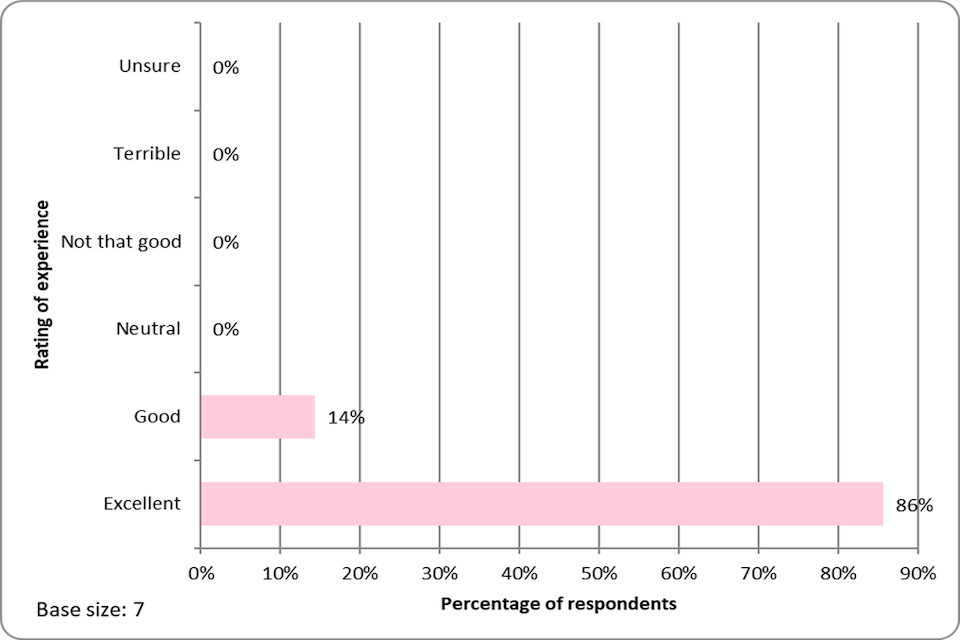

The LORCA cohort participant survey received a total of 24 complete responses out of the 72 LORCA cohort participants, with the challenge participant survey having 7 responses in total. Each survey ran from 12 April 2022 to 19 May 2022 and, though sent to all relevant parties, was naturally limited in number of responses by how many of those people were willing to complete them fully or to a meaningful degree. This is exemplified by the partial response numbers for our surveys, with the cohort participant survey receiving 13 partial responses, and the challenge survey receiving one partial response. We did not include partial responses as they contained very little relevant information. Response rates are always a challenge with a survey-based approach, but the insight we have gained from these surveys has developed our understanding of the LORCA programme and those who participated in it.

The LORCA cohort participant survey focused on a range of issues related to prior participants, so as to develop our understanding of who they are/what type of company they belong to, their company’s positions before and after LORCA, and their overall view of the programme and its activities. The LORCA challenge participant survey centred on assessing how impactful they have been, as well as what type of company was involved in the process and how their experience could have been improved.

Future Focus workshop

We also conducted a Future Focus workshop over Microsoft Teams with former LORCA cohort participants, in order to develop an understanding of what LORCA did well, and less well, from their perspective. These findings are used in both the process and impact evaluation. In addition to this, we sought to develop an understanding of how LORCA could develop in the future to improve the experience of participants and increase LORCA’s (and similar cyber security accelerators’) positive impact on the ecosystem as a whole. The workshop format was relatively informal in structure, providing the former participants with a platform for open discussion of the LORCA programme. The discussion guide for the workshop was adapted from the topic guides for participant interviews and covered both process and impact evaluation questions.

Analysis

There were several sources used to understand the LORCA programme and the impact it had, some of which included:

- Analysis of monitoring data for each cohort

- Analysis of secondary data: The source used was the Beauhurst database which tracks the performance of 82,463 [footnote 41] growth firms in the UK, where, according to the platform, 1,424 firms operate in the digital security sector. The KPI we used for our assessment was equity fundraising, which was selected as a precursor for business investment; as early-stage firms are more likely to show any potential impacts from the LORCA programme through this metric, given that finance is usually directed towards R&D and business development. The LORCA programme was due to end with the last cohort in July 2021, hence not enough time has passed for firms to incorporate learnings through to changes in revenue. Therefore, the lag in revenue realisations would likely distort any potential impacts. In subsequent evaluations, where a sufficient amount of time has passed following the completion of the LORCA programme, revenue would be the ideal KPI to establish potential impacts. See section 5.3 on secondary data analysis for further details.

- Qualitative framework analysis: Applying a thematic framework to the interview analysis; we coded each transcript with emerging themes to decide which are prevalent or only occur rarely; the combinations in which themes appear; the contexts in which they appear and the strength of perception about certain issues.

- Quantitative analysis: This included descriptive statistics to compare outcomes in a group of similar companies matched for key information such as the average size of firms, their revenue and investment growth. Beauhurst’s platform, which supports a filtering system that allowed us to produce a counterfactual group of firms similar to the treatment group of firms, enabled us to conduct a matching exercise and a like-for-like comparison. The detail of this exercise can be found in Section 5.

The analysis has been shared with DCMS throughout the evaluation, in accordance with the evaluation plan. This report summarises our analysis, conclusions, and recommendations about LORCA.

3.4 Evaluation challenges and limitations

The team at RSM were faced with a number of challenges during this evaluation. These have shaped, and to some degree limited, the evaluation process and its findings. These included:

- Willingness to cooperate and low response rates to surveys. The engagement of LORCA firms with our surveys was lower than expected. Despite two reminder emails issued on our behalf by Plexal, the response rates remained low.

- The nature of the sector and the sensitive nature of some of the questions we were asking perhaps contributed to the low survey response rate.

- One limitation we noted from our workshop was the lack of diversity in the ages of participants. This was remarked upon by some of the workshop participants, who suggested that younger LORCA cohort participants might have different views on key topics. However, we were once again limited by who was able and willing to attend.

- It was difficult to establish a like-for-like counterfactual group of firms to undertake the DiD analysis to evaluate the impact of the LORCA programme. Section 5.3 on secondary data analysis provides further detail

- Good data about impact is typically collected over a long period of time. For LORCA, quantifying impacts is difficult as very little time has passed since participants completed the programme, and COVID-19 may have impacted in ways that we are not yet aware of; therefore, being able to report on the causal relationships between DCMS funding and impacts is difficult.

- The data used to evaluate LORCA’s performance consisted primarily of the monitoring information provided through LORCA to DCMS.

4 Key findings: programme delivery and performance

4.1 Overview

This section assesses the performance of LORCA and how it was delivered from 2018 until the programme ceased in March 2022. It addresses the following evaluation questions:

- Was the programme delivered as intended?

- What worked well, or less well, for whom and why?

- Were there any unexpected or unintended issues in the delivery of the intervention?

- What can be learned from the delivery methods used?

- How did external factors influence the delivery and functioning of the programme?

- How can the existing programme be improved to become more effective?

- To what extent were the activities suited to the priorities of the participants?

We summarise what LORCA has achieved to date and present findings in relation to the above questions.

4.2 Programme delivery

LORCA represented a shift towards the introduction of regional cyber security hubs that would aid in the acceleration and growth of cyber security companies, whilst also providing space for increased innovation and collaboration. The programme was delivered by Plexal (offering a common workspace and support network containing commercial and technology validation clinics, access to investors, mentoring opportunities and national as well as international support and events), in collaboration with Deloitte (access to virtual validation testing) and the Centre for Secure Information Technologies (academic and engineering support), as well as other partners (AHL Connect, Outfly, Informed Funding and InfoSec People among others to provide ongoing support), with members also benefiting from international trade delegations, mentoring and workshops on several key aspects of the industry.

Key outcomes expected

Over the period of 2018 to 2021 LORCA was expected to support 72 companies in the scaling process in order to create up to 500 jobs and secure £40 million investment. By January 2022, it had supported five cohorts, provided a platform for further investment, introduction to new markets, and increased talent retention.

Each cohort focused on specific issues identified by a panel of industry leaders, addressing topics such as supply chain security. This allowed for different problems to be addressed by each cohort, with programme partners such as Dell Technologies referencing the importance of these cohorts in developing the UK’s ability to adapt to the array of cyber threats currently present [footnote 42].

New elements of the programme were introduced in response to changing industry needs. For example, the Challenges were introduced to the programme to act as a problem-focused initiative aimed at developing real-world solutions to cyber issues and strengthening ties between LORCA participants and the wider industry. To date, three challenges have been completed and have assessed issues related to three key industry areas:

- Telecoms Diversification

- Connected and Autonomous Vehicles

- Network Vulnerabilities.

In addition, LORCA Ignite was introduced in 2021, inducting six of LORCA’s most successful scaleups into an intensive six-month programme. LORCA Ignite aimed to build on the accelerators provided within the central LORCA programme, offering an increased level of support to those selected in the form of commercial and technology validation clinics; access to investors and mentoring services, and access to national and global networks.

Please note that just because these impacts occurred since the start of the LORCA support, it does not necessarily follow that they arose because of the LORCA support, or that the companies would not have found a different way to achieve these impacts to some extent in the absence of LORCA. Section 4.9 on “economic indicators” and “additionality” at the end of this chapter discusses this further.

4.3 Roles and responsibilities

The information below provides further detail on roles and responsibilities of the main organisations involved with LORCA:

Table 3: Roles and responsibilities of LORCA organisations

| Stakeholder | Role |

| DCMS | Funder and management oversight of the LORCA programme |

| Core delivery team | |

| Plexal | • Programme management • Provide core programme team • Space and facilities provision • Marketing and start-up recruitment • Industry engagement • Government engagement • Provision of start-up professional services • International outreach • Annual cyber summit (LORCA LIVE) and Challenges |

| Deloitte | • Programme management • Industry engagement • Government engagement • Cyber SME and technical advice • Business mentoring • International outreach • Annual cyber summit • Remote lab access |

| Centre for Secure Information Technologies | • Academic engagement • Government engagement • Cyber SME and technical advice • International outreach • Annual cyber summit • Remote lab access |

| Partnerships with established bodies | |

| Industry partners | Included Lloyds Banking Group, Kudelski Security, Global Cyber Alliance, KX, Amazon Web Services, SOSA, Splunk, and DELL Technologies |

4.4 LORCA governance

The governance structure for the LORCA programme centred around an Executive Board at Plexal responsible for delivery. However, they were also assisted by an Advisory Board made up of industry stakeholders.

Executive board

The purpose of the Executive Board was to review management of the programme, oversee performance ensuring that LORCA goals, objectives and targets were met, and provide strategic guidance to LORCA. The Executive Board met each calendar month, ensuring that insights from key stakeholders, e.g. the Industrial Advisory Board (IAB), Finance Forum and Innovation Forums, informed the ongoing delivery and strategy for LORCA.

In general, the people we interviewed and surveyed in our analysis felt that the Executive Team had done a good job in terms of governance. This is particularly notable when discussing the LORCA management team, who were extremely well thought of by the majority of those interviewed and the efforts of the LORCA delivery team were also recognised in the survey responses.

We have greatly benefited from our involvement with LORCA over an extended period, and we also value the relationships we’ve built with the LORCA delivery team (including the delivery partners) over that time. Great to see Plexal and LORCA going from strength to strength over the past 3 years.

LORCA Cohort Survey Participant

DCMS had the vision early on, and the Director at Plexal was brilliant. What’s worked well in the delivery partnership has been the relationship and understanding that we are all in this together.

LORCA Programme Staff

LORCA Industrial Advisory Board

Plexal recognised it was essential to bring a degree of independence to the leadership and governance arrangements of LORCA and so they set up an Industrial Advisory Board (IAB). From the programme documentation reviewed, we established that the IAB met three times a year to advise on the direction and delivery of the Centre.

Other functions of the IAB included:

- receiving briefings on upcoming and existing cohorts

- identifying research results that are appropriate for rapid commercialisation

- highlighting shifts in technology, market demand or new business models

- advising on the content and emphasis of the Centre’s training activities

The small number of participants we interviewed on the issue positively spoke about the LORCA Advisory Board, saying the IAB provided the programme with an outlet to focus on where the ecosystem as a whole was moving, and how LORCA could best maintain relevance in an ever-changing environment. This fits with the recognised purpose of the advisory board, with its role being to focus more on the industry and LORCA’s direction of travel than the specific design and delivery elements of the programme.

The advisory board’s original purpose was not to micro-manage or act as an executive board, but rather to act as a sounding board and discuss the direction of the industry.

Wider Stakeholder

DCMS

The final element of governance that is important to recognise is the relationship between programme management and DCMS. As noted by a DCMS staff member, the maintenance of consistent contact between the two organisations was important. This allowed for feedback to be delivered effectively and ensured that the delivery teams were aware of what DCMS were expecting from the programme. Those who took part in stakeholder interviews believed that this relationship was managed successfully, with DCMS and programme staff members both recognising the consistency of meetings surrounding risk, programme management and KPI delivery. The quote below illustrates how a DCMS staff member made it clear from the outset what their expectations were:

“We engaged a lot with start-ups, using monthly meetings with LORCA management to develop information and feedback. Having these discussions meant that they knew we were expecting to see that there was value being created for participants.” – DCMS Staff

Application process

Demand for the first cohort was low, with 9 participants selected out of a total of 10 applications. However, as the LORCA programme became better known the number of applications for subsequent cohorts increased, and the percentage of companies that were selected fell accordingly.

| Cohort | Cohort Participants | Total Applications per Cohort | % Companies Selected |

| Cohort 1 | 9 | 10 | 90 |

| Cohort 2 | 11 | 23 | 48 |

| Cohort 3 | 15 | 43 | 35 |

| Cohort 4 | 20 | 79 | 25 |

| Cohort 5 | 17 | 55 | 31 |

For LORCA there were some eligibility requirements and applicants needed to be:

- A fast growth company with technology that matched the programme’s innovation themes

- Have generated revenue and/or raised capital

- Have a business relevant to cyber security

- Be a UK registered company.

Moreover, companies were also considered for LORCA based on their active market development strategies and desire for growth. Businesses that had already generated revenue were preferred over those that had just started looking for customers, as were businesses that were developing products to meet user-centric market requirements. Similarly, companies that promoted commercial opportunities with a clear plan for engaging customers were more likely to be accepted onto the programme than those that did not.

The application process consisted of the following steps:

- Application form

- Scoring and Shortlisting

- Evaluation Day (Live pitching to a panel of evaluators)

- Final Scoring and Selection.

Our review of the criteria used by LORCA to evaluate firms applying to join LORCA concludes that the processes were fair and transparent, and our stakeholder interviews confirmed that the decision-making processes were robust and transparent. Some of the criteria used to make decisions included impact, innovation, sustainability, capacity, and programme need and fit. We do not have sufficient information to draw any conclusions about the efficiency or effectiveness of the application process, for example, how quickly applications were reviewed, but it may be something that DCMS might want to consider monitoring in the future.

4.5 Support provided

As part of the LORCA programme, there was an intensive six-month support period, followed by a less intensive six-month period. During the first six months, the programme generally consisted of the following components, which were tailored to meet the specific needs of each cohort company:

- One to one weekly support on cyber commercial and cyber technical support, marketing support, legal advice, investment-readiness and sales support

- Academic masterclasses

- Professional services masterclasses

- Access to the finance community (via a quarterly finance forum)

- Access to inward and one outward bound trade delegation

- One to one and group engagement with corporates and buyers

- A mentor, where demand and supply align

- Exhibiting space at LORCA Live and other LORCA-supported external conferences.

In the second six months of the programme there was a significant reduction in one-to-one support for cohort members, but free attendance to group sessions, as well as the use of the Plexal environment and desks, continued during that period. Given the approach that LORCA took to facilitating meetings and networks, and expecting that initial introductions could snowball into a whole range of other contacts, and coupled with a lack of mandatory reporting to capture every activity, there is not sufficient information to be able to report adequately of the extent of take-up of each individual aspect of support by company.

4.6. LORCA participants

Plexal captured monitoring information on participants at the beginning of the programme, at a 3-month and a 6-month interval, and at the end of the programme at 12 months. Job growth, investment growth, revenue, number of new contracts and Proof of Concepts, have been collected across all 5 cohorts for the 72 participating firms. The data was usually self-reported by participant companies, and independently cross-checked and validated by Plexal’s team by researching public datasets and desk-based research.

Table 4 below outlines the companies in each cohort that took part in the LORCA programme.

Table 4: LORCA cohorts

Cohort 1: 07/2018-07/2019 (9 companies): Aves Netsec, B-Secur Ltd, CyberOwl, Cybershield (Aquilai), Ioetec, ThinkCyber, Surevine, Trust Elevate, Zonefox

Cohort 2: 01/2019-01/2020 (11 companies): Ampliphae, Bob’s Business, Crypto Quantique, CyberSmart, CyNation, Distributed Management Systems, ObjectTech Group, OutThink, Privitar, RazorSecure, Xanadata

Cohort 3: 06/2019-06/2020 (15 companies): CounterCraft, CTO Technologies, D-RisQ, Elemendar, Hack the Box, Human Firewall, Messagenius, Panaseer, Quant Network, Salt DNA (Salt Communications), Security Alliance, Storage Made Easy, SwIDch, Threat Status, Uleska

Cohort 4: 01/2020-01/2021 (20 companies): Acreto, Anzen Technology Systems, Avnos, Contingent, Continuum Security (Irius Risk), Darkbeam, Heimdal Security, Kinnami, Keyless Technologies, L7 Defense, Orpheus, Osirium, Risk Ledger, ShieldIOT, SureCert, ThreatAware, ThunderCipher (Licel), Variti, VIVIDA, Westgate Cyber Security (Enclave Networks)

Cohort 5: 07/2020-07/2021 (17 companies): AdvSTAR, BlockAPT, BreachLock, CapsLock, ContextSpace, CyberHive (100 Percent IT), InsurTechnix, ITsMine, MIRACL, Nanotego, RedHunt Labs, The CyberFish Company, Truststamp, VerifiedVisitors (GleveVentures), VU Security, Zamna, ZeroGuard

LORCA IGNITE (6 companies): Ampliphae, Crypto Quantique, CyberOwl, CyberSmart, Risk Ledger, Salt Communications,

A fuller description of all companies that took part in LORCA is given in Appendix H.

LORCA participant background information

The information shared from Plexal about LORCA participating companies did not include information on the companies’ leadership structure or geographic location. So, in the absence of these data, we used Beauhurst to gather information about the characteristics of the participating companies in the programme. Beauhurst did not track data for all 72 participating companies in the programme since some of them are not based in the UK. Therefore, this analysis is based on a sample of 55 out of the total of 72 firms. [footnote 43] A separate analysis of the available information on the 17 international firms is provided at the end of section 5.3.

We analysed the following characteristics for each company:

- Directors and founders gender identity

- Company location

- Sector in which they operate

- Type of company and corporate structure.

Directors’ and founders’ gender identity

Monitoring information about the gender of the directors and founders of the sample of LORCA companies shows a significant weighting towards males. In our sample of 55 LORCA companies, 52% of the firms do not have any female directors and 69% do not have any female founder. Among 55 companies, only five (9%) have all of their directors identifying as female. There are three companies in which more than 50% of the founders are female, two of which have all female founders.

Company location

In our LORCA sample, more than half of companies (53%) are based in London. The second largest group of companies is based in the South East of England (16%), and the least represented regions are the East and South West of England, as well as Wales, each with one company (2%).

Sector code

Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Code 2007 identifies the industry in which Beauhurst’s sample of LORCA participants operates. SIC codes are used to classify business activities. The sample we are analysing falls into the following categories:

Table 5: SIC codes

| SIC Codes 2007 - Group | Sample of LORCA participating firms -frequency | % |

| NA | 1 | 2% |

| C - Manufacturing | 1 | 2% |

| J - Information and communication | 45 | 82% |

| K - Financial and insurance activities | 1 | 2% |

| M - Professional, scientific, and technical activities | 1 | 2% |

| N - Administrative and support service activities | 4 | 7% |

| P - Education | 2 | 4% |

It is evident from the table above that the bulk of our sample (82%) comes under the ‘information and communication’ category. This includes activities such as business and domestic software development as well as information technology consulting.

Type of company

In our sample from Beauhurst, almost all of the LORCA programme firms are private companies (98%), with one datapoint missing. In addition, 89% of companies in the sample, regardless of whether they are part of a wider group of companies or not, are the ultimate parent company and are not owned by mother companies.

4.7 Performance

The source used to evaluate LORCA’s performance consisted primarily of the monitoring information provided through LORCA to DCMS.

Performance against key performance indicators

The evaluation of LORCA against its KPIs for the period is based on data collected from the log frames provided by DCMS and LORCA and is presented in the form of tables, with each table analysing the relevant indicators, measurements, targets, and status of each of the five KPIs. These KPIs are:

-

LORCA delivers growth and support for high potential business up to 31 March 2022

-

LORCA addresses unmet real-world cyber security challenges

- LORCA supports the increased adoption of innovative cyber security technology across private and public sectors

- LORCA contributes to the overall UK cyber ecosystem supporting growth and diversity in the sector and is a convening force across cyber security community

- LORCA is sustained beyond March 2022.

Table 6: LORCA delivers growth and support for high potential business up to 31 March 2022

| Indicators | Indicative Measures | Targets | Evidence | Status |

| Project delivery milestones are being delivered on time, in budget and to the satisfaction of DCMS | Percentage of milestones delivered on time. Percentage of milestones delivered within budget forecast | 100% milestones delivered to time and budget agreed | Log frame reports | Delivered |

| The centre provisions are relevant to the needs of cohort participants | Qualitative and quantitative data is collected by a confidential cohort questionnaire | Average quantitative feedback score is greater than or equal to 7 (as decided by DCMS) and qualitative feedback is shared with DCMS as required | Monitored by DCMS. | Delivered |

| Cohort companies’ growth relative to average global and UK cyber security market growth | Revenue growth. Funding raised. Jobs increased. | Tracking of ongoing growth relative to average global cyber security market growth as measured by % growth increase | Log frame reports | Average revenue increase - 49%; Investment raised £2.1m (25% increase); 16 jobs created (9% increase)* |

Note: * These figures are reported verbatim from the log frame reports. The overall investment and jobs growth targets were exceeded (see paragraph under Table 10).

Source: LORCA Log Frame, March 2022

Table 7: LORCA addresses unmet real-world cyber security challenges

| Indicators | Indicative Measures | Target/s | Evidence | Status |

| Number of corporates participating in the Innovation Forum and /or providing mentors to programme and Centre activities | Number of different companies involved in mentoring and / or innovation forum / challenge-led activities / convened events | 10 Companies | Log frame reports | Delivered |

| Proportion of industry challenge list contributors working directly with the LORCA ecosystem to address specific challenges and needs | Number of problem-owners / challenge sponsors per challenge-led project | Minimum of 2 per challenge-led project | Challenge Reports | Delivered |

| Proportion of LORCA cohort and alumni members working on solutions directly aligned to unmet real-world security challenges. | Percentage of members selected who align with identified challenge areas | 90% | Monitored by DCMS. | Delivered |

Source: LORCA Log Frame, March 2022

Table 8: LORCA supports the increased adoption of innovative cyber security technology across private and public sectors

| Indicators | Indicative Measures | Target/s | Evidence | Status |

| Number of industry trials/proofs of concept secured through participation in LORCA | Percentage of members who develop / secure new PoC/ trials as a result of / or through the cohort programme;Number of new PoC/ trials in place as a result of / through cohort programme | 50% of members 5 new PoCs/trials | Monitored by DCMS. | Delivered |

| Number of business introductions secured during time as a LORCA member, or as a result of membership | Percentage of members who develop/secure new business contacts as a result of /or through the programme. Number of new business introductions made per company, per quarter | 80% of members 3 new business introductions | Monitored by DCMS. Evidence received. | Delivered |

| Number of introductions to government-related projects or opportunities as a result of being a LORCA cohort or alumni member | Percentage of members who are proactively introduced to cross-government initiatives such as NCSC, MoD, ACE etc.Number of introductions to major government suppliers/ primes as a result of being a LORCA member, per company | 30% of members 2 Introductions | Monitored by DCMS. Evidence received. | Delivered |

Source: LORCA Log Frame, March 2022

Table 9: LORCA contributes to the overall UK cyber ecosystem supporting growth and diversity in the sector and is a convening force across the cyber security community.

| Indicators | Indicative Measures | Target/s | Evidence | Status |

| Consistent engagement with the LORCA Cohort, Alumni and Ecosystem network | Huddles with the Cohort members; Number of targeted broadcast emails to Cohort and Alumni network per quarter; Number of monthly LORCA update emails to Ecosystem mailing list per quarter | 6 Huddles 9 targeted broadcast emails 3 monthly LORCA update emails | Log frame reports | Delivered |

| Numbers of non-Cohort members utilising the Centre or joining the LORCA ecosystem | Percentage of non-cohort members joining the Centre or LORCA ecosystem | 20% of total LORCA cohort and alumni number | Log frame reports | Delivered against a target of 14 members |

| Increasing gender and ethnic diversity across the LORCA network | Percentage of female-founders / female senior leaders within LORCA alumni and cohort community;Percentage of BAME founders / BAME senior leaders within LORCA alumni and cohort community;Number of virtual or physical events/ roundtables/ meetups delivered or supported with a focus on engaging underrepresented entrepreneurs within cyber security e.g., Women in Cyber, CyberFirst support etc | Ongoing measurement and reporting. Proactive encouragement for LORCA Cohort and Alumni members to embed increasing diversity into their company’s core values and talent strategy. 2 Events | No evidence received. | Verbal feedback that some progress was being made. An ongoing issue for the sector |

| Number of cluster, academic and international ecosystem partnerships | Number of partnerships through MoU in place | 10 Partnerships | Monitored by DCMS. | Delivered |

Source: LORCA Log Frame, March 2022

Table 10: LORCA is sustained beyond March 2022

| Indicators | Indicative Measures | Target/s | Evidence | Status |

| Lead generation activities to support future private-sector funding for LORCA | Number of meetings per month; Number of partnership leads generated; Number of convening events with private sector stakeholders | 5 meetings 2 partnerships1 convening event per quarter | No evidence received. | Delivered activities but no funding forthcoming |

| Partnership renewals | Percentage of LORCA partnerships renewed during 2021/22 | 90% | Monitored by DCMS. | Delivered |

| Volume of private funding for LORCA related activities | Income amounts from private sector sources | >300k by 6 months>500k by 12 months | Monitored by DCMS. | Delivered |

Source: LORCA Log Frame, March 2022

This analysis, drawn from the log frame report dated 28th March 2022 indicates how LORCA met most of its key performance indicators. The success of LORCA is showcased by the fact that the majority of KPI indicators were delivered or exceeded. In summary, a cumulative assessment of the LORCA programme (from 5 cohorts delivered over 3 years) finds that LORCA has surpassed its investment and job creation targets, with £210 million in investment raised (original target of £40 million) and 865 jobs created (original target of 500). [footnote 44]

Was the programme delivered as intended?

In order to answer this question, we utilised a range of sources, including interviews with stakeholders, workshops with former LORCA participants, and participant survey data so that we could provide a detailed and unbiased view of how the programme was delivered.

In interviews, we found that the LORCA programme staff spoke very positively around the issue of programme delivery, feeling that LORCA did meet all its objectives. Evidence of this has been present in this report, highlighted by the programme’s success in either meeting or surpassing job creation and revenue targets. However, it is important to note that analysis of both the delivery staff / those involved in the process and the views of participants is required to present an unbiased and balanced view of the programme. The quotes provided below demonstrate the survey participants’ positive view of programme delivery, with a clear focus being placed on the importance of bespoke training sessions and workshops that contributed to a general improvement of skills within the participant base. This is highlighted in participant and staff quotes provided, with these one-to-one mentoring sessions and workshops being regarded as the element of delivery that separated LORCA from other relevant cyber accelerators.

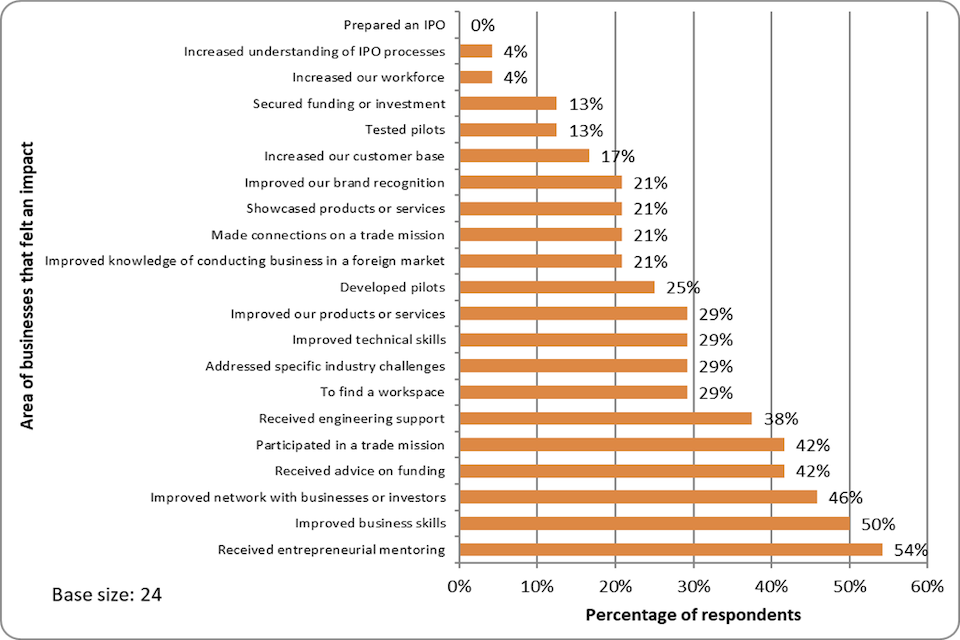

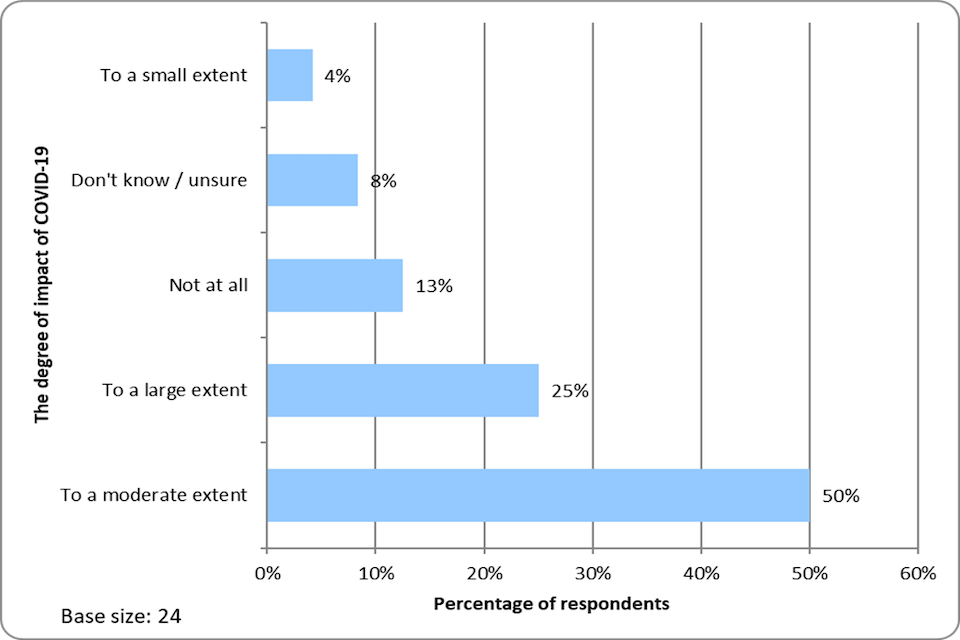

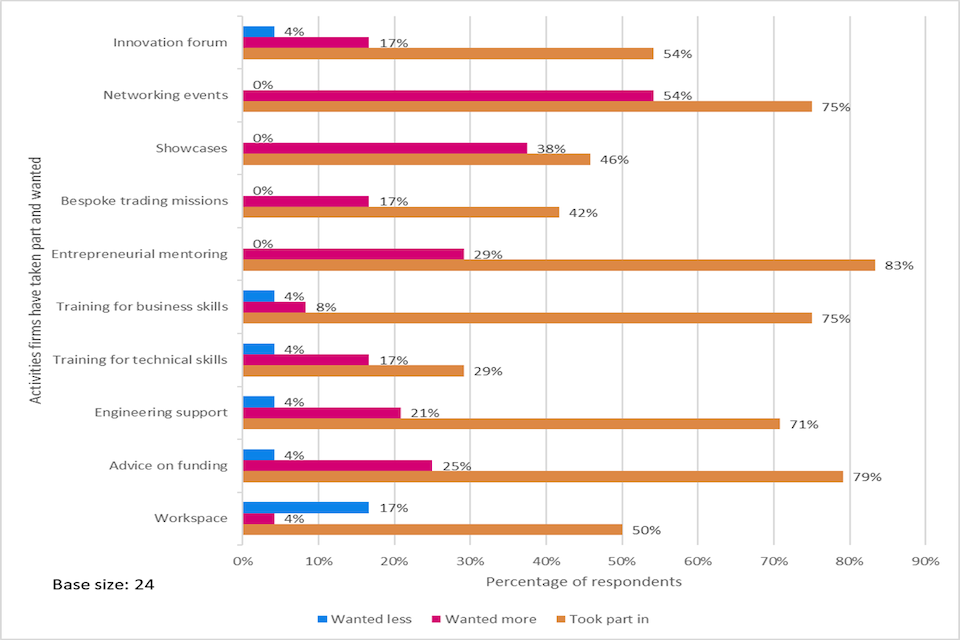

Figure 4 illustrates that 50% of those surveyed (i.e.,12 respondents) felt they had experienced business skill development as a result of LORCA. This is particularly notable when considering that, according to the percentages presented, only one other aspect of the programme received a higher proportion of the vote. This highlights the crucial role that business skills support played in a programme that both staff members and participants felt had been delivered successfully.

The mentoring sessions were extremely helpful because they helped us prepare for discussions with potential customers.

LORCA Cohort Survey Participant

The one-to-one support to LORCA participants from corporate partners, this was the best out of the couple accelerators we took part in.

LORCA Cohort Survey Participant

Figure 4: How participation in LORCA has impacted the cohorts

(percentage reporting an impact, multiple answers permitted)

In addition, it can be seen that the LORCA programme has supported the growth of the participant companies through the provision of a strong and active governance structure within the programme. Though Plexal was relatively new to the cyber security accelerator space, stakeholders consistently pointed to the importance of LORCA and DCMS leadership in the programme’s success. LORCA leadership was referenced multiple times when discussing the positive elements of the programme’s delivery, as highlighted both by quotes from programme staff below, but also by LORCA participants, with one participant highlighting their support for the level of organisation and the quality of key programme delivery teams.

I suppose what has worked well is the governance and the leadership. We have a good advisory board and brought together a good executive team.

LORCA Programme Staff

The organisation and the quality of the executive and support team. Excellent engagement, excellent mentors. Excellent introductions and opportunities.

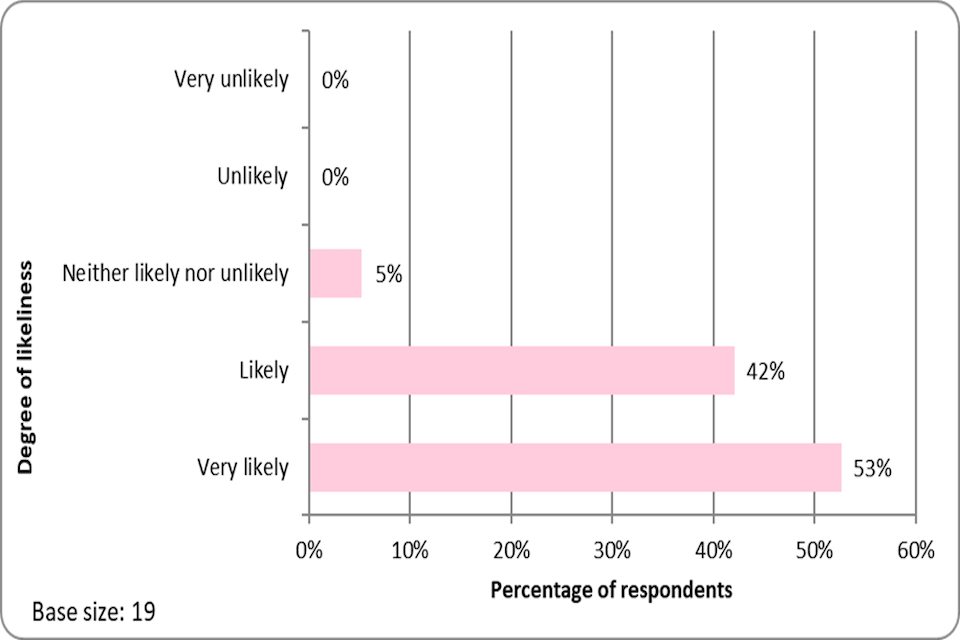

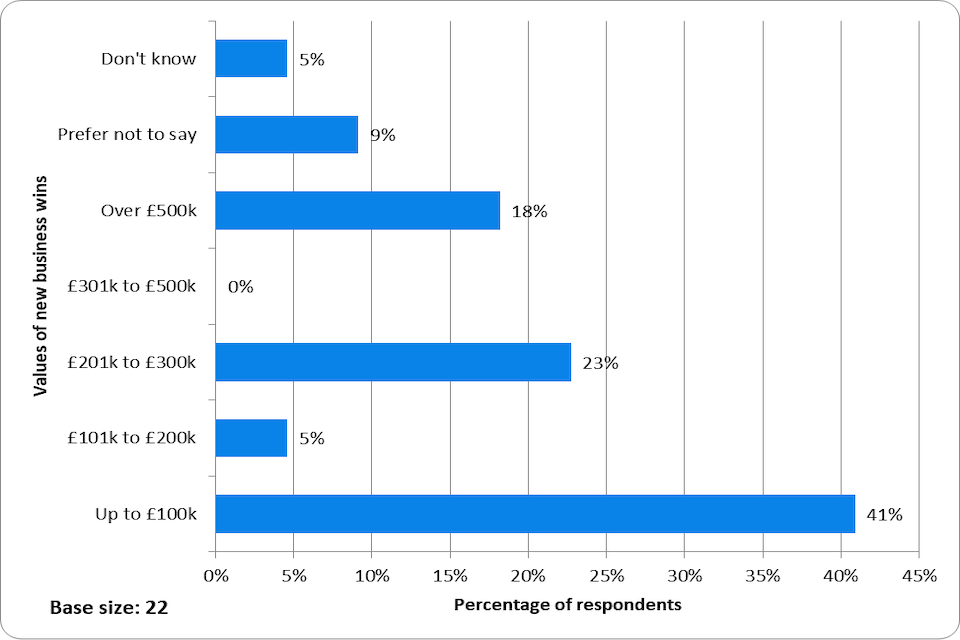

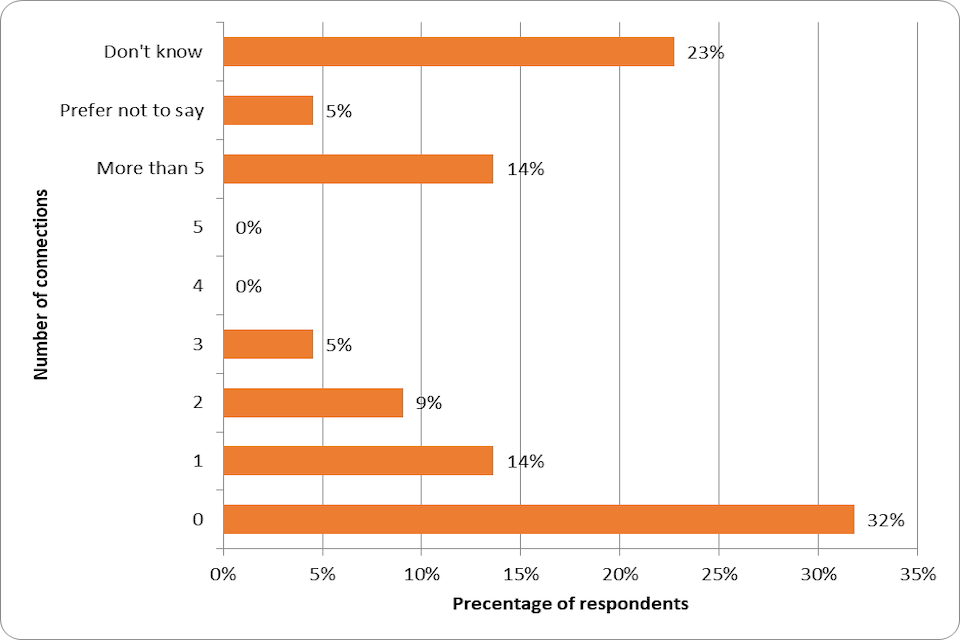

LORCA Cohort Survey Participant