Loneliness Stigma Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA)

Published 12 June 2023

Glossary

| Collectivist society | A society that promotes social connections and citizens depending on each other. [footnote 1] |

|---|---|

| Cross sectional survey | A survey undertaken at one specific point in time. |

| DCMS | The Department for Culture, Media and Sport. |

| Evidence review | A research method which locates and synthesises existing evidence on a particular topic or issue. |

| Framework/Framework method | A method for extracting and analysing data, whereby each row represents one paper, and each column represents a research question or sub-question. |

| Individualistic society | A society that promotes citizens being independent and self-reliant. [footnote 2] |

| Internalisation | Accepting or absorbing an idea or opinion so that it becomes part of one’s own character or views. |

| Loneliness | “A subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want.” [footnote 3] |

| Longitudinal survey | A survey which involves asking the same questions to the same group of people on multiple occasions (e.g. a survey which is repeated every year). This helps build an understanding of how things change over time. |

| Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) | A type of evidence review (see definition above) which seeks to understand the existing evidence on a particular topic within a short period of time. Throughout this report, we refer to the REA as the “review”. |

| Self-stigma | Feeling shame or embarrassment around a personal characteristic or experience, and being inclined to conceal it from others. [footnote 4] |

| Social stigma | Negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination. [footnote 5] [footnote 6] This review explores actual and perceived social stigma. |

| Stigma | Covers both social and self-stigma. |

| Qualitative research | The collection and analysis of non-numerical data (e.g. data from interviews). |

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings of an evidence review commissioned by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) that explores the existing research around loneliness stigma. Loneliness stigma was highlighted as an evidence gap in the Tackling loneliness evidence review, published January 2022 and authored by an expert group of academics. [footnote 7]

Research aims

This review aimed to explore:

-

The existence of loneliness stigma.

-

The relationship between stigma and loneliness, including whether some groups are more likely to experience loneliness stigma.

-

The impact of loneliness stigma.

-

What works in tackling loneliness stigma.

Method

This report presents the findings of a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA). An REA is a form of evidence review which seeks to understand the existing evidence on a particular topic within a short period of time.

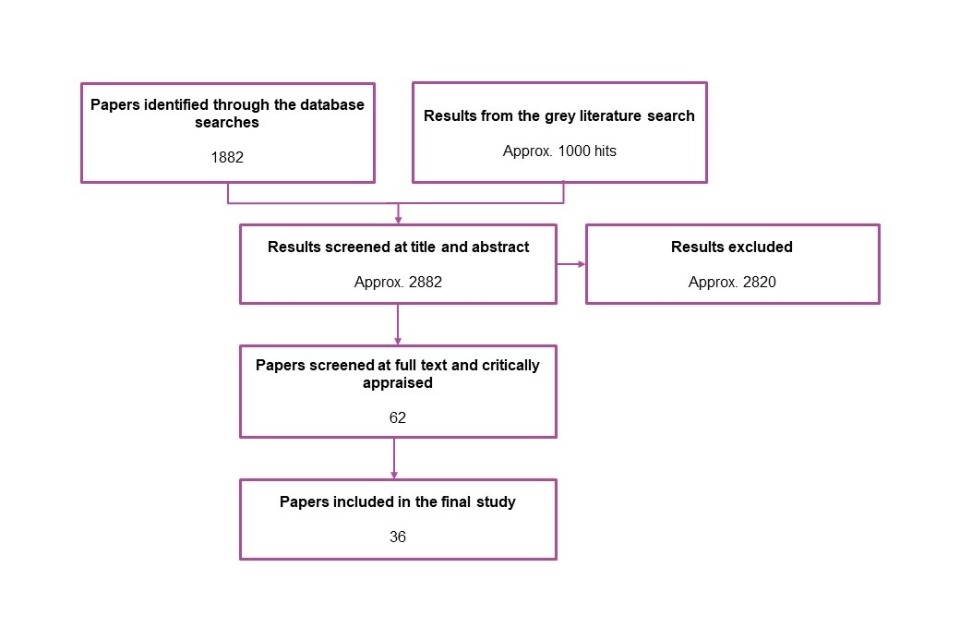

The REA method involved searching academic databases and other websites for evidence on loneliness stigma and assessing each identified paper systematically to decide if it would be included in the review. Through this method, the research team identified 36 papers of relevance to the research questions. Data from these papers was extracted and synthesised, with key findings summarised below.

Key findings

Evidence on loneliness stigma

-

Social stigma is defined as negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination. [footnote 8] [footnote 9] This review explored both actual and perceived social stigma.

-

Actual social stigma: The results of the review found that some people (including people who are and are not experiencing loneliness) do hold stigmatising views of loneliness; however these are not universal and tend to be grounded in stereotypes of people who feel lonely.

-

Perceived social stigma: Some people who feel lonely have spoken directly about a social stigma in interviews, however this stigma was spoken about in a general sense with no specific examples of social stigma provided. Other people experiencing loneliness have described fears of being judged or rejected – while these people did not speak directly about loneliness stigma, their views indicate a perception of such stigma. However, in the BBC Loneliness Experiment, the average participant (including those who did and did not experience loneliness) did not perceive much social stigma in the community when asked directly. [footnote 10]

-

Self-stigma is defined as feeling shame or embarrassment around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others. [footnote 11] This review found that loneliness can be accompanied by feelings of embarrassment or shame. Some people who feel lonely wonder if they are to blame, while others worry that sharing their feelings and asking for support will burden others.

-

Stigma is heightened by greater feelings of loneliness, with evidence demonstrating that self-stigma and the perception of social stigma are more common among people who feel lonely the most often. It is also likely that there are relationships between self-stigma and social stigma, however these require further exploration and testing.

The impact of demographics and other risk factors on loneliness stigma

-

There was limited consideration of loneliness stigma across different demographic groups within the identified research. The factors most considered were age (particularly young people and older adults) and gender.

-

Younger people are more likely to feel embarrassment about being lonely and be inclined to hide their loneliness. The BBC Loneliness Experiment found that many young people perceive their loneliness as something that can be changed or controlled. Researchers have suggested that this can lead young people to feel blame or responsibility for their loneliness. Other surveys identified that young people feel that loneliness in their age group is not recognised as an issue by wider society. Researchers have suggested that both issues have led to increased stigma for this demographic. However, there is also evidence of loneliness stigma among older adults, driven by concerns about burdening family and losing independence.

-

Findings about the impact of gender on loneliness stigma were mixed, with no clear conclusions about whether gender impacts the risk of stigma.

-

Evidence also suggests that socioeconomic status, ethnicity, culture and characteristics of the local place, such as urban or rural classification, may impact experiences of stigma. However, further research is required to explore and test these findings.

Impacts of loneliness stigma

-

Loneliness stigma can prevent people from talking about their experiences of loneliness and seeking help.

-

This results in service providers (and more informal support providers such as family and friends) being unable to identify and help people experiencing loneliness, meaning that their needs go unmet. It may also increase levels of loneliness.

-

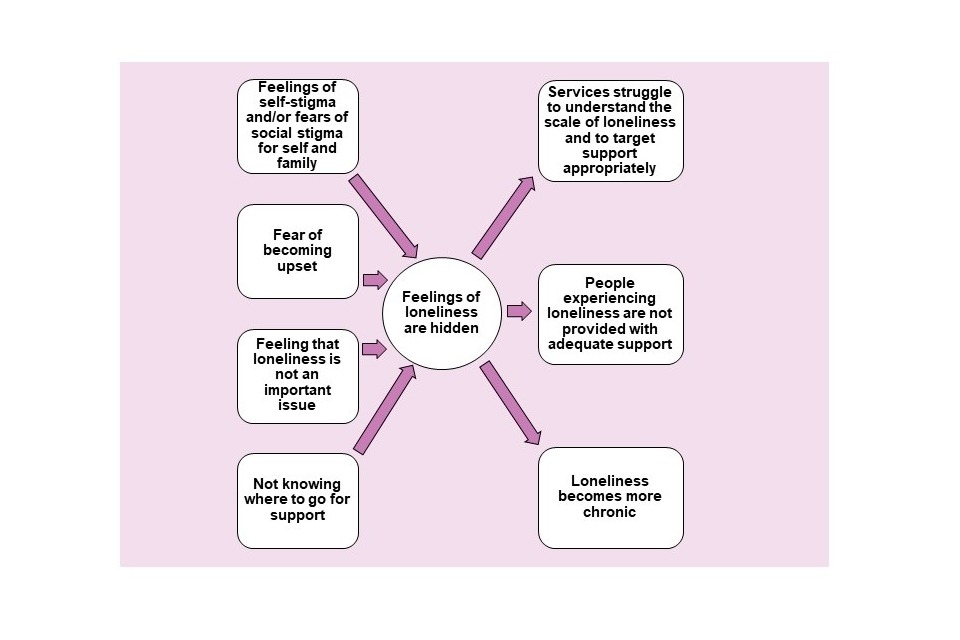

In understanding how stigma operates as a barrier to discussions about loneliness, it is important to be aware of the range of reasons why people are inclined to conceal their experiences of loneliness. These conversations are avoided by people who feel lonely due to feelings of self-stigma, fears of social stigma, perceptions that loneliness is not an important social issue and not knowing where to go to seek support. Some people experiencing loneliness and healthcare professionals (e.g. GPs) have also avoided these conversations due to the actual and perceived distress that such discussions can cause people who feel lonely. Each issue presents linked but distinct challenges.

What works in tackling loneliness stigma?

-

Tackling loneliness stigma has involved action being taken at the national level and more locally, by people directly supporting those who feel lonely (e.g. health and social care professionals and organisations which support social connection).

-

Those working directly with people experiencing loneliness have aimed to address self-stigma (i.e. embarrassment or shame around loneliness) by carefully framing and targeting interventions and using sensitive language. However, for some people experiencing loneliness, the opportunity to have open conversations about their feelings is also important.

-

At the national level, campaigns such as BeMoreUs and #LetsTalkLoneliness have sought to change the narrative around loneliness. This has primarily involved taking steps to normalise loneliness; however future campaigns could also look to address actual and perceived negative stereotypes of people who feel lonely such as those described in Chapter 3. This review found no published evidence of the impact of national campaigns, or whether normalising loneliness reduces stigma or enables more open conversations. However, the Campaign to End Loneliness has commissioned an external evaluation partner to help establish what works in tackling loneliness. While costly, evaluation of future campaigns would provide an evidence base for the use of this intervention.

-

The evidence on ‘what works’ is primarily based on interviews and focus groups with staff and volunteers who support people experiencing loneliness (e.g. through the Silver Line Helpline for older people and Red Cross Community Connector programmes), focusing on the rationale behind interventions to tackle loneliness stigma (including campaigns and wider interventions). Further research is needed to evidence impact and understand what does and does not work in tackling loneliness stigma.

Recommendations for further research

Further research could explore evidence gaps highlighted through this review, in particular:

-

Whether (and how) people experiencing loneliness have experienced stigmatising views from others, along with how people come to feel embarrassment and shame about their own loneliness.

-

The extent of societal assumptions about people experiencing loneliness, the impact of these assumptions and whether they align with the perceptions of those experiencing loneliness.

-

How loneliness stigma is experienced across different demographic groups, particularly across a full range of age groups/the life course, and people of different ethnicities and socioeconomic status.

-

The range of barriers which prevent those experiencing loneliness from accessing support (e.g. fear of social stigma, fear of becoming upset, and not knowing where to go to seek support).

-

How best to capture the impact of interventions (national and local) to reduce loneliness stigma.

-

Robust evaluation of the impact of such interventions.

1. Background and Methods

This report presents the findings of a review commissioned by DCMS exploring the existing research around loneliness stigma.

1.1 Background to the research

Long-term feelings of loneliness are associated with higher rates of mortality and poorer physical health outcomes. [footnote 12] Furthermore, loneliness can predict the onset of common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety. [footnote 13] [footnote 14] The Government’s loneliness strategy sets out the approach to tackling loneliness in England. The goals set out within this strategy include “reduc[ing] the stigma attached to loneliness so that people feel better equipped to talk about their social wellbeing” (pg. 9). However, as the Tackling loneliness evidence review, published in January 2022, demonstrated there are gaps in the evidence base around loneliness stigma, including factors which might accentuate or reduce it.

In this review, loneliness and stigma are defined as follows. These definitions have been updated during the review to align with recent academic papers on loneliness stigma (e.g. Barreto et al., 2022 which reports on the BBC Loneliness Experiment).

-

Loneliness: “A subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want.” [footnote 15]

-

Social stigma: Negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination. [footnote 16] [footnote 17] This review explores actual and perceived social stigma.

-

Self-stigma: Feeling shame around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others. [footnote 18]

-

Stigma: Covers both social and self-stigma.

1.2 Research aims

This review aimed to answer the following research questions:

- Is there a stigma associated with loneliness?

-

What is the relationship between stigma and loneliness?

a) Is there a causal relationship between loneliness and loneliness stigma?

b) Are some groups more likely to experience loneliness stigma?

c) What are the risk factors for loneliness stigmatisation?

- What is the impact of loneliness stigma?

- What works in tackling the stigma of loneliness?

1.3 Methods

A Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) method was used to understand and assess the evidence which currently exists on loneliness stigma. This involved four key stages:

-

Identifying evidence on loneliness stigma by searching academic databases for published papers in academic journals. Websites of organisations that had independently published evidence on loneliness were also searched. These included the British Red Cross, the Campaign to End Loneliness, and the Co-op Foundation.

-

Assessing each identified paper against a set of inclusion criteria to decide if it would be included in the review. This considered if the evidence was relevant to the research questions, and whether it met criteria in terms of research quality. This process identified 36 papers to include in the review.

-

Extracting data from each paper into a framework In the framework each row represented one paper and each column represented a research question or sub-question. Relevant information from each paper was written into the corresponding cell. This grouped information around each research question, enabling the research team to assess the evidence relevant to each question.

-

Reviewing all the evidence relevant to each research question to understand the range of findings and identify where papers supported or conflicted each other. The results of the review are summarised in Chapters 3-6 below.

The full methods (including the inclusion criteria) can be found in Appendix A.

1.4 Structure of the report

This report is divided into the following sections:

-

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the evidence included in this review.

-

Chapter 3 discusses the evidence of loneliness stigma, as well as the relationship between loneliness and stigma.

-

Chapter 4 considers how different groups experience loneliness stigma, and whether there are any other risk factors relating to this type of stigma.

-

Chapter 5 looks at the impacts of loneliness stigma.

-

Chapter 6 considers what works in tackling loneliness stigma.

-

Chapter 7 provides an overview of the key evidence gaps and makes recommendations for further research.

-

Appendix A sets out the full REA method used, including details of the searches made and the inclusion criteria.

-

Appendix B provides details of all 36 papers included in the review.

-

Appendix C provides details of the searches made for relevant papers

2. Research included in this review

This section provides an overview of the types of evidence included in this review. Full references and details can be found in Appendix B.

-

There were 36 papers included in this review. All papers were published after January 2010.

-

Nine papers in this review (25%) have been published in academic journals; the remainder have been published independently by organisations involved in tackling loneliness (e.g. Age UK, The Co-op Foundation, The Campaign to End Loneliness). While both types of papers contain valuable data, those which are not published in academic journals often provide less detail on methodology. This reduces the extent to which the research team can understand limitations of the methods (e.g. whether the range of opinions captured was limited to specific groups or locations).

-

Of the included papers, 31 provide evidence from the UK. Other research took place in Australia, Denmark, Sweden and the United States, and evidence from a worldwide survey conducted as part of the BBC Loneliness Experiment.

-

The evidence on loneliness stigma was limited. Papers often explored loneliness more broadly, with stigma being one of a range of issues reported. Evidence for certain research questions was particularly limited. For example, while some papers considered the experiences of specific groups (research question 2), these tended to focus on age (specifically young people and older adults) and gender. There is little evidence on the impact of initiatives to tackle loneliness stigma (research question 4). Evidence gaps are considered more fully in Chapter 7, which also makes recommendations for further research.

-

Papers used a wide range of methods, including in-depth interviews (47%), evidence reviews (42%), surveys (36%) and focus groups (14%). The most direct evidence on loneliness stigma comes from surveys, whereby participants answered questions on whether they felt embarrassed about being lonely or perceived a stigma in their community. There were few qualitative papers which explored loneliness stigma as a key research topic. Therefore, there is limited qualitative evidence of first-hand loneliness stigma, particularly around the experience of actual social stigma.

3. Evidence on loneliness stigma

Key findings

-

Social stigma is defined as negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination. [footnote 19] [footnote 20] This review explored both actual and perceived social stigma.

-

Actual social stigma: The results of the review found that some people (including people who are and are not experiencing loneliness) do hold stigmatising views of loneliness; however these are not universal and tend to be grounded in stereotypes of people who feel lonely.

-

Perceived social stigma: Some people who feel lonely have spoken directly about a social stigma in interviews, however stigma was spoken about in a general sense with no specific examples of social stigma provided. Other people experiencing loneliness have described fears of being judged or rejected – while these people did not speak directly about loneliness stigma, their views indicate a perception of such stigma. However, in the BBC Loneliness Experiment, the average participant (including those who did and did not experience loneliness) did not perceive much social stigma in the community when asked directly. [footnote 21]

-

Self-stigma is defined as feeling shame or embarrassment around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others. [footnote 22] This review found that loneliness can be accompanied by feelings of embarrassment or shame. Some people who feel lonely wonder if they are to blame, while others worry that sharing their feelings and asking for support would burden others.

-

Stigma is heightened by greater feelings of loneliness, with evidence demonstrating that self-stigma and the perception of social stigma are more common among people who feel lonely the most often. It is also likely that there are relationships between self-stigma and social stigma, however these require further exploration and testing.

3.1 Social stigma

As explained in Chapter 1, social stigma refers to negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people. This section outlines the evidence on actual social stigma (i.e. evidence of negative attitudes or beliefs) and perceived social stigma (i.e. assumed negative attitudes or beliefs).

3.1.1 Actual social stigma

Early studies of loneliness stigma tested participants’ perceptions of hypothetical people experiencing loneliness (e.g. Lau and Gruen, 1992; Rothenberg, 1998, Tsai and Reis, 2009 as cited in Kerr and Stanley, 2021). [footnote 23] In these papers, participants attributed fewer positive characteristics to people experiencing loneliness and were less accepting of them. However, these findings have been challenged by more recent papers included in this review (Kerr and Stanley, 2021; Barreto et al., 2022). In these later papers, it is noted that the hypothetical people experiencing loneliness in earlier experiments had ‘socially inept’ or ‘reclusive’ behaviours attached to them by the researchers, such as not knowing how to make friends or avoiding social contact. As a result, earlier studies may have tested the stigma attached to the assumed behaviours of people experiencing loneliness, rather than the feeling of loneliness itself.

To test the findings in earlier papers, Kerr and Stanley (2021) presented college students with two hypothetical people experiencing loneliness: both people had few close friends and felt isolated and alone, whilst only one of the two displayed reclusive behaviours as well. Participants displayed more stigmatising attitudes toward the hypothetical person who felt isolated and alone and displayed reclusive behaviours. The same paper found that a diverse sample of adults in the United States perceived the non-reclusive person experiencing loneliness as being as warm and competent as a non-lonely person. These findings are supported by analysis of data from the BBC Loneliness Experiment. In this worldwide survey, participants were asked to “imagine a person who is feeling lonely” and indicate on a scale where this person would fall between 21 pairs of adjectives with negative/positive connotations such as “awful/nice”, “unfriendly/friendly”, “unsure/confident”, “unsuccessful/successful” and “sad/happy”. Scores from the 21 pairs of adjectives were added together, with higher scores taken to reflect more positive ratings or perceptions. On average, participants felt that a person feeling lonely would fall closer to the positive adjectives on the scale than the negative adjectives (Barreto et al., 2022). While neither paper was specific to the UK, this research indicates that society may not stigmatise lonely feelings. Instead, stigma is more likely attached to assumed behaviours and characteristics than feelings of loneliness.

In the early studies described above, researchers attributed certain behaviours to people experiencing loneliness (e.g. reclusiveness). However, in more recent qualitative studies, participants themselves have expressed negative assumptions about the attributes and behaviours of people who feel lonely in response to open questions about their perceptions of loneliness. This provides wider evidence that stereotyping of people who feel lonely has led to loneliness stigma. For example, older adults [footnote 24] have assumed that people who feel lonely are a “big commitment” or “need professional involvement” (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2014, pg. 1). Young people interviewed have suggested that people experiencing loneliness “do not fit in”, “seem strange” or have serious mental health issues (ONS, 2018, pg. 22).

The evidence suggests that stereotypes can lead people to place responsibility for loneliness on those who experience it. In interviews and focus groups with young people, older people and General Practitioners (GP) it was suggested that loneliness could result from treating others badly or not making enough effort to initiate or sustain relationships (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2014; Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015; ONS, 2018; Jovicic and McPherson, 2019). Interviews with older people and GPs have also found that some people in these groups individualise loneliness, rather than view it as a societal problem. Within these studies, some participants also suggested that people who feel lonely need to help themselves to reduce loneliness (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015; Jovicic and McPherson, 2019). Researchers and services for older people have highlighted that this focus on individual responsibility can exacerbate stigma (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015) and “neglects the range of structural, environmental and cultural factors that drive feelings of loneliness” (Barreto et al., 2020, pg. 2660).

In contrast, survey data suggests that many people do not place blame on those who experience loneliness. In a national survey of young people, only 24% of participants agreed with the statement “if you feel lonely, it’s your own fault.” (Co-op Foundation, 2021). This is supported by data from the BBC Loneliness Experiment, which tested participants’ views on the causes of loneliness. While there were a range of responses, the average scores suggest that participants felt that loneliness was more likely to have an internal cause than an external cause. [footnote 25] However, participants also generally did not feel that loneliness was caused by something that could be changed or controlled. The authors suggest that many people think that loneliness stems from internal issues which are uncontrollable (e.g. health problems) rather than behaviours which can be modified (Barreto et al., 2022).

As well as being subject to negative beliefs, the definition of social stigma suggests that stigmatised groups are distinguished from the rest of society due to their experience. This review found limited evidence as to whether people view those who feel lonely in this way. In a UK survey, over three-quarters of adults (78%) agreed that “nearly everyone experiences loneliness at some point” (Mental Health Foundation, 2022). This indicates that loneliness is seen as a common experience, rather than something which is not the norm. However, further research would be required to better understand whether this perception applies to all degrees of loneliness (e.g. long-term loneliness, as well as short-term loneliness).

3.1.2 Perceived social stigma

Views of research participants are mixed on whether there is a social stigma around loneliness. Some people who feel lonely and some people from wider groups (e.g. GPs) have spoken directly about a loneliness stigma in interviews (Kantar, 2016; Jovicic and McPherson, 2019). However, this stigma was spoken about in broad terms and participants did not provide any first-hand examples of social stigma (i.e. experiences of the views or actions of others). Wider findings also suggest that people experiencing loneliness perceive a social stigma. For instance, older adults interviewed said they would not discuss their feelings of loneliness to avoid being rejected by friends or relatives (Lykke and Handberg, 2019). Other interview participants worried about being looked down on by their friends (Mental Health Foundation, 2022). In a UK survey, 81% of young people said that they would worry about being embarrassed, mocked, judged or treated differently if they said they were lonely (Co-op Foundation, 2018). However, some people do not perceive a social stigma. In the BBC Loneliness Experiment, the average participant (including people who were and were not experiencing loneliness) did not perceive much stigma in the community when asked directly (Barreto et al., 2022). [footnote 26]

3.2 Self-stigma

‘Self-stigma’ involves feeling shame around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others. This section explores people’s views about their own loneliness.

There is evidence of embarrassment and shame around feelings of loneliness and inclination to conceal these feelings from others. In the BBC Loneliness Experiment, the average participant indicated that they felt some level of shame around loneliness, which led to these experiences being concealed (Barreto et al., 2020). In the UK, embarrassment around loneliness is recognised by those who are and are not experiencing loneliness. In a national survey, 76% of adults (including those who did and did not feel lonely) agreed that “people often feel ashamed or embarrassed about feeling lonely” (Mental Health Foundation, 2022). However, a further UK survey found that while 30% of people felt embarrassment around loneliness, 37% did not (Mental Health Foundation, 2010).

Feelings of embarrassment and shame may be linked to how people who feel lonely perceive themselves. People experiencing loneliness have expressed feelings of self-blame or personal failure (Lykke and Handberg, 2019; Mental Health Foundation, 2022; Neves et al., 2022). Self-blame may also indicate a concern that loneliness is not a normal or common experience (and, therefore, must have an individual cause). It has been suggested that social media may enforce this message as people often do not present “normal negative feelings” online (Ko et al., 2022, pg. 97). Sharing feelings of loneliness and asking for support can also cause people to feel burdensome. One national survey found that 76% of respondents found it difficult to admit to feelings of loneliness as they did not want to be a burden (National Development Team for Inclusion, 2017). Furthermore, the Silver Line (a telephone help service for older people) reported that 70% of those accessing their helpline were reluctant to ask for help because they did not want to burden others (Wilcox, 2014). Interview data supports this, with some people experiencing loneliness being concerned about burdening or annoying their family and friends by talking about their experiences (Lykke and Handberg, 2019; Mental Health Foundation, 2022). While papers do not explicitly make the link, it may be that feelings of self-blame and being a burden contribute to the experience of shame and embarrassment. Further qualitative research is needed to explore this relationship.

3.3 The relationship between loneliness, social and self-stigma

Experiences of stigma are greater for lonelier people. Surveys show that the more often someone feels lonely, the more likely they are to identify social stigma in their community, feel shame around loneliness and assume that loneliness is caused by an individual issue (e.g. reclusiveness) rather than a societal problem (Barreto et al., 2022; Mental Health Foundation, 2022). The relationship between loneliness and stigma is explored further in Chapter 5, specifically the impact of stigma on people experiencing loneliness.

This review has also identified two potential relationships between self-stigma and actual and perceived social stigma, which would merit further exploration. These are outlined below.

Self-stigma may lead people to assume that others think badly of them. It has been suggested based on wider research that people who rate themselves negatively expect others to do the same (Kerr and Stanley, 2020) and therefore self-stigma can contribute to perceived social stigma. This is supported by qualitative evidence, whereby individuals with self-stigmatising views also anticipate negative reactions from others (e.g. Mental Health Foundation, 2022). However, further research is required to fully understand the relationship between self-stigma and the perception of social stigma in the context of loneliness.

Secondly, perceived or actual social stigma may increase self-stigma. As highlighted in section 3.1, the perception of social stigma can lead people to conceal feelings of loneliness (Co-op Foundation, 2018; Lykke and Handberg, 2019; Mental Health Foundation, 2022). However, it is not clear whether this perception of social stigma also causes people experiencing loneliness to feel embarrassment or shame (i.e. self-stigma). Furthermore, this review has not found any evidence of how the actual, expressed views of others (actual social stigma) impacts self-stigma. Some definitions of self-stigma assume that people develop negative feelings about themselves by internalising the attitudes of others (e.g. Ko et al., 2022), however it is currently unclear whether this principle applies in the case of loneliness.

4. The impact of demographics and other risk factors on loneliness stigma

Key findings

-

There was limited consideration of loneliness stigma across different demographic groups within the identified research. The factors most considered were age (particularly young people and older adults) and gender.

-

Younger people are more likely to feel embarrassment about being lonely and be inclined to hide their loneliness. The BBC Loneliness Experiment found that many young people perceive their loneliness as something that can be changed or controlled. Researchers have suggested that this can lead young people to feel blame or responsibility for their loneliness. Other surveys identified that young people feel that loneliness in their age group is not recognised as an issue by wider society. Researchers have suggested that both issues have led to increased stigma for this demographic. However, there is also evidence of loneliness stigma among older adults, driven by concerns about burdening family and losing independence.

-

Findings about the impact of gender on loneliness stigma were mixed, with no clear conclusions about whether gender impacts the risk of stigma.

-

Evidence also suggests that socioeconomic status, ethnicity, culture and characteristics of the local place, such as urban or rural location, may impact experiences of stigma. Further research is required to explore and test these findings.

4.1 Age

Age was found to have an impact on experiences of loneliness stigma. [footnote 27] However, comparisons are difficult due to the differing ways in which data was collected across studies. Some papers found that younger people are more likely to experience self-stigma. One UK survey of adults found that embarrassment about admitting to feeling lonely decreased with age (Griffin, 2010). This is supported by the BBC Loneliness Experiment which found that younger people expressed more shame and a greater inclination to conceal feelings of loneliness (Barreto et al., 2022). In contrast, one evidence review cited a finding from a national UK survey that people aged 16-44 were more likely to admit to feeling lonely, compared to people aged 45+ (National Development Team for Inclusion, 2017). While the findings of this last survey appear to conflict with those above, each survey measured related but distinct concepts. Therefore, these findings could co-exist. For example, someone may feel that they would be likely to admit to loneliness if asked, but also feel inclined to conceal it.

The evidence highlights that different age groups are likely to experience stigma for different reasons, as set out below.

It is suggested that young people experiencing loneliness may be stigmatised due to the perception that loneliness is less common among this age group (Barreto et al., 2022). Whereas the experience of loneliness among older people has been “normalised”, it is suggested that younger people are assumed to be highly social (Barreto et al., 2022, pg. 2662). Therefore, “feeling lonely would make young people different from this perceived norm” which may increase stigma (Barreto et al., 2022, pg. 2662). However, views on the prevalence of loneliness among young people (and any associated stigma) may vary across different age groups. In a survey of young people, a minority (23%) felt that loneliness in their age group is treated as a serious social issue, while a majority (65%) agreed that loneliness is a problem for their age group (Co-op Foundation, 2019). This demonstrates that many young people acknowledge loneliness as a common experience among their age group but feel that wider society does not. This suggests that the perception that loneliness is less common among young people is more likely to drive social (rather than self-) stigma, and these stigmatising views are most likely to be found among older age groups. However, views also differ among young people, with one survey finding that 16- to 25-year-olds were more likely than 10- to 15-year-olds to agree that loneliness was a “normal emotion” (Co-op Foundation, 2021b).

While some young people acknowledge loneliness as being common among their peers, this group may instead self-stigmatise on the basis that they believe they are to blame for their loneliness. Barreto at al. (2022) assessed the impact of age on whether people see loneliness as controllable. They found that older people were more likely to link loneliness to uncontrollable factors, while younger people were more likely to see loneliness as controllable. The authors suggest that younger people attribute loneliness to factors which could be considered within their control, such as their friendships, which can lead to feelings of self-blame (Barreto et al., 2022). In contrast, older people view loneliness as caused by issues outside their control such as health and widowhood. Diaries written by older adults in Australia highlighted that self-stigma for this group can be driven by concerns about burdening family and losing independence (Neves et al., 2022). Altogether, this suggests that while both younger and older people experience self-stigma, the reasons for this experience differ across age groups.

4.2 Gender

The impact of gender on self-stigma is unclear. Some papers have suggested that men are less likely than women to admit to feeling lonely. In a national survey, 72% of women said they were likely to admit to feeling lonely, compared to 53% of men (National Development Team for Inclusion, 2017). This could be due to men feeling more embarrassment or shame around loneliness. For instance, in a national survey of young people, young men and boys (25%) were more likely to agree that loneliness is something to be embarrassed about compared to young women and girls (17%) (Co-op Foundation, 2021b). However, other findings contrast with this. For example, the BBC Loneliness Experiment (a worldwide survey of people aged 16+) found that women were more likely than men to agree that they felt ashamed or embarrassed about feeling lonely (Barreto et al., 2022). Furthermore, a survey of young people found that “feeling embarrassed or ashamed” would prevent 66% of young women but only 55% of young men talking to someone about feeling lonely (Co-op Foundation, 2018). Barreto et al. (2022) have suggested that men are less likely to express shame than women in general, which might influence these findings.

Gender may also impact perceptions of social stigma and wider views around loneliness. Findings from the BBC Loneliness Experiment identified that men of all ages were more likely to perceive a stigma around loneliness in their community and were more likely than women to view loneliness as controllable (Barreto et al. 2022). The authors suggest a reason for this could be that men are exposed to more social stigma than women. As a result, the authors posited that men might be more likely to believe that society holds stigmatising views. However, a national survey of young people found that “fear of being judged or mocked” would prevent 52% of young women but only 42% of young men from speaking about loneliness (Co-op Foundation, 2018). This could imply that young men are exposed to less social stigma around loneliness. An alternative explanation for men being more likely to perceive social stigma could be that men hold more stigmatising views about loneliness than women, and then assume that others in their community feel as they do (Barreto et al., 2022). This is supported by a survey which found that 27% of boys and young men believe that if you feel lonely it’s “your own fault” compared to 20% of girls and young women (Co-op Foundation, 2021b). These findings are drawn from surveys with young people or broader worldwide samples and would benefit from further testing with a more representative sample in the UK.

During interviews with older men, fathers were highlighted as at risk of stigma due to perceptions that loneliness is “not in keeping with their family role as the father-type figurehead” (Willis et al., 2019, pg. 2). Experiences of mothers were not discussed, and no comparisons were made between fathers and childless men. However, this finding suggests that loneliness research should consider how social norms inform stigmatising views.

4.3 Socioeconomic status

Among young people, socioeconomic status impacts experiences of loneliness stigma. In a survey of young people, 85% of the most affluent respondents felt comfortable talking to peers about feeling lonely compared to 79% of the least affluent respondents (Co-op Foundation, 2018). The least affluent respondents were also less likely to feel comfortable talking to both family members and professionals. Furthermore, among young people who had received free school meals, 28% said loneliness was something to be embarrassed by compared to 17% of young people who had never received free school meals (Co-op Foundation, 2021b). This suggests that socioeconomically disadvantaged young people may be more likely to experience stigma around loneliness.

This survey also found that young people who have received free school meals were twice as likely to be lonely “often or always” than those who did not (20% compared to 10%) (Co-op Foundation, 2021b). As outlined in Chapter 3, the more frequently an individual feels lonely, the more likely they are to hold negative, and potentially stigmatising, views about their loneliness. Although not suggested by the authors, this could mean that socioeconomic status does not directly impact whether a person who feels lonely experiences stigma. Instead, socioeconomic status may impact the likelihood of a person experiencing more frequent loneliness (and, therefore, experiencing loneliness stigma).

4.4 Ethnicity, culture and place

There was evidence to suggest that ethnicity, culture and place may impact experiences of loneliness stigma. However, each finding was evidenced in only one paper. Therefore, the impact of these factors also merit further exploration.

Regarding ethnicity, a survey conducted by the British Red Cross found that 64% of Pakistani respondents said they would never admit to feeling lonely compared to 43% of White British respondents and 34% of Black Caribbean respondents. Similarly, 70% of Pakistani respondents said they would worry about what others thought about their feelings of loneliness, compared to 60% of White British respondents and 55% of Black Caribbean respondents (Kennedy et al., 2019). It was suggested that cultural differences may drive different experiences of loneliness stigma. Researchers speculated that people from cultural backgrounds where extended families often live together, or within a close community, might be more reluctant to admit to feeling lonely in case it suggests that their family has failed in some way (Kennedy et al., 2019).

Two papers found that national culture may impact experiences of loneliness stigma. In the BBC Loneliness Experiment, respondents from “collectivist” countries were more likely to feel that loneliness was controllable and perceive stigma in their community, compared to respondents from “individualistic” countries (Barreto et al., 2022). [footnote 28] It was proposed that collectivist societies that thrive on strong social networks and interdependence are more likely to take a negative view of loneliness (Barreto et al., 2022). Pertinently, in interviews with people experiencing loneliness, reference was also made to the English “stiff upper lip” as a reason why loneliness might be stigmatised in society (Mental Health Foundation, 2022, pg. 34).

However, wider evidence suggests that the characteristics of the local place may also be important to the experience of stigma. To date, research has only explored the impact of rural/urban classification, however other local factors may also be important. A survey of young people found that those from rural communities, while less likely to feel lonely than those from urban areas, were more reluctant to talk about their experiences of loneliness (70% compared to 58%). Young people from rural areas (45%) were also less likely to agree that feelings of loneliness are “normal” for someone their age than their urban peers (57%) (Co-op Foundation, 2021a). This indicates that place-based understandings of loneliness stigma should take a community-based approach. Further qualitative research could explore the heterogeneity of loneliness stigma in “collectivist” and “individualistic” societies.

5. Impacts of loneliness stigma

Key findings

-

Loneliness stigma can prevent people from talking about their experiences of loneliness and seeking help.

-

This results in service providers (and more informal support providers such as family and friends) being unable to identify and help people experiencing loneliness, meaning that their needs go unmet. It may also increase levels of loneliness.

-

In understanding how stigma operates as a barrier to discussions about loneliness, it is important to be aware of the range of reasons why people are inclined to conceal their experiences of loneliness. These conversations are avoided by people who feel lonely due to feelings of self-stigma, fears of social stigma (i.e. the negative perceptions of others), perceptions that loneliness is not an important social issue and not knowing where to go to seek support. Some people experiencing loneliness and healthcare professionals (e.g. GPs) have also avoided these discussions due to the actual and perceived distress that such conversations can cause people who feel lonely. Each issue presents linked but distinct challenges.

This section briefly illustrates the impacts of loneliness stigma in Figure 5:1, before discussing specific impacts on the individual, service providers and others working to tackle loneliness.

5.1 Impacts on the individual

Research shows that many people find it difficult to discuss or admit to feelings of loneliness and seek help. This is well-evidenced across different age groups. For example, a survey of young people found that just 25% felt confident talking about loneliness (Co-op Foundation, 2019), while another found that only 47% would feel comfortable asking for help if they felt lonely (Co-op Foundation, 2021). Similarly, a survey of older adults identified that 84% found it difficult to admit that they felt lonely, and only 40% of those who admitted to feeling lonely had ever mentioned their feelings to a family member (Wilcox, 2014). This hesitancy to discuss loneliness is recognised by the public. A nationally representative survey found that only 29% of respondents agreed that “people who feel lonely are likely to talk about it, if they get the opportunity” (Mental Health Foundation, 2022).

Loneliness stigma is a key barrier to discussions around loneliness. As discussed in Chapter 3, some people who feel loneliness do not discuss their experiences due to feelings of embarrassment (i.e. self-stigma) (Mind, 2017; NPC, 2019; Barreto et al., 2022), concerns about being a burden (Wilcox, 2014) or because they fear judgement or rejection from others (i.e. social stigma) (NPC, 2019; Mental Health Foundation, 2022). In particular, qualitative research has found that loneliness stigma prevents people from admitting loneliness to friends or family (Wilcox, 2014; Lykke and Handberg, 2019; Neves et al., 2022).

Furthermore, some people do not discuss experiences of loneliness due to fears that their family will be subject to social stigma. Services for older people have highlighted that families of people who feel lonely can be portrayed as uncaring (Callen, 2013) and experienced people hiding feelings of loneliness to “try and protect their relatives” (Kennedy et al., 2019, pg. 27). Therefore, fear of stigma may prevent some people discussing feelings of loneliness with friends and family, while also refusing to seek wider help to protect those close to them.

However, research also highlights that people do not discuss experiences of loneliness for wider reasons:

-

The perception that loneliness is not an important issue. During interviews, people experiencing loneliness have suggested that there were other social issues or hardships that felt “more warranting of attention” (Kantar, 2016, pg. 27). [footnote 29] This perception that loneliness is not a legitimate issue prevented them from seeking support.

-

The distress associated with discussions about loneliness. In interviews with healthcare professionals and patients at a rehabilitation clinic, discussions around loneliness were described as “painful” (Lykke and Handberg, 2019, pg. 5). GPs have also raised concerns about upsetting patients by asking them about loneliness (Jovicic and McPherson, 2019).

-

Availability of support. There may also be a broader issue about the availability of formal and informal support for people experiencing loneliness. A survey of 100 Silver Line Helpline [footnote 30] callers found that 53% felt they had no one else to talk to other than the service provider (Wilcox, 2014). This is supported by qualitative evidence, whereby participants suggested that they did not know where and how to ask for help (Kennedy et al., 2019).

There may be links between these barriers and self-stigma (feelings of embarrassment and shame) or social stigma (negative perceptions of others). However, further research would be required to understand the existence and nature of any relationships.

A clear impact of loneliness stigma is that people do not seek help and their needs go unmet. However, stigma may also impact the appropriateness of wider support that individuals are receiving. For instance, a healthcare professional has suggested that some patients seeking help for mental health conditions such as depression might be reluctant to admit – due to feelings of shame – that they are also suffering from loneliness, thereby impacting how their mental health is understood and supported (Olds and Schwartz, 2009 as cited in Griffin, 2010). This evidence has not been scrutinised through this review. However, wider research (outside the scope of this review) has also found that there is a bidirectional relationship between mental health and loneliness, [footnote 31] with each influencing the other. While further research is required, this supports the suggestion that understanding loneliness will be key to understanding and supporting people with mental health conditions.

In addition to preventing people from seeking support, internal feelings of shame and self-blame may result in increased loneliness. A survey of university students found that individuals who associate feelings of shame with their experiences of loneliness were more likely to self-isolate and feel disconnected from others (Ko et al., 2022). Qualitative research provides the example of young people dropping out of university rather than seeking help for feelings of loneliness and isolation (ONS, 2018). Therefore, loneliness stigma can contribute to social isolation which can result in increased feelings of loneliness (Barreto et al., 2022; Ko et al., 2022). Furthermore, interviews with people feeling lonely also found that stigma prevents help-seeking when loneliness is first experienced, resulting in needs going unmet and loneliness becoming long-term (Kantar, 2016). As a result, loneliness is more likely to become chronic as a result of stigma.

Figure 5:1 Impacts of loneliness stigma

5.2 System-level and organisational impacts

As well as having an individual-level impact, loneliness stigma has broader implications for organisations that provide support services.

Stigma leads to the underreporting of loneliness, making accurate societal levels of loneliness difficult to capture. Through interviews, experts on loneliness (including academics, clinicians, and service users) have highlighted that loneliness was underreported in surveys (Mann et al., 2017). This issue is particularly apparent with direct questions about loneliness (in contrast to broader questions about participants’ feelings which are analysed to produce a loneliness score) (Jopling, 2014). It is also difficult to measure the impact of loneliness support services due to a lack of accurate data on how service users felt before and after the intervention (Jopling & Howells, 2018).

As discussed in the section above, individuals experiencing loneliness avoid seeking help due to stigma, making it challenging for service providers to identify and support individuals experiencing or at risk of loneliness (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015; Campaign to End Loneliness, 2016). During learning events, service providers consistently identified stigma as a challenge to identifying and addressing loneliness (Jopling and Howells, 2018). Furthermore, once those in need of support have been identified, it may also be difficult to discuss loneliness or provide appropriate support due to the fears of rejection or stigmatisation discussed above (Lykke and Handberg, 2019).

This has further implications for organisations looking to identify and support people experiencing loneliness. It may be necessary to establish alternative ways of identifying people who feel lonely [footnote 32] that do not require people to admit feelings of loneliness (Davidson and Rossall, 2015). Additionally, proactive outreach efforts may be required to ensure that help is offered to as many people as possible (Jopling, 2020). Further recommendations of how interventions can be adapted to successfully support people experiencing loneliness and break down stigma are discussed in Chapter 6 of this report.

6. What works in tackling loneliness stigma?

Key findings

-

Tackling loneliness stigma has involved action being taken at the national level and more locally, by people directly supporting those who feel lonely (e.g. health and social care professionals and organisations which support social connection).

-

Those working directly with people experiencing loneliness have aimed to address self-stigma (i.e. embarrassment or shame around loneliness) by carefully framing and targeting interventions and using sensitive language. However, for some people experiencing loneliness, the opportunity to have open conversations about their feelings is also important.

-

At the national level, campaigns such as BeMoreUs and #LetsTalkLoneliness have sought to change the narrative around loneliness. This has primarily involved taking steps to normalise loneliness; however future campaigns could also look to address actual and perceived negative stereotypes of people who feel lonely (such as those described in Chapter 3. This review found no published evidence of the impact of national campaigns, or whether normalising loneliness reduces stigma or enables more open conversations. However, the Campaign to End Loneliness has commissioned an external evaluation partner to help establish what works in tackling loneliness. While costly, evaluation of future campaigns would provide an evidence base for the use of this intervention.

-

The evidence on ‘what works’ is primarily based on interviews and focus groups with staff and volunteers who support people experiencing loneliness (e.g. through the Silver Line Helpline for older people and Red Cross Community Connector programmes) focusing on the rationale behind interventions to tackle loneliness stigma (including campaigns and wider interventions). Further research is needed to evidence impact to understand what does and does not work in tackling loneliness stigma.

6.1 Working directly with people experiencing loneliness

6.1.1 Framing interventions

It has been suggested that loneliness interventions could further stigmatise individuals if they are not “advocated sensitively” (Victor et al, 2018, pg. 51). This could involve framing services positively to emphasise connection and the development of meaningful relationships or “friendship networks”, rather than focusing on loneliness or isolation (Jopling and Howells, 2018; Victor et al, 2018). For example, New Philanthropy Capital (NPC, 2019) recommend framing interventions as “well-being” initiatives instead of “loneliness” interventions, and naming intervention staff or befrienders as “champions” in place of “volunteers”.

Activity-based interventions that place emphasis on the activity, rather than loneliness, may help avoid stigma (Davidson and Rossall, 2015). One evidence review found qualitative evidence that older participants preferred services which were activity-based, where they were not labelled as lonely (Mansfield et al, 2019). Likewise, within a diary study, older adults highlighted the importance of interventions facilitating “deeper social engagement, matching people’s interests and making them feel valuable” (Neves et al., 2022, pg. 22). Altogether, this suggests that framing interventions around an activity could encourage more people to take up opportunities for social connection.

6.1.2 Targeting interventions

To overcome stigma, loneliness interventions can be publicised and embedded in the wider community (Jopling and Howells, 2018), rather than being specifically targeted at people experiencing loneliness. For example, Men’s Sheds is a non-profit organisation which provides a local space for men to engage in activities, such as craftwork, while building social connections (Coughtrey et al., 2019). While it may be appropriate to target interventions at a specific population group, the demographic framing of an intervention can affect people’s receptiveness and willingness to engage (NPC, 2019). This could, in part, be due to some groups experiencing loneliness stigma intertwined with other forms of stigma. For instance, it has been posited that people may not engage with interventions aimed at ‘older’ people due to the stigma attached to this term (NPC, 2019). To mitigate this, it has been suggested that consulting local people on their needs and interests can support intervention engagement (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015).

6.1.3 Using sensitive language to discuss loneliness

The language used to discuss loneliness is an important consideration. This can involve indirect and sensitive questioning. Community services and commissioning managers have suggested the need for positive questioning, such as “how can we support you?”, rather than directly asking “are you lonely?” (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015). Direct questioning can make individuals “feel extremely vulnerable” and suggest there is something “wrong” with them (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2014, pg. 4).

Asking people about their general feelings and actively listening for signs of loneliness can help support understanding. Staff in community programmes have identified that suggestions of loneliness, such as being housebound or isolated, often come up naturally in conversation (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015). To enable sensitive discussions around loneliness, service providers at a UK-wide learning programme highlighted the importance of training for frontline staff (Jopling and Howells, 2018). For example, within a telephone-based befriending service, helpline staff are trained to sensitively question a service user to ascertain their level of need and suggest next steps (Callan, 2013).

6.1.4 Providing people with the opportunity to speak about loneliness directly

While sensitive language is important when tackling loneliness, it has also been argued that to break down stigma, services must not “shy away” from talking about loneliness, but address it head on (Jopling and Howells, 2018, pg. 40).

Failing to address loneliness can have negative impacts. Evidence suggests that talking about loneliness is sometimes avoided by GPs and other health and care professionals. Interviews with older people in a home-based rehabilitation intervention found loneliness was rarely addressed by health care professionals, making it “impossible” for service users to discuss their feelings (Lykke and Handberg, 2019, pg. 6). It is suggested that “verbalising loneliness can play a role in breaking the taboo of loneliness” (pg. 8) and mitigate the impacts of stigma. Although this study took place outside of the UK, similar issues have been identified by UK GPs, some of whom avoided discussions about loneliness for fear of opening a “pandora’s box of shame” (Jovicic and McPherson, 2019, pg. 380). The same GP participants also reported finding conversations about loneliness to be “unpredictable” and therefore “hard to manage” in the short amount of time given for individual appointments. The authors suggest this could worsen loneliness stigma, as it’s perceived that loneliness is “an issue that is too embarrassing for the patient to ask about” (Jovicic and McPherson, 2019, pg. 380).

Some people may wish to discuss their loneliness openly and directly. In an evaluation of the Silver Line Helpline (a telephone helpline and befriending service), it was highlighted that some callers were very willing to talk about their loneliness with helpline staff (Callan, 2013). In this case, the anonymous nature of the calls, alongside the emotional detachment of staff, were thought to encourage people to engage in these discussions without feelings of shame or guilt. Callers reported that the service made them feel less lonely, more confident, safe and that someone cared about them (Wilcox, 2014). Insights from the British Red Cross ‘Community Connectors’ programme also suggest that some people appreciate the opportunity to discuss their loneliness openly without fear of judgement (Jopling and Howells, 2018).

However, as discussed in Chapter 5, stigma is not the only barrier to discussions of loneliness. Both people who feel lonely and healthcare professionals have highlighted that discussions of loneliness can be very distressing for some. Therefore, it is likely that tackling stigma will require a nuanced approach which includes using sensitive language with service users, while finding ways to encourage open conversations.

6.2 Changing perceptions of loneliness at the national level

6.2.1 Changing the narrative around loneliness

It was suggested by staff and volunteers from Community Connector services [footnote 33] that actions such as emphasising the seriousness of loneliness can pathologise those who experience it (Jopling and Howells, 2018). These opinions were not explored in detail, but the perceived issue appears to be that stigma is driven by views that loneliness is uncommon or not the norm. This review has not found conclusive evidence on whether this is the case, or how perceptions around the prevalence of loneliness might impact people experiencing it (if at all). However, it has been argued that highlighting loneliness as a “normal part of life” (Jopling and Howell, 2018, pg. 40) and common across all population groups would be key to legitimising lonely feelings (Mental Health Foundation, 2022).

As discussed in Chapter 3, stereotypes can exacerbate loneliness stigma (e.g. the stereotype that those experiencing loneliness display reclusive behaviours). Changing the narrative around what causes loneliness may help “reduce people’s tendency to blame themselves for being lonely” (The Mental Health Foundation 2022, pg. 38). Whilst there is little discussion of how this narrative could be reframed, both the Mental Health Foundation and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) suggest that it may be helpful in some cases to emphasise common, situational reasons for loneliness (e.g. moving to a new place of education or work) (ONS, 2018; The Mental Health Foundation, 2022). Understanding the factors that can lead to loneliness could help reduce both social and self-stigma associated with feeling lonely.

6.2.2 The role of national campaigns

Some national campaigns have aimed to normalise loneliness and address the stigma around it. For example:

-

Be More Us was a digital campaign run as part of the Campaign to End Loneliness which encouraged people to connect with others (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2020). The campaign website makes statements to normalise the experience of loneliness, such as “almost half of UK adults say that their busy lives stop them from connecting with other people.” The campaign reached over 100 million people (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2020).

-

The #LetsTalkLoneliness campaign used the strapline “All of us can experience loneliness at some point in our lives. It’s time we started talking about it” as an attempt to normalise loneliness (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2020). The campaign encouraged people to share stories of loneliness to normalise the experience.

This review did not find any published evidence as to the impacts of these campaigns (i.e. whether and how the campaigns changed attitudes and impacted people experiencing loneliness). However, learnings from wider anti-stigma campaigns such as Time to Change suggest campaigns can be effective in changing attitudes and perceptions towards people who have been stigmatised (Jopling and Howells, 2018). The Campaign to End Loneliness has commissioned an external evaluation partner to help establish what works in tackling loneliness. Barriers to assessing impact can include the timelines required to measure impact or the cost involved in conducting an external evaluation (Jopling, 2020, pg. 91). However, gathering data on the impact of a campaign at different time points, and building in evaluation from the outset, may help a clearer “evidence base” emerge as to what works in tackling stigma and why (Jopling, 2020, pg. 91).

7. Recommendations for further research

This review has identified several evidence gaps, and makes recommendations below to inform future research.

-

While surveys have asked whether people perceive loneliness stigma in their community, there was little research which explored personal experiences of social stigma. Further research could sensitively explore whether (and how) people who feel lonely have experienced stigmatising views from others.

-

The concept of self-stigma assumes that negative perceptions of others are internalised by people experiencing loneliness. It has been suggested that people experiencing self-stigma may be more likely to internalise negative perceptions. However, this review found little evidence as to how people who feel lonely come to hold negative perceptions about their loneliness. Further research could explore which factors are influential in how people feel about their own loneliness. It may also be possible to gain insights from wider research about the link between social and self-stigma, including literature which examines stigma in the context of mental health.

-

Papers included in this review suggest that social stigma around loneliness may centre around particular stereotypes of people who feel lonely. For example, stigma can be driven by perceptions that loneliness is under one’s own control. The impact of this is particularly apparent in the case of young people, as described in Chapter 4. Further research could explore the extent of societal assumptions about people who feel lonely (including assumptions around the ability to control loneliness), the impact of these assumptions and whether they align with the perceptions of those experiencing loneliness.

-

While some papers consider the experiences of specific groups, these tend to focus on age (in particular, young people and older adults) and gender. Furthermore, some focus on one group (e.g. younger people) rather than comparing experiences across demographics. There is also little exploration of how loneliness stigma may operate for wider demographics such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status and those subject to wider stigmas (e.g. people with mental health issues, homeless people and LGBTQ+ groups). Exploring the experiences of different groups can be challenging, due to the need to have sufficient sample sizes to make informed conclusions. It may also be difficult to reach some of these groups, which are often underrepresented in research. However, future qualitative research could further explore stigma across different groups by focusing on certain characteristics (e.g. age or ethnicity) and/or ensuring that stigma is explored with diverse samples. Findings could later be corroborated by further survey research, with sufficiently large and diverse samples to enable robust comparison of different population groups. It may be possible to draw on existing survey datasets, such as the UK data from the BBC Loneliness Experiment.

-

An important impact of stigma is its role in preventing people from talking about loneliness and accessing support. However, this review has also identified wider barriers to talking about loneliness which may or may not be linked to stigma. Therefore, it is currently challenging to draw conclusions on the impact that reducing stigma alone would have for people experiencing loneliness. Further research could explore the range of barriers which prevent those experiencing loneliness from accessing support, and the impact of tackling stigma in this context.

-

This review found no published evaluation of the impact of initiatives or approaches to tackle loneliness stigma (including campaigns and wider interventions). This means that it is not possible to provide evidence-based recommendations on what does and does not work in tackling loneliness stigma. Further research could seek to better understand how interventions (including campaigns) can reduce stigma and explore how to capture impact going forward. This could involve building evaluation into future initiatives to tackle loneliness stigma and exploring learnings from wider campaigns to address stigma which have sought to measure impact (e.g. Time to Change).

Authors and acknowledgments

Authors: Emily Sawdon, Cate Standing-Tattersall, Phoebe Weston-Stanley, Alexander Martin, Sokratis Dinos

The report authors would also like to thank Professor Pamela Qualter, University of Manchester for her expertise in support of this research.

Appendix A. Methodology

The information in this Appendix builds on the summary of the REA method provided in Chapter 1. Each stage of the process was developed in collaboration with DCMS.

Identifying evidence on loneliness stigma

Academic literature

Four academic databases were searched to identify papers which had been published in academic journals:

-

Medline

-

PsycInfo

-

Scopus

-

Sociological Abstracts (which includes Social Services Abstracts)

The search terms were in the form of Boolean search strings [footnote 34] that incorporated a range of key words and concepts to capture papers related to the research questions. These search strings were developed in collaboration with a search specialist based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria below and piloted in PsycInfo, before being finalised. Searches took place on 27th August 2022.

Grey Literature

The following websites were manually searched to identify relevant ‘grey literature’ (papers not published in academic journals).

These websites were searched using key words and phrases, such as “loneliness”, “stigma”, “loneliness stigma” and “shame around loneliness”. The search applied a fluid approach due to the different capabilities of each website’s search function. For example, some websites allowed for parameters to be set (e.g. date) or Boolean search terms, whilst others supported categorisation or filter searches.

Searches took place between 30th August and 11th September 2022.

Evidence selection

Each identified paper was assessed against a set of criteria to decide if it would include it in the review. Papers were screened in two stages: (1) title and abstract and (2) full-text.

Title and abstract screening

The titles and abstracts of all the papers were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria set out below. Papers that appeared to be relevant were included for full-text review. Screening of academic papers was conducted using the Covidence platform. [footnote 35] For grey literature papers, screening took place at source whereby papers were screened on the website. Where papers did not have an abstract, researchers reviewed a suitable summary or conducted a brief review of the full text.

The first 100 papers were double screened by two members of the research team to ensure consistency. Differences in screening results between researchers were discussed and any differences in interpretations clarified before screening continued.

Full-text screening

The full text of each paper included at the title and abstract screening stage was assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria set out below. Papers were excluded if they did not meet the criteria. Papers were then assessed and scored to identify their relevance to the research questions. The research team also recorded information such as study type, year and country. Full-text screening of both academic and grey literature was conducted using the Covidence platform.

Additionally, papers were scored against the Weight of Evidence (WoE) tool to assess the quality of the research. The WoE analysis is based on a methodology first developed by the EPPI-Centre (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre) and has been applied in the analysis of both quantitative and qualitative research. [footnote 36] The WoE assessment focused on the clarity and accuracy of the paper, appropriateness of methods, and any ethical concerns.

The screening process led to a shortlist of 36 papers. The shortlist was then sent to an academic subject expert, who confirmed that the list reflected their understanding of the research undertaken in this field. Given the low number of papers on this topic, a decision was taken to extract data from all 36 papers which met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All included papers must:

-

Be published after January 2010.

-

Be published in English.

-

Report on research from the UK and/or other specified countries (US, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, Norway and EU countries).

-

Report on at least one recognised research method. The review included a range of methods (e.g. qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies). However, study protocols, opinion pieces and popular media (e.g., blogs, social media feeds and/ or newspaper articles) were excluded.

All included papers must also discuss at least one of the topics below:

-

The existence of loneliness stigma. This includes self-stigma and social stigma.

-

The relationship between loneliness and stigma (including any findings on a causal relationship).

-

Whether some groups (e.g. men/women or younger/older people) are more likely than other to experience loneliness stigma.

-

Wider risk factors for loneliness stigma (e.g. lack of support network, past experiences or being aware of stigma within the community).

-

The impact of loneliness stigma. This could be anything including wellbeing, productivity, social isolation, lower self-esteem.

-

What works in tackling loneliness stigma. This could be any type of intervention, campaign, pilot, trial, scheme, strategy or policy that aims to tackle loneliness stigma, including those that did and did not work.

Papers were excluded which only discussed:

-

The association between loneliness associated with other types of stigma (e.g. HIV or disability).

-

Physical isolation rather than feelings of loneliness.

PRISMA diagram

The following flowchart illustrates the number of papers at each stage of the REA process and how these were filtered down:

Data extraction and analysis

An extraction framework was developed, whereby each row represented one paper and each column represented a theme related to the research questions. The columns were:

-

Short summary of findings relevant to the research questions.

-

Evidence on with the existence of loneliness stigma.

-

Findings on the relationship between loneliness and loneliness stigma.

-

Findings on whether some groups are more likely to experience loneliness stigma than others.

-

Findings on any other risk factors associated with loneliness stigma.

-

Findings on the impact/potential impact of loneliness stigma.

-

What elements of interventions have been successful and why?

-

What elements of interventions have been less successful and why?

-

Any key learnings flagged for future interventions?

-

Are any further interventions suggested by the authors (which have not been trialled)?

-

Are there any suggestions for further research?