Reducing Parental Conflict Programme 2018–2022: An evaluation of the effects of interventions on parental relationships and children

Updated 14 February 2024

August 2023

DWP research report 1039

A report of research and analyses carried out by the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2023.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

This document/publication is also available on our website at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-work-pensions/about/research#research-and-analysis-publications

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published August 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-558-4

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

International evidence shows that when parents are entrenched in conflict that is frequent, intense, and poorly resolved, it is likely to have a negative impact on themselves and their children. Prior to the 2018-22 Reducing Parental Conflict programme, relatively few relationship and parenting interventions had been tested in the UK. Therefore, very little was known about the type of interventions that would work to reduce parental conflict and improve the mental health and wellbeing of children in workless and disadvantaged families living in the UK.

To begin addressing this evidence gap, up to £50 million was allocated to the Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme between 2018 and 2022. Part of the programme involved testing eight interventions across 31 upper tier local authorities in four geographical areas (Contract Package Areas) to build the evidence on what works to help families in conflict.

The 2018–2022 RPC programme was supported by three strands of evaluation:

-

a commissioned evaluation conducted by DWP research partners, IFF Research,

-

an innovative qualitative study which used diaries to follow parents as they participated in RPC interventions,

-

and this report, an in-depth quantitative study to evaluate the efficacy of these interventions, in improving interparental relationships and children’s wellbeing.

Between 2019 and 2022, 6,110 parents, in 3,810 families, were referred to an intervention. Data was collected from participating parents about different aspects of their relationship with the other parent and the wellbeing of their children. Data was collected at four key stages: once before intervention and up to three times after completion of an intervention (immediately after completion, 6 months after completion, and finally, 12 months after completion). The evaluation involved comparing different measures of the interparental relationship and child mental health / wellbeing to estimate the changes observed post intervention. A nonexperimental, before-and-after study design was used, meaning there was no control group with which to estimate the counterfactual (the changes that would have occurred regardless of intervention).

The evaluation found that:

-

On average, parents who participated experienced statistically significant improvements in their relationship with the other parent after they completed one of the interventions tested. Furthermore, for participating parents with a child aged 2 to 17 years old at the point of referral, parents reported on average these children showed statistically significant improvements in their mental health and wellbeing after their parent(s) completed an intervention.

-

Where it was possible to estimate (i.e. where post intervention sample sizes were sufficient), there was no evidence that interparental relationships or child mental health regressed towards pre-intervention levels in the 12 months after completing an intervention.

-

Families that completed high intensity interventions, which were more expensive, showed slightly greater improvements in both interparental relationships and child wellbeing / mental health than families that completed moderate intensity interventions.

-

Sample sizes were sufficient to support intervention level analyses for six of the seven interventions tested; all six interventions showed significant improvements in both interparental relationships and child mental health. On average, parents who completed Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT) experienced greater improvements in interparental relationships and the mental health of their children, compared to parents who completed other interventions. However, at the time of the test, MBT was considered to be the most expensive intervention, and it was not possible to adjust the effect sizes in this report for the cost of interventions.

-

Where both parents participated, greater improvements were demonstrated in interparental relationships and child mental health, though parents participating alone (without the cooperation of the other parent) still showed statistically significant improvements in interparental relationships and child mental health.

-

Working families experienced slightly better outcomes than families where at least one parent was not working; both family types showed significant improvements (of a similar magnitude) in interparental relationships, but working families saw greater improvements in child mental health.

-

Sample sizes were not sufficient to facilitate comparative analyses between specific ethnic groups. However, when analysing ethnic minority and nonethnic minority families, both showed significant improvements in interparental relationships and child mental health after completing an intervention.

This evaluation focused on the effect on families after completing an RPC intervention and did not account for the higher contract price paid per parent for the high intensity interventions. This report, therefore, does not attempt to make any claims about the value for money of RPC interventions, either in terms of the price paid by the DWP under the 2018-22 programme or the actual market cost of these interventions as of 2022/23.

Authors

This report was written by William Brewin and Matthew Garlick from Income, Families and Disadvantage Analysis Division in the Department for Work and Pensions.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted by the Department for Work and Pensions with support from 31 local authorities and 3 interventions providers, Relate, Twin Training and Tavistock Relationships. The analysis relied heavily on data collected by IFF Research Ltd, commissioned by DWP to undertake an independent evaluation of the 2018-22 Reducing Parental Conflict programme.

Particular thanks are owed to Gordon Harold, Professor of the Psychology of Education and Mental Health at the University of Cambridge, for his valuable advice on the evaluation of family relationship dynamics and child-adolescent mental health and development throughout the project.

Finally, thank you to all the parents who participated in this research, for giving up their valuable time to complete lengthy questionnaires and respond to the many evaluation surveys conducted by IFF Research Ltd.

Glossary

Contract Package Area (CPA)

Delivery of RPC interventions took place across 31 local authorities, which were clustered in 4 geographic areas known as Contract Package Areas. These are Westminster, Gateshead, Hertfordshire, and Dorset.

Domestic abuse

Imbalance of power or control in a relationship, and one parent may feel fearful of the other.

Early Intervention Foundation (EIF)

The Early Intervention Foundation was an independent charity established in 2013 to champion and support the use of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes. In 2023 the EIF merged with the What Works Centre for Children’s Social Care to form ‘Foundations’.

Parental conflict

Harmful parental conflict behaviours in a relationship which are frequent, intense and poorly resolved can lead to a lack of respect and a lack of resolution. Behaviours such as shouting, becoming withdrawn or slamming doors can be viewed as destructive. Parental conflict is different from domestic abuse. This is because there is not an imbalance of power, neither parent seeks to control the other, and neither parent is fearful of the other.

Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme

The Reducing Parental Conflict programme is the subject of this evaluation. It aims to help avoid the damage that parental conflict causes to children through the provision of evidence-based parental conflict support, training for practitioners working with families and enhancing local authority and partner services.

Subscale

An academically established measure of a different aspect of the relationship between parents, or a different aspect of the wellbeing / mental health of a child.

(Ex-)partner

The term is used throughout the report where findings are in relation to both intact and separated parents regarding their partner or former partner. Therefore, for intact parents who responded, it refers to their current partner, and for separated parents who responded, they are responding in relation to their former partner.

Chapter 1: Introduction and background information

This chapter provides the background to the 2018–2022 Reducing Parental Conflict programme, with a particular focus on the interventions that were tested between 2019 and 2022.

1.1 Background

Parents play a critical role in giving children the experiences and skills they need to succeed. However, studies have found that children who are exposed to parental conflict can be negatively affected in the short and longer term (Harold et al., 2016).

Disagreements in relationships are normal and not problematic when both people feel able to handle and resolve them. However, when parents are entrenched in conflict that is frequent, intense, and poorly resolved, it is likely to have a negative impact on the parents and their children (Acquah et al, 2017)[footnote 1]. This type of conflict can impact on children’s early emotional and social development, their educational attainment and later employability, limiting their chances to lead happy, fulfilling lives.

The government wants every child to have the best start in life and reducing harmful levels of conflict between parents, whether they are together or separated, can contribute to this. Sometimes separation can be the best option for a couple, but even then, continued cooperation and communication between parents is better for their children.

In response to the evidence of the negative effects of entrenched conflict, between 2019 and 2021, up to £39 million was allocated to the Reducing Parental Conflict programme, with an additional £11 million funding for an extension through to 2022. Eight interventions were tested across 31 upper tier local authorities in four geographical areas (Contract Package Areas) to help families in conflict.

The 2018-22 Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme aimed to minimise the damage that interparental conflict causes to children through the provision of evidence-based parental conflict support, training for practitioners working with families and enhancing local authority and partner services. The programme sought to address conflict between parents where there was no evidence of domestic violence or abuse.

The eight interventions tested and evaluated between 2019 and 2022 were chosen following consultation with a subject matter expert. Local authorities were also consulted on which interventions would be suitable and would work alongside other local support available for families. As the table below shows, these interventions targeted a range of family types; some were for intact couples, some were for separated or separating parents, and others could support both family types. One intervention was specifically for parents with children aged between 7 and 11 years old.

Each intervention involved a combination of relationship and parenting support. Generally, Mentalization Based Therapy, Within My Reach, Enhanced Triple P and Family Transitions Triple P focused more on relationship problems between parents. The rationale was that improved interparental relationships would benefit children via improved parent-child relationships, which reduce conduct problems and improve emotional adjustment. By contrast, Incredible Years, 4Rs and 2Ss, Family Check-up and Parenting When Separated focus more on parenting practices, which have a more direct effect on children’s wellbeing and emotional adjustment. Further details of the interventions can be found in table 1.1 below.

Evaluation was central to the RPC programme, with findings designed to build the UK-specific evidence base and contribute to the wider international evidence on what works to reduce parental conflict and improve outcomes for children. The aim was for this evidence to be used by local authorities and their partners to embed successful parental conflict focused practice and service organisation into their services for families. The evaluation design aligned with the three main strands of the programme:

-

integration of parental conflict focused practice and services into local area family services across England,

-

training for frontline family practitioners and other professionals who come into regular contact with families, to help them identify parental conflict and in some cases to deliver support to help reduce it, and

-

interventions for parents in conflict, commissioned centrally by DWP to find out which interventions work best to improve interparental relationships and child outcomes.

The analyses covered in this report focuses specifically on the interventions strand by measuring changes in various aspects of parents’ relationships with each other and the wellbeing / mental health of their children after parents completed one of the interventions on offer.

Table 1.1 – Details of the interventions tested

Note: Three third party providers (Relate, Tavistock Relationships and Twin Training) delivered across four Contract Package Areas: Dorset, Gateshead, Hertfordshire, and Westminster. [Refer to Annexe 1.1 for the full list of local authorities covered by each CPA]

| Intervention Name | Delivery structure | Intervention aims | Intact or separated parents | Provider and Contract Package Areas | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mentalization Based Therapy – Parenting Under Pressure | 10 sessions of therapeutic work, one practitioner delivers sessions to intact couples; with separated couples each parent completes sessions with a separate practitioner. In some cases, parents complete the final session together with both practitioners. | Aims to help separated or intact couples experiencing high levels of interparental conflict to gain more perspective in order that they can start to put the needs of their children first. It is based on a model which comprises an initial phase of preparation and assessment, followed by sessions that target both parents’ capacity for reflective thought and challenges the assumptions parents make about each other’s intentions behind their actions. | Both | − Gateshead (Relate) − Hertfordshire (Tavistock) | High |

| Triple P Family Transitions | 5 2-hour sessions delivered individually or in groups of c.8 parents over 5-13 weeks. | The intervention focuses on developing skills to resolve conflicts with former partners and learning how to cope positively with stress. These 5 sessions are delivered in conjunction with Triple P Level 4 (approximately 10 hours). | Separated | − Dorset (Twin Training) − Westminster (Tavistock) | High |

| Incredible Years ADVANCED | 12-20 sessions as part of the ‘Basic’ course, with an additional 9- 11 session for ‘Advanced’ (average of up to 20 weeks) | The focus is on parents’ and children’s communication and problem-solving skills, knowing how and when to get and give support to family members and recognising feelings and emotions. The Advanced programme focuses on parents’ interpersonal issues such as effective communication and problem-solving skills, anger, depression management, and ways to give and get support. | Both | − Dorset (Twin Training − Gateshead (Relate) | High |

| Enhanced Triple P | Four modules delivered to families in 3-8 individualised consultations. Parents attend 8-12 hours consultation individually, over 8-15 weeks. | This is a targeted selective intervention, which aims to address family factors that may impact upon and complicate the task of parenting, such as parental mood and partner conflict, and problem child behaviours. Parents completing Enhanced Triple P also need to complete a Level 4 Triple P parenting programme (approximately 10 hours). | Both | − Westminster (Tavistock) | High |

| Family Check-up | 3-4 sessions, each lasting 50-60 minutes | This is a strengths-based, family-centred intervention that motivates parents to use parenting practices to support child competence, mental health, and risk reduction. The intervention is delivered in two phases. The first is a brief, three-session intervention based on motivational interviewing. The second involves the delivery of Everyday Parenting, a family management training intervention that builds parents’ skills in positive behaviour support. | Both | − Dorset (Twin Training) − Westminster (Tavistock) | Moderate |

| Parenting When Separated (Parents Plus) | Six 2.5-hour sessions, delivered over a six-week period by two practitioners to groups of 12 parents | This intervention highlights practical steps parents can take to help their children cope and thrive as well as coping successfully themselves, where the parents are preparing for, going through, or have gone through separation or divorce. | Separated | − Gateshead (Relate) − Hertfordshire (Tavistock) | Moderate |

| Within My Reach | 15 sessions, each lasting one-hour | This is a targeted selective intervention, for low-income single parents, who may or may not be in a relationship. The intervention therefore targets relationship outcomes in general, rather than focusing on parenting or parental conflict. It covers 3 key themes: Building Relationships, Maintaining Relationships and Making Relationship Decisions | Separated | − Dorset Twin Training) − Westminster (Tavistock) | Moderate |

| 4Rs 2Ss Strengthening Families Programme [RECEIVED NO REFERRALS] | 16 sessions delivered weekly to groups of 12-20 parents. | This intervention is targeted at families that have a child between 7 and 11 years old who is diagnosed with a disruptive behaviour disorder. It is designed to support family-level influences on disruptive child behaviour disorders, as well as to target factors that potentially impact child mental health service use and outcomes (e.g. parental stress, use of emotional and parenting support resources, and stigma associated with mental health care). | Both | − Hertfordshire (Tavistock) | High |

For more information on these interventions, please see the Early Intervention Foundation commissioner guide for reducing the impact of interparental conflict on children.

Chapter 2: Evaluation aims and research questions

This section sets out the main aims of the study, and the primary, secondary and tertiary research questions that the evaluation of the interventions strand of the programme seeks to address.

2.1 Evaluation aims

A key aim of the 2018-22 RPC programme was to build UK-specific evidence on the types of support that improve interparental relationships, parenting and child outcomes, especially for for workless and other disadvantaged families. Interventions of the kind tested under the programme had been tested over the previous decade, mainly in the United States EIF, 2016)[footnote 2], but no previous comparable UK studies had been conducted on this scale, and previous studies usually focused on middle-income families. The aim was therefore to help shape future UK government policy decisions around the provision of relationship and parenting support for workless and other disadvantaged families where domestic violence or abuse was not a factor.

2.2 Research questions

The analyses covered in this report are designed to answer the following primary, secondary and tertiary research questions:

2.2.1 Primary research questions

The main evaluation aim is met by answering the following primary research questions:

-

To what extent did parents report improvements in interparental relationships after attending an intervention?

-

To what extent did parents report improvements in their children’s mental health/wellbeing after attending an intervention?

-

Which interventions were associated with the greatest improvements in interparental relationships and children’s mental health?

2.2.2 Secondary research questions

In support of the primary research questions above, the analyses herein seek to answer the following secondary research questions:

-

To what extent did intact and separated families experience different levels of improvement in interparental relationships and children’s wellbeing?

-

To what extent did parents participating alone experience different levels of improvement in interparental relationships and children’s mental health to those participating together?

-

To what extent did families where both parents work experience different levels of improvement in interparental relationships and children’s mental health to those where at least one parent is out of work?

-

To what extent did ethnic minority families experience different levels of improvements in interparental relationships and children’s mental health, when compared non-ethnic minority families?

-

To what extent did younger children experience different levels of improvements in their mental health, when compared with adolescents?

2.2.3 Tertiary research questions:

In addition to the above core research questions, the report includes analyses exploring parent engagement and retention as they participated in the interventions to help identify difficulties and challenges that any organisations involved in delivering these interventions in the future should remain alert to:

- Were parents from different subgroups (e.g. those participating alone) more or less likely to drop out of an intervention early?

2.3 Outline evaluation timeline

Although the first RPC programme started in 2018, the interventions test officially began in April 2019. The first referrals to interventions were made in May 2019, with referrals ceasing on 31 March 2022. This final cohort of parents completed interventions in July 2022 with data collection ceasing in September 2022.

Delivery was disrupted by the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic, which initially interrupted delivery and then permanently changed the way that most parents experienced the interventions. Though all the interventions were designed and developed to be delivered face to face, all interventions were experienced online using software such as Zoom from April 2020 until face-to-face delivery was resumed in October 2021. Thereafter, parents were usually given a choice about whether to participate online or in-person at home or at a venue. The result of this is that 80 percent of parents participated virtually/online.[footnote 3]

The pandemic also had several important effects on families. Emerging evidence suggests different impacts on relationship distress for families with/without children and those experiencing loss of income. Similarly, there is evidence to show that school closures, and both the imposition and relaxation of social distancing, affected children differently depending on factors such as neurodiversity (see the Oxford CoSpace Study, 2023 – http://cospaceoxford.org/about/).

These impacts present risks to the internal validity of this part of the evaluation, which are discussed in Chapter 3. Mitigation of these risks is also discussed.

Chapter 3: Methodology

This section explains the study design and methodology used to evaluate whether parents accessing one of the interventions experienced improvements in their relationship with the other parent and whether the wellbeing/mental health of at least one of their children improved.

3.1 Study design

Each of the interparental relationship measures was chosen because they are associated with emotional development and mental health and long-term outcomes for children, these outcomes are highlighted in the theory of change for the eight tested interventions.[footnote 4]

3.1.1 Relationship measures

The questionnaires focused on the two main outcomes that the interventions are designed to improve, interparental relationships and child mental health. To measure changes in the interparental relationship, the evaluation used nine academically established measures, each assessing different aspects of the relationship between intact or separated parents, hereafter referred to as ‘subscales’. Some of these subscales have been used in the study of relationships since the early 1980s.

As separated parents have different relationship issues to intact parents, the measures used were different for parents who were together (intact) and parents who were not together (separated) at the point of referral, so the analysis for these parent groups was conducted separately.

The selected subscales for intact parents were chosen from the ‘Dyadic Adjustment Scale’, ‘the Iowa Youth and Families Warmth-Hostility Subscale’, and the ‘O’Leary Porter Hostility Scale’. The selected measures for separated parents were chosen from Ahrons (1981)[footnote 5], Kramer & Washo (1993)[footnote 6], and Morrison & Coiro (1999)[footnote 7]. The full list of subscales, and corresponding sources, can be found in Annexe item 3.2. These subscales were chosen because they closely matched the components of relationships that interventions of the type tested were/are designed to target (i.e. they focus on aspects of relationship quality that indicate relationship distress and areas of parental conflict which the evidence suggests are harmful to children, especially if they take place in front of the children).

The interparental relationship questions were asked in four questionnaires:

-

the pre-intervention questionnaire, reported at the point of referral before parents attend an intervention

-

the post-intervention questionnaire, reported immediately following the completion of an intervention

-

a post-intervention questionnaire, reported 6 months following the completion of an intervention

-

a second post-intervention questionnaire, reported 12 months following the completion of an intervention

The 6 relationship measures used for separated parents were:

-

conflict when communicating (i.e. anger and argumentative behaviour between parents)

-

frequency of conflict (i.e. how often parents argue)

-

breadth of conflict (i.e. the range of issues argued about)

-

co-parenting support (i.e. helping each other as parents)

-

satisfaction with custody arrangements

-

co-parental communication (i.e. communicating well about the children)[footnote 8]

The four relationship measures for intact parents were:

-

relationship warmth (i.e. care, support and understanding)

-

hostility (i.e. anger and argumentative behaviour between parents)

-

relationship satisfaction (i.e. happiness within relationship)

-

overt hostility (i.e. arguing in front of their children)

-

relationship agreement (i.e.’ having similar relationship values, goals, and beliefs)[footnote 9]

Details of the specific questions asked, and associated scoring system, for both separated and intact parents for the relationship measures can be found in Annexe item 3.3.

3.1.2 Measures of child behaviour and wellbeing

The second main area of outcome analysis focused on children’s wellbeing and mental health using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The SDQ is a brief emotional and behavioural screening questionnaire for children and young people between 2 and 17 years old. The SDQ comprises 25 questions on the psychological attributes of children, divided between 5 subscales. The questions asked in relation to 2- to 4-year-olds differ slightly to the questions asked in relation to children aged 5 or more, so the analysis of these age groups was conducted separately.

SDQ questions are commonly used by researchers, clinicians, and educationalists and are typically asked of: parents in relation to their children; teachers in relationship their pupils; and directly to children (older ages groups only). This evaluation involved only parents reporting about their children (parent report) before and after their parents participated in one of the interventions.

The SDQ questions were asked to parents in three questionnaires:

-

the pre-intervention questionnaire, reported before the parents attend an intervention

-

a post-intervention questionnaire, reported 6 months after the completion of an intervention

-

a second post-intervention questionnaire, reported 12 months after the completion of an intervention

The five SDQ subscales were/are:

-

emotional problems

-

conduct problems

-

hyperactivity

-

peer problems

-

prosocial behaviour

The SDQ also allows for a Total Difficulties Score, calculated by summing scores from all the scales except prosocial behaviour.

Details of the specific questions asked, and associated scoring system, for the child wellbeing measures can be found in Annexe 3.4.

Below is a flow chart that details when each questionnaire is asked, for both interparental relationships and child wellbeing measures:

| Data collection | (1) Screening & referral | (2) Pre-intervention assessment | RPC intervention | (3) Post-intervention assessment | (4) Follow-up surveys +6 months | (4) Follow-up surveys +12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus of data collection | Parental conflict | Child behaviour | RPC intervention | Parental conflict | Child behaviour & Parental conflict | Child behaviour & Parental conflict |

| Questionnaires | Pre intervention questionnaire (at referral) | Pre intervention questionnaire (before starting) | RPC intervention | Post intervention questionnaire (upon completion) | Post intervention questionnaire (6 months after completion) | Post intervention questionnaire (12 months after completion) |

Each parent answered the questionnaires separately. However, as questionnaires were not always completed by both parents, the analysis was conducted at family level so that responses relating to the same child were not duplicated. Where only one parent responded, this was taken to be the family response. Where both parents responded, the family score was the average of the two responses.

3.1.3 Sample size targets

Each of the four CPAs provided an estimate of the number of eligible participants that they expected to refer to an RPC intervention. They also estimated the proportion of those referrals that would start an intervention over the initial RPC programme lifetime (2019-2021, before the programme was extended by one year). These estimates assumed an even split between high and moderate intensity interventions would be achieved in each CPA.

Table 3.0 outlines the forecast number of referrals, starts and completers expected in each CPA:

Table 3.0: Forecast programme volume of parents

| Westminster | Hertfordshire | Gateshead | Dorset | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred | 2,400 | 3,150 | 2,830 | 1,630 | 10,010 |

| Retention rate (referral to start) | 75% | 60% | 75% | 65% | - |

| Start | 1,800 | 1,890 | 2,120 | 1,060 | 6,870 |

| Retention rate (start to complete) | 66% | 69% | 80% | 70% | - |

| Complete | 1,190 | 1,300 | 1,700 | 740 | 4,930 |

The minimum acceptable sample size should be large enough that the statistical power would be adequate for all statistical tests relating to the primary research questions. The projected sample sizes were deemed large enough to generate statistically significant results, using the uncovered effect sizes in previous studies to estimate the minimum sample.

3.2 Evaluation methodology

This study employed a non-experimental before-and-after evaluation design, commonly used when measuring outcomes of a group of participants before attending an intervention, and again afterwards. A before-and-after design assumes that, in the absence of the intervention, the outcomes of the treatment group would have remained unchanged between the pre and post intervention periods. Therefore, any changes in the outcomes are attributed to the effect of the interventions (Before-and-after study: comparative studies - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)) .

The evaluation involved comparing the mean scores across the range of interparental relationship and child wellbeing subscales described above, before and after parents completed one of the interventions tested.

A before-and-after design was deemed a suitable evaluation design because population level relationship distress and SDQ scores remain relatively stable in normal times. Although the option of delaying support for some parents to create a control group to estimate the counterfactual was considered, the uncertainty around programme volumes and the ethical issues around withholding support from parents and children in need created an overall lack of appetite for this approach, especially from the providers being contracted to deliver the interventions.

Although this type of evaluation design is subject to threats to internal validity (as discussed below), given the paucity of UK-based evidence for these types of relationship and parenting interventions, it should provide important initial evidence on intervention effectiveness, thus fulfilling a key aim of the RPC programme: to build the UK evidence base for what improves interparental relationships and parenting. Prior to this study the main evidence base relied upon non-UK studies which, due to the pitfalls of international policy transfer,[footnote 10] do not provide reliable evidence for what works in the UK.

3.2.1 Threats to internal validity

There are several threats to internal validity associated with before-and-after studies, outlined in the table below. The threats that are most relevant to this study are the history, regression-to-the-mean and drop-out threats. Each of these was considered, and attempts were made to mitigate these risks where possible.

Table 3.1 – Internal validity threat analysis

| Threat to internal validity | Description of threat | RAG rating for this study |

|---|---|---|

| History | Some other influential event(s) which could affect the outcome, occurs during the intervention. | Amber |

| Instrumentation/reporting | Validity of measurement method changes over the course of the intervention. | Green |

| Regression-to-the-mean | Change in outcome measure might be explained by a group with a onetime extreme value naturally changing towards a normal value. | Red |

| Testing | Taking measurement (e.g. through the questionnaires) could affect the outcome. | Amber |

| Placebo | Intervention could have a nonspecified effect on the outcome, independent of key intervention components. | Green |

| Hawthorne effect | Parents’ awareness of being studied could affect their behaviour and therefore the outcome, independent of key intervention components. | Amber |

| Maturation | Intervention group develops in ways independent of the intervention (e.g. aging, increase experience, etc.), possibly affecting the outcome. | Green |

| Drop-out | The overall characteristics of the intervention group change due to some participants dropping out, possibly affecting the outcome. | Amber |

Adapted from: Robson et al (2001)[footnote 11]

History

A history threat arises when a phenomenon external to the intervention could affect the outcome and occurs between the ‘before’ and ‘after’ measurements are taken. Before the study, this risk was assumed to be low. However, the coronavirus pandemic occurred during the lifetime of the study. Therefore, any effect of the pandemic on relationships between parents presents a history threat. The 2023 Oxford Co-Space study suggests that in relation to children:

Overall, both parent/carer reported behavioural difficulties and restless/attentional difficulties consistently increased through March to June and have decreased since July [2020]. Reported emotional difficulties were relatively stable through March to June, but have also decreased over time after the lockdown was eased in June [2020].

For children whose parents completed an intervention, 17% of referrals occurred before the pandemic, 15% were referred between 20 March 2020 and 1 September 2020 and 65% were referred once the majority of schools had reopened. To estimate whether those participants referred during the lockdown period, as defined in the CoSpace study, experienced different levels of wellbeing, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was conducted to determine whether the child wellbeing scores were statistically similar for children referred during lockdown to those referred either before lockdown, or after schools reopened. For total difference score in all three child wellbeing surveys (pre-intervention questionnaire, 6- and 12-month postintervention questionnaires), the mean score of each group was not statistically different. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the effect of lockdown and the resultant history threat on the SDQ scores of children in this study is small. Annexe 3.5 details the findings of the ANOVA tests.

Regression-to-the-mean

A regression-to-the-mean threat typically arises when the basis for choosing the intervention group is a greater need for the intervention. The RPC programme targeted families experiencing high levels of conflict, so the regression-to-the-mean risk was high. Providing RPC interventions to families with higher-than-average levels of conflict meant that families may be selected when conflict was at its worst, and that it may regress towards the average level of conflict seen in the wider population, regardless of effect of the intervention. The same principle applies to child wellbeing, where children experiencing greater behavioural and emotional difficulties typically improve over time without intervention (youth in mind, 2009). There was no natural counterfactual, so it was not possible to mitigate the regression-to-the-mean threat.

Testing

A testing threat to internal validity exists when taking a before measurement may affect the outcome evaluated in the study. This may exist in the RPC programme, where parents were asked detailed questions about their interparental relationship and their children’s wellbeing before attending an intervention. This may facilitate improvements in relationships and wellbeing by raising awareness about parental conflict and its impact on children. To assess the testing risk definitively, an experimental or quasi-experimental design is necessary. However, this risk was assumed to be small because interventions such as MBT include a pre-assessment as part of the provision as standard. It is therefore reasonable to include any pre-test questionnaire effect in the overall effect of the intervention.

Hawthorne effect

The Hawthorne Effect arises when the act of involving researchers influences the evaluated outcomes. The act of being observed or the research participant knowing they were part of a test might modify the behaviour of participating parents or those delivering the interventions to enhance the likelihood of a positive outcome. However, throughout the test period, researchers’ contact with parents was limited, and surveys and qualitative interviews with parents were conducted ex-post. Furthermore, participant agreements that were signed by parents before referral made no mention of them being part of a trial or test.[footnote 12] Parents simply agreed for their information to be collected for DWP and its partners to evaluate the success of the programme.

Except for the follow-up surveys, conducted by IFF Research, the other questionnaires were completed as routine by participants, either as part of the screening, referral, induction and exit processes, with the assistance of a trained practitioner or alone.

However, the outcomes of 45 parents who participated in Diary Research,[footnote 13] conducted by DWP researchers whilst they went through interventions were more likely to be subject to the Hawthorne Effect because contact with the researcher was relatively frequent, with parents prompted to reflect on recent sessions and family life and make appropriate uploads made to a diary app. These parents also participated in two one-hour interviews, once near the time of referral and again at the end of the intervention.

In summary, whilst some Hawthorne Effect may have existed, especially for the 45 parents participating in the diary research, its overall influence over the outcomes measured by this part of the evaluation was considered small.

Drop-out

A drop-out threat arises when the characteristics of the intervention group alter because people leave the study without completing it. As a result, those completing the intervention differ from those who drop out, thereby introducing selection bias. Fifty-six per cent of referrals to RPC interventions in this test dropped out before completing an intervention. To assess the risk of drop-out threat to the evaluation, the characteristics of parents who completed interventions and those who did not complete were compared. Annexe 3.6 shows there was little difference in the characteristics of both groups. The responses to the ‘before’ surveys were only included in the study if an ‘after’ response was also present for that family, so it was not possible to account for unobservable factors that made people drop-out. If this would have not allowed for a sufficient sample size, an Intention-To-Treat (ITT) approach would have been explored. This would have allowed the ‘before’ responses of drop-outs to be included in the analysis, provided that no systematic differences were identified between those that completed an intervention and those that dropped out without completing.

All other threats to internal validity in Table 2.1 were considered but not determined to be relevant to the evaluation of the programme.

Overall, the chosen evaluation design cannot account for the possibility that something other than the intervention may have caused a change (Before-and-after study: comparative studies - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)). The non-experimental before-and-after approach is the primary reason that the regression-to-the-mean and history threat cannot be completely mitigated. Experimental methods, such as Randomised Control Trials (RCTs), are thought to be the most reliable evaluation method. An RCT was considered in the implementation of this evaluation but not deemed to be viable due to ethical and delivery considerations.

3.2.2 Before-and-after method & statistical tests

Statistically significant differences between the before-and-after measures were determined using paired t-tests for each relationship and child wellbeing subscale. Paired t-tests determine whether the mean difference between the ‘before’ score and the ‘after’ score for each family is zero or not. A p-value of 0.05 or lower is considered to be statistically significant.

For comparisons between different subgroups (e.g. participating alone or participating together) a two-tailed, two sample t-test was employed to determine whether the mean difference between the score for each family type was zero or not. As with paired t-tests, a p-value of 0.05 or lower demonstrates a statistically significant difference. In this evaluation significance is reported at the 1% and 5% level.

This evaluation required testing the effect of an intervention against multiple outcome variables. To correct for the increase in probability that one of the apparent outcomes could have occurred by chance, a Bonferroni correction was applied, which divides the desired significance by the number of outcomes. This means that any conclusions around any differences observed pre and post intervention are more conservative.

Statistical tests are performed on the raw scores, not the standardised scores. A standardised measure of effect size, Cohen’s d, was used. It is the difference between two means, measured in standard deviations. This is a commonly used measure of the effect size of a treatment or intervention, where subscales are scored differently. Cohen’s d allows for comparison across different relationship and child wellbeing measures, and different interventions. It also allows the results of this study to be compared with estimated effect sizes found in other studies of these types of intervention. Cohen’s d has a theoretical range of 0 - ∞, but when interpreting the effect size of interventions, it is generally accepted that:

| Effect size | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|

| Small | 0.20 |

| Medium | 0.50 |

| Large | 0.80 or greater |

Cohen’s d values are not considered robust when the sample contains fewer than 50 observations. Where this was the case, Cohen’s d was not reported.

Effect sizes are reported for the ‘before’ and first ‘after’ period. For both relationship and child wellbeing measures, pre-intervention questionnaire answers are compared with post-intervention questionnaire answers. The post-intervention questionnaires, conducted via two telephone surveys by IFF Research (IFF), were used to determine whether any changes in interparental relationships and child outcomes were sustained for up to 12 months following the completion of an intervention. Paired ttests were used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the three post-intervention measures for each interparental relationship subscale used. The same test was also used to compare differences between the two post-intervention measures of child wellbeing.

3.3 Key programme issues and events

This section summarises several key events during the lifetime of the trial that had an impact on data quality, integrity, or completeness, and, in some cases, the sample sizes that were achieved (either as a whole or for individual interventions. Although these events help show how the test was implemented, not all implementation issues are mentioned; the focus is on issues which had an impact on the evaluation.

3.3.1 Outline timeline of events

Table 3.2 provides a chronological account of all key issues during the delivery of the test that had a significant impact on the evaluation. Annexe 3.8 details the key implementation issues identified during this evaluation.

Table 3.2: A summary of key implementation issues

| Key event | Date |

|---|---|

| Go-live date of the first provider contract | May 2019 |

| Date after which all provider contracts were live | July 2019 |

| Eligibility criteria relaxed to allow a higher proportion of working parents/lower proportion of disadvantaged families | October 2019 |

| Allowing parents assessed as in high intensity conflict to start moderate intensity interventions | Various reasons from December 2019 |

| Coronavirus: face-to-face delivery paused | March 2020 |

| Pre-intervention questionnaires and parental relationships post-intervention questionnaires issued via PDF | February – October 2020 |

| Virtual delivery established: referrals resumed | April 2020 |

| MS Excel database export/ingest problems | 2019 – Jan 2021 |

| Incredible Years eligibility criteria relaxed | March 2021 |

| Programme extended by 1 year | April 2021 |

| Reluctance of some parents to provide a name and DoB of their children on the pre-intervention questionnaire | Identified/addressed in June 2021 |

| Option to offer FTF intervention resumed | October 2021 |

3.3.2 Accounting for implementation issues

Each of the implementation issues that affected the integrity of the data was accounted for in this evaluation, by excluding questionnaire responses to subscales that were corrupted, and questionnaires were only included where all answers to questions were recorded in full for the relevant analysis. This reduces the number of questionnaires used in the analysis and is the reason that the base population is not the same for every strand of analysis in this report. However, it greatly improves the reliability of the results and allows confidence in the findings of this evaluation to be maintained.

Chapter 4: Analysis and findings

This section presents and explains the findings in relation to the primary and secondary research questions outlined in section 2.2 above. The tertiary research question is addressed separately at the end of this section. Each research question is answered directly below, before explaining the findings in detail.

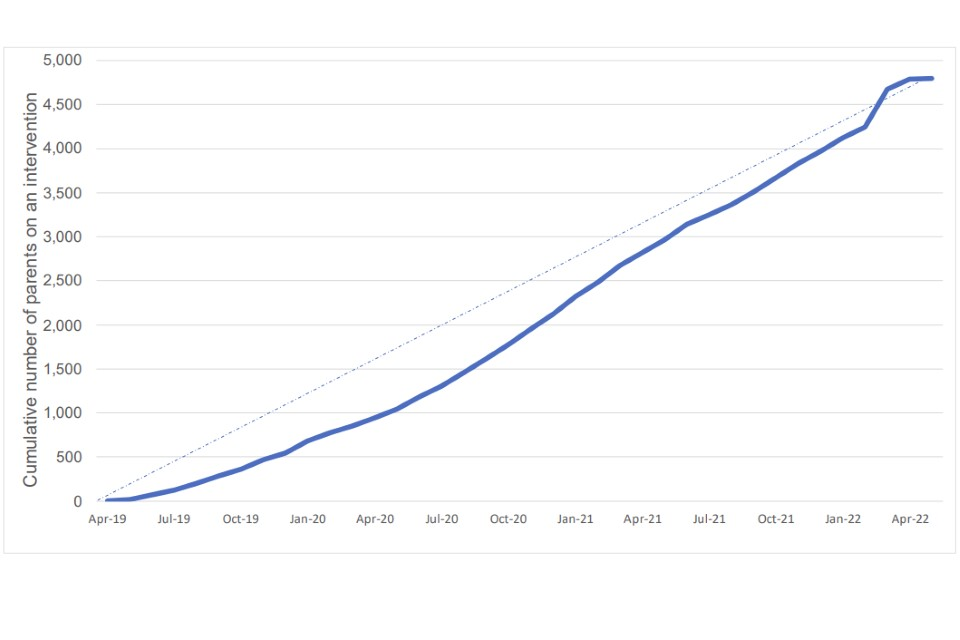

During the tests, 6,110 parents (in 3,810 families) were referred to an intervention; 4,800 parents (in 3,000 families) started an intervention; and 2,700 parents (in 1,690 families) completed an intervention. 880 parents responded to a survey conducted 6 months after they completed an intervention, 370 of whom responded to a second survey conducted 12 months after completion. The analysis reflected in the three reports is based on research with these parents, bringing both parents responses together, wherever possible. Annexe 4.0 outlines the number of parents, and families, that were referred to, started, and completed an intervention in each CPA/subgroup. Annexe 4.0 also contains the cumulative number of parents starting an intervention through time, and a flow chart depicting the attrition rate throughout the programme lifetime.

Notes to aid understanding of the charts

The scores assigned to each relationship measure were scaled differently, with different absolute maximum and minimum scores. To compare fairly across relationship measures, all scales were standardised on a scale between 0 (zero) and 1 (one). 1 represents the maximum possible score for that measure, for example, arguing all the time, whilst zero would represent never arguing. The same approach was taken for the SDQ measures of child wellbeing/mental health.

Mean scores are reported in this section, however not all families experienced improvements, and some experienced greater improvements than the average. This variation is expected, and further details of the experiences of individuals can be found in the diary research.

4.1 To what extent did parents report improvements in interparental relationships after attending an intervention?

On average, both separated and intact parents reported statistically significant improvements in interparental relationships after attending an intervention, with medium-large improvements seen across the majority of relationship measures.

4.1.1 Separated parents

Figure 4.1 shows, for separated families, the mean scores for each relationship measure at the pre-intervention questionnaire, post-intervention questionnaire, and both the 6- and 12-month post-intervention questionnaires. For the precise figures for this chart, see Annexe 4.1.

Figure 4.1: Relationship changes for separated parents

| Measure | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | Immediately after intervention | 6 months after completion | 12 months after completion | |

| Conflict when communicating | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| Frequency of conflict | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Breadth of conflict | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Co-parenting satisfaction | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| Satisfaction with custody arrangements | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.46 |

Analysis of the outcomes for the 568 separated families (for all 6 interventions aimed at separated parents combined) that completed both the pre-intervention questionnaire and the post-intervention questionnaire between January 2019 and May 2022 showed:[footnote 15]

-

improvements across all 5 relationship measures for separated parents, significant at the 1% level

-

medium-large reductions in the frequency and breadth of conflict, and conflict when communicating

-

small-medium sized improvements in co-parenting support, satisfaction with custody arrangements and communication

Table 4.1 (below) outlines the effect size for each separated parent relationship measure, comparing the pre intervention questionnaire with the first post intervention questionnaire.

Table 4.1: Effect sizes for each relationship measure (separated parents)

| Relationship measure | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|

| Conflict when communicating | 0.71 |

| Frequency of conflict | 0.74 |

| Breadth of conflict | 0.63 |

| Co-parenting support | 0.22 |

| Satisfaction with custody arrangements | 0.23 |

This illustrates that after completing an intervention, separated parents’ relationships improved across the full range of measures used. These improvements were statistically significant at the 1% level, meaning that it is 99% likely that this result would not occur if there was no change in interparental relationships. The magnitude of change was smaller for co-parenting support and satisfaction with custody arrangements because these subscales are traditionally less responsive to change and require a mutual change in the relationship between parents (i.e. the behaviour and views of both parents needs to shift).

214 separated families completed a 6-month post-intervention questionnaire. Of these, 105 also completed a 12-month post-intervention questionnaire. Analysis of these responses showed:

-

For all 5 relationship measures, there was no statistically significant regression towards pre intervention levels of interparental conflict both 6 and 12 months after the intervention.

-

Frequency and breadth of conflict showed further improvements in the 6 months following an intervention (significant at the 1% level). These subscales also show further improvements up to 12 months after an intervention (significant at the 5% level).

-

Co-parenting support also exhibited improvements in the 6 months following an intervention (significant at the 1% level).

-

Satisfaction with custody arrangements showed improvements in the 6 months following an intervention (significant at the 5% level).

The analysis of separated parents up to 12 months after completing an intervention suggests that improvements in interparental relationships seen immediately after intervention were either sustained at the same level, or further improvements were made after the 6-month point. This is in line with the theory of change, where improvements in interparental relationships often take time to be fully consolidated; with parents needing time to build on the support and advice received via the intervention. This is especially true of custody arrangements, which may take time to broker and for changes to be implemented.

4.1.2 Intact parents

Figure 4.2 shows, for intact families, the mean scores for each relationship measure at the pre-intervention questionnaire, post-intervention questionnaire, and both the 6- and 12-month post-intervention questionnaires. For the precise figures for this chart, see Annexe 4.1.

Figure 4.2: Relationship changes for intact parents

| Measure | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised relationship score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | Immediately after intervention | 6 months after completion | 12 months after completion | |

| Relationship warmth | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.41 |

| Hostility | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| Overt Hostility | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

Analysis of the outcomes for the 390 intact families (for all five interventions aimed at intact parents combined) that completed at both the pre-intervention questionnaire and the post-intervention questionnaire between January 2019 and May 2022 showed:[footnote 16]

-

medium-large improvements for all 4 relationship measures for intact parents, significant at the 1% level; and

-

greater improvements, on average, for intact families when compared with the effect sizes for separated parents.

Table 4.2 (below) outlines the effect size for each intact parent relationship measure, comparing the pre intervention questionnaire with the first post intervention questionnaire:

Table 4.2: Effect sizes for each relationship measure (intact parents)

| Relationship measure | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|

| Relationship warmth | 0.70 |

| Hostility | 0.69 |

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.73 |

| Overt hostility | 0.77 |

The findings demonstrate that after completing an intervention, intact couples’ relationships improved. It is 99% likely that this result would not occur if there was no change in interparental relationships. The effect sizes for all relationship measures for intact parents were broadly similar and expressed a lower variance than the measures used for separated parents, which means there was more consistent improvements across the subscales for intact parents.

167 intact families completed the 6-month post-intervention questionnaire. Of these, 79 families also completed the 12-month post-intervention questionnaire. Analysis of these responses showed:

-

for all 4 relationship measures, these improvements were sustained for up to 12 months after completion of an intervention – i.e. there was no statistically significant regression towards pre-intervention levels of interparental conflict

-

the overt hostility measure showed further improvements up to 6 months after completing an intervention (significant at the 1% level), which was then sustained in the subsequent 6 months

-

relationship satisfaction and hostility showed further improvements up to 6 months after completing an intervention, though this was not significant at the 5% level

4.2 To what extent did parents report improvements in their children’s wellbeing after attending an intervention?

On average, the parents who completed an RPC intervention reported improvements in their children’s mental health and wellbeing, with small-medium, statistically significant, improvements seen across the majority of SDQ measures.

The parents of 424 children from different families completed both the preintervention questionnaire, and the first post-intervention questionnaire (reported 6 months after completing an intervention). The parents of 2-4-year-old and 5-17-yearold children were asked different versions of the SDQ, so the analysis was carried out separately for each age group.

Boe et al. (2016)[footnote 17] investigated the internal consistency of SDQ scales to identify any difficulties associated with analysing the five individual subscales that make up the SDQ separately. Annexe item 4.2 details the internal consistency tests carried out for this study, to determine how well related questions within each subscale are. In summary, these show that, in this study, all subscales exhibit an acceptable level of reliability and, as such, can be interpreted individually as well as together through the total difficulties score.

4.2.1 5-17-year-olds

Figure 4.3 shows, for children aged 5-17, the mean scores for each child wellbeing measure at the pre-intervention questionnaire, and both the 6- and 12-month postintervention questionnaires. The dotted line depicts the national average score for children aged 4-15 in Britain (Meltzer et al., 2000). For the precise figures for this chart, see Annexe 4.1.

Figure 4.3: Wellbeing changes for children aged 5-17 years old

| Strengths and Difficulties measure | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 6 months after completion | 12 months after completion | |

| Emotional problems | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.33 |

| Conduct problems | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| Peer problems | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Pro-social behaviour (lack of) | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| Total difficulties score | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

Analysis of the outcomes for the 350 children aged 5-17 (for all interventions combined) who completed at least the pre-intervention questionnaire and the 6-month post-intervention questionnaire between January 2019 and May 2022 showed:

-

Initially, the children of parents participating in RPC interventions exhibited much greater difficulties than the national average across the full range of scales that make up the SDQ. These difficulties fell after the intervention was delivered but remained above the national average. [footnote 18]

-

Improvements across all 5 measures used in the SDQ and reductions in total difficulties overall, significant at the 1% level.

-

Medium-sized reductions in emotional and conduct problems, as well as total difficulties scores.

-

Small (but significant) reductions in hyperactivity and peer problems, and small (not significant) improvements in prosocial behaviours.

Table 4.3 outlines the effect size for each child wellbeing measure, for 5-17-year-old children, comparing the pre-intervention questionnaire with the first post-intervention questionnaire:

Table 4.3: Effect sizes for each SDQ measure (5-17-year-olds)

| Child wellbeing measure | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|

| Emotional problems | 0.50 |

| Conduct problems | 0.37 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.22 |

| Peer problems | 0.23 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 0.17 |

| Total difficulties | 0.48 |

The findings demonstrate that after the parents completed an intervention, children aged between 5 and 17 years old showed wellbeing improvements across the full range of SDQ measures. It is 99% likely that this result would not occur if there was no change in children’s wellbeing. The effect sizes range from 0.17 to 0.5, which constitute small to medium sized improvements. Emotional and conduct problems showed greater improvements than hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviour.

The parents of 135 children aged 5-17 completed a 12-month post-intervention questionnaire. Analysis of these responses showed:

-

for all 5 wellbeing measures, children showed no statistically significant regression towards pre-intervention levels of difficulties 12 months after their parents completed an intervention; and

-

5-17-year-olds showed further improvements in conduct up to 12 months after an intervention, though this was not significant at the 5% level.

4.2.2 2-4-year-old children

Figure 4.4 shows, for children aged 2-4, the mean standardised scores for each child wellbeing measure at the pre-intervention questionnaire and the 6-month postintervention questionnaire. For the precise figures for this chart, see Annexe 4.1.

Figure 4.4: Wellbeing changes for children aged 2-4 years old

| Strengths and Difficulties measure | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) |

|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 6 months after completion | |

| Emotional problems | 0.28 | 0.23 |

| Conduct problems | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.47 | 0.39 |

| Peer problems | 0.23 | 0.13 |

| Pro-social behaviour (lack of) | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| Total difficulties score | 0.33 | 0.26 |

Analysis of the outcomes for the 74 children aged 2-4 (for all interventions combined) that completed at least the pre-intervention questionnaire and the 6-month postintervention questionnaire between January 2019 and May 2022 shows:

-

improvements across all five child wellbeing measures used in the SDQ and reductions in total difficulties overall, significant at the 1% level for all but emotional problems and prosocial behaviour which are significant at the 5% level;

-

a medium-sized reduction in the total difficulties score; and

-

medium-small reductions in conduct and emotional problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviours.

Table 4.4 outlines the effect size for each child wellbeing measure, for 2-4-year-olds, comparing the pre intervention questionnaire with the first post intervention questionnaire:

Table 4.4: Effect sizes for each SDQ measure (2-4-year-olds)

| Child wellbeing measure | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|

| Emotional problems | 0.24 |

| Conduct problems | 0.39 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.32 |

| Peer problems | 0.34 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 0.30 |

| Total difficulties | 0.48 |

The findings demonstrate that after the parents of 2-4-year-olds completed an intervention, their child’s wellbeing improved for the full range of SDQ measures. It is at least 95% likely that this result would not occur if there was no change in children’s wellbeing. The effect sizes range from 0.30 to 0.48, with emotional and conduct problems showing greater improvements than hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviour.

Only 24 parents of children aged 2 to 4 years old completed a 12-month post-intervention questionnaire. Therefore, it was not possible to conduct robust analysis of sustained improvements in the wellbeing of these children.

4.3 To what extent did younger children experience different levels of improvements in their wellbeing, when compared with older children?

On average, whilst both age groups showed different effect sizes for individual subscales, they expressed a similar reduction in total difficulties after their parents completed an intervention.

The parents of 2-4-year-olds were asked slightly different questions, that are more applicable to younger children. However, only three of the 25 SDQ questions were different for 2-4-year-olds and 5-17-year-olds. The question on reflectiveness was softened, and two questions on antisocial behaviour were replaced by questions on oppositionality. The different questions are part of the conduct problems and hyperactivity scales:

Table 4.5: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire question differences

| Child wellbeing measure | 5-17-year-old question | 2-4-year-old question |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct problems | Often lies or cheats | Can be spiteful to others |

| Conduct problems | steals from home, school or elsewhere | Often argumentative with adults |

| Hyperactivity | Thinks out before acting | Can stop and think things out before acting |

The mean scores for these scales were therefore not directly compared, however, Cohen’s d comparisons are valid across different scales, so effect sizes are compared. Additionally, large population-based surveys in the UK suggest slightly different population norms for 2–4-year-olds compared to older children.

Analysis shows that:

-

on average, before intervention children aged 5-17 showed greater difficulties across the full range of comparable child wellbeing measures than 2-4-yearolds;

-

the effect sizes for peer problems, hyperactivity and prosocial behaviour were slightly larger for 2-4-year-olds;

-

children aged 5-17 showed greater reductions in emotional problems; and

-

children aged 2-4 and 5-17 experienced the same reduction in total difficulties, with a medium effect size for both groups.

Both 2-4-year-olds and 5-17-year-olds showed statistically significant improvements in child wellbeing up to 6 months after their parents completed an intervention. Whilst the two age groups experienced different effect sizes for each individual measure within the SDQ, they showed the same reduction in total difficulties. This was driven by a generally higher effect size for 2-4-year-olds, but a far larger effect size for emotional problems in 5-17-year-olds.

It was not possible to compare the sustained improvements up to 12 months after intervention because only 24 parents of children aged 2-4 completed a 12-month post-intervention questionnaire.

4.4 To what extent did intact and separated families experience different levels of improvement in interparental relationships and children’s wellbeing?

On average, both intact and separated families showed improvements in interparental relationships and children’s wellbeing. However, this was generally larger for intact families.

Both intact and separated parents showed medium-large improvements in interparental relationships after completing an intervention. As separated parents have different relationship issues to intact parents, the evaluation used different measures, comprising different questions for each parent group. Consequently, it was not possible to make direct comparisons. However, using Cohen’s d allows a broad comparison, which showed that intact couples experienced greater improvements across the range of relationship measures.

The average effect size for intact parents was 0.72, compared with 0.51 for separated parents. It is notable that interventions provided to separated parents targeted different relationship problems, so it is not necessarily expected that the effect sizes are comparable. The difference in average effect size was driven primarily by the small effect sizes for co-parenting support (0.22) and satisfaction with custody arrangements (0.23) or separated parents. Co-parenting support and satisfaction with custody arrangements focus on similar themes, such as flexibility with visiting arrangements and financial support and are not as easily comparable with the measures for intact parents. Excluding these measures from the comparison, the average effect size for separated parents was 0.69. This is close to the average effect size for intact parents and suggests that whilst intact parents do show greater interparental relationship improvements, it may be as a result of the relationship measures chosen and the specific behaviours measured.

4.4.1 Children’s wellbeing

Figure 4.5 shows, for children aged 5-17, the mean scores for each child wellbeing measure at the pre-intervention questionnaire and the 6-month post-intervention questionnaire broken down by whether their parents were intact or separated.

Figure 4.5: Wellbeing changes for children aged 5-17 years old from intact and separated families

| Strengths and Difficulties measure | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) | Standardised behavioural score (1.0 represents the maximum possible negative score; 0.0 represents the best possible score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact parents | Intact parents | Separated | Separated | |

| Before intervention | 6 months after completion | Before intervention | 6 months after completion | |

| Emotional problems | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.36 |

| Conduct problems | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| Peer problems | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.24 |

| Pro-social behaviour (lack of) | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| Total difficulties score | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.33 |

111 intact families, and 239 separated families with children aged 5-17 completed both a pre-intervention questionnaire and a 6-month post-intervention questionnaire. Additionally, 28 intact, and 46 separated, families with 2-4-year-olds also completed these questionnaires. Unlike comparing interparental relationships between intact 43 and separated families, the child wellbeing measures used for both family types are the same. This allows for a more direct comparison between groups.

Table 4.6 outlines the effect size for each child wellbeing measure for intact and separated families, for 5-17-year-olds, comparing the pre-intervention questionnaire with the first post-intervention questionnaire. The following conclusions are based on comparing measures from the pre-intervention questionnaire with the first postintervention questionnaire:

-

children of both intact and separated parents showed significant improvements across the full range of wellbeing measures, significant at the 1% level for all scales, but prosocial behaviour (5% level) and hyperactivity (not significant at the 5% level for intact, but significant at the 1% level for separated); and

-

children with intact parents experienced greater improvements across the full range of child wellbeing measures, excluding hyperactivity.

Table 4.6: Effect sizes for each SDQ measure (separated v intact parents)

| Child wellbeing measure | Intact Cohen’s d | Separated Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional problems | 0.62 | 0.44 |

| Conduct problems | 0.55 | 0.33 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Peer problems | 0.36 | 0.17 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| Total difficulties | 0.61 | 0.42 |

The greater improvements in wellbeing for children with intact parents was driven mainly by larger effect sizes for emotional, conduct and peer problems. Different interventions were delivered in each CPA, therefore in addition to an ordinary area effect, an intervention effect may be captured by the area in which the family lived. If the proportion of separated/intact parents was sufficiently different in each CPA, it may have influenced the effect sizes for intact and separated parents. For example, if intact parents predominantly lived in an area where more high intensity interventions were delivered, this may have accounted for the larger improvements seen in the children of intact parents. However, as Annexe 4.3 shows, the percentage of families that were separated was similar across all CPAs, and as such does not undermine the reliability of these findings. Intact and separated families may also participate in different types of intervention, which may explain differences in mean wellbeing scores and levels of improvement.

45 intact families and 92 separated families with children aged 5-17 also completed a 12-month post-intervention questionnaire. For both family types there was no statistically significant regression towards pre-intervention levels of child wellbeing.

4.5 To what extent did parents participating alone experience different levels of improvement to families where both parents participated?

On average both groups showed improvements in interparental relationships and children’s wellbeing. However, improvements were generally larger for families where both parents attended an intervention.

4.5.1 Key programme numbers

As the evaluation relied on at least one parent per family to have completed both preintervention and post-intervention questionnaires, the analysis is based on the responses from:

-

parents in 345 intact and 387 separated families, where both parents were known to have participated; and

-

181 separated parents and 45 intact parents who participated without the cooperation of the other parent.

This means that a greater proportion of intact families participated together[footnote 19] (85% of intact families compared with 68% of separated families).

Changes in interparental relationships are reported for intact and separated parents separately because they were asked different questions.

4.5.2 Separated families and joint participation

Table 4.7 (below) shows the effect sizes for each relationship measure for families where both parents participated, or just one parent participated. The following conclusions are based on comparing measures from the pre-intervention questionnaire with the first post-intervention questionnaire:

-

All families showed significant improvements across all five measures of interparental relationships (significant at the 1% level), regardless of whether both parents, or only one parent, participated.

-

The effect sizes were, on average, larger for families where both parents participated.

-