National Living Wage and National Minimum Wage: government evidence on compliance and enforcement 2019 to 2020 (web)

Published 24 February 2021

Introduction and report outline

This summary report outlines the government’s enforcement of the National Minimum Wage across the 2019/20 financial year.

Following previous years, 2019/20 saw record results.

- HMRC closed more than 3,300 cases compared to 3,000 in 2018/19, with nearly 1,300 closed with arrears

- £20.8 million in arrears were identified, for over 263,000 workers

- HMRC issued almost 1,000 penalties, a similar amount to the previous year, but with a higher total of £18.5 million

- Targeted enforcement continued to rise, accounting for 65% of closed cases, 10% points higher than in 2018/19

HMRC follow a ‘Promote, Prevent and Respond’ approach, using a variety of techniques to promote awareness.

Over 500,000 mass emails opened

Over 3,500 views of live Minimum Wage contnet (including webinars)

6,600 views of pre-recorded Minimum Wage contnet

235,000 SMS related searched activity

This was supplemented by BEIS media campaign and employer guidance, resulting in nearly 900,000 employers and workers directed to seek further information.

This report provides an overview of minimum wage enforcement activity throughout the 2019/20 financial year. It follows last year’s report, published in February 2020[footnote 1], covering activity during 2018/19.

We have published the same volume of data as in previous years, via corresponding Excel tables. This summary report presents key statistics from the 2019/20 financial year. It describes important trends shown in the accompanying excel tables and references the data throughout[footnote 2].

Also included in this report is our response to enforcement recommendations made by the Low Pay Commission (LPC) in their 2020 report. We accept 6 out of the 7 recommendations and partially accept the last, discussed in the final section of this report.

Background

The minimum wage rates

The National Minimum Wage (NMW) was introduced in 1999, with the National Living Wage (NLW) introduced in 2016. The NMW and NLW (together referred to as the minimum wage) provide essential protection for the lowest paid workers, ensuring they are fairly compensated for their contribution to the UK economy.

The minimum wage sets a minimum hourly rate of pay that all employers are legally required to pay to their workers. Almost all UK workers are entitled to the minimum wage, although the rate of pay that they are entitled to is dependent on their age and whether they are an apprentice[footnote 3]. Table 1 below shows the minimum wage rates that were applicable across the 2019/20 financial year (the enforcement year covered in this summary report[footnote 4]).

Table 1. Minimum wage rates (per hour) as of April 2019 and April 2020

| Age Band | April 2019 | April 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| 25 years old and over | £8.21 | £8.72 |

| 21 to 24 years old | £7.70 | £8.20 |

| 18 to 20 years old | £6.15 | £6.45 |

| 16 to 17 years old | £4.35 | £4.55 |

| Apprentice | £3.90 | £4.15 |

Source: HM Government (2020b)

Minimum wage enforcement in 2019/20

Enforcement of the minimum wage

Government is clear that anyone entitled to the minimum wage should receive it and is committed to pursuing employers who do not pay it (here referred to as non-compliance). Whilst the vast majority of employers pay their staff correctly, there is a small minority who fail to do so, either deliberately or through inadvertent non-compliance.

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) enforce the minimum wage on behalf of the government. HMRC proactively use a variety of methods to encourage compliance and alter employer behaviour, based around a ‘Promote, Prevent and Respond’ strategy.

Promoting compliance is based upon the idea that most of non-compliance is due to a lack of information and/or incompetence, rather than deliberate behaviour from the employer. The main approach is to improve the information available to employers; on the assumption that employers will become compliant with the law once they better understand it. Employers who do not respond to compliance measures can then be identified and subjected to enforcement action.

Deterrence is based on the principal that some employers actively make a rational decision whether to underpay, balancing the potential benefits of underpaying workers against the risk and consequences of being caught. The aim, therefore, of enforcement should be to alter employers’ behaviour by raising the risk of being caught, and by highlighting the consequences of being caught.

When identifying a case, HMRC either respond to worker complaints made directly through their online complaint form or redirected ACAS calls, or target a specific employer based on various different risk factors.

Once underpayment has been identified, HMRC pursue employers to ensure that any arrears are paid to workers as soon as possible. In some instances, employers are given the opportunity to “self-correct” their own arrears before HMRC pursues more stringent penalties if employers fail to take steps to ensure workers’ pay is compliant with the law. Sanctions to deter future non-compliance include:

- financial penalties

- public naming by BEIS on the gov.uk website

- issuing Labour Market Enforcement Undertakings (LMEUs)

- prosecution (in the most malicious, serious cases of non-compliance)

HMRC’s budget for enforcing the minimum wage has nearly doubled since the introduction of the NLW, increasing from £13.2 million in 2015/16, to £26.3 million in 2019/20. This is to account for the increasing number of workers brought within scope of increasing minimum wage rates, to promote more recent changes in minimum wage legislation and to further enhance compliance.

Promoting compliance

Both BEIS and HMRC carry out communications activity to promote the minimum wage and improve worker and employer awareness to encourage compliance. Promote activity aims to prevent non-compliance occurring in the first place by changing the behaviour of both employers and workers. HMRC’s minimum wage ‘Promote’ team carries out a variety of work to achieve this; working with employers to put them in a position to be compliant, and encouraging workers to check their pay in line with the minimum wage legislation and to make a complaint if necessary. In 2019/20, HMRC’s Promote team encouraged nearly 900,000 employers and workers to seek further information regarding the minimum wage. This is an increase from the previous year (264,135) and is mainly due to text message (SMS) related search activity (over 200,000) and mass email mail outs (over 500,000).

HMRC provided a large amount of information to ensure the workers and employers are aware of legislation. In 2019/20, this resulted in:

- nearly 30,000 views of the work experience and intern’s guidance and over 10,000 views of the technical manual

- over 13,000 views of the Calculating the Minimum Wage guidance

- over 6,600 views of pre-recorded minimum wage content (e.g. YouTube videos, e-learning material and recorded presentations)

- over 3,500 views of live minimum wage material, (e.g. live webinars, face-to-face presentations and online events)

This demonstrates the work the Promote team have done to inform workers of their rights and employers of their obligations, ensuring future compliance with legislation. The figures presented show that employers and workers are making use of the information and are actively seeking to educate themselves on specific aspects.

BEIS launched a £1.1 million campaign in April 2019 to encourage workers to check their pay, educate them on the common ways they may be being underpaid and to explain what they can do if they believe they are underpaid.

Enforcement in 2019/20

The 2019/20 financial year was another strong year for minimum wage enforcement; HMRC opened over 3,500 cases in 2019/20, an increase of 27% from the previous year (2,800). More than 3,300 cases were closed, a rise of 12% since 2018/19, with nearly 1,300 closing with arrears. The proportion of closed investigations where employers are found to be non-compliant (also known as the “strike rate”) of 42% is consistent with preceding years.

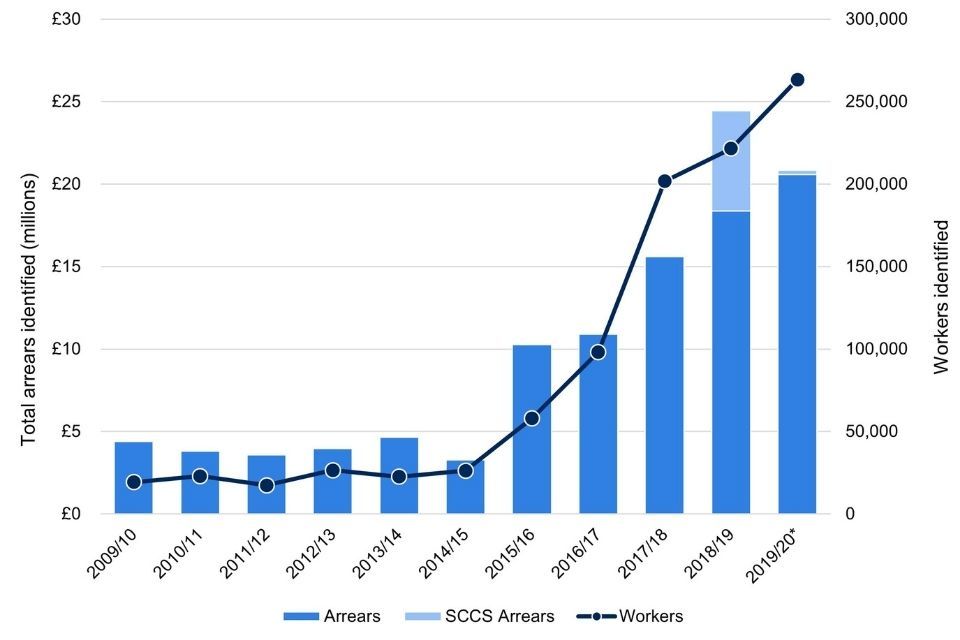

Figure 1 below shows that HMRC identified over £20.8 million in arrears for more than 263,000 workers and issued just under 1,000 penalties totalling £18.5 million to non-compliant employers[footnote 5].

This means that since the introduction of the NMW in 1999, the government has ordered employers to repay over £139 million to 1.1 million workers, issued over £59 million in financial penalties and completed over 81,000 investigations.

Figure 1: minimum wage investigations: arrears and workers identified

This graph shows the number of workers and arrears identified in each financial year, from 2009/10, to 2019/20.

Source: BEIS/HMRC enforcement data

Notes on Figure 1

An additional 30 cases were originally closed in 2015/16 but the employer notified HMRC of additional arrears in 2016/17. The arrears in these cases are included in the arrears total for 2016/17.

There are an additional 11 cases originally closed prior to 2018/19 which notified further arrears in 2018/19. These cases are included in the arrears total for 2018/19.

There are an additional 8 cases originally closed prior to 2019/20 which notified further arrears in 2019/20. These cases are included in the arrears total for 2019/20.

Table 1 in the accompanying Excel data also shows that average arrears per case stood at nearly £6,200 in 2019/20, and that average arrears per worker stood at £79 – a continuation of the longer-term trend of declining average arrears per worker. This is in part due to the change in HMRC’s approach; taking account of non-compliance across an employer’s whole business, rather than just the specific worker who may have complained. Whilst this means employers can be fully compliant in the future and that more workers are reached, the arrears identified can vary significantly in value.

Table 2 in the accompanying Excel data shows that in 2019/20, of the 1,268 cases closed with arrears, HMRC closed 33 cases which had over £100,000 in arrears each. Together, these cases reached a total of nearly £14.5 million in arrears[footnote 6], and accounted for over 174,000 workers. This remains consistent with the previous year, where HMRC closed 34 cases in excess of £100,000 in arrears, reaching a total of £17.4 million for almost 164,000 workers.

Targeted and complaint led enforcement

Non-compliance with the minimum wage is identified through two routes. In the first instance, a worker can raise a complaint via the Acas helpline or via HMRC’s online complaint form. This is referred to as “complaint-led” or reactive enforcement.

As with last year, the majority of complaint led cases in 2019/20 were received via HMRC’s online complaint form (2,552), as opposed to the Acas helpline (752) or ‘other’ sources (28). For more information, please see Table 8b in the accompanying Excel spreadsheet.

HMRC respond to every single complaint made by a worker (either to HMRC or referred via Acas) and use a risk-based triage to determine the most appropriate course of action.

There are a number of interventions that HMRC can use to pursue a complaint-led case. These are proportionate to the level of risk of non-compliance and are designed to ensure that workers understand their legal entitlements and receive any arrears owed. The interventions that HMRC use include: ‘nudge’ letters, telephone contact with employers and workers and face-to-face meetings with employers and workers[footnote 7].

Additionally, HMRC can themselves identify cases of non-compliance by proactively targeting sectors or employers where they believe non-compliance is prevalent. This is referred to as “targeted enforcement”.

Targeted enforcement is informed by HMRC’s risk model, which uses data from a range of sources (including PAYE, Tax Credits information, information from other labour market enforcement bodies, NMW intelligence and complaints data and ministerial priorities) to identify workers most at risk of NMW underpayment. The risk model continues to yield encouraging results and accurately identify businesses with a high risk of underpayment. For information about the volume of targeted enforcement cases through these different sources, please see Table 7b in the accompanying Excel spreadsheet.

As with complaint-led enforcement, there are a number of ways in which HMRC can pursue a targeted enforcement case. These include one-to-one meetings with employers, team-based reviews of businesses and multi-agency joint working (to tackle risks of cross-cutting illegal behaviours).

The threat of being the subject of targeted enforcement provides a valuable deterrent to employers and supports workers who may not be aware that they are underpaid or who are unwilling to raise a complaint. Targeted enforcement is therefore an essential means to reach at risk workers, as they may not otherwise come forward to make a complaint.

Targeted enforcement continues to form an important part of enforcement activity; HMRC opened over 2,500 targeted enforcement cases in 2019/20 – the largest number and the largest share of cases opened (70%, a 17% percentage increase from 2018/19) since 2014/15. Targeted enforcement made up a correspondingly large proportion of all cases closed in 2019/20 (65%, an 10% percentage point increase from 2018/19). For more information, please see Table 7a in the accompanying Excel spreadsheet.

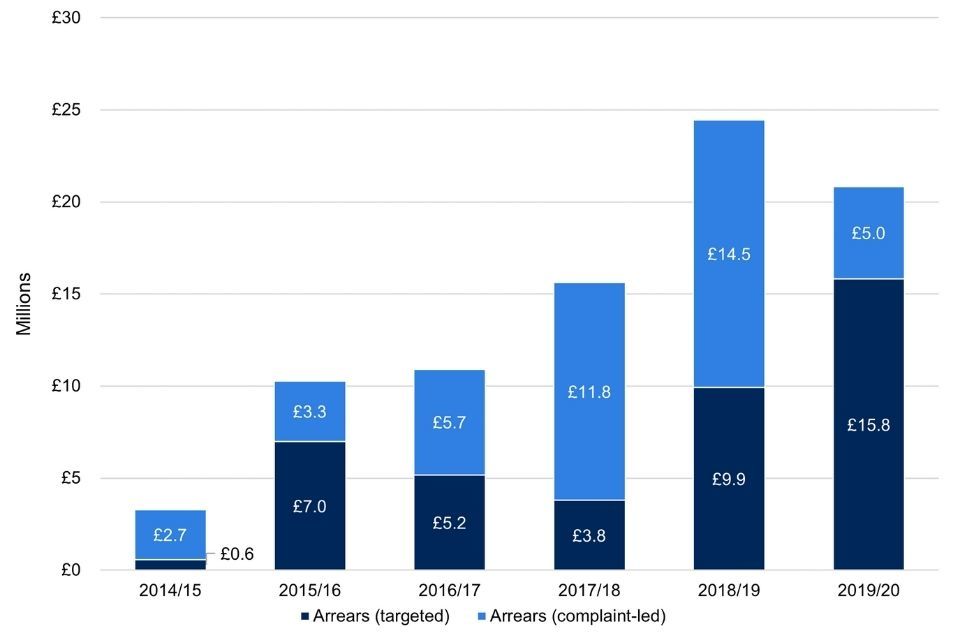

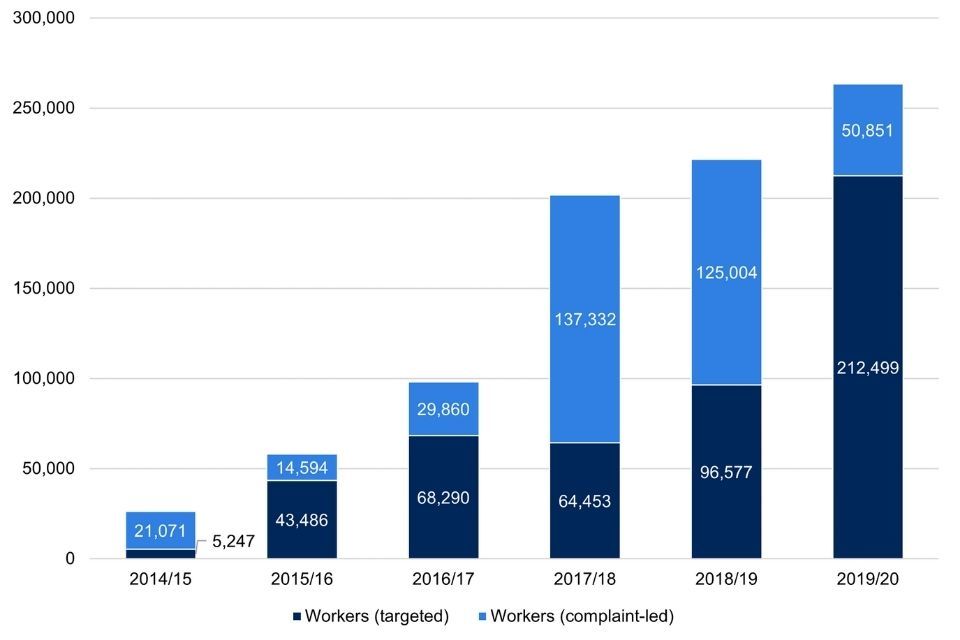

Together, this meant that the highest number of workers and arrears were identified as part of targeted enforcement in 2019/20. Figures 2 and 3 below show that 76% of arrears (£15.8 million) and 81% (212,000) of the workers identified were found through targeted enforcement; and that this proportion has increased over the last six years.

Figure 2. Arrears identified through targeted and compliaint-driven enforcement

Figure 2 shows the number of arrears identified, broken down by targeted led enforcement cases and complaint led cases. The data shows this for the financial years 2014/15 to 2019/20.

Source: BEIS/HMRC enforcement data

Figure 3. Workers identified as underpaid though targeted and complaint-driven enforcement

Figure 3 shows the number of workers identified as underpaid, broken down by targeted led enforcement cases and complaint led cases. The data shows this for the financial years 2014/15 to 2019/20.

Source: BEIS/HMRC enforcement data

Tables 7a and 8a in the accompanying Excel data show that the strike rate for targeted enforcement cases is lower than in complaint led cases (38%, as opposed to 49%), although this gap has slightly narrowed since 2018/19 last year (37% for targeted cases, 55% for complaint-led cases). Complaint-led cases are more likely to have a higher strike rate because HMRC’s investigation is based upon a direct source of intelligence (i.e. a worker’s complaint), as opposed to predicting non-compliance to target employers. Despite this, the strike rate for targeted enforcement remains relatively high, and reflects HMRC’s ability to successfully identify employers, especially given the increasing volume of targeted enforcement cases.

Penalties, undertakings, prosecutions, and the minimum wage Naming Scheme

HMRC continues to respond strongly in cases where workers have been underpaid the minimum wage. HMRC use a mix of civil penalties, enforcement undertakings, criminal prosecutions and the BEIS minimum wage Naming Scheme to deter other employers from underpaying their workers.

Civil penalties and Labour Market Enforcement Undertakings

One of the Government’s aims is to ensure that, as a result of enforcement action, workers receive the money they are owed as quickly as possible. In the vast majority of cases HMRC pursues the civil enforcement route, which is the quickest way of ensuring workers receive their arrears. The civil route includes HMRC conducting an investigation, identifying if workers have been underpaid and then taking enforcement action via the civil courts if payment is not made.

Nearly 1,000 (992) penalties were issued to non-compliant employers in 2019/20, a similar amount to last year (1,008). The total value of the penalties issued increased by 8% relative to 2018/19; from £17.2 million to nearly £18.5 million in 2019/20.

As well as issuing penalties, HMRC can also issue Labour Market Enforcement Undertakings (LMEUs). LMEUs were introduced in 2016, and specifically target non-compliant businesses who persistently breach minimum wage legislation and secures future compliance to protect workers from continuing abuse. When issued with an LMEU, businesses are required to enter into an ‘undertaking’ to take steps to prevent further offenses. If a business refuses or fails to comply, then a magistrates’ court (or similar in devolved administrations) has the power to impose an Order which requires the business to take action to avoid further offenses. The amount of LMEUs issued by HMRC has increased, rising to 21 in 2019/20.

Criminal prosecutions

Only the most serious non-compliant cases are referred for criminal investigation and prosecution. Our intention is to cooperate with employers and workers to help them understand minimum wage legislation and to deter employers from underpaying workers.

Criminal prosecutions are significantly more costly than civil cases and do not guarantee that arrears are repaid to workers; further enforcement may be required to ensure this happens. HMRC considers all the evidence and whether it is in the public interest to prosecute.

HMRC’s Serious Non-Compliance teams undertake a programme of employer-specific investigations and multi-agency operations to identify potential criminal behaviours to refer for criminal investigation by HMRC’s Fraud Investigation Service. HMRC will then refer cases to the Crown Prosecution Service who ultimately decide whether to prosecute.

Since 2007, fifteen employers have been successfully prosecuted for underpaying the minimum wage, with the most recent prosecution in November 2019. For more information about these prosecutions, please see Table 12 in the accompanying Excel data.

Naming Scheme

The minimum wage Naming Scheme remains a key part of the civil sanctions used to deter employers from breaking minimum wage law. The Naming Scheme highlights non-compliant employers by exposing their breaches publicly, promoting their future compliance and deterring other businesses from underpaying the minimum wage.

Following a review, we announced in February 2020 that the Naming Scheme would continue under revised criteria[footnote 8]. The latest naming round (Round 16) has now been published, alongside a new educational bulletin which highlights and explains common reasons for minimum wage underpayment. In Round 16, 139 employers were named for £6.7 million in minimum wage arrears owed to 95,000 workers – the largest amount of arrears ever identified in a naming round. Together, this means that over 2,000 employers have now been named since the introduction of the scheme in 2013.

For more information, please see: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/rogue-employers-named-and-shamed-for-failing-to-pay-minimum-wage

Measuring non-compliance with the minimum wage

We use a number of information sources to assess the scale and nature of minimum wage non-compliance, which in turn informs our enforcement approach.

Estimates of non-compliance can be made using the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE); a survey of employees completed by employers. ASHE provides information about the levels, distribution and make-up of earnings and hours paid for employees[footnote 9]. Using ASHE, we can estimate the number of jobs paid below the minimum wage at a particular point in time. These estimates can be broken down by sex, age, region, sector, and full-time and part-time working.

However, a number of methodological issues (including the proximity of the survey to the annual minimum wage uprating; the fact that the survey only measures underpayment in the formal economy; and there being legitimate reasons for underpayment) mean that ASHE does not offer a direct measure of minimum wage non-compliance. The 2020 ASHE survey was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and UK-wide ‘lockdown’, which started on the 23 March 2020. Restrictions lasted for the duration of fieldwork, and meant that the survey was affected in the following ways:

- Non-essential businesses were not open during fieldwork, meaning that employers could not complete the paper questionnaires sent to their premises. This meant a smaller number of employers completed the survey than in previous years.

- The type of employers who completed the survey also changed, as certain types of employer (e.g. those in the retail and hospitality sector) were more likely to be affected by lockdown restrictions. This meant that additional weighting was required to adjust the profile of the survey.

- Workers were furloughed, meaning that many workers earnt less than they normally would during the survey period (i.e. 80% of their normal earnings). The rules for calculating furlough pay for the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) also meant that the 2020 minimum wage uprating may not have applied to the calculation of furlough payments. This is because furlough payments received via the CJRS corresponded to hours not worked; hours worked were still subject to minimum wage requirements[footnote 10]. It was not possible to amend the ASHE questionnaire to account for furlough, meaning that erratic pay information was recorded. It is difficult to establish with certainty that any minimum wage underpayment is ‘genuine’ underpayment. It could equally be a result of the conditions attached to furlough[footnote 11], or because of employers provided erroneous information due to uncertainty over how to account for furlough in their response.

Aided by conversations with BEIS and the LPC, the ONS took steps to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This included: including additional guidance separate to the questionnaire, to better help employers complete the survey for furloughed workers; extending fieldwork to allow for a greater number of employers to respond to the survey; creating new survey weighting so that the employers who responded better reflected the UK employer population as a whole; working with HMRC to append markers for furloughed workers; and conducting extra data validation to correct pay information. Despite this, there are signs that the data (and particularly estimates of underpayment) have changed relative to previous years.

Measuring minimum wage non-compliance in 2020

The issues outlined above mean that (unlike in previous years) there are various ways in which underpayment estimates may be calculated, based on including or excluding furloughed workers; and including or excluding those who saw a “loss in their pay” due to furlough.

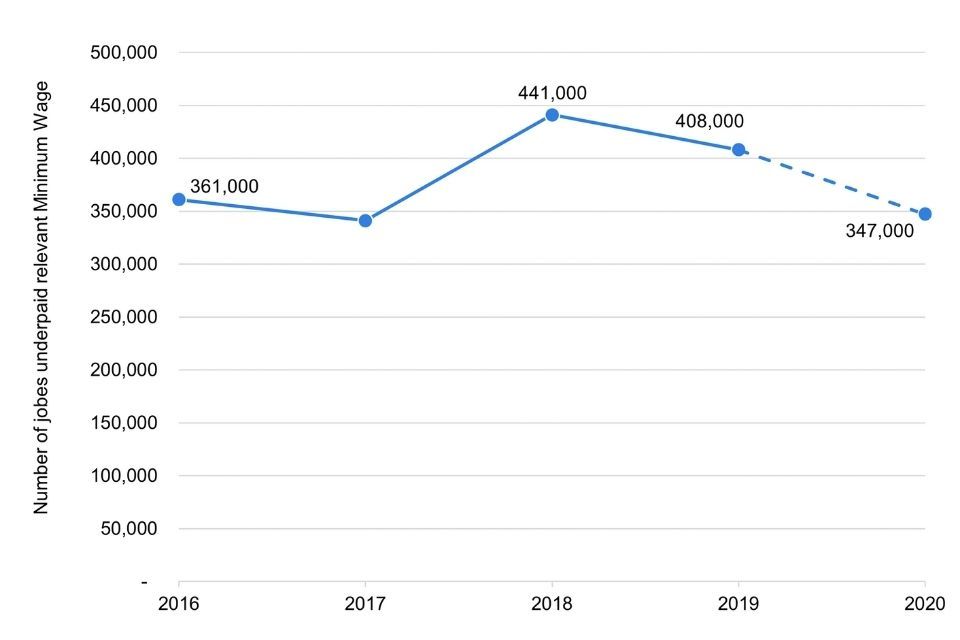

Furloughed workers are predominantly receiving pay for hours not worked, which is not subject to NMW legislation. This means that most instances where furloughed workers receive an amount below the minimum wage, is unlikely to be ‘true’ minimum wage non-compliance. It is instead likely to be associated with the conditions attached to furlough. However, we acknowledge that furloughed workers are more likely to be lower-paid, and that some furloughed workers in ASHE may already have been receiving less than the minimum wage in their job prior to being furloughed (i.e. would be part of the 408,000 underpaid workers identified in 2019, see Figure 4 below).

Analysis of workers with pay below the NLW/NMW

Estimates from the ONS found that an estimated 2,041,000 workers earnt below the minimum wage in April 2020. However, as they acknowledged, the majority of these workers were furloughed, and this is therefore not representative of minimum wage non-compliance. These workers would not have worked any hours in the reference period, therefore minimum wage legislation would not be applicable to these pay estimates.

As noted by the Low Pay Commission in their 2020 report, estimates including furloughed workers are an overestimate of underpayment, as many of the furloughed workers would not ordinarily be paid below the minimum wage.

Once furloughed workers are removed, we estimate that approximately 347,000 workers were paid below the relevant minimum wage in April 2020, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 4 below.

We recognise that this may be an underestimate, as it excludes some low-paid workers who would otherwise be underpaid (i.e. as discussed above, some furloughed workers were likely paid below the minimum wage before being furloughed). It is likely that the true figure for underpayment is marginally higher than this estimate. However, this is unobservable in the data. In the absence of being able to accurately estimate minimum non-compliance, we undertake our analysis on pay estimates of workers not furloughed.

Tables 15-19 and Figures 16-19 in the accompanying excel data provide further information on underpayment across different subgroups of worker.

Figure 4. Minimum wage underpayment over time (2016-2020)

Figure 4 shows our estimates of minimum wage underpayment from 2016 to 2020, based upon ASHE.

Source: BEIS analysis of ASHE 2016-2020 (ONS)

Notes

Figures are rounded to the nearest thousand.

This shows underpayment across all minimum wage rates

Table 2. Estimates of minimum wage non-compliance in 2019 and 2020

| Minimum wage rate | April 2019 | April 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| 25 years old and over (NLW) | 345,000 | 297,000 |

| 21 to 24 years old (NMW) | 32,000 | 25,000 |

| 18 to 20 years old (Development) | 9,000 | 18,000 |

| 16 to 17 years old (Youth) | 3,000 | 3,000 |

| Apprentice | 9,000 | 5,000 |

| Total | 408,000 | 347,000 |

Source: BEIS analysis of ASHE 2020 (ONS)

Notes

Figures are rounded to the nearest thousand.

Underpayment figures for each of the minimum wage rates do not sum to the totals presented because of rounding.

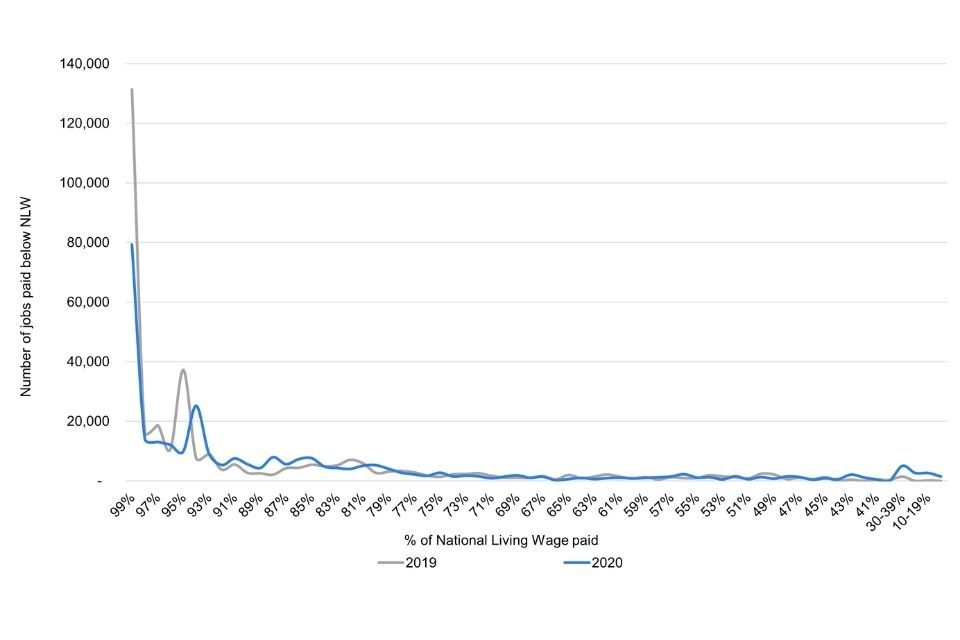

Due to the issues with the 2020 data, we cannot be certain how the outlook for underpayment has changed compared to last year. Once furloughed workers are removed, the distribution of National Living Wage underpayment follows a similar trend to previous years. Figure 5 – a wage distribution chart- examines this in more detail, by looking at how many people were earning different percentages of the minimum wage. In both 2019 and 2020, there has been a clear spike in underpayment at the previous year’s NLW rate. This demonstrates that some underpayment may have arisen from an employer’s failure to uprate their employees pay in line with the annual uprating. For example, the 2020 line shows a peak at around 94% of the 2020 rate, roughly equivalent to the old 2019 NLW (£8.21). Likewise, the 2019 line has a peak at a point close to the previous year’s NLW rate. The analysis in this chart complements Figure 19 in the accompanying Excel spreadsheet.

Figure 5. Distribution of National Living Wage underpayment in April 2019 and April 2020

Figure 5 shows the distribution of National Living Wage underpayment in April 2019 and April 2020. It indicates how much workers were underpaid by.

Source: BEIS analysis of ASHE 2020 (ONS)

Responding to the Low Pay Commission’s enforcement recommendations

In their non-compliance and enforcement of the National Minimum Wage report in May 2020, the Low Pay Commission made seven recommendations to Government. We are pleased to accept all of these, as detailed below.

| Recommendation | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | We recommend the government evaluates what data are recorded in non-compliance investigations, and considers how this can be used to develop measures of cost-effectiveness. | Accept |

| 2 | We recommend the government monitors the effects of the increase in the threshold for naming employers found to have underpaid workers. | Accept |

| 3 | We urge the government to take responsibility for the delivery of the new higher NLW target in the sectors where it is the main source of funding. | Accept |

| 4 | We recommend the government uses targeted communications to both apprentices and their employers to highlight underpayment risks, and in particular the problem of non-payment of training hours. | Accept |

| 5 | We recommend HMRC review the way they record apprentice underpayment, and to publish the numbers and profile of the apprentices they identify as underpaid. | Partially accept |

| 6 | We recommend that HMRC review their approach to investigations involving apprentices, to understand whether these investigations would identify non-payment of training hours. | Accept |

| 7 | We join the Director of Labour Market Enforcement in recommending that the government reviews the regulations on records to be kept by an employer, to set out the minimum requirements needed to keep sufficient records. | Accept |

Recommendation: We recommend the government evaluates what data are recorded in non-compliance investigations, and considers how this can be used to develop measures of cost-effectiveness.

Government accepts this recommendation and agrees this is necessary.

Recommendation: We recommend the government monitors the effects of the increase in the threshold for naming employers found to have underpaid workers.

Government accepts this recommendation. Having restarted Naming in 2020 following a period of review, we will monitor the process over the next few rounds of Naming to understand the effect of the increase in the threshold for naming.

Recommendation: We urge the government to take responsibility for the delivery of the new higher NLW target in the sectors where it is the main source of funding.

Government accepts this recommendation in full and aims to improve information sharing within government between minimum wage and sectors such as social care and childcare. The government will continue to consider the impacts of NLW targets as part of future spending reviews and ensure that it continues to gain collective agreement across government of future NLW and NMW rates. It will continue to publish an Impact Assessment alongside the legislation identifying affected sectors.

Recommendation: We recommend the government uses targeted communications to both apprentices and their employers to highlight underpayment risks, and in particular the problem of non-payment of training hours.

We accept this recommendation in full and will use upcoming communications activity to apprentices and their employers to highlight underpayment risks.

Recommendation: We recommend HMRC review the way they record apprentice underpayment, and to publish the numbers and profile of the apprentices they identify as underpaid.

We partially accept this recommendation. We have undertaken a review into the way in which apprentice underpayment is recorded. This found that the current HMRC case management system does not allow us to readily record information down to this granular level. Most NMW cases are multi factorial and may have more than one risk identified: any underpayments identified are not apportioned down or recorded to the individual risks. For example, seven workers may be underpaid by an employer but only one be an apprentice. On the current case management system this would show the arrears identified as non-payment of NMW. Conversely, an apprentice may not be paid for training time, but the hourly rate of pay is sufficient for there to be no underpayment overall (although the employer would be educated). Consequently, such amendments to the systems would not currently be proportionate. In the longer term the move to a Single Enforcement Body will create an opportunity for wholesale review of our systems, which may allow us to do this in the future subject to cost. This wholesale review will enable us to identify how feasible publishing further numbers regarding apprenticeship underpayment.

Recommendation: We recommend that HMRC review their approach to investigations involving apprentices, to understand whether these investigations would identify non-payment of training hours.

We accept this recommendation in full. HMRC NMW teams already consider whether there is an apprentice risk in every case. This includes speaking to the employer and apprentice about training hours to understand whether it is an issue.

Recommendation: We join the Director of Labour Market Enforcement in recommending that the Government reviews the regulations on records to be kept by an employer, to set out the minimum requirements needed to keep sufficient records.

Government accepts this recommendation. We already plan to extend the time employers are required to keep such records from 3 to 6 years, and will review the regulations on records required to be kept by employers to assess whether they are detailed enough. We will also consider alternatives to amending the regulations, such as reviewing our guidance to employers on what records they should keep for the purposes of minimum wage enforcement.

-

Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2020a) - National Living Wage and National Minimum Wage: government evidence on compliance and enforcement, 2019. ↩

-

The 2019/20 financial year ended on the 31 March 2020, approximately 1 week after the introduction of the UK-wide ‘lockdown’ introduced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the figures from 2019/20 do not show the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact of COVID-19 on minimum wage enforcement will be discussed in greater depth in the equivalent 2020/21 report. ↩

-

See HM Government (2020a) - who gets the minimum wage for details of the workers entitled to the minimum wage, and exceptions to this. ↩

-

See HM Government (2020b) - minimum wage rates for details of the current (2020/21) minimum wage rates. ↩

-

This includes arrears identified as part of the Social Care Compliance Scheme. This was a voluntary scheme that allowed employers to conduct a self-review to identify and pay any wage arrears to workers. Employers had up until March 2019 to identify and repay any arrears they owed their workers. For more information on the scheme, please see Chapter 7 of our equivalent 2018/19 report on minimum wage compliance and enforcement. ↩

-

These figures include normally assessed (i.e. arrears assessed by HMRC) and self-corrected arrears, which explains why there is a slight fall compared to last year. Only arrears that are normally assessed are subject to a penalty and included in the naming announcements. ↩

-

For more information about this activity, please see the 2018/19 report on minimum wage enforcement and compliance. ↩

-

For more information, please see Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2020b) - ‘Naming employers who fail to pay minimum wage to be resumed under revamped rules’. ↩

-

This is because furloughed workers’ minimum wage entitlement depends on when they ‘started’ furlough. If a worker started furlough prior to 1 April 2020, they were entitled to the 2019 rates throughout the period they were on furlough. If a worker started furlough from the 1 April onwards, the 2020 rates applied. It is not possible to determine which year’s minimum wage rates apply to each worker, because the date they started furlough is not available in the ASHE data. ↩

-

ASHE uses a paper questionnaire, printed months in advance of the survey starting. The questionnaires for ASHE 2020 were printed prior to the start of the UK lockdown, and there was not enough time to re-print them to account for furlough without significantly delaying the start of the survey. ↩