Adult skills gap and the falling investment in adults with low qualifications (HTML)

Published 29 January 2019

1. Executive summary

Helping those from disadvantaged backgrounds to succeed remains high on the political agenda. Research by the Social Mobility Commission and others has found little improvement in social mobility in recent years and deep-seated regional inequalities still exist across Britain.

Britain’s low levels of social mobility has attracted considerable amounts of research with much of the attention focused on improving education and skills in young people.

However, a crucial and often overlooked area is adult skills. In 2017 the Commission found that the UK has an endemic low pay problem with just 1 in 6 low-paid workers (17%) managing to permanently escape from low pay in the last decade.[footnote 1] Meanwhile, a quarter of low-paid workers remained stuck in low pay jobs.

Low pay is mainly a low skill problem but the UK currently lags behind other countries in giving adults a second chance to get on. Compared to its main competitors, the UK spends relatively little on vocational skills and investment in labour market support to increase adult skill levels. Between 2010 to 2011 and 2015 to 2016, the government Adult Skills budget in England fell by 34% in real terms.[footnote 2]

If the labour market is to work for everyone, those with lower skills and qualifications need to be able to improve their career prospects and realise their ambitions. For this to become a reality, employers and government have to create opportunities for individuals through training and better career progression. The government’s National Retraining Scheme provides an opportunity to refocus the adult skills budget on those with lower skills and qualifications, in particular, anyone experiencing or risking their jobs being displaced by technology.

In this report, we look at the adult skills landscape – by examining who invests in, and who participates in, job-related training and education. We consider how these trends have changed over time and to what extent adult skills affect social mobility.

We uncover evidence that people from the lowest socio-economic backgrounds are the least likely to receive adult skills investment. First, there is growing evidence to suggest that those whose parents were working class are less likely to do training than if their parents were middle class – even though they are doing the same type of job. Second, employers are more likely to invest in those with higher skills while better-off individuals are also more likely to fund their own training. This results in widening existing skills gaps as people from working class backgrounds are less likely to have higher skills – and are less likely to earn high wages – than their peers from better off backgrounds.

Only state-funded training targets support to those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, but this makes up a tiny proportion of all training courses undertaken (around 7%). The gender training gap, at the headline level, has been closed.

Indeed, women may be more likely to participate in training – largely because a higher proportion of women than men work in the public sector, where the provision of training is higher than in the private sector.

We also found mixed evidence of the returns to investment in adult skills. Research consistently suggests that the highest qualifications tend to lead to the highest returns, that academic qualifications lead to higher returns than vocational ones at the same level, and that qualifications gained later in life tend to secure lower returns than the same qualifications earlier on. Adult skills provide second chances to individuals, but those who benefit most are overwhelmingly those who already have higher levels of adult skills.

1.1 Key findings

The poorest adults with the lowest qualifications are the least likely to access training – despite being the group who would benefit most. Graduates are over 3 times more likely to participate in training than those with no qualifications (30% vs. 8% in 2017), and previous research has shown half (49%) of adults from the lowest socioeconomic groups have received no training since leaving school.

Almost twice as many people in managerial, professional and associate professional occupations access training (30%) compared to those in intermediate (16%) or routine and manual occupations (18%).

Bigger companies with better developed HR strategies are also more likely to fund training than smaller companies, but employers are prioritising high-qualified workers in senior positions for skill investment.

Since 2010, the proportion of training funded by government decreased and employer funding stayed flat, leaving individuals to fund more of their own training.

About £44 billion was spent on training (excluding student loans) in 2013/14 with most training (82%) provided by employers and much of the rest by individuals. The Government only funds 7% of all investment in adult skills and in 2016 to 2017 over £63 million of the adult training budget was unspent. UK spend on vocational training per employee was half the EU average.

The public sector is more likely to provide training than the private sector (in 2017, 36% of public sector workers participated in training compared to 19% in the private sector).

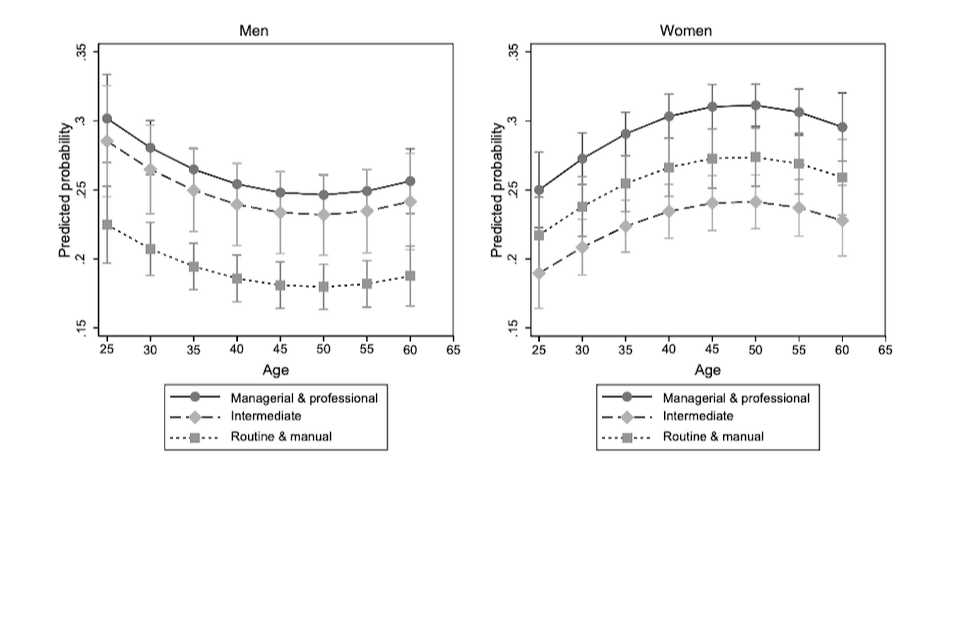

Men in routine and manual occupations were the least likely group to have done training regardless of age.

In 2017, more women than men undertook training (26% versus 21%), more people from Black and Black British ethnic backgrounds than from white backgrounds (32% compared to 23%), and more younger than older people (25% of 25 to 29 year olds compared to 17% of 60 to 64 year olds).

Adults whose parents worked in professional or managerial occupations are more likely to participate in training, no matter what their own occupation is, than those whose parents worked in lower-skilled occupations. This is because children of high-skilled parents are more likely to be high-qualified and in high-skilled jobs themselves, both of which increase access to training.

1.2 An action plan

This report shows there is a ‘virtuous’ and a ‘vicious’ cycle of learning, whereby those with the lowest or no qualifications are much less likely to get education and training and the highest qualified are likely to receive the most. This urgently needs to be reversed through a focus from employers and government on supporting those with low or no qualifications, those in the lowest skilled occupations, and those in the lowest socioeconomic groups.

Improving the social mobility impact of training will need 3 key changes:

- Increased employer spend on lower-skilled, low-paid workers

- Government support for increased availability of, and access to, free courses for those who cannot pay themselves

- Increased quality of training in terms of earning gains, and improved careers education, information, advice and guidance

Employers should seek to understand and address disparities in their training investment, and consider better work progression pathways by:

-

Improving the level and flow of skills within the business by developing workforce skills to help career progression, with a focus on those in low skilled roles.

-

Investing in the skills of the unemployed and economically inactive people in their local areas to increase the skills supply into businesses.

Government should increase the availability, accessibility and quality of training for adults who need it most by:

-

Increasing spending on education and training to bring it closer to that of international competitors, for example, to comparable expenditure levels of GDP, prioritising this extra financial support for those with no/low skills and qualifications.

-

Ring-fencing National Retraining Scheme funds for the groups who are shown receive the lowest investment, including low-paid and/or low-skilled people who are self- employed and men in routine, manual roles (particularly older men).

-

Reducing underspend of the Adult Skills budget via more flexible rules, including more digital and distance learning and flexibility in any underspend of the apprenticeship levy so that it can support shorter courses for low-skilled workers.

Government should also improve the quality of information available on adult skills, training and careers by:

-

Improving monitoring of government-funded and government-managed training provision for the take-up by, and impact on, those with low or no qualifications, those in lower level occupations and those in low socioeconomic groups, to inform evidence and to learn what works.

-

Investing in research on the impact of investing in training on longer-term social mobility outcomes to help individuals make informed choices about their training, using this to improve careers education, information, advice and guidance for adults.

2. Introduction

Warwick University Institute for Employment Research was commissioned by the Social Mobility Commission to undertake research into adult skills and social mobility.

2.1 Aims and objectives

The main aims of this research are to explore:

- How are adult skills defined and what is included in this definition in the scope of this report?

- Who invests in adult skills in the UK, and how has this changed over time?

- What characteristics affect the decision to invest in adult skills?

- How do adult skills affect socioeconomic outcomes?

- How do the findings inform policy goals of improving social mobility, in light of the government agenda of this Parliament, and longer-term changes to jobs and skills, and any recommendations about measuring and monitoring data going forward?

2.2 Research context

Social mobility in Britain is high on the political agenda. The State of the Nation 2017 report highlighted deep regional inequalities cross-cutting Britain. This revealed a stark postcode lottery where the opportunities and life chances of people from disadvantaged backgrounds is bound by where they live.[footnote 3] Research by the Commission and others has found that Britain has an ongoing ‘social mobility problem’[footnote 4] that has attracted considerable research and proposed solutions. At present, some of the main questions being asked focus on the relationship between the adult education agenda and social mobility, and include the following:

- Intergenerational movements: what are the odds that someone can end up in a higher class position (destination) than their parents’ class position (origin)?

- Intragenerational movements: what are the chances of someone ending up in a higher position than that they started from?

- What are the chances of access to professional occupations and elite universities for people from different backgrounds?[footnote 5]

- How do these issues vary with geography, sex, health, ethnicity, and other characteristics?

- What can be done to improve social mobility and life chances for people?

Education has often been seen as a vehicle for social mobility, but its effectiveness has been questioned. In this report, we focus on looking at who invests in adult skills, how this has changed over time, and whether investment in adult skills has any measurable impact on social mobility. We explain how we approach these issues below.

2.3 Data, definitions and methodology

The exploratory research in this report focuses on whether individuals’ investment in adult skills varies with their socio-economic background, and the kinds of outcomes that can result.

Data

The analysis is based on 2 main datasets, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and Understanding Society (UKHLS). The Quarterly Labour Force Survey is a survey of randomly-selected households. It has been carried out since 1992, although the quarters used in the Survey shifted from seasonal to calendar basis in 2006. There are roughly 90,000 individuals in each LFS quarterly survey, of whom about half are economically active. From the July to September 2014 quarter, the LFS included a new module on social mobility, which asks who the main wage earner was when the respondent was aged 14, and what occupation the main wage earner did. However, this question module only appears in the third (July to September) quarter, and is not available in the Annual Population Survey.

Understanding Society (UKHLS) is a longitudinal panel survey which follows a sample of the UK population since 2009 and incorporates the British Household Panel Study (BHPS, a similar longitudinal study, which started in 1991). Understanding Society contains over 40,000 households or over 100,000 individuals, with around 50,000 interviews with adults (aged 16+). The BHPS is considerably smaller, with roughly 5,000 households and 10,000 individual adult interviews. UKHLS waves 1 to 7 cover the period 2009 to 2016. Its design means that it is possible to look at variation in the decisions to invest in adult skills and in outcomes by sub-group, and to look at geographic region in more detail (England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland) than would have been the case if the BHPS data had been used.[footnote 6]

Definitions

By adult skills, we mean the education and training that people undertake once they leave formal full-time education, although adult skills can of course be a much broader concept than that (for example, skills that people develop through a number of activities, such as childcare, voluntary work, and as part of their daily life). In this report, we focus on 2 main measures of adult skills: whether individuals have undertaken any job-related training or education in the last 3 months or in the last year, and whether individuals have gained any qualifications in the last 12 months. Specifically, we focus on whether individuals have undertaken education and training or gained qualifications themselves, rather than looking at whether employers have funded individuals’ access to adult skills.

Types of training include: induction training, health and safety training, as well as training to develop one’s skills, or for professional/occupational standards reasons. Training might also be categorised into on- and off-the-job, with the latter tending to be more formal, and tending to yield higher wage returns than the former. As we refer to the findings from other research, the definitions of education and training vary according to the source, as do the definitions of social groups.

When we talk about social mobility outcomes in this report, we focus more on intragenerational social mobility – the extent to which the life chances and outcomes of individuals are affected by their acquisition of skills and qualifications in their adult life, and the extent to which education and training enables people to increase their earnings and become upwardly socially mobile. We do also look at parental background – the occupations of the individuals’ parents when the individuals were children. We use 2 measures of social mobility: the 3-group National Statistics Socio- economic Classification (NS-SEC), and the gross monthly income in respondents’ main jobs. For more information about the NS-SEC, see Box 1.

2.4 Box 1: The NS-SEC

The NS-SEC is a socioeconomic classification to categorise people into social classes based on their occupation and labour relations. Introduced in 2000, it builds on the Goldthorpe Schema sociological classification of class and measures employment relations and conditions of occupations. In so doing, it shows the structure of socio-economic positions in modern societies (ONS, 2010).

The main employment relations distinctions are between employers, employees, and the self-employed, and employees can be further classified by employment regulations such as: a service relationship (salary, career advancement, benefits), a labour contract (labour exchanged for a wage based on work done or time expended), or a hybrid, intermediate type of relationship. Further distinctions are made in terms of company size. The table below shows how the 8- 5- and 3-class NS-SECs are related to each other. In this report, we use the 3-group NS-SEC: whether someone is working in the managerial or professional occupations, intermediate occupations, or routine occupations. Note that the NS-SEC aims to describe employment relations and not skill levels (as is the case with the SOC).

2.5 NS-SEC classes

8-class

- Higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations

1.1 Large employers and higher managerial and administrative occupations

1.2 Higher professional occupations - Lower managerial, administrative and professional occupations

- Intermediate occupations

- Small employers and own account workers

- Lower supervisory and technical occupations

- Semi-routine occupations

- Routine occupations

- Never worked and long-term unemployed

5-class

- Higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations

- Intermediate occupations

- Small employers and own account workers

- Lower supervisory and technical occupations

- Semi-routine occupations

*Never worked and long-term unemployed

3-class

- Higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations

- Intermediate occupations

- Routine and manual occupations

*Never worked and long-term unemployed

Proportion of employed adults aged 25 to 64 in each NS-SEC class (2017, LFS)

- Higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations: 47%

- Intermediate occupations: 24%

- Routine and manual occupations: 29%

2.6 Methodology

We focus on adults aged 25 to 64 because younger adults are more likely to engage in full- time education, while people who are retired are less likely to engage in training and their socioeconomic status is harder to capture (socioeconomic status is typically linked to an occupation). We also focus on adults in employment, in part this is because the main measure used in the LFS is job-related training, but also because we would like to exclude any mandatory training programs that people who are claiming unemployment benefit may have to undertake or leisure courses which people take for their own personal pleasure.

Cross-sectional descriptive analysis is carried out to gain an understanding of the data, using the 2010 and 2017 Labour Force Surveys for July to September quarter. We then run a regression to see whether individuals’ investment in adult skills has changed over time, and what characteristics affect the decisions to invest in adult skills. See the technical annex for a more detailed discussion of our methodology.

We also include a discussion of the impact of investment in adult skills on social mobility and earnings from a range of existing research sources and summarise the main findings. We did attempt to investigate the effect of investment in adult skills (gaining training or a new qualification) on social mobility but encountered several problems in the data. A discussion of our approach is included in the technical annex. Moreover, we consider that, as there is an extensive research literature on the effect of undertaking training and gaining new qualifications on wages, discussing some of the most influential findings to date would provide a more balanced view, rather than conducting an additional study. The main contribution of our report is that we specifically look at the differences in adult skills investment, and their impact on social mobility, by socio- economic background.

The report starts with a short review of the main research on social background and investment in adult skills. First, we show who undertook training in 2010 and 2017 using the Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2010 and 2017 July to September quarters. Next, we look at how multiple factors affect the likelihood of participating in training using the LFS (and also analyse the UKHLS, details in the technical annex). We then bring together a range of recent research findings to discuss the impact of investing in adult skills on social mobility outcomes. The findings form the basis for the discussion and recommendations section. The conclusion summarises the main threads of the report and situates our findings in a broader policy context.

3. Who invests in adult skills?

3.1 Key findings

Around £44 billion was spent by employers, individuals and the government on training (excluding HE loans) in 2013 to 2014.

According to analysis of training expenditure, most training is funded by employers (82%) and individuals (9%).

Just 7% of training is funded by government. This tends to be provision targeted at those with lower/no qualifications and at those living in deprived areas.

Employer-funded provision tends to be from those organisations with better developed human resources and product marketing strategies, which are both linked to ‘good’ jobs.

Larger employers are more likely to invest in training than smaller employers (with fewer than 50 employees).

Public sector employers are more likely to invest in training than private sector employers.

3.2 Financial investment in adult skills

The financial investment in adult skills, including direct (such as training fees) and indirect (for example, lost earnings/production time) investment, is funded by individuals, employers, the state, and/or third sector organisations (TSOs).

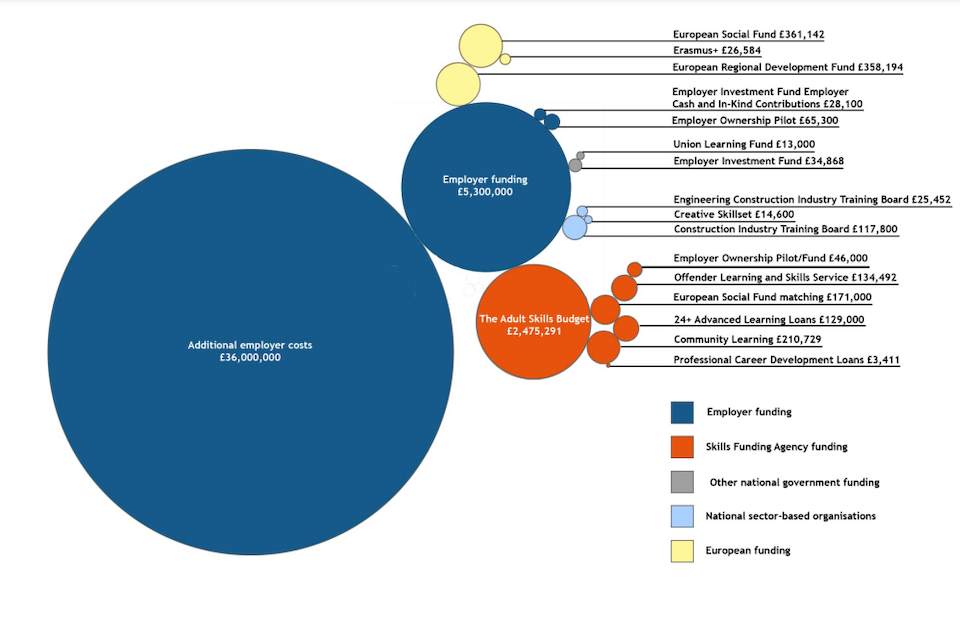

In 2013 to 2014, direct employer funding of training[footnote 7] was estimated at £5.3 billion, and government funding (through the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) amounted to around £3 billion (Figure 1).[footnote 8] Other government departments, particularly the Department for Work and Pensions, also fund training (estimated as £0.35 billion)[footnote 9] but these figures are not included in the diagram. European sources of funding (primarily the European Social Fund and European Regional Development Fund) totalled just over £0.7 billion.[footnote 10] The largest contribution by far is additional or indirect employer costs, which contribute an additional £31 billion to the funding of training. Overall, employers spent £36 billion in training in 2013 to 2014. Individuals’ expenditure in 2014 to 2015 was estimated to be at just under £4 billion (excluding loans). We assume that individual expenditure is a similar amount in 2013 to 2014, and add this to the amount in Figure 1 to get a sense of the total spend on training in that year.

Overall, the total spend on training illustrated in Figure 1 and including individuals’ expenditure roughly amounts to £44 bn. Of this, 82%was funded by employers (directly or indirectly), 7% by the government, 9% by individuals (including loans) and 2% by the EU.

Figure 1: Sources and scale of investment[footnote 11] in adult skills in England (£’000s) for 2013 to 2014

Source: LFS 2013 to 2014; ESS 2013, Figure taken from Gloster and others (2016), p.17.

3.3 Employers’ investment in adult skills

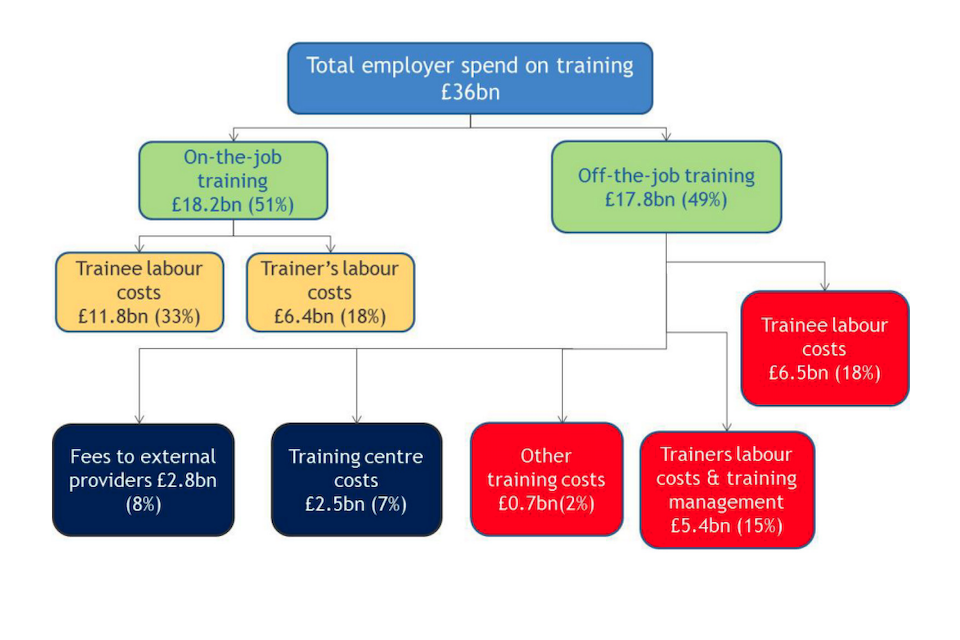

The breakdown of the employers’ £36 billion total investment is shown in Figure 2. Funding was split almost equally between off- and on-the- job training. The largest component of both of these types of training are trainees’ and trainers’ labour costs.

Figure 2: Overview of employer spend on training

Source: Taken from Gloster and others (2016), p.19

The level of employer investment in training varies by sector, and is closely related to whether the organisation is public (where 84% of employers have funded or arranged employee training), third sector (82%) or private (71%, Employer Perspectives Survey, 2016).[footnote 12] Organisations who have recruited in the past 12 months are also much more likely to invest in staff training (89%) compared to those who had not (56%). Human resources practices are also closely related to training investment: 90% of those employers accredited with Investors in People funded staff training compared to 69% who were not. Organisations with a positive growth outlook are also more likely to fund staff training: 79% who expected the business to grow paid for employee training, compared to 60% of those who expected the business to contract or remain the same.

Private sector employers with a higher product market strategy[footnote 13] are much more likely to invest in staff training (Employer Skills Survey, 2015). Of those describing their business as having a high or very high product market strategy, 69% funded staff training compared to 54% with a low or very low product market strategy. Those with a high/very high product market strategy were also much more likely to fund off-the-job training (51% compared to 37%). The orientation of the business with regard to product market strategy, as well as management practices, are key components of strategies to address low productivity and wages, and address poverty.[footnote 14]

Whilst employer investment in skills training appears substantial, a number of studies have identified that, compared to its main competitors, the UK has relatively low spending on vocational skills[footnote 15] and that investment in labour market support that can increase adult skill levels.[footnote 16] The picture is somewhat complex. In general, a high proportion of UK firms provide training, although this proportion has declined over time. In 2015, 86% of UK enterprises provided continual vocational training (CVT) courses and other forms of CVT compared to the EU-28 average of 73%.[footnote 17],[footnote 18] In 2005, however, the proportions were 90% and 60% respectively (over the period 2005 to 2015 the proportion of UK firms providing training has fallen while the EU-28 average proportion has risen). Similarly, on a simple headcount basis, participation in adult education and training in the UK was above the EU-28 average in 2011 (16.3% vs. 9.1%) and in 2016 (14.1% vs. 10.8%), although the proportion in the EU-28 has risen, while that in the UK has fallen over the period. Moreover, these measures do not capture the quality or extent of the training.

In contrast, the proportion of employees accessing training was lower in the UK than in the EU. In 2015, only 30% of the UK’s employees received CVT compared to the EU average of 41% and this proportion is well below that of the other European G7 countries (France, Germany and Italy).[footnote 19] Moreover, this represents a decline for the UK since 2005. Whilst the proportion of employees receiving continual vocational training in the UK fell by 2.2 percentage points between 2005 to 2015, the proportion across the EU rose by 8 percentage points.

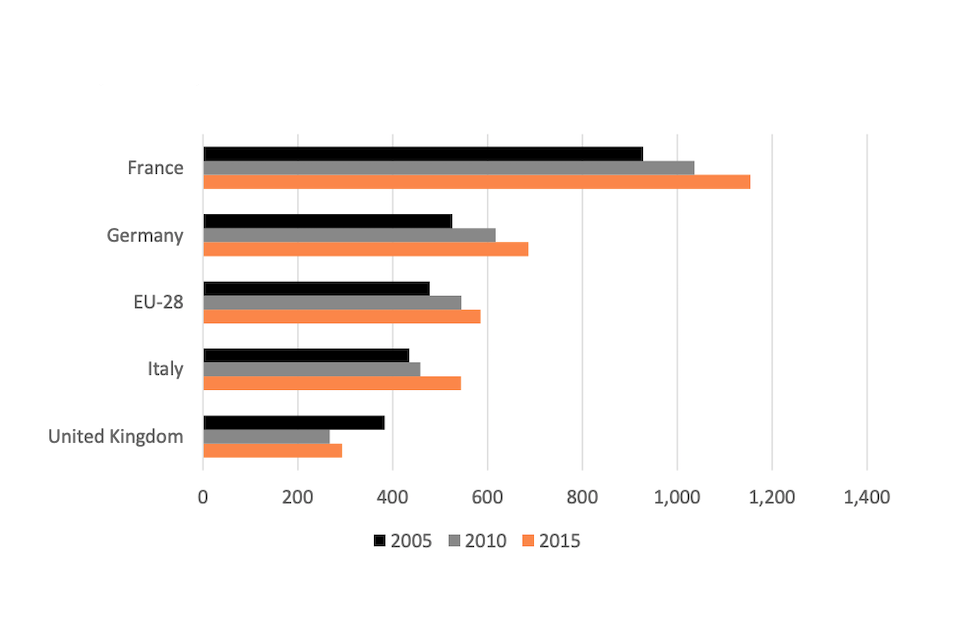

Furthermore, Figure 3 shows that the expenditure per employee on training courses is also much lower in the UK than the EU. In 2015, the amount spent per employee in the UK was just half of the EU-28 average (comparison in euro, down from 80% in 2005).[footnote 20] The amount spent per training participant in the UK was also below EU levels, around 2 thirds of the EU average in 2015 (68%, down from 82% in 2005). In addition, the UK spends less on vocational training as a proportion of the EU- 28 if the purchasing power standard exchange rate is used to adjust for the cost of living in different countries instead of euro.[footnote 21]

In addition to the measures discussed above, the UK is below the EU average on the following training-related measures: the proportion of GDP spent on education and training (see also Figure 4); the participation rate in education and training; the duration of formal training, and the level of training accessed.[footnote 22] This relative lack of investment manifests itself in the comparative skills of the British workforce. According to the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills, 2013 to 2016, England is ranked 14th on literacy, 18th on numeracy and 10th on problem solving.[footnote 23]

Employer skills training, already at a low level by international standards, has remained broadly flat overall, and may have fallen slightly in real terms between 2011 and 2015 (see Table 1).[footnote 24] Total employer expenditure has fallen by an estimated 3% in real terms, the amount per person trained and per employee has also fallen by 19% and 6% respectively. Investment in management training has increased by 18% suggesting that training for most other categories of employees has fallen.

The picture across UK countries varies significantly. In Scotland, total employer spend on training increased by 24% and the amount per employee rose by 20%. In England, total employer skills training expenditure fell by 2% whilst spend by employee remained static. In Wales and Northern Ireland, however, both these amounts fell, and by larger amounts than in England.

Figure 3: Average expenditure on CVT courses per employee by enterprises in the EU-28, 2005 to 2015, euro[footnote 25]

Source: Eurostat ‘Cost of CVT courses by type and size class - cost per person employed in all enterprises [trng_cvt_17s].’ Selected countries shown.

Table 1: Real terms spending by employers on skills by type of investment (UK), 2011 to 2015

| 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | Percentage change 2011 to 2015 | |

| Total (£ bn) | 46.8 | 44.4 | 45.4 | -3% |

| On job (£ bn) | 24.3 | 22.4 | 22.5 | -7% |

| Off job (£ bn) | 22.5 | 22.0 | 22.9 | 2% |

| Training cost minus wages/opportunity cost (£ bn) | 23.9 | 22.0 | 23.8 | 0% |

| Fees to external provider (£ bn) | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.2 | -24% |

| Management training (£ bn) | 6.5 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 18% |

| Per person trained £ thousand) | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.6 | -19% |

| Per employee (£ thousand) | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | -6% |

Source: Employer Skills Survey various years, taken from New Economy (2017)

3.4 Government investment in adult skills

The levels of government investment in adult skills in England seem to be decreasing over time. Broadly, since 2013 to 2014, some of the grant component of the Adult Skills Budget[footnote 26] has been replaced by loans – an example of shifting resources from the state to the private sector, so while the overall budget allocations are similar, the composition of the budget has moved away from government and towards individuals and employers.

The adult further education budget comprises the Adult Skills Budget (the majority of the adult further education allocations) and also smaller funding areas, such as the offender learning and skills service and community learning. The Adult Skills Budget fell by 34% in real terms (29% in cash terms) between 2010 to 2011 and 2015 to 2016.

From 2015 to 2016, the Adult Skills Budget excluding apprenticeships was combined with community learning and discretionary learner support to create the Adult Education Budget. This new Adult Education Budget is set to continue falling in real terms (remain at the same level in cash terms) between 2015 to 2016 to 2019 to 2020. In contrast, 19+ apprenticeships and advanced learner loans funding allocations are set to rise substantially. However, not all of these increases will be government funded. Part of the 19+ apprenticeships funding increases will come from employers (from 2017 to 2018 through the apprenticeship levy), while advanced learner loans will be mostly borne by individuals themselves.

In 2019 to 2020, the total adult further education and skills budget is planned to be £3.78bn, up from £2.94 billion in 2015 to 2016 and £3.18 billion in 2010 to 2011 (cash terms).[footnote 27] In cash terms, this represents an 8% fall between 2010 to 2011 and 2015 to 2016, and a 29% rise from 2015 to 2016 to 2019 to 2020. However, by 2019 to 2020, loans and apprenticeships will comprise around half of the total adult further education and skills budget, up from a third in 2010 to 2011. In 2019 to 2020, advanced learner loans are expected to constitute 13% of the budget compared to just 7% in 2015 to 2016. Apprenticeships for people aged 19+ are expected to increase from 25% of the budget in 2015 to 2016 to around 38% of the budget in 2019 to 2020.

It should also be noted that the government’s Adult Education Budget is not fully spent each year. In 2016 to 2017, for example, at least £63 million was unspent,[footnote 28] equivalent to around 5% of the total amount allocated.[footnote 29] Some of the budget was used to support further education colleges generally. A possible explanation for some of the underspend is that it may arise due to restrictions on how money can be spent and lower demand for college-based courses, as full-time workers cannot always access them.

In addition, there is a move to devolve the Adult Education Budget to Mayoral Combined Authorities in England from 2019 to 2020. Such a move would allow local areas to work more closely with other organisations such as local enterprise partnerships and respond to local needs. However, the funding formula for calculating the grants to local areas has not yet been developed, and no financial plans have yet been announced for the Adult Education Budget going forward from 2020 to 2021 onwards.

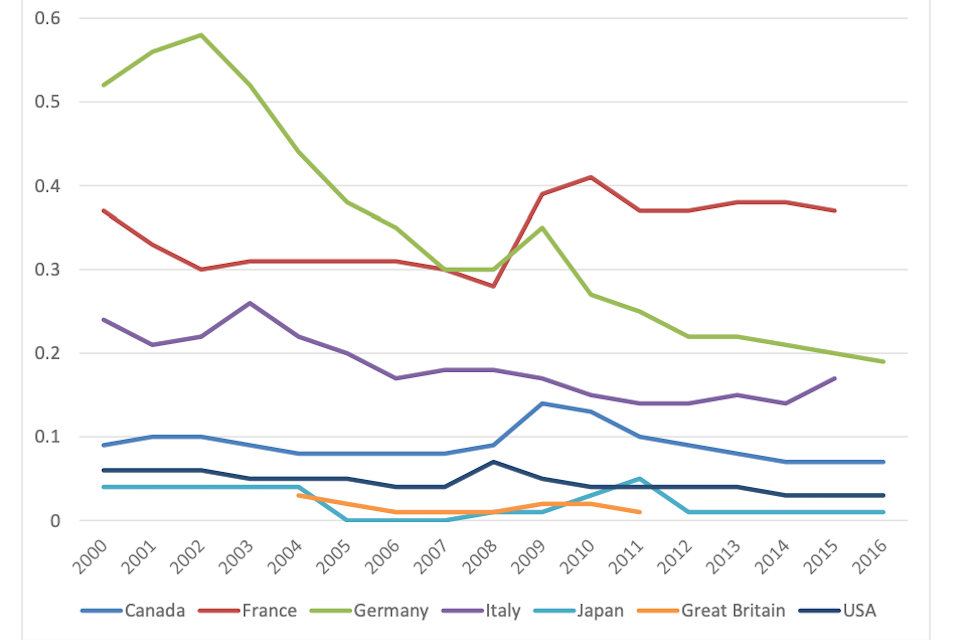

Government investment in training is also at comparatively low levels internationally. Comparing expenditure on training across countries is complicated due to differences in definitions and finding a comparable unit of measurement, therefore the analysis should be treated with caution. However, Figure 4 supports the argument that the UK tends to have internationally low levels of investment in skills. As a proportion of GDP, public expenditure on training in Great Britain was among the lowest of the G7 countries between 2004 to 2011, with only Japan at comparably low levels.

Figure 4: Public expenditure on training as a percentage of GDP, G7 countries, 2000 to 2016[footnote 30]

Source: OECD data 2000 to 2016

3.5 Individuals’ investment in and acquisition of adult skills

Most information about individuals’ financial investment in adult skills comes from data on learner loans. Several points have to be clarified before we discuss the data. First, any loans-based measure can only approximately measure individuals’ investment in adult skills, because it does not capture individuals’ private means spent on training or qualifications without taking out a loan – data on individuals’ own expenditure have to be found from other sources. Second, not all individuals will repay the full amount of their loans.[footnote 31] Regarding the largest component of individuals’ investments in adult skills, higher education loans, an estimated 83% of students will not repay the full amount, and if the amount outstanding is to be met by the government, this would contribute to the long-term government cost of higher education provision.[footnote 32] Third, higher education (HE) and further education (FE) are devolved policy areas, which means that each UK constituent country (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) decides its own policy on providing and financing these systems. Most estimates of learner loans are based on data for England only. Third, the HE and FE loans systems have been under considerable change in recent years, which results in a complex set of criteria about who repays what and under what conditions. This makes it quite difficult to compare changes in individuals’ investments in adult skills over time.

Undergraduate HE loans make up the bulk of all HE loan figures. Masters loans were introduced in April 2016,[footnote 33] and doctoral loans will come into effect from August 2018.

[footnote 34] In England, the most recent change to the amount taken out in student loans came in 2012 to 2013, when new entrants to HE faced tuition fees of roughly £9,000, compared to earlier cohorts, whose tuition fees were roughly £3,000.[footnote 35]

FE loans were introduced in August 2013, and were available to those aged 24 or older, studying for qualifications at levels 3 and 4 (A-levels/equivalent and certificate of higher education/equivalent). From August 2016, FE loans were expanded to people aged 19 or older, and extended the range of qualifications to include levels 5 and 6 (diploma of higher education/foundation degree/equivalent and degree/equivalent respectively).[footnote 36]

An estimate of individuals’ investment in education and training in England was undertaken based on the National Adult Learning Survey (see below), and data from the higher education and further education loans companies in 2014 to 2015. Individuals’ expenditure in 2014 to 2015 was estimated to be at just under £4 billion, whilst higher education and further education loans (tuition and maintenance) totalled at around £11 billion, of which £0.12 billion was further education loans.[footnote 37] More recent data on higher education loans only show that the tuition and maintenance loans in England amounted to £12.8 billion in 2016 to 2017 (provisional figures).[footnote 38] This increase partly reflects the change in replacing maintenance grants in full by loans from 2016 to 2017.[footnote 39]

Investments made by individuals appear to be the only category of skills spending to rise, however, these data are difficult to compile and compare over time, as discussed above. The evidence for this claim comes from looking at individuals’ learner loans, and assuming that all loans in their entirety are to be repaid by individuals. The data suggest that individuals’ learner loans, and predominantly HE loans, have increased over time. In 2014 to 2015, the Student Loans Company reported £10.7 billion loan funding (of which £3.7 billion was for maintenance), an increase of £4.7 billion since 2010 to 2011.

Regarding participation in HE and FE, it is worth highlighting that for those participating in first degrees across all modes of study (full- and part-time), the proportion of students aged 25 or over fell from 20% in 2012 to 2013 to 16% in 2017 to 2018.[footnote 40] Looking just at disadvantaged students, the number of part-time students (who are mostly older) from low-participation areas (POLAR3 Q1) has fallen by 47% since funding changes in 2011 to 2012.[footnote 41] For those on postgraduate courses, the proportion of people on taught courses (predominantly masters courses) aged 25 and over fell slightly (65% and 62%), while for research courses it remained broadly unchanged (78% and 77%) over the same period. Further education participation levels in England were at 2.3 million aged 19 and older in government-funded adult education in 2015 to 2016, down from around 3.1 million in 2010 to 2011.[footnote 42]

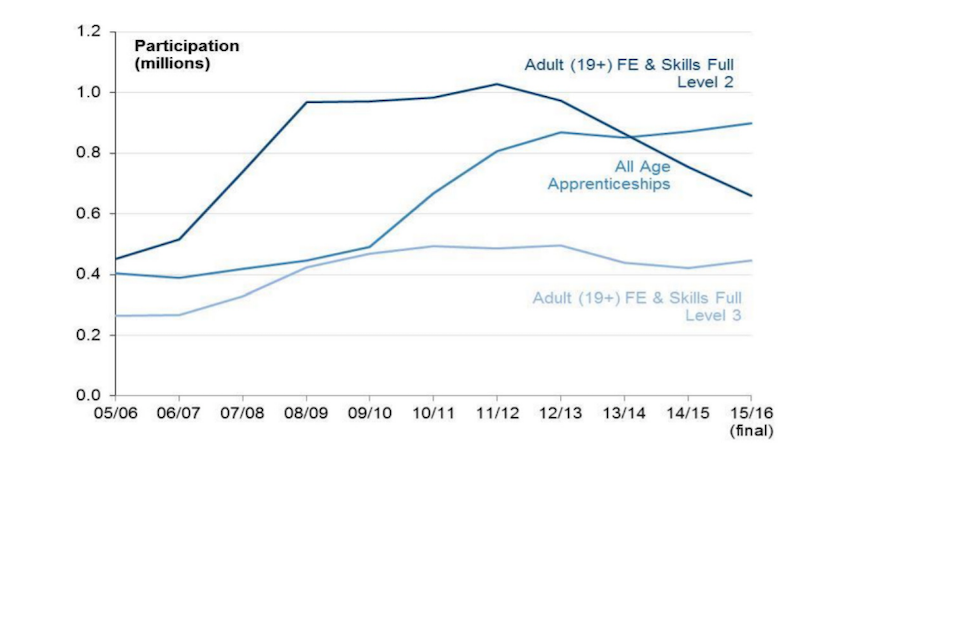

Regarding FE, the data suggest that overall, adult (19+) participation has been decreasing since 2010 to 2011. In particular, the number of people enrolled on Full Level 2 courses has fallen considerably since 2010 2011, Full Level 3 participation was slightly lower than in 2010 to 2011, while the number of apprenticeships (at all ages) has been increasing. Apprenticeship figures increased between 2004 to 2005 and 2016 to 2017 as eligibility criteria were relaxed, extending apprenticeship availability to people aged 25 or over.[footnote 43] Of apprenticeship starts in 2016 to 2017, almost half (46%) went to those aged over 25, up from just over a third in 2013 to 2014.[footnote 44] However, apprenticeship starts have fallen by about 28% since the introduction of the apprenticeship levy in 2017 (with 261,200 starts from August 2017 to March 2018 vs. 362,400 from August 2016 to March 2017).[footnote 45]

Additionally, apprenticeship figures should be treated with some scepticism as there have been suggestions that some employers have been rebranding training as apprenticeships, or offering low-skilled jobs as ‘apprenticeships’.[footnote 46] Such rebranding may be further encouraged by the introduction of the apprenticeship levy. A recent CIPD survey of business leaders and HR professionals found that just under half thought that their organisation would be encouraged to ‘rebadge’ existing training activity as apprenticeships in an effort to recoup some of the levy monies.[footnote 47]

Figure 5: Full Level 2 and Full Level 3 Adult (19+) Further Education and Skills, and All Age Apprenticeship Participation (2005 to 2006 to 2015 to 2016)

Source: Figure taken from Department for Education and Skills Funding Agency. (2017). Further education and skills in England. SFA/SFR36. 17 November 2016, updated 15 December 2017. Note that Adult (19+) Further Education and Skills includes 19+ Apprenticeships.

Thus, the picture of the changing investment in adult skills over time suggests that government investment in adult skills has fallen, employer investment in adult skills has remained broadly unchanged, and individuals’ own investment into adult skills, as measured by learner loans, has risen. However, the complex loan system and repayments arrangements means that it is difficult to say who ultimately pays for what proportion of higher education, and how that affects government and individual levels of investment in adult skills.

4. Who receives training?

4.1 Key findings

About 1 in 4 adults undertook job related training in the last 3 months in 2017. However, there is evidence of a general decrease in the proportion of people participating in training, particularly younger age groups, that has been occurring since the 2000s.

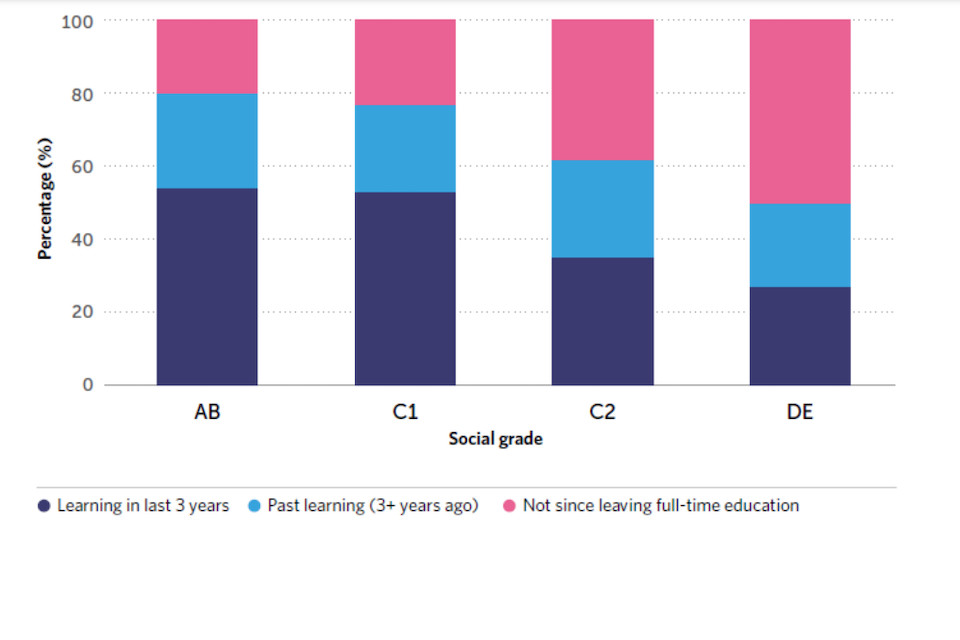

Almost half of people (49%) from the lowest social grades had not undertaken any learning since they have left school,[footnote 48] and people from lower social grades were much less likely to participate in any training, let alone training in the past 3 years, than those from more advantaged social grades (see Figure 6).

A higher percentage of people who were employed in the higher managerial, professional and associate professional occupations – women especially – participated in training compared to people who were employed in either intermediate, and routine and manual occupations.

In each respondent NS-SEC group, a slightly higher percentage of people whose parents worked in the managerial and professional occupations participated in training compared to those whose parents worked in intermediate, and routine and manual occupations.

In 2017, a slightly higher percentage of women than men participated in training (26% compared with 21%). A higher proportion of people from Black ethnic backgrounds compared to white people, and younger people compared to older people did some training in the last 3 months.

This section presents selected descriptive statistics about who undertakes job-related training or education in the UK.[footnote 49] As this section draws on the findings from other research, different measures of social class or group, and education and training are used.

The 2015 Adult Participation in Learning Survey found that almost half of people (49%) from the lowest social grades had not undertaken any learning (any education or training) since they left school,[footnote 50] and people from lower social grades (DE and C2) were much less likely to participate in any training, let alone training in the past 3 years, than those from more advantaged social grades (AB and C1, see Figure 6).[footnote 51]

Figure 6: Adult participation in learning by socio-economic class, 2014

Source: Taken from Walport and Leunig (2017), p. 86, and originally in NIACE (2015), p 2.

Focusing only on training provided by employers, the 2012 Adult Participation in Learning Survey[footnote 52] found that 24% of those in social grade AB participated in training at work, followed closely by those in C2. Those in C1 (14%) and DE (12%) were the least likely. But those in AB (broadly equivalent to NS-SEC professional and managerial occupations, 18%) were much more likely to undertake off-the-job training than those in C1 (broadly equivalent to NS-SEC intermediate occupations, 8%), C2 (7%) and DE (4%), both broadly equivalent to NS-SEC routine and manual occupations.

In contrast, state funded training is targeted at the people from most deprived communities, as Figure 7 shows. In 2004 to 2005, 24% of government-funded training supported those from the most deprived areas, compared to 17% from the least deprived. By 2013 to 2014, funding on those from the most deprived areas increased to 31%, and those from the least deprived fell to 14%. However, what the figures do not show is the incidence of training on the most and least deprived individuals as opposed to residents of areas with different levels of deprivation.

Figure 7: Profile of government-funded learners by IMD quintile, 2004 to 2005 and 2013 to 2014

Source: Taken from Gloster and others (2016), p. 37

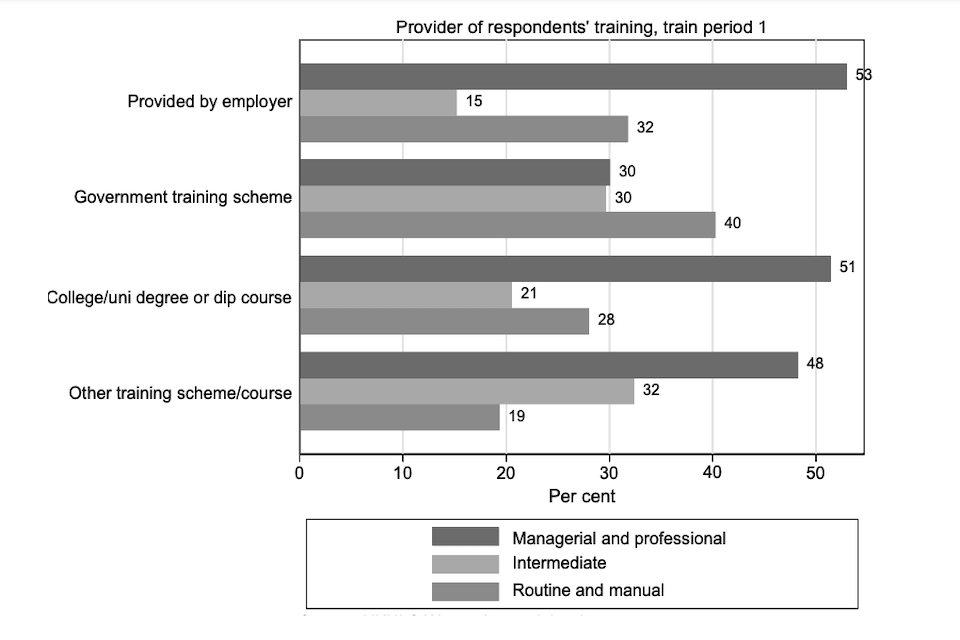

Using the UKHLS, we also find that of those who did government-provided training, a higher proportion of people worked in routine and manual occupations compared to those whose training was provided by employers and other providers. Of all the people who had done training provided by the government, 40% worked in routine and manual occupations, while of those who undertook employer-provided training, 32% worked in routine and manual occupations (see Figure 8). This is consistent with the literature that suggests that government training courses tend to be targeted at people from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

The proportion of people accessing government-provided training from routine and manual occupations was higher than in the population as a whole. LFS data show that in 2017, of adults aged 25 to 64 in employment, 47% were in managerial and professional occupations, 24% in intermediate, and 29% in routine and manual occupations. In 2010, the corresponding figures were 47%, 22% and 31% respectively (there was a slight fall in the proportion of people working in routine and manual occupations in the population between 2010 and 2017).

Figure 8: Distribution of people by NS-SEC within each category of training provider (training spell 1, UKHLS)

Source: UKHLS, waves 2 to 7 combined, adults aged 25 to 64 in employment only, training period 1 only, weighted.

The further education sector is also instrumental in providing learning and skills opportunities, especially for disadvantaged adults.[footnote 53] The Adult Skills Budget, Community Learning, and ESF programmes are important for adults living in disadvantaged areas, people with low or no qualifications, women and people from Black and Minority Ethnic communities. However, these budgets have been cut and support for many qualifications having the greatest impact on earnings (Level 3+)[footnote 54] have been replaced with learner loans. Moreover, recent findings suggest that further education may reinforce, rather than eliminate, social inequalities, by predominantly benefitting individuals from higher class backgrounds who work in lower-class positions with a vehicle for career advancement, rather than providing effective second-chances to individuals from lower class origins to advance their careers.[footnote 55] Part-time higher education is another option for adult skill building, but changes to government funding in 2011 to 2012 led to a 47% decrease in the number of students from disadvantaged areas (POLAR Q1) entering higher education.[footnote 56]

In terms of who participates in training, NALS 2010 data suggest that the economically inactive (such as retired people and those looking after the family) were the least likely to participate in training (40%, BIS, 2012).[footnote 57] This compares with 64% of unemployed people, 72% of part-time employees and 81% of full-time employees.

In addition, there is evidence of a ‘virtuous circle’ of learning: people with higher levels of qualification are more likely to participate in training, and possessing a qualification appears to have an even stronger effect than parental education levels. In 2010, over one quarter of those with no qualifications (27%) participated in training, compared with 55% of those with a Level 1, 73% of those with a Level 2 and 90% of those with a Level 5 qualification (BIS 2012).[footnote 58] Similar findings have been well-evidenced in the literature.[footnote 59] This suggests that getting people, at whatever level, to gain a qualification has further positive impacts. The NALS also found that parental education played a role but not as significant as possessing a qualification. Of those who had both parents leave full-time education and training at 16, 65% participated in training. This compares with 81% of those who had at least one parent stay on post-16, and 84% of those where both parents stayed on.

The virtuous circle of learning is reinforced by the findings from the 2015 NIACE Adult Participation in Learning Survey, which found that of current learners, 82% were likely to take up training in future, and 68% of those who have undertaken training in the past 3 years. Of those who had not undertaken any training since leaving full- time education, only 17% planned to undertake training, and although 29% of this group have participated in training, this was more than 3 years ago.

Suggestions to improve take-up of training among people from more disadvantaged backgrounds (for example, those with low skills, those in poor-quality and insecure jobs) have included personal learning accounts,[footnote 60] although some concern was raised about the extent to which disadvantaged adults would be able to contribute to such accounts financially. The IPPR (2017) has called for personal training credits to be made available to adults, with the amount depending on whether or not they are in work, on pay, and on existing qualification levels.[footnote 61] The aim is to encourage co-finance between individuals and the state, and at the same time to alleviate the burden on those most in need.

The effect of lifelong learning on intra-generational social mobility: evidence from longitudinal data in the United Kingdom. London: Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills. However, it is not clear how cost-effective or how influential the personal training credits would be. The main rationale in the IPPR report draws on personal health budgets in England, and it is not necessarily the case that personal budgets for skills would be used in a similar way.

Other avenues for improving take-up of training for disadvantaged adults include making use of the National Retraining Scheme and ensuring that some of the programmes in development actively target skill development for people who need it most.

4.2 Participation in job-related training in 2010 and 2017

To recap, we focus on who participated in job-related training or education in the last 3 months (unless stated otherwise), and hereafter refer to this as ‘training’ for short. This LFS question applies to all those who were aged 16 to 69, and who were either in employment or undertaking education/training. In addition, the analysis focuses only on adults aged 25 to 64 who were in employment at the time of the survey. This gives us 41,520 adults aged 25 to 64 in employment in the 2010 July to September LFS, and 36,656 adults in July to September 2017. The drop in the number of adults may be because of a downward trend in survey response rates.[footnote 62] That our sample of analysis is limited to 25 to 64 year old adults in employment suggests that the vast majority of responses to this question will likely involve training rather than education. This does include any part-time education but learner numbers are very low.[footnote 63]

In this section, we look at the descriptive statistics from the LFS about people in the UK who participated in job-related training or education by country of residence, sex, ethnicity, age group, highest qualification held, whether one was working full- or part- time, in the private or public sector, and by current socio-economic status and socioeconomic origin (parental background). Our analysis is weighted to show population-representative percentages.[footnote 64]

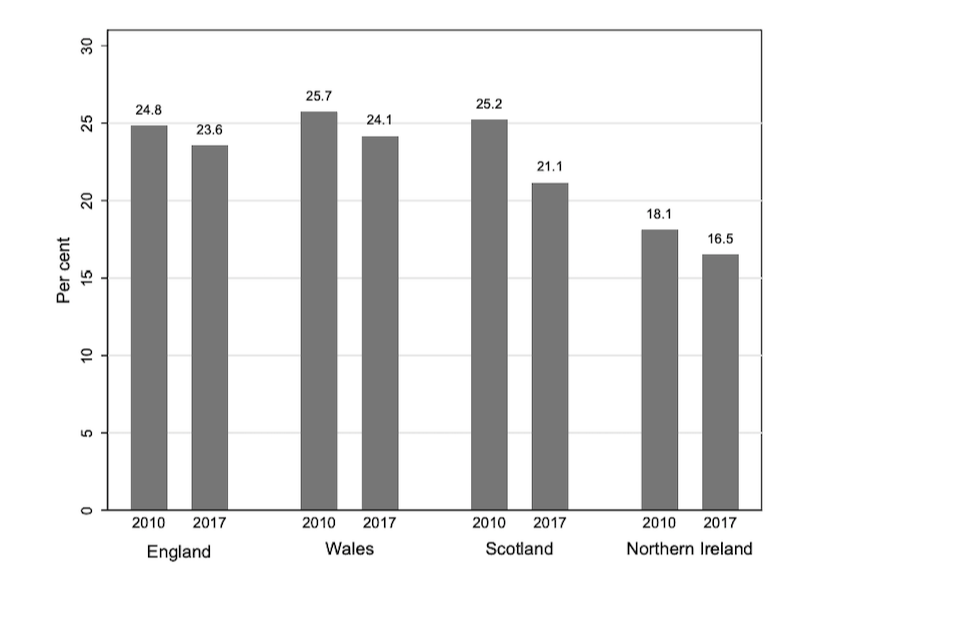

About 1 in 4 people in employment accessed job-related training or education in the last 3 months, falling slightly from 24.7% of adults in 2010 to 23.2% in 2017.[footnote 65] This may be a continuation of a longer-term trend of the percentage of people participating in job-related training or education declining since the 2000s (although with variation by age group),[footnote 66] and see also Figure 17). It may also have arisen due to chance – when we are looking at 2 different points in time (2010 and 2017) we miss the variation between the 2 periods. Whichever explanation applies, the overall difference between 2017 and 2010 is negligible.

The percentage of adults participating in training varies slightly by UK country of residence, with Northern Ireland having the lowest incidence of job related training in 2017, at around 18% in 2010 and 16% in 2017 (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by country

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted. This is calculated by looking at the weighted proportion of people who answered that they had some training in the last 3 months, and looking at how that proportion changes between 2010 and 2017 in different countries in the UK.

4.3 Type of training

The LFS contains limited data on the type of training accessed by respondents, and sometimes, additional questions about training are only asked in certain quarters. As we are primarily working with the July to September quarter (because this quarter contains the social mobility question), we can look into whether the training accessed was predominantly on- or off- the job. On-the-job training refers to “learning by example and practice while actually doing the job.”[footnote 67] Training that is on the employer’s premises but done in a classroom setting or as a training session does not count as on-the-job training, and is instead treated as ‘off-the-job’. These types of training can be loosely interpreted as informal (on-the-job training) and formal (off-the-job), even though not all training that is away from the job will lead to a qualification, and some may include induction training, and health and safety training. However, owing to small sample sizes, we cannot disaggregate the type of training in the LFS any further.

The question about whether the training was on- or off-the-job only applies to those people who replied that they have been involved in training in the last 4 weeks, rather than the last 3 months. Around 11% of adults participated in training in the last 4 weeks, and this proportion has not changed between 2010 and 2017. Of those 11% of adults who participated in training in the last 4 weeks only, a higher proportion did training that included some off-the-job training in 2010 (59%) compared to 2017 (50%). While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions, the data raise the possibility that the incidence of formal training may have declined between 2010 and 2017.

Insight from UKHLS suggests that the most frequently mentioned reasons for undertaking training was to improve skills in one’s current job or to maintain one’s professional status / to meet occupational standards (62% and 45% of respondents who had done some training mentioned these as reasons for at least some of their training, see Figure 10). Just over a fifth of respondents who had done training in a previous year mentioned doing so to prepare for a potential future job, and a similar proportion undertook for health and safety training. Induction training and training for non-job-related reasons were least frequently mentioned as reasons for doing training (only 6% of respondents).

Figure 10: Reasons for which training was done (UKHLS)[footnote 68]

Source: UKHLS, waves 2 to 7 combined, adults aged 25 to 64 in employment only, training period 1 only, weighted. Note that a respondent could pick multiple reasons for training. We also looked at the reasons in each wave separately (not reported), but the pattern was broadly similar to that above.

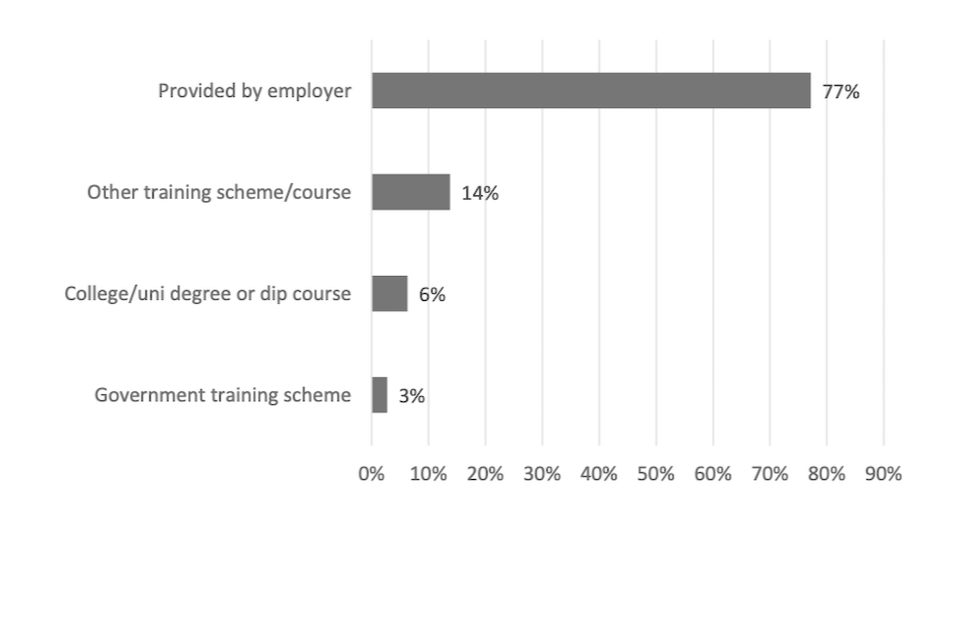

4.4 Training by funding source

We also used UKHLS to look at who provided the training accessed by individuals, again focusing on the first training period (Figure 11). Of all training accessed, most was provided by the employer (77%) compared to other training schemes or courses (14%) and education institution courses (including college or university degrees and diploma courses, 6%). Government schemes constituted only 3% of training courses accessed by individuals (care should be taken when interpreting this statistic).[footnote 69] However, as set out before, government-funded training only constitutes around 7% of the overall training spend (see Figure 1), and so funds only a minority of training activities.

Figure 11: Training accessed by individuals by different providers (UKHLS data)[footnote 70]

Source: UKHLS, waves 2 to 7 combined, adults aged 25 to 64 in employment only, training period 1 only, weighted. Note that a respondent could pick only one training provider for each period of training. We also looked at the reasons in each wave separately (not reported), but the pattern was broadly similar to that above.

4.5 Access to training by socioeconomic factors and other characteristics

Occupation

Look at participation in training by respondents’ occupation, LFS analysis shows that a higher percentage of people working in high paid, high skilled professional, associate professional and technical, and personal service occupations[footnote 71] participated in training than those working in other occupations (30 to 35% in 2017, compared with 21% for those in managerial occupations and 13 to 16% for those in the remaining occupations).

Between 2010 and 2017, the proportion of people participating in training by occupation decreased for most occupational groups. The decrease was significant for people working in the professional, associate professional and technical, and personal service occupations (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by main occupational group

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted. SOC 2000:

-

Managers and senior officials (for example, MP, company chair, shopkeeper)

-

Professional occupations (for example, scientist, teacher, solicitor, doctor)

-

Associate professional & technical occupations (for example, nurse*, police officer, financial advisor, estate agent)

-

Administrative and secretarial occupations (for example, office assistant, receptionist, secretary)

-

Skilled trades occupations (for example, gardener, mechanic, builder, apiarist, plumber)

-

Personal service occupations (for example, tourist agent, teaching assistant, flight steward)

-

Sales and customer service occupations (for example, cashier, call centre operator)

-

Process, plant and machine operatives (for example, foreman, machinist)

-

Elementary occupations (for example, postman, waiter, bar staff, cleaner, security guard).

*Note that in SOC 2010, nursing and related occupations were reclassified into professional occupations.

However, managers and senior officials – the highest occupational group – received lower levels of training than professional and associate professional and technical occupations. This is likely to arise from the different types of managers included in this occupational group: Managers, Directors and Senior Officials include company directors, members of parliament, as well as small business owners, shopkeepers, etc. Some of these types of occupation (such as senior managers), are likely to have high levels of training, and others (for example, shopkeepers) lower levels of training. For example, in 2017, 22% of people working as corporate managers and directors did training, while only 16% of people working as other managers and proprietors did training, according to the LFS.

Second, Managers, Directors and Senior Officials have a higher proportion of people who are self-employed than other occupational groups. It is well-evidenced that people who are self-employed are also less likely, on average, to participate in training compared to employees. Indeed, in 2017, 25% of employees participated in training in the last 3 months compared to 13% of those who were self- employed. But, it is not only Managers, Directors and Senior Officials that have a high proportion of self-employed workers (17% in 2017). Of people working in Associate professional and technical occupations, 15% were self-employed, and of those in the professional occupations – 14%. Therefore, the self-employed explanation does not tell the full story.

A third explanation may be that most workers in more senior occupations, such as professional occupations, are more likely to be older and therefore will have experienced training throughout their career. People employed in the Managers, Directors and Senior Officials occupational group are on average around 44 years old compared to those in the professional occupations, who are on average aged 42. However, there is relatively little variation in the mean ages across the 9 occupational major groups.

Socioeconomic background – respondent NS-SEC

Finally, we look at respondents’ current socioeconomic status, and that of their parents’. As mentioned earlier, since 2014 the LFS has been capturing data on the occupation of the main wage earner in the household when the respondent was aged 14. Because the main wage earner was likely to be a parent, we refer to this variable as the parental occupation, and use it to derive the parental socioeconomic status, the NS-SEC.[footnote 72] The parental NS-SEC is used as an indicator of the respondent’s socioeconomic background.

To see how jobs (or SOC occupations at the 4-digit level) relate to the NS-SEC, the ONS NS-SEC coding tool can be used. The table below gives just an example of the kinds of occupations that are associated with the NS-SEC (Table 2).

Table 2: NS-SEC Categories (2011 census data, England only)[footnote 73]

| NS-SEC category (3-class) | NS-SEC category (8-class) | Examples of jobs | Number of people (usual residents aged 16 to 74) | Percentage |

| 1. Higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations | 1. Higher managerial, administrative & professional occupations | Lawyers, Architects, Medical doctors, Chief executives, Economists | 4,045,823 | 11.4% |

| 2. Lower managerial, administrative & professional occupations | Social workers, Nurses, Journalists, Retail managers, Teachers | 8,132,107 | 23.0% | |

| 2. Intermediate occupations | 3. Intermediate occupations | Armed forces up to sergeant, Paramedics, Nursery Nurses, Police up to sergeant, Bank staff | 4,972,044 | 14.1% |

| 4. Small employers and own account workers | Farmers, Shopkeepers, Taxi drivers, Driving instructors, Window cleaners | 3,662,611 | 10.4% | |

| 3. Routine and manual occupations | 5. Lower supervisory and technical occupations | Mechanics, Chefs, Train drivers, Plumbers, Electricians | 2,676,118 | 7.6% |

| 6. Semi-routine occupations | Traffic wardens, Receptionists, Shelf- stackers, Care workers, Telephone Salespersons | 5,430,863 | 15.4% | |

| 7. Routine occupations | Bar staff, cleaners, labourers, Bus drivers, Lorry drivers | 4,277,483 | 12.1% | |

| *Never worked and long-term unemployed | 8. Never worked and long-term unemployed | N/A | 2,180,026 | 6.2% |

| Total | 35,377,075 | 100.0% |

Source: Modified from Table 1, UK Parliament Education Committee (2014), originally from Office for National Statistics, 2011 census, Table KS611EW.

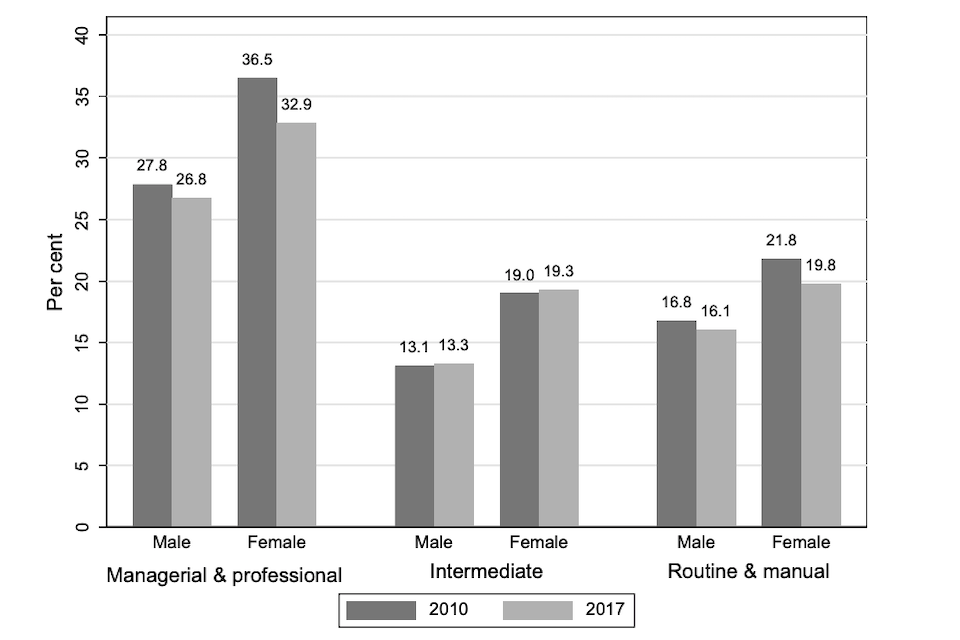

In the LFS data, we find that in 2017, a higher percentage of people who were employed in the higher managerial, professional and associate professional occupations – women especially – participated in training compared to people who were employed in either intermediate and routine and manual occupations (30% compared with 16% for intermediate occupations and 18% for routine and manual occupations respectively, see Figure 13). A possible explanation for the slightly lower incidence of training for those employed in the intermediate occupations compared to the routine and manual occupations could be that the intermediate occupations include the self-employed, and it is well-documented that the self-employed are less likely to undertake training than employees. In the 8-class NS- SEC, the intermediate occupations and small employers and own account workers (both of which form the 3-class NS-SEC) exhibit different patterns of undertaking training (see technical annex).

As before, a slightly higher percentage of women than men participated in training across each socioeconomic group. Between 2010 and 2017, the percentage of women employed in managerial and professional and routine and manual occupations who participated in training decreased slightly (37% to 33% – 22% to 20% respectively) but the change was negligible for men and women in other NS- SEC groups.

Figure 13: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by their own current 3-category NS-SEC

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

Socioeconomic background – parental NS-SEC

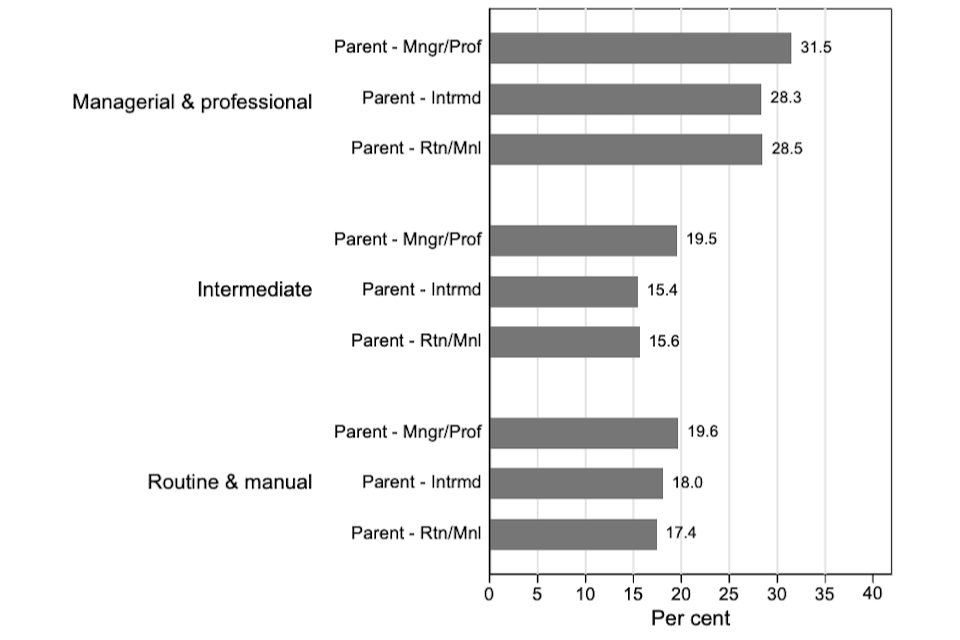

It is also possible to look at the proportion of people participating in training by the NS- SEC of their parent. Overall, in 2017, 27% of people whose parent had a managerial or professional background participated in training in the last 3 months, compared to 22% for those whose parents were from an intermediate background, and 21% – from a routine and manual background.

Within each respondent’s NS-SEC category for their current job in 2017, the data show that a slightly higher percentage of people whose parents worked in the managerial and professional occupations participated in training compared to those whose parents worked in intermediate and routine and manual occupations (Figure 14). This pattern holds even though the percentage of people participating in training was higher overall for respondents who worked in the managerial and professional NS-SEC groups than in others. This suggests that those whose parents were working class are less likely to do training than if their parents were middle class, even though they are doing the same job, and we explore this possibility more fully in the next section.

We find that, when taking the personal and work-related factors discussed above into account (such as gender, employer size and current occupation), parental background does not affect the likelihood of accessing training in a significant way. However, while we find no evidence of a direct effect this does not mean that parental class does not matter. There is widespread evidence that parental background affects children’s educational attainment and through that – occupational attainment.[footnote 74] We expand on this point more fully in the next section.

Intervening factors may come into play which explain why there are differences. For example, the availability of training may be related to the specific occupational group in which people currently work. There are also differences in the type of job-related training. For example, some job-related training is off-the-job and leads to a qualification. Such training may be of better quality than on-the-job training that does not lead to a qualification. It may also be the case that those from managerial, professional and associate professional backgrounds are more likely to access such higher-quality training than those from other socioeconomic backgrounds. Regardless of the job of the individual, however, a slightly lower proportion of people undertake training if their parents were working class than if their parents were middle class.

Figure 14: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017, by their current 3-category NS-SEC and parental NS-SEC

Source: Labour Force Survey 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

Qualification level

There is a clear decreasing relationship between the proportion of people who undertook training or education and the highest qualification held (Figure 15). These descriptive statistics from the LFS show that a higher proportion of people holding a degree-level qualification have accessed training in the last 3 months, while the lowest proportion of people accessing training was amongst those who had no qualifications. Indeed, the proportion of people with degrees who accessed training was more than 3 times higher than that of people with no qualifications. This finding has been well-evidenced elsewhere in the literature, as we discussed above, and suggests that there may be a ‘virtuous circle’ of training accruing to people who already have high levels of qualifications, and who already participate in training.

The percentage of people who received training or education in the last 3 months declined for everyone between 2010 and 2017, irrespective of highest qualification held. The decline was most pronounced for those who had higher education qualifications below degree level (such as a foundation degree or diploma of higher education), or a national vocational qualification (NVQ) at levels 4 and 5. While the ‘no qualification’ group shows a small increase, this change is not statistically significant.

Figure 15: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by highest qualification held

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

Sex

In 2017, a slightly higher percentage of women than men participated in training (26% compared with 21%). These figures are consistent with other research that has found that women are more likely to have undertaken training in the last 3 months than men.[footnote 75]

According to the LFS, the proportion of men and women who did training and/or education in the last 3 months declined slightly between 2010 and 2017 (see Figure 15), but the decline was statistically significant for women only. We discuss later that the reason for this may be related to the decrease in the incidence of people doing training in the public sector, which tends to employ more women than men, and where the provision of training tends to be higher than in the private sector (see p.47).

Figure 16: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by sex

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

Ethnicity

In 2017, analysis of the LFS found that a higher percentage of people from Black or Black British ethnic groups participated in job-related training or education in the last 3 months (32%) compared with people from Mixed/Other ethnic backgrounds (24%), White (23%) and Asian/Asian British ethnic backgrounds (20%, see Figure 17).[footnote 76]

The percentage of people who participated in training or education in the last 3 months decreased between 2010 and 2017 across all ethnic groups. The decrease was almost negligible for people from White backgrounds, although more pronounced for others (not significant for people from Black or Black British backgrounds).

Existing research has reported that men from Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds in employment tend to receive least training (Cheung and McKay, 2010), that Pakistani and Bangladeshi adults were less likely to participate in adult learning, and that Bangladeshi and Black Caribbean adults were less likely to do job-related training (Bhattacharyya and others, 2003). Not much literature on ethnic background and participation in training is available.

Figure 17: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by ethnic group

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

Age

Consistent with findings in the literature, analysis of the LFS shows that a higher percentage of younger adults than older adults participated in job-related training or education in the last 3 months (Figure 17). While other research suggests that younger people (aged 16 to 24) tend to have the highest rates of training, and have also experienced some of the highest falls in training over the last decade or so, we do not include them in this research.

Consistent with findings from other research that suggests that younger adults have experienced a decline in the incidence of training, we found that the proportion of people accessing training between 2010 and 2017 fell by a larger amount for younger adults than for older adults. In 2010, 28% of adults aged 25 to 29 had accessed training in the last 3 months, compared to 24% of those aged 30 to 64. In 2017 a quarter (25%) of 25 to 29 year olds undertook training, compared to 23% for those aged between 30 to 64.

Between 2010 and 2017, the percentage of people who did job-related training or education in the last 3 months declined across most age groups, except for the over 55s, where it rose slightly.

Figure 18: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by age group

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

These findings support a large literature that shows that participation in training decreases with age. The reasons for this, discussed in the literature, include the argument that as older workers near retirement there is less incentives for employers to provide training as they would have less time in which to recoup the costs of training, (any training provided may be less costly to the employer and of lower quality for the same reason), that older workers may be less likely to be motivated to undertake training, and that older workers may be perceived as being less adaptable – less able to learn, take on and implement new knowledge (Zwick, 2015; Cully and others, 2000).[footnote 77] An ageing population may, however, challenge some of these arguments and encourage employers to invest in older workers, and older workers to take up more training opportunities.

Next we look at the descriptive statistics between selected job-related characteristics and the proportion of people in employment accessing education and training. The main characteristics we investigate here are: whether the job is full- or part-time, whether it is in the private or public sector, and workplace size.

Full-and part-time work

LFS analysis shows that a slightly higher percentage of people who worked full time participated in training compared to those who worked part-time, in both 2010 and 2017 (21% who worked part-time and 24% – full-time in 2017, Figure 18).[footnote 78]

Potential reasons for differences in the proportions of people who participated in training who worked full- and part-time may be that employers may be less inclined to invest in part-time workers as they would get less of a return compared to that on full-time workers, and that part-time workers may have different levels of commitment to the organisation compared to full-time workers.[footnote 79]

Figure 19: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by full- or part-time job

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

Public and private sector

However, of those employed in the public sector, a much higher proportion participated in training than those employed in the private sector, almost double (36% in and 19% respectively in 2017, Figure 19).

Figure 20: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by public or private sector

Source: Labour Force Survey 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

A possible explanation could be that there is a different distribution of occupations in the public and private sectors, such that a higher proportion of lower-skilled occupations are concentrated in the private sector, and a higher proportion of higher-skilled occupations – in the public sector. As has been discussed earlier, people in lower-skilled jobs tend to participate less in training, and so those in the private sector may be more likely to train less. This is borne out by the data, we find that a higher proportion of professional, associate professional and technical, and personal service occupations are found in the public than in the private sector (see technical annex). People working in higher level occupations tend to receive higher levels of training.

Another possible explanation is that public sector organisations tend to be larger employers, and provision of training is positively correlated with the employment size of the organisation (see below). Other explanations include: public sector workers being more unionised; having traditionally had a culture of investing in learning and development; and have more regulation concerning minimum qualification levels (for example, those in health and social care personal service roles).

Workplace size

As mentioned above, it is well-evidenced that larger firms tend to invest in job related training more than smaller firms.[footnote 80] Although workplace size does not measure firm size directly (as a company may have several workplaces), in general, there is a high correlation between workplace size and company size.

LFS analysis finds that the relationship between workplace size and participation in training was as expected – a lower proportion of people working in smaller workplaces participated in training than those working in larger workplaces (Figure 20). In 2017, 31% of people in organisations employing 500 or more employees received job related training compared to 22% of those with fewer than 50 employees. While the proportions of people who did training or education in the last 3 months decreased between 2010 and 2017 across all workplaces, the change was not significant for people working in workplaces with fewer than 50 employees.

Figure 21: Percentage of people who participated in training in 2017 and 2010, by number of employees at workplace

Source: LFS 2010 and 2017, July to September quarter, people aged 25 to 64 in employment, weighted.

5. What affects the likelihood of doing job-related training or education?