Valuing culture and heritage capital: a framework towards informing decision making

Published 21 January 2021

Applies to England

Authors: Harman Sagger, Jack Philips, Mohammed Haque

Executive summary

This document sets out DCMS’s ambition to develop a formal approach to value culture and heritage assets. The programme’s ultimate aim is to create publicly available statistics and guidance that will allow for improved articulation of the value of the culture and heritage sectors in decision making.

The valuation of benefits and costs plays an important role in deciding how the government should spend taxpayers’ money. Sector specific guidance is already available to value the impact of interventions in crime, environment, health and transport. It is important that similar guidance is also available to help guide decisions on culture and heritage. The outputs of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will not only be applicable to the public sector, but can also act as a useful tool to assess the public benefit of private assets. Therefore, this approach can be used by anyone who wants to understand their impact on society.

The document sets out how DCMS will develop an approach to aid decisions on public funding that is consistent with Social Cost Benefit Analysis principles published in HM Treasury’s Green Book. The Green Book contains guidance issued by HM Treasury on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects. The role of appraisal and evaluation is to provide objective analysis to support decision making. Other capitals, such as natural capital, have a developed guidance. However, there is currently no guidance in HM Treasury’s Green Book specific to culture and heritage capital.

Economic methodology should be used alongside other information, both quantitative and qualitative, to create a robust evidence base for decision making. Therefore, while economic methodologies will take centre stage, a cross-disciplinary approach is needed ㅡ for example linking economic valuation methodologies to heritage science.

While the document is aimed at practitioners, and the programme will use complex and novel economic methods, the document is designed to be used and understood without prior knowledge of valuation methods or the culture and heritage sectors.

Alongside this document, DCMS has published a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) of culture and heritage valuation studies. This REA was conducted to assess the current state of the literature on valuing culture and heritage assets and compile a collection of studies that align with best practice.[footnote 1] The results are presented within an evidence bank of economic values including an assessment of the quality of each study and an overview of the valuation methods used.

We see this document as the first iteration of a Culture and Heritage Capital Framework which will be updated as work progresses. Therefore, we would like to hear from experts across the sectors and academia and have included a call for evidence for methodologies, research and data that can support the measurement of culture and heritage. Please contact chc@dcms.gov.uk.

Acknowledgements

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) is working closely with partners including Arts Council England and Historic England to develop the Culture and Heritage Capital approach. The programme has also sought guidance from leading experts with particular thanks to Professor David Throsby. This document has been endorsed by the Commissioner for Cultural Recovery and Renewal, Neil Mendoza and the Culture and Heritage Capital Advisory Board with the following membership:

| Name | Organisation |

|---|---|

| Lord Mendoza (Chair) | Commissioner for Cultural Recovery and Renewal, DCMS |

| Duncan Wilson OBE | Chief Executive, Historic England |

| Sir Laurie Magnus | Chairman, Historic England |

| Darren Henley OBE | Chief Executive, Arts Council England |

| Ros Kerslake OBE | Chief Executive, National Lottery Heritage Fund |

| René Olivieri | Chairman, National Lottery Heritage Fund |

| Sir Ian Blatchford | Chairman, National Museum Directors’ Council |

| Hasan Bakhshi MBE | Director, Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, Nesta |

| Prof Geoffrey Crossick | Professor, University of London |

| Prof Andrew Thompson | Former Executive Chair of AHRC and UKRI International Champion |

| Prof Ian Bateman | Professor, University of Exeter |

| Prof May Cassar | Professor, UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage |

| Prof David Throsby AO | Professor, Macquarie University, Department of Economics |

| Prof Susana Mourato | Professor, LSE, Department for Geography and the Environment |

Thanks goes to Adala Leeson, Andy Brown and Brenda Dorpalen (Historic England); Andrew Mowlah and Oliver Stephenson (Arts Council England); Ben Walmsley and Sue Hayton (Centre for Cultural Value); Anne Sofield (Arts and Humanities Research Council); Ingrid Samuel and Rebecca Clark (National Trust); Julia Lamaison (British Film Institute); Tom Walters (National Lottery Heritage Fund); Graeme Reeves (Canal & River Trust); Ben Cowell (Historic Houses); Kathryn Simpson (National Museum Directors’ Council); Dave O’Brien (The University of Edinburgh); Nikki Locke (British Council); Alastair Johnson and Colin Smith (Defra); Kate Clark (Transport for Wales); Ricky Lawton (Simetrica); and John Davies (Nesta).

1. What is included in this document?

This document sets out DCMS’s ambition to develop a formal approach to value the benefits of culture and heritage assets to society, called the culture and heritage capital approach. The programme’s ultimate aim is to create publicly available statistics and guidance that will allow for more accurate articulation of the value of services provided by culture and heritage. The publicly available resources (see Section 5 for more information) will include:

- supplementary guidance to the Green Book

- a database of values for a range of culture and heritage assets

- a set of culture and heritage capital accounts.

Over the coming years, DCMS will work with arm’s length bodies, academia and the wider sector to conduct robust analysis to support these aims. Some of the priority areas for future research (outlined further in Section 6) are:

- expanding valuations across asset types, including digital assets

- improving methodologies for valuation

- understanding how an asset’s condition changes using heritage science.

All of the guidance and research will be underpinned by the Culture and Heritage Capital Framework set out in Section 4, which explains the asset based approach the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme is taking. In short, the assets (such as paintings and historic buildings) are the “stock” that produce services or “flows”. Assessing how an intervention will increase or decrease these stocks and flows will enable an organisation to conduct an accurate Social Cost Benefit Analysis.

The scope of the programme will focus on both contemporary culture as well as heritage assets; the initial scope is outlined in Section 3.

Finally, the document includes a call for evidence for any research that can help develop the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme. Please contact the chc@dcms.gov.uk mailbox with your suggestions.

2. An introduction to culture and heritage capital

At present, there is no agreed method for valuing the flow of services that culture and heritage assets provide to the people and businesses that engage with them. This means these types of services are implicitly valued at zero, potentially leading to sub-optimal decisions around investments and maintenance.[footnote 2]

DCMS, together with its arm’s length bodies and stakeholders, will develop a formal approach for valuing culture and heritage called the culture and heritage capital approach, to address this gap in the evidence base.

2.1 What is culture and heritage capital?

In economics, there are three traditional forms of capital: physical, human and natural capital. Capital is generally defined as having two characteristics:

- Unlike a pure consumption good, a stock of capital delivers a stream of returns over time. Those returns can be financial – for example, a higher wage received as a result of gaining a qualification – or non-financial, such as a wellbeing benefit from visiting an area of outstanding natural beauty.

- Further, capital can depreciate, and that depreciation can reduce the present value of expected future returns.

In cultural economics, cultural capital is defined as ‘an asset which embodies, stores or gives rise to cultural value in addition to whatever economic value it may possess’ (Throsby, 1999).[footnote 3]

An art gallery or library, for example, provides many services to the public, such as being a place for recreation, learning and preserving local identity. These services are beneficial to the individual and society as a whole and therefore create value.

As set out by UNESCO , these assets can be categorised as physical assets such as buildings, plaques and monuments or nonphysical assets (also known as intangible cultural heritage) such as folklore, customs, beliefs and traditions.[footnote 4] Initially, the focus of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will be on physical assets; however, these physical assets will provide services that enable these traditions and knowledge to continue and therefore intangible cultural heritage will be partially evident within the estimates of value provided by the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme.

While debates have persisted as to whether it is appropriate to apply valuation methods to culture and heritage, there is greater acknowledgement of the need for the culture and heritage sectors to better articulate their impacts and value for money when it comes to public funding and to maximise the use of funds by better understanding the benefits of different investment options. Furthermore, there is greater recognition of the need to use economic methodologies prescribed by HMT’s Green Book, the central tool on how to appraise public funding and interventions, in order to make evidence-based economic cases for investment.

The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme is intended to add to the expanding area of work to identify and measure ‘missing capitals’. This already includes the natural capital approach from Office for National Statistics (ONS) and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) as well as ONS’s further work on Human Capital and Social Capital, where traditional methods of measuring the economy miss the full range of benefits to society.

2.2 Why measure the value of culture and heritage?

HM Treasury’s Green Book recommends expressing the full costs and benefits of a proposal in monetary terms (known as Social Cost Benefit Analysis).[footnote 5] It is important to understand that HMT’s Green Book follows a welfare approach, which means the goal of public policy is to increase public welfare. The Green Book provides theoretical foundations for particular instruments of public economics, including the concepts of market failure and Social Cost–Benefit Analysis (SCBA). This welfare approach should then value all benefits and costs, not just financial benefits such as jobs and other standard measures of economic output such as GDP. Infact GDP is an incomplete measure of public welfare and value added as it does not take into account assets and services that do not have market prices. Therefore, undertaking SCBA ensures the benefits of interventions outweigh the costs and the preferred policy option will deliver value for money and maximise public welfare relative to other options.

A culture and heritage capital approach will allow decision makers to:

- monitor and evaluate losses and gains in culture and heritage over time

- assess the value of future services provided by an asset

- identify priority areas for investment and inform resourcing and management decisions

- highlight links with economic activity and pressures on culture and heritage assets

- provide a common framework to bring together scientific, economic, and social evidence and analysis for a particular subject or place

- significantly reduce the risk of the value of culture and heritage (whether monetised or not) being ignored in decision-making

- enable a more comprehensive cost-benefit analysis and risk assessment

- facilitate a more innovative approach to identifying policy solutions

- understand the links between different types of capital.

While this programme will focus on creating guidance on valuation techniques for public funding, the methods will also be applicable to the private sector.

2.3 When should you measure culture and heritage capital?

Measuring the services provided by culture and heritage capital enables social cost benefit analysis decisions to include a consistent measure of the value culture and heritage have on welfare. This can be useful to answer a number of questions including:

- should we create a new asset, for example the building of a theatre?

- should we change the way we maintain or conserve an asset?

- would an intervention (including regulation) affect the services provided by culture or heritage?

- how would a policy affect the provision of cultural and heritage services?

- what interventions or policies should we use to protect culture and heritage assets and their services?

- how should culture and heritage be regulated?

- which intervention is the priority?

- how do fiscal, monetary and financial policies affect the services from culture and heritage assets?

- should we introduce further laws about the use, acquisition and protection of culture and heritage?

The principles of the culture and heritage capital approach are not just for policymakers and the public sector. Many businesses need to make decisions about their own culture and heritage assets or perhaps make decisions that affect culture and heritage capital in the local area. These relationships can be complex and not always obvious. A culture and heritage capital approach can help to analyse what is at stake and translate this into relevant information for decision making.

It is important to note that users of a culture and heritage capital approach should consider if the valuation of benefits is proportional to the situation. In some cases it is more appropriate to use Social Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (SCEA), a variant of Social Cost Benefit Analysis, which compares the costs of alternative ways of producing the same or similar outputs. HM Treasury’s Green Book provides guidance to help make a decision on the most suitable method.

2.4 Following a natural capital approach

Similar to culture and heritage capital, the natural capital approach is a framework for understanding the benefits of nature, whether that is the benefit of trees absorbing pollution, water for drinking or green space for recreation. The framework sets out how these benefits link to the extent and condition of the ecosystem allowing decision makers to understand where value is being derived and how irrecoverable damage to our environment can be avoided.

Over the last 10 years the evidence base for quantifying natural capital has improved significantly. The publication of Supplementary Green Book Guidance and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs’ publication of ‘Enabling a Natural Capital Approach’ supports the incorporation of benefits from the environment into decision making. The creation of the natural capital accounts at Office for National Statistics shows the stock quantity and value of services from the natural environment across the UK.

The UK government has made natural capital central to their decision making, including their ambition to ‘set gold standards in protecting and growing natural capital. Leading the world in using this approach as a tool in decision-making’ which is a key aim of the government’s 25-year environment plan.

The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme aims to emulate natural capital to quantify the benefits of culture and heritage assets.

3. The scope of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme

DCMS are initially taking an assets-based approach, consistent with the approach taken by the Natural Capital Committee, whereby an asset is identified as having cultural or heritage value and the services from the asset are quantified following the framework. Some assets are fixed and long-lasting, like a historic house, while others are mobile, like a steam train. We also include performing arts―such as a theatre show―and digital collections.

DCMS will group culture and heritage assets into broad categories that have similar methodological challenges for the valuation of their services. This scope is not an exhaustive list of culture and heritage but rather a range of assets that are appropriate to be measured by economic methods and for which economic values will be useful for decision making. We understand the difficulty with compiling a list of culture and heritage assets and will continue to work with sector experts to improve the scope. Therefore, this scope is subject to change and may be updated in future iterations of this document.

Table 1: Culture and Heritage Assets

| Definition | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Built Historic Environment | A historic structure identified as having a degree of significance because of its heritage interest | Listed and unlisted historic buildings and structures[footnote 6] |

| Landscapes and Archaeology | Historic features in the natural environment | Archaeological sites, battlefields, canals, gardens,parks, ruins, shipwrecks |

| Collections and Movable Heritage | An object that can be moved into a collection or is mobile | Art, archives, libraries, museum collections, plaques, sculptures, transport such as aircraft and trains |

| Performance and Performance Venues | Artistic content for an audience | Theatre, cinema, concerts halls, dance, festivals, multi-purpose spaces, music venues and other performance venues |

| Digital Assets | A virtual collection for engagement | Digital archives, online collections. |

Some assets and services are particularly difficult to estimate in monetary terms and therefore have not been included in the initial scope of the programme despite creating value. Some of these include:

- Intangible assets. Intangible assets are nonphysical such as folklore, customs, beliefs and traditions. As set out above these types of assets will not be part of the initial scope of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme. However, physical assets will provide services that enable these traditions and knowledge to continue and therefore their value will be partially evident within the estimates provided by the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme.

- Intellectual property. Intellectual property alone will not be valued. However, the value of intellectual property will be intrinsic to many of the willingness to pay values for live performance.

- Soft power. Soft power is the service provided from an asset through increasing the appeal of the area. This will not be included within the initial scope due to the difficulty of producing robust estimates. However, DCMS are interested to hear from experts who are developing valuation in this area that will be consistent with the culture and heritage capital approach.

4. Outline of the Culture and Heritage Capital Framework

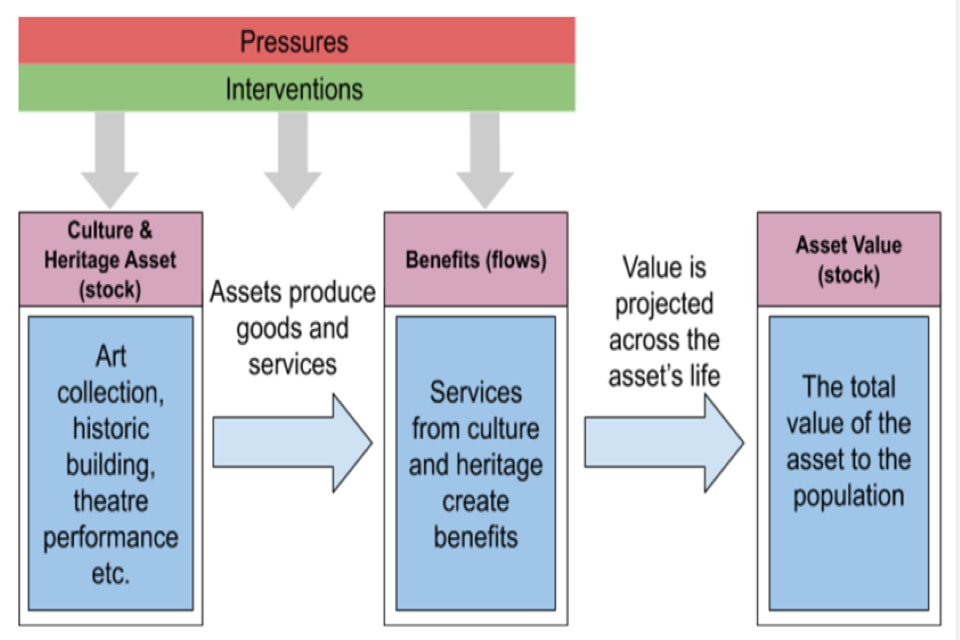

The Culture and Heritage Capital Framework is shown in Figure 1. It demonstrates how culture and heritage assets contribute to achieving the outcomes we seek as individuals and society more generally and how we aim to capture these benefits in a stocks and flows framework.

The assets, for example an art collection or historic building, are the “stock”, while the services that create benefits to society are regarded as “flows”. Background pressures such as environmental damage or unsustainable use can negatively affect the services provided by an asset and the demand for those services. Effective management interventions, additional inputs and effective policies can have a positive effect.

Once monetary values are estimated for these flows, it is possible to estimate the value of the asset as a whole by forecasting these values over a period of time. The sections below further explain how the stock and flows are measured.

Figure 1: The Culture and Heritage Capital Framework - Developed from D.Throsby and Natural Capital Logic Model (Natural England, 2018)

4.1 Culture and heritage asset (stock)

At its simplest, a culture and heritage capital approach is about thinking of an asset, or set of assets, that embody culture or heritage. The ability of a culture and heritage asset to provide goods and services is determined by its characteristics which could include condition, its history or its design for example. Defining these characteristics is more difficult for culture and heritage than for other forms of capital as the services are often derived from how a person interprets or feels about an asset. Further research is needed to understand the relationship between the characteristics of a culture and heritage asset and the services they provide. We anticipate that condition will be a key characteristic, particularly for heritage assets. Section 4.2 outlines how heritage science will be used to assess this condition.

4.2 Assessing condition with heritage science

Heritage science focuses on using scientific techniques to understand the care and sustainable usage of objects to allow them to enrich people’s lives, both today and in the future. Heritage science will play an important role within the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme to estimate the condition of physical assets, how this condition changes over time and how the condition affects the flow of benefits the assets produce. As outlined in Section 4.1, assets are subject to degradation, but an intervention may also cause or stop irreversible damage. The latter might rule out later investment opportunities or alternative uses of resources, so it is particularly important to make a full assessment of the costs of any irreversible damage that may arise or be mitigated from a proposal.

The HM Treasury Green Book states that irreversibility is often associated with facilities on which people place ‘option values’ (the value an individual receives from having the option to use the asset in the future) and ‘existence values’ (a type of non-use value). Given the uniqueness or rarity of many culture and heritage assets, the loss or degradation of an asset can be seen as an irreversible risk, because once the object is lost the value is irrecoverable or expensive to reverse.

The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will bring together the economic methodology and the work of heritage scientists, who are best placed to estimate the impact of conserving assets and therefore rates of degradation and irreversible loss.

4.3 Assets produce services (flows)

In Figure 1, we can see that culture and heritage assets create goods and services. If we follow the example of natural capital, an asset such as a woodland area provides goods and services such as timber, temperature regulation, recreation and pollution absorption. Similarly, culture and heritage assets provide servicesㅡfor example, a literature festival would provide recreation and educational services. Further work is needed to identify a more complete range of goods and services that are provided by culture and heritage assets.

4.4 Services create benefits (flows)

Goods and services produced by culture and heritage assets provide benefits to people, for example improving wellbeing, and create spillovers to the wider population such as a more productive workforce. It is changes in these benefits which are the focus of valuation in appraisal. SCBA requires that benefits are estimated in monetary terms, although much of the evidence to date has been qualitative or focused on outputs rather than than the valuation of outcomes and impacts. Furthermore, as the Rapid Evidence Assessment of culture and heritage valuation studies shows, previous studies have focused on the value to individuals. Therefore, research is needed to estimate the value of culture and heritage that is wider than individual preference.

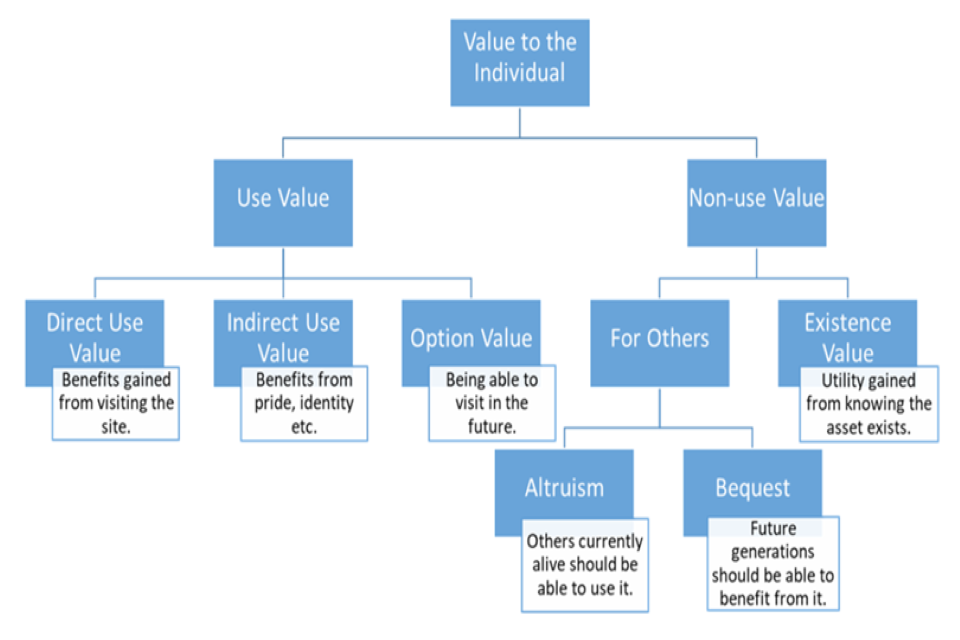

Individuals gain value from the benefits of culture and heritage in many different ways, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Types of values for culture and heritage assets to an individual

Individuals can gain value from visiting an asset such as a monument, from admiring it from afar, by reading about it on the internet or just by knowing they have the option to visit it. These values are known as use values.

People can also receive value from an asset despite not consuming it; this is known as non-use value. It includes the value people get from the existence of a cultural good (existence value), or from others being able to benefit from a good or service, in the present (altruistic value) or for future generations (bequest value). These types of values are particularly important within the culture and heritage sectors.

To estimate the value of a culture and heritage assets to an individual, we must look beyond market prices for three reasons. Firstly, admissions are often subsidised and not reflective of market powers: for example, many museums in England are free at the point of use. Secondly, heritage and culture are often consumable without entry: for example, admiring a historic house during your commute. Thirdly, people attribute value to culture and heritage without directly consuming it themselves (non-use value). We must therefore look at both market and non market values to capture the full range of benefits as shown in the middle section of Figure 1.

This understanding of value, as the reflection of individual preferences is at the root of the UK government’s conception of value for use in decision-making. To extract this willingness to pay, a range of methods will be needed; these will need to be innovative to capture the unique benefits of culture and heritage. DCMS has collated previous research that values the benefits of cultural and heritage capital and published the range of studies within the accompanying report ‘DCMS Rapid Evidence Assessment: Culture and Heritage Valuation Studies’, which includes the following methods:

- Contingent valuation. This method asks people to directly report their willingness to pay (WTP) to obtain a specified good, or willingness to accept (WTA) to give up a good.

- Choice modelling. Individuals are not directly asked for their willingness to pay, but rather their valuations are derived from their responses to a choice of options.

- Hedonic pricing. This is a revealed preference method that looks at the influence of a good/service on prices in a related market, for example, house prices.

- Travel cost. Here, willingness to pay is derived from the amount of time and money people are willing to spend travelling to consume a good or service.

- Subjective wellbeing. Value is inferred from the relationship between wellbeing and income.

- Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). QALYS are a common unit of output for health interventions.

This list of techniques is not exhaustive and further research is needed to understand the degree to which willingness to pay captured in these methods reflects the diverse range of benefits including improvements to health, social wellbeing and education.

4.5 Projecting future benefits across the asset’s life to estimate asset value (stock)

In order to make effective decisions about culture and heritage assets we need to work out how interventions will impact on the total value that the asset provides to the public over its lifetime. This will be affected by factors including:

- The asset life. Due to the diverse range of culture and heritage assets, the asset life will vary greatly. Museum collections hold artefacts that are thousands of years old that may exist well into the future. As part of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme, guidance will be created advising the time which the services from a culture or heritage asset should be accounted for. This is particularly important when thinking about an accounting value which will be used for the culture and heritage capital accounts.

- The length of the policy or intervention. When appraising a policy or investment the appraiser should choose an appropriate length of time to consider the benefits over. For example, an appropriate appraisal period for an investment in extra security for an asset would be the length of time the funding would be available for. Some policies or investments have benefits that last much longerㅡfor example, investment to improve access to theatre performances for school children is likely to reveal benefits in later life. In this case a proportional appraisal period will need to be decided. The HM Treasury Green Book contains further advice on appropriate appraisal periods.

- The usage of the asset. As with any asset, its usage will need to be modelled or at least assumed to continue into the future. This could include factors such as the abundance of similar local alternatives, population growth, or the condition of the asset.

- The quality of the services provided by the asset. Culture and heritage assets are often atypical. Most assets will gradually decline in quality and usefulness compared to newer alternatives; for example, a new train rolling stock will gradually fail as it gets older as well as become less efficient compared to more modern alternatives. However, as culture and heritage assets age they may become more valuable due to their increased age and rarity. The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will include research into the effect of time on the services culture and heritage assets provide.

- The discount rate. Time preference is a proven human trait that generally people prefer to receive goods and services now rather than later. To overcome this when modelling projections of benefits, discounting is used to compare costs and benefits occurring over different periods of time to convert costs and benefits into present values. Currently, Green Book Guidance suggests a Social Discount Rate of 3.5% for the first 30 years, 3% for years 31 to 75 and 2.5% from year 76 to year 125. The Office for National Statistics commissioned a review of discount rates for their natural capital accounts that supported the use of HM Treasury Green Book guidance up to a 100 year limit for renewable energy sources. DCMS will conduct similar research into the most appropriate rates and asset lives for culture and heritage assets, which may differ between types of assets. Discount rates may also vary between an appraisal approach for spending decisions and an accounting approach.

5. Key outputs of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme

Over the next few years the research we produce in Section 6 will underpin the key outputs of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme. The key outputs will include the following:

5.1 Supplementary guidance to the Green Book for culture and heritage capital

The Green Book is guidance issued by HM Treasury on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects. The role of appraisal and evaluation is to provide objective analysis to support decision making. Other capitals, such as natural capital, have a developed guidance; however, there is currently no HM Treasury Green Book guidance specific to culture and heritage capital.

The culture and heritage capital guidance will provide approved methods for use across government and the private sector, which will help officials develop transparent, objective, consistent and evidence-based advice for decision making.

While much of the published evidence will be academically rigorous, the Green Book supplementary guidance will provide practical guidance, that aims to be proportional to the scale of the decision needed and various culture and heritage asset types.

This guidance will also provide advice on how to assess distributional impacts which is necessary where an intervention either has a redistributive objective or where it is likely to have a significant impact on different groups, types of business, or geographic areas.

Although the work of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme is novel, the guidance will only include valuation techniques where the evidence is robust. This means the full range of assets in scope may not be included in the initial publication due to the length of time it takes to develop robust evidence.

5.2 A database of values for a range of culture and heritage assets

To be used alongside the supplementary Green Book guidance, DCMS will publish a web-based toolkit with a bank of values. The toolkit will only include values from studies DCMS deem of acceptable quality and follow a welfare approach in line with government appraisal guidelines. This will allow organisations to use valuations of similar assets to value their own assets through a process known as benefit transfer. Guidance will be developed to enable organisations to find the values that are most relevant to them. The publication of ‘DCMS Rapid Evidence Assessment: Culture and Heritage Valuation Studies’ available along side this document, as well as the reports from Arts Council England, Historic England and British Film Institute, will act as a basis of the evidence bank.

5.3 A set of national culture and heritage capital accounts

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) only tells us a part of the economic story as current methods only include transactions with market prices. The benefits to wellbeing, education and pride are, for example, missed from the measure and therefore it is an incomplete measure of public welfare. The System of National Accounts (SNA), which sets the international standards for measures of economic activity currently focuses on flows of income and output, not on stocks of capital.[footnote 7] This creates an incomplete measure of public welfare and value added. The Office for National Statistics have already developed a set of UK natural capital accounts that the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will look to emulate.

A set of accounts, conceptually consistent with the System of National Accounts, would facilitate comparison and potential integration with accounting data for the wider economy. To be consistent with the System of National Accounts and be extrapolated across the United Kingdom, the methods and the information used may be different to those in the Green Book supplementary guidance.

6. What’s next?

This document is the first step of the programme to formally introduce the government’s ambition for culture and heritage capital before focussing on enriching the evidence base. If you have suggestions for research topics that you think should be considered under the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme, please get in touch with us at chc@dcms.gov.uk.

DCMS and partners will collaborate to fill the gaps highlighted by the Rapid Evidence Assessment of culture and heritage values with a suite of published studies. These will be the basis for the Green Book guidance, the values database and the capital account outlined above. Some of the research we hope to complete is outlined below.

6.1 Expanding valuations across asset types

Currently, there is a limited amount of robust research focussed on a small collection of assets. Research to date has focused on cultural and heritage institutions where visitor numbers are readily available, such as museums and art galleries. The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme aims to gather enough evidence to value all assets in scope with reliable measurements.

While there has been increasing investment and demand for digital collections and content, there are very few valuation studies on digital assets. Given this, we see valuation of digital assets as an important area for further research.

6.2 Improving methodologies for valuation

The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will need to develop a range of ways to estimate the value of services provided by culture and heritage capital. Currently, the majority of studies use contingent valuation, but there is scope to build on the small number of hedonic valuations of culture and heritage assets. This would exploit enriched real estate data to value those types of culture and heritage assets that are amenable to hedonic pricing methods, notably heritage buildings and protected areas within urban zones. Alternatively, the travel cost method offers a practical approach to measuring willingness to pay using transport costs and associated spending. This approach was favoured for the Outdoor Recreation Valuation tool (ORVAL) created by the University of Exeter with support from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.[footnote 8] The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will develop methods for benefit transfer and decision modeling so organisations can accurately use the evidence bank where it is impractical or too expensive to undertake primary data collection. The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will also look to develop alternative ways to value the benefits of culture and heritage and would welcome your input. Please contact chc@dcms.gov.uk if you have suggestions for alternative methods.

6.3 Dealing with overlaps between natural capital and culture and heritage capital

There are many examples where natural capital and culture and heritage capital come into close proximity and are difficult to separate; parks with monuments, historic houses with gardens and canals with industrial heritage to name a few. It is important that the value from the culture or heritage asset and natural asset can be valued distinct from each other so that the natural capital and culture and heritage capital avoid double counting across the capital accounts. Case study examples will be used to attempt to disentangle the benefits of natural capital and culture and heritage capital.

6.4 Welfare weighting

As recommended by HM Treasury Green Book, welfare weighting permits using distributional weights to adjust for diminishing marginal utility of income. Without the use of welfare weighting there is potential that assets with higher income users may receive a higher estimated willingness to pay value. This could cause distorted decision making if it is not accounted for. The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will undertake further research to identify circumstances where welfare weighting is appropriate and how it should be implemented.

6.5 Discount rates and asset lives

Discount rates are used to account for time preference, a proven human trait that generally people prefer to receive goods and services now rather than later. To overcome this when modelling projections of benefits, discounting is used to compare costs and benefits occurring over different periods of time.

Currently, Green Book guidance suggests a Social Discount Rate of 3.5% for the first 30 years, 3% for years 31 to 75 and 2.5% from year 76 to year 125. The Office for National Statistics commissioned a review of discount rates for their Natural Capital Accounts that supported the use of Green Book guidance up to 100 years for renewable energy. DCMS will conduct similar research into the most appropriate rates and asset lives for culture and heritage assets, natural degradation rates for each asset and how this changes with different interventions and uses.

6.6 Application of non-use values

Non-use values are often overlooked in decision making, despite research showing they make up a substantial part of the value of culture and heritage assets. Non-use values include bequest, altruistic and existence values from those who do not directly benefit from the asset, and are a major part of the research of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme. To estimate an accurate non-use value for an asset, research is needed to ascertain how non-use values vary across the population and how these values should be used in practice. This will include the appraisal period over which they should be appraised.

6.7 Maintenance and heritage science

As outlined in Section 4.2, the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will bring economic methodology together with the work of heritage conservation scientists, who are best placed to estimate the impact of conserving assets, and from this, rates of depreciation and irreversible loss. Incorporating this into our guidance will allow organisations to fully assess the extent to which a proposal will mitigate (or cause) irreversible damage to a culture and heritage asset and the loss of flow benefits that would result. This research would have far-reaching effects not only on culture and heritage, but also on the appraisal of many other types of infrastructure.

6.8 Reusing historic assets to reduce environmental impacts

Upgrading and reusing existing buildings rather than demolishing and building new ones could dramatically decrease carbon emissions and wastage of materials. Even where materials are recycled, this is an extremely energy-intensive process. Historic England have published monetary estimates for the benefits of retrofitting historic buildings against demolishing them. Further research is needed to measure and quantify the full range of benefits that culture and heritage assets produce to prevent climate change and reduce environmental impacts.

7. Call for evidence

We would like to hear from experts across the sectors and academia who can support us with methodologies, research and data that could be used for the measurement of culture and heritage. Please contact chc@dcms.gov.uk.

Glossary

Altruistic value arises when the individual is concerned that the good in question should be available to others in the current generation. Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment (2006)

Benefit transfer is the exercise of taking estimated values from a sample of assets and applying them to another asset.

Bequest value is a feeling of satisfaction someone receives from the next and future generations having the option to make use of a good. Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment (2006)

Contingent valuation is a valuation technique whereby individuals are asked how much they would be willing to pay to obtain a good or service, or how much they would require to be compensated to give it up. The Green Book

Choice modelling involves presenting survey respondents with a range of alternatives from which respondents are asked to choose their most preferred alternative. New Zealand Institute of Economic Research

Culture and heritage capital (also referred to as cultural capital) is defined as “an asset which embodies, stores or gives rise to cultural value in addition to whatever economic value it may possess”. (Throsby, 1999)

Direct use value refers to the benefits provided by an asset that are used directly by individuals for example, from visiting a gallery. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

Discount rate is the annual percentage rate at which the present value of future monetary values are estimated to decrease over time. The discount rate used in the Green Book is known as the ‘social time preference rate’ (STPR). It is the rate at which society values the present compared to the future. The Green Book

Existence value is the value that individuals place on the knowledge that a resource continues to exist, whether or not they use that resource themselves. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

GDP (Gross Domestic Product) is the value of output or national income of a country over a 12-month period. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

Hedonic pricing is a form of revealed preference valuation that uses data from related surrogate markets and econometric techniques to estimate a value for a good or service. The Green Book

Indirect use value refers to the benefits derived from ecosystem services that are used indirectly by an economic agent. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

Intangible cultural heritage can be defined as “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity.” (definition used for the purpose of the UNESCO 2003 Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention) UNESCO

Human capital is a measure of the “knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being”. The Well-being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital

Market failure is where, for one reason or another, the market mechanism alone cannot achieve economic efficiency. The Green Book

Market value or price is the price at which a commodity can be bought or sold, determined through the interaction of buyers and sellers in a market. The Green Book

Natural capital is the stock of natural assets which provide benefits to people in the form of tangible things which are typically marketed (such as timber, fish stocks, minerals) and less tangible services (such as air purification, recreational settings and flood prevention). Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

Non-market value is the estimated value of goods and services that are not traded for money.

Non-use value refers to the benefit values (altruistic, bequest, and existence values) derived by individuals which are not associated with direct or indirect use of a resource. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

Option value refers to the value placed by individuals on having the option to use a resource in the future. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) is a measure of health status in terms of the quality of life associated with a state of health, and the number of years for which that health status is enjoyed. Department of Health and Social Care

Social capital is a term used to describe the extent and nature of our connections with others and the collective attitudes and behaviours between people that support a well-functioning, close-knit society. Office for National Statistics

Social Cost Benefit Analysis quantifies in monetary terms all effects on social welfare. Costs to society are given a negative value and benefits to society a positive value. Costs to the public sector are counted as a social welfare cost. The Green Book

Social Cost-Effectiveness Analysis compares the costs of alternative ways to produce the same or similar outputs. The Green Book

Soft power is the ability to attract and persuade through appeal or other influence, rather than through coercion.

Subjective wellbeing asks people directly how they think and feel about their own wellbeing, and includes aspects such as life satisfaction (evaluation), positive affect (hedonic), and a judgement on whether their life is meaningful (eudemonic). Department of Health and Social Care

Use value is the value derived from using or having the potential to use a resource. This is the net sum of direct use values, indirect use values and option values. Enabling a Natural Capital Approach: Guidance

-

Literature assessed on criteria; empirical design, method/dataset, and sample size. ↩

-

This problem was put forward by Mourato & Mazzanti (2002:68) ‘If the alternative to economic valuation is to put cultural heritage value equal or close to zero, the cultural sector would, as a result, be severely damaged. Ignoring economic preferences can lead to undervaluing and under pricing of cultural assets. This, directly and indirectly, reduces the amount of financial resources available to cultural institutions relative to other public priorities’ Mourato, Susana and Mazzanti, M. (2002) Economic valuation of cultural heritage: evidence and prospects. In: Torre, De la, Marta, (ed.) Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage. Getty Conservation Institute. ↩

-

Throsby, D. (1999), Cultural Capital.” Journal of Cultural Economics Vol. 23, No. 1/2, 1999, pp. 3–12. ↩

-

Intangible cultural heritage means the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity.’ (UNESCO) ↩

-

The Green Book is guidance issued by HM Treasury on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects. It also provides guidance on the design and use of monitoring and evaluation before, during and after implementation. ↩

-

Built Historic Environment includes agricultural buildings, commemorative structures, commerce and exchange buildings, culture and entertainment buildings, domestic buildings, educational buildings, health and welfare buildings, industrial buildings, law and government buildings, maritime and naval buildings, military structures, places of worship, sports and recreation buildings, street furniture, infrastructure. (Historic England) ↩

-

‘The System of National Accounts (SNA) is the internationally agreed standard set of recommendations on how to compile measures of economic activity. The SNA describes a coherent, consistent and integrated set of macroeconomic accounts in the context of a set of internationally agreed concepts, definitions, classifications and accounting rules.’ (United Nations Statistics Division) ↩

-

The Outdoor Recreation Valuation tool (ORVal) is a web application. It uses the annual Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment (MENE) survey data to estimate recreational demand for outdoor green space. The model can be used to derive the value households attach to the recreational opportunities provided by those sites in monetary terms. (University of Exeter) ↩