Testing for COVID-19 using saliva: case studies in vulnerable settings

Published 27 April 2023

Applies to England

Background

The coronavirus (COVID-19) national testing programme relied upon nose and throat swab-based sample collection methods for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and lateral flow testing. Guidance indicated that for tests requiring nose and throat swabbing where this proved challenging, nose-only swabs were an option. Despite this, self or assisted swabbing can prove difficult in certain settings.

Research has shown that saliva testing is also an effective sample collection method for detecting COVID-19 via different tests, such as PCR and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (1 to 8), and is generally easy to perform.

Three pilot studies

This report summarises the findings of 3 separate pilot studies, carried out prior to the widespread vaccine rollout in 2021, in which saliva samples were collected as an alternative to swab samples. The settings for the pilot, selected on the basis of their vulnerability to outbreaks and/or low testing uptake, were:

- needs and disabilities schools (known as special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) settings)

- a prison

- residential adult social care homes (known as RASC settings or care homes)

SEND and RASC settings were chosen as there were anecdotal reports of challenges using swabs for sample collection.

In SEND settings, problems can arise from the close interaction between subjects and testers where assisted testing is required, and students being unable to tolerate the penetration of swabs to obtain samples.

The majority of people living in care homes have multiple long-term health conditions, and are affected by physical disability and/or cognitive impairment (9). Additional issues can arise fitting testing around complicated treatment regimens and meal times.

Prisons were chosen as a use case as prisoners are recognised as vulnerable due to the closed nature of the setting, organisational complexity of swabbing, the limited mobility of prisoners, and the higher death rate from COVID-19 compared to people of the same age and sex in the general population (10). Implementing routine asymptomatic testing among the prison workforce was recognised to bring particular organisational challenges.

Details of the pilot studies

SEND settings

The Pathfinder Partnership between University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, the University of Southampton, and NHS Test and Trace conducted a pilot programme. It aimed to explore the utility of collecting saliva for Direct LAMP testing in SEND settings across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight.

The pilot ran for 13 weeks from 26 April to 23 July 2021.

Prison setting

The Pathfinder Partnership described above commenced a similar pilot programme of saliva-based testing at an adult male category B prison. The testing guidance for prison staff at that point was twice weekly lateral flow device (LFD) testing coupled with a once weekly PCR test. The pilot aimed to investigate whether saliva sampling could increase compliance with asymptomatic testing in the prison for both staff and prisoners and whether it was a safe and suitable technology for His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) needs.

The pilot commenced 26 July 2021 and ran until 28 September 2021.

RASC settings

A pilot within care home settings was primarily undertaken to support an application to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) by demonstrating the suitability of the collection kit. The data collected, alongside user research interviews conducted with participating care homes, also provided insights as to the feasibility of saliva as a sample collection method.

The pilot was conducted between December 2020 and February 2021.

Testing technologies

Different testing technologies can support saliva as the sampling medium. Saliva collection in SEND and prison settings was intended for Direct LAMP testing (7) whereas samples collected from care homes were intended for RT-PCR (11).

Direct LAMP is a rapid testing method as no ribonucleic acid (RNA) isolation step is required but the test is less sensitive than RNA isolation based technologies (7). However, the focus of this work is not the effectiveness of the testing technology, which is addressed elsewhere (1 to 8), but whether saliva collection as a sampling technique is a viable approach within a national public health testing programme.

Objectives

The objective of running the pilots was to gain as much insight as possible from quantitative and qualitative data as to the utility of saliva sampling for COVID-19 testing. It should be noted that these pilot use cases were not controlled studies.

This report addresses the following questions:

- Did the introduction of saliva sampling improve user experience of COVID-19 testing among participants?

- Did the introduction of saliva sampling increase uptake of COVID-19 testing among participants?

Methodologies

SEND settings pilot methodology

The pilot examined the acceptability of the saliva test with staff and students and how they felt about the overall experience, as well as investigating the reasons for non-participation. SEND students were in both mainstream education and specialist settings, as were the staff who may or may not have worked directly with SEND students in mainstream settings.

The pilot included a review of the participation data, a participant survey, a non-participation survey (sent only to staff and students in specialist SEND settings) and semi-structured interviews with parents or guardians of participants as well as with school headteachers or the main liaison staff within specialist SEND settings. (A non-participation survey is where people who do not take part in an intervention or pilot are approached for insights as to why they did not participate.)

Although SEND staff and students were provided with guidance to undertake one test per week, schools took part in the pilot for different lengths of time whereupon participation was measured according to 2 criteria:

- students or staff who provided at least one sample at some stage during the pilot

- participation in at least 50% of the possible weeks was considered a proxy for regular participation

Staff performed their own saliva sampling; students were assisted by their parents or guardians. Samples were then brought to school for collection.

It should be noted that this pilot commenced in April 2021. The majority of SEND schools remained physically open throughout the lockdown period with an expectation on parents to support their children to regularly test with lateral flow devices (LFDs). Similarly, children with SEND in mainstream schools were, in general, able to attend school in person throughout the lockdown.

Prison setting pilot methodology

The pilot covered prison staff and prisoners at an adult male category B prison, with separate user experience evaluations developed for each of these groups. The survey was designed in collaboration with HMPPS operational leads and approved by the Pilot Operational Group. In addition, researchers designed a semi-structured interview in anticipation of interviewing prison staff. Staff were asked to provide samples for testing by Direct LAMP twice weekly.

Due to an outbreak of COVID-19, saliva testing among prisoners was paused for operational reasons and this report therefore only reflects staff testing.

RASC settings pilot methodology

Having received a briefing on the study and the saliva kit, care home staff observed and reported on the experience of individual residents providing a saliva sample for testing. Different aspects of this were rated and collated by the project team for analysis.

In-depth interviews were conducted with each care home to collect qualitative feedback of user experience with the kits and saliva testing as a whole.

SEND settings: summary of findings

Student and staff participation

The pilot included 2,982 participants from SEND settings. Staff took a total of 5,537 samples and students took 2,634 within the pilot period.

Figure 1 is a bar chart that shows participation levels of the SEND settings pilot. Participation by SEND students, defined as providing at least one sample during the pilot, was 42%. Short and long term absence from school accounted for 5% of eligible students, meaning that 53% of students did not participate for some other reason. 74.2% of staff provided at least one sample during the pilot and 22% of students and 65.8% of staff participated regularly.

Direct comparator data on LFD testing rates is not available, however all individuals would have been expected to move from LFD to saliva testing for the pilot.

Figure 1. Student and staff participation during the SEND settings pilot period by participation measure

Participant survey

The opportunity to feedback via a survey on saliva sample collection was made available to all students and staff who took part in testing. Most questions were not mandatory, therefore, not all respondents appear in the breakdown of each question. The results of 2 questions reported here are on:

- ease of following instructions

- ease of collection of saliva samples

These responses were on a Likert-type scale of:

- extremely easy

- somewhat easy

- neither easy or difficult

- somewhat difficult

- extremely difficult

Preference of sample collection method (swab or saliva) was also asked.

There were 42 responses received from or on behalf of SEND students:

- 35 responses were from students themselves

- 7 responses were completed on their behalves

Around half of respondents were students who cited Autistic Spectrum Disorder as one of their needs.

There were 173 responses to the survey from staff. The total numbers of staff and students invited to participate is not known. It should be noted that this is a non-random convenience sample of students and staff who voluntarily took part in the survey and the findings are not necessarily generalisable to the overall SEND population.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 parents or guardians of students as well as 4 head teachers or the main liaison staff from SEND schools to explore the participants’ experience of testing. The interviews were, in part, informed by any trends emerging from the participant survey. The interviews explored important behavioural questions, such as whether the introduction of saliva-based Direct LAMP was likely to effect a change in how participants feel about asymptomatic testing, and whether it was likely to increase uptake.

It should be noted that this is a non-random convenience sample of parents, guardians and head teachers who voluntarily took part in the interviews and the findings are not necessarily generalisable to the overall SEND population.

Results from the SEND settings pilot

Swab versus saliva-based testing

Nearly all parents who participated expressed a preference for saliva testing for Direct-LAMP over swab-based testing for LFDs in the semi-structured interviews. Saliva collection was considered less invasive than swabbing and twice weekly testing with LFDs was considered additional work when compared to only having to test once a week with saliva-based Direct LAMP.

Parents and staff preferred not having to report the results of a LAMP test on GOV.UK, which they had to do with LFD tests, and LAMP testing was perceived by some to be more accurate than LFDs.

Below are some quotes from parents:

LFDs, PCRs, they’re quite invasive for anyone, let alone anyone that has got sensory issues.

Easier than LFD …doesn’t like swab in throat and refuses to be swabbed in nose.

Due to having a child with additional needs any form of touching cause him great distress. Being about to spit into a test tube with minimal pressure is a massive relief. This clear and precise approach gives children a clear understanding.

For a small number of the parents interviewed (3 out of 17), saliva testing enabled them to test their child which they otherwise could or would not have done. However, for most parents (14 out of 17), the introduction of saliva testing would not influence whether they tested their child or not. They may have preferred saliva testing but it was not a deciding factor and they would continue with LFDs if required.

Of 35 student responses to the survey:

- 27 students preferred the saliva sample collection method

- 5 students preferred the swabs

- 3 students were unsure

Among the 27 students who preferred saliva testing, there were 5 who had never previously swabbed.

Saliva collection

Survey responses showed almost all staff and approximately three-quarters of the students found it either extremely or somewhat easy to follow the instructions for collecting a saliva sample.

Considering saliva collection is less invasive than swabbing, the expectation was that both categories of participants would report finding this sample collection method easy. However, around half of students who responded found collecting the sample somewhat or extremely difficult and, while two-thirds of staff who responded classified saliva collection as extremely or somewhat easy, almost a quarter found it to be somewhat or extremely difficult (see bar chart in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ease of collecting saliva samples by students and staff during the SEND settings pilot

Interviewees reported multiple reasons why it was hard to give or collect a saliva sample. These included not being able to physically spit, not producing enough saliva, and difficulty in explaining the process to students with different cognitive abilities.

Other issues reported in interviews with the saliva collection method included a child who, having learned how to spit, then continued spitting around the house, and another child who found the process “disgusting” so the parents had to find a way to stop the child seeing the collected sample.

Participants were advised to collect the saliva sample the morning that they were due to drop the sample off at school. Similar to swabbing, there were time constraints around the timing of collecting saliva where no food or drink could be consumed one hour before collecting the sample. In interviews with school staff, one mentioned that uptake may have been higher if families could have been flexible with the time of testing as mornings could be hectic, or the child’s mouth could be dry, or the child needed food and drink first thing in the morning.

Non-participation

A non-participation survey was conducted to gather some basic information about the primary and secondary needs of students who did not participate in the pilot, and allowed free text responses. In total, 88 partial responses were received and 53 parents or guardians responded on the specific issue of non-participation. In addition, interviews with the 4 headteachers or the main liaison staff specifically explored the feedback they had received from parents and students on non-participation.

As with the participation survey, just over a half of responses to the non-participation survey related to students with an Autistic Spectrum Disorder.

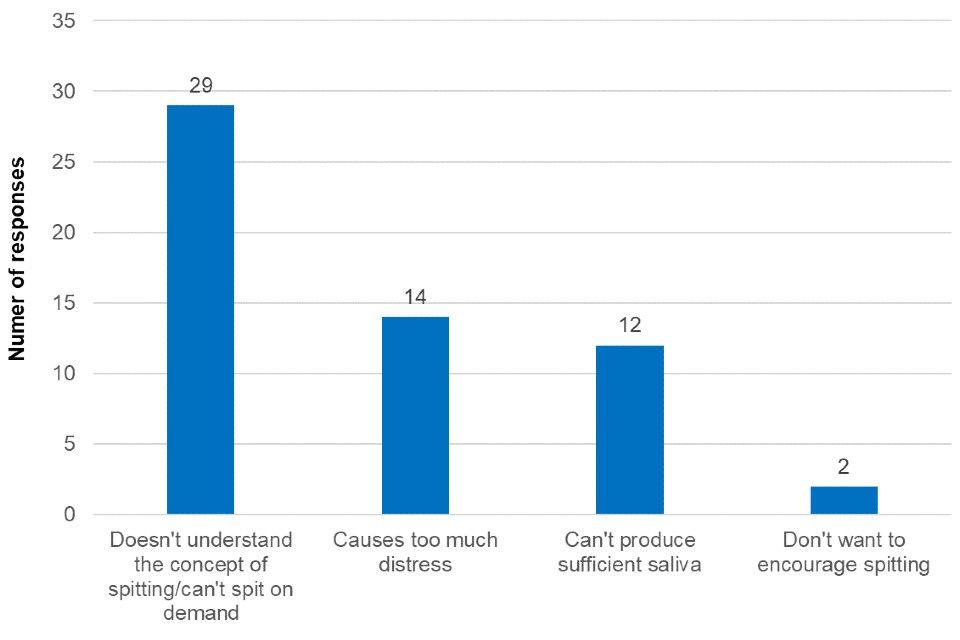

Free text responses outlining respondents reasoning behind non-participation were converted into 4 categories, as shown in Figure 3, and include:

- doesn’t understand the concept of spitting, or can’t spit on demand

- causes too much distress

- can’t produce sufficient saliva

- don’t want to encourage spitting

Some respondents mentioned more than one factor that contributed to their decision; this is reflected below.

Figure 3. Reasons given for non-participation (categorised from free text responses) during the SEND settings pilot

Figure 3 is a bar chart that shows the reasons given for non-participation during the SEND settings pilot. While insufficient saliva production and the fear of encouraging spitting were cited as reasons for non-participation for SEND students, the responses were heavily weighted towards the difficulties explaining to students the concept of the test or requiring them to spit on demand (29 responses). Furthermore, 14 responses in the survey free text cited causing distress as a reason for not being able to participate. Comments included:

He has severe learning difficulties and is nonverbal. He has very limited understanding. Therefore, asking him to spit into a cup or anything similar to that is simply not possible as he doesn’t understand what you are asking, and equally he will not copy if you showed him how.

My child has severe learning disabilities… she doesn’t know how to spit, and I don’t want to teach her how to spit for her to spit everywhere… she won’t understand that she can only spit once a week and only into a spoon.

Interviews with SEND headteachers and school staff supported these observations. They noted the reasons given for students not taking part in testing were mixed between not being able to complete a test and choosing not to take part for other reasons.

One of the interviewees estimated that of those not participating in saliva-based testing in their school, a quarter were unable to participate for reasons such as not being able to spit or produce saliva, whilst the rest were not engaging with any form of testing.

While it is difficult to quantify the impact, school staff indicated in the interviews that there was apathy towards, or disengagement with, asymptomatic testing in general. There appeared to be greater interest to take part in testing in 2 of the schools surveyed, but the needs of the students made it a challenge even with saliva sample collection as an option.

Conclusions from the SEND settings pilot

COVID-19 testing participation rates in SEND settings are very low. It was hoped that saliva sampling would be an easier way of testing SEND students and as such increase participation rates.

Overall, saliva collection appeared to have been preferred by parents and students though it was not considered easy to perform. There is evidence to suggest that saliva sampling could enable some students to test who otherwise might not have been able to, but that there was not a widespread positive impact from introducing this alternative testing approach such that testing rates increased. It appeared that many, possibly most, students did not test with either saliva or swab, and that the reasons for this were not related to the sampling method.

Of those who took part in the saliva sampling pilot, or who considered it but then declined, there were a number of issues and concerns around the production and collection of the sample. In some cases these were strong enough to halt or prevent participation.

However, for those who said they preferred saliva-based testing, the reasons were not about the sample collection method itself but other aspects of the testing process such as only having to test once a week instead of twice and not having to report the test result oneself. This suggests there are other aspects of testing that could be addressed which may increase testing uptake more effectively than the sample collection method.

Many students were not able to provide saliva samples and, as such, if saliva sampling were to be offered as a sample collection method in SEND settings, it should be offered alongside other testing methods.

Prison setting: summary of findings

In the summer of 2021, the testing guidance for prison staff was twice-weekly rapid antigen testing using LFDs coupled with a once-weekly PCR test. In the pilot, staff tested twice-weekly with saliva-based Direct LAMP.

Reliable data on staff LFD testing rates prior to the pilot was not available and adherence to such guidance could not be determined. However, PCR rates were reliably reported due to the registration and tracking conducted as part of the service and could possibly serve as an indicator of the maximum possible level of adherence in any given prison.

Average weekly PCR staff testing uptake in prisons in June 2021 as measured by the Ministry of Justice was observed to vary widely from around 2% to 93%. Testing uptake in the pilot prison was towards the lower end of the range at 7.7%.

The saliva-based Direct LAMP testing pilot aimed to cover prison staff and prisoners. However, a COVID-19 outbreak at the prison led to operational challenges that resulted in the cancellation of the prisoner saliva testing pilot.

Similar to the pilot conducted in SEND schools, user experience evaluations were conducted to examine the acceptability and usability of the test, and how those who participated felt about the overall experience of the pilot.

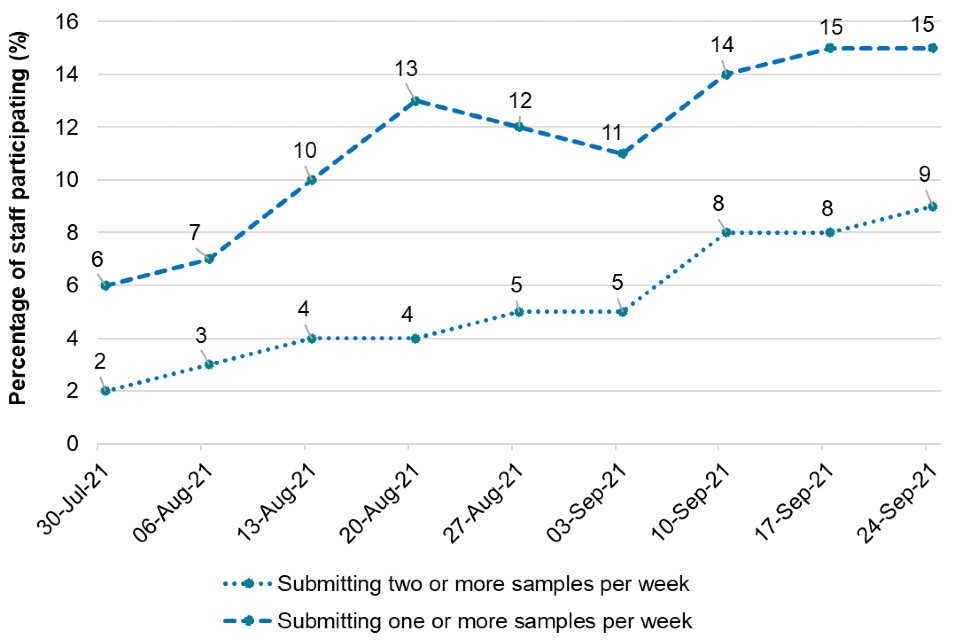

Figure 4 is a line graph that shows the uptake in saliva sample testing among prison staff during the pilot (30 July 2021 to 24 September 2021).

Figure 4. Percentage of staff participation and compliance with saliva-based Direct LAMP testing guidelines during the SEND settings pilot

Figure 4 shows that the overall level of staff participation (in line with the guidance to test with Direct LAMP twice weekly) was low throughout the pilot, reaching a sustained level of around 9% in the latter weeks of the evaluation period. A further 6% of the staff population appeared to be testing once a week towards the end of the evaluation period, so while they were not following the guidance for twice weekly participation, a total of 15% of staff could be considered participant or partially participant by performing at least one test per week by the end of the pilot.

Comparable questions were used in a survey open to participants as those used within the SEND settings (see participant survey above). Of those participants in the pilot whom had completed the survey (37 respondents):

- all (37 out of 37) were able to complete the test

- nearly all (35 out of 37) found it easy to collect the saliva sample

- nearly all (35 out of 37) indicated a preference for this sample collection method

If offered a choice, 36 out of 37 respondents whom had completed the survey would test with saliva instead of swab.

However, the survey also suggested that saliva sampling does not ‘unlock’ testing for staff members, as 33 of 37 respondents reported that they had been testing with LFDs or PCRs routinely prior to the pilot.

The 9% of eligible staff latterly following twice weekly saliva-based Direct LAMP guidance can only be considered a marginal improvement, if at all, over the average PCR testing rate of 7.7% in June 2021 for the same prison.

Conclusion from the prison setting pilot

Prison staff who actively participated in the testing pilot preferred saliva sampling to the standard swab sampling method. However, the switch to using saliva did not result in increased testing uptake towards levels that can be achieved through more standard swabbing in higher performing prisons. This suggests the purported ease of saliva sampling does not mitigate factors causing low uptake.

RASC settings: summary of findings

A total of 110 residents from 11 care homes in England and Wales took part in the pilot. The results of staff observations were very mixed with regards to how easy or difficult it was to collect the saliva sample.

Figure 5 is a bar chart that shows for 40% of residents, it was somewhat or very difficult to obtain the saliva sample and for 44% it was somewhat or very easy. This means that of residents for whom there was a response, more than a half did not report collection of saliva samples as easy. This suggests a saliva-based approach is unlikely to be a simple solution to improving uptake and reducing distress associated with test sample collection.

Figure 5. Answers to the question ‘Overall, how easy was it to collect the saliva samples?’ from the RASC settings pilot

There was a notable variation in the level of difficulty in collecting samples by resident type. Residents with dementia in particular tended to struggle with sample provision.

The ability of care home residents to produce sufficient saliva for testing was also investigated. Participating care homes generally reported the saliva guidance and kits easy to use and fit for purpose.

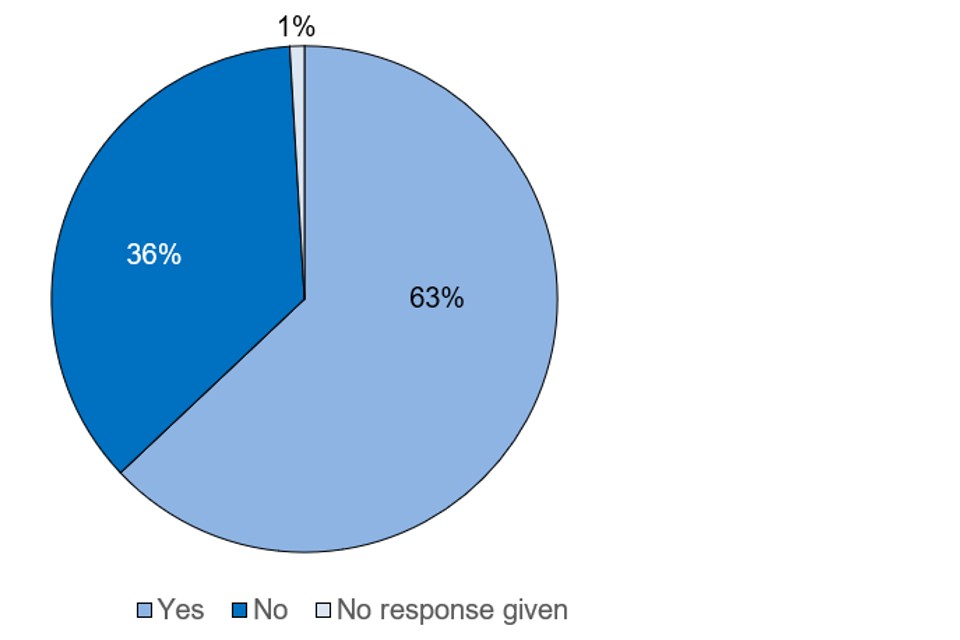

Figure 6 is a pie chart that summarises results regarding sample collections. Considering 36% of care home residents were not able to provide the 1ml sample required for the test, the testing methods employed here would likely limit how widely saliva-based tests of this nature could be deployed in care homes.

Figure 6. Answers to the question ‘Was the resident able to produce enough saliva for the sample?’ from the RASC settings pilot

Care homes were asked to provide consolidated group feedback at the end of the pilot. Although there was an initial expectation that saliva kits would be easier and a less invasive method compared to swab testing for residents, in reality, the majority were surprised at the level of difficulty residents faced. There were challenges with understanding how to spit, conducting the act of spitting, and producing enough saliva for a sufficient sample.

Below are some quotes from care home staff:

I was really surprised, I thought it would go well but they couldn’t… I think we all take spitting for granted maybe, they weren’t able to spit.

It’s a shame because I did want it to work, it’s less invasive and my staff would love it, but it just didn’t work for the residents.

The saliva test was harder for me to do, a lot of energy was required to humour patients, mentally more exhausting than doing the swab. However, I would imagine the saliva test would be better for residents.

We have medications that need to be taken after food, so it could have impact on medication times… We’re only going to have a little window where you can get people tested, so the testing process would be stretched out.

Conclusion from the RASC settings pilot

Given that more than one third of residents were unable to produce enough saliva for a sample to be collected, there is little evidence to support wider rollout of this sample collection method for COVID-19 testing of care home residents.

Overall conclusions

The pilots presented here adopted an agile ‘fast fail’ approach to rapidly inform decision-making on implementation of saliva-based sample collection within the national testing programme. Any such implementation would have required a level of national infrastructure comparable to PCR-based testing.

The findings from this user acceptance pilot in 3 different settings are insufficient to make a recommendation for widespread adoption of saliva-based testing. They suggest that whilst saliva testing was, for some, preferable to swab testing, it did not increase testing uptake. Feedback from the pilot participants suggest the majority of those who took part in the pilot and tested with saliva would have anyway tested with swabs instead.

User experience results were mixed. Many were positive, and saliva testing did enable a small number of SEND school pupils who could not use swabs to take part in testing. However, there were high numbers of participants in both RASC and SEND settings who expressed difficulties with performing the test, generally because they were not able to provide enough saliva for the test. This suggests that saliva is not a panacea for the issues that have arisen in these settings with swab testing and that if saliva testing were to be introduced, it would need to be as a supplementary method of testing alongside swab testing which remains an appropriate testing method for many in these vulnerable settings.

Research on other saliva-based LAMP testing pilots has shown that communication, trust and convenience are all required for individuals to take part in the testing programme (12) though this research did not include testing of individuals in vulnerable settings.

To enable implementation and the development of appropriate infrastructure to support saliva testing it would need to be an effective approach within a setting that can be dedicated to that approach. The benefits demonstrated for these use cases are not at this stage sufficient to justify a separate infrastructure. Usability in terms of being a viable widespread alternative to swab testing remains therefore inconclusive and cannot be considered a driver for more rapid introduction at the present time.

References

1. Khiabani K. and Amirzade-Iranaq M.H. ‘Are saliva and deep throat sputum as reliable as common respiratory specimens for SARS-CoV-2 detection? A systematic review and meta-analysis’ American Journal of Infection Control 2021: volume 49, issue 9, pages 1,165 to 1176

2. Ibrahimi N, Delaunay-Moisan A, Hill C, Le Teuff G, Rupprecht JF, Thuret, JY and others. ‘Screening for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR: Saliva or nasopharyngeal swab? Rapid review and meta-analysis’ PLOS ONE 2021: volume 16, issue 6, e0253007

3. Basto ML, Perlman-Arrow S, Menzies D, and Campbell J.R. ‘The sensitivity and costs of testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection with saliva versus nasopharyngeal swabs: a systematic review and meta-analysis’ Annals of Internal Medicine 2021: volume 174, issue 4, pages 501 to 510

4. Butler-Laporte G, Lawandi A, Schiller I, Yao M.C, Dendukuri N, McDonald, E.G and Lee T.C. ‘Comparison of saliva and nasopharyngeal swab nucleic acid amplification testing for detection of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis’ JAMA Internal Medicine 2021: volume 181, issue 3, pages 353 to 360

5. Tsang N.N.Y, So H.C, Ng K.Y, Cowling B.J, Leung G.M. and Ip D.K.M. ‘Diagnostic performance of different sampling approaches for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis’ The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021: volume 21, issue 9, pages 1,233 to 1,245

6. Duncan DB, Mackett K, Ali MU, Yamamura D, Balion C. ‘Performance of saliva compared with nasopharyngeal swab for diagnosis of COVID-19 by NAAT in cross-sectional studies: Systematic review and meta-analysis’ Clinical Biochemistry 2022: S0009-9120(22)00193-X. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2022.08.004

7. Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) (2020). ‘Rapid evaluation of OptiGene RT-LAMP assay (direct and RNA formats)’

8. Kay O, Futschik ME, Turek E, Chapman D, Carr S and others. ‘Comparison of the performance of SARS-Cov-“ RNA qRT-PCR testing based on expectorated and drooled saliva samples’ Research Square 2023 (preprint)

9. British Geriatrics Society (2020). ‘COVID-19: managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes for older people’

10. Braithwaite I, Edge C, Lewer D and Hard J. ‘High COVID-19 death rates in prisons in England and Wales and the need for early vaccination’. Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2021: volume 9, issue 6, pages 569 to 570

11. Tan SH, Allicock O, Armstrong-Hough M and Wyllie, AL. ‘Saliva as a gold-standard sample for SARS-CoV-2 detection’. Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2021: volume 9, issue 6, pages 562 to 564

12. Watson D, Baralle N, Alagil J, Anil K, Ciccoganni S, Dewer-Haggart R, and others. ‘How do we engage people in testing for COVID-19? A rapid qualitative evaluation of a testing programme in schools, GP surgeries and a university’. BMC Public Health 2022: volume 22, issue 1, page 305

Acknowledgements

These pilots were devised and led through a collaboration of NHS Test and Trace (now part of UK Health Security Agency) and a number of organisations including:

- University of Southampton

- HMPPS

- University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust