Right to Rent scheme: Phase two evaluation

Published 9 February 2023

Right to Rent evaluation of landlords and letting agents, year ending March 21

Authors:

- Jacqui Banerjee, BVA BDRC

- Madeleine Green, BVA BDRC

- Kath Scanlon, The London School of Economics and Political Science

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who assisted in the design of questionnaire and the mystery shopper scenarios. A special thanks to all the mystery shoppers for conducting the encounters, during particularly challenging times. Thanks also to colleagues within Home Office Analysis and Insight for their assistance with this report, and the flexibility shown as we adapted the approach to the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, Dr Andrew Zurawan, Susannah Macpherson, Stuart Bell, Edward Henley and Zoe Pellatt.

Executive summary and implications for policy

Migrants and those born overseas account for a sizeable minority of private tenants in England: over one-quarter of households in the private rented sector in England are headed by someone born abroad[footnote 1]. The Right to Rent procedures and their consequences (whether intended or not) have the potential to affect many hundreds of thousands of tenant households, and similar numbers of landlords.

The Right to Rent scheme requires landlords of privately rented accommodation to conduct checks on all new tenants to establish if they have a legal right to be in the UK and therefore have the right to rent. The Government undertook a phased implementation of the Scheme, with phase one starting on 1 December 2014. The phase one location comprised the local authorities of Birmingham, Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton.

To inform further roll-out, an evaluation of the Scheme was commissioned, examining the first 6 months of implementation. It showed that there were no major differences in tenants’ access to accommodation between the phase one and the non-Right to Rent scheme comparator area. However, comments from a small number of landlords reported during the mystery shopping exercise and focus groups did indicate a potential for discrimination.

Thus, on widening rollout to the rest of England, the Home Office sought to continue examining whether the Right to Rent scheme had affected levels of racial discrimination in the housing market. This was assessed in 2 ways:

- through a mystery shopping exercise whereby mystery shoppers approached private landlords and letting agents to enquire about potential rental properties

- through primary quantitative and qualitative research with private landlords investigating awareness and engagement with the Right to Rent scheme

This work was undertaken by independent researchers at BVA BDRC with Professor Kath Scanlon of The London School of Economics and Political Science between September 2019 and October 2021.

In seeking to disentangle the general issue of race discrimination from the potential for race discrimination as a result of the Scheme, the evaluation uncovered no statistically significant findings of increased race discrimination as a result of the Scheme. Further, whilst some instances of discrimination on various dimensions including race (such as against people receiving Universal Credit or Housing Benefit) were identified through surveys and interviews with landlords, these were not, by way of detailed evidence, clearly attributable to the Scheme, as no landlord respondents were able to offer specific examples to provide sufficient evidence of a systematic bias introduced by the Scheme itself.

Mystery shopping research with letting agents and private landlords

-

There was no statistically significant evidence from the mystery shopping of systematic, unlawful race discrimination as a result of the Right to Rent scheme.

The central research question was whether Right to Rent leads to increased unlawful race discrimination. The results were that, whilst some clear examples of racially discriminatory attitudes were found, there was insufficient evidence to say that there was systematic race discrimination as a result of Right to Rent itself.

-

There were no statistically significant differences in mystery shopper ‘success’ outcomes by nationality and ethnicity.

The key measure of ‘success’ for which most data were collected is whether the shopper was told that there were properties to rent available. Overall, differences between UK and non-UK nationals were not statistically significant. The same measure can be analysed by ethnicity, comparing the experience of White shoppers with Black and minority ethnic (BME) shoppers. Like nationality, differences in treatment by ethnicity were not statistically significant.

-

Statistically, BME shoppers were significantly less likely to be sent details of rental property, though the evidence does not suggest this is a specific result of the Scheme.

Another success indicator was the extent to which shoppers were sent details of rental properties to consider. Reviewing the indicator by ethnicity does yield a statistically significant difference, with BME shoppers being less likely to receive property details, and this may indicate discrimination, although there is no evidence this is a result of the Scheme.

-

Mystery shoppers perceived their treatment by agents and landlords to be fair.

The vast majority of shoppers perceived their treatment by letting agents and landlords to be favourable. Differences in treatment by nationality and ethnicity were not statistically significant.

-

Although the difference was not statistically significant, negative shopper treatment on the basis of ethnicity was more marked in England than Wales, the policy off comparator location.

The geographical policy on/policy off comparative analysis suggested that differences in treatment could be related to Right to Rent as differential treatment on the basis of ethnicity (though not nationality) was more marked in England than in Wales (see Table 1 in Section 2.1 and Table 3a in 2.2[footnote 2].

-

Non-UK nationals were more likely than UK nationals to be asked what their nationality was, and whether they had residency status or leave to remain in the UK.

The mystery shopping research was designed to enable comparison of ‘success’ rates for those holding different types of identifying documentation. Among those with Group 1 and 2 documents, non-UK nationals were more likely than UK nationals to be asked what their nationality was, and whether they had residency status or leave to remain in the UK[footnote 3]. Both nationality and residency status/leave to remain are relevant to establishing that a prospective tenant has the right to rent.

Primary research with private landlords

-

General awareness of Right to Rent among landlords was strong and increased over the duration of the research exercise. Far fewer understood the changes to conducting status checks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A quantitative survey completed with private landlords found that the vast majority of private landlords claimed prior awareness of the Right to Rent scheme in January 2021 (79%, 236 out of 300). (See section 1.3 for the research methodology). This awareness has seen a statistically significant increase since the start of 2020. However, only around a half (53%, 160 out of 300) of private landlords considered themselves informed (well or quite well informed) and less than one in 5 (16%, 49 out of 300) were aware of the changes to guidance on conducting checks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

The majority of landlords held a positive view of the Right to Rent scheme.

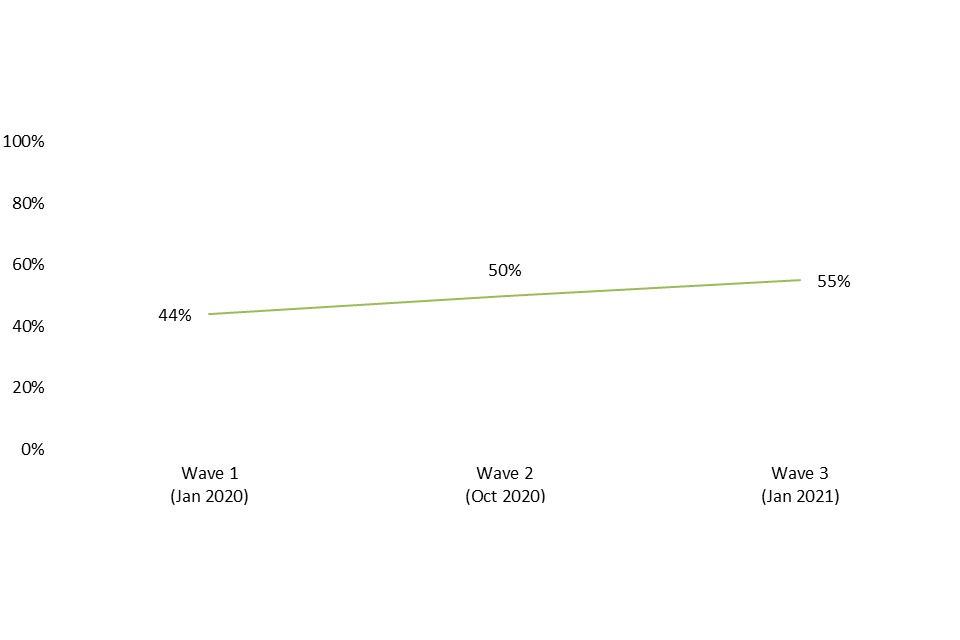

Just over a half (55%, 164 out of 300) of landlords held a positive view of the Right to Rent policy, a statistically significant year-on-year increase. Greater familiarity appears to drive a more positive impression of the scheme as those previously aware and/or claiming to be well informed hold a more positive view. These differences are statistically significant.

-

One in 5 landlords claimed awareness of discriminatory behaviour towards tenants. One in 10 attributed discriminatory behaviour to the Right to Rent scheme.

In January 2021, one-fifth (19%, 56 out of 300) of landlords reported awareness, most typically through informal ‘hearsay’ rather than direct experience, of tenants being discriminated against on the basis of their actual or perceived nationality, race or ethnic background, although specific examples were few and far between. Almost one in 10 (9%, 26 out of 300) surveyed landlords reported that such discrimination occurred as a direct impact of the Right to Rent scheme (lower than in January 2020). However, as with broad discrimination, when asked to give a specific example either no examples or vague examples were provided in the majority of those 26 cases. Landlords letting property in London (20%, 12 out of 60), members of landlord bodies or associations (19%, 20 out of 105), and those who consider themselves informed about the Right to Rent scheme (14%, 22 out of 160) were more likely to mention discrimination as a result of the scheme. These differences were statistically significant.

-

Over a half of landlords have engaged with online resources made available through GOV.UK

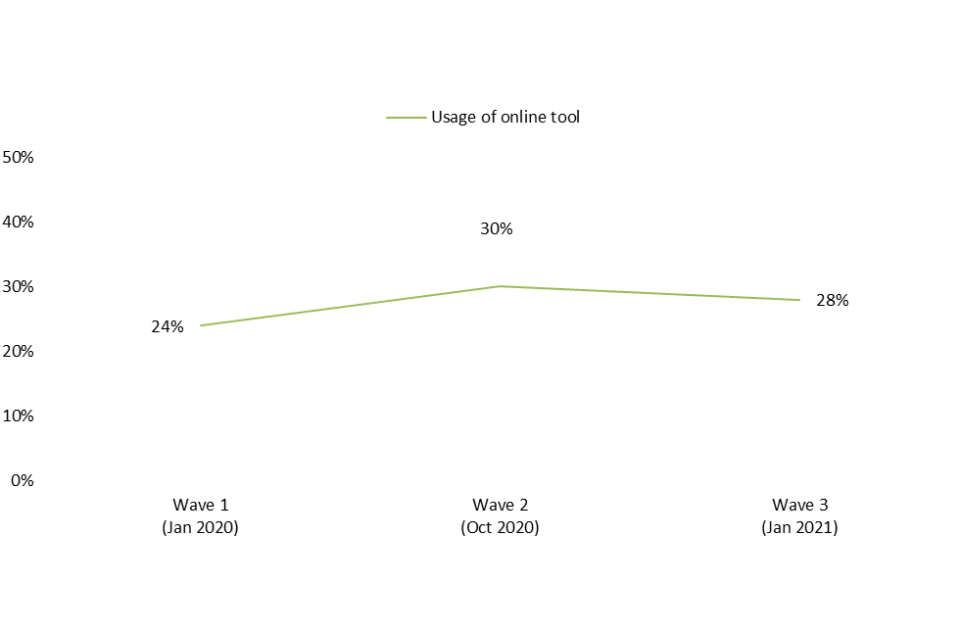

Just over a half (54%, 163 out of 300) of private landlord respondents had read one or more of the documents available on GOV.UK. and almost 3 in 10 (28%, 85 out of 300) had used the online tool: ‘Check if someone can rent your residential property’.

-

Self-managing landlords and those operating outside of a membership body appeared less informed about the Right to Rent scheme.

In qualitative research, self-managing landlords not using an agent for tenant sourcing/screening, those operating outside of a formal membership body, or those with smaller letting portfolios tended to have less of an understanding of the Right to Rent scheme’s details. For this segment, scheme awareness was often created through informal sources, such as word-of-mouth or media broadcasts, and knowledge of their responsibilities/liabilities was incomplete.

-

Two-thirds of landlords are confident to undertake tenant verification checks as defined by the Scheme, although confidence does vary linked to the nature of documents they are required to check.

Around 2 in 3 landlords (67%, 201 out of 300) stated that they feel very or quite confident carrying out the verification checks required by the Right to Rent scheme. This level of confidence saw a statistically significant increase among those who typically undertake such tenant checks themselves or who use a tenant referencing service. However, 1 in 5 landlords (19%, 17 out of 88) who do check tenant’s details themselves reported that they do not feel confident doing so. Confidence varied considerably depending on the documents available for checking: 83% (249 out of 300) reported feeling confident checking a UK passport, reducing to less than half of that figure (39%, 117 out of 300) when dealing with a European Economic Area (EEA) / Swiss national ID card[footnote 4].

Implications for policy

The central research question was whether the Right to Rent scheme leads to unlawful race discrimination. The results show that some clear examples of discriminatory attitudes were found, but there was insufficient evidence to claim any systematic unlawful discrimination as a result of the Scheme.

The only way to fully test the possible impact of the Scheme on race discrimination would have been to involve real mystery shopping tenants completing the shopper journey to the point of being offered (or not) a tenancy in England and compare that to an area where the Scheme was not in operation. Despite this, one would have expected a clearer and marked statistically significant difference between shopper experiences if systematic discrimination as a result of the Scheme were present. Thus, research exploring tenants’ experience of these final stages of the rental process would add to the evidence base but the ethical and logistical considerations of completing such research should be carefully considered by the Home Office. It should be noted by the reader that both COVID-19 restrictions and our strict adherence to the Market Research Society’s mystery shopping code of conduct (which prohibits unnecessary detriment to the subject’s business practice) precluded our ability to follow the tenant enquiry to its final conclusion. However, given the evidence presented in this report, it is our belief that even if we did pursue the shopper experience to the conclusion of the journey, the findings would not be significantly different.

Most of the interactions with landlords and letting agents reported by the mystery shoppers were helpful (67%, 1,326 out of 1,976) and friendly (65%, 1,285 out of 1,976), and Right to Rent requirements were dealt with in a matter-of-fact way, with some landlords not mentioning the checks at all at this stage of the rental process. The research did not find much evidence of pushback from landlords against the Scheme, perhaps because requesting documentation has always been an element of the rental transaction. Landlords routinely ask for confirmation of employment, bank details and references from previous landlords. Seen in this light, the additional paperwork involved in Right to Rent checks may not add materially to the volume of pre-tenancy work.

Fourteen per cent (42 out of 300) of landlords said that they would not rent to a UK national without a passport. The Right to Rent scheme could thus have the potential to disadvantage UK citizens without passports who are seeking to rent a home. However, putting this into context, landlords also reported not wishing to rent property to Housing Benefit or Local Housing Allowance (LHA) recipients at a much higher level (38%, 114 out of 300).

On the other hand, several shoppers were told that a driver’s licence would suffice as proof of having the right to rent despite this being insufficient as a standalone piece of evidence. Such confusion about the rules points to the importance of good quality information, delivered to as many private landlords and estate agents as possible. Although awareness of the Scheme is improving there are still obvious gaps in understanding, which could be addressed through an effective communication strategy.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Right to Rent scheme

The Right to Rent scheme was introduced as part of the Immigration Act 2014. As a result, landlords of private rental accommodation[footnote 5] in England are required to conduct checks to establish that new[footnote 6] tenants have the right to rent in the UK. Where a tenant has time-limited immigration status, landlords are also responsible for carrying out follow-up checks to confirm the individual continues to have a right to rent. Landlords who rent to migrants (without the right to rent) without having conducted these checks correctly will be liable to civil penalty action.

As a strand of the compliant environment, the Right to Rent scheme aims to:

- make it more difficult for illegally resident individuals to gain access to privately rented accommodation, and so deter those who are illegally resident from remaining in the UK

- deter those who seek to exploit illegal residents by providing illegal and unsafe accommodation, and increase actions against them

- deter individuals from attempting to enter the UK illegally

- undermine the market for those who seek to facilitate illegal migration or to traffic migrant workers

The Scheme’s implementation is being supported in a number of ways including:

- Codes of Practice on the right to rent and on avoiding unlawful discrimination

- a landlord’s guide to right to rent checks

- a user guide for tenants and landlords

- a helpline and online tool for verifying if a prospective tenant has a right to rent (note: the online tool does not verify an individual’s right to rent)

- the Landlord Checking Service (LCS)[footnote 7], which can confirm an individual’s right to rent, where an individual is unable to prove their right to rent by any other means

- a digital right to rent service which enables landlords to undertake right to rent checks in real time on those migrants eligible to use the service

- an option to sign up for updates on the Right to Rent scheme on GOV.UK[footnote 8]

The Scheme was implemented in Birmingham, Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton on 1 December 2014 and, following an initial evaluation[footnote 9], rolled out to the rest of England on 1 February 2016.

As part of the national measures introduced to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, from 30 March 2020 Right to Rent checks were temporarily adjusted to make it easier for landlords to carry out checks. These changes included a provision for remote assessments.

1.2 Purpose of the report

One concern raised before the introduction of the Right to Rent scheme in 2014 was that it might lead to direct or indirect discrimination by landlords and agents, primarily on the grounds of race. This concern was linked to the possibility that some landlords and agents might feel that it was more difficult or time-consuming to check the right to rent of non-UK nationals (or those they perceived as not being UK nationals) and therefore, might be less likely to offer tenancies to them[footnote 10].

This report therefore examines whether the Right to Rent scheme is resulting in increased levels of race discrimination in the private rental sector.

1.3 Research methodology

To test if the Right to Rent scheme is resulting in increased levels of unlawful racial discrimination in the private rental sector, 3 primary research exercises were undertaken:

- a mystery shopping exercise, based around typical rental searches

- a quantitative survey of private landlords

- qualitative research with private landlords

A similar research process was conducted on behalf of the Home Office by BVA BDRC to evaluate the Right to Rent pilot in 2016.

All elements of landlord research and overall reporting were carried out independently by BVA BDRC, an international consumer and business insight consultancy. ESA Retail (part of the BDRC Group) provided all aspects of operational mystery shopping. Further information on the research agency can be found in the appendix, section 4.1.3.

This report contains both the evidence gained through the mystery shopping exercise and the research with private landlords.

1.3.1 Mystery shopping method

The mystery shopping exercise consisted of a sample of 2,408 prospective tenants who approached landlords and agents and recorded their experience. 1,976 received a response and were included in the detailed analysis. The exercise was designed to investigate whether:

- there were systemic differences correlated with ethnicity, race, nationality or immigration status in the way that mystery shoppers were treated by landlords or letting agents

- this differential treatment appeared to constitute unlawful race discrimination

- any such unlawful discrimination was caused by Right to Rent legislation

Individual mystery shopping assessments were undertaken across England and Wales in February and March 2020 and between October 2020 and January 2021.

The mystery shopping data were analysed using a matched-pair method, which has been previously employed by academics and governments to identify discrimination, often in the field of employment but also in housing. The technique has been used to detect racial discrimination in housing contexts, including mortgage applications and searches for rental accommodation, across 4 large-scale US studies (see Appendix section 4.1.1 for further details).

1.3.2 Landlords primary research method

The quantitative surveys of private landlords and the in-depth qualitative interviews aimed to:

- track awareness and knowledge of the Right to Rent scheme

- establish whether discrimination is occurring, both in general and as a result of the Right to Rent scheme

The quantitative surveys were conducted online. Landlords were recruited to take part through a proprietary online consumer research panel (Dynata). For the qualitative interviews, landlords were free-found by specialist recruiters and one-to-one interviews were conducted through video calls. The results of the research are discussed in this report, with any mentions of discrimination discussed in detail. All references to discrimination were self-reported by landlords.

Sample sizes and fieldwork dates are as follows:

- Wave 1 (January 2020): 309 interviews (fieldwork in January 2020)

- Wave 2 (October 2020): 300 interviews (fieldwork in October 2020)

- Wave 3 (January 2021): 300 interviews (fieldwork in January 2021)

Planned fieldwork was paused from March to October 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and resumed in October 2020.

This report primarily focuses on the Wave 3 results, with references to trends and any relevant differences from Wave 1 and Wave 2.

A detailed description of all methodological approaches can be found in the Appendix, section 4.1.

1.4 Structure of the report

This report is structured to reflect the findings of the 2 primary research components which underpin this evaluation.

Section 2 examines the experience of mystery shoppers who approached private landlords and letting agents to enquire about potential rental properties. It is divided into 5 broad sections, each of which includes comparisons of those experiences across location, shopper group and enquiry scenario.

Section 2.1 examines enquiry outcomes based on shopper nationality.

Section 2.2 reports enquiry outcomes based on shopper ethnicity.

Section 2.3 summarises the shopper’s perceptions of favourable/unfavourable treatment linked to issues of nationality.

Section 2.4 assesses the extent to which mystery shoppers were asked to provide supporting documentation to substantiate their right to rent.

Section 2.5 looks at enquiry ‘success’ comparison using matched-pairs testing.

Each of the 4 scenarios had 2 groups of shoppers, who differed only in the aspect being tested (ethnicity, nationality or type of document held).

Section 3 is focused on primary quantitative research undertaken over 3 waves, between January 2020 and January 2021, and supplementary qualitative interviews with private landlords. This section assesses landlords’ awareness and engagement with the Right to Rent scheme and their perception of the extent to which it has driven discriminatory behaviour. Like the preceding section, there are 5 modules of content in this section.

Section 3.1 deals with the incidence of any form of discrimination in terms of various tenant segments in the general population, before focusing on issues of nationality, race or ethnic background.

Section 3.2 quantifies landlord awareness of the Right to Rent scheme.

Section 3.3 quantifies landlord engagement with the various Scheme resources made available through GOV.UK.

Section 3.4 provides an overview of landlords’ tenant checking/vetting processes and the extent to which their confidence in undertaking checks varies by the type of information presented by would be tenants.

Section 3.5 provides an overview of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their lettings business.

The report Appendix contains details of the research methodology, copies of the mystery shopping assessment/questionnaire template, the sampling frame, the mystery shopping scenarios enacted, and the landlord survey questionnaire/discussion guide.

2. Detailed findings: Mystery shopping research with letting agents and landlords

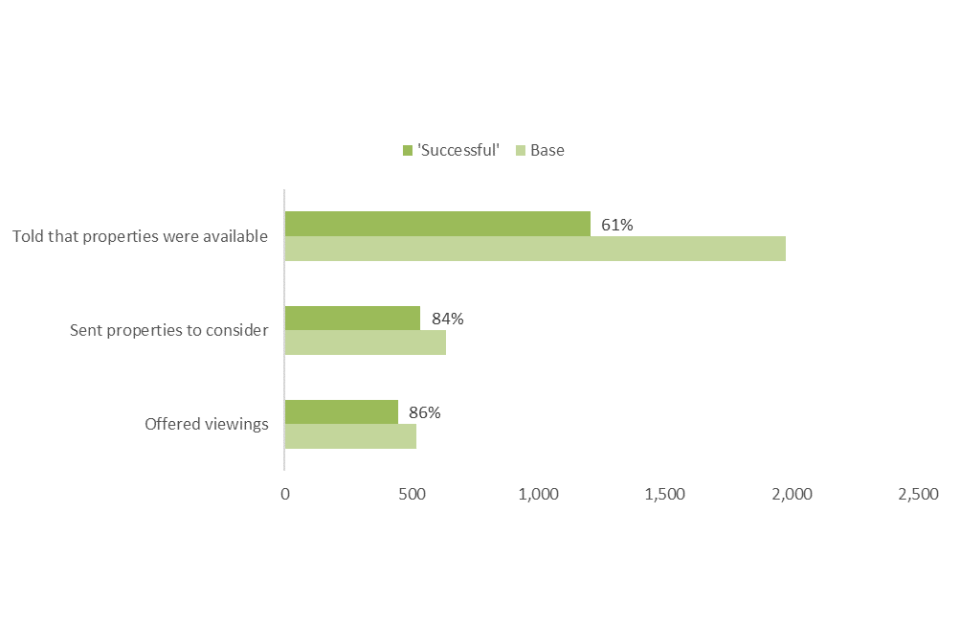

As a reminder, all enquiries with landlords and agents were conducted either by telephone or email with no face-to-face contact with mystery shoppers (due to social distancing regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic). Overall, some 61% of applicants (1,205 out of 1,976) were told by the letting agent or landlord during their first contact that rental properties were available (Figure 1). Not all mystery shoppers proceeded to subsequent contacts; of those who did, 84% (535 out of 638) were sent properties to consider, and 86% (446 out of 519) were offered a viewing.

Figure 1: Proportion of mystery shoppers successful in enquiries

2.1 ‘Success’ and nationality

The measure of ‘success’ for which most data were collected was whether the shopper was told that there were properties available to rent[footnote 11]. Table 1 presents the overall results by nationality. Overall, UK nationals were slightly less likely to be told that there were properties available (60% compared with 62% for non-UK nationals), but the -3% difference was not statistically significant[footnote 12].

Table 1: Whether properties are available, by shopper nationality (UK/non-UK)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 1,976). P = 0.25; not statistically significant.

| No | Yes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK nationalities | 40.2% (309) | 59.8% (459) | 768 |

| Other nationalities | 37.7% (455) | 62.3% (753) | 1,208 |

| Difference between UK/non-UK ‘success’ | -2.6% |

Mystery shoppers who spoke to agents were more likely to be told there were properties available compared to those contacting landlords, but there was little variation in the difference between UK and non-UK ‘success’.

There was a difference in the treatment of different nationalities in the ‘policy on’ and ‘policy off’ urban areas (Table 2). For this analysis, data were combined from all 4 scenarios.

The mystery shopping research tested 4 shopper scenarios, each with 2 sub-groups of equal size, to allow for paired testing of the effects of a single variable.

Scenario 1: Designed to test the effect of ethnicity while holding nationality and documentation constant.

Both mystery shoppers were British, with documents from List A Group 2:

- Scenario 1a shoppers were BME

- Scenario 1b shoppers were White

Scenarios 2 and 3: Designed to test the effect of different types of documentation while holding ethnicity and non-UK nationality constant.

Scenario 2 mystery shoppers were White, non-EEA Eastern Europeans:

- Scenario 2a had documents from List A Group 2

- Scenario 2b had documents from List A Group 1

Scenario 3:

Scenario 3 mystery shoppers were BME from Africa or South Asia:

- Scenario 3a had List A Group 2 documents

- Scenario 3b had documents from List A Group 1

Scenario 4: Designed to test the effect of nationality while holding ethnicity and documentation constant.

Scenario 4 mystery shoppers were BME and had List A Group 1 documents:

- Scenario 4a shoppers were UK nationals

- Scenario 4b shoppers were of African or South Asian nationality

The direction of the difference did not support the hypothesis that Right to Rent checks are causing greater discrimination on the basis of nationality in England than in Wales. The results indicated that in the English cities, UK nationals were 8% less likely than non-UK citizens to be told that there were properties available, while in Wales the difference was only 1%. Note, however, that the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2: Whether properties are available, by shopper nationality and policy on/policy off (England/Wales)

Base: All mystery shoppers in paired locations who received a response (n = 800). England: P = 0.12, Wales: P = 0.89; not statistically significant.

| England: policy on Bristol, Stoke | Wales: policy off Cardiff, Wrexham | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | No | Yes | Total | |

| UK nationalities | 47.4% (73) | 52.6% (81) | 154 | 41.0% (66) | 59.0% (95) | 161 |

| Other nationalities | 39.6% (97) | 60.4% (148) | 245 | 41.7% (100) | 58.3% (140) | 240 |

| Difference between UK/non-UK ‘success’ | -7.8% | 0.7% |

2.2 ‘Success’ and ethnicity

The same question can also be analysed by shopper ethnicity, comparing the treatment of White shoppers (both UK nationals and Eastern Europeans) and Black and minority ethnic (BME) shoppers, also including both UK and non-UK nationals, (Table 3a) across all scenario areas. The data indicate that BME shoppers were less likely than White shoppers to be told that there were properties available (60%, 736 out of 1,222, compared with 63%, 476 out of 754). Again, the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 3a: Whether properties are available, by shopper ethnicity (White/BME)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 1,976). P = 0.20; not statistically significant.

| No | Yes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 36.9% (278) | 63.1% (476) | 754 |

| BME | 39.8% (486) | 60.2% (736) | 1,222 |

| Difference between White/BME ‘success’ | 2.9% |

Although at an overall level there was not a significant difference in ‘success’ by ethnicity, breaking down the data by agent type reveals a statistically significant difference in treatment of White and BME shoppers among national and regional estate agents (Table 3b). The data indicate that national and regional estate agents were significantly more likely to tell White shoppers that there were properties available (73%, 139 out of 191) compared to BME shoppers (60%, 197 out of 329). Had there been a systematic discriminatory effect due to the Scheme, we would have expected a similar pattern with other agent types. This was not the case.

Table 3b: Proportion of shoppers told properties were available, by agent type and shopper ethnicity (White/BME)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 1,976).

| White | BME | Difference between White/BME | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National/regional agent | 72.8% (139) | 59.9% (197) | 12.9%1* |

| Independent agent | 58.1% (111) | 58.4% (177) | -0.3% |

| Online agent | 72.3% (73) | 66.5% (115) | 5.8% |

| Landlord | 56.5% (153) | 59.2% (247) | -2.8% |

Notes:

- “*” represents statistical significance at 99% confidence level (p<0.01).

The ethnicity results were also broken down by policy on/policy off areas (Table 4); whilst there are differences, these are not statistically significant. The results indicated that BME applicants in English cities were 1% more likely than White applicants to be told that there were no properties available, whereas in Wales BME applicants were less likely than White applicants to be told that no properties were available (38% of BME applicants were told that there were no properties compared with 41% of White applicants).

Table 4: Whether properties are available, by shopper ethnicity and policy on/policy off (England/Wales)

Base: All mystery shoppers in paired locations who received a response (n = 610). England P = 0.89; not statistically significant. Wales P = 0.60; not statistically significant. Difference between England and Wales P = 0.78; not statistically significant.

| England: policy on Bristol, Stoke | Wales: policy off Cardiff, Wrexham | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | No | Yes | Total | |

| White | 41.7% (63) | 58.3% (88) | 151 | 40.6% (63) | 59.4% (92) | 155 |

| BME | 42.5% (65) | 57.5% (88) | 153 | 37.7% (57) | 62.3% (94) | 151 |

| Difference between White/BME ‘success’ in each area | 0.8% | -2.9% | ||||

| Difference between White/BME ‘success’ in England and Wales | 3.7% |

The next measure of ‘success’ is whether shoppers were sent details of rental properties to consider. This question was answered only by those shoppers who received a follow-up from the letting agent or landlord within 2 working days – that is, the shoppers did not initiate follow-ups themselves. There were relatively few responses (638) compared to the question about property availability, which was answered by 1,976 shoppers.

UK nationals were statistically no more likely to receive properties to consider than non-UK nationals (85% compared with 84%), see Table 5a. However, as with the previous analysis, the difference was considerably larger when considering only the mystery shoppers who approached national and regional estate agents; within this group more UK nationals received properties to consider than non-UK nationals and this was a statistically significant difference.

Table 5a: Whether shopper was sent properties to consider, by shopper nationality (UK/non-UK)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a follow-up from a letting agent or landlord and were told they could help (n = 638). P = 0.58; not statistically significant.

| No | Yes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK nationalities | 14.6% (33) | 85.4% (193) | 226 |

| Other nationalities | 16.3% (67) | 83.7% (345) | 412 |

| Difference between UK/non-UK ‘yes’ | 1.7% |

Table 5b: Proportion of shoppers sent properties to consider, by agent type and shopper nationality (UK/non-UK)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a follow-up from a letting agent or landlord and were told they could help (n = 638).

| UK nationalities | Other nationalities | Difference between UK/non-UK | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National/regional agent | 98.4% (60) | 86.6% (110) | 11.7%* |

| Independent agent | 82.0% (41) | 76.5% (62) | 5.5% |

| Online agent | 88.2% (30) | 92.1% (35) | -3.9% |

| Landlord | 76.5% (62) | 83.1% (138) | -6.6% |

Notes:

- “*” represents statistical significance at 95% confidence level (p<0.05).

Examining the question by shopper ethnicity, the difference was larger: 88% of White shoppers were sent properties to consider compared with 82% of BME shoppers (Table 6). This is a statistically significant difference and may indicate discrimination on the basis of race, but not as a clear systematic result of the Scheme per se.

Table 6: Whether shopper was sent properties to consider, by shopper ethnicity

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a follow-up from agent or landlord and were told they could help (n = 638). P = 0.03; statistically significant at 95% confidence level.

| No | Yes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 11.9% (32) | 88.1% (236) | 268 |

| BME | 18.4% (68) | 81.6% (302) | 370 |

| Difference between White/BME ‘yes’ | 6.4% |

A total of 538 shoppers were sent properties to consider. Of these, 354 (68%) were sent details of a single property (sometimes the shopper specified that this was the property they had originally enquired about). Shoppers were sent an average of 3 properties to consider, but this included some shoppers who received links to a website with dozens or hundreds of properties available. Excluding those, the average number of properties received for consideration was 2[footnote 13].

2.3 Perceptions of favourable/unfavourable treatment by nationality

Mystery shoppers were asked to report their perceptions of how favourably or unfavourably they were treated by landlords and letting agents. Possible responses were collected through a 5-point Likert scale: very negative, negative, neutral, positive and very positive. The overwhelming majority of shoppers (over 90%) perceived their treatment to be favourable. UK nationals were statistically, no more likely to report positive treatment (Table 7). There were no statistically significant differences between agents and landlords or by type of agent.

Table 7: Perceived favourable/unfavourable treatment, by shopper nationality (UK/non-UK)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a response, excluding ‘neutral’ (n = 1,520). P = 0.85; not statistically significant.

| Negative/very negative | Positive/very positive | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK nationals | 9.3% (54) | 90.7% (527) | 581 |

| Other nationals | 9.6% (90) | 90.4% (849) | 939 |

| Difference between UK/non-UK ‘positive/very positive’ | 0.3% | 1,520 |

BME shoppers were slightly more likely to report positive treatment than White shoppers, and less likely to report negative treatment (Table 8). Again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Table 8: Perceived favourable/unfavourable treatment, by shopper ethnicity (White/BME)

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a response, excluding ‘neutral’ (n = 1,520). P = 0.83; not statistically significant.

| Negative | Positive | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 9.7% (57) | 90.3% (532) | 589 |

| BME | 9.3% (87) | 90.7% (844) | 931 |

| Difference between White/BME ‘positive/very positive’ | -0.4% | 1,520 |

Notes:

- Negative includes ‘negative’ and ‘very negative’, positive includes ‘positive and ‘very positive’.

2.4 Supporting documentation

Moving forward in the letting process, shoppers were asked if the letting agent or landlord had asked for any supporting documentation. The Government’s code of practice says that documents should be checked for all tenants, whether or not they appear to be UK nationals. However, of the shoppers who answered this question, only a minority (41%, 803 out of 1,976) were asked for any documents at all (Table 9). This was true of both UK and non-UK nationals.

Many landlords and letting agents carry out Right to Rent document checks as one of the final tasks before a tenancy was agreed; others use specialist third-party firms to check references and documentation – again, only after the tenancy is agreed. In such cases, the document checks would not be captured by the mystery shopping exercise, which covered only the early stages of the landlord/prospective tenant encounters. This was confirmed by the free-text remarks of the mystery shoppers, which allowed them to record impressions of their experience in some detail. They indicated that, in general, Right to Rent documents were not mentioned during early encounters. There were 1,975 responses to the question “Were you asked (by the landlord or agent) to provide/told you would need to provide any documentation or other proofs?”. The following verbatim responses were typical:

“Documentation not mentioned.”

“I was not asked for any documentation.”

“Nothing was requested.”

In cases where documentation was mentioned (41%, 803 out of 1,976), the items most often requested related not to Right to Rent but rather to general suitability as a tenant and ability to pay – for example, proof of income, employers’ references and references from previous landlords. One mystery shopper said:

“I was told I would need to provide a landlord reference and 3 months’ payslips. They also checked I’m not receiving benefits, ‘no DSS’ [(former) Department of Social Security].”

Another mystery shopper said:

“The landlord did not ask me to provide proof of identification and came across as more concerned about how I will be able to pay for the accommodation.”

Table 9: Documentation or other proof requested by letting agent/landlord

Base: All mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 1,976).

| Document | n | % | Acceptable proof of Right to Rent? |

|---|---|---|---|

| None asked for | 1,173 | 59.4% | |

| Proof of employment | 529 | 26.8% | Letter of attestation from employer List A Group 2 |

| Proof of income | 496 | 25.1% | No |

| Proof of address | 362 | 18.3% | No |

| UK driving licence | 141 | 7.1% | List A Group 2 |

| UK passport | 123 | 6.2% | List A Group 1 |

| Proof of right to reside in the UK | 113 | 5.7% | List A Group 1 |

| Original UK birth certificate | 35 | 1.8% | List A Group 2 |

| UK immigration document | 27 | 1.4% | List A Group 1 |

| UK biometric residence permit | 23 | 1.2% | List A Group 1 |

| UK biometric residence card | 22 | 1.1% | List A Group 1 |

| EEA/Swiss passport | 5 | 0.3% | List A Group 1 |

| EEA/Swiss national ID card | 2 | 0.1% | List A Group 1 |

| Other documentation | 384 | 19.4% | N/A |

Notes:

- EEA = European Economic Area (EU Member States, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway). Switzerland is not in the EEA but is part of the EU’s single market.

The mystery shoppers also recorded landlords/letting agents’ reactions when they heard what documents the applicants could provide. Fewer shoppers responded to this question (41%, 803 out of 1,976), as most landlords/letting agents did not ask for documents at all – it should be noted that, as referenced above, requesting documentation is often the final step in agreeing a tenancy and hence outside the scope of the mystery shopping exercise. It can be hypothesised that should a tenancy have been agreed, the proportion of landlords and agents requesting documentation would have increased accordingly. However, some mystery shopper’s responses reflected confusion among landlords and letting agents about the rules and what documentation was acceptable:

“The agent seemed cautiously optimistic that one or a combination of documents I offered, such as, payslips, a UK driving licence, a UK birth certificate and personal/employer references would work. He still suggested that they would need to establish why I was in the country.”

Not being able to produce a UK passport caused problems during any early identification checks for some applicants. One applicant said in response to the question ‘If/when you said you did not have a British passport, did the agent/landlord suggest this would be a problem?’:

“The agent found it very difficult to accept that I do not have a passport. Probably because they’ve never come across this situation before. After me offering him to present my driving licence and even birth certificate, still the agent was not convinced. I asked him direct question that ‘is this going to be a problem?’ To which he answered ‘Yes’. When I said surely there are many other people who do not have passport what do they do? He then said he is not sure so he will consult with his senior colleague to see if birth certificate is acceptable. He promised to call back by Monday.”

Another said:

“I said I could not provide a UK passport and they handled it professionally by asking if I had any other forms of documentation such as a driving licence or birth certificate. However, they said that a UK passport would be preferred and asked if there was any way that I could get one.”

In the quantitative survey of landlords, 14% (42 out of 300) said that they were unwilling to let to UK nationals without a passport (see section 3.1.1 of the report)[footnote 14]. For context, this compares with 38% (114 out of 300) for Housing Benefit or Local Housing Allowance recipients, 36% (109 out of 300) for Universal Credit recipients and 13% (40 out of 300) for people with dependent children.

The mystery shopping exercise was designed to enable comparison of ‘success’ rates for those holding different types of documentation: Scenarios 2 and 3 were designed to compare the experience of those holding documents from Group 1 compared with those with Group 2 documentation[footnote 15]. It should be emphasised that in most cases, landlords and letting agents were unaware of the documents that the mystery shoppers held, because they did not ask about them.

The experience of shoppers who were asked about their documents differed depending on the nationality of the shopper (Table 10). Amongst those with Group 1 documents, non-UK nationals were more likely than UK nationals to be asked what their nationality was (7% compared with 2%), and whether they had residency status or leave to remain in the UK (8% of non-UK nationals were asked this question compared with none of the UK shoppers). A similar pattern was seen amongst those with Group 2 documents (Table 11).

Both nationality and residency status/leave to remain in the UK are relevant to establishing that a prospective tenant has the right to rent. The fact that non-UK nationals were more likely to be asked these questions than UK nationals is therefore not unexpected, although Home Office guidance does state that it is good practice for landlords and letting agents to ask all prospective tenants to demonstrate that they have the right to rent[footnote 16].

Table 10: Right-to-Rent indicators: Differences in treatment of mystery shoppers with Group 1 documents on the basis of nationality

Base: All mystery shoppers with Group 1 documentation who received a response (n = 963).

| UK nationals | Non-UK nationals | Difference between UK/non-UK | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asked for nationality | 2.1% (5) | 7.2% (52) | -5.1%** |

| Asked for residency status/leave to remain in the UK | - | 7.9% (57) | - |

| Asked if passport held | 7.2% (17) | 11.8% (86) | -4.6%* |

| Asked if UK passport held | 0.4% (1) | 1.1% (8) | -0.7% |

| If no, told lack of UK passport would be a problem | - | 1.1% (1) | - |

| Asked for any documentation (not only right to remain in the UK) | 43.5% (103) | 37.5% (272) | 6.0% |

Notes:

- UK nationals BME only; non-UK nationals both White and BME.

- “**” represents statistical significance at 99% confidence level (p<0.01).

- “*” represents statistical significance at 95% confidence level (p<0.05).

Table 11: Right-to-Rent indicators: Differences in treatment of mystery shoppers with Group 2 documents on the basis of nationality

Base: All mystery shoppers with Group 2 documentation who received a response (n = 963) (Both UK and non-UK nationals include White and BME testers).

| UK nationals | Non-UK nationals | Difference between UK/non-UK | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asked for nationality | 2.4% (13) | 8.1% (39) | -5.6%* |

| Asked for residency status/leave to remain in the UK | - | 8.5% (41) | - |

| Asked if passport held | 9.4% (50) | 12.9% (62) | -3.4% |

| UK passport | 1.1% (6) | 1.5% (7) | -0.3% |

| If no, told lack of UK passport would be a problem | 17.9% (10) | 1.4% (1) | 16.4%* |

| Asked for any documentation (not only right to remain in the UK) | 41.4% (220) | 43.2% (208) | -1.7% |

Notes:

- “**” represents statistical significance at 99% confidence level (p<0.01).

2.5 Matched-pairs testing of ‘success’ indicators

The preceding tables report aggregate results for shoppers, as a whole, and relevant subsets. The next section looks at ‘success’ using matched-pairs testing. Each of the 4 scenarios had 2 groups of shoppers, who differed only in the aspect being tested (ethnicity, nationality or type of document held). Comparing the treatment of the pairs allows the effects of a single variable to be isolated. At the same time, however, the sample size is reduced as the matched-pairs testing is carried out separately for each scenario. Scenarios had between 288 and 319 pairs of shoppers (see Table 20 in the Appendix, section 4.1.1).

As above, the principal indicator of ‘success’ was whether shoppers were told that properties were available. In Scenario 1 (all shoppers UK nationals; half White, half BME; same documents), each landlord or letting agent in the sample received one approach from a White shopper, and another from a BME shopper with similar characteristics apart from ethnicity. Comparing the results of these encounters makes it possible to isolate the effect of ethnicity.

In 60% (138 out of 231) of cases, both White and BME shoppers got the same response in terms of whether properties were available (Table 12). In 23% (53 out of 231) of cases, White shoppers were told that properties were available and BME shoppers were told that there were none. In 17% (40 out of 231) of cases, BME shoppers heard that there were properties available while White shoppers heard there were none.

There have been several large-scale studies in the USA into the incidence of discrimination in the housing industry (see the Appendix, section 4.1.1)[footnote 17]; in such studies it is normal to calculate a ‘net incidence of discrimination’ by subtracting the score for the ‘test’ group (in this case BME shoppers) from the score for the ‘control’ group (here White shoppers). The net incidence of discrimination on the basis of ethnicity was found to be 6%, indicating that there may have been some systematic race discrimination, although this was not statistically significant, nor was this attributable to the Right to Rent scheme itself.

Table 12: Matched-pair testing: Effect of ethnicity on whether properties were available

Base: All Scenario 1 mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 231). P = 0.13; not statistically significant.

| Same response received | White yes, BME no | BME yes, White no | Net incidence of discrimination |

|---|---|---|---|

| 59.7% (138) | 22.9% (53) | 17.3% (40) | 5.6% (13) |

The same exercise was carried out for Scenario 4 to assess the impact of nationality. In Scenario 4, half of the shoppers were British and half were African or South Asian nationals; all were BME, and all had Group 1 documents. In total, 63% (129 out of 206) of the pairs received the same response with regards to property availability. In 22% (46 out of 206) of cases, UK nationals were told that there were properties available and non-UK nationals were told that there were not. In 15% (31 out of 206) of cases, non-UK nationals heard that there were properties available while UK nationals heard there were none (Table 13). The net incidence of discrimination was 7%, indicating again that there may have been some systematic discrimination against non-UK national prospective tenants, although again the difference was not statistically significant, nor was this attributable to the Right to Rent scheme itself.

Table 13: Matched-pair testing: Effect of nationality on whether properties were available

Base: All Scenario 4 mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 206). P = 0.06; not statistically significant.

| Same response received | UK yes, non-UK no | Non-UK yes, UK no | Net incidence of discrimination |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62.6% (129) | 22.3% (46) | 15.0% (31) | 7.3% (17) |

The final question to be assessed was whether there was evidence of discrimination on the basis of the type of documentation held – that is, whether those who could demonstrate the right to rent by producing a single document (List A Group 1) were treated more favourably than those who would need to produce a combination of other documents (List A Group 2). Two scenarios were relevant here. In Scenario 2, all shoppers were White non-EEA Eastern European nationals, half of whom had Group 1 documents and half of whom had Group 2 documents. In Scenario 3, all shoppers were BME shoppers with African or South Asian nationality; again, half had Group 1 documents and half Group 2.

Normally, the control group in an experimental test of this kind represents ‘business as usual’–that is, they undergo the same experience as they would in the absence of a policy change. In this case, however, both sets of shoppers were actually ‘test’ groups. It might be argued that landlords would prefer the simpler document-handling procedure, and therefore would favour those tenants who could demonstrate eligibility on the basis of a single document rather than a combination of documents. Following that logic, the analysis considered the single-document shoppers to be the control group and the multiple-document shoppers the test group.

The results of the matched-pair testing for White non-UK nationals (Table 14) and BME non-UK nationals (Table 15) gave different results with no clear pattern or direction of effect. For White testers, those with a combination of documents were more ‘successful’ in terms of learning about available properties, while amongst BME testers, those who could demonstrate right to rent with a single document were more ‘successful’.

However, it should be borne in mind that only 40% of shoppers were asked about documents at all in the course of their mystery shopping encounters. This means that most landlords and agents would have been unaware of whether shoppers had Group 1 or Group 2 documents. As a result, it was not possible to draw clear conclusions on the effect of documentation type.

Table 14: Matched pair testing: Effect of Group 1 compared with Group 2 documents on whether properties were available for White non-UK nationals

Base: All Scenario 2 mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 196). P = 0.001; statistically significant at 99% confidence level.

| Same response received | Single document yes, combination of documents no | Combination of documents yes, single document no | Increase in success with multiple documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71.4% (140) | 8.7% (17) | 19.9% (39) | 11.2% |

Table 15: Matched-pair testing: Effect of Group 1 compared with Group 2 documents on whether properties were available for BME non-UK nationals

Base: All Scenario 3 mystery shoppers who received a response (n = 215). P = 0.29; not statistically significant.

| Same response received | Single document yes, combination of documents no | Combination of documents yes, single document no | Increase in success with single document |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68.4% (147) | 17.7% (38) | 14.0% (30) | 3.7% |

3. Detailed findings: Landlords primary research

3.1 Discrimination

The key focus of the research investigation was discrimination on the basis of nationality, race or ethnic background, and this is the primary focus of this section of the report. However, in the landlord’s primary research, information was also collected on other forms of discrimination such as against benefit claimants or recipients of Local Housing Allowance (LHA). The following sections first discuss overall discrimination in general terms, followed by discrimination on the basis of nationality, race or ethnic background, and finally, other forms of discrimination (predominantly against individuals in receipt of Universal Credit, Housing Benefit or LHA).

3.1.1 The broader context of discrimination

In the quantitative survey, landlords were given a pre-coded list of tenant types and asked which (if any) they would be unwilling to let to. Almost one-third (30%, 211 out of 300) of landlords claimed to be willing to let to any tenant type listed (Table 16)[footnote 18]. However, 70% of landlords admitted to being unwilling to let to at least one tenant type, with benefit claimants being by far the most likely to be discriminated against (Universal Credit or Housing Benefit/LHA).

Table 16 shows that almost half (49%, 148 out of 300) of landlords said that they would not let property to single occupants aged 18 to 21, receiving Universal Credit, 38% (114 out of 300) would not rent to people receiving Housing Benefit or LHA, and 36% would not rent to either single occupants receiving Housing Benefit (109 out of 300) or to people receiving Universal Credit (107 out of 300).

Table 16: Percentage of landlords unwilling to let to each tenant type, by wave

Base: All landlords (Wave 1 n = 309; Wave 2 n = 300; Wave 3 n = 300).

| Tenant type | Wave 1 (January 2020) | Wave 2 (October 2020) | Wave 3 (January 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to let to all tenant types | 24.6% (76) | 26.0% (78) | 29.7% (89) |

| Single occupants (aged 18 to 21) receiving Universal Credit | 52.4% (162) | 49.7% (149) | 49.3% (148) |

| People receiving Housing Benefit or LHA | 42.7% (132) | 40.3% (121) | 38.0% (114) |

| Single occupants (under 35) receiving Housing Benefit | 41.4% (128) | 40.7% (122) | 36.3% (109) |

| People receiving Universal Credit | 40.8% (126) | 42.0% (126) | 35.7% (107) |

| Non-UK passport holders from outside the EU | 28.2% (87) | 31.7% (95) | 23.7% (71) |

| UK nationals without a passport | 14.6% (45) | 22.3% (67) | 14.0% (42) |

| Non-UK passport holders from the EU | 17.5% (54) | 21.3% (64) | 13.7% (41) |

| Couples or single people with dependent children | 14.9% (46) | 14.3% (43) | 13.3% (40) |

| Other | 5.8% (18) | 6.3% (19) | 4.3% (13) |

The proportion of landlords unwilling to let to benefit claimants exceeds those of the 24% (71 out of 300) who would not let to individuals from outside the EU and the 14% (41 out of 300) who would not let to non-UK passport holders from the EU. This is discussed further in sections 3.1.2 and 3.1.3 below.

As a useful comparative context, 25% of respondents to the 2018 MHCLG English Private Landlord Survey were unwilling to let to non-UK passport holders, although the underlying reasons for this were not explored in that research.

3.1.2 Discrimination on the basis of nationality, race or ethnic background

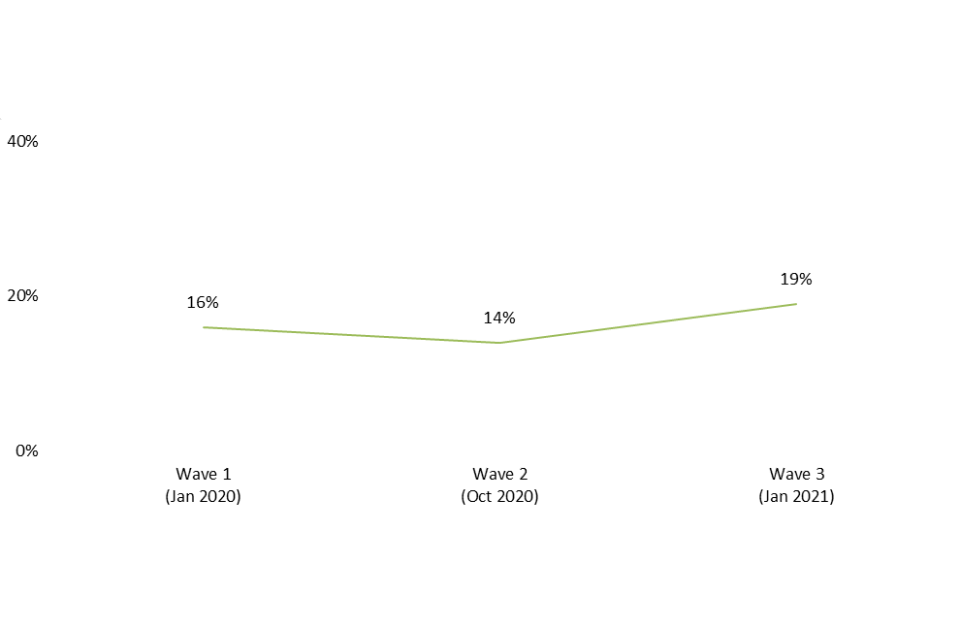

When asked if they were aware of discrimination against tenants on the basis of their nationality, race or ethnic background, the majority of landlords (67%, 200 out of 300) claimed not to be aware of such discrimination. However, 19% (56 out of 300) said that they were aware of discrimination in the (geographical) areas where they operate (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage of landlords aware of discrimination on the basis of nationality, race or ethnic background in the areas where they operate, by wave

Base: All landlords (Wave 1 n = 309; Wave 2 n = 300; Wave 3 n = 300).

Although almost one in 5 landlords (19%, 56 out of 300) claimed to be aware of discrimination, very few could give a specific example of such in the quantitative interview. Those who did provide an example generally mentioned hearing of incidences of discrimination from other landlords or (less commonly) from tenants discussing previous poor experiences. Examples of overall discrimination (not specific to Right to Rent) provided by landlords included:

“I know of a landlord who does not rent to Black people but uses other excuses for not letting them rent from them. He has been open to me about his preference for White renters but it [is] very hard to prove this is what they are doing, as they find other excuses to say no to them.”

“Tenants I have housed have previously been rejected from properties because they were non-UK citizens (they were EU citizens).”

As demonstrated in Table 16 in section 3.1.1, when asked which tenant types landlords are unwilling to let to, 24% (71 out of 300) of landlords said that they were unwilling to let properties to non-UK passport holders from outside the EU, and 14% (41 out of 300) were unwilling to rent to non-UK passport holders from the EU. These figures declined in Wave 3 compared with Wave 1 (28% and 17%) and Wave 2 (32% and 21%)[footnote 19].

In addition, 14% of private landlords were unwilling to let to UK nationals without a passport. This figure was higher among those who consider themselves well or quite well informed about the Right to Rent scheme (Table 17) as well as those who have read any of the documentation available on GOV.UK[footnote 20] (18%) (Table 18). These differences were statistically significant, indicating a marginal influence of the Right to Rent scheme.

Table 17: Percentage of landlords unwilling to let to UK nationals without a passport, by knowledge of the Right to Rent scheme

Base: All in Wave 3 (n = 300). P = 0.04; statistically significant at 95% confidence level.

| Total % | Well/quite well informed | Poorly/not at all informed | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14.0% (42) | 17.5% (28) | 9.1% (12) | 8.4% (16) |

Table 18: Percentage of landlords unwilling to let to UK nationals without a passport, by engagement with documentation on GOV.UK[footnote 12]

Base: All in Wave 3 (n = 300). P = 0.04; statistically significant at 95% confidence level.

| Total % | Read any documentation on GOV.UK | Not read any documentation on GOV.UK | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14.0% (42) | 17.8% (29) | 9.5% (12) | 8.3% (17) |

The qualitative research suggests that there is a spectrum of discrimination around race, ethnicity or nationality. At one extreme are landlords who appear to enjoy housing tenants from a range of different nationalities, as it is an opportunity to get to know and mix with people who are from different backgrounds to themselves. At the other extreme are a minority whose discriminatory views are overt or had heard of cases where landlords had more extreme views with comments collected in qualitative research including:

“If you didn’t have that sort of background [White middle-class], I think the letting agents used to quietly weed you out.”

“Some people don’t let Brown people in.”

In qualitative research a minority of landlords also demonstrated clear biases, for example, only wanting to rent to people within their own community (such as South African landlords to South African tenants) or based on perceptions that certain ethnic groups were likely to behave in certain ways within a rental property. A specific example given was that Asian people were perceived as more likely to cook with large amounts of oil and dispose of it in a sink and block it, and that certain ethnic groups were less likely to look after a garden. In both examples, landlords felt ‘justified’ in their decision because having these groups of people as tenants would incur additional costs to rectify any issues (in this case with a blocked sink or unkempt garden). There was also an example of a landlord who would not let to tenants who do not speak English:

“Some landlords have a personal bias against certain groups of people or certain organisations, for example, they may be against certain religious groups. And some landlords will not deal with people who don’t speak English, they are not confident that these tenants can understand and follow the rules and terms of their tenancy agreements.”

Landlords also spoke about the importance of being able to keep a track of tenants to follow-up post-tenancy, if needed, and expressed concerns that they may not be able to do so with foreign nationals. In this light, landlords quite often spoke about wanting to rent to families as they had more of a ‘paper trail’ with children registered at school and so on.

“Foreign tenants are harder to track if they leave and are in arrears or have caused damage to the property.”

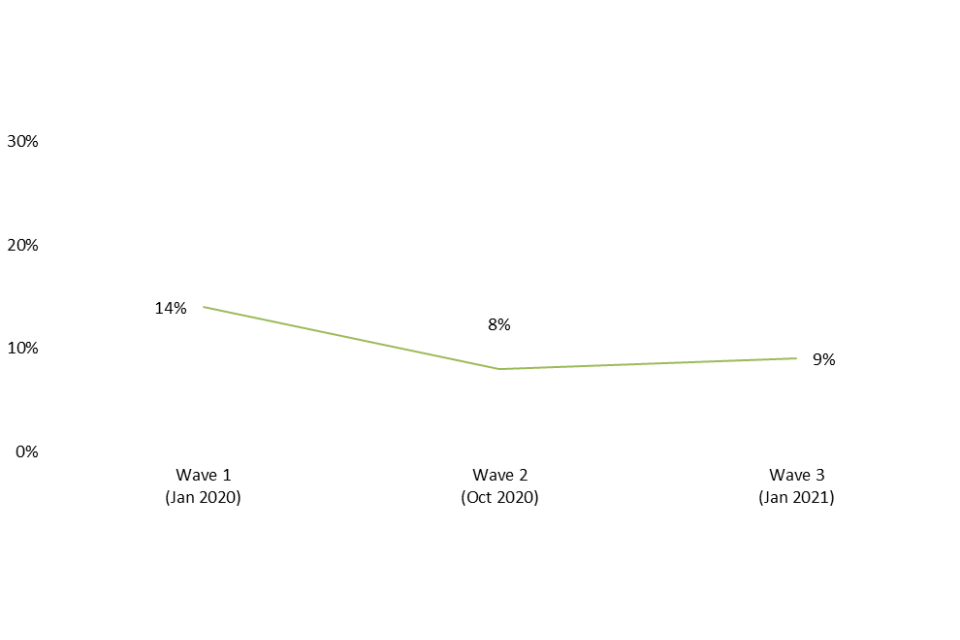

As well as overall discrimination, in the quantitative survey landlords were asked if they were aware of discrimination against tenants as a direct impact of the Right to Rent scheme; 9% of landlords in January 2021 (26 out of 300) claimed to be aware of such (Figure 3), although (as with broad discrimination) when asked to give a specific example either no examples or vague examples were provided in the majority of those 26 cases. Awareness appears to have marginally decreased since 14% claimed awareness in January 2020 (42 out of 309).

Figure 3: Percentage of landlords aware of discrimination as a specific impact of the Right to Rent scheme in the areas where they operate, by wave

Base: All landlords (Wave 1 n = 309; Wave 2 n = 300; Wave 3 n = 300).

Awareness of discrimination as a result of the Right to Rent scheme was higher among:

- landlords who let property in London (20%, 12 out of 60)

- those who are members of a landlord membership body or association (19%, 20 out of 105)[footnote 21]

- those who consider themselves very or quite well informed about the Right to Rent scheme (14%, 22 out of 160)

All of these differences were statistically significant. There was only one example in qualitative research where it was felt that the Right to Rent scheme provided a tool for a landlord to discriminate against tenants due to their ethnicity.

In addition to general discrimination, 7% (22 out of 300) of landlords claimed that they were aware of tenants being denied access to rental property because they could not prove that they had a legitimate right to rent. The reasons given for this were commonly because (potential) tenants lacked the correct documentation:

“The letting agent informed me that another landlord had been unable to get the required documentation from prospective tenants.”

“The prospective tenant did not have some of the documents for the ID check.”

3.1.3 Other forms of discrimination

As mentioned in section 3.1.1, the most common tenant types to not rent property to were people receiving benefits (Table 16), particularly single occupants aged 18 to 21 years receiving Universal Credit (49%, 148 out of 300), people receiving Housing Benefit or Local Housing Allowance generally (38%, 114 out of 300) and single occupants aged under 35 receiving Housing Benefit (36%, 109 out of 300).

This was borne out in qualitative research and the comments around these groups far outweighed comments around race, ethnicity or nationality. Benefit claimants were avoided or excluded because of the risk of the landlord not receiving their rental payments; this is exacerbated by the Universal Credit scheme where the tenant receives payment to provide to the landlord rather than the payment being paid directly to the landlord.

There were also a number of comments in the qualitative research regarding a preference not to rent to younger people (especially students). There was more risk associated with this group because of potential property damage and noise inflicted on neighbours who the landlord wished to keep ‘on side’.

3.2 Awareness of the Right to Rent scheme

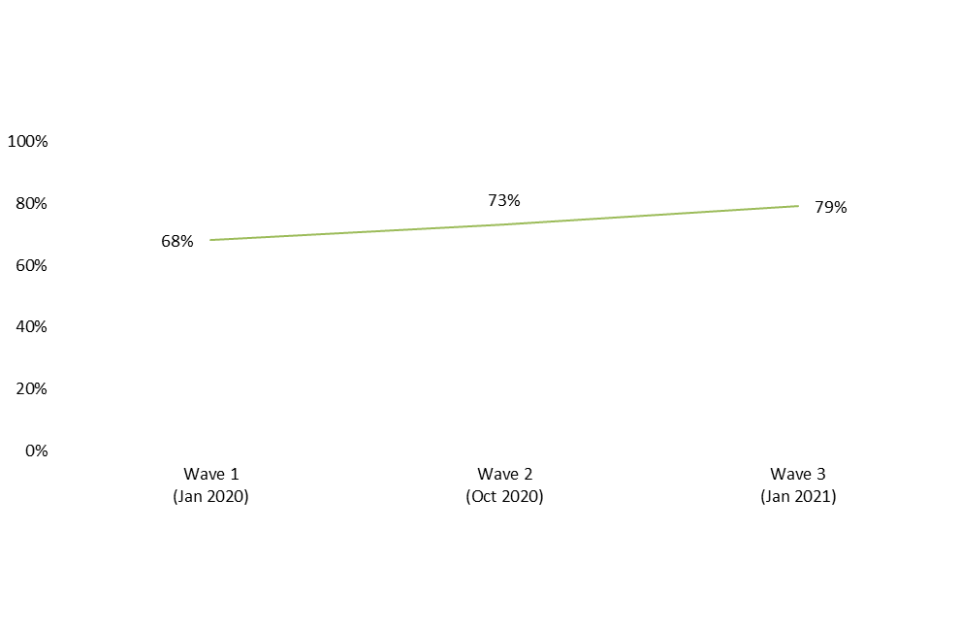

At the start of the quantitative survey, landlords were asked if they were aware of the Right to Rent scheme prior to completing the survey. Awareness of the Right to Rent scheme among UK landlords was relatively high at 79% (236 out of 300) and has increased from 68% (209 out of 309) in January 2020 (Figure 4). Among landlords letting out property in England, awareness was marginally higher at 81% (213 out of 263). However, only half (53%, 160 out of 300) of all landlords considered themselves to be well or quite well informed about the Scheme, with 44% (132 out of 300), considering themselves poorly or not at all informed.

Figure 4: Percentage of landlords aware of the Right to Rent scheme, by wave

Base: All (Wave 1 n = 309; Wave 2 n = 300; Wave 3 n = 300).

In qualitative research, awareness of the Right to Rent scheme was less clear (although all landlords needed to have at least heard of the Scheme to participate in the qualitative research stage). For landlords who handled searching and vetting tenants themselves and had no contact with a letting agent or were not a member of a landlord membership body, the ability to get information about Right to Rent was impaired. Quite often these landlords had heard about the Scheme in an informal manner, such as through friends or colleagues; there was also an example of a landlord having happened upon the information via a radio talk show.

Several landlords mentioned not having needed to replace tenants since 2015 (before the Scheme was implemented), and these individuals were less likely to understand their responsibilities under the Scheme. This led to some concern amongst landlords that they didn’t know a great deal about the Scheme and were concerned they might be missing something. Wishing to avoid falling foul of the Scheme, quite often landlords left the qualitative research interview wanting to look up more information to check they were doing the right thing; this led to some curiosity as to what the Right to Rent scheme online tool (discussed in the interview) might do for them. Improved communication to private landlords to raise awareness of the Right to Rent scheme and landlord responsibilities could play a significant impact in improving understanding of the Scheme, and therefore implementation of it. This could be initiated by the Home Office with support from relevant industry bodies.

In total, 55% (164 out of 300) of landlords said that they have a positive opinion of the Right to Rent scheme (Figure 5) (a statistically significant increase since January 2020 with 44% positive, (136 out of 309). Greater familiarity appears to lead to a more positive opinion of the Scheme, as 62% of landlords who were already aware of the Scheme (147 out of 236), and 75% of those who were well or quite well informed about the Scheme (120 out of 160), had a positive opinion of it.

Figure 5: Percentage of landlords with a positive opinion of the Right to Rent scheme, by wave

Base: All (Wave 1 n = 309; Wave 2 n = 300; Wave 3 n = 300).

Landlords were also asked to provide the reasons for their stated opinion of the Right to Rent scheme; the reasons provided are spontaneous (that is, not prompted). The key reasons cited for a positive opinion towards the Right to Rent scheme were:

- that it is a good/worthwhile idea (28%, 46 out of 164)

- that it protects the landlord/provides an additional layer of security (17%, 28 out of 164)

- that it ensures that tenants are legitimate (16%, 27 out of 164)

Positive comments from landlords included:

“It is an extra layer of protection for me, to ensure that there would be no lengthy and costly evictions if I took on someone who shouldn’t be renting in the first place.”

“I think it is a good way to check potential tenants and ensure they are able to rent.”

In contrast, the key reason for a negative opinion towards the Scheme was that the responsibility for immigration checks should not fall on landlords (42%, 19 out of 45), and this has increased considerably since January 2020 (19%, 9 out of 48) and October 2020 (33%, 16 out of 48). Given the timings of these waves of research (Wave 3 in January 2021), it is a possibility that this increase in a belief that Right to Rent checks should not fall on landlords could have been influenced by the UK leaving the EU in December 2020. Negative comments about the Scheme included:

“It’s hard to avoid discrimination and whilst it hasn’t increased my workload it has considerably increased my costs. I’m also nervous about inadvertently breaching it.”

“I think it has the ability to discriminate unfairly, for example, Windrush scandal.”

There was a low incidence of complaints about the Right to Rent scheme from tenants themselves, with only 5% of landlords (16 out of 300) saying tenants had made a complaint or raised a concern about it.

Landlords were also asked to provide suggestions for improving awareness of the Right to Rent scheme. These included television advertising, encouraging letting agents to pass on the information, and contacting landlords directly (for example through HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC). In qualitative research there was some discussion on information reaching landlords directly by linking tax return information via HMRC to the relevant government department (that is, the Home Office) to tell them about Right to Rent.

3.3 Information engagement

In the next section of the questionnaire, landlords were asked questions on their engagement with the documentation available on GOV.UK[footnote 22]. Over half of landlords (54%, 163 out of 300) claimed to have read at least one of the documents available, and 31% (92 out of 300) had used at least one document. In addition, two-thirds (66%, 197 out of 300) of landlords said that they had accessed information about the Right to Rent scheme from another source, most commonly a letting agent (36%, 109 out of 300). However, 28% (83 out of 300) of landlords had not accessed any form of information about the Scheme.

There was relatively low usage of the GOV.UK online tool ‘Check if someone can rent your residential property’, with 28% of landlords (85 out of 300) saying they had used it (Figure 6). However, usage was higher among landlords who carry out tenant checks themselves (50%, 44 out of 88) or who use a tenant referencing service (56%, 34 out of 61) compared to those who use a letting agent (21%, 41 out of 193). These differences were statistically significant. The vast majority of landlords who did use the tool found it helpful and did not experience any problems.

Figure 6: Percentage of landlords using the online tool, ‘Check if someone can rent your residential property’, by wave

Base: All (Wave 1 n = 309; Wave 2 n = 300; Wave 3 n = 300).

3.4 Tenant checks

In both the quantitative and qualitative research, landlords were asked about their normal procedure when carrying out tenant checks. The majority of landlords (64%, 193 out of 300) said that they use a letting agent to carry out Right to Rent checks on prospective tenants. A further 20% (61 out of 300) use a tenant referencing service, while 29% of landlords (88 out of 300) carry out Right to Rent checks themselves. [Note: landlords may use multiple methods to carry out tenant checks, so percentages add to more than 100%].

In qualitative research there was a mixture of individuals who used letting agents or checking services to check tenants; they did so because of the time and hassle it would take to do the checks themselves, and because it handed the responsibly to another body. Those landlords who do carry out tenant checks themselves often spoke about using their ‘gut feel’ for finding suitable tenants or using a personal network to find tenants. With the latter, there was some word-of-mouth approval or just judging the character of the tenant from, for example, what they were wearing or if they had turned up to a meeting on time. Checks were therefore less formal, but certain elements were still in place, such as formal rent agreements and financial capability checks, as well as landlords claiming that they followed the Right to Rent process. In this light the Right to Right scheme was talked about relatively positively; although in some cases it is awkward to ask a tenant for proof of residency, using the Right to Rent scheme as a process gave the landlord legitimate ‘permission’ to seek this information from prospective tenants.

Around 2 in 3 landlords (67%, 201 out of 300) said that they feel very or quite confident carrying out the checks required under the Right to Rent scheme. This was higher among landlords who carry out checks themselves (81% confident, 71 out of 88) and those who use a referencing service (80% confident, 49 out of 61). These differences were statistically significant. However, one-fifth of the landlords who do carry out checks themselves (19%, 17 out of 88) said that they do not feel confident doing so.

Confidence in carrying out checks varied considerably depending on the documents available for checking, as 83% of landlords (249 out of 300) said that they feel confident checking a UK passport, while only 39% (117 out of 300) felt confident checking a European Economic Area (EEA)/Swiss national ID card (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Percentage of landlords feeling confident using each form of documentation to check a potential tenant’s right to rent

Base: All in Wave 3 (n = 300)

In terms of time taken to carry out checks, one-fifth of landlords (20%, 61 out of 300) perceived the Right to Rent scheme to have impacted their workloads, with 5% (14 out of 300) of these indicating that their workload had increased a great deal. In contrast, 76% (228 out of 300) said that their workload had not changed much or not at all (primarily individuals who employ a letting agent to carry out tenant checks).

3.5 Impact of COVID-19

At the end of the questionnaire landlords were asked about the impact of COVID-19 on their lettings business. Just over half of landlords (56%, 169 out of 300) said that they have not experienced any changes since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For the 44% (131 out of 300) who had experienced changes, the most common was tenants struggling financially (20%, 60 out of 300) and a reduction in profitability (19%, 58 out of 300).

In qualitative research there were some landlord experiences where tenants had been made redundant due to the pandemic and were either unable to pay their rent or paying it at an extremely low level. Landlords found this frustrating as many were out of pocket financially because of the COVID-19 tenant protection schemes.

Verbatim comments from landlords commonly mentioned the difficulty of evicting problem tenants, with some mentions of difficulty finding new tenants and visiting the property for maintenance or to carry out checks.

“Some landlords have been left badly out of pocket by tenants not paying and not being allowed to evict them. Many businesses have been given support, tenants have been given more rights, but landlords have been strung out to dry and left with no support. The Government seems to treat private landlords as bad guys when they actually provide a lot of affordable housing, something the Government has been very bad at doing.”

“It has made it virtually impossible to remove problem tenants. Also, there have been delays and difficulties getting work carried out during the crisis.”

“It would be helpful to continue to allow viewing of properties whilst of course maintaining social distancing, to the benefit of both potential tenants and landlords.”

Portfolio size was the most strongly differentiating factor on whether COVID-19 had impacted landlords: landlords with only one property were more likely to have experienced no changes compared with those with multiple properties, a statistically significant difference.

Only 19% of landlords (46 out of 236) who were already aware of the Right to Rent scheme were also aware of the changes to guidance on conducting checks as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Of these, almost half (43%, 20 out of 46) said that the changes have made it easier to conduct Right to Rent checks, and a further third (30%, 14 out of 46) noticed no difference. Just over half (54%, 25 out of 46) of landlords who were aware of the change thought that it would have an impact on discrimination, of which 41% (19 out of 46) expected a positive impact and 13% a negative impact (6 out of 46).

Research conclusions

The overall question assessed in the research was whether the Right to Rent scheme leads to unlawful discrimination on the basis of ethnicity or nationality.

Clear examples of discriminatory behaviour were found in the implementation of Right to Rent by landlords and letting agents, with mystery shopper ‘success’ outcomes varying according to nationality and ethnicity, and 19% of landlords claiming to be aware of tenants being discriminated against on the basis of their actual or perceived nationality, race or ethnic background.