Review of the controlling or coercive behaviour offence

Updated 10 May 2021

Applies to England and Wales

1. Executive summary

1.1 Background

On the 29 December 2015, the offence of controlling or coercive behaviour (CCB) came into force through Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015. The stated aim of this new offence was to “close a gap in the law around patterns of coercive and controlling behaviour during a relationship between intimate partners, former partners who still live together, or family members” (Home Office, 2015a). The Home Office has undertaken a rapid review of the CCB offence, to assess itseffectiveness and whether any changes to the legislation, or any wider policy interventions, are needed.

The review involved an assessment of the available quantitative data from the criminal justice system (CJS) and a review of the academic literature, both carried out by analysts in the Home Office. Separately, policy officials undertook a series of consultations with a targeted group of stakeholders to get views on the operational application and practicalities around the CCB offence.

1.2 Key findings

The number of CCB offences recorded by the police has increased from 4,246[footnote 1] in 2016/17 to 24,856[footnote 2] in 2019/20. In 2019[footnote 3], 1,112 defendants were prosecuted for CCB offences (either as the principal or non-principal offence[footnote 4]), which is an increase of 18% from the previous year. In addition, the average length of custodial sentences for CCB have consistently been longer compared with those for assaults (which are the most common domestic abuse-related offences recorded) and those for stalking[footnote 5].

These increases demonstrate that the CCB offence is being used across the CJS, indicating that the legislation has provided an improved legal framework to tackle CCB and that, where the evidence is strong enough to prosecute and convict, the courts are recognising the severityv of the abuse.

However, there is still likely to be significant room for improvement in understanding, identifying and evidencing CCB, as prevalence estimates[footnote 6] from the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggest that currently only a small part of all CCB comes to the attention of the police or is recorded as CCB. The literature and stakeholder engagement exercise point to difficulties for both victims and police inrecognising CCB, and academic studies have found specific examples of missed opportunities to record CCB. When attending domestic abuse incidents, it is vital that the police (including domestic abuse specialists) have the training and specialist resources needed to establish whether there are patterns of controlling or coercive behaviours underlying the incident that led to a police callout.

While volumes of CCB offences being recorded have increased each year, the proportion of CCB offences leading to a charge has decreased from 11% in 2017/18 to 6% in 2018/19.[footnote 7] However, falling charge rates have been seen across many offences over the same time period, and so do not necessarily reflect specific difficulties in charging CCB. A very high proportion of offences (85% in 2018/19) were finalised due to evidential difficulties (including where victims withdrew from the process), with both the literature review and the stakeholder engagement exercise highlighting that evidencing CCB is a significant challenge for police and prosecutors, likely due to the nature of CCB as a course of conduct offence that often includes non-physical abuse. Furthermore, while the conviction ratio for prosecutions (where defendants were charged withCCB as the principal offence) increased from 38% in 2016 to 60% in 2018; it then fell to 52% in 2019.

Most prosecutions involving CCB were for cases where there were co-occurring offences, for example, with offences of violence against the person. There are a number of plausible explanations for this. It may indicate that CCB is more likely to be reported or identified by the police when another offence occurs, or it could suggest that prosecutors may decide to charge CCB alongside another offence to not limit the potential custodial sentence length to the maximum sentence of five years for CCB. Further research and monitoring is needed to improve understanding of CCB trends and their drivers.

1.3 Limitations of the review and recommendations for further research

Due to the timing of this report, only four years of data were available for analysis to support this review, and there is limited research literature examining the impacts of the offence. As a result, it is not yet possible to draw definitive conclusions regarding the impacts and effectiveness of this new offence, including whether there is a need for legislative changes to be made.

There is also a lack of robust data on the prevalence of CCB, making it difficult to measure how effective the offence has been at capturing CCB offending, and how much remains undetected. There is no common statistical definition of CCB used across survey data, administrative data, and data from third-sector organisations, making it difficult to draw comparisons between different sources.

In addition, there is a lack of systematic data available across the CJS on the characteristics and nature of CCB offences and victim outcomes, which has hindered a more detailed analysis of how criminal justice outcomes may differ by the type of abuse or victim/perpetrator characteristics.

1.4 Research recommendations

-

Building on the previous work of the ONS in 2017/18, robust estimates of the prevalence and characteristics of CCB should be developed.

-

Work should be undertaken, in consultation with victims of CCB and with domestic abuse support services, to develop suitable measures on victim outcomes, with a view to monitoring outcomes for victims of CCB going forward.

-

The evidence collected suggests that while there have been improvements in the awareness and understanding of CCB legislation, due to the newness of the offence there may remain some confusion about when and how CCB should be investigated and charged. Further, there is evidence to suggest that investigating and building a case can be more time-consuming and complex than for other offences. It is therefore recommended that further research be undertaken across the CJS to assess the current levels of awareness and understanding of the legislation, and its application in practice, in order to identify any required changes to the available guidance and training.

-

The literature review along with the stakeholder engagement exercise provided some (limited) evidence pointing towards potential areas for legislative change. The most prominent among these is the suggestion that the legislation should be extended to encompass former partners who do not live together, due to a perception that some post-separation abuse is being missed, and that there may be confusion among police and prosecutors regarding how abuse which continues beyond the end of a relationship should be recorded and charged. Some academics and stakeholders expressed the view that the current stalking and harassment offences are not applicable or appropriate in all cases of post-separation abuse.

-

Some academics and stakeholders argued that the maximum sentence length for CCB should be increased from five to ten years in line with the current maximum sentence for stalking, based on the potential severity of CCB which may include both physical and non-physical violence over an extended period.

-

The review also found evidence of challenges in evidencing CCB. Among other explanations, some of the literature linked this tothe perceived high evidential threshold of proving a ‘serious effect’ on the victim, and the practical difficulties in collecting such evidence. As such it has been suggested within the literature that this element of the legislation could be revised, in line with the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018.

-

It must be highlighted, however, that due to the relative recency ofthe offence, the evidence in this area remains limited and the potential impacts of any such changes are not well evidenced. This review therefore puts forward the following recommendations.

- If legislative changes are implemented, the operation of the legislation should be monitored and reviewed to assess the impact of such changes and identify any unintended consequences.

- If legislative changes are not made at this time, further research should be undertaken to ascertain the need for, and impact of, such changes to the legislation. This should consider both the impacts on victims and on the CJS.

2. Introduction

2.1 Background to the review

On the 29 December 2015, the offence of controlling or coercive behaviour (CCB) came into force through Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015. The stated aim of this new offence was to close “a gap in the law around patterns of coercive and controlling behaviour during a relationship between intimate partners, former partners who still live together, or family members” (Home Office, 2015a, p 3).

The Government definition of CCB as set out in the statutory guidance (Home Office, 2015b, p 3) is as follows:

- “Controlling behaviour: a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.

- Coercive behaviour: a continuing act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.”

In addition, the controlling or coercive behaviour must take place “repeatedly or continuously”; the pattern of behaviour must have a “serious effect” on the victim; and the behaviour of the perpetrator must be such that they knew or “ought to know” that it would have a serious effect on the victim.[footnote 8]

It was also anticipated that the introduction of this offence would enable the criminal justice system (CJS) to move beyond an exclusively ‘violent incident model’ (Stark, 2012), in which incidences of domestic abuse are investigated and prosecuted as individual and unconnected occurrences of violence, which can mask the underlying patterns of coercion or control in an abusive relationship (Tuerkheimer, 2004).

The review consisted of three elements:

-

an assessment of the available quantitative data from the CJS carried out by analysts in the Home Office;

-

a review of the academic literature, also carried out by analysts in the Home Office; and

-

a stakeholder engagement exercise, which involved interviews, workshops and surveys with a targeted group of stakeholders, that was conducted by Home Office policy officials.

The short timelines of this review, which aimed to inform the Domestic Abuse Bill, have precluded the collection of bespoke data or detailed qualitative research such as case file analysis. In addition, there are only four full years of data available from most data sources, given the limited time since the introduction of the offence. As identified in Chapter 5, it is recommended that more detailed research is undertaken in the future, when more quantitative data and academic research are available.

2.2 Logic model

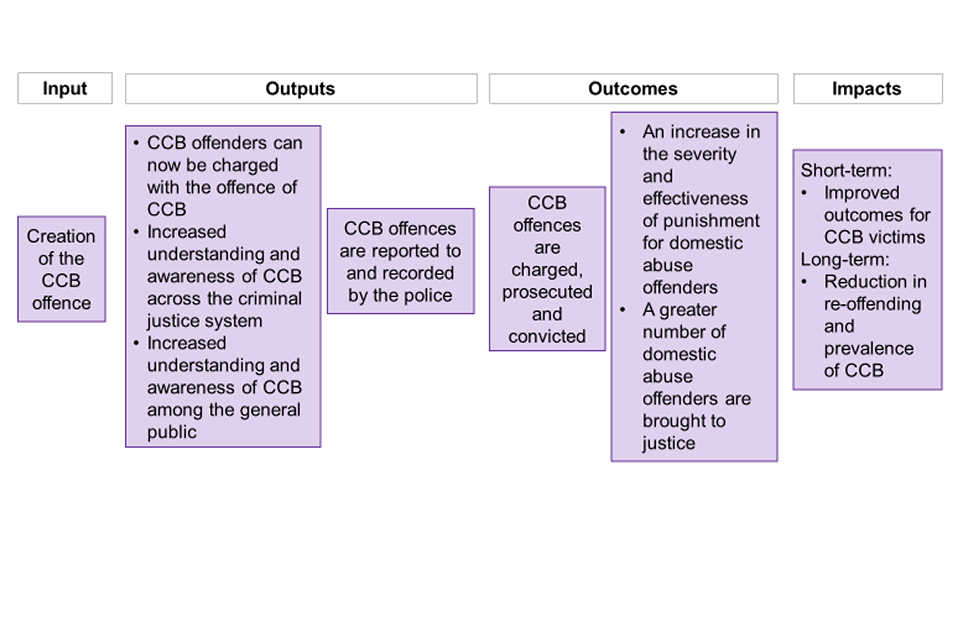

In order to undertake this review, Home Office Analysis and Insight, in collaboration with policy officials, developed a logic model in line with the Magenta Book guidance (HM Treasury, 2020). Logic models identify how a policy is expected to achieve its objectives, by mapping out the relationships between a policy’s inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts. They provide a useful framework to review or evaluate the realised impacts of a policy intervention. Figure 1 sets out the logic model developed for the CCB offence, drawing on related documents such as the accompanying impact assessment and statutory guidance.

Figure 1 - Logic model for the CCB offence

The logic model presented in this image sets out the anticipated impacts that the creation of the CCB offences was expected to have. A key expectation was that the offence would increase awareness and understanding of this type of abuse among the public and Criminal Justice System. Another key expectation was that it would provide the Criminal Justice System with a clearer and stronger legal framework to pursue cases of domestic abuse where there are ongoing or repeated patterns of CCB. As such, it was expected that there would a steady increase in the volumes of CCB offences being recorded by the police. And it was hoped that there would be a corresponding increase in the volumes of charges, prosecutions and convictions in cases of CCB. This, it was hoped, would result in an increase in the severity of punishments for perpetrators of controlling or coercive domestic abuse and would result in improved outcomes for victims of CCB. In the long-term, it was hoped, that improved awareness of CCB and greater severity of punishment for perpetrators would also lead to a reduction in reoffending and prevalence of CCB and improved outcomes for victims of CCB.

When the CCB offence came into force, statutory guidance was issued and communications on the new legislation were released. It was expected that the new offence would increase the understanding and awareness of CCB among the general public and across the CJS, including the police, the Crown Prosecution Service and the courts. In addition, it was anticipated that the offence would provide the CJS with a clearer and stronger legal framework to pursue cases of domestic abuse where thereare ongoing or repeated patterns of CCB.

It was expected that the introduction of this legislation would lead to CCB being reported to and recorded by the police as an offence, as patterns of CCB become recognised and evidenced by the police and other organisations. It was also anticipated to result in improved criminal justice outcomes (an increase in prosecutions, convictions, longer sentencing and the increased use of protection orders and perpetrator programmes where appropriate) for domestic abuse crimes, due to an increased awareness and understanding of the offence among the Crown Prosecution Service, judges and juries.

In terms of impacts, the new offence was intended to increase the number of offenders being brought to justice, and lead to stronger punishments in domestic abuse cases where CCB is present. It was also intended to improve outcomes for victims and their families, by increasing the number of victims receiving support, and by allowing earlier intervention, including the use of protection orders. In the longer term, it was anticipated that the new offence would lead to a reduction in the prevalence of domestic abuse, through better recognition of these behaviours and by the punishment of CCB offences, providing a deterrent to would-be perpetrators and preventing re-offending.

The logic model in Figure 1 has been used to produce the list of research questions below. The review was based on these research questions, with the evidence against each research question assessed in Chapter 5.

- Has there been an increase in understanding and awareness of CCB across the criminal justice system?

- Has there been an increase in understanding and awareness of CCB among the general public?

- Is the new offence being reported to and recorded by the police?

- Are CCB offenders being charged, prosecuted and convicted?

- Has there been an increase in the number of offenders being brought to justice, and an increase in the severity of punishment?

- Has there been an improvement in outcomes for victims of CCB?

- Has there been a reduction in the prevalence of CCB?

3. Analysis of quantitative data

3.1 Introduction

This chapter draws on data relating to the prevalence of controlling or coercive behaviour (CCB), and the criminal justice system (CJS) response to the CCB offence. It presents data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the Home Office, Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

3.2 The prevalence of CCB

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is the main source of evidence for national estimates of domestic abuse prevalence. The CSEW is a large-scale, annual survey that asks members of the public about their experience of victimisation. Questions on domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking appear in a self-completion module, where the respondent answers questions anonymously using a digital device. At present, there is no robust measure of the prevalence of CCB specifically. This report, therefore, draws on the available CSEW evidence on the prevalence of domestic abuse and CCB questions trialled by the ONS in 2017/18 in order to estimate the prevalence and nature of CCB.

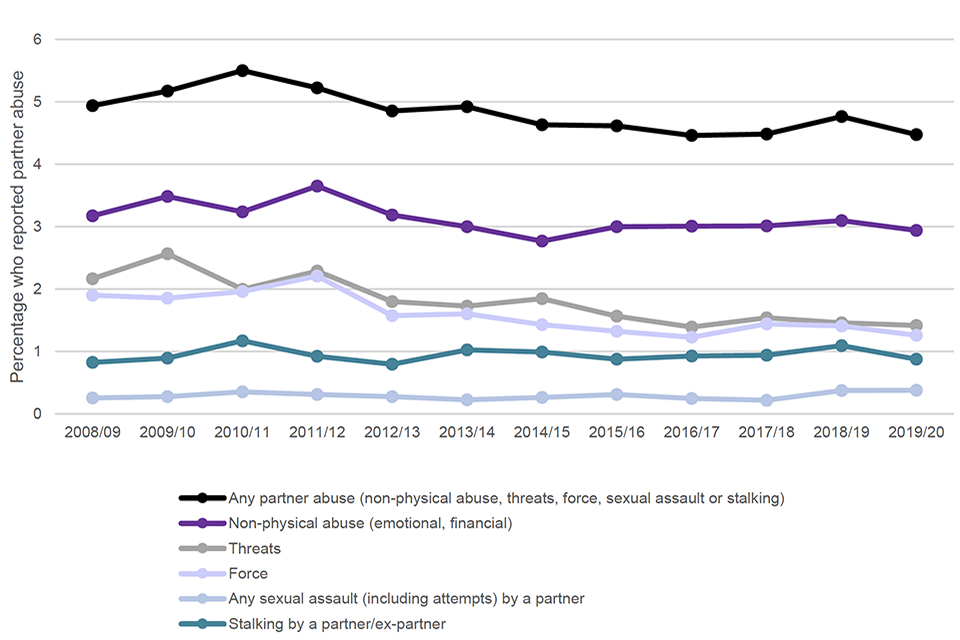

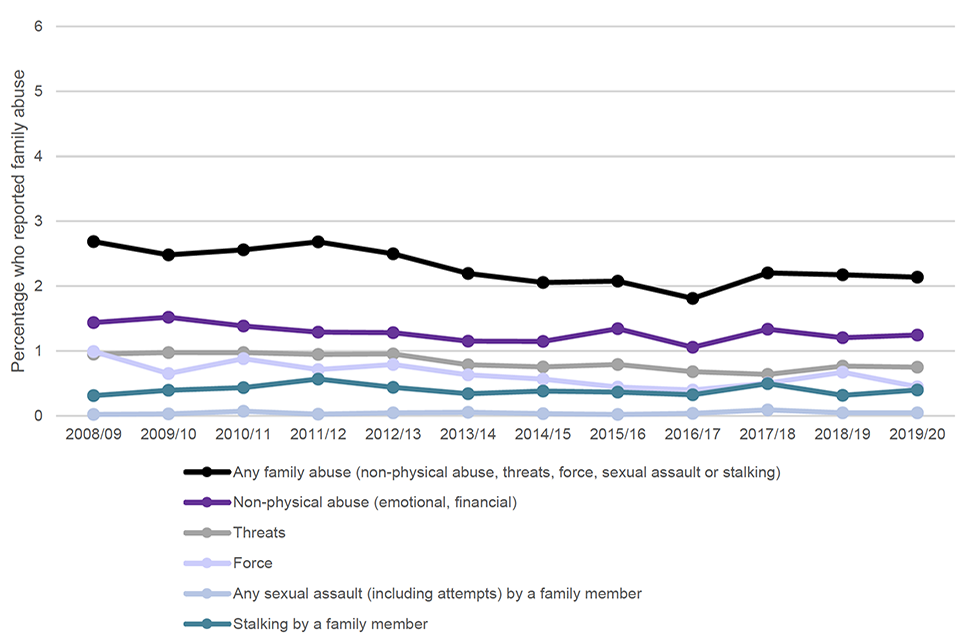

In the 2019/20 survey, 6.1% of adults aged 16 to 59 in England and Wales reported having experienced domestic abuse in the last year, which equates to a total of 2.0 million adults aged 16 to 59 in 2019/20 (ONS, 2020a). This is similar to the previous year when 6.3% (2.1 million) of adults aged 16 to 59 experienced domestic abuse. As in previous years, in the 2019/20 survey women were around twice as likely as men to have reported experiencing domestic abuse (8.1% compared with 4.0%). In addition, as Figures 2 and 3 show, the reported prevalence of partner abuse (abuse carried out by a partner or ex-partner) was higher than that of family abuse (abuse carried out by a family member), and this has consistently been the case over time. In 2019/20, for instance, 4.5% of respondents aged 16 to 59 reported partner abuse, while 2.1% in this age group reported family abuse.

While CCB often includes both physical and non-physical forms of abuse, a key aim of the creation of the offence was to provide a clearer legal framework to capture patterns of non-physical domestic abuse, which were not prosecutable under alternative offences in the same way that forms of physical abuse might be. The CSEW asks respondents several questions to identify types of non-physical abuse, such as whether their partner has:

- isolated them from relatives and friends:

- humiliated or belittled them:

- controlled their access to household money and/or controlled how much they spend:

- monitored their letters, emails or texts; or

- kept track of where the respondent went.

As Figures 2 and 3 show, non-physical abuse is the most prevalent type of domestic abuse reported by respondents. The proportion of those reporting non-physical abuse by a partner has remained at around 3% of adults aged 16 to 59 since 2012/13. The proportion of those reporting non-physical abuse by a family member has remained between 1% and 1.5% since 2008/09.[footnote 9] Force, threats and stalking behaviours were also experienced by victims of both partner abuse and family abuse. Domestic abuse-related sexual assault (including attempts) was less prevalent in family abuse (0.05%), but 0.4% of CSEW respondents reported having experienced it at the hand of a partner in the 2019/20 survey.

Figure 2 – The percentage of 16 to 59 year olds in England and Wales who reported experiencing partner abuse, CSEW, 2008/09 to 2019/20

Source: Office for National Statistics (2020a)

This chart presents data on the number of adults who reported experiencing abuse by a partner, including: non-physical abuse; threats; force; sexual assault; and stalking. The proportion of adults aged 16 to 59 who experienced any form of abuse by a partner has seen a relatively steady decrease from 5.5% in 2010/11 to 4.5% in 2019/20. The most commonly reported type of partner abuse across the time series has been non-physical abuse (3% in 2019/20). Please note that changes between years presented in this graph may not be statistically significant.

Figure 3 - The percentage of 16 to 59 year olds in England and Wales who reported experiencing family abuse, CSEW, 2008/09 to 2019/20

Source: Office for National Statistics (2020a)

This chart presents data on the number of adults who reported experiencing abuse by a family member, including: non-physical abuse; threats; force; sexual assault; and stalking. The proportion of adults aged 16 to 59 who experienced abuse by a family member saw a relatively steady decrease from 2.7% 2008/9 to 1.8% in 2016/17. Since then, there has been a small increase with the level remaining steady around 2.1% between 2017/18 and 2019/20. The most commonly reported type of family abuse across the time series has been non-physical abuse (1.3% in 2019/20). Please note that changes between years presented in this graph may not be statistically significant.

While the CSEW provides estimates of the prevalence of physical and non-physical domestic abuse, it does not fully capture the prevalence of coercive or controlling behaviour. These limitations are described by Myhill (2017: 35): “the self-completion module [includes] additional questions intended to capture financial abuse, isolation from family and friends, emotional abuse and frightening threats [but] lacks specific measures of the most common impacts of coercive control on victims,particularly ongoing anxiety and/or extreme fear, and restricted space for action”.

Myhill’s (2015) analysis of the 2008/09 CSEW found that 6% of men and 30% of women who reported intimate partner violence to the survey experienced what Myhill termed “coercive controlling violence”. Data provided by Citizens Advice, Women’s Aid, and SafeLives on the proportions of domestic violence victims suffering from CCB provides an unclear picture, with estimates varying between around 30% and over 90%. However, caution is advised with interpreting these data, as the definitions of coercive and controlling behaviour used by each organisation differ and some support services often deal with high harm cases of domestic abuse.

In an effort to capture CCB in the CSEW, the ONS trialled a set of questions in 2017/18. The results suggested that in 2017/18, 1.7% of those aged 16 to 59 had experienced CCB by a partner or ex-partner, and 0.6% of those aged 16 to 59 had experienced CCB by a family member. However, the ONS concluded that these questions require further development as “there is uncertainty in whether the measure adequately captures victims of the offence as outlined in the statutory guidance” (ONS, 2019a, p 7). For instance, there was a notable difference between the estimated prevalence of CCB compared with non-physical abuse, and there was a lower overall prevalence of domestic abuse reported by the cohort who answered the CCB specific questions. Nevertheless, these indicative prevalence estimates would suggest that in 2017/18 around 572,000 adults aged 16 to 59 in England and Wales were victims of CCB by a partner or ex-partner, and around 202,000 adults aged 16 to 59 in England and Wales experienced CCB by a family member. Depending on the amount of overlap between victims of partner/ex-partner and family abuse,[footnote 10] the estimated total number of CCB victims aged 16 to 59 in 2017/18 could be between 572,000 and 774,000.

Further details on the above data are provided in Annex 1, alongside other data on the prevalence and characteristics of CCB.

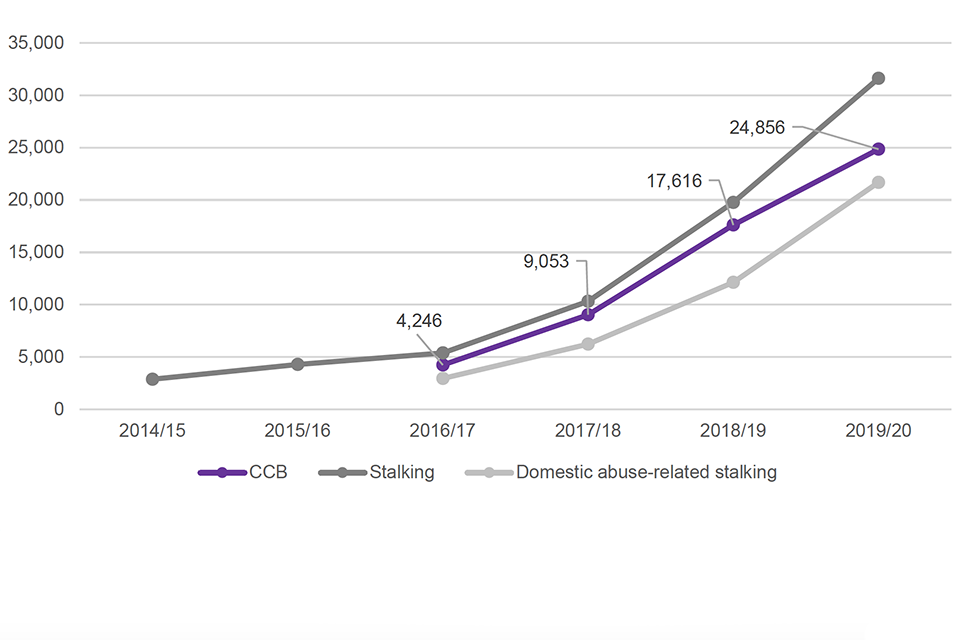

3.3 Police recorded offences

Since the CCB offence came into effect on the 29 December 2015, the volume of offences recorded by the police has increased steadily (ONS, 2020a), as shown in Figure 4. In each year, the majority of recorded CCB offences (93% to 94%) involved female victims.[footnote 11] However, besides victim sex, no other characteristics of the victims or perpetrators/suspects are consistently available to the Home Office for recorded CCB offences. It is therefore not possible to establish what proportion of the offences recorded was intimate partner abuse and what proportion was familial abuse.

Volume of CCB offences recorded

As shown in Figure 4, the number of recorded CCB offences has increased year on year, with the number of recorded offences more than doubling from 4,246 in 2016/17[footnote 12] to 9,053 in 2017/18, and nearly doubling again to 17,616 CCB offences recorded in 2018/19 (ONS, 2017; 2018; 2019b). Numbers continued to increase, albeit by a more moderate 41%, to 24,856 CCB offences being recorded in 2019/20[footnote 13] (ONS, 2020a). The numbers of recorded stalking offences have been similar to the number of CCB offences, and they have followed very similar upward trends over the last four years[footnote 14], [footnote 15], including those which are domestic abuse-related. Around seven in ten recorded stalking offences (69%) in 2019/20 were domestic abuse-related.

Figure 4 - Number of police recorded CCB offences (2016/17 to 2019/20) and stalking offences (2014/15 to 2019/20)1, including the proportion of stalking offences that were domestic abuse-related (2016/17 to 2019/202)

Notes:

- The 2016/17 figure for CCB is based on 38 police forces. All figures for 2019/20 in this figure are based on 42 police forces as they do not include data from Greater Manchester Police.

- This is partly due to a counting rules change, which was effective from 2018/19 and is explained on page 16.

Source: Office for National Statistics (2017; 2018; 2019b; 2020a) and Home Office (2021)

Figure 4 presents the number of CCB and stalking offences recorded by the police including the proportion that were domestic abuse related stalking. Volumes of CCB offences have been increasing steadily each year from 4,246 in 2016/17 to 24,856 in 2019/20. These increases have been similar to those seen in stalking offences and domestic abuse-related stalking offences over the same period.

There are a number of possible reasons for these increases in CCB offences being recorded. Firstly, according to the ONS, increases in recording are “common for new offences and the rise could be attributed to improvements in recognising incidents of coercive control by the police and using the new law accordingly” (ONS, 2019b). In the first year, data on CCB offences were only available from 38 forces, while in the following years data were received from all 43 territorial police forces.

In addition, as the offence was introduced without retrospective effect (Home Office, 2015b), it is likely that the police would have initially encountered difficulties in building strong cases evidencing CCB, as evidence from before 29 December 2015 would not have been admissible.[footnote 16] Particularly in the first few months after the introduction of the offence, it may have been difficult to build sufficient evidence of a repeated pattern of abuse. This may have caused the number of recorded offences to rise over time, as the strength of CCB cases increased.

Further, there was also an increase in the recording of offences flagged as domestic abuse-related[footnote 17] over the same time period, with 758,941 domestic abuse-related crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales in 2019/20[footnote 18], representing a 9% increase from the previous year and a 63% increase from 2016/17 (ONS, 2020a). The ONS suggests this is likely due to improved police recording practices and potentially an increased awareness and willingness to report among the public. Therefore, it is possible that there may have been an increase in the willingness of victims (or other individuals/organisations) to report CCB and domestic abuse more broadly over this period, although there is insufficient evidence on this.

It is likely that one of the key reasons for the increase is a change in the counting rules for recording ‘course of conduct’ offences. Generally, when police officers attend an incident where a victim alleges that they have been subject to several crimes committed against them by the same suspect, the most serious of these will be recorded in the official crime statistics. In many cases where CCB (or stalking) is present, it is likely that there will have been incidents of physical violence as well as non-physical abuse. When the CCB offence was introduced, the recording rules set out that unless any associated physical assault was more serious (i.e. it amounted to at least an offence of grievous bodily harm under section 18 of the Offences Against the Person Act), it was the CCB offence that should be recorded. However, an inspection by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC, now HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services, HMICFRS) indicated that this was proving challenging to manage, and that as a result the true level of CCB was not accurately reflected in the statistics. To seek to improve this, from 2018/19, the recording rules set out that in all cases “where there is a course of conduct (stalking, harassment or controlling or coercive behaviour) in addition to one or more other substantive offences, then both the CCB (or stalking or harassment) and the most serious related offence should be recorded” (Home Office, 2020a).[footnote 19] This change in the counting rules likely had an effect on the number of offences of CCB and stalking offences recorded from 2017/18 to 2018/19, as shown in Figure 4.

It is unlikely that the increase in police recorded CCB offences has been driven by an increase in prevalence of CCB. While CCB prevalence is not currently separately measured by the CSEW, the prevalence of domestic abuse has not changed significantly over this period. The gap between CSEW prevalence estimates for domestic abuse and domestic abuse-related offences being recorded by forces suggests that the majority of domestic abuse does not come to the attention of the police. This is supported by findings from the 2017/18 CSEW, which found that fewer than 1 in 5 of those experiencing domestic abuse (17.3%) reported the abuse to the police (ONS, 2019c). Similarly, CCB is likely to have high levels of under-reporting.

As stated in the previous section, it is estimated that the annual number of victims of CCB may be in the range of 572,000 to 744,000 (although this is subject to considerable uncertainty), and the number of domestic abuse victims aged 16 to 59 in 2019/20 is estimated at around 2 million. The 24,856 CCB offences recorded in 2019/20[footnote 20] are therefore likely to represent only a small fraction of this offending behaviour, with the majority of cases not coming to the attention of the police. Hence, despite the increase in the number of recorded CCB offences each year, it is likely that the majority of CCB is still not being reported to or recorded by the police.

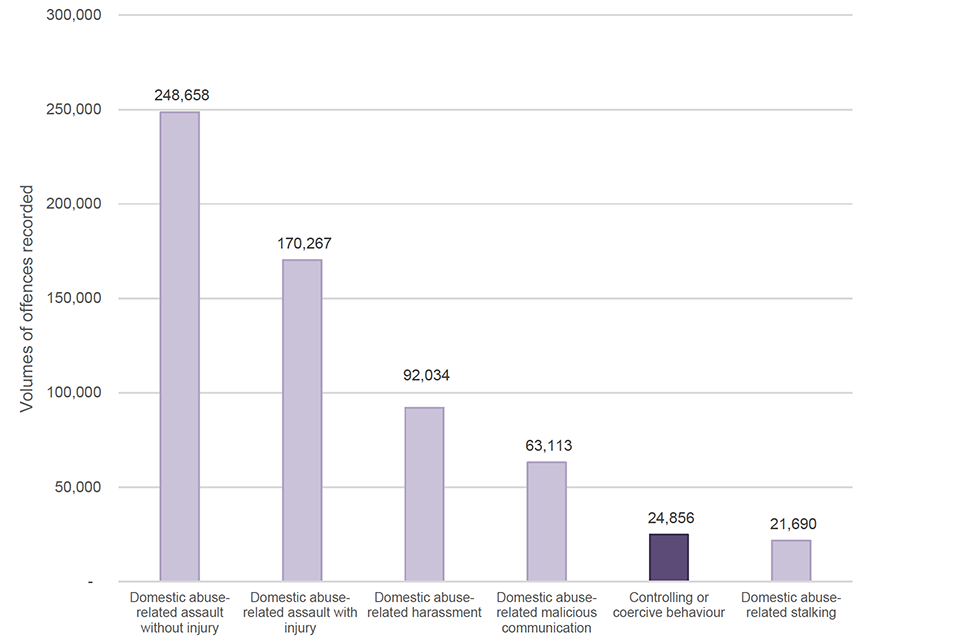

Recorded CCB offences compared with other domestic abuse-related offences

The total number of domestic abuse-related offences recorded by the police in 2019/20 was 758,941[footnote 20], 30 times greater than the total estimated number of CCB offences (ONS, 2020a). The volume of recorded CCB offences is relatively low when compared with other domestic abuse-related offences, as shown in Figure 5, and is only higher than volumes of recorded domestic abuse-related stalking. As ‘course of conduct’ offences, each individual CCB or stalking offence consists of repeated or ongoing patterns of abuse, whereas most other domestic abuse-related offences, by contrast, relate to an individual incident, such as a single assault. In addition, the legislation requires that, for the CCB offence, proof of the serious effect on the victim is provided, which, if not immediately obvious to attending officers, could prevent CCB from recorded. Any comparison between these offence types, and particularly comparisons of volumes, must take into account these differences. In this context, stalking offences (introduced in November 2012) may therefore provide a more suitable comparison to CCB, as they also involve a similar pattern of repeated or ongoing abuse.[footnote 21]

Figure 5 – Number of CCB offences and other selected domestic abuse-related offences recorded by police forces in England and Wales, 2019/201

Notes:

- These figures do not include data from Greater Manchester Police.

Source: Office for National Statistics (2020a) and Home Office internal database

Figure 5 presents data on CCB and selected other domestic abuse-related offences recorded by the police in 2019/20. In 2019/20, 24,856 CCB offences were recorded. Volumes of CCB offences in 2019/20 were considerably smaller compared with other domestic abuse related offences. For example, the volume of domestic abuse-related assault without injury offences was around ten times that of CCB offences, while the volume of domestic abuse-related harassment offences was nearly four times that of CCB offences.

Volumes and crime rates of CCB recorded offences regionally

Across England and Wales, an average of 44 CCB offences were recorded per 100,000 population in 2019/20 (ONS, 2020a).[footnote 22] The regions with the lowest rates of CCB offences were London (16 offences per 100,000 population) and the South West (32 offences per 100,000 population). The highest were East Midlands (75 offences per 100,000 population) and Yorkshire and the Humber (69 offences per 100,000 population).

This variation was even greater at police force level. While the Metropolitan Police recorded the third-highest volume of CCB offences in 2019/20 (1,388 offences), they recorded the lowest rate per population (16 offences per 100,000 population). The highest CCB crime rate of 197 offences per 100,000 population was recorded by Lincolnshire Police, which also recorded the second-highest volume of CCB offences in 2019/20 (1,499 offences).

The reasons for the variation between police force areas are not currently known, but may include differences in recording practices, prevalence, and awareness and willingness of the public to report CCB across force areas. In the absence of robust regional prevalence estimates of coercive control across different areas, it is difficult to establish how much CCB remains unidentified across different areas.

3.4 Police recorded outcomes

At the end of the investigation of an offence, the police assign an outcome. Data on the outcomes of CCB investigations were only available from a subset of forces[footnote 23], and this report therefore focuses on the proportions of outcomes for those forces that provided data, rather than volumes. At the time of writing, 4% of CCB offences recorded in 2019/20 had not yet been assigned an outcome.[footnote 24] This section therefore discusses 2018/19 data, which have a smaller proportion of offences with unassigned outcomes and are thus more appropriate for analysis.

As Table 1 illustrates, in 2018/19 fewer than half (47%) of CCB cases were assigned an outcome within 30 days, and nearly a quarter (24%) of CCB cases took more than 100 days to be assigned an outcome. The length of time to assign outcomes is broadly similar to domestic abuse-flagged stalking offences, but considerably longer than domestic abuse-flagged assault cases, which may be more straight forward and less time-consuming to evidence. The length of time that it takes to assign outcomes can make it difficult to accurately compare recent figures to those from previous years or to compare with other offences, where evidence of only a single event of criminal behaviour was required.

Table 1 – Length of time taken to assign outcomes to CCB and domestic abuse-related offences recorded, 2018/19

| All controlling or coercive behaviour offences | All domestic abuse-flagged offences | Domestic abuse flagged-stalking offences | Domestic abuse-flagged assault with injury offences | Domestic abuse-flagged assault without injury offences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same day to 5 days | 20% | 29% | 15% | 29% | 36% |

| 6 to 30 days | 27% | 31% | 27% | 32% | 33% |

| 31 to 100 days | 29% | 25% | 30% | 26% | 22% |

| More Than 100 Days | 24% | 15% | 28% | 14% | 10% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Notes:

- Data in this table are based on 37 police forces that supplied adequate data.

Source: Home Office internal database; extracted August 2020

As shown in Table 2, in 2018/19 the proportion of CCB offences leading to a charge/summons[footnote 25] was lower (6%)[footnote 26] than that for all domestic abuse-related offences (12%).[footnote 27] Similar to other domestic abuse-related offences, the vast majority of CCB cases were finalised due to ‘evidential difficulties’ (86% compared with 78% for all domestic abuse-related offences).[footnote 28] With the exception of domestic abuse-related stalking, over half of investigations into domestic abuse-related offences were finalised due to evidential difficulties as victims did not support further action. Getting or keeping the victim on board with the investigation can be difficult, particularly in cases of domestic abuse, due to the complexity of the relationship that the victim has with the perpetrator, especially when they want to continue the relationship, have children with them or may be emotionally or financially dependent on them.

Table 2 - Percentage breakdown of police recorded outcomes assigned to selected offences in England and Wales in 2018/191,2,3

| Outcome | CCB offences | All domestic abuse-related offences | Domestic abuse-related stalking offences | Domestic abuse-related assault with injury offences | Domestic abuse-related assault without injury offences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charged/Summonsed | 6% | 12% | 17% | 16% | 7% |

| Out-of-court (formal and informal)4 | 0% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 3% |

| Evidential difficulties (suspect identified; victim supports action) | 35% | 24% | 33% | 23% | 20% |

| Evidential difficulties (victim does not support action)5 | 51% | 54% | 40% | 52% | 63% |

| Investigation complete - no suspect identified | 1% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Other6 | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 5% |

| Total offences assigned an outcome | 98% | 99% | 98% | 99% | 99% |

| Offences not yet assigned an outcome | 2% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Total offences | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

- Data in this table are based on 37 police forces that supplied adequate data.

- Percentages based on number of outcomes assigned to offences recorded in the year ending March 2019 divided by number of offences; due to rounding, the percentages reported per category may not always add up to the column totals.

- Includes caution - adults; caution - youths; Penalty Notices for Disorder; cannabis/khat warnings; and community resolutions.

- Includes evidential difficulties where the suspect was/was not identified, and the victim does not support further action.

- “Other” outcomes include taken into consideration; prosecution prevented or not in the public interest; action undertaken by another body/agency; and further investigation to support formal action not in the public interest.

Source: Home Office internal database; extracted January 2021

In 35% of CCB offences in 2018/19, it was concluded that, despite the victim supporting further action being taken, sufficient evidence could not be collected to charge the suspect. This proportion was higher in comparison with that for all domestic abuse-related offences (24%) but similar to that for domestic abuse-related stalking (33%). This islikely to reflect that proving patterns of abusive behaviours, which sometimes requires evidence of less recent instances as well as evidence of non-physical abuse, can be harder (and more time-consuming) than collecting proof of, for instance, a violent incident that the police attended and were able to document[footnote 29]. Where physical evidence is more difficult to attain, the case may rely more heavily on evidence provided by the victim, making it very difficult to prosecute without the victim’s sustained engagement in the process. This appears to be substantiated by the low charge/summons rate for domestic abuse-related assault without injury offences (7%) where almost two thirds of victims do not support further action (63%), when compared to the charge rate for assault with injury (16%).

In addition, the requirement for proof of the ‘serious effect’ that the controlling or coercive behaviours have had on the victim likely creates further difficulties in gathering and providing the necessary evidence for the CCB offence. The proportion of offences being dealt with using out-of-court disposals was lower for CCB than for other domestic abuse-related offences (close to 0% compared with 3% for all domestic abuse-related offences in 2018/19). This is perhaps not surprising, given that out-of-court disposals are predominantly used for low-level offences or first-time offending. Since the definition of CCB requires that the behaviour of the perpetrator has had a ‘serious effect’ on the victim’s ability to feel safe or go about their day to day activities, out-of-court disposals are usually not appropriate in cases of CCB.

3.5 Prosecutions, convictions and sentences

Both the CPS and the MoJ collect data on prosecutions, convictions and sentencing outcomes. CPS data show that the number of CCB offences that reached a first hearing at a magistrates’ court has increased year on year. This increase was particularly pronounced in the first years after the introduction of the offence, from 2016/17- the first year in which CCB cases reached this stage of the CJS - to 2017/18, for instance, numbers increased threefold from 309 to 960. The number increased by a further 26% to 1,208 prosecutions in 2019/20 (ONS, 2020a). Again, the small number of cases reaching the court stage in 2016/17 is not surprising considering the non-retrospective nature of the offence,[footnote 30] the relatively low charge rate and the time that it takes to investigate cases of CCB. Consequently, the increase in the years that followed also is unsurprising as more offences were recorded, investigated and charged and thus progressed through the CJS.

Data are not available from the CPS on the pre-charge decisions, charges by the CPS or prosecution outcomes broken down by specific offence. The following section, therefore, focuses on data published by the MoJ (2020a),[footnote 31] where more detailed breakdowns are available.

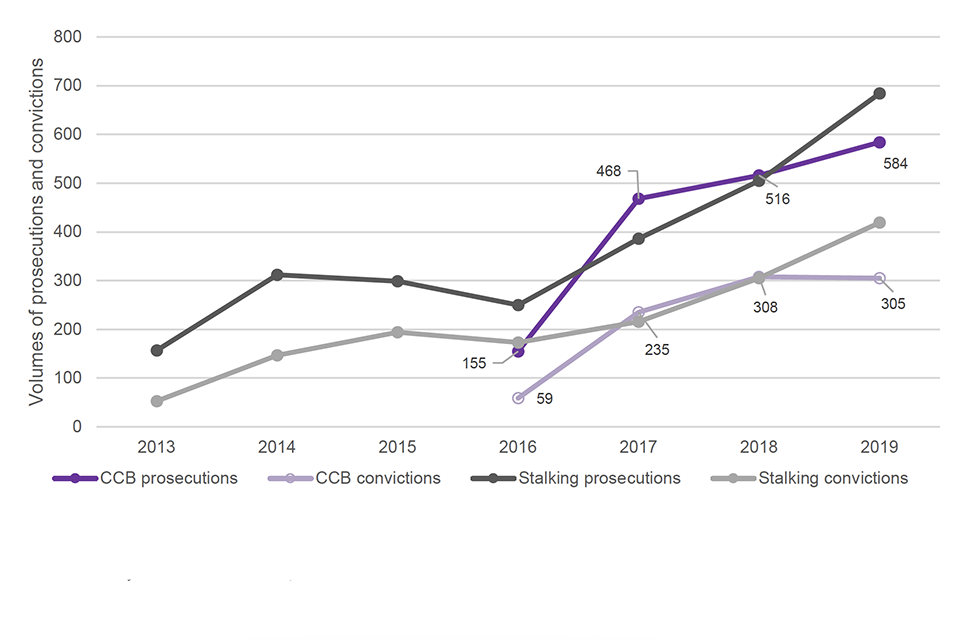

Volumes and conviction rates

The volume of prosecutions and convictions for cases where CCB was the principal offence[footnote 32] increased between 2016 to 2019, which was likely driven by the increase in police recorded offences that resulted in a charge over this period. As shown in Figure 6, the number of prosecutions where CCB was the principal offence increased threefold from 155 in 2016 to 468 in 2017, but the rate of increase slowed to 25% over the following two years to 584 in 2019.

Figure 6 – Prosecutions and convictions for CCB and stalking as principal offence in England and Wales, 2013 to 20191

Notes:

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020a)

This chart shows the number of prosecutions and convictions for CCB between 2016 and 2019, and stalking offences between 2013 and 2019. Volumes of prosecutions where CCB was the principal offence increased threefold from 155 in 2016 to 468 in 2017, but the rate of increase slowed over the following two years with volumes rising to 584 in 2019. Volumes of convictions where CCB was the principal offence increased from 59 in 2016 to 308 in 2018 and 305 in 2019. Following a fall between 2014 and 2016, the volume of stalking prosecutions increased year on year between 2016 and 2019. The volume of stalking convictions also increased year on year, aside from a small dip in 2016.

A comparison with other domestic abuse-related offences is not available, as it is not currently possible to identify which offences are specifically related to domestic abuse in the prosecution and sentencing data. However, as previously identified, stalking offences may provide a useful comparison to CCB, given their similar nature as a course of conduct offence and their relatively recent introduction[footnote 33]. In the first full year after stalking offences were introduced in 2013, there were 157 prosecutions and 53 convictions, very similar to the volumes for CCB in its first year (155 and 59 respectively in 2016). It should be noted that as it is not possible to identify domestic abuse-related cases, these figures will capture some stalking cases that are not related to domestic abuse (such as stranger stalking).

However, the increase in volumes of CCB prosecutions and convictions in its second and third year after coming into effect was steeper than that for stalking offences in the subsequent years after its introduction. While volumes of CCB and stalking prosecutions continued to increase in 2019, the increase was more pronounced for stalking offences, and while convictions for stalking also increased, the number of CCB convictions decreased from 308 to 305.

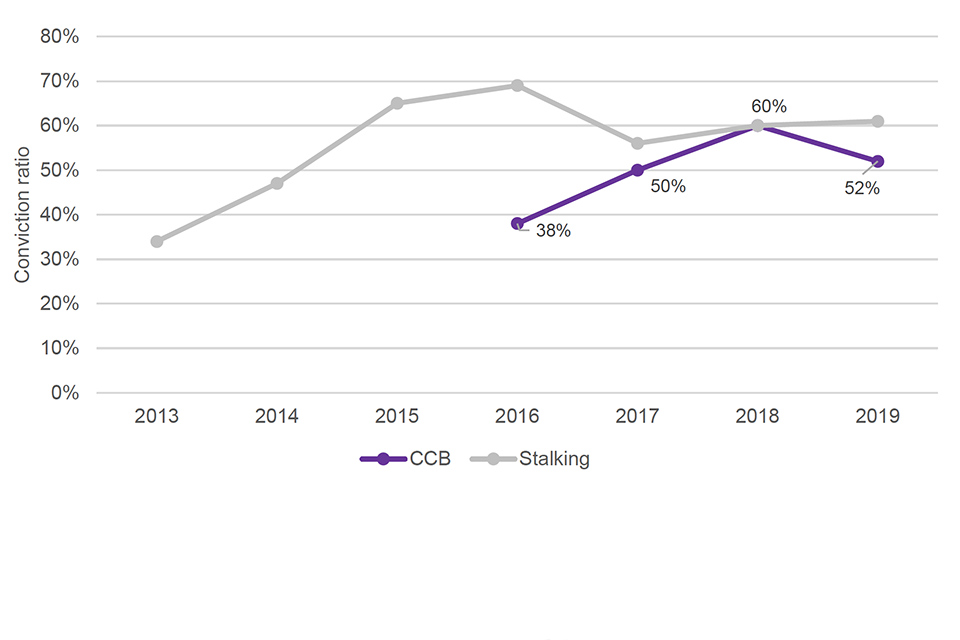

As shown in Figure 7, the conviction ratio in cases where CCB was the principal offence prosecuted initially increased, from 38% in 2016 to 50% in 2017 and 60% in 2018, but more recently it dropped to 52% in 2019. The conviction ratio for stalking offences broadly followed a similar trend after it was introduced, increasing steadily from 34% in 2013 to 65% in 2015 and has since fluctuated but remains above 55%. The conviction ratio is calculated as the number of convictions in a given year divided by the number of proceedings in a given year. It is therefore affected by the time it takes for court cases to reach the conviction stage – in particular, this would affect the ratio in the first year after introduction as some of the prosecutions recorded in the first year will only reach conviction in the subsequent year.

Figure 7 - Conviction ratios for prosecutions of CCB offences (2016 to 2019) and stalking offences (2013 to 2019)1, where charged as principal offence only

Notes:

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020a)

This chart outlines the proportion of CCB and stalking prosecutions resulting in a conviction. The conviction ratio in cases where CCB was the principal offence prosecuted increased from 38% in 2016 to 50% in 2017 and 60% in 2018, before dropping to 52% in 2019. The conviction ratio in cases where stalking was the principal offence increased between 2013 and 2016 before dropping in 2017. There has been a slight increase in the conviction ratio for stalking offences in 2018 and 2019, at around 60% of cases prosecuted.

The conviction ratio for violence against the person offences was higher than CCB, at 75% in 2019. The lower conviction ratio for CCB (and stalking) prosecutions is again likely due to the inherent difficulties in evidencing complex patterns of abuse, particularly where there are no signs of physical violence.

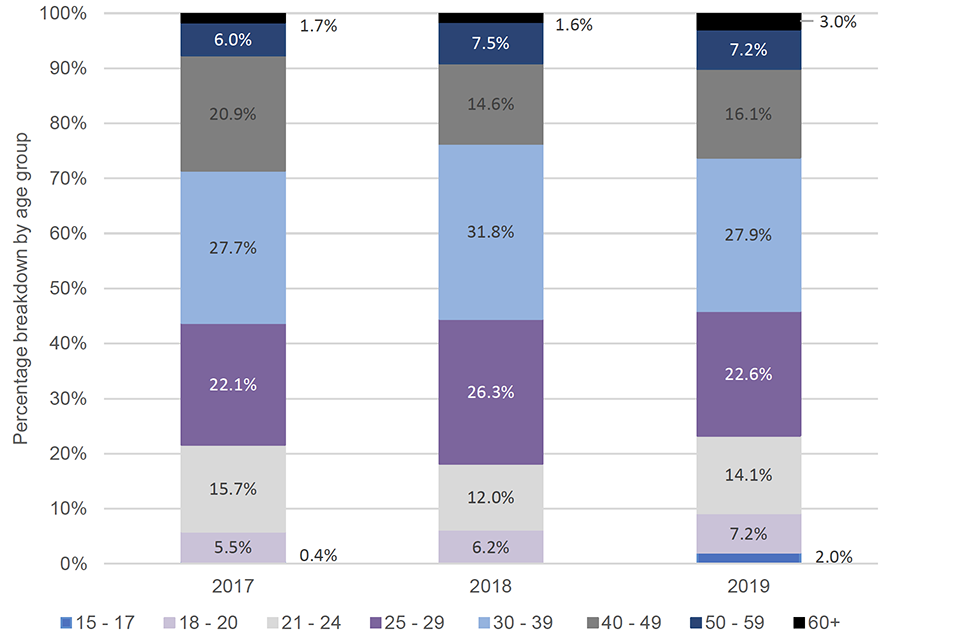

Characteristics of convicted defendants

Caution is advised when interpreting data on the characteristics of defendants convicted for CCB, given that the volume of convictions isrelatively small. The vast majority of defendants convicted for CCB as the principal offence were male[footnote 34]. This was fairly consistent between 2016 and 2019, ranging between 97% and 99% (MoJ, 2020a).

As shown in Figure 8, most of the defendants convicted of CCB from 2017 to 2019 were aged 21 or above (above 90% in all three years), while around 6% or 7% of defendants were aged between 18 and 20. The proportion of juvenile defendants (aged between 10 and 17) prosecuted for CCB was small, making up no more than 2% of defendants in any year. In terms of convictions, 1 juvenile defendant was convicted of CCB in 2017, but in 2019, 6 juvenile defendants (2%) were convicted of CCB.

Figure 8 – Age breakdown of defendants convicted of CCB as principal offence in England and Wales, 2017 to 20191,2,3

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

- This detailed age breakdown was not available for 2016.

- There were no defendants whose age was recorded as unknown.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020a)

Figure 8 presents the age breakdown of defendants convicted of CCB as a principal offence for the years 2017 to 2019. More than 90% of the defendants convicted of CCB from 2017 to 2019 were aged 21 or above. The largest proportion each year were those aged 30 to 39, representing over a quarter of defendants in each year. The proportion of defendants aged 18 to 20 was around 6% or 7%. In 2019, 2% of defendants convicted of CCB were juvenile (aged 10 to 17).

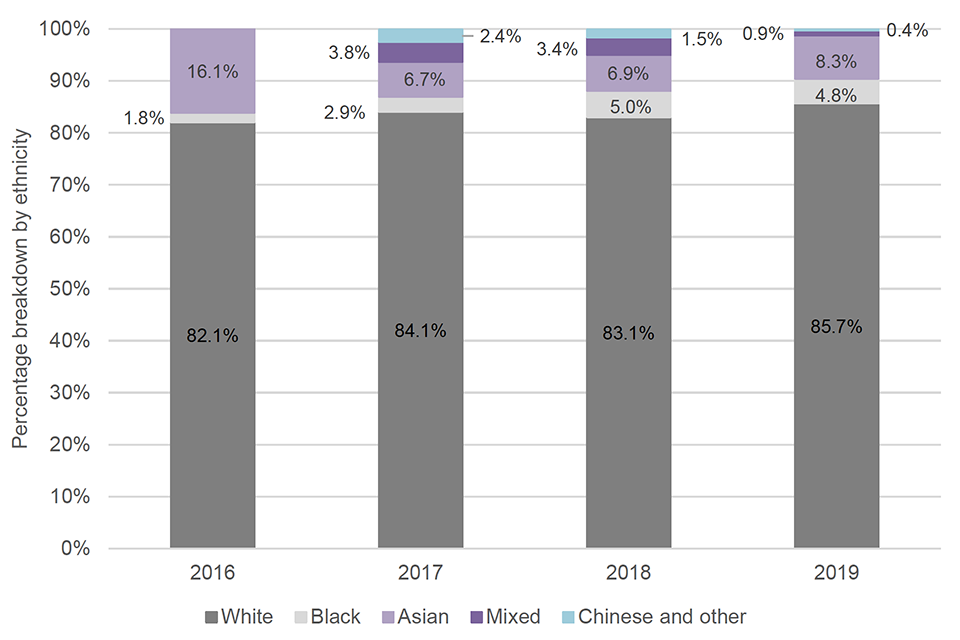

As shown in Figure 9, over 80% of defendants convicted of CCB offences each year were White (ranging from 82% in 2016 to 86% in 2019).[footnote 35] The proportion of defendants convicted of CCB offences whose ethnicity was Asian decreased from 16% in 2016 to 8% in 2019, while the proportion of defendants convicted of CCB whose ethnicity was Black increased from 2% in 2016 to around 5% in 2018 and 2019 (MoJ, 2020a). However, as the vast majority of defendants in all four years shown were White, percentage changes among Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) defendants are based on very small numbers and caution is advised when interpreting them.

Figure 9 - Ethnicity breakdown of defendants convicted of CCB as principal offence in England and Wales, 2016 to 20191,2

Notes:

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

- All proportions are based on calculations with the category of ‘ethnicity not stated’ excluded.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020a)

Figure 9 presents the ethnicity breakdown of defendants convicted of CCB as a principal offence. From 2016 to 2019, over 80% of defendants convicted of CCB offences each year were White.

3.6 Prosecutions as a non-principal offence

Defendants may be prosecuted for more than one offence. In such cases, the most serious offence with which the defendant is charged at the time of finalisation is referred to as the principal offence, while any further offence is referred to as a non-principal offence. Experimental statistics[footnote 36] are available for 2017 to 2019 on the number of prosecutions and convictions involving CCB as a non-principal offence (MoJ, 2020b).

As shown in Table 3, the volumes of prosecutions for CCB as a non-principal offence were similar to the volumes of prosecutions for CCB as the principal offence in most years for which data are available. The number of total CCB prosecutions increased by 22% from 2017 (when there were 911 prosecutions) to 1,112 prosecutions in 2019.

Table 3 – Statistics on numbers of prosecutions for CCB as principal offence and non-principal1, 2017 to 20192

| CCB charged as… | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal offence | 468 | 516 | 584 |

| Non-principal offence | 443 | 429 | 528 |

| Total CCB prosecutions | 911 | 945 | 1,112 |

Notes:

- For an explanation of the various caveats around these experimental statistics, please consult the source, which is available at ‘Guide to Experimental Statistics’.

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020b)

Further experimental statistics published by the MoJ explore the combinations of offences for which defendants are prosecuted (MoJ, 2020c). In 2018, half of the defendants who were prosecuted for CCB (either as the principal or non-principal offence) were also prosecutedfor common assault and battery (50% in 2018 compared with 43% in 2019).[footnote 37] Other offences that defendants were frequently prosecuted for alongside CCB were assault occasioning actual bodily harm (22% in 2018 and 27% in 2019), criminal or malicious damage (17% in 2018 and 18% in 2019) and a number of different sexual offences (for example, rape of a female aged 16 or over – 6% in 2018 and 5% in 2019).[footnote 38] This suggests that where there are specific incidents of physical violence, damage or sexual assaults these tend to be charged as a distinct offence alongside CCB, instead of as part of the pattern of controlling or coercive behaviours. These data could indicate that it may be easier to prosecute CCB offences when they are charged alongside other offences that are less difficult to evidence, such as assault or criminal damage.[footnote 39] Other explanations could include a preference within the CJS to charge and prosecute offences separately, perhaps to not limit the maximum length of custodial sentences (as CCB has a maximum custodial sentence of five years), or a lack of understanding among the CJS that these other crimes could be charged and prosecuted as part of CCB. There is insufficient evidence to confidently assess what is driving the current practice.

3.7 Custodial sentences

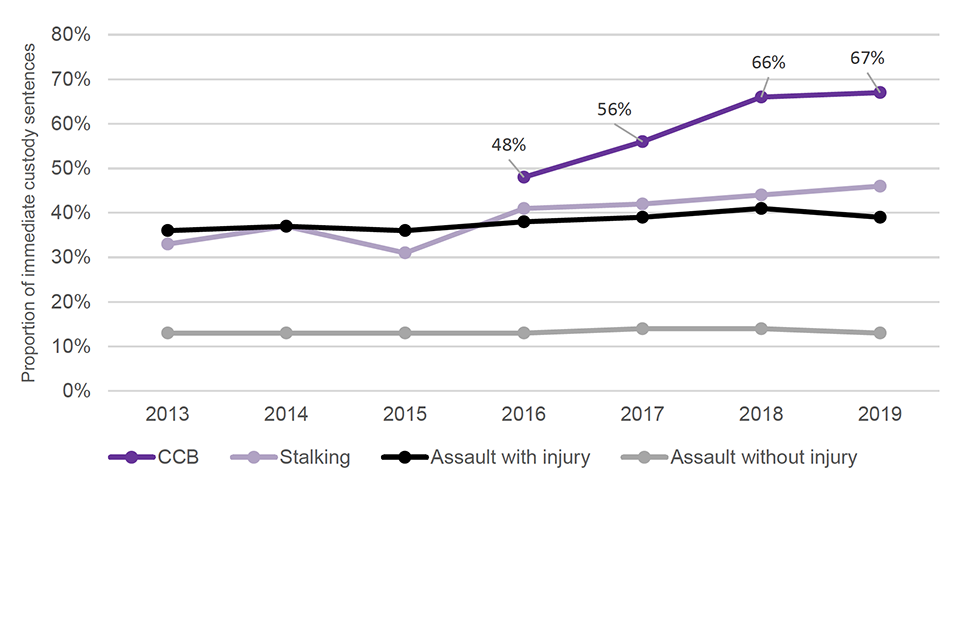

As shown in Figure 10, the proportion of immediate custodial sentences given in cases where CCB was the principal offence has increased from 48% in 2016 to 67% in 2019 (MoJ, 2020a), and has remained higher than for other commonly domestic abuse-related offences. The proportion of immediate custodial sentences given in cases of stalking as the principal offence is lower but has also increased since it was introduced, albeit at a slower rate.

Over the same time period, the proportion of immediate custodial sentences given for single incident crimes like assault with injury has followed a similar pattern to those for stalking, increasing from 36% in 2013 to 41% in 2018, but then falling slightly to 39% in 2019. The proportion of immediate custodial sentences where assault without injury was the principal offence has remained considerably lower (around 13%) compared with CCB (between 48% and 67%) across the period (Figure 10).

Figure 10 – Proportion of immediate custodysentences given for CCB, stalking, assault without injury1 and assault with injury offences2 in England and Wales, 2016 to 20193, where charged as principal offences only

Notes:

- Figures for assault without injury are based on MoJ offence code 105 (Common assault and battery).

- Figures for assault with injury are based on MoJ offence codes 8.01 (Assault occasioning actual bodily harm), 8.04 (Other assault with injury – indictable) and 8.05 (Other assault with injury – triable either way).

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020a)

Figure 10 presents data on immediate custodial sentences given for CCB, stalking and assault with and without injury offences. The proportion of immediate custodial sentences given in cases where CCB was the principal offence has increased from 48% in 2016 to 67% in 2019, and in each year since 2016 has been higher than the proportion of immediate custodial sentences given in cases where stalking, assault with injury or assault without injury was charged as principal offence.

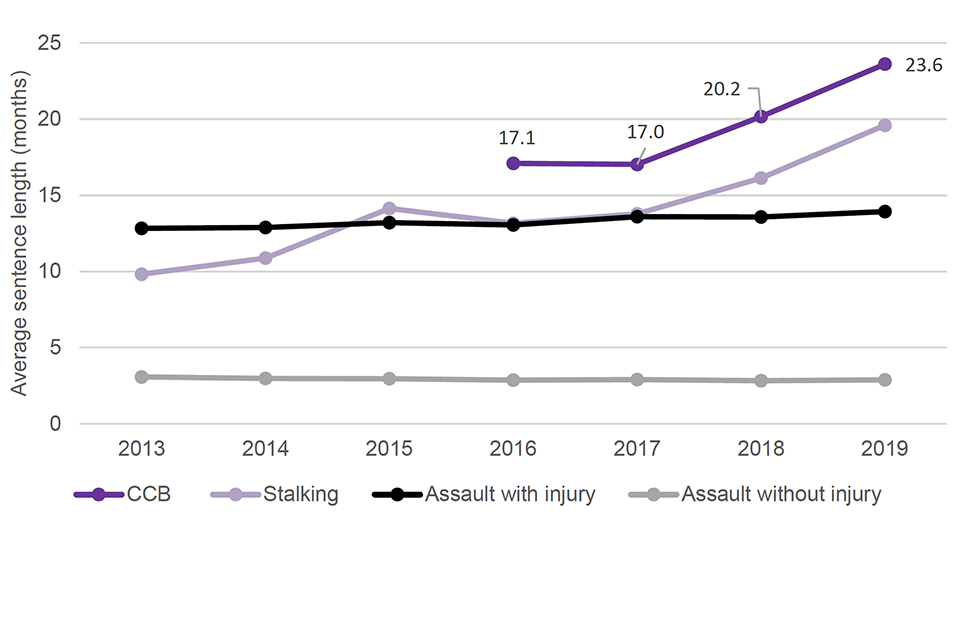

Similarly, despite CCB having a lower maximum sentence length (five years) compared with stalking (ten years since 2017/18)[footnote 40], the average length of custodial sentences has consistently been longer for CCB offences than for stalking, assault without injury, and assault with injury since its introduction (as shown in Figure 11). Both CCB and stalking offences have seen steep increases (39% for CCB, and 42% for stalking) in the average custodial sentence since 2017. In the case of stalking this is likely, at least in part, due to the increase in the maximum sentence for stalking from five to ten years in April 2017. The average sentence length for CCB has consistently been longer than that given in cases of single incident offences, which feature highly among domestic abuse-related offences. For instance, the average sentence length for CCB has consistently been longer compared with assault with injury (which has been relatively steady at around 13 months from 2013 to 2019), and it has been considerably longer than the average sentence length for assault without injury, which has steadily been at around 3 months from 2013 to 2019 (Figure 11).

Figure 11 - Average sentence lengths (in months) for controlling or coercive behaviour offence sentences (2016 to 20191) and stalking2, assault with injury3 and assault without injury4 offence sentences5 (2013 to 2019), where charged as principal offences only

Notes:

- MoJ data are published in calendar years.

- Please note that the average sentence length for stalking in 2019 was revised after publication – please consult the ‘known issues’ section of the MoJ’s ‘Outcome by offence 2009 to 2019’ data table for the revised figure of 19.6 months.

- Figures for assault with injury are based on MoJ offence codes 8.01 (Assault occasioning actual bodily harm), 8.04 (Other assault with injury - indictable) and 8.05 (Other assault with injury - triable either way).

- Figures for assault without injury are based on MoJ offence code 105 (Common assault and battery).

- Data are not available on sentence lengths for cases of stalking and assault and battery that are related to domestic abuse specifically but, seeing as in 2018/19, 35% of violence against the person offences and two-thirds of stalking offences were domestic abuse-related, they are a meaningful point of comparison.

Source: Ministry of Justice (2020a)

This chart outlines the average custodial sentence length given for CCB, stalking and assault with and without injury offences. The average length of custodial sentences for CCB offences has increased from 17.1 months in 2016 to 23.6 months in 2019, and it has consistently been longer than the average custodial sentence length for stalking offences, assault without injury offences, and assault with injury offences.

The higher proportion of immediate custody and relatively long sentence length for CCB compared with some other commonly domestic abuse-related offences may indicate that the courts recognise the severity and long-lasting harms that result from CCB and that the police and the CPS are becoming more proficient in building strong cases for prosecution. However, it could be that (due to a potentially quite high evidential threshold needed to prove evidence of repeated or ongoing abusive behaviours and their ‘serious effect’ on the victim) only the most serious CCB offences reach court and lead to a conviction. There was some difference in average sentence lengths by defendant demographics like age.[footnote 41] In the years for which data are available, the average sentence lengths increased across most age groups. The age group with the longest average sentence length in 2019 were those aged 25 to 29 (25.2 months), followed by those aged 55 to 59 (24.2 months). The latter group showed a considerable increase in average sentence length – from 15 months in 2018 to 24 months in 2019.

4. Rapid literature review

4.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines the findings of a rapid literature review. This review has sought to focus on the most significant and relevant pieces of research relating to controlling or coercive behaviour (CCB) and the impact of the new CCB offence. This chapter should therefore be seen as an overview of the key literature and does not constitute a systematic review of all available evidence. The specific studies which have been considered in this literature review are listed in Annex 5.

It should be noted that owing to the newness of the CCB offence, the literature in this area is limited and much of the available literature consists of theoretical assessment rather than empirical research.

The rapid review also assessed the evidence on the nature of CCB and the impacts of international legislation around CCB, both of which are presented in Annex 3.

4.2 Summary of key themes

Generally, academics writing on CCB have been positive about the criminalisation of coercive control. Writing several years before the offence came into law, Stark (2012, p 213) stated that: “reframing domestic violence as coercive control changes everything about how law enforcement responds to partner abuse, from the underlying principlesguiding police and legal intervention, including arrest, to how suspects are questioned, evidence is gathered, resources are rationed”. Similarly, Wiener (2017, p 501) states that the CCB offence “has the potential to change the way that criminal justice agencies deal with intimate partner abuse for the better”.

Wiener (p 501) also recognises the long-term benefits of the CCB offence:

Further down the line, s. 76 allows the critical notion of coercion into the courtroom and thus encourages survivors to reframe their stories of abuse in a way that more accurately portrays both the wrong of the abuse and the harms that they have experienced as a result. This could, in turn, allow for less attrition in the form of more successful prosecutions, and more appropriate sentencing in intimate partner abuse cases.

Stark and Hester (2019) also anticipated that the coercive control offence (and the Scottish Domestic Abuse offence) could help to improve partnership working between the criminal justice system (CJS), the community and the third sector, and strengthen the support they are able to offer victims:

Giving justice professionals a robust legal tool could relieve their frustration with ‘failed’ intervention, help shift their attention from victim safety to offender accountability, and so remove an important context for victim- blaming. The new law would also facilitate a corresponding shift among community-based services from ‘safety work’ to ‘empowerment’. Incorporating women’s experiential definitions of abuse into criminal law would also broaden the perceived legitimacy of legal remedies, particularly among groups who lacked access to resources or other alternatives. Conversely, the extent to which the new offense echoes the range of issues advocates/specialists are already addressing creates an important basis for linkage between statutory and voluntary sectors. (p 85.)

However, Hamilton (2019) expressed concern that the offence may lead to ‘overcriminalisation’ of social policy, highlighting that it could represent the state interfering in intimate relationships, where power dynamics develop and evolve in different ways.

A number of other issues have been raised about the current legislation and its implementation by the CJS, both within the theoretical literature, and through research conducted since the introduction of CCB. These include:

- challenges for the police in recognising and recording CCB due to its nature as a course of conduct offence rather than an ‘incident’;

- the potential for victims being excluded from seeking justice through CCB legislation due to their relationship and or co-habiting status with the abuser; and

- the challenge in evidencing and prosecuting CCB, where physical evidence is more limited, and victims may be less likely to support prosecution due to the ongoing control they are under.

Difficulty in police recognising and recording CCB

Barlow et al. (2019) argue that the ‘promise’ of the legislation can be seen in the characteristics of crimes labelled as ‘coercive control crimes’ in their research:

The coercive control legislation permits the criminalization of […] certain behaviours which would not previously have been offences prior to its introduction. For example, some 37 per cent of the coercive control crimes examined in our available sample did not include reports of physical violence […] These findings do point to the potential of the coercive control offence in providing means through which police officers may robustly respond to sustained domestic abuse in instances where they might not have been prompted or able to previously. (p 174.)

However, despite this new power, some have argued the offence is not being used to its full potential. Barlow et al. (ibid.) investigated the translation of the offence into practice in one police force area in England. They conducted a quantitative analysis of the outcomes of coercive control offences, compared with other offences in the police force area that were given a ‘domestic abuse’ flag in the same period. They noted the particularly low number of coercive control crimes recorded by the police force they studied, which they suggest shows that the offence is being both underused and under-recorded by the force. This is further evidenced by their examination of actual bodily harm(ABH) offences, which found missed opportunities for using the CCB offence in almost nine out of ten intimate partner cases.

Across the 46 case files Barlow et al. analysed, there was evidence of coercive control identifiable through victim witness statements and previous occurrence records detailing repeat victimisation. Examples of such controlling or coercive behaviours were the “use of digital surveillance technologies, sustained verbal threats and abuse, including so-called ‘revenge porn’ threats, practices of isolation and deprivation and economic abuse” (p 169). However, these had not been identified as CCB by police officers during investigations. For instance, one case involved a woman reporting that her partner had assaulted her by pushing her over and stamping on her, which was recorded as ABH. The woman is recorded as describing to officers that she also experienced other forms of sustained abuse from her partner involving a range of coercive and controlling behaviours. Barlow et al. (ibid.) argue that examples such as this suggest that police officers may be missing key opportunities for identifying patterned abuse.

The literature offers a number of explanations for why such opportunities to record CCB may be being missed. Several months before the offence came into force, Brennan et al. (2018, p 18) interviewed social workers, police officers and specialist domestic abuse practitioners about their perceived ability and organisational readiness to respond effectively to incidents of CCB. One interviewee remarked, “I think there is a lack of understanding around the whole coercive control stuff… a lot of [first response officers] just don’t get it. They really don’t get it. I think they just think, well, there’s no visible injury, and there’s no … it’s a verbal argument, what’s the problem?”

Brennan et al. suggest that this lack of understanding may be further compounded by a lack of definitional clarity around non-physical domestic abuse, which they argue can increase the use of discretion by these frontline services. Similarly, Hamilton (2019, p 212) remarks that because the offence is not ‘precisely demarcated’, it leaves it “to the arbitrary discretion of individual police officers, thus yielding potentially unequal and unfair enforcement”. Brennan et al. (2018) argue that this level of discretion could increase the discounting of coercive control by pressured frontline officers.

Wiener (2017, p 503) suggests that this lack of clarity may be due to the police historically responding to domestic abuse within the ‘violent incident model’ outlined by Stark (2012). Based on her interviews with police, she notes that physical violent incidents appear easier for the police to recognise as criminal and therefore to respond to; they are seen as ‘black and white’, while coercive control, as is seen as ‘murky’. This is likely a deep rooted problem, as Hoyle’s (1998) research published over 20 years ago found the police response to domestic violence to be “largely incident-focused and concerned with physical violence and injury; information relating to the history of the case did not affect the decision to arrest in the absence of evidence of harm at the current incident, and physical assaults with injury providedofficers with the strongest evidence that an offence had taken place” (cited in Myhill, 2019, p 55).

This view is prevalent within the literature, with several academics arguing that for the police to fully embrace the use of the coercivecontrol offence a change of mindset is needed, from one focused on specific incidents of physical violence, towards one that looks for more complex patterns of abuse. Medina Ariza et al. (2016, p 345) comment that: “it would appear from on-going research though that the ‘narrative’ around risk in forces remains largely one of physicalviolence, and that despite there being scope to do so, many frontline officers do not provide sufficient context when completing risk assessments to illuminate coercive control”.

The notion that physical violence is viewed as higher risk by the police is well demonstrated by Barlow et al.’s (2019) analysis, which found that ABH cases flagged as ‘domestic abuse’ were 16% more likely than CCB cases to be assessed as high risk and 20% more likely to result in an arrest and be charged. This, they argue, may suggest that police officers were not taking CCB cases as seriously as offences such as ABH.

These examples, which suggest that CCB is viewed as less serious in comparison to physical abuse, highlight that CCB is generally viewed as separate to physical abuse, rather than encompassing it. McGorrery and McMahon (2019) examined media reports of 107 cases in which people had been charged with and/or convicted of the CCB offence in England and Wales up to April 2018. Based on these, they argue that there is a need to reconcile an apparent overlap between CCB, and traditional assault and threat offences. They state that while in some cases defendants have been charged with specific offences (like, for example, assault or rape) separate from the offence of CCB, in other cases the physical or sexual violence was considered as part of the behaviours constituting the ‘course of conduct’ of CCB.

Of the 107 cases reported in the media in which an offender was convicted of CCB, in 47 cases they were also sentenced for physical or sexual violence offences against the victim, which occurred during the period of CCB. McGorrery and McMahon (ibid.) argue that this illustrates that both clarification and education may be required about the circumstances in which an assault or threat should be charged separately, and the circumstances in which those behaviours should be part of the course of conduct underlying a charge of CCB. They also make the point that if the violence is charged separately, then the prohibition on double punishment would prevent important contextual matters from being taken into account when sentencing the CCB offence, and as such, it may be preferable for all abusive behaviours to be charged as part of the CCB offence.

Evidencing coercive control

In addition to the challenges faced by the police in recognising CCB and recording it appropriately, evidencing CCB is also cited across the literature as particularly challenging compared with other domestic abuse-related offences.

Freedom of Information requests carried out by McClenaghan and Boutard (2017) revealed what they refer to as ‘patchy’ implementation of the Section 76 offence nationwide. Out of the 29 police forces that provided data, there was a total of 532 charges during the first year and a half since the introduction of the CCB offence, but 6 forces had brought 5 charges or fewer. They add that the police force contacts they liaised with described charges as “hard to achieve” and CCB offending as “challenging to prove”.

This was further apparent in Barlow et al.’s (2019) qualitative analysis of police case files, which highlighted that evidencing coercive control was particularly problematic for police officers:

One case involved a woman contacting the police to report an attempted assault on her by her male partner. When the police spoke to the woman, she reported various examples of coercive control, including isolation and economic abuse. Moreover, she was a repeat victim of domestic abuse according to the [police] information management system. This case was recorded as coercive control. However, the ensuing investigation focused on the assault and gathering evidence for this particular ‘incident’ rather than investigating any pattern of abusive behaviour. Officers focused on gathering ‘photographic evidence’ of the assault […] with many of the woman’s descriptions of coercive control being disregarded as examples of ‘one word against the other’, and thus ‘weak’ or ‘unverifiable’.

This suggests that, even where CCB has been recognised and recorded, investigating this offence may not be prioritised due to the difficulty in collecting evidence. This point is supported by Wiener’s (2017) qualitative research with police officers after the CCB offence was introduced, which identified challenges that the police face in taking statements related to coercive control. One participant pointed out:

I think the challenge for first responders is you are not asking them to take a statement about an event. So, if it’s an assault, or a criminal damage [case], there’s an event. Whereas obviously with coercive control you are telling a narrative, a story – that’s always going to be much more difficult.” (Focus group police participant, ibid., p 505.)

Barlow et al.’s (2019) study further states that the police failed to capitalise on a range of available evidential opportunities during their investigations. These included officers not fully investigating evidence of coercive control disclosed in victim witness statements, failure to seek third party witness statements (for example from friends, familyand professionals), and failing to effectively capture the victim’s initial account or to use body-worn cameras as a source of evidence.

There are some signs that the police are working to mitigate these evidential issues. For example, McClenaghan and Boutard (2017) provide a citation from a detective from the Metropolitan Police Service who explained that officers in London now wore body cameras to help to gather evidence while on call outs:

We are determined to pursue those who use such abuse to intimidate their partner and put them before the courts. While these offences can be challenging to prove, we continue to work hard to help ensure our officers are able to gather the best possible evidence to bring perpetrators to justice.

Barlow et al. (2019) suggest that officers would benefit from additional guidance for conducting coercive control investigations in terms of recognising evidential opportunities available in coercive control cases, as well as recognising and strengthening evidence of coercive control within victim and other third-party statements. They argue that resourcing and training is crucial to improve understanding of the nature and impact of coercive control, not just among the police but at all points of contact within the criminal justice process.

However, Walklate et al. (2018) caution that it is unlikely that training alone will be effective in equipping the police to recognise and respond appropriately to coercive control, as they argue that police training generally focuses on procedure rather than the broader social context, which they view as the key barrier to the successful policing of CCB. A recent study by Brennan et al. (2021, p 11), evaluating the effectiveness of ‘DA Matters’ training between 2016 to 2018, found that the training “was followed by a 41% increase in arrests” for CCB, which “was an average of three additional arrests per force per month”. However, it is not clear which elements of the training had led to an increase in arrests and this effect on arrest rates appeared to be short-lived, falling again around eight months after training.

Brennan et al. (p 11) highlight that the police’s willingness to pursue investigations of CCB can be impacted by other practices within the CJS. They suggest that “if officers perceive there is a low prospect of achieving a charge and conviction for controlling or coercive behaviour, they may quickly lose their initial enthusiasm and revert to pursuing other offences with which they are more familiar” (see also Tolmie, 2018; Wangmann, 2020). This may support Barlow et al.’s (2019) point mentioned above regarding the importance of increasing the understanding of CCB across the whole of the CJS, as intervention at the police level alone may be limited in its long-term efficacy.

More recent literature suggests that some of the evidential difficulties raised above may be exclusive to the English and Welsh CCB offence, due to its requirement to evidence ‘serious adverse effect’ on the victim (in addition to proving the controlling or coercive behaviour of the perpetrator), which, as Bettinson (2020) points out, creates a high evidential threshold and makes prosecuting without the victim’s support impossible. In addition, Wiener (forthcoming) argues that, based on the qualitative research she conducted with judges, it penalises resilience in victims - the more able a victim is to withstand the controlling or coercive tactics of their partner, the lower the chances are that the requirement to prove adverse effect will be met.

Comparing the English and Welsh, Scottish, Irish and Tasmanian approaches, Bettinson (2020, p 205) suggests that the Scottish offence is the most promising model. She explains that the legislation in Scotland covers both current and ex-partners, and it recognises that the victim may not always have to be the target of the threat or violence since “a victim can be coerced or controlled by behaviours directed at others”, like their child(ren). As outlined above, the Scottish offence does not require the police and prosecutors to demonstrate the harm that the victim has suffered, placing the focus of the prosecution on the behaviours and state of mind of the defendant. Finally, with a maximum custodial sentence length of 14 years, the Scottish offence has a sentencing range that, Bettinson states, more adequately reflects the range of severity in offending covered by the legislation. The Scottish offence does not, however, cover controlling or coercive abuse by a family member.

Prosecution and conviction of CCB offences

Owing to the relative recency of the introduction of the CCB offence, and the generally low numbers of cases reaching the prosecution stages of the CJS, much of the literature has focused on the police response to CCB. However, the successful implementation of CCB is not down to police practice alone, as the police do not work in isolation from the other parts of the CJS. Barlow et al. (2019, p 161) emphasise the wide range of people who are crucial to this process: “When new offences are created, demands and expectations for the wider criminal justice process, from the frontline police officer, to the prosecutor, to the judge are also created”.