Learning disabilities and CQC inspection reports

Published 17 July 2018

1. Summary

People with learning disabilities are at risk of poor health and premature death. Consistent with their legal duties under the Equality Act (2010), NHS trusts are required to make reasonable adjustments to their care, such as longer appointment times, to tackle the health inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities. Public sector organisations have a legal duty to ‘anticipate’ difficulties prior to their occurrence and not wait until they emerge.

In 2015 the Care Quality Commission (CQC) included within their inspection regime 4 questions about support for people with learning disabilities, with suggested specific probes to underpin them:

- whether the hospital knows who the people in the hospital with learning disabilities are?

- what reasonable adjustments they can and do make for people with learning disabilities?

- whether they have a specialist nurse for learning disabilities?

- whether they audit the care given to patients with learning disabilities?

This report investigates the extent to which health care for people with learning disabilities is mentioned within CQC inspection reports of 30 general acute hospitals trusts conducted using the specific learning disability questions. Specific questions addressed in this report are:

- do CQC inspection reports mention people with learning disabilities?

- where issues concerning people with learning disabilities are reported in CQC hospital inspection reports, what issues and reasonable adjustments are reported?

- are there any relationships between comments made in the inspection reports and CQC ratings of the Trusts?

This report also investigates the extent to which CQC inspection reports mentioned mental capacity or the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) in relation to any group of patients.

Twenty-nine of the 30 trust-wide inspection reports (97%) and 58 of the 61 specific site reports (95%) included at least one mention of people with a learning disability/learning disabilities.

Most comments about practices for people with learning disabilities were positive across all CQC inspection output types and across all CQC overall ratings. In addition, the proportion of positive comments decreased and the proportion of negative comments increased as CQC ratings became less positive.

Reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities commonly mentioned in CQC inspection reports included: flagging or alerts systems, health passports, acute liaison nurses, auditing practice for people with learning disabilities, quiet rooms, easy read information, staff training, and understanding/managing pain.

All main trust reports (100%) and almost all hospital site reports (95%) mentioned mental capacity. All the main site reports mentioned mental capacity in the summary and 52% mentioned the MCA in hospital site summaries. Comments concerning mental capacity were much more likely to be negative across most CQC inspection output types, with a smaller proportion of positive comments and a higher proportion of negative comments on the MCA as CQC overall ratings became less positive. CQC inspection reports commonly highlighted how (or whether) the MCA was being applied, and the need for staff training in the MCA.

Overall CQC inspection reports routinely contained some information regarding how well hospitals were working for people with learning disabilities, and how well hospitals were applying the MCA. The depth of information in reports varied across trusts, with the potential for CQC reports to more consistently report information collected during inspections.

Recommendations were made to the CQC regarding labelling reasonable adjustments, audits, needs of people with autism (with and without learning disabilities), alerts and flagging systems and mental capacity.

2. Introduction

Access to effective health services can have a major positive impact on the life expectancy of people with learning disabilities.[footnote 1] However, the life expectancy of people with learning disabilities is at least 15 to 20 years shorter than the general population, with a high proportion (36.9%) of deaths that could have been prevented with effective health care. Improving health services for people with learning disabilities, including mainstream hospital services, is a high priority for the government.[footnote 2]

People with learning disabilities have poorer health than their non-disabled peers, differences in health status that are, to an extent, avoidable. As such, these differences represent health inequalities. [footnote 3], [footnote 4], [footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7]

The health inequalities faced by people with learning disabilities in the UK start early in life and result, to an extent, from barriers they face in accessing timely, appropriate and effective health care. The inequalities evident in access to health care could place NHS Trusts in England in contravention of their legal responsibilities defined in the Equality Act 2010, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2010. At a more general level, they are also likely to be in contravention of international obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. [footnote 8].

Under English equalities law, public sector organisations are required to tailor the ways they provide care so that disabled people are not disadvantaged. Law governing the regulation of health care services is more explicit about the requirement for health care providers to:

avoid unlawful discrimination including, where applicable, by providing for the making of reasonable adjustments in service provision to meet the service user’s individual needs [footnote 9] …and to have systems in place to … enable them to assess and monitor the quality of the services provided regularly against this and other requirements.

Reasonable adjustments can mean alterations to buildings by providing lifts, wide doors, ramps and tactile signage. They also mean changes to policies, procedures and staff training to ensure that services work equally well for people with learning disabilities.

For example, people with learning disabilities may require clear, simple and possibly repeated explanations of what is happening, and of treatments to be followed, help with appointments and help with managing issues of consent in line with the MCA. Public sector organisations should not simply wait and respond to difficulties as they emerge: the duty on them is ‘anticipatory’, meaning they have to think out what is likely to be needed in advance.

An Improving Health and Lives Learning Disabilities Observatory (IHaL) survey in 2011 [footnote 10] found that some forms of reasonable adjustment were being widely adopted in some Trusts, although overall it confirmed the view of the Michael Inquiry [footnote 11] that:

There is a clear legal framework for the provision of equal treatment for people with disabilities and yet it seems clear that … services are not yet being provided to an adequate standard” (Michael, 2008, p. 55).

A study by Tuffrey-Wijne and colleagues [footnote 12] examined the barriers to, and enablers of, reasonable adjustments in acute hospitals. The key enablers of reasonable adjustments were the Learning Disability Liaison Nurse (Acute Liaison Nurse), and the ward manager. Barriers included a lack of effective systems for identifying and flagging people with learning disabilities, a lack of staff understanding, a lack of responsibility and accountability for implementing reasonable adjustments, and a lack of funding. MacArthur and colleagues [footnote 13] noted that Acute Liaison Nurses are the most appropriate means of delivering reasonable adjustments, due to their familiarity with the hospital and with the individual needs of people with learning disabilities.

2.1 CQC inspections

In 2013 the CQC, the independent regulator of health and social care services in England, implemented a new strategy and format for inspections [footnote 14]. This approach asks the following 5 questions of all regulated services:

- are they safe?

- are they effective?

- are they caring?

- are they well led?

- are they responsive to people’s needs?

CQC Raising standards, putting people first: Our strategy for 2013 to 2016

Elements of this new strategy were specifically focused on people with learning disabilities, the strategy states we will:

-

inspect service more often where there is a high risk to people who use them, and where people are vulnerable because of their circumstances, such as services caring for people with learning disabilities, those caring for people in their own homes, and those caring for people with mental health issues (page 9)

-

expect all services, particularly those for people with mental health issues, learning disabilities and dementia, to have effective ways of making sure they listen to and act on people’s views and experiences (page 18)

-

introduce this approach first to services for people with learning disabilities, other high-risk services where there is less public scrutiny and openness, and then all organisations proposing to offer new care services. This will be an effective way of holding people to account for the quality of care provided by their organisation (page18)

-

expect all services, particularly those for people with mental health issues, learning disabilities and dementia, to have effective ways of making sure they listen to and act on people’s views and experiences (page18)

-

strengthen our focus around the Mental Health Act, the Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) to protect the human rights of some of the most vulnerable people in society, particularly those who have had their freedom restricted by being detained and treated against their will. We are committed to strengthening the protection of people with learning disabilities, whether or not they are detained (page 20)

Since the summer of 2014, CQC has incorporated 4 questions into their inspection framework for acute hospitals. These 4 questions should be asked across all core services within hospitals:

- how many patients with a learning disability are in the hospital?

- do you have a learning disability liaison nurse?

- how do you ensure reasonable adjustments are made?

- can you show us some outcomes from the care and treatment of patients with a learning disability?

In 2016, the CQC operationalised the 4 questions set in 2014 into a more specific set of 4 main questions and suggested specific probes to support them:

- whether the hospital knows who the people in the hospital with learning disabilities are?

- what reasonable adjustments they can and do make for people with learning disabilities

- whether they have a specialist nurse for learning disabilities

- whether they audit the care given to patients with learning disabilities

The following areas and questions are suggested for specific exploration:

- is a flagging system used in the hospital for people with learning disabilities?

- do staff have access to the flagging system and information about the people with learning disabilities in the hospital?

- is there support for families and carers to be in hospital?

- is there regular training for all staff, including learning disability awareness and risk?

- is there a board level representative with responsibility for learning disabilities?

- is the care and treatment of people with learning disabilities audited?

Thirty-one trusts had been inspected under the new regime at the time the analysis began and a list of these was provided by the CQC. This follows a previous interim analysis [footnote 15] which examined the main CQC inspection reports of 63 trusts (of all types) published in 2014, reporting relatively little mention of people with learning disabilities within these inspection reports.

This report examines in more detail CQC inspection reports for 30 acute NHS Trusts, published in 2016 when questions concerning people with learning disabilities should have become part of the routine of CQC inspections. This analysis focuses and builds on the previous interim analysis in two ways. First, this analysis focuses on acute hospital trusts rather than looking across all trust types, as these trusts are where effective, reasonably adjusted health services can have a major impact on the health of people with learning disabilities. Second, this analysis examines both main trust inspection reports and inspection reports of specific acute trust sites, where more detailed comments concerning reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities may be present, rather than just examining main trust reports as the interim analysis did.

Because of the importance of the MCA [footnote 16] for the treatment of people with learning disabilities while in hospital, and concerns about how well hospital staff are adhering to the MCA generally, this report also examines in detail the extent and nature of CQC inspection report mentions relating to the MCA for all groups of people.

3. Methods

This report addresses 3 main questions relating to people with learning disabilities:

- do CQC inspection reports mention people with learning disabilities?

- there issues concerning people with learning disabilities are reported in CQC hospital inspection reports, what issues and reasonable adjustments are reported?

- is there any relationship between comments made in the inspection reports and CQC ratings of the trusts?

The report also addresses the same 3 questions relating to the MCA:

- do CQC inspection reports mention the MCA?

- there issues concerning the MCA are reported in CQC hospital inspection reports, what issues and reasonable adjustments are reported?

- are there any relationships between comments made in the inspection reports and CQC ratings of the trusts?

A list of 31 NHS Trusts that had undergone inspection under the new regime was provided by the CQC. Both the NHS trust main report (n=30) and accompanying sub-reports for specific hospitals/services within the trust (n=61 across the 30 NHS Trusts) were examined. Thirty NHS trust main reports were located (for one Trust the inspection report had not been published) along with a further 61 specific acute hospital site sub-reports. Specific trust site reports were excluded from the analysis if they did not hold an acute function, as these have differing inspection regimes and report formats.

For each listed trust the inspection report and sub-reports were located on the CQC website. The reports were usually in the form of a letter from the Chief Inspector, a summary and then the main report split into specific core services: accident and emergency, medical care (including frail elderly), surgery, intensive/critical care, maternity, paediatrics/children’s care, end-of-life care, and outpatients.

All reports were searched for the term ‘learning disab’, this enabled references to learning disabilities or learning disability to be picked up. Reports were also searched for ‘learning diff’ to pick up mentions of learning difficulties or learning difficulty, ‘autis’ for autism, and ‘mental capacity’. Mentions of people with learning disabilities, autism, learning difficulties or mental capacity were cut and pasted into an Excel database where they were then read for common themes, and compared across trust CQC rating and type of trust.

The number of overall mentions was recorded in a spreadsheet including the number of mentions in the Chief Inspector’s letter and summary. In the cut and paste Excel database repeated information (for example the exact same wording appearing in both the chapter summary and main body of the chapter) and titles were not included, therefore the overall number of mentions in the Excel database are lower than the total mentions. As the Excel database was designed to capture the range of mentions in CQC inspection reports, including repetitions of the same wording in CQC reports for the same trust would not have made any difference to the analysis.

The mentions were classified in the Excel database into mutually exclusive categories of ‘positive’ (where the comment was clearly reporting on perceived good practice), ‘negative’ (where the comment was clearly reporting on practice perceived as requiring improvement), and ‘mixed/neutral’ (where the comment contained elements of both good and less good practice, or was describing a practice without a clear evaluation attached).

4. Findings

The findings section is structured to address the 3 main questions outlined above, first for mentions of people with learning disabilities and second for mentions of mental capacity.

All the following quotations are taken from CQC reports published between July 2015 and May 2016. The trusts or hospitals have been kept anonymous in this report as practices mentioned in the CQC reports may not reflect the current practice of the relevant trusts. All the issues raised by the CQC were applicable to several trusts or hospitals rather than any individual trust. Designators describing the anonymised location and type of hospital have been used to give context to the quotes.

4.1 Do CQC inspection reports mention people with learning disabilities and/or mental capacity?

Across all main Trust reports (n=30) and site-specific reports (n=61), findings show 506 separate mentions of the terms ‘learning disability or learning disabilities’ (for the purpose of this report these are referred to as learning disabilities from here on in) and 532 separate mentions of the Mental Capacity Act (or MCA). Across all the reports, mentions of the terms ‘learning difficulty or learning difficulties’ (from here on referred to as learning difficulties, which may refer to a different or broader group of people than learning disability) were rare (n=19), and uses of the term ‘autism’ (or variants of this term) were also uncommon (n=54) (see Appendix Table A1 for more details). Because of the relative lack of mentions of people with ‘learning difficulties’ or people with autism, there were insufficient data to conduct detailed quantitative or thematic analyses. Most references concerning autism in the inspection reports were related to children with autism in relation to services offered within hospitals, or to initiatives at the hospital such as sensory spaces. There were only 5 mentions of autism with regard to adults and 4 of these related to people with learning disabilities and autism, indicating that the experiences of people with autism but without learning disabilities are not routinely reported on. Therefore the rest of the analyses in this report focus on mentions of people with ‘learning disabilities’ and mentions of the MCA.

Next, for the 30 trusts inspected, the number of Chief Inspector’s letters, the number of main report summaries, and the number of main reports were searched for any mention of people with learning disabilities. The number of positive, negative and mixed/neutral comments contained in each of these formats are reported.

Following on from these, similar data is presented for the 61 site-specific CQC inspection reports.

The analyses were repeated for mentions of the MCA.

4.2 What issues are raised in CQC inspection reports?

In this section, there is a content analysis of the comments made in CQC inspection reports concerning services for people with learning disabilities. The comments were placed into themes, initially using the framework of the CQC inspection learning disability questions and revising and adding to these where necessary to reflect the content of the comments.

The number of positive, negative and mixed comments are included under each theme, combined for all formats of CQC inspection report. The major issues mentioned under each theme are discussed alongside with examples from inspection reports.

The number of positive, negative and mixed comments concerning the MCA are presented, and discussion is included of the major issues mentioned in inspection reports regarding how trusts are implementing the MCA.

4.3 Are there any relationships between comments in inspection reports and CQC ratings?

In this section, the number of positive, negative and mixed/neutral mentions made in CQC inspection reports are featured according to whether the service was rated by the CQC as outstanding, good, requires improvement, or inadequate. Findings for the Chief Inspector’s letter and summary of the main report are presented separately.

Again, similar analyses are provided for mentions of the MCA.

5. Findings 1: People with learning disabilities

5.1 Do CQC inspection reports mention people with learning disabilities?

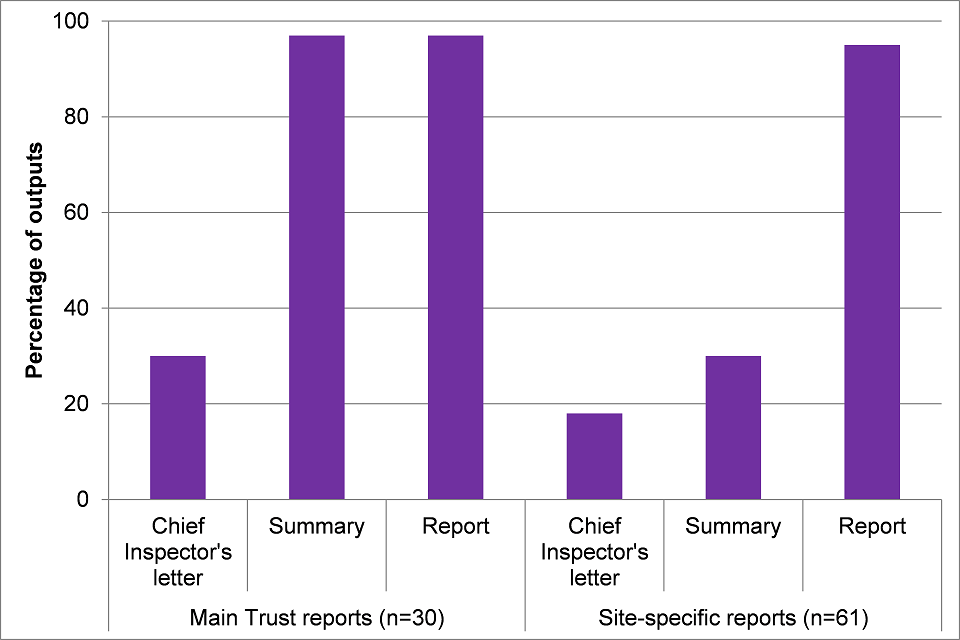

CQC outputs from trust inspections include a Chief Inspector’s letter, a summary of the report, and the report itself. These are available for both the main trust report and for site-specific reports. Figure 1 below shows the percentage of outputs for main Trust reports (out of 30 reports) and the percentage of outputs for site-specific reports (out of 61 reports) mentioning learning disabilities.

For main trust reports, almost a third of Chief Inspector’s letters (30%) mentioned learning disabilities, and almost all main trust summaries (97%) and main reports (97%) mentioned learning disabilities. For site-specific reports, fewer Chief Inspector’s letters (18%) and summaries (30%) mentioned learning disabilities, although almost all site-specific reports (95%) did.

Figure 1: Percentage of outputs relating to main trust reports and site-specific reports mentioning learning disabilities.

The median number of mentions of learning disabilities was 1 to 5 in main trust reports and 11 to 15 in site-specific reports (see Appendix Table A2 for more details).

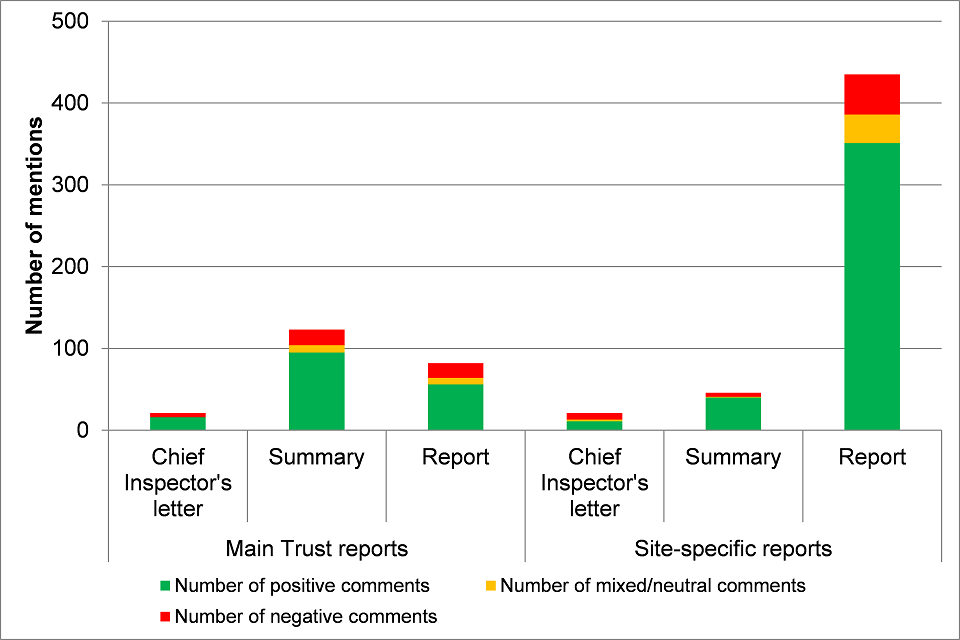

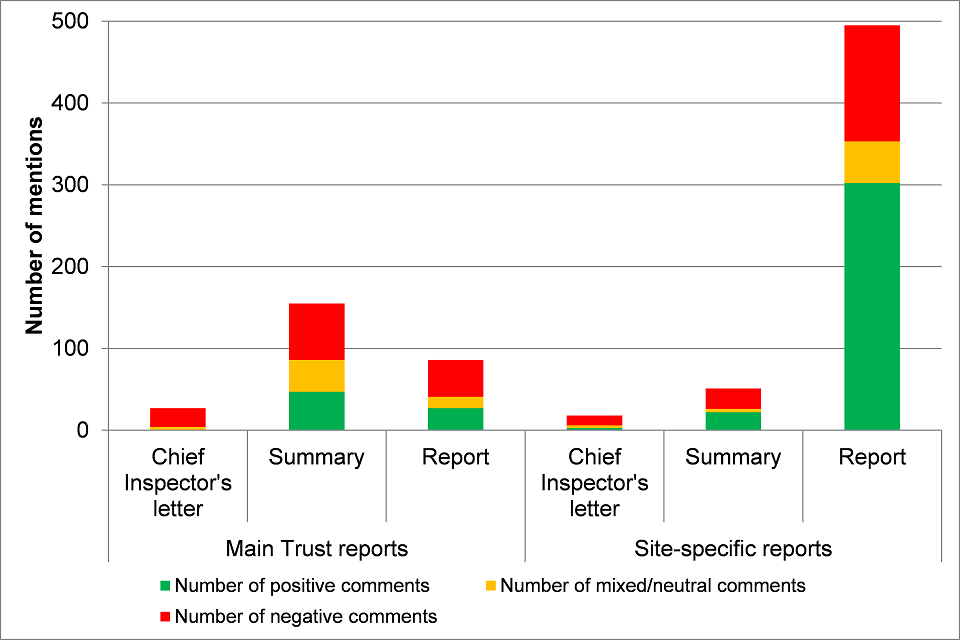

Figure 2 below shows the number of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions of practices concerning people with learning disabilities in all CQC inspection outputs. Although the number of mentions varied across types of CQC inspection output, in all types of output most mentions were positive (52% to 87%), with a minority of negative mentions (11% to 38%). More detailed information is available in Appendix Tables A3 to A8.

Figure 2: Number of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions of practices concerning people with learning disabilities: all CQC inspection outputs.

5.2 What issues are raised in CQC inspection reports with regard to people with learning disabilities?

The comments in reports were read and coded into categories: positive, negative and mixed/neutral. Mixed comments included statements that included both positive and negative elements. Common themes in the quotes were noted and searched for.

Finding examples of reasonable adjustments in the report comments were difficult, as practices that constituted reasonable adjustments were seldom reported as such, with only 20 occurrences of the term ‘reasonable adjustments’ in the positive comments. Clearly reporting practices such as longer appointment times and hospital passports in inspection reports as examples of reasonable adjustments would highlight Trusts’ legal obligations under the Equality Act 2010.

Flagging/alerts

Within the positive learning disabilities comments, ‘flag’ or ‘alert’ was mentioned 26 times. CQC inspection reports make a distinction between a flag verses an alert, illustrated by a major city hospital report. The report stated that:

The trust employed one learning disability nurse at the [named] site. Clinical staff sent an alert whenever an adult with a learning disability was admitted or attended the ED. Referrals were sent either as a safeguarding concern with the safeguarding adults team or as a routine notification of a learning disability admission.

However, the same report also noted:

Meeting people’s individual needs: There was no universal flagging system in place for patients with a learning disability.

The alert requires clinical staff to manually send an alert to the learning disability nurse, whereas a flagging system usually informs the learning disability lead automatically when a patient with learning disabilities is admitted to hospital. Clear and consistent definitions of what constitutes an alert or a flagging system would be helpful.

Other examples of reasonable adjustments included hospital passports, longer appointments, and being seen at the start of the clinic list.

Health passports

There were 41 mentions of ‘passport’ in the positive learning disabilities comments, for example:

Northern town hospital, medical care:

The trust used a health passport document for patients with learning disabilities. Patient passports provide information about the person’s preferences, medical history, routines, communication and support needs. They were designed to help staff understand the person’s needs.

Midlands town trust:

We spoke with staff in the department about caring for patients with a learning disability. Staff said that the patient sometimes arrived in the department with a patient passport, which they found helpful. This was noted on the patient’s electronic record.

Acute Liaison Nurses

There were 14 positive references to learning disability liaison nurses.

Midlands city hospital, surgery:

There was a Learning Disability Liaison team with staff provided by another NHS trust. The team had an office base on the [named] site with access to the trust’s electronic systems. Staff alerted the team when they were caring for a person with a learning disability.

We spoke with a small group of parents and carers of people with a learning disability who said they were pleased with this service. The parents and carers said the team supported them well. However, they felt there was a gap in the service as it was not available at weekends.

South West NHS trust, maternity and gynaecology:

The learning disability support team provided assistance to patients living with a learning disability who were admitted to hospital. The team consisted of two whole time equivalent Registered Learning Disability Nurses who were employed by an external provider and had honorary contracts with the trust. For planned admissions, the Learning Disability liaison nurses contacted the patient or their relatives/representatives to help decide what reasonable adjustments were required if any. We were provided with examples of such reasonable adjustments that had been provided to previous patients including easy read information, being first on the theatre list to reduce waiting, provision of a quiet environment and open visiting. For emergency admissions, any reasonable adjustments required would be documented in the patient’s Learning Disability care plan and discussed and agreed with the ward team.

It was not always clear in the report exactly how many hours Acute Liaison Nurses were available to support people with learning disabilities in hospital and whether these resources were adequate for the Trust operation. The good practice example above gives details of how many Acute Liaison Nurses work at the Trust, and how they are employed.

Audit

There were 13 references to the auditing of the care of people with learning disabilities (audit: 8 positive comments, 1 negative, 4 neutral), an example of which is below:

Northern city hospital, summary:

A retrospective documentation audit of patients with a diagnosed learning disability who accessed inpatient services was undertaken in April 2014. Consequently, the trust implemented several actions. These included revision of the ‘All About Me’ hospital passport to include a section on reasonable adjustments required when attending hospital, introduction in August 2014 of a reasonable adjustment care plan and funding sought to provide equipment to improve the experience of people with learning disabilities in the acute setting.

Quiet rooms

There were 3 mentions of quiet rooms for people with learning disabilities to use to get away from busy waiting areas, for example:

South West hospital, surgery:

Patients with additional or extra needs were supported for their admission to hospital. The hospital trust had a team of nursing staff who specialised in supporting patients with learning disabilities. Members of this team would be available to come to a ward or unit to help staff provide support for a patient with a learning disability. They would also make advance arrangements to make the patient’s visit to the hospital easier for the patient and any carers. This included arranging a ‘walk-through’ the operating theatre for a patient and their carers if this was considered helpful and appropriate. Patients visiting the pre-operative assessment unit ([named]) who had different or complex needs were able to use quiet rooms or given early appointments so they could be seen first. The trust had produced a booklet for patients with a learning disability called ‘My Health in Hospital’ and a range of Easy Read leaflets on common procedures such as having a blood test, X-ray or scan. Staff said either the patient, their main carer, or the hospital staff would complete the booklet with essential information about the patient. A number of staff commented upon how helpful the booklets were to provide more individualised care for their admission to hospital. The hospital trust had a team of nursing staff who specialised in supporting patients with learning disabilities. Members of this team would be available to come to a ward or unit to help staff provide support for a patient with a learning disability.

Easy read

There were 10 positive mentions of the use of easy read literature. These were usually easy read versions of patient information leaflets but also sometimes included other items such as easy read menus:

City University hospital, medical care:

The hospital provided ‘Passports’ for patients living with a learning disability, which allowed them to identify to staff their likes and dislikes in a pictorial format. There was also an ‘Easy Read’ menu for patients.

Training

With regard to the negative comments, there were 19 mentions of training. These usually referred to a lack of available training, or if training was offered a lack of take up of this training:

Northern rural NHS Trust, summary:

There was no learning disability strategy in place at the time of the inspection. Strategic aims were being developed and a non-executive board lead identified. There was not sufficient resource identified including specialist staff, training and systems in place to care for vulnerable people, specifically those with learning disabilities and dementia. A highly motivated and compassionate quality matron had the lead for dementia and also learning disabilities.

Pain

There were 8 mentions of pain in the negative comments. These either referred to a lack of tools to assess pain or that the inspection staff observed people with learning disabilities being given insufficient pain relief. If patients were observed in pain, inspectors reported this immediately to clinical staff:

Midlands town trust:

There were no specialised tools in place to assess pain in those with a cognitive impairment such as a learning disability or those living with dementia.

Midlands NHS Trust, summary:

During a visit to the ED we saw two patients’ pain relief was delayed and both patients were distressed; one was a young child and the other patient had learning disabilities. The inspection team informed the nurse in charge.

The comments in the reports covered a wide range of practices, both positive and negative. This highlights that people with learning disabilities accessing acute hospitals can experience very different levels of care.

5.3 Are there any relationships between comments in inspection reports and CQC ratings?

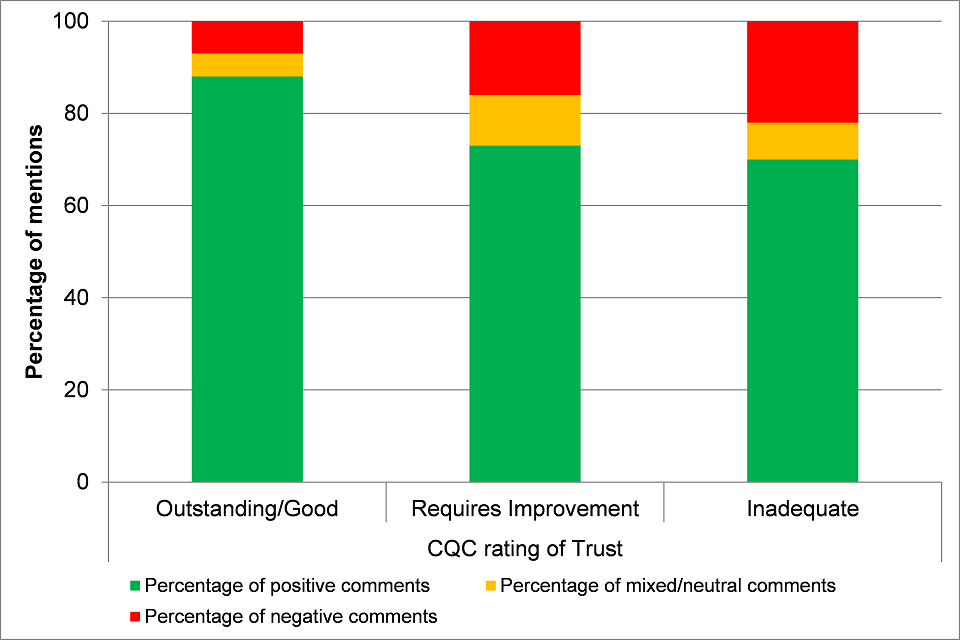

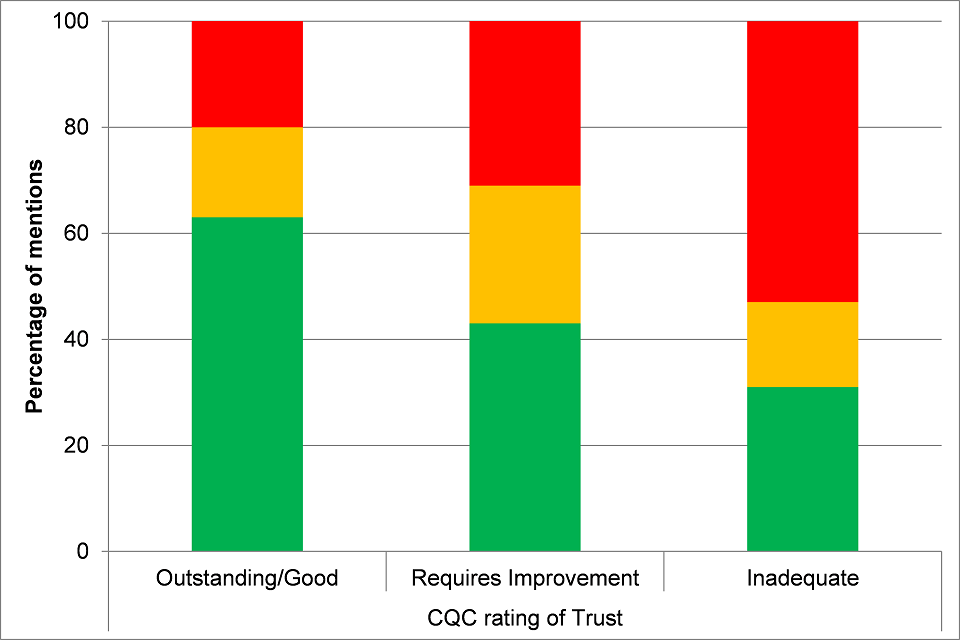

Figure 3 below shows the percentage of positive, negative and mixed/neutral comments (duplicate information excluded) relating to learning disabilities made across all CQC inspection reports, grouped by the overall rating the CQC gave to the Trust or site (see Appendix Table A9 for more details). Most comments were positive in all three rating categories, although as CQC ratings become less positive, the proportion of positive comments dropped and the proportion of negative ones increased (‘Outstanding/Good’: 88% positive, 7% negative; ‘Requires improvement’: 73% positive, 16% negative; ‘Inadequate’: 70% positive, 22% negative).

Figure 3: Percentage of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions of practices for people with learning disabilities by CQC rating of Trust.

6. Findings 2: Mental Capacity Act

We repeated the analyses above for mentions of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) in CQC inspection reports. NHS Trusts fulfilling their obligations under the MCA are obviously important for people with learning disabilities but are important for other groups of people too.

6.1 Do CQC inspection reports mention the Mental Capacity Act (MCA)?

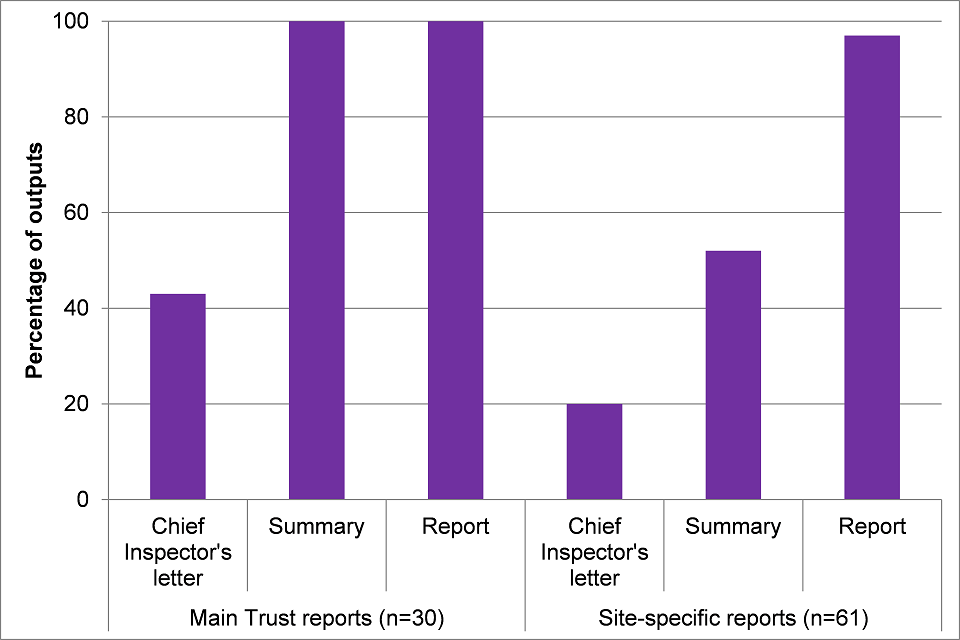

CQC outputs from trust inspections include a Chief Inspector’s letter, a summary of the report, and the report itself. These are available for both the main trust report and for site-specific reports. Figure 4 below shows the percentage of outputs for main trust reports (out of 30 reports) and the percentage of outputs for site-specific reports (out of 61 reports) mentioning the MCA.

For main trust reports, over two-fifths of Chief Inspector’s letters (43%) mentioned the MCA, and all main trust summaries (100%) and main reports (100%) mentioned the MCA. For site-specific reports, fewer Chief Inspector’s letters (20%) and summaries (52%) mentioned the MCA, although almost all site-specific reports (97%) did.

Figure 4: Percentage of outputs relating to main trust reports and site-specific reports mentioning the MCA.

Main trust reports made between 1 and 63 mentions of the MCA, with 13 (43%) each making either 1 to 5 or 6 to 10 references. Site reports made more references; Appendix Table A10 gives the details.

Figure 5 below shows the number of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions of practices concerning the MCA in all CQC inspection outputs. With the exception of site-specific reports, where the majority of mentions of practices concerning the MCA were positive (61% positive, 29% negative), in all other types of output a minority of mentions were positive (15% to 43%), with more negative than positive mentions (45% to 85%). More detailed information is available in Appendix Tables A11 to A16.

Figure 5: Number of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions of the MCA: all CQC inspection outputs.

6.2 What issues are raised in CQC inspection reports with regard to mental capacity?

Comments with regard to mental capacity were mainly concerned with compliance with the Mental Capacity Act across various departments of the trust. Inspection reports varied in the extent to which they mentioned the evidence the inspection team had used in coming to a reported conclusion about MCA practices. For example:

Midlands town hospital, medical care:

Ward staff were clear about their roles and responsibilities regarding the Mental Capacity Act (2005). They were clear about processes to follow if they thought a patient lacked capacity to make decisions about their care. The Intermediate Discharge Team was involved in assessing capacity and the Physiotherapy team had a safeguarding lead. Best interest evaluations were undertaken when required.

Training

There were 90 positive mentions of staff training:

City general hospital, outpatients:

Staff received training on the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (MCA) and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) and were confident about seeking consent from patients.

In contrast, there were 53 negative mentions related to training. These included training on mental capacity being unavailable or low update of non-mandatory training modules:

Midlands district general hospital, outpatients:

Staff had not received training in the Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards.

6.3 Applying the MCA

Staff having undergone training did not necessarily guarantee that staff were able to apply the principles of the MCA. Many of the 39 comments in the neutral category noted that staff had undergone training or understood the principles of the act but that application of the MCA was poor:

City NHS Trust, summary:

Staff had attended training on the Mental Capacity Act 2005, but some staff, in both inpatients and community services, were unsure how to translate the principles into practice.

Southern town hospital, critical care:

Staff had an effective understanding of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. However, there was some uncertainty amongst staff about how Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) impacted on the treatment of patients in the critical care setting.

An example from a Midlands district general hospital illustrates the possible impact of poor understanding of the MCA and a lack of an out of hours safeguarding service.

Midlands district general hospital, maternity:

There was a general lack of awareness of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS), especially on the gynaecology ward. Staff said they had not received training and were unable to describe how they would act to ensure the proper steps were taken to protect someone who did not have capacity. They were unable to confirm how capacity could be determined. They told us they would refer to the safeguarding team between Monday and Friday, but were not aware of how to seek authorisation from deprivation of liberty, how to make a best interest decision for someone or the difference between lawful and unlawful restraint.

6.4 Are there any relationships between comments in inspection reports and CQC ratings?

Figure 6 below shows the percentage of positive, negative and mixed/neutral comments (duplicate information excluded) relating to mental capacity made across all CQC inspection reports, by the overall CQC rating for that Trust or specific site (see Appendix Table A17 for more details). As Figure 6 shows, the proportion of positive comments drops and the proportion of negative comments rises as CQC ratings become less positive. For example, Outstanding/Good rating: 63% positive comments vs 21% negative, whereas for the lower ratings: Requires Improvement rating: 42% positive vs 45% negative and Inadequate rating: 31% positive vs 53% negative.

(Outstanding/Good 63% positive comments and 21% negative comments verses Requires improvement 43% positive comments and 45% negative comments vs Inadequate 31% positive comments and 53% negative comments).

Figure 6: Percentage of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions of mental capacity by CQC rating of Trust.

6.5 Relationship between mentions of learning disability and mental capacity

There were differences between comments in inspection reports concerning learning disability and mental capacity, where learning disability comments were more likely to be positive regardless of the overall rating. For example, 70% of comments in the Chief Inspector’s letter in main trust reports about learning disabilities were positive, compared with only 15% of MCA comments.

There were some trusts, for example, a hospital in a southern town, where comments relating to learning disabilities were all positive but appeared at the least to be called into question by accompanying comments indicating that staff did not have a full understanding of the application of the MCA. For example:

Outpatients and diagnostic imaging:

Staff said they felt confident to challenge doctors over consenting issues. For example, one nurse from the learning disabilities team questioned a junior doctor who signed inappropriately on behalf on the patient on a consent form and advised the doctor that the patient had capacity. This responsive care prevented a patient from receiving a treatment without proper consent. As a result of this, the consent form was filled in again appropriately and the doctor was challenged on his practice.

There were also examples of hospitals rated good overall but with examples of less good care for people with learning disabilities:

South West hospital medical care (including older people’s care):

Patients with a learning disability were supported to be accompanied by their usual carer. The carer was enabled to stay on the ward with the patient and continue to be active in their care. We saw this to be the case. When the carer was not present staff would be required to undertake the patient’s care needs. Staff explained that most patients with a learning disability were admitted with their regular carer; however, we saw that this was not always the case and one patient did not have any carer with them. We saw the staff were not engaging or interacting with this patient and the patient was left for periods of time unattended. Staff training for learning disability was not mandatory and should the learning disability lead nurse not be available, then the patients’ needs may not be consistently met. There was only one learning disability nurse available and so the service was not available out of their working hours.

In this example, the facilitation of allowing a usual carer to stay in hospital with an individual with learning disabilities is identified as a reasonable adjustment, although in this case it meant that hospital staff interpreted this to mean that care would be undertaken by others. The staff were not trained in nursing people with learning disabilities and the trained nurse was only available during certain hours.

In the next example, the hospital was rated good but did not have a system to identify patients and expressed a poor understanding of the MCA with regard to patients with learning disabilities.

South East county hospital, urgent and emergency services:

Staff received assistance from [trust name] staff in regards to the assessment of mental capacity to consent to treatment. Staff acknowledged that there was insufficient training in the assessment of capacity with patients with a learning disability. We found no evidence of a plan to address this.

There was no system in place to help identify patients with a learning disability. There was not a passport system in use to help identify patients with a learning disability.

The overall rating of the NHS Trust did not always reflect the care of people with learning disabilities or trusts’ understanding of the MCA.

7. Conclusions and recommendations

The comments in the inspection reports cover a wide range of practices, both positive and negative. This highlights that people with learning disabilities accessing acute hospitals can experience very different standards of care.

This new analysis of CQC inspection reports has found that compared to the previous analysis, there was much better coverage of health care for learning disabilities. In the 2015 analysis and report, just over half (54%) of inspection reports mentioned people with learning disabilities. In other cases, it was not clear whether questions regarding people with learning disabilities had been asked but the findings not covered in reports.

During the analysis for this 2016 report this had improved significantly, with 29 of the 30 trust-wide inspection reports (97%) and 58 of the 61 specific site reports (95%) including at least one mention of people with learning disabilities.

Although there was almost universal coverage of health care practices relating to people with learning disabilities in the reports, this was not always covered in the summaries and Chief Inspector’s letters. In all report formats, the majority of comments concerning health care for people with learning disabilities were positive.

Within the thematic analysis examples of reasonable adjustments were rarely labelled as such within inspection reports, making them sometimes difficult to locate. References were included to flagging systems, health passports, acute liaison nurses, easy read information, staff training, audits, quiet rooms, and identifying/managing pain.

Mental capacity was not examined during the previous analysis of CQC inspection reports. Mental capacity was included in this report because of the impact on a hospital’s understanding of mental capacity to people with learning disabilities. Almost all inspection reports mentioned mental capacity, with most comments being negative and focused on how trusts applied the MCA and the need for staff training.

For mentions of learning disabilities and mentions of mental capacity, trusts with less positive overall ratings had in their inspection reports a smaller proportion of positive comments and a greater proportion of negative comments. However, Trusts with overall good ratings could report poor practices in both these areas.

Some issues for the CQC to consider arising from these findings are as follows:

Labelling reasonable adjustments

There were examples of good practice in CQC inspection reports but they were often difficult to find as they are not categorised as reasonable adjustments. For example, a report may highlight that in outpatients people with learning disabilities are given longer appointments or usually seen first, but they do not use the term ‘reasonable adjustment/s’. Using the term ‘reasonable adjustment/s’ when describing these practices could help raise awareness of good practices within a legal equalities framework that NHS services should be compliant with. As we stated in our previous interim report:

Clear, specific summaries of good practice are very helpful for sharing (and for raising the profile of reasonable adjustments within hospital trusts). Clear, specific examples of poor practice, particularly when linked to clear recommendations for improvement, are equally important.

Audits

Relatively few inspection reports noted audits of the care of people with learning disabilities, despite all foundation trusts reporting to NHS Improvement in 2014 that they had undertaken audits of their practices relating to people with learning disabilities. It would be useful to know if such audits have been conducted, whether they have been made public, and how they have been used to drive improvements for people with learning disabilities.

The needs of people with autism (with and without learning disabilities)

There were very few mentions of practices concerning people with autism (19) in the reports. The English Government’s Autism Strategy and accompanying statutory guidance [footnote 17] [footnote 18] places responsibilities on NHS Trusts concerning people with autism similar to those concerning people with learning disabilities. The CQC might consider developing a similar set of focused questions to evaluate the extent to which NHS Trusts are meeting their responsibilities to people with autism.

Alerts vs flagging systems

CQC reports used the terms flag and alert differently, and it was sometimes unclear if these terms were being used interchangeably or to refer to different processes. Consistent definitions and usage of these terms across CQC report would be helpful for CQC for them to clarify their inspection processes and outcomes and for the lay reader.

Mental capacity

CQC inspection reports identified some poor practice in knowledge and application of the MCA. The CQC may wish to consider whether non-adherence to the law concerning the MCA should act as a ratings limiter with respect to overall CQC ratings of a Trust’s performance.

8. Appendix: Data tables

Data tables to accompany the report.

Table A1: Number of mentions of learning disabilities, learning difficulties, autism, and the Mental Capacity Act anywhere in CQC inspection reports.

| Number of comments | Positive | Negative | Mixed/neutral | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning disabilities | 393 | 67 | 46 | 506 |

| Mental capacity | 298 | 168 | 66 | 532 |

| Autism | 15 | 1 | 3 | 19 |

| Learning difficulties | 39 | 8 | 7 | 54 |

Table A2: Number of mentions of learning disability/disabilities in CQC main and specific site reports.

| Number of comments in report | Main trust sites | Hospital sites | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 to 5 | 18 | 17 | 35 |

| 6 to 10 | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| 11 to 15 | 1 | 10 | 11 |

| 16 to 20 | 2 | 14 | 16 |

| 21 to 25 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 26 to 30 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 31 or over | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 30 | 61 | 91 |

Table A3: Number of mentions of learning disabilities in Chief Inspector’s letter accompanying main trust reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Overall trust rating | Number of trusts with mentions in Chief Inspector’s letter | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Requires improvement | 7 | 15 | 3 | 0 |

| Inadequate | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 9 | 16 | 5 | 0 |

Table A4: Number of mentions of learning disabilities in summary accompanying main trust reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Overall trust rating | Number of trusts with mentions in summary | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 8 | 31 | 3 | 2 |

| Requires improvement | 17 | 51 | 15 | 6 |

| Inadequate | 4 | 13 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 29 | 95 | 19 | 9 |

Table A5: Number of mentions of learning disabilities in main trust reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Overall trust rating | Number of hospital sites with comments | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Number of mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 8 | 14 | 1 | 0 |

| Requires improvement | 17 | 35 | 14 | 8 |

| Inadequate | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 29 | 56 | 18 | 8 |

Table A6: Number of mentions of learning disabilities in Chief Inspector’s letter for hospital site reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Rating of hospital site (not overall trust rating) | Number of hospital sites with comments in Chief Inspector’s letter | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Requires improvement | 7 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| Inadequate | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 11 | 11 | 8 | 2 |

Table A7: Number of mentions of learning disabilities in summary accompanying hospital site reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Rating of hospital site (not overall trust rating) | Number of hospital sites with comments in summary | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 4 | 15 | 1 | 0 |

| Requires improvement | 10 | 19 | 4 | 0 |

| Inadequate | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 18 | 40 | 5 | 1 |

Table A8: Number of mentions of learning disabilities in hospital site reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Rating of hospital site (not overall trust rating) | Number of sites | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Number of mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 20 | 134 | 11 | 8 |

| Requires improvement | 31 | 177 | 28 | 22 |

| Inadequate | 6 | 35 | 10 | 5 |

| Total | 58 | 351 | 49 | 35 |

Table A9: Number of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions relating to learning disabilities in all inspection reports by overall CQC rating.

| Mentions relating to learning disabilities | Positive | Negative | Mixed/neutral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 148 | 12 | 8 |

| Requires improvement | 198 | 42 | 30 |

| Inadequate | 42 | 13 | 5 |

Table A10: Number of mentions of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) in main trust reports and in specific site reports.

| Number of comments and range | Main trust site reports | Hospital site reports | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 to 5 | 13 | 6 | 19 |

| 6 to 10 | 13 | 8 | 21 |

| 11 to 15 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 16 to 20 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 21 to 25 | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| 26 to 30 | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| 30 and over | 0 | 24 | 24 |

| Total | 30 | 61 | 91 |

Table A11: Number of mentions of mental capacity in Chief Inspector’s letter in main trust reports by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Overall trust rating | Number of trusts with comments in Chief Inspector’s letter | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Requires improvement | 9 | 0 | 16 | 2 |

| Inadequate | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 13 | 0 | 23 | 4 |

Table A12: Number of mentions of mental capacity in main trust report summaries by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Overall trust rating | Number of hospital sites with comments in summary | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 8 | 20 | 6 | 11 |

| Requires improvement | 18 | 25 | 47 | 22 |

| Inadequate | 4 | 2 | 16 | 6 |

| Total | 30 | 47 | 69 | 39 |

Table A13: Comments relating to mental capacity in main trust reports.

| Overall trust rating | Number of main trusts with mentions | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Number of mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 8 | 10 | 7 | 5 |

| Requires improvement | 18 | 16 | 26 | 6 |

| Inadequate | 4 | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Total | 30 | 27 | 45 | 14 |

Table A14: Number of mentions of mental capacity in Chief Inspector’s letter accompanying hospital site report by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Rating of hospital site (not overall trust rating) | Number of trusts with comments in Chief Inspector’s letter | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Requires improvement | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Inadequate | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 3 | 12 | 3 |

Table A15: Number of mentions of mental capacity in hospital site report summaries by nature of comment and CQC overall rating.

| Rating of hospital site (not overall trust rating) | Number of hospital sites with comments in summary | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 9 | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| Requires improvement | 21 | 10 | 20 | 3 |

| Inadequate | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 32 | 22 | 25 | 4 |

Table A16: Comments concerning mental capacity in hospital site reports.

| Rating of hospital site (not overall trust rating) | Number of sites with mentions | Number of positive comments | Number of negative comments | Number of mixed/neutral comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 21 | 120 | 28 | 23 |

| Requires improvement | 31 | 150 | 95 | 22 |

| Inadequate | 6 | 25 | 19 | 6 |

| Total | 59 | 302 | 142 | 51 |

Table A17: Number of positive, mixed/neutral and negative mentions relating to mental capacity in all inspection reports by overall CQC rating.

| Mentions relating to mental capacity | Positive | Negative | Mixed/neutral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 161 | 56 | 45 |

| Requires improvement | 202 | 210 | 55 |

| Inadequate | 29 | 50 | 15 |

9. References

-

A.M.W., C., People with intellectual disability: What do we know about adulthood and life expectancy? Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 2013. 18(1): Pages 6 to 16. ↩

-

A.M.W., C., People with intellectual disability: What do we know about adulthood and life expectancy? Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 2013. 18(1): Pages 6 to 16. ↩

-

Care, D.o.H.a.S., The Government’s mandate to NHS England for 2018 to 19. 2018, Department of Health and Social Care: London. ↩

-

Emerson, E., The determinants of health inequities experienced by children with learning disabilities. 2015, Public Health England.: London. ↩

-

Emerson, E. and C. Hatton, Health inequalities and people with intellectual disabilities. 2014, Cambridge Cambridge University Press: Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Emerson, E., et al., Health inequalities and people with learning disabilities in the UK: 2011. 2011, Improving Health and Lives: Durham. ↩

-

Krahn, G. and M.H. Fox, Health disparities of adults with intellectual disabilities: What do we know? What do we do? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 2014. 27: Pages 431 to 446. ↩

-

Programme, L.d.m.r., The Learning Disabilities Mortality Review (LeDeR) Programme December 2017. 2018, Norah Fry Research Centre University of Bristol: Bristol. ↩

-

Commission, D.R., Equal Treatment - Closing the Gap. 2006, Disability Rights Commission: London. ↩

-

Government, H., The Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2010. 2008. ↩

-

Hatton, C., H. Roberts, and S. Baines, Reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities in England 2010: A national survey of NHS Trusts. 2011, Improving Health and Lives Learning Disabilities Observatory. ↩

-

Michael, J., Healthcare for All: Report of the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities. 2008, Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities: London. ↩

-

Tuffrey-Wijne, I., and others., The barriers to and enablers of providing reasonably adjusted health services to people with intellectual disabilities in acute hospitals: evidence from a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 2014. 4(4). ↩

-

MacArthur, J., and others Making reasonable and achievable adjustments: the contributions of learning disability liaison nurses in ‘Getting it right’ for people with learning disabilities receiving general hospitals care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2015. 71(7): Pages 1552 to 1563. ↩

-

Commission, C.Q., Raising standards, putting people first: Our strategy for 2013 to 2016. 2013, Care Quality Commission: London. ↩

-

Baines, S. and C. Hatton, CQC inspection reports of NHS trusts: How do they address the needs of people with learning disabilities? An interim analysis. 2015, Public Health England: London. ↩

-

Health, D.o., Mental Capacity Act. 2005, HMSO: London. ↩

-

Health, D.o., Think Autism: fulfilling and rewarding lives, the strategy for adults with autism in England: an update. Statutory guidance link: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/adult-autism-strategy-statutory-guidance 2014, HM Government: London. ↩