Exploring small traders' attitudes towards the Single Trade Window

Published 21 July 2022

Qualitative research with small traders to explore their attitudes towards the Single Trade Window.

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) Research Report 674.

Research conducted by Kantar Public between 2nd of February and 16th of March 2022. Prepared by Kantar Public (Emily Fu and Lucy Joyce) for HMRC.

Disclaimer: The views in this report are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of HMRC.

1. Executive Summary

The UK Government has committed to developing a Single Trade Window (STW), to simplify and streamline trader interactions with border agencies. A UK STW has the potential to provide a single data portal into which traders and those acting on behalf of traders can submit data once to government in a standardised format, to fulfil all import, export, and transit related regulatory requirements. Research was needed to understand small traders’ views of the STW and how it might affect the way they trade. Views were sought on potential features of the STW, including options for self-declaration, pre-population, multi-filing and sharing supply chain data with government.

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) commissioned independent research agency Kantar Public to conduct qualitative research with small traders. Interviews were conducted with 57 small businesses who imported or exported goods to or from the UK. The sample included a mix of business sizes (though all traders had under 50 employees), a mix of intermediary use for declarations, as well as patterns and frequency of trade. Interviews lasted 45 to 60 minutes and were conducted by telephone or videocall, between 2 February and 15 March 2022. This research was conducted in addition to a Discussion Paper on policy proposals for the Single Trade Window, which was published on GOV.UK to seek views from a wide range of stakeholders (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-single-trade-window-discussion-paper/uk-single-trade-window-policy-discussion-paper).

Key findings

The concept of the STW was well received by small traders, who were keen to see streamlining of the current system. The views of traders towards STW were influenced by the following considerations:

- understanding of Customs is varied. Those with the least knowledge were often unaware that declarations are a part of the Customs process, that it is something they were paying someone else for and something they could potentially do themselves. For these traders, the decision to outsource declarations was not necessarily a conscious one.

- traders with some knowledge of import and export declarations tended to feel overwhelmed by what they regarded as a highly complex process. Due to their unfamiliarity with the process and requirements, or low confidence, these traders often felt their time could be better spent elsewhere in the business and therefore regarded the cost of outsourcing declarations to be good value. For them, outsourcing currently avoided hassle and reduced the risk of errors, which would lead to consignments being delayed. Despite low reported knowledge, however, traders were often collecting a fair amount of declaration data themselves (e.g., commodity codes), and sometimes underestimated how much they knew.

- a small number of those traders interviewed completed and submitted declarations themselves using commercial software. Traders in this group had usually accessed some kind of training through HMRC or their carrier, and once they had learnt the system, found it relatively straightforward to complete and submit declarations themselves.

- while not all traders would be (immediately) affected by the single point of entry and data sharing between government departments (because they were only engaging with HMRC), those who were affected felt that reduced duplication would be very beneficial.

Trader views on self-declaration, pre-population, multi-filing and the linking of supply chain data

Self-declaration, pre-population, multi-filing, and linking supply chain data with government systems are potential functionalities of the STW. See Appendix A for definitions of the functionalities as given to respondents.

Self-declaration was seen as a good idea, though it did not appeal to all traders in the same way. Interest was based on a consideration of whether the benefits outweighed what they often assumed would be a fairly significant time investment to learn the system:

- those completing declaration documentation in-house were the most likely to recognise the benefits to their business; they were motivated primarily by the opportunity to be more in control of their imports and exports and to reduce their costs. These traders sometimes thought that self-declaration could eventually increase their international trade.

- businesses with smaller margins, who were confident dealing with Customs processes, were interested to test whether self-declaration would save them time or money. They were also motivated by greater control, cost-savings, and the ability to see all their declarations and documentation in one place.

- those trading small volumes or exclusively using Fast Parcel Operators perceived self-declaration could represent duplication rather than simplification, so traders in this group felt they were unlikely to use a self-declaration service as it may not suit their business or their skill set. To use self-declaration, these traders would need to be convinced that it simplified the process to such an extent that it made it worth their while to invest time understanding the process.

Once launched, traders felt they would need support from HMRC and other sources to use self-declaration, particularly in the early stages. They would value simple guides tailored to non-experts, searchable guidance, a telephone helpline and face to face seminars and webinars.

Pre-population was widely appealing as something that could save time and reduce duplication. On the other hand, multi-filing was less well-received: most traders tended to see more risks than benefits and felt that this feature reduced control and simplicity.

There were mixed views about linking supply chain data with government systems to improve automation. While supply chain data integration could lead to some push back, integration with other systems was an important benefit that larger small businesses (20 to 49 employees) were keen to see.

Summary of key take-outs

The research with small traders highlighted several ideas to feed into the design of the STW:

- without some education for small traders, there is a risk that they misunderstand the STW and self-declaration, and what that would mean for them in practice.

- for those not already completing and submitting declarations in-house, the benefits of self-declaration were regarded as moderate. Traders who are willing to trial self-declaration to see if they save time or money are likely to be less motivated to try a service that is not free of charge.

- though self-declaration may offer traders more control and potential cost savings, research suggested it also potentially reduces their access to a problem solver at the border, and an expert on the phone. These are highly valued roles that businesses acting on behalf of traders fulfil, given the risk of delays and the importance of reliability.

- to increase interest in self-declaration, pre-population could show traders that functionality in the STW could help make declarations faster over time.

- if multi-filing is included, traders would like it to be optional, with submissions labelled by author, with price and supplier information masked where possible.

- traders believed the ability to integrate self-declaration systems with trader and carrier software could reduce duplication of data entry to government and their carrier, and therefore would be highly appealing to small traders who already use software.

- the complexity of the requirements and the available guidance has been a key driver of outsourcing. Small traders would like straightforward and simple language in guidance that is produced for the STW.

2. Introduction

2.1 Background

The UK Government has committed to developing a Single Trade Window (STW), to simplify and streamline trader interactions with border agencies.

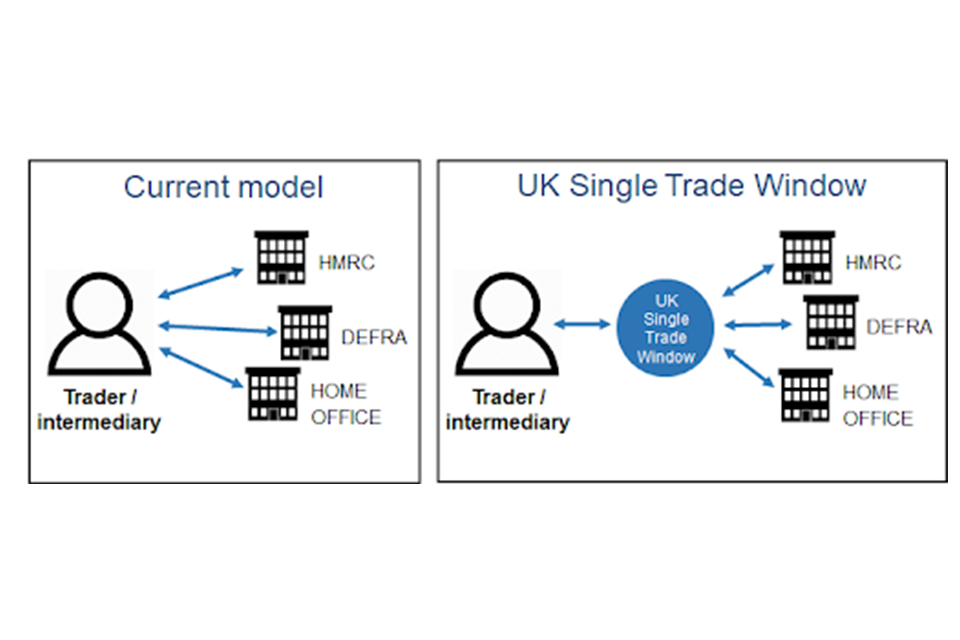

Currently there are multiple government systems which are involved in moving goods across the UK border. Traders and those acting on their behalf submit data to each system as required, with some of this data being duplicative, creating complexity and cost for border users.

A UK STW will provide a single data portal into which traders and those acting on their behalf can submit data once to government in a standardised format, to fulfil all import, export, and transit related regulatory requirements, such as safety and security requirements. The onus would be on government to facilitate data sharing amongst border authorities and agencies to receive the information they need. As part of this, government will also review the guidance available for border users to ensure that is easily accessible and more tailored to the needs of users.

The aims of the STW are to reduce administrative burdens, allow for better data sharing amongst government agencies and ultimately to reduce costs of importing and exporting for businesses.

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) commissioned independent research agency Kantar Public to conduct research to understand small traders’ views of the STW and how it might affect the way they import and export. Views were sought on potential features of the STW, including:

- self-declaration through a portal, for some or all Customs requirements

- pre-population

- multi-filing

- linking supply chain data with government systems (see definitions of these in Appendix A).

This research was conducted in addition to a Discussion Paper on policy proposals for the Single Trade Window, which was published on GOV.UK to seek views from a wide range of stakeholders.

2.2 Research aims

The aim of the research was to capture the response of small traders to the proposed STW, including any barriers and enablers to its use.

The specific research questions included:

- what are traders’ overall thoughts towards proposals for a STW?

- what are the perceived benefits/ drawbacks of a STW?

- what are traders’ thoughts on sharing data across numerous government departments?

- would traders use the STW to self-declare?

- What would influence their decision?

- would the availability of the STW influence the extent to which traders undertake cross border trade?

- To what extent do traders have the knowledge required to utilise a proposed STW?

- Where knowledge is lacking, would the potential benefits of a STW encourage traders to upskill or invest in staff?

- what support would traders need from government in order to use a STW to complete their import or export declarations?

2.3 Method

Sample

The sample comprised 57 small traders with under 50 employees who imported or exported goods to or from the UK. The respondent was someone in the business with an understanding of how the business made import and export decisions.

Traders were recruited from two sources: 29 were recruited from respondents of the HMRC Trader Survey who had given permission to be re-contacted, and 28 were recruited through free-find methods. All respondents were screened using a questionnaire to understand their trading patterns. See Appendix B for the achieved sample frame.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork was conducted between 2 February and 15 March 2022. Interviews lasted 45 to 60 minutes and were conducted via telephone (43) or video call (14) according to respondent preference. Respondents were given an incentive of £100 as a thank you for their time. Respondents were sent a one page ‘pre-read’ before the interview, introducing the STW (see Appendix A).

Analysis

Interviews were recorded with respondent consent. Researchers made notes during the interview, and later completed an analysis matrix based on their notes and the recording of the interview. The analysis matrix was structured by key questions in the topic guide. Researchers also took part in two researcher analysis sessions, exploring emerging themes and hypotheses across the interviews.

Reporting notes

Verbatim quotes are included throughout to illustrate findings, as follows:

“Quote.”

(Size by employee number, Import/Export, Trading pattern, Use of intermediary)

Trading pattern includes three categories:

- EU: those who trade mostly with the EU

- RoW: those who trade mostly with the Rest of the World (RoW)

- EU and RoW: those who trade with EU and RoW

Use of intermediary includes three categories:

- In-house: those who complete and submit all their declarations themselves

- Partly in-house: those who complete and submit part of their declarations themselves

- Uses intermediary: those who use a business to act on their behalf for all their declarations

3. Findings

3.1 Trading context

Interviews initially explored the context for trade to understand trader priorities and expectations for the future, as well as the current level and relative importance of administrative burden. Traders described several challenges for import and export activity in the current climate. These included (from most to least common):

- delays: traders described long and often unexplained delays to shipments, as well as variable and unpredictable lead times

- rising cost of moving goods: traders noted a steep rise in global shipping costs, on top of fees and duties that may have been recently introduced

- difficulty keeping abreast of complex requirements: businesses trading with the EU had often struggled to engage with and understand the changing requirements

- variable carrier service quality: traders described often having to rectify mistakes made by businesses acting on their behalf, with some trading with the EU struggling to find quality hauliers or shippers willing to work with them

- the cost of returns: linked to the high costs of shipping, traders often complained of the difficulty and cost of customers returning goods, as duties and shipping costs could not be recouped

- damaged goods: not all traders had faith that their goods would arrive in good condition and had noticed an increase in their goods arriving broken, damaged or wet

Traders felt that the issues they were encountering were due to the impact of COVID-19 on the shipping sector and the effects of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, or a combination of both. While delays had reportedly reduced (in length and frequency) and costs had been starting to fall in recent months, challenges had not been fully resolved. In addition, towards the end of the fieldwork period, traders expressed apprehension about the Russia-Ukraine war and the impact this could have on international trading conditions and the economy.

“The main obstacle is that things take longer than they used to, it’s the combination of availability of ships and just slight delays at Customs post Brexit.”

(10-19, Import and export, EU and RoW, Partly in-house)

The ways in which traders had responded to recent challenges varied but ranged from those who had significantly reduced or stopped trade with markets where they could no longer be competitive, to those that had made changes to their business to continue trading. While some traders had slightly adapted their trading patterns to manage costs, for example, importing less frequently and in larger quantities, others had forged new relationships with carriers or suppliers or upskilled their workforce to enable business to continue.

Given the current trading environment, traders’ main priority when moving goods in or out of the UK was reliability, in other words, ensuring that their goods arrive and that they do so in a timely fashion. Traders were very keen to avoid goods getting held up or returned. Secondary to this was cost. Small traders were interested in reducing the cost of import and export, though the importance of cost was moderated by the fact that traders often passed on the costs of shipping to their customers. Traders were also interested in reducing complexity where possible, as shipping, Customs and duties were often regarded as difficult to understand. In contrast, administrative burden was rarely mentioned as a concern. Traders regarded it as more important to dedicate the time required to avoid mistakes and risk delays to consignments than to save costs.

3.2 Managing declarations

Interviews explored how traders had in the past made decisions about whether to complete and submit import and export declarations in-house or whether to outsource them to someone else. However, traders using someone else to act on their behalf often had not made an active decision to outsource. This was due to a high degree of variation in engagement with and visibility of the Customs process. The spectrum of traders’ knowledge can be typified by the following three groups:

- ‘Unaware outsourcers’: traders who had only partial awareness of Customs processes, who did not differentiate it from shipping more broadly

- ‘Conscious outsourcers’: traders who may have tried to self-declare, and who have decided to outsource

- ‘Declaring in-house’: traders who had learnt the system and were self-declaring (making declarations using third party software)

Unaware outsourcers

‘Unaware outsourcers’ had the lowest knowledge of Customs processes, and as a result they were often unaware that they were paying someone else to complete declarations on their behalf, or that declaring in-house was a potential option. This group of traders was easily confused by the language of Customs, and often would mistakenly believe they were self-declaring if they were completing any forms that included any information related to Customs (e.g. submitting commodity codes to their shipper). The actions of those acting on their behalf at the border were not transparent for these traders, though they had rarely considered it prior to the research interview. ‘Unaware outsourcers’ tended to be using Fast Parcel Operators and trading in smaller goods. Their perception that Customs is part of shipping was in part because businesses acting on behalf of others (especially Fast Parcel Operators) rarely itemised fees for declarations on invoices.

Conscious outsourcers

‘Conscious outsourcers’ were more likely to recognise declarations as part of the Customs process, though had judged (or assumed) it to be too difficult or too much hassle to do themselves. This group of traders had often conducted initial research into completing and submitting import or export declarations themselves and had been overwhelmed by what they perceived to be a very complex process. Impressions of complexity came from the requirements themselves, the language used to describe them (regarded as ‘jargon’-heavy) and the perceived opacity of the available guidance. Though ‘conscious outsourcers’ often did not progress past the research stage, a handful of traders interviewed had tried completing and submitting import or export declarations themselves, but had concluded that it was too difficult or time-consuming, and that their time could be more valuably spent elsewhere in the business. This group was more likely to be aware of the cost of outsourcing declarations, having seen it itemised on invoices, and reported paying between £40 and £70 per declaration.

Reasons for outsourcing related mainly to the perception that declaring in-house would be too much hassle, or too difficult to learn (particularly among sole traders and businesses with under 10 employees) compared to the low volume or frequency of international trade. In addition, traders were nervous about making mistakes which could lead to delays or penalties from HMRC. Traders often had developed good relationships with their agents and were wary of disrupting a process that was working smoothly. Crucially, traders valued having an expert at the port who could help clear goods quickly on their behalf.

“I simply don’t understand it and I don’t understand the guidance that’s been issued either because there are terms that I don’t know and to work out what those terms mean, you just get sent to other guidance and find yourself going round and round in circles, so I just hand it all over to the broker and hope that they know what they’re doing.”

(Sole Trader, Import, EU, Uses intermediary)

Declaring in-house

Somewhat rare among small traders, those ‘Declaring in-house’ had invested time to learn how the system worked and were submitting declarations themselves. The learning process was often described as difficult, though sometimes traders had made use of HMRC or carrier-run training programs, which they felt were invaluable. Once they had learnt the system, declarations were regarded as relatively straight forward, though could still be time-consuming. The motivations for declaring in-house related to a desire for control, a wish to understand the system (and to understand and minimise any mistakes) and to a lesser extent, to save money (though this group was often unaware of the actual cost to outsource). This group tended to have the closest grasp on how long they spend on declarations and Customs processes.

“We’d rather do it ourselves, it’s not a money issue, but when you run your own business, it’s kind of your baby, so you want to be involved in everything.”

(1-9, Import and export, EU and RoW, In-house)

3.3 General impressions of the STW

Overall, reactions to the concept of the STW were positive. Traders felt it had the potential to provide much needed simplification of the system, that it was logical and in line with what they would expect from a modern service, and that reduced duplication was a benefit for businesses. Those declaring in-house were particularly positive about the changes and were eager to know when the UK STW would launch.

“Why wouldn’t they standardise everything and put it on one platform?”

(10-19, Import, EU and RoW, Uses intermediary)

Beyond an overall positive impression that the STW sounded like a good idea and a positive step, traders had limited detailed feedback about the concept of the STW, because most traders interviewed were not engaging currently with the Home Office, Defra or other agencies (and were unaware they might need to in future). However, businesses in certain sectors (e.g. agriculture and fishing) or who were trading in controlled goods (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/exporting-controlled-goods-after-eu-exit#controlled-goods) expressed strong interest in reducing duplication and streamlining engagement with government. At the same time, traders expressed some scepticism about data sharing between government departments.

3.4 Responses to self-declaration

Self-declaration under the STW refers to the option to self-complete a wider range of import or export declarations via an online tool developed by Government. This would mean that all declarations (import, export, licenses and authorisations) could be made directly to Government, without the need for third party software or businesses acting on their behalf. Customs intermediaries and software providers would still be an option for businesses to use – these options would sit alongside the government tool. See Appendix A for more detail on how self-declaration was introduced to respondents.

Whether traders would consider using a self-declaration service varied and ultimately depended on whether they felt the benefits outweighed the time investment required to learn how to use the system:

- over half of those interviewed said they were interested in using a self-declaration system. Traders expected they would try it out a few times and determine whether it would save them time or money. Those already declaring in-house were much more motivated to use the system

- a sub-set of traders (smaller in size, those who only used Fast Parcel Operators and those with lower confidence) felt they were unlikely or very unlikely to use a government self-declaration service

- while all traders said they wanted to reserve full judgement until they actually tried the system themselves, a small proportion felt they could not decide whether it was something they could consider using without seeing it first

The main motivation for using a self-declaration system was that it would give businesses a greater feeling of control over their imports and exports. This was particularly the case among those who had experienced issues with their carriers, as carriers were often also completing declarations (with a few exceptions of traders using dedicated Customs agents). Traders were also interested in reducing costs. Therefore, if the self-declaration service was not free to use, it is unlikely that the less motivated traders would use it. Though it was difficult for traders to judge the impact on time and administrative burden, overall traders hoped that self-declaration would lead to moderate time savings and that the process would speed up once they had learnt how to use it. However, ease and the sense of control over mistakes were prioritised over cost- and time-saving. Commonly, businesses were relying on manual systems to record shipping information, so the opportunity to have all their declarations and documentation in one place on an accessible system, was also appealing to traders. Finally, a number of traders mentioned the benefits of learning a new skill, and the potential for the self-declaration system to improve Customs compliance across their sector.

“It would be an extremely simple process for me and that would reduce my costs, it might take me a bit longer but I would have control over it so would be much happier.”

(Sole Trader, Import, EU, Uses intermediary)

“If I can log in and see all my imports associated with my EORI number, in one place - see how the VAT was processed… Currently I log it all in Excel and check each one.”

(Sole Trader, Import, EU, Uses intermediary)

There were several factors that traders said would make them more likely to use the self-declaration system. The most important was simplicity. It was regarded as very important for the system to be streamlined and user-friendly, and for accompanying guidance to be clear and easy to understand. Traders commonly suggested that some leniency for mistakes during the initial period of the system going live would be reassuring, given the high likelihood of errors being made by traders trying it for the first time. It was also important to traders that the system was secure. Finally, traders who had very complex movements, and had invested in purchasing or finance systems, or used their freight forwarder or haulier’s system, reported that it was imperative that systems could be integrated to the self-declaration portal. Without this they would not be interested in self-declaration, as it would translate into additional data entry.

Traders highlighted features that would increase the appeal of self-declaration, that went beyond the basics. These included a ‘look-up’ function for commodity codes, the ability to link directly to a business VAT account, the ability to ‘save’ a declaration form and return to it later and as much automation as possible. Traders often spontaneously suggested pre-population (or a similar function) before this was introduced in interviews.

Barriers to using a government self-declaration system mirrored the reasons for outsourcing described in section 3.2 but were also because the current system traders had in place worked well. Traders mainly using Fast Parcel Operators, or those who had good relationships with the businesses acting on their behalf often saw no motivation to change their processes. For some, entering data into a self-serve system was perceived to add an additional layer of work to each trade, which they currently rely on others acting on their behalf to do for them. The outsourcing of this completing and submitting of declarations was often seen as good value for money. Another important barrier to self-declaration was scale. Those who imported or exported infrequently and at smaller scales showed less immediate interest. As discussed, less confident traders were, due to their unfamiliarity with the process and requirements, fearful of making mistakes, and strongly preferred to rely on experts for official activities.

“It’s far better and safer to leave it to an expert. The freight forwarder has someone who’s specifically trained to do these declarations and if there’s a problem you refer them to the freight forwarder and you don’t have to worry.”

(1-9, Import, EU, Uses intermediary)

“If I’m using a carrier [where] I’ve got to put information into a system anyway, if I’ve then got to go to a second system to put in the Customs information and declaration, then it’s adding to the workload and complexity for me, not decreasing it.”

(1-9, Import, EU and RoW, Uses intermediary)

3.5 Support needed

There were several sources of support that traders expected to access to self-declare via the STW. It was most important for official guidance to be very simple and written for non-experts. Traders wanted a ‘Dummies’ guide’ to using the system, written in simple language and with simple 3 to 5 step guides. Traders wanted guidance to be searchable, and for the declaration forms within the system to have explanations hyperlinked to each term (or each field).

Traders were also keen to see a dedicated helpline available for support, as well as online webinars, or face to face seminars for those who were less confident. These kinds of support were expected to be enhanced during the initial launch, and to taper off over time.

“I would always like a phone number of somebody in that area of government who can answer the simple, silly questions that you just can’t get.”

(Sole Trader, Import, EU, Uses intermediary)

In addition to seeking support from HMRC, traders expected to contact their accountant, shippers or Customs agents for advice. Similar to the support accessed for other tax affairs, traders said they would look for YouTube videos and blogs about the topic.

It should be noted that although reported knowledge about Customs was relatively low among traders who used others to act on their behalf, they were often gathering a fair amount of information themselves, including commodity codes, EORI numbers, weights, and sometimes country of origin. The amount of information gathered appeared to vary between businesses acting on behalf of others. This suggests that some traders may be better prepared for self-declaration activities than they might assume.

3.6 Responses to pre-population

Pre-population, the function of auto-filling declaration data from previous declarations, other government data sources, or data submitted by others in the supply chain (see Appendix A for more detail on how it was explained), was well received by traders as it was seen to simplify self-declarations. Traders interviewed were often relying on repetitive manual data entry, so welcomed opportunities to streamline and speed up this process. This was particularly the case among businesses with repeatable imports or exports, who imagined that they may be able to reduce their time to 15 to 20 minutes per declaration. Traders suggested that ‘template’ declarations could be produced that were specific to individual suppliers or clients, i.e. that specific products would be associated with particular suppliers or clients, which could appear automatically. They also wanted the option to switch off the function or reject the suggestion as necessary.

“It sounds like a great tool and could be time saving - you’d be shifting to checking information rather than inputting it from the beginning.”

(10-19, Import and export, EU and RoW, Uses intermediary)

While a handful of traders (generally those who were unlikely to consider using a self-declaration service) were worried that pre-population could make them complacent, on the whole traders were happy to check the pre-populated data each time, and believed that the reduction of manual data entry would lead to an overall reduction in human error. To help encourage checking, traders suggested that prompts could be built into the system to remind them that all data should be verified.

Traders rarely expressed concerns about security, or the accuracy of data pulled from previous declarations or documentation or from other government data sources. However, they occasionally raised concerns about the use of data entered by others in the supply chain. These are explored further in discussion of trader responses to multi-filing.

Though traders’ decision to use self-declaration would be primarily determined by other factors (such as business size and confidence), if pre-population were included in the system, traders felt it would be more attractive, and they would be more likely to start and then continue to use a self-declaration system, as declarations became easier over time.

3.7 Responses to multi-filing

Multi-filing, or the feature for multiple actors involved in a trade to input information to the same declaration form (with one organisation being responsible for accuracy and timely submission) elicited mixed views, and traders had concerns about the involvement of multiple actors.

The key issue was in the idea of traders being reliant on others to complete actions in order for them to progress a shipment. Negating the perceived benefits of self-declaration, multi-filing was seen to remove control from the trader, and leave them at risk of being let down by others, with little time to fill in any incomplete information. Further, traders expressed concern about the delineation of responsibility between different actors in the supply chain, and felt it could be a source of tension if errors were made. Traders suggested that the portal could record and timestamp who had entered what data, to help those responsible for the declaration to query submissions.

“This sends some alarm bells going for me – it’s setting itself up for delays.”

(1-9, Import and export, EU, Partly in-house)

Another issue related to whether others in the supply chain would be able and motivated to submit data to declaration forms. Traders questioned whether all their supply chain would have the digital literacy, digital access and English language ability to engage with the self-declaration portal. In addition, as forms in English were unlikely to fulfil local export needs, importers were wary of asking their suppliers to complete two sets of documentation. Traders also voiced concerns that businesses acting on their behalf were likely to charge them to participate in multi-filing, thereby reducing cost-savings of self-declaration. Finally, traders were worried about commercially sensitive data being visible to others in the supply chain. Specifically, they did not want competitors to have access to costs or to be able to see who their suppliers were. There was some anecdotal feedback that hauliers and businesses acting on behalf of others had shared such commercially sensitive information with competitors in the past.

Despite these concerns, traders who had established good relationships with their carriers and suppliers tended to be more positive about multi-filing, and thought it would save them time. They felt the idea was logical and would save them from chasing others (or being chased) for information.

“The manufacturers and shippers are experts…and they do it repeatedly and so you can trust what they put on the paperwork.”

(1-9, Import, EU, Uses intermediary)

In spite of some interested traders, overall multi-filing did not have a strong appeal and on balance would have a neutral impact on likelihood of using self-declaration.

3.8 Responses to sharing supply chain data

Traders were asked whether they would be willing to grant access to government to their supply chain data, to further automate Customs processes (see Appendix A for the definition as given to respondents). There was a clear split in terms of trader responses.

One group of traders expressed concerns about sharing data with HMRC, either because they thought HMRC might misunderstand the data and then incorrectly tax or penalise them, or because they worried that sensitive supplier or cost information could be compromised. Universally, this group expressed discomfort with the principle of providing HMRC access to their systems, and this was usually linked to their attitudes towards giving government access to data without their control. Some of these businesses were keen that any data sharing that did take place was proportional and limited to that required to reduce admin burdens.

“The supply chain is something you’ve put a lot of work into over the years and…a lot of trial and error goes into that so you might not want competing businesses to have that and have that advantage.”

(1-9, Export, EU and RoW, In-house)

“In practice, I wouldn’t mind, it would make no difference. But in principle, it seems a bit ‘Big Brother-ish’. They don’t need to know every paperclip that is being acquired.”

(1-9, Import and export, EU, Uses intermediary)

The other group saw no issue with sharing data with HMRC, feeling that HMRC already had or could ask for most of the data. Traders in this group did not feel that their supply chain data was particularly sensitive.

“When you run a business, the government, HMRC, they pretty much know everything you’re going to do anyway.”

(1-9, Import, EU and RoW, Uses intermediary)

On the whole, traders who had digitised some elements of the supply chain tended to be happier to share supply chain data with HMRC. However, traders in the sample rarely had software solutions for either supply chain or inventory management system, due to the high cost of the software and the small scale of the business. Due to the small scale of the business, traders often did not see the value of using the software to share data with others in the supply chain, either because it was an additional (paid for) service, data sensitivity, or it was seen as not worth the hassle.

As few businesses had software, Utility Trade Networks (UTNs; see Appendix A for the definition as given to respondents) were not relevant for most traders in the sample. Those who it was discussed with had not heard of supply chains that met the description of UTNs before, but thought that it sounded positive. Traders felt the following factors were important for them to consider using a UTN:

- excellent data security

- the system was streamlined and efficient

- users could be selective about the data they shared

- it was appealing to enough developers to gain traction

3.9 Key findings and conclusions

The STW was well received by small traders, who were keen to see simplification and streamlining of the current system. While not all traders would be affected by the single point of entry and data sharing between government departments, those who are affected felt it was a positive move and that reduced duplication would be very beneficial.

Knowledge about Customs processes was very varied among traders, who did not always know that declarations take place, that it is something they were paying someone else for and something they could potentially do themselves. The research suggested that small traders will likely require some education to be fully prepared for using STW and self-declaration, and understand what they would mean for traders in practice. For example, traders who are already collecting a lot of information may underestimate what they know, and overestimate what businesses acting on behalf of others are doing for them. Traders with the lowest knowledge may dismiss communications about the STW, or believe they are already self-declaring and attempt to do so without an awareness of the requirements.

Self-declaration did not appeal to all traders in the same way. Interest was based on a consideration of whether the benefits outweigh what traders assumed would be a fairly significant time investment:

- those doing things in-house are most likely to see the benefits. They are more motivated, and sometimes think it could increase trade

- those trading small volumes or using Fast Parcel Operators perceived self-declaration could be duplication rather than simplification, and so felt it was unlikely that they were going to use a self-declaration service as it may not suit their business or their skill set. These traders would need to be convinced that self-declaration simplified the process to such an extent that it made it worth their while to invest time understanding the process

- businesses with smaller margins, who are confident dealing with official processes, were interested to test whether self-declaration would save them time or money. This group is likely to be less motivated to trial a declaration service that is not free of charge, as they may be quite sensitive to impact on time and cost saving, as well as early experiences

Though self-declaration offered traders more control and potential cost savings, it also potentially reduces their access to a problem solver at the border, and an expert on the phone which are highly valued roles that businesses acting on behalf of traders fulfil, given the pervasiveness of delays and the importance of reliability. For this reason, simple and accessible guidance will be important, particularly in the early stages.

As a key driver of outsourcing declarations has been the complexity of the requirements and available guidance, simplifying the language used and the guidance as far as possible could enable more small traders to self-serve with confidence.

Pre-population was widely appealing as something that could save time and reduce duplication. To improve interest in self-declaration, examples of pre-population could show traders that the functionality in the STW could help make declarations faster over time. On the other hand, multi-filing was less well-received: most traders tended to see more risks than benefits and felt that this feature reduced control and simplicity. Small traders may be interested in being able to switch off this feature, and to have access limited to relevant information only and submissions labelled by author.

There were mixed views about linking supply chain data with government systems to improve automation. Reassurances about the security of price and supplier information could help reassure some traders, though discomfort with sharing data was usually informed by wider attitudes towards government access to data. While supply chain data integration could lead to some push back, integration with other systems would be an important benefit that certain businesses (typically those with 20 to 49 employees) were keen to see. It may be that small traders struggle to recognise the benefits of automation until they have already digitised some of their systems.

4. Appendix A: Stimulus material and definitions

4.1 Stimulus material

The UK Single Trade Window

The UK Government has committed to developing a Single Trade Window, to simplify and streamline trader interactions with border agencies.

Currently there are multiple government systems which are involved in moving goods across the UK border. Traders and intermediaries submit data to each system as required, with some of this data being duplicative. This creates complexity and cost for border users.

A UK Single Trade Window will provide a single data portal into which traders and intermediaries can submit data once to government, to fulfil all import, export, and transit related regulatory requirements.

- The trader or intermediary would submit data once through a single portal, rather than to multiple border authorities or agencies, through multiple portals.

- This would result in reduced duplication of data entry for users.

- All border data would be submitted in a standardised format.

-

The onus would be on government to facilitate data sharing amongst border authorities and agencies to receive the information they need.

-

As part of this, Government will also review the guidance available for border users to ensure that is easily accessible and more tailored to the needs of users.

The aims of the Single Trade Window are to reduce administrative burdens, allow for better data sharing amongst government agencies and ultimately to reduce costs of importing and exporting for businesses.

Many Customs administrations such as Singapore, Sweden, the USA and New Zealand already have a Single Trade Window in place, with more in development worldwide, including the EU.

We want to engage with stakeholders in this early design stage to understand how we can achieve the best outcomes for traders and the UK and ensure views and implications are fully understood.

4.2 Definitions

Self-Declaration

“Currently, traders can do some declarations for free directly into government systems (such as export declarations) without using an agent or commercial software, but not others (such as import declarations). One option we are exploring as part of the Single Trade Window is to also include self-completion for a wider range of Customs declarations. Government could develop an online tool for traders to make a broader range, or all, of the Customs declarations required to move goods into or out of the UK. This would mean that all declarations (Customs, licenses and authorisations) could be made directly to Government, without the need for software/third parties.

Those using the self-declaration system would need to have a sound understanding of Customs requirements such as commodity codes and Rules of Origin. However, Customs intermediaries and software providers would still be an option for businesses to use – these options would sit alongside the government tool.”

Pre-Population

“One idea for a way to reduce administrative burden is to pre-populate the forms from data elsewhere. This means that information could be automatically filled in, having been pulled from other government data sources, earlier declarations, or from data submitted by other actors in the supply chain. So for example, traders completing forms through the STW would see some of the data they need to input already pre-populated with information they have given previously. If they complete multiple declarations, any fields that are the same across different forms would be automatically prepopulated. Also, the next time they log in to the system, they could choose to do a similar trade to last time, meaning many of the fields will be prepopulated with the data used last time.”

Multi-Filing

“Another idea is something called multi-filing, which is where multiple organisations involved in a trade would input information into the same declaration form, rather than one organisation chasing them all for information. For example, traders, carriers and intermediaries could each directly add relevant information into the same form. One organisation would still have responsibility for the accuracy of data and timeliness of submission.”

Utility Trade Network

“A Utility Trade Network is a secure digital network which traders, and other parties in the supply chain can use to manage transactions and agreements between them. Such networks could reduce the cost of transactions through information being held in a quickly and easily transferable, albeit secure digital environment (where the data being shared can be controlled to protect commercially sensitive information). This would improve trust between businesses as a variety of other counterparties using the network will be able to automatically corroborate the information an individual business provides.”

Sharing Supply Chain Data

“The final idea we want to discuss is the option for traders to grant access to government to their supply chain data. This could support automated Customs and other border processes, and a reduction in manually inputting the data at different steps in the supply chain.”

5. Appendix B: Sample table

The final sample for this project by each of the target quotas is provided below:

| Quotas | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business size | Sole traders | 12 | ||

| Micro businesses (1-9 employees) | 24 | |||

| Small-Smaller businesses (10-19 employees) | 10 | |||

| Small-Larger businesses (20-49 employees) | 11 | |||

| Use of intermediary | Complete declarations in-house (i.e. do not use an intermediary)* | 8 | ||

| Sometimes use an intermediary, sometimes manage in-house | 5 | |||

| Always use an intermediary for declarations (e.g. Customs agent, haulier, freight forwarder, FPO)** | 44 | |||

| Trading pattern | Trade mainly with EU | 29 | ||

| Trade mainly with the Rest of the World (RoW) | 5 | |||

| Trade with EU and RoW | 23 | |||

| Type of trading | Mainly import | 26 | ||

| Mainly export | 10 | |||

| Both import and export | 21 | |||

| Sector | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 5 | ||

| Manufacturing | 12 | |||

| Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles | 30 | |||

| Construction | 3 | |||

| Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | 1 | |||

| Other | 6 | |||

| Frequency of trade | More than once a week | 10 | ||

| Weekly or fortnightly | 19 | |||

| Monthly | 15 | |||

| Less often / seasonal / ad hoc | 13 | |||

| Controlled goods | Trade standard goods only | 47 | ||

| Trade controlled goods only | 3 | |||

| Trade both standard and controlled goods | 7 | |||

| Last time traded | Have exported/imported in the last 6 months | 51 | ||

| Have exported/imported more than 6 months ago but less than 12 months ago | 2 | |||

| Have exported/imported more than 12 months ago but less than 2 years ago | 3 | |||

| Have exported/imported in the past but not in the last 2 years | 1 |

*13 of this group initially said that they conducted declarations ‘in-house’ – however, researchers discovered during the depth interviews that they in fact used an intermediary, and later re-allocated.

**It should be noted that knowledge of Customs declarations was very variable among those using intermediaries. While some knew very little, some traders were relatively familiar with and collected most information that is submitted on declarations forms (despite feeling that they were not ‘experts’).