Summary report

Published 22 October 2019

Introduction

This infographic summarises a quantitative study which explores how and why women’s and men’s career paths change after having children.

There is a large body of international evidence showing that women with children suffer large pay penalties and that taking time out of the labour force or returning to work part-time may be damaging for career progression.

Using data from Understanding Society for 2009 to 2010 to 2016 to 2017, this study considers the extent to which women, by opting out of employment, moving to part-time work or to jobs with lower occupational status, ‘downgrade’ their careers following childbirth.

1. Differences in working patterns after children

Mothers are more likely to withdraw from full-time employment compared to men after having children

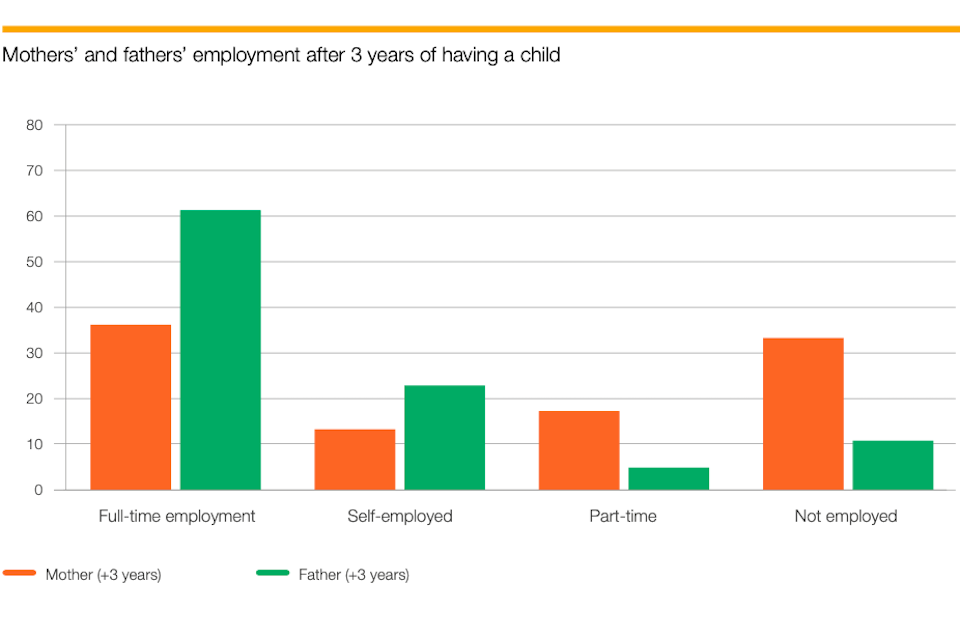

Figure 1: Mothers’ and fathers’ employment after 3 years of having a child

The chart shows that men were much more likely than women to be in full-time employment or self-employed 3 years after having a child. Women were more likely than men to be in part-time employment or not employed.

There are large differences in male and female employment paths in the years after childbirth – while mothers are more likely to withdraw from full-time employment over time, fathers typically remain in full-time work.

Employers need to ensure that mothers have the opportunity to access and continue full-time roles which can support their parental care responsibilities. Fathers equally need to be supported in accessing more flexible work opportunities.

2. Differences in career paths

For women who do return to work after having children their career path often gets stuck

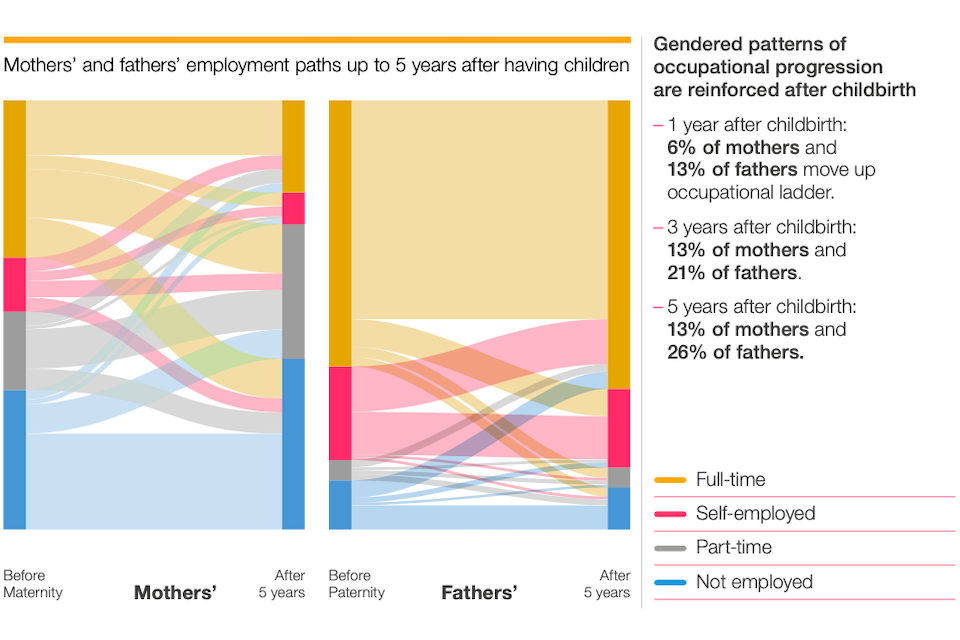

Figure 2: Mothers’ and fathers’ employment paths up to 5 years after having children

The chart shows that men were much more likely than women to be in full-time employment before having children, and to stay in full-time employment up to 5 years after having children. Women were more likely to change a full-time working pattern to either part time or not employed.

Gendered patterns of occupational progression are reinforced after childbirth

1 year after childbirth, 6% of mothers and 13% of fathers move up the occupational ladder.

3 years after childbirth, 13% of mothers and 21% of fathers move up the occupational ladder.

5 years after childbirth, 13% of mothers and 26% of fathers move up the occupational ladder.

Occupational change is a gradual process which takes place three to five years after birth rather than straight away. Women almost always return to a job with the same occupational status as the one they left.

Over time it is not occupational downgrading but rather a lower chance of getting promotion that slows down mothers’ progression.

Employers need to focus on ensuring long-term support for parents in the workplace is in place so that employees have equal opportunities to progress.

3. Upgrading or downgrading with a new or same employer

Women working with the same employer are more likely to remain in the same level of job (and less likely to progress or downgrade in the occupational ladder)

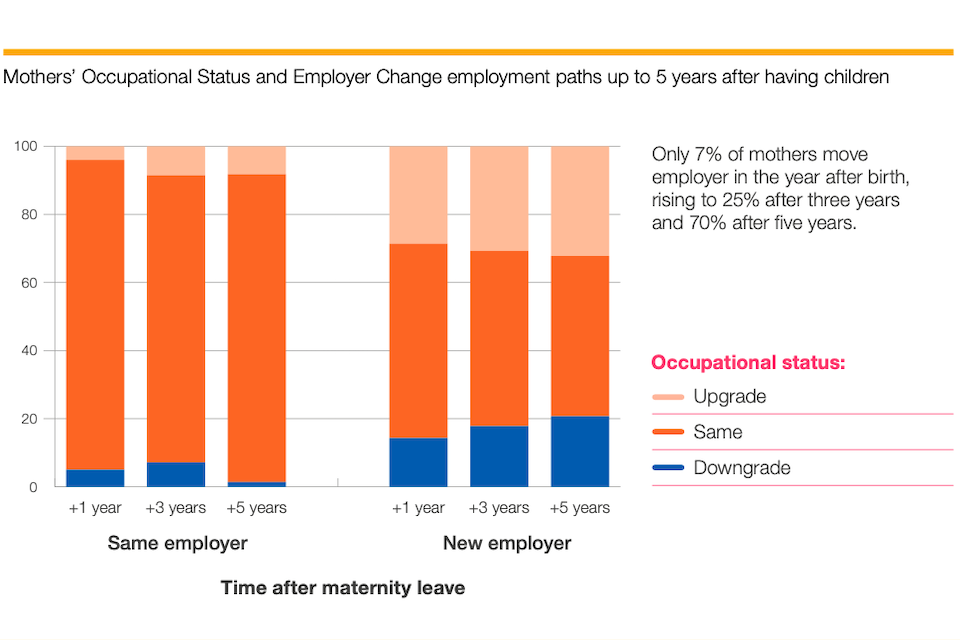

Figure 3: Mothers’ ‘occupational status’ and ‘employer change’ employment paths up to 5 years after having children

The chart shows that women who stayed with the same employer generally stayed at the same occupational status. Women who moved to a new employer were generally more likely to upgrade their occupational status than downgrade it.

Only 7% of mothers move employer in the year after birth, rising to 25% after three years and 70% after five years.

For women – but not for men - staying with the same employer is associated with their career stalling. Those who go back to work with the same employer face both a lower risk of occupational downgrading, but are also much less likely to progress to higher paid occupations (upgrading).

Women might be more likely to move organisations in order to access progression. To improve retention of female employees, it’s important to provide support to parents and carers and facilitate progression.

For support with this, some guidance is available on Family Friendly Policies: actions for employers.

4. Differences between sectors

Women working in certain sectors are also more likely to remain in the same level of job (and less likely to progress or downgrade in the occupational ladder)

Women working in the public, education and health sectors, are more likely to stay at the same level after having children but with lower chances of career progression.

Employers in the public sector, education and health sector need to ensure that their family-friendly policies are complemented and supported by effective career development for women returning to work so that they have the same opportunities for progression and development support as men.

5. Occupational downgrading

Women who take a break after maternity leave more often downgrade to a lower paid job

For women that move back into work after a break in employment – even if short – there is a high risk of occupational downgrading.

It’s important to provide high-quality support to female employees who wish to return to work following maternity leave, both before and after the baby is born.

For support with this, some guidance is available on Family Friendly Policies: actions for employers.

6. Differences in employment and earning patterns

Gendered labour market patterns tend to be reinforced in the years following childbirth as employment and earning patterns diverge in favour of men

Table: Couples’ working patterns before and after childbirth

| Working pattern | Before birth | 3 years after birth |

|---|---|---|

| Both partners employed full-time | 43% | 23% |

| Man employed full-time, woman employed part-time | 20% | 30% |

| Man employed full-time, woman out of labour force | 19% | 27% |

| Both out of labour force | 7% | 8% |

| Other arrangements | 11% | 12% |

Table: Couples’ earning patterns before and after childbirth

| Earning pattern | Before birth | 3 years after birth |

|---|---|---|

| Sole male earner | 21% | 32% |

| Male breadwinner | 34% | 37% |

| Equal shares | 31% | 20% |

| Female breadwinner | 12% | 11% |

| Sole female earner | 2% | 0% |

Definitions: Male or female breadwinner is defined as one of the partners earning more than 60% of head and spouse joint earnings (gross). Equal shares are defined if each of the partners brings 40 to 60% of joint earnings. Sole male earner households are couples where the woman’s earnings contribute 0% of the joint earnings and sole female earners are equivalently defined

Among couples where both partners For support with this some worked full-time before birth, women guidance is available here. are more likely to work part-time or leave employment completely after having children with the man continuing to work full-time.

Similarly among couples where the man was the main earner before birth, the man is more likely to become the sole earner or breadwinner in the 3 years after having children.

Employers need to help encourage staff to think about all the options for sharing care responsibilities so that male and female employees have equal opportunity to balance their work with care.

This can be done by providing clear and easy to understand information on your family-friendly policies and ensuring that line managers are able to discuss these with expectant parents as early as possible.

For support with this, some guidance is available on Family Friendly Policies: actions for employers.