Volunteering Futures Fund evaluation: feasibility study

Published 10 January 2023

Key terms and definitions

Table 1.1 describes how key terms have been used throughout the report.

Table 1.1: Key report terms and definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Arts Council England (ACE) | Delivery partner responsible for delivering the majority of the fund (£4.65 million) for arts, culture, heritage and sport initiatives involving volunteers. |

| Delivery partners | There are 3 delivery partners in this programme: Arts Council England (ACE), Pears Foundation and NHS Charities Together (NHSCT). They are responsible for choosing the grantees, distributing the funds, and monitoring grantees. |

| Programme | Refers to the Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF) programme encompassing all projects under the 3 delivery partners. |

| Projects | VFF funded activities carried out by each grantee. |

| Grantees | The collective term for organisations receiving a grant under the VFF programme to deliver a project. |

| Lead grantee | The organisation receiving the grant as named lead organisation. Often working with partner organisations to deliver the project. |

| Partners | Organisation working alongside the lead grantee to deliver the project or an element of a project. |

| Formal volunteering approaches | This is defined by the DCMS Community Life Survey as: giving unpaid help to groups or clubs, for example, leading a group, administrative support or befriending or mentoring people. |

| Informal volunteering approaches | This is defined by the DCMS Community Life Survey as: giving unpaid help to individuals who are not a relative. For example, babysitting or caring for children, keeping in touch with someone who has difficulty getting out and about, or helping with household tasks such as cleaning, laundry or shopping. |

| Modality of the volunteering opportunity | Referring to the categorisation of volunteering opportunities offered by projects such as digital, micro, flexible and other formal opportunities. |

| Digital volunteering approaches | This includes digital volunteering activities that take place remotely or in person. |

| Micro volunteering approaches | Volunteering to do specific time-bound tasks that can be undertaken as a one-off (e.g., collecting or delivering groceries, doing an errand, making telephone calls or giving someone a lift). |

| Flexible volunteering approaches | The ability to help by offering your services as a volunteer as and when it suits with no regular pattern of commitment or a minimum stipulated number of hours each week. |

| Beneficiaries | People and organisations who benefit from the VFF programme. This includes the volunteers, organisations delivering projects and their staff members, and the service users of the projects. |

| Volunteer retention | The ability for the organisations involved to retain their volunteers for the expected period of volunteering. |

| Common Minimum Dataset (CMD) | The minimum set of variables that all VFF funded projects must collect data on. This is then aggregated to report programme level data against these variables. |

| Data Form | A form produced by the programme level external evaluator which outlines key areas that all VFF funded projects must report data against. |

| Realist evaluation | An evaluation based on the assumption that the same intervention will not work everywhere and for everyone focusing on “what works, for whom, under what circumstances and how” (Pawson and Tilley, 2004). |

Executive summary

In 2021, DCMS launched the £7 million Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF). This is a new fund aiming to support high quality volunteering opportunities for young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering. It aims to test and trial solutions to known barriers using micro, flexible and digital approaches (see Table 1.1. for definitions). The fund is delivered through 3 delivery partners: Arts Council England (ACE), Pears Foundation and NHS Charities Together (NHSCT). ACE will deliver £4.65 million of grants, the majority of the fund.

The overarching objective of the fund is to improve the accessibility of volunteering, particularly amongst young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering (e.g., those in communities where it is harder to volunteer, those who experience loneliness, those with disabilities and those from ethnic minority backgrounds). DCMS is interested in learning about the comparative effectiveness of different volunteering models and recruitment approaches for engaging and sustaining volunteers.

NatCen Social Research and RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM) have been appointed by DCMS to develop evidence-based options for a robust and fully independent evaluation. This evaluation will examine the extent to which the VFF has met its overarching objectives. This report considers the information available about the fund, its grantees and expected beneficiaries. It draws on this information to suggest feasible impact evaluation options. The options considered focus on ACE funded projects only, which are at the set-up phase of their projects. Pears Foundation and NHSCT projects were not considered for an impact evaluation as they started project delivery earlier than ACE projects and have already set up their data collection processes.

Outcomes of interest for the evaluation:

The Theory of Change (ToC) identified key outcomes of interest that sit at 2 levels, organisational and individual. These are:

Organisational level:

-

more diverse pool of volunteers (including younger volunteers, those from ethnic minorities, with disabilities and others facing barriers to volunteering)

-

increases in volunteering opportunities in areas of high deprivation

-

increased volunteering recruitment and retention (although the primary focus is on diversification of volunteers to increase the pipeline of volunteers)

Individual level:

- outcomes of reduced loneliness, increased wellbeing, building of social connections and skills for volunteers

Methodology

To scope what is feasible for the evaluation the following key activities took place:

-

inception meeting and consultations with DCMS and the delivery partners to better understand the feasibility and challenges of data collection

-

desk review of relevant background documentation including the business case for the programme, grant agreements with delivery partners and project proposals

-

grantee level discussions with lead grantees (and partners where possible), to gather information on existing data collection processes and explore what data collection could be feasible in the future

-

discussions with non-funded applicants to scope the feasibility of unsuccessful applicants forming a counterfactual group for the impact evaluation

-

further development of the existing Theory of Change based on information from the desk review, consultations, and discussions with grantees

As part of the first phase of the evaluation (activities carried out from January to May 2022), a Data Form was developed to provide a standardised approach for collecting monitoring data from Pears and NHSCT grantees and form a common minimum dataset (CMD). This will need to be updated for the ACE projects if it is to form part of the key data sources for the programme evaluation. Interviews were also conducted with a small number of volunteers[footnote 1] from NHSCT projects to produce volunteer journey maps, and an early learnings workshop was held for Pears and NHSCT projects. Learnings from this initial evaluation activity fed into the recommendations for phase 2 of the evaluation.

Evaluation design options

DCMS wants the overarching evaluation of the programme which runs until 2024 to include the following core elements:

A process evaluation: evaluating how the whole programme was designed and delivered, including lessons learned

Volunteer journey mapping with volunteers involved in the programme: to help understand the volunteer journey, and key stages and decision points to create a fuller picture of the points of friction which may impact on the quality or length of the volunteering experience

Impact evaluation: to design an impact evaluation of the ACE strand of the fund, assessing the opportunity to recruit comparison groups with adequate sample sizes. It is hoped that this would involve a quasi-experimental method if feasible. This report outlines the viability and limitations of an impact evaluation, focusing on the ACE projects only.

Provision for learning about different approaches taken by funded initiatives across the fund: this may include facilitated workshops and/or deliberative events to aid the wider evaluation aims, but with a view to sharing learning with grantees.

The main body of this report details what is feasible for the impact evaluation, with other elements of the evaluation (process evaluation, volunteer journey mapping, and provision of learning) outlined in Annex 3.

Impact evaluation

Different impact evaluation designs were assessed for ACE projects to establish the most suitable impact evaluation (IE) design. We considered the strengths and limitations of different IE methods.

The IE should consider the following questions:

-

What impact did the VFF have on outcomes for volunteers (i.e., is there a link between volunteering and improved wellbeing, reduced loneliness, increased feelings of community connectedness and improvement in skills)?

-

What impact did the VFF have on outcomes for organisations (i.e., to what extent organisations increased volunteer recruitment and retention, and increased the diversity of volunteers recruited)?

-

How did impact vary by volunteering opportunity?

-

How did impacts vary for different groups of volunteers (i.e., young people and those with disabilities)?

There are 3 overarching approaches to undertaking an impact evaluation:

-

Experimental

-

Quasi-experimental

-

Non-experimental designs

Whilst an experimental design offers the most robust approach to impact evaluation, this is not a credible or viable option for the VFF due to how projects (and volunteers) are selected. Participation in the fund cannot be randomised for practical and ethical reasons, as projects are selected based on a set of key criteria, and volunteering opportunities cannot be randomly assigned to some individuals if there are sufficient roles for all individuals that have expressed an interest. As such, this approach has not been assessed. We discuss the feasibility, risks and advantages of quasi-experimental and non-experimental approaches in further detail in the section that follows.

Quasi-experimental designs (QED) aim to construct a credible counterfactual (i.e., a comparator group of similar individuals or organisations). It seeks to identify the impact of the programme by comparing the outcomes of those receiving the programme to the comparator group that is similar to those in the programme in terms of their baseline characteristics. Quasi-experiments include those that use a comparator group, and those who do not use one. There are several considerations required as part of designing a quasi-experimental evaluation. These include the following:

- determination of the outcome(s) of interest to the quasi-experimental impact evaluation; including analysis of whether the outcome(s) of interest are measurable and tangible using quantitative metrics and how long into the programme they will be realised

- considerations for data availability including baseline and post-programme data and data that will allow us to establish a potential counterfactual

- assessment on whether a comparison group could be identified, and what group that might be

- assess suitability of design against the resources, budget and timescales available

Several challenges were identified for undertaking a QED for assessing impact of the VFF against the above considerations:

Organisational level outcomes:

Availability of data on organisational level outcomes (diversification of volunteers). All ACE projects are delivered through partnerships. Each partner holds different levels of historic data on volunteer demographics. Baseline data on volunteer demographics will exist for only a subset of ACE projects or subset of partners within each project. None of the grantees have previously collected data on the number of first-time volunteers they are working with. Therefore, it would not be possible to tell if volunteer pools became more diverse and whether this was attributable to the VFF programme.

Comparison groups/data sources available: We considered two sources of data as potential counterfactuals for organisational level outcomes: (a). the use of large-scale national surveys and (b), non-funded applicants that applied for ACE funding through the VFF.

a) The use of large-scale surveys was not considered to be a viable option for constructing a counterfactual for VFF funded activities. We considered the possibility of comparing changes in the proportion of individuals that formally volunteer in the East of England (which is the only region that does not have targeted VFF activity) compared to the other regions in which VFF activity takes place. However, challenges with this approach include contamination (3 of the ACE projects have a national focus) and possible dilution of impact (the majority of VFF projects have a more geographically focused approach, e.g., at postcode level, towns, and specific boroughs).

b) Non-funded ACE applicants could form a potential counterfactual group for a subset of funded projects. This could be viable if non-funded applicants could be identified that collect quantitative data on volunteer demographics, have capacity to share this data and operate in similar areas to the selected ACE projects. To identify if any non-funded ACE applicants meet these criteria, further scoping is needed in the form of interviews with all non-funded applicants. There is a risk that even if suitable projects are identified, they may obtain funding for their project from elsewhere at any point during the evaluation, which would remove their suitability as a counterfactual because it will not be possible to isolate the impact of VFF funding.

Individual level outcomes:

-

Availability of data on individual volunteer level outcomes (wellbeing, loneliness, social connectedness, skills). There is varied capacity across grantees to collect quantitative individual level data on outcomes. Several grantees also indicated that collecting baseline survey data against the volunteer outcomes of interest at the point of recruitment of volunteers is not appropriate as it may deter potential volunteers, e.g., collecting data on volunteers’ levels of loneliness may be considered intrusive. It also increases the length of forms that need to be completed prior to onboarding, which can deter potential volunteers. However, it may be possible to collect this information after initial onboarding to overcome this challenge. Only 5 grantees indicated with certainty that a pre- and post- quantitative assessment of outcomes would be possible, but post measurement was considered more feasible. Each project also has different outcomes of interest for its volunteers, based on the focus of its interventions.

-

Comparison groups/data sources available: We did not identify suitable counterfactual options for individual volunteer level outcomes of improved wellbeing, reduction in loneliness, building of social connections and skills development. The impact of volunteering on these outcomes can be measured through pre and post approaches, as part of non-experimental designs.

Non-experimental designs: Given the challenges of QED, a theory-based impact evaluation (TBE) could be used to assess how the programme has contributed to any changes that are observed and what other factors may have impacted outcomes, using contribution analysis. Contribution analysis is a structured method to test theories about how a particular outcome arose. Evidence collected is used either to confirm or discount any alternative explanations.

Contribution analysis draws on quantitative and qualitative data and other evidence, which is triangulated to inform the assessment. Contribution analysis can help to come to reasonably robust conclusions about the contribution made by the programme to observed results (Mayne, 2008).

Quantitative evidence could include:

-

project level reported data requested in the Data Form

-

individual level survey data where it is collected by grantees.

Qualitative data could include:

-

interviews with grantees and volunteers.

-

volunteer journey mapping

Some of this data collection has been proposed as part of the process evaluation approach, outlined in Annex 3.

7 ACE projects indicated they planned to commission an external evaluation of their project, and a further 3 indicated they would conduct an internal evaluation of their project. Whilst the exact nature of the evaluations is still to be determined for each project, the extent of this activity will range from project staff collecting information for ongoing learning and adaptation to use of an external consultant or agency that will collect data and produce a final report. The robustness of data collected for each project level evaluation will vary. This information can be drawn upon and incorporated into the theory-based approach which will build a ‘contribution story’ using several sources of data. A procedure would need to be put in place to indicate the strength of the evidence underpinning the evaluation based on 2 criteria: (1) reliability of data sources; and (2) extent of triangulation between data sources. Triangulation of data with a variety of methods will reduce the risk of systematic biases due to a specific source or method.

There are options (Table 1.2) to vary the level of support provided by the programme external evaluator to support the generation and use of this data.

Table 1.2: Options for evaluator support for project collected data

| Option | Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support level | Provide a framework which outlines the key outcomes of interest for the programme evaluation, and some approaches for data collection against these, e.g. validated survey questions. | In addition to providing a framework, provision of additional quality assurance and support to projects and their evaluators at design stage. | In addition to providing a framework and support at design stage, conduct analysis of the raw data collected by projects and their evaluators. |

| Considerations | This approach allows for reporting on the key outcomes of interest for a subset of projects per outcome, without requiring collection of data that is not suitable for some projects. Data would be collected, analysed, and reported by grantees/project evaluator. The programme level evaluator would aggregate the findings by theme and report alongside their primary data collection. | This would help improve the quality of the data collected and aggregated for reporting at programme level and improve the ability to comment on robustness of the data. However, analysis of the data would ultimately be with the grantees/project evaluator. | This would allow for analysis to be more aligned for reporting at programme level, and more detailed exploration of the data. This would also further improve the ability to comment on robustness of the data. This approach requires building in additional data sharing agreements and processes with grantees and their volunteers to allow record level data to be shared with the programme level evaluator. |

| Evaluation scope | Process evaluation (including volunteer journey maps), learning workshops, theory-based impact evaluation with low support approach for project collected data. | Process evaluation (including volunteer journey maps), learning workshops, theory-based impact evaluation with medium support approach for project collected data. | Process evaluation (including volunteer journey maps), learning workshops, theory-based impact evaluation with high support approach for project collected data. |

Learning workshops: It would also be beneficial to facilitate ongoing learning across projects through learning workshops. These would offer the opportunity for grantees to share what is working well and not so well, facilitate group learning and building of links between organisations. This could take place quarterly or biannually to balance the resources required to facilitate and attend these sessions, and the value to grantees.

Grantees expressed an interest to take part in future learning workshops to connect with other grantees to share learning and reflections.

Recommended approach:

Our recommended approach, based on our assessment of what is feasible, is to conduct a process and theory-based impact evaluation. The level of support provided for project level collected data to feed into the evaluation (low, medium or high) is to be determined by DCMS.

The evaluation activity could take place across September 2022 to March 2024, with an interim report scheduled in March/April 2023, and a final report in March/April 2024 to cover the full 2 years of ACE funding. Alternatively the evaluation could take place across September 2022 to October 2023, with an interim report in March 2023 and a final report in October 2023 to provide earlier insights.

Lessons learned for designing future programmes:

To make a quasi-experimental evaluation approach feasible, the following potential approaches could have been taken:

Organisational level outcomes:

-

The programme could have been designed to only accept applications from projects that had good quality organisational level historic data on their volunteer demographics across all partners. This would have allowed for a larger pool of projects with robust quantitative evidence on how the outcomes of interest (volunteer diversity) were changing over time, and to allow comparison to other non-funded organisations.

-

The programme could have funded more geographically focused projects, concentrating activity within a few regions. This would have allowed for comparison using large scale national surveys such as the annual DCMS Community Life Survey (CLS),[^2] which includes data on the number and type of people formally volunteering, broken down by gender, age, ethnicity, disability, and region. Changes in volunteering rates could have been compared for project focused regions and non-project regions.

Volunteer level outcomes:

Funding projects run by organisations with existing systems and capacity to collect survey data across their volunteers would have also strengthened pre- and post-data on volunteer level outcomes (wellbeing, loneliness, social connection and skills) to feed into a theory-based impact evaluation. However, the same challenges would have applied to finding a suitable group of matched non-volunteers, making a quasi-experimental approach unsuitable for these outcomes. To overcome the challenges of matching volunteers, a stepped wedge approach[footnote 3] could have been applied in the form of waiting lists for volunteers. However, this relies on several conditions: a) there are enough interested volunteers to form a waiting list b) being put on a waiting list is not a deterrent for potential volunteers and does not result in individuals dropping out prior to the opportunity becoming active and c) those willing to wait to volunteer do not materially differ from those that receive immediate volunteering opportunities. We did not think these conditions could be met, therefore concluded it was unsuitable.

Whilst some of the approaches described above would have allowed the programme to be evaluated in a more statistically robust way to assess impact, the authors feel it may have limited the impact of and learning from the programme in other ways. For example, smaller more innovative organisations and approaches may have been excluded from the funding, and learnings around what works may not have been widely applicable or suitable for organisations with less resources or robust data systems in place.

1. Introduction and background

NatCen Social Research and RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM) have been appointed by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) to deliver phase 1 of the evaluation of the Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF). As part of this work, the project team has been tasked with developing evidence-based options for a robust and independent evaluation that will examine the extent to which the VFF has met its overarching funding objectives.

1.1 Purpose of this report

This report presents the information about the fund, its grantees and expected beneficiaries, and uses this as a basis to suggest feasible evaluation. The options for an impact evaluation focus solely on projects funded by Arts Council England (ACE), which are at the set-up phase. Pears Foundation and NHS Charities Together (NHSCT) projects were not considered for an impact evaluation as they started project delivery several months earlier than ACE projects and had already set up their data collection processes.

This report includes details of proposed evaluation methodologies including the extent of data collection and reporting that is feasible under each, roles and responsibilities of the evaluator, lead grantee and partners, assumptions made, and risks identified for each suggested approach. It also outlines suggested deliverables and timelines for the evaluation, which will build on work already completed across February to May 2022. Further refinement of the selected approach will be required as part of the setup of phase 2 of the evaluation.

1.2 Background of the fund

In 2021, DCMS launched the VFF, a £7 million fund which aims to support high quality volunteering opportunities for young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering. It aims to test and trial solutions to known barriers using micro, flexible and digital approaches. The fund is delivered through 2 strands:

-

Strand 1: volunteering across arts, culture, heritage, sport, civil society, and youth initiatives. This is delivered by ACE, that awarded £4.65 million of VFF funds across 19 projects which will run until March 2024.

-

Strand 2: community and youth initiatives involving volunteers. Match-funded and delivered by Pears Foundation and NHS Charities Together (NHSCT). DCMS total funding of £1.17 million to be spent by March 2023 with the equal match funding element spent by 2024:

- Pears Foundation (£550,000) across 6 projects.

- NHS Charities Together (£624,000) across 14 projects.

The overarching objectives of the fund include:

- improving the accessibility of volunteering, particularly amongst young people[footnote 4] and those who experience barriers to volunteering (i.e., volunteering rates tend to be lower amongst those who experience loneliness, those with disabilities and those from ethnic minority backgrounds)[footnote 5]

- increasing the skills, wellbeing, and social networks of volunteers, and reducing levels of loneliness

- encouraging and exploring innovation and scaling of volunteering practices that may have emerged during the pandemic

- learning about the comparative effectiveness of different volunteering models (i.e., flexible, micro, and digital volunteering opportunities) and recruitment approaches for engaging and sustaining volunteers

- strengthening volunteer pipelines in DCMS sectors and widen participation in, engagement with and access to arts, culture, sport and heritage activities and places

- leveraging additional investment towards volunteering initiatives through a match funding challenge

1.3 Evaluation requirements

DCMS has indicated that the overarching evaluation of the programme should include the following elements:

A process evaluation: evaluating how the whole programme was designed and delivered. For example, did the funding reach the intended grantees? What factors may have hindered these objectives? What worked well, less well, and what lessons could be learned for future interventions?

Volunteer journey mapping to be carried out with volunteers involved in the programme: to help understand the volunteer journey, and key stages and decision points to create a fuller picture of the points of friction which may impact on the quality or length of the volunteering experience.

Impact evaluation: to design a focussed impact evaluation into the ACE strand of the fund to assess which interventions led to a change in the outcomes of interest, including forming a comparison group that is large enough to measure impact. It is hoped that this would involve a quasi-experimental method, as the comparison group cannot be selected randomly. This report assesses the feasibility of a quasi-experimental impact evaluation of this programme.

Provision for learning about different approaches taken by funded initiatives across the fund: this may include facilitated workshops and/or deliberative events to aid the wider evaluation aims, but with a view to sharing learning with beneficiary organisations.

2. Methodology

The following activities were undertaken in phase 1 of the evaluation, and have contributed to scoping what is feasible for phase 2 of the evaluation:

Inception meeting and consultations with DCMS and the lead partners to understand the feasibility and depth of data collection.

Desk review of relevant background documentation including the business case for the programme, grant agreements and project proposals. These sources helped guide a classification matrix (Annex 1) which summarises specific project details across the delivery partners.

Grantee consultations with project and monitoring and evaluation leads to gather information on existing data collection processes and what could be feasible going forward.

Exploratory discussions with non-funded applicants to scope the feasibility of unsuccessful grantees forming a counterfactual group for the impact evaluation.

Further development of the existing Theory of Change based on information from the desk review, consultations and consultations with grantees.

Assessment of counterfactual and alternative evaluation options based on design of the programme, outcomes and impacts of interest and grantee level data collection systems.

In addition to the above, some evaluation activity has already taken place under phase 1 of the evaluation which needs to be factored into the design of phase 2. This is discussed in detail in Annex 2 and includes development of a Data Form for monitoring data to be collected and reported by projects, a small number of interviews with volunteers and an early learning workshop with Pears and NHSCT projects.

3. Theory of Change

3.1 Introduction

The Theory of Change (ToC) reflects how VFF is expected to lead to changes for the organisations and individuals it supports and forms the theoretical basis which will guide the impact evaluation. It provides the overarching framework on what the fund is aiming to achieve and for whom. All subsequent evaluation tools developed (under phase 2) will need to align with this ToC and in particular the key outcomes the fund aims to contribute to.

The VFF provides funding through 3 diverse delivery partners, with different portfolios of projects and beneficiaries.

The following process was carried out by the research team to ensure the ToC was reflective of these different strands:

1. A review of documentation and data relating to the VFF and across the 3 delivery partners, including the initial ToC and project proposals.

2. Calls with all Pears and NHSCT funded grantees, and 18 out of the 19[footnote 6] ACE grantees to better understand their project and targeting of volunteers.

3. ToC workshop with DCMS.

4. Feedback from delivery partners to ensure the draft ToC was reflective of their projects.

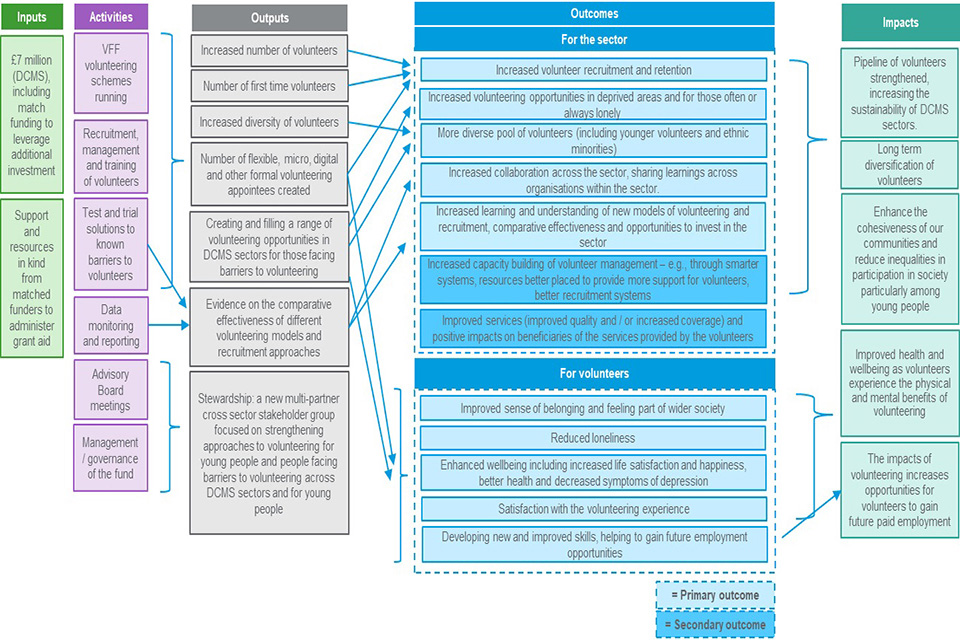

5. Refinement and finalisation of the ToC – presented at Figure 3.1.

For practical reasons volunteers were not consulted as part of the ToC development. However, as part of planned volunteer interviews in phase 2 of the evaluation, feedback will be sought from volunteers on what they hope to get out of their volunteering placement and will be used to update the ToC where appropriate.

3.2 ToC diagram

The ToC diagram outlines the agreed inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes (primary and secondary) and longer-term impacts of the VFF, as well as key linkages between each. These are discussed in more detail throughout this chapter.

Figure 3.1: VFF Theory of Change

3.3 Barriers

The following barriers to volunteering have been identified for volunteers and grantees through one-to-one discussions with lead grantees, DCMS analysis and through the review of previous literature linked to volunteering.

Volunteers

-

Lack of local opportunities to volunteer in certain areas.

-

Limited free time/the ‘right’ free time – may not have availability during the day/weekends which certain opportunities require.

-

Additional support needs – these can include a) Emotional: i.e., lacking confidence and therefore need additional support to initially engage with volunteering opportunities b) Physical or cognitive i.e., because a person has a disability and volunteering activities need to be adapted to enable them to engage or c) Financial – costs associated with volunteering may be prohibitive i.e., travel and subsistence.

-

Language barriers – individuals who don’t speak English as a first language may struggle to engage with the application processes for volunteering and/or the volunteering opportunity depending on the nature of the role.

Grantees

-

Staffing levels – recruiting new volunteers requires additional, dedicated staff time investment at the start and for ongoing support.

-

Recruitment processes – bottlenecks, i.e., training and onboarding requirements.

-

Minimum checks – i.e., NHS volunteering opportunities in hospitals require DBS checks. Volunteers need photographic documentation for this and must go through a number of other checks which may be prohibitive for some groups of individuals who do not have access to the required documentation.

-

COVID-19 – impact on access to potential volunteers, e.g., difficulty accessing schools to recruit young people due to Covid-19 protocols. Impact on the number of volunteering opportunities that may be available. i.e., constraints on permitting volunteers in hospitals.

3.4 Overarching hypotheses for the evaluation

A ToC diagrammatically illustrates how activities undertaken as part of an intervention are expected to lead to changes for beneficiaries. This includes key barriers that such activities are intended to address. It is based on one or more hypotheses, while helping to conceptualise and test whether the hypothesis held true. In short, the ToC sets out the intervention inputs, how funded activities are expected to result in the intended outcomes, and for whom.

The overarching hypothesis for VFF is: ‘Young people and people who face barriers to volunteering take up new volunteering opportunities, build new skills, improve their well-being and broaden their social networks, as organisations’:

-

target diverse groups

-

provide better support

-

offer new ways of volunteering

-

to capture micro, digital and flexible opportunities, but not limited to those

This hypothesis assumes that:

-

new volunteering opportunities with different modalities will be created

-

there will be targeted outreach and support to reach these groups

Provided the above 2 activities take place, young people and people who face barriers to volunteering will take up those opportunities.

This hypothesis reinforces that the primary focus of the programme is to (i) increase the recruitment of first-time volunteers (partly made up of young people and those experiencing barriers to volunteering) through testing different approaches, and (ii) improve skills and wellbeing of volunteers.

Previous research has highlighted that certain groups are less likely to volunteer. Research shows those who live in more deprived areas are less likely to volunteer.[footnote 7] This may be because there are fewer opportunities in these areas. There is a mixed picture when it comes to volunteering levels amongst those from ethnic minority backgrounds.[footnote 8] According to some data sources rates of volunteering were similar for people who were white and people from ethnic minority backgrounds[footnote 9] but others found that as an aggregate, those from ethnic minority backgrounds volunteer less frequently compared to white British counterparts, and lower income ethnic minority groups are even less likely to volunteer.[footnote 10] Volunteering is also less common amongst those aged 25-34 than older age groups.[footnote 11]

The evaluation will test how successful different approaches are in recruiting those less likely to volunteer. It will test the assumption that the creation of a range of volunteering opportunities and modalities can help overcome barriers faced by those who are currently less likely to volunteer. The evaluation will also test which approaches to targeting volunteers result in a more diverse pool of volunteers.

The evaluation will also test the link between volunteering and individual outcomes for volunteers. There is some evidence that volunteering is linked to improved wellbeing, and one of the main mechanisms by which it does that is through improvements in social connections for volunteers. However, the context matters and the opportunity needs to be appropriate for volunteers. Some studies also suggest that healthier people are more likely to get involved in volunteering in the first place.[footnote 12] Volunteering is positively associated with enhanced wellbeing. This includes improved life satisfaction; increased happiness; and decreases in symptoms of depression.[footnote 13] Volunteering can improve social connectedness: giving volunteers a sense of belonging and feeling part of wider society.[footnote 14] There is less evidence directly linking volunteering to reduced loneliness. However, the assumption made is that volunteering reduces loneliness through improvements in wellbeing and building of social connections.

There is also some evidence that volunteering can support skills building and linked to this, improvements in people’s ability to find paid work. An evaluation of Nottingham City Council’s V4ES volunteering programme found that programme participants who were successful in applying for paid work cited the skills, qualifications gained, workplace experience, and confidence/self-esteem as a major factor in their success.[footnote 15]

Taking part in social action, including volunteering, develops a young person’s character and equips them with skills for work and life. This was evidenced by a randomised control trial conducted by the Government’s Behavioural Insights Team into projects funded by the Youth Social Action Fund in 2016. It found significant increases in employability skills and character traits for adulthood such as empathy and cooperation.[footnote 16] The Jubilee Centre’s report, A Habit of Service, also showed that a young person who has participated in social action activities such as volunteering, campaigning, and fundraising in the past year, is more likely to have the time, skills, confidence and opportunity to take part in youth social action in the future.[footnote 17] There is good evidence that volunteers perceive volunteering to have improved their job prospects,[footnote 18] but currently a more limited evidence base regarding whether this perception is correct (i.e. whether it translates to changes in behaviour).

3.5 Beneficiaries

The outputs listed in the ToC diagram are expected to result in outcomes for the following 3 beneficiary groups.

Volunteers: volunteers are expected to be the primary beneficiary group of the fund. They could benefit by having increased access to volunteering opportunities through (i) having more opportunities available and/or (ii) more flexible and accessible opportunities. In turn, volunteering is expected to contribute to improved wellbeing, building of social connections, a reduction in loneliness and improvement in skills.

Grantees and their staff: grantees are expected to benefit in several ways. Recruitment of additional volunteers could improve the overall experience of those using services by complementing the work of staff, e.g., volunteers in hospitals providing additional support to patients such as teaching them how to make calls to relatives directly through their phone or an iPad. However, some grantees indicated that additional volunteers could increase their workload due to onboarding and support services required for volunteers, particularly when recruiting harder to reach groups. i.e., where volunteers have additional support needs. Grantees may also benefit by using programme funds to strengthen organisation wide recruitment systems, improve training material and bring in / onboard new staff. This may have longer-term and more widespread benefits for organisations.

Service users: some grantees ultimately recruit volunteers to support the services being offered to their service users. The assumption is that diversification of volunteers as well as increased numbers of volunteers will ultimately benefit service users. However, this may not always be the case. For example, more flexible volunteering opportunities may result in less commitment and time to service users who require more support.

The evaluation should therefore focus on collecting data on impacts for volunteers as the primary beneficiaries. This includes data on outcomes such as increased opportunities to volunteer for those that face barriers to volunteering, improvements in wellbeing, reduction in feelings of loneliness, building social connections and skills development. Data can also be collected from grantees on how the project was designed and delivered, who was targeted, and any unforeseen consequences for grantees, volunteers, and their service users. Data does not need to be collected directly from service users who are secondary beneficiaries of the programme.

4. Impact evaluation design options

4.1 Impact evaluation design options

DCMS has indicated that the overarching evaluation of the programme which runs until 2024 should aim to include a process evaluation, volunteer journey mapping, an impact evaluation with a quasi-experimental approach if feasible, and provision for learning throughout the evaluation. This section will outline possible approaches for an impact evaluation based on the evidence and insights gathered. Approaches to the process evaluation, volunteer journey mapping and provision of learning workshops are outlined in Annex 3.

We have undertaken a scoping of different impact evaluation designs for ACE projects with the overall aim to establish the most suitable impact evaluation (IE) design. To identify the most suitable approach we have also considered the strengths and limitations of different IE methods.

4.1.1 Scope of the impact evaluation

The assessment of what is possible for an impact evaluation is considered (below) for ACE projects only and informed by conversations with grantees. This is because ACE grantees are in the early stages of setting up their project at the time of writing and will continue delivery of their project until 2024. Pears and NHSCT projects were selected using different criteria, are several months into delivery and will complete delivery of their projects by March 2023.

4.1.2 Research questions

It is critical that the research questions are defined at the outset to design an impact evaluation. The table below outlines the key questions of interest linked to the ToC:

Table 4.1: Key impact evaluation questions

| Impact | |

|---|---|

| 1 | What impact did the VFF have outcomes for volunteers, specifically young people and those who face barriers to volunteering? i.e., is there a link between volunteering and improved wellbeing, reduced loneliness, increased feelings of community connectedness and improvement in skills? |

| 2 | What impact did the VFF have on outcomes for organisations? i.e., to what extent did organisations increase volunteer recruitment and retention, and increase the diversity of volunteers recruited? |

| 3 | How did impact vary by volunteering opportunity? i.e., what was the impact of offering new or different ways of volunteering? |

| 4 | How did impacts vary for different groups of volunteers, specifically those who face barriers to volunteering? i.e., young people and those with disabilities. |

4.1.3 Impact evaluation approaches

There are 3 overarching approaches to undertaking an impact evaluation i.e., experimental, quasi-experimental and non-experimental designs.

Whilst an experimental design offers the most robust approach to impact evaluation, this is not a credible option for the VFF due to how projects (and volunteers) are selected. Participation in the fund cannot be randomised for practical and ethical reasons such as projects are selected based on a set of key criteria, and volunteering opportunities cannot be randomly assigned to some individuals if there are sufficient roles for all individuals that have expressed an interest. There are ethical issues with denying a volunteer the opportunity to participate in the scheme after they have expressed an interest and there are sufficient opportunities available, for both the volunteer which could benefit in a number of ways from the opportunity and the organisation which would value the support received from the volunteer. As such, this approach has not been assessed, and our focus is on the feasibility, risks, and advantages of quasi-experimental and non-experimental approaches.

4.2 Feasibility of quasi-experimental designs to assess impact

Quasi-experimental designs (QED) cover a wide range of approaches including those that use a comparison group (i.e., matched group design; regression discontinuity design) and those that do not use a comparison group (i.e., interrupted time series; single-case designs). The only QED design that has been explored is the use of a matched group design, due to the nature of the interventions delivered by the VFF and the outcomes of interest identified in the ToC.[footnote 19]

4.2.1 Considerations for QED design

There are several considerations required as part of designing a quasi-experimental evaluation. These include the following:

-

Determination of the outcome(s) of interest to the quasi-experimental impact evaluation; including analysis of whether the outcome(s) of interest are measurable and tangible using quantitative metrics and how long into the programme they will be realised.

The outcomes of priority interest sit at 2 levels, organisation and individual.

• Organisational level outcomes: The key organisational level outcomes of interest identified from the ToC and which this study assesses the feasibility of measuring are diversification of the types of volunteers organisations recruit and number of first-time volunteers they bring on board.

• Individual level outcomes: Individual level outcomes include the impact of VFF funded activity on volunteer’s wellbeing, levels of loneliness, social connections and skills. There may be other outcomes which volunteers may identify. -

Considerations for data availability including baseline and post-programme data and data that will allow us to establish a potential counterfactual.

-

Assessment on whether a comparison group could be identified, and what group that might be.

-

Assess suitability of design against the resources available.

4.2.2 Considerations for Data Availability

(a) Organisational-level outcomes:

Diversification of volunteers: Pre- and post-data on volunteer demographics will exist for only a subset of ACE projects or partners that have access to historic data on their volunteer recruitment, as not all partners have historic or complete data on volunteers. Therefore it is not possible to measure diversification of volunteers. Specifically:

-

ACE VFF projects are delivered through partnerships. Each partner holds different levels of historic data on volunteer demographics.

-

Most of the grantees collect data on age, ethnicity and disability. However, it is not known to what extent all partners have collected this information historically. It appears to be inconsistent based on early conversations.[footnote 20]

Number of first-time volunteers: All ACE grantees stated that they had not previously asked their volunteers if they were first time volunteers. This information would be collected for the first time as part of VFF reporting requirements.

(b) Individual level outcomes:

The capacity to collect quantitative individual level data on volunteer loneliness, wellbeing, social connections, and skills development differs across projects. Eleven out of the 18 grantees indicated they had systems to administer surveys to volunteers, had done so in the past or had the capacity to do this for their VFF funded project. However, this capacity did not extend to all the partners in each project.

Several grantees indicated that collecting baseline survey data against the volunteer outcomes of interest at the point of recruitment of volunteers is not appropriate as it may deter potential volunteers, e.g., collecting data on levels of loneliness may be considered intrusive. It also increases the length of forms that need to be completed prior to onboarding, which can deter potential volunteers. However, it may be possible to collect this information after initial onboarding to overcome this challenge. Only 5 grantees indicated with certainty that a pre- and post- quantitative assessment of outcomes would be possible, but post measurement was considered more feasible.

Each project also has different outcomes of interest for their volunteers. The most frequently cited outcome was skills, followed by wellbeing. Some projects were also interested in capturing the impact of volunteering on social connections. Only a small number of projects highlighted they were explicitly targeting individuals who were lonely or at risk of being lonely, and that they had an interest in capturing information linked to this outcome, even though this may be an outcome that occurs in the absence of targeting.

Considering the above, quantitative data on all 4 individual level outcomes will not be systematically available across all ACE projects. However, it will be available for a subset of projects - 5 grantees indicated they planned to or could collect pre- and post-data on some of the outcomes of interest. More projects than this however indicated some post-data could be collected if required.

4.2.3 Assessment on whether a comparison group could be identified

We considered 2 sources of data as potential counterfactuals for organisation level outcomes, discussed in more detail below. No suitable counterfactual options were identified for individual volunteer level outcomes. .

Organisational-level outcomes:

(i) Large scale surveys which collect data on volunteering

Data sources on number and types of people volunteering include the annual DCMS Community Life Survey (CLS)[footnote 21] and Understanding Society longitudinal study. The CLS is a nationally representative annual survey of adults (16+) in England, which collects data on the proportion of individuals that formally volunteer. This is broken down by gender, age, ethnicity, disability, and region.

The only region of England in which VFF projects do not specifically operate is the East of England. We considered the possibility of comparing changes in the proportion of individuals volunteering over time in the East of England compared to the other regions in which VFF activity has been funded. There are several challenges associated with this.

-

Contamination: One challenge is the issue of contamination. 3 of the ACE projects have a national focus which could include some activity in the East of England. Additionally, some projects are focusing their volunteer recruitment activities on certain regions but also using the funding for organisational level strengthening of volunteer recruitment.

-

Detection: Another challenge is the inability to detect impact when looking at high level region data. The CLS only provides data at region level whilst the majority of VFF projects have a more focused approach, e.g., specific boroughs in London. VFF projects may be able to increase numbers of volunteers in certain localised areas or increase diversity in the type of volunteers in their localised areas, but this is likely to be diluted when looking at region level data available in the CLS. In theory, this could be addressed through local area boosts of the CLS, however, this was not considered due to the issue of contamination.

The Understanding Society longitudinal study collects data on the proportion of respondents that volunteer over time. Similar challenges around availability of region level data and ability to detect impact apply in addition to the frequency and timeline of when usable data is available. The fieldwork period for the Understanding Society longitudinal study is 2 years, with the latest wave covering January 2021 to May 2023. ACE projects run from May 2022 to March 2024.

Considering the above challenges, the use of existing large-scale surveys as a potential source for counterfactual data for organisational level outcomes is not feasible for the VFF evaluation.

(ii) Non-funded ACE applicants

Exploratory conversations were undertaken with 3 non-funded ACE applicants, to assess their suitability as a potential comparison group for organisational level outcomes (diversity of volunteers). These are applicants that applied for funding under VFF but were not successful. Several challenges were identified with the use of these projects as a comparison:

-

Absence of quantitative data on volunteer demographics: like some of the funded projects, some non-funded applicants do not collect systematic data on volunteer demographics.

-

Lack of capacity to provide data in the absence of VFF funding: like VFF funded projects, most non-funded applicants were made up of a consortium of partners. Whilst some lead partners could provide information on the type of volunteers recruited by their own organisations, they are unable to do this for other partners who would have been involved in delivery of the volunteering opportunities.

-

Each project (funded and non-funded) works in different locations and has different target groups. For meaningful comparison, ACE funded projects would have to be matched to non-funded applicants with similar characteristics. Additional scoping is required to determine if successful matching is possible. However, given the differences seen between funded projects, we expect a low likelihood of successful matching with non-funded applicants.

-

Confounding factors: some non-funded applicants indicated they planned to obtain funding for their project from other sources, for some or all the proposed activities. Outcomes for these projects could be attributable to other sources of funding.

Non-funded ACE applicants could form a potential counterfactual group for a subset of funded projects if non-funded applicants could be identified which collect quantitative data on volunteer demographics, have capacity to share this data and operate in similar areas to the selected ACE projects.

To identify if any non-funded ACE applicants meet these criteria, further scoping is needed in the form of interviews with all non-funded applicants. There is a risk that even if suitable projects are identified, they may obtain funding for their project from elsewhere at any point during the evaluation, which would remove their suitability as a counterfactual.

Finally, the budget and capacity limitations placed on the study need to be considered before the design is finalised.

4.3 Use of non-experimental design to assess impact

A theory-based evaluation approach could be used to assess how the programme has contributed to any changes that are observed and what other factors may have impacted on outcomes, using contribution analysis. A contribution analysis is a structured method to revising theories about how a particular outcome arose. Evidence collected will be used either to confirm or discount any alternative explanations.

Contribution analysis would draw on both quantitative and qualitative data and evidence, which will be triangulated to inform the assessment. Contribution analysis can help to come to reasonably robust conclusions about the contribution made by the programme to observed results (Mayne, 2008). One consideration is the triangulation of evidence, where a judgement must occur on the number of sources deemed necessary, made on the basis of how important they are to the evaluation.

Quantitative evidence will include project reported data requested in the Data Form and individual level survey data where this is collected by grantees. Qualitative data will include interviews with grantees and volunteers. Some of this data collection has already been proposed as part of the process evaluation and volunteer journey mapping (see Annex 3). A contribution analysis approach would further build on these proposed data collection steps.

Careful consideration of sampling is necessary to ensure that views from all key stakeholders inform the evidence base. Qualitative data collection needs to be carefully planned and targeted to explore key parts of the ToC. Self-attribution bias can be controlled through various approaches, e.g., the evaluation can use interviews which require volunteers to self-attribute success. That is, retrospective or prospective views on perceived outcomes to inform the evidence base. Another approach is to conduct a double-blind interview, where neither the interviewee nor the interviewer has prior information on the ToC, which may unduly influence recall.

4.3.1 Incorporation of project collected evaluation data:

In addition to quantitative data provided against the Data Form through collection of monitoring data, 7 ACE grantees indicated they planned to commission an external evaluation of their project, and a further 3 indicated they would conduct an internal evaluation of their project. Whilst the exact nature of the evaluations is still to be determined by grantees, the extent of this activity will range from project staff collecting information for ongoing learning and adaptation, to use of an external consultant or agency that will collect data and produce a final report. The robustness of data collected for each project level evaluation will vary. This information can be drawn upon and incorporated into the theory-based approach which will build a ‘contribution story’ using several sources of data. A procedure would need to be put in place to indicate the strength of the evidence underpinning the evaluation based on 2 criteria: (1) reliability of data sources; (2) extent of triangulation between data sources. Triangulation of data with a variety of methods will reduce the risk of systematic biases due to a specific source or method.

There are a few possible approaches to supporting the generation and use of this data. The low option provides less certainty about the robustness and quality of data feeding into the contribution analysis whilst the high option provides greater certainty.

a) Low: Provide a framework which outlines the key outcome areas of interest for the programme evaluation, and some approaches for data collection against these. i.e., validated survey questions. This approach allows for reporting on the key outcomes of interest for a subset of projects per outcome, without requiring grantees to collect data that is not suitable for their targeted volunteers for practical or ethical reasons. Data would be collected, analysed and reported by grantees/their evaluator. The programme level evaluator would aggregate the findings by theme and report alongside their primary data collection.

b) Medium: In addition to providing the framework outlined in the low option, the programme level external evaluator would provide additional support to grantees and their evaluators at design stage. This would include support around determining appropriate sample sizes and sampling approaches to minimise bias, and tool construction. This would help improve the quality of the data collected and aggregated for reporting at programme level and improve the ability to comment on robustness of the data. However, analysis of the data would ultimately still sit with the grantees/external evaluator.

c) High: In addition to providing support and quality assurance at design stage, the programme level external evaluator could conduct analysis of the raw data collected. This would allow for analysis to be more aligned for reporting at programme level, and more detailed exploration of the data. This would also further improve the ability to comment on robustness of the data. This approach requires building in additional data sharing agreements and processes with grantees and their volunteers to allow record level data to be shared with the programme level evaluator.

The first steps of a contribution analysis approach have already been completed as part of phase 1 of the evaluation – developing a ToC and identifying steps between activities, outcomes and impacts. Phase 2 of the evaluation could be used to collect and map data and evidence against the ToC, assess the contribution of the VFF to expected outcomes and make an independent, evidence-based judgement on the extent of this contribution. As contribution analysis is an iterative process, data will need to be collected in several steps to test, refine and strengthen the contribution story.

This approach should be underpinned by realist evaluation principles, by exploring the specific causal mechanisms resulting in change as a result of an intervention, whilst accounting for the context within which this change occurs.

This will help provide evidence for “what works, for whom, under what circumstances,” which is a key part of the testing and learning required to understand whether different modalities of volunteering are more effective or beneficial for achieving the desired outcomes. This approach will be able to better explain what factors contribute to success in recruiting first time volunteers and diversification of volunteers across different regions and volunteering models.

A theory-based impact evaluation would also allow information on broader impacts on the organisation to be collected, which may not be as easily quantifiable.

4.4 Evaluation options:

Our recommended approach based on an assessment of what is feasible, is to conduct a process and theory-based impact evaluation.

The level of support provided for project collected data to feed into the evaluation (low, medium or high) is to be determined by DCMS.

Each option provided covers the evaluation period of 2 years, and assumes 2 main reporting outputs, an interim report at the end of year 1 and final report at the end of year 2 of the programme.

As per the hypothesis and ToC, the primary focus of the VFF is to test different ways of bringing in first time volunteers and those facing barriers to volunteering to increase diversity of volunteers. The evaluation should generate learning around what worked (and did not work) and why for wider sharing.

This information can be generated through a process evaluation and mixed-methods theory based impact evaluation, which can unpick the various linkages between activities and outcomes, and test assumptions. The robustness and quality of the project collected data which feeds into the impact evaluation will differ across each project. This can be strengthened by providing additional support to projects for their evaluation. However, this increases the budget required for the evaluation.

4.5 Timeline

We propose the following timelines for the recommended data collection for an evaluation that takes place across the full length of the funding. The majority of ACE projects recruit volunteers on a rolling basis across 2 years therefore the proposed evaluation activity can also be delivered over a shorter timeframe across September 2022 to October 2023, with an interim report in March 2023 and a final report in October 2023 to provide earlier insights.

Table 4.3 Indicative timeline for data collection for phase 2 of the evaluation

| Test and update minimum data form for ACE projects | April-May 2022 |

|---|---|

| Interviews with Pears and NHSCT grantees (Y1 only) and ACE grantees (Y1 and Y2) | Jan-Feb 2023 and Jan-Feb 2024 |

| Volunteer journey mapping | Ongoing |

| Learning workshops | Quarterly/biannually |

| Aggregate data from Data form | Biannually |

| Interim evaluation report | March-April 2023 |

| Final evaluation report | March-April 2024 |

4.6 Lessons learned for designing evaluable future programmes

To make a quasi-experimental evaluation approach feasible, the following potential approaches could have been taken:

(a) Organisational level outcomes:

-

The programme could have been designed to only accept applications from projects that had good quality organisational level historic data on their volunteer demographics across all partners. This would have allowed for a larger pool of projects with robust quantitative evidence on how the outcomes of interest (volunteer diversity) were changing over time, and to allow comparison to other non-funded organisations.

-

The programme could have funded more geographically focused projects, concentrating activity within a few regions. This would have allowed for comparison using large scale national surveys such as the annual DCMS Community Life Survey (CLS), which includes data on number and type of people formally volunteering, broken down by gender, age, ethnicity, disability, and region. Changes in volunteering rates could have been compared for project focused regions and non-project regions.

(b) Volunteer level outcomes:

Funding projects run by organisations with existing systems and capacity to collect survey data across their volunteers would have also strengthened pre- and post-data on volunteer level outcomes (wellbeing, loneliness, social connection and skills) to feed into a theory-based impact evaluation. However, the same challenges would have applied to finding a suitable group of matched non-volunteers, making a quasi-experimental approach unsuitable for these outcomes. To overcome the challenges of matching volunteers, a stepped wedge approach could have been applied in the form of waiting lists for volunteers. However, this relies on several conditions: a) there are enough interested volunteers to form a waiting list b) being put on a waiting list is not a deterrent for potential volunteers and does not result in individuals dropping out prior to the opportunity becoming active and c) those willing to wait to volunteer do not materially differ from those that receive immediate volunteering opportunities.

Whilst some of the approaches described above would have allowed the programme to be evaluated in a more statistically robust way to assess impact, the authors feel it may have limited the impact of and learning from the programme in other ways. For example, smaller more innovative organisations and approaches may have been excluded from the funding, and learnings around what works may not have been widely applicable or suitable for organisations with less resources or robust data systems in place.

Annex 1 – Classification matrix

This section outlines the profile of the grantees, the target beneficiaries and volunteering opportunities across the 3 delivery partners. This information has been used to feed into the assessment of what is feasible for an evaluation of the programme.

Summary of ACE projects

The 19 ACE-funded projects span a range of different focuses and are located across England, with projects located in every region apart from the East of England. In terms of who the projects are targeting, young people are clearly the most targeted group, and many projects are targeting multiple groups of people.

The proposals have severe data gaps in terms of the modality of opportunities being offered by the shortlisted ACE projects, 74% of the projects did not specify what modality of opportunities they were offering. Organisations greatly vary in terms of the number of volunteers they are aiming to involve and the organisation size, highlighting the diversity of the projects being funded by ACE.

In their proposals, grantees were asked to select their focus from a list of 3 outcomes. “Cultural Communities” was the most popular outcome which is defined as “investment in cultural activities and in arts organisations, museums and libraries helps improve lives, regenerate neighbourhoods, support local economies, attract visitors and bring people together”.

Volunteering Opportunity Focus

The largest focus of the projects is Combined Arts (n=10). 3 projects are not discipline specific as their volunteering opportunities do not focus on any particular area.

| Volunteering Focus | Count |

|---|---|

| Museums | 2 |

| Combined Arts | 10 |

| Music | 1 |

| Literature | 2 |

| Libraries | 1 |

| Not Discipline Specific | 3 |

| Total | 19 |

Target volunteer groups

A majority of the shortlisted ACE projects (n=12) are targeting young people. Of the twelve projects targeting young people, the majority are also targeting other groups of volunteers, including ethnic minorities, people with disabilities and those in deprived communities.

4 projects did not mention targeting any groups in their proposals.

| Target Volunteer Groups | Count |

|---|---|

| Young people | 12 |

| Ethnic minorities | 6 |

| Disabled people | 9 |

| LGBTQ+ | 1 |

| Experiencing loneliness | 4 |

| In deprived communities | 7 |

| Other groups | 1 |

| No mention of targeting | 4 |

Modality of Opportunities

Modality of the volunteering opportunities was not a key focus of the ACE projects’ proposals and is an area of focus for future information gathering. Digital opportunities are the most popular type of volunteering opportunity based on this limited data.

| Modality of opportunities | Count |

|---|---|

| Digital | 3 |

| Flexible | 2 |

| Micro | 1 |

| No modality of opportunity stated | 14 |

Number of Volunteers

The number of volunteers targeted in the ACE projects ranges from 28 to 5,607. The median number of volunteers in a project is 400.

Number of volunteers involved in ACE-funded projects – by organisation frequency

Geographical regions

The shortlisted ACE projects are distributed across all regions, apart from in the East of England where no projects are located. The highest number of projects are located in the South East (n=4) and Yorkshire and the Humber (n=4).

| Regions | Count |

|---|---|

| National | 0 |

| North West | 2 |

| North East | 2 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 4 |

| West Midlands | 2 |

| East Midlands | 2 |

| East of England | 0 |

| South West | 1 |

| South East | 4 |

| London | 2 |

| Total | 19 |

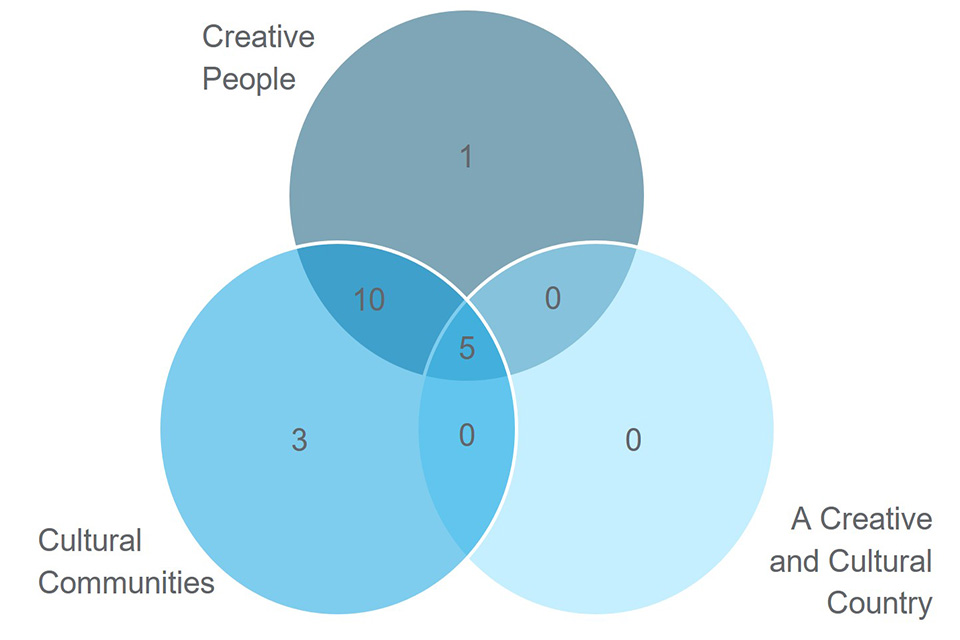

ACE outcomes

ACE set out 3 outcomes in their strategy for their projects: “Creative People”, “Cultural Communities” and “A Creative and Cultural Country”, wanting each of the projects to align with at least one of these outcomes.

The Venn diagram above shows which outcomes projects are addressing. The vast majority (n=18) state “Cultural Communities” as an expected outcome of their project and the least popular outcome is “A Creative and Cultural Country” (n=8).

Summary of NHSCT projects

In comparison with the shortlisted ACE projects, projects funded through NHSCT are much less varied. NHSCT projects only focus on health and social care related opportunities and are predominantly located in 2 regions: London and the West Midlands, with the absence of an NHSCT project in a number of regions in England. Similar to ACE projects, young people are the most targeted volunteer group with 13 out of the 14 NHSCT projects targeting them. The most popular modality for volunteering opportunities is flexible and formal.

Volunteering Opportunity Focus

All volunteering opportunities funded through NHSCT are categorised as health and social care opportunities.

Examples of opportunities include volunteers undertaking befriending roles, undertaking activities with dementia patients and peer-to-peer support for those suffering with their mental health.

Target Volunteer Groups

All but one of the NHSCT projects target young people specifically. A high number of projects are targeting those in deprived communities and people with disabilities.

Examples of other groups projects are targeting include refugees and asylum seekers, NEET groups and those whose vulnerabilities were exacerbated by the pandemic.

| Target Volunteer Groups | Count |

|---|---|

| Young people | 13 |

| Ethnic minorities | 2 |

| Disabled people | 7 |

| LGBTQ+ | 0 |

| Experiencing loneliness or isolation | 2 |

| In deprived communities | 8 |

| Universal / no targeting | 0 |

| No mention of targeting | 0 |

| Other groups | 7 |

Modality of Opportunities

All projects stated at least one modality of their volunteering opportunities, half stated 3 or more types of modality. The most popular modality is flexible and the least popular is micro.

Modality of volunteering opportunity – by organisation frequency

Number of Volunteers

The number of young volunteers involved in the NHSCT projects ranges from 20 to 300 volunteers.

Number of volunteers – by organisation frequency

Geographical regions

The majority of NHSCT projects are in the West Midlands or London (n=5) with lower numbers in the North West, South West and South East. The following regions have no NHSCT projects: North East, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, East of England and National projects.

| Regions | Count |

|---|---|

| National | 0 |

| North West | 2 |

| North East | 0 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 0 |

| West Midlands | 5 |

| East Midlands | 0 |

| East of England | 0 |

| South West | 1 |

| South East | 1 |

| London | 5 |

| Total | 14 |

Summary of Pears projects

Projects funded through Pears are either focused on supporting children and young people or people with disabilities. In terms of geographical locations covered, 4 projects cover numerous locations across England, and 2 are just focused in the South-East and London. There are data gaps for the modality of opportunities being offered and the volunteer groups being targeted by projects. Projects vary greatly in terms of the number of volunteers being supported, ranging from 140 to 2,570.

Volunteering Opportunity Focus

4 Pears projects focus on children and young people and 2 projects focus on people with disabilities. Examples of activities undertaken by volunteers in these projects includes:

-

providing children with one-to-one reading support

-

mentoring primary school aged children

-

virtual buddying with a child, young person or adult with a disability

Target volunteer groups

One of the Pears projects is not targeting any specific volunteer groups. The rest of the projects target the following groups: those experiencing loneliness, living in deprived communities, ethnic minorities and people with learning disabilities.

| Target volunteer groups | Count |

|---|---|

| Young people | 1 |

| Ethnic minorities | 1 |

| Disabled people | 1 |

| LGBTQ+ | 0 |

| Experiencing loneliness or isolation | 2 |

| In deprived communities | 1 |

| Universal / no targeting | 0 |

| No mention of targeting | 1 |

| Other groups | 0 |

Modality of opportunities

The modality of the volunteering opportunities was an area with data gaps for Pears projects, with 5 out of the 6 projects not stating the modality of their volunteering opportunities.

One Pears project offers digital and flexible opportunities.

Number of volunteers

The number of young volunteers involved in the Pears projects ranges from 140 to 2570 volunteers. The average number of volunteers in an NHSCT project is 1110.

Number of volunteers – by organisation frequency

Geographical regions

One of the projects is based in London and another project is based in the South East.

One of the projects is nation-wide and 2 other projects are based in multiple locations across England.

| Regions | Count |

|---|---|

| National | 3 |

| North West | 0 |

| North East | 0 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 0 |

| West Midlands | 0 |

| East Midlands | 0 |

| East of England | 0 |

| South West | 0 |

| South East | 1 |

| London | 1 |

| Not stated | 1 |

| Total | 0 |

Annex 2 – Evaluation activity completed under Phase 1

Evaluation activity completed under Phase 1

Evaluation activity, summarised below, commenced in January 2022, and forms part of the overall evaluation. The proposed options to be delivered under phase 2 build on what has already been delivered to May 2022.

1. Monitoring information strategy