The stability of the early years workforce in England

Published 5 August 2020

Applies to England

The stability of the early years workforce in England

An examination of national, regional and organisational barriers

Research report, August 2020

1. Foreword

The first five years of a child’s life are critical to their future development. This is not disputed. During this period, stark development gaps often appear between children from poorer and more affluent backgrounds. Key to closing these gaps – which influence life chances – are nursery workers and child minders. But what do we know about the early years workforce and do we value them enough? Are the 280,000 people who look after and educate our children becoming our forgotten key workers?

The system for educating, developing and supporting the under-fives is fragmented and does not lend itself to an easily implementable strategy, as the Children’s Commissioner has recently highlighted. New initiatives are hard to make work. Funding is tight and providers are stretched, while geography makes life difficult. The mix of provision in the private, voluntary and public sectors compounds this further.

The Social Mobility Commission has focused its research on why the early years workforce is so unstable – why recruitment is so difficult and why so many leave shortly after they join. The report also includes several profiles of those working in early years, giving a vital insight into the difficulties some face.

The research findings are startling. The average wage in the early years workforce is £7.42 an hour – well below the minimum wage and the average pay of £11.37 an hour across the female workforce. A substantial proportion are paid under £5.00 an hour. Work demands, including considerable amounts of paperwork, are high, often leading to burnout and an early exit. There are also significant regional differences in the data, suggesting some levelling up is needed across the country.

The research does show that many of the workers are passionate about the job they do and report higher levels of happiness than the total working population. But more than one in six leave within a year, according to one recent study.

Women and young people dominate the workforce, which can also contribute to higher turnover. Over 95% of the workforce are women and 40% are younger than 30, with many taking time off for career breaks. Crucially, there is not enough training or professional development. So relations between managers and staff break down following unrealistic expectations.

The inevitable conclusion is that each of these findings are both reasons for and consequences of a society that does not value the early years workforce as it should. The intellectual challenge is significant, yet wages are low and not enough support exists to support staff to meet that challenge.

There are excellent workers employed in the sector, but to ensure a consistent high-quality early years workforce, it will take a monumental effort to change the perception of an entire sector. And it also does not happen overnight. But as we try to build back better and learn the lessons of the pandemic, there is no better time. We should not see this as too ambitious – it matters too much.

The Commission recommends a first step: a comprehensive strategy that includes a clear training pathway from apprentice to primary school head. We also propose a workforce registry that would enable a sense of belonging and a community for meaningful professional development at each stage. In addition, we urge the government to ensure that resources for early years match the operational costs of funded places.

We are all too aware that strategies have come and gone before. The government’s big majority and four remaining years give it enough time to commit to this. If it commits, if it takes the sector with it, there may be a fighting chance. We can no longer afford to ignore this group of key workers so critical to social mobility.

Sandra Wallace and Steven Cooper

Interim Co-Chairs, Social Mobility Commission

2. Executive summary

By the time children are five, those from disadvantaged families are already significantly behind their wealthier peers in a variety of development measures. Key to reducing this gap is high- quality early years (EY) provision, delivered by a qualified and skilled workforce. However, in recent years, there have been signs that the early years workforce is increasingly unstable, with too few new entrants to replace those who are leaving the sector. In this report, we examine key factors that appear to be associated with instability in the early years workforce and provide recommendations on how to address the most pressing issues.

We conducted a review of the relevant literature; an analysis of quantitative data covering a large representative sample of workers in England; and 40 interviews with early years practitioners, setting managers and local policy-makers. The most common barriers identified in all three strands of research were pay, work demands, certain demographic characteristics, training and the organisational climate of the early years provider.

We found that:

2.1 Pay

Evidence from several studies suggests that pay is associated with practitioners’ propensity to leave their employer and/or the sector altogether. In England, the average wage across the EY workforce is £7.42 per hour – slightly higher than the average wage in the retail sector (£7.09) and much lower than pay across the female workforce (£11.37). The EY practitioners we spoke to struggled to meet their living costs and moved to other employers for even a small increase, or left the EY sector for other low-skilled work where wages were higher.

2.2 Work demands

High work demands contribute to turnover among EY practitioners primarily because they can lead to burnout. The literature highlighted several sources of excessive work demands in the EY sector, including long hours and unpaid work, having to care for too many children at once, and having too much paperwork to complete. In England, EY professionals work longer hours than people in comparable occupations: 11% of full-time EY workers reported working more than 42 hours per week, compared with 3% of retail workers, 6% of female workers and 13% of the total working population. Interview participants described long hours, inadequate working conditions and considerable amounts of paperwork as causes of exhaustion and low morale, feeding a desire to leave EY for less-demanding work.

2.3 Demographic characteristics

Age and gender were frequently discussed in the literature. Younger workers, with less experience, responsibility and commitment to the sector, may be more likely to leave the workforce than older workers, except for those approaching retirement. Meanwhile, some short- term instability can be determined by women taking time off for career breaks such as maternity leave. The English EY workforce is predominantly composed of young, female workers: 40% are younger than 30, and 96% are female.

2.4 Training and continuing professional development

There is some evidence to suggest that EY workers whose employer offers high-quality and relevant training, advice and professional support, and who are compensated for the time they take to train, are more likely to remain with their employer. Yet existing studies suggest that practitioners do not receive the amount of training and continuous professional development (CPD) they consider adequate.

Interview participants told us they felt that the entry-level qualifications held by junior staff entering the sector were often inadequate preparation for the job. For those looking to upskill after entering the workforce, participants told us that there was rarely anything more advanced than a basic course offered by the council, while higher-level qualifications were costly to attain.

2.5 Organisational climate and culture

The literature suggests that certain aspects of organisational climate and culture in EY settings – such as pre-existing staff stability and positive management practices – are associated with staff retention. Interview participants said they were more likely to work long term in an EY setting where management supported staff, involved them in decision-making and fostered mutually supportive relationships between them.

2.6 Context

The DfE’s Early Years Workforce Strategy (2017) aimed to support the development of a well-qualified workforce with the appropriate knowledge, skills and experience to deliver high-quality early education and childcare for young children. Some positive steps have been taken: for example, the revision of Level 2 and Special Educational Needs Co-ordinator (SENCO) qualifications. These developments were underpinned by the publication in June 2018 of an occupational map, outlining to employers and practitioners the career pathways the sector offers.

However, less progress has been made on the more strategic commitments. In 2018, the government abandoned proposals to grow the early years graduate workforce in poorer areas and to change the rules to allow those with Early Years Teacher Status or Early Years Professional Status to lead nursery classes in maintained settings. Similarly, recruitment and retention challenges have not eased. This may reflect a lack of policy focus, which has also materialised in the frequent change of the minister responsible for early years policy.

2.7 Effects of COVID-19 on early years sector

While this research was conducted before the outbreak of COVID-19, the drivers of workforce instability are likely to persist and even worsen as a result of the pandemic.

Many EY workers have been furloughed via the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, receiving up to 80% of their regular income and finding it even harder to get by without other support. We know that before the recent crisis, around 45% of childcare workers claimed state benefits or tax credits – well above the average among the wider female workforce. It is likely that this proportion has increased or will increase throughout the second half of 2020 and beyond.

With furlough regulations changing and the furlough scheme ending in the next few months, there will also be a need to monitor both the size and the composition, in terms of qualification levels, of the EY workforce. A changing workforce will have implications for CPD needs. This study suggests that high-quality CPD is valued by EY professionals, but it is difficult to know what CPD will be available in the future, whether it will match the needs of a changing workforce and whether EY settings will be able to afford it.

For many working in early years, the crisis has further destabilised an already precarious situation. When and how the sector will recover depends on a new understanding of its crucial work for society and a funding system that reflects this.

2.8 Policy recommendations

The government should convene an expert group to devise a career strategy for early years professionals working with children aged zero to eight.

The strategy should include:

- a new training pathway that allows people to start as apprentices and upskill along a clear path all the way through to primary school headship, with opportunities to enter the sector at any point along this development continuum, depending on qualifications and experience

- a reform of careers advice services to make sure clear expectations are communicated about what a job in EY entails, while portraying careers as a real professional choice rather than a fall-back option for low achievers

- a pilot of a workforce registry that would allow EY practitioners to create a community, develop a sense of belonging, craft their professional profile and access CPD opportunities

- a clear plan for attracting those further or later on in their careers to join the workforce as EY educators

The government should address the shortfall between the costs to providers of funded places in early years settings and the actual money allocated for those places:

- in the short term, funding rates should increase to match rising operational costs due to inflation and National Minimum Wage increases

- in the long term, the government should launch a review of funding by education phase, looking into alternative systems to allocate public funding

3. Introduction

3.1 Background

By the age of five there is already a gap in attainment based on socio-economic background, and this gap persists throughout school. Key to reducing this gap is high-quality EY provision delivered by a qualified and skilled workforce.[footnote 1] And yet the EY sector faces significant challenges in demonstrating its value to both early education and wider social mobility aspirations. For instance, it is sometimes seen as ‘just childcare’ and there is an under- appreciation of the crucial roles it plays in children’s development. This in turn leads to issues of recruitment and retention of a qualified and skilled workforce.[footnote 2]

A crude but useful measure of workforce instability is the turnover rate – the percentage of employees who leave a company within a certain period of time. Recent studies estimate the turnover rates for the EY workforce to be between 11% and 15%, depending on the source (see Annex 1 for an overview of different estimates).[footnote 3]

The stability of the EY workforce matters because, without it, quality provision is harder to achieve. Having stable EY education is even more important in disadvantaged communities, as research suggests that children from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to be in resource-rich home environments.[footnote 4] A variety of factors are likely to affect stability, such as there being different types of providers in the sector – maintained nurseries, private, voluntary and independent (PVI) settings, and childminders. In addition, some providers are single-site settings while others are larger nursery chains. We might also expect EY providers in urban and rural settings to face different types of barriers to recruitment and retention. In some geographies, the workforce is local and likely to remain local. There are limited incentives for workers to move into more isolated areas or to travel significant distances to work. Meanwhile, a limited and localised labour market also means fewer job alternatives for those wanting to leave the EY sector.

The Social Mobility Commission’s State of the Nation 2018–19 report highlighted some significant regional disparities in social mobility and across the proxy indicators at each stage of the life course, including the EY indicators.[footnote 5] Other studies have also found some regional disparities in children’s access to qualified EY staff.[footnote 6] This is an opportunity to shed light on some of these disparities for the EY workforce.

3.2 Research questions

The study addresses the following research questions:

- how stable is the EY workforce in England?

- what are the main barriers to stability?

- how do these barriers vary by region?

- how do these barriers vary by provider type?

3.3 Definitions

Workforce stability can be analysed in three different ways:

- as retention within the sector – to what extent are people leaving the EY workforce altogether?

- as movement between settings – to what extent are workers moving between different providers and why?

- as movement within the setting itself – to what extent are EY workers moving to different roles within the same institution?

All three levels of stability have an impact on the quality of provision and children’s outcomes.

3.4 Who are the EY workers?

EY workers provide education and care to children aged zero to five, performing a variety of tasks from setting up age-appropriate activities for children to supervising other staff.

EY workers can be self-employed, such as childminders, or work in a formal nursery.

Nurseries may be part of a school or children’s centre or be independent of either. The majority are run by organisations in the private, voluntary and independent sectors.

Childminders must have completed some training on how to implement the EY curriculum. Staff at nurseries may in principle hold no relevant qualification, but in practice most staff hold at least a full and relevant Level 2 qualification.

3.5 Overview of the report

The next chapter provides an overview of the key findings of the report and the relative strength of each of the barriers to workforce stability. The Evidence review section describes the findings from the literature review. This in turn formed the basis for the What we found section, which describes in detail the findings from the quantitative and qualitative strands of research. The Conclusions section rounds up the implications of our research, offering evidence-based policy recommendations. A full description of the methodology employed in this study can be found in Annex 2.

4. Key findings and strength of the evidence

In this chapter, we summarise our findings and assess the different barriers to the stability of the EY workforce identified in the three strands of our analysis: the literature review, the quantitative analysis of Annual Population Survey (APS) data and the qualitative interviews.[footnote 7]

4.1 Stability of the English workforce

As mentioned in the introduction, there are several ways to look at workforce stability. The most common approach to assessing this is the turnover rate – the proportion of staff at a setting who are replaced within a given time period. Recent estimates of turnover rates for the EY workforce in England, based on broadly representative samples of EY settings, vary from 11% to 15% (Annex 1).[footnote 8] By comparison, a recent estimate for the turnover rate of teachers in primary schools is 19%, but the methods used to calculate these figures are different, so caution should be taken when making comparisons.[footnote 9]

Moving beyond turnover rates, the APS data used for the quantitative analysis looks at how long individuals have been with their current employer. The data shows that EY workers stay with the same employer for shorter periods of time than other occupational groups. There is also greater instability in urban areas than in rural areas and in the private sector than in the public sector, while there are no significant differences between deprived and affluent areas.

4.2 Income

There is strong evidence that the instability of the EY workforce is related to the low income of its members. The evidence is clear that a high proportion of the EY workforce is on low pay, both in absolute terms (high proportion of practitioners earning the minimum wage) and in relative terms (high proportion of practitioners earning less than workers in other sectors that require comparable qualifications). This problem is particularly salient for EY practitioners with children or other dependents.

The situation is compounded by:

- the unintended effects of government policies, such as the minimum wage and the 15 and 30 hours of funded childcare

- the relatively high living and transport costs in some areas

Differences by region

There is weak evidence that the barrier of low income varies by population density or level of deprivation. Our analysis of APS data shows that EY practitioners in deprived areas are paid marginally less, but this could also reflect lower costs of living. Interviewees were also divided: the way government funding is distributed is perceived to favour deprived areas, but settings in affluent areas can charge parents extra for additional services.

Differences by provider

There is strong evidence that the barrier of low income varies by provider type. Our analysis of APS data shows that EY practitioners are better paid in the public sector than in the private sector. This is in line with the perceptions of the practitioners we interviewed. This increases the risk of mobility within the sector, because workers with higher education levels have strong incentives to leave the private sector and seek employment in the public sector.

4.3 Demographic imbalance

There is strong evidence that the instability of the EY workforce is related to its demographic composition, and in particular to its over-reliance on female practitioners. The APS data shows that 96% of practitioners are women and 40% are under 30. Both the data and the interviews show that this makes the EY sector particularly vulnerable to gender-specific causes of instability such as parental leave and career breaks among young, low-income parents.

Differences by region

There are no differences across geographies in terms of gender participation in the EY sector.

Differences by provider

There is weak evidence that the barrier to stability determined by demographic characteristics varies by provider type, and we found similar distributions across the public and private sectors.

4.4 Workload and responsibilities

There is strong evidence that the instability of the EY workforce is related to the high workload and the demanding nature of the job (compared with retail, for example). Our analysis of the APS shows that although a high proportion of EY practitioners work part-time, they work significantly longer hours than retail practitioners. Interview participants confirmed that they work long hours and spoke about the amount of paperwork to be done during or outside of working hours, and the perceived demands of Ofsted inspections.

Differences by region

There is no evidence that workload and responsibilities vary by levels of deprivation. The APS shows that a smaller proportion of EY practitioners work long hours in deprived areas than in affluent areas. Some interview participants had a similar perception. They suggested that parents’ longer working hours in affluent areas often result in overwork for them. Other practitioners felt that the opposite was true. They indicated that settings in deprived areas often have to deal with higher numbers of children with additional or complex needs, such as special educational needs (SEND), poor mental health and poverty. This creates more work, which contributes to the instability of their workforce.

There is also no evidence that the barrier of workload varies by population density.

Differences by provider

There is strong evidence that EY practitioners in public settings are less likely to work long hours than colleagues in the private sector. We found a significant difference between the two groups in the APS. This was also the perception among interviewees. Practitioners working in PVIs, for example, felt that working conditions were better in school nurseries due to shorter opening hours and term-time-only schedules.

Our qualitative research highlighted an interesting variation that did not emerge from the literature review or the APS, namely the variation between larger and smaller settings. Overall, participants felt that larger settings provide more support and better working conditions. This was felt most acutely by childminders, who are self-employed and tend to work on their own.

These results are broadly in line with the literature reviewed as part of this project.

4.5 Training and continuous professional development

There is strong evidence that the instability of the EY workforce is related to low entry and exit barriers and to limited opportunities for career progression. The APS shows that EY practitioners are less qualified than the working population as a whole. The managers, policy- makers and more experienced practitioners we interviewed reported a trend of junior staff coming into the sector with entry-level qualifications who are underprepared for the job. This observation is in line with the literature.

Despite these low qualifications and a perceived high level of responsibilities, according to APS data only one EY practitioner in six had received job-related training in the last month. The interviewees did not consider current access to CPD opportunities to be adequate, with the key reasons identified as a lack of training budgets and limited time, especially among childminders. The literature also indicates that some managers are reluctant to train their staff because they fear that they will become more competitive and leave their setting for a better job.

Differences by region

There is no evidence that opportunities for progression vary by region. Although the APS shows that EY practitioners in deprived areas are less qualified than those in affluent areas, there is no evidence that deprived areas offer fewer training opportunities than affluent areas. There is also no evidence that practitioners working in urban areas have greater training opportunities.

Although interviewees suggested that training opportunities were less accessible in rural areas, the APS shows that EY practitioners in rural areas get the same amount of CPD as colleagues in urban areas.

Differences by provider

There is moderate evidence that practitioners in school nurseries are (a) more qualified than their colleagues in private settings and (b) more likely to have access to training. The perception among some practitioners is that this has more to do with the size of the setting than with the type of provider. For example, childminders reported not feeling supported to engage in training provided by local authorities.

It is also unclear whether practitioners have more opportunities for progression in school nurseries or PVIs. Practitioners working in schools felt that there was little room for progression at their settings, while practitioners working in PVIs felt they had fewer opportunities to progress than their colleagues in schools. They explained that their only chance to progress was by moving setting. Other participants highlighted that there are more opportunities to progress in larger settings, regardless of the type of provider.

4.6 Knowledge and societal views of the sector

There is moderate evidence that the instability of the EY workforce is related to the perception that it is an unattractive, low-skilled, low-pay profession. This problem was explicitly mentioned in interviews as well. Practitioners pointed to the mismatch between the expectations of newly qualified practitioners and the actual requirements of the job. They saw this mismatch as a major source of frustration for all parties. Some practitioners felt that the job was not what they signed up for, and some managers felt that new staff were sometimes unprepared and unintentionally created more work for their colleagues. Practitioners perceived this as increasing the risk of resignation and dismissal.

Differences by region

There is no evidence that the reputation of the EY sector varies by region.

Differences by provider

There is weak evidence that the status of the profession varies by provider type. The issue was raised mainly by childminders, who were frustrated at being perceived as ‘babysitters’ by parents, friends and other EY practitioners. Participants from formal settings, whether PVIs or maintained settings, did not explicitly mention the reputation of the sector as a source of instability but explained that new entrants to the sector are often unaware of the demands of the job. This unawareness was a reason why some practitioners left or considered leaving the profession.

4.7 Organisational climate and culture

Interview participants mentioned a positive team culture and approachable, inclusive management as strong motivators for staying in a workplace long term. Conversely – and unsurprisingly – they indicated that lack of trust, bullying and excessive workloads all contributed to instability. The literature we reviewed lends only weak support to this argument.

Differences by region

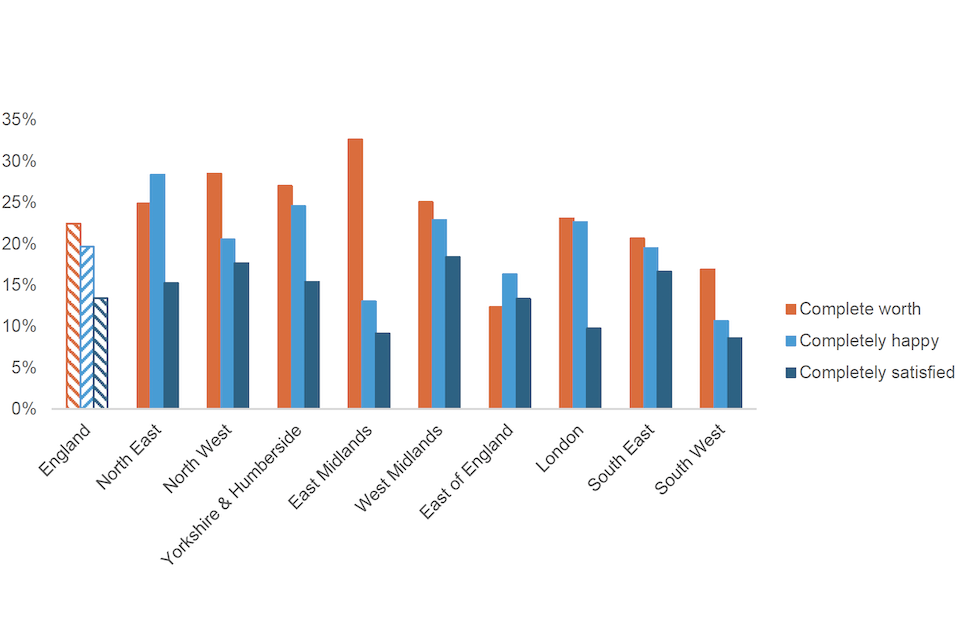

There is weak evidence that practitioners in affluent areas have better working conditions and higher levels of job satisfaction than their counterparts in deprived areas. The statistics contradict the perceptions. The APS shows that EY practitioners in deprived areas are happier and less anxious and have higher levels of self-worth than practitioners in affluent areas. Some practitioners felt that parents in more affluent areas are often more involved with the setting, which they believed had two advantages: greater job satisfaction and reduced workload.

There is no convincing evidence that practitioners in rural areas have better working conditions or higher levels of job satisfaction than their counterparts in urban areas. We did not find significant differences in the APS between rural and urban areas in terms of job satisfaction.

Here again, perceptions were rather different. Practitioners expressed the view that, overall, rural areas provide better working environments and inferred that this could encourage retention. They felt that rural areas have a greater sense of community and provide better play areas. Although they recognised that staffing can be more challenging in rural areas, they said that the workforce is more stable due to a lesser reliance on agency practitioners.

Differences by provider

There is no convincing evidence that the culture of a setting depends on whether it is a school nursery or a PVI. The APS shows that EY practitioners in the public sector have slightly lower levels of happiness, satisfaction and self-worth, and higher levels of anxiety, than those working in private settings. However, this result should be treated with caution, as it contradicts other findings about working conditions and workload.

EY practitioners at school nurseries did not mention organisational culture as a barrier to stability. Within PVIs, one view was that the climate and culture of the setting has more to do with the size of the setting or the group than with the type of ownership (that is, public or private). However, there was no consensus about the direction of the association: some practitioners thought that larger settings have clearer and fairer procedures, but others thought this greater focus on procedures makes them less flexible and supportive. Some participants indicated that community-run, not-for-profit settings are facing unique challenges in terms of management.

Unsurprisingly given their self-employed status, childminders did not see organisational culture as a barrier to stability.

4.8 Case study: Michelle Wisbey, Thaxted

University lecturer in early years education, aged 50. Has worked in EY for 24 years. Owner/manager of four pre-schools, covering three months to five years, funded by fees and grants.

“In my experience over the past 25 years, the people who become Early Years workers are either mothers returning to work, or young girls who want to look after children, and aspire to have their own.

We are a rural setting, outside of London, where the average income for a manager is £11-12 an hour. As a pre-school manager, you have a large portfolio of responsibility: Ofsted inspections; compliance with Early Years Foundation Stage delivery; safeguarding; managing the team; and overseeing health and safety, to name but a few. It’s a sadness knowing you would earn more money working at ALDI. Young girls often leave the sector due to its low pay, high stress levels and long hours.

Small unique nursery owners are getting to the point that they cannot afford to invest for short- term gain. For practitioners, increased qualification does not necessarily lead to a higher wage. A 19-year-old with GCSEs and a Level 2 NVQ in Early Years has no reason to do more training to a Level 3, because she will earn pretty much the same.

I’ve loved every minute of my work, but I’m lucky in that my income supplements the family income: we are not dependent on it. My generation were funded through our training in the good times, which made a huge difference to the demographics of the people entering the profession. My fear is that as many of us leave the sector or retire, knowledge is slowly filtering out, and the younger staff we leave behind tend to have a lower level of training.

I don’t know the answer, but as long as we have the present mixture of corporate privatisation, rural unique private nurseries and maintained nurseries – all funded and financed differently – we are unlikely to see fair working conditions in the sector.

Qualifications and skills need to be standardised, with qualifications delivered only by FE and HE colleges, rather than small, unregulated training providers. Too many agencies deliver low-quality training and when the government pushed for standardisation and professionalisation, the big corporates pushed back because they didn’t want to pay higher wages.

We need to learn more from other countries that do early years well and respect it as an education and developmental platform for the youngest, rather than just a place where parents leave children so they can go to work.

5. Evidence review

This section presents the findings of a rapid review of the evidence on the factors that influence the stability of the EY workforce.[footnote 10]

Where possible, we also indicate whether a factor of instability is more likely to result in (1) an exit from a sector, (2) a movement between settings or (3) movement within the setting. This reflects the definition of instability presented in the introduction. However, this proved more difficult than expected, as most studies tend to conflate these different outcomes into a single measure of turnover.

5.1 The key barriers to the stability of the EY workforce

The five most important factors associated with instability were identified according to the number of citations in the literature review. They are:

- pay

- work demands

- demographic characteristics

- training and continuous professional development (CPD)

- organisational climate and culture

Pay

Low pay appears to be one of the most important factors in practitioners’ decisions to leave their setting or the sector, while increasing wages is one of the most useful ways to increase retention.[footnote 11]

Several studies find that EY workers with a higher salary are less likely to leave or intend to leave the setting they work at or the EY sector.[footnote 12] One study reviewed suggests that the wages of EY workers are not significantly associated with retention over a 12-month period, but the timing of the study coincided with a major economic downturn, which might have limited job opportunities and so labour mobility.[footnote 13] Studies also suggest that pay is one of the most common reasons for EY workers to consider leaving their setting or the sector altogether.[footnote 14] For instance, one study finds that inadequate pay would cause 52% of EY practitioners in England to leave the EY sector within the next 12 months.[footnote 15]

Some studies suggest that EY workers take low pay as a given in the sector, with their desire to work with children outweighing concerns about low pay.[footnote 16] However, far from communicating an acceptance of low pay, this appears to be testament to the intrinsic motivations of many EY workers to work in the sector. Some practitioners reported having no choice but to take second jobs, while others described themselves as living on the edge of financial survival.[footnote 17] Additional strain is put on the ability and desire of EY practitioners to remain in the sector by the combination of low pay and high work demands.[footnote 18] This is compounded by the lack of recognition of EY workers’ qualification levels relative to other sectors, with workers who hold a bachelor’s degree often earning a lower wage in the EY sector than they might in other sectors.[footnote 19] A further risk is that EY practitioners feel they receive wages that are unfair when compared with those of other workers in the education system.[footnote 20]

EY workers reported that workforce stability would increase if their pay was increased, and especially if it reflected their level of education and experience and the responsibilities of their job.[footnote 21]

Work demands

High work demands on EY workers can lead to burnout, especially when it goes without sufficient pay or other compensation. Five main issues contribute to excessive work demands in the EY sector: long working hours, paperwork, child-to-staff ratios, high levels of responsibility and unfavourable tasks.

Long hours:

Workers in the EY sector reported that having to work long hours, especially when they are not paid for all of their hours, is a reason why they move between settings or leave the sector altogether.[footnote 22] Some 92% of practitioners in England reported having worked some overtime in the past year,[footnote 23] while 62% of EY workers in group-based settings reported that they do not have a good work–life balance.[footnote 24] There is some evidence that the number of hours worked by practitioners varies by setting type, with EY workers at private settings working on average 45 to 50 hours per week, compared with workers at voluntary settings, who work 35 to 40 hours per week.[footnote 25]

One study suggests a mismatch between the perception of working hours among EY employers and workers, with employers thinking that shorter hours could be a barrier to recruitment because of the associated lower take-home pay.[footnote 26] Workers, on the other hand, value shorter working hours because this gives them more time, for example, to spend with their children, and because doing more hours could be associated with more unpaid work. Indeed, the literature supports the conclusion that EY practitioners do not enjoy working long hours and value flexibility over their work schedule.[footnote 27]

Paperwork:

In addition to working long hours, the literature suggests that EY practitioners can be required to perform unpaid work outside of working hours.[footnote 28] This is because when children are present at the setting, practitioners are mostly required to focus their attention on the children and are unable to do lesson planning and paperwork. Having to complete paperwork could mean getting to spend less time with children, which can lead to reduced job satisfaction.[footnote 29] Some EY workers take their paperwork home with them, which can negatively impact their health and wellbeing.[footnote 30]

Given these findings, it is unsurprising that one study found that EY practitioners who were happy in their roles were paid for non-contact time to do paperwork and administrative tasks.[footnote 31]

Child-to-staff ratios:

One reason EY practitioners and managers gave for taking paperwork home is restrictive and unmanageable child-to-staff ratios.[footnote 32] The child-to-staff ratio refers to the number of children one staff member is permitted to care for at a time. In England the number differs depending on the children’s ages, with child-to-staff ratios being lower the younger the children’s ages (maximum child-to-staff ratios are set out in regulations in England).

EY workers reported that high child-to-staff ratios reduce their ability to speak to their colleagues, reflect on their practice or improve provision for children.[footnote 33] For instance, one practitioner reported regularly looking after multiple infants by herself and feeling worn out as a result.[footnote 34]

High responsibility and unfavourable tasks:

The evidence suggests that workers in the EY sector often face a high level of responsibility and are required to perform unfavourable tasks. Practitioners also view the high levels of responsibility assigned to them as being out of line with the relatively low pay.[footnote 35] This issue can be particularly pertinent for setting managers.[footnote 36]

Meanwhile, EY workers can become frustrated when given the same tasks daily, especially when these are administrative or simple.[footnote 37] For instance, workers at private day nurseries in England reported experiencing low job satisfaction due to expectations on them to perform heavy cleaning, such as washing windows and mopping floors.[footnote 38] These findings suggest that EY practitioners enjoy being challenged but do not appreciate the high burden of responsibility placed on them, particularly when greater responsibility does not come with greater pay.

5.2 Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics such as the age and gender of the workforce are commonly mentioned in the literature about the stability of the EY workforce. The impact of demographic characteristics often appears to be contingent on other factors such as skills levels and the state of the wider economy, as detailed below.

While age does appear in several studies to be associated with workers’ propensity to leave a setting, with older workers less likely to leave than younger ones, this appears to be due largely to their position within the setting (seniority) or their education levels.[footnote 39] There is evidence that a significant proportion of the workforce is considering retirement, which could strain the stability of the workforce if fewer workers are entering the workforce than leaving.[footnote 40] Some evidence suggests that workers at private EY settings in England are on average younger than those working in the voluntary sector, with one study identifying a 25-year age gap.[footnote 41] This could be because private sector settings often require longer working hours of staff, meaning that those workers who have not yet started families have more time and are in a better position to work there.

A key feature of the EY workforce across the world is that it is predominantly female. There is some evidence that this can act as a barrier to the stability of the workforce, both directly and indirectly. Some 9% of EY settings in England reported having lost staff in the past 12 months due to their decision to take a career break, including maternity leave.[footnote 42] Additionally, the positioning of working in the EY sector as ‘women’s work’ can contribute to its low status, leading to a lower supply of workers and, perhaps, an acceptance of reduced benefits.

5.3 Training and continuous professional development

There is good evidence that EY workers value training and CPD opportunities to learn from other EY practitioners and to feel part of the EY sector, and that these are important factors in their decision to remain at an EY setting.[footnote 43]

Currently, the EY sector has a reputation for offering insufficient CPD and training opportunities,[footnote 44] which some settings reported has dissuaded individuals from joining the sector.[footnote 45] Indeed, practitioners working at EY settings which provide them with higher levels of advice and professional support were found to be less likely to leave their setting after two years compared with practitioners at settings which offer less support.[footnote 46] For those who have joined the sector, a lack of training opportunities can make it more difficult for practitioners to become confident in their skills or to ease the transition into a managerial role, leaving new managers overwhelmed.[footnote 47] EY workers in the voluntary sector have greater access to training and CPD, according to one study which found that they were also provided with more time off during their workday to attend CPD.[footnote 48] In contrast, practitioners at private settings often have to pay for their own training and to attend sessions outside of their paid working hours.

The most common reason for poor provision of training and CPD cited by EY employers is the lack of funding available for training.[footnote 49] Employers in the private and voluntary sectors often lack the funds to pay for staff cover while their staff are on training.[footnote 50] This issue is not showing signs of relenting, with a 2019 survey finding that only 8% of EY settings in England planned to spend more money on training the following year, while 55% planned to spend less.[footnote 51] There is some evidence that employers are concerned that offering training and CPD to staff could lead those staff to become more competitive in the sector and to move to a new employer.[footnote 52] In fact, some practitioners did report that they are motivated to take part in training because they want to access a more senior position in a different setting.

The type of training offered is important to EY workers, as is the recognition they get – in pay or career progression – for having completed training.[footnote 53] This can mean that mandatory training which is unaccompanied by a pay rise can actually be a barrier to staff retention, as some staff reported that mandatory courses do not teach them anything new, while some may refuse to take part if they are not compensated for doing so. In one study, practitioners reported that they disliked having to continually obtain qualifications because they believed practical experience with children outweighed the qualifications gained through written assignments and observations.[footnote 54]

5.4 Organisational climate and culture

Organisational climate and culture refer to the perceptions that EY practitioners and managers have of the organisation (or setting) and their shared beliefs and behavioural expectations.

There is mixed evidence about the impacts that the organisational climate can have on staff retention in the EY workforce.[footnote 55] However, there is evidence that certain aspects of the climate and culture – such as a culture of stability and positive management practices – are associated with staff retention.

There is evidence that the management style of leaders in EY settings has an impact on the stability of the workforce. Practices which appear to positively affect staff retention include making staff feel valued and listened to by their manager, and giving them a say over their working hours, the curriculum of the setting and the organisational ethos.[footnote 56] EY workers also appear to value managers who recognise the commitment and achievements of their staff and who do not believe they are above doing ‘dirty work’ like changing nappies.[footnote 57] EY workers’ job satisfaction and retention are also positively impacted by their belief that their work is worthwhile, having friendships with colleagues, sharing progress with parents, and receiving recognition and support from management.[footnote 58]

In contrast, job satisfaction appears to be negatively impacted by practitioners having insufficient time to perform the job well while perceiving management to behave more favourably towards some staff members than others. It is worth noting that evidence is inconclusive on the extent to which job satisfaction is associated with workers’ propensity to remain in a setting.[footnote 59]

There is some evidence that there are different management styles at EY settings in the private sector and voluntary sector. One study found that practitioners at private settings regarded managers as disengaged but controlling and reported that they did not feel comfortable going to management with an issue.[footnote 60] At voluntary settings, staff felt that the managers struck a balance between being senior members of staff and playing an important part in the day-to-day work with the children.

It appears that staff turnover in an EY setting can lead to more staff turnover in the future. Managers of EY settings in the USA reported that a practitioner leaving the setting leads to a reshuffle of roles in the setting and lower morale among the remaining practitioners.[footnote 61] The continuity of management staff also seems important, with staff turnover of practitioners being higher in settings where the manager has been replaced more recently.[footnote 62]

5.5 Summary of key points

The literature highlighted several factors that have a negative impact on the stability of the EY workforce. While a passion for working with children and feeling valued in the workplace help to keep many professionals in the sector, several other elements emerged as important drivers of instability. These were low pay, increasing workload and responsibilities, limited opportunities for CPD and career progression, a lack of support from the setting management or local authorities, high volume of paperwork, and less time spent with children.

We found little or no information about workers’ employment history and about stability in terms of movement within the setting. Importantly, the literature gave little attention to some key themes, such as differences across geographies and the influence of wider labour market dynamics, which makes this study’s place-based approach even more important to fill in this evidence gap.

5.6 Case study: Fiona Doyle, London

Former school teacher, aged 36, who switched careers to early years five years ago and now runs her own childminding business and three after-school clubs.

“I was a secondary school teacher for nearly 10 years. I reached management levels and became head of department. But then I had my daughter and I retrained as a childminder, five years ago now.

For me, it was difficult reputationally to go from being a respected head of department to being a childminder. It was difficult emotionally, because it’s not a well-respected profession. People tend to view it as a low-skill service industry.

When I retrained I thought as a qualified teacher it wouldn’t be that difficult, but there was a lot more to learn, including a Level 3 Childminding course, my DBS security check, and my first aid and safeguarding courses.

Childminding involves a lot of study and continuing professional development (CPD). You have to have full knowledge of the EYFS (Early Years Foundation Stage), you’re inspected every couple of years by Ofsted, and you have to retrain constantly. It’s an intense, high- pressure job.

You need excellent communication skills and patience. Soft skills and tact are important when supporting parents and offering advice and signposting where necessary – for example if you’ve spotted signs of special needs.

We work to the EYFS requirements and constantly monitor their physical development, their emotional literacy, their language, their maths, their reading. Can they hold a fork? Can they thread beads? Can they write letters? We teach them all of that. We also make observations, record them in our reports and then feed back to the parents.

When I was teaching in secondary school, my experience was the girls who didn’t have an idea of what they wanted to do were all put on the BTEC Childcare course.

Bigger nurseries can employ kids of 18 or 19, with just a couple of GCSEs. That gives them a viable job and career, but on the other hand, they’re being told that’s all they can do, so people who get more GCSEs don’t want to do childminding.

We need to focus on the fact that EY is part of the education system. There can be such a discrepancy between a child’s development before they start school and after they enter reception. Actually, the learning starts as soon as you place them in someone else’s care.”

6. What we found

This chapter describes the barriers to stability faced by the EY workforce in England. It includes the results of the quantitative and qualitative strands of the research and looks in detail at the major barriers to workforce stability identified by the literature review.

The quantitative strand involved analysis of data from a special request of the APS for the years 2015 to 2017. The data identified approximately 280,900 EY professionals in England: 58% were nursery nurses and assistants, 33% were childminders and 9% were playworkers. These three occupations are presented together as the EY workforce. This group is representative of people working in PVI settings and of childminders, as well as of those working in maintained and school-based nurseries. It does not include reception year teachers, who are not a focus of this research.

The qualitative strand involved a series of 40 interviews with EY practitioners, setting managers and local policy-makers. Participants were recruited from areas with varying poverty levels and a mix of urban and rural areas representing a range of geographies. Interviews focused on the main barriers to EY workforce stability identified in the literature review, but participants were also encouraged to talk about other barriers (see Annex 2 for more details on the methodology).

Following a brief summary of the stability of the EY workforce in England according to the APS data, the findings from both strands (where applicable) are presented for each of the following barriers to the stability of the EY workforce: pay and funding, work demands, demographic characteristics, training and CPD, organisational climate and culture, and knowledge and societal views of the sector.

6.1 Overview of the stability of the EY workforce in England

The APS data does not allow us to calculate turnover rates at provider level. Instead, we can observe the length of time individuals have been with their current employer. We find that around 37% of EY workers have been with their current employer for less than two years, which is a smaller proportion than among retail sector workers (47%), but higher than among female workers (31%) and all workers (29%). In contrast, a smaller proportion of EY workers stay with their employer for 10 to 20 years: 16% compared with 13% of retail workers, 21% of female workers and 21% of the total workforce.

According to this measure, staff stability varies substantially across regions, with the north in general having a more stable population than the south or London region. Approximately 31% of EY workers in the north of England stay with their current employer for less than two years, compared to 37% in the midlands and 40% in the south of England. Conversely, 19% of EY workers in the north of England stay with the same employer for between 10 and 20 years, 18% in the east and west midlands and 13% across London and the south of England.

We find only small differences between rural and urban areas. Similar proportions of workers stay with the same employer for less than two years in rural and urban areas (36% vs 38%) and the same proportion stay for two to five years (25% vs 25%). However, a higher proportion of workers in rural areas (19%) stay with the same employer for 10 to 20 years compared with workers in urban areas (15%)

Finally, our findings suggest that private sector workers stay with their current employer for fewer years than those in the public sector. A larger proportion of private sector workers (39%) stay with their current employer for less than two years compared with public sector workers (27%). Similar proportions stay in continuous employment for between two and five years (25% private vs 23% public) and between five and ten years (18%), but only 14% of private sector workers stay with the same employer for between 10 and 20 years, compared with 25% of public sector workers.

6.2 Pay and funding

The literature review highlighted low pay as one of the leading factors associated with instability of the EY workforce. Our analysis of the APS shows that the average wage across the EY sector is £7.42 per hour, which is similar to the retail sector (£7.09), but far lower than the average pay across the female workforce (£11.37) and total working population (£12.57).

As shown in Figure 1, 60% of EY workers are paid between £5 and £9 per hour, compared with 72% of retail workers, 35% of the female workforce and 29% of the total working population. At the other end of the spectrum, only 12% of EY workers are paid above £11, compared with 7% of the retail sector, 45% of the female workforce and 53% of the total workforce.

Figure 1: Banded hourly pay for EY workers, retail workers, the female workforce and the total workforce

| Workers | £0 to £5 | £5 to £7 | £7 to £9 | £9 to £11 | £11 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early years workers | 13% | 29% | 31% | 15% | 12% |

| Retail workers | 12% | 34% | 38% | 10% | 7% |

| Female workforce | 5% | 14% | 21% | 15% | 45% |

| Total workforce | 4% | 11% | 18% | 14% | 53% |

Source: ONS (Office for National Statistics), Annual Population Survey, 2018

Interview participants identified low income as a major cause of instability in the EY sector. A low income could be the result of low wages, high living costs or changes to government policies – or all three.

They said that earning National Minimum Wage, or just above, was widespread. Workers on this wage struggled to meet their living costs and moved to other employers for even a small pay increase or left the EY sector for other low-skilled work, such as retail or bar work, where wages were higher.

“Recently we’ve had, ‘I can get more money working in a bar’.” – Director of Children’s Services, deprived/rural

Practitioners who are parents face additional challenges. Participants reported examples of parents who had either left or considered leaving the sector because of a combination of low pay and unintended effects from the benefit system. This problem was acute at two stages of a child’s life. First, parents wishing to return to work in the EY sector from parental leave found that they could not earn enough to cover their own childcare costs, so these practitioners chose to become stay-at-home parents instead.

“We’ve got someone that’s not coming back from maternity leave again because they can’t afford to live. We offer a discount for staff children, but even with that they can’t afford to come back to work basically because they wouldn’t make as much money as they need to cover their own rent and rates and everything else at home.” – PVI setting manager, affluent/rural

Second, practitioners with children approaching the stage when child support benefits would be withdrawn could struggle financially. Without these benefits, they found it difficult to cover basic living costs. With limited ways to increase their wages while remaining in an EY job, they needed to consider seeking better-paid work to survive financially.

Practitioners said government policies designed to support EY, such as 30-hours funding, the quality supplement (a payment of £1,000 a year from local authorities to nurseries that employ a qualified EY teacher) and the National Minimum Wage, kept wages low and caused instability in nurseries.

Three problems with 30-hours funding made it hard for nurseries to raise wages:

- the hourly rate paid by the local authority may be too low to fully cover the nursery’s costs, leading to budget shortfalls

- some nurseries were uncertain when their 30-hours payments would arrive, as local authorities occasionally failed to communicate or did not give enough advance notice of the funding rate for a new financial year

- the local authority may suddenly underpay in one month after overpaying in another

“We had an issue just a couple of weeks ago that … there’s now going to be a massive shortfall in the monthly payment for November because of overpaid in September and October … which just really mucks up things.” – PVI setting manager, affluent/urban

Practitioners also raised problems with the quality supplement. They saw it as unfair because it did not help nurseries pay higher wages to reward other highly qualified staff. Further, there were reports of local authorities abruptly withdrawing the quality supplement, leaving a hole in funds to pay EY teacher salaries.

The age boundary of the National Minimum Wage, which requires workers to be above 25 to earn the full rate, caused problems for practitioners below this age. Practitioners said it was possible for a Level 3 qualified practitioner under 25 to earn less than an unqualified worker over 25 for the same job. Once again, this was described as a motivation to leave the sector.

“Those who are Level 3 qualified, if they don’t happen to be the age of 25, are seeing colleagues that aren’t Level 3 qualified getting better pay than they are.” – Director of Children’s Services, affluent/rural

Differences by region

Practitioners interviewed believed that challenges related to pay could be geographically specific. One view was that practitioners in rural areas could be deterred from working in the EY sector because of high travel costs or poor public transport links. In contrast, high rents were of concern to practitioners in more urban areas. A nursery school teacher in a university town highlighted that younger members of staff had left their setting because of this.

“Unless you’re established, you would have to live outside the city to be able to afford [housing] … people do move to different parts of the country.” – Nursery school teacher, affluent/rural

Settings close to public transport were in demand. A childminder in an affluent commuter town explained that childminders nearest to the train station had a competitive advantage regardless of the quality of their provision.

“A lot of parents, first they’re looking for the childminder that is closest to the station, so they can do that drop-off and jump on the train.” – Childminder, affluent/urban

Interview practitioners in rural communities expressed the view that the relative absence of alternative job opportunities could discourage practitioners from leaving the sector. In comparison, practitioners from settings near or within major urban areas observed a trend of staff leaving the sector for retail jobs. In a former mining community in the north of England, a supermarket giant ‘pulled’ practitioners away from the sector because of better pay and shorter hours. A shopping mall in a large city in the south of England had a similar appeal to those unhappy about the sector.

“There’s a big retail presence in the area … they [practitioners] don’t need any paperwork, they don’t have to do reports, they don’t have to do transition records, they don’t have to meet with parents.” – Director of Children’s Services, deprived/urban

APS data shows that EY workers in rural areas are paid, on average, less than workers in more urban areas, at approximately £7.06 per hour against £7.49 per hour. We also find a larger proportion of rural-area workers being paid between £5 and £9 per hour, at 67% of the workforce versus 58% in urban areas. Among higher earners, only 9% of workers in rural areas earn more than £11 per hour compared with 13% of workers in urban areas. The differences are not surprising, as pay conditions generally reflect the cost of living in a particular area and rates of pay are usually greater in urban areas.

However, at a regional level, pay rates do not differ widely. Workers from all regions in England (excluding London) are paid very similar wages, ranging from £7.09 in the west midlands to £7.30 in the east of England. The average hourly wage in London is higher than in all other regions, at £8.67, which may be partly explained by the London Living Wage of £10.75. Most EY workers across all regions (excluding London) earn between £5 and £9, ranging from 75% of the EY workforce in the north-east and south-west to 52% in the east of England (Figure 2). Approximately 52% of workers in London are paid more than £9 per hour. For lower-income earners, 20% of workers in the east midlands and 19% of workers in the east of England are paid between £0 and £5 – both areas have the largest proportion of low-income earners of all regions.

Variation in regional wages may be minimal because EY workers’ pay is already close to the National Minimum Wage. This is indicative of the inability of settings to increase pay much above this minimum due to financial difficulties.

Figure 2: Banded hourly pay for EY workers by region

| Region | £0 to £5 | £5 to £7 | £7 to £9 | £9 to £11 | £11 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North East | 8% | 31% | 43% | 11% | 7% |

| North West | 8% | 45% | 27% | 12% | 8% |

| Yorkshire and Humberside | 11% | 37% | 31% | 11% | 10% |

| East Midlands | 20% | 27% | 31% | 12% | 11% |

| West Midlands | 14% | 38% | 29% | 12% | 6% |

| East of England | 19% | 27% | 25% | 19% | 11% |

| London | 11% | 12% | 25% | 23% | 29% |

| South East | 16% | 26% | 34% | 14% | 10% |

| South West | 11% | 32% | 42% | 9% | 6% |

Source: ONS, Annual Population Survey, 2018

We find that the average pay of EY workers differs by an area’s deprivation level, with workers in the most affluent areas being paid £7.28 per hour, on average, compared with £7.30 in the most deprived areas. However, differences begin to emerge among higher earners. The data shows that approximately 26% of EY workers in the most affluent areas are paid above £9 compared with 20% of workers in the most deprived areas.

Low funding rates for 30-hour childcare are a barrier to a stable workforce in all areas, but participants’ focus in affluent and deprived areas varies. Those in affluent areas explained that funding rates were insufficient to cover high running costs. This risked settings’ long-term viability, although settings in affluent areas could often rely on parental top-up fees to supplement the funding rates and keep them afloat. In contrast, a key concern for participants in more rural areas was the combination of low funding rates and a limited supply of children.

Differences by provider type

Clear differences in pay levels emerge across provider types, favouring public sector employees.[footnote 63] On average, public sector workers earn £8.43 per hour while private sector workers earn £7.10 per hour. Around 47% of EY workers in the public sector earn above £9 compared with 20% in the private sector (Figure 3). At the lower end of the pay scale, 26% of public sector workers are paid below £7 per hour, compared with 47% of private sector workers.

Figure 3: Banded hourly pay for EY workers by provider type

| Provider type | £0 to £5 | £5 to £7 | £7 to £9 | £9 to £11 | £11 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private sector | 14% | 33% | 33% | 11% | 9% |

| Public sector | 11% | 16% | 27% | 25% | 22% |

Source: ONS, Annual Population Survey, 2018

Our study participants perceived PVIs to be less stable than maintained settings, as maintained settings offer higher pay and better benefits at all qualification levels. This often leads to career-oriented practitioners moving from PVIs to maintained settings once they have gained their Level 3 qualification.

Even though participants perceived the hourly rate to be higher in maintained settings, they explained that it is possible to earn more at PVIs that are open throughout the year and for long hours. They regarded this as a potential reason for remaining at a PVI setting. In contrast, maintained settings restrict how much practitioners can work and earn, as they are only open during term time.

Participants also reported that PVIs with high turnover bring in EY practitioners from staffing agencies. These practitioners earn more money as agency staff, so they do not tend to accept permanent roles. However, this further destabilises these settings.

Both provider types faced funding shortfalls following the introduction of the 15 and 30 hours of funded childcare, but they responded differently. At PVIs, managers paid staff the minimum wage, as this was all they could afford. In contrast, maintained settings responded to the funding shortfalls by decreasing the number of staff they employed, which put high demands on the remaining staff.

There have been a lot of cuts. We currently have an apprentice, but she’s been told that they [the setting] can’t afford to pay her after Christmas, so then we will be one member of staff down.” – Maintained-setting worker, affluent/urban.

Childminders:

Childminders reported facing three specific challenges which related to their self-employed status. First, they do not receive sick or holiday pay. When childminders feel too unwell to work or go on holiday, they need to close their provision and go without income. As a result, they risk losing children and income if parents find alternative providers.

The second challenge childminders faced was an unstable income. Because parents only pay for the time their child is cared for, childminders’ incomes vary depending on the number of children in their care. Those childminders who care for one child or have children that require only part-time care reported struggling financially.

”It works quite well if I’ve got my son and three other children, but if I’ve just got my son and one other child, I charge £4.20 an hour, so I’m not making minimum wage.” – Childminder, affluent/urban

Since the introduction of funded hours, childminders described facing a third challenge: increased competition with maintained settings. To secure funded children, childminders reported that maintained settings offer free care to children who have not reached the age of three but will turn three before the end of their first term at the setting. Maintained settings do this by telling parents that sending their child to nursery early will guarantee their child’s place in reception. Childminders are unable to do this because they cannot afford to give a spot away for free.

“Since the 30 free hours started, I’ve had 3 full-time children who have gone on to just nursery care. That’s a huge amount of competition here and if you’re constantly having to compete, that’s quite disheartening to give up somebody you’ve worked hard with to a competitor.” – Childminder, affluent/urban

6.3 Case study: Kate C, South-east

Early years manager of term-time pre-school, aged 44; 15 years in sector; role is sole household income; single mother of two.

“I’ve been in the sector for 15 years. In that time, I’ve had to rely fairly heavily on Childcare Tax Credits and now Universal Credit (UC). In eight years as manager, I’ve never had more money coming in than I did eight years ago. Whatever I’ve had as a pay rise has reduced my UC. I have to rely on it to pay bills, just to continue living in my house with my children.

There are eight of us working here. I’m full-time; everyone else is part-time. We’re all trained to Level 3 or degree. I should really be paying my early years teacher way more that she gets. She’s well above minimum wage, but when you compare it to other degree-level jobs, she’d probably be getting about double what we’re able to pay her.

Most of the people in the sector are mums or young people starting out – young people who have no idea that they’re not going to get the remuneration that they deserve. That’s not a good place to attract fresh blood.

I’m waiting for my son to finish school and then I’ll have to relocate and find a different job. It’s not a nice feeling when you put your heart and soul into a job and you’re going into more debt every month. At 44, I sometimes have to rely on my parents to bail us out. I haven’t taken my family on holiday for 10 years.

We’ve been screaming for years that brain development from zero to five is vital, so why are we the bottom of the pile every time? Why isn’t there a pay scale in line with teaching assistants? They don’t have to have the same level of qualifications that mine do. There’s no equivalent to teacher pay scales for us, so it’s hard to gauge where we should be.

We increase our staff’s wages in line with increases in the National Minimum Wage. Our assistants are on minimum wage and our L3s not much above that. This year we froze pay because not everybody was working due to COVID. However, we had to increase the L3s’ rate because otherwise they’d have slipped below minimum wage.

There’s a big hike next April to get us to £9, but that’s going to have a huge impact on our wages bill. The increases haven’t been in small increments, like 0.5% or 1%; they’ve been in big chunks like 4.5%. We have to find those, but our early years funding has only gone up 1%.

Most of us do this job for love, not money. But love doesn’t pay the bills.”

6.4 Work demands

Both the literature review and the interviews highlighted work demands as a source of job dissatisfaction and a possible cause of instability in the EY sector.

According to the APS, EY staff work significantly longer hours than some other groups in the study. Approximately 11% of EY workers reported working more than 42 hours per week, compared with 3% of retail workers, 6% of female workers and 13% of the total working population. Long working hours, especially when unpaid or underpaid, can reduce job satisfaction and lead to higher staff turnover.

Interview participants identified two specific dimensions of work demands: long hours of strenuous work ‘on the floor’ with the children, and demanding paperwork. Both were perceived to have been made worse by the way Ofsted scrutinises the sector.

They described how long hours and inadequate working conditions cause exhaustion and low morale, feeding a desire to leave EY for less-demanding work. Three problems worsen the issue. First, there is an expectation in the sector that staff will simply put up with long hours of physically tiring work. Second, because nurseries can operate at the minimum possible staff-to- child ratio, practitioners feel unsupported during long shifts. Third, resources to help children with additional needs or SEND are often lacking, meaning that individual members of staff have to carry the extra responsibility by themselves.

“There’s that element of ‘Is this worth it?’ It’s sucking all of my energy out and I’m getting a very small amount in return.” – Childminder, affluent/urban

In addition, practitioners reported often having to work long past their paid hours to complete paperwork, such as for EY Foundation Stage monitoring. This is particularly challenging for staff without strong literacy skills. Participants felt frustrated – believing that much of the paperwork is a formality that neither parents nor schools will use. Additionally, they believe that the demands of paperwork are keeping them from engaging with the children.

“The amount of paperwork we do for what we do is crazy. The worst thing is it takes staff away from actually interacting with the children.” – PVI practitioner, affluent/urban

There was a sense that scrutiny from Ofsted directly causes workers to leave the sector. Practitioners reported inspections leading to even longer working hours, more stress and yet more paperwork.

“There is that feeling with the thought of being inspected that all of a sudden someone is just going to say ‘Oh no, you’re doing it totally wrong and actually we’re going to say unsatisfactory and that’s going to be it.’ That’s not a nice feeling.” – Childminder, affluent/urban

Differences by regions

The national picture of long working hours is partially reflected across all regions. On average, one in nine EY workers from all regions reported working more than 42 hours per week, and this was also the case across rural and urban areas. There is greater regional variation in the proportion of workers working for between 31 and 42 hours, ranging from approximately half the EY workforce in the west midlands to just over a quarter of the EY workforce in the east midlands.

Differences emerge between rural and urban areas, with urban-area workers reporting higher numbers of hours. Some 31% of rural-area workers reported working between 31 and 42 hours per week, compared with 37% of urban-area workers. Also, a higher proportion of EY professionals in rural areas work between 0 and 30 hours (57% of workers in rural areas vs 51% of workers in urban areas).

Participants in deprived areas reported a high proportion of children with complex needs in their settings. This includes those with English as an additional language (EAL), with mental health issues or living in poverty. These conditions mean practitioners find their remit extended to supporting children’s families, which adds to pressure and workload.

“We’re essentially their social worker half the time.” – PVI practitioner, deprived/urban

Pressure and workload intensify where little additional support is available to staff. A teaching assistant in a nursery school described how the removal of a family outreach centre attached to the nursery had increased the volume and complexity of safeguarding work for practitioners.

“We’ve got so much going on with safeguarding … We … [are] trying to do the role that our outreach colleagues used to do.” – Maintained-setting practitioner, affluent/rural

Participants in deprived areas discussed how some Ofsted requirements are more difficult for them to meet, which increases pressure on staff and reduces job satisfaction. A practitioner in a deprived area in the north-west illustrated this with reference to parental engagement. They explained that parents’ reluctance to engage with school staff – driven partly by cultural and language barriers – is “stressful” for all practitioners.

“We try, but we can only do so much. We’re only one half, they need to work with us, so then we feel the pressure because even Ofsted have said parent partnership is not where it needs to be … it’s just like a losing battle.” – PVI practitioner, deprived/urban

The quantitative analysis also highlighted differences in working hours between areas with different levels of deprivation. In the most affluent areas approximately 16% of workers work more than 42 hours per week, compared with 9% of workers in the most deprived areas.

However, this is not unique to the EY sector, as 15% of the working population in the most affluent areas reported working more than 42 hours compared with 12% in the most deprived areas.

Differences by provider type