Review of the UK Material Deprivation Measures

Updated 12 April 2024

By Abigail McKnight, Irene Bucelli, Tania Burchardt and Eleni Karagiannaki

March 2024

DWP research report no.1049

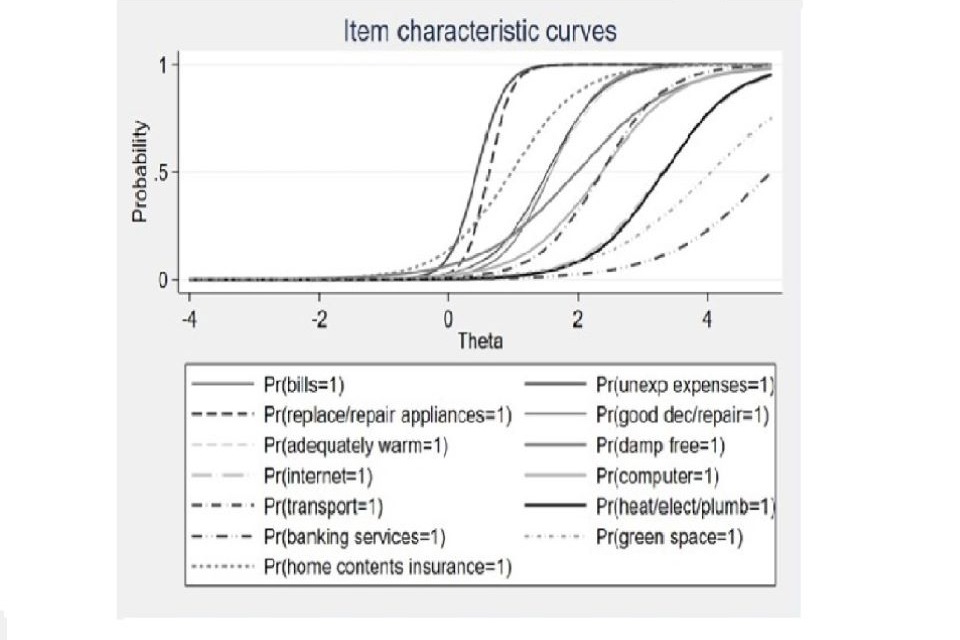

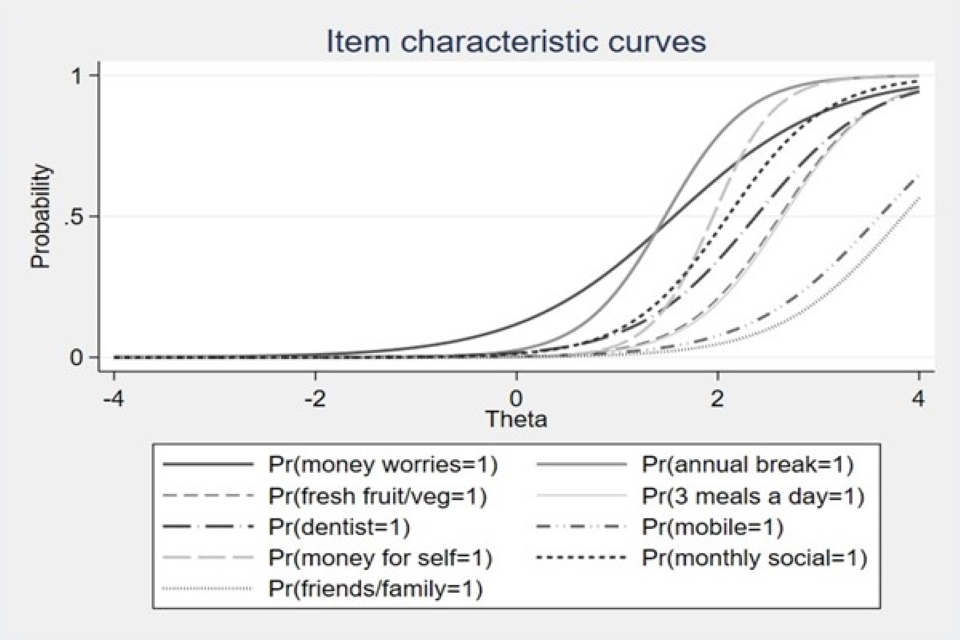

A report of research carried out by the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

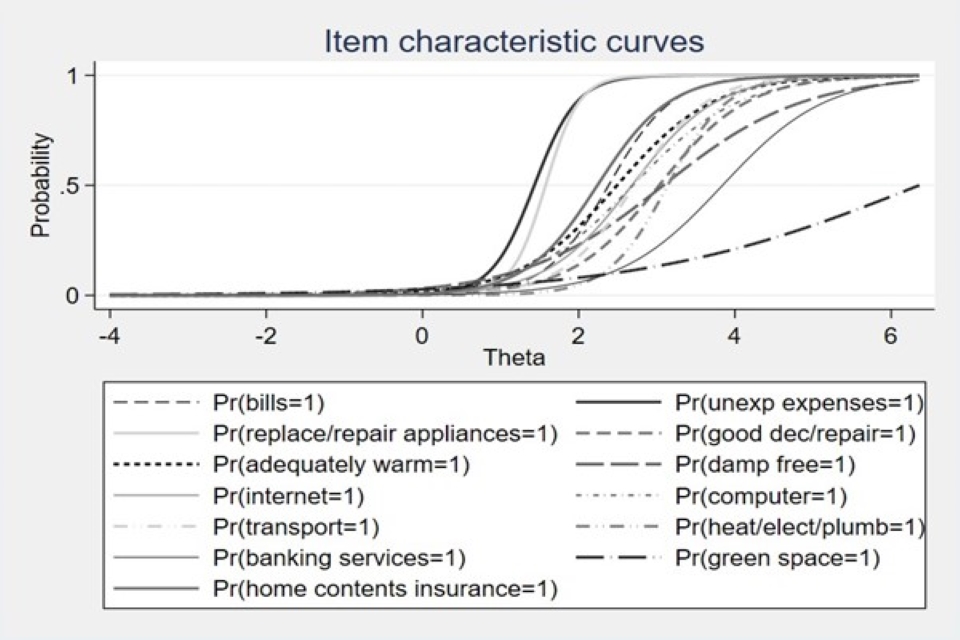

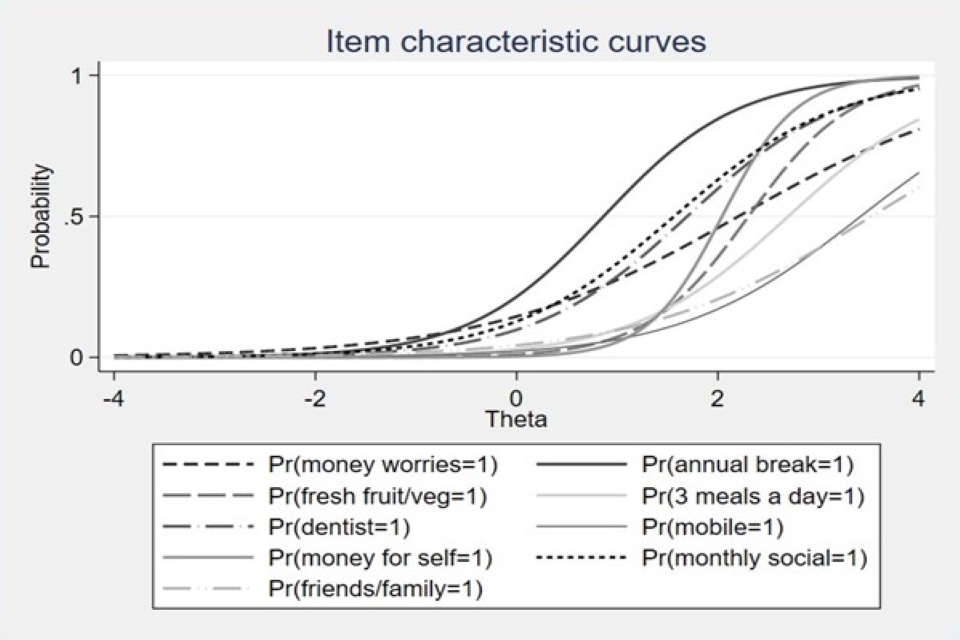

Crown copyright 2024.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit National Archives or write to:

Information Policy Team,

The National Archives,

Kew,

London

TW9 4DU

or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at: www.gov.uk

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published 21st March 2024.

ISBN 978-1-78659-651-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Acknowledgements

This Review was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and carried out by the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

The authors are grateful to the DWP project team who supported this Review, in particular Lottie Devaney for the positive and constructive approach she took to guiding the Review and working closely with the research team. We would also like to thank Grace Gibson, Antonia Ashworth-Davies, Michael Fini Henriques and Charlotte Harris, for their helpful input at various stages of the review. The DWP project tream provided feedback throughout, engaged in thoughtful discussion, sought additional information when required and provided helpful comments on various drafts of this report.

This research benefited from an engaged and experienced DWP steering group chaired by Elaine Squires and composed of Steve Ellerd-Elliott, Mike Elkins, Joanna Littlechild, Natalie Lloyd, Hilary Patel, Luke Staniland, and Mark Vaughan.

We would like to thank our project advisory group who provided invaluable advice and guidance to the project team throughout the Review: Matt Barnes (City University), Jonathan Cribb (Institute for Fiscal Studies), Paula Croal (Office for National Statistics), Paul Fishe (University of Essex), David Gordon (University of Bristol), Rod Hick (Cardiff University), Peter Matejic (Joseph Rowntree Foundation), Steve McKay (University of Lincoln), Jane Millar (University of Bath) and Veronique Siegler (Office for National Statistics).

We are grateful to the individuals who took part in a series of focus groups during January and February 2022. Their willingness to engage in thoughtful discussions on which items and activities should be regarded as necessities for an acceptable standard of living in the UK today, was invaluable. We would also like to thank Siôn Jones (Cardiff University) who led the focus group for Welsh participants, allowing us to offer a focus group for Welsh speakers.

Finally, the research team would like to thank the Family Resources Survey (FRS) project team for supporting the development of a bespoke FRS module to test material deprivation items and FRS interviewers for collecting the valuable information on these test items which underpin much of the analysis presented in this report. We are indebted to all the individuals who voluntarily take part in the FRS, giving up their time to facilitate the measurement of living standards in the UK and who agreed to respond to the test questions which underpin the recommended revisions to the UK material deprivation measures.

Executive Summary

This report contains the findings and recommendations from a review of the UK material deprivation measures. The review was conducted by the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics and Political Science and commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). This followed recommendations made by the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) to DWP to review the current set of questions which underpin UK material deprivation measures and determine a way to compare material deprivation across groups.

The aims of the review were to explore:

-

which material deprivation items for families with children, families with working-age adults and families with pensioners should be included in the Family Resources Survey (FRS)

-

the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches for determining who is materially deprived

-

the advantages and disadvantages of developing a core set of questions for the whole population alongside measures aimed at working-age adults, children and pensioners

-

whether the advantages of updating the material deprivation measures outweigh the disadvantages

Material deprivation is a widely recognised concept in the field of poverty analysis. It is a direct measure of poverty derived from the lack of items and activities deemed to be necessary for a minimum acceptable standard of living. In order for measures to capture contemporary material deprivation it is important that necessities included in measures are periodically reviewed to ensure they reflect public perceptions of necessities.

The report begins with a review of existing evidence on material deprivation. This is followed by findings from new qualitative research with focus groups to provide an up-to-date understanding of which items and activities are perceived to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living in the UK today. The evidence review, and qualitative research informed a short-list of items and test questions which were included in the FRS in April, May and June 2022. Results are presented from the analysis of the test question data to assess the suitability, validity and reliability of the test items, and the consistency and additivity of composite material deprivation scales. This led to recommendations for revisions to the UK measures. Although breaks in series make it difficult to analyse trends, the Covid-19 pandemic had already disrupted the series and the Review concluded that the benefits of revising the measures outweighed the disadvantages.

The revised measures include updating of individual-level items in the measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners and a core set of household-level items. Improvements to, and standardisation of, data collection methodologies underpin the revised measures, and the new questions were included in FRS 20232/2024. Finally, recommendations are made in relation to the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches to determining who is materially deprived and further research required to explore a whole population or household level measure.

Author credits

Abigail McKnight is Director of the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). She is as an economist and her research interests include poverty, multidimensional inequality, low wage employment, social mobility and the evaluation of employment policy. Abigail led the review of UK material deprivation measures.

Irene Bucelli is a Research Officer at CASE at the LSE whose research focuses on multidimensional inequality, poverty and deprivation, and is an experienced qualitative researcher. Irene was primarily responsible for conducting the focus groups, she also contributed to the evidence review, the shortlisting of items and activities for the revised material deprivation measures and the final recommendations.

Tania Burchardt is an Associate Director of CASE, and an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy at the LSE. Her research interests include concepts and measurement of poverty and inequality, both quantitative and qualitative, and applied welfare analysis. Tania played a significant role in the qualitative research, contributed to the shortlisting of items and activities for the revised material deprivation measures and the final recommendations.

Eleni Karagiannaki is an Assistant Professorial Research Fellow at CASE at the LSE. She has conducted research on a range of issues relating to poverty and inequality measurement and analysis with a particular focus on understanding how the tax and benefit systems, the labour market and families interplay to shape socio-economic inequalities. Eleni advised on the quantitative analysis, contributed to the shortlisting of items and activities for the revised material deprivation measures and the final recommendations.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Additivity tests | In the context of assessing the properties of material deprivation measures, additivity tests assess whether lacking more necessities included in a measure is associated with greater degrees of deprivation. |

| Benefit Unit | A Benefit Unit in the FRS (also sometimes referred to as a family by DWP) is defined as ‘a single adult or couple living as married and any dependent children’. A dependent child is aged 16 or under, or is 16 to 19 years old, unmarried and in full-time non-advanced education. This is a standard grouping used by DWP for assessing benefit entitlement. So, for example, a husband and wife living with their young children and an elderly parent would be 1 household but 2 families or benefit units. The husband, wife and children would constitute 1 benefit unit and the elderly parent would constitute another. |

| Constrained lack | Lacking an item or activity included in a material deprivation indicator due to a constraint, such as a financial constraint or a disability. |

| Factor analysis | Statistical methods used to identify sets of correlated variables related by common factors which are usually unobserved. |

| Family Resources Survey | The Family Resources Survey (FRS) is a continuous household survey which collects information from a representative sample of private households in the United Kingdom. |

| Item Response Theory | Also known as latent response theory, refers to mathematical models which seek to explain (test) the relationship between a latent trait (an unobserved characteristic or attribute – here material deprivation) and observed outcomes. |

| Latent trait or construct | Theoretical concept, characteristic or attribute which cannot be observed or measured directly. |

| Material deprivation | Material deprivation is a widely recognised concept in the field of poverty analysis. It is a direct measure of poverty derived from the lack of items and activities deemed to be necessary for a minimum acceptable standard of living. |

| Necessity | In this context, a necessity is an item or activity deemed to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living. |

| Prevalence | A measure of the frequency an item or activity (a necessity) is owned or enjoyed within a given population. |

| p-value | The probability value (p-value) is a measure of statistical significance. It provides a measure of how likely it is (under a null hypothesis) to obtain a test statistic value greater than the observed value by chance. Lower p-values denote higher estimated statistical significance. Commonly accepted cut-offs are p-values of 0.1, 0.05 or 0.01 (10%, 5% or 1%, respectively). A p-value of 1% can be interpreted as a 1% probability of estimating a statistical value completely by chance. |

| Reliability tests | These tests are used to assess if a set of candidate items and activities (necessities) included in a composite measure capture the same underlying concept. Reliability tests assess how closely related the candidate items and activities are as a group. |

| Simple absence | Lacking an item or activity included in a material deprivation measure (a necessity) for any reason. |

| Statistical significance | Is an indicator of how unlikely it is that a result is obtained by chance (to a specified degree of confidence). The significance level is the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis (for example, that there is no relationship between two variables), demonstrated by the p-value of the result. |

| Suitability tests | The suitability of candidate items and activities as indicators of material deprivation can be tested through estimating the share of survey respondents who agree that an item or activity is a necessity for a minimum acceptable standard of living. |

| Validity tests | These tests provide an assessment of whether candidate items or activities are valid indicators of material deprivation. Tests assess whether lacking candidate items or activities is associated with deprivation (proxy measures for material deprivation). |

Summary

This report reviews and makes recommendations for revisions to the measurement of material deprivation in the UK.

Material deprivation signifies a standard of living beneath a minimum acceptable level, positioned between destitution (where people lack basic necessities such as food and shelter) and a low but comfortable standard of living with sufficient resources to afford some luxuries. Material deprivation measures are classed as direct measures of poverty which are derived from the lack of items and activities deemed to be necessary for a minimum acceptable standard of living. Lack can be defined in terms of affordability, other barriers (such as disabilities) or simple absence. These ‘necessities’ can change over time due to changes in norms, average living standards, or technological and social change. In order for measures to capture contemporary material deprivation it is important that necessities included in measures are reviewed periodically to ensure they reflect public perceptions of necessities.

Specifically, the aims of the review were to explore:

-

which material deprivation items for families with children, families with working-age adults and families with pensioners should be included in the Family Resources Survey (FRS)

-

the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches for determining who is materially deprived

-

the advantages and disadvantages of developing a core set of questions for the whole population alongside measures aimed at working-age adults, children and pensioners

-

whether the advantages of updating the material deprivation measures outweigh the disadvantages

Research context

In December 2021, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics and Political Science to conduct a review of the UK material deprivation measures. This followed a recommendation from the Office for Statistics Regulation to review the current set of questions that underpin UK material deprivation, and to determine a way to compare material deprivation across groups (OSR, 2021).

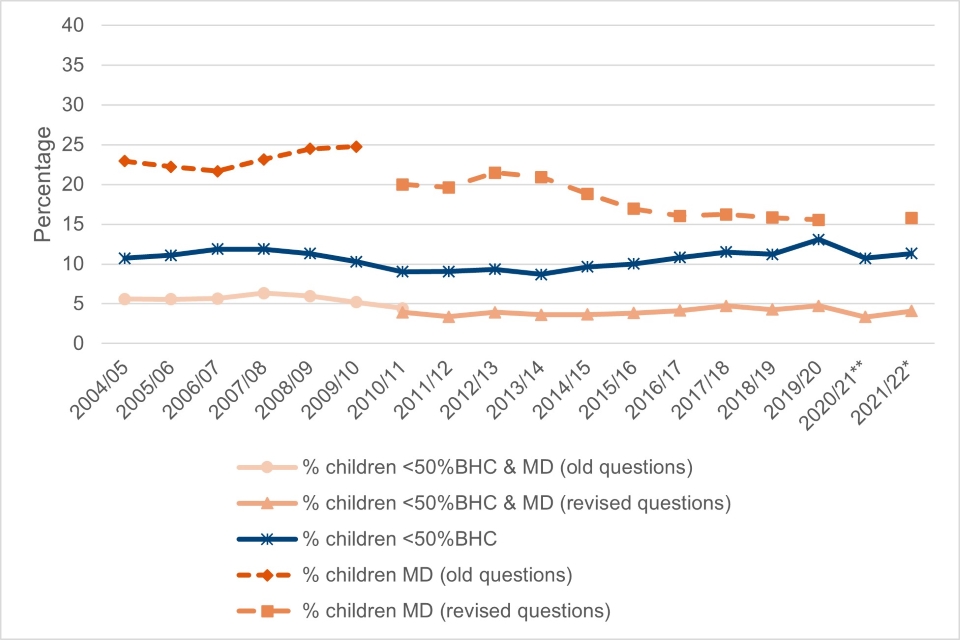

It is well over a decade since the items included in the UK material deprivation measures have been reviewed. The child material deprivation indicator was introduced in 2004/2005 and the last time changes were made to the items in this measure was 2010/2011. The pensioner material deprivation indicator was introduced in 2009/2010 and the items in this measure have not been reviewed since. A recently introduced material deprivation indicator for working-age adults is based the subset of adult items included in the child indicator, which remain unchanged since 2010/2011.

Structure of the review

The Review began with a rapid evidence review on material deprivation, focusing on the concept, its practical application and key aspects of material deprivation measures. This was followed by qualitative research with focus groups to provide an up-to-date understanding of which items and activities are considered to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living in the UK today.

The evidence review and qualitative research informed a short-list of items and activities and a series of test questions which were included in the FRS in April, May and June 2022. Analysis of the FRS test question data led to recommendations for changes to the items and activities included in the UK material deprivation measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners. Further recommendations were made to change the FRS question routing and a standard follow-up question used to establish why any of the items are lacked. These recommendations were accepted and changes were introduced in FRS 2023/2024. Finally, recommendations were made in relation to different methodological approaches for determining who is materially deprived.

Key findings from the evidence review

The foundations of the modern concept of material deprivation are commonly traced back to the work of Peter Townsend (1979) (Chapter 2). Key elements of Townsend’s theory are resource constraints leading to deprivation of necessities, a relative concept of poverty determined by societal norms and an understanding that standard of living extends beyond material goods. While the definition of material deprivation has evolved, these key elements remain at the core of the concept.

It is not possible to directly observe material deprivation, instead material deprivation measures include indicative items and activities which incur a financial cost and are considered to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living. Townsend simply measured whether or not individuals lacked items included in his measure (simple absence). Piachaud (1981) argued that judging deprivation on simple absence ignores the possibility that people may choose not to have these items. To take into account differences in tastes and preferences, he stressed the importance of distinguishing between people who lack items because they cannot afford them from people who don’t want them. This led to the now common practice of considering people to be materially deprived of such items if they lack them because they cannot afford them.

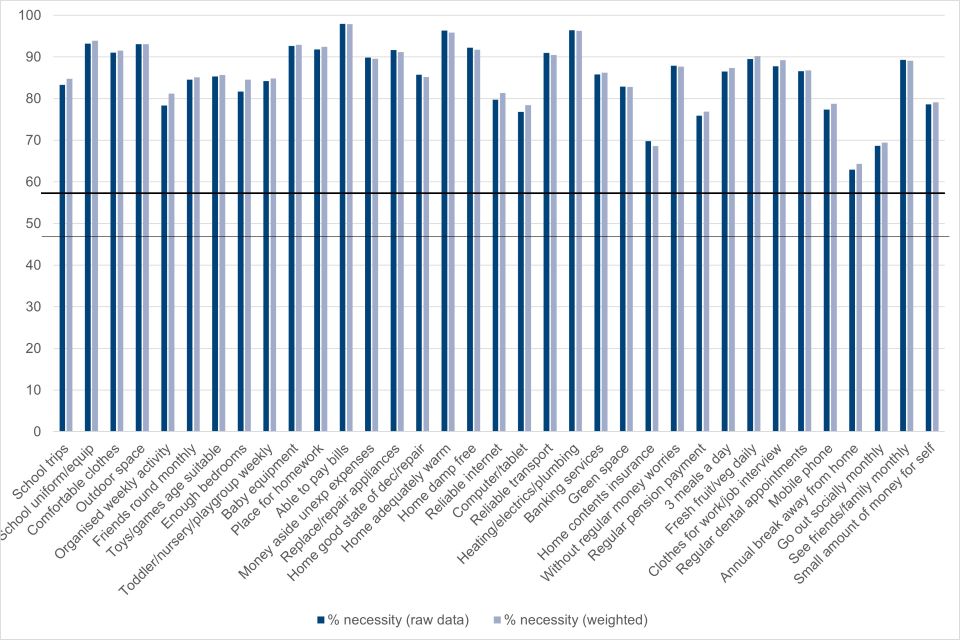

To establish which items should be classed necessities, Mack and Lansley (1985) stressed the importance of taking into account public perceptions. Qualitative research and survey evidence are now commonly used to identify candidate socially perceived necessities. Furthermore, an analytical framework has been developed to assess the suitability, validity and reliability of candidate items and activities, and the consistency and additivity of composite material deprivation scales (Guio and others, 2017). Outcomes from these statistical tests combined with expert judgement have been used to identify optimal sets of items and activities to include in material deprivation measures.

Some measures combine material deprivation with low-income status, producing a combined measure which excludes people who are classified as materially deprived but but have higher income. However, the combined measure rules out the possibility that people may still be deprived due to additional needs, other constraints or as a result of measurement error in income. In addition, it has been argued that it risks confusing two concepts and can be seen to contradict the basis for directly measuring low living standards.

Qualitative research findings and short-listing test items

In early 2022, a series of focus groups were held to help assess whether changes were required to the items and activities included in UK material deprivation measures (Chapter 3). Participants were drawn from across the UK, different age groups, income groups, ethnic groups, gender, household types and disability status.

A rapid review of the literature, drawing on evidence from a range of existing and previous approaches to measuring material deprivation, led to a long-list of 103 items and activities. These were classified into ten main categories: (1) Financial security, (2) Food, (3) Clothing, (4) Health, (5) Communications, (6) Mobility, (7) Home and living conditions, (8) Social and leisure activities, (9) Things for oneself, (10) Items and activities related to children.

Each focus group was structured around a series of polls covering items and activities selected from these categories. Participants were invited to indicate any of the items they thought were necessities which people should be able to afford for an acceptable standard of living in the UK today. The poll results were used as a starting point for in-depth discussions.

Following the focus groups, set criteria were used to select a short-list of items and activities. These were based on data collected in the focus groups, information from secondary data sources on prevalence and support for particular items or activities, the potential impact of variation in tastes, differences in cost and whether an item or activity is likely to be specialist for particular groups in the population. Finally, the relationship to other short-listed items or activities was considered along with relevant evidence from the rapid evidence review. The result was a recommendation to test a short-list of 35 items and activities.

The test questions were included in the FRS during April, May and June 2022. The first set of questions asked respondents to identify necessities from the short-list (necessities questions). A second set asked respondents if they lacked any of the short-listed items and activities (material deprivation questions).

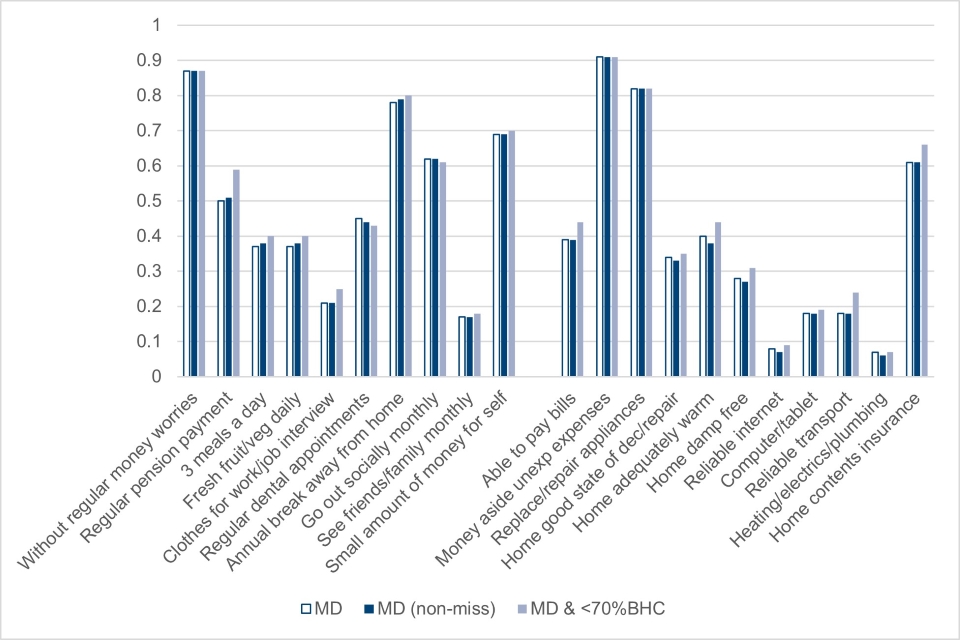

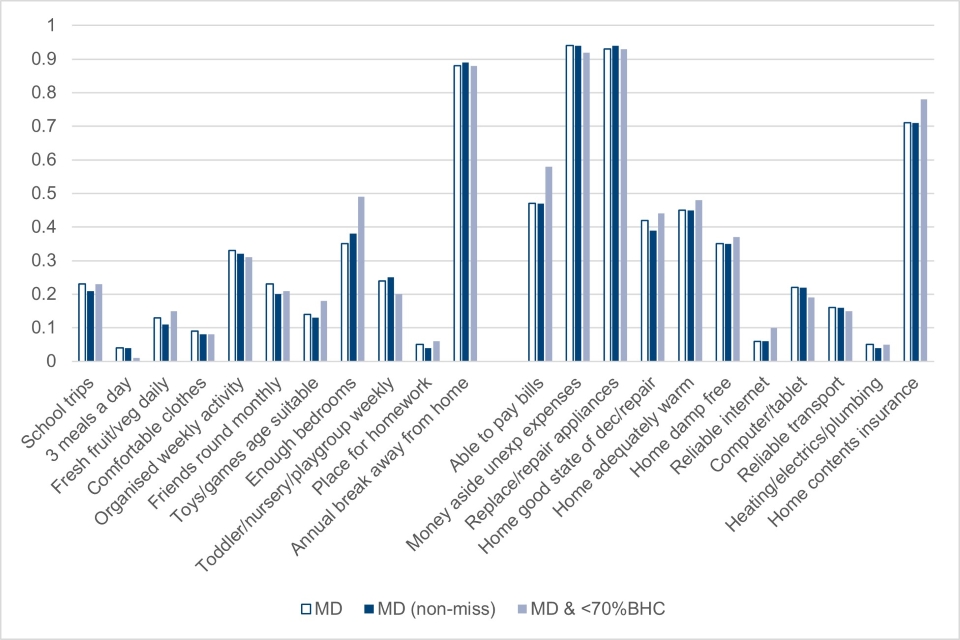

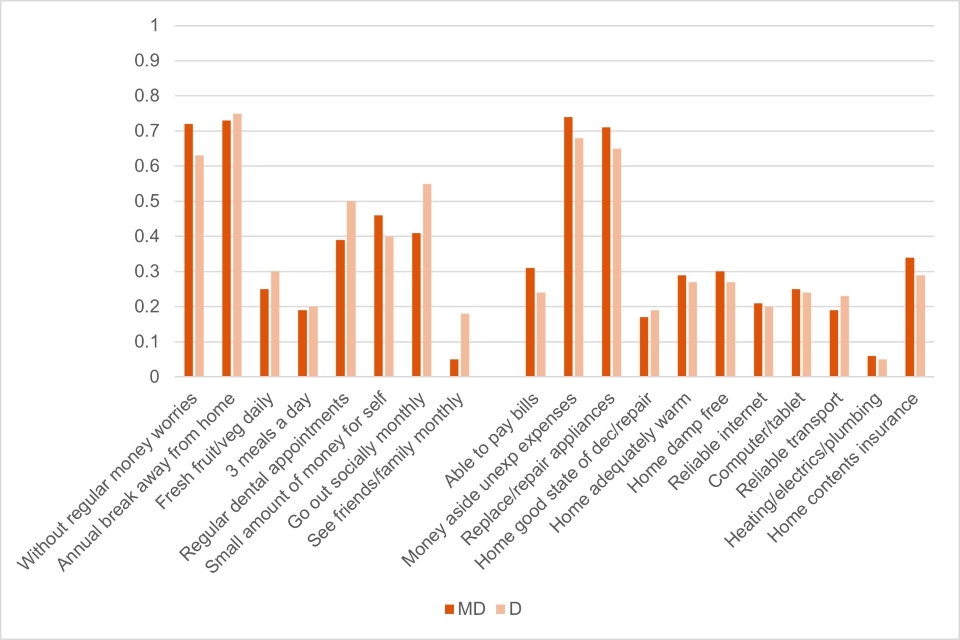

The FRS test questions included a number of changes to the way in which information on material deprivation is collected. Firstly, one adult member of each household responded to questions on a common set of 13 household-level items (Chapter 4). These items, such as whether the home is damp-free, apply to all members of a household and, therefore, do not need to be collected from more than one person. This reduces the survey burden relative to asking a representative adult in each benefit unit or multiple adults in mixed age BUs, improves comparability between age groups and potentially aids the development of a whole population measure. Secondly, a two-step method established whether respondents lacked any of the items or activities before asking why they lacked any using a standardised follow-up question. Previously, this two-step method was used for pensioners only following recommendations made prior to the pensioner measure being introduced in 2009/2010. The standardised question routing and options for why any item is lacked removes inconsistencies in the current data collection. The changes improve the data collection methodology, increase comparability between age groups and aid the potential for developing a whole population measure.

Recommended changes to the material deprivation items and case for change

Analysis of the FRS test question data informed a set of recommendations on which items and activities should be included in revised material deprivation measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners. This involved first establishing the suitability of items and activities based on responses to the necessities questions, then assessing the validity and reliability of individual items, and finally establishing the consistency and additivity of composite material deprivation scales based on responses to the material deprivation questions. Recommendations for revisions to the UK material deprivation measures were based on assessing the strength or weakness of individual items based on the test results combined with expert judgement.

Although breaks in series make it difficult to analyse trends, the Covid-19 pandemic had already disrupted the series in recent years and the Review concluded that the benefits of revising the measures outweighed the disadvantages. The main advantages were:

-

updating the necessities to items and activities which are perceived to be necessary for a minimum acceptable standard of living in the UK today

-

standardisation in data collection methodology

-

a core set of household-level items which reduces the survey burden relative to collecting this information from each benefit unit or multiple adults in mixed age BUs, increases comparability between age groups and, potentially, aids the development of a whole population measure

Recommendations for revisions to the material deprivation measures were accepted and new questions were included in the 2023/2024 survey. To aid an assessment of the impact of a break in the series, it was agreed to split the 2023/2024 FRS sample, with 75% of respondents asked the new material deprivation questions and 25% the previous questions. From 2024/2025, only the new questions will be included in the FRS.

The items and activities in the revised material deprivation measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners are shown in the tables below.

| Household-level | Working-age | Children | Pensioners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Able to pay bills without cutting back on essentials | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Able to put money aside for unexpected expenses | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cover cost of repair or to replace appliances | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Home in good state of decoration or repair | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Home adequately warm in cold weather | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Home damp free | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Reliable access to internet at home | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Access to computer or tablet | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adequate access to reliable transport | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Heating, electrics and plumbing in good working order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Home contents insurance | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual-level | Working-age | Children | Pensioners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three meals a day | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fresh fruit or vegetables every day | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Annual break away from home | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Without regular money worries | Yes | Yes | |

| Regular payments to workplace or private pension | Yes | ||

| Appropriate clothes for work or job interview | Yes | ||

| Regular dental appointments | Yes | Yes | |

| Go out socially at least monthly | Yes | Yes | |

| See friends and family at least monthly | Yes | Yes | |

| Small amount of money for oneself | Yes | Yes | |

| School trips | Yes | ||

| Enough clothes feel comfortable wearing | Yes | ||

| Organised weekly activity outside school | Yes | ||

| Friends round monthly | Yes | ||

| Age suitable toys or games | Yes | ||

| Enough bedrooms for children 10+ years | Yes | ||

| Toddler, nursery or playgroup at least weekly | Yes | ||

| Place for homework | Yes |

Notes: A full description of the items and activities can be found in Chapter 7.

Recommendations related to the strength of different approaches for determining who is materially deprived

The review also examined and made recommendations in relation to the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches for determining who is materially deprived. These were: 1) determining optimum deprivation score thresholds, 2) prevalence weighting, 3) combining material deprivation status with low-income, 4) using simple absence versus constrained lack.

1) Recommendations in relation to determining optimum deprivation score thresholds

(a) It was not within the remit of the Review to recommend optimum thresholds for the revised measures; data collected in the FRS for the first year, rather than the smaller FRS test question dataset, is required for this. However, the Review assessed different methodological approaches and recommended using a combination of statistical analysis and judgement to determine where the new thresholds are set. To provide full transparency to users, documentation detailing the decisions made, and why, should be published alongside the statistics.

(b) For the statistical modelling, we recommend DWP does not rely on household income alone to test which thresholds are best at discriminating between deprived and non-deprived groups. We recommend the development of a composite standard of living measure which could include information on savings, debts and food security, and recognises differences in needs/costs faced by different household types. For example, single parent households or where any household member has a long-standing illness or disability.

2) Recommendations in relation to prevalence weighting and type of material deprivation measure

(a) Given the lower complexity and greater transparency of simple count measures, we recommend additional research to establish whether such a measure would have led to substantially different estimates of material deprivation over the last decade. If not, we recommend moving to a simple count measure.

b) If prevalence weighting is continued, we recommend a number of items and activities should be given the maximum weight of one irrespective of prevalence rates. The degree of deprivation felt by lacking some items is very unlikely to be affected by prevalence. We recommend further exploratory work to assess the desirability of giving the maximum weight to a damp free home, keeping home adequately warm in cold weather, able to pay bills, three meals a day and daily fresh fruit and/or vegetables.

3) Recommendations in relation to combining material deprivation status with a low-income indicator

(a) To gain a clearer picture of poverty trends, we recommend that alongside the housing below average income (HBAI) low income series and the combined low income and material deprivation series (a legal requirement for the child poverty measure), DWP publishes new HBAI headline series on material deprivation alone. Currently DWP release this measure via their online dissemination tool, Stat-Xplore, including the standalone metric in the publication would also meet some users concerns about the combined measure conflating two concepts (low income and material deprivation).

(b) We recommend HBAI headline statistics for combined measures are based on after housing costs and not before housing costs income. This is a more realistic measure of the resources available to spend on necessities and consistent with other HBAI headline series.

4) Recommendations in relation to simple absence versus constrained lack

(a) Evidence suggests that adaptive preferences mean that people underreport financially constrained lack of necessities. We recommend further research to understand income gradients in people reporting that they, or their children, lack items or activities due to not wanting or needing them. This research could lead to the use of simple absence rather than constrained lack to establish deprivation for a wider set of items or activities.

(b) Parents may be more likely than children to report child-related items are lacked because children don’t want or need them rather than not being able to afford them. We recommend further research to establish the feasibility of asking children (aged 11+) directly about whether they lack items or activities, and the reason(s) why they lack any.

Recommendations on developing a core set of questions for the whole population alongside measures aimed at specific family types

Recommendations were accepted for a core set of household-level items in the revised measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners. The Review went further and assessed the advantages and disadvantages of developing a whole population, or household-level, material deprivation measure. The advantage of a whole population or household-level measure is that it would make it easier to compare rates of material deprivation between different age-groups as well as estimate population level rates. The disadvantage is that creating such a measure is likely to involve compromises which lead to less accurate estimates of material deprivation than the current age-group specific approach. Challenges were identified including lack of a consistent relationship between the individual-level measures and a measure constructed from household items alone. Therefore, we would not recommend moving to a measure based on household items alone, or combined with some individual-level items, at this point. If DWP wishes to pursue this further, the following work should be considered:

(a) For a measure based on the core household-level items alone, determine an optimum deprivation threshold, whether the measure should be based on wider constrained lack or financially constrained lack of items and whether material deprivation status should be combined with a low-income indicator.

(b) Assessing whether an alternative approach to defining household-level material deprivation could be based on whether any household member is classified as materially deprived according to the age-group specific measures which have passed statistical tests and validation from qualitative research.

(c) Exploring whether estimates from the age-group specific material deprivation measures can be added together and combined to provide valid whole population estimates.

Without further research, we recommend material deprivation is measured at the individual-level, based on the tried and tested measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners.

1. Introduction

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics and Political Science to conduct a review of the UK Households Below Average Income (HBAI) material deprivation measures. The project included reviewing the current set of items (necessities) included in existing measures to derive material deprivation status, the related questions included in the Family Resources Survey (FRS) and the methodology used to construct these measures.

It is well over a decade since the items included in the UK material deprivation measures have been reviewed. The official child material deprivation indicator was introduced in 2004/2005 and following a review in 2009, some minor changes were made to the items included in the measure from 2010/2011. The pensioner material deprivation indicator, for adults who have reached the State Pension Age, was introduced in 2009/2010 and the items included in this measure have not been reviewed since. A recently introduced material deprivation series for working-age adults (adults below State Pension Age) is based on a subset of items included in the child indicator which are relevant to adults. These items have remained unchanged since 2010/2011. In order for measures to best capture material deprivation it is important that the items from which these measures are derived are periodically reviewed to ensure they are perceived as necessities by the public.

Specifically, the aims of the review were to explore:

-

which material deprivation items for families with children, families with working-age adults and families with pensioners should be included in the Family Resources Survey (FRS)

-

the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches for determining who is materially deprived

-

the advantages and disadvantages of developing a core set of questions for the whole population alongside measures aimed at working-age adults, children and pensioners

-

whether the advantages of updating the material deprivation measures outweigh the disadvantages

The project began with a review of existing evidence on the concept of material deprivation and its measurement. This was followed by qualitative research with focus groups to help identify a contemporary list of necessities. The evidence review and qualitative research informed the selection of a short-list of items and activities which were tested in the Family Resources Survey during April, May and June 2022. Analysis of the FRS test question data combined with other evidence informed recommendations for changes to the items and activities included in the UK material deprivation measures for working-age adults, children and pensioners. Other recommendations were made related to FRS question routing and a standardised follow-up question used to establish the reasons why any of the items or activities are lacked. These recommendations were accepted and changes to the material deprivation questions are included in the FRS from 2023/2024. Finally, recommendations are made in relation to different approaches for determining who is materially deprived and the development of a whole population measure.

The report is structured as follows: Chapter 2 covers a review of existing evidence on material deprivation, Chapter 3 summarises findings from the qualitative research with focus groups, Chapter 4 presents the short-listed items and activities which were tested in the FRS, Chapter 5 contains the results from statistical tests on the test items and activities, Chapter 6 includes statistical test results on the core household-level items when considered alone, Chapter 7 presents the recommendations for changes to the items and activities in the UK material deprivation measures, Chapter 8 provides an assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches for determining who is materially deprived. It includes recommendations for further changes to the UK measures and more research to fill knowledge gaps.

2. Evidence review

This chapter contains a review of existing evidence on material deprivation focusing on the concept, its practical application and key aspects of material deprivation measures. It covers:

-

the foundations of the modern concept of material deprivation which are commonly traced back to the work of Peter Townsend. Key elements of Townsend’s theory of deprivation are resource constraints leading to deprivation of necessities, a relative concept of poverty determined by societal norms and an understanding that standard of living extends beyond material goods to include activities

-

how material deprivation is a standard of living beneath a minimum acceptable level, positioned somewhere between destitution (where people lack basic necessities such as food and shelter) and a low but comfortable standard of living with sufficient resources to afford some luxuries

-

how the measurement of material deprivation has evolved to take into account differences in tastes and preferences. This is to distinguish between people who lack items deemed to be necessities because they cannot afford them from people who lack them because they do not want them

-

the role of qualitative research to establish which items and activities should be deemed necessities through the use of interviews or focus groups to produce short-lists of socially perceived necessities rather than relying on expert judgement alone

-

the development of an analytical framework and testing criteria to inform the selection of necessities to include in material deprivation measures. These statistical tests assess the suitability, validity and reliability of individual items and activities, as well as the consistency and additivity of composite measures

-

the pros and cons of measures combining material deprivation with low-income status. Although there are seen to be some advantages to using a combined measure as it excludes the possibility of higher income individuals being counted as materially deprived, there are also some disadvantages. A main motivation behind the development of material deprivation measures was concern about flaws in income based measures. Combining low income status with material deprivation could be seen as contradictory and risks confusing two different concepts

2.1. Concept

Material deprivation is now a widely recognised concept in the field of poverty analysis. It is distinct from income poverty, multidimensional poverty or social exclusion, although related to all three. Each concept has certain advantages and are best viewed as complements, expanding our understanding of disadvantage and helping to inform policy. People are considered to be materially deprived if they lack ‘necessities’. Necessities include items (goods, activities, services and amenities) for which a lack of is understood to indicate deprivation.

The foundations of the modern concept of material deprivation are commonly traced back to the work of Peter Townsend (1979, 1987). In Poverty in the United Kingdom, Townsend set out a theory of relative deprivation:

Individuals, family and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or are at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong. Their resources are so seriously below those commanded by the average individual or family that they are, in effect, excluded from ordinary living patterns, customs and activities. (Townsend, 1979, 31)

Key elements of Townsend’s theory are resource constraints leading to deprivation of necessities, poverty being a relative concept determined by societal norms and an understanding that standard of living extends beyond owning material goods to include activities and amenities. While the definition of material deprivation has evolved, these key elements remain at the core of the concept.

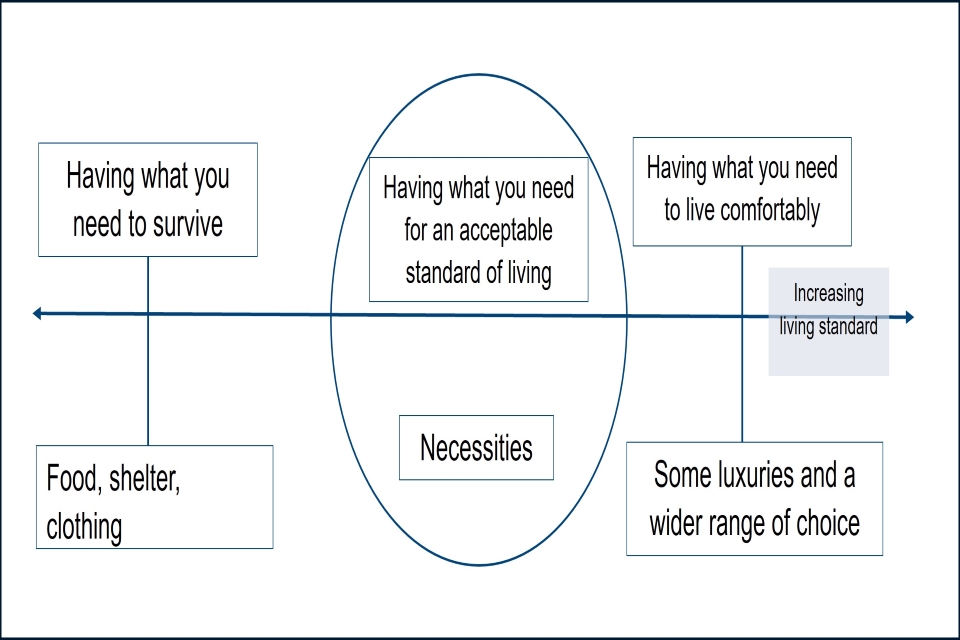

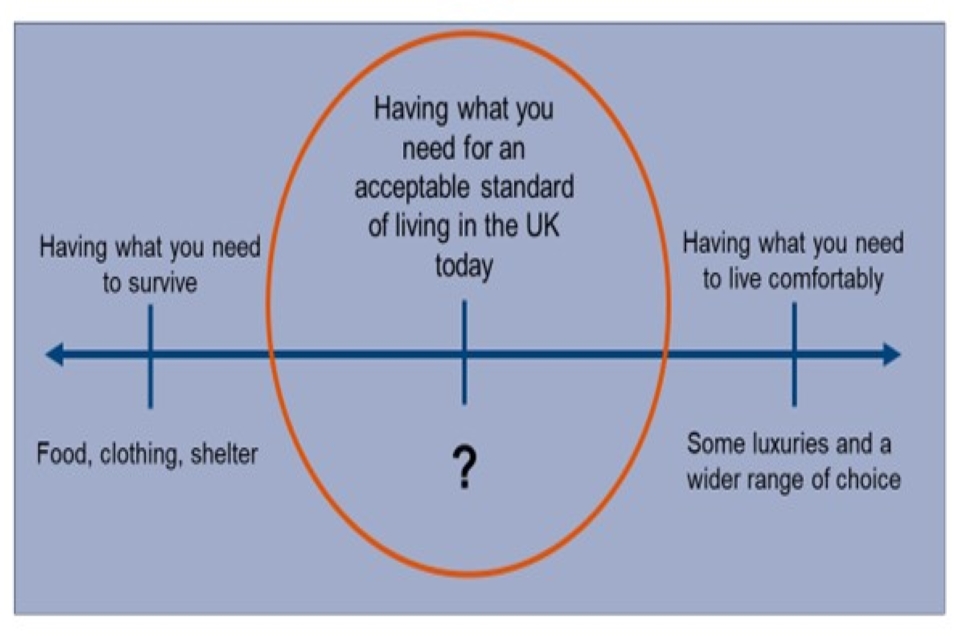

In the study of material deprivation, it is important to identify a standard of living which is beyond survival or subsistence as there is more to life than just living (Mack and Lansley, 1985; 57). Figure 2.1 shows a visual representation of the position of material deprivation on a standard of living scale. Standard of living can be thought of as a continuum from very low levels to very high levels, with the material deprivation threshold defined in terms of a level which constitutes a minimum acceptable standard of living. The threshold is positioned somewhere between destitution where people lack very basic types of necessities such as food, clothing and shelter and a low but comfortable standard of living with sufficient resources to afford some luxuries.

Figure 2.1: Material deprivation relative to destitution and comfortable living standards

Source: prepared by the authors

Considering where the threshold lies is important for understanding the concept and, as explored further in Section 2.2, in operationalisation (the process of defining the measurement) and measuring material deprivation.

What sets material deprivation apart from multidimensional poverty and social exclusion is the focus on resource constraints leading to deprivation. That is not to say that resource constraints are not an important element or driver of multidimensional poverty or social exclusion, but from a material deprivation perspective, necessities only include items with a monetary value. In contrast, multidimensional poverty or social exclusion measures tend to include non-monetary indicators, or items or services for which individuals do not directly pay for at the point of need or use. A further key difference between material deprivation and social exclusion is in the dimensions they cover. For social exclusion, a broader range of dimensions is appropriate, including health and education, while material deprivation indices focus on material living conditions (Guio and Engsted Maquet, 2007). Examples of non-monetary items in multidimensional poverty measures include education outcomes such as low levels of education attainment (see, for example, Alkire and Foster, 2011) and social exclusion can include indicators of political engagement such as voting in elections (see, for example, Burchardt, Le Grand and Piachaud, 1999).

Using information on lack of necessities to calculate a relative deprivation score, Townsend sought to identify income thresholds beneath which people living in different household types are disproportionately deprived (Townsend, 1979, 258). The results were mixed but he found some evidence of deprivation threshold income levels for different types of households, all of which were above benefit levels in place at the time.

This approach of using information on deprivation of necessities to identify an income poverty threshold provides a measure of minimum standards of living. A number of measures have developed this approach further including budget standards and minimum income measures based on the cost of baskets of goods required to achieve a minimum standard of living (see, for example, Deeming, 2005). The UK Minimum Income Standard, first developed by Bradshaw and colleagues (Bradshaw and others, 2008) with funding from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, identifies a set of necessities, estimates the cost of these necessities and calculates the minimum level of income required to pay for them.

More than one minimum income threshold can be set for different types of household. Households with income below the relevant threshold are unable to meet this minimum standard of living. A key difference between minimum income standards and material deprivation is that material deprivation measures focus on whether or not people are deprived of a selection of indicative items which have a monetary value and have been deemed to be necessities. In contrast, the minimum income standard approach calculates the cost of achieving a minimum standard of living identified in terms of a full set of necessities and then converts this cost into an income threshold.

2.2. Practical application of the concept and the identification of necessities

Material deprivation falls into the class of ‘direct’ measures of poverty which seek to establish standards of living through directly asking people about how they live and what they have. In contrast, income-based measures of poverty have been described as indirect measures, or proxy measures (McKay, 2004, Ringen, 1988). Ringen argues that income is not a reliable measure of poverty defined in terms of low consumption (Ringen, 1988, 359).

The challenge to measuring material deprivation is that it is a latent construct, a theoretical concept, which means it cannot be observed directly or measured directly. It is also multi-faceted as Townsend’s definition of relative deprivation highlights, which adds to the complexity. Measurement involves identifying an optimal set of indicators that reflect the latent construct and devising a measure which brings together information across these indicators.

Townsend used a household survey to collect information on 60 indicators reflecting ‘style of living’. These covered: diet, clothing, fuel and light, home amenities, housing and housing facilities, the immediate environment of the home, the characteristics, security, general conditions and welfare benefits of work, family support, recreation, education, health and social relations (Townsend, 1979, 249). For ‘illustrative purposes’, Townsend identified a set of 12 items for which going without any of these was seen as an indicator of relative deprivation. He summed across the following 12 items to compute a relative deprivation score:

- A week’s holiday away from home in last 12 months.

- (adults) A friend around for meal or snack in last 4 weeks.

- (adults) To go out with a relative or friend for a meal or snack in last 4 weeks.

- (children under 15) A friend around to play or for tea in last 4 weeks.

- (children) Party on last birthday.

- An afternoon or evening out for entertainment in last 2 weeks.

- Meals including fresh meat (including meals out) at least 4 days a week.

- Not going without a cooked meal one or more days in past 2 weeks.

- A cooked breakfast most days of the week.

- A refrigerator.

- Usually having a Sunday joint.

- Sole use of 4 amenities indoors (flush WC, sink or washbasin and cold water tap, fixed bath or shower, gas or electric cooker).

Townsend does not explain the criteria used for selection of the 12 items in his summary index which appears to be based solely on Townsend’s ‘expert judgement’ (Piachaud, 1981, Mack and Lansley, 1985). However, Townsend does say that the index is for illustrative purposes and acknowledged that more analysis was required (Townsend, 1979, 251), and picked up on this point in later work (Townsend, 2000; 17).

Key criticisms of Townsend’s construction of the summary index are that the selection of items was arbitrary and that he did not take into account ordinary people’s views on which items should be regarded as necessities. Mack and Lansley (1985) argued that public perceptions of which items are necessities should be incorporated into the development of a relative deprivation measure. In their Poor Britain study, a nationally representative sample of adults was asked to select from a list of 35 items which they thought were necessary and people should be able to afford, or not necessary but may be desirable (Mack and Lansley (1985, 50). Survey evidence established that the majority of people in 1980s Britain saw necessities to include a wide range of goods and activities reflecting a socially established minimum standard of living above mere survival or subsistence (Mack and Lansley, 1985, 53). Mack and Lansley used the survey evidence to derive a deprivation measure made up of 26 items (out of the original 35 items) which had been identified as ‘necessities’ by the majority of respondents using a simple 50% threshold (Mack and Lansley, 1985, 88).

This approach, asking the public in a survey which items from a list of candidate items, they regard as necessities for a minimal acceptable standard of living and only including those which are supported by the majority, has become known as the ‘consensual approach’ to identifying necessities and is now widely used (see, for example, Saunders, Naidoo and Griffiths, 2008, Abe and Pantazis, 2014). Despite widespread adoption of this approach, some experts have questioned whether this method really identifies a consensus (McKay, 2004, Walker, 1987, Halleröd, Bradshaw and Holmes, 1997). Halleröd, Bradshaw and Holmes (1997, 215) take issue with the use of the term ‘consensus’ as Mack and Lansley only require 50% of survey respondents to regard items to be necessities while a consensus implies that everyone is in agreement. In addition, the rule that an item needed support from at least 50% of respondents is set by Mack and Lansley and the 50% cut-off is ultimately arbitrary (Halleröd, 1994). Halleröd, Bradshaw and Holmes (1997) also highlight the problem that the closer a person’s choices are to the average choice (the so-called consensus ranking of items), the less likely that person will be classified as deprived because they prioritise the short-listed ‘necessities’ over other items. In contrast, a person who prioritises items deemed to be non-necessities over items classified as necessities, the more likely they are to be classified as deprived (Halleröd, Bradshaw and Holmes, 1997, 215).

McKay (2004) finds only limited agreement among survey respondents on which items, selected from a short-list of candidate necessities, are necessary and families should be able to afford. He found that the total number of items identified as necessities varied widely between survey respondents and, although the average number of items identified as necessities was similar between population sub-groups (for example, between men and women), within group variation was high. Based on findings from statistical tests, McKay concludes that there is a relatively low overall rate of agreement on which items are regarded as necessities. He also found marked variation between social classes with some classes expressing much stronger support than others for particular items to be regarded as necessities. McKay (2004, 214) appears to support Halleröd (1994) and Halleröd, Bradshaw and Holmes (1997) who proposed either abandoning the majority-view method for short-listing necessities from a longer-list of candidate items and simply using all of the candidate items, or using all candidate items but weighting each item by the share of respondents regarding it to be a necessity. Halleröd (1995) used this weighting system for his direct measure of poverty in Sweden. However, measuring material deprivation using the longer list of items faces the same criticism levelled at Townsend’s approach as it relies on experts’ judgements on which items to include on the list. An alternative is to combine these judgements with qualitative research but it is hard to see what objective basis could be used to select items and if a ‘consensus’ approach is sought, for example in focus groups, whether this produces a ‘better’ outcome. In addition, a much longer list of items leads to a more complex assessment of deprivation.

McKay (2004, 214) also questions whether necessities are really being identified due to what appears to be inconsistent expenditure decisions. The underlying assumption is that people first spend limited resources on securing necessities before paying for luxuries. As we saw earlier, the concept of material deprivation in relation to living standards is that it is positioned somewhere between destitution and living comfortably (being able to afford some luxuries and having more choice). McKay (2004) finds that 99.8% of respondents to the Millennium Survey of Poverty and Social Exclusion (PSE) who reported that they are unable to afford two or more items classified as necessities, had one or more of the 19 items that had not met the criteria to be classified as necessities (i.e. non-necessities).

What appears to be contradictory behaviour could, in part, be due to differences in assessments of what is and what is not a necessity. For example, car ownership was deemed not to be a necessity because less than 50% of respondents perceived it to be so. However, a car is clearly a necessity for some people, such as those living in rural areas lacking good public transport links, or people who need a car for work, or because they or a family member has limited mobility, or some other factor which makes owning a car essential. Indeed, McKay finds that there is a strong correlation between car ownership and cars being regarded as essential and a strong relationship overall between having an item on the longer list of candidate necessities and rating the item a necessity (McKay, 2004; 216). This means that owning a car while not being able to afford two or more of the items deemed by a simple majority to be necessities cannot be seen as proof that people are ranking luxuries before necessities.

It is also important to understand that items in the longer list of candidate necessities which did not meet the 50% support criteria, can hardly be described as luxuries. Perhaps the best way to describe these items is ‘near-necessities’ as they had met criteria used by analysts to be regarded as candidate necessities. We should be more concerned about people having items which are objectively luxuries, such as a new top of the range car, multiple holidays abroad every year, the latest top brand mobile phone, a heated swimming pool, a second home, etc., while reporting that they are unable to afford items classified as necessities.

It might also be better, or at least less contentious, to refer to necessities identified using these methods as ‘socially established necessities’ (Mack and Lansley, 1985; 59, use this description but also describe the method they use as a consensus based approach) or ‘socially perceived necessities’ (used by Bradshaw, 2008; Hirsch, 2015 and others) rather than ‘consensus based necessities’ which risks over-claiming a clear consensus.

Some measures, such as the official UK material deprivation measures, weight deprivation of items by prevalence of people possessing them; thus giving a higher weight to items which are commonly owned (DWP, 2023a). The assumption is that lacking something more people have, indicates a higher level of deprivation (and vice versa) (Halleröd, 1994). Using such a method helps to address concerns about giving all necessities equal weight and addresses some of McKay’s concerns.

Weighting items by prevalence can also help to reflect changes in preferences or needs particularly in material deprivation measures for which component necessities are updated infrequently. Weights increase over time for items which become more commonly held, reflecting an assumption that deprivation associated with lacking these items also increases. For example, not being able to afford a mobile phone when virtually everyone else has one leads to a higher deprivation score than when having a mobile phone was less common. A more questionable feature of using prevalence scores as weights is that during economic recessions when living standards fall, the prevalence of certain items is also likely to fall, leading to lower weights and lower deprivation scores.

Material deprivation is a relative measure and it is therefore right that reference is made to typical living standards, which can fall, but people’s views on what is a minimum acceptable standard of living might not change. Therefore, putting lower weight on, for example, not being able to afford to replace or repair domestic appliances just because more people cannot afford to do so can be considered a flaw.

Another option is to weight each item according to the share of people who consider it to be a necessity. Giuo (2009) calls these consensual weights with higher weights for items given greater social importance. Using European data, Guio (2009) shows that applying national prevalence weights or consensual weights leads to a reduction in estimates of material deprivation relative to unweighted estimates. Prevalence weights were found to reduce material deprivation estimates as the lowest weights are given to the items which people are most likely to lack.

The share of people wanting items (‘degree of importance’), has been used in the development of material deprivation measures to identify necessities where information on perceptions of which items should be considered necessities has not been available (Guio and others, 2017). For example, this method was recently used in the revision of the EU measure of material deprivation where a 70% threshold was used to determine item suitability (Guio and others, 2017). The share of people wanting items was estimated using survey data based on the share of people reporting they owned an item added to the share of people reporting that they would like to have the item but lacked it because they could not afford it.

Although Mack and Lansley (1985) introduced a method for improving the selection of items included in material deprivation measures through directly asking the public to help identify necessities, there remained questions regarding the arbitrary nature of constructing the longer list of candidate items to choose from. As outlined above, Townsend chose a long list of items to reflect a number of key dimensions which were considered to be important but beyond this judgement no specific criteria was used.

For the Poor Britain study, Mack and Lansley selected 35 items representing a ‘cross-section of household’s social and personal lives, including food, heating, household durables, clothing, housing conditions, transport and leisure and social activities’ (Mack and Lansley, 1985, 50). Items included heating to warm living areas of the home if it is cold, public transport for one’s needs, a refrigerator, two hot meals a day (for adults), a garden, children’s friends round for tea or a snack once a fortnight and a packet of cigarettes every other day. It is not clear what selection criteria they used to decide which items to include on this list which is crucial as items not included cannot be identified as necessities, and cannot feature in the final list of items used to determine who is materially deprived. Halleröd criticised the arbitrary nature of the long list “…it was Mack and Lansley who made the initial selection of those items which might be regarded as necessities. The respondents did decide which items from the list were necessary but they did not decide the range of items from which they could choose.” (Halleröd, 1994, 3).

In recent years qualitative research has been used to improve the selection of items to include on the longer list of candidate necessities. For example, Hirsch and Smith (2010) used qualitative research to help inform the revision of the UK child material deprivation measure. Qualitative research with focus groups which bring together people from a range of backgrounds (including those with direct experience of poverty) to deliberate on what items might be regarded as necessities has been used to help inform candidate necessities.

Participants can be provided with briefing material in advance including the definition of material deprivation, illustrative examples of necessities, guidance on how the focus group will be conducted, and the purpose and aims of the focus group. For example, this can include how the information will be used, whether the aim is to reach a consensus or simply to gather a range of views, etc. The advantage of this approach is that the final list of candidate policies is not limited by the items which experts have identified as it can include additional items suggested by focus group participants. In addition, if there is no, or relatively little, support for some items these can be excluded from the list of candidate items included on the survey.

One issue is that a small number of studies have become very influential, leading to researchers and statisticians using the same points of reference for informing lists of necessities. For example, findings from the 2012 Poverty and Social Exclusion study have been used to inform the revised EU material deprivation measure (Guio and others, 2016, 2017), the new EU child material deprivation measure and a measure for Canada (Notten and Kaplan, 2021). Very similar lists of necessities could be due to studies establishing universally perceived necessities in high and middle income countries but qualitative research could help ensure that candidate lists are kept up-to-date and reflect different contexts which can change over time.

2.3. Dimensions of deprivation

Existing material deprivation measures make reference to different dimensions of living standards or different types of consumption. In this section we review how these dimensions have been identified and evolved between different measures.

There is a rich literature focused on understanding the structure of deprivation, often linked to the development of specific measurement instruments. Identifying the importance of different dimensions has often involved the use of statistical methods such as factor analysis. Factor analysis involves applying statistical methods to identify sets of correlated variables (items) related by common factors which are usually unobserved. This literature is helpful to ground and justify the use of distinct indicators. Townsend considered relative deprivation to relate to the “conditions, obligations, expectations and customs of today” in the different “spheres of social life” (Townsend, 1993, 37). This means that material deprivation “arises in different social settings and needs to be understood and explained in relation to these settings” (Townsend, 1979, 433).

As a result, Townsend sought to include all the major areas of personal, household and social life in a survey of standards of living in the UK carried out in 1968/69, covering work to school and home life, community and neighbourhood environment. He used 60 indicators which, outlined in Section 2.2, were structured around diet, clothing, fuel and light, home amenities, housing and housing facilities, the immediate environment of the home, the general conditions and security of work, family support, social relations, recreation, education and health. Some of these dimensions of deprivation encompassed a greater number of indicators compared to others, for instance twelve indicators related to conditions at work, nine to household facilities, while only one indicator related to education and two to recreational activities. This breadth of dimensions of deprivation, however, was significantly reduced in the summary deprivation index. In fact, Townsend’s summary index only covered three dimensions and twelve items, six of which related to social and recreational activities (including two alternative versions for adults and children), four food items and two items related to household facilities and amenities.

As discussed in Section 2.2, subsequent work by Mack and Lansley (1985) questioned Townsend’s summary list, noting that the process by which the twelve items were chosen was not clear. In face of this lack of clarity, the inclusion of items such as “having a cooked breakfast” over, say, “being able to buy new clothes” appeared arbitrary. Mack and Lansley’s ‘consensus based approach’ in the first Breadline Britain study, led to a list of necessities which expanded the dimensions covered compared to Townsend’s summary index, while seeking to focus solely on those aspects of social life “facilitated by access to money” (Mack and Lansley, 1985; 44). This meant, with reference to Townsend’s initial longer list of indicators, that Mack and Lansley included areas such as food, heating, clothing, consumer durables, entertainment, leisure and social activities, as well as services provided at least in part by the public sector such as housing and transport. They did not, however, include public services which they considered “not in the main paid for” such as health and education, and they excluded any indicator related to conditions at work, as this “is not an aspect of life that could readily be improved by higher pay” (Mack and Lansley, 1985; 45).

Following a similar approach, research in other countries such as Ireland also stressed the importance of focusing on items with a monetary value – again excluding items related to universally, publicly provided services such as health and education, and specifying in relation to social activities that these pertained to “something that costs money” (Callan, Nolan and Whelan, 1993). Overall, subsequent measures have largely retained the focus of the dimensions chosen by Mack and Lansley.

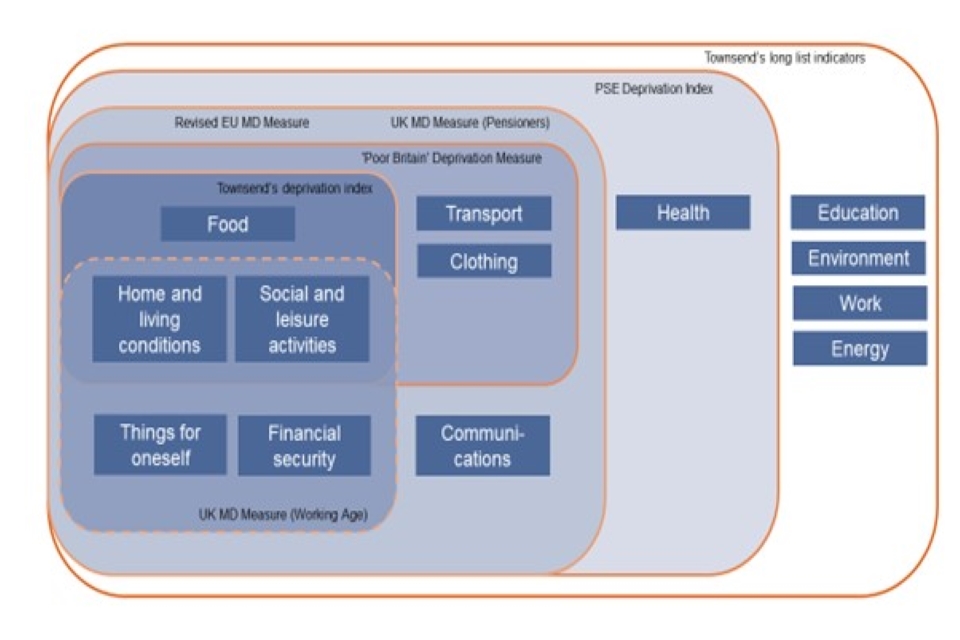

Mack and Lansley’s work informed the Poverty and Social Exclusion (PSE) surveys conducted in 1999 and 2012. The PSE surveys explored both people’s perceptions of necessities and their living standards. In the 2012 iteration, the PSE survey included more questions and encompassed more dimensions than the Breadline Britain surveys or the Townsend deprivation index. After testing 76 items (30 for children and 46 for adults), 25 items and activities for adults and 24 for children were identified as essential by a majority of people and 44 were included in the final PSE deprivation index (Gordon, 2017). Figure 2.2 gives a summary of the dimensions included in the main measures covered thus far (excluding items and activities related to children) as well as those relevant to the UK material deprivation measures based on questions included in the Family Resources Survey (FRS), and the EU measure based on the material deprivation module in EU-SILC (discussed below). The items and activities included in the UK and EU measures can be found in Appendix 1.

Figure 2.2. Dimensions of deprivation used in a selection of material deprivation measures

Source: prepared by the authors

Information from the PSE 1999 survey informed the development of the material deprivation questions to include in the Family Resources Survey (FRS) (McKay and Collard, 2004, McKay, 2008). McKay and Collard (2004) drew on the adult and child questions included in the PSE survey and tested them to identify a shorter list which could feasibly be incorporated in the FRS to inform a UK measure, while maintaining the ability to identify most of the same people as deprived. They used factor analysis to study the underlying structure of the data in the PSE 1999, the ONS Omnibus Survey (1999), the Families and Children Study (1999 to 2002) and the British Household Panel Survey (2001, wave 10). The authors identified some common dimensions, such as family and social life (for example, having an evening out, going to the pub, having a meal out, visiting family or friends), having sufficient disposable income (for example, including for holidays or to spend on oneself, savings, to use for repairs), food and clothes, durable goods and financial difficulties (for example, related to debt problems or the ability to keep up with financial commitments).

Material deprivation questions included in the FRS from 2004/2005, spanned four dimensions for working-age adults, namely financial security (savings, keeping up with bills and regular debts, household content insurance), social and leisure activities (holidays), things for oneself (money to spend on oneself) and home and living conditions (keeping the house warm, in a good state of decoration and replacing furniture and major electrical goods). A question related to clothing (two pairs of all-weather shoes) was dropped in 2010/2011 following a review of the child material deprivation measure. A separate suite of questions was introduced for pensioners in 2008 (Legard and others, 2008, McKay, 2008), and covered a range of dimensions with questions related to food, clothing, transport and communications. Items related to health (e.g. going to dentists, opticians, purchasing over the counter medicines) were considered but ultimately not included.

The development of the EU material deprivation measures also built on Mack and Lansley’s work. The key challenge for any measure of material deprivation at the EU level is that what is regarded as acceptable living standards depends largely on the general level of social and economic development, and this tends to vary across EU countries. Cultural differences can further complicate the exercise of understanding what is ‘the norm’ across different societies. This means that items selected for EU indicators need to reflect ordinary living patterns common to a majority or large part of the population in the European Union and most of its Member States (Guio and Engsted Maquet, 2007). Guio and others, (2016, 2017) reviewed the items included in the original 9-item EU material deprivation measure and using data from a special module included in the 2013 wave of EU-SILC, they recommended a revised measure made up of 13 items; six were retained from the original measure and seven were new. Of these items two each relate respectively to clothing, food, financial security, home and living conditions and social and leisure activities, one to communications (computer and internet), transport (car) and things for oneself (some money for oneself). Items tested included some outside these dimensions, for instance in relation to the neighbourhood environment, but these were ultimately excluded.

The final selection of items was informed by a series of statistical tests on item(s) suitability, validity, reliability and additivity. Items related to access to services (bank/postal services, transport), housing (darkness, housing costs, overcrowding), environment (pollution, crime, noise, litter, vandalism) and some consumer durables (TV, telephone and washing machine) failed on reliability grounds (with TV and telephone also failing on validity grounds).

Cross-country reviews of material deprivation measures (Boarini and D’Ercole, 2006, Kenworthy, 2007) covering OECD countries including Australia, Canada, Japan, EU countries, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States in the early 2000s are helpful as they show how some core dimensions have long been included in material deprivation measures. For instance, food and housing conditions are areas most measures covered. Owning certain durables was also widely included with items such as a telephone or a car largely being the sole indicators for transport and communication dimensions.

As already noted, recent updates of some of the measures, such as the EU measure, have included a wider set of items pertaining to internet access and computer use than in earlier studies. Aspects of financial security (for example, not being in arrears with utility bills, rents or mortgages and being able to save) have also been long used in most countries. Questions referring to subjective experiences are less frequently used, for instance in relation to food insecurity or the ability to make ends meet. Measures of reliance on social networks to cover essential expenses or debts are also less common, but can be found as indicators in countries such as the US, Australia and New Zealand (Boarini and d’Ercole, 2006). Leisure and social activities have been covered widely, with some exceptions in the US and Canada: items such as a holiday away from home can be found in most country measures, and to a lesser extent items such as visiting or having around family and friends.

Based on these reviews, health-related items are not included in material deprivation measures in many countries but in those that do, the focus is on postponing appointments or not undergoing regular check-ups and treatments (for example, in relation to dentists or opticians) due to inability to afford costs, as well as problems in keeping up with medical and hospital bills (Boarini and D’Ercole, 2006, Kenworthy, 2007).

In the UK, the list of items in the PSE Deprivation Index using the 2012 PSE survey includes a question on accessing dental services. Subsequent reforms to NHS dentistry in the past decades have posed challenges in terms of both access to and affordability of services, with many who qualify for free NHS dental services having to turn to private providers for routine treatments and regular appointments (Garratt and others, 2022). This suggests that there might be a good case for including access to dental services within measures of material deprivation where access and cost is an issue. As noted, the exclusion of health care services from material deprivation indicators has been traced back to Mack and Lansley’s research in the Breadline Britain series who chose to exclude these items due to the fact that they are largely publicly funded and provided and households did not need to bear their main costs (at least at the point of use).

This discussion of the different dimensions of material deprivation should also recognise differences in the items included under these broad categories. For instance, while several indices include specific durable goods (such as, a refrigerator or a washing machine), the recent revision of the EU deprivation measure led to a reduction in the number of these items. No household consumer durable goods are included in the current UK material deprivation measures. McKay and Collard (2004) note that excluding specific consumer durables makes the measure less sensitive to product life cycles. Relatedly, Ferragina and others (2013) note that the range of consumer durables that people possess is less important to assess material deprivation than many other necessities, as they may have been acquired before people fell on hard times, or they may not be in a good condition. It would therefore seem more appropriate to focus on households’ ability to sustain costs of repairs or replacement rather than on ownership of these items, as in the UK measures.

Ownership of certain items or engagement in certain activities can have multiple significance and the lists considered here do not, by and large, distinguish or make explicit the different rationales for inclusion. For instance, a telephone has a social function, besides being a durable good; a television or a holiday are respectively a means to enjoy entertainment and a source of leisure but can also represent social status and material prosperity. Similarly, a car is a durable good (and a big ticket item that requires regular expense), a means to access services and participate in activities, but it has also long been representative of social status (Johnson and others, 2010). Change occurs across all these different aspects – besides the product life cycle, some items’ social significance, status and acceptability can change, such as car ownership in face of environmental concerns, or use of second-hand clothes to reduce waste.

Car ownership is included in all the measures examined here which cover transport. Hardship and limitations experienced by households without cars depend on factors such as rurality, availability of public transport, population density and society orientation towards car-ownership, for example, in countries such as the US (Kawabata and Shen, 2007). High correlation between car ownership and income can further justify the inclusion in material deprivation measures, but this should be evaluated in specific contexts as inclusion of car ownership can also create distortions in the resulting picture of disadvantage (Johnson and others, 2010). An exception to the inclusion of car ownership among the measures examined here is the UK material deprivation measure for pensioners, which instead includes “access to car or taxi, whenever needed”. This suggests a shift towards considering access to transport and fulfilment of mobility needs as relevant to material deprivation, rather than ownership per se (and recognises that not all older people drive). Not having a car can affect access to services and employment opportunities as well as the prices paid for other items such groceries or housing. These effects, however, are mediated by context and would be more adequately assessed by also considering public transport supply and accessibility of goods and services (Johnson and others, 2010).

Considering different dimensions can help to inform the selection of necessities in a material deprivation measure. However, if people give up consumption in certain domains before others (for example, if they give up social activities first), a domain-driven approach to item identification can lead to a weaker measure (Bailey, 2020; 896). In a domain-driven approach, priority is given to ensuring that an agreed set of domains (dimensions) are represented in the final selection of items rather than using an analytical framework (testing for suitability, validity, reliability and additivity) to identify an optimum set of items irrespective of their distribution across domains.

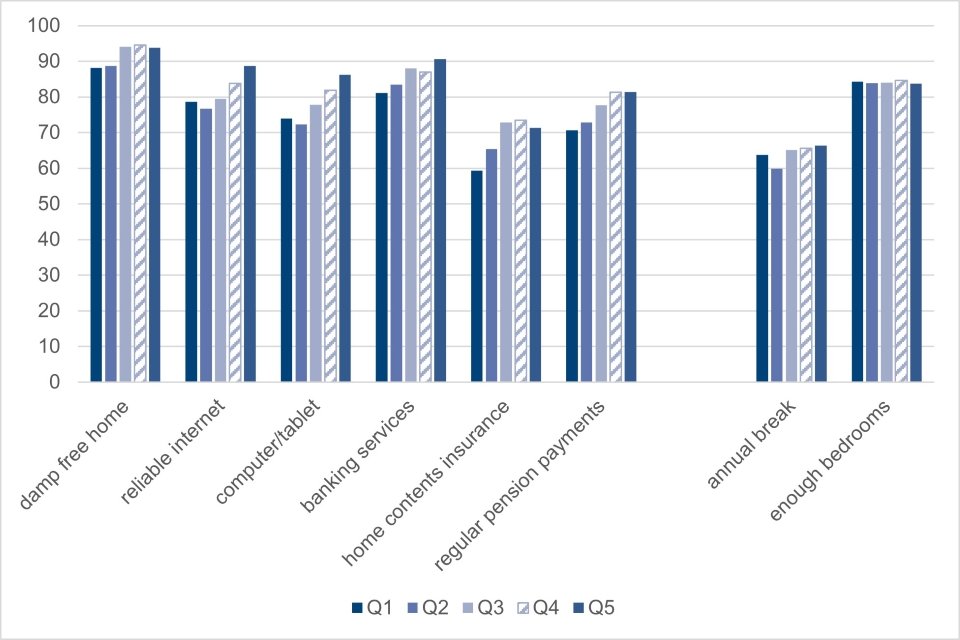

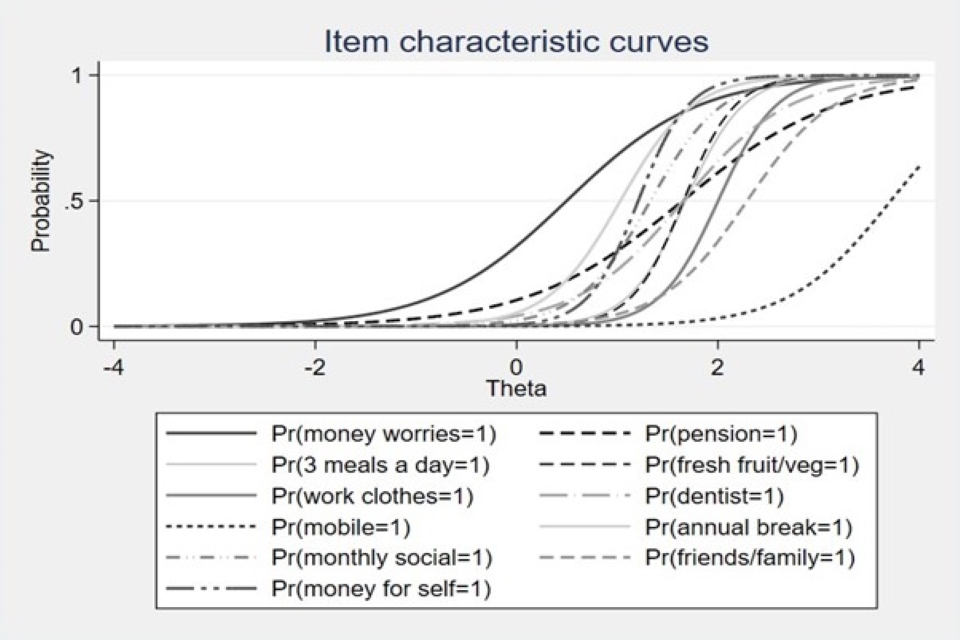

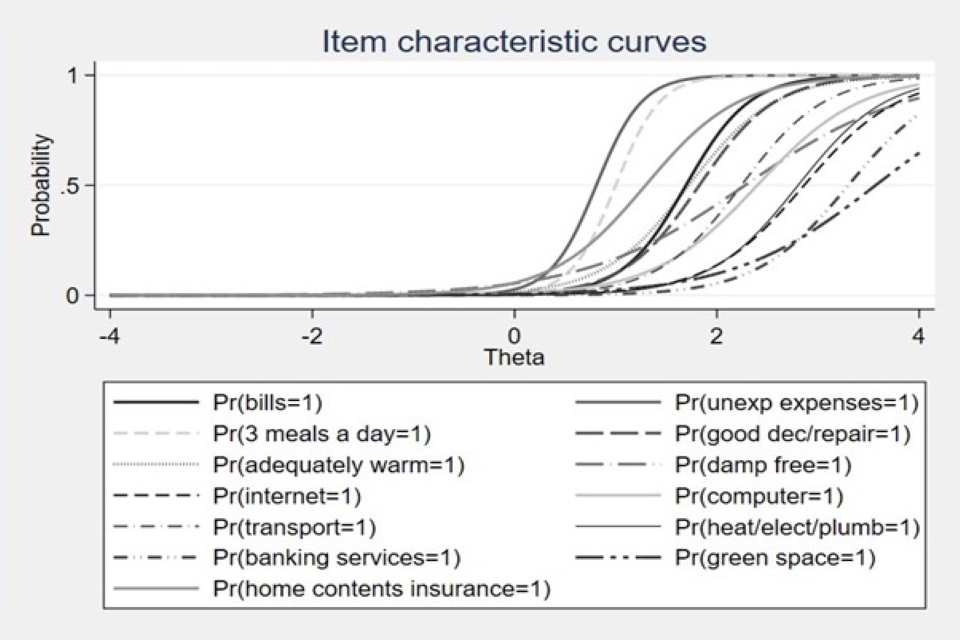

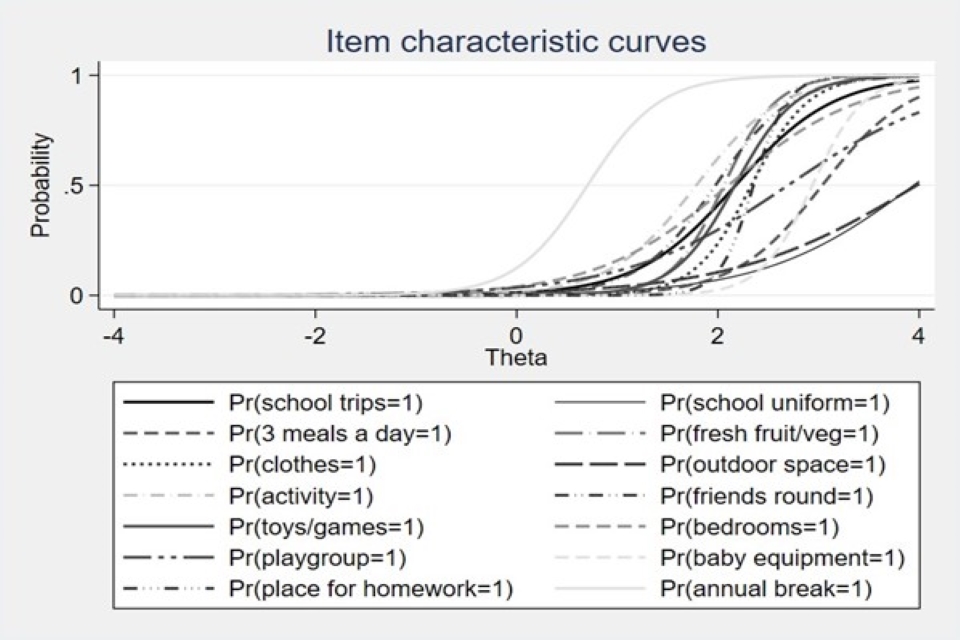

2.4. Relationship between minimum income standards and material deprivation measures