Non-compliance and enforcement of the National Minimum Wage: A report by the Low Pay Commission

Published 11 May 2021

1. Chapter 1: Introduction

This is the LPC’s fourth stand-alone report looking at non-compliance and enforcement of the National Minimum Wage (NMW). We have adapted our approach this year. As set out in our 2020 Report, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Government’s response to it – particularly the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) – prevent us from carrying out our usual analysis of pay and employment. This includes our usual treatment of underpayment of the minimum wage.

In addition, the enforcement data we would usually analyse only cover the period up to April 2020 – since when the circumstances of both workers and employers in low-paying sectors have changed radically. This report does not look in detail at lagged or flawed datasets. Instead, we try to assess the immediate challenges for minimum wage enforcement, in light of evidence received in our 2020 consultation and what we know about underpayment from the NMW’s recent, pre-pandemic history.

The reopening of the economy, however gradual, will find low-paying sectors in a very different place from before the shutdown. Higher unemployment and a slack labour market have the potential to disempower workers, creating conditions for underpayment and other forms of exploitation. It is imperative that the enforcement regime recognises and keeps up with this threat.

The second chapter of the report sets out our views on the broad challenges and changes which will affect the enforcement regime over the coming year. The third chapter considers some of the specific problems which we have raised in recent years, looking at progress in areas where we have made recommendations. This is organised under three key challenges. The first relates to the interactions between the enforcement regime and underpaid workers, on whose willingness to report underpayment the system to a large extent relies. The second relates to the enforcement body’s relationship with employers, where the Government has responsibility for facilitating compliance as well as enforcing the rules. The third centres on how HMRC prioritises a complex and wide-ranging workload.

We welcome the Government’s acceptance of nearly all the recommendations we made in our 2020 report on non-compliance and enforcement (Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 2021). This makes a large number of our recommendations which the Government has accepted and undertaken to implement in recent years.

For the most part, this report does not make new recommendations: instead, throughout Chapter 3 we review progress in some of the key areas we have focused on in recent years. In some places we expand on the original recommendation, to suggest different ways forward. This is particularly the case in matters relating to the way HMRC record data and prioritise their caseload. The proposed creation of a single enforcement body offers an opportunity to reset practices. This in turn has the potential to significantly expand our understanding of what non-compliance looks like in practice.

1.1 The outlook for 2021

This report has been prepared at a point when we were still in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, with large parts of the economy closed and significant uncertainty about the future. Nevertheless, it is clear that this crisis, and the series of shutdowns of the economy, will have had a transformational effect on the UK labour market. While it will take time to sort long-term changes from short-term phenomena, the enforcement regime must remain alert to new risks as they emerge.

1.2 A more fragile labour market

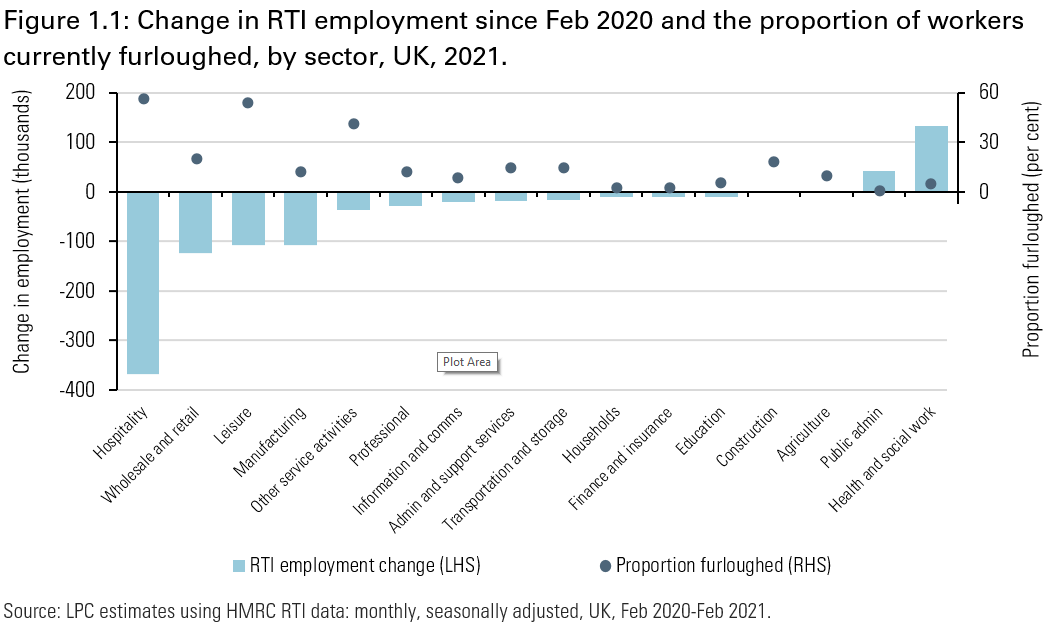

The OBR forecast unemployment to rise to 2.2 million by the end of 2021 (Office for Budget Responsibility 2021). As Figure 1.1 below shows, low-paying sectors (for example, hospitality and leisure) have been among those hit hardest by restrictions with more than half of employments currently furloughed. These are where employment may be at greatest risk, with large numbers of workers facing possible redundancy.

A weaker labour market, where low-paid workers have fewer choices, increases the likelihood of underpayment. Workers who are more concerned about their jobs will be less willing to challenge their employers and less likely to report abuses. The Government needs to be on the front foot in counteracting this risk. As ever, NMW underpayment is likely to be associated with other forms of abuse, from non-payment of holiday or sick pay to failure to observe health and safety rules. There is a need for effective and comprehensive enforcement across all these areas.

1.3 Businesses under pressure

The pandemic has seen entire sectors closed down for months at a time; others which are open have been forced to adapt to unpredictable conditions; many businesses – particularly SMEs – have taken on more debt than ever before. Many of those running businesses are doing so under an unprecedented level of stress.

Adding to this, employers participating in the CJRS have had to deal with significant changes to employment legislation throughout the year, as the scheme was rolled out, revised, removed and reinstated. This created particular difficulties for small and micro employers with only basic payroll support, but we heard as well from very large employers about the complex administrative burden involved. As workers leave furlough, the consequences of these challenges are going to become more apparent. Although we mainly heard praise for HMRC’s administration of the scheme, there will be a continued need to support employers as they return to a more stable form of payroll management.

This creates challenges for enforcement – particularly when it comes to its efforts to support businesses to comply with the minimum wage. There is a risk that employers have less bandwidth to engage with the materials and guidance that are available. HMRC also face a challenge in making sure overburdened employers continue to engage with the enforcement process in a timely way, avoiding backlogs in the system.

1.4 A single enforcement body?

Underpayment takes a variety of forms and presents risks across very diverse parts of the economy. Enforcement by its nature is a complex challenge and needs strong strategic direction. For this reason, filling the vacant post of Director of Labour Market Enforcement should be a priority for the Government, and any incoming Director will need to begin rapid consultation with key stakeholders about priorities. More than ever, the Director and their office have an essential role to play in shaping the response to the largest labour market shock in a generation.

The Government consulted in 2019 on proposals to merge several existing agencies into a single enforcement body (SEB). Legislation is expected to be brought forward in a future Employment Bill, although there is no current timetable for this. The creation of the SEB will be a significant opportunity to change and improve existing practices – although the upheaval in creating a new body brings risks as well. The challenges of NMW enforcement will remain the same regardless of which body is responsible, but better coordination and the alignment of priorities across different areas can only be a positive. We await the Government’s proposals for the SEB with interest.

1.5 Emerging case law

A number of recent and ongoing court cases may have significant implications for minimum wage rules and the enforcement regime. The recent Supreme Court judgement on Uber drivers has led to that company reclassifying the status of its drivers from self-employment to workers, with an entitlement to the minimum wage. The judgement opens the possibility of other gig economy employers making similar changes and could ultimately lead to a wide range of workers hitherto classed as self-employed being redefined as workers, with eligibility for the NMW.

Another long-anticipated Supreme Court ruling has also been issued, on sleep-in shifts in social care . In this case, the ruling does not imply a change to the way these shifts are treated; workers on sleep-in shifts will not attract the NMW. Although this means the status quo is maintained, the ruling’s implications still need careful consideration, as part of the wider question of the treatment of the care workforce and sector.

We will continue to closely monitor developments in the case law around the NMW, and to watch how enforcement bodies respond to these emerging judgements, which have the potential to greatly expand entitlements to the minimum wage.

2. Chapter 2: The shape of underpayment

2.1 Underpayment before the pandemic

Our previous report on non-compliance and enforcement looked at underpayment up to April 2019. We estimated that in April 2019, just over 440,000 workers were paid less than the NMW. This represented 21.5 per cent of workers ‘covered’ by the rates (paid at or within 5p of the minimum).

The introduction of the NLW in 2016 involved a change in the date of the annual uprating, from October to April each year. This means underpayment estimates (which are based on a survey taking place in April) before and after 2016 are not directly comparable. However, following the NLW’s introduction, statistical underpayment rose in each year until 2018 – both the actual number of workers underpaid, and the share of coverage they represent. 2019 was the first year in the NLW period when it was estimated to have fallen.

Year on year, certain groups are more likely to be underpaid. In every year to date, women were more likely to experience underpayment than men; workers in small businesses more likely to be underpaid than those in large ones; and workers who are full-time, permanent or salaried are more likely to be underpaid than their part-time or temporary counterparts (Low Pay Commission 2020). The apparent trend is for employers to be less likely to make mistakes when they pay workers a simple hourly rate, with more potential for underpayment to creep in when they move away from this model.

A low-paid worker’s chances of being underpaid also vary according to their occupation. There is a paradoxical effect, where low-paid workers in occupations not usually considered low-paying are more likely to be underpaid – probably for reasons related to those set out in the previous paragraph. Among those occupations usually considered low-paying, we have consistently observed high rates of recorded underpayment for childcare workers, as well as office workers and those in transport. The largest absolute numbers of underpaid workers are in the largest low-paying occupations: hospitality, retail and cleaning.

All of this, however, is only what is observable in official sources, and each year we hear accounts of non-compliant practices which would not show up in the data. These range from unpaid trial shifts in restaurants and bars, to widespread expectations of unpaid work in the arts, to the non-payment of care workers for travel time. Underpayment which is kept ‘off the books’ is harder to identify and harder to take action against. In Chapter 3, we go on to look at the example of textiles factories, where the enforcement body faces exactly this challenge.

Box 1: estimating underpayment

Even in normal times, it is challenging to produce a reliable estimate of underpayment. We produce estimates using two statistical sources: the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE, our preferred source), and the Labour Force Survey (LFS). Both come with a number of caveats.

-

Official data sources do not tend to capture the informal economy, where a lot of underpayment is likely to take place.

-

ASHE is a survey of employers, who are unlikely to admit to underpaying workers except by error.

-

The LFS, on the other hand, is a survey of workers. Although they may be more honest about underpayment, they are likely to be less accurate when giving information about their pay and hours, rounding figures up or down.

-

In ASHE, there are legitimate reasons a worker may appear as underpaid, which the survey does not record. For example, employers can make a deduction from wages for accommodation.

-

Underpayment varies depending on when it is recorded. ASHE takes place in April each year, just after new minimum wages come into force and underpayment is likely to be highest. A survey date earlier in the month will tend to lead to a higher estimate of underpayment, and vice versa.

All of this means the estimates we usually produce should be treated with a degree of caution; they give a sense of the potential scale of the problem, the year-to-year trends and the groups most likely to be affected.

2.2 Underpayment in 2020

In an ordinary year, we use ASHE to estimate how many workers were underpaid in April, when new minimum wage rates have just come into force. We cannot do this for 2020, because we cannot fully separate real cases of underpayment from furloughed workers who were (legitimately) paid less than their usual wage (see Box 2).

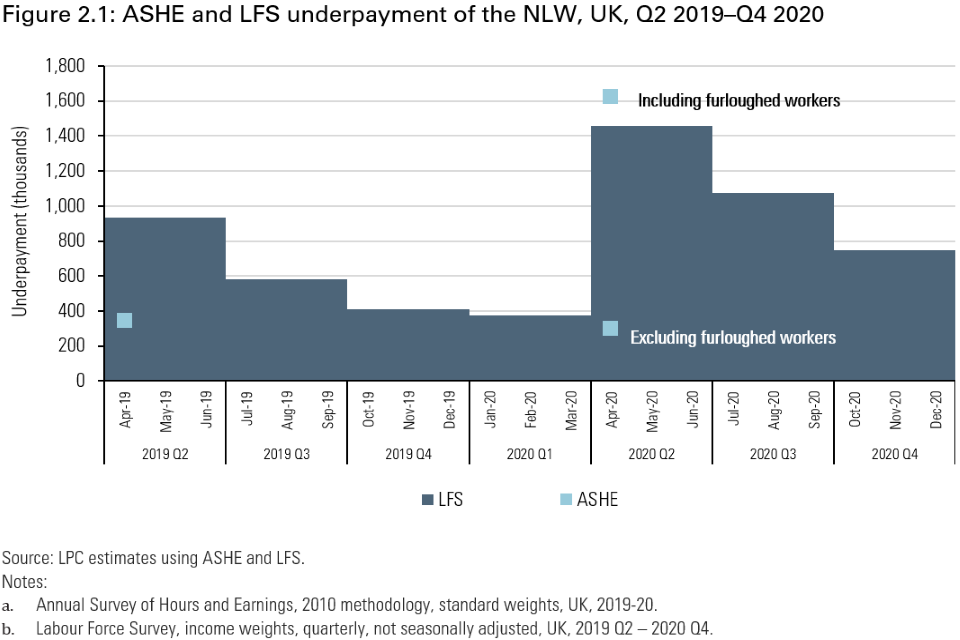

As Figure 2.1 shows, this means that if we include furloughed workers, underpayment is seen to jump in April 2020, from 345,000 in April 2019 to around 1.6 million. But we think this is an artificial effect of the furlough scheme, rather than a genuine fourfold rise. If we exclude furloughed workers, on the other hand, then estimated underpayment is lower than in previous years – but this is likely to be an under-estimate, excluding workers who would be underpaid.

The LFS also shows an alternative picture, with a large rise in underpayment in April 2020, which, although it declines through the rest of the year, remains substantially higher than in 2019. Again, though, we take this to show the effects of the furlough scheme lowering incomes, rather than a leap in underpayment.

In summary, none of the estimates for underpayment in 2020 are comparable to previous years. Until the CJRS has been phased out, this will remain difficult to produce. This does not rule out an actual increase in the risks of underpayment – as we go on to explore, the response to Covid-19 and shifts in the economy and labour market make it more important than ever to support compliance with the minimum wage and take action against non-compliance.

Box 2: Furloughing, pay and underpayment

The most recent ASHE took place in April 2020, after the introduction of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) and at a point when many businesses were closed and many workers were furloughed.

Our 2020 report explained in detail the problems this caused for measuring pay across the economy. Workers could be furloughed at 80 per cent of their usual salary. This makes it challenging to identify those workers who were underpaid and those who had instead taken a pay cut while they were furloughed.

Because of this, we have not used ASHE to estimate underpayment in 2020. Any figure we produced would not be comparable with previous years.

It is also the case that many low-paid workers who were furloughed from March 2020 did not receive the April 2020 uprating while they remained on furlough. This is because the reference period for calculating furlough payments was February 2020, before higher rates came into force. It was only once they returned to work that their wages were increased. Furloughed workers receiving the old NLW or NMW rates would not be counted as underpaid.

In last year’s consultation, we heard anecdotal accounts of furloughed workers having their payments miscalculated or underpaid. In some cases, this may represent fraud by employers. Although a serious offence, and causing significant detriment to workers, this would not count as minimum wage underpayment.

2.3 The enforcement system

HMRC activity

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) is the body responsible for enforcing the NMW, with a budget of around £26m and more than 450 enforcement officers situated around the UK. In 2019/20, HMRC completed 3,376 investigations around minimum wage underpayment, of which 1,260 resulted in arrears being repaid to workers. This meant their ‘strike rate’ of successful cases was around 40 per cent – a fall from 45 per cent the previous year.

HMRC’s activity is made up of a mixture of responding to and investigating complaints about underpayment; and proactively targeting employers where they judge there is a high risk of non-compliance. These judgements about risk are shaped by experience of past cases; observed underpayment in the data, including HMRC’s own Real Time Information tax data; local intelligence; and the strategic oversight of the Director of Labour Market Enforcement, who has responsibility for coordinating activity between different enforcement bodies.

Arrears, penalties and prosecutions

Where HMRC find that workers have been underpaid, they have the power to force employers to repay workers what they are owed in arrears. They can also impose fines on workers of twice the total arrears – although fines are reduced if paid promptly. When employers identify underpayment themselves, they can ‘self-correct’, paying arrears to workers and notifying HMRC to avoid a penalty.

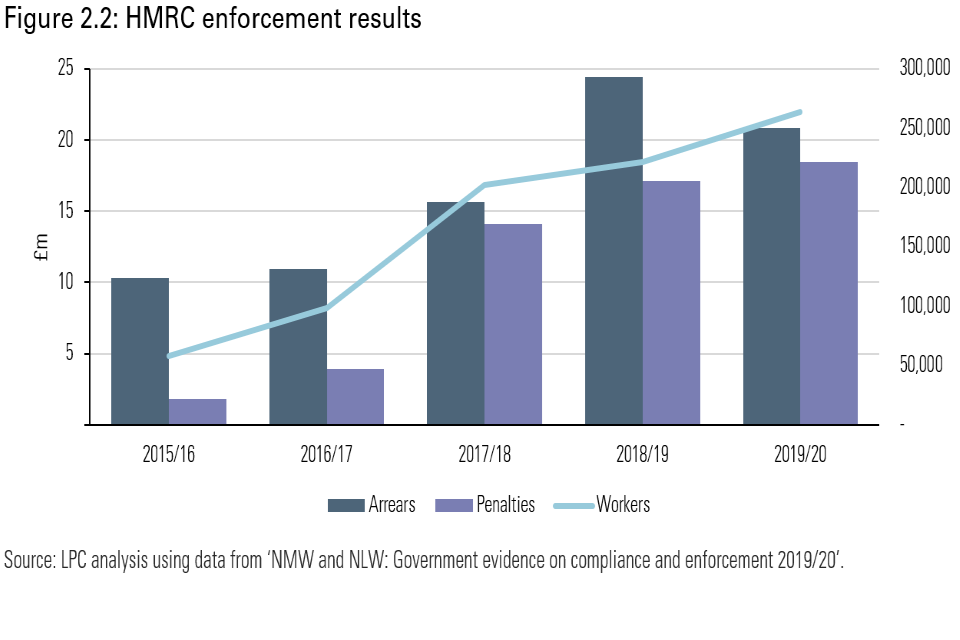

The annual totals of these arrears and penalties have risen rapidly in recent years, along with the number of underpaid workers identified (see Figure 2.2 below). In 2019/20, £20.8m of arrears were repaid to over 263,000 workers, and £18.5m of penalties were imposed. Criminal prosecutions for underpayment are very rare, with only 15 since 2007. A more common route for HMRC is to use Labour Market Enforcement Undertakings, effectively court orders requiring businesses to take action to prevent further underpayment. Twenty-one such undertakings were issued in 2019/20.

Enforcement during the pandemic

Published enforcement statistics only cover the period up to April 2020, but HMRC’s work was deeply affected by the national and local lockdowns across the UK from March onwards. HMRC told us they had opened fewer cases; and that existing cases were progressing more slowly. Many businesses were shuttered and enforcement officers constrained in their ability to visit premises and carry out investigations.

Although HMRC has responded well to maintain and resume activity as soon as possible, the pandemic will have had significant and long-lasting impacts:

-

HMRC shifted the sectoral focus of its targeted enforcement – for example, away from shut-down sectors. It is undoubtedly right to take a pragmatic approach, but it will be important to carefully assess their impact in the medium-term. As HMRC told us, this enforcement activity should be considered as postponed due to the pandemic rather than abandoned.

-

The CJRS – and flexible furloughing in particular – create a degree of complexity which is likely to increase the risk of underpayment occurring. The impact of the CJRS on workers’ hours and pay will be a recurring feature for years to come, with HMRC needing to carefully document and calculate changes in status between work, furlough and flexible furlough.

3. Chapter 3: Enforcement challenges

This chapter looks at the strategic challenges for enforcement identified in previous LPC reports. We have divided these into three areas: supporting workers and encouraging them to report underpayment; promoting and enabling compliance among employers; and prioritising how resources are deployed across a complex and varied landscape.

3.1 Challenge 1: supporting workers

Fewer workers are reporting underpayment

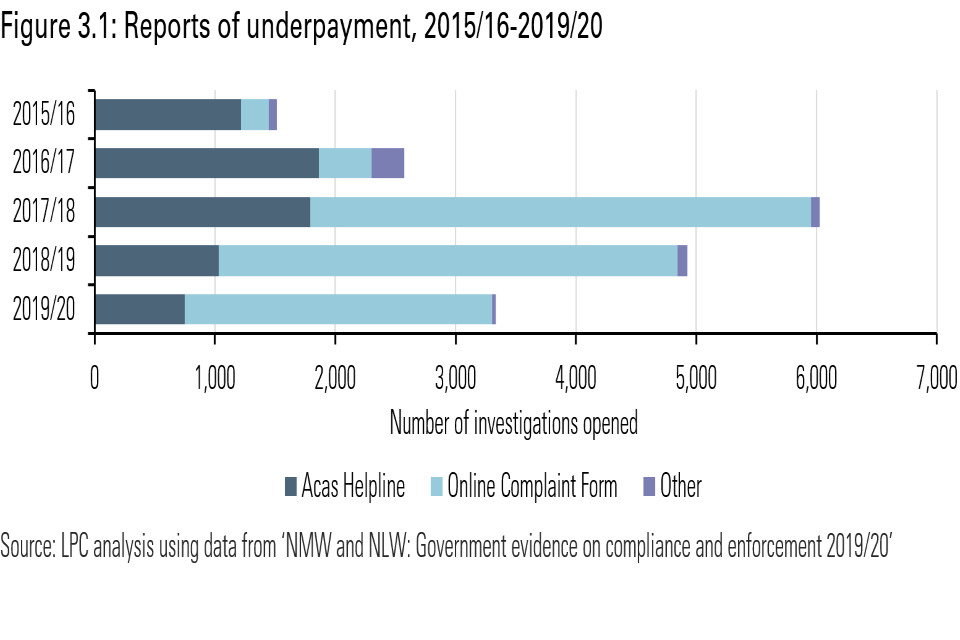

There are two main routes for a worker to raise a case of underpayment with HMRC: they can call Acas, who provide advice and raise cases with HMRC on their behalf; or can contact HMRC directly via an online form. Figure 3.1 shows the number of complaint-led investigations opened by HMRC over a period of five years. From a very low base, the number of cases opened increased considerably in 2017/18, driven by their online form – but have since fallen markedly. The number of complaints received remains small next to the estimates of the numbers of underpaid workers – which suggests either low awareness of rights, or widespread reluctance to engage in the complaints process.

Published figures only go up to April 2020. However, HMRC have told us that complaints have declined further since then. We can speculate as to the reasons for this more recent decline: many low-paid workers have been furloughed or lost jobs (complaints about the CJRS are investigated by a separate team within HMRC); others whose jobs may be under threat are likely to be less willing to raise complaints. Over the longer term, some of the decline may be a reduction in ‘misdirected’ complaints – but this is hard to judge and we have not seen any uptick in HMRC’s ‘strike rate’ of success.

Government communications

There are several necessary conditions for a worker to complain about underpayment. They need to know their rights; they need to have confidence in the complaints system; and they need to be able to work out whether they have been underpaid.

BEIS runs national communications campaigns each year around the uprating of the minimum wage. The 2020 campaign, coinciding with the first wave of Covid-19 and lockdowns, was withdrawn. The reasons for this are understandable – but it places more pressure on the 2021 campaign to get through to workers. In addition, HMRC work directly to reach specific groups of workers, with large-scale campaigns via letters, emails and text messages to make low-paid workers aware of their rights.

Building confidence in the complaints process

In the long term, the low volume of complaints represents a serious barrier to an effective enforcement system. This is why we have recommended the Government take action to build confidence in the process. In particular:

-

Workers should be aware of the confidentiality of the process and their ability to protect their anonymity.

-

The system needs to be accessible to all workers – including those for whom English is not a first language.

-

The Government should consider publicising successful cases where workers have complained and been awarded arrears.

-

Close working with trade unions will be an important tool in reinforcing routes for complaints and building an understanding among workers of how the enforcement system works. An effective and widely-trusted third-party complaints system is central to this.

The effects of Covid-19 on the labour market will only tend to weaken the incentives for workers to report underpayment. It is important for the Government to recognise this early and take action to prevent such complaints drying up.

Access to pay information

Even when workers are ready and willing to complain about their employer, they may face challenges in documenting their underpayment. The law has changed in recent years to force employers to provide clear payslips, including the number of hours worked, to all workers. This is a major step forwards, but we continue to hear evidence that changes have not been put into practice as they should – above all in the social care sector.

Various practices in social care – including the treatment of travel time and the time allowed for homecare appointments – make it difficult for workers to fully document their hours and prove underpayment. A survey by Unison in July 2019 found that almost three-quarters of homecare workers did not feel they had enough information in their payslips to verify that they were paid the NMW, and almost half of respondents did not believe they were paid for all their working time.

The recent changes in legislation are positive – but they need to be adequately promoted and, ultimately, enforced if they are to make a difference for underpaid workers.

Access to employment tribunals

Employment tribunals are a key element of the enforcement system, but the past year has seen an already strained system come under even greater pressure. Average waiting times for a tribunal hearing are over 12 months. A recent Citizens Advice report (Citizens Advice 2020) has shown how the pandemic has led to increasing demand for tribunals at the same time their activity is restricted by Covid-19. Work by the Resolution Foundation (Cominetti and Judge 2019) has shown how the workers most vulnerable to underpayment and other violations are less likely to make an application to a tribunal. The tribunal system slowing down represents another factor with the potential to undermine confidence in the enforcement regime as a whole.

Box 3: Status of previous LPC recommendations on worker support

Continue to invest strongly in communications to workers. (2017)

-

The Government has continued to invest, and doing so is more important than ever – particularly given upheaval in the labour market and the potential for confusion as the furlough scheme is withdrawn.

-

The loss of the April 2020 comms campaign is regrettable but understandable – this year’s uprating represents an important opportunity to reach workers, that must be sustained by intelligent, targeted work by HMRC’s Promote team.

Consider how to build confidence in the complaints process, and to work with trade unions to understand the current barriers to reporting. (2019)

-

Although this recommendation has been accepted, we would like to see the Government do more to build an understanding of the barriers to workers complaining. Trade unions and other interested groups also need to play a part in this. Citizens advice bureaux are another likely source of intelligence.

-

Building a better picture of what motivates workers to report underpayment, and what can keep them from doing so, is a necessary first step.

Review the regulations on records to be kept by an employer, to set out the minimum requirements needed to keep sufficient records. (2020)

- We are pleased that the Government have accepted this recommendation. The extension of the length of time for which employers need to keep records is a positive step. In the meantime, there is a case for promoting the rules in place more extensively, in sectors where this is known to be a risk.

3.2 Challenge 2: supporting employers

Compliance versus enforcement

Businesses need support to understand and follow the rules, and the Government has a responsibility to ensure information on the NMW is clear, accessible and widely understood – in effect, to support compliance. The principle of the NMW is simple, but its application via payroll systems can be challenging for employers, particularly small businesses without dedicated HR support.

This becomes all the more important at a time when many businesses in low-paying sectors will be under strain from the effects of Covid-19 measures. Responsibility for this is divided between two departments: BEIS are responsible for NMW legislation and the guidance which sits around it, while HMRC’s operate their own workstream, ‘Promote’, dedicated to mitigating the risk of underpayment by making sure businesses and workers know and understand the rules.

What guidance is available to employers?

We hear evidence each year from employers about the complexity of minimum wage rules; many feel there is too much scope for inadvertent breaches, and that HMRC’s approach to enforcement does not recognise this. The main source of guidance for employers is Calculating the minimum wage, a collection of pages which set out the rules alongside illustrative examples. This guidance has recently been comprehensively refreshed and updated, with a new stock of worked examples. We will be looking for evidence in our consultation this year over whether the refreshed pages meet employers’ expectations.

The guidance on the minimum wage available to employers is generic; it is intended to be accessible to employers of different sizes in different sectors. This is a frequent cause of discontent among some of the groups we speak to, who ask for sector-specific guidance. This is needed both to address in detail specific issues which do not occur elsewhere; or to counter widespread non-compliant practices. An example of this latter case is the creative industries, where each year we hear evidence of the widespread expectation among employers that the minimum wage does not apply, and that workers will work either for free or for a pittance. We continue to support requests for tailored, sector-specific guidance.

What issues catch employers out?

Employers are often caught out by deductions from workers’ wages. The only ‘allowable’ deduction which can reduce a workers’ pay below the minimum wage is for accommodation (and the maximum level for this is set by the Accommodation Offset). Many other deductions, even when agreed with the worker and providing them a benefit, will be illegal if they reduce pay below the NMW.

A related area which causes difficulty is around uniforms. Businesses cannot charge workers for uniforms if this reduces their pay below the NMW – although they can set reasonable limits on what workers may spend to comply with a dress code.

Calculating working time is the other large area that can trip employers up, particularly where workers are paid a salary rather than an hourly rate. BEIS revised legislation last year to simplify rules around pay periods, but difficulties remain.

Box 4: Status of previous LPC recommendations on employer engagement

Invest time in getting the guidance to employers right, as this will simplify the task of enforcement in the longer term. (2019)

- We accept that the Government have worked to review and refresh the available guidance. We will be seeking evidence this year over whether there is still a gap between the information available and employers’ expectations.

Monitor the effects of the increase in the threshold for naming employers found to have underpaid workers. (2020)

-

We are pleased that naming rounds have resumed. The higher threshold will mean fewer employers are named in each round. This may help in ‘streamlining’ the process and ensuring more regular rounds can take place.

-

We hope to see regular announcements building momentum and attention from now on. We also want to see the Government continuing to build its comms approach to naming rounds, so they support compliance as effectively as possible. We will continue to look for evidence on the impacts of naming rounds and their effectiveness as a deterrent measure.

Develop a similar approach to the Section 89 notices used by the Pensions Regulator for minimum wage compliance. (2017)

- We are pleased that the Government has adopted a more educational approach in the recent naming round, following the example of the Pensions Regulator. We would like to see this refined in future rounds, with more detailed and specific examples.

3.3 Challenge 3: prioritising enforcement activity

HMRC has limited resources

The teams responsible for enforcement in HMRC have a budget of over £27m, which funds around 450 enforcement staff, organised into just over 30 separate teams across the UK. The level of funding and number of staff increased sharply after the NLW was introduced in 2016 – but has now been stable for several years.

HMRC faces a complex set of challenges in directing its resources. The first call on its resource is always to respond to all complaints received, and in this sense, enforcement is complaint-driven. After this, HMRC undertake targeted activity in ‘high-risk’ areas; and they promote the NMW via targeted communications to employers and workers.

In previous reports, we have noted the difficulty of scrutinising how HMRC prioritises activity, and the risk of being led astray by headline numbers. The majority of arrears each year are generated by a small fraction of the cases HMRC closes.

How does HMRC identify its priorities?

There are a multitude of ways to divide up HMRC’s caseload; many are helpfully set out in annual statistics published by BEIS (Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 2021). There are reactive, complaint-led cases versus proactive, targeted ones; large cases versus small cases (where size is measured by total arrears); cases organised by sector and by region.

Despite the wealth of data, it is still hard to scratch below the surface and understand how HMRC’s makes decisions about how to deploy its officers. In particular, what are the relative resource requirements of different cases; and how are strategic decisions made about what kinds of (targeted) cases to prioritise.

This is relevant because one of the most frequent comments we hear on enforcement activity is that it focuses too much on ‘low-hanging fruit’ and not enough on serious non-compliance. We do not believe this is the case; but greater transparency from HMRC would help in rebutting this criticism.

3.4 Box 5: Status of previous LPC recommendations on prioritisation

Evaluate what data are recorded in non-compliance investigations, and consider how this can be used to develop measures of cost-effectiveness. (2020)

The Government has accepted our recommendation, but we wait to see what work will be taken forward as part of this. The introduction of a Single Enforcement Body will offer an opportunity to reset the way HMRC records case data and to develop measures for comparing cases with very different profiles. There are several ways of recording information which could help expand our understanding of the nature of underpayment.

-

Formal or informal? At the moment, we do not know whether the underpaid workers identified by HMRC are paid cash-in-hand, or whether they are present on PAYE systems. Among other things, knowing this would allow us to better understand whether the recorded underpayment in ASHE represents ‘typical’ non-compliance or not. For example, if the bulk of HMRC’s cases (or more serious cases) find underpaid workers are actually paid via informal arrangements, then this tells us that the statistical underpayment we observe and the actual underpayment HMRC finds are actually different populations. Alternatively, if a significant proportion of workers identified by HMRC are actually on PAYE, then we may be confident that ASHE is accurately measuring the formalised part of the problem.

-

Which groups? Which employers? Demographic data from HMRC cases is extremely limited. Knowing more about which workers complain and are found to be underpaid would help target proactive enforcement. As set out earlier in this report, ASHE underpayment data tells us certain groups are more likely to be underpaid than others (for example, women, micro business workers, or salaried workers). Knowing about the characteristics of HMRC’s caseload (for example, age, gender or ethnicity) would help tell us if ASHE is a good measure; and would tell us which groups are being reached by enforcement and which not. For example, although we know that women are more likely to be underpaid, in the past we have found they are less likely to make a complaint. A proactive enforcement strategy could balance this out – but without the relevant data, it is hard to tell if this is happening.

-

What type of work? Knowing the status of workers in enforcement cases (for example, whether they were apprentices, temporary workers, agency staff or on zero hours contracts) would help us understand which workers HMRC are getting to and which they are not. Despite the ongoing issues with apprentice non-compliance we have heard that HMRC have difficulty identifying apprentices amongst their caseload.

3.5 Serious non-compliance

News coverage in 2020 of the Leicester textile industry gave new prominence to the existence of serious exploitation in the UK labour market. The issues brought to light in Leicester are not new (they have been extensively documented by journalists and academics, and highlighted by the LPC); underpayment of the minimum wage is not the only abuse involved; and they are unlikely to be exclusive to Leicester. But the city’s textile industry – and the work ongoing there in response to last year’s coverage – offer a case study of persistent and deliberate non-compliance with labour market protections. They also demonstrate some of the dilemmas HMRC faces in prioritising its resources.

Why has underpayment persisted for so long in Leicester?

Abuses in textile factories have been extensively documented by journalists and others. The Environmental Audit Committee have highlighted the problem. Academics from Leicester University have published work on exploitative practices in local manufacturing and their relationship with the fashion industry’s wider supply chains. Last year’s report from Labour Behind the Label (Labour Behind the Label 2020) was the latest in a long line of such exposés. A report commissioned by Boohoo and carried out by Alison Levitt QC included its own account of a visit to factories in Leicester where health and safety issues were immediately apparent.

Despite this, since 2017, only five textiles employers have been named by BEIS as underpaying workers, and only one of those in Leicester. There has been enforcement activity in Leicester; stakeholders familiar with the local industry have told us they have reported concerns repeatedly, but nevertheless problems have apparently persisted. There are several reasons advanced for this:

Workers are very reluctant to raise complaints about underpayment. This may have its roots in insecurity, fear or a degree of collusion with employers. In any case, placing the burden on individual workers to raise and pursue complaints creates considerable pressure; many underpaid workers are likely to be reluctant if they feel their employment is precarious, they do not have English as a first language or if they are fearful about their immigration status. Localised campaigns to raise awareness of rights have been piloted by third-sector groups, targeting the communities most vulnerable to exploitation. Any realistic solution must look further at initiatives such as this.

In some cases underpayment is ‘sophisticated’; employers are willing and able to concoct records that do not reflect the reality of workers’ hours and pay rates and present these in audits and inspections. If investigators have no alternative source of evidence other than the records they are presented with because of workers’ reticence to say otherwise, this creates a real barrier for enforcement bodies.

The structure of the textile industry drives a ‘race to the bottom’ on price and, ultimately, pay. In Leicester, there are hundreds of small workshops competing against one another for small-volume orders from buyers with high market power. Frequently, the prices offered can only be achieved by squeezing labour costs.

What is needed to make a difference in Leicester?

The groups the LPC has spoken to over the years have suggested a number of ways the enforcement regime could better respond to the problems highlighted in Leicester – and other areas facing similar challenges.

Community engagement. Workers’ reluctance to complain is likely to have several causes: fear of their employer; a lack of confidence in the authorities; ignorance of their rights or the routes for raising a complaint. The enforcement bodies need to understand these barriers and take action to address them; at each stage, working closely with groups in the local community will be essential.

Changes within the industry. Studies of the textile industry in Leicester have shown how hundreds of small workshops compete against one another for small-volume orders from buyers with high market power. Purchasing practices drive down prices to levels which can only be achieved by squeezing labour costs. Many groups involved agree that beyond ‘bottom-up’ enforcement measures, change needs to be ‘top-down’ as well, with companies taking responsibility for conditions in their supply chains. We note that the 2018/19 strategy by the Director of Labour Market Enforcement recommended establishing a model of joint responsibility for supply chains.

A sustained effort. There have been various enforcement initiatives in the past to address abuses in Leicester, but none have achieved lasting change. It will take sustained attention from the authorities to have a hope of changing deeply ingrained practices. Where non-compliance is sophisticated, there is a limit to what enforcement bodies can achieve with existing powers and investigatory techniques.

What happens next?

A multi-agency taskforce, involving HMRC along with other bodies, is currently active in Leicester, with work expected to be ongoing until the end of 2021. At this point, HMRC have told us, they expect to be able to make a judgement on the scale and nature of the problem and the need for further resource. We await HMRC’s judgements; their success in finding and addressing the issues in Leicester is an important test of how the enforcement system deals with serious non-compliance across the UK.