Evaluating CDC’s Financial Institutions Portfolio

Published 4 March 2021

Foreword

I am pleased to introduce the first independent portfolio-level evaluation published as part of the FCDO-CDC Evaluation and Learning Programme. This programme is a focused collaborative effort between FCDO and CDC to strengthen the evidence base and deepen our understanding of CDC’s impact through a series of in-depth sector-level evaluations.

Longer-term evaluations of CDC’s impact are critical to help FCDO and CDC better understand how, and in what contexts, CDC’s investments deliver tangible, sustainable development impact on people, businesses, sectors and overall economies. This information is crucial to help CDC target investments and track results in those businesses and sectors where it can have the most impact and can be used to inform both portfolio management and investment decisions.

This report is the first portfolio-wide analysis of CDC’s investments in financial institutions and gives new insights into the structure and distribution of CDC’s portfolio in this sector. Drawing from an expansive internal and external data set, it has been structured to facilitate learning across CDC and draws out lessons across a number of themes aimed to inform the development of CDC’s 2022-2026 strategy, to help CDC better manage development impact within its existing investments and improve the systems it has in place for tracking the impact of its portfolio.

While it is encouraging to note that the majority of investments are on track to deliver their intended impact, the evaluation also highlights areas where CDC could strengthen its approach to assessing development impact and where further and deeper analysis is required to better understand the impact of CDC’s portfolio. It will be followed up with in-depth studies looking at CDC’s work to support MSMEs and trade finance.

I wish to thank the independent evaluators at Genesis Analytics and IPE Global for their work so far, and to my colleagues who sit alongside me on the FCDO-CDC Evaluation and Learning Steering Group who have provided valuable guidance on the direction of this work.

Rachel Glennerster

FCDO Chief Economist & Chair of FCDO-CDC Evaluation and Learning Steering

Executive summary

Introduction and scope

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) contracted Genesis Analytics and IPE Global to design and implement an evaluation of CDC Group’s (CDC) investments in financial institutions (FI). The purpose of this evaluation is to better understand the development outcomes and impacts associated with CDC’s investments in the financial sector. The overall contract consists of 3 components, namely an evidence review, an FI portfolio-wide evaluation, and a series of in-depth studies that will be combined into a final report.

This report jointly presents the findings of the evidence review and the portfolio-wide evaluation. The objectives of this report are: to provide insights on the existence, quality and quantity of literature that supports CDC’s FI impact framework and the derived evaluation questions; to provide insights into the overall size, distribution and features of the portfolio; to assess the extent to which CDC’s direct and indirect FI investments in Africa and South Asia are on track or have achieved their respective development impact (DI) thesis; to assess the geographic footprint of CDC’s investments relative to CDC’s DI Grid, which prioritises harder countries within Africa and South Asia for investment; and, to identify key themes across CDC’s FI portfolio, to assemble lessons that aim to inform a series of in-depth studies and CDC’s future FI sector strategy.

This report is predominantly informed by secondary research and some primary research through interviews with CDC’s investment, development impact teams and third-party peer reviewers. Therefore, this report provides a high-level view of CDC’s impact and aims to identify themes for further investigation that are structured to support CDC with learning and understanding its portfolio.

The portfolio-wide evaluation covers all direct equity, direct debt, 10 financial institution-focused (FIF) funds,4 debt funds, 7 master risk participation agreements (MRPAs) and 53 generalist funds.[footnote 1] The evaluation is informed by a combination of secondary data, i.e. publicly available data, CDC’s internal monitoring data (which has been shared under confidentiality where permitted), and primary data, i.e. interviews with CDC’s deal and development impact teams, to provide a descriptive analysis aimed at identifying trends, lessons and areas for further assessment.

In order to ensure commercial confidentiality, this report has been predominantly written using public information. Any data that is confidential, and has been used, is aggregated to a point where no underlying investment can be identified.

The evidence review provides a unique perspective on the literature tailored to substantiate and augment CDC’s impact vision for its FI portfolio. The evidence review has been conducted in line with FCDO’s best practice methods for synthesising research. This is a systematic method designed to gather high- quality evidence that answers 17 specific evaluative questions. A total of 441 studies were identified and reviewed. A total of 271 studies (61%) were of sufficient quality to be included in the coding process.

The portfolio evaluation utilises a logical methodology for measuring performance. This involves identifying key indicators that measure the achievement of an investment’s development impact thesis. The evaluation then assesses to what extent these indicators have been met and concludes on an investment’s performance. In this evaluation, over 500 documents and over 5,000 variables[footnote 2] were analysed.

Portfolio description

As at December 2019, CDC’s current (excluding the investment values of exits and write-offs) FI portfolio stood at approximately USD 1.67 billion U.S. dollars (USD) – at original cost - across 160 unique investments (which include generalist fund investments). The current portfolio (including the investment values of exits and write-offs) stood at USD 1.86 billion[footnote 3] across 180 unique investments as at 2019.

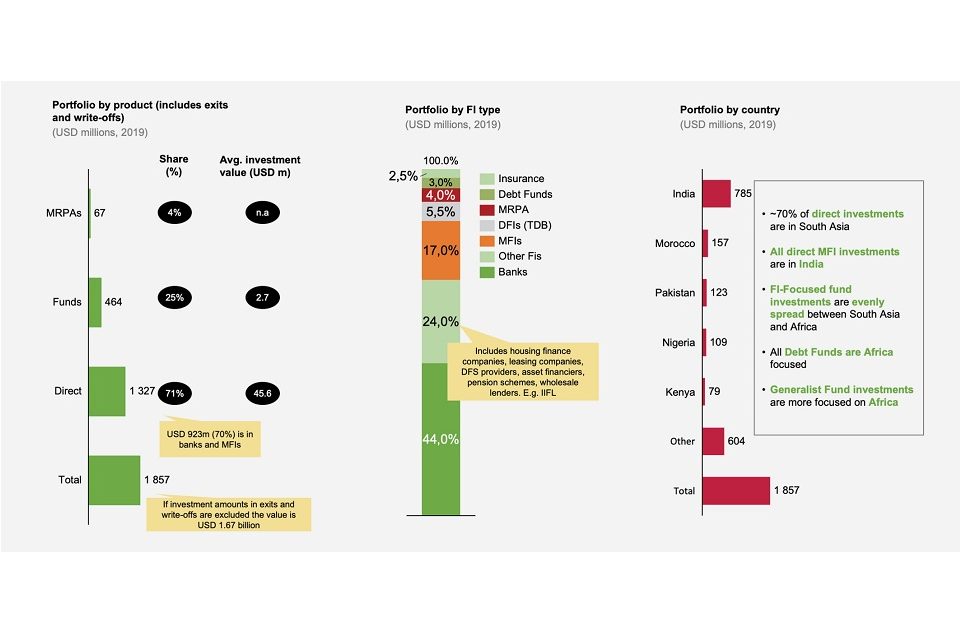

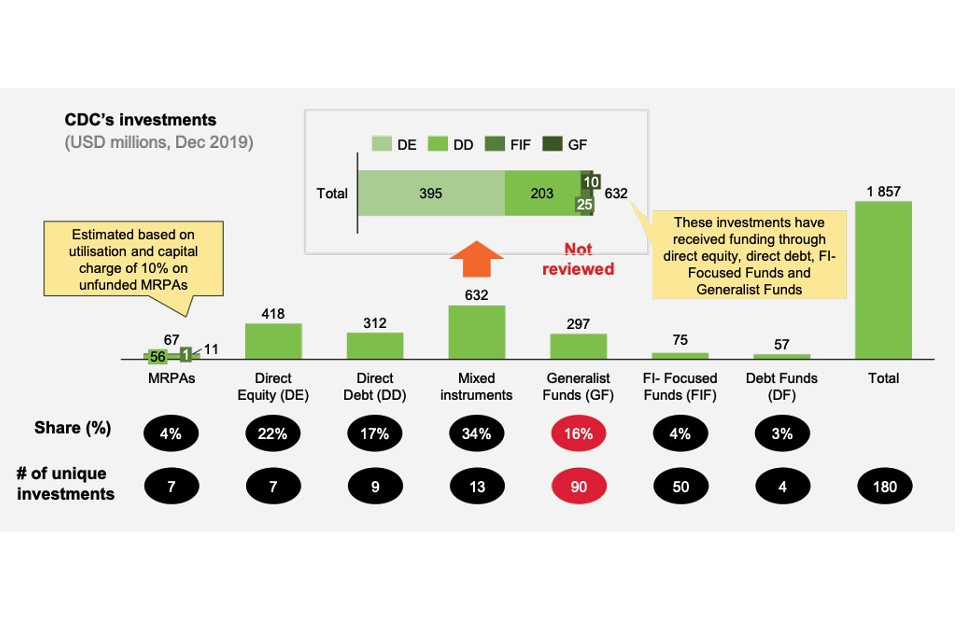

Figure 1: Portfolio description

Approximately 71% of the portfolio is invested directly and the remaining is through funds and risk-sharing agreements. About 44% of the portfolio is invested in banks, 24% in other financial institutions and 17% is in microfinance institutions (MFIs). From a regional perspective, a large portion of the portfolio is invested in India, Morocco, Pakistan, Nigeria and Kenya.

Overall portfolio DI summary

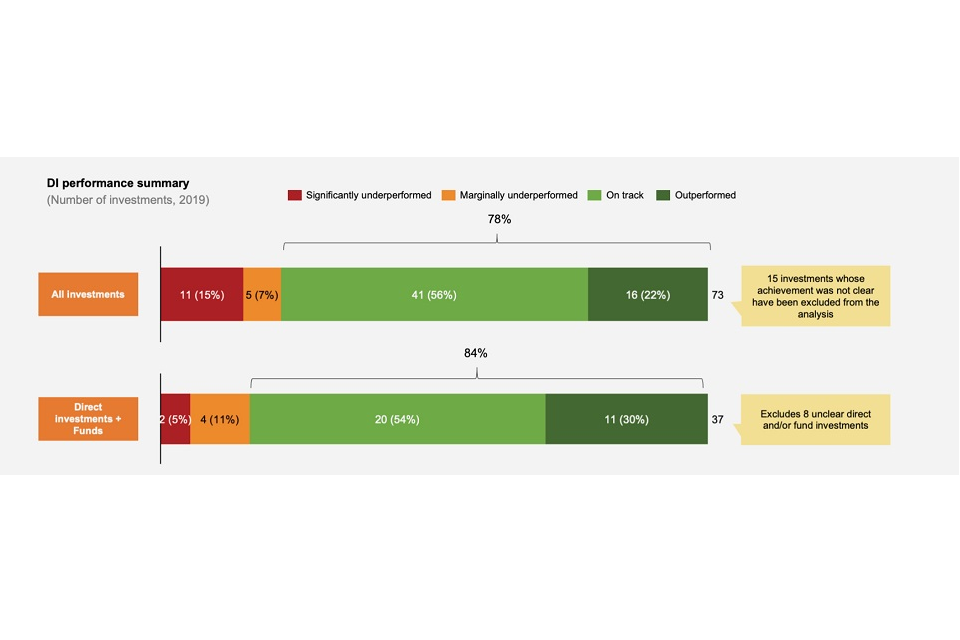

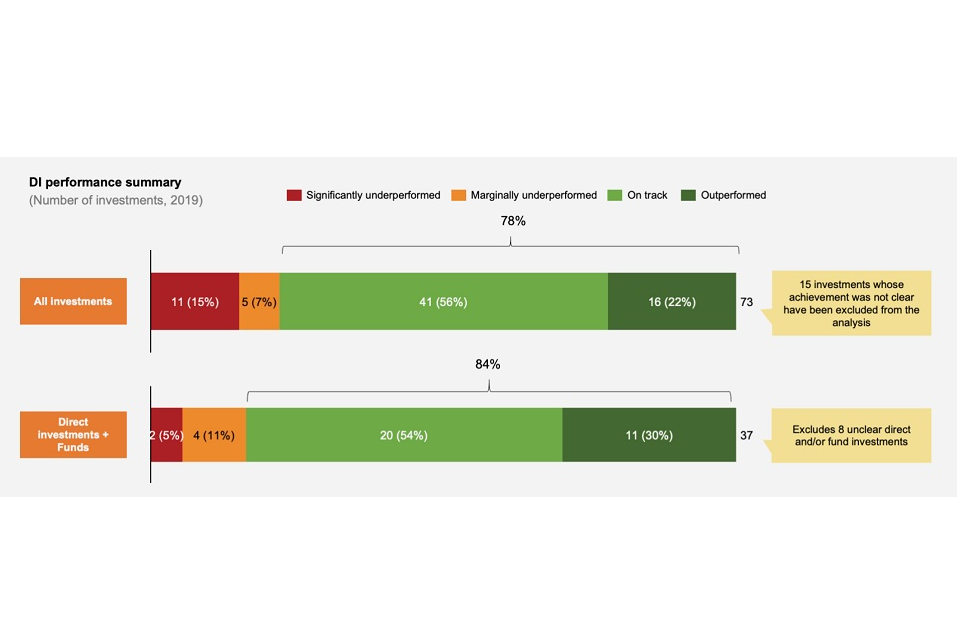

Figure 2: DI performance summary

Note: All investments - this treats every investment on a standalone basis. Direct investments + funds - this treats fund investments as an average of the underlying investments it holds. This explains the difference between 84% and 78%.

From a DI perspective, 78% of the FI portfolio is either on track or has outperformed their DI thesis. Out of the portfolio, 15 investments have an unclear impact due to reasons such as too short an investment horizon (investment entered and exited in the same year) or the investment has been made more recently (i.e. in 2018 and 2019 where full data is not available).[footnote 4]

While the majority (78%) of the overall portfolio is on track or has outperformed with respect to the DI thesis, it should be noted that this high performance is partly driven by a lower hurdle prior to 2017 to measuring DI[footnote 5] i.e. some investments have relatively easier DI thesis to attain. To counter this, section 5 undertakes a thematic diagnostic of the performance of investments based on a broader number of impact parameters that are of relevance to investments in the FI sector. This thematic analysis allows a deeper understanding of the impacts of the portfolio and identifies strengths, weaknesses and areas for improvement.

Overall, MFIs and microfinance banks (MFBs – which are deposit-taking MFIs) in South Asia have done particularly well against their DI thesis. Most of the underperforming investments are in Africa and this applies consistently across investments in both commercial banks and MFIs. Underperformance has been primarily driven by operational, macroeconomic, business integrity[footnote 6] and regulatory issues (presented in the order of the largest contributing factor).

Of the 10 evaluated FIF funds, 6 are on track to achieving their DI thesis 4 of these are India-focused funds), 3 are marginally underperforming against their DI thesis (2 of which are Africa-focused funds) and it is too early to assess adequately one fund’s impact, as CDC’s investments in the fund were made post 2018. Of the 24 direct investments, 18 have outperformed or are on track to achieving their investment theses, 3 are underperforming and the remaining 3 were only added to the portfolio post 2018. Of the 7 master risk participation agreement (MRPA) investments, one investment outperformed, 3 investments are on track and the impact of the remaining 3 could not be determined. Three of the 4 debt funds outperformed or are on track with respect to their investment theses and the impact of the remaining one is unclear.

When collectively looking at direct investments, FIF funds,[footnote 7] MRPAs and debt funds, 84% of CDC’s investments are either on track or outperforming. The remaining 16% are underperforming (8 unclear investments were excluded from the calculation). This percentage differs from the 78% above as it calculates an average performance of a fund based on its underlying investments as opposed to treating each investment within a fund on a standalone basis.

Based on a review of key sector, DI and CDC’s general corporate indicators, several findings emerge.[footnote 8]

- loans and advances of the overall portfolio have grown, although it is not clear if these loans are reaching the targeted segments (e.g. small and medium enterprises (SMEs), households, women, etc.)

- FIF funds account for the largest share of loans in terms of the number of loans driven by relatively small investments in large banks

- as expected, average loan sizes are the lowest for MFIs given that they serve low-income retail customers

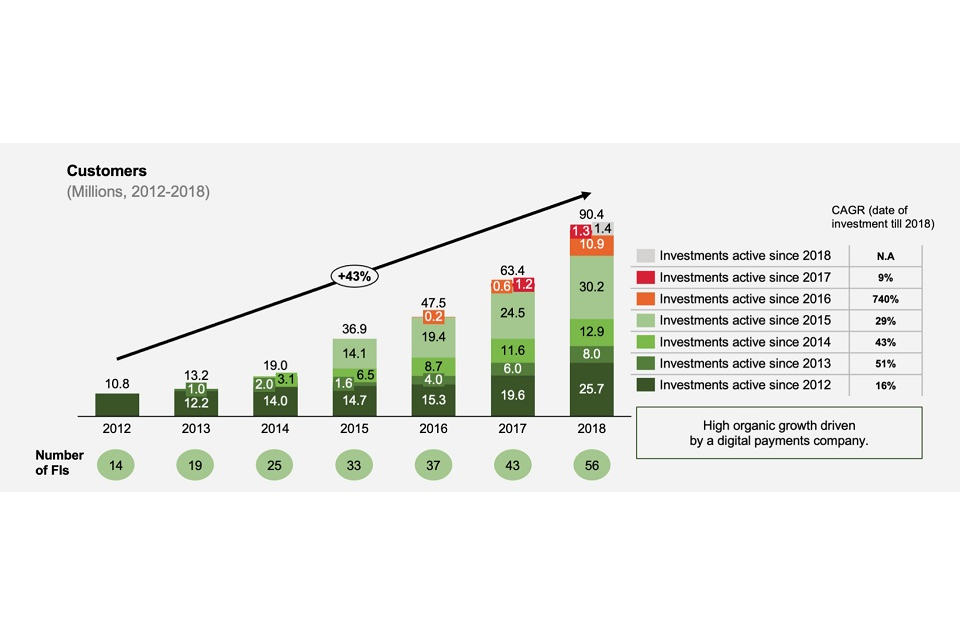

- the portfolio has seen strong growth in customers – measured as both depositors and borrowers – and the majority of the customers are reached by banks with large retail customer bases in South Asia. It is worth noting that digital financial service (DFS) providers account for only a small portion of the portfolio in value, but due to the nature of their business reach a considerable number of customers

-

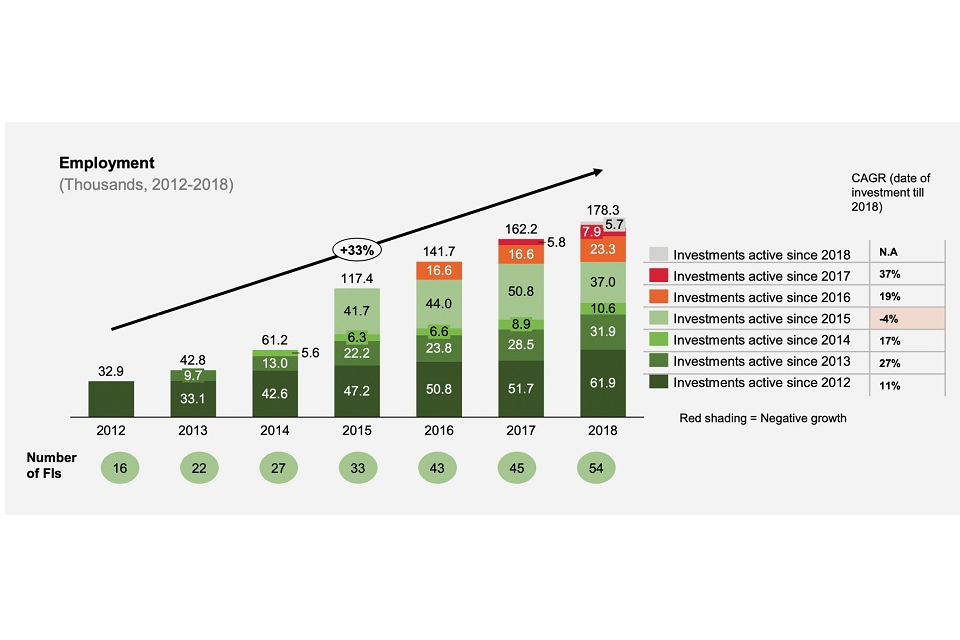

altogether, MFIs and MFBs accounted for 62% of direct employment generated in 2018; possibly driven by their extensive branch and field officer networks. The 7 small finance banks (SFBs)[footnote 9] in India have done well in this regard.

-

South Asian investments have generally performed best in most of the metrics, driven by the relatively more stable macroeconomic environment compared to Africa, benefits arising from being able to reap economies of scale,[footnote 10] a more robust regulatory environment and better operational performance.

- overall, it was not possible to draw any firm correlations between profitability and DI and further analysis would be required to understand this relationship.

It should be noted that the above results look at the performance of the portfolio as a whole, rather than attributing performance to CDC. Currently within CDC there are efforts to begin applying an attribution approach whereby CDC’s impact can be ring-fenced from the total portfolio impact. However, these methods are yet to be developed further for them to be applied. Attribution is an important approach to measuring impact as it allows one to strip out CDC’s role clearly. Further applications and enhancement of impact measurement methodologies within CDC would support the accurate measurement of impact going forward and should be actively pursued by CDC.

Summary of the evidence review process

The evidence review uses FCDO’s best practice method on synthesising research. This method is designed to gather high-quality evidence that answers specific evaluative questions. Of the 441 studies identified and reviewed, a total of 271 (61%) were of sufficient quality to be included in the coding. The review of the evidence confirms many of the linkages within CDC’s FI impact framework. However, it also highlights several areas where the evidence base is weak, and further analysis is required in order to support the assumptions underlying CDC’s FI impact framework. For example, there is little evidence of specific FI types (e.g. commercial banks) contributing to the high-quality impact on firms and households based on FCDO’s methodology.

The key aspects of the evidence review method are explained below:

- framing of the evidence review: The evidence review consists of a review of formal evidence to validate the logic of the CDC FI impact framework across 17 key questions

- dimensions by which the evidence is assessed: The size[footnote 11] and quality[footnote 12] of the studies are the 2 dimensions by which the strength of evidence per research question is assessed. A key goal of the evidence review is to provide guidance on the plausibility of the causal relationship envisaged in the CDC FI impact framework. An important aspect here is whether the direction of evidence supports the assertion made in the evaluation questions

- the synthesis of evidence: The dimensions of evidence are mapped against the CDC FI impact framework. High-level aggregate findings from the evidence are overlaid with the findings from the portfolio evaluation. Thus, the perspectives on the evidence presented in this report relate to the existing body of available evidence from both the evidence review and the outcomes of the evaluation of CDC’s portfolio

- limitations of the evidence review: A lack of evidence does not imply that no impact occurs, but simply that this impact has not been documented in formal research that was found and reviewed through this process.

Portfolio evaluation based on themes and the lessons learnt

The portfolio evaluation is based on 7 selected themes that have been derived from CDC’s FI strategy and an in-depth analysis of individual investments. Based on this thematic analysis, a number of lessons have been noted. Within each theme, where relevant, high-level findings of the evidence review are presented. These are discussed in detail in the main body of this report. The portfolio evaluation is guided by the CDC FI impact framework and aims to assess impact against the framework to the extent possible. Given the overall data limitations, it was not possible to assess primary outcomes, secondary outcomes or ultimate impact, although in some cases this has been inferred. A final sub-section indicates the evidence available for the outcomes and ultimate impact portion of the CDC FI impact framework.

Theme 1: Geography

This theme explores whether CDC’s investments have reached the intended countries and Indian states as stipulated by their DI theses and from the perspective of the DI grid.

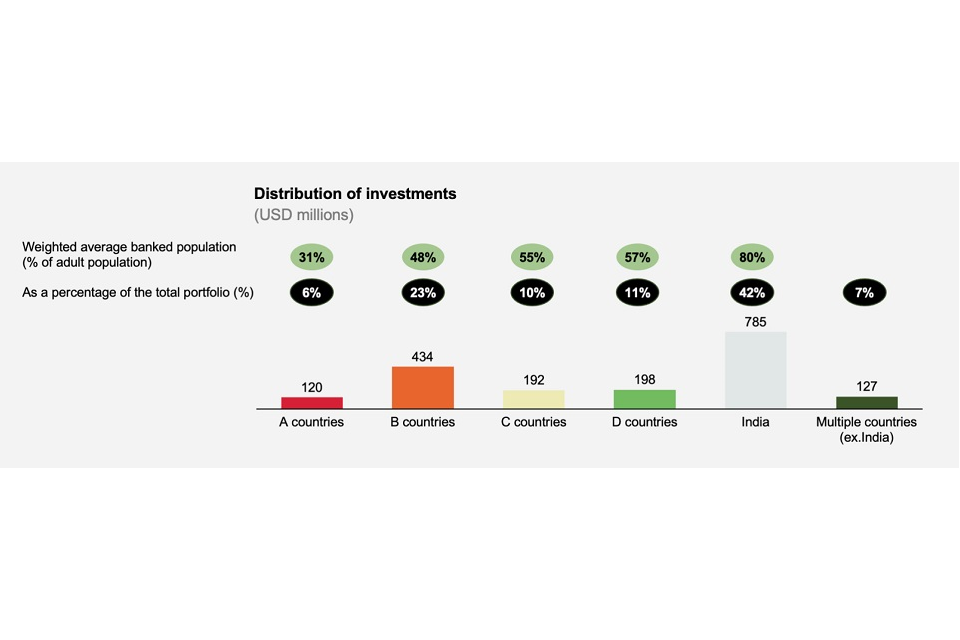

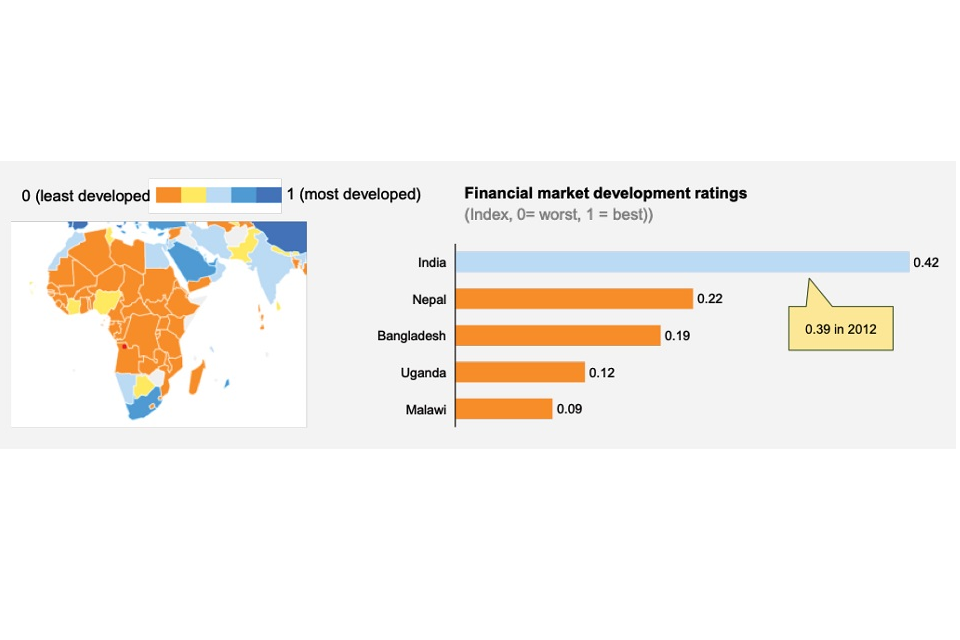

- there is a relatively even exposure of investments in harder ‘A/B’ (45%) compared with easier ‘C/D’ to reach countries and states[footnote 13] (46%) – India accounts for 42% of all investments by value. Outside India, ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ countries account for 6%, 23%, 10% and 11% of the portfolio respectively. The remaining 7% is invested in multiple countries. Using an estimation method[footnote 14] to include India, the total allocation of CDC’s investments in ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ countries is 22%, 23%, 17% and 29% respectively, with 8% in multiple countries/states Given that CDC prioritises ‘A/B’ over ‘C/D’ countries and states, this even exposure may not be ideal

- there are many MFI investments in the Indian direct and FIF funds’ portfolio – India has a large number of MFI investments by value and number. It is noted that India is a large country, and its GDP is on par with the whole of Africa. However, given the relative development of India’s financial system compared with financial systems in Africa, further analysis would be needed to understand the value added of allocating a large amount of funding to the sub-continent and in particular to the MFI sector. It is noted that the MFI investments have been successful, although there may now be an opportunity to refocus support to other types of FIs and sub-sectors

Theme 2: Reaching underserved households and scaling MFIs

This theme focuses on the extent to which CDC’s investments have reached underserved segments through the scaling of MFIs. This theme is meant to understand to what extent the investments are supporting household well-being in line with the CDC FI impact framework.

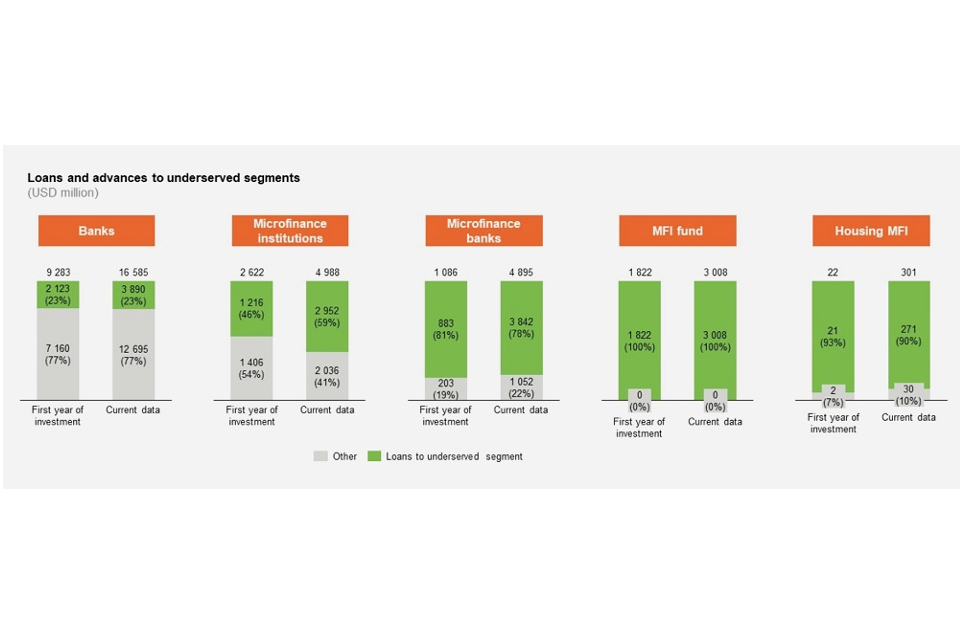

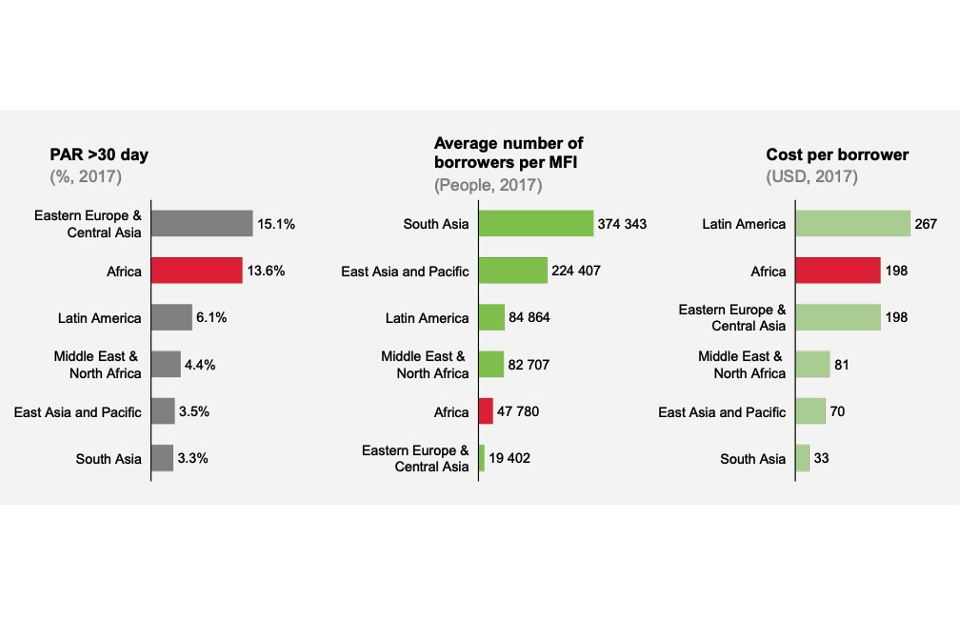

- MFIs have shown that they are able to reach the bottom of the pyramid although their scale is limited on an individual FI level – MFIs across the portfolio have shown to be reaching largely underserved segments. However, those in Africa have been less profitable and less able to reach scale. Further analysis on customer income levels is necessary to confirm this finding. It is also noted that certain banks engage in lending by using a microfinance model, have MFI subsidiaries, and/or engage in wholesale lending to MFIs and are thereby also reaching these segments

-

traditional, non-digitised MFIs in CDC’s African intermediated equity portfolio have had limited impact and have not reached scale – Across the continent, the stand-alone MFI lending model has been relatively unsuccessful (as measured by scale and financial sustainability). Most of CDC’s MFI portfolio in Africa has also suffered from poor performance with the exception of a few investments Additionally, in Africa, the MFI sector has recently experienced extensive competition from banks adopting MFI lending techniques and digital financial service providers. It is noted that CDC has recently been actively investing in DFS providers both directly and indirectly

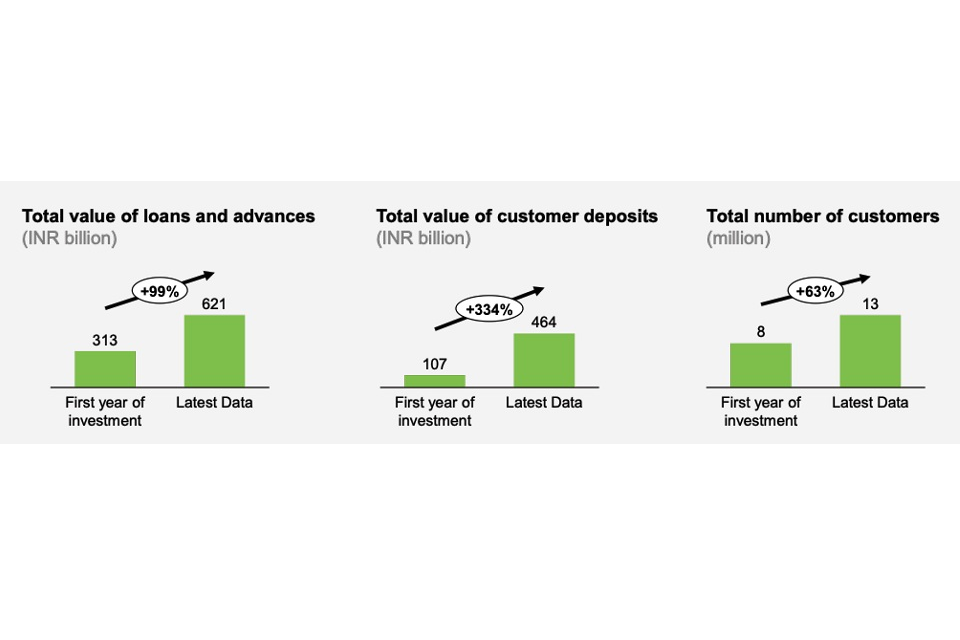

- CDC played an active role in scaling Indian MFIs – CDC has played an active role in supporting the scaling of MFIs to SFBs through the provision of important technical assistance (TA – including as board members) and long-term stable capital. The sector is now relatively well developed, and MFIs are able to raise funding from the capital market. CDC could consider scaling back its support for a large number of MFIs in India in favour of other geographies/sub-sectors. However, these SFBs could still benefit from the TA provided by CDC

Findings from the evidence review: There is an abundance of high-quality studies that consider whether vulnerable groups are included within the financial systems in Africa and South Asia. The mechanisms used by FIs to reach underserved groups are considered in a moderate number of these studies. There is convincing evidence that MFIs and fintechs that offer tailored products targeted to underserved groups are successful in effectively reaching and providing valuable services to these cohorts.

Theme 3: Providing appropriate capital to SMEs

This theme focuses on the extent to which CDC’s investments have reached SME segments across CDC’s product range. This theme is meant to understand to what extent the investments are supporting firm well- being in line with the CDC FI impact framework.

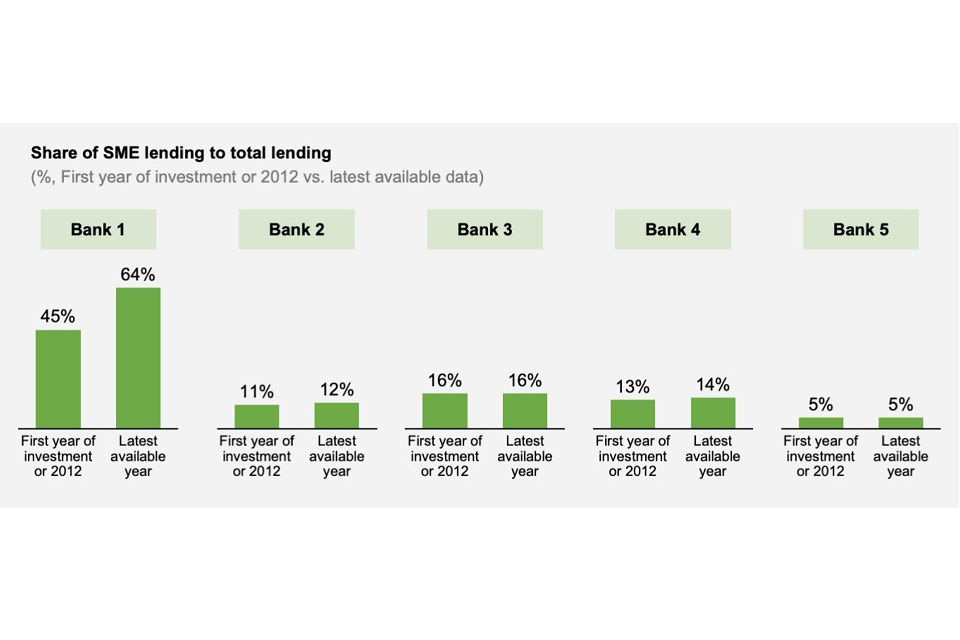

- SME lending has grown in absolute terms, but has been flat relative to the banks’ loan portfolios – Of the 5 commercial banks in CDC’s direct and FIF funds portfolio which had a core development thesis focused on increasing SME lending, only one bank has shown a significant increase in the proportion of lending to SMEs. In this case, CDC played an active role and exerted influence through its board position. During this time CDC provided key TA and strategic support. While a constant share of lending to SMEs can be considered impactful, if the overall loan book is growing, it is not clear if these banks are reaching more SMEs (or simply serving their existing client base which might be small). Altogether, in order to understand the impact of bank SME lending it would be important to understand the number and types of SMEs that are being served

- specialised debt funds offer a successful way to target SMEs and underserved segments in specific sectors – CDC invested in 2 specialised funds: Regional Education Fund for Africa (REFFA) and the Medical Credit Fund (MCF). Both funds have a unique lending model that provides lending either directly or through partner FIs to specific economic sectors and benefited from grant-based TA under CDC’s Catalyst Programme. Both funds have gained a strong reach of women, youth and SMEs.[footnote 15]

- debt funds specialising in investment in SMEs struggle to scale when structured as close-ended funds, that can impact their financial viability and level of scale – From an impact perspective, such investments are important vehicles for extending finance to businesses that would not otherwise receive credit from banks, although, due to their structure, they tend to struggle. When structured as closed-ended funds they are constrained by the limited period for generating positive returns on their lending portfolios, i.e. a longer fund life or a permanent capital structure would allow these types of funds to preserve and build technical capacity and allow for recycling of repaid loans, helping to scale impact

- there are several upcoming digital lending models that are reaching SMEs in the portfolio, although overall investment in these FIs is low – CDC’s total investment in fintech and digital financial service providers is sparse (less than 3% of the portfolio). Part of this low penetration is driven by the fact that most of these investments are through funds (as the ticket sizes are too small for CDC to invest in) and CDC’s implied investment stake gets diminished alongside multiple other limited partners (LP)

Findings from the evidence review: There is significant evidence documenting the dynamics of interactions between FIs and SMEs. However, the outcomes and impact of these interactions are not traced or investigated in the literature. When it comes to larger SMEs or corporates and the contribution FIs make towards their development, there is limited available evidence.

Theme 4: Financial market liquidity for emerging markets

This theme focuses on the extent to which CDC’s investments are providing liquidity to the markets it invests in, thereby allowing FIs to increase lending

- some of the dollar-denominated debt to FIs in African countries has not been successful – Dollar- denominated debt facilities have been successful in specific instances in times of crisis, but overall foreign currency debt has limitations, as financial intermediaries on-lending in dollars assume significant credit risk when lending to enterprises without dollar-based export earnings. Hedging facilities are either expensive or unavailable, as forward foreign exchange (FX) markets are relatively fragmented and underdeveloped in the majority of African countries. Some investments across the African direct debt portfolio were repaid early due to low appetite for dollar-denominated debt. Other complementary instruments, such as partial credit guarantees, guarantees on locally issued bonds by FIs and local-currency lending could be considered to the extent that this is within CDC’s mandate and risk appetite

- debt investments in India might be less relevant than in Africa given the relatively large scale of Indian public debt markets – Market fragmentation is an issue in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with an average corporate debt[footnote 16] to GDP ratio of less than 20% (with the exception of South Africa), while the equivalent ratio stands at 45% of India’s GDP (which is the size of the GDP of Africa). This implies that although the market is still developing, it is far larger and more liquid than markets in Africa, and corporate debt is therefore much more readily available. It is noted that some of the debt provided by CDC falls under the classification of Tier 2 capital[footnote 17] and hence further analysis would be needed to ascertain the shortage of this type of financing today, given that debt provides a much lower level of influence versus an equity investment

Findings from the evidence review: There is compelling causal quantitative evidence that financial inclusion increases economic growth. Modest evidence suggests that when FIs better manage their risks they are able to expand the credit they provide. This can contribute towards household investments into activities that improve future income opportunities (like education). There is a well- established need for capital in Africa and South Asia. There is also compelling evidence that small firms that receive capital injections are more likely to grow and employ staff. This indicates that there is a relationship between increased capital provision in a market and better outcomes for firms.

Theme 5: Developing capital markets

This theme focuses on the extent to which CDC’s investments are building capital markets across its relevant geographies to enable firms to access long-term financing.

- investments in the broader financial system and capital market have been lacking across the portfolio, particularly on the direct side – Almost all of CDC’s direct investments are in MFIs or banks. In line with CDC’s recently adopted FI strategy (2019), which emphasises the role of developing capital markets, there is an opportunity to consider increasing investment in insurance companies, pension managers, asset managers, fintechs and market infrastructure providers (credit bureaus and exchanges).[footnote 18]

- support to initial public offerings (IPOs) and listing of FIs is limited – CDC has supported SFBs in India to build their asset bases and speed up the listing process. As an anchor investor, CDC also supported Habib Bank Limited (HBL) in Pakistan in completing its privatisation process. However, there could be an opportunity to support more listings and private placements across both Africa and South Asia

-

multiple products can be used to support capital markets – While the products that CDC has used to support capital market development (such as private equity (PE) funds, direct investing and risk-sharing agreements) are relevant, there are other relevant products that could be utilised:

- direct lending/sector-specific lending, e.g. credit lines for directed lending to SMEs, mortgages, female borrowers, and so on. It is noted that CDC’s debt funds in the catalyst portfolio (REFFA and MCF) are already engaging in blended finance initiatives, i.e. lending jointly with partner FIs

- first loss and partial credit guarantees to FIs could be used to increase the risk-appetite of financial intermediaries targeting specific market sub-segments (such as SMEs)

- the role of SME debt and equity funds could be expanded across the portfolio as they are a conduit for directly providing long-term finance tailored to the needs of SMEs

- given the small size of local capital markets across most countries in Africa, CDC could consider investment in domestic wholesale development banks that encourage lending to SMEs. To do so, CDC could provide private banks with instruments such as partial credit guarantees and credit lines, thereby leveraging the private sector banks’ expertise in assessing credit risks, while intervening in a manner that is market-catalytic

Findings from the evidence review: The aggregate direction of evidence is positive, as an overwhelming number of studies show that market context significantly affects the ability of FIs to deliver impact. The main components supported by the evidence are infrastructure (both physical and financial), institutions, and regulations.

Theme 6: Risk-sharing agreements and counter-cyclical finance

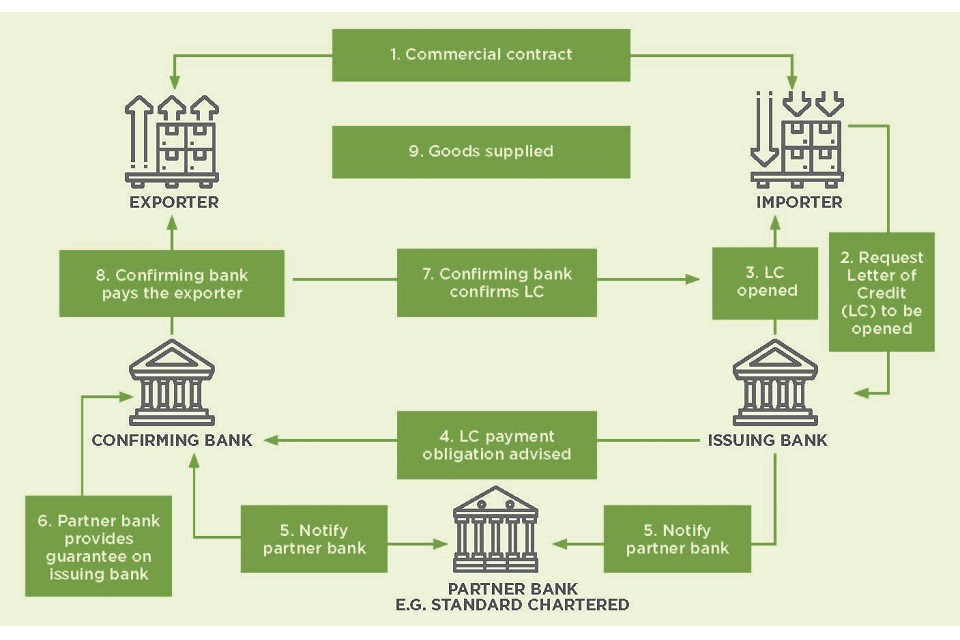

This theme focuses on the extent to which CDC’s risk-sharing investments are delivering impact as envisioned by their development thesis, i.e. to alleviate issuing bank limits and reach a broad range of ‘A’ and ‘B’ countries. The main aim of this theme is to ascertain if CDC’s investments are making trade financing more accessible to firms and countries who need it.

- there has been good overall coverage of ‘A/B’ countries (accounting for 70% of trade finance (TF) in 2019) – In 2019, there was been good coverage of TF across ‘B’ countries that accounted for 67.7% of all trades, although the coverage to ‘A’ countries remains low at 2.6%. A sizeable share of trades supported are to relatively lower-priority ‘C’ countries. Bangladesh, Ghana, Kenya and Egypt (‘C’ countries) accounted for 29.7% of all trades supported, while CDC did not engage in facilitation of trade in any ‘D’ countries

- issuing bank limits is not the only challenge limiting TF[footnote 19] – CDC’s TF investments have placed a large focus on mitigating confirming bank limits on countries and issuing banks, although recent studies have cited multiple reasons for TF rejections. Studies such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) 2018 survey[footnote 20] and International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) 2018 survey have cited a variety of other reasons for TF rejections which range from anti-money-laundering (AML) issues to country limits and global de-risking (confirming banks). CDC is working to address some of these issues, and there would appear to be an opportunity to work with issuing banks directly (banks that issue TF products) to understand the main drivers for rejected letters of credit and formulate a strategy that best addresses these challenges. It is noted that CDC is already beginning to engage in this space

- lack of diversity in partner banks supported – Of the 7 MRPA investments made by CDC,4 are to Standard Chartered Bank (SCB) – a dominant player in the global TF market. SCB’s total TF facility was USD 400 million compared with the other 3 partners (2 of which are African partner banks[footnote 21]), which collectively amounted to USD 300 million.[footnote 22] It is noted that, according to the AfDB, SCB is the largest TF confirming bank in Africa, and further analysis would be required to ascertain if CDC could be potentially reinforcing this market leader position. It should be noted that the TF strategy envisages entering into new partnerships with other partner banks and, since forming a standalone trade and supply-chain finance team, CDC has been ramping up new partner deals rapidly

- CDC’s supply-chain finance product is partly limited by a lack of local partner banks – The supply- chain finance product has had limited reach. Additional local partner banks and partnerships with more anchor buyers could be explored to scale up the facility that could potentially be impactful in securing financing for SMEs and helping them manage their working capital. Another approach CDC might consider is supporting the establishment of factoring platforms, which build on the creditworthiness of the buyer while circumventing the high costs associated with the provision of banking services

- counter-cyclical finance products are important, but a broader toolkit may be needed – CDC has been able to play an active role in mitigating the effects of various crises on economies and firms. One such example is the Sierra Leone (SL) risk-sharing facility during the Ebola crisis in West Africa. Although these investments were highly relevant during these periods, CDC may benefit from a broader toolkit of products that would increase its response to various types of financial crises. Different crises require different responses depending on whether they are local, regional or global and also depending on the macroeconomic structure of the country and market being supported

Findings from the evidence review: There is limited evidence regarding the impact of TF. However, a high-quality generally applicable study indicates that medium to long-term trade credit is causally linked to export growth in Africa and Asia. There is limited but positive evidence that targeting TF towards those industries that rely heavily on the availability of working capital is more likely to eliminate a binding credit constraint for promising SMEs.

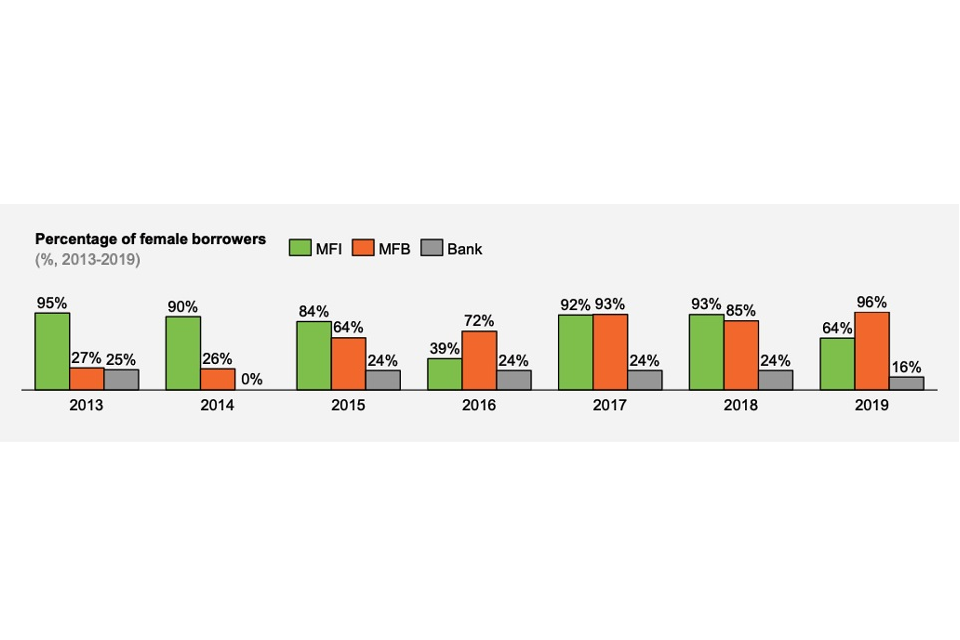

Theme 7: Gender

This theme focuses on the extent to which CDC’s investments have reached women in general across all investments.

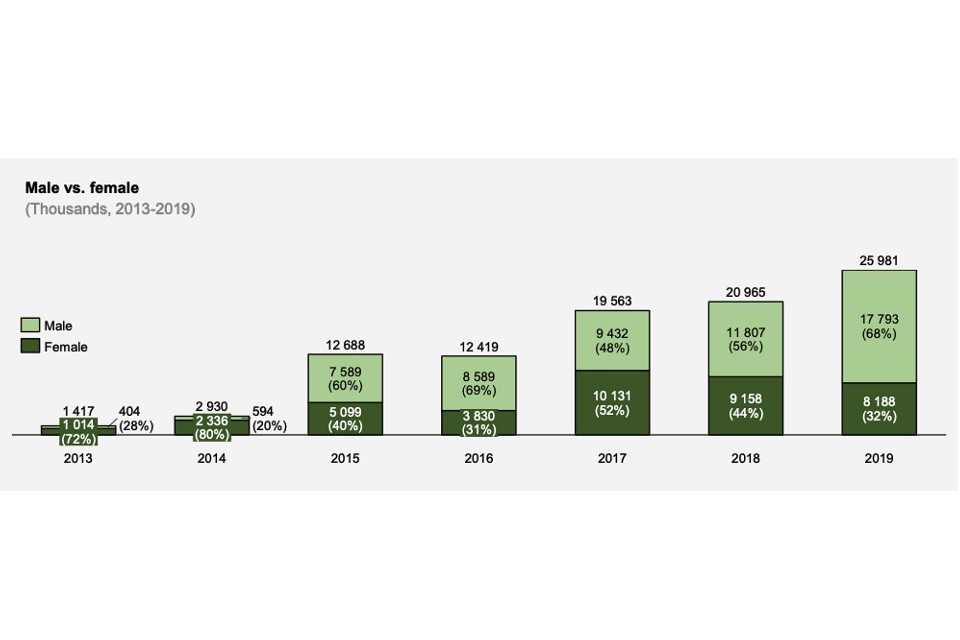

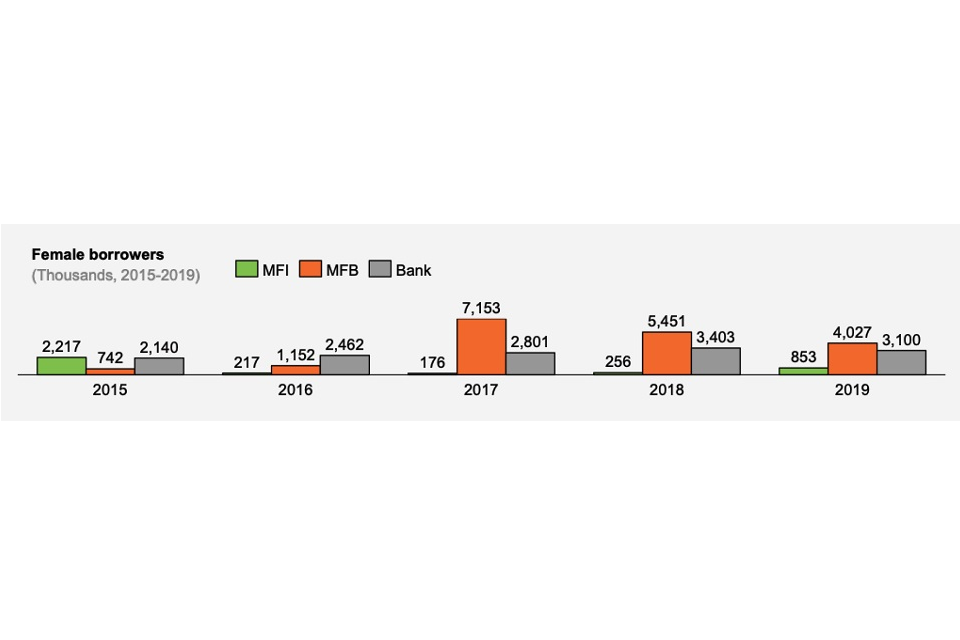

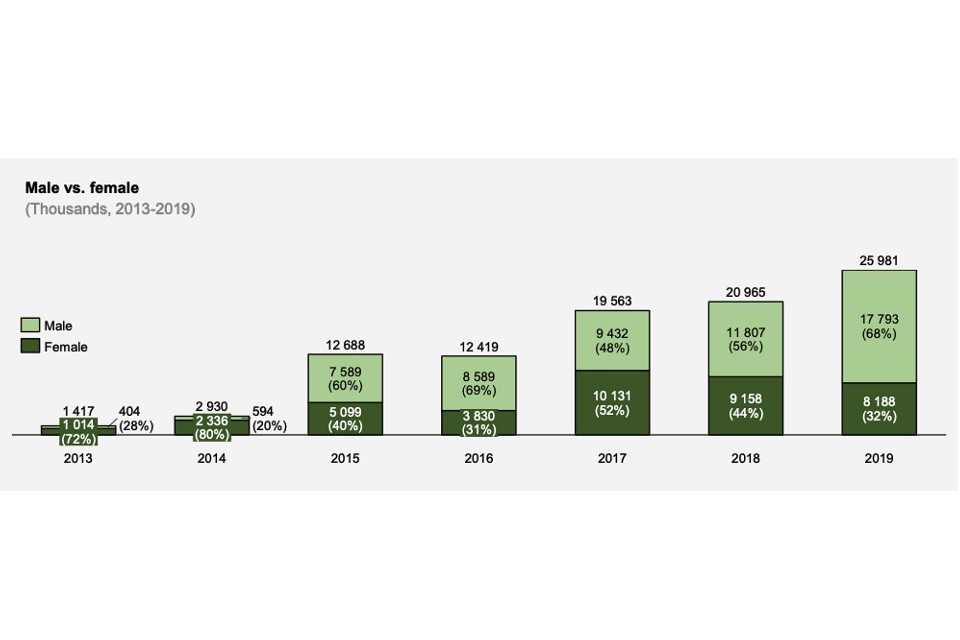

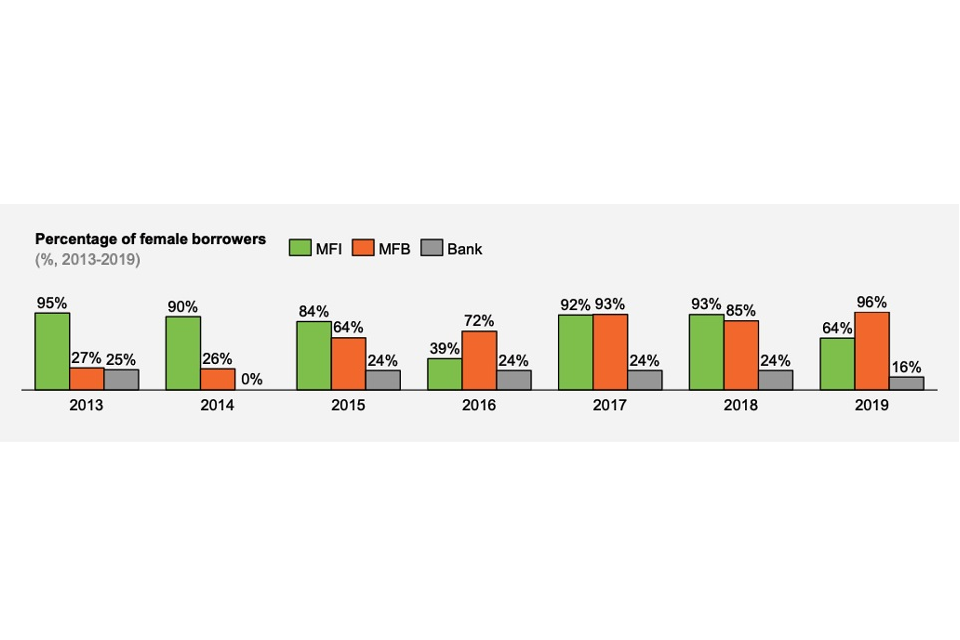

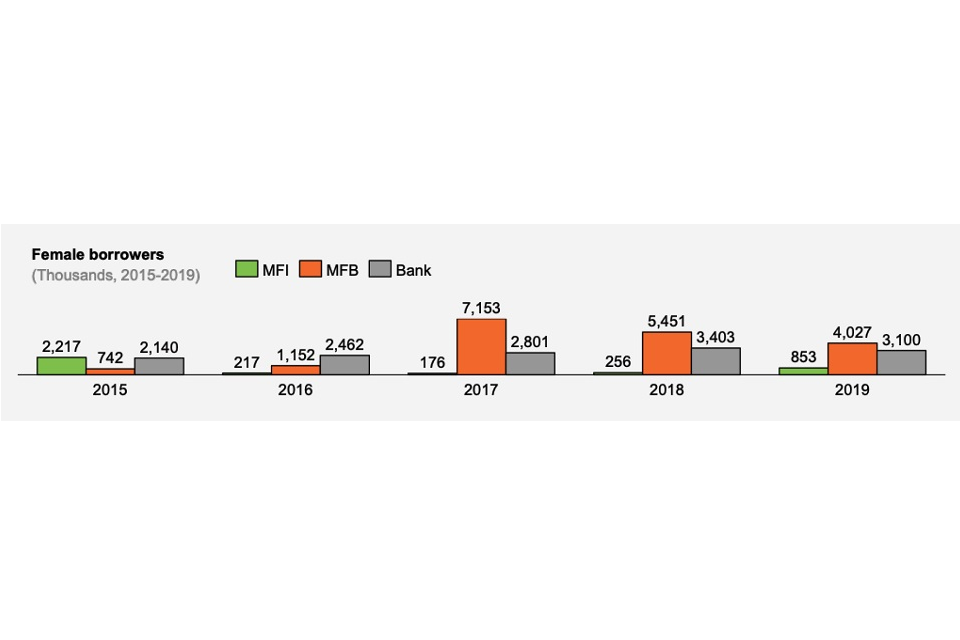

- there is a lack of evidence around efforts to increase gender-based lending in banks – On average, women made up 22% of bank customers from 2013 to 2019. This is in stark contrast to MFBs, which averaged 66% over the same period.[footnote 23] As at 2019, women accounted for 96%[footnote 24] of customers in MFBs while in banks they accounted for 16%. However, in terms of the absolute number of customers, microfinance banks (MFB) served only about 900 more female customers than banks. Thus, owing to their scale, banks have been able to reach almost as many women as MFBs

- there is a lack of a consistent approach to gender inclusion across DI theses of investments – Additionally, the extent to which a concerted effort was made with CDC’s investments to target women is unclear. A more consistent approach to DI regarding gender should be adopted to ensure that all CDC’s investments are working towards this common goal – noting that the gender function is still ramping up: CDC launched its gender strategy in 2018, while more than 90% of investments (by number) pre-date the adoption of the gender strategy

Validating the intended outcomes and impacts in CDC’s FI impact framework using external evidence

The CDC FI impact framework envisages that investment in FIs leads to a strong, inclusive financial system, GDP growth and poverty alleviation that results in improved well-being for households and firms. A review of existing literature offers additional insights into whether the causal linkages within CDC’s FI impact framework hold true.

-

there is limited evidence linking FIs to firm and household well-being – The CDC definition of well-being encompasses multiple aspects (i.e. growth, resilience, consumption and wealth). The evidence available for each of these aspects originating from an interaction with FIs is not substantial, although there is greater evidence available for firms than for households. However, the evidence for firms is dominated by evidence for micro-enterprises. Further, the definition of firm well-being when it comes to micro-enterprises is not easy to disaggregate from household well-being, as such small firms are frequently intermingled with households financially. There is no formal evidence regarding larger SMEs or corporates.[footnote 25]

-

the logic behind the ultimate impact of strong inclusive financial systems on GDP growth (and eventually on poverty alleviation) is verified by the evidence – The evidence proves a causal relationship between strong, inclusive financial systems and GDP growth. On the other hand, the evidence that strong, inclusive financial systems lead to poverty alleviation is inconclusive, although the evidence does indicate that access to financial services in the correct context can support poverty alleviation

CDC’s value addition activities

Value addition activities are support provided by CDC in addition to the capital it provides. The main value addition activities that CDC provides includes (not exhaustive):

- supporting FIs by strengthening their financial crimes compliance and integrity controls to ensure they adhere to regulations in the markets that they operate in

- supporting FIs in building environmental and social (E&S) standards, capacity and processes. Typically, this includes environmental and social management systems (ESMS), policies and procedures, capacity building, and for FI equity investments, potentially an E&S committee to help drive change. The E&S team also supports financial inclusion, literacy, and increasingly, climate change

- supporting FIs to consider gender from an employment and customer perspective and report on key gender metrics with the aim of achieving a balance between males and females across their business operation

- ensuring FIs understand, adopt and implement customer protection principles where necessary

- supporting FIs to monitor and measure development indicators

While some of these functions are recent, and in a ramp-up phase (gender), they play an important role in achieving the DI thesis set for the FIs. They ensure that CDC is taking a holistic view to development, that FIs are able to deliver impact as envisioned in the DI thesis and that these FIs are setting an example in the markets in which they operate. Based on the materials reviewed, it is noted that most of these interventions are concentrated on direct investments, and going forward, CDC could consider more support to funds, even though standardisation of monitoring across funds will be harder to achieve, given multiple LPs in a fund, not all of whom will have the same strategies.

Findings from the evidence review: Most of the evidence regarding value addition centres on TA. The evidence indicates that appropriate medium to long term TA paired with an investment is causally linked with an increase in impact created by the FI’s involvement.

General observations and data limitations

While analysing the FI portfolio several items emerged that were general in nature, and these have been captured within this section. Some of these include:

- inconsistent and general lack of information on underlying households and firms being reached – CDC’s current impact reporting is largely informed by public information for direct investments (partly resulting from stringent insider trading requirements – where all shareholders should only have access to the same information) and fund reporting for indirect investments. With the exception of a few selected direct and fund investments, general reporting on end beneficiaries (e.g. reporting on whether FIs are fulfilling their DI theses with regard to reaching SMEs and low-income customers, etc.) is missing. Impact reporting could be improved by requesting FIs and funds to provide more detailed information on underlying borrowers and customers. Such information is integral to measuring impact and to strengthening CDC’s strategy both as regards the choice of investees and in understanding and supporting product development

- lack of a consistent definition for underserved and SME segments – While analysing the data it was noted that several DI theses referred to SMEs, women and underserved segments generally without referring to their relative size or defining these segments clearly. While it is a challenge, it would be beneficial to standardise this across CDC’s FI focus countries and FI types in order to enhance impact reporting

- there is a general lack of data on Indian investments’ regional loan exposures – Based on the investment reporting and public information, it was not always possible to understand how loans were being disbursed across Indian states (partly resulting from stringent insider trading-related data sharing requirements)

- lack of data on the benefits of TF to partner banks and beneficiaries being reached – Overall it was not possible to ascertain the benefit that CDC provides to partner banks without understanding the total support these partner banks receive from other development finance institutions (DFIs) and to what extent their TF portfolios have grown. Also, the extent of the benefits to the underlying beneficiaries was not clear due to lack of data

- inconsistent public information – Several companies were unlisted or did not publish financials, which limited the exhaustiveness of the analysis. Also, most companies published inconsistent data from year to year and when compared with each other. This limited the consistency of data collected across years, across FIs and markets

- DI theses in several cases are vague – Overall it is difficult to measure impact due to the opacity of these DI theses, and the specificity of the theses could be improved. The theses could also be standardised to a greater extent so as to enable comparison across investments and to encourage the collection of comparable data across investments

Topics for in-depth studies

There are multiple topics that have been identified for further analysis and exploration through in-depth studies. The aim of these studies will be to provide more insights into which investments are having/had the most impact, what types of data FIs collect and how CDC can in future improve its impact, as well as its monitoring and evaluation (M&E) processes. The list below identifies areas for potential in-depth studies, and further work needs to be carried out to prioritise and understand which are the most important topics for CDC given the distribution and size of the portfolio by region, product, FI type and other factors. The topics and overarching evaluation questions have been listed below.

- scaling MFIs – What is the impact of scaling MFIs on firm and household well-being? This topic aims to understand CDC’s role in scaling MFIs in India and what impact this has had on improving household well-being

- SME financing – What is the optimal financing method to support SMEs? This topic aims to understand the benefits and drawbacks associated with alternative methods of reaching SMEs and which methods have the greatest reach

- SME impact – What is the impact of finance on firm well-being? This topic aims to understand the impact of CDC’s support to banks on firm-level well-being, i.e. SMEs

- trade finance – What are the benefits and impact of trade finance at the partner FI, issuer FI, and importer level? And what are the benefits and impact of trade finance during COVID-19 at the partner FI, issuer FI, and importer level? This topic aims to understand the extent to which CDC’s trade finance facilities are having an impact on its partners and firms

Introduction

Objectives

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) contracted Genesis Analytics and IPE Global to design and implement an evaluation of CDC’s investments in FIs. The purpose of this evaluation is to better understand the development outcomes and impacts associated with CDC’s investments in the financial sector. The evaluation consists of 3 components, namely a portfolio evaluation, evidence review and a series of in-depth studies.

This document presents the combined findings of the detailed portfolio and evidence evaluation conducted over the period of January 2020 to April 2020.

The evaluation has the following objectives:

- to understand the extent to which CDC’s FI investments are on track or have achieved their respective developmental impact (DI) thesis

- to understand the extent to which CDC’s investments have had an impact in line with the CDC FI impact framework

- to enable cross-portfolio comparisons of impact to the extent possible, e.g. comparing the impact of: direct vs. indirect investing, debt vs. equity, Asia vs. Africa, banks vs. MFIs vs. digital financial services (DFS), and specialised SME funds vs. generalist SME funds

- to identify emerging themes and investments for in-depth studies that could provide a deeper understanding of lessons learned from the FI portfolio

- to provide insights on the existence, quality and quantity of evidence that support CDC’s FI impact framework and the derived evaluation questions

The findings of the evaluation have been informed by a combination of publicly available data, peer-reviewed journals, CDC internal monitoring data[footnote 26] and meetings with CDC’s relevant investment teams.

Scope of the evaluation

In order to achieve the above objectives, the following scope of investments were defined for the evaluation.

- all current direct FI investments in Africa and South Asia (including any exits from post-2012 direct investments) across the FI Equity team, FI and corporate debt teams and the trade and supply-chain finance team

- all current fund commitments in Africa and South Asia with at least one underlying FI investment across FI focused equity funds,[footnote 27] selected debt funds (these are funds that lend directly or in partnership with FIs to SMEs and retail clients) and generalist equity funds with at least one active FI investment – a detailed evaluation of these investments has not been conducted, although the overarching development indicators have been assessed.[footnote 28]

- in evaluating each FI, over 500 documents and over 5,000 variables were reviewed

- in reviewing the evidence supporting CDC’s FI impact framework, 441 studies were identified and reviewed. A total of 271 studies (61% of the total studies found in the search process) were of sufficient quality to be included in the coding process for the evidence review

There are some investments that have been made recently (i.e. in 2018, 2019 and 2020). These investments are covered briefly, as it would be too early to assess impact given the availability of data and the limited duration for an FI to implement its strategy post CDC’s investment. It is important to note that this evaluation focuses only on the underlying investments in the case of fund investments and provides an overall performance of the funds based on these investee reviews, where applicable.

CDC’s approach to financial sector development

This section presents a high-level view of CDC’s approach to development from an FI sector perspective. The section describes:

- CDC’s FI impact framework

- the DI grid

- CDC’s approach to monitoring DI and the DI thesis for each investment

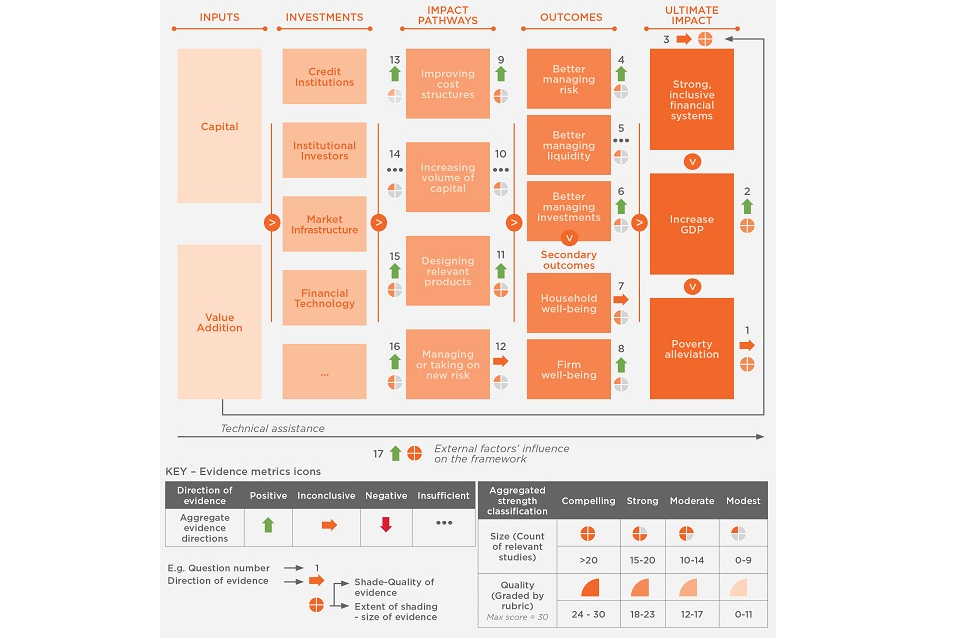

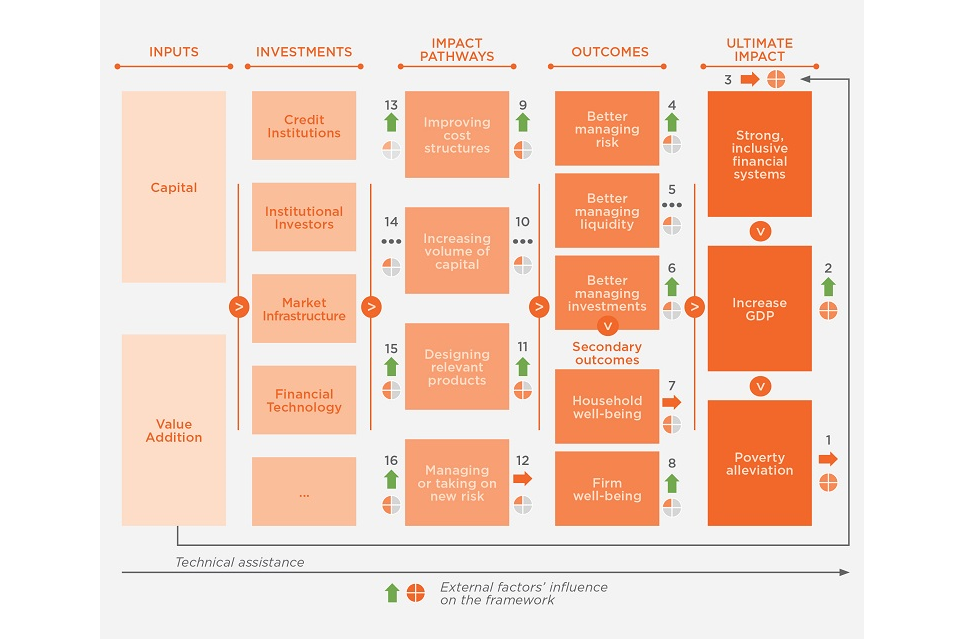

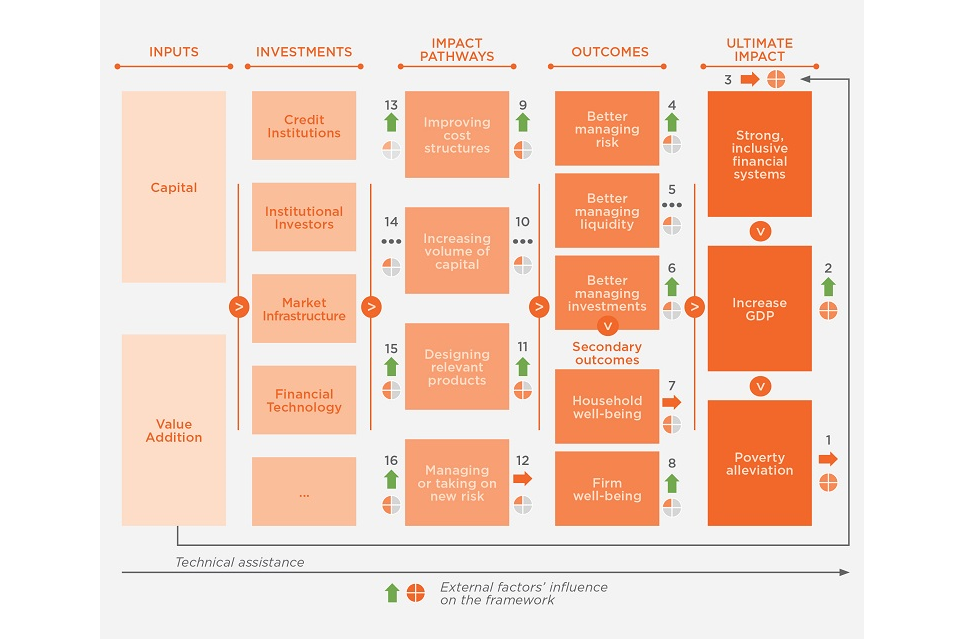

CDC’s FI impact framework The figure below presents CDC’s FI impact framework. The framework is built on the rationale that through the provision of capital and value addition[footnote 29] (TA) to financial sector investees and intermediaries, impact is achieved through 4 main pathways. These pathways include:

- improving costs structures – Working with institutions or enablers to reduce the cost to serve, improving unit economics and becoming more cost-efficient, ultimately accruing benefits to the customer

- increasing the volume of capital – Providing capital required to scale FS, particularly by increasing the provision of capital to underserved or high-growth segments or facilitating the entry of new capital

- designing relevant products – Diversifying the suite of financial products available in the market, including retail, corporate, and investment products. Focusing on appropriate delivery and availability of those products in a scalable and sustainable way

- managing or taking on new risk – Motivating and incentivising FIs and market enablers to manage their risk better, or learn to take on new risk; normalising perceived risk, enabling more sophisticated risk- based pricing

Through these pathways, it is envisioned that CDC’s FI investments will lead to improved household and firm well-being, which will lead to inclusive financial systems, more economic growth and an overall reduction in poverty. The size[footnote 30] and quality[footnote 31] of the studies are the 2 dimensions by which the strength of evidence per research question is defined. A key goal of the evidence review is to provide guidance on the plausibility of the causal relationship envisaged in the CDC FI impact framework. To aid this process, the aggregate direction[footnote 32] of the evidence has been represented per question. The evidence review metrics are mapped against the CDC FI impact framework in Figure 3. The question numbers are linked to the question text in Table 1. The 3 metrics summarising the strength and direction of evidence per question are shown under each question number[footnote 33] in Figure 3. For example, Question one (Does access to FS reduce poverty?) has a compelling size of evidence, a strong quality of evidence, and the direction of evidence is inconclusive.

Figure 3: CDC’s FI impact framework

The portfolio evalution has been grounded in CDC’s FI impact framework. Each investment has been assessed along its DI thesis and mapped according to the CDC FI impact framework. A detailed review of all investments has not been included in this evaluation report. However, the findings of the evaluation have been presented based on themes that emerged while reviewing the investments. The portfolio evaluation is guided by the CDC FI impact framework and aims to assess impact against the framework to the extent possible. Given the overall data limitations, primary outcomes, secondary outcomes or ultimate impact was not possible to assess, although in some cases this has been inferred.

The evidence review has been conducted in line with the FCDO’s best practice methodology for synthesising research. This method is designed to gather high-quality evidence that answers specific evaluative questions. A total of 441 studies were identified and reviewed. A total of 271 (61%) of the 441 studies were of sufficient quality to be included in the coding process.

Table 1: Summary of quality, quantity, and direction of evidence for evidence review questions

| Evidence metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question # | Evidence review questions | Size & Quality | Direction |

| Ultimate impact | |||

| 1 | Does access to FS reduce poverty? | ||

| 2 | Do strong, inclusive financial systems generate GDP growth? | ||

| 3 | Do investments in FIs help build strong inclusive financial systems? | ||

| Outcomes: Do FIs influence firm and household well-being? | |||

| 4 | Do FIs influence risk management of end-users? | ||

| 5 | Do FIs influence liquidity management of end-users? | ||

| 6 | Do FIs influence investment management of end-users? | ||

| 7 | Does better managing risk, liquidity and/or investment affect household well-being?* | ||

| 8 | Does better managing risk, liquidity and/ or investment affect firm well-being? | ||

| Impact pathways to delivering primary set of outcomes | |||

| 9 | Do FIs that experience an improvement in cost structures generate positive outcomes for firms and households? | ||

| 10 | Do FIs with increased volumes of capital generate positive outcomes for firms and households? | ||

| 11 | Do FIs that design relevant and sustainable new products generate positive outcomes for firms and households? | ||

| 12 | Do FIs that better manage or take on new risks sustainably generate positive outcomes for firms and households? | ||

| Inputs to support impact pathways | |||

| 13 | Can an intervention in an FI from a DFI such as CDC be associated with an improvement in cost structures? | ||

| 14 | Can an intervention in an FI from a DFI such as CDC be associated with an increase in volumes of capital? | ||

| 15 | Can an intervention in an FI from a DFI such as CDC be associated with the design of relevant products? | ||

| 16 | Can an intervention in an FI from a DFI such as CDC be associated with an improvement in managing or taking on new risks? | ||

| External factors’ influence on the framework | |||

| 17 | Does market context affect FIs’ ability to deliver outcomes and impacts? |

Table 1: *[footnote 34]

The evidence review and portfolio evaluation are complementary but originally set out to understand the CDC portfolio through different approaches that relate to the CDC FI impact framework. The evidence review unpacked external evidence for the causal pathways linking investments to the ultimate impact envisaged by CDC. The portfolio evaluation considered internal CDC investments and their relationship with the ‘Impact Pathway’ segment of the CDC FI impact framework through the DI theses per investment. The portfolio evaluation summarised the findings from this analysis in 7 key themes.

For the purposes of alignment, the key findings related to the evidence review questions have been mapped to the 7 themes identified by the portfolio evaluation in this combined report. The evidence related to each theme of the CDC FI portfolio evaluation is summarised in a box at the end of each theme’s section.

DI grid[footnote 35] For each investment that is made by CDC, the DI grid is utilised to map and rate the investment in terms of potential impact. The grid is made up of 2 main variables as explained below:

- geography – Investments are classified according to their geographies, i.e. the most difficult markets and/ or the least developed from a financial sector perspective

- business sectors – This includes the propensity to generate employment, rated as high, medium or low

Throughout this document, reference is made to the geography component of the grid when assessing the impact of certain investments and also the overall exposure of CDC’s FI portfolio.

The DI thesis and FI portfolio monitoring processes The main monitoring processes that CDC uses for its FI portfolio include the following:

- Quarterly Portfolio Reviews (QPRs) – Records key developmental indicators to track whether the DI thesis is on track for an investment

- Annual Monitoring Reports (AMRs) – An annual process of recording broader metrics such as employment, gender-related metrics, taxes paid, youth employment and so on

It is also important to note that CDC started developing a concise, explicit statement of its intended DI (a ‘DI thesis’) for all investments from the beginning of 2018 and retrospectively for investments made after 2012 with certain exceptions. This evaluation is informed by the mentioned monitoring reports and publicly available information (further elaborated in the methodology section of the annex).

Portfolio description

As at 2018,[footnote 36] CDC’s total portfolio across all sectors stood at USD 5.64 billion (GBP 4.3 billion). Roughly 46% of the portfolio is invested through funds and the rest is through direct equity and debt investing. Based on the same annual report, the FI portfolio accounts for 22% (USD 1.24 billion) of the total portfolio.[footnote 37] It should be noted that CDC’s portfolio value in its annual report is based on market valuations and excludes portfolio realisations.

Description based on product

Based on the provided data, as at December 2019, CDC’s total active (excluding exited and written off investments) portfolio at original cost stood at USD 1.67 billion.

For the purpose of this document, CDC’s FI portfolio is presented based on historical original cost and includes investments that have been realised or written off in order to show how CDC has historically deployed its funds. Based on this adjustment, CDC’s FI portfolio amounted to USD 1.86 billion[footnote 38] across 180 unique investments. 71% of the portfolio consists of some form of direct equity or debt investments, 25% is through all funds (debt funds, FIF funds and generalist funds) and 4% of the portfolio is in MRPAs[footnote 39] – such as TF (TF), supply- chain finance (SCF) and corporate debt-risk sharing facilities.

This evaluation focuses on only 88 out of the 180 investments, given that the other 90 investments belong to generalist funds that do not have a specific financial sector focus, one investment has no quarterly reporting data as yet, and one fund investment had a close to zero investment value.

Figure 4: Portfolio breakdown - by product

Note: The figure above is based on original cost data rather than current market valuations. It also includes exited/realised investments. Funded MRPAs adjusted for utilisation rates and unfunded MRPAs adjusted for utilisation and a capital charge of 10% (MRPA data is shown exclusive of fees). Mixed refers to investments receiving funding from more than one product.

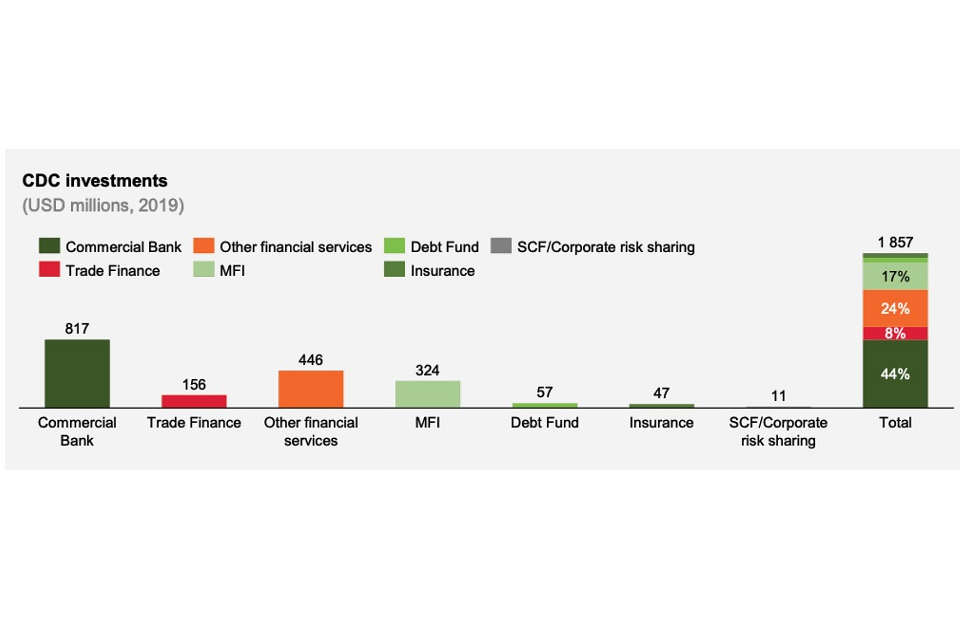

Description based on FI type

In the figure below, we present CDC’s FI portfolio by the different institutions that it invests in.

Figure 5: Portfolio breakdown - by FI type

Note: Other FIs include digital financial service providers, pension funds, payments companies, housing finance (HF) companies, diversified product lenders, asset financiers and leasing companies. In this image TDB Africa (a direct debt investment)[footnote 40] has been grouped with TF as the funds are primarily used for TF.

About 44% of CDC’s FI portfolio is invested in commercial banks, followed by other FIs that account for 24% and MFIs that account for 17%. One direct investment in India Infoline Finance Limited (IIFL)[footnote 41] accounts for approximately USD 198 million of the total amount invested in other FIs (USD 446 million) – i.e. approximately 44.4% of other FIs.[footnote 42]

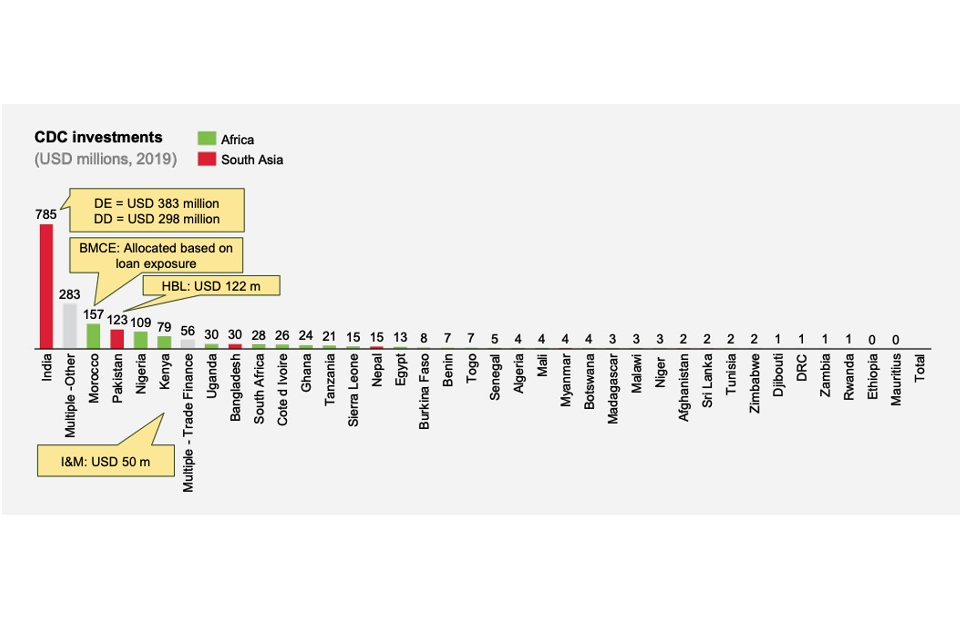

Description based on region

Figure 6: Portfolio breakdown - by country of main operations

Note: Called out Investment values available from CDC’s website

Based on a regional view of the portfolio, investments are concentrated in 5 main countries that account for 67% of investments by value. These are India, Morocco, Pakistan, Nigeria and Kenya.

Overview of direct investments

A detailed overview of CDC’s direct investments indicates that all direct African investments are in banks, and all direct investments in South Asia are in banks, MFIs or other non-bank credit providers. A review of the risk- sharing agreements show that a large proportion of these investments are with SCB.

Overview of fund investments

- debt funds – Collectively, these account for USD 57 million in investments. These funds tend to focus on lending to SMEs and/or individuals either in partnership with other FIs or directly

- FIF funds – A total of 10 financial institution-focused (FIF) funds are reviewed in this document. Collectively, these funds account for 59 unique investments worth USD 100 million (average ticket size of USD 1.7 million). From an FI perspective, 50% of the investments are in other FIs,[footnote 43] 26% are in MFIs, 14% are in commercial banks and 10% are in insurance companies. From a regional perspective, 52% are in India and the rest are relatively evenly spread across multiple countries

- generalist funds – Collectively, these funds account for 96 investments,[footnote 44] accounting for USD 307 million, resulting in an average investment value of USD 3.2 million. It should be noted that these investments have not been reviewed beyond this section. From an FI perspective, 45% are in commercial banks, 40% in other FIs, 12% in insurance and 3% in MFIs. On a regional level, generalist fund investments are concentrated in Nigeria (25%), India (17%), South Africa (7.5%), Kenya (6.5%), Ghana (6.2%), Cote d’Ivoire (6.2%) and Egypt (4.2%).

Overview of instruments used by CDC to deliver impact

In order to deliver impact, CDC has used 6 main instruments across its portfolio that are described below:

- equity capital – Generally used to gain an equity stake in a business and a board seat so as to influence the strategy of an FI. Through this instrument, a financial institution is generally able to strengthen its equity base in order to comply with regulatory capital adequacy requirements. Additional capital allows the bank to expand lending, increase leverage and grow its overall balance sheet

- Subordinated debt to existing senior debt and qualifying as Tier 2 capital – Generally used to strengthen the capital base of an FI to allow it to expand its balance sheet. A slightly more limited instrument than equity, as the ability to influence the strategy of an investee may be limited

- intermediated equity – Provided through funds to invest in underlying companies with the same effects as equity capital, although CDC would have less influence depending on its implied stake

- intermediated debt – Provided through funds or holding companies for on-lending purposes

- senior unsecured debt, ranking in pari-passu[footnote 45] with all senior obligations of the borrower – Generally used for on-lending to any customer or specific customer segments. This type of instrument is used to encourage FIs to lend to a particular sector/segment and provide liquidity

- risk-sharing agreements – This instrument is generally used to encourage FIs to target specific segments and increase lending to customer segments that would not have otherwise received credit. The aim of this instrument is to build capacity for FIs, to allow them to experiment with on-lending to certain segments and eventually for the FIs to be able to do it on their own. This form of support also allows an FI to be able to release regulatory capital and allocate it to other forms of lending.

Portfolio description summary

From a descriptive analysis of CDC’s FI portfolio, the following emerges:

- seventy one percent of all investments are direct, 25% through funds and 4% are through MRPAs

- thirteen investments receive multiple funding lines either through direct or indirect products

- direct investments have larger average investment values (USD 45.6 million) than fund investments (USD 2.7 million)

- FIF fund investments are evenly spread between South Asia and Africa, while generalist fund investments are more focused on Africa

- microfinance institutions (17%) and commercial banks (44%) account for 61% of the portfolio by value

- funds are invested in a more diverse range of FIs using lower average investment values

- forty two percent of investments by value are in India and the remaining majority are in Africa and South Asia

Overall portfolio DI summary

This section provides an analysis of the overall performance of CDC’s FI portfolio against:

- their respective DI thesis

- CDC’s corporate and FI sector development indicators, which include total loans and customers (FI sector DI indicators) and jobs sustained/created, female employees and taxes paid (CDC corporate indicators)

The findings are analysed from a region, product and FI type perspective. The final part of this section provides an overall summary and lessons.

Performance against DI thesis

CDC started developing a concise, explicit statement of the intended DI (a ‘DI thesis’) for all investments from the beginning of 2018. Prior to this, information about the investments’ intended impact was included in the investment committee (IC) paper for each investment and discussed at the IC; the articulation of the intended impact varied across investments.

DI theses have been developed retrospectively for all post-2012 commitments (which includes all direct deals in this study, except for a few investments made pre-2012 and any direct investments that had already been exited). For those investments without a DI thesis, the evaluation team reviewed the original IC paper and inferred a DI thesis for the purposes of this assessment.

The assessment against the respective DI thesis was conducted by the evaluators across the 88 reviewed investments and 10 FIF funds. In order to facilitate a measure of achievement, the following discrete performance criteria are defined to describe the performance of an investment against its DI thesis. In certain cases, a qualitative adjustment was made for those investments at the border of categories.

- outperformed – 100% achievement against the respective DI thesis indicators

- on track – 50%-99% of the DI indicators are achieved

- marginally underperformed – 25-49.9%% of the DI indicators are achieved

- significantly underperformed – 0-24.9% of the DI indicators are achieved

- unclear – Investment was made after 2018; the nature of investment was not aligned with the development thesis or there was insufficient data to conclude on an outcome

Both direct and fund investments have been evaluated using similar indicators and in line with their respective formulated DI thesis. An increasing or decreasing trend in an indicator counts towards its achievement depending on whether a lower or higher number is considered better. Indicators will vary per investment depending on the DI thesis, relative importance and data availability. Indicators were also compared with market or competitor benchmarks where applicable and where data was available.

FIF fund performance is determined based on a simple average of the scores of the underlying investments with respect to their contributions to achieving the funds DI thesis. An illustrative example is shown on the next page.

Table 2: Fund performance example

| Investee | Performance against DI thesis | Assigned/average score |

|---|---|---|

| Investment A | Outperforming | 4 |

| Investment B | On track | 3 |

| Investment C | Marginally underperformed | 2 |

| Investment D | Significantly underperformed | 1 |

| Investment E | Unclear | NA |

| Overall Fund | On track | 2.5 (rounded to the nearest integer) |

The figure below showcases the performance of funds and investments against their respective DI thesis. Debt funds have been treated as single investments.

Figure 7: Overall performance against DI thesis

Note: All investments - this treats every investment on a standalone basis. Direct investments + funds - this treats fund investments as an average of the underlying investments it holds. This explains the difference between 84% and 78%.

From an individual investment perspective, CDC’s investments have done well with 78% of the portfolio having outperformed or on track (22% plus 56% above) to achieving the DI thesis across all relevant indicators.

When collectively looking at direct investments, MRPAs, debt funds and FIF funds (treating funds as individual investments that are scored based on an average of their underlying investee scores), 84% of CDC’s investments are either on track or outperforming (30% plus 54%). The remaining 16% are underperforming. This 84% is higher than 78% as underlying investments within a fund are aggregated to calculate the average score of a fund.

A breakdown of the portfolio-level performance through different perspectives is presented below, which aims to unpack any initial lessons.

Outperforming and ‘on track’ Investments

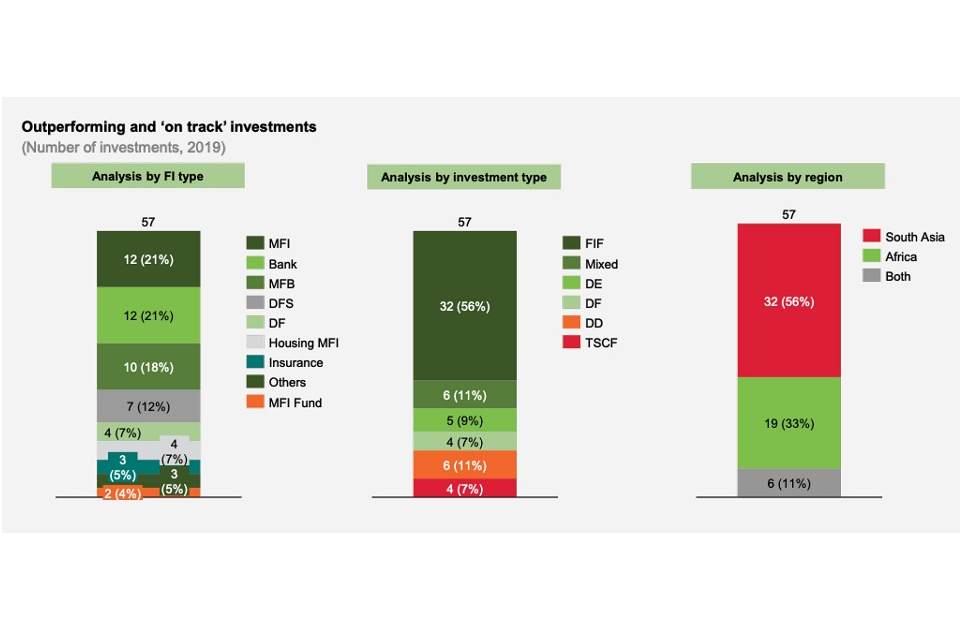

Figure 8: Analysis of outperforming and ‘on track’ investments

From an FI lens, microfinance institutions (MFI/MFB/MFI holding companies) have accounted for 43% of this category and commercial banks making up 21%.

Based on a product perspective, direct investments accounted for 31% of the number of investments[footnote 46] in this category (includes mixed investments, direct equity and direct debt). FIF fund investments made up 56% of this category. However, this reflects the fact that FIF fund investments make up the majority of the portfolio. From a regional perspective, South Asia made up 56% of the number of investments in this category with Africa making up 33%. Approximately 20% of the number of South Asian investments outperformed with 18% of African investments having done the same.

It is worth noting that 18 out of 24 direct investments fell within the category of ‘on-track investments’, accounting for 75% of all direct investments, while 59% of FIF fund investments fell within this category, with the equivalent proportions for debt funds and MRPAs at 75% and 57% respectively. This implies that overall, direct investments and debt funds have performed the best from a product perspective.

It is useful to note that 12 out of the 54 FI focused fund investments in this category exhibited some divergence between the achievement of DI and financial performance. While these investments are having an impact, their future survival and DI could be negatively affected.

‘Underperforming’ Investments[footnote 47]

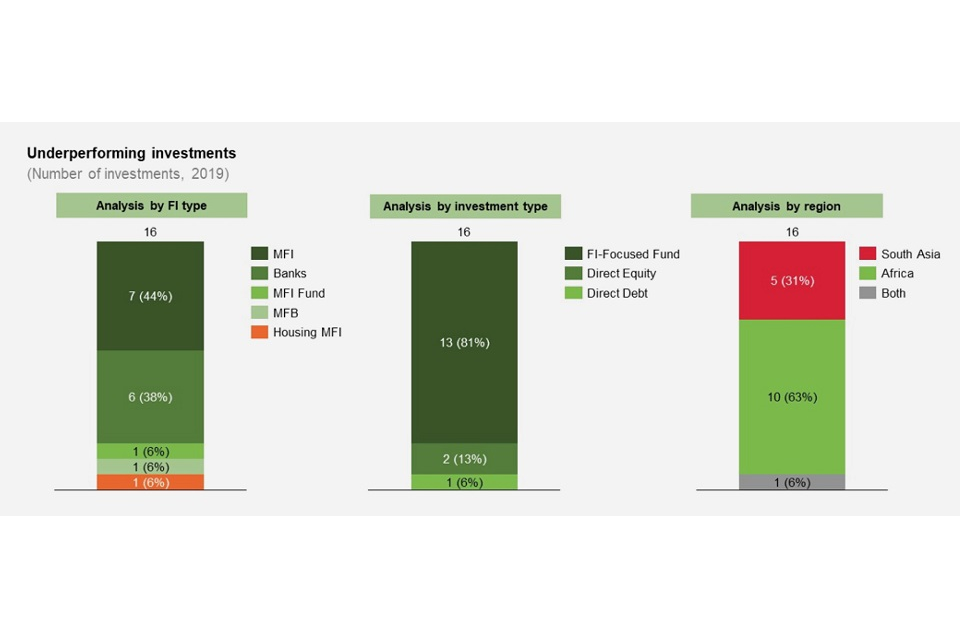

Figure 9: Analysis of underperforming investments

From an FI perspective and product perspective, MFIs and banks make up this entire category of underperforming investments, while FIF fund investments accounted for 81% of all the underperforming investments. However, this is largely driven by the portfolio structure of the FIF funds that primarily consists of banks and MFIs.

African investments made up 63% of this category – this may be a consequence of the fact that African economies are relatively more fragmented (simply due to their number) and less developed, and so African FIs are more susceptible to macroeconomic and operational risks. 14% of direct investments were underperforming, with 24% of FIF fund investments underperforming. The main reasons for poor performance within this investment category are detailed in Table 3 below. While 8 out of the 16 underperforming investments reviewed were loss making, it is not possible to conclusively say if there is a correlation between losses and relatively low DI. On the other hand, as noted above, 12 of the 54 outperforming FIF funds’ investees were also loss making. Three funds fall within this category, where 2 out of the 3 funds are Africa focused.

Table 3: Drivers of DI thesis achievement underperformance*

| Main factor driving poor performance | Number of investments |

|---|---|

| Operational/strategic factors | 7 |

| Macroeconomic factors | 4 |

| Business integrity factors | 3 |

| Regulatory factors | 2 |

Table 3: *[footnote 48]

Note: Operational/strategic factors have been used as a catch-all (general) category. Further analysis would be needed to conclude on the precise factors for poor performance within these FIs.

Half of the institutions underperformed as a result of operational inefficiency resulting mainly from a decline in loan asset quality that could be caused by serving underserved/relatively high-risk customers. However, based on the information at hand, this was not possible to verify. Four investments were adversely affected by macroeconomic factors within their respective countries, with 3 investments being adversely affected by business integrity failures[footnote 49]

Box 1: Understanding the impact of regulatory and macroeconomic factors on the performance of FIs

Aside from business integrity and operational issues, these factors were the main drivers for underperformance. This box explains how some of the main macroeconomic and regulatory factors impacted the performance of the FIs.

Interest rate caps in Kenya – 2016 In September 2016, the Government of Kenya passed a bill that capped interest rates chargeable by banks (excludes all other FIs) at no more than 4% above the base rate set by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). The cap was intended to address low affordability and availability of credit to working people and small businesses. While the cap lowered the cost of credit, it also encouraged banks to invest in government securities instead of lending to enterprises and consumers. The cap had a dampening impact on private sector credit growth as banks were unwilling to lend to relatively riskier segments at lower interest rates. The impact of the cap tended to affect smaller banks to a larger extent, as they pay a higher premium to source deposits and therefore need to lend at higher rates. Smaller banks faced the challenge of reduced, and in some cases negative, interest margins. The cap was repealed in September 2019. During the period the cap was in effect, banks became more cautious in their approach to lending.

Demonetisation in India - 2016 In 2016, India went through a demonetisation process that sought to replace the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes in an effort to flush out untaxed wealth. Based on the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) 2016 annual report 99.3% of the currency in circulation was returned to the RBI. The effects of the demonetisation were felt particularly by the MFI sector, which traditionally makes and receives payments in cash. The instalments on microfinance loans are collected on a weekly, fortnightly or monthly basis in small denominations. As small-cash denominations were unavailable following the demonetisation, borrowers were not in a position to service their loans, collections were delayed and dropped away, and MFI experienced an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs). While the demonetisation impacted most MFIs in India in 2017, most of them recovered soon after. Some MFIs were impacted more than others, driven by their respective regional, product and segment exposures. Overall, most MFIs in which CDC has invested are still on track to meet their DI thesis, as their financials were only impacted for a period of one year.

Andhra Pradesh crisis in India - 2010

The MFI sector in India was significantly affected by the Andhra Pradesh (AP) crisis of 2010. In 2010, at least a third of the 30 million households using some form of credit in India originated from AP. Reports of abusive practices by intermediary agents of private MFIs started making the news before any action was taken, initially in the vernacular press and subsequently the national media. Suicides in AP are often determined by agrarian trends and are unfortunately common. However, in this case over 70 suicides were alleged to be linked to people’s inability to repay MFIs. The state government cited these suicides as the basis for intervening to protect citizens from the unethical practices of private MFIs. The AP Microfinance Institutions (Regulation of Money Lending) Ordinance, 2010 was promulgated with effect from 15 October 2010 to address the MFIs’ coercive recovery practices. In the immediate aftermath of the ordinance, lending and recovery came to a halt. Politicians encouraged people not to pay back the MFIs. As a result, MFI collection rates fell dramatically (collection rates for organisations based in AP fell from 99% to 20%), and those clients who did not repay their loans became ineligible for future loans. Several MFIs that did not receive funding to restart operations ended up failing and exiting the market.

‘Unclear’ Investments There were 15 investments in this category; 9 investments were made in 2018 or later – their impact cannot be ascertained from the short investment horizon. Of the remaining investments, 3 investments were not aligned to the fund DI thesis and 3 investments were either exited in the same year of investment or due to insufficient data.

Note on performance While the majority (78%) of the overall portfolio is on track or has outperformed with respect to the DI thesis, it should be noted that this high performance is partly driven by a low hurdle prior to 2017 to measuring DI, i.e. some investments have relatively easier DI thesis to attain. Therefore, section 5 of this evaluation undertakes a thematic evaluation of performance to draw out weaknesses and potential areas for improvement when looking at DI. Therefore, any divergence of performance shown here and in section 5 of this evaluation is driven by the approach to looking at DI. Section 5 of this evaluation homes in on the areas for improvement, i.e. for those investments that are on track but not outperforming, e.g. investments that have grown their overall lending but have not managed to increase lending to specific segments and so on.

Trends in key CDC corporate, FI portfolio sector and development indicators

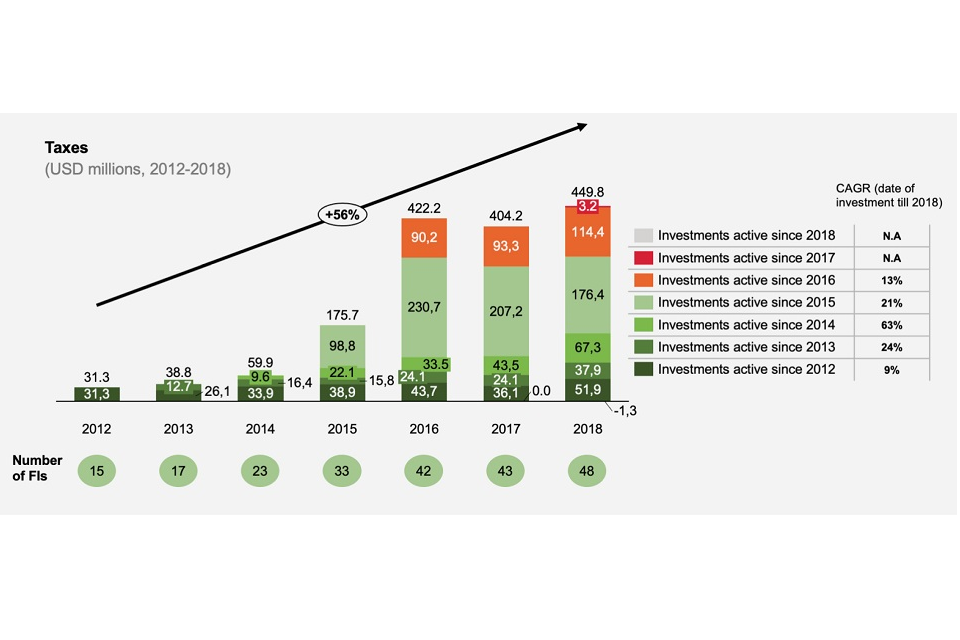

This section analyses CDC’s investment performance against key indicators to assess the extent to which FIs are delivering impact along CDC’s FI impact framework and against CDC’s development impact indicators. The key indicators under review are the following: total loans and advances, taxes, employees, female employees and the number of customers.

It should be noted that the results below look at the performance of the portfolio as a whole, rather than attributing performance to CDC. Currently within CDC there are efforts to begin applying an attribution approach whereby CDC’s impact can be estimated from the total portfolio impact. However, these methods are yet to be developed further for them to be applied. Attribution is an important approach to measuring impact as it allows one to strip out CDC’s role clearly. Further applications and enhancement of impact measurement methodologies within CDC would support the accurate measurement of impact going forward and should be actively pursued by CDC.

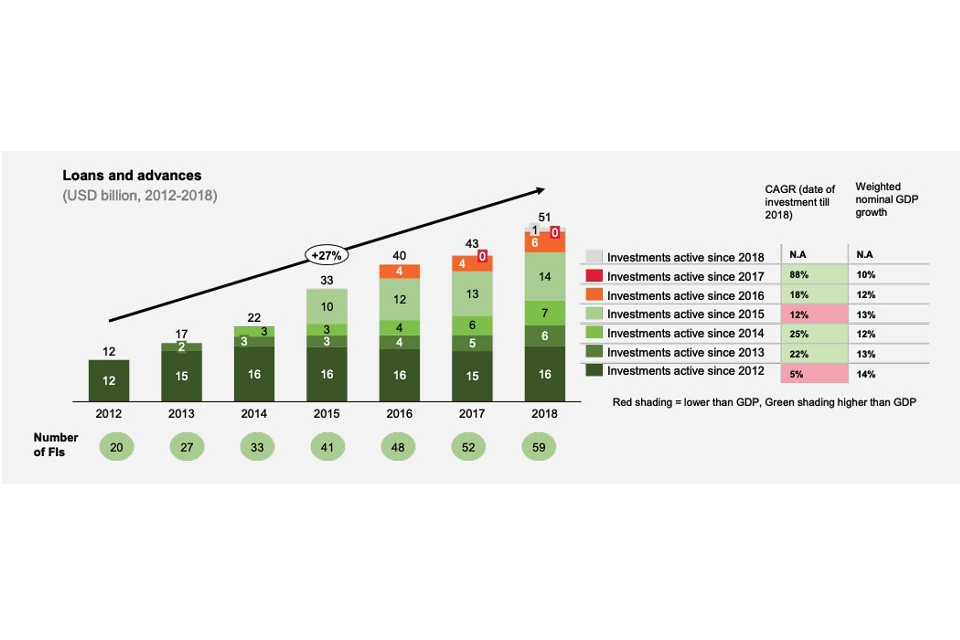

Total loans and advances

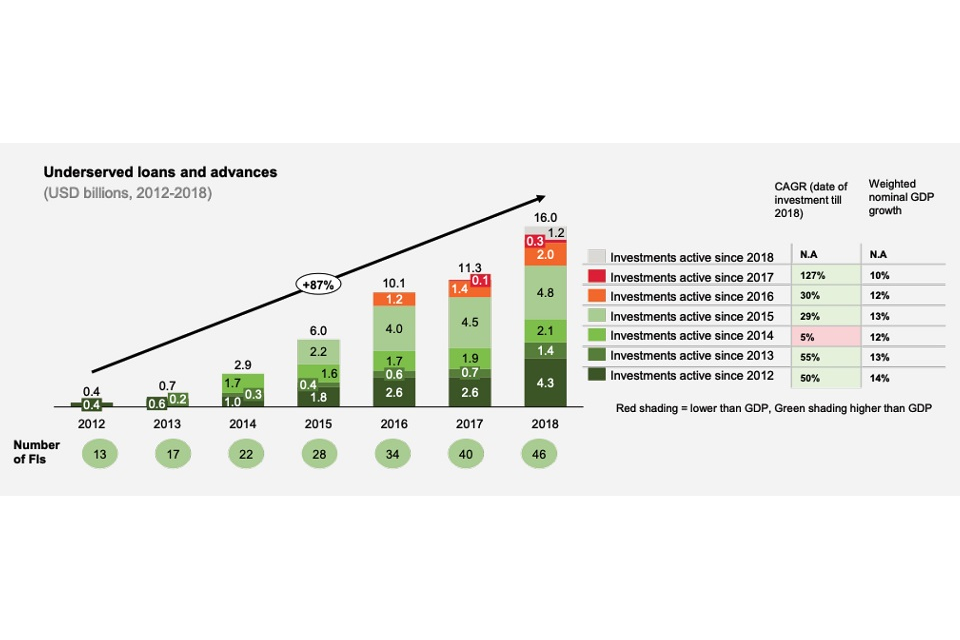

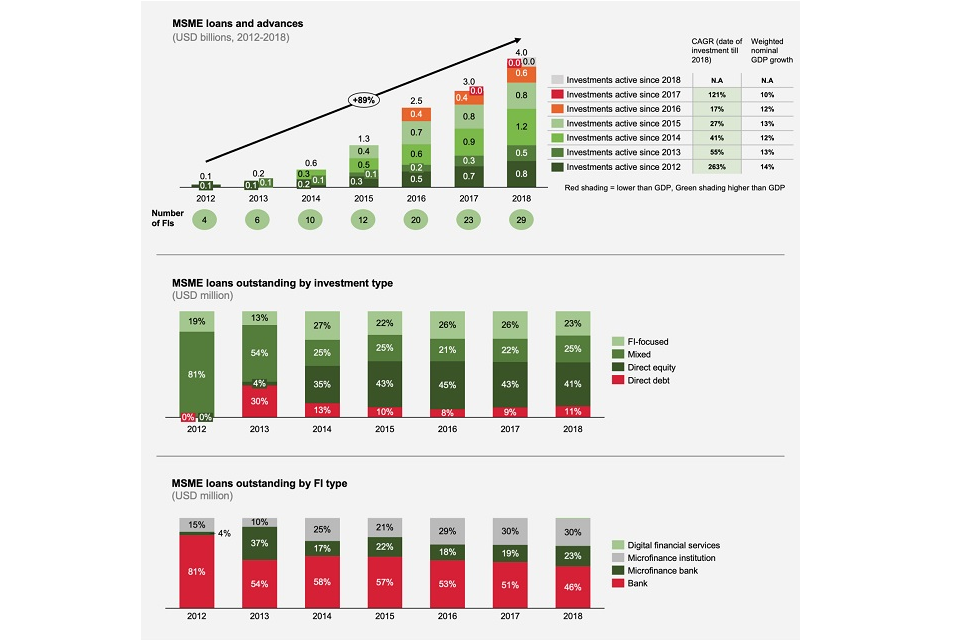

This sub-section analyses loan data of credit-providing institutions within the portfolio; 59 such investments from the portfolio were identified, with the remainder consisting of payment companies, TF investments, other non-lending companies and investments made in 2019 or later. The evolution of loans and advances in these institutions is highlighted below. This analysis is important as it provides an indication of how CDC’s funding has contributed to the growth of these FIs. In general, banks would be expected to grow even without any intervention on the part of CDC in line with GDP and therefore the analysis compares loan growth with GDP growth as a benchmark for success.

Figure 10: Portfolio total loans and advances outstanding*

Figure 10: *[footnote 50]

Note: Weighted nominal GDP growth calculated based on countries of all the investments assessed in this analysis

Overall, the portfolio has grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 27% from 2012 to 2018. Based on an organic growth analysis, the portfolio has in 4 out of 6 years grown faster than nominal GDP, implying that the sample analysed here has exceeded market growth on average. The subpar growth of 2012 and 2015 investments is largely driven by one indirect equity investment in a bank where growth has been marginally negative over this period and one direct bank investment which also experienced negative growth since 2015. The superior growth (albeit off a low base) of the investments made in 2017 is as a result of a housing MFI and a non-bank SME lender, both in India.

Notably, banks account for the largest portion of loans over the 2012-2018 period, accounting for 76% of loans as a consequence of their scale, despite being considerably fewer in number than MFIs.

Additionally, FIF fund investments have had the largest loan portfolios, as fund managers are able to invest in multiple large and small institutions.

It is worth noting that Africa has made up 58% of total loans. This is a consequence of the fact that African banks account for more than 80% of the number of investments in commercial banks within the portfolio.

Customers