100 Days Mission: First Implementation Report - HTML

Updated 7 December 2021

1OO DAYS MISSION

First Implementation Report

Reducing the impact of future pandemics by making Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Vaccines available within 100 days

An independent report on progress to G7 Leaders from G7 Chief Scientific Advisers

2nd December 2021

Mobilising the 100 Days Mission

Foreword

G7 Leaders welcomed the 100 Days Mission (100DM) at the June Carbis Bay Summit, and committed to working together, between sectors and across national borders, to deliver this ambitious Apollo mission. Leaders spoke of the unpredictability of future health emergencies and emphasised the need to harness scientific innovation and public-private collaboration to develop an armamentarium of diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines (DTVs) available within the first 100 days of a future pandemic threat being detected, consistent with our core principles around equitable access and high regulatory standards.

It’s on this commitment that we, as G7 countries and global science leaders, launched the 100DM and have since made early progress in mobilising the Mission, working with our G20 and wider international partners, the World Health Organization (WHO), the life sciences and biotechnology sectors, and international organisations. We have taken steps domestically and internationally to bolster political and scientific support for the 100DM, ensuring recommendations are reflected in our national policies and promulgated through public and private sector delivery plans. Innovation and collaboration have flourished in this environment and the results, although nascent, are particularly exciting.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank science colleagues and all 100DM implementation partners who have committed to this ambitious agenda and its concerted delivery over the next five years; the 100DM steering group members for their continued engagement; and lastly to Melinda French Gates and the wider Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for their support in developing the 100DM report, and their focus on putting equity at the heart of how we prepare for future pandemics.

This independent advisory report from Chief Scientific Advisers (CSAs), the first progress update since the summit, is encouraging but it demonstrates that there’s a long way to go. This is, therefore, a call to action for us as international science leaders, with our policy, industry, academic and philanthropic partners, and with the full backing of the G7 leaders, to make every effort to deliver this ambitious Mission.

The report contains proposed 100DM roadmaps which provide clear milestones over the coming year and out to 2026 to galvanise collective international action in pursuit of the Mission. In the year ahead, working with our international partners, we recommend the following are pursued as priorities:

i) securing global agreement on the priority virus families against which we should accelerate the development of prototype libraries of DTVs;

ii) applying innovations in ‘programmable’ vaccine and therapeutic platform technologies (e.g. mRNA, viral vector) to COVID-19 variants and to wider endemic diseases, including to support technology transfer and strengthen global manufacturing capacity;

iii) improving international coordination on clinical trials to enable an efficient approach to testing of DTVs, and harmonised and streamlined regulatoryprocesses; and

iv) embedding a mission-driven approach to global implementation, including by establishing a 100DM Science and Technology Expert Group and annual G7 CSA reviews: incentivising collaboration, mobilising investment and championing mutually beneficial public-private partnerships.

Our collective ambition as G7 CSAs is for the 100DM to be a sustained endeavour, initiated through the UK’s presidency and carried forward across futurepresidencies, with the wider international community, until the Mission isachieved. As we prepare to hand over the baton, it’s important to remind ourselves that the work to prepare the world for a future pandemic must be inclusive. We will ensure equitable access to DTVs is at the heart of our approach, for the benefit of all.

The 100 Days Mission is ambitious, but achievable and essential.

Sir Patrick Vallance

Chapter 1

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is the most devastating health and socioeconomic catastrophe of recent times and has caused untold damage. As of 24th November 2021 there were 257 million cumulative COVID-19 cases and 5.2 million COVID-19 related deaths worldwide.[footnote 1] In June 2020 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that the cumulative loss to the global economy over the years 2020 and 2021 are worth $12 trillion,[footnote 2] while in January this year The Economist estimated that forgone GDP over the same period is worth $10.3 trillion.[footnote 3]

As devastating as the current pandemic is, there is a reasonable likelihood that another serious pandemic could occur soon, possibly within the next decade.[footnote 4] The risk of a new pathogen emerging and becoming a threat is rising constantly as humanity expands into previously uninhabited regions and vulnerable populations.[footnote 5] We must, therefore, act now to strengthen our collective defences or risk being unprepared.

Seized by the gravity of the crisis, in February 2021 the UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, challenged G7 leaders to explore how to harness the unprecedented scientific innovation and public and private collaboration seen in the current crisis to reduce the time from discovery to deployment of diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines (DTVs) in future health crises, building on the target set by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).[footnote 6]

Under the leadership of Sir Patrick Vallance, the pandemic preparedness partnership was established as an independent group of international experts to advise the UK’s G7 Presidency on how to develop safe, effective and affordable DTVs within the first 100 days of a pandemic.[footnote 7] In June 2021, CEOs of life sciences and biotechnology companies leading the efforts to develop COVID-19 DTVs backed the ambition of the 100 Days Mission (100DM) set out by the pandemic preparedness partnership.[footnote 8]

Two weeks later at the Carbis Bay Summit, G7 Leaders welcomed the 100DM, emphasising the importance of science-led innovation, and invited G7 Chief Scientific Advisers (CSAs) or their equivalents to review progress and report to leaders before the end of the year. Leaders recognised that achieving the Mission required continued and concerted collaboration between the public and private sectors, within and beyond the G7, and a ‘no regrets’ approach to implementation.

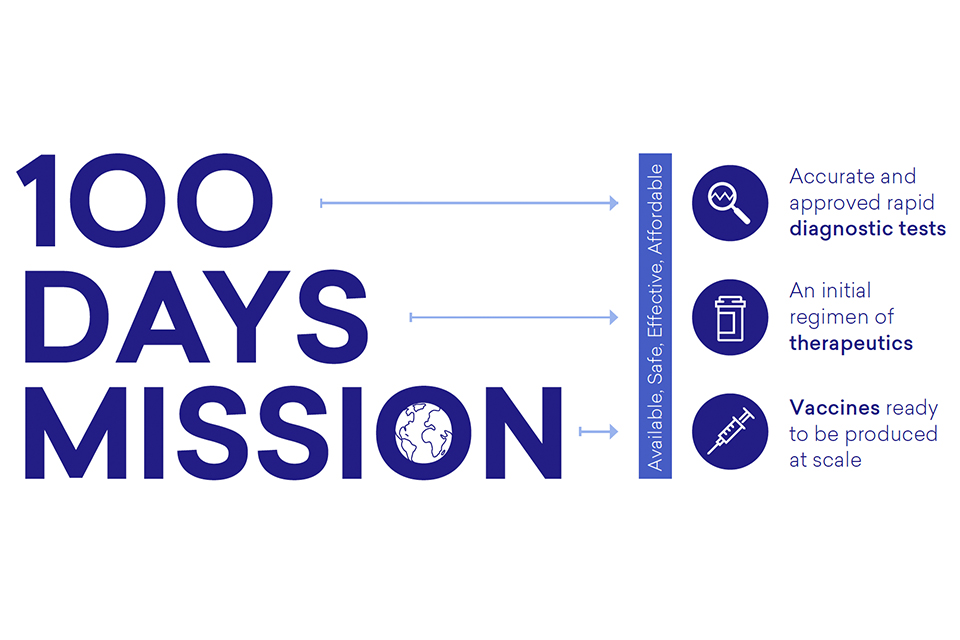

Leaders agreed that in the first 100 days from the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), we should aim for accurate and approved rapid diagnostic tests, an initial regimen of therapeutics and vaccines ready to be produced at scale for global deployment, ensuring equitable access for the benefit of all:

Diagram 1: The Mission

Approach to Implementation

The UK, as G7 President, has worked with G7 CSAs, the WHO and global 100DM implementing partners to mobilise delivery. We have taken a systematic approach to implementation, across three lines of engagement:

-

Broadening international political, institutional and scientific support for the Mission and its recommendations. Since the G7 summit, we have secured the support of the G20 to shorten the cycle for the development of safe and effective DTVs from 300 to 100 days following the identification of pandemic threats.[footnote 9] We continue to work closely with the WHO, in their strong normative, convening and coordination function across several recommendations. We are also working with low and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and wider international organisations to communicate and strengthen global cooperation across the 100DM recommendations and to advocate for science-based and equitable access to the solutions that arise.

-

Convening and mobilising organisations responsible for leading implementation of the specific 100DM recommendations, by setting clear expectations and timelines, aligning recommendations with existing policies, programmes and institutions wherever possible. For example, the UK Government CSA chaired a meeting of global life science and biotech industry leaders in November to review progress since the Life Sciences Event in June, develop the forward looking 100DM DTV roadmaps and agree key next steps for 2022.

-

Calling on G7 Governments to take concrete action domestically tobolster support for the 100DM by ensuring recommendations are considered in our national policies and taken forward in public and private sector delivery plans. For example in June, Japan embarked upon the “National Strategy for Vaccine Development and Manufacturing” as a national strategy for long-term continuous efforts to develop and manufacture vaccines for potential future pandemics. In September, the White House published the American Pandemic Preparedness Plan (AP3), enshrining the 100DM as a central tenet of its approach. Also in September, the European Union launched the European Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority[footnote 10] (HERA) to improve the EU’s readiness for health emergencies, including by supporting research and innovation for the development of new medical countermeasures. Germany launched a new Centre for Pandemic Vaccines and Therapeutics (ZEPAI) in October, to serve as a centre for pandemic preparedness, coordination and response in the future.

Chapter 2 of this report captures progress to date in implementing the 100DM, chapter 3 presents the forward looking DTV roadmaps, chapter 4 sets out the cross-cutting enablers of the Mission, and chapter 5 outlines a proposed future governance framework to drive implementation.

Diagram 2[footnote 11]

What Could Have Been: Comparing the COVID-19 Timeline to a Proposed 100 Days Mission Timeline

COVID-19 Timeline

In the COVID-19 timeline, it took 336 days from the point at which WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern to attaining one diagnostic test, therapeutic and vaccine against COVID-19. In the 100 Days Mission timeline, it will take 100 days from the point at which WHO declares a Public Health Emergency of International Concern to attain an aramanantarium of diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines against a future pandemic. The two timelines are represented below:

2014

-

-16 years

First clinical trial of an mRNA vaccine -

-5 years

WHO workshop on prioritisation of pathogens calls for R&D on MERS and SARS coronaviruses, among other diseases

2015

-

-4 years

Pre-fusion structure of a human coronavirus spike protein published

2016

-

-19 days

SARS-CoV-2 Sequence publicly shared

2020

- 0 days

WHO declares PHEIC -

64 Days

First real-time PCR test granted WHO EUL -

65 days

WHO report 1 million confirmed COVID-19 cases -

84 days

Launch of mRNA vaccine Phase 1/2 trial, 4 candidates evaluated in parallel -

85 days

ACT-A launched -

126 days

Gavi Global Vaccine Summit, launched and raised $505 million for COVAX AMC to support LMICs -

138 days

RECOVERY trial reports dexamethasone reduces mortality for those with severe disease -

167 days

150 countries in COVAX (75 self-financing) -

179 days

Phase 2/3 trial starts with selected mRNA vaccine candidate -

216 days

WHO approves dexamethasone as a COVID-19 therapeutic -

236 days

First Rapid Diagnostic Test granted WHO EUL -

259 days

SOLIDARITY Trial published interim results on therapeutics -

284 days

Phase 3 data show efficacy, will file for EUA once safety milestones met -

307 days

First SRA approval of vaccine (MHRA of Pfizer/BioNTech) -

336 days

WHO issued its first emergency use validation for a COVID-19 vaccine - 336 days

1 established example for each of diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines

2021

-

538 days

Partnership with Biovac to supply doses for Africa -

574 days

Partnership with Eurofarma to supply doses for Latin America -

601 days

FDA EUA for COVID-19 vaccine booster

100 Days Mission Timeline

Preparing for the 100 Days, Today

- Global epidemiological and genomic surveillance: continuous surveillance and established mechanisms for pathogen prioritisation and data sharing

- Fundamental research: ongoing research on pathogens and immunity

- Global regulatory harmonisation: streamline and harmonise regulatory processes, and establish emergency procedures

- Advance candidate vaccines and therapeutics for pathogens with epidemic or pandemic potential into early-stage clinical studies

- Establish the platforms and partnerships needed for R&D and clinical trials

- Build and sustain manufacturing capacity , kept warm through application of innovative technologies to endemic diseases

- Pathogens sequenced and shared globaly through integrated data and sample sharing mechanisms

The 100 Days Response

- 0 days

WHO declares PHEIC - Industry pivots existing programmes to address new target, leveraging past and new private and public investments

- Pandemic rules of the road take effect, facilitating sharing of samples and materials

- WHO and regulatory authorities issue guidance documents and target product profiles, including expectations for safety data

- Clinical trials of most promising candidates launched using clinical trial via regionally linked clinical trials networks

- Advance market commitments enable manufacturing at risk while clinical trials are ongoing

- Manufacturers rapidly expand production capacity, including through regional manufacturing hubs

- Safe and efficacious DTV achieve EUA

-

100 days

an armamentarium of DTV ready to be deployed, consisting of- Accurate and approved rapid diagnostic tests

- An initial regimen of therapeutics

- Vaccines ready to be produced at scale

Post – 100 Days Actions

- R&D improvements to thermostability and yields, enabling alternative routes of administration (e.g. nasal)

- Vaccines are evaluated for duration of protection, effectiveness against emerging variants, when used to boost immunity

Chapter 2

Progress Since Carbis Bay

The 100DM report made 25 actionable recommendations for governments, industry, philanthropic organisations, civil society and international organisations to take forward to achieve the Mission’s goals.[footnote 12] As set out in the June 2021 report, recommendations need to be underpinned by sustained financing ahead of a pandemic to enable implementation.

Key to improving global pandemic preparedness is effective surveillance coupled with pathogen analysis, so we can spot threats earlier and respond immediately. Once surveillance has spotted a disease risk, our best weapons are DTVs.

To prepare effectively we need to deliver against the following goals:

-

Invest in Research and Development (R&D) to fill the gaps in our arsenal: adopting a mission focused, public-private sector approach to prepare prototype DTVs to identify and treat pathogens of greatest pandemic potential, and to develop vaccines and therapeutic technologies that can be readily adapted and easily manufactured for an unknown diseases of pandemic potential, or ‘Disease X’.

-

Make the exceptional routine by embedding best practice between pandemics: including regionally and globally linked clinical trial networks, streamlined regulation and simplified transferable manufacturingprocesses (as the norm) ‘kept warm’ through global adult vaccination programmes.

-

Agree on the rules of the road for a pandemic: protocols formed as part of a wider suite of the WHO guidance, agreed in advance and demonstrating a step-change from business as usual when a PHEIC is declared.

Strengthening Global Surveillance

Achieving the 100DM and improving global pandemic preparedness requires, firstly, effective surveillance and pathogen analysis so we can spot pandemic threats earlier and respond immediately.

In early August, the WHO convened an Implementation Consultation Group (ICG) of 19 global experts to develop a conceptual approach for anInternational Pathogen Surveillance Network (IPSN). In line with Sir Jeremy Farrar’s Pathogen Surveillance Report,[footnote 13] the IPSN aims to bring genomic surveillance to speed and scale, so that it provides quality, timely and representative data within the broader surveillance architecture to better inform decision-making and public health action. Building on existing disease surveillance networks and based on expert inputs, the IPSN will rapidly undertake pilots to establish a ‘mesh network’ of pre-existing expert centres and active nodes. This will serve as the basis for the medium-to-long term strategic vision to span the molecular epidemiology needs for new and emerging threats, endemic diseases and other enduring public health challenges.

The WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence was established in Berlin to support the work of public health experts and policy-makers in all countries with the tools needed to forecast, detect and assess epidemic and pandemic risks so they can take rapid decisions to prevent and respond to future public health emergencies. The IPSN will build on the WHO Hub and other expert centres on pandemic and epidemic intelligence.

G7 partners have incorporated global surveillance considerations into national policies, building their domestic genomic capabilities:

-

The U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has established the National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance (NS3) system to track new variants of concern, alongside the Center for Epidemic Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics.

-

The UK Health Security Agency and the UK’s Centre for Pandemic Preparedness were launched[footnote 14] to spearhead the UK’s contribution to developing a global early warning system to detect new infectious disease threats, alongside the New Variant Assessment Platform (NVAP) offering UK capacity and expertise to detect and assess new variants of SARS-CoV-2. An extensive genomic sequencing and analytics capacity is already in operation.

-

Canada, through Genome Canada, launched the COVID-19 Genomics Network (CanCOGeN) for large-scale SARS-CoV-2 and human host sequencing to track viral origin, spread and evolution. The Network, supported by its research arm ‘the Coronaviruses Variants RapidResponse Network’ (CoVaRR-Net), is scaling up sequencing of COVID-19 viruses and will further contribute to building national capacity to address future outbreaks and pandemics.

-

France has established a national genomic surveillance network, through the Santé Publique France and ANRS Emerging Infectious Disease, with the short term objective of characterising, describing and monitoring the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants and the long term objective of a sequencing network in support of surveillance activities on emerging infectious diseases. The Pasteur network also has SARS-CoV-2 surveillance activities overseas and is currently proactively monitoring the emergence of new viral pathogens.[footnote 15]

-

The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) has launched the National COVID-19 genomic surveillance system to track and monitor variants in collaboration with local public health institutes, academic institutions and commercial laboratories, alongside building the genome sequencing capacity at the local government level.

Investing in R&D to Fill the Gaps in Our Arsenal

Demonstrable progress has been made in the R&D of DTVs for COVID-19 and endemic diseases.

-

CEPI is developing a ranking methodology to assess the likelihood of a ‘Disease X’ emerging from a family of viruses, and are sharing information with the US’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) who have developed their own approach to prioritisation. CEPI will work with the WHO (in its normative role) to agree the priority virus family list next year. This will determine the priorities against which prototype libraries of DTVs will be developed. CEPI will launch a call for proposals for pilot projects to develop vaccine libraries against two pilot virus families from the initial priority list, the Paramyxoviridae and Arenaviridae. CEPI is communicating closely with NIAID to ensure funding towards Disease X programmes are synergistic.

-

DeepMind has used its state-of-the-art AI system, AlphaFold, to generate protein structure predictions for 32 viruses curated by CEPI. These served as a starting point for discussing how AlphaFold might support the work of the 100DM in the discovery of targets for future DTVs. With the AlphaFold system now publicly available via open source code, DeepMind[footnote 16] is exploring with CEPI how it may play an advisory role to support structural virologists in making high-quality models for key targets. To increase AlphaFold’s relevance to vaccine development, further work will be needed to address certain limitations of the current system; these are areas of active research.

-

Industry and academia are adapting ‘programmable’ platformtechnologies,[footnote 17] (deployed during COVID-19), for use against wider endemic diseases. For example, Oxford University has started clinical trials of a plague vaccine using its viral vector technology[footnote 18] and Moderna is looking at using messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) technology to make vaccines against Nipah virus and HIV.[footnote 19] Pfizer has commenced a Phase 1 study of mRNA vaccine against influenza in healthy adults.[footnote 20] The WHO recently approved the world’s first vaccine against malaria which could prevent the deaths of 23,000 children each year in sub-Saharan Africa.[footnote 21]

-

Wellcome and CEPI are stimulating innovation in vaccine platform technology and manufacturing processes, including by co-funding the ‘Leap Programme’ for disruptive innovations in mRNA technologies.[footnote 22] The programme seeks to exponentially increase the number of biologic products that can be designed, developed, and produced every year, reducing their costs and increasing equitable access; and create a self-sustaining network of manufacturing facilities providing globally distributed, state-of-the-art surge capacity to meet future pandemic needs.

-

There have been several promising breakthroughs for therapeutics against COVID-19, including Merck & Co.’s oral antiviral molnupiravir, now approved by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which was shown to reduce the risk of hospitalisation or death in stage 3 trials.[footnote 23] Pfizer’s novel protease inhibitor paxlovid, when taken with the oral antiviral ritonavir, was shown to reduce the risk of hospitalisation or death by 89%, in a randomised study of non-hospitalised adult patients with COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe illness.[footnote 24] Both Merck & Co. and Pfizer have signed voluntary licensing agreements with the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) to help create broad access to oral antivirals.

-

The market for both antigen detecting rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) including lateral flow devices, and automated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests has expanded, with over 1,150 commercially available tests now on the market.[footnote 25] The average price of an RDT is falling, as industry has rapidly scaled up capacity and capabilities,[footnote 26] which is helping to create manufacturing capacity in, and provide increased access to LMICs. However, further work on regulatory approval is needed to expand access.

Work to strengthen the role of the international system in R&D capability and coordination for DTVs has also advanced:

-

CEPI’s Board has endorsed an approach to pursue activities related to therapeutics consistent with their current mandate, and will consider extending its mandate further to enable a broader scope of therapeutics’ efforts to be undertaken.

-

The Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) will strengthen international coordination and collaboration across the diagnostics ecosystem in pursuit of the 100DM, including supporting R&D to accelerate development of prototype diagnostics against priority virus families, and strengthen engagement with LMICs to improve access and promote uptake.

-

The International Readiness for Preventing Infectious Viral Disease Alliance (INTREPID) has recruited industry participants and formalised initial financial commitments to begin the rapid translation of promising academic discoveries onto an industrialised platform.

-

The Rapidly Emerging Antiviral Drug Development Initiative (READDI), in close collaboration with INTREPID and others, is developing small molecule antiviral drugs effective against priority virus families, as well as advancing clinical trials and manufacturing plans for rapid efficacy testing and production.

Embedding Best Practice Between Pandemics

There have been preliminary developments in the work to improve clinical trials and regulatory coordination, alignment and prioritisation:

-

The WHO recently convened a roundtable of globally diverse clinical trials experts[footnote 27] to agree collective actions to address the steps needed to make clinical trials more efficient, more effective and faster[footnote 28] so that DTVs are ready to be deployed within 100 days of a PHEIC. The WHO is scoping how an international network of regionally linked clinical trial mechanisms could be implemented, including optimisation of the infrastructure needed to support well designed and efficient trials and strengthening ethical and regulatory approvals processes.

-

The Good Clinical Trials Collaborative (GCTC) has developed streamlined guidance to support those involved in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to adopt flexible, innovative and proportionate approaches to trial design and delivery based on a set of key underlying principles for good RCTs.[footnote 29]

-

The MHRA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have established a working group within the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA) that will develop a pandemic preparedness protocol for regulators, reflecting best practice and lessons learned from COVID-19, to be published in 2023.

-

The MHRA and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Center for Devices and Radiological Health have committed to working with G7 counterparts to scope proposals to streamline diagnostics regulatory processes, prioritising the most impactful areas for mutual recognition agreements.

Global Manufacturing Capacity: Gavi, the WHO, CEPI and regional initiatives, supported by the G20,[footnote 30] are increasing vaccine distribution, administration and local manufacturing capacity in LMICs, including through technology transfer hubs in various regions. Development of this network will support enhanced access to DTVs, strengthening future preparedness and response. Individual companies are establishing extensive manufacturing capacity.

Rules of the Road

The procedures and protocols to come into effect in a future pandemic are being developed:

-

Data Access and Sharing: In response to the Science Academies of the Group of Seven’s (S7) statement on the “need for a better level of ‘data readiness’ for future health emergencies” the Global Pandemic Data Alliance (GPDA) has been established.[footnote 31] The GPDA has started work on a two-year implementation roadmap to meet the challenges set out by the S7 to ensure the availability and accessibility of data as a source for critical insights in public health emergencies.[footnote 32]

-

Biological Sample Collection and Sharing: The WHO BioHub System, if guided and ultimately approved by WHO Member States, could offer a mechanism for WHO Member States to voluntarily share biological materials with pandemic potential and must be designed to complement existing, functional systems such as the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). A few countries[footnote 33] have signed up to participate in the Pilot Testing Phase and the WHO will report on progress to the World Health Assembly following consultation with WHO Member States.

-

Finance and Health Governance: In October, G20 Health and Finance ministers committed to establishing a Joint Finance-Health Task Force to enhance dialogue and global cooperation on issues relating to pandemic prevention, preparedness and response (pandemic PPR). The Task Force will promote the exchange of experiences and best practice, develop coordination arrangements between Finance and Health Ministries, promote collective action, assess and address health emergencies with cross-border impact, and encourage effective stewardship of resources for pandemic PPR, while adopting a One Health approach.[footnote 34] In early 2022, the Task Force will report on modalities to establish a financial facility for ensuring adequate and sustained financing for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

-

Pandemic Governance: The Working Group for Strengthening WHO Preparedness and Response (WGPR) reached consensus to recommend that Member States move forward with an intergovernmental process to draft and negotiate a convention, agreement, or other international instrument on pandemic preparedness and response. WHO Member States will discuss this at the special session of the World Health Assembly in November 2021.

The Challenges Ahead

Pandemic Financing and Equitable Access: This pandemic has seen areliance by developing countries on grant funding and a stark asymmetry in access to DTVs. Multilateral efforts have sought to expand pandemic response coordination. The Multilateral Leaders Task Force (composed of major multilateral international organisations) is a good starting point in shining a light on the challenges that need to be addressed to remove barriers to export and import of DTVs and increasing production in developingcountries. Despite this effort, a key priority for 2022 will be mobilising sustainable sources of finance to support equitable access.

Chapter 3

Looking Ahead: Mission Roadmaps for DTVs

In the following chapter we outline forward looking roadmaps for delivering safe, effective and affordable DTVs ready for global deployment within 100 days. The indicative and iterative roadmaps set out the key outcomes we expect to see in 2026 and the milestones against which we can track and report progress annually. They were developed collaboratively with G7Governments, the Mission’s implementing partners, the WHO, and experts from around the world.[footnote 35] They will be evaluated and adjusted annually through the G7 CSA review to reflect advances in Science and Technology (S&T) and changes in the geopolitical, societal, environmental, legal and economic environment.

Diagnostics: The aim is to create prototype diagnostics against the priority virus families (agreed by CEPI and the WHO), with a focus on the respiratory viruses, using a growing diversity of platforms which can be readily adapted to a new pathogen. Normalising the use of accurate diagnostics in point-of-care, non-clinical settings (including for coronaviruses and influenza viruses) and within pathogen surveillance systems will stimulate investment and innovation in the sector. FIND, working with governments and the diagnostics industry, aims to reduce the price of a rapid test to under $1.00.[footnote 36] Integrating diagnostics into routine healthcare and pathogen surveillance systems will allow industry to develop high-quality diagnostics, and scale up manufacturing rapidly, when a new pathogen is detected.[footnote 37]

Therapeutics: The aim is to have 25 high-quality therapeutic candidates that have completed Phase 1 studies in humans, covering the high priority respiratory virus families.[footnote 38] Once a new pathogen emerges, these will be ready to be rapidly transitioned into Phase 2/3 trials, and manufactured at pace and scale.[footnote 39] The aim is to make monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) more affordable to LMICs, through reducing manufacturing complexity (supporting technology transfer) and streamlining regulatory pathways,[footnote 40] whilst also advancing programmable therapeutics[footnote 41] using the latest computational chemistry.[footnote 42]

Vaccines: The aim is to develop vaccine libraries against ten high priorityvirus families,[footnote 43],[footnote 44] which can then be readily adapted to a new pathogen. Investing in vaccine development for endemic diseases will stimulate innovation in novel platform technology and sustain capability to rapidly pivot to create vaccines against Disease X.[footnote 45] This will include R&D to increase the thermostability of vaccines and accelerate development of needle-free formulations, which will help enable large scale production, overcome deployment challenges and promote equitable access.[footnote 46] Industry, with the WHO, will strengthen existing manufacturing capacity in LMICs and build additional capability where required.

A critical first step in the development of prototype DTVs to prepare for a future Disease X is to determine an agreed list of priority virus families. The WHO will work with CEPI (alongside FIND, NIAID and INTREPID) to develop and agree a list of virus families against which development of prototype DTV libraries could be prioritised in early 2022. This list could also inform R&D funding decisions (e.g. governments, philanthropic, private sector) and efforts in industry and academia in pursuit of the 100DM.

Once research is underway to develop DTVs against priority pathogens, prioritisation of product development is critical. Our experience developing DTVs during COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of navigating the complex research landscape to inform expert scientific assessment of emerging products, conducted at an international level (e.g. by a panel of experts, under the authority of appropriate international organisations), so the most promising products are prioritised for testing and regulatory approval. Candidate treatments that meet the needs of the various patient populations, and of different health systems, should be prioritised and adapted to the designs and capacities of available platform trials. We recommend further work is conducted in early 2022 to progress this proposal, including identifying an appropriate joined up mechanism to ensure that the flow of products from different sources can be logged, monitored and prioritised.

Sustained R&D funding for development of DTVs is critical to achieve the Mission. Relying purely on current market incentives will be insufficient to act on the speed and scale needed to achieve the 100DM. Innovators need to be supported by incentive structures which align with the Mission, including strong and sustained public and private investment in R&D, fostering the level of certainty needed to stimulate rapid development of DTVs ready for global deployment within 100 days of a PHEIC. CEPI, through the replenishment event in March 2022, is seeking $3.5 billion investment from governments, global health organisations, and strategic partners to implement its five-year strategy to fund R&D to compress timelines and enable equitable access to lifesaving vaccines. Parallel investments to accelerate therapeutic and diagnostic development will be required to fill the gaps in our DTV arsenal and we recommend funding to stimulate R&D and innovation is consideredas part of any review of pandemic financing taken forward by the G20Finance-Health Task Force.

The ability to rapidly develop and deploy novel DTVs is dependent on a timely and systematic approach to data, information and biological sample sharing between industry, academia, international organisations, civil society and governments and strengthened public-private partnerships which build on those forged in the current pandemic.[footnote 47]

Over the next five years CEPI, alongside other key stakeholders including the WHO, will coordinate regular live fire exercises or ‘germ games’[footnote 48] to simulate the early warning phase and the first 100 days of a novel virus epidemic, where Day Zero marks the sequencing of the virus. The exercises will focus on the role of governments, in collaboration with key international organisations and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs), in developing safe, effective, available, and affordable DTVs that are ready to be produced at scale for global deployment. In the future these exercises could be extended to test the effectiveness of preparedness capabilities, including to assess collective resilience to potential future health threats.

Diagnostics Roadmap

Access to rapid, accurate diagnostic tests is critical to pathogen identification, interrupting transmission chains, and tracking and preventing the spread of a pathogen. In the COVID-19 pandemic, diagnostic developers were initially hindered in their efforts to create accurate tests due to slow access to samples, a lack of clear specifications, and insufficient regulatory harmonisation, which contributed to slow rollout in many jurisdictions.

The lack of investment in affordable, fast and accurate diagnostics before COVID-19, including point-of-care platforms capable of differentiating among pandemic threats like influenza and coronaviruses, resulted in limited research and production capacity which meant the market was underprepared.[footnote 49] Access to accurate tests in LMICs[footnote 50] and integration of diagnostics within surveillance networks[footnote 51] remain fundamental issues, alongside the need for thorough regulatory routes for diagnostics, including mutual recognition agreements between Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs), that better define criteria and standards for effectiveness, quality and use cases.

Intense collaboration between academia and industry[footnote 52] did yield significant advances, with automated PCR tests available in 64 days from the declaration of the SARS-CoV-2 PHEIC and the first RDT, not requiring extensive laboratory infrastructure, receiving WHO approval in 236 days. Private sector innovation and increased demand from governments is helping drive down the price of RDTs across the world. The average cost of a rapid test has dropped from $5.00 to $2.50 in just over a year, as industry has rapidly scaled up capacity and capabilities,[footnote 53] which is helping increase access to LMICs.[footnote 54]

Aims

By 2026, the aim is to have ‘accurate and approved rapid point-of-care diagnostic tests’ available within 100 days (ideally sooner) of a PHEIC being declared. This includes developing prototype diagnostic libraries on a range of test platforms (against priority virus families) that can be easily and quickly adapted to an emerging pathogen. Governments and international organisations will increase demand for diagnostics by normalising in point-of-care and non-clinical settings (including integrating into pathogen surveillance systems), thereby continuing to stimulate the private sector to innovate and strengthen manufacturing capacity, which will drive down prices for both PCR and RDTs around the world.

Summary Plans

Global Coordination: FIND is working with the WHO, the diagnostics industry and the WHO to strengthen international coordination on diagnostics R&D,[footnote 55] including in pursuit of the 100DM, and to support equitable access to diagnostics. In January 2022, FIND will submit a joint report with CEPI on diagnostics innovation for pandemics for the 100DM at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Following this they will convene meetings with key stakeholders and partners to refine a diagnostics plan and budget (ahead of the Annual Meetings of the World Bank Group and the IMF in Spring 2022) and kick-start implementation in Q2 2022.

Prototype Diagnostics: The diagnostics industry, coordinated by FIND, is developing diagnostic libraries using a diversity of platforms – both those that can detect pathogens across an entire virus family (e.g. pan-coronavirus) and ‘pathogen-agnostic’ platforms with the potential to detect Disease X.[footnote 56] They have launched a programme to develop several new point-of-care PCR platforms for differentiating multiple pathogens, the first of which should be commercially available in 2023.[footnote 57] The CEPI vaccine library approach will generate reagents and standards that can be used by others to rapidly develop diagnostics for pathogens with Disease X potential.

Normalising Diagnostics: Governments have a significant role to play in creating push incentives for diagnostics R&D and innovation, as well as pull incentives, by normalising the use of diagnostics in point-of-care and non-clinical settings. The U.S. Government aims to have affordable and accessible diagnostics ready to meet national needs for daily, at home, testing within weeks after the recognition of an emerging pandemic threat.[footnote 58] Japan has expanded its use of RDTs in both clinical and non-clinical settings and Canada has prioritised regulatory submissions of point-of-care COVID-19 tests, as well as convening an Advisory Panel to provide advice to support the pivot to testing in point-of-care and non-clinical settings. France is currently mainstreaming the use of duplex PCR tests (influenza, SARS-CoV-2) for the “at risk” population, although this is almost exclusively carried out in a hospital context.

Access to LMICs: FIND, working with industry and wider partners, aims to reduce the price of a rapid test to under $1.00[footnote 59] which will help achieve the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) target of minimum coverage of ‘100 tests / 100k people / day’ in LMICs over the next 12 months.[footnote 60] FIND will support the expansion of the manufacturing base in LMICs, and will work toward creating modular manufacturing processes, which are transferable and scalable, allowing for rapid production of key diagnostic tests.[footnote 61] The supply of accurate diagnostics needs to be matched by public sector demand to enable sustainable global production capacity at affordable prices.

Surveillance: Building on the conceptual approach of the IPSN, partners including FIND and the diagnostics industry will continue to work with the WHO to enhance diagnostics capability and capacity for global genomic surveillance. They will leverage current efforts by the ACT-A for SARS-CoV-2 sequencing and building capacity for key endemic diseases, such as arboviral diseases and antimicrobial resistant bacteria. This is part of the WHO’s Global Genomic Strategy that seeks to strengthen and scale genomic surveillance for quality, timely and appropriate public health actions within local to global surveillance systems.

Diagram 3

Proposed 100 Days Mission Roadmap for Diagnostics

Successfully achieving the milestones for the following recommendations will help us attain accurate and approved rapid diagnostics tests within 100 days

| 2022 Milestones |

2023 Milestones |

2024 Milestones |

2025 Milestones |

2026 Outcomes |

|

|

Recommendation 2 Build prototype diagnostic libraries applicable to representative pathogens of pandemic potential (FIND supported by CEPI, WHO and industry) |

WHO works with CEPI (alongside FIND) to agree priority virus families for accelerated development of prototype diagnostic libraries. FIND, working with industry and academia, identifies two or more fit-for-purpose molecular (PCR) platforms for near-patient testing for multiple pathogens. |

FIND demonstrates progress in developing prototype libraries for detection of four priority list virus families (Coronavirusae, Orthomyxoviridae, Filovirusae and Flaviviridae). FIND advances at least two PCR platforms and establishes target supply chain for regional production of PCR and antigen rapid tests (RDTs). |

FIND matures prototype diagnostic libraries for four priority virus families. Adds additional virus families for development (decided in conjunction with CEPI and WHO based on surveillance data). FIND secures regional supply chains for 100DM response for PCR and antigen RDTs. FIND demonstrates effective prototype library stand-up in ‘germ games’. |

FIND matures diagnostic libraries across further four - six families of viruses including Paramyxoviridae, Bunyaviridae, Togaviridae and Flaviviridae, subject to funding. FIND demonstrates effective pathogen-agnostic platforms with the potential to detect Disease X. |

Prototype diagnostics developed providing broad coverage for 8-10* virus families. *final number subject to funding |

|

Recommendation 6 Strengthen the role of the international system in R&D capability and coordination for diagnostics (CEPI, FIND, WHO with academia and industry) |

FIND and CEPI to create a ‘contract mechanism’ for FIND to coordinate diagnostics work on the 100DM. FIND present strategy (alongside CEPI) to WEF, highlighting the fundamental role of academia and industry in diagnostic innovation for 100DM. FIND convene industry to work with WHO and SRAs to drive improvements in regulation, clinical trials and manufacturing for diagnostics. |

FIND, working with academia and industry, CEPI and the WHO begin implementing diagnostics strategy for 100DM. Partnerships formed across diagnostics sector and governments in both HICs and LMICs. FIND demonstrate improvement in global diagnostics coordination, including facilitating knowledge exchange and collaboration on 100DM. |

FIND, working with academia and industry, reports progress in developing partnerships across diagnostic sector and with governments to stimulate innovation and take up of diagnostics (see Rec 7). FIND works with partners (SRA, WHO, Industry) to drive improvements in standards, clinical trials, regulation and manufacturing / supply chain for diagnostics. |

FIND reports progress in developing partnerships across diagnostic sector and with governments to stimulate innovation and take up of diagnostics (see Rec 7). FIND works with partners (SRA, WHO, Industry) to drive improvements in standards, clinical trials, regulation and manufacturing / supply chain for diagnostics. |

Strengthened international coordination between governments, industry and international organisations on diagnostics R&D. |

|

Recommendation 7 Governments should normalise the use of accurate diagnostics for coronavirus and influenza in point-of-care and non-clinical settings (G7 Govts, FIND, WHO, academia and industry) |

G7 governments, working with FIND and WHO, produce plans to normalise the use of diagnostics domestically, including annual milestones. |

G7 governments, with FIND and WHO, develop implementation plan to normalise use of diagnostics and promote adoption via G20 and LMICs. | G7 governments, with FIND and WHO, implement plan to normalise use of diagnostics and promote adoption via G20 and LMICs. | G7 governments, with FIND and WHO, implement plan to normalise use of diagnostics and promote adoption via G20 and LMICs. | Diagnostics used routinely in point-of-care and non-clinical settings for priority pathogens. |

|

Recommendation 8 WHO should support an enhanced role for diagnostics in the surveillance of pandemic threats (WHO) |

WHO establish pilots for the International Pathogen Surveillance Network, which will serve as the basis of a rapid establishment of a ‘beta version’. WHO will report on the utilisation of the IPSN conceptual approach to strengthen genomic surveillance of pandemic threats before April 2022. |

A stepwise process is being used to develop and inform the conceptual approach, and to provide options for IPSN implementation. Future milestones will be determined in consultation with G7 CSAs and in line with the IPSN report due April 2022. |

A stepwise process is being used to develop and inform the conceptual approach, and to provide options for IPSN implementation. Future milestones will be determined in consultation with G7 CSAs and in line with the IPSN report due April 2022. |

A stepwise process is being used to develop and inform the conceptual approach, and to provide options for IPSN implementation. Future milestones will be determined in consultation with G7 CSAs and in line with the IPSN report due April 2022. |

Diagnostics integrated into the International Pathogen Surveillance Network (IPSN) to maximise its coverage and utility. |

Therapeutics Roadmap

Therapeutics are vital for treating infections, reducing morbidity and mortality, as well as mitigating the long-term damage to people’s health. Therapeutics can also be used as prophylaxis, to prevent symptoms and the spread of the disease in community settings, easing pressure on hospitals. Vaccines will not work against every pathogen, therefore having an initial regimen of high-quality therapeutics ready to go is vital in strengthening pandemic preparedness.

Despite warnings from scientists that a ‘stockpile’ of broad-spectrum ‘Phase 2-ready’ antivirals would be essential to respond to future outbreaks,[footnote 62] there were no approved antivirals for coronaviruses prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.[footnote 63] Notable successes early in the COVID-19 pandemic were as a result of repurposed drugs, such as dexamethasone, which have since saved countless lives.[footnote 64] There are now eleven approved repurposed antiviral drugs for treating COVID-19 globally and, while many antivirals specific to COVID-19 remain in preclinical development,[footnote 65] there are promising signs of significant breakthroughs, such as molnupiravir[footnote 66] and paxlovid.[footnote 67]

To date, at least six mAbs have been granted emergency use authorisation, with another five in late stage development.[footnote 68] The first generation of approved mAbs products[footnote 69] require high doses delivered by injection or infusion, which increases the cost of production and delivery and adds to the burden on health care systems which are already stretched. mAbs hold challenges for local manufacturing because they require highly specialised facilities, need to be adapted on an ongoing basis for new variants,[footnote 70] which results in limited supply and high prices.[footnote 71] Producers are currently insufficiently incentivised to invest in manufacturing innovations, and there is inadequate global capacity to produce mAbs at scale. These challenges must be addressed to increase access to mAbs to combat future health threats.

Aims

To rapidly prepare ‘an initial regimen of therapeutics’ against a future Disease X, we need to move from reactive response to proactive planning.[footnote 72] By 2026, the aim is to have 25 high-quality small molecule antiviral candidates which have completed Phase 1 studies in humans, developed against the high priorityvirus families.[footnote 73] These will be ready to be rapidly transitioned into phase 2/3 trials, and manufactured at pace and scale.[footnote 74] The aim is to make ‘programmable’ mAbs more affordable to LMICs by reducing complexity in administration, simplifying manufacturing processes, expanding manufacturing capacity and streamlining regulatory pathways.[footnote 75]

This will be underpinned through strengthened international coordination on therapeutics R&D, bringing together different initiatives, creating an enhanced end-to-end pipeline for small molecule antivirals and ‘programmable’ mAbs to truncate development timelines and promote equitable access. CEPI will work as a connector to ensure a coordinated approach, working closely with industry (including public-private product development partnerships already focused on therapeutics), through INTREPID, and READDI along with INGOs and wider stakeholders.

Summary Plans

Global Collaboration: A priority for 2022 is to create a forum to bring together complementary therapeutics initiatives to share information and reduce duplication. The specific remit of this forum is yet to be scoped, but CEPI – working with partners such as the Hever Group, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), Wellcome, the International Federation ofPharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA), and INTREPID – will play a key role as a convener, as well as contributing to evidence generation and tracking of novel and repurposed therapeutics. Such a therapeutics forum could provide an avenue for interested parties to share pre-competitive information (such as in silico predictions and animal models data analysis).

Developing Phase 1 Antivirals: Industry is working to develop 25high-quality small molecule antiviral candidates. INTREPID, an emerging industry-led consortium, seeks to accelerate this process through enhanced pre-competitive collaboration and jointly agreed targets (initially focused on an expanded panel of coronavirus targets). By the end of 2022, industry aims to develop ten high-quality antiviral candidates against priority virus families. READDI,[footnote 76] a public-private partnership, is developing five broad spectrumsmall molecule antiviral drugs, focusing initially on the Coronaviruses, Flaviviruses and Alphaviruses. Creating stockpiles of therapeutics against priority virus families should be considered. This would stimulate innovation, keep manufacturing warm and enable rapid containment of outbreaks of known pathogens.

Preparing Clinical Trial and Manufacturing Plans: READDI will form partnerships with manufacturers, and develop Phase 2/3 trial designs for antiviral candidates in advance of future viruses emerging.[footnote 77] This includes establishing “warm base” manufacturing plans to enable rapid scale up and distribution of small molecule antivirals around the world. READDI will also plan Phase 2/3 trials at pre-identified sites around the world for rapid efficacy testing in multiple patient populations. Other global partners, including the Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GLoPID-R), will also play a key role in coordinating platform trials.

Reducing Cost of mAbs: Increasing access to mAbs will requireimprovements in deliverability and scale of production.[footnote 78] Working with the proposed therapeutics forum and existing public-private partnerships, industry will invest in manufacturing innovations for developing accessible mAbs, such as improving thermostability,[footnote 79] developing alternative routes of administration,[footnote 80] and reducing the size and/or number of doses: all of which would significantly reduce the costs for producers and the manufacturing capacity required for increased equitable access.[footnote 81] Strategies which target upstream productivity, such as continuous processing and alternative microbial hosts,[footnote 82] are likely to have the greatest impact on lowering costs.[footnote 83] Once established, integrating manufacturing innovations as new platform processes for new facilities, as well as retrofitting existing infrastructure, will ensure these innovations are widely adopted and lead to increased access to mAbs.

Alternative Therapeutic Modalities: mAbs may not be the most accessible therapeutic modality in some settings, therefore the development of other therapeutics modalities is essential. Several initiatives are exploring the possibilities of RNA based therapeutics[footnote 84] which could be a valuable tool in pandemic response, if issues around delivery to the tissue and cell type are addressed.[footnote 85] Targeting of gene expression through RNA interference (RNAi) is being developed as a new therapeutic strategy, has been proven for several conditions and there are licensed medicines available. Whilst it holds significant promise, there are a number of technical issues to be overcome for treating infections.

Diagram 4

Proposed 100 Days Mission Roadmap for Therapeutics

Successfully achieving the milestones for the following recommendations will help us attain an initial regime of therapeutics within 100 days

| 2022 Milestones |

2023 Milestones |

2024 Milestones |

2025 Milestones |

2026 Outcomes |

|

|

Recommendation 3 Develop prototype antiviral therapeutics, including antibody therapies, for respiratory pathogens of pandemic potential. (Research-based pharmaceutical industry initiatives such as READDI and INTREPID) |

WHO works with CEPI (alongside INTREPID) to develop priority virus families for accelerated development of prototype antivirals. Industry, working with INTREPID, agrees priority viral families for antiviral development and testing. Initiates development of ten high-quality antiviral candidates (small molecule antivirals). READDI launches broad spectrum antiviral discovery efforts for multiple priority virus families. |

Industry, working with INTREPID and wider partners, develops 20 antiviral candidates, against the agreed priorities. READDI advances lead antiviral compounds into preclinical testing. |

Industry, working with INTREPID and wider partners, develops 25 antiviral candidates against the agreed priorities. READDI, with INTREPID and industry and other partners, launch late stage preclinical and early clinical development and establishes clinical trial plans. |

Industry, working with INTREPID, and wider partners, develops 25 antiviral candidates, which have advanced to Phase 1 testing in humans, against the agreed priority pathogen list. READDI, with INTREPID and industry and other partners, identify small molecule antiviral candidates to advance through Phrase 1 testing, and develops Phase 2/3 clinical trial plans. |

25 high-quality therapeutic candidates developed against priority (respiratory) virus families. |

|

Recommendation 5 Invest in simplified cheaper routes for producing monoclonal antibodies and other new therapeutic modalities (G7 Govts, Industry (IFPMA)) |

Working with the proposed therapeutics forum, industry (with partners) targets investment to develop: i. mAbs – to enable smaller or less frequent doses, improve thermostability, routes of administration and pursue manufacturing innovation. ii. Novel programmable antivirals (including new approaches e.g. siRNA, stapled peptides or inferring inhibitors) against future Disease X. |

Industry, working with the proposed therapeutics forum, targets investment to address mAbs deployability challenges. Industry (with partners)>develops programmable antiviral platform technology (including new approaches) to address priority endemic diseases. | mAbs demonstrate improved thermostability and administration, with smaller or less frequent doses for the same treatment. Innovations contribute to reducing average cost of producing marketable mAbs to less than $75/gram. Programmable antiviral platform technologies developed against priority endemic diseases, proving efficacy. |

mAbs demonstrate improved thermostability and administration, with smaller or less frequent doses for the same treatment. Innovations contribute to reducing average cost of producing marketable mAbs to less than $50/gram. Programmable antiviral platform technologies developed against wider endemic diseases, proving efficacy. |

Cost of producing marketable mAbs reduced to less than $25/gram.a Programmable antivirals available, able to be rapidly re-purposed to Disease X. |

|

Recommendation 6 Strengthen the role of the international system in R&D capability and coordination for therapeutics by expanding CEPI’s remit to cover therapeutics, (CEPI with funding support from G7 Govts). |

INTREPID, READDI, the Hever Group, Wellcome, BMGF, CEPI and other key stakeholders agree a therapeutics forum to share information and reduce duplication of efforts. CEPI sets out its strategic objectives and investment plan for therapeutics. |

Future milestones will be agreed by the proposed therapeutics forum and reported by CEPI in 2022. INTREPID works with key industry partners to enable the rapid translation of promising academic discoveries onto industrialised platforms. |

Future milestones will be agreed by the proposed therapeutics forum and reported by CEPI in 2022. INTREPID works with key industry partners to enable the rapid translation of promising academic discoveries onto industrialised platforms. |

Future milestones will be agreed by the proposed therapeutics forum and reported by CEPI in 2022. INTREPID works with key industry partners to enable the rapid translation of promising academic discoveries onto industrialised platforms. |

A sustainable R&D ecosystem and improved international coordination and funding for therapeutics R&D. |

| a. The cost of producing monoclonal antibodies is currently estimated to be ~$100/gram, per Stamatis, C. and Farid, S.S. (2021). Process economics evaluation of call-free synthesis for the commercial manufacture of antibody drug conjugates. Biotechnology Journal, 16(4), p.2000238. Included within gram measurement are both the bulk drug substance and the final drug product, per Wellcome (2020). Expanding access to monoclonal antibodies. [online] Wellcome. Available at: https://wellcome.org/reports/expanding-access-monoclonal-antibodies. |

Vaccines Roadmap

Vaccines against COVID-19 have been developed and deployed in record time in this pandemic.[footnote 86] As of 24th November 2021, 7.78 billion doses have been administered globally, and 28.26 million are now administered each day.[footnote 87] This incredible success was the result of years of ongoing research on prototype vaccines against other coronaviruses, including those that cause Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which began after the SARS outbreak in 2003.[footnote 88] This resulted in an unprecedented level of investment in early 2020[footnote 89] which allowed companies to run multiple trials in parallel and manufacture vaccines at risk,[footnote 90] and regulators moving at unprecedented speed.[footnote 91]

Recently developed ‘programmable’ vaccine platforms,[footnote 92] such as viral vector and mRNA,[footnote 93] have transformed the vaccine landscape because of their versatility, high potency, capacity for rapid development and potential for low-cost manufacture and safe administration.[footnote 94] These technologies also have the potential to be manufactured rapidly at scale[footnote 95] and remove the need to build new manufacturing facilities for vaccines developed against different diseases.[footnote 96] A facility dedicated to mRNA production can rapidly manufacture vaccines against multiple targets, with minimal adaptation to processes and formulation.[footnote 97]

The WHO estimates that up to 50% of all vaccines (although considerably less for COVID-19 vaccines due to demand) may be wasted globally every year because of lower than anticipated demand, temperature control, logistics and shipment-related issues.[footnote 98] Improving the stability of new ‘programmable’ platforms, and reducing the need for needle and syringe, offers a chance to reduce the pressure on healthcare systems and increase speed and scale of global distribution and access.[footnote 99]

We may learn more about vaccines this year alone than in previous decades combined, because of the detailed information collected on clinical volunteer demographics and humoral and cellular responses.[footnote 100] Rapid advances in structural biology[footnote 101] and artificial intelligence[footnote 102] (including protein structure predictions) have the potential to significantly accelerate timelines for identifying targets for diagnostic, vaccine and drug discovery, towards our goal of having vaccines ready to be produced at scale for global deployment within 100 days of the WHO declaring a PHEIC. In January 2022, CEPI and McKinsey will publish a report outlining lessons learned on vaccines from COVID-19, focusing on how we can truncate approval timelines for vaccines without compromising on safety. The report will also outline the current global landscape of vaccine platform technology, highlighting key opportunities for future investments.

Aims

-By 2026, the aim is to have developed libraries of prototype vaccines against priority virus families[footnote 103] and advanced platform technology, such that it can rapidly pivot to a future Disease X. This investment will also be targeted towards increasing the stability of vaccine platforms to enable large scale production of thermostable vaccines, as well as R&D to accelerate development of alternative routes of administration which will help overcome the logistical challenges and promote equitable access.[footnote 104],[footnote 105] Vaccine manufacturing capacity will be expanded to match the demand to COVID-19 vaccines, and kept “warm” to maintain capabilities able to pivot in response to a future pandemic.

Summary Plans

Prototype Vaccines: CEPI is developing libraries of prototype vaccines against ten high priority virus families, based on novel computational antigen designs and using rapid response platforms that can be quickly adapted if related viruses emerge.[footnote 106] CEPI will conduct extensive preclinical and clinical (Phase 1) testing of a subset of vaccines within each virus family to develop the regulatory support and ability to rapidly deploy a vaccine when a new pathogen emerges. In 2022, they will begin two pilot projects to create vaccine libraries against two high priority virus families, the Paramyxoviruses and Arenaviruses. Development of candidate vaccine libraries will provide industry with the starting materials for vaccine development against a new pathogen, as well as the critical assay reagents and manufacturability data generated through this work.

Platform Technology: Investments into prototype vaccine libraries will accelerate wider industry research into vaccines against endemic diseases.[footnote 107] By 2026, CEPI aims to have supported the development of licenced vaccines against two endemic diseases (current programmes are focused on Nipah, Lassa fever and chikungunya viruses). In addition to preventing serious illness and death from endemic diseases, this research will advance existing platform technology, which can be used to rapidly develop vaccines against a new pathogen. Industry and academia continue to advance platform technology through creating vaccines against COVID-19 and known endemic diseases, proving efficacy in humans (where possible). Vaccine seed stocks and batch versions of primary or variant Virus-like particles[footnote 108] should be produced to contain outbreaks of known pathogens. This would also create demand to keep manufacturing facilities “warm” beyond the current pandemic.

Reduce Complexity: Vaccine manufacturers are investing in reducing the complexity of the manufacturing process of these new platforms to enable large scale production. Pfizer and BioNTech have initiated a Phase 3 study evaluating a lyophilised (freeze-dried) formulation of their COVID-19 vaccine designed to be refrigerator-stable.[footnote 109] Similarly, Moderna and CureVac (with GlaxoSmithKline) continue to explore mechanisms that could produce more thermostable mRNA vaccines, removing the need for ultra cold chain storage for the mRNA platform.[footnote 110] A recent discovery of ionizable adamantane-based Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), a new type of nanoparticles that are capable of transporting nucleic acids of varying lengths into cells, could be transformational.[footnote 111] These efforts are complemented by academic and biotech companies’ research into how to make the RNA structure itself more stable.

Alternative Routes of Administration: Breakthroughs witnessed in injectable vaccines have not yet translated to licenced needle free vaccines. Proving the vaccine efficacy of needle-free formulations (oral, intranasal, thinfilm) should be the priority for R&D moving forward, including to understand correlates of protection and measure immune responses, but will require sustained investments from governments and industry. Using novel technologies to deliver influenza vaccines in clinical efficacy studies may provide the fastest route to determining vaccine efficacy in humans, and multiple technologies could be compared in one large trial. Currently, there are 13 (four oral and nine intranasal) needle free vaccines in clinical trials, with many more in pre-clinical trials. Should these trials prove successful, it could transform the global distribution of vaccines in a pandemic.[footnote 112]

Manufacturing: Gavi, the WHO, CEPI and regional initiatives, supported by the G20,[footnote 113] are increasing vaccine distribution, administration and local manufacturing capacity in LMICs, including through technology transfer hubs in various regions. The Partnership for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) is leading the establishment of a new mRNA hub in South Africa and the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) is coordinating the development of hubs in Argentina and Brazil. The WHO is due to launch an Expression of Interest for hubs specialising in viral vector vaccines in 2022. BioNTech announced in August that it was looking to establish malaria and tuberculosis vaccine production sites using mRNA technology in Rwanda and Senegal. [footnote 114] Similarly, in October, Moderna announced plans to invest up to $500 million to build a factory in Africa to make up to 500 million doses of mRNA vaccines annually.[footnote 115] The challenge ahead will be to ensure this manufacturing capacity stays “warm” post the current pandemic, and is embedded as business as usual practice through expanding vaccination programmes around the world.

Diagram 5

Proposed 100 Days Mission Roadmap for Vaccines

Successfully achieving the milestones for the following recommendations will mean vaccines are ready to be produced at scale for global deployment within 100 days

| 2022 Milestones |

2023 Milestones |

2024 Milestones |

2025 Milestones |

2026 Outcomes |

|

|

Recommendation 2 Build prototype vaccine libraries applicable to representative pathogens of pandemic potential. (CEPI) |

WHO works with CEPI (alongside NIAID) to develop and agree priority virus families for accelerated development of prototype vaccine libraries. CEPI conducts annual ‘germ games’ to test preparedness to future Disease X. CEPI begins two pilot (discovery) projects to create vaccine libraries against two high priority virus families (Arenaviridae and Paramyxoviruses). |

CEPI conducts annual ‘germ games’ to inform international preparedness plans for future Disease X. CEPI stimulates (academic and industry) R&D to develop candidate vaccine libraries for two virus families (Arenaviridae and Paramyxoviruses) to preclinical phase and commences discovery of vaccines against further virus families. |

CEPI conducts annual ‘germ games’ to inform international preparedness plans for future Disease X. CEPI supports preclinical testing of subset of initial vaccine library and progresses development of further candidates to preclinical phase. |

CEPI conducts annual ‘germ games’ to inform international preparedness plans for future Disease X. CEPI supports clinical testing of subset of initial vaccines library and conducts preclinical testing of further vaccines to preclinical phase. |

Prototype vaccines libraries developed for ten high priority virus families. |

|

Recommendation 4 Invest in modernising vaccine technology by targeting vaccine preventable diseases. (Industry (IFPMA), academia, CEPI, Gavi) |

CEPI (with McKinsey) catalogues advances in platform technology and (with Wellcome) invests in disruptive innovations to improve vaccine platform technology and manufacturing processes. Industry and academia develops vaccine platform technology and applies to priority endemic diseases (e.g. Nipah, Ebola, Influenza, Plague, Lassa fever), proving tailored efficacy in humans. |

CEPI, working with funding and delivery partners (academia, industry) progresses and reports on disruptive innovations to improve vaccine platform technology and manufacturing processes. Industry and academia develops vaccine platform technology and applies to wider set of endemic diseases, proving tailored efficacy in humans. |

CEPI, with partners, progresses disruptive innovations to innovate in vaccine platform technology and manufacturing processes. Industry and academia develops vaccine platform technology and applies to wider set of endemic diseases, proving tailored efficacy in humans. Manufacturing capacity is sustained through demand for adult vaccinations (including in LMIC). |

CEPI works with industry and government to innovate and rapidly transition novel vaccine technology and manufacturing innovations into business as usual. Industry and academia develops vaccine platform technology and applies to wider set of endemic diseases, proving tailored efficacy in humans. Manufacturing capacity is sustained through demand for adult vaccinations (including in LMIC). |

Readily programmable vaccine platform technology available, able to be rapidly re-purposed to an emerging Disease X threat. |

|

Recommendation 12 Stimulate a move towards innovative technologies to reduce the complexity of vaccine manufacturing processes and make technology transfer and scalable manufacturing easier in a pandemic by investing in R&D. (Industry (IFPMA), academia, CEPI, Gavi) |

CEPI (with Wellcome) invests in disruptive innovations to improve technology platforms and manufacturing processes. Industry and academia collaborate to understand the causes of instability and to drive improvements in Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs). Industry and academia, working with governments invests in R&D to accelerate development of needle-free vaccine formulations, including to prove vaccine efficacy. |

Programmable vaccine platform technologies demonstrate measurable improvements in thermostability. Industry and academia, working with governments invests in R&D to accelerate development of needle-free vaccine formulations, with initial proof of vaccine efficacy (in humans).. |

Innovations, such as 2nd generation LNPs, are established addressing key thermostability issues. Multiple vaccine candidates are in preclinical trials to be administered needle-free. Efficacy of needle-free formulations proved for use in humans using multiple platforms. |

Innovations, such as 2nd generation LNPs, are established and able to be transferred to facilities globally. Multiple vaccine candidates are in late stage clinical trials to be administered needle-free. Efficacy of needle-free formulations proved for use in humans using multiple platforms. |

Vaccine platforms optimised for large scale production and simplified routes of administration and storage. |

|

Recommendation 16 Governments and industry to share risk to maintain vaccine manufacturing capacity. (Gavi, WHO, CEPI, regional initiatives, industry, Developing Countries Vaccine Manufacturing Networks) |

Gavi, WHO, CEPI and regional initiatives agree a medium to long term plan to expand capabilities of existing manufacturers in LMICs, and establish sustainable capacity in regions with no significant capacity. Industry and Governments invest in sustainable regionalised manufacturing capability. |

Gavi, WHO, CEPI and regional institutions mobilise public and private finance behind the implementation plan and begins supporting scale up of manufacturing capacity. Industry and Governments invest in sustainable regionalised manufacturing capability. |

Gavi, WHO, CEPI, regional institutions and industry partners work with development finance institutions and private investors to mobilise finance and implement medium term plan. Regional facilities producing SRA approved or WHO emergency use listed or pre-qualified products for regional and international use. Industry and Governments invest in sustainable regionalised manufacturing capability. |

Gavi, WHO, CEPI, regional institutions and industry partners work with development finance institutions and private investors to mobilise finance and implement medium term plan. Regional facilities producing SRA approved or WHO emergency use listed or pre-qualified products for regional and international use. Industry and Governments invest in sustainable regionalised manufacturing capability. |

Expanded capabilities of existing manufacturers in LMICs, enhancing capacity in all low capacity regions. |

Chapter 4

Cross Cutting Mission ‘Enablers’

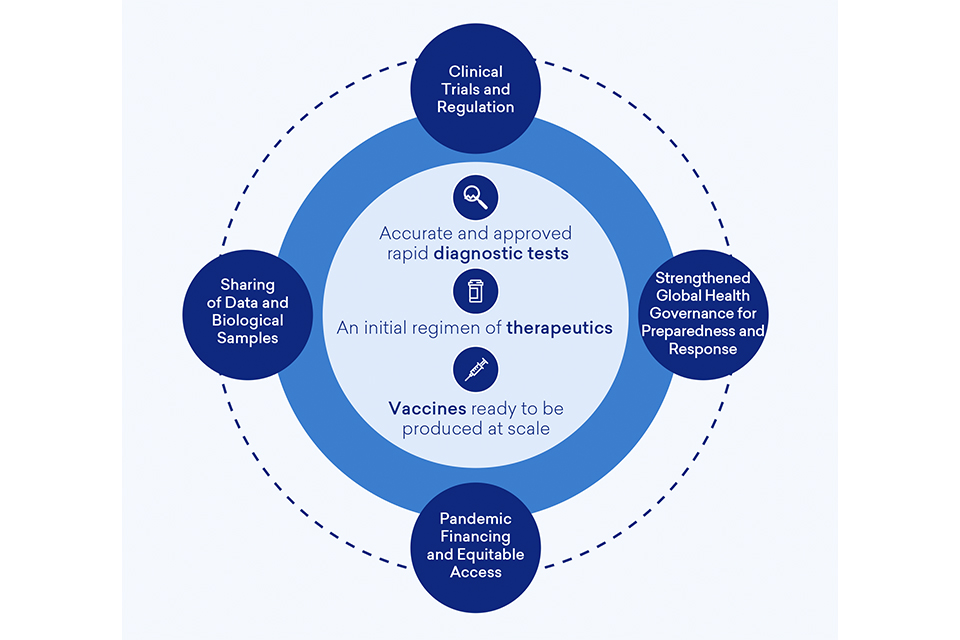

To achieve the 100DM goals of (i) accurate and approved rapid diagnostictests; (ii) an initial regimen of therapeutics; and (iii) vaccines ready to be produced at scale for global deployment, and improve future pandemic preparedness, we need to make the exceptional routine by embedding best practice in business-as-usual activity. We also need to agree ‘rules of the road’ that come into effect in a pandemic, agreeing these ahead of time so no time is wasted negotiating the basics.[footnote 116]

The 100DM provides a set of actionable recommendations[footnote 117] to embed best practice and improve standards and protocols necessary to accelerate the DTV development pipeline and improve preparedness. These address a number of fundamental cross-cutting enablers and fall across the four categories outlined below:

Diagram 6

Improvements to Clinical Trials Capability and Regulation Processes

The 100DM recommends scoping work is undertaken (led by the WHO) to determine how a network of clinical trial platforms could be implemented to enable a coordinated and efficient approach to the testing of DTVs[footnote 118] and the creation of regional mechanisms to coordinate and prioritise clinical trials of DTVs.[footnote 119]