Predicting harm among incels (involuntary celibates): the roles of mental health, ideological belief and social networking (accessible)

Published 15 February 2024

Joe Whittaker

Department of Criminology, Sociology, and Social Policy

School of Social Sciences, Swansea University

William Costello

Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin School of Psychology, Swansea University

Andrew G. Thomas

School of Psychology, Swansea University

Study context

The following statement is from the authors and may not reflect the position of the Commission for Countering Extremism (CCE) of the UK government: This study was conducted with the co-operation of members of the incel community. As a research team, we do not support all the views of the incel community. At the outset of this research, we outlined a mission statement on our project website. Our mission statement included our resolution(s) to base psychological findings around direct engagement with the incel community as individuals, to investigate incel beliefs and behaviour without sensationalising or demonising them, and to not judge all incels by the actions, behaviours or views of the most extreme minority.

To facilitate direct engagement with our research participants, we paid for their time in completing the surveys. This report contains broad descriptive information and associations about the sample of participants as a whole. It does not contain information about specific individuals. As made clear in our mission statement, the data we gather is completely anonymised and not shared with third parties, including funders (i.e. the CCE). Further details of how we retained participant anonymity are outlined in the methods section of this report. It is important to us that our research is conducted ethically, impartially and with integrity.

Executive summary

Incels are a sub-culture community of men who forge a sense of identity around their perceived inability to form sexual or romantic relationships. In recent years, there has been a small, but growing, number of violent attacks that have been attributed to individuals who identify as incels. The purpose of this study was to use a large sample of incels from the UK and US to establish (a) their demographic make-up; (b) the consistency of their attitudes and beliefs; (c) their adherence to a common world view, (d) how they network with other incels; (e) whether there are cross-cultural differences between incels from the UK and US in the above; and finally, whether there is a predictive relationship between incel mental health, networking and ideology and the extent of their harmful attitudes and beliefs.

Key findings

-

Demographics: Incels were typically in their mid-twenties, heterosexual and childless. Though the majority of the exclusively US and UK sample were white, it was ethnically diverse, with 42% self-identifying as a person of colour. Most participants considered themselves from a middle class or lower middle class background. Most had some form of post-secondary school education and were either living at home or renting.

-

Mental health: In line with previous research, incels typically display extremely poor mental health, with high incidences of depression and suicidal ideation (one in three incels contemplated suicide every day for the past two weeks).

-

Attitudes and beliefs: Participants perceived high levels of victimhood, anger and misogyny. They also acknowledged a shared worldview among incels which includes identifying feminists as a primary enemy.

-

Neurodiversity: Approximately one-third scored above the cut-off of six (or higher) for a medical referral on the autism spectrum questionnaire (AQ-10). Around 80% of people who score 6+ on this measure go on to receive an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis.

-

Political beliefs: Many commentators have suggested a link between incels and the far right. However, using Pew Research’s “Ideological Consistency Scale”, this survey found that incels were slightly left of centre on average. The exception was those who agreed that violence against individuals that that cause incels harm is often justified. These individuals were right-leaning, though not extremely so – they held right-wing opinions for 60% of the items in the Ideological Consistency Scale, compared to 45% of the items for the rest of the sample.

-

Approval of violence: When asked if they justify violence against people that incels perceive as causing harm (self-defined by participants) to them, around one quarter of the sample picked either “Sometimes” or “Often”, while those who picked “Often” formed just over 5%. The average response sat between “Never” and “Rarely”.

-

Predicting harm: By quantifying harm with a composite made up of measures of angry rumination, revenge planning, displaced aggression, hostile sexism, rape myth acceptance, and justification of violence, pathway analyses demonstrate the independent predictive roles of mental health, ideology and networking in incel-related harm. However, the predictive powers of Mental Health and Ideology were more than twice that of Networking.

-

Predicting justification of violence: Those incels who felt that violence was “Often” justified against those who harm the incel community were few (5%). These individuals are more likely to hold misogynistic views, feel discriminated against, have poorer mental health and a higher tendency to displace their aggression than other incels.

Networking

-

Incels generally feel a sense of belonging within their community.

-

They predominantly communicate via anonymous (e.g. 4Chan) and pseudonymous platforms such as forums.

-

There was some offline in-person communication between incels. Ninety-nine respondents (18%) said that they had communicated with another incel in person in the past. When asked about their primary mode of communication, this number dropped to 27 (5%).

-

Networking (e.g. time spent on forums) did predict harmful attitudes/beliefs, but this was a very small effect.

UK vs US differences:

-

There are minor demographic variations, but largely similar responses between the UK and US incels.

-

UK incels perceive their social networking as more supportive and less exposing to radical online content compared to their US counterparts.

Study significance

-

This is the largest study of incels to date with a sample size of 561.

-

It is also the first to use clinical measures to quantify the neurodiversity in the incel community.

-

The results suggest that interventions targeting mental health and ideology may yield more effective harm reduction than interventions targeting networking.

-

It also reveals the qualities pertaining to those most likely to justify incel-related violence.

Introduction

Incels are a primarily online sub-culture community of men who forge a sense of identity around their perceived inability to form sexual or romantic relationships. The incel community operates almost exclusively online, providing an outlet for expressing misogynistic hostility, frustration and blame toward society for a perceived failure to include them (Speckhard et al., 2021). In recent years, the online community of involuntary celibates (incels) has risen to the top of the news and security policy agenda. This is largely due to several high-profile terrorist attacks, resulting in 59 deaths, including Isla Vista in 2014, Toronto in 2018 and Tallahassee in the same year (Moonshot, 2020), although in some cases, there has been a debate as to whether incel ideology was the driving force behind the attacks. Over the same period, the phrase has entered our everyday lexicon and become relevant in popular culture (Dex, 2022). It has also become a popular topic for news organisations, with several incel documentaries (Zand, 2022) and headlines featuring angry young men who blame their inability to date on women, which could potentially lead to terrorist violence (Townsend, 2022). The current study casts light on the incel phenomenon by conducting the largest survey of incels to date in an attempt to understand the experiences, beliefs and online networks with which incels engage.

There is some debate as to whether incels should be considered a terrorist movement. In his review of the UK’s Counter-Terrorism Prevent Strategy, William Shawcross (2023) notes that he agrees with the deputy senior national co-ordinator for counterterrorism, who argues that they should not be considered as such because they do not fit the criteria of using violence to further ideology. On the other hand, Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro (2020; 576) argue that proponents of incel-related violence have become emboldened online and ‘there is ample reason to believe violent incels remain a grave terrorism threat.’ Looking at the most recent Prevent figures, incels make up a relatively small proportion of the number of referrals (77 in total, or 1.2% of all referrals). However, incel-related cases were most likely to be adopted by a Channel panel as a case (23 out of 34, or 68%) of any recognised movement (Home Office, 2023). This suggests that while the number of cases are small in number, those that are referred may pose a risk to themselves or others. However, Prevent statistics are not a direct proxy for terrorist violence, even if they are a strand of the UK’s counter-terrorism strategy. Rather, they represent a concern that should be addressed via early intervention (HM Government, 2020).

The number of terrorist plots that can be described as “incel” is contested. The Anti-Defamation League lists 31 attacks under their “Incel Backgrounder”, although this includes individuals such as the Plymouth attacker in 2021, whose plot was not considered to be an ideologically motivated attack by UK Counter-Terrorism Police (Hall, 2023) and an individual who committed his attack in 1989, long before the present movement existed. Hoffman et al. (2020) develop a more nuanced four-tier typography of “Clear Incel Attacks”, “Attacks with Mixed-Motives that Evidence Incel Ideology”, “Acts of Targeted Violence by Incels”, and “Ex-Post Facto Inceldom”, which provide a more rigorous understanding of incel terrorism. However, Cottee (2020) suggests it would be a mistake to categorise incel-violence as terrorism, since it does not advocate the use of violence as a necessary remedy for in-group defence.

Regardless of whether the movement is a terrorist threat or not, much incel activity online meets the definition of extremism: ‘is the vocal or active opposition to our fundamental values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs’ (HM Government 2015, p.9). In the Prevent review, Shawcross argues that the movement should be countered under hate crime legislation, while the Law Commission (2021) extended existing legislation to protect women and girls, which they explicitly link to the ‘growing threat from incels calling for the rape and/or murder of women’. Analyses of the incel ecosystem have repeatedly demonstrated high levels of toxic and misogynistic language. Baele, Brace and Ging (2023) find that discussions within the incelosphere have steadily become more violent and extreme in recent years. Similarly, Ribeiro et al. (2021), who conducted an ecosystem analysis of the entire manosphere (a loose collection of online communities that focus on men’s issues), found that newer groups such as Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW) and incels had grown in popularity at the expense of older ones (e.g. Men’s Rights Activists and Pick-Up Artists). Importantly, they find that the newer communities are more toxic and misogynistic than their forerunners.

The term “involuntary celibate” was coined in 1997 by a Canadian woman who wanted to create a space for men and women who were struggling to find romance (Andersen, 2023). However, the origins of the incel movement can be found in the men’s rights movement that developed in the second half of the twentieth century. The fundamental tenant of this movement – which is mostly shared by incels today – is that feminism has placed men in a state of crisis (Hart & Huber, 2023). The first incel subreddit – /r/ForeverAlone – was created in 2010, but the movement started to gain traction in the latter half of that decade after another subreddit – /r/Incels – appeared until its ban in 2017. Afterwards, the movement grew outwards, both to other subreddits (e.g. /r/braincels) or to forums on other parts of the web, such as incels.is (Ribeiro et al., 2021). Given the cross-platform nature of the movement and the fact that many platforms are anonymous in nature, it is difficult to ascertain exactly how many incels there are. Before its banning in 2017, r/Incels had 40,000 users (Hoffman et al., 2020), although on a popular forum such as Reddit, it is likely that this includes many “lurkers” (individuals who regularly visit and read content on these platforms but do not actively participate, contribute or engage in discussions) and therefore not all users were necessarily incels. Many users could have been researchers, journalists or other interested parties. The forum incels.is currently has over 20,000 registered users, so it is likely that the movement counts its followers in the tens of thousands.

Given the large number of incels online today and a limited empirical research base, it is difficult to ascribe a “core ideology” that is shared by all members of the movement (Hart & Huber, 2023). However, there are some broadly shared beliefs that tie the movement together. Incels purport that genetic factors, evolved mate preferences and inequitable social structures restrict their access to sexual relationships with women (Brooks, Russo-Batterham, & Blake, 2022). They believe that most women are attracted to a small number of men (Chads), who monopolize sexual encounters, while the “genetically inferior” incels are excluded from the gene pool (Baselice, 2023; Blake & Brooks, 2022). Most incels subscribe to the notion that women have considerably greater power within western contemporary society and this has come at the expense of men (Thorburn, Powell, & Chambers, 2022). This idea is known as the “red pill” – an analogy taken from the 1999 film The Matrix (Wachowski & Wachowski, 1999) – which seeks to awaken men from feminism’s hold on society (Ging, 2019). This is a term and view that is shared by the wider “manosphere” and parts of the far-right (Stijelja & Mishara, 2023). Part of this is in the dating market which incels often claim is biased against unattractive men; it is often claimed that women are more sexually selective and as such around 80% of the women have sexual access to the top 20% of men, leaving the bottom 80% of men with just 20% of women (Moonshot, 2020).

According to Baele and colleagues (2023), incel ideology categorises people into one of three categories of physical attractiveness: The hyper-attractive Chads and Stacys who have their pick of the sexual marketplace, followed by average-looking “betas” (or “normies”), and then at the bottom of the pile, physically unattractive men who cannot find a mate (incels). Given this hierarchy, many incels expand on the notion of an awakening “red pill” and instead take the metaphorical “black pill” and accept that their situation is hopeless and cannot improve (Lounela & Murphy, 2023). It is worth noting that ~95% of incels report to subscribe to the worldview known as the black pill (Speckhard et al., 2021). It has been argued by some that the adoption of the “black pill” can lead towards individuals developing violent misogynistic views towards women (Roser, Chalker, & Squirrell, 2023), although it should be cautioned that, as always, the relationship between extreme attitudes and committing acts of extreme political violence is a complex and multifaceted one (Borum, 2011; Neumann, 2013; Schuurman & Taylor, 2018).

Research into the incel movement has grown substantially in the past five years. The vast majority of such research has explored these communities by conducting online content analysis from websites, forums and message boards (for example, see: Helm et al., 2022; Jaki et al., 2019). This provides an important and useful analysis, particularly when conceptualising and developing research methodologies such as the present study. However, Daly and Reed (2022) note that this is inherently limited because online activity does not represent real experiences, and this type of analysis limits the breadth and depth of the research because many users post anonymously, so one can only obtain a surface-level assessment of the phenomenon. There is also evidence that only a small number of incels regularly generate content on such platforms, calling into question whether the results of secondary analysis represent the views of incels or a smaller group of particularly vocal ones. This has led to Hart and Huber (2023) calling for a greater focus on gaining access to primary data to better expand our knowledge of the subculture.

More recently, larger primary quantitative studies have started to emerge, focusing on incel experiences, grievances, ideology and the prevalence of mental health diagnoses (e.g. Costello et al., 2022; 2023; Speckhard et al., 2021). For example, Moskalenko et al. (2022) found that that incel ideology was only weakly correlated with radicalisation, and most incels in the study (n = 219, 80%) rejected violence. Another report from the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism used LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) software to analyse language (Pennebaker, Frances, & Booth, 2001) in incel, MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way), pick-up artist and right-wing forums. Just 1.39% of incel posts could be categorised as legitimising violence, the second lowest of the groups (Perlinger, Stevens & Leidig, 2023).

What follows below is the largest survey to date (n=561) of incels, consisting of individuals who self-identify as incels from the United Kingdom (n=199) and the USA (n=362). The report is split into three sections which correspond to the Needs, Narrative, and Network of incels. We conduct a pathway analysis to attempt to predict “harm” amongst incels.

Methods

Research rationale and design

While it is true that there have been some high-quality human participant studies recently, drawing from both qualitative (Daly & Laskovtsov, 2021; Daly & Nichols, 2023; Daly & Reed, 2021) and quantitative (Costello et al., 2022; Moskalenko et al., 2022; Speckhard et al., 2021; Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2022) methodologies, there is still a dearth of understanding of the experiences and attitudes of incels. Attempting to fill this gap is the fundamental premise of this research. This study seeks to explore incel attitudes and behaviours, drawing loosely on the “3N” framework developed by Kruglanski, Bélanger and Gunaratna (2019), which attempts to understand radicalisation by assessing the relationship between three important factors: an individual’s personal Needs (such as mental health, personality traits, their quest for significance and meaning, sacred values and their collectivist shift); the ideological Narrative to which they are exposed (particularly the grievances, scapegoats and justification of violence); and the Network to which they belong (attempting to understand the group dynamics and communication between like-minded peers) (Webber & Kruglanski, 2016). This approach was recently used by Ellenberg, Speckhard and Kruglanski (2023) to conduct a cluster analysis of incels to demarcate three different ideological narratives that exist amongst incels.

It should be noted that these measures were originally designed from consultation with the existing academic literature and were split into the 3N framework post-hoc, rather than at the beginning of the research design stage. We believe that it provides a useful way of conceptualising radicalisation and categorising the types of measures that are explored. However, because of this, it should not be seen as a direct test of the framework.

Recruitment and payment

The research was described as a study of “The impact of social networking on incel attitudes, beliefs and mental health”. Incels were recruited via a mixture of social media, podcast promotion and incel forums. Potential participants were sent to a single-page website containing the research mission statement (see above), biographies of researchers and examples of existing and related publications, blogs and interviews. The web page also had a link to a pre-screener questionnaire which only showed the study link to the participants once they confirmed they were (a) over 18, using their date of birth, (b) an incel, (c) a UK or US resident, and (d) aware that questions in the questionnaire were sensitive and potentially distressing. Dates of birth entered were not linked to the participant’s responses to the main questionnaire.

Participants who completed the study were offered either £20 (UK) or $20 (US) for their time. To keep the data anonymous, payment was handled by a third-party company called Nmible Ltd. Once they completed the study, participants were given a randomly generated code to confirm their completion which they then provided to Nmible along with their personal details and bank account information for payment. Nmible sent a list of submitted completion codes each week to the researchers for verification before processing payment. This system meant that the researchers had no access to the participant’s personal data, and Nmible had no access to their survey responses. Many incels did not want to complete the payment form out of fears that their personal data might be misused. Thus, we gave them the option for the research team to donate their participation compensation to men’s mental health charity (Movember). The compensation of 126 (22.5%) participants has been donated to Movember via Nmible.

Measures and procedures

Participants were presented with an information sheet and consent form, explaining how their data would be handled and registering their informed consent. Next, they were taken to a screen explaining how the payment process worked and how it protected their anonymity. They then completed a standard demographic questionnaire, including age, sex, height, living arrangements and verification of their country of residence. The demographic questionnaire also contained a political orientation adapted from the Pew Research Centre (2014). This measure gave participants 10 pairs of statements. For each pair, they had to pick the option which best matched their views. Each pair was about a different political issue (e.g. immigration, government regulation of business, supporting the poor) and one statement gave a right-leaning view (e.g. “Government regulation of business usually does more harm than good”) while the other gave a left-leaning statement (e.g. “Government regulation of business is necessary to protect the public interest”). We made only one change to the items and that was to swap out “black people” for “ethnic minorities” in the question about racial discrimination, to reflect the fact that the ethnic make-up of the US and UK is different.

We gave participants several measures to record their psychological experience (e.g. Needs). To measure misogynistic views, we used the Hostile Sexism question from The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick & Fiske, 2018) and the short IRMA (Bendixen & Kennair, 2017). Next, sensitivity to interpersonal rejection and use of displaced aggression were measured using the eight-item version of the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (Downey & Feldman, 1996) and The Displaced Aggression Questionnaire (Denson, Pederson & Miller, 2006) respectively. To measure mental health, we used the PHQ-9 (Kroenke, Spitzer & Williams, 2001) for depression and GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) for anxiety, which are tools commonly used by the NHS (National Health Service) to screen for these mental health issues. A three-item scale of loneliness (Hughes et al., 2004) was also included, as was the AQ-10 (Alison, Auyeung & Baron-Cohen, 2012) a tool used by primary care providers in the UK to guide ASD (autism spectrum disorder) referrals.

After Needs, we recorded their adherence to incel ideology (e.g. Narrative) using a custom-built questionnaire. Participants were first asked whether they considered themselves part of the incel community, and if so, how long had they had been part of it for. They were then asked whether they felt there was such as a thing as ‘incel ideology’ and responded using a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ question, and they were also asked to rate, using a 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) scale to what extent they felt that incels had a shared worldview. Then, they were presented with a description of a popular incel belief:

Some incels believe in biological determinism, more specifically in the 80/20 rule, which states that 80% of women desire only 20% of men. In this view, men who are usually good looking, muscular, tall and wealthy, or have otherwise high status (e.g. “Chads”) are popular among attractive, sexually promiscuous women who are vain and obsessed with jewellery, makeup and clothes (e.g. “Stacys”). Men who do not fit the description of a Chad are destined for a life of loneliness and will never have a willing sexual partner or a meaningful intimate relationship.

They were asked to what extent they agreed with this statement using a 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) scale and whether they thought most incels agreed with it using ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ responses. Next, incels were presented with six groups in a random order (Women; Non-incel men; Wider society; The political right and left; Feminists; and Incels themselves) and asked to what extent they thought each was an enemy of the incel community. They responded using the same 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) scale. The next question asked incels whether they felt violence against those who caused harm to incels was ever justified:

Some people think that violence against other people is justified if they are causing harm to incels. Other people believe that, no matter what the reason, this kind of violence is never justified. Do you personally feel that this kind of violence is often justified, sometimes justified, rarely justified, or never justified?

Reponses were given using a “Never”, “Rarely”, “Sometimes” and “Often” scale. Finally, participants were asked nine questions aimed at measuring their perceptions of incels as a discriminated against group. This measure was adapted from Wolfowicz, Weisburd and Hasisi (2023), with “Islam” swapped out for “Incels.”

The final part of the questionnaire addressed the interactions between incels (e.g. Networks). Participants were shown seven different networking methods in a random order (Anonymous forums/social media, e.g. 4chan; Regular forums/social media (with accounts); In person; Telephone calls; Video conferencing, e.g. Zoom, Teams; Discord; and Messaging services, e.g. Whatsapp, Telegram). Then, they were asked to think about their contact with other incels over the last year and assign a percentage of time that each platform was used as a total of their contact time. Follow-up questions were asked about any platform given a percentage greater than 0. These follow-up questions pertained to experiences over a typical week, and asked participants how many hours they spent using the platform and how many incels they interacted with on it. These two frequency questions were recorded using a pseudo-exponential scale from 1 (less than an hour, 0 people) to 9 (more than 33 hours, more than 20 people). All other items were recorded on a five-point Likert scale, with higher numbers including greater agreement or higher frequency. These questions related to how often the participant came across radical people and radical content. For the anonymous and pseudonymous forums/social media platforms they were also asked how often they engaged with other users and created content. Finally, for each method they were asked six items related to feelings of acceptance and social support felt when using the methods, using a 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) scale, which were averaged to produce one number representing feelings of social support for that medium. There were some other questionnaires used in the study, pertaining to personality (e.g. Sociosexuality) and some open-ended qualitative questions about Narrative and Networking that are not reported here for brevity.

Before exiting the questionnaire, the participants were given a reminder of how payment worked and were asked to indicate whether they wanted to be paid or to have their compensation donated to charity. After making their choice, participants were taken to a debrief form which contained their unique completion code and link to the Nmible website. The materials and procedure were approved by the School of Psychology Ethics Committee, Swansea University. Customised questionnaire items generated for this project can be found in the Annex.

Data quality

The data was subject to rigorous screening practices to identify duplicate responses and responses submitted without due care and attention. Because payment was handled by a third party, and required participants to give their genuine personal details, the payment provider was also able to alert us to (and not pay) duplicate and spam responses. Together, we detected and removed 103 submissions. This constituted 15.5% of the total responses received. In addition to removing noise from the data, this raises questions about the potential for bias in other incel questionnaire studies where no external verification of completion takes place.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics for the sample can be found in Table 1. On average, the vast majority of incels were in their mid-twenties, heterosexual, childless and chose “involuntarily celibate” as their relationship status. Though the majority of sample was white, it was ethnically diverse, with 42% self-identifying as a person of colour. These demographics are consistent with surveys of incels conducted in the last two years (Costello et al., 2022; 2023; Moskalenko et al., 2022; Speckhard et al., 2021). When asked about their perception of their socioeconomic class, most participants considered themselves from a middle class or lower middle class background. Most had some form of post-secondary school education and were either living at home or renting.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics for the UK and US Subsamples

| Characteristic | Total sample (N = 561) |

UK (N = 199) |

US (N = 362) |

t, χ2(df) | p | d, V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 25.92 (6.60) | 26.86 (6.46) | 25.41 (6.62) | 2.517 (559) | .012 | 0.22 |

| Age, bins | 18.579 (4) | < .001 | 0.18 | |||

| 18-21 | 146 (26%) | 43 (21.6%) | 103 (28.5%) | |||

| 22-25 | 169 (30.1%) | 45 (22.6%) | 124 (34.3%) | |||

| 26-29 | 124 (22.1%) | 55 (27.6%) | 69 (19.1%) | |||

| 30-33 | 66 (11.8%) | 32 (16.1%) | 34 (9.4%) | |||

| 34+ | 56 (10%) | 24 (12.1%) | 32 (8.8%) | |||

| Height (cm) | 174.10 (10.78) | 174.46 (11.50) | 173.9 (10.38) | 0.594 (555) | .553 | 0.05 |

| Sexual orientation | 10.412 (3) | .015 | 0.14 | |||

| Heterosexual | 520 (92.7%) | 181 (91%) | 339 (93.6%) | |||

| Homosexual | 10 (1.8%) | 7 (3.5%) | 3 (0.8%) | |||

| Bisexual | 24 (4.3%) | 6 (3%) | 18 (5%) | |||

| Other | 7 (1.2%) | 5 (2.5%) | 2 (0.6%) | |||

| Socio-economic status | 9.477 (4) | 0.05 | 0.13 | |||

| Upper | 12 (2.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 11 (3%) | |||

| Upper-middle | 82 (14.6%) | 21 (10.6%) | 61 (16.9%) | |||

| Middle | 228 (40.6%) | 82 (41.2%) | 146 (40.3%) | |||

| Lower-middle | 152 (27.1%) | 62 (31.2%) | 90 (24.9%) | |||

| Lower | 87 (15.5%) | 33 (16.6%) | 54 (14.9%) | |||

| Fatherhood | 11.194 (2) | .004 | 0.14 | |||

| No children | 549 (98%) | 189 (95.5%) | 360 (98%) | |||

| 1 child | 8 (1.4%) | 6 (3%) | 2 (0.6%) | |||

| 2 children | 3 (0.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Ethnicity | 12.835 (5) | .025 | 0.15 | |||

| White | 326 (58.1%) | 128 (64.3%) | 198 (54.7%) | |||

| Black | 88 (15.7%) | 32 (16.1%) | 56 (15.5%) | |||

| Mixed race | 34 (6.1%) | 12 (6.0%) | 22 (6.1%) | |||

| South Asian | 38 (6.8%) | 11 (5.5%) | 27 (7.5%) | |||

| Hispanic | 21 (3.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 20 (5.5%) | |||

| Other | 54 (9.6%) | 15 (7.5%) | 39 (10.8%) | |||

| Education | 21.926 (4) | < .001 | 0.2 | |||

| Did not graduate high school | 44 (7.8%) | 22 (11.1%) | 22 (6.1%) | |||

| Graduated high school | 133 (23.7%) | 33 (16.6%) | 100 (27.6%) | |||

| Completed some FE/HE | 191 (34%) | 58 (29.1%) | 133 (36.7%) | |||

| Completed undergraduate degree | 142 (25.3%) | 59 (29.6%) | 83 (22.9%) | |||

| Completed postgraduate degree | 51 (9.1%) | 27 (13.6%) | 24 (6.6%) | |||

| Living arrangements | 12.438 (4) | .014 | 0.15 | |||

| Homeowner | 44 (7.8%) | 23 (11.6%) | 21 (5.8%) | |||

| Renting alone | 142 (25.3%) | 50 (25.1%) | 92 (25.4%) | |||

| Renting with others | 93 (16.6%) | 40 (20.1%) | 53 (14.6%) | |||

| Living with parents/grandparents | 278 (49.6%) | 86 (43.2%) | 192 (53%) | |||

| Other | 4 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.1%) | |||

| Singlehood reason | 25.250 (2) | < .001 | 0.21 | |||

| By choice | 71 (12.7%) | 44 (22.1%) | 27 (7.5%) | |||

| Involuntarily celibate | 480 (85.6%) | 151 (75.9%) | 329 (90.9%) | |||

| Temporary (between relationships) | 10 (1.8%) | 4 (2%) | 6 (1.7%) | |||

| Not in employment, education, or training | 8.285 (5) | .141 | 0.12 | |||

| Full-time employment | 238 (42.4%) | 87 (43.7%) | 151 (41.7%) | |||

| Full-time education | 92 (16.4%) | 28 (14.1%) | 64 (17.7%) | |||

| Part-time employment | 71 (12.7%) | 32 (16.1%) | 39 (10.8%) | |||

| Part-time education | 27 (4.8%) | 7 (3.5%) | 20 (5.5%) | |||

| Employment-education mix | 33 (5.9%) | 7 (3.5%) | 26 (7.2%) | |||

| None | 100 (17.8%) | 38 (19.1%) | 62 (17.1%) |

Notes: SD = standard deviation; a measure of variability around the mean. The last three columns of the table contain statistical information that might be useful to scientists and statisticians. ‘t, χ2(df)’ indicates the results of a test of mean differences (a t-test) or frequency differences (a Chi-squared test) between groups. Column p denotes statistical significance. If this value is < .05 then the groups can be considered different from each other for that characteristic. The final column denotes the effect size of the mean difference (Cohen’s d) or frequency difference (Cramer’s V). These can be used to understand how big the difference is; d can be interpreted as follows: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large. V can be interpreted as follows: 0.1 = small, 0.3 = medium, 0.5 = large.

Two demographic factors are often described as important to incels’ lack of success in the sexual marketplace. The first is the lack of engagement in employment, education or training (NEET). In the present sample, 18% reported being NEET, which is consistent with previous research on incel wellbeing (Costello et al., 2022). Conversely, 42% reported being in full-time work and 16% in full-time education. Second, incels often purport that height is a key factor preventing them from engaging in a relationship. This study found that incels self-reported their height as 174cm (5’8.5”) on average, which is very close to the 176cm (5’9.3”) average for England (National Health Service, 2021) and 175cm (5’8.9”) in the US (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). Despite these two factors – NEET status and height – being an often-cited grievance for incels to explain their frustration (O’Malley & Helm, 2022), there seems to be little support for it within our sample. It demonstrates the possibility that grievances need not necessarily be grounded in reality to become widely accepted within a community.

Many commentators have suggested a link between incels and the extreme right wing (O’Malley, Holt, & Holt, 2022; O’Malley & Helm, 2022), with ecosystem analysis demonstrating an overlap within the “manosphere”, which contains elements of the far right (Ribeiro et al., 2021). Using Pew Research’s “Ideological Consistency Scale”, this survey shows a complex picture. When asked about their own political orientation via this series of binary policy position questions, incels were slightly left of centre (Table 2). The only “right-wing” views that were selected by the majority of incels were that the ‘Government is almost always wasteful and inefficient’ and feeling that ‘Ethnic minorities who can’t get ahead in this country are mostly responsible for their own condition.’ On the other hand, they were substantially left of centre on questions regarding homosexuality, corporate profits and social benefits. The finding on homosexuality is interesting given that linguistic analysis has found homophobic language on incel forums (Jaki et al., 2019). One should take caution before inferring these findings to mean that there is no overlap between the far right and incels, or the incel typical worldview. Concepts such as “extreme right wing” are complex and cannot easily be reduced into a set of policy questions. This points to a general stretching of the concept to fit a range of diverse (and often mutually conflicting) ideologies (Pirro, 2023). Our findings suggest that in terms of public policy matters, incels do not appear to align with the right wing. This is in line with previous research which found that ~63 percent of incels self-reported a left-leaning or centrist political affiliation (Costello et al., 2022).

Table 2. Percentage of sample which sided with a right-wing belief over a left-wing alternative.

| Political belief (abridged) | Total sample (N = 561) |

|---|---|

| 1. Government wasteful/inefficient | 341 (60.8%) |

| 2. Government regulation of business harmful | 210 (37.4%) |

| 3. Poor people have it easy because of benefits | 224 (39.9%) |

| 4. Government can’t do more for needy | 283 (50.4%) |

| 5. Ethnic minorities responsible for their outcomes | 343 (61.1%) |

| 6. Immigrants today are a burden | 256 (45.6%) |

| 7. Military strength brings peace | 228 (40.6%) |

| 8. Corporations profits are fair | 208 (37.1%) |

| 9. Environmental regulations hurt economy | 243 (43.3%) |

| 10. Homosexuality should be discouraged | 227 (40.5%) |

| Mean score (SD) | 1.54 (0.25) |

Note: The mean score ranges from 1 (Extremely right wing) to 2 (Extremely left wing). A score of 1.5 indicates a balance between right-wing and left-wing responses. The sample average of 1.54 is significantly left of centre, but only slightly so (t(560) = 4.031, p < .001, d = 0.17).

Needs: The psychological experience of inceldom

The first factor within the 3N radicalisation model is the individual’s personal Needs. As Webber and Kruglanski (2016) note, it is vital to understand an individual’s personality and psychological experience; people are often driven by factors such as humiliation, injustice, vengeance or social status, which may differ from the wider movement to which they belong. Table 3 summarises the Needs measured in this study.

Table 3. Incel ‘Needs’ measures - Mental health, emotion, and misogynistic beliefs

| Characteristic | Total sample (N = 561) |

|---|---|

| Autism spectrum: AQ-10, mean (SD) | 4.46 (2.28) |

| Autism spectrum: AQ-10, % over 6 points | 172 (30.7%) |

| Depression: PHQ-9, mean (SD) | 13.03 (6.93) |

| Depression: PHQ-9, % over 15 points | 218 (38.9%) |

| Depression: Loneliness, mean (SD) | 2.54 (0.56) |

| Depression: Suicidal thoughts, % nearly every day | 121 (21.6%) |

| Anxiety: GAD-7, mean (SD) | 8.99 (5.81) |

| Anxiety: GAD-7, % over 10 points | 241 (43%) |

| Emotions: Angry Rumination | 4.21 (1.66) |

| Emotions: Revenge Planning | 3.41 (1.55) |

| Emotions: Displaced Aggression | 2.39 (1.18) |

| Emotions: Rejection Sensitivity | 13.80 (5.72) |

| Extreme views: Hostile Sexism | 3.17 (1.03) |

| Extreme views: Rape Myth Acceptance | 2.81 (1.20) |

Mental health

Incel mental health is poor, with more than a third of the sample meeting the criteria for both moderate depression (39%) and anxiety (43%) using NHS diagnostic tools. These data are concerning given the relationship between suicide-risk and depression and anxiety in men (Bjerkeset, Romundstad & Gunnell, 2008). Indeed, a fifth of the sample reported experiencing suicidal thoughts (item 9 of the PHQ-9) nearly every day. Many incels openly discuss their suicidal plans online (Daly & Laskovtsov, 2021). Extreme inceldom may look more like suicidality than violence towards others (Costello & Buss, 2023). The two strongest correlates of male suicidal ideation are failure in heterosexual mating and burdensomeness to kin (de Catanzaro, 1995). Both factors are extremely salient for incels, some of whom are NEET (not in education, employment or training) and many more still living with their parents into adulthood (Costello et al., 2022).

Levels of loneliness are also high in our data, with 48% of the participants selecting the highest value to all three loneliness questions in the study. Sparks, Zidenberg and Olver (2022; 2023) highlight how only one third of incels.co users indicated that they had any friends. Costello et al. (2022) also found high levels of loneliness among incels, suggesting that incels may be missing a key buffer sheltering them from the adverse effects of romantic rejection. These data are concerning given that meta-analyses show that social isolation is associated with increased risk for early mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015).

Autism Spectrum Disorder

One component of incels’ psychology that should not be overlooked is the high rates of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) within the community. Speckhard and Ellenberg (2022) found that 18.38 percent of incels reported having such a diagnosis. There is some troubling evidence that ASD may be a correlate, but a not cause, of extreme violent acts such as mass shootings like in the case of Elliot Rodger, the most notorious incel killer (Allely & Faccini, 2017). Analysis from Allely et al. (2017) provides a conservative estimate of ASD in six of 75 mass shooting cases (8 percent), approximately eight times higher than the prevalence of ASD in the general population (Elsabbagh et al., 2012). In our data, approximately 30 percent of incels pass the cut-off for referral using the AQ-10 – a brief questionnaire that primary care practitioners use when deciding to make a referral for an autism spectrum disorder assessment. We follow Al-Attar’s (2020) lead in advising caution against drawing conclusions of causality between autism and terrorism given the co-existing mental health problems and psychosocial adversities that autistic people face, as well as the heterogeneity of autism.

Sensitivity, anger and misogynistic beliefs

Costello et al. (2022) found that incels have a significant tendency for interpersonal victimhood, which includes measures of rumination: the preoccupation with reflecting on past instances of victimisation. Echoing this, incels in our data had higher levels of Angry Rumination than population samples. They also had higher levels of Revenge Planning, but actually had slightly lower Displaced Aggression when compared to a similar age group (Denson, Pedersen & Miller, 2006). Thus, when slighted, incels have a greater tendency towards thinking about how to seek revenge against those who have wronged them, but report being less likely to take out their frustrations on a third party who have done them no wrong. Similarly, they scored higher than average for Rejection Sensitivity (Downey & Feldman, 1996), meaning that they anticipated that others, including friends and family, would reject them if they reached out for social support. Two measures of misogyny, Hostile Sexism (Glick & Fiske., 2018) and Rape Myth Acceptance (Bendixen & Kennair, 2017), were also higher than population estimates. However, Costello and Buss (2023) note that a common measure used to ascertain men’s propensity for sexual violence is to ask about their “willingness to rape if you could get away with it”. Counterintuitively, incels score significantly lower than the general population in this measure. Speckhard et al. (2021) found that 13.6% of incels reported some willingness to rape if they could get away with it, compared to respective samples of ~35%, ~20–25%, ~19% and ~30% of men in the general population (Malamuth, 1981; Palmer, McMahon & Fissel., 2021; Hahnel-Peeters, Goetz & Goetz., 2022; Young & Thiessen, 1992).

Narratives: incel ideology

The psychological force in the 3N model of radicalisation is understanding the cultural Narrative with which incels engage. When opting for violence (or not) an individual is ‘restricted to choose from a list of culturally determined means that are socially shared and rooted in an ideology to which their group subscribes.’ (Webber & Kruglanski, 2016, 39). In essence, one can understand a great deal as to why some movements are susceptible to violence and others are not by what their ideology allows, as Neumann (2013, 880) explains:

‘What made Irish Republican Army recruits blow up police stations in Northern Ireland while Tibetans have resisted the “occupation” of their homeland peacefully needs to be explained, at least in part, with reference to the different ideologies that members of the two nationalist movements have come to accept as true.’

There has been extensive research which has sought to understand incel narratives via online content analyses (O’Malley & Helm, 2022; Roser et al., 2023; Thorburn, Powell & Chambers., 2022). This survey seeks to complement this existing research by assessing adherence to incel ideology among our participants. The findings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Incel ‘Narrative’ and ‘Network’ measures – ideology, justification of violence, enemies and time spent in the community.

| Characteristic | Total sample (N = 561) |

|---|---|

| Ideology: Feelings of discrimination, mean (SD) | 3.45 (1.00) |

| Ideology: Believes incel ideology exists, % agree | 383 (68.3%) |

| Ideology: Personal agreement with 80/20 view, % agree | 360 (64.2%) |

| Ideology: Incels share the same worldview, % agree | 341 (60.8%) |

| Ideology: Incels agree with 80/20 view, % agree | 454 (80.9%) |

| Justification of violence: Violence, mean (SD) | 1.82 (0.93) |

| Justification of violence: Violence, % sometimes | 107 (19.1%) |

| Justification of violence: Violence, % often | 31 (5.5%) |

| Enemies: Feminists, mean (SD) | 4.35 (0.98) |

| Enemies: The political left, mean (SD) | 3.93 (1.10) |

| Enemies: Wider society, mean (SD) | 3.85 (1.12) |

| Enemies: Women, mean (SD) | 3.75 (1.19) |

| Enemies: Non-incel men, mean (SD) | 3.19 (1.20) |

| Enemies: Incels themselves, mean (SD) | 3.06 (1.38) |

| Enemies: The political right, mean (SD) | 3.04 (1.15) |

| Community: Identify as part of the incel community | 411 (74%) |

| Community: Months in community, median (IQR) | 41 (44.75) |

| Community: Incel longer than 3 years or more | 251 (44.7%) |

Incel worldview

There was general agreement amongst respondents that incel ideology exists; just over two-thirds of respondents believed this to be the case. The majority also agreed that incels shared the same worldview, though the proportion was slightly lower (61%). When asked about a specific belief (the 80/20 rule outlined in the introduction above) almost two thirds of incels indicated that they personally agreed with it, while more than 80% felt that most incels agreed with it.

Incels also believed that they were discriminated against, scoring an average of 3.4 on a five-point likelihood scale. It is worth noting that the responses showed agreement but a lack of consensus. For example, using a five-point Likert scale, incels answered the items with a score of around 3.5, which is part-way between “neither agree nor disagree” and “somewhat agree”. This reflects the fact that the most common answer to these questions was “somewhat agree”.

Out-groups

A key part of ideology is the idea of clearly identified “out-groups” who are often held responsible for the “in-groups” woes, and in some cases, are considered a viable (or even mandatory) target of political violence (Berger, 2017; Ingram, 2016). When asked about seven different groups, incels considered “Feminists” to be the biggest enemy of the incel community, followed by “The political left”, “Wider society” and “Women”. This is in keeping with existing research which has largely pointed to these groups as the key enemies of incels (Daly & Reed, 2022, Stijelja & Mishera, 2023; Thorburn, Powell & Chambers, 2023). At first glance, this may appear to conflict with the findings above, which suggest that incels are slightly left of centre politically. However, it should be noted that that the political spectrum questions did not relate specifically to the titles of “left” or “right”, but rather asked a series of policy questions. Therefore, terms such as these may carry positive or pejorative connotations without directly relating to policy preferences. Moreover, this sample were only slightly left of centre, which opens the possibility that they conceptualised “the political left” as those who are considerably more left wing.

Justification of violence

Given the policy concern over incel-related terrorism, it is important to understand how many of the sample justify violence against people whom incels perceive as causing harm to them.[footnote 1] Around one quarter of the sample picked either “Sometimes” or “Often”, while those who picked “Often” formed just over 5 percent. Although this means that the average response sat between “Never” and “Rarely”, these are still alarmingly high response rates for this measure, supporting research which finds that violence is regularly supported within incel communities (Baele, Brace, Coan, 2021). This is somewhat in line with other incel-related research; Speckhard et al. (2021) asked participants whether they sometimes entertain thoughts of violence toward others, of which 26% responded affirmatively. It should be noted that Moskalenko et al. (2022) found that incel ideology was only weakly correlated with radicalisation, and that most incels in the study (n = 219, 80%) rejected violence. Incels were also asked (scored on a five-point scale, with 1 = “not at all” and 5 = “very much”) about attitudes relevant to incel violence. The average incel score for the specific item “I admire Elliot Rodger for his Santa Barbara attack”, was (M = 1.83; SD = 1.25) (Moskalenko et al., 2022).

It is difficult to anchor these incel-specific responses to a societal baseline. However, a comparison can be made with Pauwels and Schils (2016), who found that only 2.4% of their sample of 16–24 year-olds expressed some level of support for violent extremism. Their sample is of a broadly similar age range to ours, which is a helpful comparison, but 65% of the respondents were female, which does not help, given the sex difference in young adult acts of violence crimes (Goodwin, Brown & Skilling, 2022; Nivette et al., 2019). At the same time, incel report of violence seems comparable to recent nationally representative research, such as that by Wintemute and colleagues (2022), who found that 20% of the United States public thought that violence is sometimes, usually or always justified, while Ipsos (2023) found a similar figure amongst French respondents.

Finally, we urge caution in over (or under) interpreting findings that relate to the justification of violence in the context of violent extremism. It is an imperfect proxy for radicalisation because it measures an attitude rather than behaviours. It almost certainly over-estimates the level of individuals who would actually engage in violence because individuals often do not engage in behaviours that they intend to – this is often called the intention-behaviour gap (Sheeran & Webb, 2016; Conner & Norman 2022). Moreover, it may under-estimate violence because of social desirability bias (Krumpal, 2013).

Network: The Group Dynamics of Inceldom

Maintaining any kind of ideology, including an extremist one, requires consensual validation. This is why individuals seek out like-minded people and form Networks. When it comes to radicalisation, these networks, in which like-minded individuals may justify violent activities, are essential in providing validity to the ideologies from which they stem (Webber & Kruglanski, 2016). Recent years have seen more ecosystem analyses of the incelsphere, typically scraping a range of online platforms to assess the relationships between the different platforms (Baele, Brace & Ging, 2023; Ribeiro et al., 2021). We complement this research by questioning incels on their social media usage. This includes their platforms of choice; the time they spend online; the type of content they see; and how they see themselves within their community.

Being part of the community

As can be seen at the bottom of Table 4, almost three quarters of the sample considered themselves part of the incel community. Of these, the median time they had spent as part of the community was 41 months (around 3 and a half years). Of the whole sample, almost half of them had been an incel for three years or longer. When asked whether their time on social media provided a feeling of social support and acceptance, respondents, on average, “slightly agreed”, although this did not seem to differ across the type of social media platform (Table 5). This is particularly important within the 3N framework, as a like-minded community with shared grievances and strong social bonds can provide individuals with the personal significance that they crave, potentially causing identity fusion with the group (Rousis et al., 2023). If the group supports violence, then it is possible to act as an incubator for individual violence (Webber & Kruglanski, 2016). This point has been made specifically in the context of incels by Ellenberg and colleagues, who note that ‘by engaging online with incel forums, they find a network that validates their feelings and introduces them to an overarching ideology. The ideology provides a worldview that allows them to move from self-blame for their failures with women into anger and violence turned inward or outward’ (Ellenberg, Speckhard & Kruglanski, 2023, 1).

Table 5.

Incel use of different social networks. Those who used a method within the last year were asked follow-up questions about their experience with the communication type within the last two weeks, including content creation and exposure to radical people and content.

| Characteristic | Anonymous social media | Registered social media | In Person | Telephone | Video calls | Discord | Messaging apps | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within the last year: Ever used | 308 (54.9%) | 286 (51%) | 99 (17.6%) | 37 (6.6%) | 36 (6.4%) | 172 (30.7%) | 99 (17.6%) | 1.85 (1.59)a |

| Within the last year: Often used (over 25%) | 229 (40.8%) | 191 (34%) | 35 (6.2%) | 6 (1.1%) | 7 (1.2%) | 88 (15.7%) | 35 (6.2%) | - |

| Within the last year: Primary (over 50%) | 182 (32.4%) | 149 (26.6%) | 27 (4.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | 6 (1.1%) | 54 (9.6%) | 20 (3.6%) | - |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Time spent | 3.95 (2.03) | 4.68 (1.99) | 2.30 (1.76) | 2.16 (1.19) | 2.36 (1.31) | 3.08 (2.05) | 2.83 (1.81) | 3.84 (1.67) |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Incels engaged with | 5.79 (2.69) | 5.16 (2.70) | 2.66 (1.86) | 2.51 (1.26) | 3.44 (2.37) | 4.48 (2.48) | 3.55 (2.4) | 4.85 (2.39) |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Interaction | 2.42 (1.09) | 2.50 (1.08) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Content generation | 1.88 (0.91) | 1.84 (0.96) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Radical people | 3.13 (1.10) | 2.71 (1.11) | 2.00 (1.13) | 1.97 (0.96) | 2.17 (1.13) | 2.48 (1.26) | 2.24 (1.19) | 2.74 (1.01) |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Radical content | 3.10 (1.15) | 2.7 (1.10) | 1.95 (1.07) | 1.97 (0.90) | 2.11 (1.14) | 2.49 (1.29) | 2.27 (1.18) | 2.71 (1.00) |

| Within the last 2 weeks: Feelings of support | 3.44 (0.92) | 3.20 (1.05) | 3.47 (0.93) | 3.50 (0.93) | 3.72 (0.81) | 3.58 (0.92) | 3.67 (0.75) | 3.38 (0.83) |

Note: aMean number (+SD) of mediums used within the last year.

Social media platforms

The most common methods used by incels within the last year to communicate were anonymous (e.g. 4chan) and registered (e.g. incels.co, Twitter) social media, including forums (see Table 5). Every type of social network we asked about was used by some of the sample, including a modest proportion of in-person meetings. This type of activity is congruent with the ecosystems research of Baele and colleagues (2023), who identify both anonymous “Chan” sites, as well as traditional forums and social media platforms. Typically, incels used two social network types out of the seven options we asked about. Incels were clearly more likely to engage in networks that facilitated multi-person communication rather than one-to-one communication (e.g. video and telephone calls).

When an incel indicated they had used a form of social network in the last year, we proceeded to ask them follow-up questions about their experience with them within the last week (Table 5). Time spent using each platform and the number of other incels they interacted with were asked using a pseudo-exponential scale from 1 (less than an hour, 0 people) to 9 (more than 33 hours, more than 20 people). Other items were recorded on a five-point Likert scale, with higher numbers including greater agreement or higher frequency. Results show that incels spent most of their time on anonymous and registered social media, followed closely by Discord. These three methods also led to engagement with a greater number of incels, and greater exposure to radical people and content.

One surprising finding was the number of incels who had networked in the offline domain. Ninety-nine respondents (18 percent) said that they had communicated with another incel in person in the past year. When asked about their primary mode of communication, face-to-face communication dropped to 27 (5 percent). Almost one in five participants had communicated with another incel in person. This is unexpected, because incels are typically considered to only exist within online spaces, which makes them an outlier compared to other extremist-supporting ecologies; research typically finds that adherents occupy both the online and offline domains (Gill et al., 2017; Herath & Whittaker, 2021; Whittaker, 2021). We urge caution against over-interpreting these results – there is no indication that incels are mobilising offline in any meaningful way. Rather, it is possible that individuals answered this question because they know someone in their offline life who is also an incel. A possible question for future research is how many in-person meetings are between those who have been friends for some time; such as those who met in school and share similar interests and outlooks.

Cultural differences

Aside from the aforementioned differences in demographic statistics, there were surprisingly few cross-cultural differences found for incel Needs and Narrative items (Table 6). The UK sub-sample differed on only one political belief – they were more likely to feel that environmental laws and regulation would hurt the economy than the US sub-sample. They also reported less loneliness and were less likely to see incels as their own enemy. All three of these differences were small in size.

Table 6. US and UK differences between the Needs, Narrative, and Networking measures displayed in Tables 2–5.

| UK sample | US sample | t, χ2(df) | p | d, V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political belief: Environmental regulations hurt economy | 100 (50.3%) | 143 (39.5%) | 6.042 (1) | 0.014 | .10 |

| Depression: Loneliness, mean (SD) | 2.43 (0.64) | 2.59 (0.51) | 3.274 (559) | .001 | 0.29 |

| Enemies: Incels themselves, mean (SD) | 2.87 (1.36) | 3.16 (1.38) | 2.383 (559) | .018 | 0.21 |

| Anonymous forums: Radical people | 2.79 (1.10) | 3.31 (1.06) | 3.992 (306) | < .001 | 0.48 |

| Anonymous forums: Radical content | 2.79 (1.12) | 3.26 (1.14) | 3.463 (306) | < .001 | 0.41 |

| Anonymous forums: Feelings of support | 3.66 (0.96) | 3.32 (0.87) | 3.065 (306) | .002 | 0.37 |

| Registered forums: Often used (over 25%) | 54 (27.1%) | 137 (37.8%) | 6.559 (1) | .012 | .11 |

| Registered forums: Primary (over 50%) | 42 (21.1%) | 107 (29.6%) | 4.703 (1) | .036 | .09 |

| Registered forums: Radical people | 2.51 (1.08) | 2.81 (1.11) | 2.183 (284) | .030 | 0.28 |

| In person: Often used (over 25%) | 18 (9.0%) | 17 (4.7%) | 4.152 (1) | .042 | .09 |

| Video calls: Ever used | 19 (9.5%) | 17 (4.7%) | 5.033 (1) | .025 | .10 |

| Video calls: Often used (over 25%) | 5 (2.5%) | 2 (0.6%) | 4.004 (1) | .045 | .08 |

| Messaging apps: Ever used | 52 (26.1%) | 47 (13.0%) | 15.273 (1) | < .001 | .16 |

| Messaging apps: Primary (over 50%) | 13 (6.5%) | 7 (1.9%) | 7.900 (1) | .005 | .12 |

| Messaging apps: Feelings of support | 3.86 (0.70) | 3.46 (0.76) | 2.734 (97) | .007 | 0.55 |

| Average across networks: Radical people | 2.56 (0.97) | 2.84 (1.06) | 2.862 (440) | .004 | 0.28 |

| Average across networks: Radical content | 2.52 (0.99) | 2.81 (1.00) | 2.894 (440) | .004 | 0.29 |

| Average across networks: Feelings of support | 3.58 (0.82) | 3.28 (0.81) | 3.709 (440) | < .001 | 0.37 |

A greater number of cultural differences were found for Networking items. UK participants reported coming across fewer radical people (by their own understanding of the word) and content when using anonymous social media than US participants and found this type of networking more socially supportive. UK participants were less likely to use registered social media to communicate with other incels, and when they did, they felt they encountered people with radical views less often.

In our sample, UK participants were more likely to use methods of one-to-one communication including in person, video calls and messaging applications. As with the point made above, there is little reason (presently) to believe that incels who have first networked online are conducting “meet-ups” offline. Rather, it is plausible that these are incels with whom they already networked offline. In the case of the latter, the UK sub-sample found messaging apps more supportive than US incels. Overall, when collapsing across networks used, UK participants found social networking more supportive and less likely to bring them into contact with radical people and content than US incels. All effect sizes were small to medium in size.

Predicting harmful attitudes and beliefs

To develop a better understanding about how the 3Ns contribute to the development of harm within the incel community, we performed a pathway analysis. Pathway analysis allows one to examine complex relationships between several variables. It allows one to examine, for example, whether one thing predicts another via something else. This was relevant to the current study because it is feasible that Needs, Narrative and Network interact in some way to predict harm. For example, increased Network use might lead to the development of harmful views because it increases one’s acceptance of Narrative.

This type of analysis can, however, get complex with many variables. So, we simplified it by creating a total of four overall scores using a statistical process called factor analysis. First, we created an overall ‘Harm’ score from consisting of angry rumination, revenge planning, displaced aggression, hostile sexism, rape myth acceptance and justification of violence. Next, we created three scores to use in combination to predict Harm.

One score was made from the remaining Needs variables (loneliness, anxiety, depression, ASD, and rejection sensitivity). We called this ‘Mental health’ to better reflect the meaning of its constituent parts. While ASD is not a mental health variable per se, there is a large amount of comorbidity between ASD and mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression (Hollocks et al., 2018). Next, we formed a Narrative score from all ideology items measured using a scale (feelings of discrimination, shared incel worldview, agreement with the 80/20 concept, and seeing feminists, women, the political left, and wider society as enemies). We called this score ‘Ideology’. Finally, we formed a Network score (number of social networks used, time spent on them, amount of interaction with others, content generation and exposure to radical people and content) which we called ‘Social Networking’. This score was designed to capture the strength of engagement with and exposure to the community. Thus, its individual items were based on summed total responses to these questions across individual social networks.[footnote 2]

When conducting the four factor analyses, all items clustered together well and met the statistical assumptions needed (e.g. KMOs > 0.72 and sphericity ps < .001). Only two items were excluded during the analyses because it was revealed that they did not cluster well with other items and also did not predict harm in their own right. These were (a) length of time being part of the incel community, and (b) average feelings of support gained from the community.

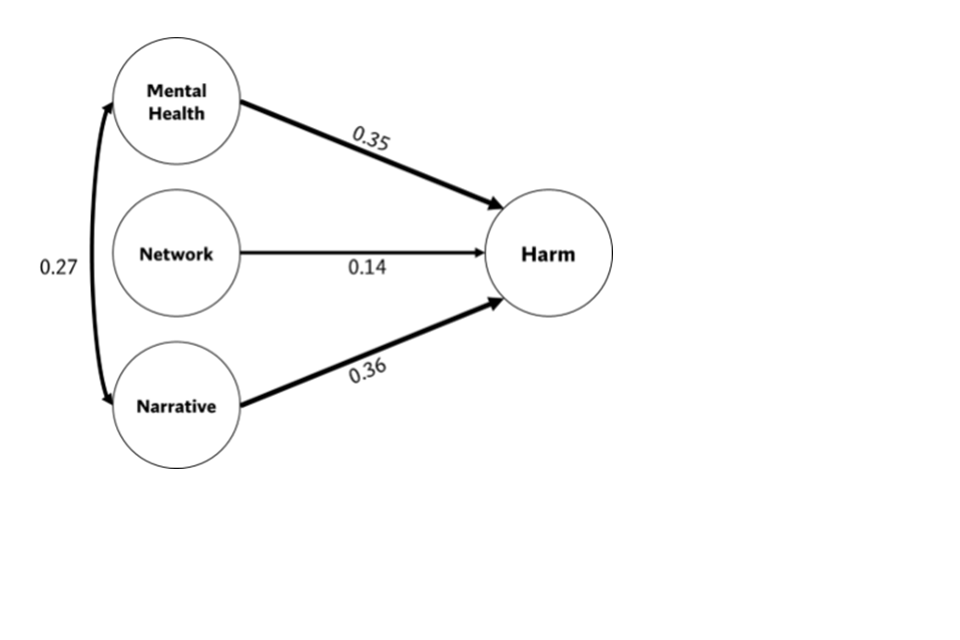

The pathway analysis (see Figure 1) showed, first and foremost, that Mental Health, Ideology, and Social Networking all independently predicted harm (i.e. they had direct effects). Harmful attitudes and beliefs were stronger among incels with poor mental health, greater network usage and more belief in the incel narrative. Furthermore, the relationship between Mental Health and Harm, and the relationship between Narrative and Harm was almost twice as strong as the relationship between Networking and Harm.

As previously mentioned, pathway analysis allows for complex associations between variables to be examined. For example, in addition to predicting harm in its own right, increased social networking could also increase risk of harm indirectly through its impact on poorer mental health. To account for this, we repeated the pathways, allowing for relationships between Mental Health, Networking and Narrative to exist. Only one relationship emerged; a bi-directional relationship was between Narrative and Mental Health (see Figure 1). This two-way relationship suggests that mental health and belief in the incel worldview affect each other, such that poorer mental health (e.g. depression, anxiety) leads to greater adherence to the worldview (e.g. belief in the 80/20 rule, seeing feminists as the enemy) and vice versa. Thus, these two predictors work in tandem, exacerbating one another and strengthening harmful attitudes and beliefs (e.g. rape myth acceptance, condoning incel violence).

Figure 1. A pathway model predicting harm using ideology, social networking and mental health factors derived from the 3N items. Figures represent standardized beta values. These range from 0 to 1.00, where 0.1 = a small effect, 0.3 = a medium effect, and 0.5 = a large effect.

Predicting justification of violence

There were a small number of incels who felt that violence was often justified against those who cause harm to the incel community. We examined differences between those who selected “often” vs other responses (e.g. never, sometimes) across all characteristics previously discussed, to offer insight as to the characteristics of those incels that may be most likely to commit an act of violence. Table 7 shows all significant differences, ordered from largest to smallest. The largest effects related to misogynistic views, how one handles anger (by planning revenge and acting out at others), and feelings of being discriminated against. Of particular note is the difference in political orientation – while the sample overall was slightly left-leaning, those more likely to say violence is often justified were more right-leaning. Specifically, those who selected often to the violence question tended to pick right-wing statements 60% of the time when completing the political orientation inventory compared to 45% of the time for the rest of the sample. Finally, the only difference in terms of social networking was in the number of incels engaged with in the last two weeks.

Table 7. Group differences between those who did and did not select ‘Often’ when asked if incel violence was justified against those causing harm to incels.

| Characteristic | Did not select ‘Often’ (n = 529): M | Did not select ‘Often’ (n = 529):SD | Selected ‘Often’ (n = 31): M | Selected ‘Often’ (n = 31): SD | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenge Planning | 3.31 | 1.50 | 5.08 | 1.54 | .001 | 1.18 |

| Rape Myth Acceptance | 2.75 | 1.15 | 3.96 | 1.35 | .001 | 1.05 |

| Hostile Sexism | 3.12 | 1.02 | 4.00 | 0.91 | .001 | 0.86 |

| Feelings of discrimination | 3.40 | 0.99 | 4.16 | 0.89 | .001 | 0.77 |

| Displaced Aggression | 2.34 | 1.14 | 3.23 | 1.45 | .002 | 0.77 |

| Political Belief (left-leaning) | 1.55 | 0.25 | 1.39 | 0.22 | .001 | 0.63 |

| Depression | 12.81 | 6.85 | 17.10 | 7.30 | .002 | 0.63 |

| Anxiety | 8.82 | 5.75 | 11.97 | 6.10 | .008 | 0.55 |

| Angry Rumination | 4.16 | 1.65 | 4.99 | 1.69 | .006 | 0.50 |

| Wider society are enemies | 3.83 | 1.11 | 4.29 | 1.13 | .027 | 0.48 |

| Incels engaged in last 2 weeksa | 10.68 | 7.08 | 14.04 | 7.78 | .039 | 0.47 |

| Political left are enemies | 3.91 | 1.11 | 4.29 | 1.04 | .043 | 0.34 |

Notes: aFor this item only, n was 355 and 24 for the two groups, respectively. Column p denotes statistical significance. If this value is < .05 then the groups can be considered different from each other for that characteristic. The final column denotes the effect size of the mean difference (Cohen’s d). This can be used to understand how big the difference is; d can be interpreted as follows: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large.

Summary and conclusion

This study has sought to better understand the experiences of individuals who self-identify as incels by surveying their psychological experiences; their adherence to ideology; and their social networks. Our study answers the call made by Hart and Huber (2023), who identified the need to engage with incels as human research participants. Given that this is the largest study of incels to date (n = 561), this study should be seen as a significant contribution to the topic, as well as the wider field of extremism and terrorism studies. Moreover, this is the first study to ask incels about their network activity and their feelings of support within it, complementing recent existing ecosystems research (Baele, Brace & Ging, 2023; Ribeiro et al., 2021).

This study found that the mental health of incels was typically very poor, with a high number reporting that they suffered from depression and had regular thoughts of suicide. They also reported a high degree of victimhood, anger and misogynistic attitudes. Furthermore, the findings point towards high levels of neurodiversity; around a third passed the cut-off for a medical referral in the autism spectrum questionnaire. When questioned about the incel ideology and their adherence to it, most agreed that there was a congruent worldview that was shared amongst members of the community. This includes identifying “feminists” as the primary out-group who they deemed responsible for their plight. Previous research has highlighted a potential overlap between the far-right and incels. However, our participants do not seem to have particularly strong political beliefs, leaning somewhat left. One cause for concern was the high levels of justification of violence amongst incels’ perceived enemies. When looking at how incels perceive and act within their community, the survey’s findings show that they, for the most part, feel it gives them a sense of belonging. They communicate in a range of different ways, with anonymous platforms (such as Chan boards) and pseudonymous platforms (such as more traditional forums) being the most popular. Interestingly we found that a surprising number of incels had communicated with like-minded individuals in the offline sphere, which goes somewhat contrary to the prevailing wisdom of incels as an online-only community.

Incels from the United Kingdom and United States of America were remarkably similar within this study. There were some expected demographic differences (such as a greater number of black and Hispanic incels in the US sample than in the UK), but for the most part, they answered questions similarly. The biggest differences were in the networking of incels; UK participants thought that their use of social networking gave them more support and was less likely to bring them in contact with radical online content than the US sample. We concluded our analysis by conducting a factor analysis to assess whether a “harm” factor (made up of angry rumination, revenge planning, displaced aggression, hostile sexism, rape myth acceptance and justification of violence) could be predicted by either the Needs, Narrative, or Networking of incels. We found that all three significantly predicted “harm”, demonstrating support for the 3N framework’s core thesis that a combination of these three factors plays a role in radicalisation.

Although it is vital to conduct more human participant research with incels, it should be noted that self-reported data is not without limitation; individuals can often misrepresent their answers either forgetting the truth (Tourangeau, 1999) or deliberately withholding it. This is particularly the case for questions that relate to the justification of violence, where “social desirability bias” may lead to people self-censoring (Krumpal, 2013). As such, this research should be seen as complementary to both content and ecosystems analyses. Triangulating research from several different perspectives will offer us the best hope of understanding the incel movement. Related to issues with self-reporting, and a strength of this study, was its rigorous screening process. To our knowledge, this is the only study of incels which required verification (by a third party with no access to their data) of their identity for payment. This allowed us to filter out a large number of false and duplicated results. These constituted around 15 percent of the total responses submitted and, if reprehensive, have important implications for previous research and any policy or political commentary that has been driven by previous research. Specifically, conclusions drawn from biased and inaccurate data could lead to a misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the incel community, both in terms of the variety of opinions within it and what proportion of incels pose a credible threat to themselves and others. Future research should strive to make their recruitment practices more rigorous. Those who are apprehensive about paying incels should consider the fact that not all incels have extreme views and that it would be ethically questionable to assume so and withhold compensation typically given to participants in psychology studies on that basis.

This research also provides an important contribution to preventing and countering violent extremism practice. The poor mental health of incels underscores the importance of taking a multi-pronged approach to interventions. The UK Home Office Prevent strategy (2018) involves offering the individual a support package tailored to their needs. When conducting such an intervention with incels, there should be psychosocial support available. Similarly, understanding the adherence to ideology plays an important role when conducting counter-messaging interventions. That only around two-thirds of individuals agreed with the 80/20 rule could suggest that there is some fragility to this belief that could reasonably be deconstructed by a credible messenger. Finally, understanding the online platforms that incels spend their time online helps intervention providers to meet them where they are.

CRediT author statement

Whittaker, J: funding acquisition, conceptualisation, data curation investigation, project administration, writing (original draft, review and editing). Costello, W: funding acquisition, conceptualisation, data curation, investigation, project administration, writing (original draft, review and editing). Thomas, A.G: funding acquisition, conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, investigation, project administration, writing (original draft, review and editing).

References

Al-Attar, Z. (2020). Autism spectrum disorders and terrorism: how different features of autism can contextualise vulnerability and resilience, Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 31(6), 926–949.

Allely, C. S. & Faccini, L. (2017). “Path to intended violence” model to understand mass violence in the case of Elliot Rodger. Aggression and violent behavior, 37, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.09.005

Allely, C. S., Wilson, P., Minnis, H., Thompson, L., Yaksic, E. & Gillberg, C. (2017). Violence is rare in autism: when it does occur, is it sometimes extreme? The Journal of Psychology, 151(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2016.1175998

Allison, C., Auyeung, B. & Baron-Cohen, S. (2012). Toward brief “red flags” for autism screening: The short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(2), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.11.003

Andersen, J. C. (2023). The symbolic boundary work of incels: Subcultural negotiation of meaning and identity online. Deviant Behavior, 44(7), 1081–1101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2022.2142864

Anti-Defamation League. (2023, July 29). Incels (Involuntary celibates) – Backgrounder. Available at: https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounder/incels-involuntary-celibates.