eNews Article: Managing fiscal risks openly and more effectively

Published 26 October 2018

Managing fiscal risks openly and more effectively

Responsible management of United Kingdom public finances is key to sustaining delivery of public services and strengthening the economy. This is a task involving many significant areas of uncertainty. The government has published a report detailing its approach for managing a broad range of these risks, setting a new standard for transparency and openness. We outline what has been achieved and consider some ideas for further progress.

What has been achieved?

The report, Managing Fiscal Risk: government response to the 2017 Fiscal risks (MFR), was published in July 2018 by HM Treasury. It represents the first completion of a new cycle of assessing and actively managing risks to the public finances. This cycle was set in motion in 2015 when Parliament approved a new requirement for the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to publish a comprehensive review of financial risks to tax revenues, public spending and the public sector balance sheet. They were also asked to conduct a stress test. This ‘what if’ analysis examines both immediate and longer term implications of a severe economic crisis on the United Kingdom public finances. The Government is required to respond to each review within a year of publication.

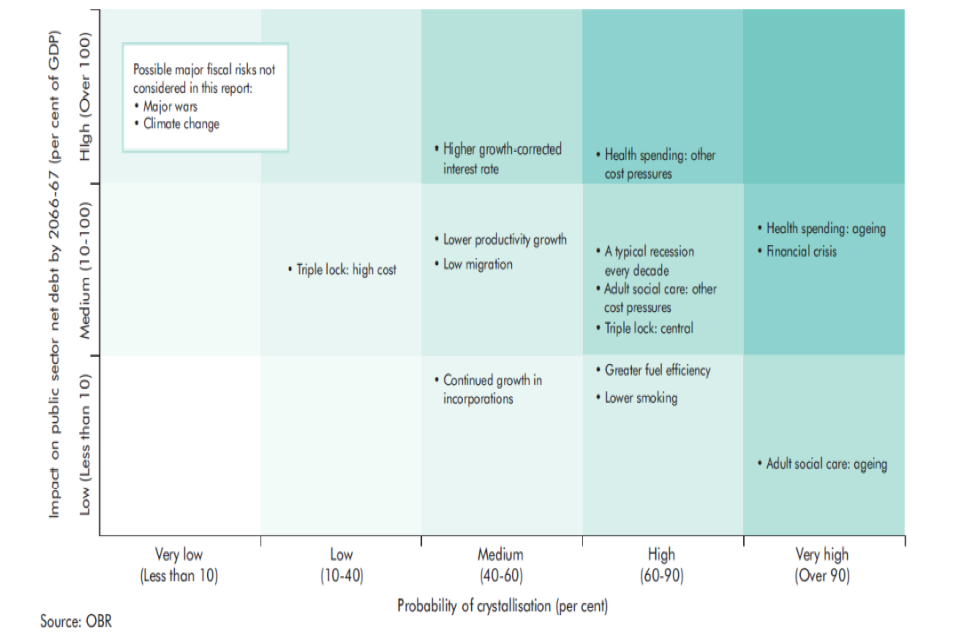

In its first Fiscal Risks Report (FRR) in 2017 the OBR identified 57 fiscal risks. Examples include the risk of future financial crises, increasing demand for health and social care, and changing tax revenues. The chart below summarises the subset of risks OBR identified as the main threats to long term fiscal sustainability.

The OBR’s report drew on, and developed, previous analysis of risks used to inform its other assessments and projections. The Government’s response sets out existing approaches to managing these risks and plans to proactively manage them in future.

Figure 1: Sources of risk to long term fiscal sustainability identified by the FRR

Why is proactively addressing fiscal risks important?

Public sector decision makers need to consider not only the most likely future outlook for the public finances, but also the likelihood and scale of impact of alternatives around the central forecast. Many of the risks and issues MFR considers are implications of, or can be influenced by, Government actions. Therefore public services can be more robustly delivered through proactively planning to limit or avoid the most significant possible adverse events and to increase exposure to future opportunities.

What can be improved further?

MFR has provided an unprecedented opportunity for parliamentary and public scrutiny, but also for analysts across government to better understand the full landscape of public finance risk management. It is the most comprehensive such public report in the world and sets a high standard among developed nations. That said, there is still scope for further development of the underlying analysis and reporting for subsequent iterations. For example:

- How accurate are the methods that are currently used to quantify risks and could they be developed further?

- Can they be used to assess the levels of both gross and net risk, i.e. before and after mitigating actions?

- How cost-effective are these mitigating actions?

- What is the highest acceptable degree of risk that the government can tolerate in a given area, and are mitigating actions sufficient to bring risk within this?

In practice the extent to which these questions can be sensibly answered will be limited in some cases, but even asking the questions may lead to additional insights into the risk management process.

Public sector balance sheet

One example of where these questions are particularly relevant is the public sector balance sheet. That is the government’s holdings of assets and liabilities. Risks can arise in a number of ways, from uncertainty around the returns from sale of assets (eg student loans), to sudden reclassifications that move substantial assets or liabilities on to or off the public sector balance sheet (both requiring extra care and management, for example National Rail). Many different measures can be considered, which vary in how and what they measure.

An area where improved analysis may be particularly helpful is the increasing range of financial government guarantees that may be called upon. Examples include “Help to Buy” mortgage schemes, and promises of support to pension schemes of former nationalised industries. GAD has been able to help departments which hold these contingent liabilities to address the questions above. This is an area in which work is continuing, including as part of the HM Treasury Balance Sheet Review.

“An area where improved analysis may be particularly helpful is the increasing range of financial government guarantees … ”

Considering interactions

The OBR FRR identifies that both its own and previous Government analysis is often focussed risk-by-risk, one issue at a time. Yet part of the challenge associated with many of these significant risk exposures is that in practice they are interlinked. For example, the ageing of the UK population both affects the cost of pensions provided by the government and also adds pressure to health and social care spending.

“part of the challenge … is that in practice [risks] are interlinked”

MFR outlines the government plans to manage each of these drivers of public spending increases, but their interrelationship can raise difficulties: the extent to which State Pension Age can be raised to realign the ratio of the working age population to those already retired depends on the success of efforts to ensure longer periods of life in good health. The latter is in turn an important theme affecting controlling health and care costs. Future analysis could be enhanced by developing methods to better capture the interactions between these risks.

Considering the context

This report considers high-level risks and the overall risk management framework. It is important also to ask how the framework facilitates the management of specific individual risks by the departments responsible. This is especially relevant where there are potential knock-on consequences elsewhere. For example, we might ask what risks the long-term decline of Defined Benefit pensions poses for future benefits expenditure. This issue will undoubtedly inform DWP policy development. How much analysis of the potential financial implications is it worth carrying out and what is the significance to the overall risks to future revenue and expenditure?

In some instances the existence of an exposure to risk is closely linked to the intent of government policy itself. An example is the risk of the State Pension triple lock adding to pension costs. Equal depth of analysis and management of these risks as for those with more incidental connection to policy is necessary for both effective policy decision making and robust delivery of these policies and consistent with further improving transparency and accountability.

However, we shouldn’t lose sight of the huge progress in openness and value of pulling all this information together in one place. We look forward to GAD’s ongoing participation in further enhancements of government’s financial risk management.