Education Policy

Updated 6 March 2018

A girl and her classmate read. Hidassie school, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. GPE/Midastouch

Foreword from the Secretary of State

Education has the power to change lives. It opens doors to better employment, more active citizenship and well-informed health choices which benefit future generations. At its best, it transforms the prospects of poor and marginalised children and builds more meritocratic societies.

International Development Secretary Penny Mordaunt. Russell Watkins/DFID

Developing countries have made huge strides in expanding schooling in recent decades, so that most children are now able to access primary education.

I am proud that the UK has contributed to this impressive achievement. Between 2011 and 2015 we supported over 11 million children, including in some of the toughest places in the world.

The global focus must now be on improving the quality of education to ensure children are learning the basics. Over 90% of primary-age children in low-income countries and 75% of children in lower-middle income countries – around 330 million children – are not expected to read or do basic maths by the end of primary school. These statistics are truly shocking and demand urgent action.

Together national governments and international partners must tackle the learning crisis at its root and ensure that children are getting the best start which they can build on through future education and employment.

Business as usual will not achieve the transformative change that is needed. We must join forces to drive a new approach to fundamental education challenges.

As a global leader on education, Britain will throw the full weight of its support behind this effort, bringing our influence, expertise and finance to the table.

Our top priority will be raising the bar on teaching quality. We know that good teaching is vital to children’s progress. Yet many teachers lack the knowledge and skills to do their jobs well. Too often, they are absent from the classroom, meaning that precious resources go to waste and the potential of their students is unfulfilled. Of course, there are many examples of highly skilled, reliable teachers all over the world. But we need this to be the norm everywhere. We will support national leaders ready to take a fresh look at how their workforces are recruited, trained and motivated, so that they can make the bold changes that are needed.

Teachers can’t succeed alone, so we will support ambitious reform to make education systems – across public and non-state sectors – more accountable, effective and inclusive of poor and marginalised children.

We will help education systems stand on their own two feet, cutting waste and using public resources effectively to support children’s progress. If we determine that a country could contribute more towards its own education, we will expect it to do so. We will support governments to improve their public finances and tax systems in order to fund good quality education.

In all our efforts, we must ensure that poor and marginalised children are not left behind. The UK will show new leadership on education for children with disabilities – and maintain the pressure to deliver for children affected by crises. We will continue to champion hard-to-reach girls, promoting 12 years of quality education and learning and improving the prospects of the large numbers who do not go on to secondary school. We will also call for global action to end violence in schools, which contributes to school drop-out.

I know that many of the challenges which hold back progress on learning are highly entrenched in education systems and that achieving change will be difficult. But there is no alternative if we are to bring an end to the learning crisis – so we are up for the challenge.

Wherever you go in the world, you find children with dreams for the future and parents invested in their success. It is our responsibility to ensure that they have the opportunity to make the most of their talents and fulfil their potential. This will not only help us in our mission to tackle poverty. It is in the national interest and will provide a more prosperous and stable world for us all.

Penny Mordaunt

Secretary of State for International Development

Key messages

Education is a human right which unlocks individual potential and benefits all of society, powering sustainable development. Each additional year of schooling typically results in a 10% boost in earnings[footnote 1] and human capital underpins national growth. Gains in girls’ education deliver large health benefits, as educated women have fewer children, speeding the demographic transition, and their children are healthier. [footnote 2] Those with more education tend to be more politically engaged and active in seeking improvements to public services[footnote 3]. Education contributes to stability through building a sense of shared identity and strengthens resilience by helping people adapt to shocks[footnote 4]. UK investment in education overseas therefore delivers against the UK aid strategy and is firmly in the national interest.

Education systems in developing countries have expanded schooling at an impressive rate in recent decades, but there is now an urgent need to drive up quality and learning. Over 90% of primary-age children in low-income countries and 75% of children in lower-middle income countries – more than 330 million children – are not expected to read or do basic maths by the end of primary school[footnote 5]. This is a tragic waste of human potential, holds back development and poses risks to stability. It is also an enormous waste of public resources, with low- and middle-income countries estimated to spend 2% of GDP on education which does not lead to learning[footnote 6]. In low-income countries this is equivalent to around half of the education budget[footnote 7].

Education systems in many developing and conflict-affected countries do not incentivise progress on basic literacy and numeracy. Domestic finance is heavily skewed towards higher levels of education. On average, 46% of public education resources in low-income countries are allocated to the 10% most educated students[footnote 8]. Often, curricula are aimed at high performers, textbooks are too difficult for most children to read and exams only test higher levels of learning. Schools and teachers are frequently judged on how many children pass these high-level exams, rather than how many children achieve basic literacy and numeracy[footnote 9].

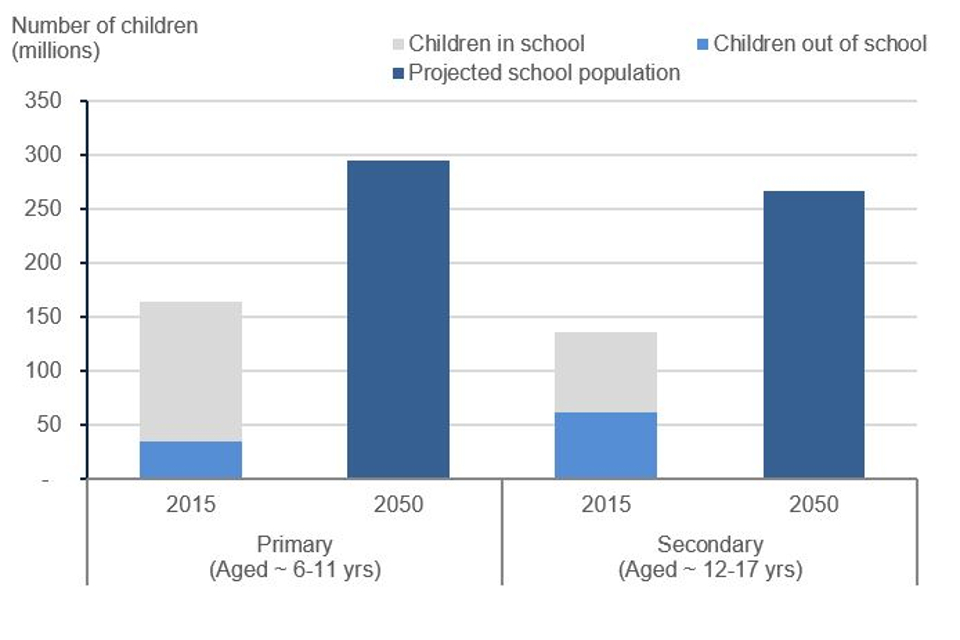

Pressure on vulnerable education systems is growing. In sub-Saharan Africa, there will be 250 million more primary and secondary school aged children by 2050[footnote 10]. The dual effort to boost quality while also expanding access will pose formidable delivery and fiscal challenges for these countries.

Business as usual will not deliver the transformational change that is needed. We are calling for a strong and united push by global and national leaders to drive up education quality and learning, focusing on new approaches to fundamental education challenges.

Our response will focus on tackling the learning crisis at its root by supporting children to learn the basics of literacy and numeracy, as well as transferable skills. This will be our main contribution to achieving the vision set out in Sustainable Development Goal 4 of inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong opportunities for all. We call on all countries facing a shortfall here to take urgent action, ensuring that poor and marginalised children – who face the greatest challenges – are not left behind.

We will focus on 3 priorities:

-

Invest in good teaching: Teaching quality is the most important factor affecting learning in schools, but many teachers in developing countries lack the knowledge and skills to do their jobs well and too often they are absent from the classroom. This means precious resources wasted as education systems also tackle a significant shortfall in teacher numbers. We will make good teaching our top priority, working with decision-makers ready to take a fresh look at how they train, recruit and motivate teachers. We will support teachers to use teaching strategies proven to work well for poor and marginalised children and to protect children from violence at school. We will work with teachers’ unions and wider stakeholders who can support teacher reform efforts and use our multilateral influence to ensure that good teaching remains an international priority.

-

Back system reform which delivers results in the classroom: To give teachers the best chance of success, we will support complementary education system reform across public and non-state sectors which helps make education systems more accountable, effective and inclusive. We will lend our full support to national decision-makers committed to improving learning, including through access to UK expertise. We will support efforts to cut waste and use public resources more effectively to ensure children learn the basics. Improvements in public financial management and taxation will be vital to ensuring adequate domestic resources for education, setting education systems on a sustainable footing. Where there is no national leadership to turn things around, we will look beyond stagnant public sectors, instead promoting improved transparency, accountability and coalitions seeking better education and investing through alternative channels which deliver for poor and marginalised children.

-

Step up targeted support to the most marginalised: Alongside investments to improve the overall quality of education, we will continue to help some of the world’s most marginalised children to learn, focusing on three priority groups. We will show new global leadership on education for children with disabilities, ensuring that larger numbers can transition into mainstream education and learn. We will support children affected by crises to continue to learn during long periods of disruption through multi-year investments in quality, safe education, calling on others to join us. We will maintain our commitment to improving the future prospects of hard-to-reach girls, supporting them to complete 12 years of quality education and learning wherever possible. We will also invest in improving the life chances of those who do not go on to secondary school – more than half of all girls in low-income countries[footnote 11] – recognising that the barriers to their educational progress will take time to overcome.

We will drive this ambitious agenda forward through strong leadership on the world stage. We will use UK influence to shine a light on the needs of the world’s most marginalised children and we will call for global action to end violence in schools. We will seek improvements in the international system of support for education, working towards better coordination across diverse multilateral and bilateral actors, including humanitarian and development actors in crises. We will advocate for greater international ambition on driving up education quality, particularly strong support for good teaching. We will promote more and better spending on education, working with international partners to ensure affordable finance is available to developing and conflict-affected countries committed to improving learning. We will continue to invest in high quality education research to ensure investments are based on robust evidence.

The case for action

Education is a human right, which unlocks individual potential and benefits all of society, powering sustainable development.

The wide-ranging benefits of investing in education are clear, deliver against the UK aid strategy and serve the national interest:

- boosts earnings and underpins growth: Education offers a great return for individuals – each additional year of schooling typically results in a 10% boost in earnings, with larger increases for women[footnote 12]. Nationally, human capital is one of the ingredients of growth

- supports better health choices, benefiting future generations: Educated women have a better understanding of healthy behaviour and are more empowered to act on that knowledge. They have fewer children, speeding the demographic transition, and their children are healthier and more educated[footnote 13]. Spending an additional year in secondary school can lower the risk of HIV infection among students by around a third a decade later[footnote 14]

- helps institutions and public services work better: Those with more education tend to be more politically engaged, trusting and tolerant and active in seeking improvements to public services[footnote 15]

- builds social cohesion and resilience: Education plays a powerful role in building a sense of shared identity, although it can also be misused to sow division[footnote 16]. Education builds skills which help people adapt to unexpected economic or political shocks, strengthening resilience[footnote 17]

Developing countries have expanded schooling at an impressive rate in recent decades. The average adult in 2010 had completed 7 years of school, compared to only 2 in 1950[footnote 18]. Most children are now able to access basic education[footnote 19].

Yet education systems in developing and conflict-affected countries are not consistently delivering quality education, leading to a learning crisis. This is a tragic waste of human potential which is holding back development and posing risks to stability.

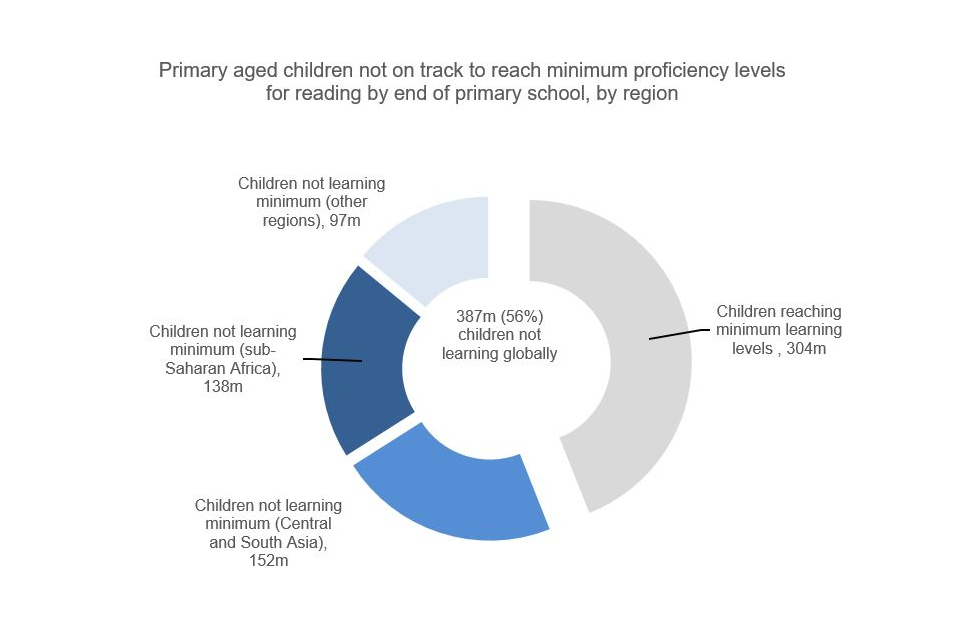

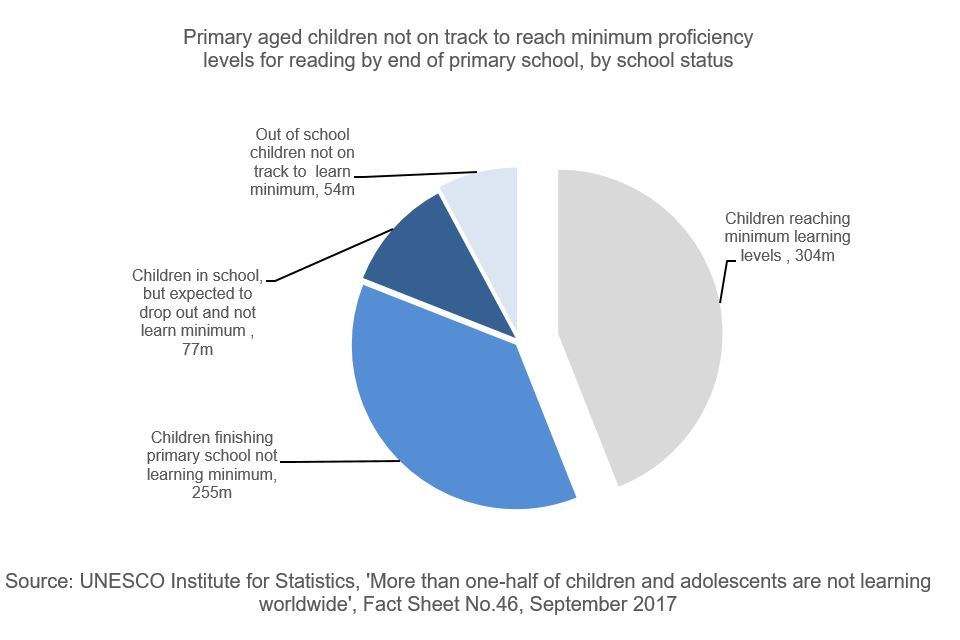

Learning levels are low: Over half the world’s children – around 387 million – are not on track to read by the end of primary school (figure 1)[footnote 20]. This translates to over 90% of children in low-income countries and 75% in lower-middle income countries.

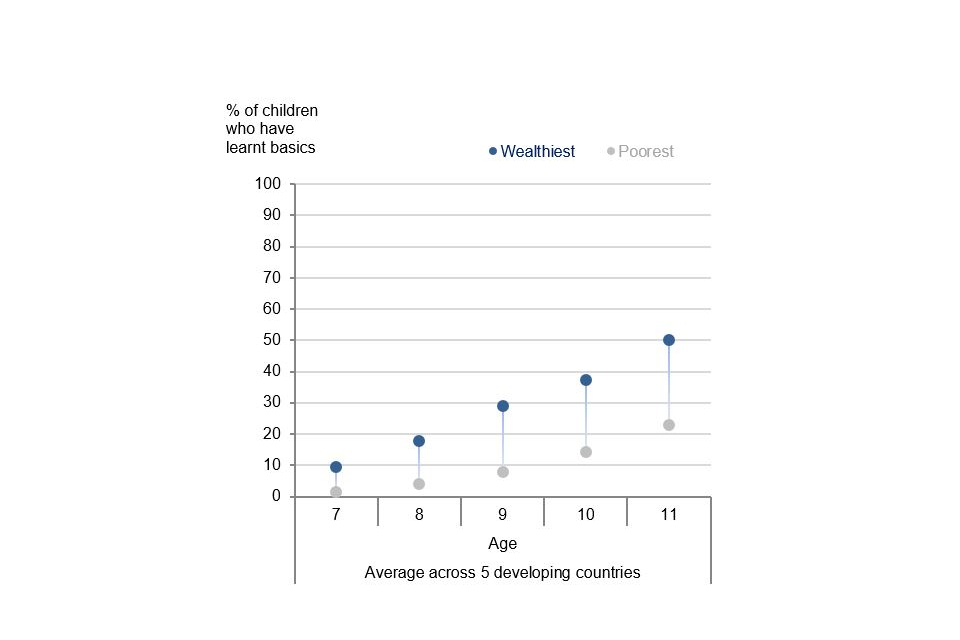

There are huge inequalities in learning: Learning inequalities between rich and poor students begin early and grow wider over time (figure 2)[footnote 21]. They are compounded by other sources of disadvantage, such as gender[footnote 22], disability, ethnicity and location[footnote 23]. There is often little support once children fall behind[footnote 24].

Barriers to access persist: Up to 50% of children with disabilities are out of school[footnote 25] and girls frequently drop out of school due to violence[footnote 26], pregnancy or child marriage[footnote 27]. Many children have to work to support their family’s income, which can limit opportunities to attend school[footnote 28]. Children in conflict-affected countries are one third less likely to complete primary school[footnote 29] and less than 2% of humanitarian aid went to education in 2015[footnote 30].

Figure 1: More than half of the world’s children (387 million) are expected to finish school without being able to read, most in school and in Africa and Asia

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, ‘More than one-half of children and adolescents are not learning worldwide’, Fact Sheet No.46, September 2017

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, ‘More than one-half of children and adolescents are not learning worldwide’, Fact Sheet No.46, September 2017

Wealth disparities in basic learning amongst primary aged children in five developing countries

Source: Rose, P. and Alcott, B. 2015. How Can Education Systems Become Equitable by 2030? Learning and Equity. Based on ASER India data.

Note: Learning the basics captures children who can read a story and do division. The average is based on data from rural India, rural Pakistan, Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. There is no data for 7 year olds in Tanzania or 11 year olds in rural Pakistan.

Demographic pressure is rising: The population of sub-Saharan Africa is expected to double to 2 billion by 2050. There will be 250 million more primary and secondary school-aged children, which represents a 90% increase (figure 3)[footnote 31]. Vulnerable education systems will come under enormous strain to boost quality while accommodating growing numbers of students[footnote 32].

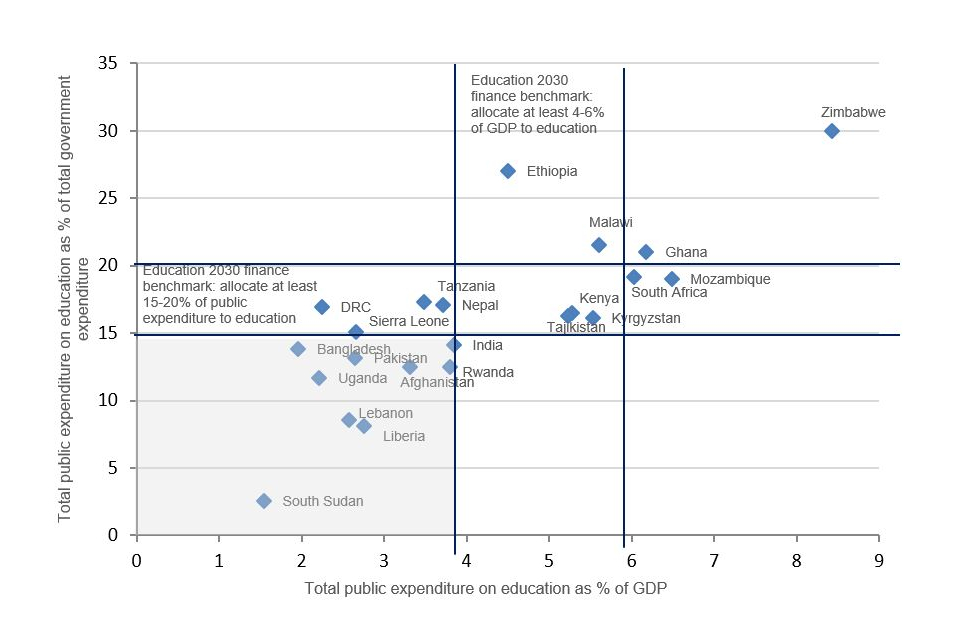

More investment is needed: In 2015, 17% of spending in low-income countries and 16% in lower-middle income countries went to education – a large share of public resources[footnote 33]. Yet many countries fall short of targets for public financing of education set in the Education 2030 Framework for Action (figure 4)[footnote 34]. To achieve global education targets it is estimated that developing countries will need to increase annual public expenditure from $1 trillion in 2015 to $2.7 trillion in 2030 (from 4 to 5.8% of GDP), alongside international and private sector investment[footnote 35].

Money does not always hit the target: Waste is high, with developing countries estimated to spend 2% of GDP on education costs which do not lead to learning[footnote 36]. In low-income countries this is equivalent to around half of the education budget[footnote 37]. This unproductive spending goes to teaching and other inputs for students who are not learning basic literacy and numeracy. This can lead to further waste higher up the system, where students continue in their education and require costly remedial support to address this gap.

Greater national and global ambition is needed to get children learning – and ensure education is realising its full potential for development.

Figure 3: Vulnerable African education systems will be under pressure to keep up with population growth

Source: DFID estimates from UNESCO Institute of Statistics and UN Population Division data, December 2017.

Figure 4: Governments devote a substantial share of their budgets to education, but many fall short of international benchmarks

Public expenditure on education as a share of GDP and of total expenditure for focus countries, 2015 or most recent year

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics database, January 2018.

Approach: Tackling the learning crisis at its root

Our objective

We are committed to the vision set out in Sustainable Development Goal 4 of inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong opportunities for all.

A boy raises his hand in class, Burundi. UNICEF Burundi/Colfs

Our mandate to end extreme poverty means that our main objective will be ensuring children learn the basics of literacy and numeracy, as well as transferable skills (such as problem-solving, communication and creativity)[footnote 38], tackling the learning crisis at its root.

We call on all countries where children are not learning these foundation and transferable skills to take urgent action.

The case for doing so is clear:

- essential for individual progress: without a strong foundation, children will struggle to progress to higher levels of education or productive employment[footnote 39].

- good for growth: widespread, good quality primary and lower secondary education is considered to be important for growth in low- and middle-income factors, and middle-income countries [footnote 40]. This relationship is not automatic – it depends on many other factors, including the strength of a country’s institutions[footnote 41].

- benefits poor and marginalised children: Intervening early is vital to reducing the learning gap between rich and poor students which sets in rapidly and widens significantly over time (figure 2)

Our priorities

We will draw on the full range of UK resources – our expertise, influence and finance – to deliver against 3 priorities which together will boost education quality and improve equity:

-

Invest in good teaching: We will make driving up teaching quality our first priority and work with decision-makers ready to take a fresh look at how they train, recruit and motivate teachers and support staff. We will support teachers to use teaching strategies proven to work well for poor and marginalised children and positive discipline.

-

Back system reform which delivers results in the classroom: We will lend our full support to national decision-makers committed to improving learning to make education systems more accountable, effective and inclusive, including through access to UK expertise.

-

Step up targeted support to poor and marginalised children: Alongside investments to improve the overall quality of education, we will continue to help some of the world’s most marginalised children to learn, focusing on three priority groups: children with disabilities, hard-to-reach girls and children affected by crises.

A strong focus on primary and lower secondary education

Our choices about which level of the education system to engage and support will be driven by our main objective of ensuring children learn the basics, but will remain flexible to respond to wider development objectives and needs in the diverse contexts in which we work. These include low- and middle-income countries where the learning crisis is most acute, as well as middle-income countries tackling inequalities, managing the challenges of regional conflict or looking to education to better underpin growth (see annex 1).

Across the portfolio we anticipate:

- our main focus will remain on primary and lower secondary education, given our objective of ensuring children learn the basics of literacy and numeracy, as well as transferable skills

- we will build on our current engagement in pre-primary education, in recognition of its role in preparing children for the classroom and securing foundation skills. Our support will be research-led, helping countries to identify cost-effective, scalable approaches and sharing lessons learned from UK experience (box 1)

- we will continue to make strategic interventions in upper secondary, skills for employment (box 15) and higher education (box 11). We will take into account progress in improving the quality of primary and lower secondary education, national financing gaps and where the greatest political opportunities for reform lie. We will consider how far investments contribute to wider development objectives, such as improving the prospects of poor and marginalised children and youth, unlocking constraints to growth, strengthening public services and governance and meeting humanitarian needs and reducing conflict

- we will promote 12 years of quality education and learning for hard-to-reach girls, supporting them to make the critical transition to lower secondary school and, wherever possible, to complete secondary education or training. We will also invest in improving the life chances of those who do not go on to secondary school – more than half of all girls in low-income countries[footnote 42]

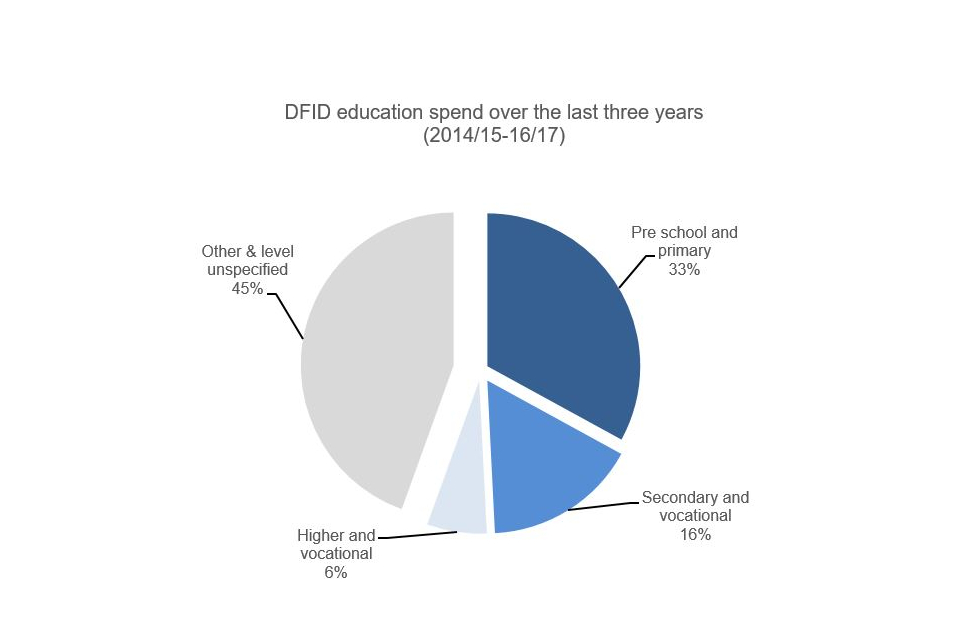

Figure 5: The largest share of our support goes to primary and lower secondary education

Source: DFID analytics, January 2018

Note: Most other and level unspecified spend consists of contributions to education multilaterals (primarily the Global Partnership for Education) and spending on management, facilities, training and research. Much of this is focused on primary education.

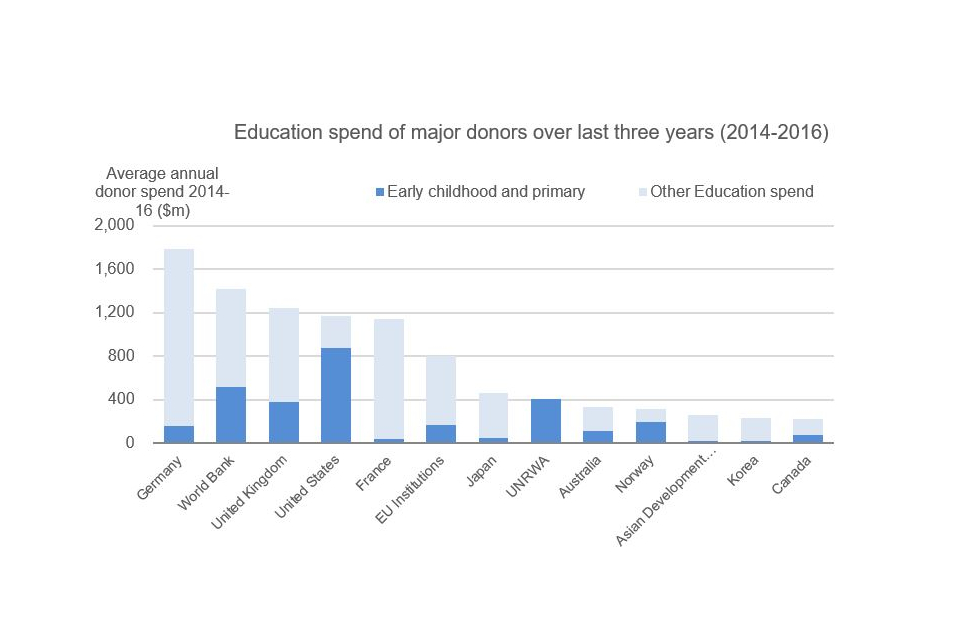

Figure 6: The UK is one of the largest donors to education, particularly at primary level

Source: OECD CRS database. 2015 constant prices.

Note: Includes all donors with education spend over $200m in 2016. As noted above, the UK also has a large volume of funding which is unspecified to a particular level (38%), much of which focuses on primary education.

Box 1: Investing in the early years

Good quality early years education (from birth to age 8) provides the best possible foundation for a child to learn in school, leading in adult life to higher earnings and success in the labour market[footnote 43]. In many developing countries, children from poor and marginalised households quickly fall behind and experience growing levels of learning inequality over time (figure 2)[footnote 44].

We have been investing in research on how to deliver good quality early years education, working with the World Bank’s Early Learning Partnership and the British Academy. We already support children in the early years of primary education, including the important transition into primary school. We will build on this by gradually expanding our research-led approach where there is government and parental demand. Investing in good teaching across both pre-primary and the early years of primary school will help improve the efficiency of the whole education system, reducing high repetition and drop-out rates at the outset of primary school. This will depend on good quality provision.

We will:

- enable governments to identify cost-effective, scalable early education interventions, prioritising highly marginalised groups such as children with disabilities

- share UK expertise on how government can ensure better quality pre-primary education by non-state providers and how to develop children’s early language skills

- extend UK support for improving the supply of skilled and motivated teachers to pre-primary education

A holistic approach to early childhood can achieve significant impact in developing countries, particularly during the most critical stage of a child’s brain development – before birth and during the first few years of life. Through our nutrition investments, we support governments to ensure that children get the basic nutrients they need in the first 1,000 days. We know that where this happens, children on average complete 4.6 more grades at school and earn 21% more as adults[footnote 45]. Where possible, we will integrate early education interventions within our complementary investments in nutrition – as well as women’s economic development, social protection and maternal and new-born health.

Building on UK strengths and working in the national interest

In delivering these priorities, we will build on UK strengths:

- UK expertise in education, including world-class teaching and research institutions, the British Council and strong public sector organisations, which can be deployed to support decision-makers seeking to drive up the quality of teaching and strengthen education systems

- a network of trusted in-country advisers, which will support governments to deliver on challenging reform

- established global leadership on reaching the most marginalised, particularly hard-to-reach girls and children in crises, which we can build on to deliver impact for children with disabilities

We will combine efforts across government to ensure UK support for education delivers against the UK aid strategy and is firmly in the national interest. Our support for education will also contribute to broader government objectives such as developing UK trade and investment opportunities in education sectors overseas and strengthening UK influence.

Our vision for change

Poor and marginalised children learning and fulfilling their potential

We will help ensure millions of poor and marginalised children around the world, whether in the public or non-state sector, learn literacy, numeracy and transferable skills, significantly improving their life chances. Hard-to-reach girls, children with disabilities and children affected by crises won’t be left behind – they will be learning and progressing onto further education or jobs.

Teachers supporting children to learn and prosper

Governments will tackle the fundamental challenge of teacher reform, navigating the challenging politics to improve teachers’ skills and motivation from a low base and meet future demand. Teachers will be supported to adopt strategies which work for poor and marginalised children and help combat violence in schools.

National governments turning the tide on the learning crisis

Successful partnerships between the UK and developing country governments committed to driving up education quality will demonstrate how it is possible to accelerate progress on learning outcomes. Together, we will reach out to a wider group of countries to show how improvements in teaching quality and system performance make a difference.

International system tackling barriers to progress at national level

Global partners will come together in a unified push to transform teaching and improve learning outcomes at country level, and reach the most marginalised children. Together, we will mobilise new affordable finance for education and address pressing financing gaps, particularly for the most marginalised children.

UK expertise making the difference

Our ‘Best of British’ offer on education will facilitate greater access to relevant UK expertise. We will ensure our national partners secure the best possible advice to address the critical policy challenges they face, enabling more inclusive education, better teacher professional development, school leadership and inspection and more effective public-private partnerships and use of education technology.

Shifting accountability for learning

We will hold ourselves – and others – accountable for making progress on teaching and learning. We will introduce a new headline indicator on whether children are learning, which will be reported across our portfolio, and new approaches to ensure all relevant programmes are measuring teaching quality. We will champion greater availability, use and transparency of data on learning, teaching and equity by all of our partners. This shift will be challenging initially due to limitations in current data, but will become easier as the effort to improve measures of learning bears fruit.

Invest in good teaching

Why focus on good teaching?

Teaching quality is the most important factor affecting learning in schools[footnote 46], but ensuring that every child is taught by a skilled and motivated teacher is a huge challenge for developing and conflict-affected countries.

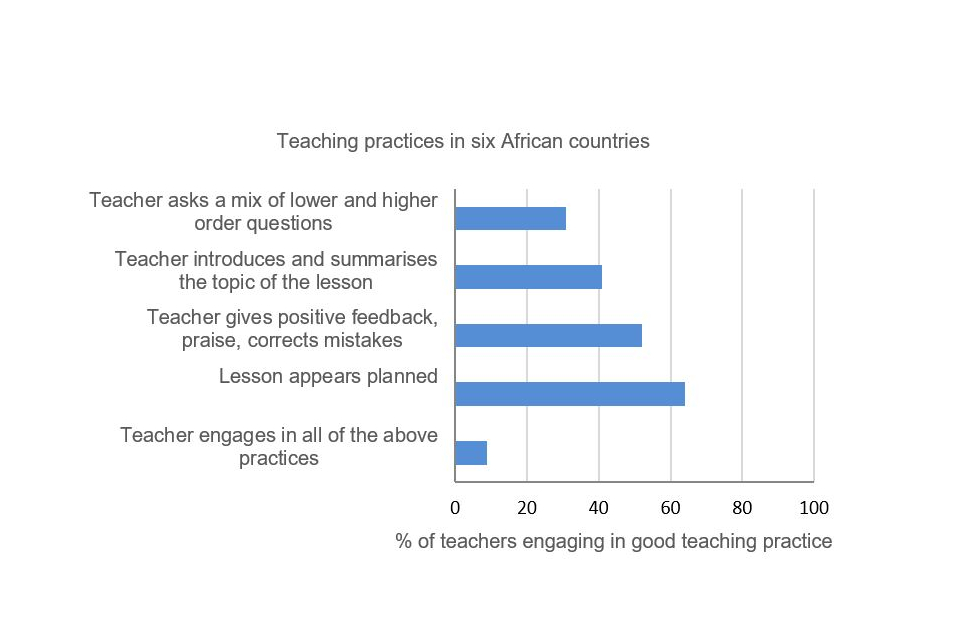

Teachers lack the basic knowledge they need to do their jobs. In 7 African countries, a third of primary teachers had not mastered their own students’ literacy curriculum and less than 10% met a higher bar of minimum knowledge expected for their role[footnote 47].

Teachers also lack good teaching skills. Across the same set of African countries, teachers did not demonstrate good practices such as lesson planning, checking for understanding and assessing student learning (figure 8)[footnote 48]. Too often, teachers in developing and conflict-affected countries depend on didactic approaches which encourage rote learning rather than critical engagement[footnote 49].

Teachers are not incentivised to ensure all children are learning the basics. Many education systems are dominated by high-stakes exams which only a few high achievers pass, skewing teachers’ focus towards this group and away from those struggling to make progress.

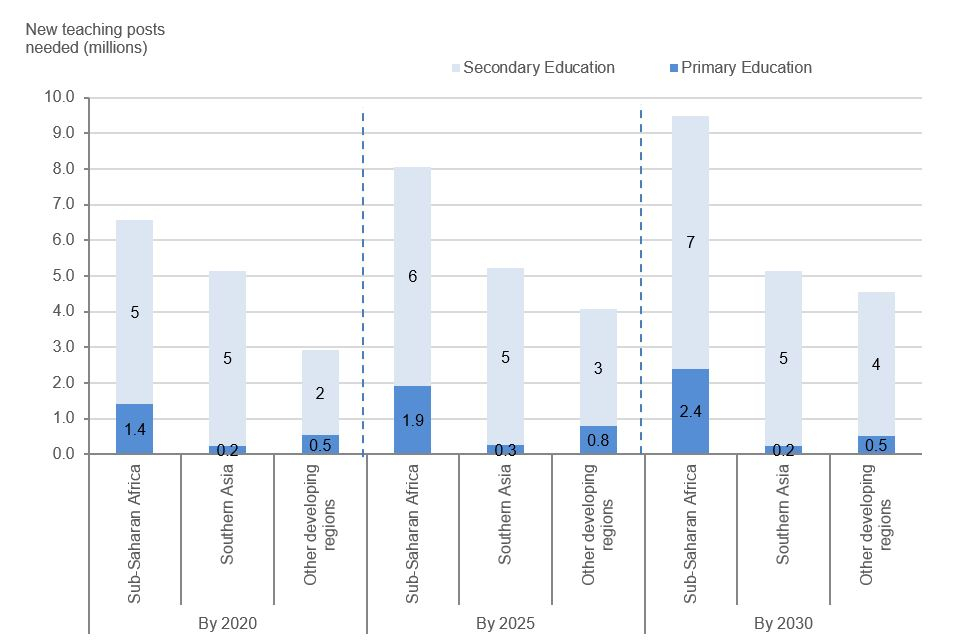

There are too few teachers. By 2030, countries must recruit a total of 69 million teachers in order to achieve education for all children, 24.4 million at primary level and 44.4 million at secondary level. This includes an additional 20 million teachers to fill new teaching posts required to reduce class sizes and meet population increases[footnote 50].

Teachers are not present where they are needed most. Too few teachers are deployed to remote areas and to the critical early years of primary school[footnote 51]. Teacher absenteeism remains a major challenge and one which carries high costs, as teacher salaries absorb three-quarters of the primary education budget in developing countries[footnote 52]. In India, teacher absenteeism is estimated to cost $1.5bn a year[footnote 53].

Teachers too often rely on corporal punishment. In 73 states corporal punishment is still not fully prohibited in places of learning[footnote 54]. Teachers have an important role to play in reducing other forms of school-based violence, such as sexual violence and bullying.

Teachers are themselves products of a failing system[footnote 55]. Many countries are caught in a vicious cycle, in which poorly educated students become teachers who then lack the necessary skills to get children learning. Teachers often face tough working conditions – oversized classes, poor infrastructure, long working hours and administrative and social duties beyond the classroom. In many countries, teacher pay is in decline and those in remote and rural areas often have to travel long distances to collect salaries. Many teachers take on additional jobs to support their families. Professional career paths are often lacking and professional support is weak. Thus teacher failures are both a cause and a symptom of failing education systems which can only be tackled through strong leadership from national to school levels.

Figure 7: The world needs another 20 million additional teaching posts to achieve universal primary and secondary education by 2030

Number of new teaching positions needed to achieve universal primary and secondary education by 2030

Figure 8: Teachers in six African countries do not consistently demonstrate good teaching skills

Note: Results are the average of six countries: Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda. Based on survey of teaching practices in government schools in Grade 4.

Our approach

We will support decision-makers in developing and conflict-affected countries who are ready to tackle the fundamental challenge of teacher performance head on, taking a fresh look at what kind of workforce they will need in the future, and exploring new approaches to training, recruitment and motivation of teachers and other staff. We will engage the full range of stakeholders in teacher reform, including teachers’ unions, the non-state sector, wider national stakeholders, international partners and UK experts.

A teacher in Cameroon, where programmes to improve hiring, retention and deployment of teachers have been implemented. GPE/Stephen Bachenheimer

Securing teacher reform will be politically challenging for national decision-makers. It will often require long negotiation with influential teachers’ unions which have the capability to mobilise at national scale should they oppose reform. Politicians who rely on teachers’ political support face difficult trade-offs in negotiating improvements in cost-effectiveness and accountability[footnote 56].

Yet without improvements to teaching quality, countries cannot make progress on driving up learning.

We will support national efforts to:

Overhaul out-dated models of teacher training, drawing on evidence-based approaches to improve teachers’ skills which deliver for children, including those who are poor and marginalised.

Teacher training is critical to ensuring teachers teach well, particularly in countries with weak education systems where many candidates start with a deficit in foundation skills. However, much teacher training in developing and conflict-affected countries remains ineffective: research tells us that it is often too theoretical, delivered by trainers without practical experience and not sustained over time.

We will support uptake of the following evidence-based approaches for quality teacher training, recognising that they will be implemented differently across contexts:

- practical experience in the classroom and ongoing school-based support, instead of one-off theoretical training

- assessment of teacher knowledge and performance rather than reliance on credentials, backed by intensive remedial interventions where teachers fall short of minimum standards. We will support decision-makers to explore the potential of education technology to enable delivery of remedial education at scale, as part of a blended learning approach which also includes face-to-face support.

- teaching strategies proven to work well for poor and marginalised children, such as teaching at the right level for each student through an interactive approach, regular assessment and where practical teaching in small groups, rather than focusing on the best performers or sticking rigidly to curricula that are too advanced for many students[footnote 57]. We will also support education systems to ensure that a growing number of teachers have the skills and resources to support poor and marginalised children, including hard-to-reach girls, children with disabilities and children affected by crises. This includes developing the teaching workforce so that it reflects the diverse cultural and linguistic groups present in a country, enabling children to be taught in a familiar language[footnote 58] and ensuring those teachers are willing and able to challenge discriminatory social and gender norms

- high quality teaching materials, including open digital resources customised for different contexts, accessible via mobile phone

Box 2: Teacher training in Ghana and Bangladesh

The Transforming Teacher Education and Learning (T-TEL) programme in Ghana has worked with teacher training colleges to transform the delivery of initial teacher education. With our support, the Government of Ghana has endorsed an ambitious agenda of teacher training reforms which include introducing national standards for initial teacher education and a curriculum framework.

English In Action (EIA) is a professional development programme reaching over 50,000 teachers and almost 8 million students in Bangladesh. Teachers are guided by short videos of simple teaching techniques, available on their mobile phones. They complete initial training on pedagogy, using the videos to learn by doing, reflecting, and sharing with peers, and receive ongoing support. As mobile phone use has increased, costs have decreased, and reach has expanded to more rural communities. The results are impressive - after a year, students’ ability to communicate using a basic level of English rose from 36 to 70%[footnote 59].

Boost motivation through rethinking recruitment and professional support and incentives.

Improved teaching skills – while essential – will not be enough. National decision-makers will also need to rethink how to boost motivation and reduce absenteeism through better recruitment and professional support and incentives.

We will support them to:

- shake up recruitment practices. One powerful channel for boosting teaching quality is through recruitment which brings new capable and motivated people into the profession. Where the supply of candidates with relevant skills is very low, the best way forward may be to recruit candidates with the capacity to learn and develop, who are willing and able to work in under-served remote areas[footnote 60]. Introducing professional support staff could play a critical role in helping the most marginalised students, including children with disabilities, to learn[footnote 61]

- reset professional support and incentives. Teachers often struggle with poor working conditions and are neither rewarded for good performance, nor penalised for poor performance. Straightforward salary increases are costly and often fail to achieve impact on learning, but performance-based financial incentives can provide an immediate boost to performance in some contexts[footnote 62]. Over the long-run, decision-makers can make gains through building a professional culture, developing career pathways and improving working conditions[footnote 63]. Effective school leadership by head teachers can have a real impact on teacher motivation, by setting learning goals for marginalised children and expectations for teacher performance, while helping teachers solve problems[footnote 64]. Stronger leadership is likely to depend on achieving wider improvements to accountability (see priority 2 below)

Box 3: Teacher reform in Lebanon and Nigeria

In Lebanon, a lack of private sector jobs has led to political and economic pressure to create and distribute public sector teacher jobs, resulting in a low pupil-teacher ratio and a high wage bill. With our support, the Government of Lebanon is ensuring all teachers meet national performance standards and is reviewing the financial sustainability of the teacher wage bill.

In Nigeria, state governments assessed primary school teachers’ competencies and found very low levels of knowledge and teaching skills. Federal and state leaders are engaging with teachers’ unions and, with our support, taking decisive action to address the quality of the education workforce: improving the quality of initial teacher education, establishing new systems for ongoing teacher professional development and revising teacher recruitment and deployment processes.

Work in partnership with teachers to reduce school-based violence.

Children learn best when they are free from the fear of violence[footnote 65]. Teachers play a role in school-based violence through use of corporal punishment and some perpetrate wider emotional, physical and sexual violence against children[footnote 66]. At the same time, teachers are essential partners in establishing schools as protective spaces where children can learn safely.

We will work with national decision-makers to:

- improve laws, policies and practices to keep children safe

- ensure that teacher training promotes positive discipline as an alternative to corporal punishment

- scale up our support for reducing school-based violence through our education portfolio, learning from whole-school approaches to tackling violence, which we have previously supported in Uganda through the Girls’ Education Challenge[footnote 67]. and in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Kenya through the What Works to Prevent Violence research and innovation programme[footnote 68]. This approach looks beyond corporal punishment to wider school violence, such as bullying and sexual abuse. It requires working closely with teachers as partners in a process of change, but also with school leaders, parents and children, local government and community leaders to promote alternative practices and norms

Back system reform which delivers results in the classroom

Why focus on system reform?

Teachers cannot succeed alone. Skilled teachers won’t be deployed effectively or stay motivated for long if wider education systems aren’t working well. Complementary education system reform across public and non-state provision is essential to their success.

Many education systems remain focused on getting more children into school, rather than improving quality and learning[footnote 69]. Reform is needed to shift the central focus of education systems to ensuring children learn, starting with the basics.

System incentives to ensure poor and marginalised children are learning the basics are weak. Domestic finance is heavily skewed towards higher levels of education. On average, 46% of public education resources in low-income countries are allocated to the 10% most educated students[footnote 70]. Often, curricula are aimed at high performers, textbooks are too difficult for most children to read and exams only test high learning levels. Schools and teachers are ultimately judged on how many people pass these high-level exams, not learn basic literacy and numeracy[footnote 71]. Parents of poor and marginalised children are often not well-organised for collective action and have limited influence relative to other powerful stakeholders[footnote 72]. To deliver on quality and learning, these incentives will need to change.

Many education systems lack coherence, with inputs, people and processes pulling in different directions[footnote 73]. Reform is needed to improve alignment around the common objective of ensuring children learn.

Box 4: What is an education system?

An education system covers the full span of education provision across both public and non-state sectors. It is made up of inputs, processes, people and politics, which together determine whether children are learning.

- inputs: The basic resources for education delivery, such as teachers, classrooms and textbooks

- processes: The ways in which these resources are put to use, including through standard setting and management of finances, information and the workforce

- people: The full range of people and organisations involved in education, including students, teachers, parents, bureaucrats, politicians and members of civil society organisations, who have different motivations and incentives

- politics: The over-arching governance and power structure in which the education system operates

Our approach

We will help national decision-makers to establish a clear picture of how their education system is working through good diagnosis. We will then provide support to tackle key delivery challenges, strengthen accountability for learning and adopt and deliver on more inclusive policies.

We will work in close partnership with national decision-makers committed to reform to improve learning. We will support efforts to increase domestic investment in education, including through strengthening tax systems to increase the public funds available and supporting better management of those funds so they have the greatest possible impact. We will also support more effective spending, through cutting waste and ensuring resources are focused on improving learning, starting with the basics. This will ensure better value for money for citizens in developing countries and the UK.

Where there is no national leadership to turn things around, we will look beyond stagnant public sectors, instead promoting improved transparency, accountability and coalitions seeking better education and investing through alternative channels which deliver for poor and marginalised children.

Making this assessment will require a good understanding of the political economy of education reform in the countries where we work, taking advantage of opportunities to improve learning when they arise. We will take account of the particular challenges posed by conflict and crises, ensuring the education interventions we support are informed by a good understanding of the drivers of conflict and contribute to peacebuilding objectives.

We will closely track changing context and progress achieved through our support. We will learn and adapt as we go – and support national decision-makers to do likewise[footnote 74].

We will support decision-makers to:

Strengthen transparency and accountability for learning.

System reform must be informed by good diagnosis of the main delivery challenges and data on how the system is performing. This will have maximum impact where it is used well by decision-makers, shared transparently and interpreted effectively by media and civil society organisations to make it meaningful for parents and communities.

We will:

- support decision-makers to carry out effective diagnosis of their education systems, in order to identify the bottle-necks holding back progress, and steps to focus the education system on children learning basic skills

-

invest in better education data, which is more widely used:

- globally, we will support efforts led by UNESCO Institute of Statistics to develop a new agreement on minimum levels of learning at key stages of education and globally comparable data on the number of children reaching these standards, and champion use of the new global flagship ‘children learning’ indicator

- nationally, we will work with decision-makers to improve the quality and use of education data, prioritising: a) good national and cross-national measures of learning; b) data on teacher knowledge and performance; and c) better data on hard-to-reach girls, children affected by crises, and children with disabilities

- promote public transparency and accountability for education quality, using data as a lever for change. We will encourage governments to share education data and support media and civil society organisations to translate it into meaningful messages for parents and communities, informing their choices and engagement with schools. We will highlight the issue of violence in schools, recognising its corrosive effect on children’s potential to thrive and learn, and support reform

Box 5: Strengthening political accountability for education in Pakistan

With our support, the Transforming Education in Pakistan (TEP) national campaign has successfully placed education on the political map of Pakistan, contributing to an increase in public spending on education from under 2% to over 3% of GDP. The campaign produces national, district and constituency data to establish a clear picture of system performance. Drawing on this data, the campaign builds parent networks, engages grassroots activists and convenes policy dialogue with politicians and government to build demand for better education outcomes.

Tackle delivery challenges, enabling access to UK expertise.

Once decision-makers have identified the key delivery challenges they must tackle to get more children learning the basics, we will stand ready to support. In addition to teaching, we will provide access to relevant UK expertise in areas such as:

- management, school leadership and inspection: We will support national adaptation of UK approaches to management, school leadership and inspection, such as the ‘delivery approach’ to education which promotes the routine use of targets and data for decision-making, leadership development to turn around poor performing schools and Ofsted’s school inspection model (box 6)

- non-state provision: We will support decision-makers to develop good regulatory arrangements which boost quality, accountability and innovation in the non-state sector and public-private partnerships which improve access to education for poor and marginalised children (boxes 7 and 8)

- education technology (EdTech): Through a new EdTech Research and Innovation Hub and our wider portfolio, we will support decision-makers to identify interventions which will help them to solve key challenges holding back learning (box 9)

Box 6: Supporting system strengthening in Ethiopia

With our support, the Ethiopian government has implemented major system reform which draws on UK expertise on school inspection and education planning and financing. The government has made significant progress in strengthening accountability of schools for quality provision, introducing regular school inspection and providing grants for better management and learning. This has resulted in encouraging gains in learning outcomes.

Box 7: Improving access to education through non-state provision in Pakistan

Punjab Education Foundation (PEF) is a non-profit government body which promotes education in non-state institutions, established by the Government of Punjab and supported by us. PEF provides a regulatory, monitoring and quality assurance framework to ensure partner schools meet performance standards. Through a voucher scheme, new schools programme and subsidies to existing low fee private schools, over 2.5 million students are accessing free of charge primary and secondary schools. On average, PEF schools outperform similar government schools in regular learning assessments.

Box 8: Enabling quality non-state delivery

The state is the guarantor of quality basic education for all, but need not be the sole financer or provider of education services. Non-state providers, including low-cost private schools, play an important – and growing – role in delivering education in low- and middle-income countries[footnote 75]. Across sub-Saharan Africa it is estimated that around one in five children and young people are enrolled at a private education institution[footnote 76], while in South Asia the figure is around 1 in 3[footnote 77]. Non-state actors are the dominant education provider in many urban settings in Asia and Africa. Many pupils attending private schools come from low-income families.

Non-state education provision will play an important role in meeting the educational needs of growing populations. It is essential that where we support non-state providers and public private partnerships, they work for poor and marginalised children. Interventions need to be carefully designed, implemented and monitored to ensure they retain a strong focus on the intended beneficiaries and do not have unintended consequences. We are building experience on how to achieve better outcomes through partnerships with non-state actors.

UK domestic expertise around mixed market provision, finance, accountability and approaches to raise overall standards can provide valuable lessons for partner governments. We must remain conscious that how we invest in the non-state sector matters; we need to develop and be guided by the evidence base and to experiment and adapt to ensure our investments drive maximum impact.

We will:

- support public-private partnerships which open up access to low-cost private schools to out-of-school and marginalised children, including those with disabilities

- work with others to maximise the availability of finance to non-state providers who wish to invest in quality and/or infrastructure

- support governments to improve regulation of the non-state market and share learning on how this can be done

- invest in data to strengthen accountability for the quality of non-state provision

Box 9: Solving problems using Education Technology (EdTech)

We recognise EdTech as a vital source of innovation for education, but it is not a silver bullet and many interventions – particularly those focused on buying new hardware such as tablets and computers – have failed because of poor implementation or weak fit with the context[footnote 79].

We are establishing an EdTech Research and Innovation Hub which will help decision-makers from developing countries make informed decisions about investing in EdTech and provide a platform for engagement between governments, tech companies and innovators.

We will support national decision-makers to take an integrated approach focused on the potential of EdTech to help solve key problems, such as:

- under-skilled teachers, for example, through enabling large-scale remedial learning

- poor quality and use of education data, for example, through enabling more straightforward and ‘real-time’ data collection on the quality of education services

- low learning outcomes for the most marginalised, for example, through enabling well-implemented facilitated learning for those outside of mainstream education or supporting teaching which is adapted to the right level for each child

Invest in inclusive reform.

We will work with decision-makers on inclusive reform that delivers for poor and marginalised children, and particularly hard-to-reach girls, children with disabilities and children affected by crises, sharing lessons learned from our support for these groups.

Two children tackle a maths question at a temporary school in northern Lebanon, set up by UNICEF and Lebanese NGO Beyond Association, with help of UK aid. Russell Watkins/DFID

In most developing countries, overall levels of learning are low, but poor and marginalised children usually learn the least[footnote 80]. For the most marginalised children, poverty combines with other sources of disadvantage, locking them out of opportunities to learn because of who they are (gender, disability, ethnicity) and where they grow up (poor family, remote location, conflict)[footnote 81]. To be fully inclusive, government policy and programming needs to tackle multiple sources of disadvantage simultaneously, and be more flexible to children’s diverse needs, so that the most marginalised children access quality education and learn[footnote 82].

We will support national governments stepping up to:

- take ownership of getting hard-to-reach girls into school and learning, drawing on the growing body of evidence on what works to reach this group. This includes developing, implementing and monitoring gender-responsive education plans, policies and budgets

- expand inclusion of children with disabilities into mainstream government and non-state schools from a low base, closing the gap between policy commitments and implementation

- integrate refugees and internally displaced children alongside host communities, providing specialist child protection and remedial support

Box 10: Integrating refugees and the internally displaced into mainstream education in Lebanon

Lebanon hosts the highest number of refugees per capita in the world and the public education sector has doubled in size to ensure places for over 220,000 Syrian girls and boys. Our support is benefiting both vulnerable Lebanese and refugee children, including child protection services for traumatised children, and non-formal education to help those who have been out of school for several years to catch up. Supported by UK technical assistance, the Government of Lebanon has taken ownership of the refugee response by developing the Reaching All Children through Education (RACE II) strategy, the first time in the world that an emergency response has been combined with sector planning. The strategy creates a common results framework focusing on access, quality, and stronger systems for the whole international community to get behind.

Box 11: Higher education systems

Higher education can play a crucial role in developing the highly skilled people that societies need to lift themselves out of poverty.

It can:

- underpin education, health and nutrition service provision by training the professionals needed to run the system[footnote 83]

- support growth by developing the business leaders who create jobs and the skilled workforce needed to fill these[footnote 84]

- develop future leaders who can think critically and solve problems, which will be crucial for driving peace, stability and good governance[footnote 85]

Linkages between UK universities and those in the South also help us to project UK influence and strengthen UK trade and investment opportunities[footnote 86].

Many developing countries spend a disproportionate amount on the higher education sector. We should only invest where we can drive positive societal impacts and should not fund higher education interventions which lead mainly to individual benefits for graduates.

As in basic education, we need to focus on quality – evidence shows that higher education is often not building higher order skills such as critical thinking[footnote 87]. Our interventions should be catalytic, increasing returns on domestic investment and improving the functioning of higher education markets.

Our support will take 3 forms:

- support to improve the quality of higher education within developing countries. This will focus on improving teaching strategies to ensure students are developing transferable skills so they can become the leaders of the future and driving greater accountability for learning outcomes

- scholarships to enable the best and brightest to gain access to good quality higher education in the UK or in developing countries. These will focus on developing skills which will benefit broader society, for example, by training those who lead teacher training efforts

- investment in development-relevant research, much of which is carried out within universities and is complemented by support to develop sustainable research and knowledge systems in the South

We recognise the crucial role that the British Council plays in supporting higher education and we will continue to work closely with them in this area.

Step up targeted support to the most marginalised

Why focus on targeted support to the most marginalised?

Targeted support to marginalised children funds a comprehensive package of interventions to support their learning. Some interventions focus on additional support for marginalised children to thrive in mainstream education – while others provide alternative or non-formal education for those outside of the mainstream.

Inclusive national reform is essential for sustainable improvements to education for poor and marginalised children, but in many countries it will take time and increased investment to achieve this. Targeted support helps ensure that some of the world’s most marginalised children are learning now.

We will focus targeted support on 3 highly marginalised groups:

Children with disabilities

Children with disabilities are the last to enter school and more likely to leave school before completing primary or secondary education[footnote 88]. Drivers include:

- disabilities go unrecognised - and specific needs are unmet

- supportive technologies and services are not available (eg assistive devices, adapted learning materials, trained teachers and support services)

- infrastructure, including toilets, is inadequate

- children with disabilities – and their families – face stigma and discrimination

Children affected by crises

Over a third of children affected by conflict do not complete primary education and almost two-thirds do not complete secondary education[footnote 89]. Drivers include:

- formal education systems break down and alternative services aren’t available

- children are displaced and on the move

- children suffer from trauma

- children are vulnerable to recruitment into armed groups or early marriage

- schools are targeted by violent groups

Hard-to-reach girls

Twice as many girls as boys never start school[footnote 90]. Amongst those who do, poor and marginalised girls are more likely to drop out than boys and do not transition to secondary[footnote 91]. Drivers include:

- discriminatory gender norms influence parents’ schooling choices

- girls carry a large share of domestic labour

- teaching materials are gender-biased and teachers invest more effort in boys

- girls are forced to drop out due to pregnancy or marriage

- menstrual hygiene facilities are inadequate

Our approach

Our targeted support will be based on robust analysis of the particular barriers to learning that hard-to-reach girls, children with disabilities and children affected by crises face in each context. We will ensure our interventions bring out of school children back into education and respond to the increased risk of violence that marginalised groups face.

We will show new leadership on children with disabilities. In most developing and conflict-affected countries, there is an enormous gap between policy and delivery on supporting children with disabilities and little evidence on successful interventions which can be delivered affordably at scale.

We have set out above the need to put in place the building blocks of inclusive reform for children with disabilities, including better data and more teachers and support staff with the skills to ensure children with disabilities learn.

In this Tanzanian classroom, some students with disabilities receive more personalised attention Kisiwandu primary school, Tanzania. GPE/Chantal Rigaud

To complement this, we will ensure support for children with disabilities, helping them transition into mainstream education and learn. We will support comprehensive and cost-effective interventions which include screening, assistive devices, teacher support, adaptive textbooks and parental and wider community engagement.

Box 12: Supporting children with disabilities in Punjab, Pakistan

Our Punjab Inclusive Education Project has tested what works to support over 3,000 children with physical, hearing, visual disabilities in mainstream government and non-state schools using vouchers, screening, teacher training, accessible infrastructure, and the provision of assistive devices. The project is also working with the Punjab Special Education Department to implement a new plan that will improve access to and quality of government schools for over 35,000 children with more severe disabilities, and private sector partnerships to support more children with disabilities in special and mainstream schools. We are also supporting provision of deaf education in Sindh province through the Family Educational Services Foundation, including development of a Pakistani sign language dictionary and technology to support the teaching and learning of deaf children.

We will continue to deliver for children whose education is disrupted by conflict, protracted crises and natural disasters. We will do this through:

- multi-year investments in quality education in conflict and crises: We will support children affected by crises to continue to learn, even during long periods of disruption. We will prioritise the most vulnerable children, including children with disabilities or those at risk of early marriage or recruitment to armed groups

- responsive, joined-up delivery which protects education systems: We will respond to immediate needs, make links between humanitarian and development interventions and re-programme swiftly when the context shifts – from development to emergency or emergency to recovery

- support for schools as safe spaces that promote children’s well-being: We will support children’s psychological and social well-being and conflict-sensitive education which promote inclusion and equity and minimise negative effects of conflict. We will prioritise child protection and work to make schools fulfil their potential as safe spaces for children during times of conflict and instability

Box 13: Reaching children affected by conflict in Syria

The conflict in Syria has had a catastrophic impact on education. Forty percent of schools have been damaged or destroyed and 1 in 4 children is at risk of developing a mental health disorder. We play a key role in the No Lost Generation Initiative, which provides protection, basic mental health support and education for children affected by the crisis inside Syria and in neighbouring countries. The UK has contributed towards the commitment agreed by the international community at the 2016 London Syria conference to provide all children with access to quality learning opportunities by helping over 350,000 Syrian children to access formal education and a further 80,000 to access non-formal education. Future support will ensure that up to 300,000 children in severe need will benefit from safe, inclusive, quality education services, including out-of-school children and children with disabilities.

We will maintain strong leadership on hard-to-reach girls, including girls with disabilities and those affected by crises, but also poor rural girls, pregnant girls and those vulnerable to early marriage.

To ensure another generation of girls do not miss out on education, we will:

- ensure hard-to-reach girls learn the basics – and progress through 12 years of quality education and learning: We will help eliminate the barriers that push hard-to-reach girls out of school before they have gained the skills and knowledge they need. This means interventions that tackle the cost of education, address the social norms that disadvantage girls, and make schools safe and healthy places for girls to be. We will invest in girls as they make the transition to secondary education and support them to complete secondary school and training wherever possible, opening up wider opportunities

- invest beyond academic learning to improve life chances: Formal secondary education will not be possible for all hard-to-reach girls, particularly those in remote areas where places are limited or distance prohibits access. In low-income countries, girls’ enrolment in primary is around 99%, but falls to 45% for lower secondary and 24% for upper secondary[footnote 92].. In addition to foundation and transferable skills, we will support life skills and sexual and reproductive health education to enable informed choices. We will also support skills for employment, with due attention to the evidence that supply-side interventions have often achieved poor success (box 15)

-

support cross-sector collaboration: These interventions will need to be underpinned by close working across sectors:

- social protection: To remove financial barriers for the most marginalised children

- health: To develop and implement sexual and reproductive health education and parenting interventions and to strengthen the role of education in the HIV/AIDS response

- water, sanitation and hygiene: To improve menstrual hygiene facilities which keep girls in school during menstruation and reduce risks of harassment at school

- economic development: To reduce gender discrimination and improve productive employment opportunities for girls

Box 14: Empowering girls in Tanzania and Zimbabwe

Since 2013, we have supported Camfed to tackle disadvantages faced by adolescent girls in rural Tanzania and Zimbabwe through the Girls’ Education Challenge. Female secondary school graduates return to classrooms in their rural communities as ‘learner guides’ to help teach a curriculum around life skills such as resilience and goal-setting, which complements the academic curriculum. Learner guides receive access to training, interest-free business loans and the opportunity to secure a BTEC qualification that opens up new pathways, including into teacher training. Zuhura, a learner guide in Bagamoyo District, Tanzania, said, “It makes me so proud when they call me ‘teacher’…I am a role model and a mentor. I believe in myself. I have goals and ambitions. I have found my path.” To date, over 266,800 girls across 35 rural districts have benefited. Thanks to Camfed’s interventions, girls’ retention has increased, and learning outcomes, self-awareness and self-confidence among learners have all improved[footnote 93].

Background paper to The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. (2016). The Learning Generation: Investing in Education for a Changing World. New York: The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity.

Box 15: Developing skills for employment

With sub-Saharan Africa’s population set to almost double by 2050 and large youthful populations already reaching working age, youth underemployment and unemployment are large and growing issues[footnote 94]. There is an urgent need to create more, higher quality jobs that are more productive and require higher skills levels. At the same time, workers in the poorest countries lack the skills employers need for productivity.

Achieving strong jobs results from donor-funded skills programmes has been challenging: a meta-evaluation found that for every 100 people offered vocational training, less than 3 will find a job they would not have otherwise found[footnote 95]. Many programmes have been insufficiently linked to employment outcomes and the private sector’s needs. Without these links, skills programmes are rarely an effective stand-alone solution to the jobs challenge. Without good jobs to absorb more skilled workers, migration or disillusionment are likely, especially for young people.

Skills programmes are often expensive relative to the income or welfare gains they achieve and we suspect that early intervention through formal education is more cost-effective than teaching basic skills once young people have left school.

Despite all of these challenges, we know from recent research that managerial, entrepreneurial and soft skills are critical drivers of firm productivity and firms will need more skilled workforces as the sophistication of production increases.

We will:

- invest, test and innovate to develop effective approaches to skills development which are responsive to emerging employment opportunities, ensuring stand-alone skills programmes are only taken forward where the evidence justifies it

- evaluate the cost-effectiveness of skills interventions versus formal education solutions

- focus on evidence-informed and context-specific interventions to build foundation, transferable and technical and vocational skills for young people who have failed to acquire the skills they need earlier in life. This could include supporting re-entry to mainstream education

We will invest in research and evidence on what works to improve learning for highly marginalised children. Priorities include:

- ensuring that the extensive knowledge that we have gained through support to the Girls’ Education Challenge, bilateral programmes and research is shared as a global public good so that others can benefit from the lessons on reaching marginalised girls

- addressing critical evidence gaps on the combined package of support needed to get children with disabilities and hard-to-reach girls learning and how to scale this in resource-constrained contexts

- understanding how to support learning and protection of children affected by conflict and crisis, including how to get more timely and reliable data to inform interventions

Across our policy priorities, we will build an evidence base from our interventions and through a doubling of the research programme help others step up and share evidence across our country network to strengthen links between research, policy and practice.

Box 16: Generating a culture of evidence in education

Through policies informed by evidence, the UK has turned around failing schools and developed inclusive systems at home. We have catalysed global debate on how to drive education reform through bold new research programmes. Through this debate, we are supporting decision-makers from across the globe to challenge the status quo and reassess what works to educate our children. Ministers are hungry to understand and to work in partnership with the UK to apply these lessons.

We will continue to expand the research portfolio to ensure our investments are based on robust evidence. This will require work across UK government, as well as with the British Council, the Academies and the Research Councils. The focus on research impact will continue ensuring evidence is put into use across the evolving new delivery priorities set out in the policy.

We will:

- demonstrate global leadership: through the Building Evidence in Education Platform we will catalyse further investments in research through partnerships with the World Bank, UN agencies, bilateral donors, non-state partners, and foundations. We will work with the Global Partnership for Education, the Education Commission and others to develop new diagnostics and support evidence-based sector plans that introduce ambitious system reforms, address the teaching crisis and focus on the most marginalised

- commission new research: we will double our investment and provide additional human resources with a focus on five areas including: education system reform, education technology, education in conflict and protracted crises, early childhood development and knowledge systems strengthening. Within all of these, we will integrate a focus on equality and gender. A step-change in the work on data and research methods will inform development of national delivery units

- build research capacity in partner countries: We will develop cross-sectoral partnerships with strong policy links to facilitate the production and uptake of research. We will build on the success of professional development schemes to enhance in-country capacity and analysis of data

- enhance professional development: We will work with the British Academy, the Research Councils and our global partners to ensure our advisers are at the cutting edge of global education research knowledge

Britain on the world stage

Strong global leadership and investment will be needed to support an ambitious national shift towards improved quality which ensures children are learning the basics.

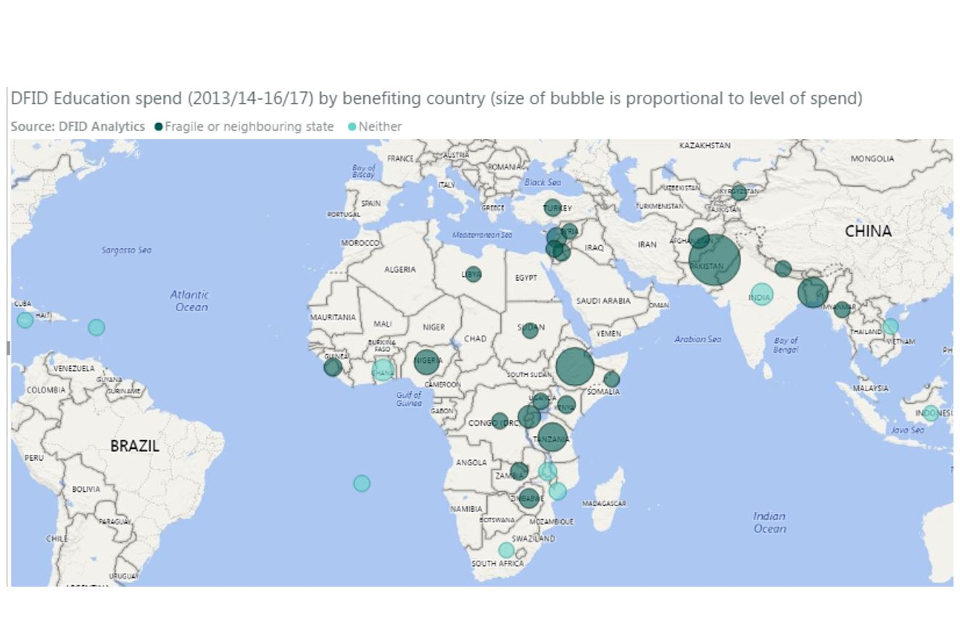

The UK leads the world on international development and is one of the largest bilateral donors to education, spending £964 million bilaterally on education in 2016[footnote 96].

We will take on global leadership on education for children with disabilities and work across government to maintain the global focus on hard-to-reach girls and children affected by crises.

Through our investment in the multilateral system, we influence a greater set of resources. Through the International Development Association, the World Bank committed close to $1.5 billion per year to education in 2014-16 (Figure 6). We are currently the largest bilateral donor to the education multilateral the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), which has spent around $500 million per year over the last three years (box 17)[footnote 97].

We will work with like-minded donors and multilateral partners – including the World Bank and GPE, Education Cannot Wait and UNICEF – on the following priorities:

- well-coordinated action across key international players: We will promote well-integrated support to national education systems across bilateral and multilateral organisations. We will make progress on embedding education as a key part of any humanitarian response, and bridging the humanitarian-development transition effectively

- increased ambition on the quality of delivery and learning, including in crises: We will ensure that all of our efforts are focused on the central aim of driving up quality and learning, even in the most challenging protracted crises. We will look beyond the quality of policies and plans to scrutinise how education is being delivered in practice, focusing in particular on action to improve the quality of teaching, reach poor and marginalised children and reduce violence in schools

- more and better spending on education: We will encourage greater investment but also reform by national governments, to promote better use of public resources on education. We will work with international partners to make affordable international finance available to national governments committed to quality and learning. We will promote co-financing of national education plans, which can increase the efficiency and effectiveness of aid spending. We will encourage donors and development finance institutions to increase the share of their funding available to education, which remains low relative to other sectors. We will explore options to help middle-income countries to borrow for education at appropriate rates and strategies to attract private investment in the education sector. We will hold multilateral partners accountable for delivering results and value for money, using conditional finance and building coalitions of donors to advocate for a greater focus on learning

Box 17: The Global Partnership for Education (GPE)