Company voluntary arrangement research report for the Insolvency Service

Published 28 June 2022

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

Executive summary

The Company Voluntary Arrangement (CVA) was introduced into insolvency law by the Insolvency Act 1986. In recent years, the commercial property sector has raised significant concerns around their use, particularly in the retail and casual dining sectors. Concerns include how compromises to rental debts, changes to long-term leases or the basis of calculating rents are unfairly affecting them in comparison to other classes of creditors.

Several CVAs have been challenged by commercial landlords. It has generally been argued that Proposals which substantially reduce lease payments were approved by creditors who are not materially affected or compromised, but who are able to submit a vote on the Proposals.

As a result, the Insolvency Service commissioned research to gather evidence to help form a more complete picture of the issue.

The Insolvency Service provided a list of 747 companies in the retail, accommodation and food and beverage industries, which had proposed CVAs between 2011 and 2020. This list was then refined to include just those companies that are defined as ‘large’ using the Companies Act 2006 criteria. This brought the number of companies within scope to 82. Out of those 82 companies, copy Proposals were obtained for 59, which is the sample for this research. The Insolvency Service asked three key questions.

Q1 - How do outcomes for landlords in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity compare to other creditors?

- Within our sample of 59 CVA Proposals, landlords were compromised – via an amendment to the rent payable for the CVA period, if not longer – in 93% of cases. The next highest single class compromised was intercompany creditors at 51%.

- The level of compromise, in respect of those that have been compromised, for landlords (Cat B-D) ranges from 46% to 85%. This compares favourably with compromise given to the other key categories of creditor (Intercompany 81%, Local Authorities 82%, non-critical trade creditors 88% and HMRC 89%).

- The average level of compromise for all landlords is 43% (this is an average across all landlords, including those whose debts were not compromised). This compares with the average level of compromise given to other key categories of creditor (Intercompany 48%, Local Authorities 39%, non-critical trade creditors 44% and HMRC 23%).

- However, the level of compromise of future rent often does not tell the full story. There may be other amendments (such as moving to a calculation of rent based on the annual turnover of the tenant) or additional areas of compromise relating to arrears of rent, service charges and dilapidations that we have not been able to assess as part of our work. This data would be challenging to obtain and was not included within the original scope of the research (and so is not reflected in these results). This may mean the level of compromise for landlords could be understated.

Q2 - Are landlords equitably treated, compared to other creditors, in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity?

There may be individual instances where landlords could argue that they have not been equitably treated, perhaps when compared to other landlords in categories which impose lower compromises. However, based on our analysis landlords are, broadly, equitably treated compared to other classes of unsecured creditors.

- CVA Proposals are prepared by the directors of a company and must adhere to statutory requirements which, together with insolvency guidance notes, aim to provide an equitable process. There are two key checks and balances in place:

- A Nominee – who must be a licensed insolvency practitioner – is required to provide an independent opinion. However, as the Nominees must fully understand the Proposal, they tend to be heavily involved in the drafting of the Proposal, leading to a potential perceived lack of independence; and

- The company’s creditors then vote on the Proposal (they may also propose modifications). For it to be approved, 75% or more (by value) of those voting must vote in favour – a relatively high bar. In addition, there is a second vote requiring 50% or more in value of unconnected creditors, to vote in favour of the Proposal. This secondary vote is aimed at preventing a “swamping” of the vote by connected creditors, though does not address the criticism that uncompromised creditors should not be able to vote. Given the low potential return in the relevant alternative, uncompromised creditors may argue that they still have a significant interest in the voting process.

- There are ongoing criticisms and challenges to the CVA process. These criticisms and challenges have led to several recent legal cases, but in themselves do not mean the process discriminates against landlords. For example:

- Landlords are able to vote for the value of any outstanding debt, together with the unexpired elements of their lease (subject to mitigation based upon the property being re-let), and so they typically have larger claims – and associated voting power – than other unsecured creditors.

- Almost all property leases include a clause that permits the landlord to take the site back if the company suffers an insolvency procedure (including a CVA). Recent case law (Debenhams) [Discovery (Northampton) Ltd v Debenhams Retail Ltd [2019] EWHC 2303 (Ch). [Debenhams CVA challenge: landlord’s objections - Practical Law (thomsonreuters.com)] (https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-022-1252?contextData=(sc.Default)&transitionType=Default&firstPage=true) The Court found that a CVA cannot vary a landlord’s right to re-enter its premises as such a right amounts to ‘property’ belonging to the landlord. While a CVA can vary the conditions under which the landlord can exercise that right, the CVA cannot vary the right itself] made clear that a landlord’s proprietary rights cannot be affected by a CVA and so, theoretically, any landlord with such a clause in their lease can take their site back.

- In addition, if a landlord is asked to suffer any loss, then the Proposal should offer the opportunity to take their premises back, per the Debenhams judgment and the BPF guidance [BPF - Company Voluntary Arrangements (CVAs)]. Table 4 indicates that this opportunity was offered in 78% of our sample.

- The proportion of creditors agreeing to the CVA Proposals reviewed is generally 85% or more in value of those voting. This suggests that landlords probably offer their support, given that landlords generally account for a large proportion of the claims for voting purposes in this sample. However, it should be noted that not all of those voting will be compromised.

- Creditors can challenge the CVA Proposals in court – though we note:

- the adversarial nature of any challenge;

- the substantial costs of any such challenge and the risk of adverse costs awards; and

- the lack of success of several recent challenges.

- CVA Proposals include an estimate of the potential return to creditors under the relevant alternative procedures. In all 59 cases we reviewed, the relevant alternative was an insolvency process. The estimated return in the relevant alternative was between 0-3% (or a compromise of 97-100%). All the CVA Proposals represented a better return for all classes of unsecured creditors (both compromised and uncompromised) compared to the relevant alternative.

- It is best practice for widespread consultation between the company and its key stakeholders/ creditors in the lead up to the CVA Proposals being launched, affording the chance for change/ amendment. However, this may not always occur, and improvements could be made in this area.

Q3 - If such a finding is made, to identify what specific levers in the framework are causing the issue and how.

Our analysis indicates that landlords as a whole have broadly been equitably treated. However, as noted, the level of compromise for landlords could be understated.

There are some considerations, which have become clear during our review of 59 proposals, which may provide greater clarity and improve stakeholders’ understanding of the CVA process:

- Length and clarity of Proposals – one of the key issues that was found during the data collection exercise is that Proposals are more likely to confuse than enlighten. It was observed that many of the Proposals are legalistic, lengthy, repetitive and lacking clarity. They could be improved with standardised summary tables, clauses, schedules and appendices.

- Consultation – whilst there is often consultation with key stakeholders, this could be improved. We have suggested in our report that Statement of Insolvency Practice (‘SIP’) 3.2 [Statement of Insolvency Practice 3.2 England and Wales COMPANY VOLUNTARY ARRANGEMENTS Statements of Insolvency Practice (SIPs) - England and Wales - ICAEW] is updated to include consultation with the British Property Federation (‘BPF’), on behalf of their members, in instances where landlords are being compromised and when certain criteria are met. The results of the consultation should then be included in the CVA Proposals. This should ensure such consultation is meaningful.

Whilst it is not within the scope of our work to compare all restructuring options available in the UK, it is our opinion that the CVA offers a flexible and cost-effective solution that bridges the gap between informal negotiations and formal insolvency procedures such as Administration / Liquidation.

A CVA enables companies to implement a legally binding financial restructuring swiftly, thereby providing an increased chance for the business to survive as a going concern, arguably a cornerstone of the UKs rescue culture.

The more recent Restructuring Plan (Part 26A Companies Act 2006) is a court-driven process with much more judicial scrutiny of what a company is proposing, with the court ultimately ruling on whether the Restructuring Plan should be sanctioned or otherwise. However, anecdotal evidence to date based on what is a limited sample, suggests that the associated costs of a Restructuring Plan are significantly higher than those of the average CVA. Accordingly, it has only been used in complex, very large company restructurings to date.

Glossary

BPF

British Property Federation, the representative body and voice of the UK real estate industry with members including property owners, developers, funders, agents and advisers.

BTCS

Baker Tilly Creditor Services, RSM’s in-house team that provides monitoring for dividends from CVA’s for clients including key utility companies.

Category ‘X’ landlords

Based on an analysis of the company’s property portfolio, the CVA Proposal will divide properties into categories with each category being affected differently. Categories are ranked alphabetically or numerically with A/1 usually being those that are least affected.

Compromise

Agreement between a company and its creditors to reduce the amount owed to a company’s creditors.

Connected creditor

A person is connected with a company if they are a director or shadow director of the company or an associate of such a director or shadow director, or they are an associate of the company. This includes employees of a company. A company is connected with another company if either the same person has control of both companies or if a group of two or more persons has control of each company and the group consists of the same persons.

Contractual Rent

Annual rent stated in the Lease.

Creditor

Any person or organisation that is owed money by a third party.

Critical creditor

Those creditors of a company where the directors consider that they are essential to the operation of the company’s business.

CVA

A company voluntary arrangement is a procedure under Part I of the Insolvency Act, which allows a company to come to an arrangement with its creditors over the payment of its debts. To become effective, the Proposal must be approved by 75% or more (in value) of those creditors voting. However, the Proposal will not be approved if more than 50% of the total value of the unconnected creditors voting, vote against it.

CVA Challenge

Legal proceedings commenced by a creditor to challenge the validity of the CVA on one or both of the following grounds:

(a) that a company voluntary arrangement unfairly prejudices the interests of a creditor, shareholder or contributory; or

(b) that there has been some material irregularity at or in relation to the meeting of the company or the qualifying Decision Procedure in which the company’s creditors decide whether to approve the voluntary arrangement.

Dilapidations

Repairs required during or at the end of a tenancy or lease.

HMRC

HM Revenue and Customs.

Intercompany creditors

Any company within a company’s group to whom a company owes a debt.

“Large” business/company

The Companies Act 2006 sets out that large businesses are those companies that meet at least two of the following criteria: 1) Turnover of more than £36m; 2) Balance sheet total of more than £18m; 3) More than 250 employees.

Non-Critical creditors

Those creditors of a company where the directors consider that they are not essential to the operation of the company’s business.

Preferential creditor

A creditor of a company that has priority over unsecured creditors, for example employees and HMRC.

Proposal

The Directors’ proposals for the CVA between a company and its creditors.

Relevant alternative

Whatever is considered most likely to occur in relation to a company if a CVA is not approved e.g., administration, liquidation.

Secured creditor

A creditor of a company that holds security (mortgage/charge) over the assets of a company.

SIC Code

Standard Industrial Classification codes are used to classify business establishments by the type of economic activity in which they are engaged.

Turnover rent

Rent payments based on a % of a company’s turnover for each site/premises.

Unconnected creditor

A third party, external creditor that is not a connected creditor.

Unsecured creditor

A creditor of a company that does not hold any security over the assets of a company and is not a preferential creditor.

Introduction and background

The CVA was introduced into insolvency law by the Insolvency Act 1986 following recommendations made in the Cork Report in 1982 [Report of the Review Committee on Insolvency Law and Practice (1982) Cmnd 8558, also known as the “Cork Report” was an investigation and set of recommendations on modernisation and reform of UK insolvency law. It was chaired by Kenneth Cork and was commissioned by the Labour government in 1977. The Cork Report was followed by a White Paper in 1984, A Revised Framework for Insolvency Law (1984) Cmnd 9175, and these led to the Insolvency Act 1986]. Market-usage of CVAs has evolved since the 1980s. From the mid-2000s Proposals have frequently been produced that focus on obligations owed to landlords, particularly in the retail and casual dining sectors. As such, they have attracted criticism from the commercial property sector for compromising or attempting to amend property leases and associated landlord rights.

The first ‘landlord’ CVA was arguably JJB sports in 2007. There was an increase in CVAs in the following years, reaching a high point in 2012 when the total number of CVAs reached 896. Since then there has been a gradual decline in the overall number of CVAs [Company Insolvency Statistics: October to December 2021 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) to a low point of 122 in 2021 as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Insolvency statistics in the UK 2011 - 2020

| Compulsory liquidations | Creditors’ voluntary liquidations | Administrations | Company voluntary arrangements | Receivership appointments | Total registered company insolvencies | % CVAs of registered insolvencies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 5,663 | 7,651 | 2,556 | 428 | 167 | 16,465 | 2.6% |

| 2008 | 6,206 | 10,222 | 4,973 | 588 | 227 | 22,216 | 2.6% |

| 2009 | 6,354 | 13,748 | 4,398 | 729 | 152 | 25,381 | 2.9% |

| 2010 | 5,754 | 11,718 | 2,990 | 820 | 113 | 21,395 | 2.8% |

| 2011 | 6,026 | 12,418 | 2,841 | 800 | 105 | 22,190 | 3.6% |

| 2012 | 5,400 | 12,379 | 2,618 | 896 | 84 | 21,377 | 4.2% |

| 2013 | 4,231 | 11,843 | 2,177 | 622 | 41 | 18,914 | 3.3% |

| 2014 | 4,598 | 10,655 | 1,716 | 609 | 27 | 17,605 | 3.5% |

| 2015 | 3,659 | 10,236 | 1,555 | 414 | 21 | 15,885 | 2.6% |

| 2016 | 3,721 | 10,462 | 1,522 | 385 | 14 | 16,104 | 2.4% |

| 2017 | 3,429 | 10,546 | 1,414 | 337 | 8 | 15,734 | 2.1% |

| 2018 | 3,784 | 11,604 | 1,562 | 388 | 7 | 17,345 | 2.2% |

| 2019 | 3,797 | 12,460 | 1,916 | 369 | 3 | 18,545 | 2.0% |

| 2020 | 1,687 | 9,762 | 1,612 | 286 | 5 | 13,352 | 2.1% |

| 2021 | 636 | 13,301 | 842 | 122 | 1 | 14,902 | 0.8% |

Concerns have been raised, particularly by those representing commercial landlords, such as BPF [BPF - Company Voluntary Arrangements (CVAs)], that CVAs are being used to disadvantage or target commercial landlord debts more than other creditors, or to rewrite long-established leasing arrangements or contracts.

Research by PwC [https://www.pwc.co.uk/business-restructuring/pdf/cvas-2020-and-beyond.pdf] considered 17 CVAs in England and Wales, entered into by larger companies in the retail, consumer, hospitality, and leisure sectors between January and November 2020. They found that, in the sampled cases, 4.6% of sites saw no change to lease terms. All 17 CVAs affected multiple creditor groups, not just landlords. However, for a number of these, the only other creditors adversely impacted were intercompany.

Several CVAs have been challenged by landlords. Those landlords generally argued Proposals that substantially reduced their lease payments (which in turn affected their own business / covenants) were approved by creditors who were not materially affected or compromised, but who were able to submit a vote on the Proposals.

As a result, and given the fundamental changes to lease arrangements implemented by such CVAs, the Insolvency Service wants to form a more complete picture of the issue and commissioned quantitative data collection and analysis to answer the following three questions:

- How do outcomes for landlords in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity compare to other creditors?

- Are landlords equitably treated, compared to other creditors, in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity?

- If such a finding is made, to identify what specific levers in the framework are causing the issue and how.

We have set out below our methodology, results and conclusions, but in answering the second question we have assumed that by “equitably treated” the Insolvency Service and other interested parties would consider this may equate to outcomes for the different categories of creditors.

Methodology

The key steps have been:

- Original data set: The Insolvency Service provided a “long list” of 747 companies which had proposed CVAs between 2011 to 2020.

- Filtering by SIC Code: The long list was filtered by SIC codes provided by the Insolvency Service (47, 55 & 56 – Retail trade, except motor vehicles and motorcycles, Accommodation, and Food and beverage service activities).

- Filtering by size of company: Further filters were then applied using the size of the company, as the research focus was on “large” businesses [Companies Act 2006 (legislation.gov.uk)]. In line with business population estimates [Business population estimates for the UK and regions 2021: statistical release (HTML) - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)], the criterion applied was companies with >250 employees, taken from the latest set of published accounts. This resulted in 68 companies being within scope of the research. To ensure all potential large businesses were captured, additional criteria of turnover > £10.2m or assets > £5.1m were then applied to the remaining companies, leading to an additional 14 companies becoming in scope. Following this methodology, the total number of companies in scope was 82.

- Obtaining CVA Proposals: Obtaining CVA Proposal documents (the key document setting out the terms of the CVA) is not straightforward as they are not publicly available documents. We accessed the following to source Proposals:

- RSM Proposals – of the 82 sample, insolvency practitioners from RSM acted as the Joint Supervisors in seven and assisted in drafting the proposals in another one.

- BTCS – one of our internal departments has considerable contacts/clients in the Utilities sector, who have been creditors in many CVAs. This resulted in eight Proposals being made available.

- BPF – the BPF were able to provide a further 33 Proposals.

- Other RSM contacts – via our intermediary network and those on the Insolvency Committee of the BPF, we were able to obtain a further 10 Proposals.

Following these methods, 59 Proposal documents were obtained relating to the 82 companies in scope.

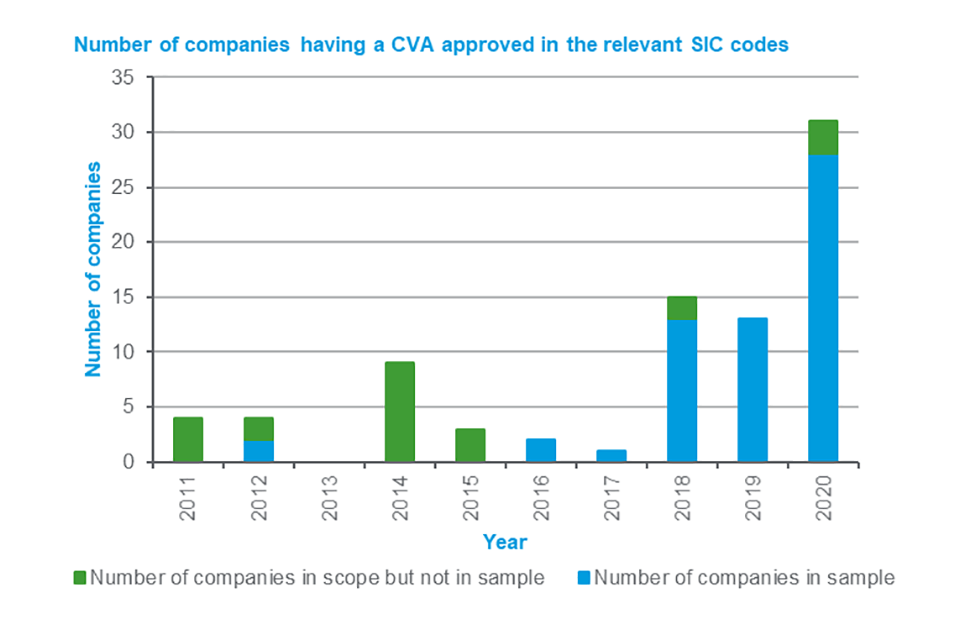

Figure 1 shows the CVA start date of the 82 companies within scope and the 59 CVAs within the sample. Unsurprisingly, there was a sharp increase in the number of companies proposing a CVA in the selected company criteria and sectors included within this research in 2020, given the impact of the pandemic and associated lockdown on the industry/sectors considered. This is at odds with the overall decline in total CVAs as illustrated by Table 1.

Figure 1

- Spreadsheet preparation: Our in-house modelling experts set up a detailed spreadsheet capable of being accessed by multiple users and ensuring data integrity with protected cells etc.

- Data input: CVA Proposal documents can be extremely lengthy and legalistic (up to 300 pages long). We reviewed each of these documents for the key terms and inputted the agreed criteria into the aforementioned spreadsheet. This input was sample checked by in-house CVA experts to ensure the accuracy of the data.

- Data analysis: Our in-house data analysis team overlayed the spreadsheet with a Power BI report, extracting the key data and analysing it quickly and easily. We have provided the Power BI analysis and the underlying spreadsheet to the Insolvency Service.

- Reporting: Using the above analysis we extracted the key results and incorporated the associated findings into this report. We have sought to answer the three questions raised by the Insolvency Service. We have also provided details of the limitations of the analysis, taking into account our experience of other research projects and considered other potential issues.

Limitations in methodology and data

Whilst the dataset is comprehensive, especially given the difficulty in obtaining data from Proposals, the sample is not random. This means there is potential for bias that could impact the data and conclusions.

There are some limitations inherent in the above methodology and work to date, including the following key areas:

- The degree of flexibility allowed in CVA Proposals (which is a function of the legislation). Whilst there are some similarities between different Proposals, and certain “standard” clauses have emerged, each CVA is unique to the circumstances of the individual company. This is one of the key benefits of the CVA as a restructuring tool, but it does not lend itself to easy comparison and analysis.

- The research scope only required data for landlords in respect of rent reductions for the duration of the CVA/rent concession period. However, in some of the Proposals, certain other lease liabilities were also compromised (rent and service charge arrears, and dilapidations) and these are not reflected in our analysis. Therefore, the overall rate of compromise in relation to landlords is likely to be understated.

- The CVA Proposals do not have to include the £ amounts payable to all creditors. In some circumstances these numbers are disclosed, but often there is only a percentage compromise disclosed. Whilst it is possible to compare percentage compromises, it is not always possible to quantify the compromise in £’s. Although the amounts can be calculated by reference to the values in the Statement of Affairs/Proposal schedules and the p/£ return for the associated creditors, the proposed rent reductions for landlords cannot be quantified as the relevant information (i.e. contractual rents per property) is not disclosed, being commercially sensitive, and the impact of a move to turnover rents cannot be quantified.

The following issues are also of note:

- The research specification originally asked the question “‘were landlords compromised’ Yes/No, if yes, what was the percentage rent reduction?”. Unfortunately, the position is not that simple, as the majority of Proposals do not put all landlords in one category; instead, they are categorised based on store/property performance, current rent levels and the level of rent reduction required to make them viable. For example, Category A/1 landlords are usually unaffected as the associated rents are considered appropriate to the site and the premises are usually profitable. However, in the same Proposal there will be landlord categories in which rent reductions are proposed. To make the analysis more meaningful, the data criteria had to be expanded to ask the same questions but for four categories of landlords. We felt that this would be sufficient to capture the different levels of rent reduction applied, albeit in some Proposals there were more than four categories and in others there were fewer. In the cases were there were more than four categories of landlords, categories were grouped, and an average of the rent reductions imposed calculated and recorded.

- The research specification originally asked the question “‘were trade creditors compromised’ Yes/No?”. In 25 Proposals trade creditors were split into two categories, critical and non-critical, and different compromises were applied to each category. We therefore expanded the analysis to include the impact on both critical and non-critical trade creditors. If there was no such split in the Proposals, we categorised them as non-critical.

Results and conclusions

The key questions to which the Insolvency Service is seeking answers are set out below.

We have structured this section of our report to address the questions, highlighting key elements of the analysis performed.

Research questions

- How do outcomes for landlords in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity compare to other creditors?

- Are landlords equitably treated, compared to other creditors, in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity?

- If such a finding is made, to identify what specific levers in the framework are causing the issue and how.

Question 1 - How do outcomes for landlords in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity compare to other creditors?

How often are creditors compromised?

When considering the outcome for landlords and other creditors it is important to note that not all creditors are compromised in a CVA. This can include secured creditors (primarily banks), preferential creditors (employees and certain HMRC debts) and other critical creditors (often trade creditors/key suppliers or key landlords).

In comparing outcomes, we initially considered how often each type of creditor is compromised in the 59 CVAs in the sample (with N/A meaning the instances in which there were no creditors of that type), shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Frequency of creditor compromise

| Landlords | HMRC | Trade creditors | Local authorities | Intercompany | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compromised | 55 (93%) | 15 (25%) | 29 (49%) | 27 (46%) | 30 (51%) |

| Not compromised | 4 (7%) | 43 (73%) | 29 (49%) | 27 (46%) | 21 (36%) |

| N/A | - | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (8%) | 8 (13%) |

It is clear that at least some landlord positions were compromised in the majority (93%) of the Proposals considered. This compares with the next highest categories of compromise, intercompany creditors at 51% and trade creditors at 49%. Based on this initial analysis, it appeared landlords faced a relatively adverse outcome as they were compromised more often than any other category of impacted stakeholders. However, the analysis on the following pages shows that even where an element of landlord compromise is included within a Proposal, not all landlords therein are compromised and/or to the same extent as others.

Where trade creditors were compromised (49%), in 76% (22 of the 29 instances) of those cases, critical trade creditors were not compromised (only non-critical creditors were compromised).

What is the level of compromise for each creditor?

The next key criteria considered was the level of compromise for each category of creditor. The analysis became more nuanced when considering the level of compromise, as in a considerable number of our sample (53 of 59), landlords were split into several categories, essentially based on the profitability/desirability of the store compared to contractual and market rental levels. Categories are ranked alphabetically or numerically with A/1 usually being those that are least affected.

As noted in the methodology section, it was not always possible to obtain the monetary values of the level of compromise suffered by each creditor, so we compared the percentage compromise of the respective debts.

Table 3 indicates that Category A landlords (theoretically the most desirable sites) appear to suffer a higher level of compromise than Category B or C. However, in our sample, there were only six cases where the Category A landlords were compromised:

- Company A [These companies’ names have been kept confidential as the proposals are not publicly available] – where there was only one category of landlord and the rent reduction was 100%;

- Company B – where there were two categories of landlord (Category A – 80% rent reduction and Category B 95% rent reduction);

- Company C – where the Category A rent reduction was 10%; and

- Three other Proposals moved Category A landlords to turnover rent.

As such the Category A numbers above are skewed by the small number (3) where the percentage rent reduction is explicitly stated, and the trend is much clearer and demonstrable across Category B, Category C and Category D.

The next creditor type analysed was the critical creditors category (Table 3) which shows the lowest level of average compromise, of those with a reduction (37%). However, this data is also potentially skewed by the very low number of instances where this class of creditor was compromised (there were only 3 instances of compromise for critical creditors across the 59 Proposals in the sample (5%)) with compromises of 25%, 30% and 55%. It is apparent that it is rare for the most profitable leased sites and the company’s critical trade creditors to be compromised.

This contrasts with non-critical creditors who are regularly compromised, and the average level of compromise is 88% (slightly above the least desirable Category D landlord sites).

Table 3: Creditor compromises

| Cat A Landlord | Cat B Landlord | Cat C Landlord | Cat D Landlord | Total Landlord | Critical | Non-critical | Inter company | Local authorities | HMRC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in sample | 55 | 51 | 46 | 37 | 189 | 26 | 58 | 51 | 54 | 58 |

| Number compromised | 6 | 49 | 46 | 37 | 138 | 3 | 29 | 30 | 27 | 15 |

| Number moved to turnover rent out of total compromised | 3 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 26 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Average compromise (of those with % reduction) | 63% | 46% | 62% | 85% | 63% | 37% | 88% | 81% | 82% | 89% |

| Average compromise (all in category) | 4% | 44% | 62% | 85% | 43% | 4% | 44% | 48% | 39% | 23% |

HMRC’s reinstatement as a secondary preferential creditor for certain debts took effect from 1 December 2020. There are four CVAs within our sample where the effective date was after this date. In three of those cases HMRC was not compromised and in one case it appears that there was no debt due to HMRC.

As Table 3 shows, rather than a specific percentage reduction in contractual rent, the Proposal may allow the company to pay rent based on a percentage of turnover. This applies at the site/premises that are being proposed to move to turnover rent. Again, given the flexibility of CVAs, not all Proposals state that the company will pay percentage turnover rent, rather there is a range of terms e.g. percentage turnover capped at percentage of contractual rent, x% of contractual rent topped up by y% of turnover. The move to turnover rent allows companies to align one of their key overheads to performance, but this can make it difficult for creditors, including landlords, to meaningfully assess the financial impact of such compromises.

Any reduction in rent as a result of the move to turnover rent is not reflected in our average compromise calculation and so the average compromise may be over or underestimated.

As stated in the methodology section, the dataset only included information on rent reductions for the term of the CVA/rent concession period. However, there are other lease liabilities that may be compromised, including rent and service charge arrears and dilapidations. The level at which these are compromised will generally depend upon the category of the site. This is not reflected in our research, though landlords may argue that these should be taken into account in considering the level of compromise they are being asked to accept compared to other creditors.

Table 3 also shows the percentage compromise including all those creditors who could have been compromised, but were not (i.e. those with 0% compromise are included in the calculation). This analysis shows a clear pattern that the level of compromise increases as the desirability of the landlords site decreases (Cat A – D). It also shows that the least desirable sites are more frequently compromised than the other categories of creditor(s) and that the total landlord compromise is at least no worse than other categories of creditor(s).

Question 2 - Are landlords equitably treated, compared to other creditors, in large business CVAs from either the Retail trade, Accommodation or Food and beverage service activity?

We have interpreted this question as implying that there is a significant degree of neutrality in assessing who is compromised and by how much. However, a CVA Proposal is ultimately submitted by a company’s directors who are focused on restructuring the company in question. There are nonetheless a number of checks and balances in the legal framework including the following:

- Nominee

The first is the role played by the Nominee, who must be a licensed Insolvency Practitioner. A Nominee will:

- consider the Proposal to form an opinion as to whether a CVA is the appropriate method of dealing with the company’s affairs; and

- prepare the Nominee’s report stating –

- why the Nominee considers the Proposal does (or does not) have a reasonable prospect of being approved and implemented; and

- why the members and creditors should (or should not) be invited to consider and vote on the Proposal.

- The Nominee will then summon the shareholders’ meeting and invite creditors to consider the Proposal by way of a decision procedure.

- Voting on the CVA Proposal

The second check and balance is the vote itself, where creditors are provided with the opportunity to vote for or against the Proposal. At that stage the creditor is at first glance faced with a binary decision and the associated compromises are already documented/set out in the Proposal.

Creditors have the opportunity to propose modifications to a Proposal, but it is at the directors’ discretion as to whether those modifications should be accepted. It should be noted that it could be quite difficult for individual creditors to offer alternative solutions or modifications without having knowledge, or experience of, the CVA process.

The Proposal put forward is for all creditors (with the exception of secured creditors) to vote on and therefore it is for the creditors to judge if the Proposal is equitable from their point of view. That said, we note it can be challenging to fully understand the Proposals – see further points below.

Trade and preferential creditors are entitled to vote for the amount owed to them at the date of the ‘vote’/decision procedure, whereas there is a formula to calculate the amount for which a landlord is entitled to vote (see below).

The procedure for admission of creditors’ claims for voting purposes is set out in the Insolvency Rules [The Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 (legislation.gov.uk) and The Insolvency (Scotland) (Company Voluntary Arrangements and Administration) Rules 2018 (legislation.gov.uk)], which do not distinguish landlords from other creditors. Landlords claims for future sums such as rent, service charge, insurance, dilapidations, which may become due under the lease are difficult to quantify. Applying the Insolvency Rules, the insolvency practitioner might value the unliquidated/unascertained claim of a landlord (for voting purposes) at £1. However, the insolvency practitioner has discretion to admit such claims for voting purposes at a higher value than £1. Factors taken into account may include the accepted valuation process used to establish the loss to the landlord if the tenant were to enter into liquidation, together with input from professional property advisers. This has become standard practice in the last few years. A discount is then applied to take into account the uncertainty of the future elements of the claim. This can result in landlords who have relatively small debts due and payable at the time of the CVA having claims for voting purposes that are significantly higher (due to the future amounts taken into account). We are aware that there is some criticism in respect of the level of discount applied to the value of the future elements of the claim as these are not treated consistently in different proposals. However, investigating this aspect of CVA proposals is not within the scope of this report.

The chair must send a report to the court following the creditors’ decision procedure considering the proposals. Among other things, the chair’s report provides the details of creditor votes, and the Proposals provide the level of discount applied, both of which could be further analysed, but as noted we have not undertaken this as it was not within scope of this research, and it would likely be a time-consuming exercise.

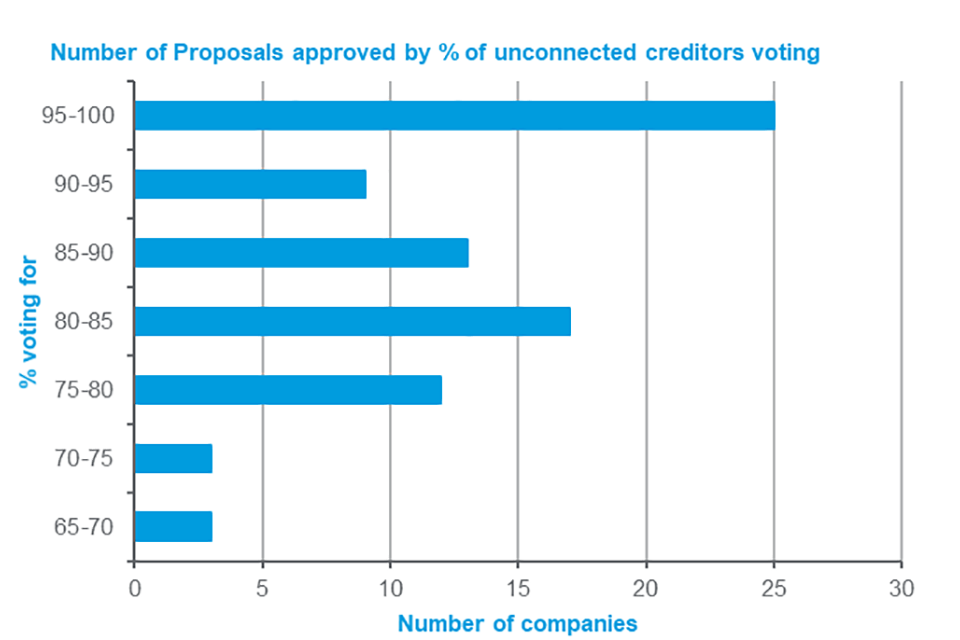

As can be seen in Figure 2, of the 82 companies within scope, all had approval of at least 65% of the unconnected creditors, with over half of the Proposals receiving more than 85% of support.

Figure 2

If the Proposal is passed, it can be argued that the large majority of voting creditors (75% or more in value of those creditors voting) believe the Proposal is equitable, or at least presents a better return than the relevant alternative. That said, we are aware of criticism that Proposals are voted through by those creditors that suffer minimal impact, or that have a vested interest in the company (Category A landlords, critical creditors, intercompany creditors and employees), at the expense of the impaired/compromised creditors, whose position is ‘swamped’.

However, there is also a safeguard of the ‘2nd vote’ wherein connected creditors are excluded - where 50% or more in value of those voting must vote in favour for a Proposal to be passed. However, this does not exclude the votes of the unconnected but uncompromised creditors and therefore does not fully address the complaints noted above in respect of vote ‘swamping’.

Actions available to creditors if they object

If a creditor does not believe that the Proposal is equitable, they have the following options:

- vote against the Proposal;

- stop supplying goods/services if the Proposal is approved; and

- Apply to the court to challenge the CVA on appropriate grounds.

If a landlord does not believe that the Proposal is equitable, they have similar options:

- vote against the Proposal;

- exercise the break option if offered in the Proposal (Table 4); and

- Apply to the court to challenge the CVA on the appropriate grounds.

If lease terms are being amended by a Proposal (other than a move to monthly rather than quarterly payments) then it should include additional break rights for the impacted landlord. Therefore, if a landlord is unhappy with what is being offered to them, they have the ability to take the property back and re-let to another entity on commercial terms/market rent.

Recent case law [Discovery (Northampton) Ltd v Debenhams Retail Ltd [2019] EWHC 2303 (Ch). The challenge to the Debenhams CVA was brought by a group of Debenhams’ landlords. One specific ground of challenge was in reducing the rent payable under the lease, the CVA was automatically ‘unfairly prejudicial’ to the landlords. The Court ruled that the reduction of rents payable under the lease was not automatically unfairly prejudicial to the landlords, the ruling said. The Debenhams CVA was fair because it permitted the landlords to bring an end to the varied lease if they wished to do so and the CVA did not impose any new obligations; it only varied existing obligations] in relation to a challenge to the Debenhams CVA ruled that the proposed reduction of rents payable under a lease was not automatically unfairly prejudicial to the landlords. In that case it was fair because the Proposals permitted the landlords to bring the varied lease to an end if they wished to do so.

Table 4 shows instances of landlords being compromised and given the opportunity in the Proposal to take their sites back:

Table 4: Landlords compromised and given the opportunity to terminate

| Number of instances compromised | Opportunity given to terminate the lease | Sufficient opportunity (90) days to take the site back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category A | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Category B | 49 | 42 | 35 |

| Category C | 46 | 41 | 33 |

| Category D | 37 | 20 | 15 |

It should be noted that in certain circumstances the Proposals will provide that sites within a specific category (usually D) be exited immediately upon the Proposals being approved, or shortly thereafter and these are not included within the above numbers.

Challenges to the CVA and the Relevant Alternative

As noted above, one option for landlords (and other creditors) who disagree with the outcome of a vote is to challenge the CVA by applying to the court. There have been some notable challenges in recent years, but these have generally been unsuccessful. An appeal against the judgment in New Look [Lazari Properties 2 Limited and others v New Look Retailers Limited, Butters and another [2021] EWHC 1209 (Ch). Lazari Properties 2 Ltd & Ors v New Look Retailers Ltd & Ors [2021] EWHC 1209 (Ch) (10 May 2021) (bailii.org)

The challenge was brought by landlords who alleged that the CVA was inherently unfair including the lease modifications imposed on landlords. The judge held that any potential prejudice was sufficiently addressed by offering a termination right in the CVA proposal in return for imposing lease modifications, provided that the terms offered for the notice period were better than the alternative the landlord would receive on an administration or liquidation. Landlords were afforded a choice: whether to stay with the CVA terms or to take the property back. The landlords appealed this judgement but a settlement was reached between the parties prior to the appeal hearing] was lodged, however, this was settled shortly before the trial and the terms of the settlement are not known.

As the Court of Appeal did not have the opportunity to revisit the issues highlighted by landlords in that case, the original High Court decision sets out the latest legal standpoint on how landlord claims ought to be treated.

It would appear there could be two possible outcomes for landlords/creditors that successfully challenge a CVA in practice:

- Their position is improved compared to other creditors e.g. they move to a higher category within the Proposal; or

- The approval of the CVA is revoked and the status quo prior to the approval is reinstated (a court may also give supplemental directions following a revocation).

The former reason would appear to be a commercial decision, but the latter would likely see the company entering into Administration or Liquidation (which is the relevant alternative in all the Proposals reviewed – 54 stated Administration, five stated CVL). This is highly likely to result in a much lower return to all creditors and a much more uncertain outcome for landlords.

The spread of estimated percentage return in the relevant alternative (from our sample of 59 Proposals), is an average of 2.6% (with a range of between 0% and 20.2%) for creditors if the CVA is not agreed.

Even for the most affected creditors in the CVA Proposal (e.g. non-critical trade creditors whose average compromise is 88%) the relevant alternative does not appear to be an attractive option.

Other research [Selective Corporate Restructuring Strategy by Sarah Paterson, Adrian Walters :: SSRN] has suggested that the challenge process in the CVA is overly adversarial and costly as it must be pursued through the courts and that this could put off potentially legitimate challenges by smaller creditors. Whilst there is some merit (particularly regarding cost) in that argument, it does not necessarily reflect market practice. There is usually significant negotiation and consultation with critical/significant creditors before a CVA Proposal is launched (particularly in the larger CVAs in our sample). Indeed, there can often be months of negotiation between a company and creditors (including some involvement of the BPF) before a Proposal is finally launched.

Secured lenders are likely to be consulted within the CVA process. Secured lenders cannot be compromised in a CVA without their consent and so are excluded. However, there may be a consensual restructure, a scheme of arrangement and potentially a write-off of secured debt that is undertaken alongside the CVA Proposal. This is not always included in detail in the Proposals due to commercial sensitivity and other creditors may not be aware of the level of support being provided by the secured lender.

Table 5 below provides details of the outcome of the CVAs of the 59 companies within the sample. It further details the number of instances in which landlords were compromised for each outcome and the average landlord compromise.

Table 5: CVA outcome

| Completed successfully | Terminated early | Still ongoing | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 18 | 22 | 59 | |

| No of times Landlords compromised | 18 | 15 | ||

| Average landlord compromise | 41% | 40% | ||

| Current company status | ||||

| Active | 11 | - | 11 | |

| Administration | 7 | 12 | 19 | |

| Dissolved | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Liquidation | 1 | 4 | 5 |

As can be seen, 19 (32%) CVAs were completed successfully out of the sample of 59. However, when considering only those CVAs that have been completed (i.e. removing those still ongoing), the percentage of CVAs successfully completing increases to 51% (19 out of 37). Of the 19 that completed successfully over half (11) are currently shown as active companies at Companies House and the remaining eight are in an insolvency procedure.

Our key points are summarised below:

| Key point | Comment |

|---|---|

| Landlords are compromised in 93% of our sample | Landlords are compromised in more of our sample than any other category of creditor. Landlords may argue that this is inequitable, however, it could be due to the industry codes selected and the economic reality of the major changes on the UK High Street. |

| Landlords comprise (for those that have been compromised) ranges between 46-85% (Category B-D). (see Table 3) | The average compromise for other creditors was 37-89%, but the lower element of that range is for critical trade creditors, which are very rarely compromised at all (similar to Category A landlords). If critical trade creditors are excluded, the range of compromise relating to other categories of creditors is 80-89%. |

| Total landlord average compromise is 43%. (including those that could have been compromised, see Table 3) | The average level of compromise, calculated on the same basis, were 4% for critical creditors, 23% for HMRC, 39% for local authorities, 44% for trade non-critical creditors and 48% for Intercompany creditors. Based on these findings it is difficult to argue that landlords are not treated equitably. |

| The level of overall landlord support and/or compromise is very difficult to fully quantify given it is not often disclosed fully. | It is not possible from the information contained within the Proposals to quantify the level of financial ‘support’ that is being provided by landlords compared to other creditors because the relevant information (contractual rent by property) is not disclosed as it is commercially sensitive. Similarly, if certain landlords are moved to turnover rent for the CVA/rent concession period the amount of financial support provided will not be known until the end of the CVA/rent concession period, compared to the amount that would have been due according to the lease. A landlord might argue that fundamentally altering the terms of a legal agreement between two parties is itself inequitable, but this would be very difficult to quantify as it would require detailed analysis of returns to landlord following the completion of the CVA. The financial ‘support’ provided by other creditors can be calculated by reference to the p/£ return and the creditor values, for example if trade creditors are receiving 5p/£ return and the total amount owing to that category of creditor is £1m then they are providing the company with £950k of support. However, based on the percentage compromises noted above it appears unlikely that landlords are materially worse off than other creditors compromised. |

| CVA Proposals sampled are passed by a very high percentage of creditors. | In 47 of the 59 CVAs in scope, 85% or more in value of the unconnected creditors voted in favour of the CVA Proposal. In only six of the CVAs was this lower than 75%, suggesting that the majority of CVAs are passed / approved by a significant majority of landlords and other creditors. Whilst there are clearly some cases where connected creditors have an influence on the voting outcome, it should also be noted that in a number of cases intercompany debt is not compromised, but no distribution/repayment is made in respect of the debt during the CVA period. |

| If the CVA is not approved the relevant alternative represents a much poorer outcome for all creditors. | In all cases sampled the relevant alternative represented a significantly worse return to all creditors. This ranged from 0-3% per the Proposals (or a 97-100% compromise). The range of compromise in the CVAs for landlords ranged between 46-85% (Category B-D). |

| Very similar rights are available to landlords and other creditors in the event they do not approve/agree with the Proposals. | In the event the Proposal is approved, any landlords who voted against have very similar rights to other creditors, e.g. they can exercise the break clause in the Proposal (akin to other creditors withdrawing a service), or they can challenge the CVA (as can other creditors). The rights therefore appear to be equitable across all classes of creditors. |

| It is best practice for key stakeholders, including landlords to be consulted before the Proposal is launched. | Particularly in large company CVAs it is best practice to negotiate and consult with key stakeholders (often landlords) before launch. This can result in changes to Proposals before launch and appears to be reflected in the high level of approval. Whilst consultation may not be practical with all stakeholders, engagement with the BPF may assist with reflecting a broader range of views. The BPF have a list of ‘red flag’ clauses [BPF CVA red flag clauses - insolvency engagement guidance. bpf-cva-engagement-document-v3-2407.pdf The BPF strongly encourages prospective Proposers of a CVA and their Nominees to consult with the BPF in advance of a CVA Proposal being distributed. This allows representatives of the landlord community to identify particular issues within a CVA that may need to be addressed, and therefore helps to maximise the likelihood of approval. There is a list of what the BPF believes to be the top 10 ‘red-flag’ clauses. The BPF caution any prospective landlord voting on a proposed CVA to look out for these clauses and ask that Insolvency Practitioners consider whether they can be removed prior to a CVA being launched] for insolvency practitioners to take into consideration when proposing a CVA. |

There may be individual instances where landlords could argue that they have not been equitably treated, perhaps when compared to other landlords in categories which impose lower compromises. However, based on our analysis, it appears that landlords are broadly treated equitably compared to other classes of unsecured creditors as:

- They tend to have disproportionately larger voting rights than other groups of creditors (see comments above regarding landlord claim values);

- The voting does not appear to be skewed by the impact of unconnected creditors; and

- They have similar rights to all other creditors: they can propose modification to the Proposal and – if they do not agree with a Proposal that is voted through - they can take their site(s) back (akin to withdrawing a service) or submit a statutory challenge.

Further analysis could potentially be performed in three key areas to provide more clarity (which were not in the scope of this research):

- Chair’s statements may be analysed to further understand the voting split. This may provide further evidence regarding how frequently non-landlord creditors (or the least-affected creditors/landlords) vote through Proposals. However, it would likely be a time-consuming exercise and of potentially limited value;

- Service charge arrears and dilapidations – these could be included in the analysis to provide a broader definition of the compromises made by landlords, but it may be very challenging to obtain this level of detail; and

- Overall quantum of the losses/compromises made by each category of creditor. As noted, this is not disclosed in the Proposals, so this would require the co-operation of the CVA Nominees/Supervisors to obtain this data and would therefore be a lengthy and potentially costly exercise.

Question 3 - If such a finding is made, to identify what specific levers in the framework are causing the issue and how.

We believe that our analysis supports the supposition that landlords have broadly been equitably treated. However, we have set out below some further considerations based on our analysis which may provide greater clarity and overview.

If an alternative interpretation were to be made from our analysis, we suggest that the single most relevant lever that drives complaint is the degree of flexibility available when drafting Proposals in the current framework. This means proposed amendments (to leases/creditor returns) may vary significantly between Proposals.

Other considerations/recommendations are:

- Length and clarity of CVA Proposals.

Whilst we acknowledge the importance of including the correct level of detail in what are complex documents, we have been surprised by the length and degree of unnecessary repetition in many of the Proposals reviewed.

We can understand that many creditors see the documents as unwieldy, difficult to understand and lacking in clarity. Our own CVA experts struggled at times to fully understand the returns to the various classes’ creditors, so we believe it is vital that adequate summaries are provided in an early section of each Proposal, so that all creditors should be able quickly and easily to understand their options/returns.

As a minimum standard we believe all CVA Proposals should include:

- Executive summaries which clearly state the rights of all categories of creditors;

- Standardisation of certain tables in the executive summary to include the returns for each creditor category (including excluded creditors), including; p/£ to be paid, expected payment dates, £ debt in the creditor category and then clear guidance regarding the location of any creditor schedules including name, address, and the amount owed to the creditors in each category. This will ensure that each creditor is clear how much they will receive.

- Inclusion of a post-CVA balance sheet (illustrating the impact of the CVA), together with a forecast profit and loss account and cash flow for the duration of the CVA, with reference to any profit sharing/upside, or why this has not been included.

- Consultation with certain key bodies/ stakeholders. In order to increase transparency and encourage more meaningful consultation with landlords, SIP 3.2 should include a trigger point (e.g. number of landlords/leases) for the Directors/Nominees to consult with the BPF, on behalf of their members. Consultation should take place within a sensible timeframe and prior to launching the Proposals. This would allow the BPF to review the Proposals, consult with impacted members and respond to the Directors/Nominees, providing feedback and any proposed amendments. The Directors/Nominees should then formally respond to the BPF and include a copy of the response in the Proposals. The trigger point/ thresholds for such consultation is not within the scope of this report, nor in the analysis performed, and would need industry consultation and debate.

- Comparison with other procedures (in particular a Restructuring Plan). The CVA currently sits within a range of solutions available to a company in financial difficulty in the UK, and to the restructuring professionals advising such companies. Whilst it is not in scope to compare and contrast the other solutions it is worth noting that there are some inevitable compromises in the CVA solution to ensure that it can remain a flexible tool and fit into this suite of options. Not only is flexibility a key advantage of the CVA, but the relative lack of Court involvement, when contrasted with a Restructuring Plan, means costs ought to be considerably lower as a result.

- Addressing complaints in respect of vote ‘swamping’. Any such exclusion of unconnected and uncompromised creditors would represent a fundamental change to the CVA process and given the low potential return in the relevant alternative (should the Proposals be rejected), uncompromised creditors may argue that they still have a very significant interest in the voting process. We suggest that any such proposed change would require consultation with the relevant stakeholders/ industry.