A study of work and health transitions: analysis of Understanding Society

Published 20 July 2021

A study of work and health transitions: analysis of understanding society

DWP research report no. 994

A report of research carried out by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research on behalf of the Work and Health Unit.

© Crown copyright 2021.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit the Open Government Licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU,or email: psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at DWP research reports.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email: socialresearch@dwp.gsi.gov.uk

First published 2021.

ISBN 978-1-78659-273-6

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other Government Department

Statement of Compliance

This research complies with the 3 pillars of the Code of Practice for Statistics: trustworthiness, quality and value.

Trustworthiness

This research was conducted, delivered and analysed impartially by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), working to the Government Code of Practice for Statistics Authors: Sergio Salis, Stefan Speckesser, Lea Samek (National Institute of Economic and Social Research) and Paul Bivand (Learning and Work Institute)

Quality

The research was carried out using established quantitative and qualitative research methods, with relevant academic experts consulted over methodology and application of techniques. Details of methodological choice and application, as well as limitations of results are documented.

The research has been quality assured using NIESR’s internal quality checking processes, which have been shared with the Work and Health Unit.

The report has been checked thoroughly by Work and Health Unit analysts to ensure it meets the highest standards of analysis and drafting

Value of this research

Findings from this report will help us consider more sophisticated approaches to the targeting and timing of policy interventions, as well as providing direction to future research.

The research also contributes to the growing evidence base to support work and health policy.

Acknowledgements

This report was commissioned by the Work and Health Unit, jointly sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). The research was carried out by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) in collaboration with Paul Bivand (Learning and Work Institute). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of colleagues at the DWP, in particular H Patel and Lily Shannon. This report also benefited from the advice of a steering group composed of Mike Daly and Ellen Flint (DWP), Melanie Jones (University of Cardiff), and Stephen Bevan (Institute for Employment Studies). Thanks are also due to Prof. Stephen Jenkins (London School of Economics and Political Science), Pilar García-Gómez (Erasmus School of Economics) and Ralf Wilke (Copenhagen Business School) for helpful advice on the survival analysis. Finally, the project team would like to thank the Understanding Society User Support team and Andrea Stochino, an intern at NIESR funded under the Erasmus+ traineeship scheme, for technical support.

The authors

This report was produced by Sergio Salis, Stefan Speckesser and Lea Samek (National Institute of Economic and Social Research), and Paul Bivand (Learning and Work Institute).

Definitions within this report

Incident health problem

The health literature uses the term incident to refer to the occurrence of a new case of a health problem. Incidence should not be confused with prevalence, which refers to the proportion of a population with a given health condition at a point in time. Throughout the report, the terms ‘incident health problem’ and ‘onset of poor health’ are used interchangeably.

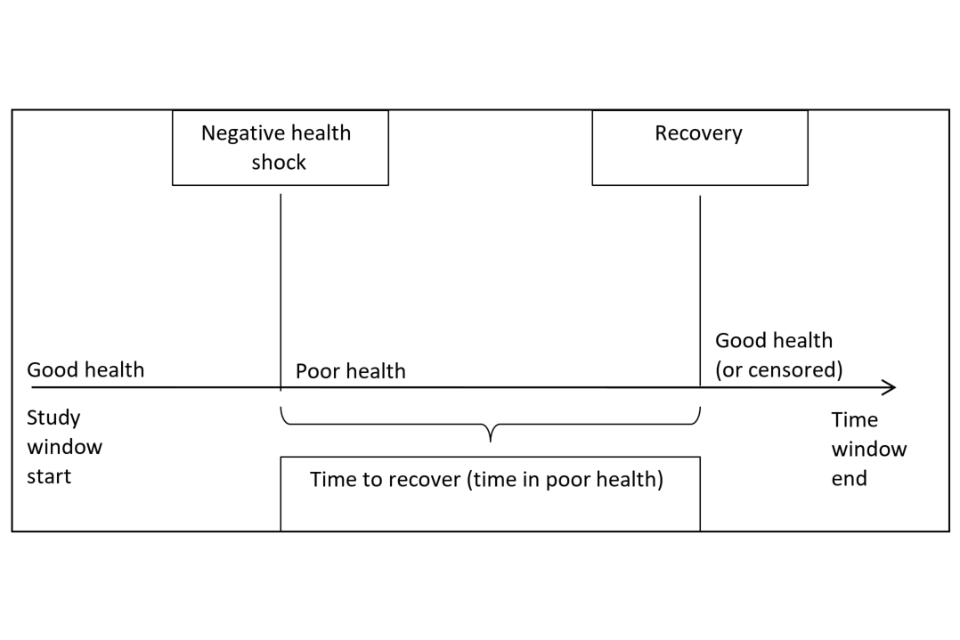

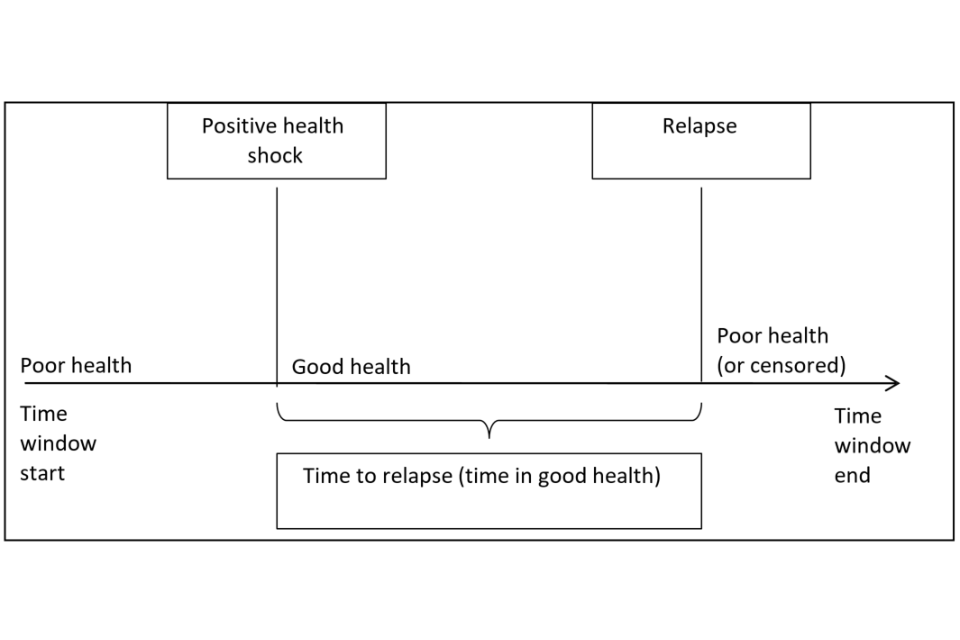

Health transition

A health transition denotes a change from one health state to another between 2 consecutive time points. A move from poor to good health is called a positive health transition, while a negative health transition reflects a switch from good to poor health. In this report the term ‘health shock’ is used interchangeably with ‘health transition’.

Work transition

A work transition denotes a change from one labour market status to another between 2 consecutive points in time. Changing status from employed to not employed (or from economically active to inactive) is considered a negative work transition, while moving from not employed to employed (or from economically inactive to active) is a positive work transition. For those who remain employed between the 2 time points considered, moving from part to full-time, temporary to permanent, dissatisfactory to satisfactory, or low to high-pay jobs are considered positive work transitions. The opposite changes reflect negative work transitions.

Impact

The impact of health transitions on work transitions is a measure of how experiencing health transitions alters the likelihood of undergoing a work transition for the individuals observed. Technically, it is calculated as the difference between the probabilities of undergoing a work transition among those who experienced a health transition and those who did not experience a health transition, after having accounted for important differences between the 2 groups.

Percentage point

A percentage point (ppt) is the unit used to measure the difference between 2 percentages. The impact of health transitions on work transitions is measured in ppts. For example, if the percentage exiting employment among those who experienced onset of a mental health problem is 77% and the percentage exiting employment that would be observed had the same people not experienced the onset (the so called ‘counterfactual’) is estimated at 70%, then we say that onset of a mental health problem increased the percentage exiting employment by 7ppts.

Statistical significance

Statistical significance tests are designed to determine the probability that an observed impact did not occur by chance, that is, a result specific to the sample and not reflective of the wider population from which it was drawn. If the assumptions about the data that underpin the application of the test applied hold true, then the smaller the statistical significance threshold an impact estimate is determined to exceed, the higher the likelihood that the apparent impact observed in the sample may represent a true association in the population of interest. The p-value of an impact estimate represents the probability of finding the result in a sample even if no such association exists in the population. In the context of this report, an impact estimate which is found to be statistically significant at the 5% (1%) level means that we accord a high (very high) probability that the estimate provides a true measure of the association of health transitions with work transitions.

Chronic conditions

The chronic conditions considered are asthma, arthritis, congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, emphysema, hyperthyroidism or an over-active thyroid, hypothyroidism or an under-active thyroid, chronic bronchitis, any kind of liver condition, cancer or malignancy, diabetes, epilepsy, high blood pressure, clinical depression, heart attack or myocardial infarction, and stroke. These are the only conditions explicitly referenced in the data.

General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) is a 12-item questionnaire generally used to identify non-psychotic and minor psychiatric conditions. It includes questions aimed at exploring aspects of an individual’s daily life, including: anxiety, depression, feelings of incompetence, difficulty coping with problems and sleep disturbance. Specifically, respondents are asked to report, using a 4-point Likert scale, the extent to which they have recently been feeling that they have been: able to concentrate on doing things, able to sleep despite worries, playing a useful part in things, able to make decisions, under strain, able to overcome problems, able to enjoy daily activities, able to face problems, feeling unhappy or depressed, losing confidence in themselves, thinking of being worthless, and feeling reasonably happy. For each item, the individual’s answer is converted into a single dummy variable indicating whether a symptom of distress existed. Adding the value of the 12 dichotomous variables, a single indicator of mental health problem or psychological distress ranging 0 to 12 is obtained, denoting the number of symptoms of distress for the individual.

Functional impairments

Functional impairments (or limitations) include those relating to mobility (moving around at home and walking), lifting, carrying or moving objects, manual dexterity (using hands to carry out everyday tasks), continence (bladder and bowel control), hearing (apart from using a standard hearing aid), sight (apart from wearing standard glasses), communication or speech problems, memory or ability to concentrate, learn or understand, recognising when you are in physical danger, physical co-ordination (for example, balance), difficulties with own personal care, and other health problem or disability.

Executive summary

Background

Disabled people typically fare worse in the labour market. Between April and June 2018, while the UK employment rate reached a historic high of 75.6%, only half of disabled people were in work. Although the disability employment gap (the difference between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people) has narrowed by 5 percentage points from 34 to 29 percentage points since 2014, the prevalence of disability and ill-health among the working-age population has been rising over time. Working age ill-health, which prevents people attending work or being in a job due to illness or disability, comes at a considerable cost to the UK economy of around £100 billion a year (Work and Health Unit, 2017).

To provide contextual evidence for the government’s strategy for improving employment among disabled people or people with health conditions, this study examines transitions (changes) in health and work status experienced by working-age people (16 to 64 years old). It uses a large-scale longitudinal survey, Understanding Society (USoc), to provide fresh empirical evidence on the complex relationship between health and work transitions, which is arguably under-explored.

More specifically, the analysis aims to explore:

- what impacts changes in health have on work outcomes and the extent to which those impacts vary by individual characteristics;

- the durations of health transitions (length of time in good or poor health) across different groups, and the individual characteristics affecting the probability of experiencing these transitions; and

- the patterns of people’s employment status and job satisfaction in the medium term following health transitions

The research seeks to improve understanding of which types of people are most likely to experience deteriorations or improvements in health, and to identify factors which might mitigate the negative labour market consequences (or maximise the positive effects) of health shocks.

Methodology

This study uses data from 8 waves of USoc. USoc is a longitudinal survey of around 40,000 UK households recruited between 2009 and 2011, and re-interviewed at around one-year intervals. USoc contains information on demographics and circumstances of individuals and their households (including work, health, income and education characteristics), enabling analysis of recent trends and patterns in health and work.

In this study, a health transition is defined as either an onset of poor health or an incident health problem (negative health transition) or an exit from poor health (positive health transition). Five different definitions of poor health are considered: poor self-assessed general health, the existence of a mental health problem or psychological distress, self-reported long-term disability or illness, self-reported long-term disability or illness limiting daily activities (functional impairment), and having one or more chronic conditions.

Work transitions include both changes in an individual’s labour market status over time and, for those who remain employed, in their work conditions. Changes in an individual’s labour market status include transitions from employment to non-employment and from economic activity to inactivity (negative work transitions), and vice versa (positive work transitions). Positive in-work transitions include moves from low to high pay, part to full-time, temporary to permanent, and dissatisfactory to satisfactory jobs. In-work transitions in the opposite direction denote negative work transitions.

These transitions were explored using 3 different analytical approaches:

- assessing the association between transitions in health and subsequent transitions in employment status, and identifying risk factors, using multiple logistic regression. The impact of incident poor health and exit from poor health on changes in labour market status or work conditions is assessed using logistic regression models. Impacts are estimated as the difference in the probabilities of experiencing work transitions between those who undergo a health transition and those who do not. The methodology controls for baseline differences between these 2 groups in terms of important individual characteristics and circumstances. The identification of impact moderators is implemented using interaction terms in the regression models

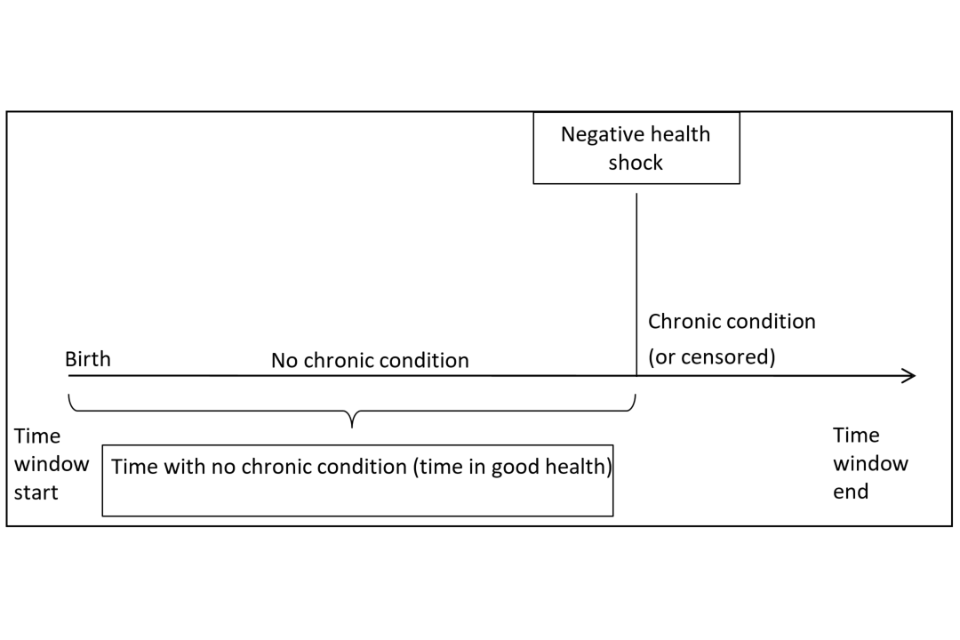

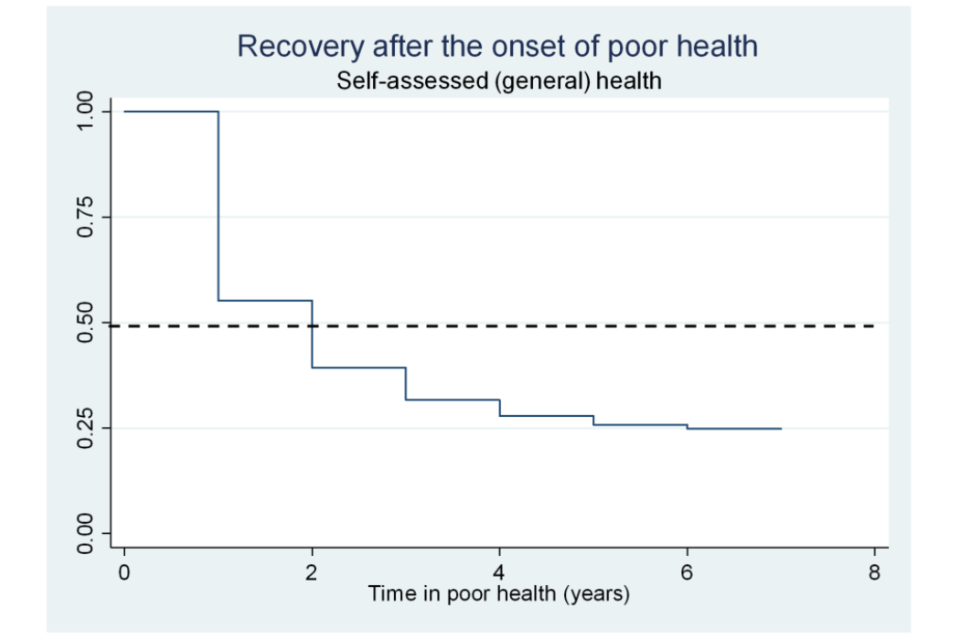

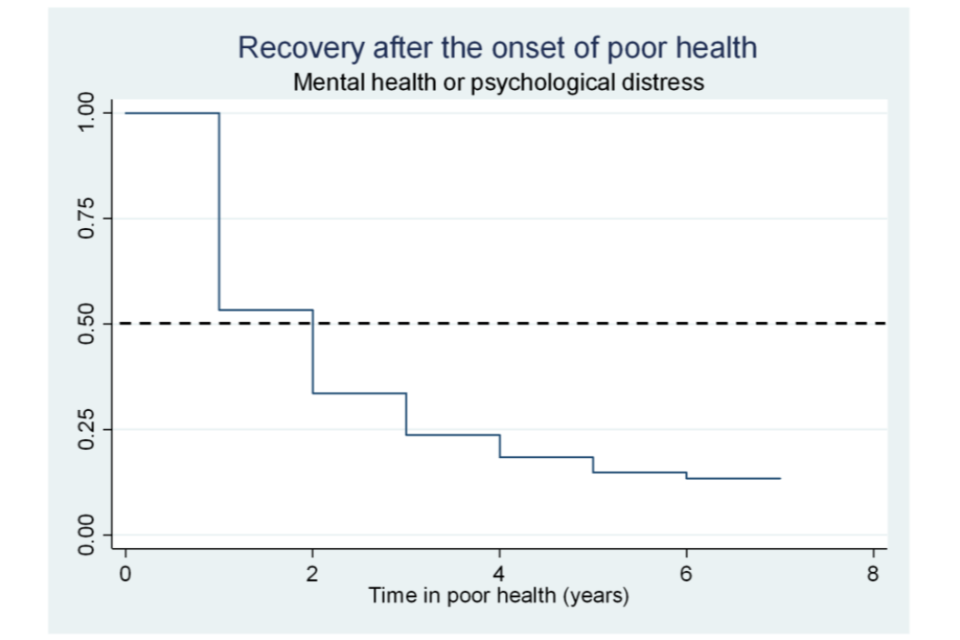

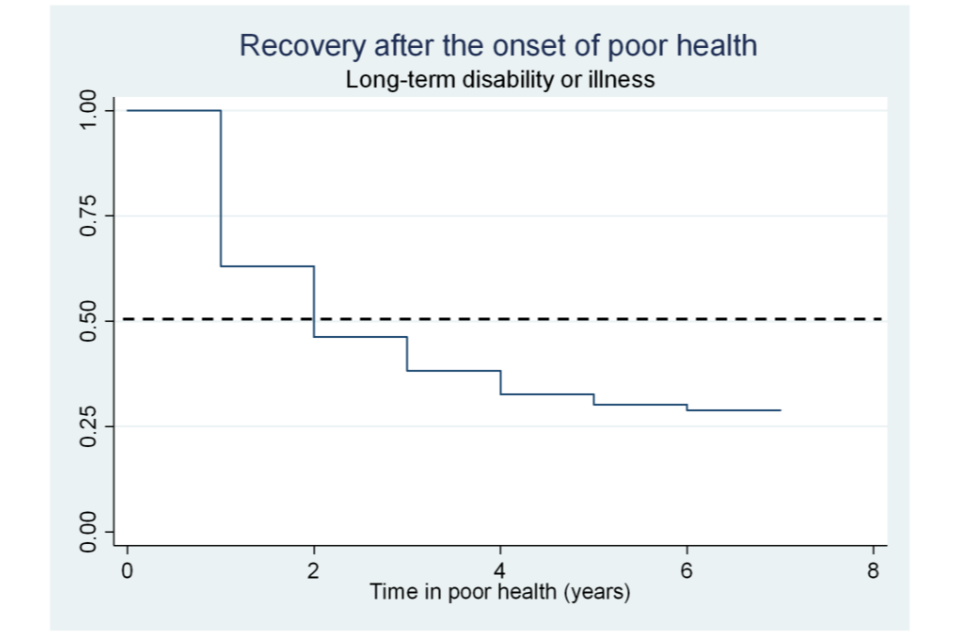

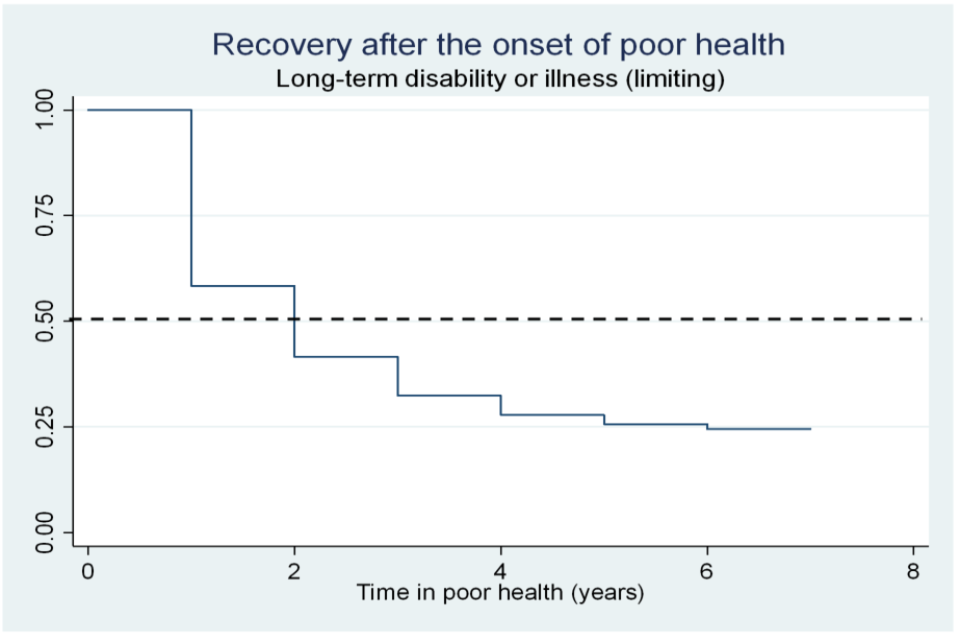

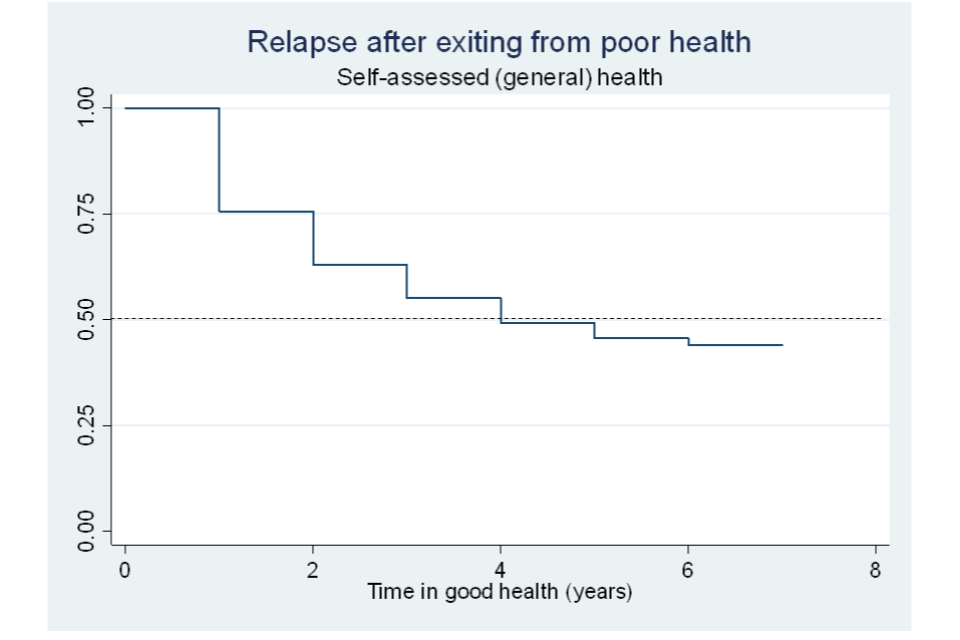

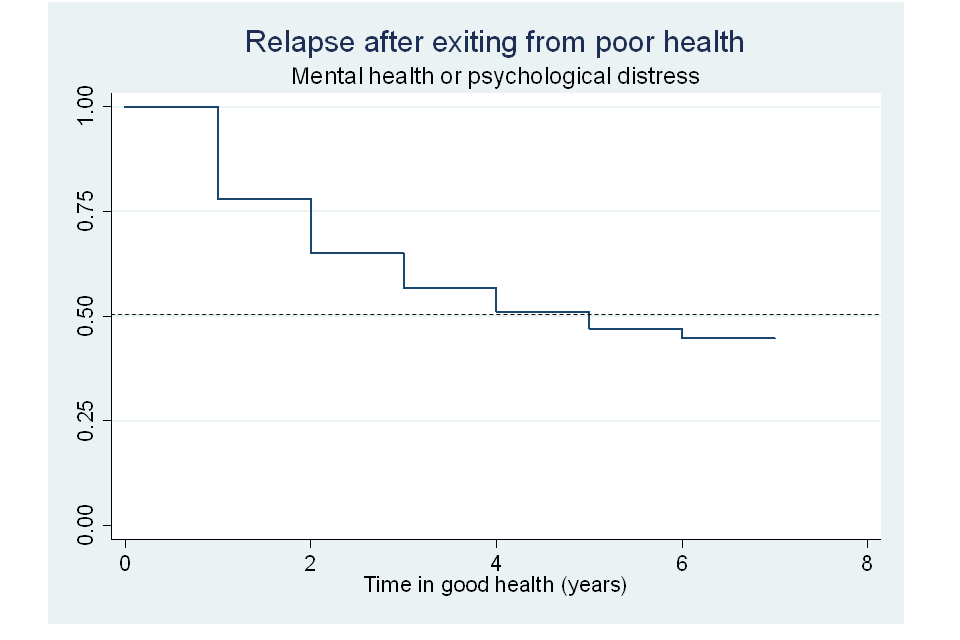

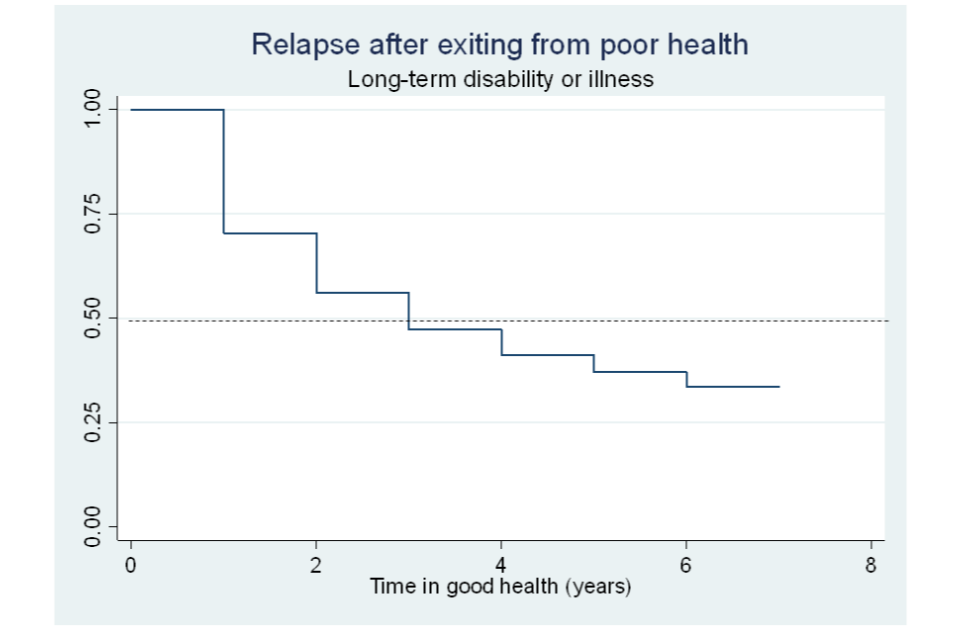

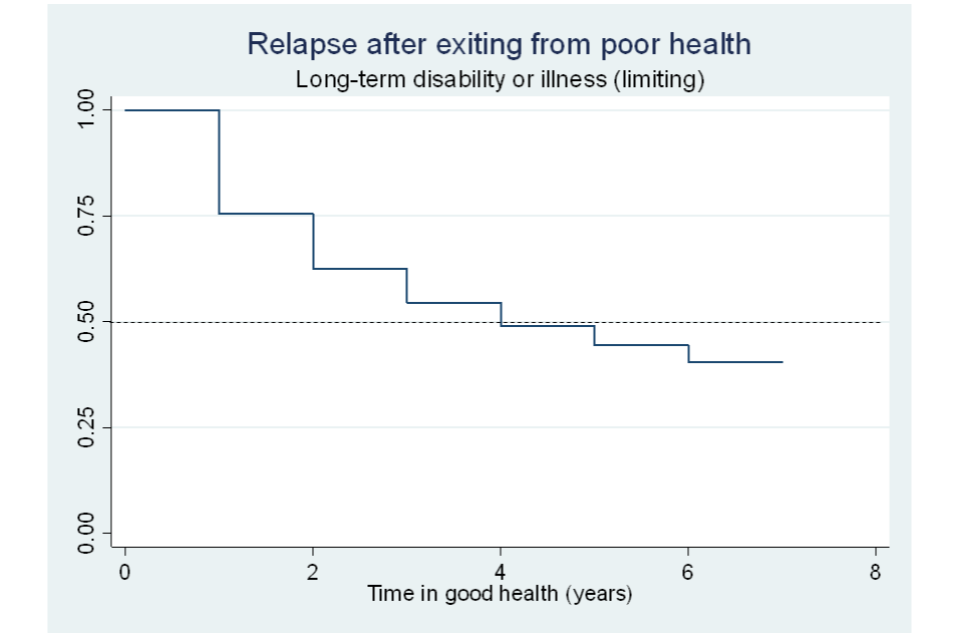

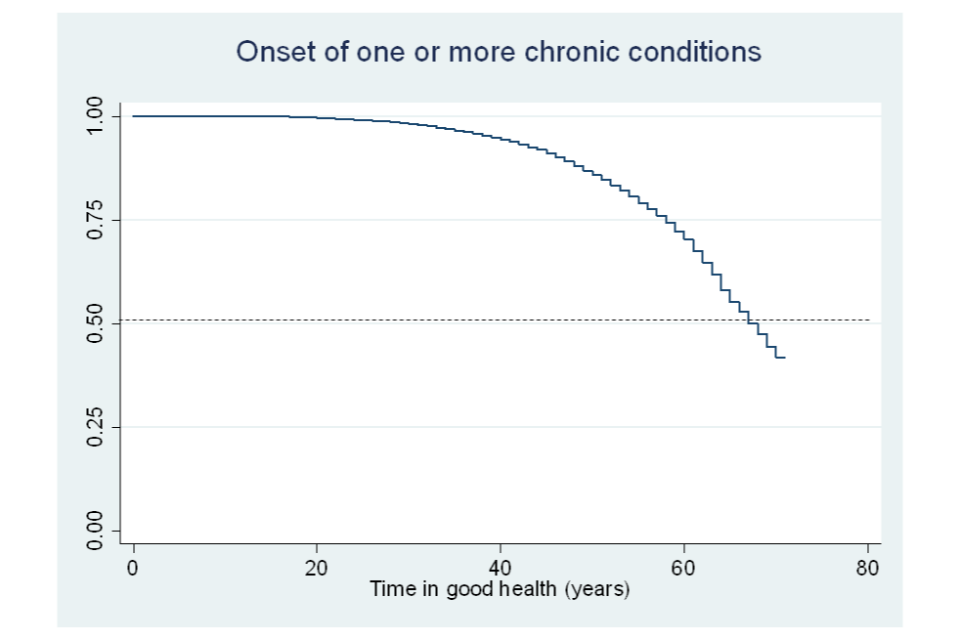

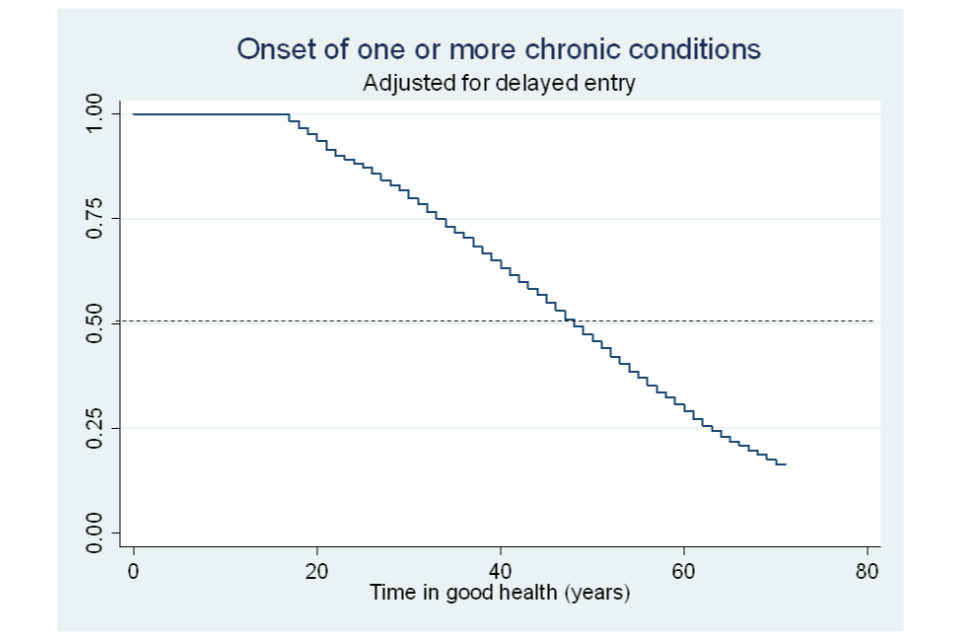

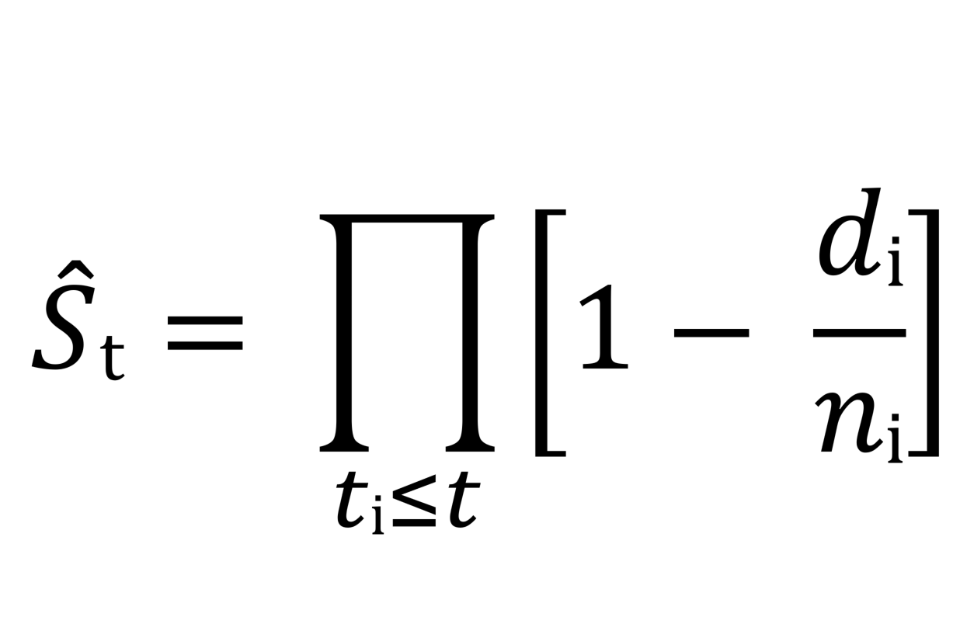

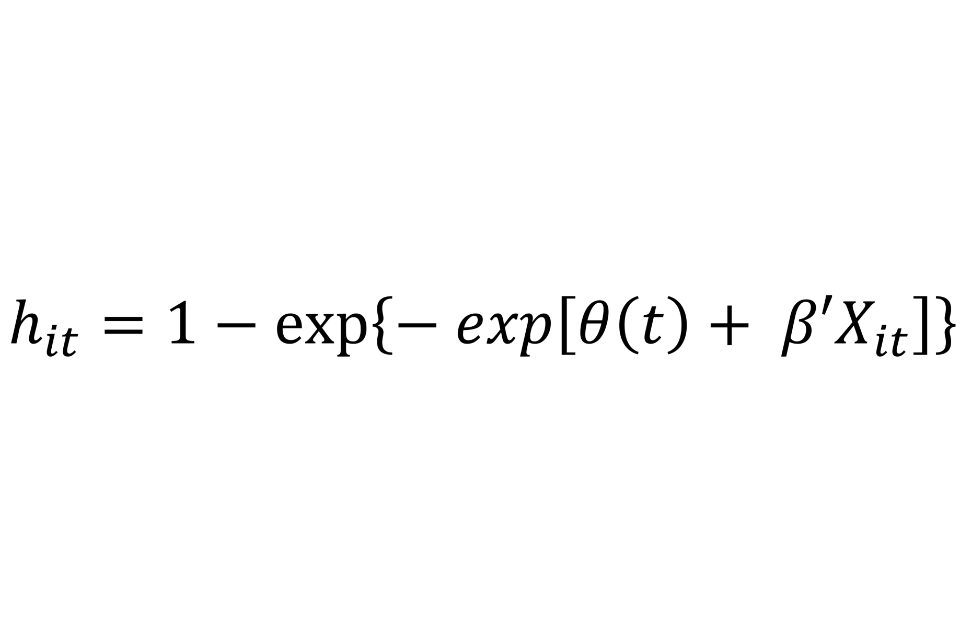

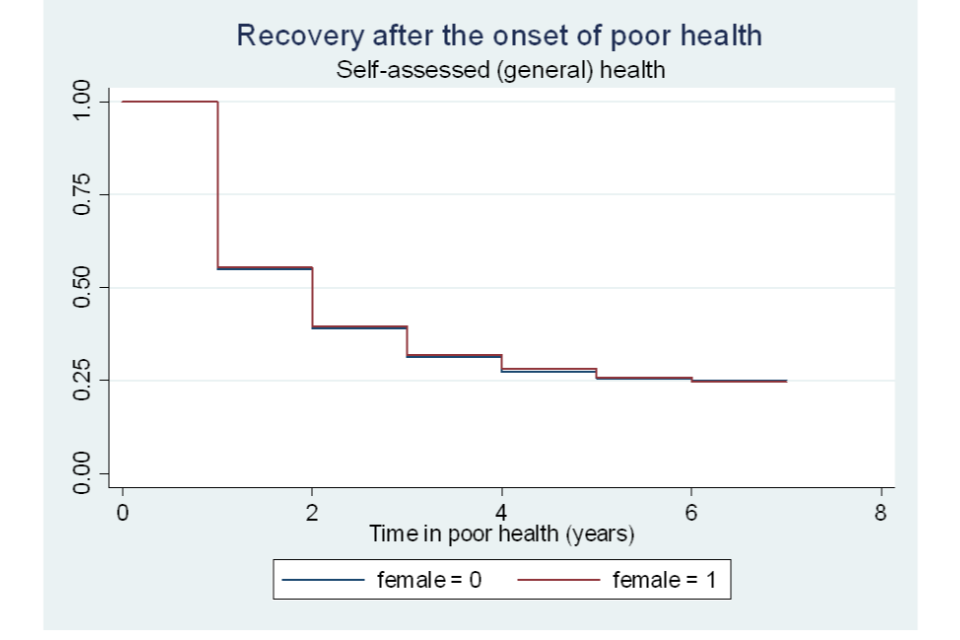

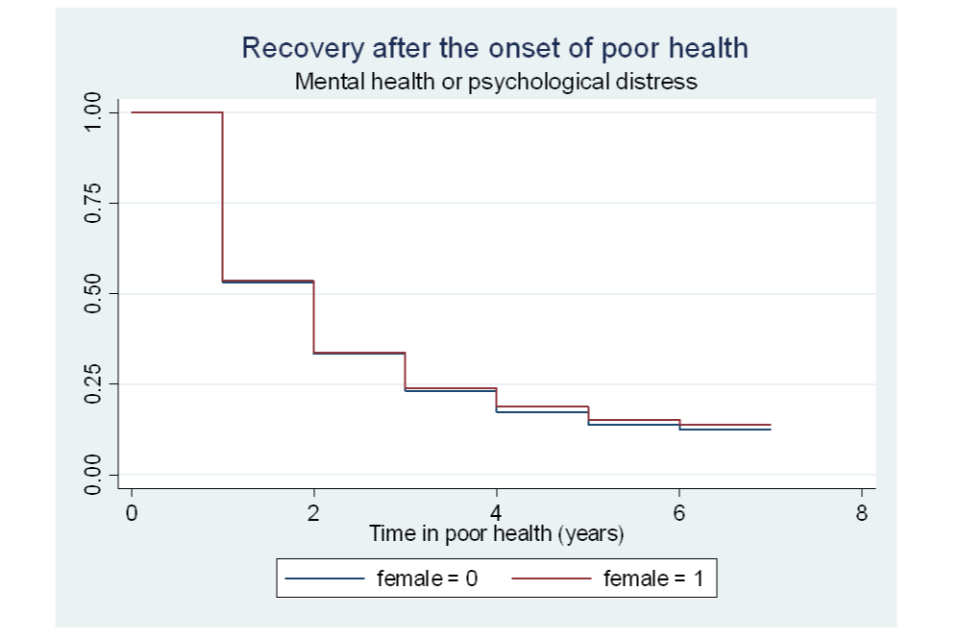

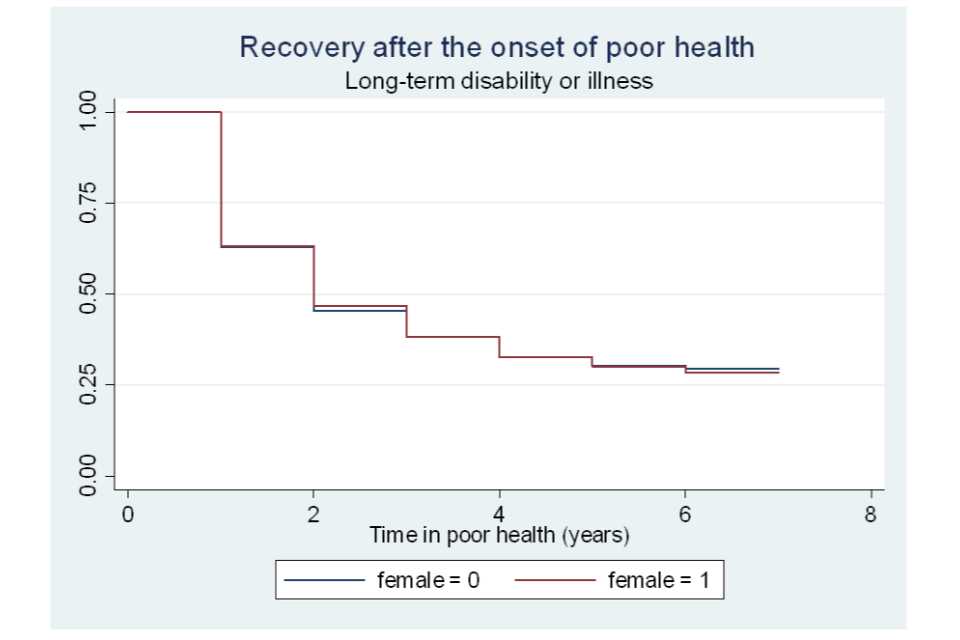

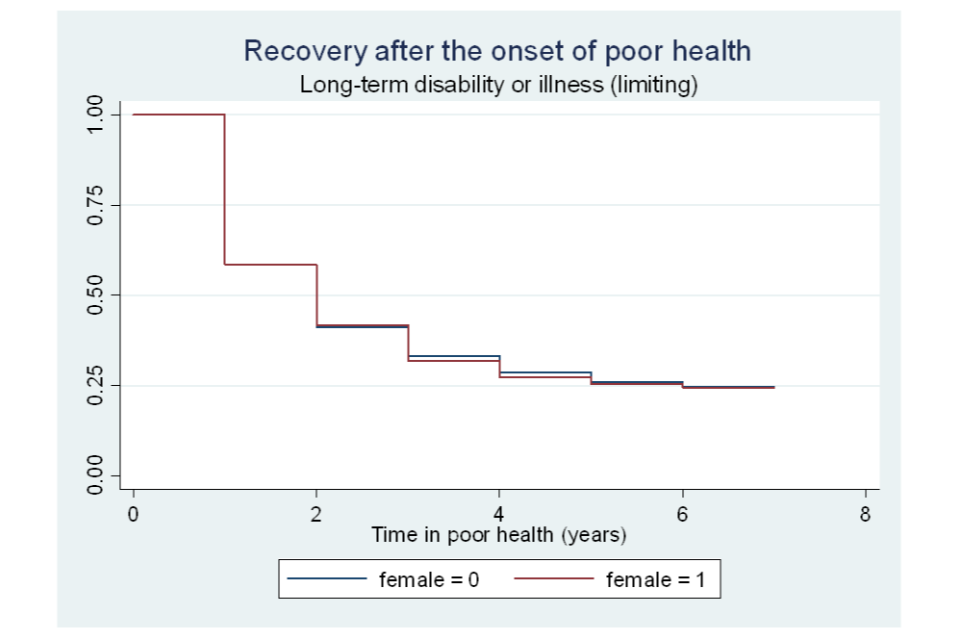

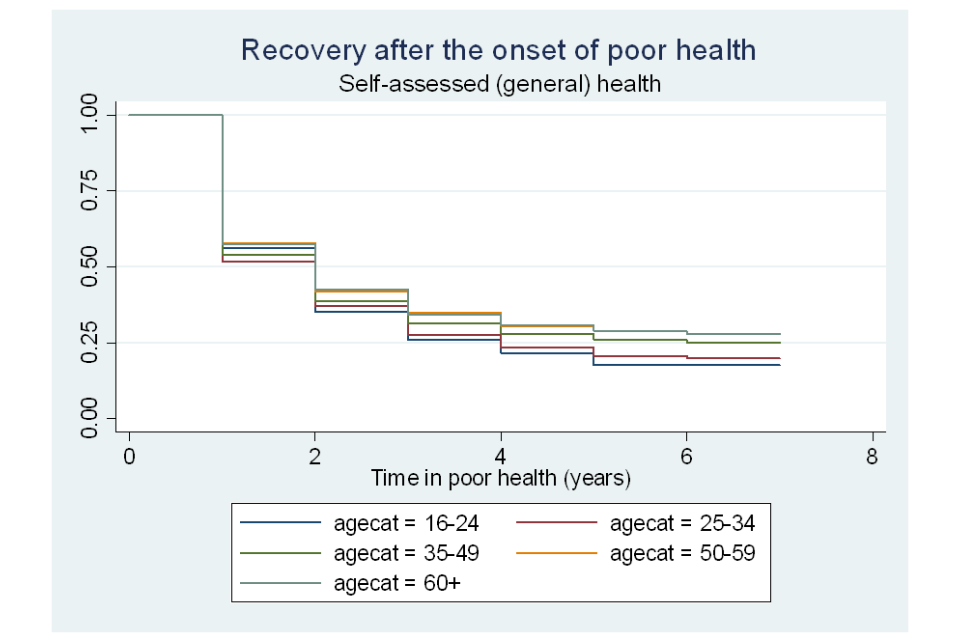

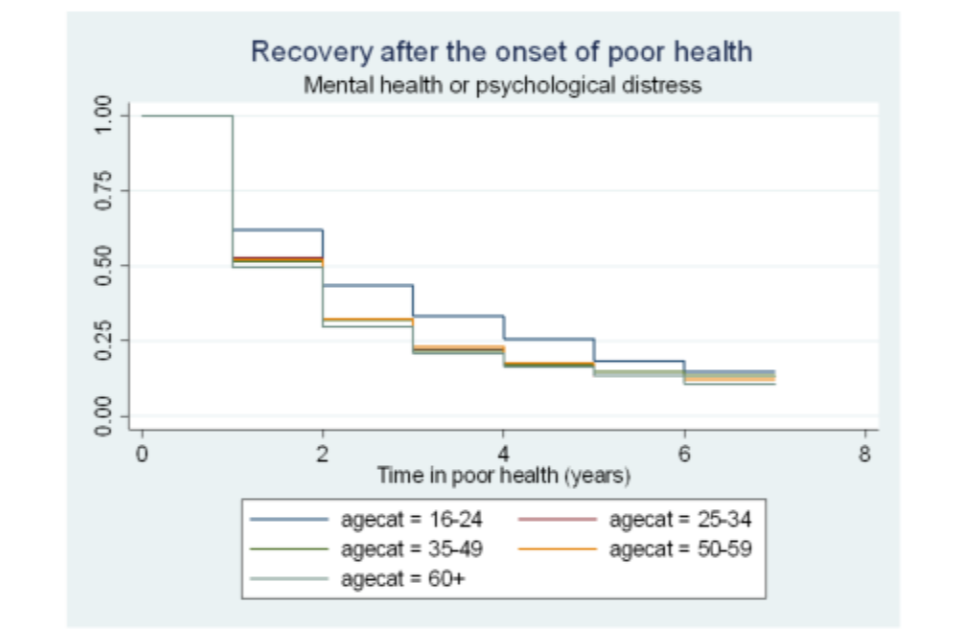

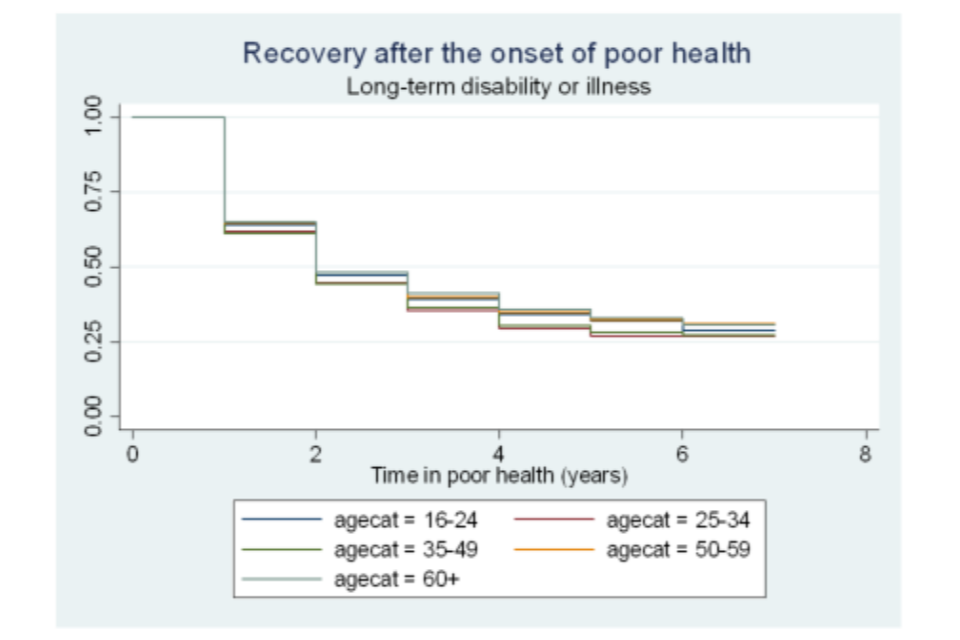

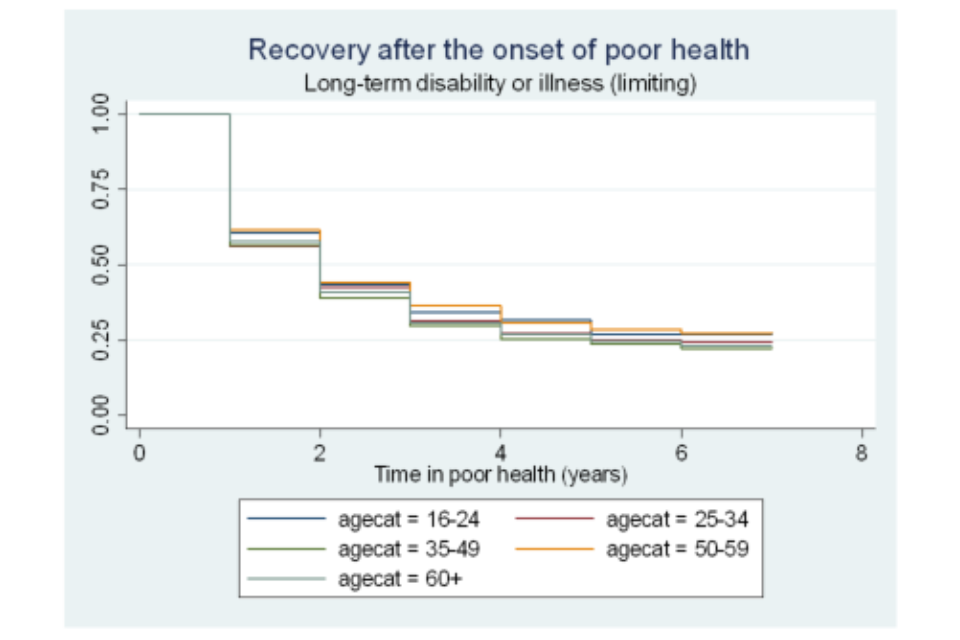

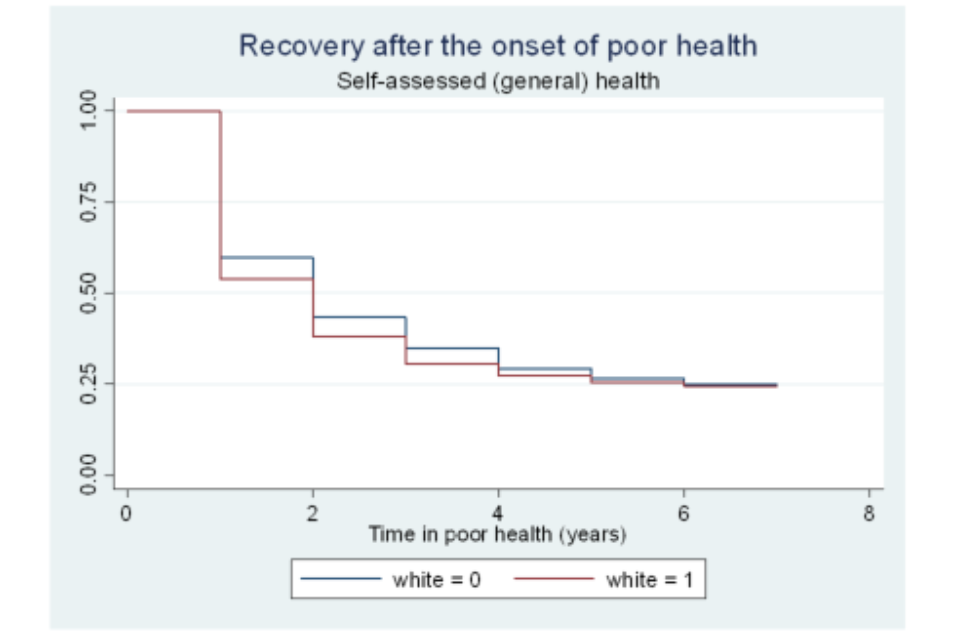

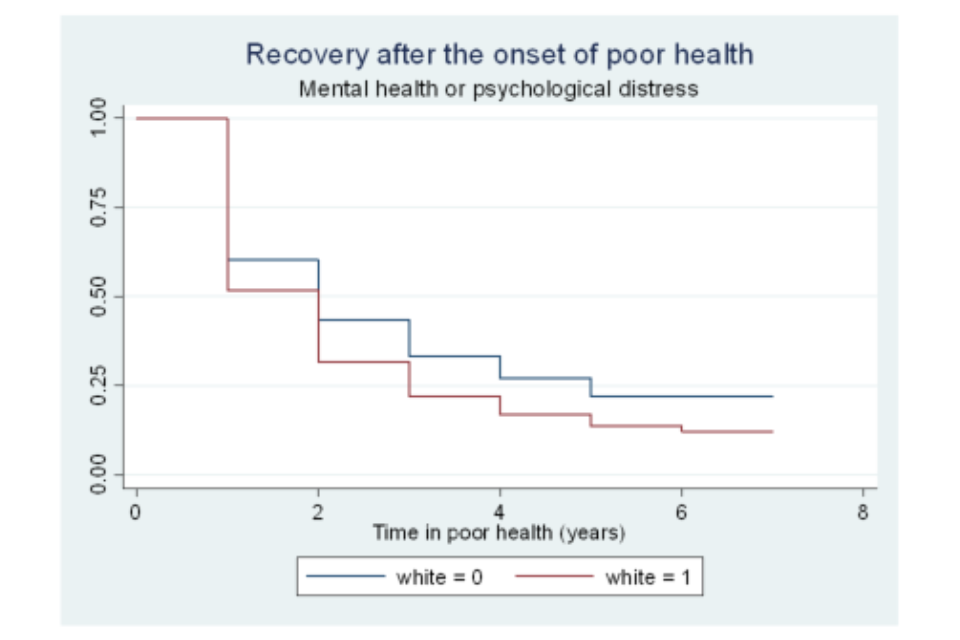

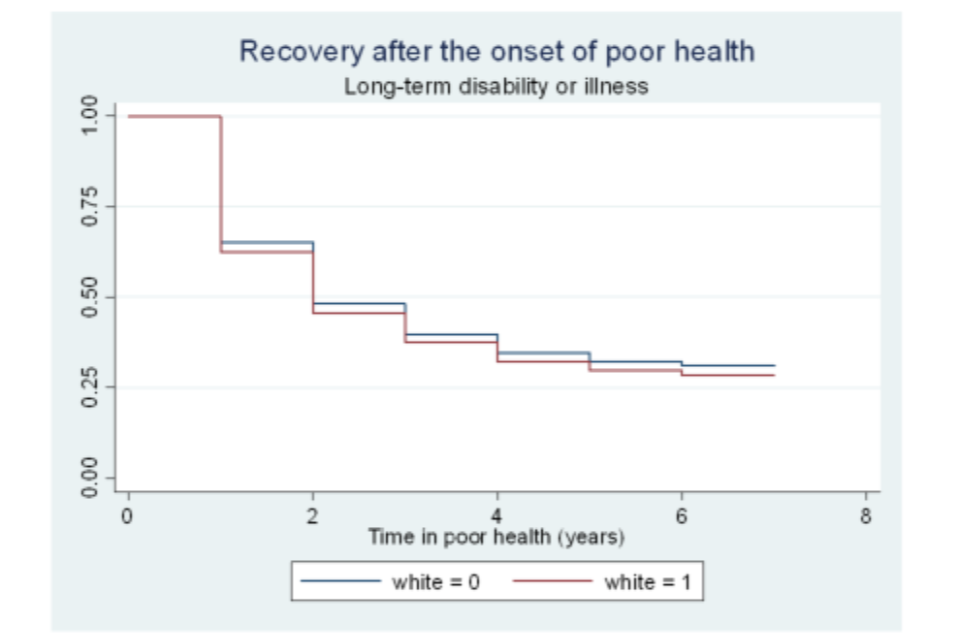

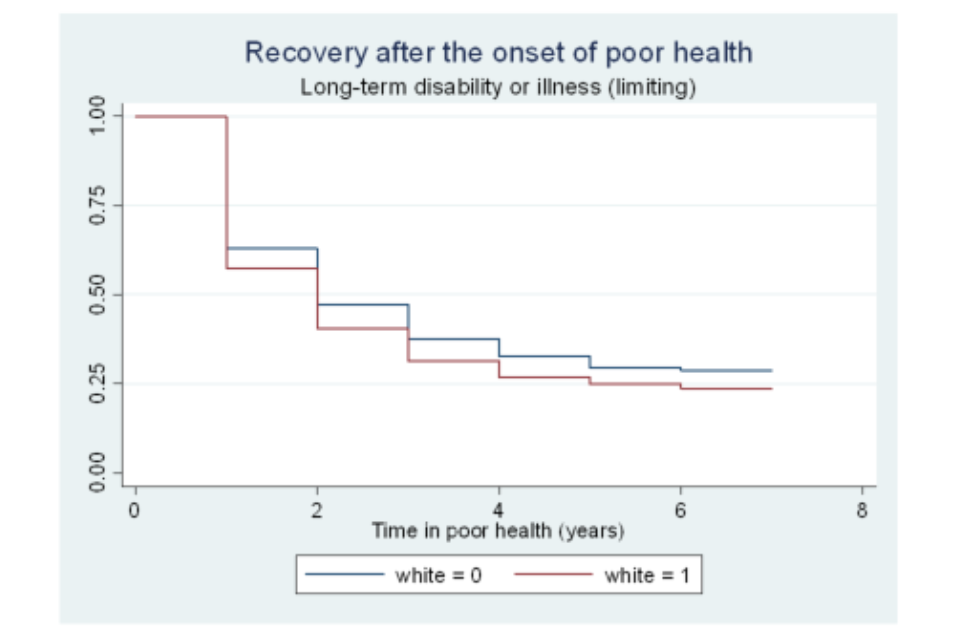

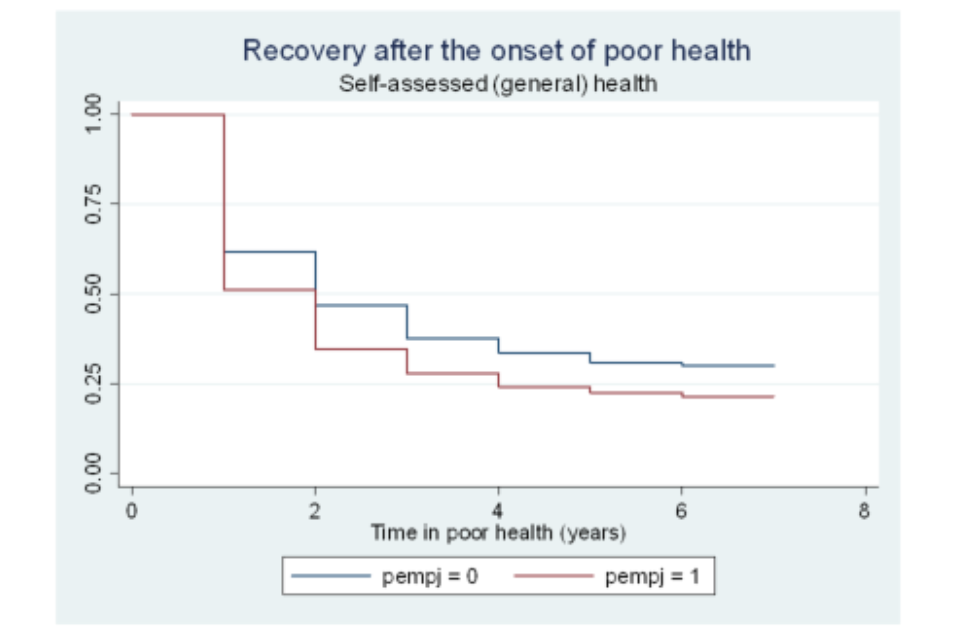

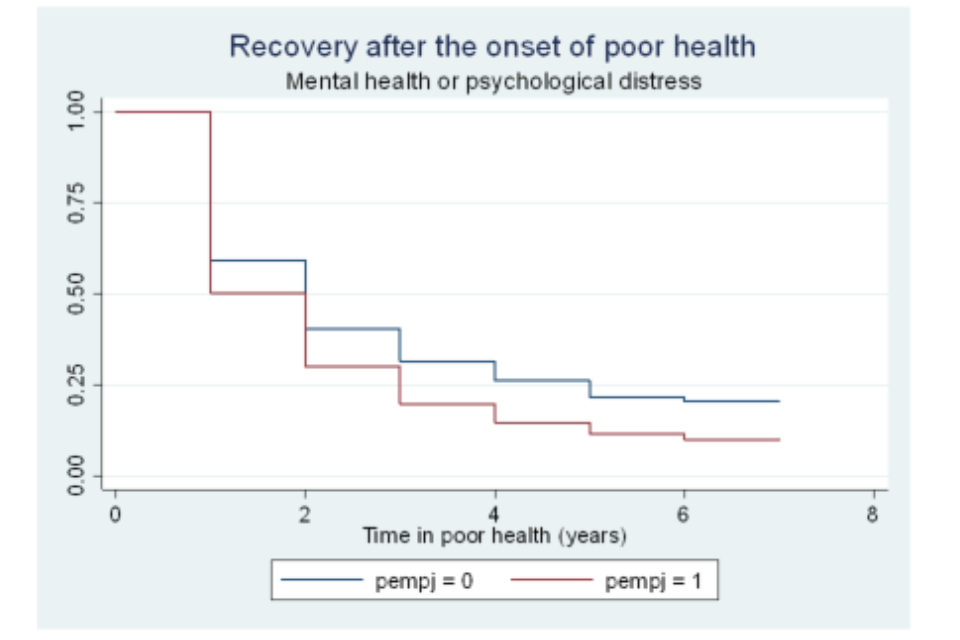

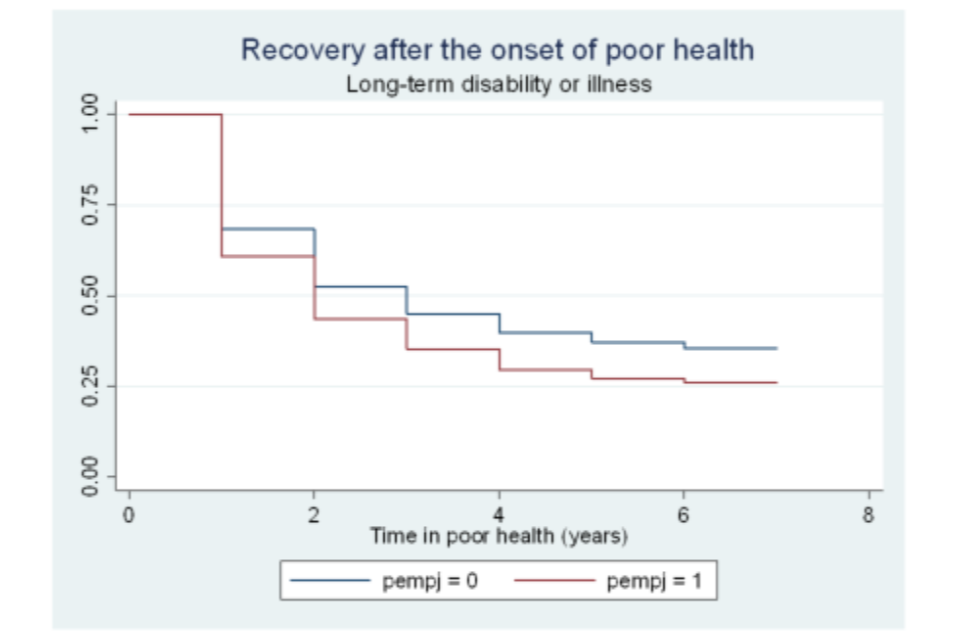

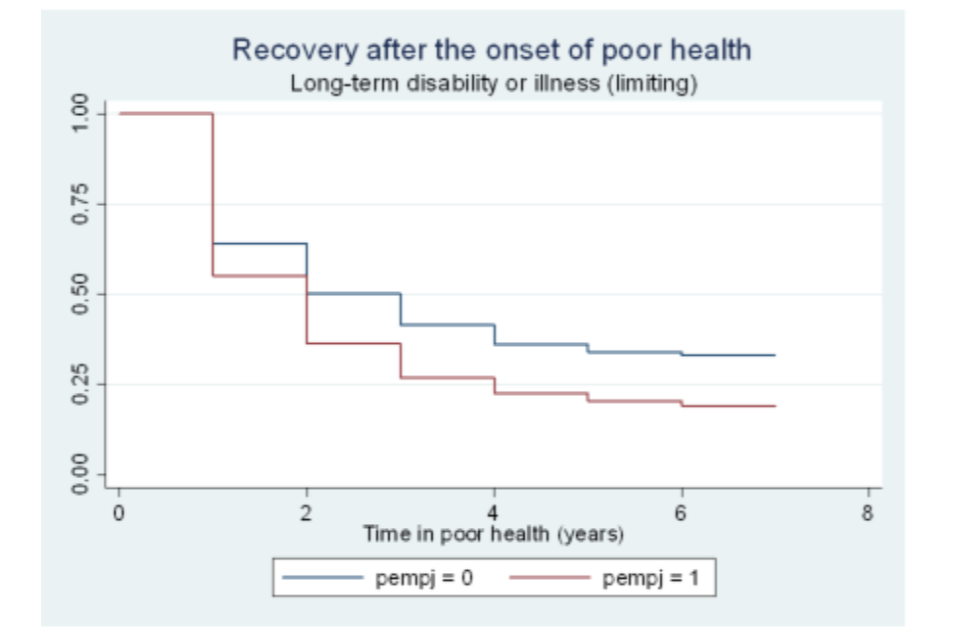

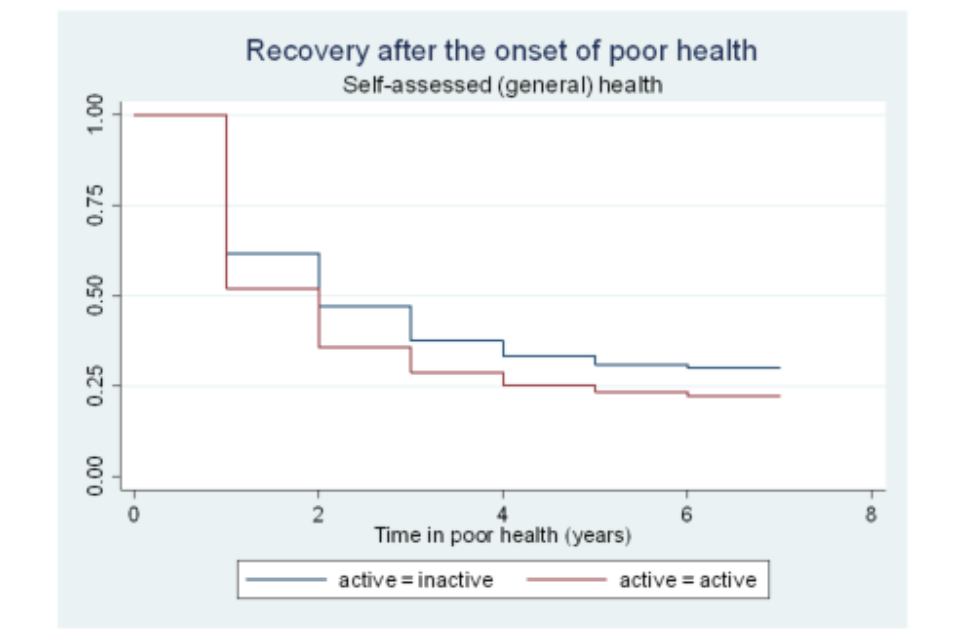

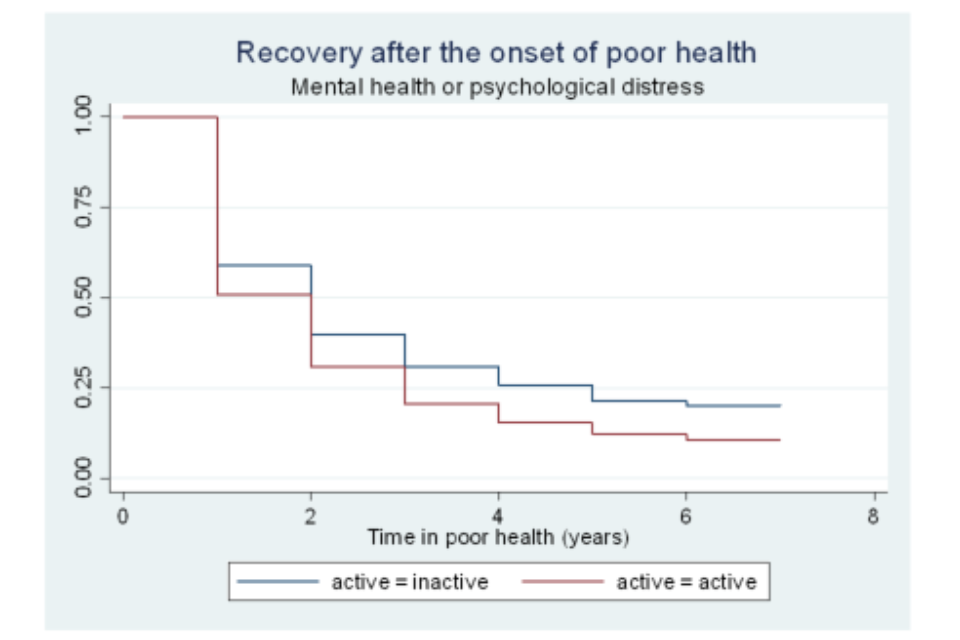

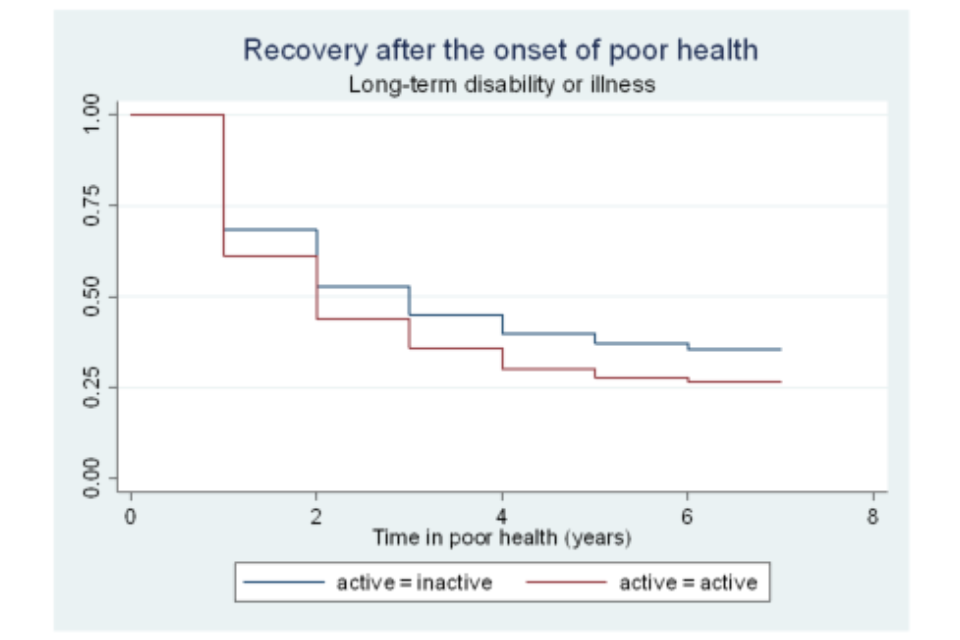

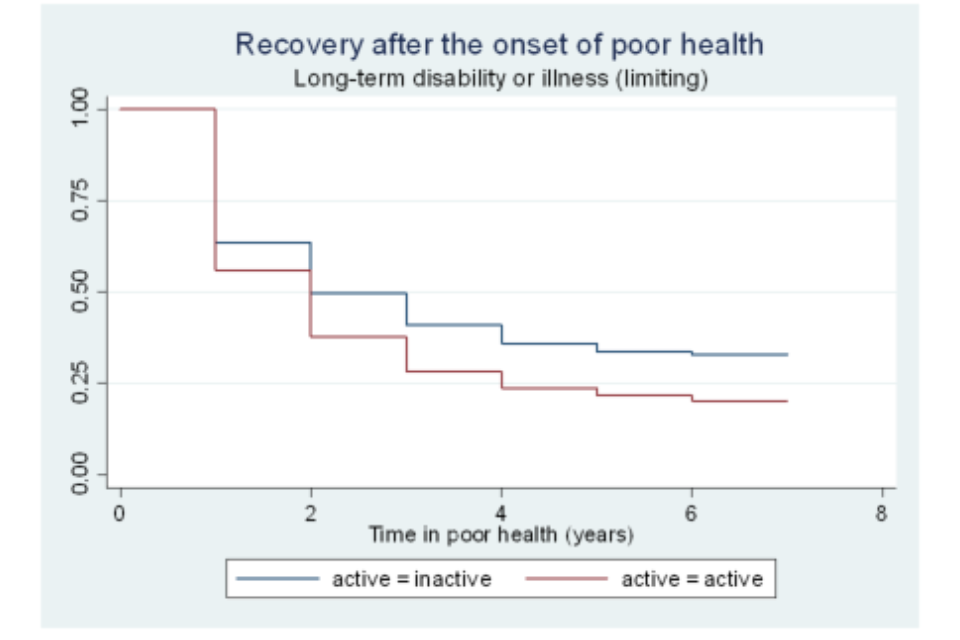

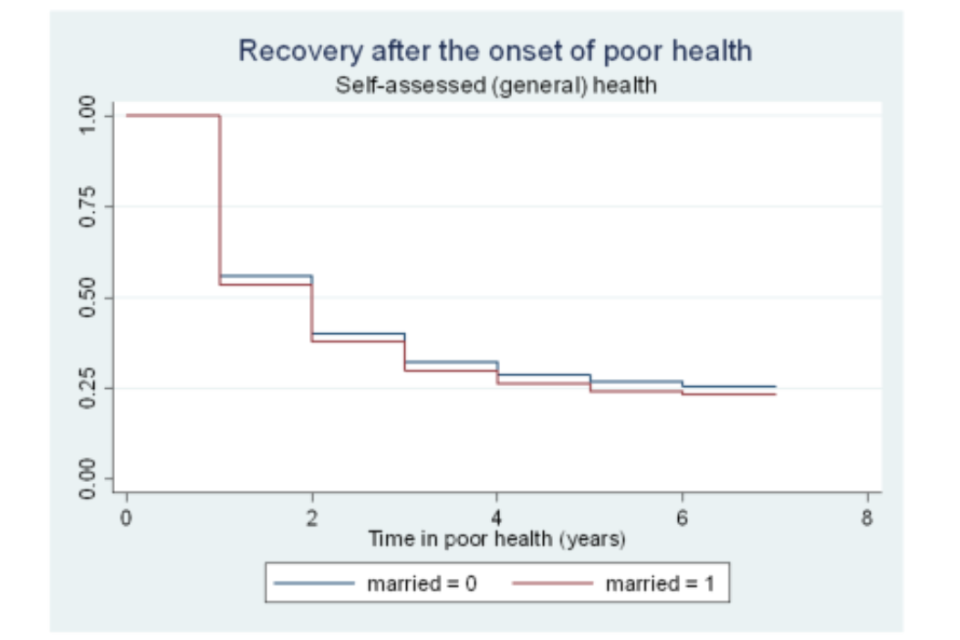

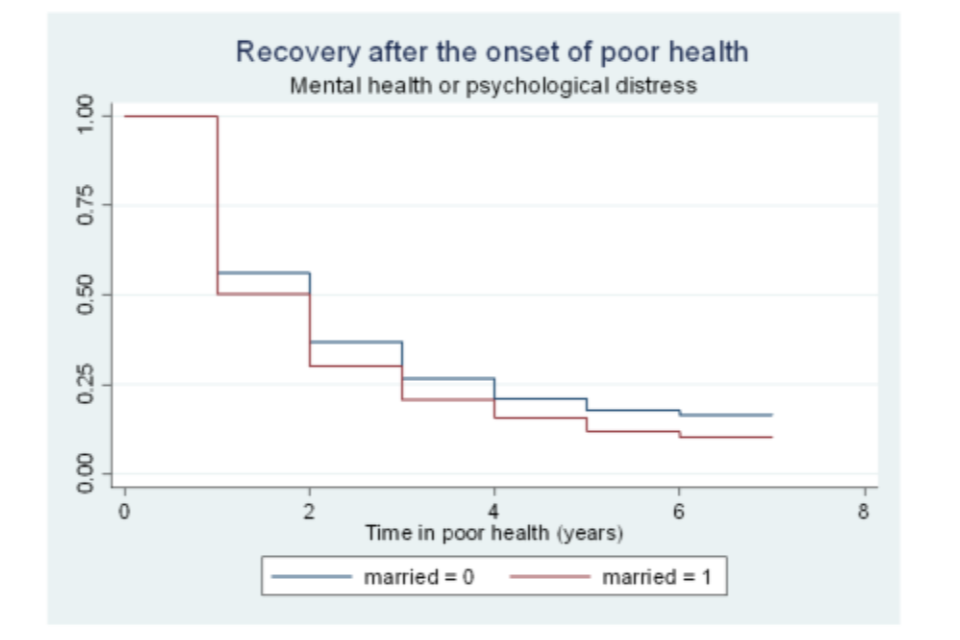

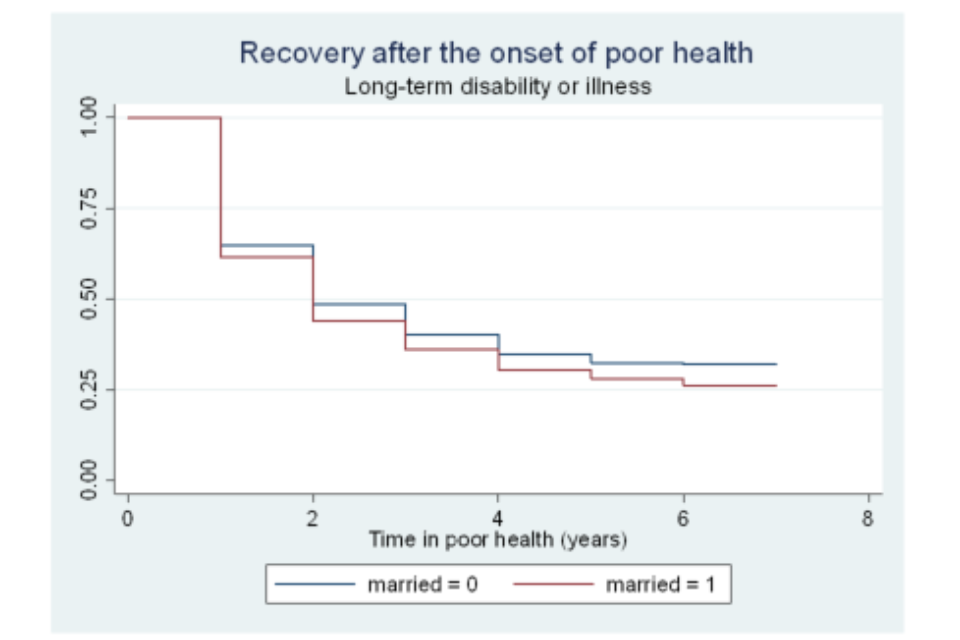

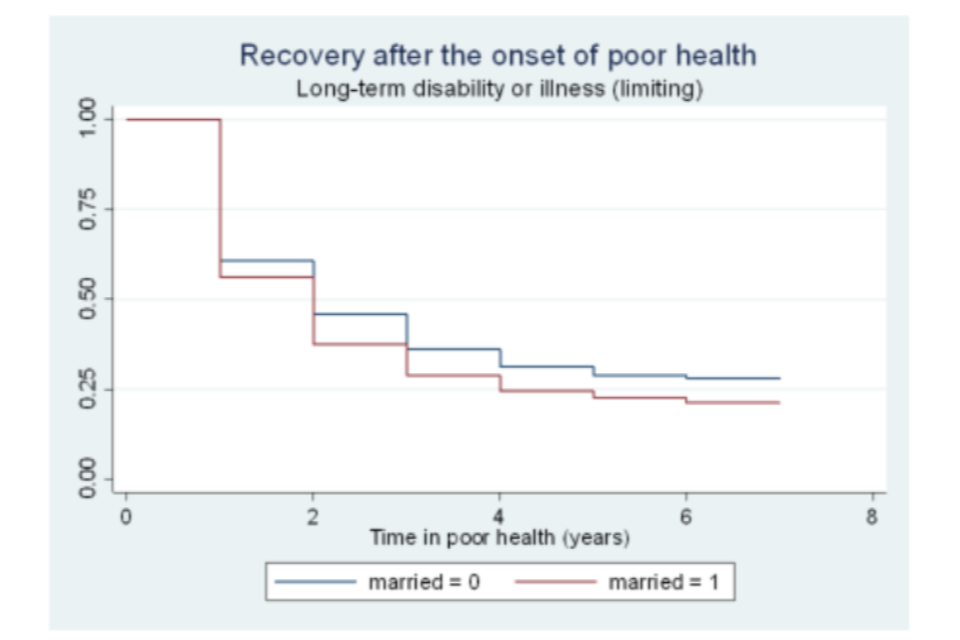

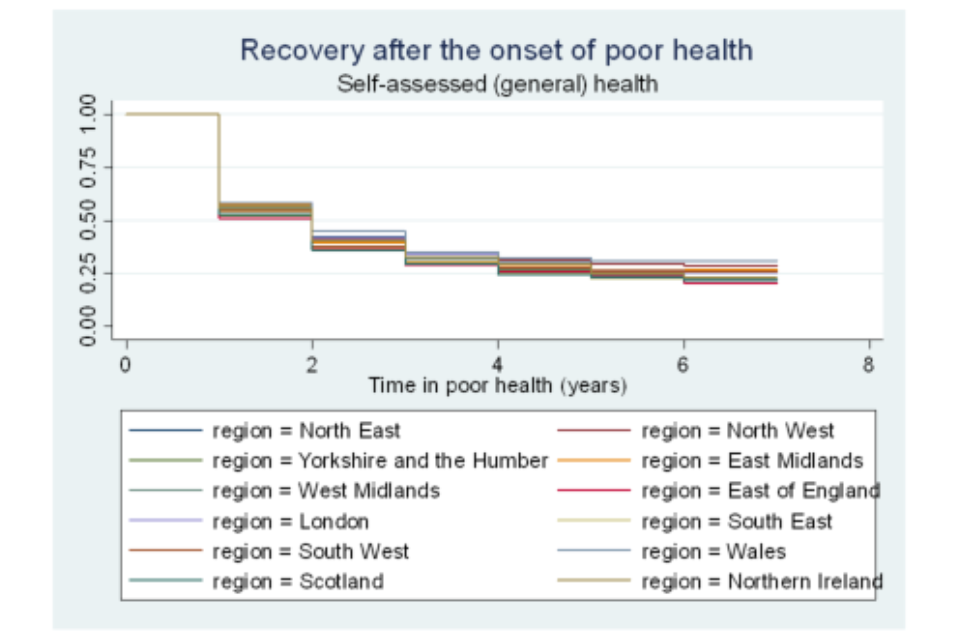

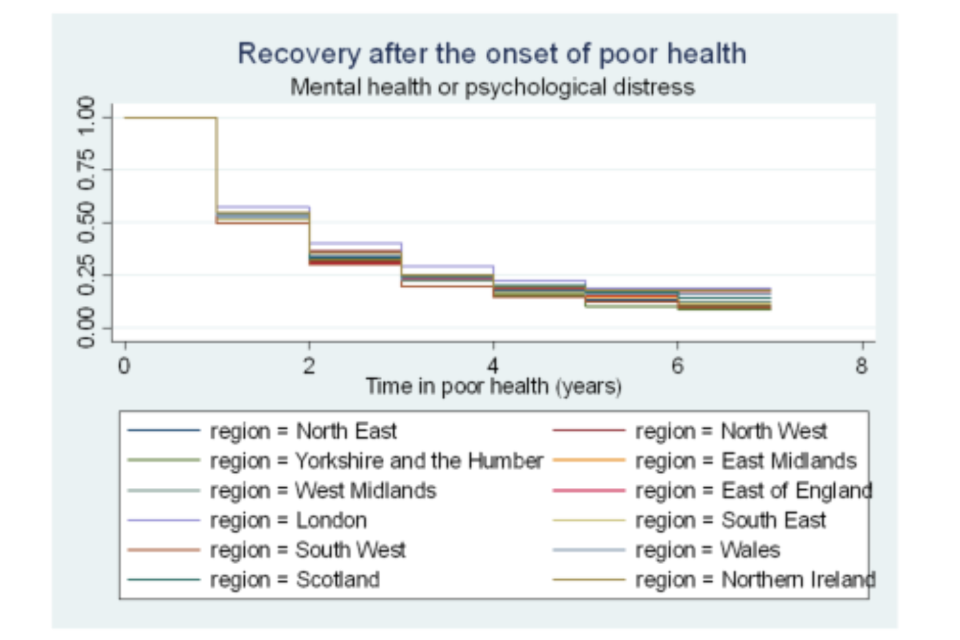

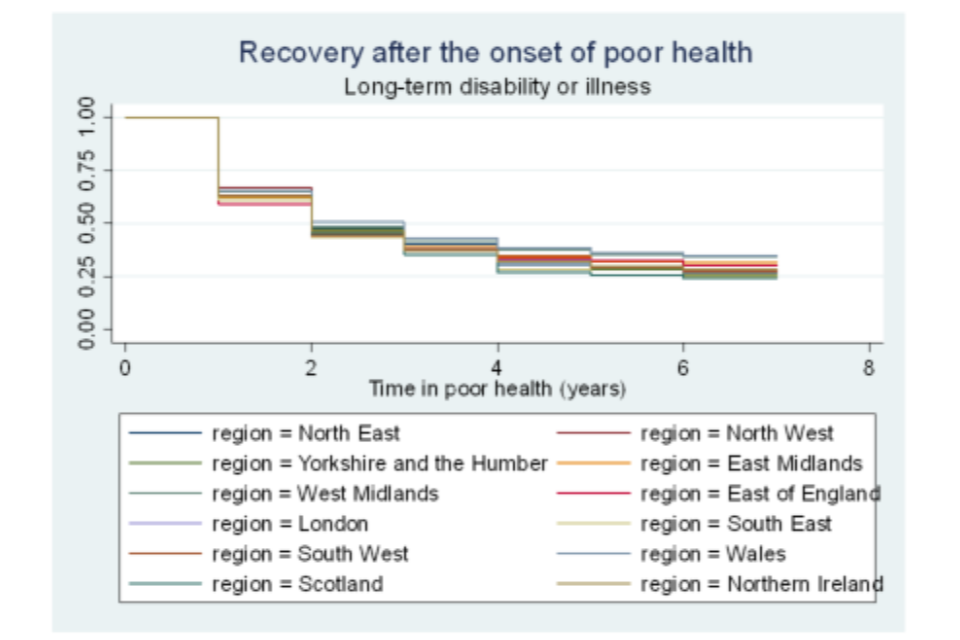

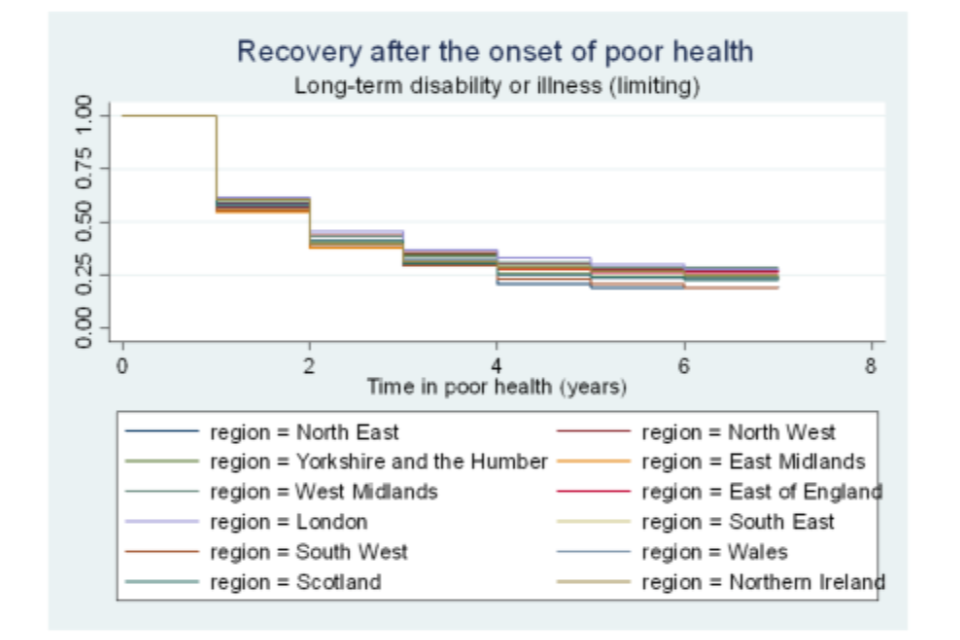

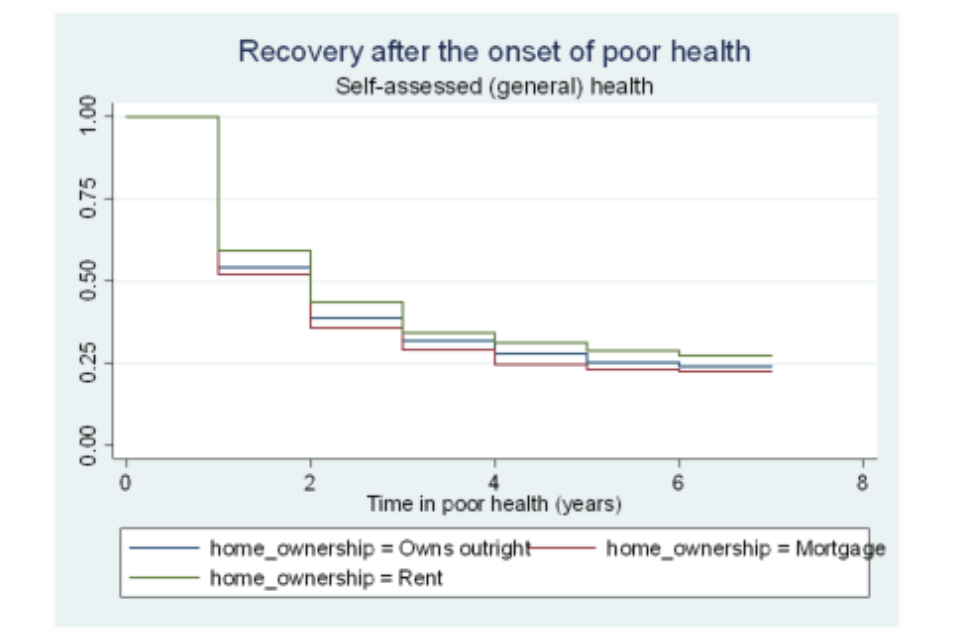

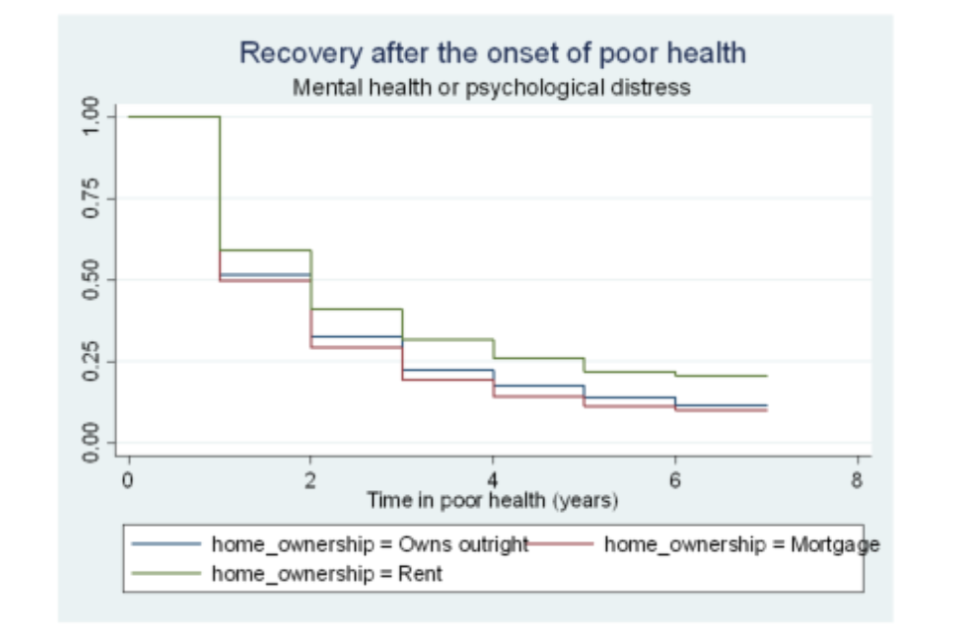

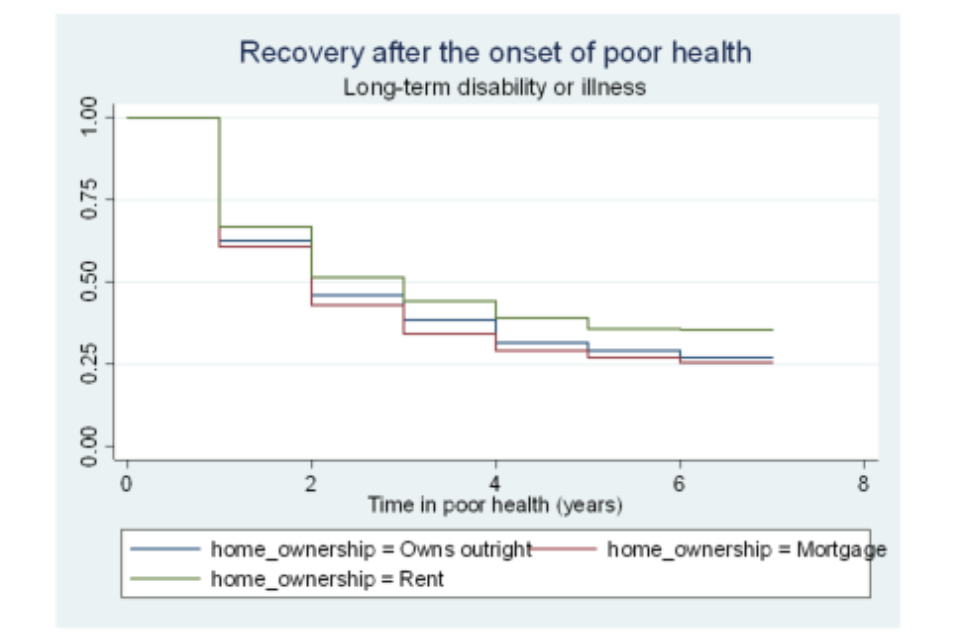

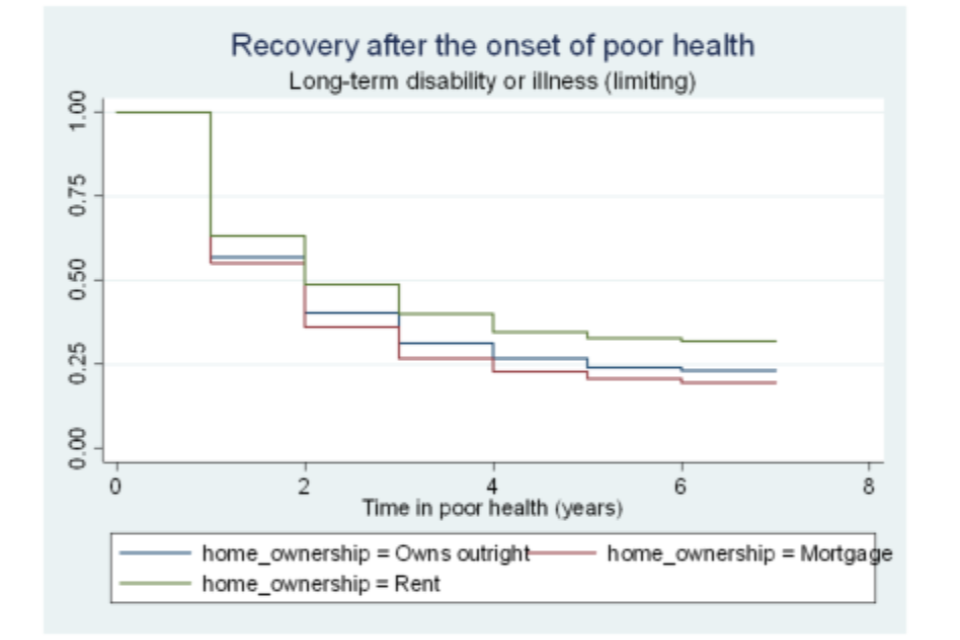

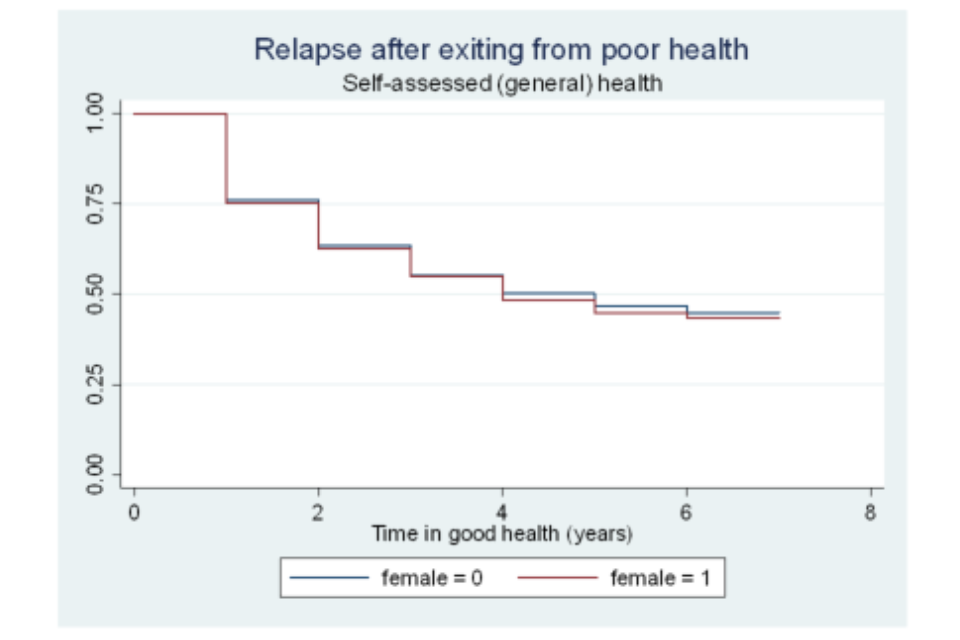

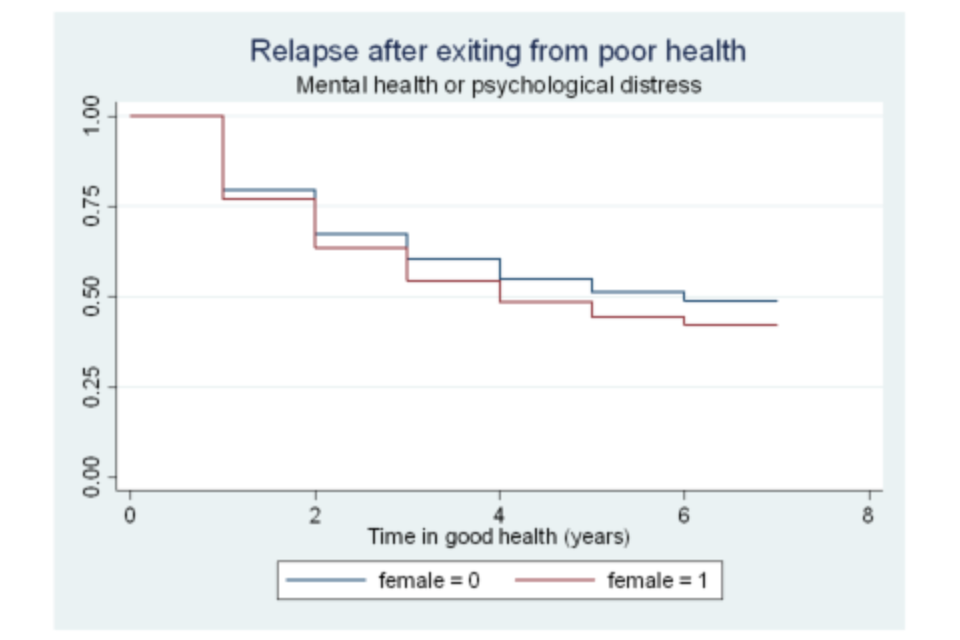

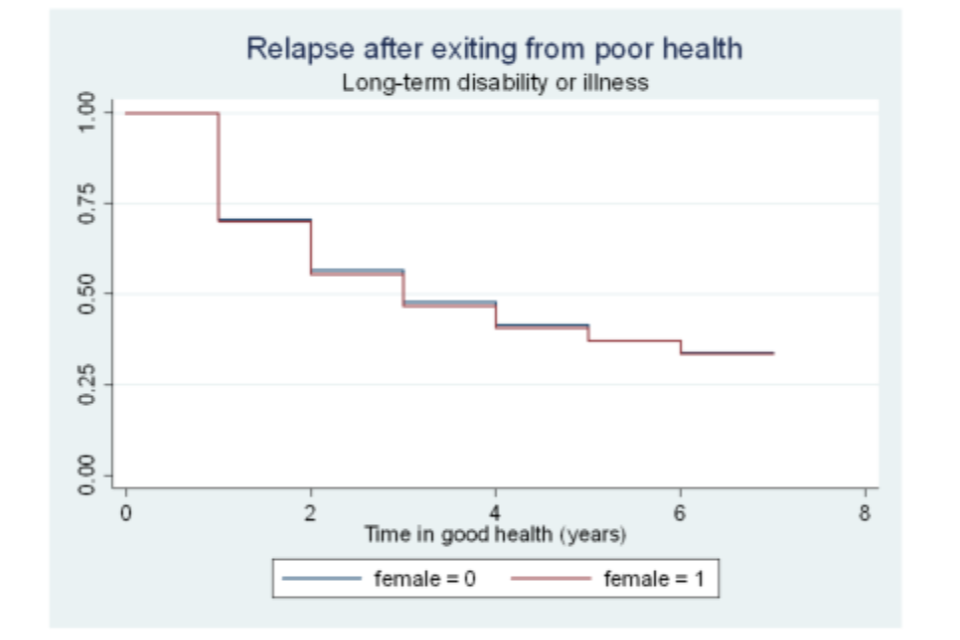

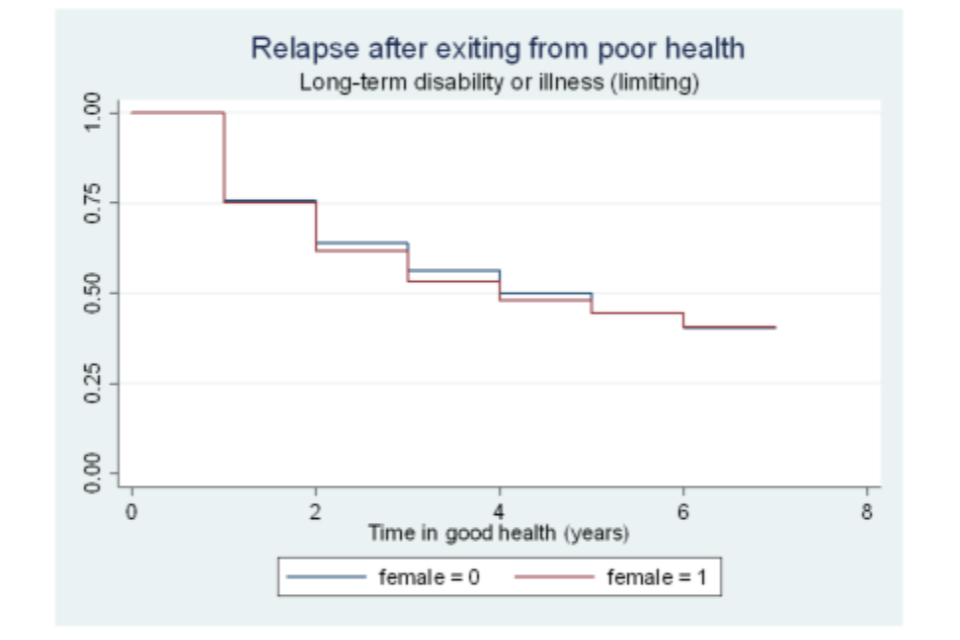

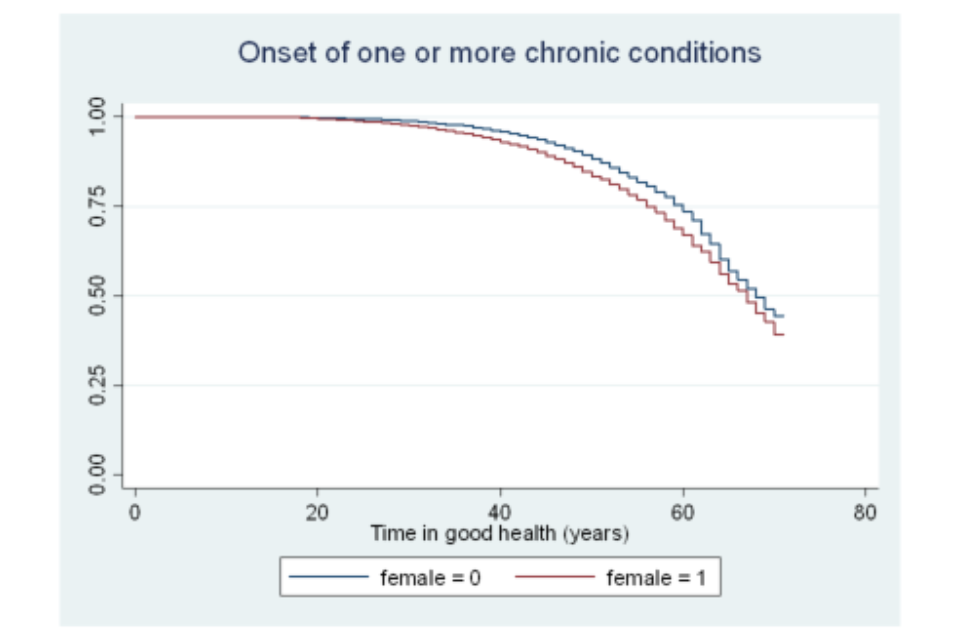

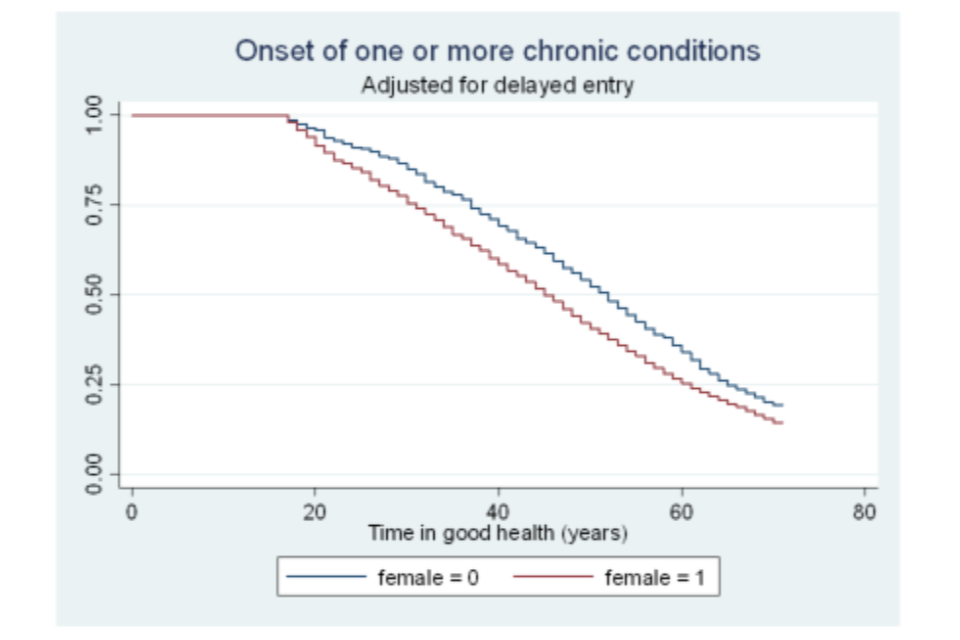

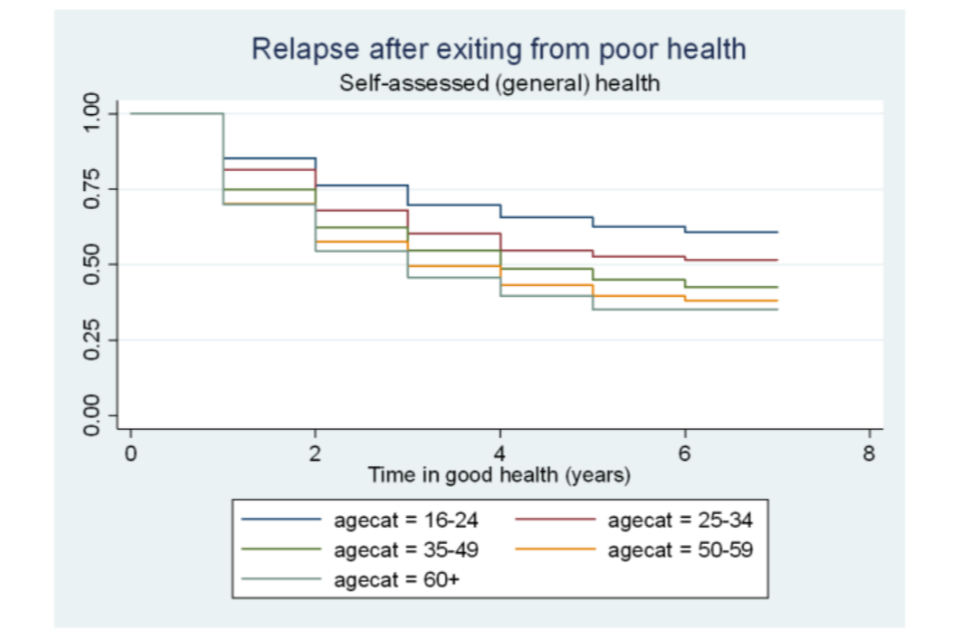

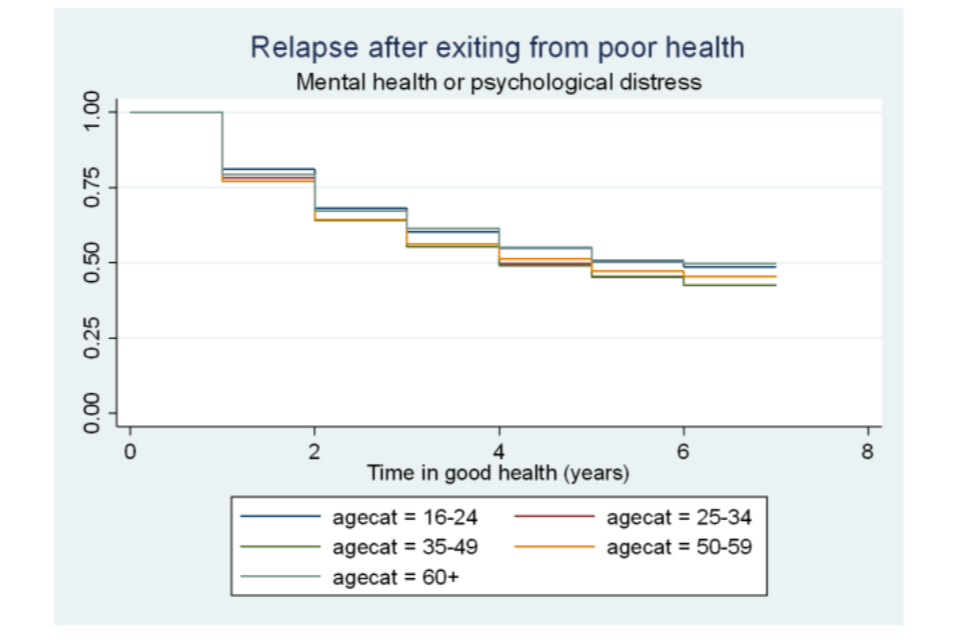

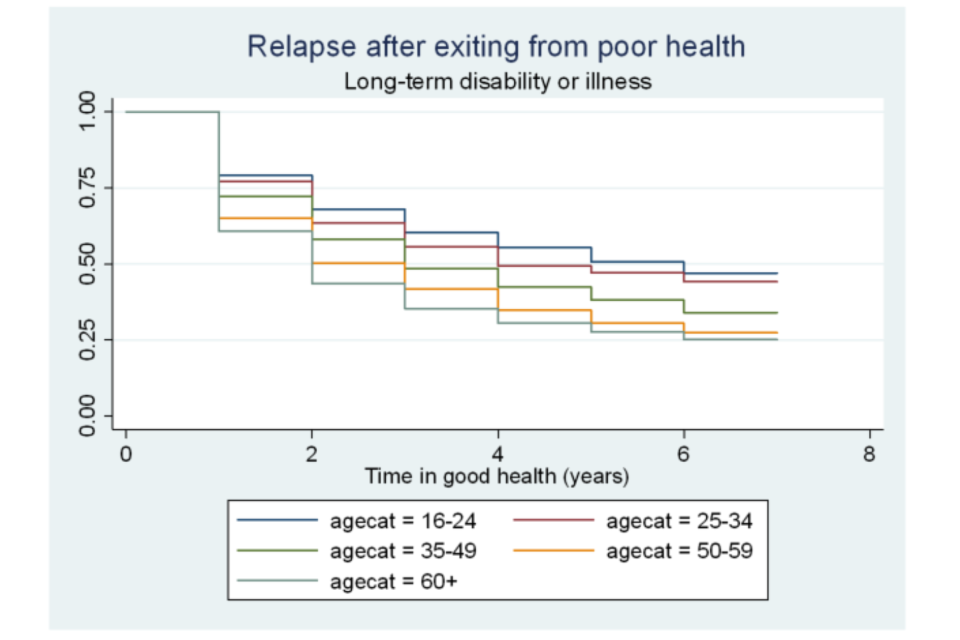

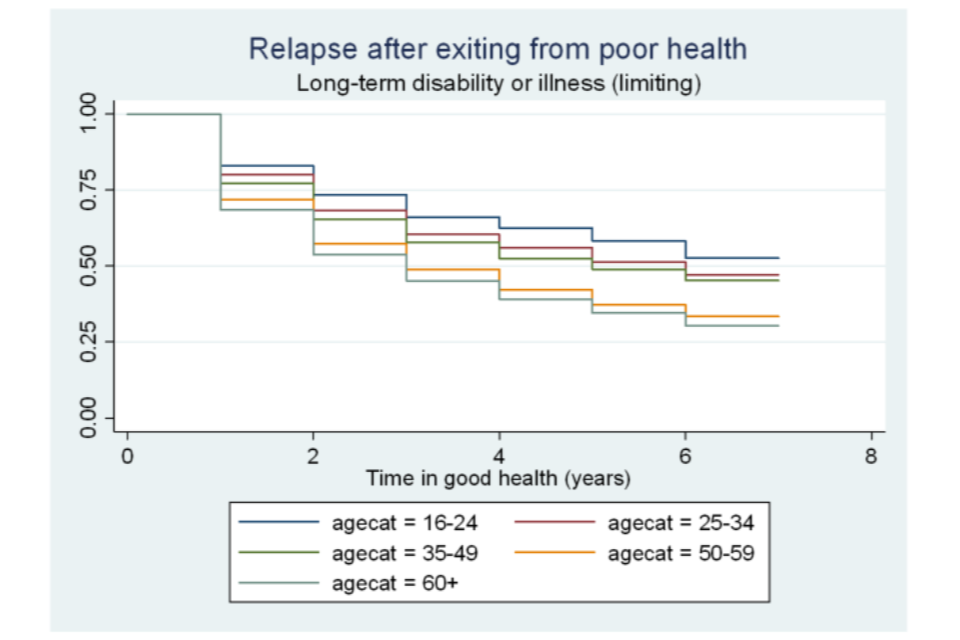

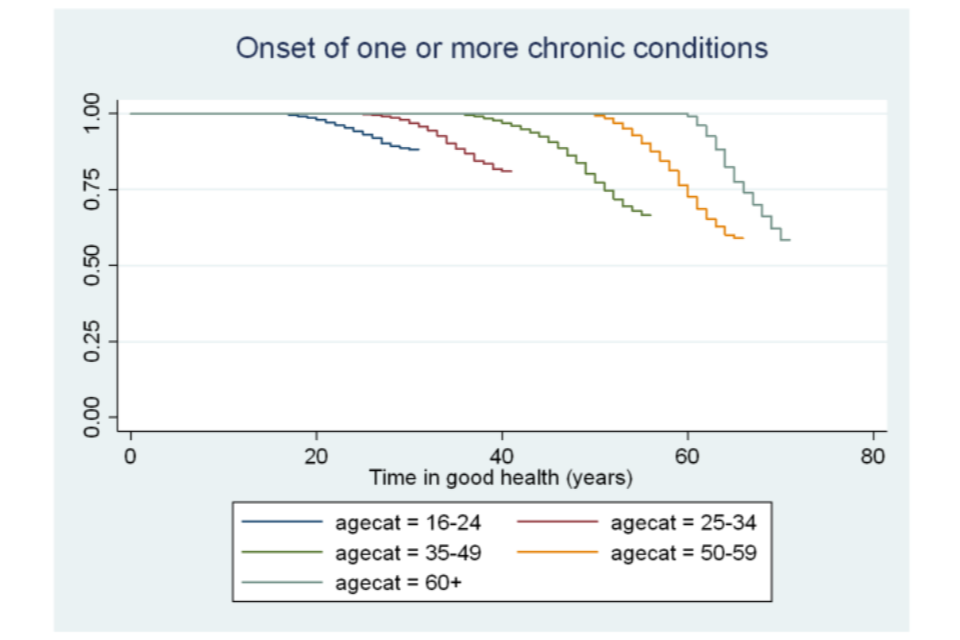

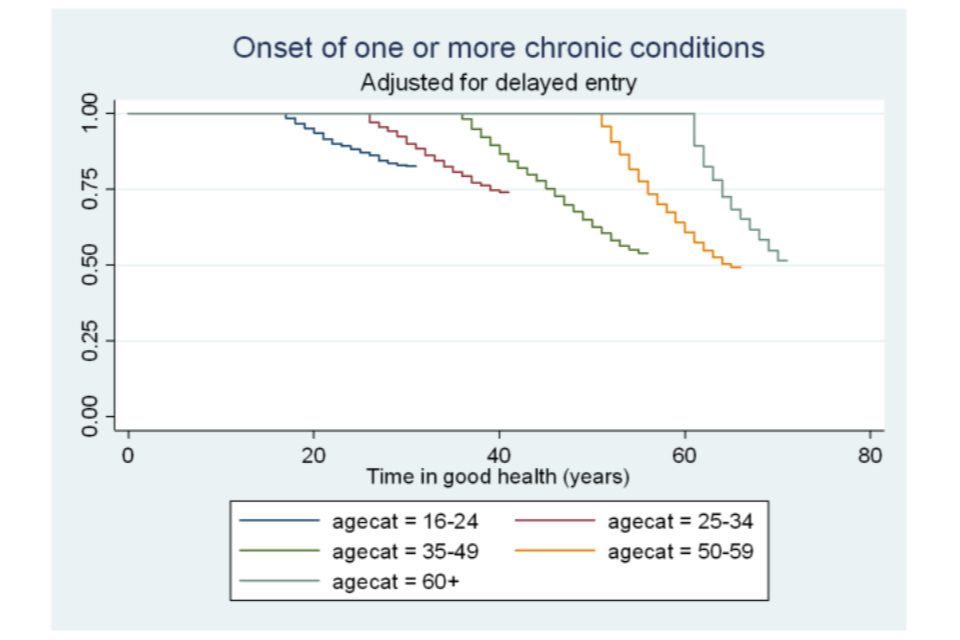

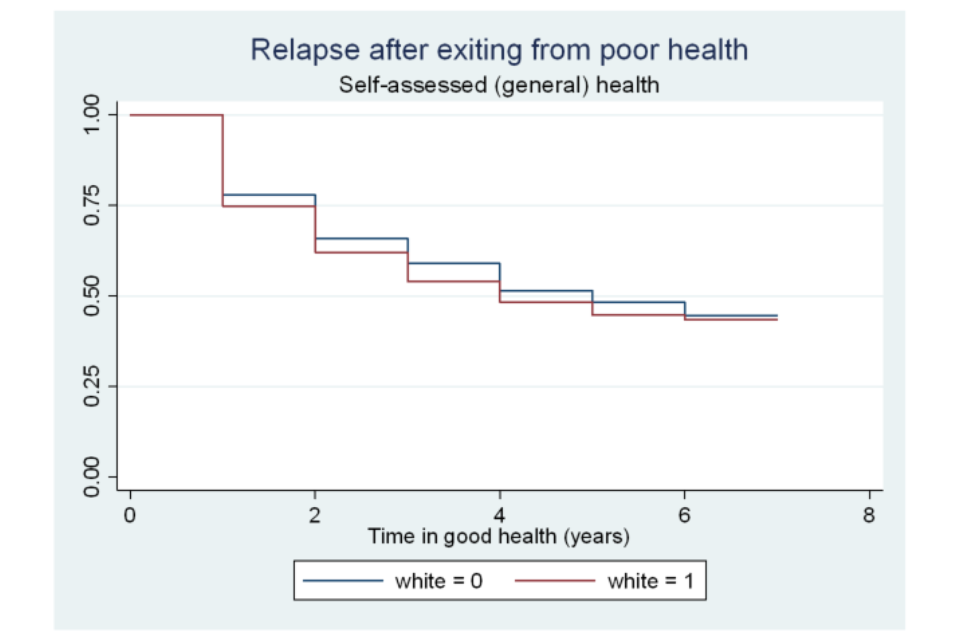

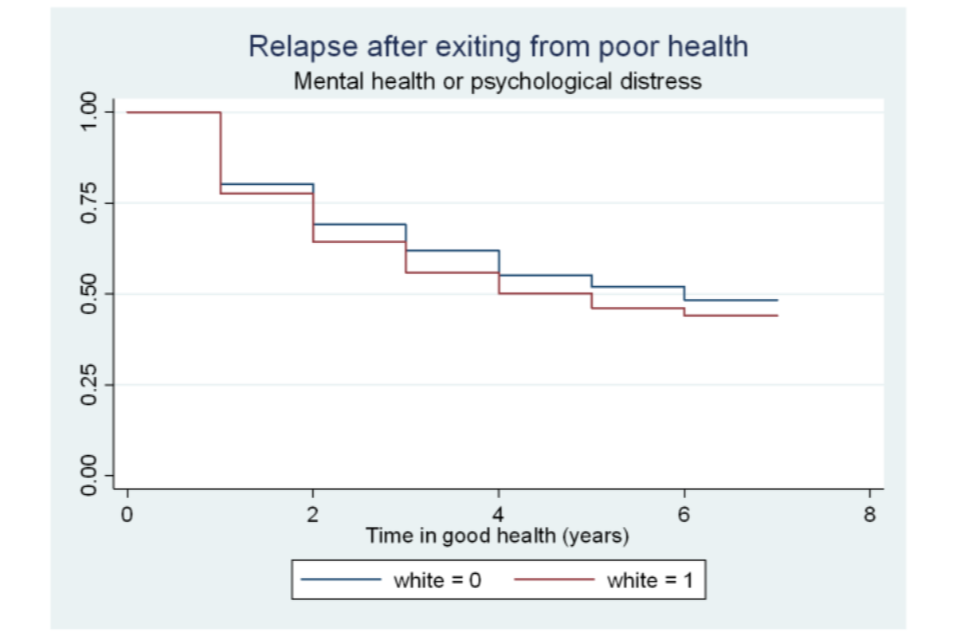

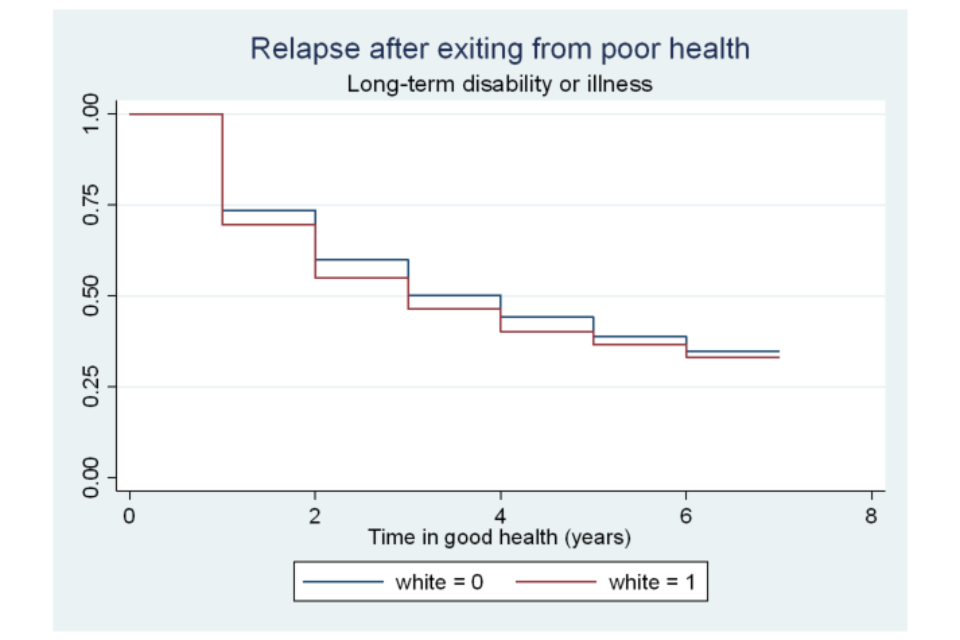

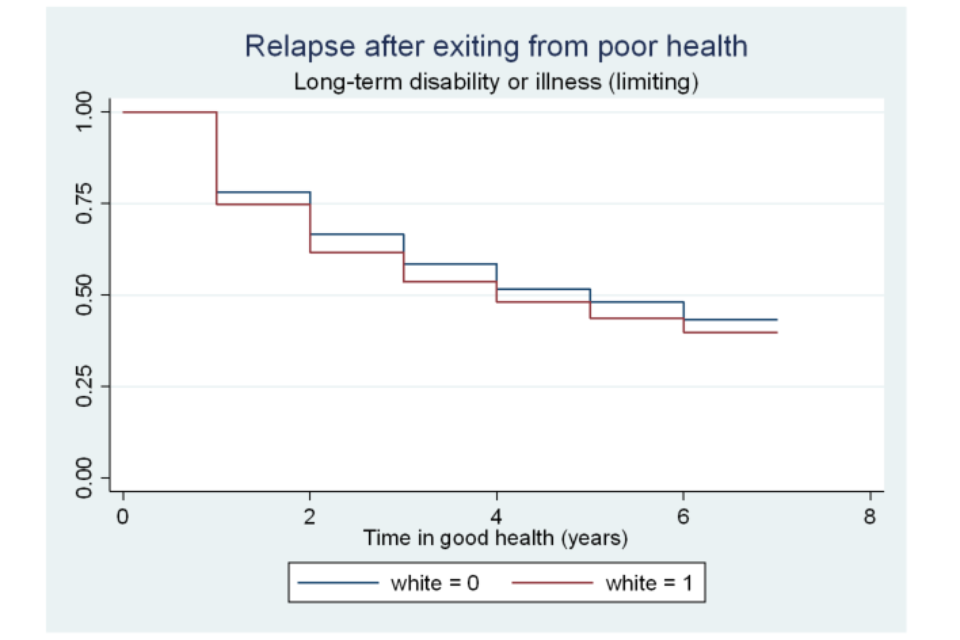

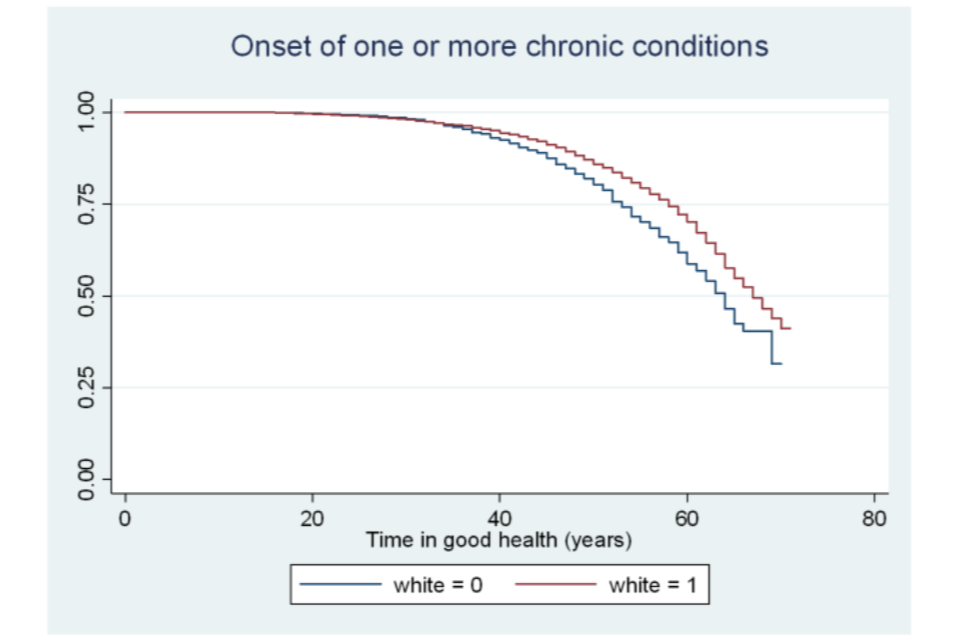

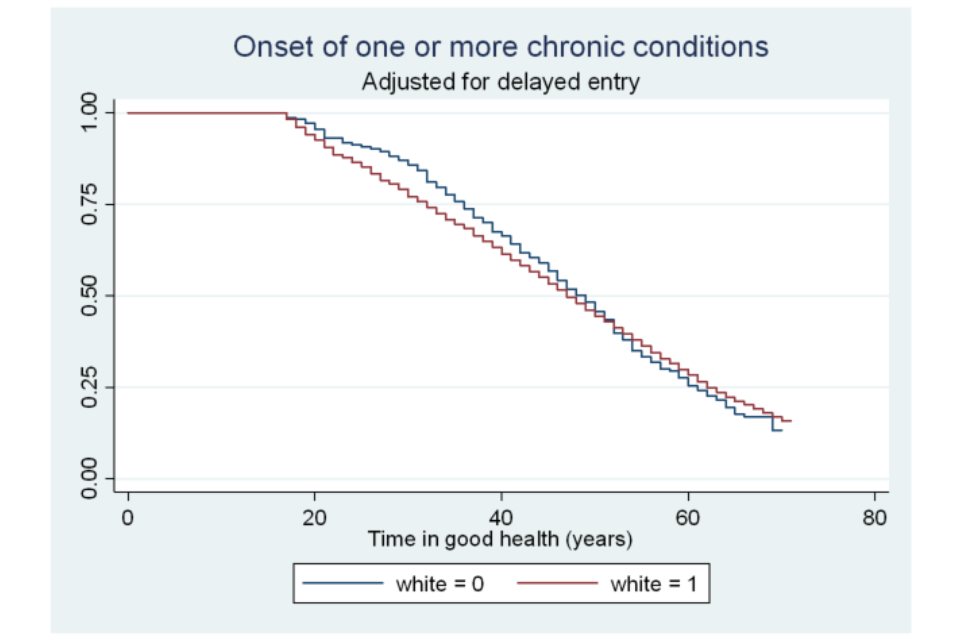

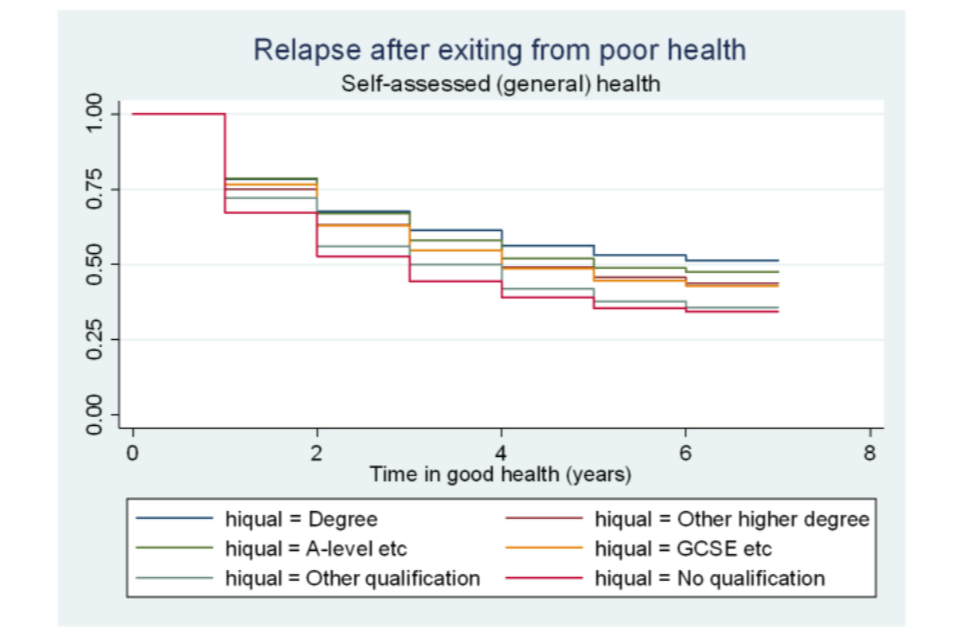

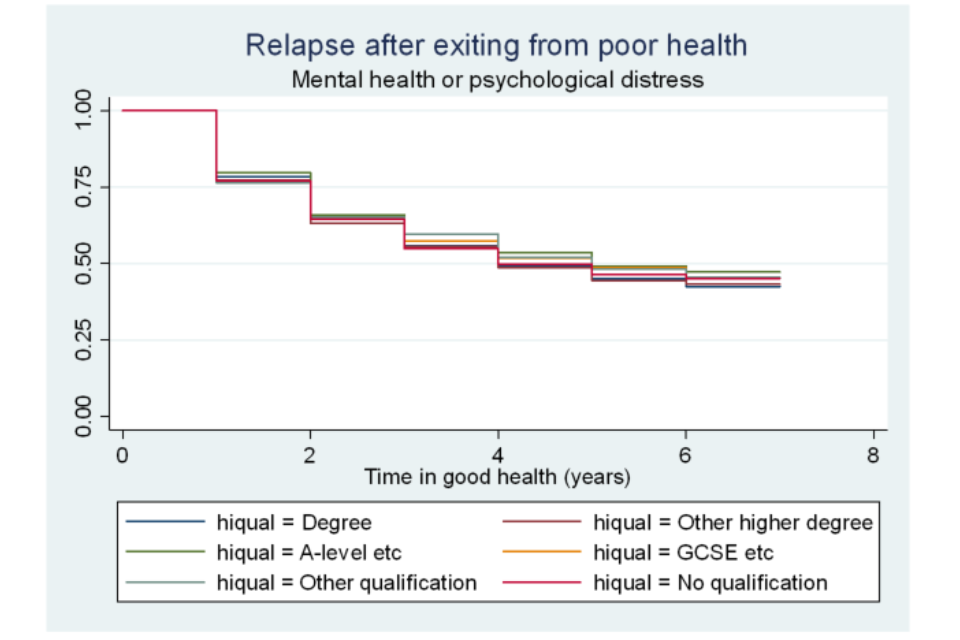

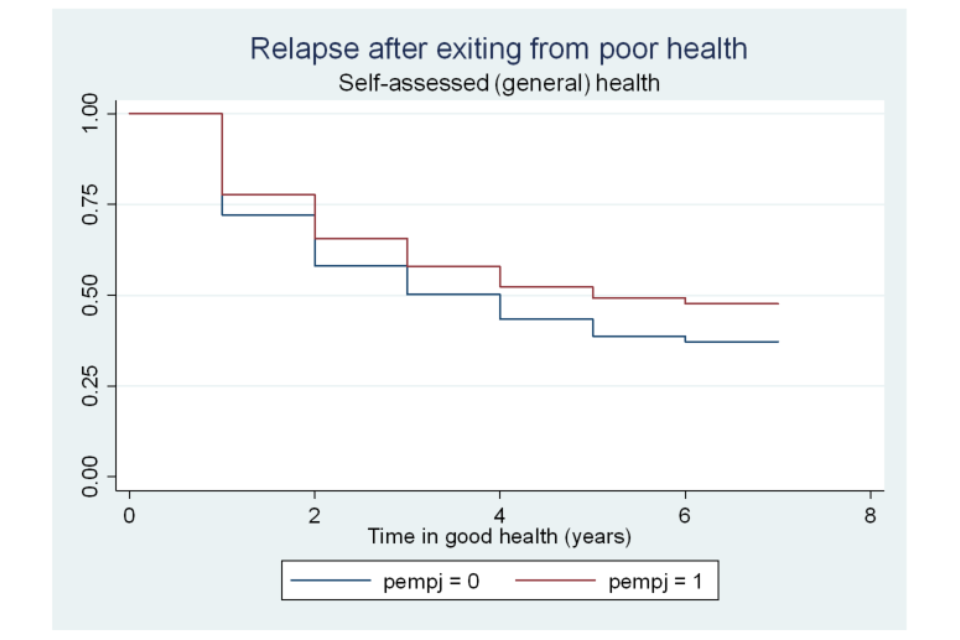

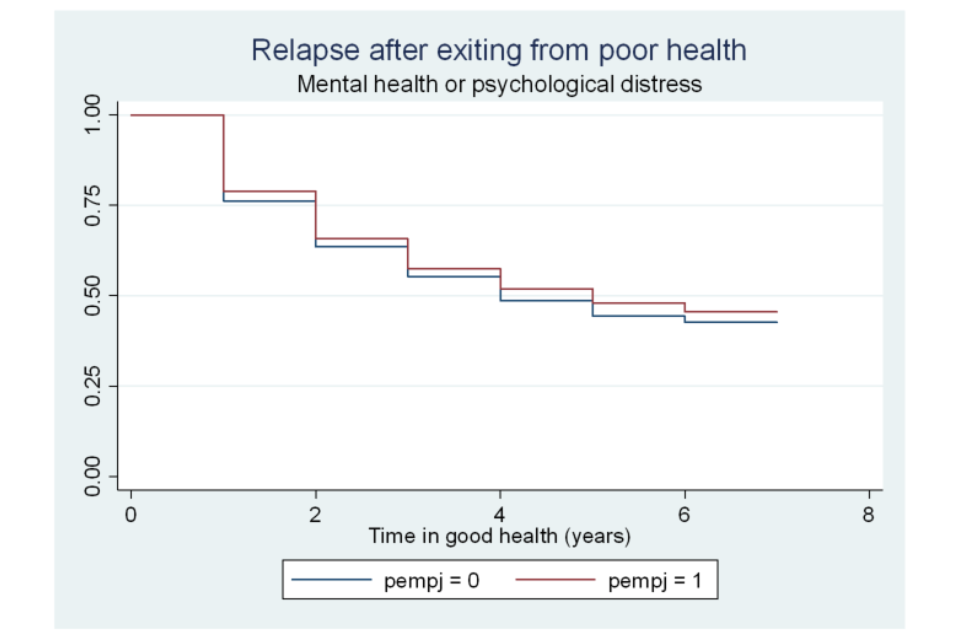

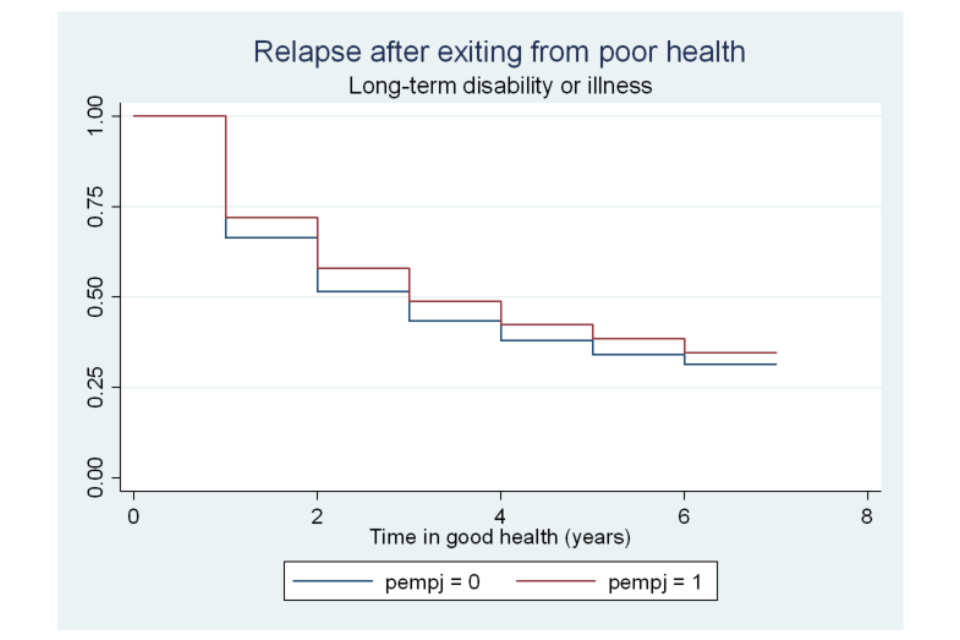

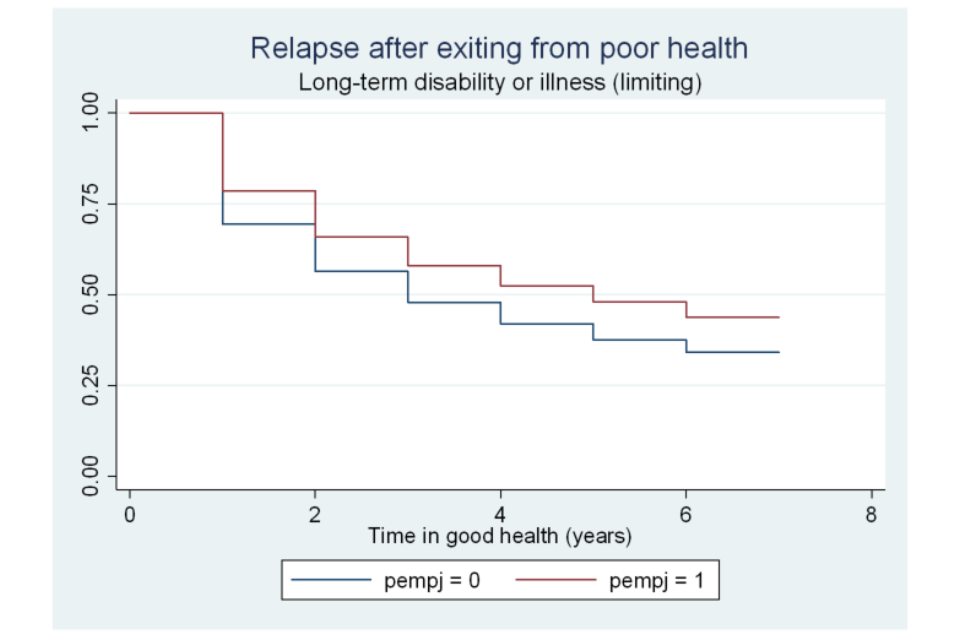

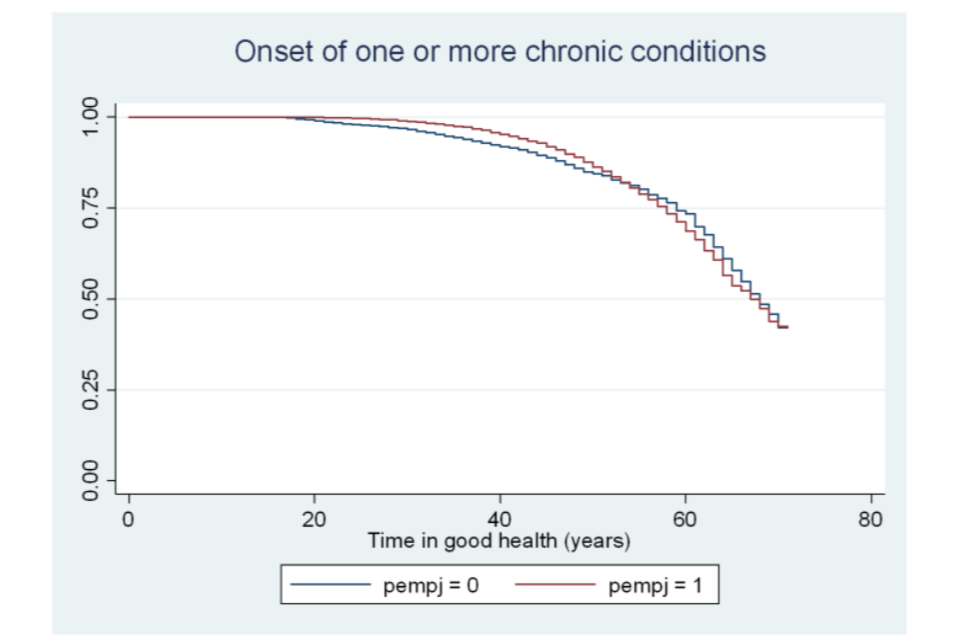

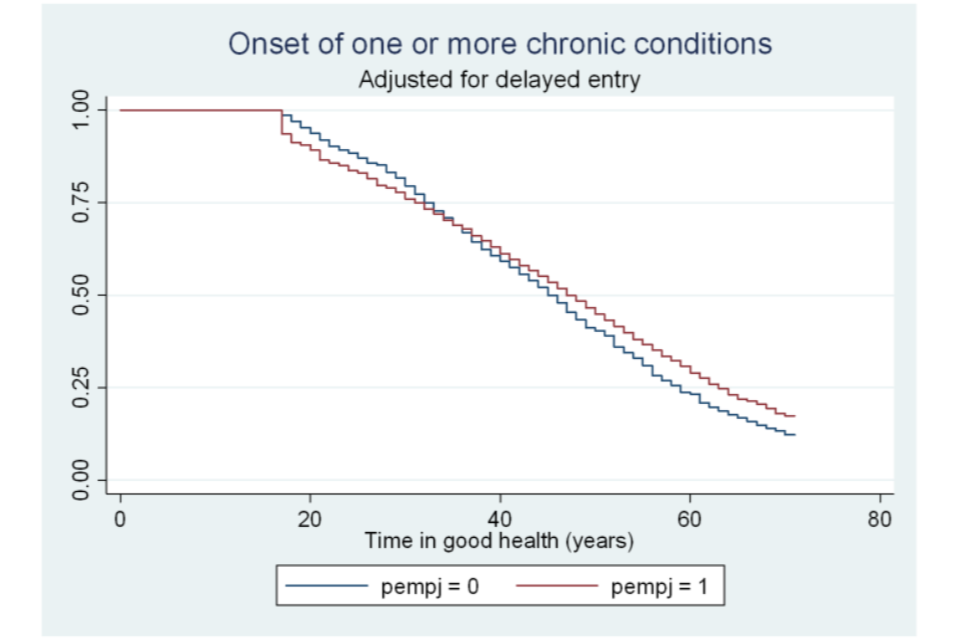

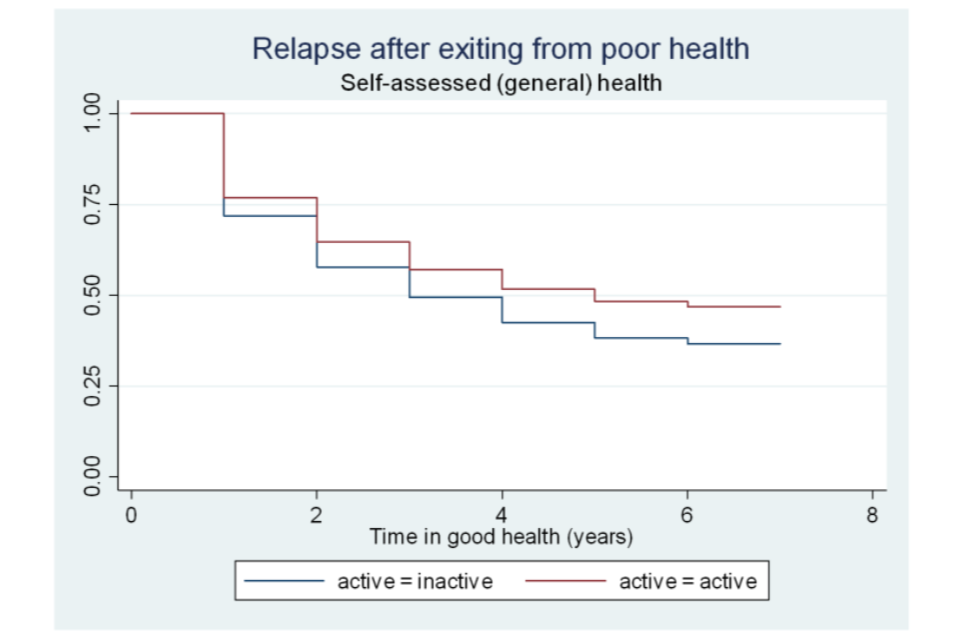

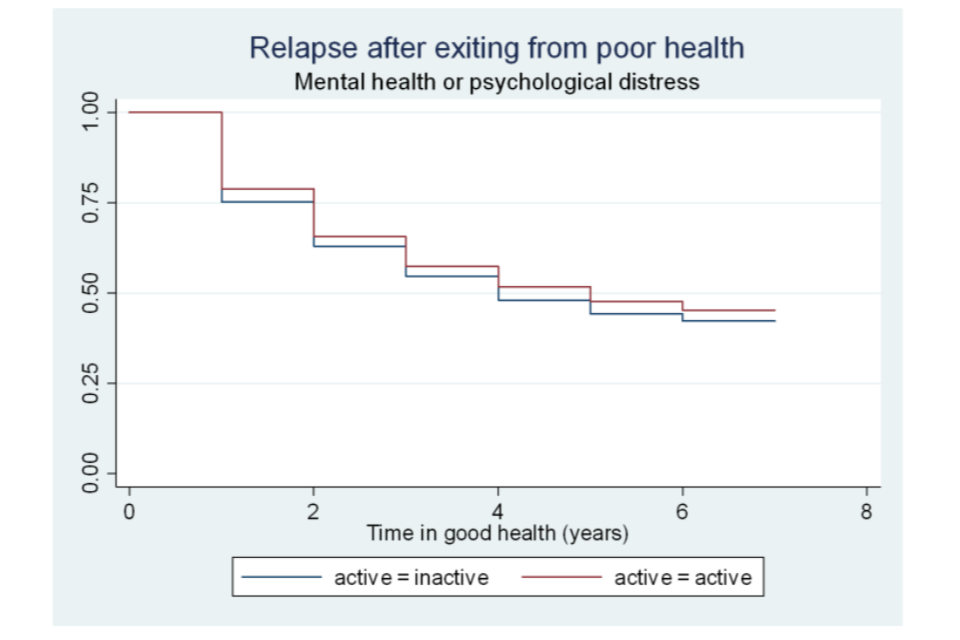

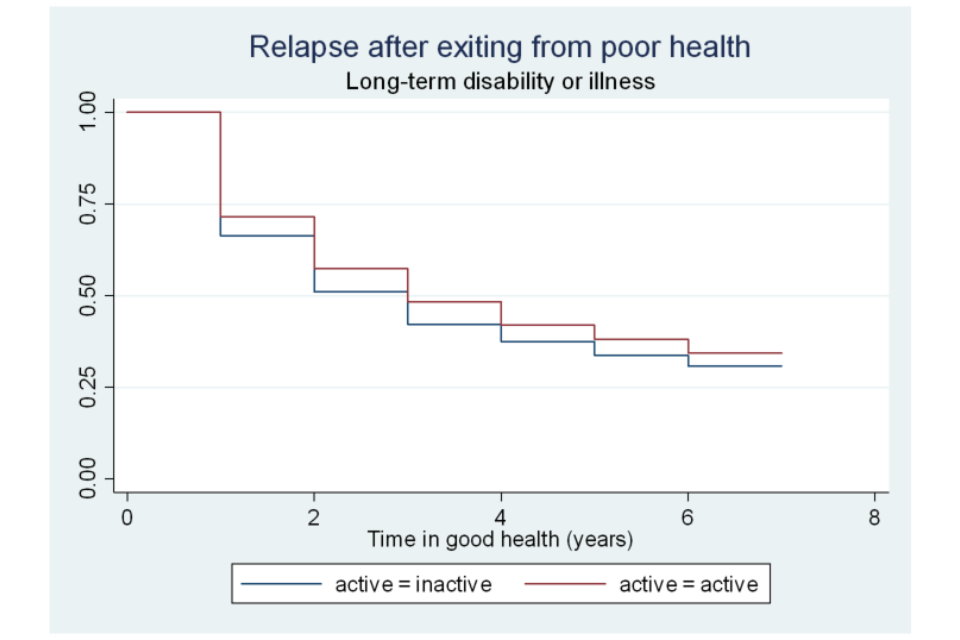

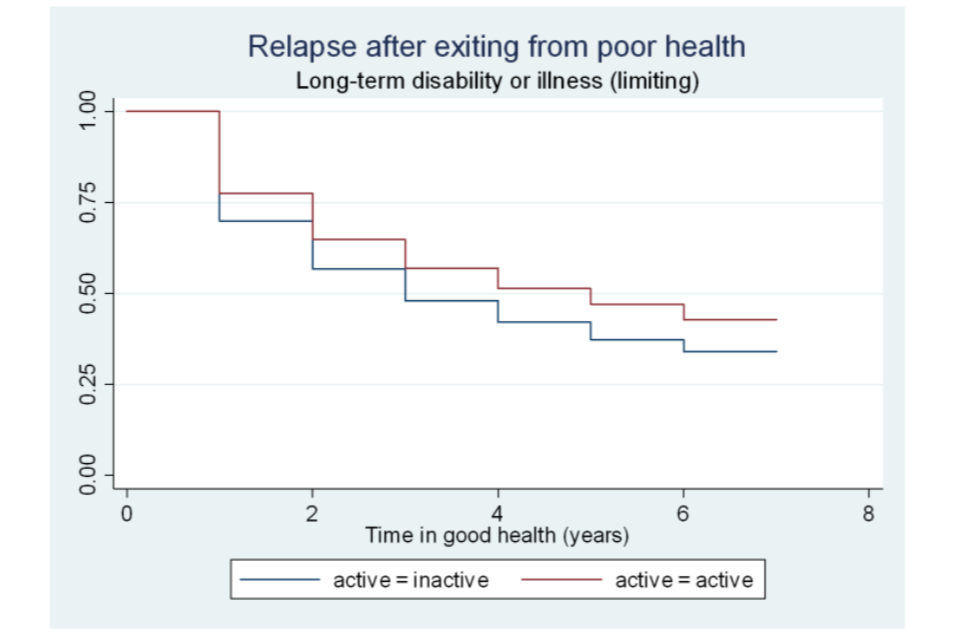

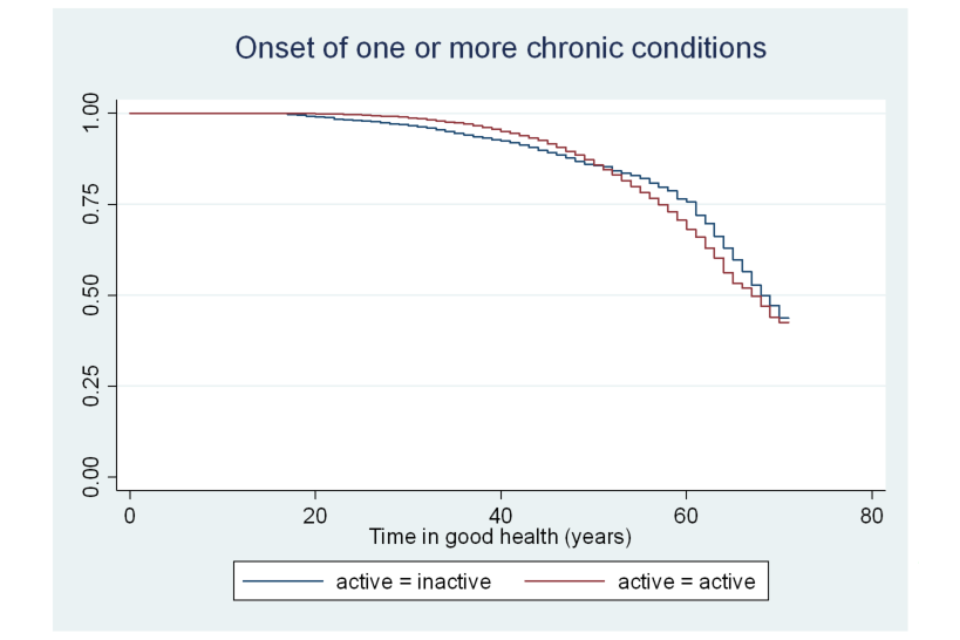

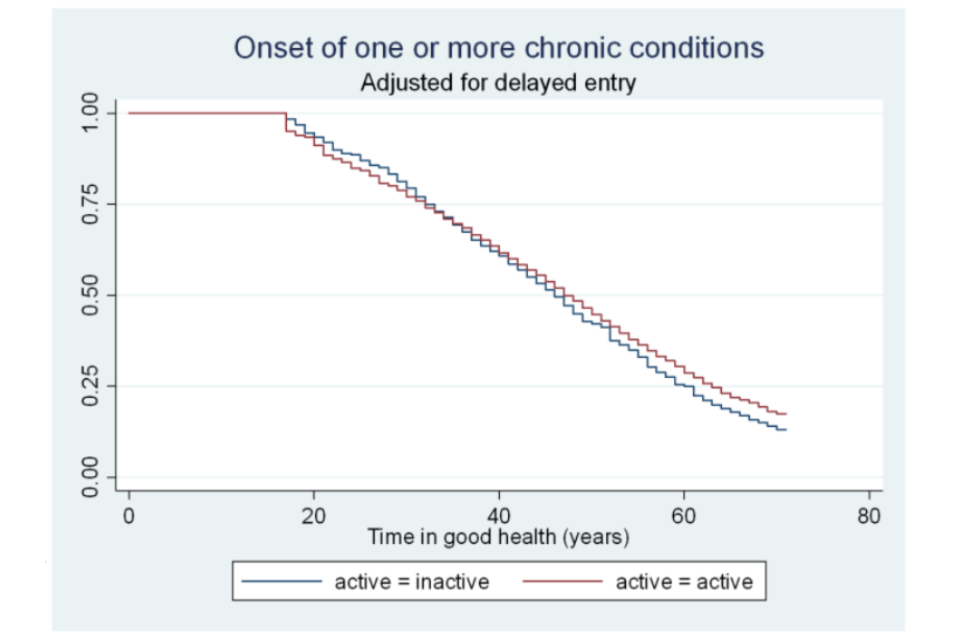

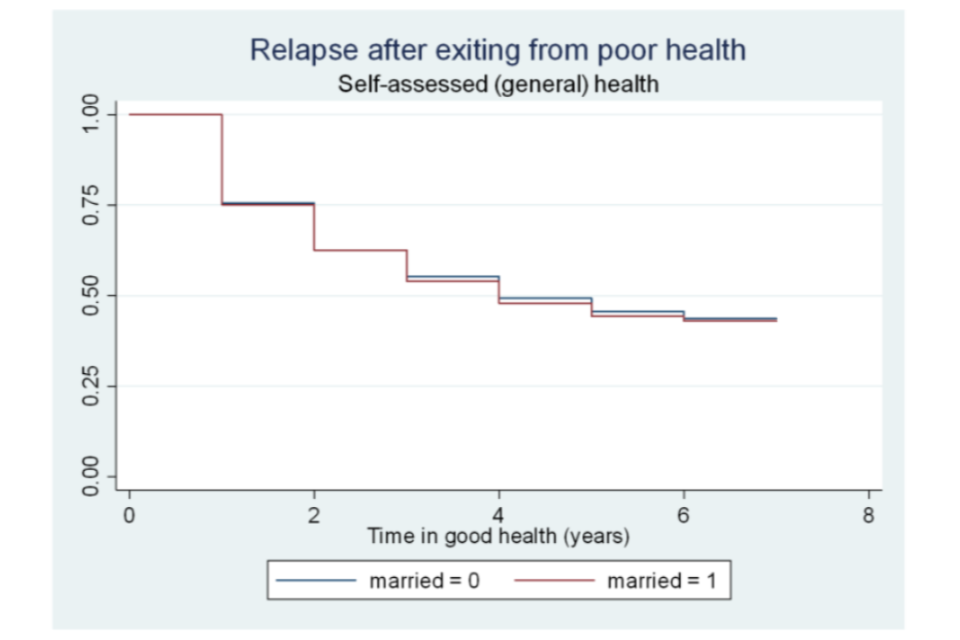

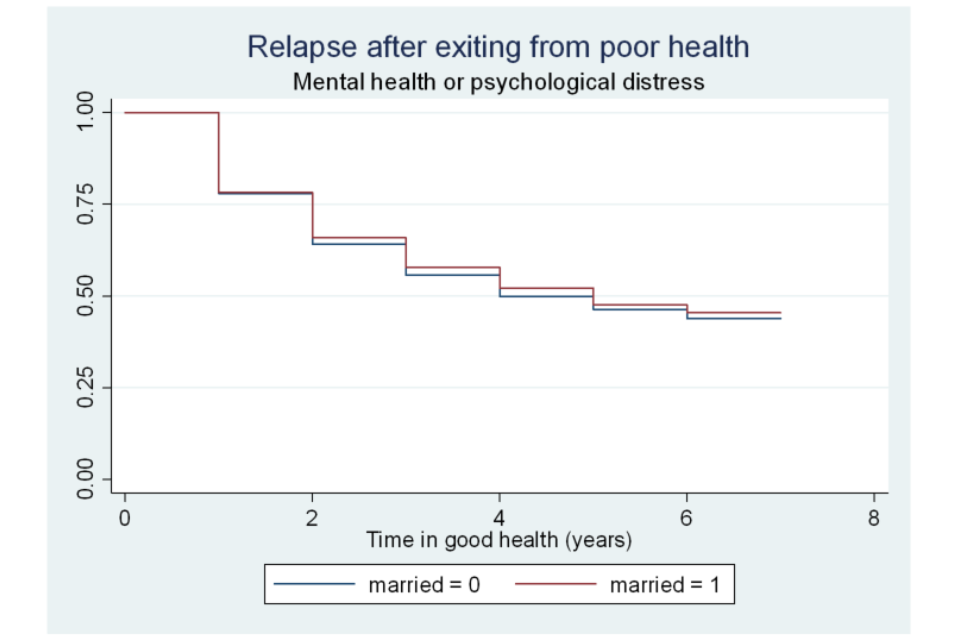

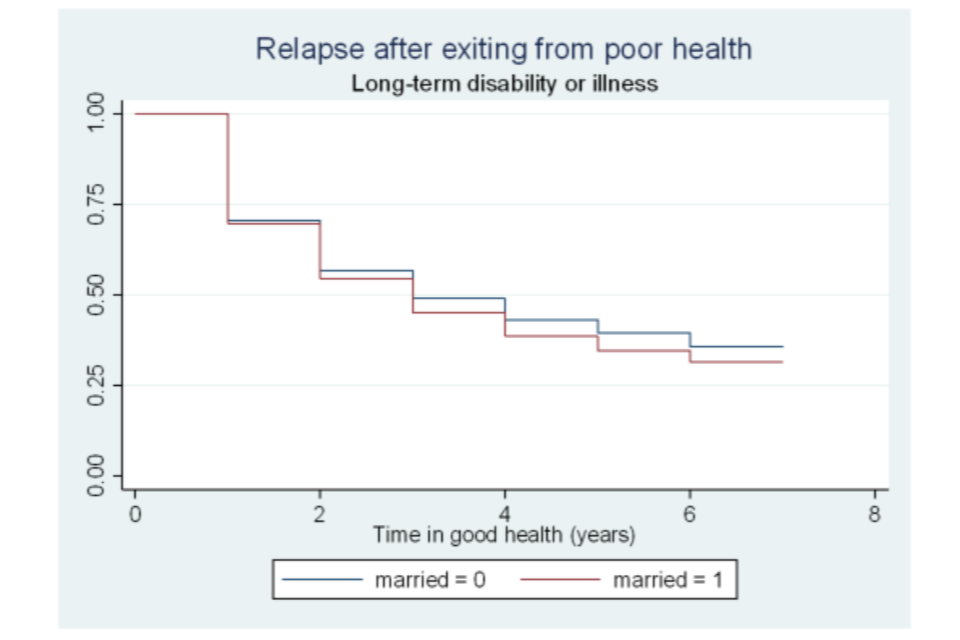

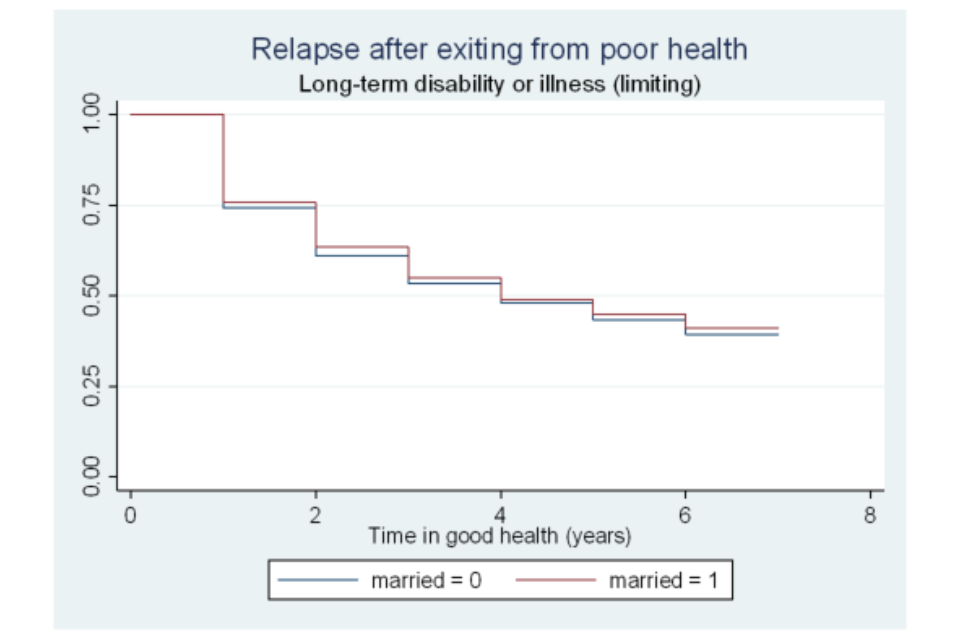

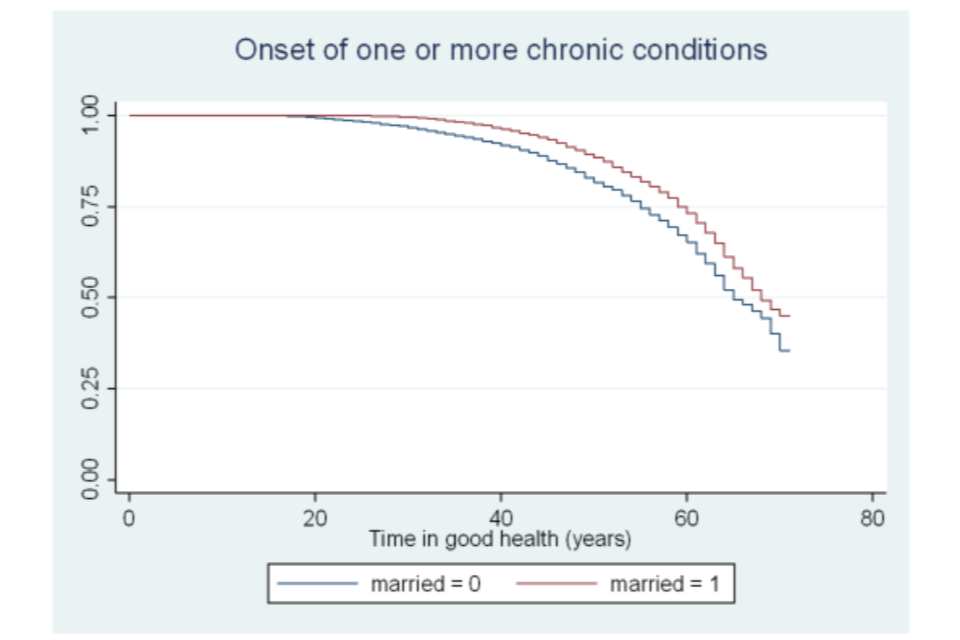

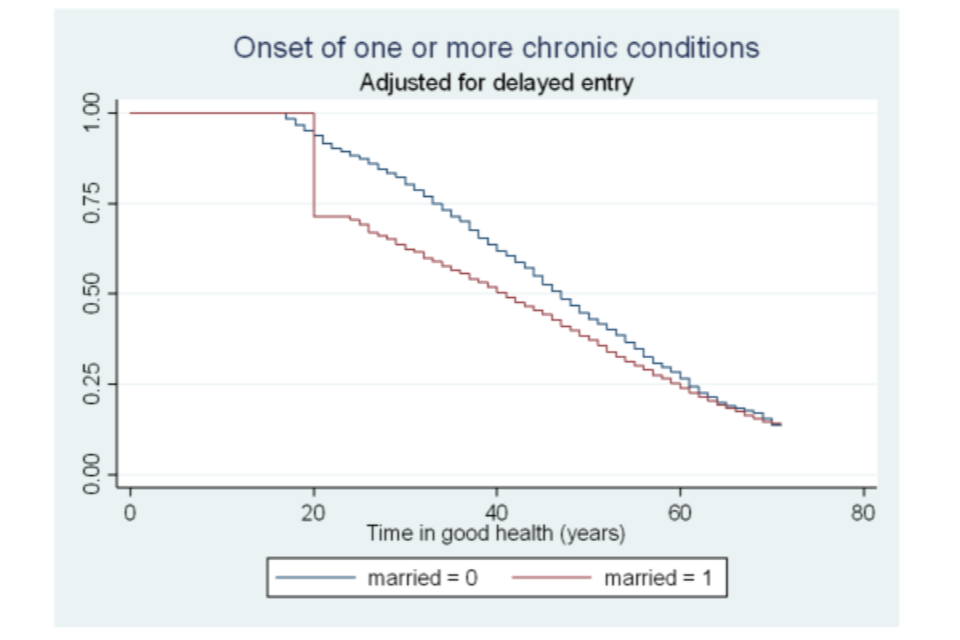

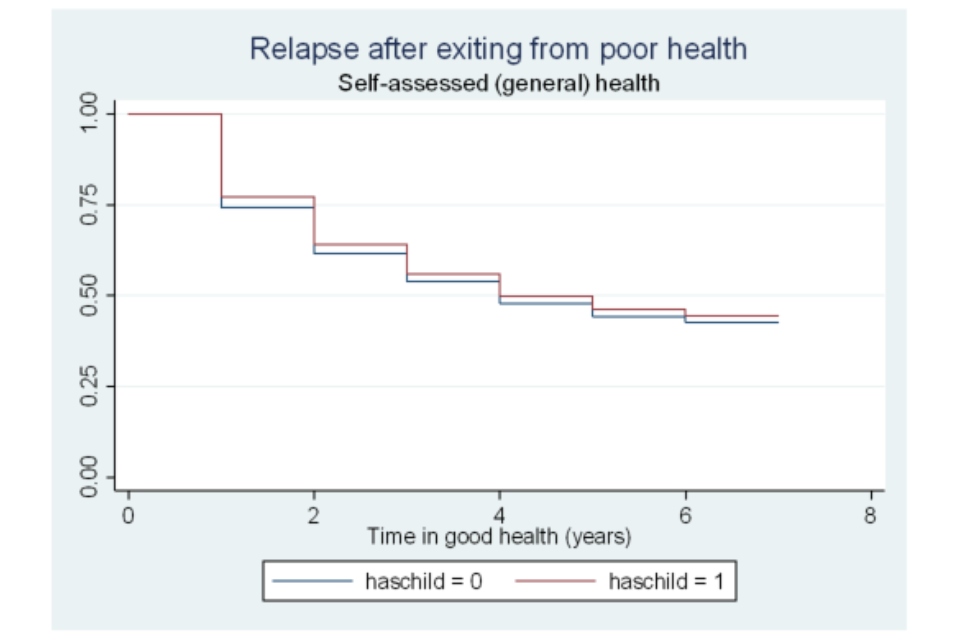

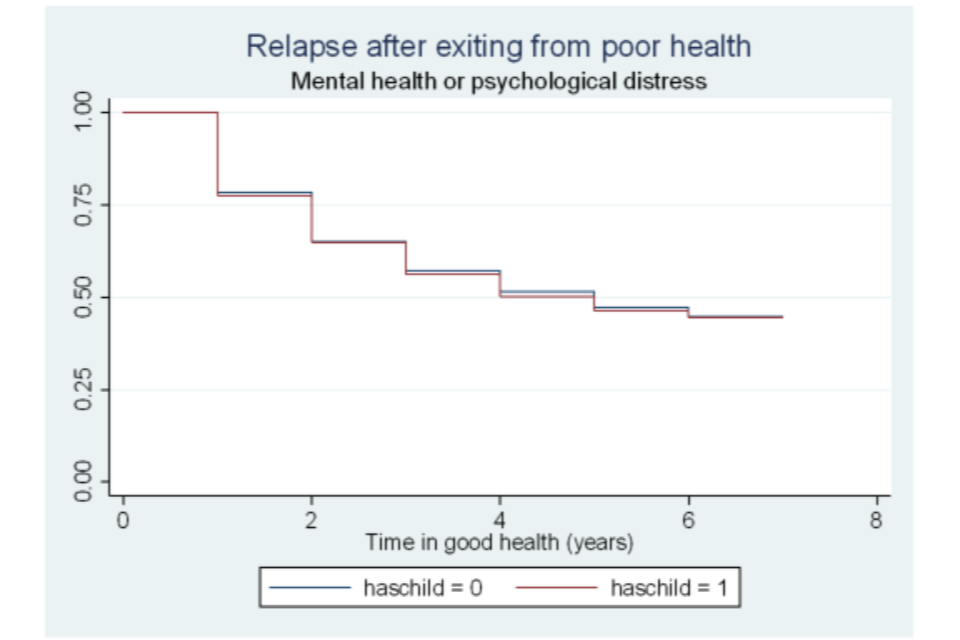

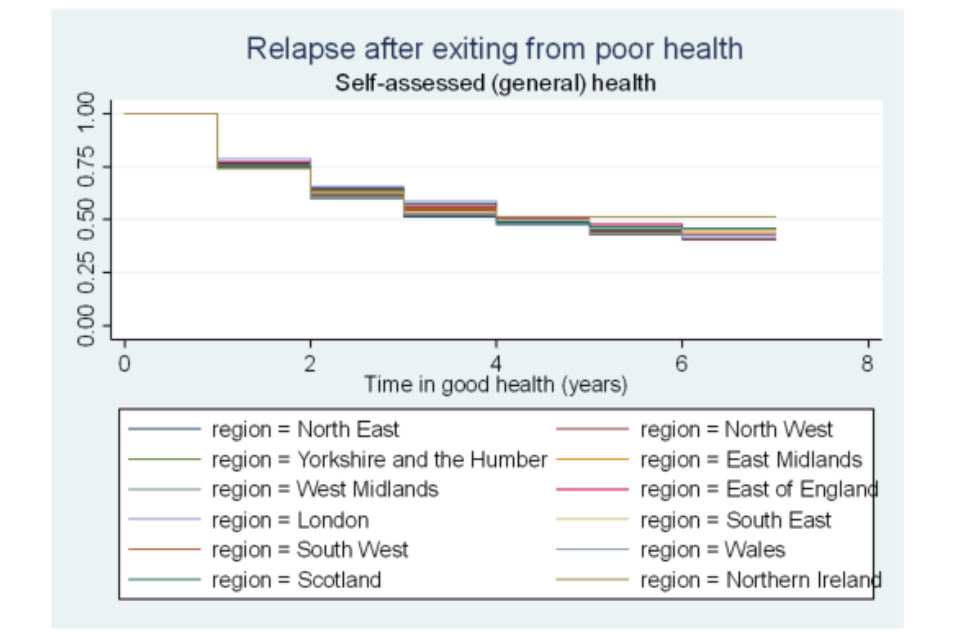

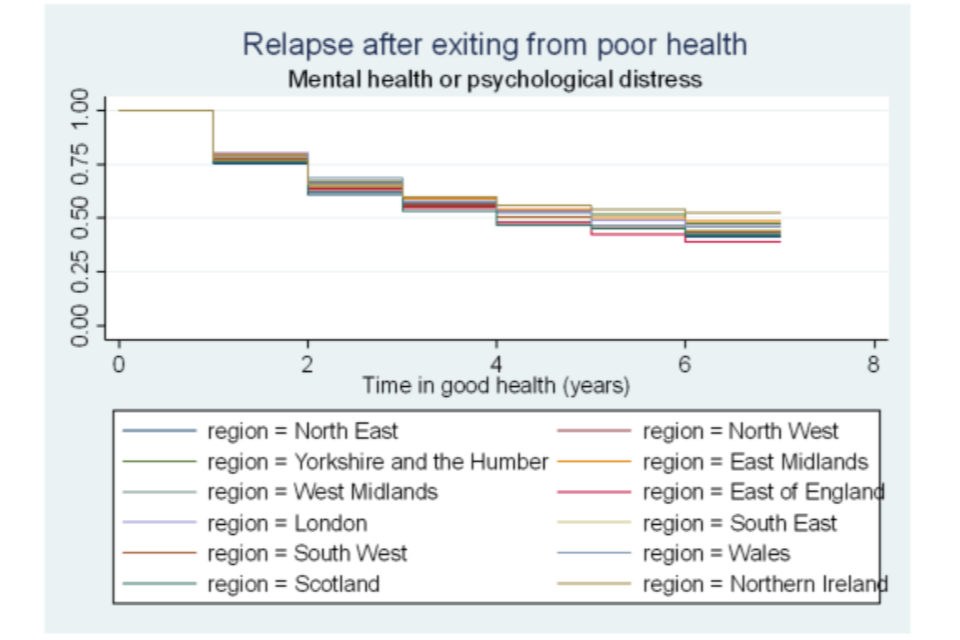

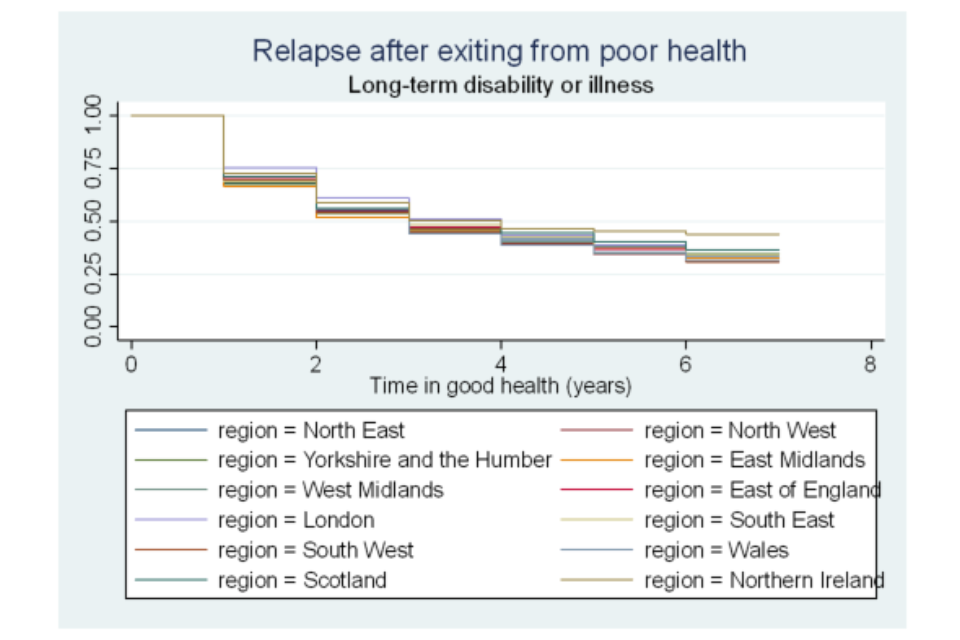

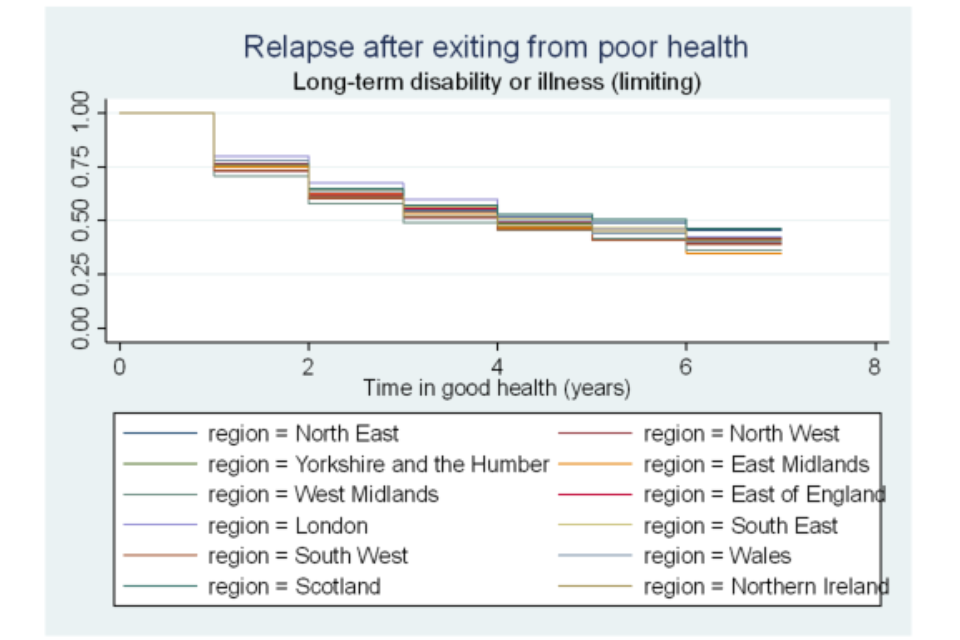

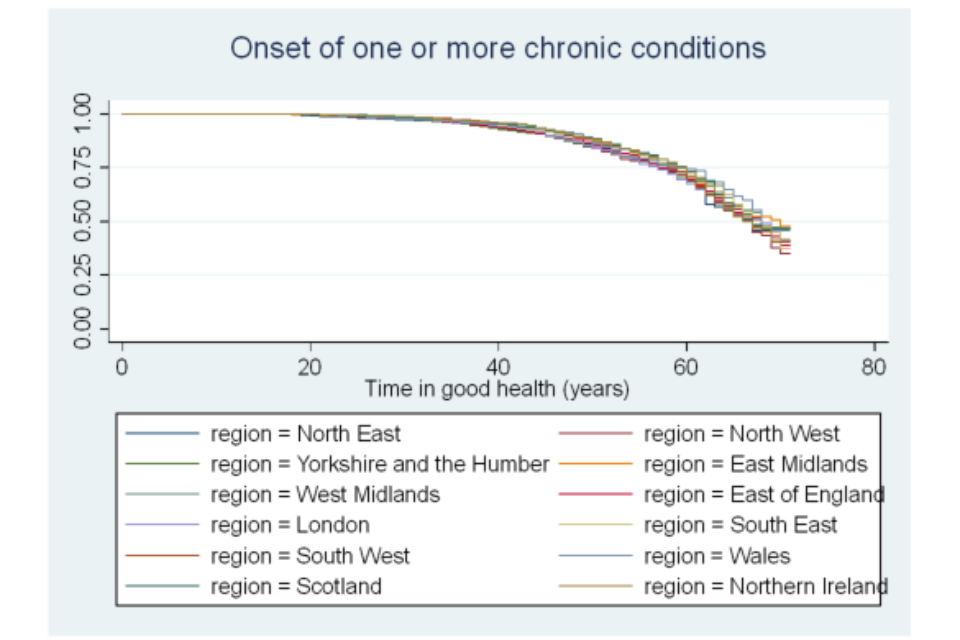

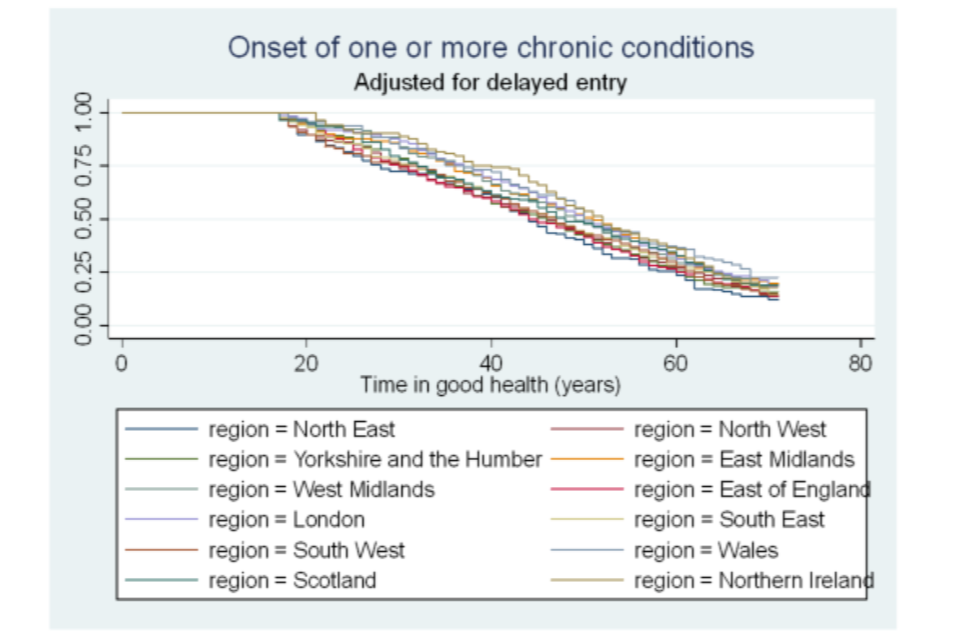

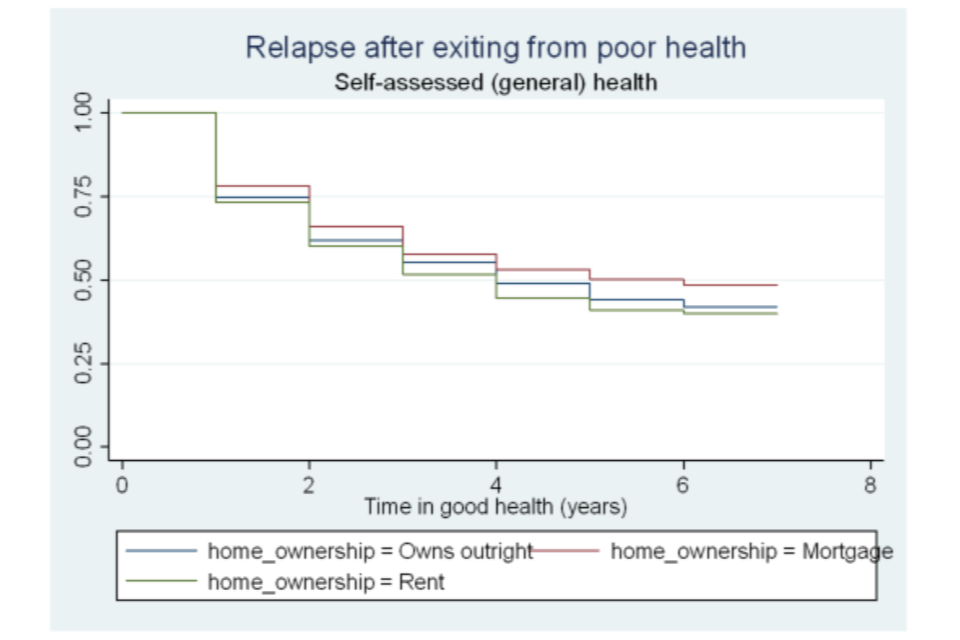

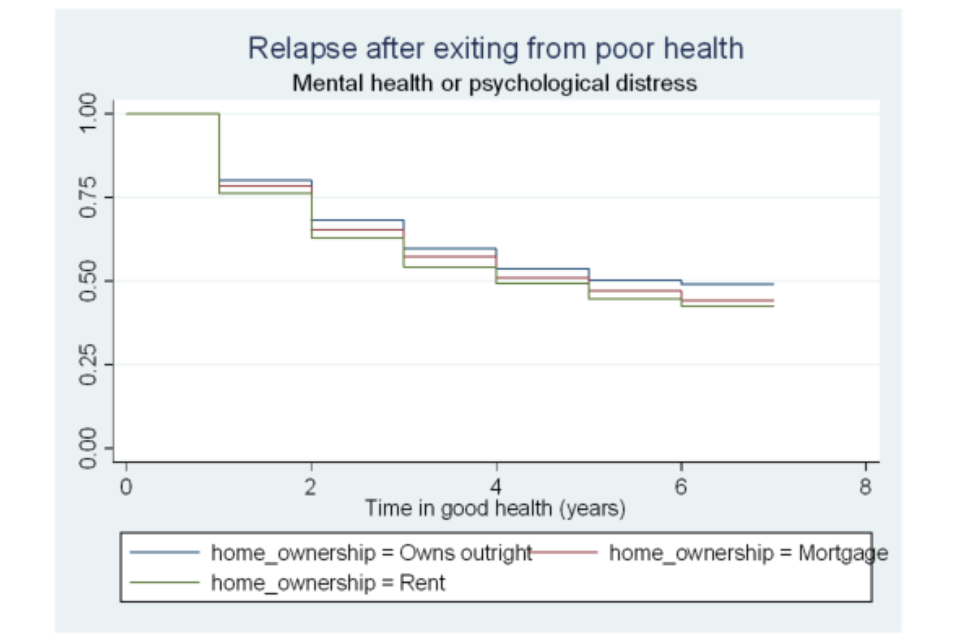

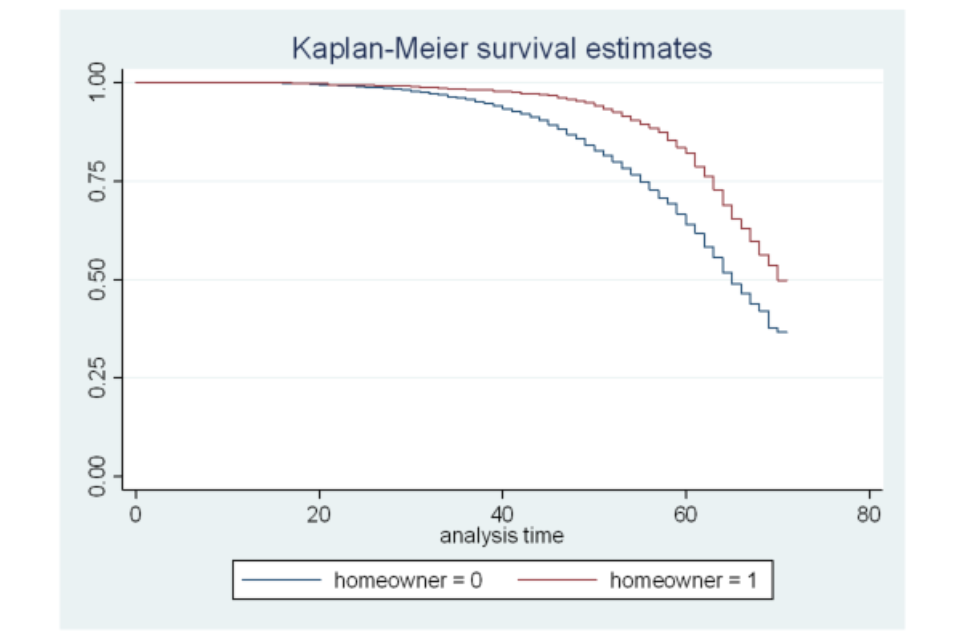

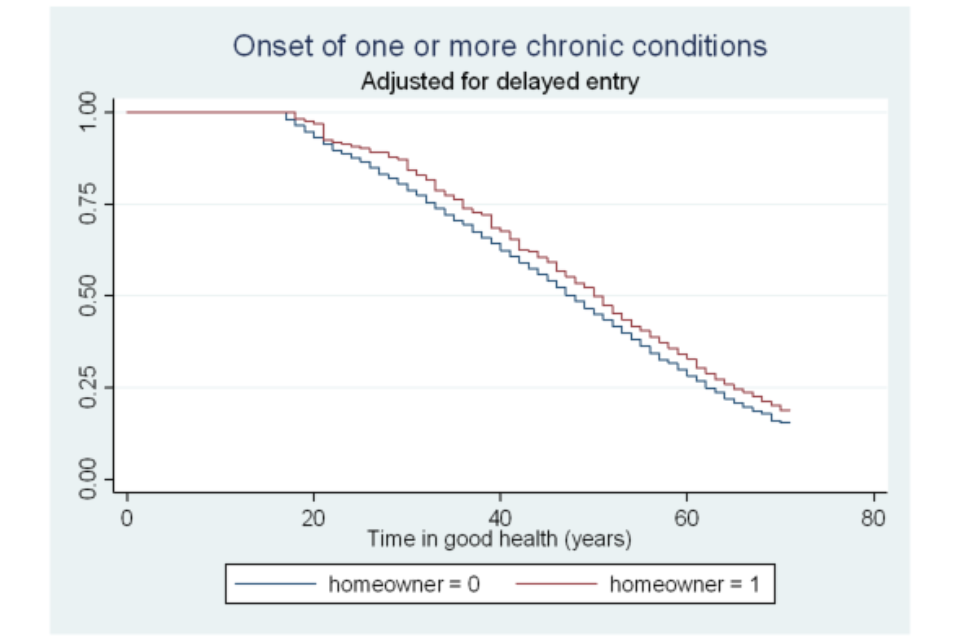

- examining durations of time in different states of health using survival analysis. Survival functions (estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method) and discrete-time proportional hazards (estimated by means of complementary log-log models) are used to analyse time spent in good and poor health. They are also used to investigate which individual characteristics and circumstances are associated with a higher likelihood of recovering from, or relapsing into, poor health

- exploring patterns of employment status and work conditions over time following a health transition using sequence analysis. The aim of the sequence analysis is to explore employment status and job satisfaction patterns experienced by individuals making a health transition. We look at these outcomes after the health transition as a sequence of self-reported outcomes. By doing this, we aim to explore how people’s labour market activity and satisfaction with work changes following a health shock

Key findings

Risk factors associated with work transitions following a health transition - the findings of a series of logistic regression analyses indicate that:

- an incident health problem is associated with a greater likelihood of job loss in the same period and, to a lesser extent, one year after. Among those who remained in employment following an incident health problem, some negative effects were observed, notably a greater likelihood of an individual becoming dissatisfied with their job

- the risk of job loss following an incident mental health problem is mitigated by having a university degree, working in a larger workplace (200 or more employees) and having a skilled job

- recovering from poor health is associated with a greater likelihood of becoming employed in the same period. This positive association of recovery with employment appears to be smaller than the negative association of an incident health problem with job loss

Durations of time in different states of health - the findings of the survival analysis indicate that:

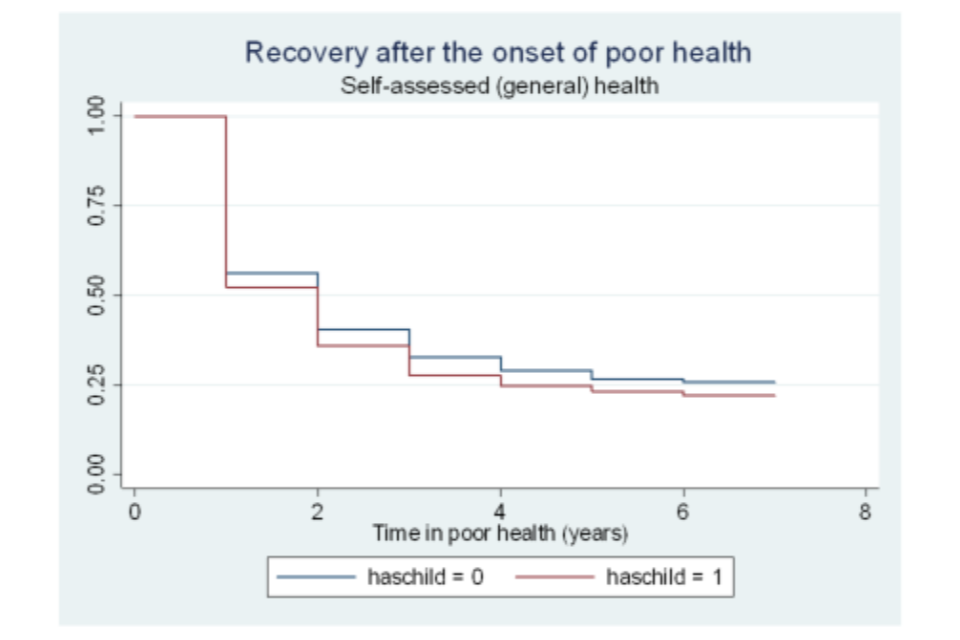

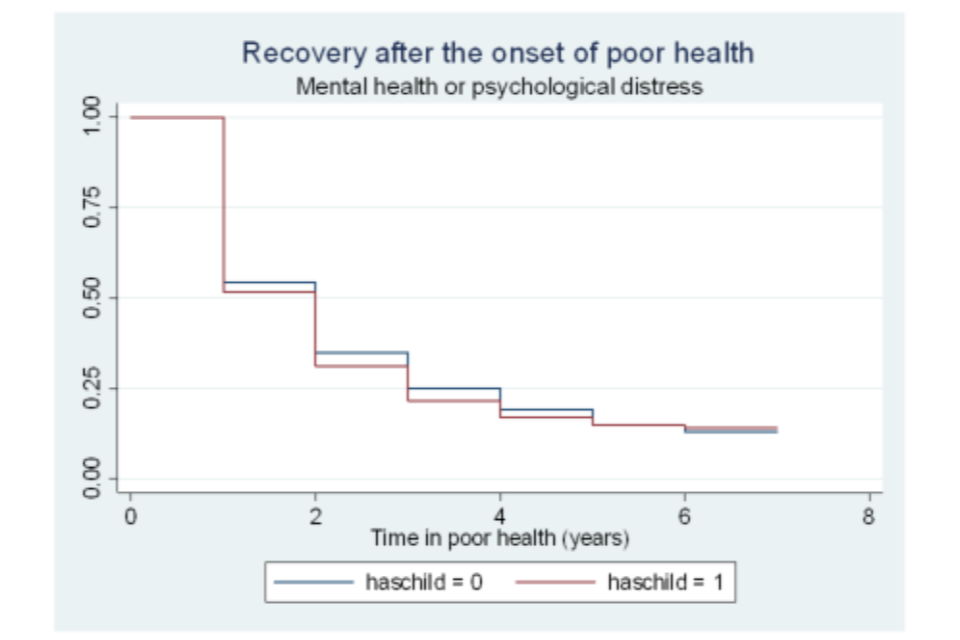

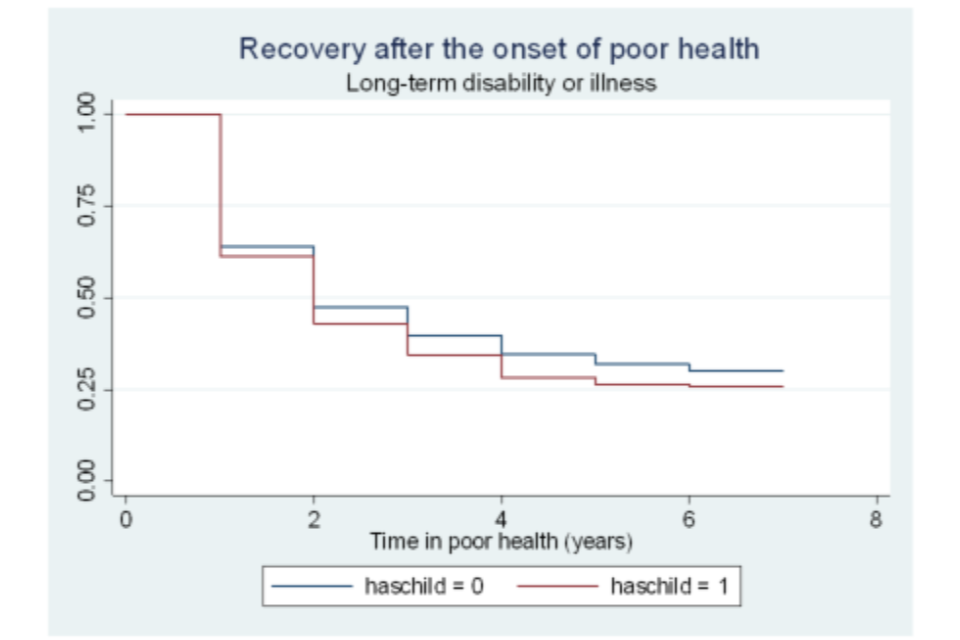

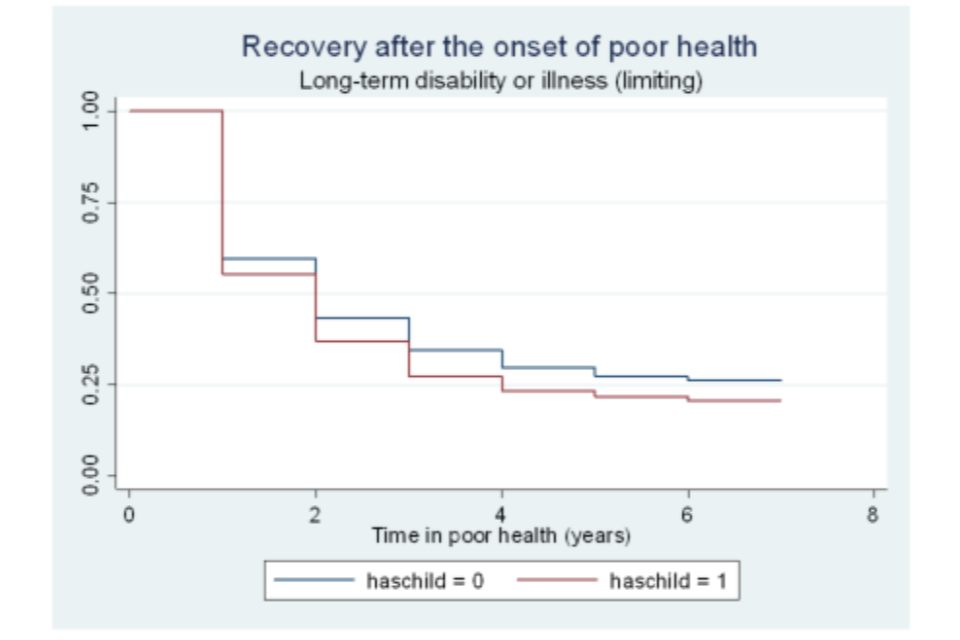

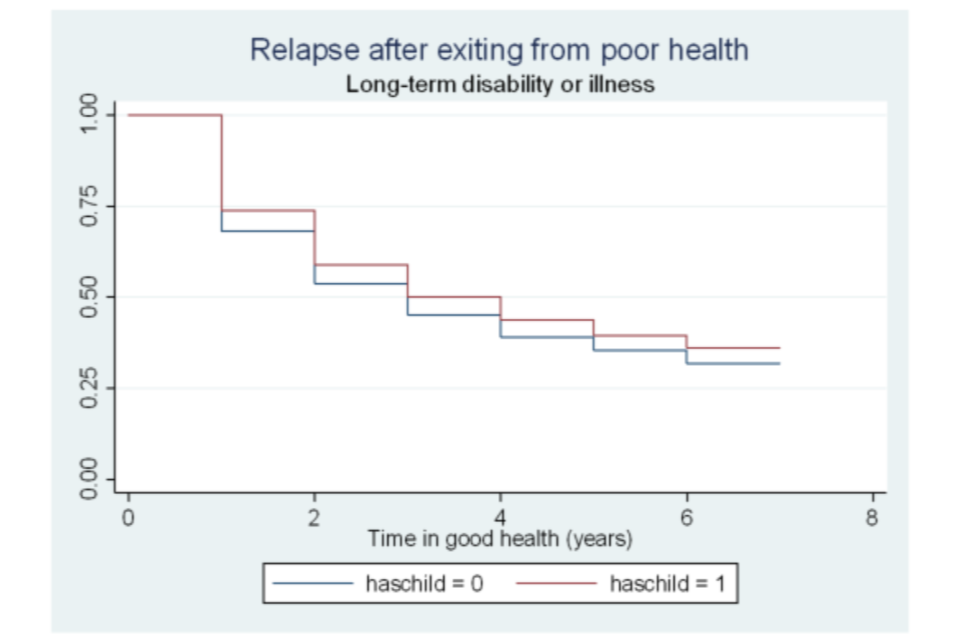

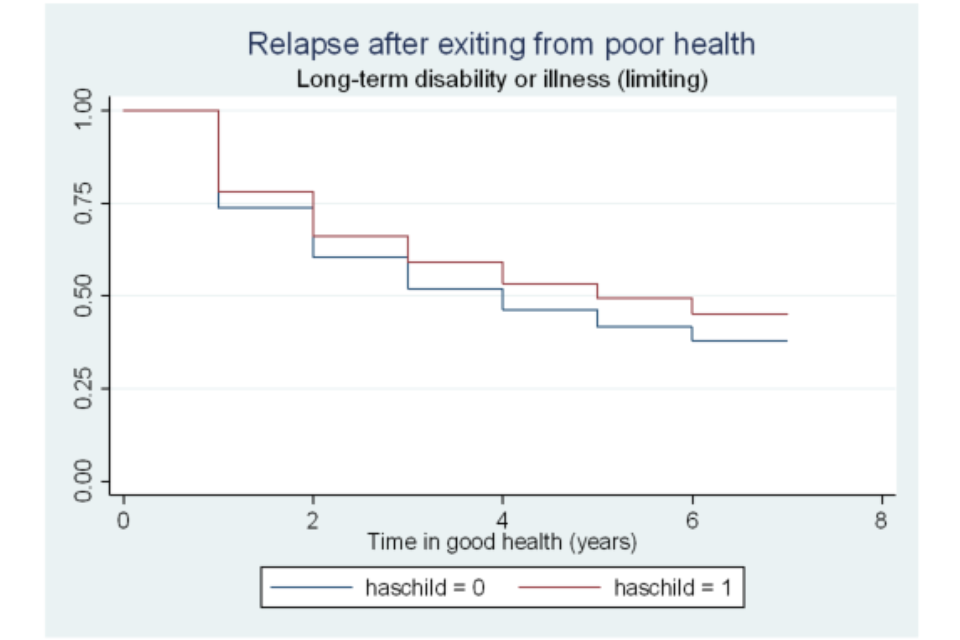

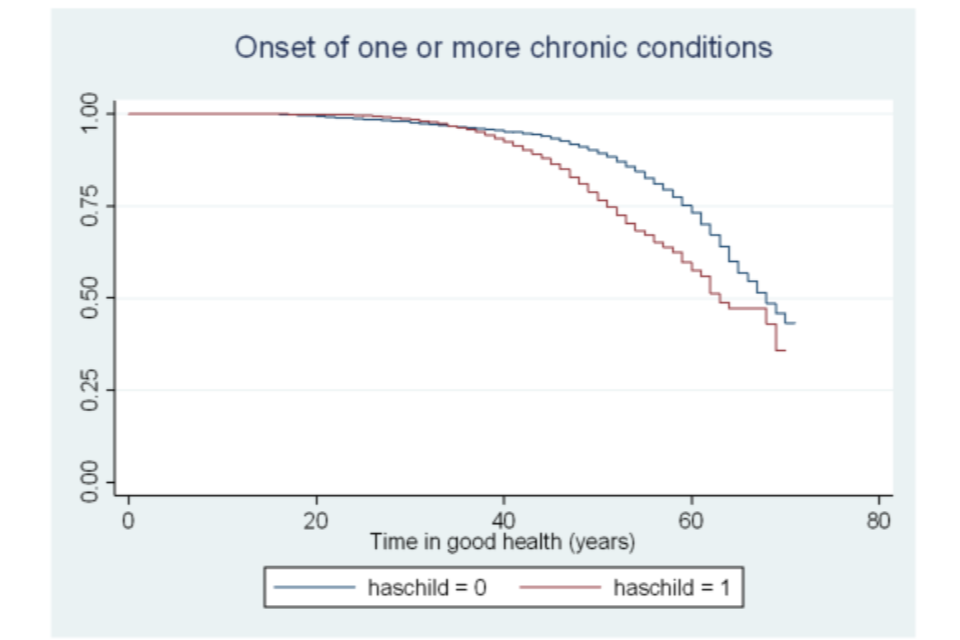

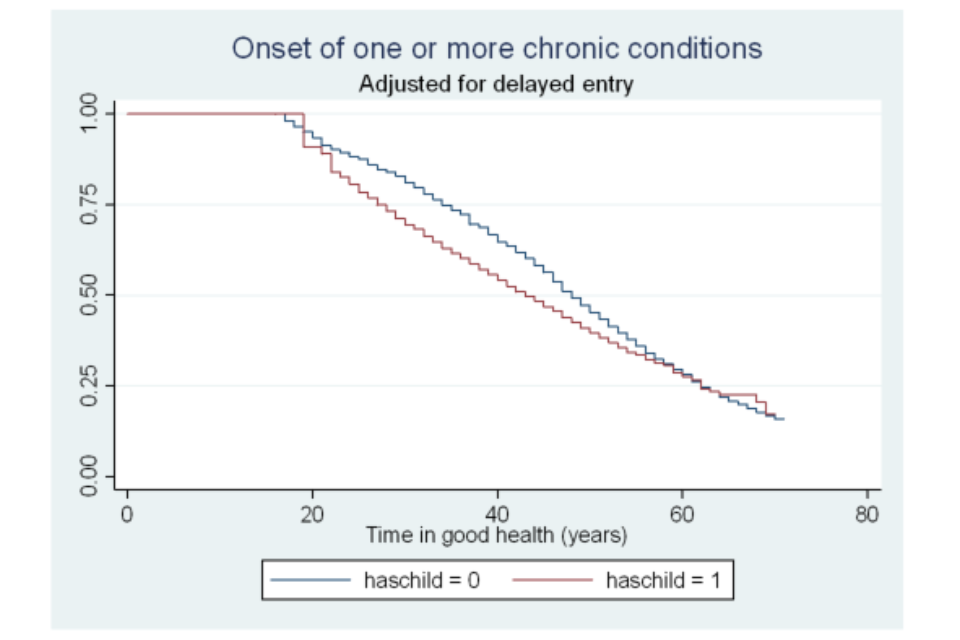

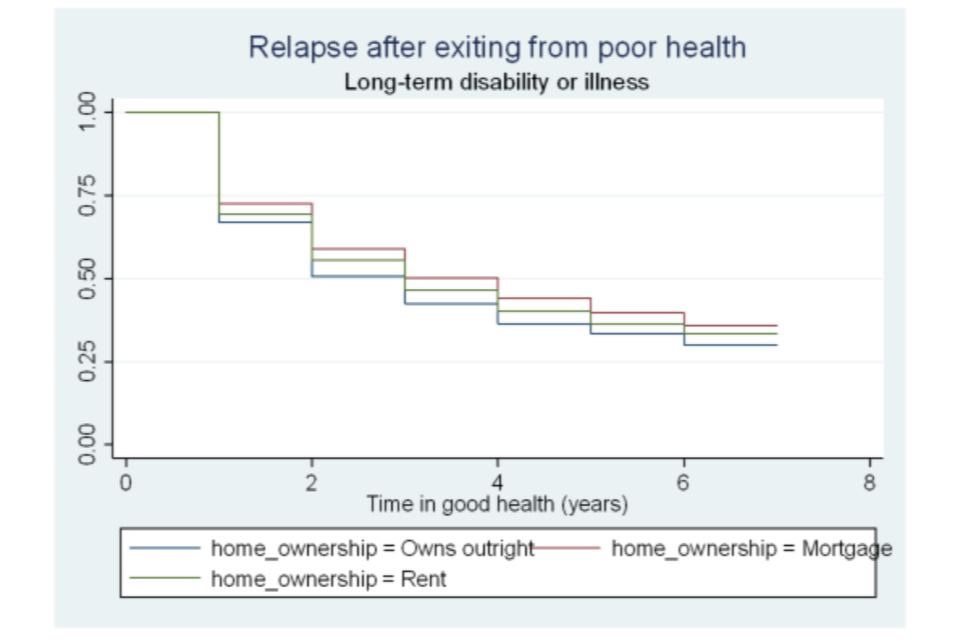

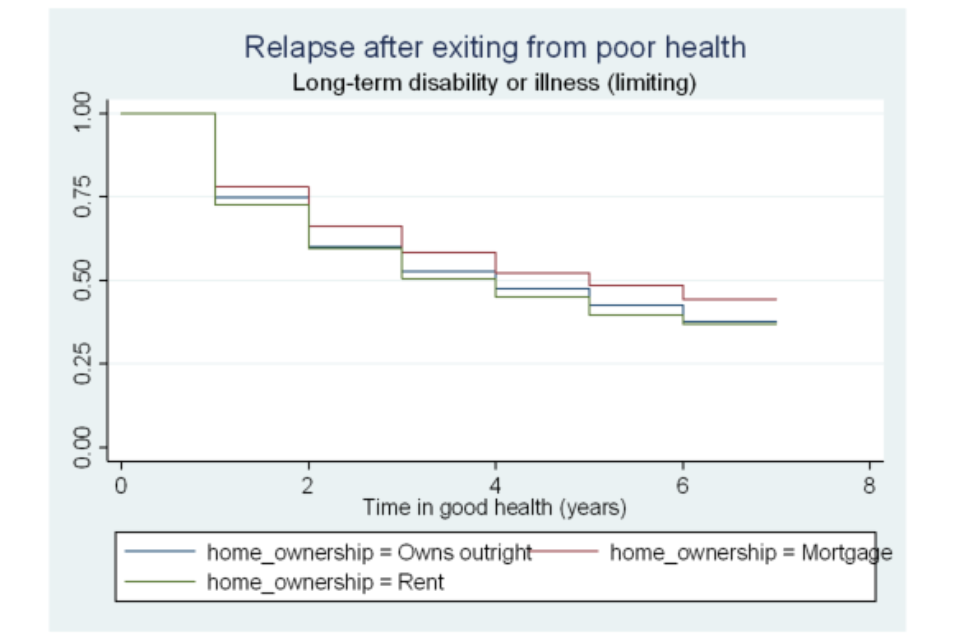

- for those affected by an incident health problem, there is a greater likelihood of recovery among certain groups including white people (compared with those from other ethnic groups), employed people, those with children under the age of 16 in the household, and home owners. In general, these groups are found to experience a faster recovery

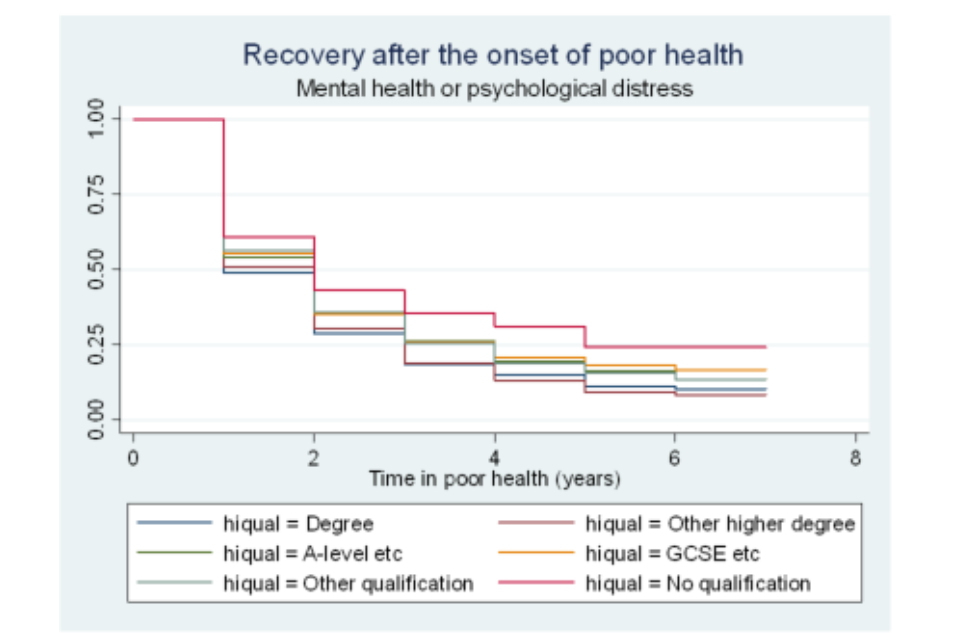

- younger people (16 to 24 year olds) are more likely to recover from incident health problems, and do so more quickly, than older groups. However, the opposite appears to be true where a mental health condition is concerned

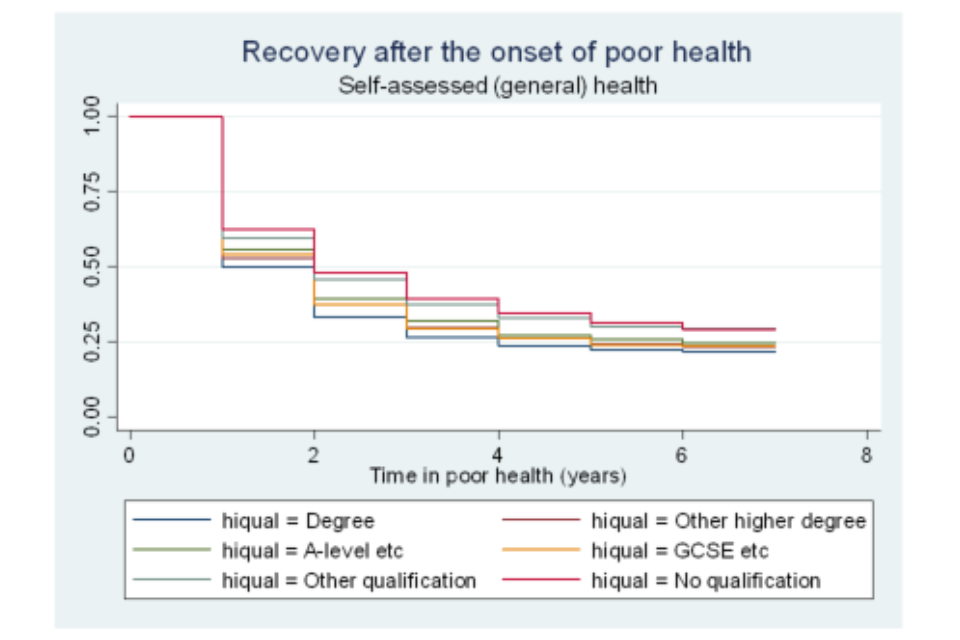

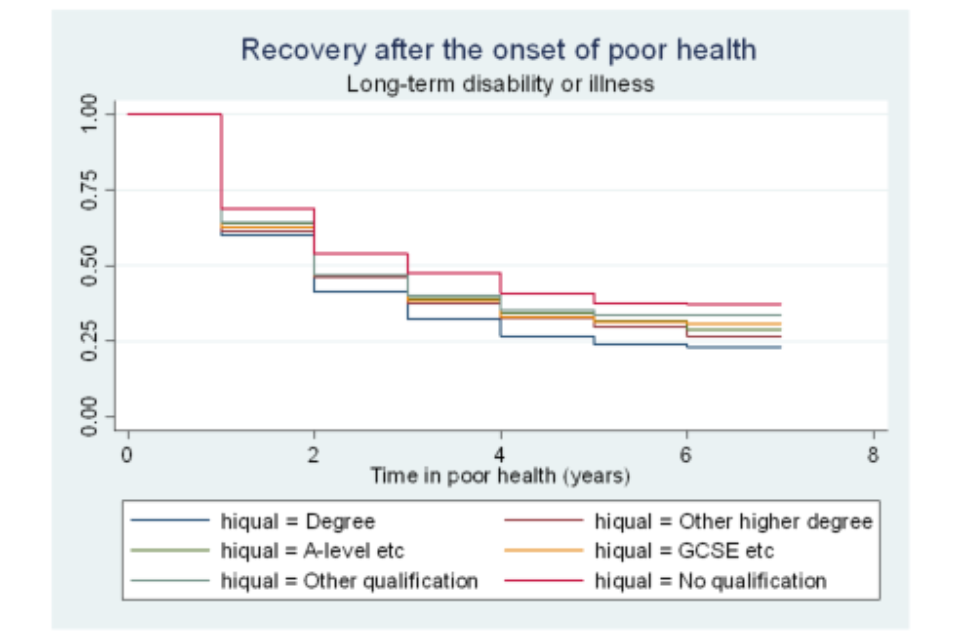

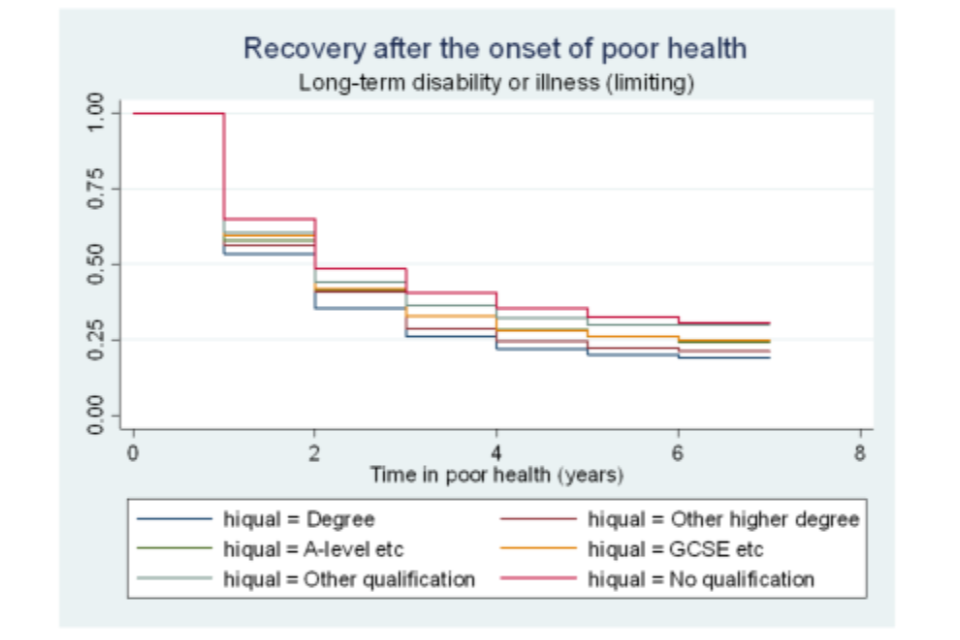

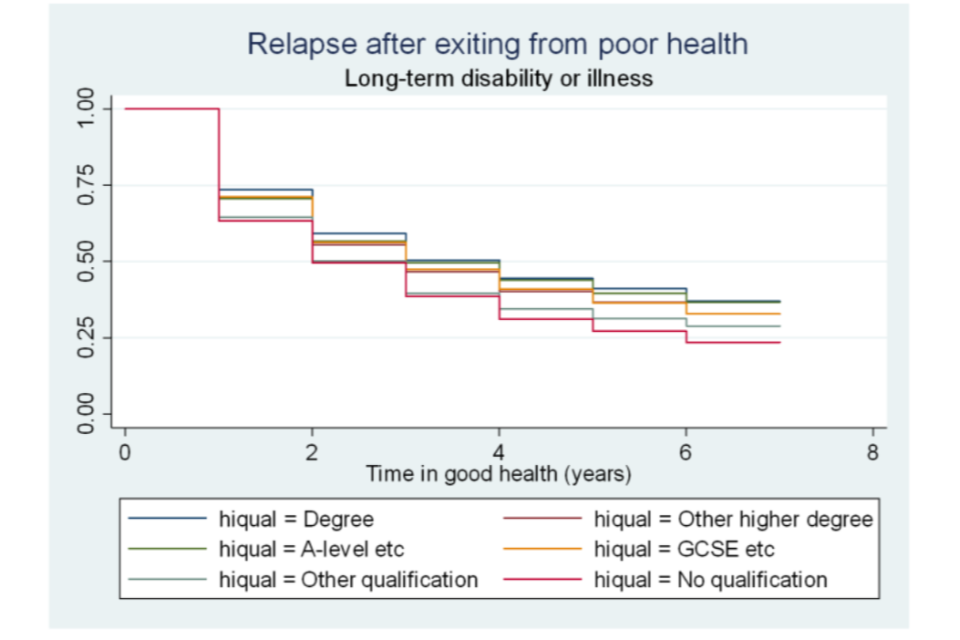

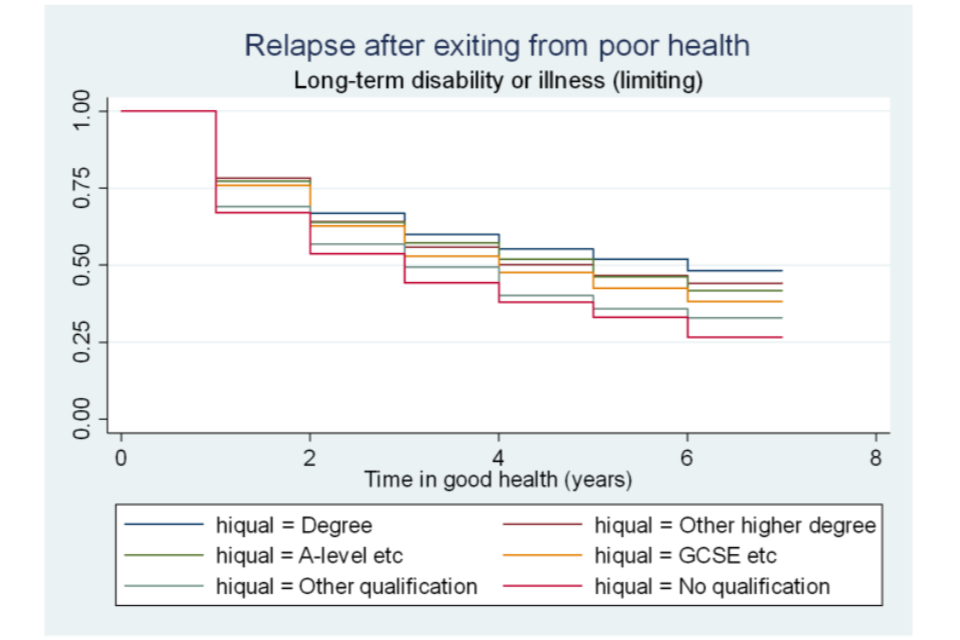

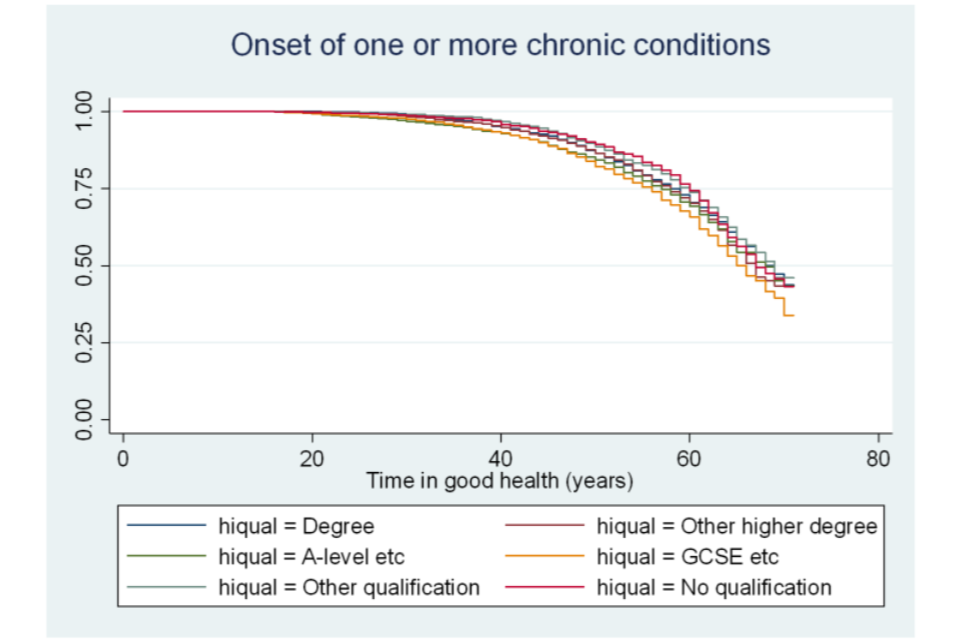

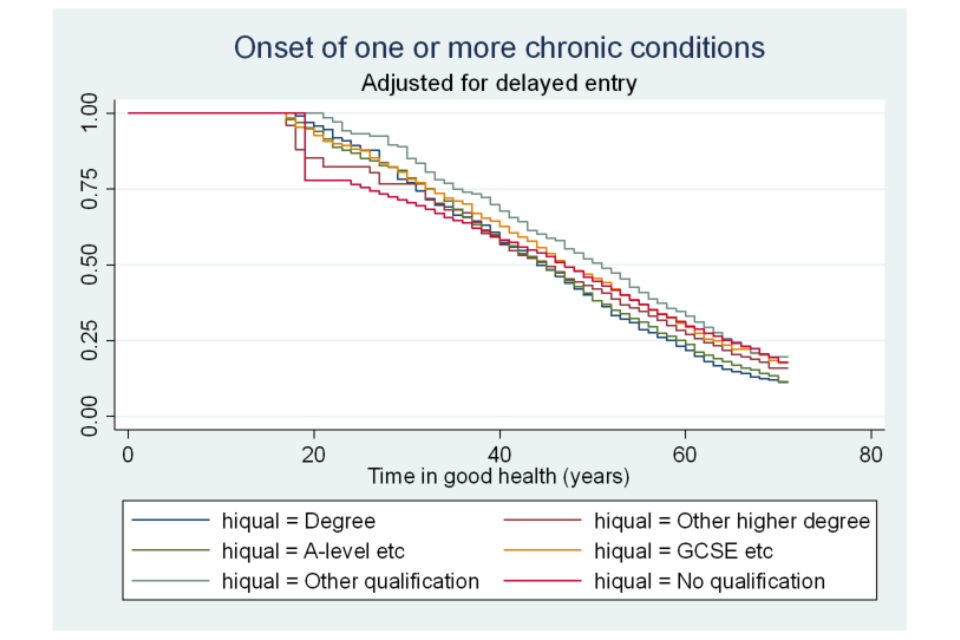

- people with a qualification (notably, a GCSE or degree) appear to recover from poor health more slowly, and be at greater risk of relapse, than those without any qualifications

- with the exception of mental health conditions, there is evidence suggesting that the higher the qualification the higher the likelihood of relapsing into poor health

- generally, the individual characteristics associated with a greater likelihood of recovering from an incident health problem are the same as those associated with a lower risk of relapse

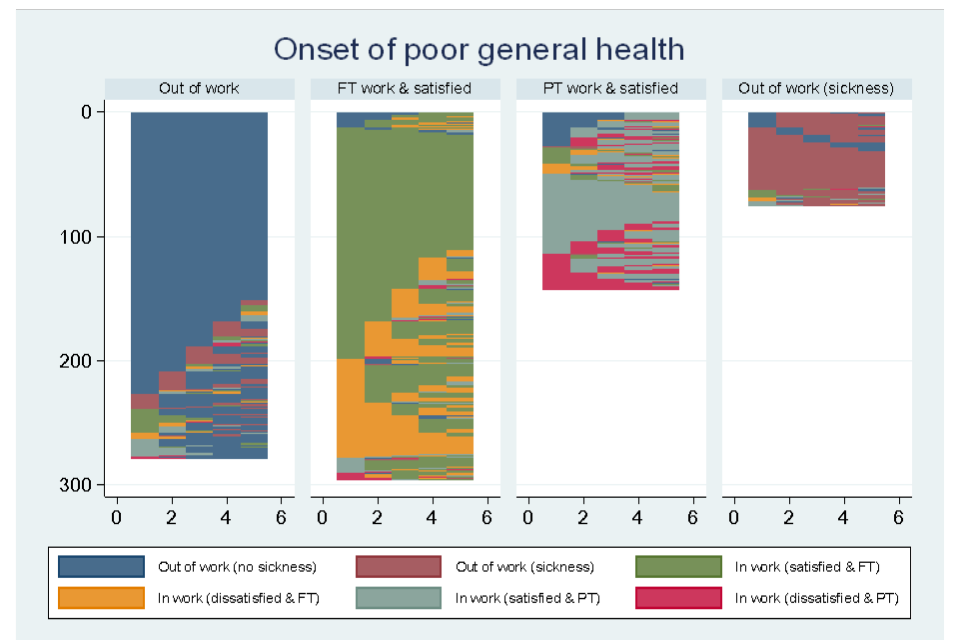

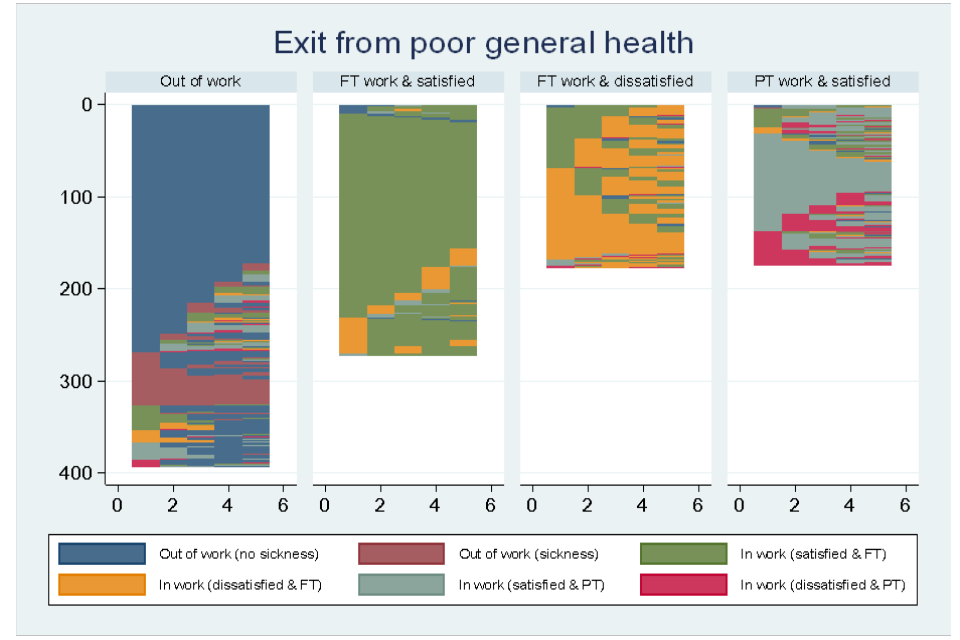

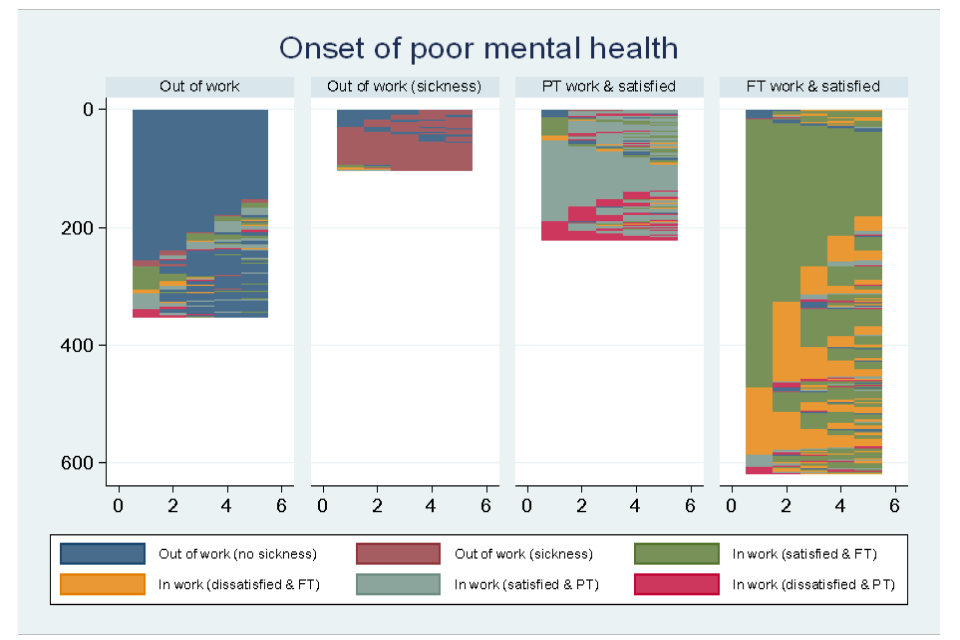

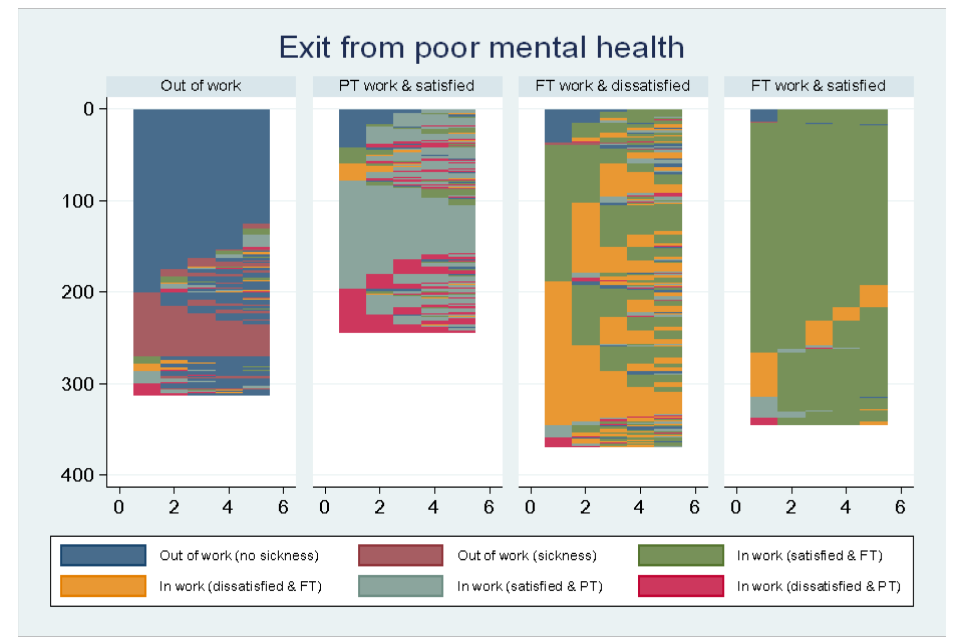

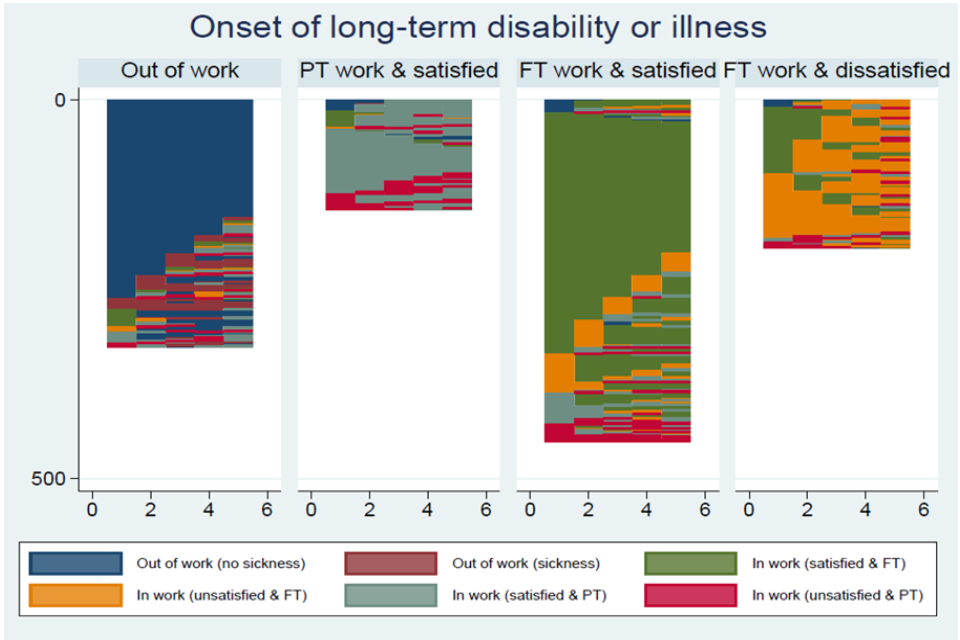

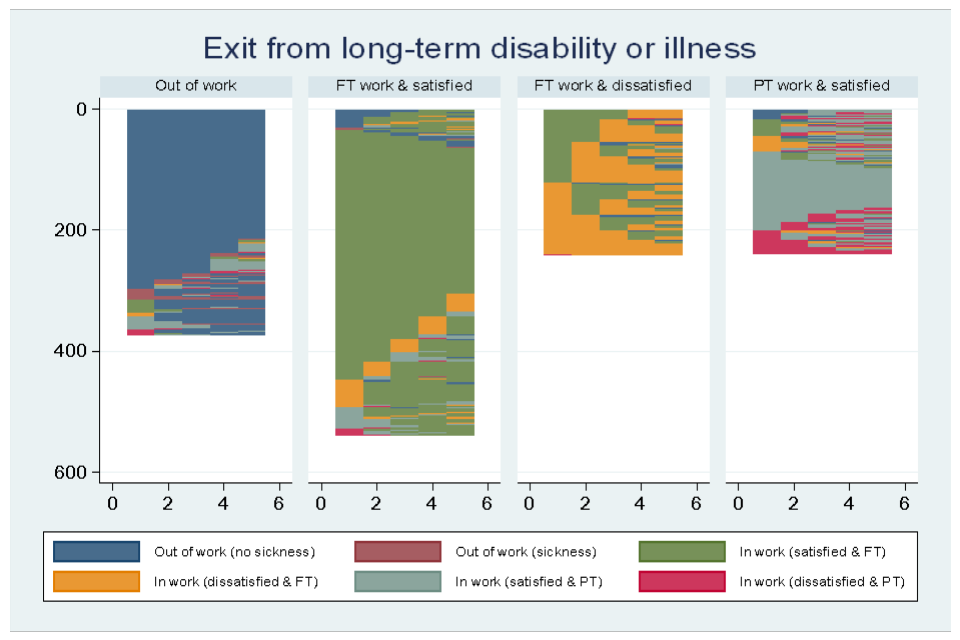

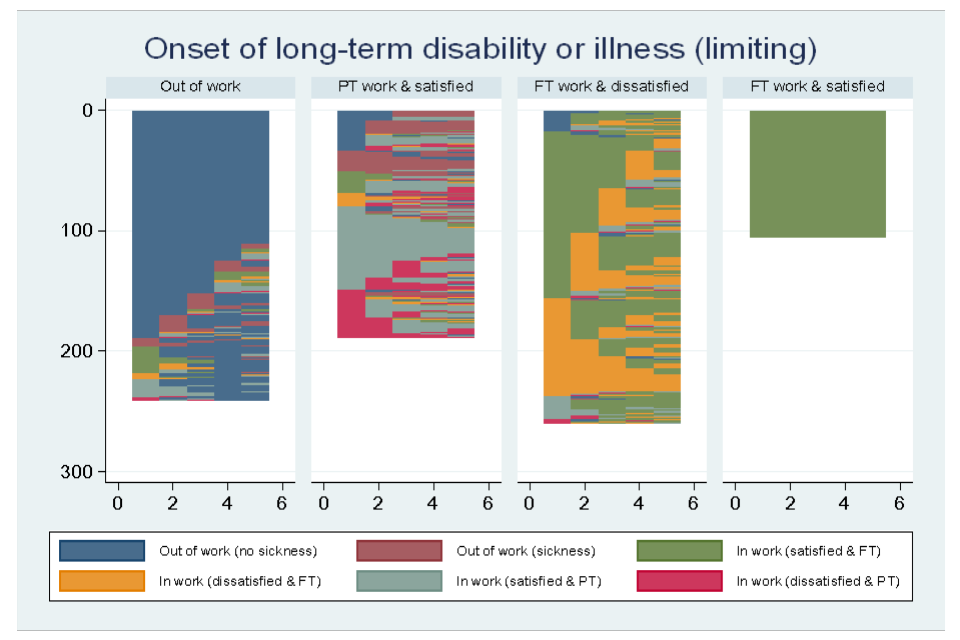

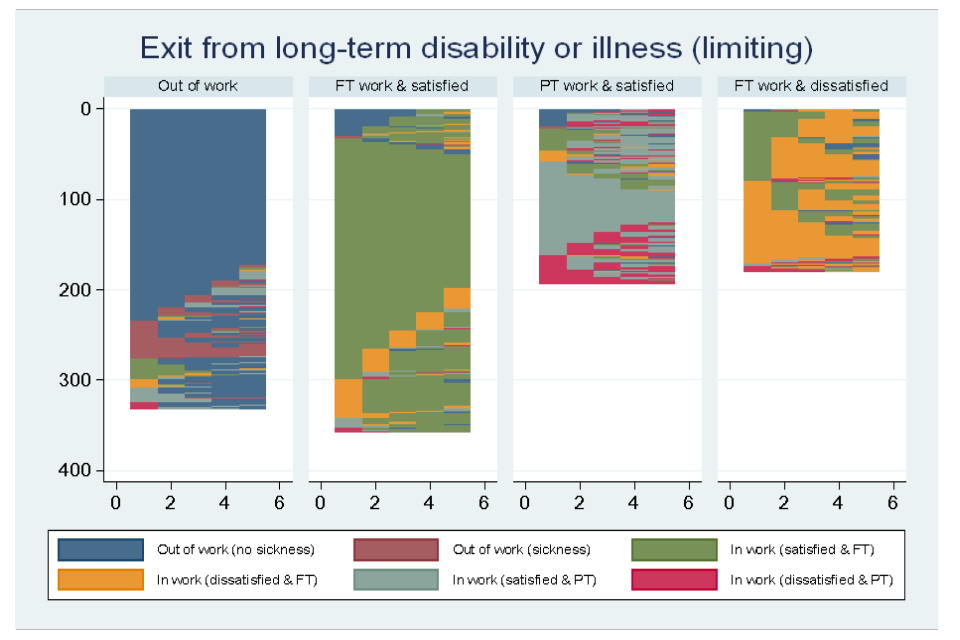

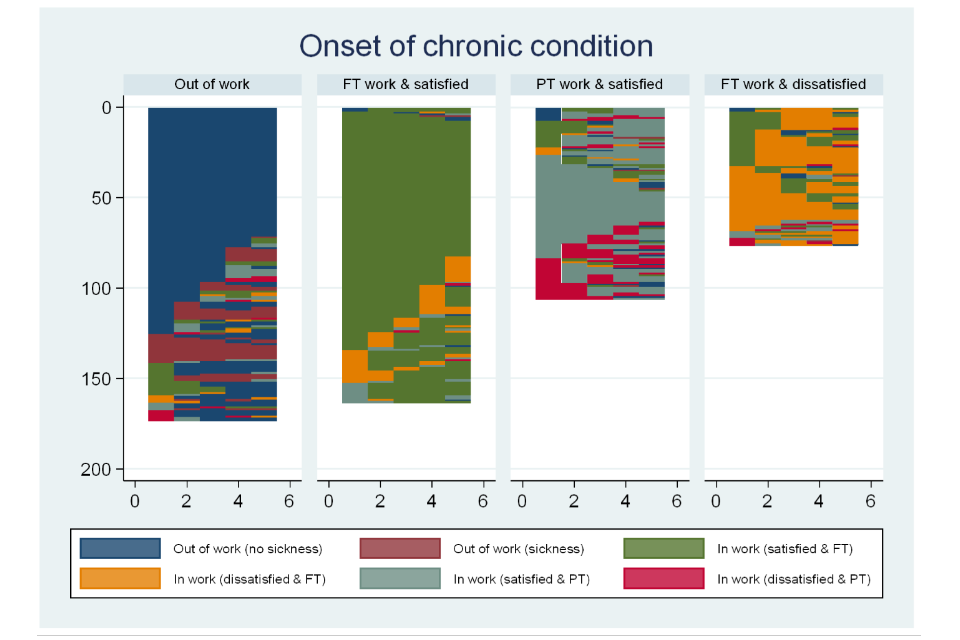

Patterns of employment status and work conditions following health transitions - the findings from the sequence analysis indicate that:

- patterns of work and job satisfaction appear similar regardless of the way in which health is measured

- around half of people experiencing a transition into poor general health remain in employment. These are equally split between people satisfied with their job and (transitorily or permanently) dissatisfied

- around half of people experiencing a transition into poor general health are out of employment and remain so for the period observed (5 years). Of those that are out of work, half report that their withdrawal from employment was because of poor health (at least temporarily)

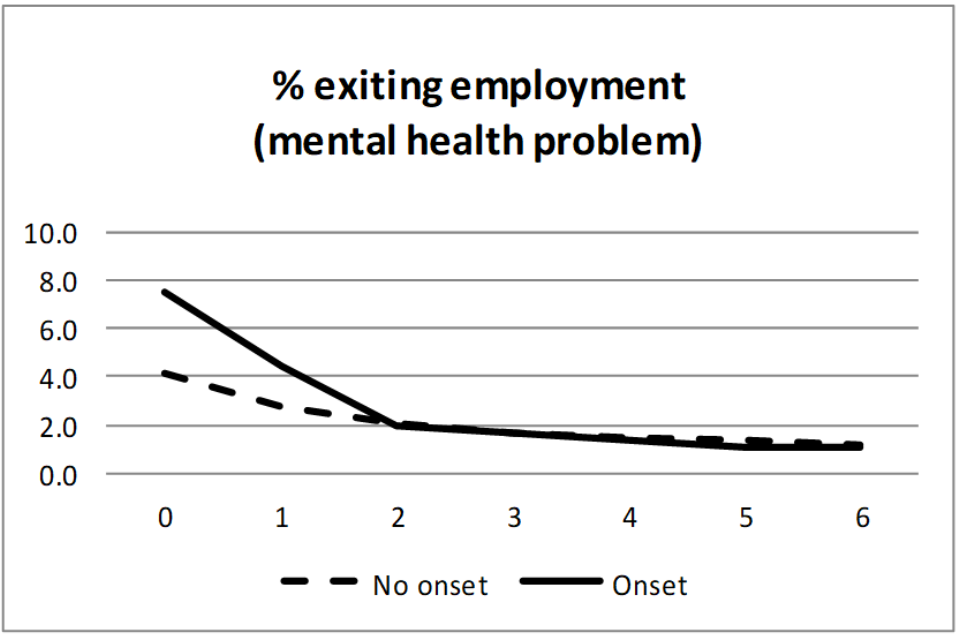

- findings are very similar across conditions, except for the onset of mental health problems, where a larger proportion is found to remain in full-time employment and, amongst them, a larger proportion are dissatisfied with work

Implications and recommendations for further research

While the impact of unemployment (and particularly long-term unemployment) on health has been researched extensively,[footnote 1] there is arguably less research that explicitly examines the effects of changes in health on employment outcomes. The present study provides an exploratory analysis of these effects, identifying important impact moderators like socio-economic group and workplace characteristics. The findings may help with consideration of how best to target interventions.

Whilst this study has focused on a few measures of work and health, and on a limited number of health and work transitions, a wide range of further issues could be explored. Examples of opportunities for further analysis include:

- examining how an individual’s occupational status and earnings develop in different scenarios, for example after they recover from ill-health (or remain in employment with a continued health problem)

- how adjustments in the workplace affect outcomes

- more complex transitions concerning co-occurring health conditions

- exploration of multiple transitions per individual

- relating the biomarkers collected in Understanding Society for a proportion of survey respondents to the self-identified health status responses underpinning this study to enrich measurement of different health states

Additionally, other datasets may be a valuable source for future analysis. For example, analysis of DWP administrative data about benefit claimants, (especially where linked with HMRC data on employment and earnings) might enable analysis of a larger scale study with finer granularity of time (where the annual periodicity of Understanding Society may be a drawback). Furthermore, with informed consent, linkage of bespoke health cohort studies with administrative employment data would be even more informative.

1. Introduction

This chapter describes the policy background to this study, and summarises the current state of empirical research on health and work transitions. It outlines the research objectives, the data and the statistical methods used.

1.1. Policy background

Disabled people fare worse in the labour market. Between April and June 2018, while the UK employment rate reached a historic high of 75.6%, only half of people with a disability or limiting health condition were in work. The disability employment gap (the difference between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people) has been stable at around 30 percentage points throughout the past decade, while the prevalence of disability and ill-health among the working-age population has been rising over time. Working age ill-health, which prevents people attending work or being in a job due to illness or disability, comes at a considerable cost to the UK economy estimated to be around £100 billion a year (Work and Health Unit, 2017).

To provide contextual evidence for the government’s strategy for improving employment outcomes among people with health conditions or disabilities, this study examines transitions (changes) in health and work status experienced by working-age people (16 to 64 year olds). It uses a large-scale longitudinal survey, Understanding Society (USoc), to provide fresh empirical evidence on the complex relationship between health and work transitions, which is arguably under-explored.

In 2017, at a time when there were 3.5 million disabled people in work, the UK government set a goal to see one million more disabled people in work over the next 10 years. ‘Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability (Work and Health Unit, 2017)’ set out in more detail the Government’s 10-year strategy to improve disability employment outcomes. This described the intent for action through employers, particularly on recruitment and retention of disabled people, the need to improve access to occupational health services, and measures to achieve a sustainable welfare and employment system co-ordinated with the health system and local communities.

The government’s 2017 command paper also acknowledged the importance of developing the evidence base to inform policy measures. Previously, the Black Review (2008) highlighted that many incapacity benefit claimants could have maintained and progressed in their jobs with the right support. The 2017 command paper placed emphasis on tailoring support to individual situations. Understanding the characteristics, circumstances, and health and work journeys of disabled people and those affected by ill health is therefore important to inform policy responses – both the targeting, and nature, of support and incentives needed to achieve better work outcomes.

1.2. Existing research on health and work transitions

There is extensive empirical research demonstrating that an individual’s likelihood of being in paid employment is negatively affected by poor health (for example, Blackaby et al., 1999; Kidd et al., 2000; Meltzer at al., 1995; Waddell and Burton, 2006). However, little is known about the complex dynamics of the relationship between health and work. We did not identify any previous studies which have examined the impact of a change in an individual’s health state (or ‘health transition’, such as the sudden onset of a mental health problem or of a chronic condition) and changes in their labour market status (‘work transition’ – for example, a move from employment to inactivity or unemployment). Recent research also suggests that for those who remain in work despite experiencing a health problem, work conditions are of paramount importance, as is the type of health condition experienced, so changes in these states should be considered. For example, Pacheco et al. (2012) suggest that those who suffer from physical pain are more likely to do casual (temporary or part-time) jobs, while people affected by depression are less likely to hold a permanent job while still remaining full-time.

A report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (Webber et al., 2015) is the first attempt to better understand employment transitions and in-work experiences of people affected by disability or ill-health.[footnote 2] Using longitudinal data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), the authors find that being in poor health (physical, mental or both) reduces the likelihood of experiencing positive employment transitions. Their analysis also suggests that individuals with a health condition or disability are more likely to be trapped in low-pay circles of labour market activity (lower-status jobs in terms of pay, conditions, security and development opportunities). While explicitly addressing employment dynamics (changes in labour market status and employment conditions) in their analysis, Webber et al. (2015) consider health in a static sense (in terms of whether an individual had poor health at any point in time), and thus the role of health transitions remains unexplored.

1.3. Research aims

In October 2018, the Work and Health Unit (a cross-government unit, jointly sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health and Social Care) commissioned the National Institute of Economic and Social Research to conduct research into health and work transitions. Specifically, the analysis sought to achieve the following research objectives:

- explore the statistical association between health transitions and work transitions, and attempt to provide indicative measures of the impact of the former on the latter

- identify the characteristics and circumstances of working-age individuals which moderate the impact of health transitions on work transitions (if any)

- investigate time-related aspects around health transitions, notably whether the duration of health transitions varies across different population subsets, and how individual characteristics affect this duration

- explore time patterns (sequences) of employment statuses and in-work conditions experienced by individuals following an initial health transition

In addition to achieving these specific research objectives, it is more generally expected that the research will contribute to the development of a wider framework to measure and monitor improvements in work and health outcomes over time and for different subgroups, defined by demographics and wider circumstances.

Note that, while important, the impact of work transitions on health transitions (reverse causality in the context of this analysis) was beyond the scope of this study and is not considered in this report. We acknowledge that for work and health transitions that occur in the same period it is not possible to remove the issue of reverse causality - a review of the wider literature on this phenomenon would help put the results of this study into broader context.[footnote 3] The analysis aims to assess whether (and, if so, to what extent) experiencing a health transition affects the likelihood of undergoing a work transition. More specifically, it seeks to explore the impact of negative health transitions on negative work transitions (for example, the effect that the onset of a chronic condition or mental health problem has on employment exit), and the impact of positive health transitions on positive work transitions (for example, the effect of exiting poor health on employment entry).[footnote 4]

1.4. Data and methods

The statistical analysis uses data from Understanding Society (USoc) to achieve the project objectives outlined in section 1.2. Using this data source meant that issues around work and health transitions could be explored for a large number of individuals over the decade spanning from 2009 to 2018. As explained in section 2.1, the choice of USoc over other data sources (notably, BHPS) was dictated by the need to observe health trends and patterns over a more recent time period.

Health transitions are changes in an individual’s health state as described in the Definitions section. Health is measured using 5 different constructs, which vary across a number of dimensions such as:

- the health condition itself (mental health or psychological distress, long-term disability or illness, chronic condition or general health);

- who reported it (with the exception of chronic conditions, which are diagnosed by a doctor, all other health indicators are self-assessed); and

- whether it entailed a functional impairment (a distinction is drawn between limiting and non-limiting long-term disabilities or illnesses)[footnote 5]

This results in defining health transitions in 5 alternative ways (one for each health construct). Work transitions are changes in an individual’s labour market status or in-work conditions/employment contract arrangements. The labour market statuses of interest are employment and activity, and the work conditions include hours worked (the analysis differentiates between part- and full-time jobs), contract length (temporary versus permanent jobs), pay level (high- versus low-pay jobs) and satisfaction (whether employees are satisfied with their jobs or not).

The findings illustrated in this report are obtained using different statistical methods, each tailored to address specific research questions:

- impacts are assessed using a multiple regression approach, whereby possible determinants of health transitions which are also thought to be predictive of work transitions are controlled for. Within the regression framework, interaction terms are used to explore the existence of moderators of the impact of health transitions on work transitions

- survival analysis methods are used to study time to recover from poor health, time to relapse into poor health and time to experience the onset of a chronic condition. This entails estimating survival functions and discrete-time duration models

- sequence analysis is used to identify the most common patterns of employment status and in-work conditions observed for people following the onset of, and exit from, poor health. The empirical clustering of sequences allows for a visual understanding of the size of the groups who experience each pattern

1.5. Report outline

Chapter 2 describes the data sources. Chapter 3 illustrates the statistical methods used for the analysis of health and work transitions. Chapter 4 presents the empirical findings. Finally, Chapter 5 summarises the main results and presents conclusions. Six appendices provide further detail on the methodology adopted and the results.

2. Data

This chapter gives an overview of the data sources and outlines the variables used in the analysis. Basic statistics on health transitions are presented, along with characteristics and labour market outcomes of those who experience health transitions.

2.1. Data sources

The analysis for this report is conducted using individual data from Understanding Society (USoc). Information from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) is also used to explore the extent to which USoc data are representative of the general population experiencing health transitions. This section provides a brief overview of USoc and the LFS.

2.2.1. Understanding Society (USoc)

Understanding Society, also known as the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS), is a longitudinal survey of around 40,000 UK households recruited between 2009 and 2011 (when the fieldwork for the first wave of interviews took place) and re-interviewed at around one-year intervals through either face-to-face interview or self-completion online survey. At the time of this study, 8 USoc interview waves had been implemented. USoc collects information on demographics and circumstances of individuals and their households (including work, health, income and education characteristics) with the aim of helping understanding of how social and economic change affects the wellbeing of the UK population in the long-run. Anonymised USoc data are publicly available for download from the UK Data Service.

Around 6,000 participants from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), USoc’s predecessor which started in 1991, took part in USoc.[footnote 6] Although this provided the opportunity to link the 2 studies to create a longer panel of subjects, important changes were made, notably to questions affecting the health variables critical to this analysis. The lack of continuity between the 2 surveys meant that a decision had to be made as to which data source could be used for analysis of health and work transitions. Despite the shorter time period, USoc was chosen primarily because it enabled a more current analysis of trends and patterns in health and work.

Unless otherwise stated, the analysis for this report was conducted using data for working-age individuals, defined as people aged between 16 and 64 (inclusive), given the focus of the research on the study of work transitions.

2.1.2. Labour Force Survey (LFS)

The UK LFS is a nationally representative quarterly household survey containing a variety of labour market statistics that has been running since the mid-1970s. In this report we only use the data source as a consistency validation check for the frequency of health transitions observed in USoc. The main data source used for this purpose is the 5-quarter longitudinal LFS.

The quarterly cross-sectional LFS has information about health conditions (for example, musculoskeletal conditions, heart conditions and depression). These are not mutually exclusive - people can report up to 17 conditions at the same time. The longitudinal survey only keeps the 3 main conditions out of the 17 surveyed every wave.

The data are linked to create a balanced panel of about 4,000 people observed for one year, which is analysed with descriptive methods to provide checks on whether the volumes of health shocks reported in the USoc data are consistent with those reported in the LFS.

The main health problems recorded in the LFS generally differ from those reported in USoc, with the exception of 3 chronic conditions (diabetes, depression and epilepsy), which are consistent across the 2 surveys. We compare the frequency of health transitions related to these 3 conditions between LFS and USoc as a proxy for general consistency of health transition volumes (see Appendix 2). It does not appear that USoc underreports the extent of health transitions relative to the LFS, which is a larger survey and arguably more nationally representative than USoc.

2.2. Main variables

The variables used for the analysis of work and health transition can be divided into 3 groups:

i. health-related variables: those capturing the health state of USoc respondents

ii. work-related variables: those indicating an individual’s labour market status or work conditions

iii. other variables: those related to an individual’s demographics or general circumstances

This section provides detail on these 3 sets of variables.

2.2.1. Health-related variables

The analysis for this report used 5 indicators of health, each capturing a different aspect of an individual’s health state. These indicators, used to define health transitions (see section 2.3), are as follows:

- self-assessed general health: in USoc, survey respondents rate their health as poor, fair, good, very good or excellent. Those who reported good or better health at interview were classified as being in good health, while those who said that their health was poor or fair were considered as having poor health[footnote 7]

- mental health or psychological state: we describe someone as having a mental health condition or in psychological distress if their General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) score was 3 or higher[footnote 8]

- self-assessed long-standing illness or disability: in USoc, individuals are asked whether they have any long-standing physical or mental impairment, illness or disability (without specifying what the issue is). Anyone who answered positively to this question is classified as being in poor health, while those who answered negatively are regarded as being in good health

- self-assessed long-standing illness or disability entailing a functional impairment (‘limiting’): in USoc, those who report having a long-standing illness or disability (previous item) are asked whether this illness/disability affects their daily life across 12 functional impairments.[footnote 9] All individuals who indicated at least one functional impairment are considered as being in poor health. This health indicator is consistent with the Equality Act 2010 and the Government Statistical Service’s harmonised definition of disability (long-term condition affecting an individual’s ability to carry out day-to-day activities)

- any diagnosed chronic conditions: survey respondents are considered to have a chronic condition, and therefore be in poor health, if they indicated that a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed them with one or more of 17 conditions listed.[footnote 10] A subject was considered to be in good health if they did not report any of these health problems[footnote 11]

2.2.2. Work-related variables

The following 6 work-related indicators are used to capture work transitions:

Transitions into and out of work/activity

- employment: an individual is considered employed if, at the interview date, they reported being a paid employee (full- or part-time), self-employed, on maternity leave, on a government training scheme, in unpaid family business or on an apprenticeship (the categories are mutually exclusive and each respondent can only indicate one). This definition of employment attempts to match that used by the ONS (for example, in the UK Labour Market statistics bulletin), which in turn follows guidelines set out by the International Labour Organisation (ILO)[footnote 12]

- economic activity: an individual is considered as economically active if, at the time of interview, they reported being employed (based on the definition above) or stated that they are unemployed but have actively been looking for a job in the last 4 weeks

Transitions whilst remaining in work

- job satisfaction: individuals who reported having worked in the last week, or not having worked last week but having a job, rate how satisfied they are with their present job. Those who report being somewhat satisfied, mostly satisfied or completely satisfied were classified as being satisfied

- pay: respondents are considered to be in a low-pay job if their hourly pay is below two-thirds of the wave-specific median hourly pay[footnote 13]

- temporary or permanent job: binary indicators are used to capture each

- full-time or part-time work: self-employed and paid-employees are considered to be in a full-time job if their weekly working hours exceeded 30 hours and in part-time work if they work 30 hours or less

2.2.3. Other variables

In addition to the health and work-related variables, the analysis used variables capturing the following demographics and circumstances of individuals:

- gender

- age: the focus of this study is on the working-age population so ages range between 16 and 64. The age categories 16 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 49, 50 to 59 and 60 to 64 are also used

- ethnicity: a binary indicator denoting whether the individual’s ethnicity is white or non-white[footnote 14]

- highest educational qualification: 6 categories, from the highest to the lowest: Degree, Other higher qualification, A-level or equivalent, GCSE or equivalent, Other qualification and No qualification

- marital status: dichotomous variable indicating whether the individual is married or in a civil partnership, as opposed to widowed, divorced or never married

- whether the respondent has any children in the household aged under 16: Yes/No

- home ownership: 3 binary variables were used, denoting whether the individual owns the property in which they live outright, through mortgage, or is renting it

- region of residence: 12 Government Office Regions - North East, North West, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England, London, South East, South West, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland[footnote 15]

For those employed, in addition to the variables listed in section 2.2.2 (used to define work transitions), the following work-related characteristics were also considered:

- occupation: 6 categories - professional, managerial and technical, skilled non-manual, skilled manual, partly skilled, and unskilled

- workplace size: 3 binary indicators are used, denoting whether the workplace in which the individual works has 1 to 24, 25 to 199 or over 200 employees[footnote 16]

2.3. Health and work transitions

2.3.1. Health transitions and patterns in USoc

For the purpose of this report a health or work transition is defined as a change in an individual’s health state (health transition) or labour market status/working conditions (work transition) between 2 consecutive USoc waves.[footnote 17] For example, if someone reports being in good health in their Wave 1 interview and in poor health in their Wave 2 interview then we can infer that they experienced a negative health transition at some (unspecified) point between the 2 interview dates. This is, of course, a simplification as we acknowledge that in reality multiple health transitions may have taken place between the 2 consecutive USoc waves. The exact time that the change in the individual’s health status happened remains unknown.

Table 2.1 shows the numbers of individuals who experienced negative and positive health transitions (‘Onset of poor health’ and ‘Exit from poor health’, respectively), and the numbers exhibiting other health patterns (‘Continuous good health’, ‘Continuous poor health’ and ‘Not classifiable’). These numbers are expressed as averages across the 7 transition periods observed in USoc (Wave 1 to Wave 2, Wave 2 to Wave 3, Wave 3 to Wave 4, Wave 4 to Wave 5, Wave 5 to Wave 6, Wave 6 to Wave 7, and Wave 7 to Wave 8). The table also shows what proportion of the (average) total number of individuals observed between 2 consecutive USoc waves each number represents.

Individuals classified as ‘Continuous good health’ are observed as being in good health at both a given wave and the next, while those who report poor health at both time points are defined as ‘Continuous poor health’. The ‘Not classifiable’ category is a residual group including all those whose health state is unknown at either or both interview dates. All individuals across the 5 categories considered are of working age at the point of transition. Health transitions and patterns are derived using each of the 5 health variables discussed in section 2.2.1:

- self-assessed (general) health

- mental health or psychological state

- self-assessed long-standing illness or disability

- self-assessed long-standing illness or disability entailing a functional impairment

- one or more diagnosed chronic conditions

The transition ‘Exit from poor health’ could not be explored for the construct ‘One or more chronic conditions’ because chronic conditions are persistent by definition.

As shown in Table 2.1, over 30,000 people are observed in any 2 consecutive USoc waves. The most frequently observed health transitions experienced by these individuals concerned onset of, and exit from, poor mental health/psychological state (almost 9% of the total sample, nearly 2,700 people). Smaller proportions were found to have experienced onset of, and exit from, self-assessed long-standing illness or disability (8.4% and 7.7%, respectively). Less than 6% experienced onset of, and exit from, poor self-assessed (general) health, and the same figure is observed when the health construct in question is a long-standing illness or disability entailing a functional impairment.

As expected, the most frequent pattern is observed for ‘Continuous good health’, which ranges between 54% and 76% (between some 16,000 and 23,000 individuals), depending on the health construct considered. The proportion of individuals classified as ‘Continuous poor health’ shows a certain degree of variability across the 5 health constructs considered, ranging between 9% (mental health) and 30% (chronic conditions).

Table 2.1 Health transitions and patterns (average counts and percentages across the 7 transition periods)

Health construct: Self-assessed (general) health:

| Health transition or pattern | Average count | Average percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of poor health | 1,811.4 | 5.9 |

| Exit from poor health | 1,684.1 | 5.5 |

| Continuous good health | 23,113.7 | 76.0 |

| Continuous poor health | 3,206.1 | 10.5 |

| Not classifiable | 541.1 | 1.9 |

| Total | 30,356.6 | 100.0 |

Health construct: Mental health or psychological state:

| Health transition or pattern | Average count | Average percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of poor health | 2,657.40 | 8.8 |

| Exit from poor health | 2,682.70 | 8.9 |

| Continuous good health | 16,158.70 | 53.5 |

| Continuous poor health | 2,763.00 | 9.1 |

| Not classifiable | 6,094.70 | 19.7 |

| Total | 30,356.60 | 100 |

Health construct: Self-assessed long-standing illness or disability:

| Health transition or pattern | Average count | Average percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of poor health | 2,534.4 | 8.4 |

| Exit from poor health | 2,345.0 | 7.7 |

| Continuous good health | 19,219.9 | 63.3 |

| Continuous poor health | 6,202.3 | 20.4 |

| Not classifiable | 55.0 | 0.2 |

| Total | 30,356.6 | 100.0 |

Health construct: Self-assessed long-standing illness or disability entailing a functional impairment

| Health transition or pattern | Average count | Average percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of poor health | 1,765.9 | 5.9 |

| Exit from poor health | 1,614.9 | 5.3 |

| Continuous good health | 23,039.7 | 75.9 |

| Continuous poor health | 3,306.9 | 10.9 |

| Not classifiable | 629.3 | 2.0 |

| Total | 30,356.6 | 100.0 |

Health construct: One or more diagnosed chronic conditions

| Health transition or pattern | Average count | Average percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of poor health | 884.7 | 2.9 |

| Exit from poor health | NA | NA |

| Continuous good health | 20,268.4 | 66.6 |

| Continuous poor health | 9,203.4 | 30.5 |

| Not classifiable | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 30,356.6 | 100.0 |

Source: authors’ calculations based on data from Understanding Society.

In general, only a very small proportion (2% of respondents or less) cannot be classified into any transition/pattern type due to missing information about their health. However, the proportion is much higher for the mental health construct (almost 20%). Given that poor mental health tends to be under-reported, the proportion who report experiencing an onset of poor mental health (around 9%) is likely to be an underestimate of the real figure. As a consequence, the impact estimates for the onset of poor health in general, and poor mental health in particular, illustrated in Chapter 4 are likely to underestimate the real impact.[footnote 18]

2.3.2. Population at risk of making a transition

While identifying someone who experiences a specific health or work transition is straightforward, defining the group of people who could have experienced a transition but do not (providing the pool of potential comparators ‘at risk’ to be used in the estimation of impacts) is more problematic. For example, if our focus is on transitions from good to poor health, among those who do not experience such transitions we can include people categorised as ‘Continuous good health’, ‘Continuous poor health’ and ‘Not classifiable’. Comparability between people who experience onset of poor health and people who are continuously in poor health (or between those who experience exit from poor health and individuals continuously in good health) is questionable as, it would be argued, the latter are not at risk of experiencing the transition in the first place: the 2 groups exhibit different health states to start with.[footnote 19] For this reason, unless otherwise stated, in the remainder of the report when we contrast individuals who experience a given health transition and individuals who do not, the latter group will only be comprised of people at risk of experiencing the transition in question.

Table 2.2 shows the numbers of individuals experiencing negative and positive health transitions (onset of, and exit from, poor health, respectively) for each of the 5 health constructs, and the sizes of the populations at risk of making the transitions (in brackets). The table also indicates what percentage of the at-risk population the individuals who make the transition represent. Also in this case, figures are expressed as averages across the 7 transition periods observed in USoc.

With regards to negative health transitions, 1 in 7 (14.1%) individuals at risk of experiencing onset of a mental health problem or psychological distress (almost 19,000 people) actually experienced one, while almost 1 in 8 (11.7%) of those at risk of a long-standing illness or disability onset (nearly 22,000 people) experienced one. Onset of (self-assessed) poor health was experienced by around 1 in 14 individuals at risk, and a similar proportion was observed for onset of a (limiting) long-standing illness or disability. Only 1 in 25 individuals (4.1%) at risk of experiencing onset of a chronic condition developed one or more conditions.

Compared to negative health transitions, positive health transitions (exits from poor health), are observed for much larger proportions of the populations at risk. For example, 1 in 2 (49.3%) individuals at risk of recovering from poor mental health actually experienced an improvement in their mental health state within one year. Among those at risk of exiting poor (self-assessed) health, 1 in 3 experienced the transition, and the same was true when poor health is defined based on a (self-assessed) long-standing illness or disability. When the illness was classified as limiting, 1 in 4 among the at-risk population was found to have exited poor health. The larger proportion of individuals experiencing positive health transitions compared to negative health transitions is attributable to a much smaller base (sample size of the at-risk population). As we saw in Table 2.1, the pattern ‘Continuous poor health’ is not as frequent as the pattern ‘Continuous good health’, as most survey respondents are in good health.

Table 2.2 Individuals experiencing each health transition as a percentage of the population at risk of making the transition (averages across the 7 transition

| Negative health transition | Average Count | Average Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of poor (self-assessed) health | 1811.4 (24,925.1) | 7.2 |

| Onset of mental health problem/psychological distress | 2657.4 (18,816.1) | 14.1 |

| Onset of (self-assessed) long-standing illness or disability | 2534.4 (21,754.3) | 11.7 |

| Onset of (self-assessed) long-standing illness or disability entailing a functional impairment | 1765.9 (24,805.6) | 7.2 |

| Onset of one or more (diagnosed) chronic conditions | 884.7 (21,153.1) | 4.1 |

| Positive health transition | Average Count | Average Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Exit from poor (self-assessed) health | 1684.1 (4,890.3) | 34.3 |

| Exit from mental health problem/psychological distress | 2682.7 (5,445.7) | 49.3 |

| Exit from (self-assessed) long-standing illness or disability | 2345.0 (8,547.3) | 27.3 |

| Exit from (self-assessed) long-standing illness or disability entailing a functional impairment | 1614.9 (4,921.7) | 32.6 |

Source: authors’ calculations based on data from Understanding Society

2.3.3. Characteristics of those who experience health transitions

The impact of health transitions on work transitions is defined as the difference between the proportions experiencing work transitions among individuals who undergo health transitions and among individuals who do not. However, meaningful comparisons must take into account any important, systematic differences between these 2 groups, particularly in the period prior to the health transitions (at the baseline), that may explain differences in the likelihood of undergoing the transitions.

Tables 2.3 and 2.4 compare individuals who experience onset of poor health and exit from poor health, respectively, with those who do not, across a range of characteristics observed immediately before the health transitions take place (specifically, at the first of the 2 waves defining each transition). In the tables, instances in which the proportion with a given characteristic differs between the 2 groups is indicated with 3 or 2 asterisks (denoting statistical significance at the 1 and 5% level, respectively). Due to different numbers of missing observations across the variables considered, the sample sizes vary depending on the characteristic in question (the largest and smallest sizes are reported in the tables).

As Table 2.3 shows, a large number of statistically significant differences were detected, suggesting that those who underwent negative health transitions and those who did not are different when compared across the features explored. For example, those who experienced onset of poor health are less likely to have a job, be male, have children under 16, be mortgaged property-owners and have a degree.

While these findings are consistent across the 5 health constructs explored, other results vary depending on the health measure used. For example, people who experienced an incident health problem are found to be, on average, older than those who did not. However, this finding is reversed when health is measured through mental health or psychological distress. A lower proportion of those who experienced an incident health problem are married or in a civil partnership compared to those who did not. However, a greater proportion were married or in a civil partnership among those who experienced an onset of self-assessed long-standing illness or disability (limiting or non-limiting) or of a chronic condition compared those who did not.

As shown in Table 2.4, the findings for positive health transitions are broadly consistent with those for negative health transitions.

Table 2.3 Characteristics of individuals who experience an onset of poor health (averages across the 7 transition periods)

Self-assessed (general) health:

| Individual characteristic | No onset | Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 74.6 | *** | 63.2 |

| Active (%) | 76.6 | *** | 68.2 |

| Male (%) | 46.2 | *** | 43.2 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 39.4 | *** | 42.3 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 52.5 | *** | 49.1 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 29.6 | *** | 19.2 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 12.1 | *** | 10.9 |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 24.0 | *** | 21.4 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 22.2 | *** | 25.8 |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 6.6 | *** | 10.0 |

| No qualification (%) | 5.6 | *** | 12.6 |

| Region: North East (%) | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| Region: North West (%) | 10.0 | 9.9 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.0 | *** | 8.9 |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.5 | 8.0 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 7.9 | *** | 9.2 |

| Region: East of England (%) | 8.6 | 8.3 | |

| Region: London (%) | 13.4 | 13.6 | |

| Region: South East (%) | 12.3 | *** | 10.9 |

| Region: South West (%) | 7.9 | ** | 7.3 |

| Region: Wales | 6.4 | ** | 6.9 |

| Region: Scotland | 8.4 | *** | 7.3 |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 6.0 | 6.1 | |

| White ethnicity (%) | 82.5 | *** | 79.6 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 37.9 | *** | 36.3 |

| Homeowner (%) | 20.9 | ** | 20 |

| Mortgage (%) | 52.6 | *** | 41.5 |

| Renting (%) | 26.4 | *** | 38.3 |

| Minimum sample size | 151,266 | 11,886 | |

| Maximum sample size | 161,796 | 12,680 |

Mental health or psychological distress:

| Individual characteristic | No onset | Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 75.1 | *** | 68.8 |

| Active (%) | 76.9 | *** | 71.6 |

| Male (%) | 46.4 | *** | 37.9 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 41.4 | *** | 39.8 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 54.8 | *** | 47.8 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 28.6 | 28.5 | |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 12.4 | 12.0 | |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 23.3 | 22.8 | |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 22.4 | 22.5 | |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 7.3 | 7.1 | |

| No qualification (%) | 5.9 | *** | 7.1 |

| Region: North East (%) | 3.8 | 3.9 | |

| Region: North West (%) | 10.1 | ** | 10.7 |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 7.9 | 8.1 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.5 | 7.4 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 7.7 | *** | 8.7 |

| Region: East of England (%) | 8.6 | 8.5 | |

| Region: London (%) | 11.3 | *** | 11.9 |

| Region: South East (%) | 12.3 | 12.5 | |

| Region: South West (%) | 8.4 | 8.3 | |

| Region: Wales | 6.7 | 6.4 | |

| Region: Scotland | 9.2 | *** | 8.2 |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 6.4 | *** | 5.5 |

| White ethnicity (%) | 85.8 | *** | 83.6 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 36.4 | 36.9 | |

| Homeowner (%) | 22.6 | *** | 18.3 |

| Mortgage (%) | 51.7 | *** | 48.9 |

| Renting (%) | 25.6 | *** | 32.7 |

| Minimum sample size | 111,782 | 18,372 | |

| Maximum sample size | 113,111 | 18,602 |

Self-assessed long-standing illness or disability:

| Individual characteristic | No onset | Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 74.0 | *** | 70.9 |

| Active (%) | 76.1 | *** | 74.7 |

| Male (%) | 46.5 | *** | 43.9 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 38.0 | *** | 43.3 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 51.0 | *** | 54.6 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 29.0 | *** | 24.4 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 11.5 | ** | 12.1 |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 24.5 | *** | 21.8 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 22.7 | ** | 23.4 |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 6.4 | *** | 9.0 |

| No qualification (%) | 5.9 | *** | 9.4 |

| Region: North East (%) | 3.5 | ** | 3.9 |

| Region: North West (%) | 9.9 | 9.9 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.2 | 8.3 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.2 | *** | 7.9 |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 8.1 | 8.5 | |

| Region: East of England (%) | 8.5 | 8.6 | |

| Region: London (%) | 15.0 | *** | 13.1 |

| Region: South East (%) | 11.7 | 11.6 | |

| Region: South West (%) | 7.3 | *** | 8.1 |

| Region: Wales | 6.2 | *** | 6.9 |

| Region: Scotland | 8.0 | 8.1 | |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 6.3 | *** | 5.2 |

| White ethnicity (%) | 79.3 | *** | 82.4 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 39.9 | *** | 34.9 |

| Homeowner (%) | 19.2 | *** | 22.8 |

| Mortgage (%) | 52.6 | *** | 46.7 |

| Renting (%) | 28.1 | *** | 30.3 |

| Minimum sample size | 125,126 | 16,717 | |

| Maximum sample size | 134,539 | 17,741 |

Self-assessed long-standing illness or disability (limiting):

| Individual characteristic | No onset | Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 74.4 | *** | 65.6 |

| Active (%) | 76.6 | *** | 70.4 |

| Male (%) | 46.2 | *** | 41.5 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 39.0 | *** | 44.1 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 52.1 | 52.5 | |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 29.2 | *** | 21.5 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 11.8 | 11.9 | |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 24.0 | *** | 20.8 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 22.4 | *** | 24.3 |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 6.6 | *** | 10.1 |

| No qualification (%) | 6.0 | *** | 11.4 |

| Region: North East (%) | 3.6 | 3.9 | |

| Region: North West (%) | 9.9 | 10.1 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.2 | 8.3 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.5 | 7.8 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 8.1 | *** | 8.9 |

| Region: East of England (%) | 8.6 | ** | 8.0 |

| Region: London (%) | 14.3 | *** | 12.2 |

| Region: South East (%) | 11.9 | 11.4 | |

| Region: South West (%) | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Region: Wales | 6.3 | *** | 7.0 |

| Region: Scotland | 8.1 | 8.3 | |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 6.0 | 6.3 | |

| White ethnicity (%) | 80.8 | *** | 82.7 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 38.9 | *** | 33.2 |

| Homeowner (%) | 20.1 | *** | 22.3 |

| Mortgage (%) | 52.3 | *** | 42.6 |

| Renting (%) | 27.5 | *** | 34.9 |

| Minimum sample size | 151,524 | 12,036 | |

| Maximum sample size | 161,278 | 12,361 |

One or more chronic conditions:

| Individual characteristic | No onset | Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 72.2 | *** | 68.7 |

| Active (%) | 74.6 | *** | 72.3 |

| Male (%) | 47.9 | *** | 42.0 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 37.9 | *** | 43.4 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 50.1 | *** | 54.9 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 28.4 | *** | 22.8 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 11.2 | 11.9 | |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 24.4 | *** | 21.3 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 22.8 | *** | 24.4 |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 6.6 | *** | 8.8 |

| No qualification (%) | 6.6 | *** | 10.7 |

| Region: North East (%) | 3.5 | 3.7 | |

| Region: North West (%) | 9.5 | 10.1 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.2 | 8.6 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.4 | 6.8 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 7.9 | 8.0 | |

| Region: East of England (%) | 8.3 | 8.6 | |

| Region: London (%) | 14.2 | *** | 12.9 |

| Region: South East (%) | 11.8 | 11.9 | |

| Region: South West (%) | 7.6 | 7.6 | |

| Region: Wales | 6.6 | 6.7 | |

| Region: Scotland | 8.4 | 8.6 | |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 6.7 | 6.6 | |

| White ethnicity (%) | 80.6 | *** | 82.7 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 39.1 | *** | 35.8 |

| Homeowner (%) | 19.2 | *** | 22.2 |

| Mortgage (%) | 52.1 | *** | 45.4 |

| Renting (%) | 28.6 | *** | 32.2 |

| Minimum sample size | 129,989 | 5,776 | |

| Maximum sample size | 141,879 | 6,193 |

*** and ** denote whether the difference in proportions between the Onset and No onset groups is statistically significant at the 1 and 5% level, respectively. The number of observations varies depending on the variable explored (the minimum and maximum numbers are reported). Source: authors’ calculations based on data from Understanding Society

Table 2.4 Characteristics of individuals who experience an exit from poor health (averages across the 7 transition periods)

Self-assessed (general) health:

| Individual characteristic | No exit | Exit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 37.7 | *** | 61.6 |

| Active (%) | 44.4 | *** | 66.9 |

| Male (%) | 40.4 | *** | 43.3 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 47.7 | *** | 42.1 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 48.2 | 48.3 | |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 13.3 | *** | 19.1 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 9.9 | *** | 11.1 |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 18.5 | *** | 21.6 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 23.1 | *** | 25.5 |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 13.2 | *** | 10.0 |

| No qualification (%) | 22.0 | *** | 12.8 |

| Region: North East (%) | 4.7 | *** | 3.7 |

| Region: North West (%) | 10.9 | 10.3 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.7 | 9.0 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.7 | 8.1 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 9.3 | 9.0 | |

| Region: East of England (%) | 7.4 | *** | 8.4 |

| Region: London (%) | 11.0 | *** | 13.8 |

| Region: South East (%) | 9.9 | ** | 10.6 |

| Region: South West (%) | 7.4 | 7.2 | |

| Region: Wales | 7.1 | 6.6 | |

| Region: Scotland | 8.2 | *** | 7.2 |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 7.6 | *** | 6.1 |

| White ethnicity (%) | 82.7 | *** | 79.2 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 26.2 | *** | 36.2 |

| Homeowner (%) | 20.6 | ** | 19.7 |

| Mortgage (%) | 31.5 | *** | 41.5 |

| Renting (%) | 47.7 | *** | 38.6 |

| Minimum sample size | 21,255 | 11,046 | |

| Maximum sample size | 22,443 | 11,789 |

Mental health or psychological distress:

| Individual characteristic | No exit | Exit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 52.1 | *** | 65.3 |

| Active (%) | 57.3 | *** | 68.9 |

| Male (%) | 33.6 | *** | 37.7 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 41.2 | *** | 40.0 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 41.9 | *** | 47.0 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 22.1 | *** | 28.9 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 11.7 | 12.2 | |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 22.2 | ** | 23.2 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 23.9 | *** | 21.6 |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 9.5 | *** | 7.1 |

| No qualification (%) | 10.6 | *** | 7.0 |

| Region: North East (%) | 4.0 | 3.7 | |

| Region: North West (%) | 11.2 | 10.6 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.5 | 8.2 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.4 | 7.6 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 9.4 | 8.8 | |

| Region: East of England (%) | 7.8 | *** | 8.7 |

| Region: London (%) | 12.0 | 12.2 | |

| Region: South East (%) | 11.5 | ** | 12.4 |

| Region: South West (%) | 7.3 | *** | 8.1 |

| Region: Wales | 7.0 | *** | 6.3 |

| Region: Scotland | 8.3 | 7.9 | |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 5.7 | 5.6 | |

| White ethnicity (%) | 82.7 | ** | 83.5 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 33.6 | *** | 36.8 |

| Homeowner (%) | 16.8 | *** | 18.0 |

| Mortgage (%) | 41.0 | *** | 49.2 |

| Renting (%) | 42.1 | *** | 32.6 |

| Minimum sample size | 19,132 | 18,548 | |

| Maximum sample size | 19,341 | 18,779 |

Self-assessed long-standing illness or disability:

| Individual characteristic | No exit | Exit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 52.1 | *** | 70.3 |

| Active (%) | 56.9 | *** | 73.8 |

| Male (%) | 42.2 | *** | 44.1 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 46.7 | *** | 43.4 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 46.7 | *** | 54.6 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 46.7 | *** | 25.3 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 46.7 | 12.1 | |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 46.7 | *** | 21.7 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 46.7 | 22.9 | |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 46.7 | *** | 8.7 |

| No qualification (%) | 46.7 | *** | 9.2 |

| Region: North East (%) | 46.7 | *** | 3.6 |

| Region: North West (%) | 46.7 | *** | 9.8 |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 46.7 | 8.6 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 46.7 | *** | 7.7 |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 46.7 | 8.2 | |

| Region: East of England (%) | 46.7 | ** | 8.5 |

| Region: London (%) | 46.7 | *** | 12.9 |

| Region: South East (%) | 46.7 | *** | 12.3 |

| Region: South West (%) | 46.7 | 8.0 | |

| Region: Wales | 46.7 | *** | 6.4 |

| Region: Scotland | 46.7 | 8.7 | |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 46.7 | *** | 5.3 |

| White ethnicity (%) | 46.7 | *** | 83.6 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 46.7 | *** | 35.1 |

| Homeowner (%) | 46.7 | 23.0 | |

| Mortgage (%) | 46.7 | *** | 47.2 |

| Renting (%) | 46.7 | *** | 29.6 |

| Minimum sample size | 41,326 | 15,554 | |

| Maximum sample size | 43,416 | 16,415 |

Self-assessed long-standing illness or disability (limiting):

| Individual characteristic | No exit | Exit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 37.6 | *** | 64.2 |

| Active (%) | 43.8 | *** | 68.6 |

| Male (%) | 38.8 | *** | 41.0 |

| Age (mean, in years) | 47.8 | *** | 44.2 |

| Married or in civil partnership (%) | 47.0 | *** | 53.2 |

| Highest qualification: Degree (%) | 14.8 | *** | 21.8 |

| Highest qualification: Other higher (%) | 11.1 | *** | 12.1 |

| Highest qualification: A level (%) | 18.2 | *** | 20.8 |

| Highest qualification: GCSE (%) | 23.2 | 24.0 | |

| Highest qualification: Other lower (%) | 12.9 | *** | 9.9 |

| No qualification (%) | 19.8 | *** | 11.3 |

| Region: North East (%) | 4.6 | *** | 3.7 |

| Region: North West (%) | 10.8 | 10.3 | |

| Region: Yorkshire and the Humber (%) | 8.4 | 8.6 | |

| Region: East Midlands (%) | 7.4 | 7.9 | |

| Region: West Midlands (%) | 8.0 | ** | 8.7 |

| Region: East of England (%) | 7.2 | ** | 7.9 |

| Region: London (%) | 10.7 | 11.3 | |

| Region: South East (%) | 10.3 | *** | 11.9 |

| Region: South West (%) | 8.1 | 7.9 | |

| Region: Wales | 7.3 | 7.0 | |

| Region: Scotland | 9.1 | 8.4 | |

| Region: Northern Ireland | 8.1 | *** | 6.4 |

| White ethnicity (%) | 85.9 | *** | 84.2 |

| Any children under 16 (%) | 24.7 | *** | 33.4 |

| Homeowner (%) | 22.2 | 22.7 | |

| Mortgage (%) | 31.1 | *** | 43.2 |

| Renting (%) | 46.5 | *** | 33.9 |

| Minimum sample size | 22,967 | 11,209 | |

| Maximum sample size | 23,148 | 11,304 |

*** and ** denote whether the difference in proportions between the Exit and No exit groups is statistically significant at the 1 and 5% level, respectively. The number of observations varies depending on the variable explored (the minimum and maximum numbers are reported). Source: authors’ calculations based on data from Understanding Society

2.4. Time of impact, size of impact, sample sizes and rare events

A key question concerns the time between an initial health transition and the subsequent work transition. Understanding when a work transition occurs in relation to a health transition has important implications. For example, it may help understand the potential time frame available for policy makers to intervene to minimise the (negative) employment impact of an incident health problem.

Knowing the magnitude of the impact of health transitions on work transitions, and how many people experience a work transition at each point in time following the initial health shock, are other important aspects that may help inform policy development.

Knowing the observed numbers experiencing work transitions, and the proportions of the at-risk samples that they represent, helps us identify the best approach to statistical analysis. For example, as a work transition following a health transition is a relatively rare phenomenon observed in USoc, some adjustments to our models and estimating specifications are required to attempt to avoid introducing bias to our results.[footnote 20] These aspects were explored empirically in relation to specific work transitions. This section summarises the main findings (details on the analysis are reported in Appendix 1).

While the term ‘impact’ is often used in this section, the figures reported are only indicative of the causal effect of health transitions on work transitions as they are based on simple differences in the proportion experiencing work transitions between those who underwent health transitions and those who did not, without controlling for those baseline differences which section 2.2.3 has shown to be important. Indicative impacts are explored to provide some insights into the most appropriate methodology and data set-up to estimate impacts (more reliable impact estimates, which account for baseline differences, are reported in Chapter 4).

2.4.1. Time and size of the impact

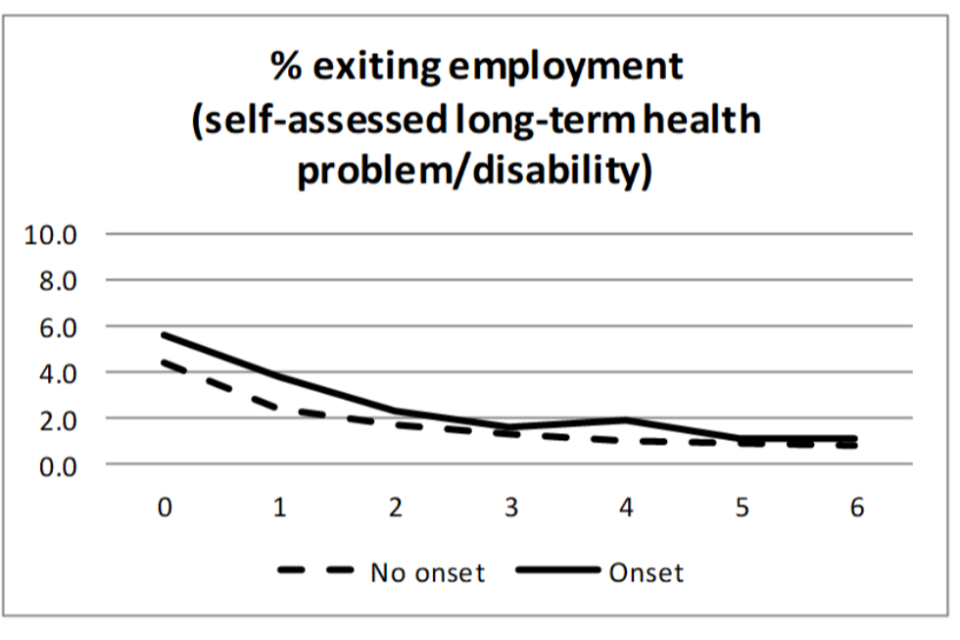

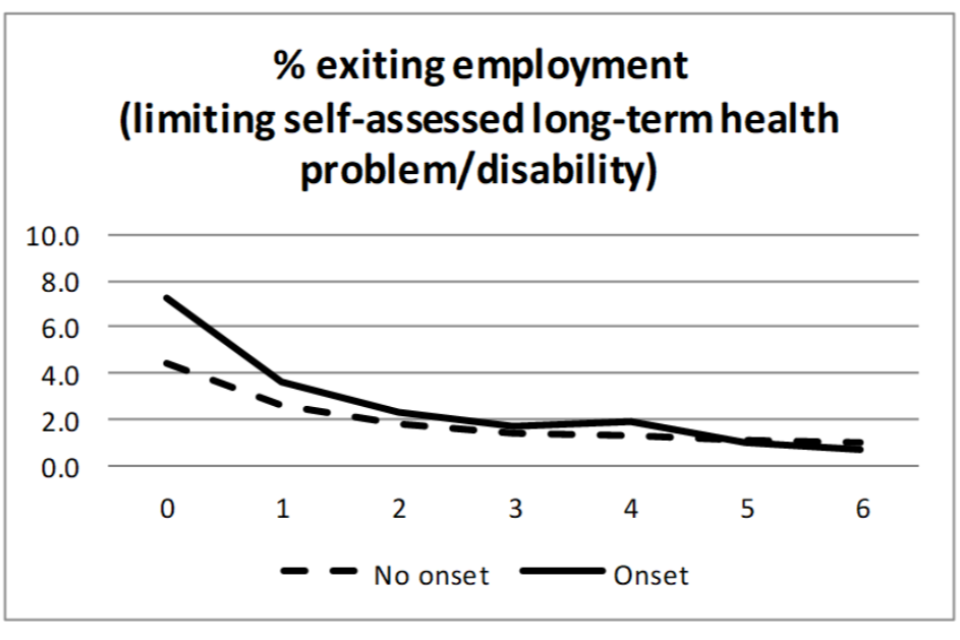

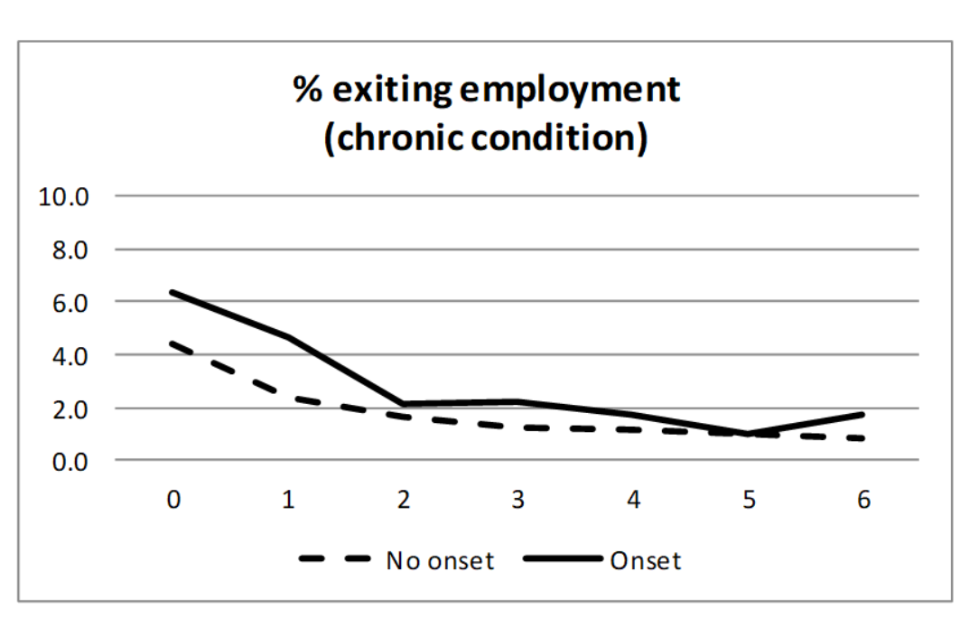

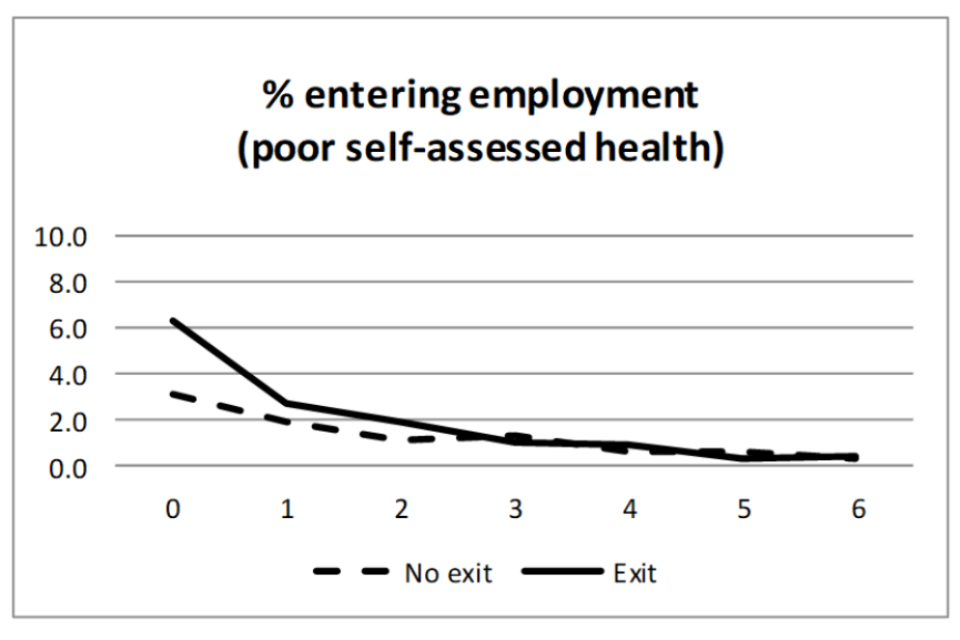

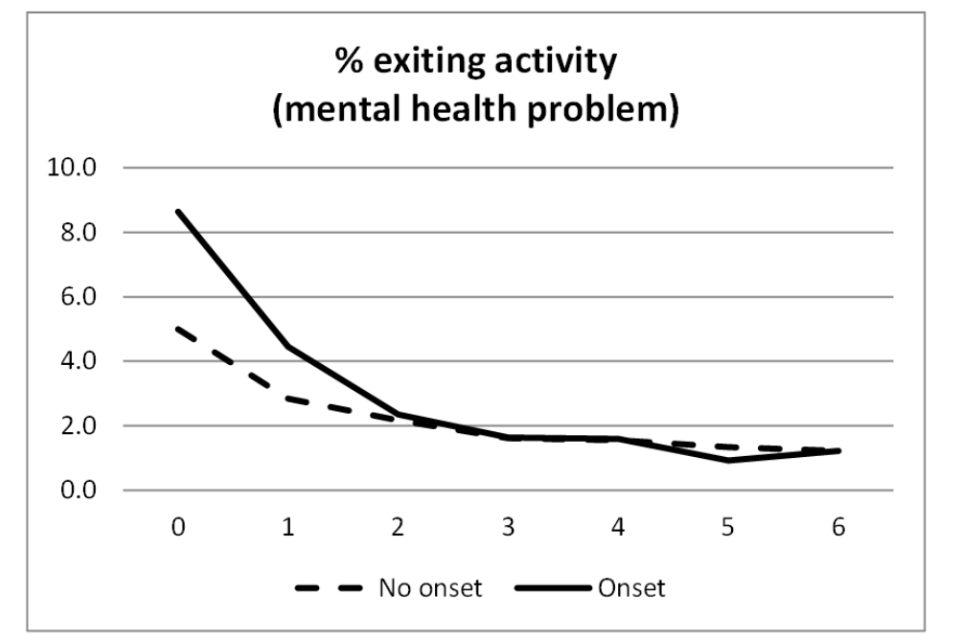

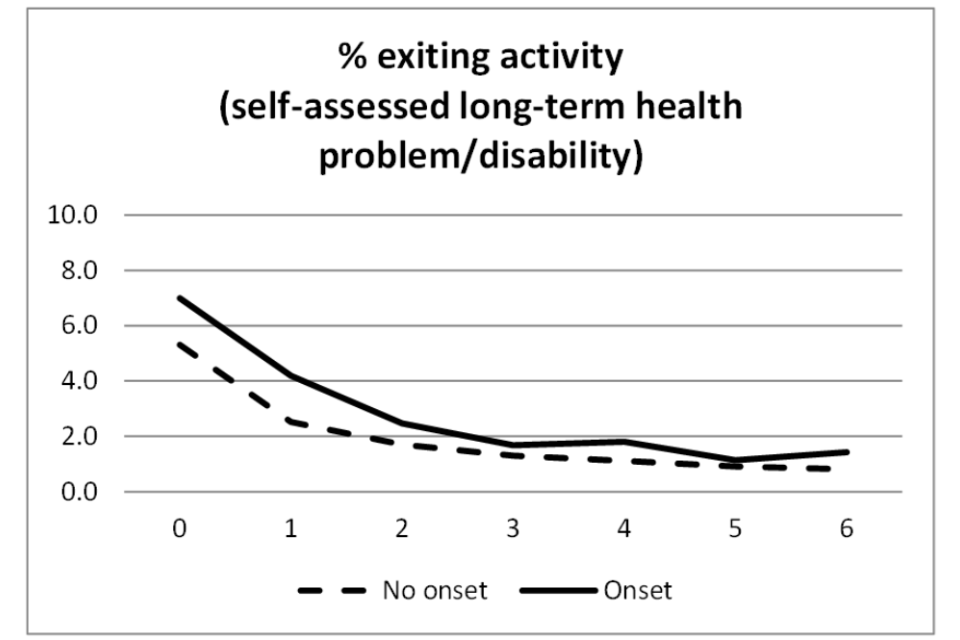

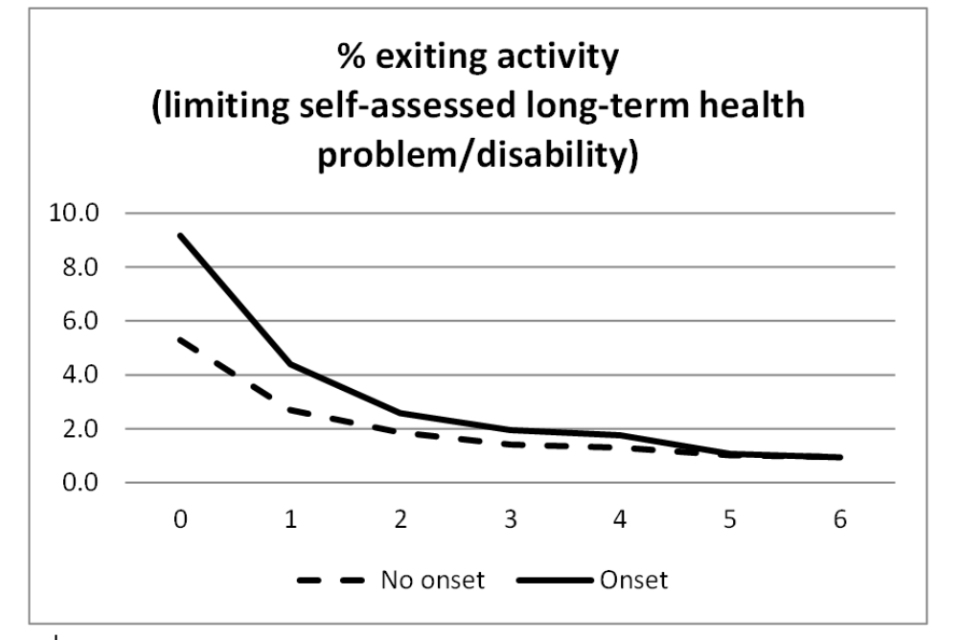

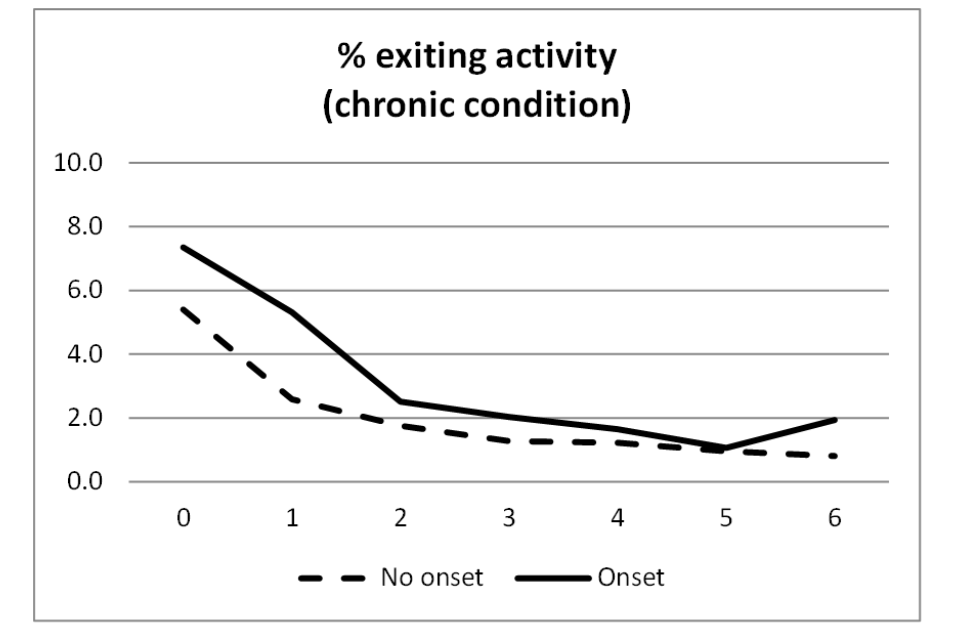

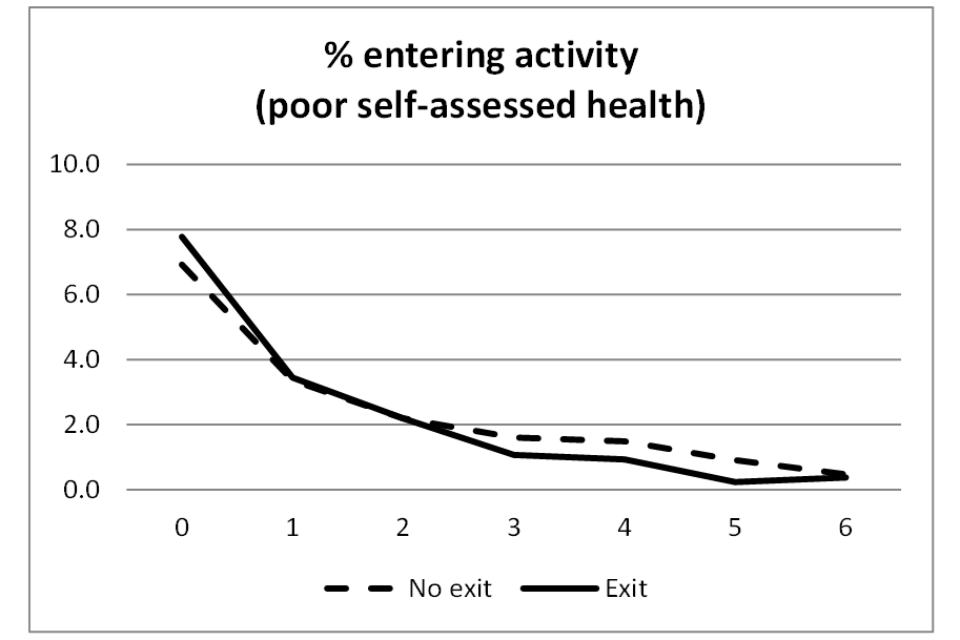

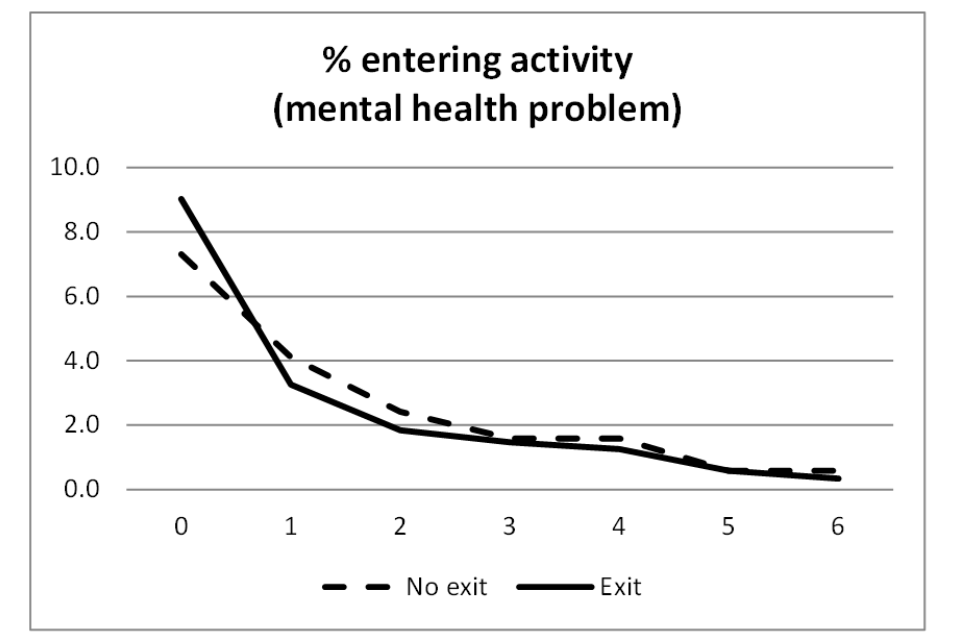

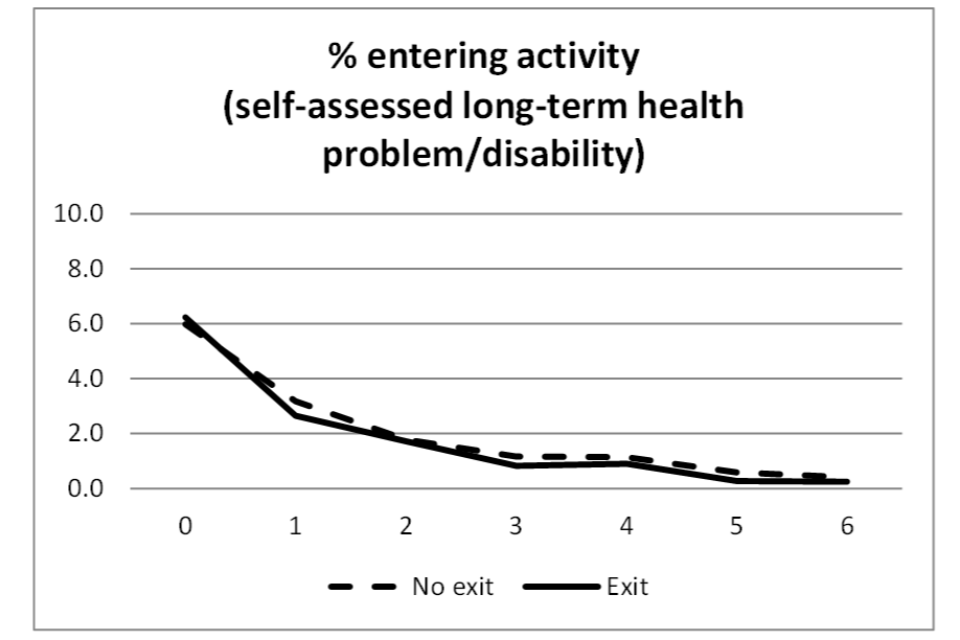

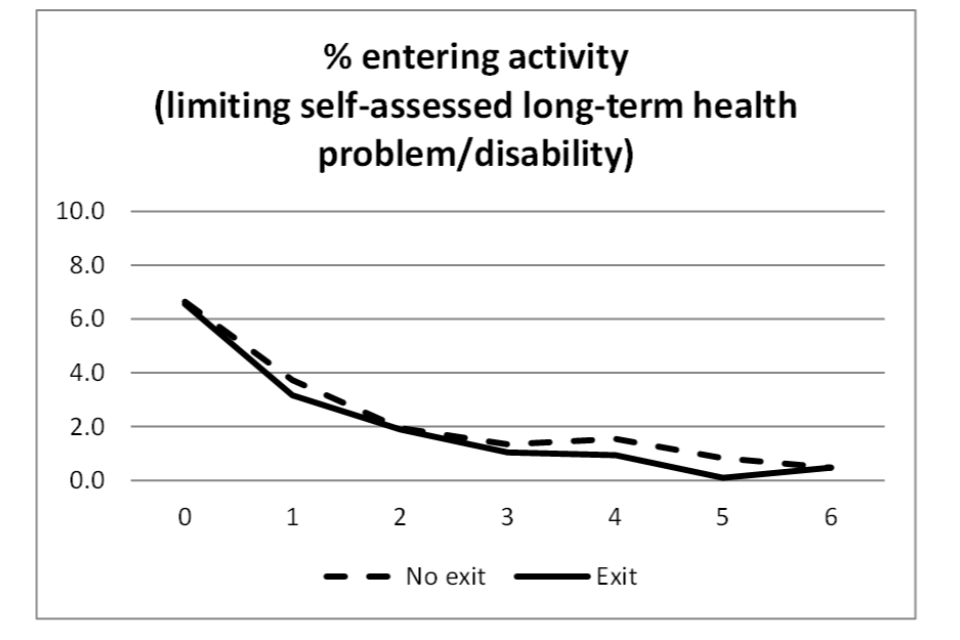

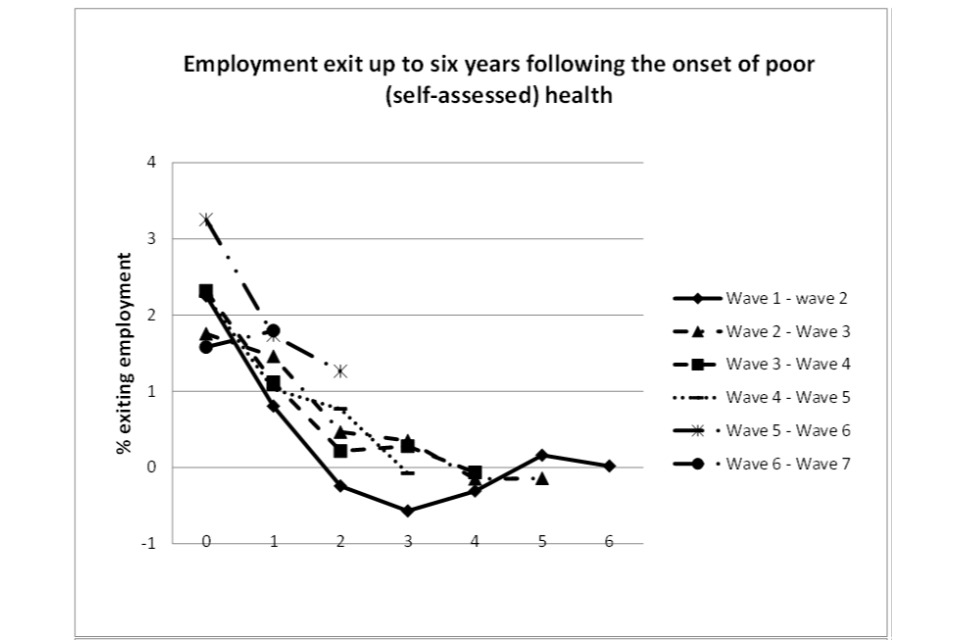

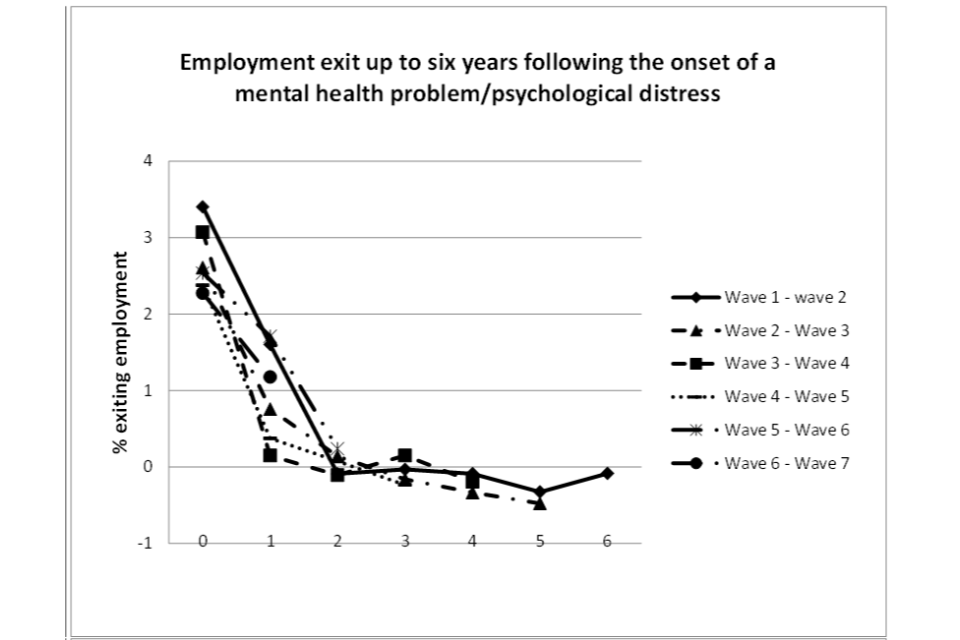

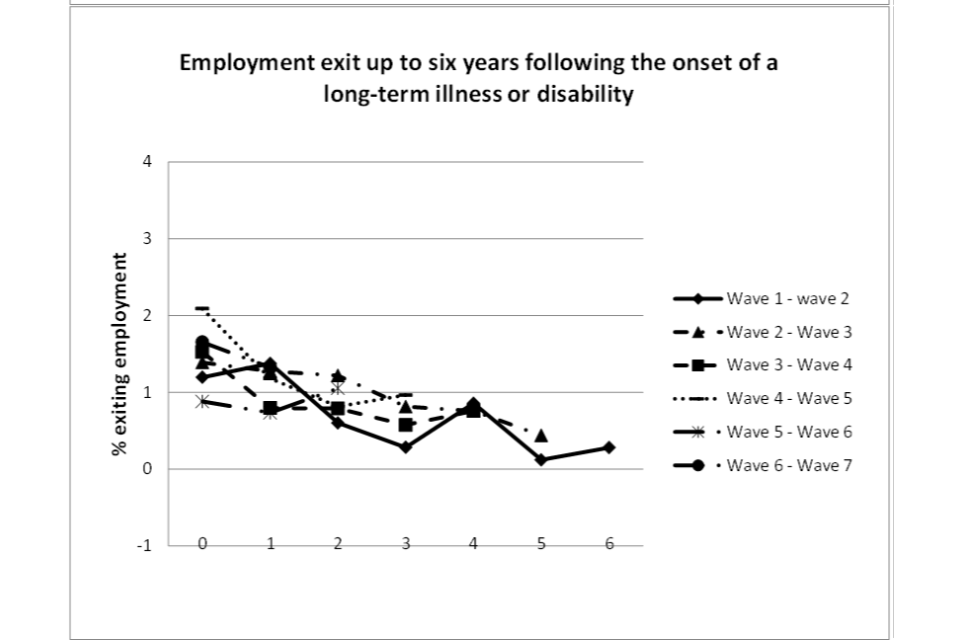

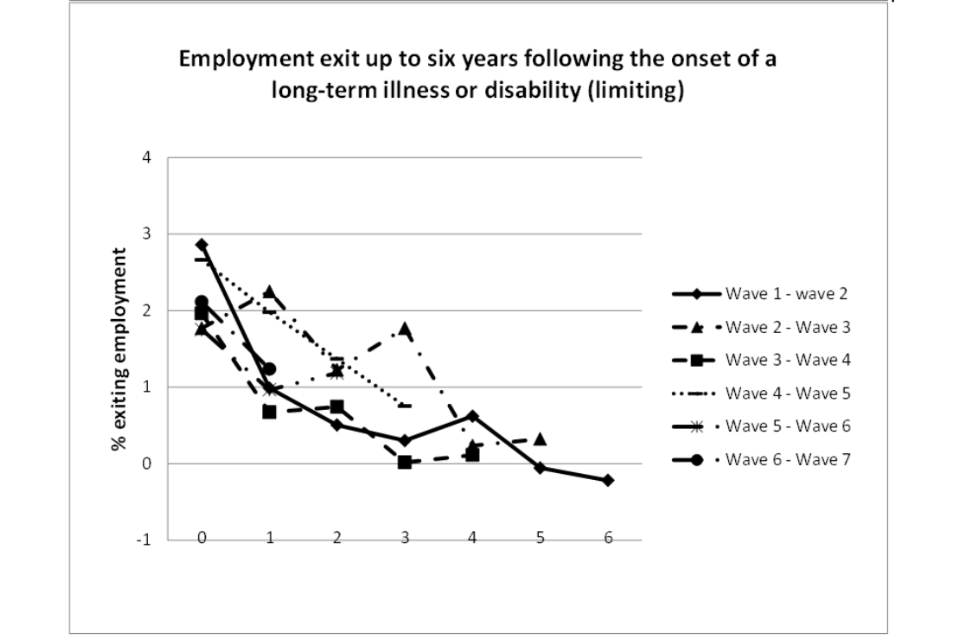

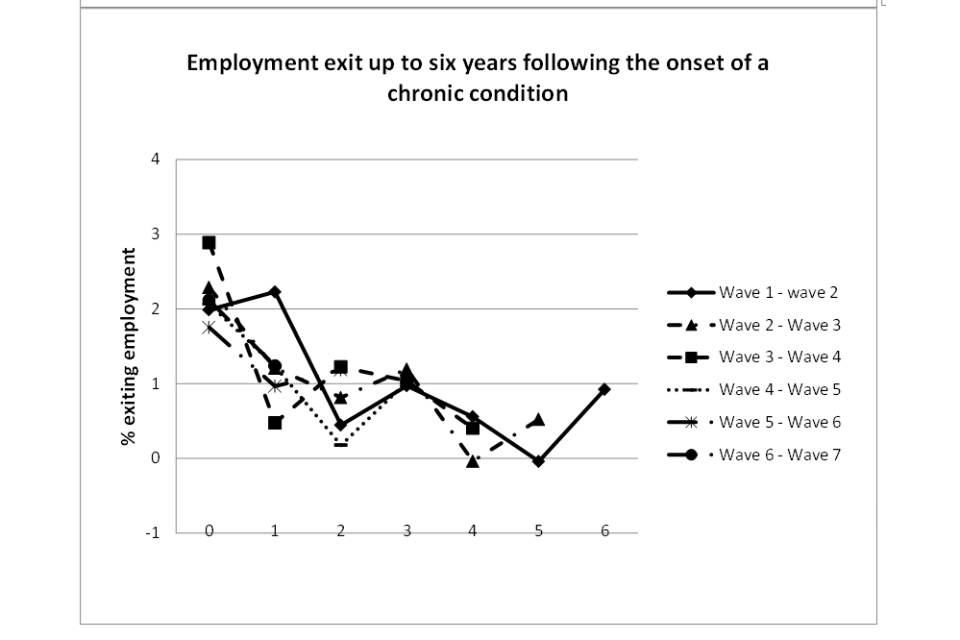

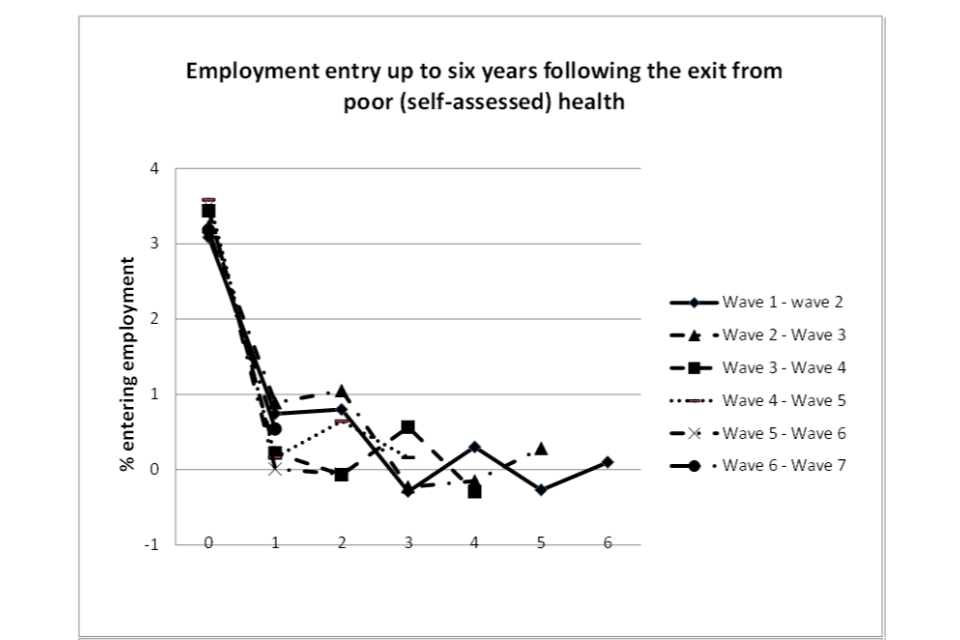

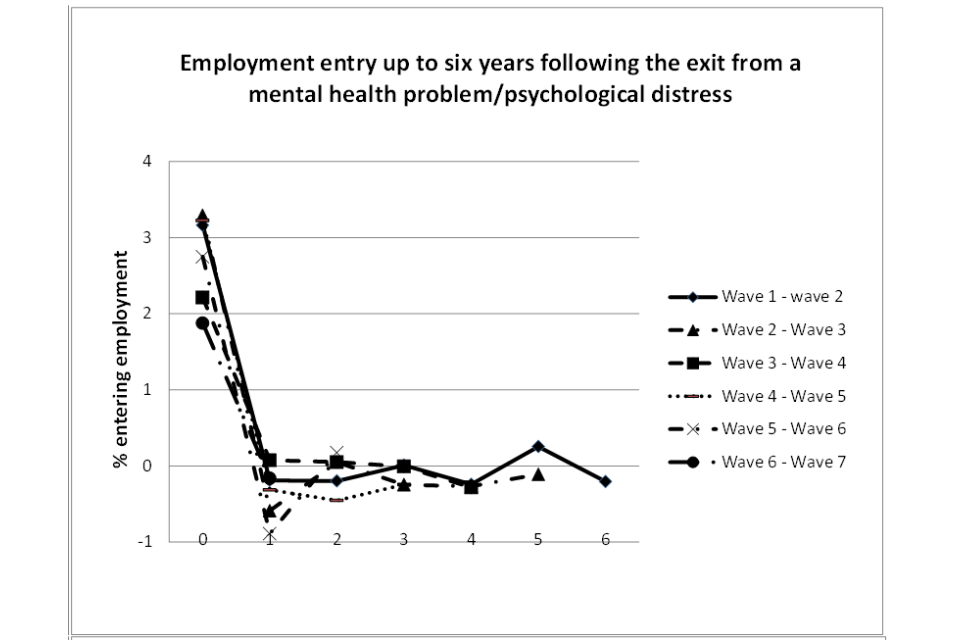

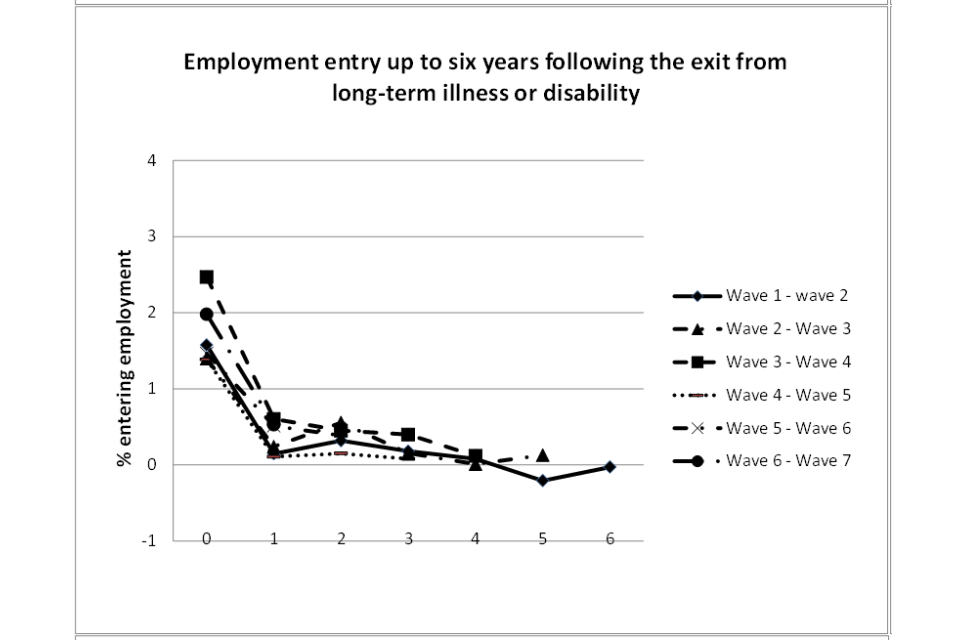

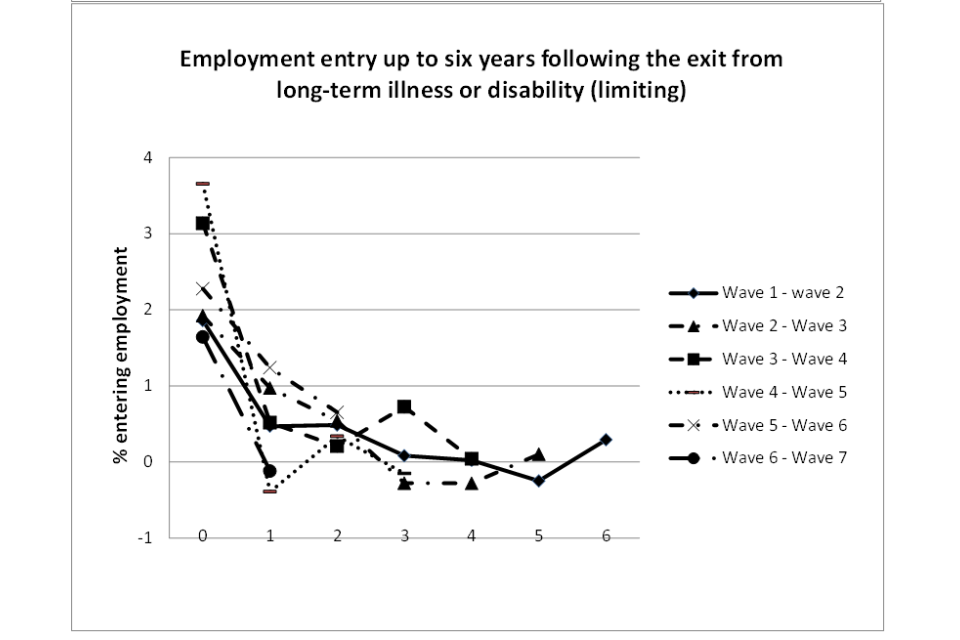

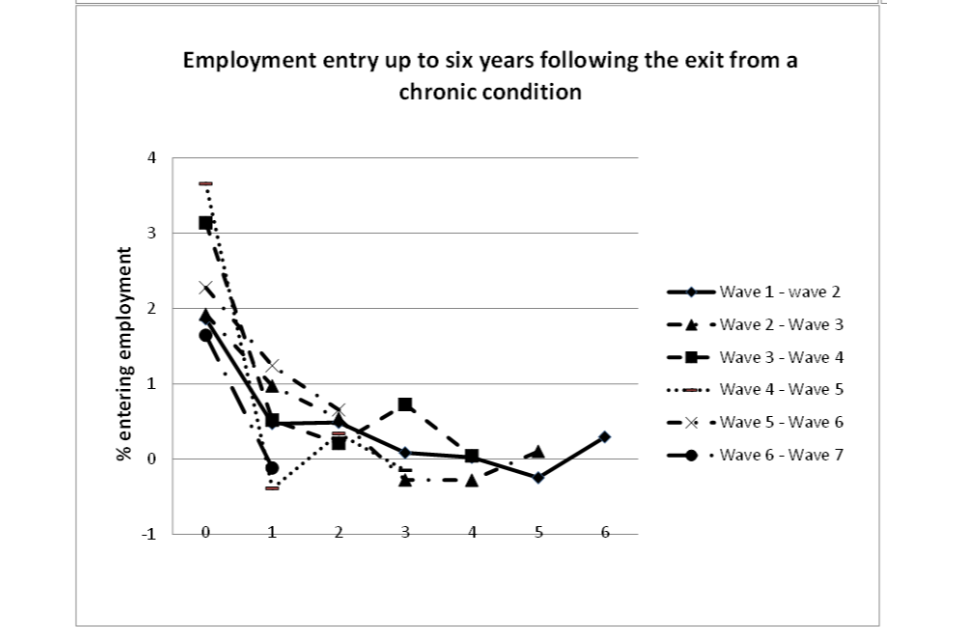

The findings from the preliminary analysis of health and work transitions suggest that:

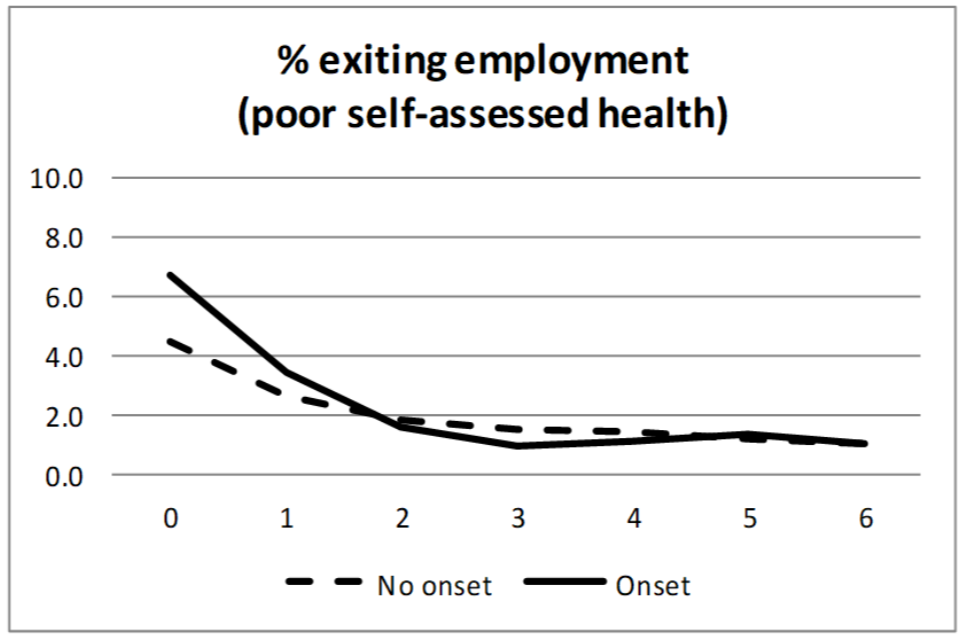

- health transitions have an impact on work transitions - experiencing onset of poor health increases the likelihood of exiting employment (and economic activity), and recovering from poor health improves people’s chances of entering employment (and activity);

- the magnitude of the impact differs across the health constructs explored, and varies considerably depending on which cohort is observed (each cohort is composed of people at risk of making a health transition between 2 consecutive USoc waves);[footnote 21]

- the greatest impact is observed in the same period that individuals experienced the health shock (contemporaneous health and work transitions); and

- the impact progressively reduces to become negligible around 3 years after the initial health transition

Based on these findings, it seems appropriate to assess the magnitude of the impact of health transitions on work transitions considering different cohorts, as the existence of time-specific effects would mean that people undergoing an onset of (or exit from) poor health at different times may experience different impacts. To account for this, a multi-cohort (repeated cross-section) approach can be used (see Chapter 3). Outcomes (work transitions) for the whole cohort (those experiencing a health transition and those considered at risk) should be observed for at least 3 years. Finally, contemporaneous associations between health and work transitions appear to be the largest, and on this basis deserve exploration, notwithstanding the issue of reverse causality described in section 1.3.

2.4.2. Sample size and rare events issues

The preliminary analysis also explored, separately for each cohort, the number of people for whom a negative or positive work transition is observed at each point in time after being considered at risk of experiencing a health transition. As shown in Table 2.5 (first row, first column), 1,156 people were found to have exited employment at time 0 (between Wave 1 and Wave 2). These people represent 4.6% of the sample of those at risk of making a negative health transition in the same period (25,077 people). The number (and proportion) who experienced an exit from employment among those at risk of making a negative health transition decreases at later time points (only 380 individuals, making up 1.5% of the at-risk sample, exited employment at time 3). As we can see from Table 2.6, both sample sizes and frequencies of work transitions are smaller when positive (rather negative) health-work transitions are considered. Pooling together different health transition cohorts (an approach aimed at controlling for possible time-specific effects in the estimation of associations, as previously explained) also addresses the potential estimation bias generated by rare events as well as boosting sample sizes.

Table 2.5 Employment exit among those at risk of experiencing onset of poor health between Waves 1 and 2 (numbers and proportion of total sample at risk)

Poor self-assessed health:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,156 | 4.6 |

| 1 | 682 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 463 | 1.8 |

| 3 | 380 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 348 | 1.4 |

| 5 | 296 | 1.2 |

| 6 | 257 | 1.0 |

| Sample size | 25,077 | 100.0 |

Mental health or psychological distress:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 772 | 4.6 |

| 1 | 510 | 3.0 |

| 2 | 352 | 2.1 |

| 3 | 280 | 1.7 |

| 4 | 253 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 224 | 1.3 |

| 6 | 203 | 1.2 |

| Sample size | 16,831 | 100.0 |

Long-standing illness or disability:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 955 | 4.5 |

| 1 | 540 | 2.6 |

| 2 | 375 | 1.8 |

| 3 | 284 | 1.3 |

| 4 | 247 | 1.2 |

| 5 | 208 | 1.0 |

| 6 | 187 | 0.9 |

| Sample size | 21,161 | 100.0 |

Long-standing illness or disability (limiting):

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,117 | 4.6 |

| 1 | 644 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 449 | 1.9 |

| 3 | 358 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 316 | 1.3 |

| 5 | 256 | 1.1 |

| 6 | 232 | 1.0 |

| Sample size | 24,242 | 100.0 |

One or more chronic conditions:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 967 | 4.5 |

| 1 | 543 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 367 | 1.7 |

| 3 | 280 | 1.3 |

| 4 | 261 | 1.2 |

| 5 | 217 | 1.0 |

| 6 | 186 | 0.9 |

| Sample size | 21,542 | 100.0 |

Source: authors’ calculations based on data from Understanding Society

Table 2.6 Employment entry among those at risk of experiencing exit from poor health between Waves 1 and 2 (numbers and proportion of total sample at risk)

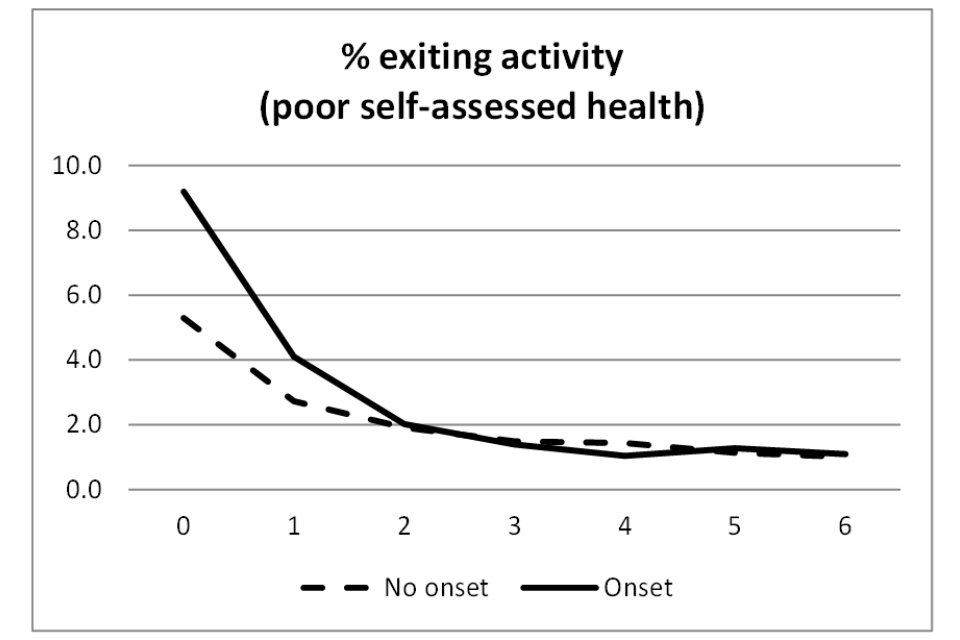

Poor self-assessed health:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 242 | 4.3 |

| 1 | 125 | 2.2 |

| 2 | 79 | 1.4 |

| 3 | 67 | 1.2 |

| 4 | 39 | 0.7 |

| 5 | 30 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 20 | 0.4 |

| Sample size | 5,569 | 100.0 |

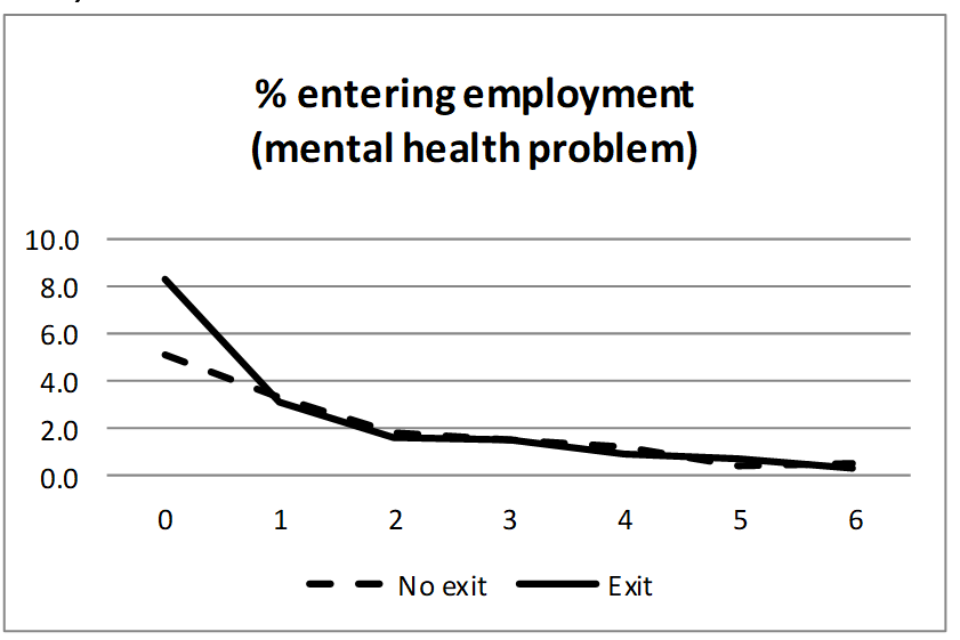

Mental health or psychological distress:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 321 | 6.7 |

| 1 | 155 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 81 | 1.7 |

| 3 | 74 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 52 | 1.1 |

| 5 | 28 | 0.6 |

| 6 | 19 | 0.4 |

| Sample size | 4,800 | 100.0 |

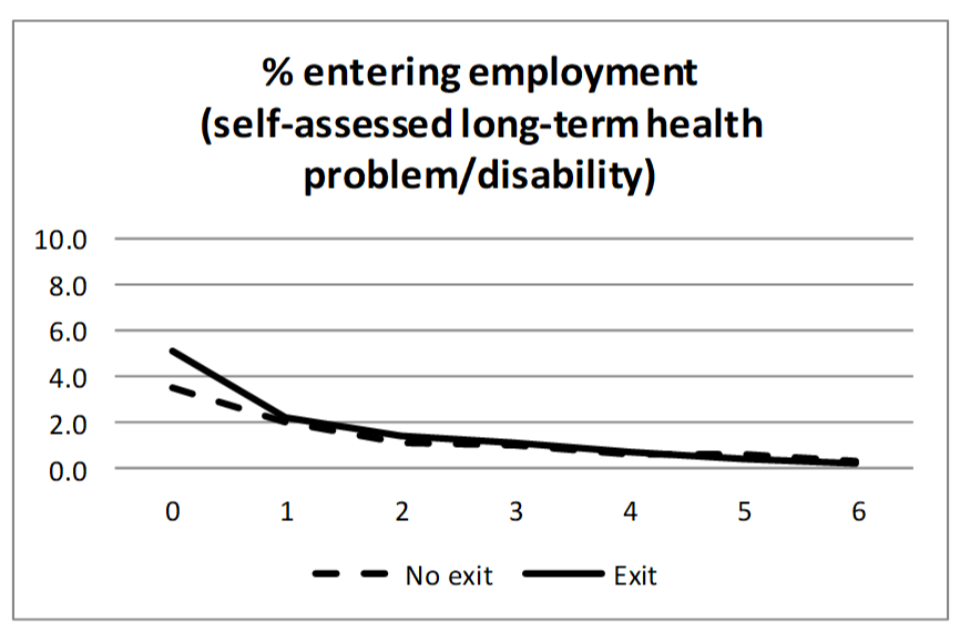

Long-standing illness or disability:

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 379 | 4.0 |

| 1 | 199 | 2.1 |

| 2 | 116 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 99 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 60 | 0.6 |

| 5 | 56 | 0.6 |

| 6 | 28 | 0.3 |

| Sample size | 9,466 | 100.0 |

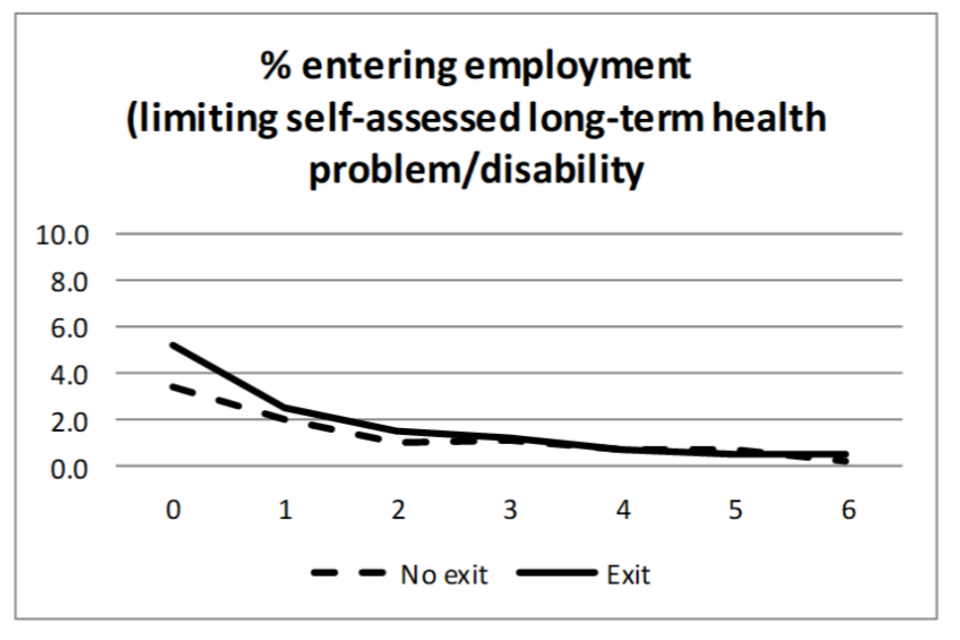

Long-standing illness or disability (limiting):

| Time | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 234 | 4.1 |

| 1 | 127 | 2.2 |

| 2 | 72 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 65 | 1.1 |

| 4 | 40 | 0.7 |

| 5 | 39 | 0.7 |

| 6 | 22 | 0.4 |

| Sample size | 5,767 | 100.0 |

Source: authors’ calculations based on data from Understanding Society

3. Research methods