Annex A: Background document to support the action plan towards ending HIV transmission, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in England

Updated 21 December 2021

Applies to England

1. Introduction to background document

1.1 HIV in England

We provide an overview of the epidemiology of HIV infection in England to December 2019. We have used this year as a baseline for the Action Plan and because 2020 data are affected by changes in health service access and delivery due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.1.1 Undiagnosed HIV infection

If untreated, the time from HIV infection to AIDS and death is a decade on average (15 in references). While preventing morbidity and mortality through accessing HIV testing and care is the primary goal, reducing the number of people unaware of their HIV infection is also important to prevent onward transmission. Unless people with an undiagnosed HIV infection are in sexual partnerships that involve condoms (16 to 19) or PrEP (20) the virus may be passed on.

Estimates of undiagnosed HIV infection are produced using a multi-parameter evidence synthesis (MPES) (4) that combines surveillance data with survey information of population group size. Among gay and bisexual men, a CD4 back calculation model can be used to estimate undiagnosed HIV infection and HIV incidence (3).

In England, an estimated 96,200 (95% credible interval (CrI) 94,400 to 99,000) people were estimated to be living with HIV including 5,900 (95% CrI 4,400 to 8,700) with an undiagnosed HIV infection, equivalent to 6% (95% CrI 5% to 9%) of the total(2). The number of people estimated to be living with an undiagnosed HIV infection fell from 6,700 in 2018. Nearly twice as many people with undiagnosed HIV infection in England lived outside of London (3,800 (95% CrI 2,600 to 6,200) compared to 2,100 (95% CrI 1,500 to 3,100) in London)(2).

The estimated number of gay and bisexual men living with undiagnosed HIV infection seemed to fall from 3,600 (CrI 2,000 to 6,700) in 2018 to 2,900 (CrI1,600 to 5,300) in 2019, while 95% credible intervals substantially overlap. These figures are consistent with a modelled estimate using the CD4 back calculation for gay and bisexual men of 2,860 (Crl 1,460 to 6,040) in 2019. The estimated number of heterosexuals living with undiagnosed infection in the UK remained similar with 3,200 (Crl 2,400 to 5,200) in 2018 to 3,100 (CrI 2,400 to 4,800) in 2019.

1.1.2 New HIV diagnoses and incidence

Since people can live with HIV for many years without being aware of the virus, it is difficult to measure transmission of HIV. New HIV diagnoses can give an indication of underlying HIV transmission. However, trends in HIV diagnoses are affected by HIV testing patterns, reporting delay, reporting ease in addition to HIV incidence. In addition, some countries, including the UK, many people may be diagnosed with HIV before arriving in the country, which means HIV was likely acquired abroad. While we can estimate HIV incidence through models(3), in England this is only available for gay and bisexual men because the large majority of gay and bisexual men acquire HIV within the UK, whereas place of acquisition of HIV among other routes of transmission are more difficult to understand.

Given these caveats, we use new HIV diagnoses made in the UK for the first time, in a context of high and increasing numbers of HIV testing, as a proxy for HIV transmission in England. These are interpreted alongside modelled incidence estimates.

England

The number of people newly diagnosed with HIV decreased to 3,770 (2,720 males and 1,050 females) in 2019, a 9% fall from 4,130 in 2018 (Figure A) and a 35% fall from 5800 in 2014. Of the 3,770 new HIV diagnoses in England in 2019, 910 (24%) were previously diagnosed abroad(2).

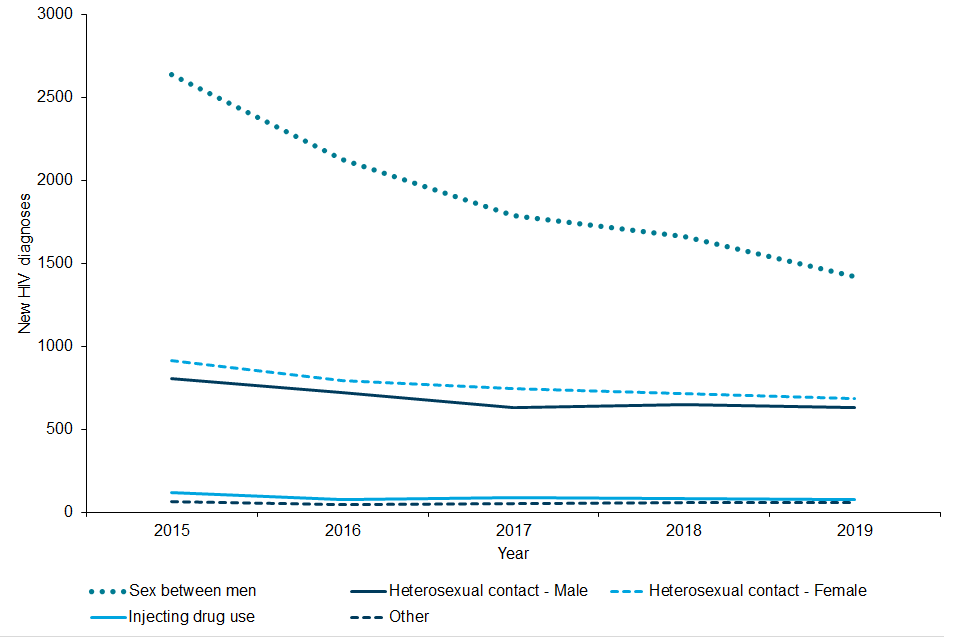

Figure A: new HIV diagnoses first made in England by probable exposure route, England, 2015 to 2019

Figure A is a line graph showing new HIV diagnoses among people living in England (persons first diagnosed in the UK) by probable exposure route, 2015 to 2019. The graph shows a decreasing trend in new HIV diagnoses over time for sex between men, and to a lesser extent among heterosexual adults. ‘Other’ and ‘Injecting drug use’ both show low levels of new HIV diagnoses.

Gay and bisexual and other men who have sex with men

The recent decline in new HIV diagnoses has largely been driven by gay and bisexual men who constituted approximately 41% of all diagnoses first diagnosed in England in 2019. In this group, new HIV diagnoses fell from a peak of 2,770 in 2014 and 1,400 in 2018 to 1,160 diagnosed in 2019 (a 58% and 17% drop respectively). This is the lowest number of new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men since the year 2000 (1,390).

The steepest declines (for diagnoses first diagnosed in England) were observed among white gay and bisexual men (2,170 in 2014, 1,010 in 2018 and 780 in 2019), born in the UK (1,640 in 2014, 790 in 2018 and 610 in 2019), aged 15 to 24 (390 in 2014, 210 in 2018 and 160 in 2019) and resident in London (1,450 in 2014, 550 in 2018 and 470 in 2019).

For gay and bisexual men, incidence trends estimated using a CD4 back-calculation model(3) suggest a sustained decline since 2011, preceding the steep fall in new HIV diagnoses. During this period, the estimated number of incident infections in gay and bisexual men in England declined by 80%, from an estimated peak of 2,700 (95% Crl 2,520 to 2,850) in 2011, to an estimated 540 (95% Crl 180 to 1,810) in 2019.

Figure B: new HIV diagnoses among gay and bisexual men first diagnosed in England by region of residence, age group, ethnicity and country of birth, England, 2015 to 2020

Figure B comprises 4 line graphs showing new HIV diagnoses among gay and bisexual men first diagnosed in England by region of residence, age group, ethnicity and country of birth, 2015 to 2019. Graph a shows that new HIV diagnoses are decreasing both within London and outside London, but to a greater extent in London. Graph b shows that new HIV diagnoses are decreasing most steeply in those aged under 50 years. Graph c shows that new HIV diagnoses have decreased at the fastest rate among white gay and bisexual men with much shallower reductions also seen across those of ‘Asian/other,’ black African and black Caribbean ethnicity. Graph d shows HIV diagnoses have decreased over time for those born in the UK.

Heterosexual men and women

Among heterosexual men and women who were first diagnosed in England, the number of new diagnoses fell from 1620 in 2015 to 1,160 in 2019 (760 to 570 among men and 860 to 600 among women)(2).

Probable country of infection can be estimated by applying CD4 counts at diagnosis to modelled slopes of CD4 decline (within a separate seroconverter dataset) to estimate time of infection for an individual. The estimated time of infection is combined with information on country of birth and year of arrival to estimate country of residence at the time of infection(21). Among heterosexuals born abroad, it was estimated that 460 (uncertainty range 380-550) diagnoses made in 2015 related to infections acquired in the UK falling to 310 (240 to 340) in 2019. The model also estimated a decline of infection acquired before UK arrival from 300 (uncertainty range: 230 to 400) to 220 (uncertainty range: 180 to 280).

Among heterosexual men and women born in the UK, diagnoses from infections acquired abroad remained low and stable, with a modest decline from 380 in 2015 to 310 in 2019 for UK-acquired infections.

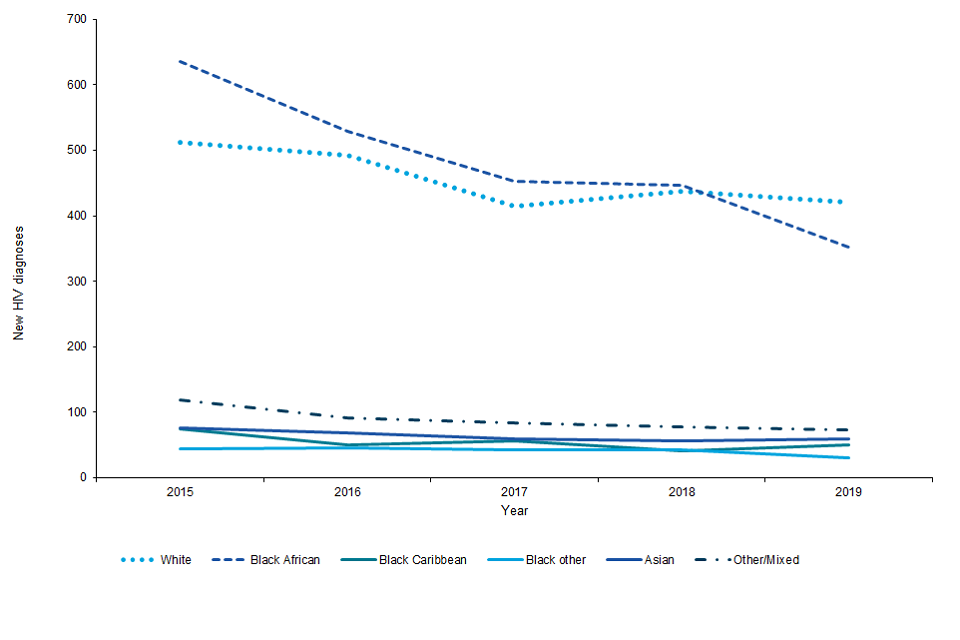

Among heterosexuals first diagnosed in England decreases were observed among black other groups (from 40 in 2018 to 30 in 2019), black African groups (from 450 to 350), other/mixed groups (from 80 to 70) and white ethnic group (440 to 420). However, there was a slight rise among black Caribbean (40 to 50) and Asian ethnic groups (55 to 60) (Figure C).

Figure C: new HIV diagnoses among heterosexuals first made in England by ethnicity, England, 2015 to 2019

Figure C is a line graph showing new HIV diagnoses among heterosexual adults first diagnosed in England by ethnicity 2015 to 2019. The graph shows that a slight decreasing trend in new HIV diagnoses over time that is steepest for black African and white people compared to people of other/mixed, Asian, and black Caribbean ethnicity.

Other populations

Among people who probably acquired HIV through injecting drug use, new HIV diagnoses remain stable and low at around 100 per year. Other transmission routes remain rare in the UK. Of the 60 people diagnosed in 2019 who acquired HIV through vertical transmission, 5 aged under 15 years were born in the UK(2).

1.1.3 Late diagnoses, AIDS and deaths

Late diagnosis (diagnosis with a CD4 count under 350 within 3 months) is the most important predictor of morbidity and premature mortality among people with HIV infection. The number of diagnoses made in England at a late stage of infection reduced from 1,700 in 2015 to 1,160 in 2019. In 2019, 41% of HIV diagnoses were made at a late stage of infection. Older people (63% in those over 65 years vs 32% in those aged 15 to 24), black Africans (60% vs 45% in white) were more likely to be diagnosed late(2).

The total number of people with AIDS at HIV diagnosis[footnote 1] decreased in England from 290 in 2015 to 220 in 2019 (160 males and 60 females).

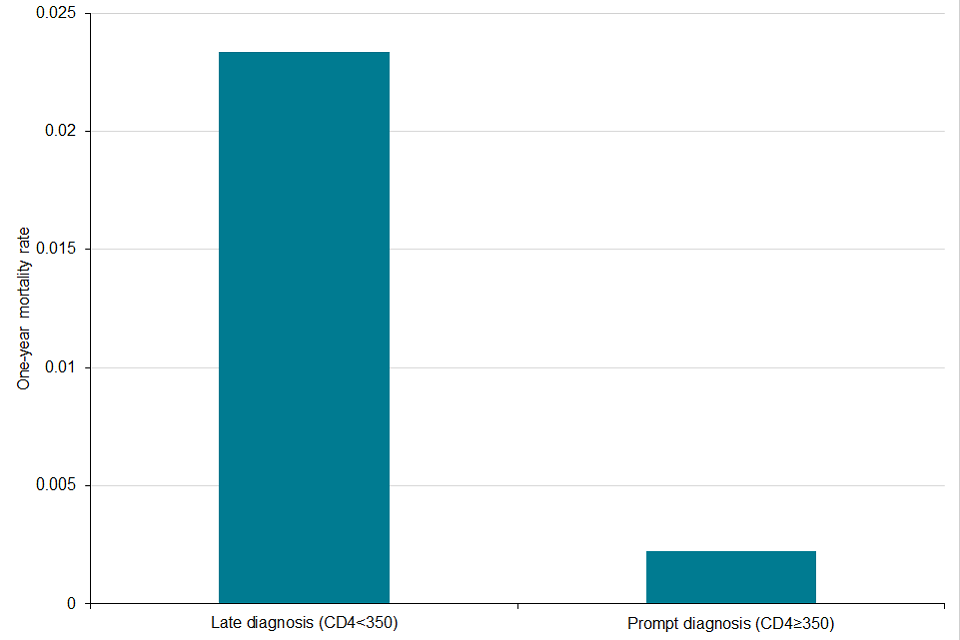

Among people with diagnosed HIV infection in England, 560 died in 2019. This rise, from previous years (520 in 2018 and 470 in 2017) was due to a change in methodology. Of those, 340 died within 12 months of an AIDS-defining illness and/or CD4 cell count under 350 and 30 within 12 months of a late diagnosis. People diagnosed late in 2018 had a one year mortality rate of 23/1,000 (95% confidence interval (CI) 16/1,000 to 33/1,000) compared to 2/1,000 (95% CI 1/1000 to 6/1,000) among those diagnosed promptly, a tenfold increased risk of death(2) (Figure D). It is estimated that around 40-50% of all deaths among people with HIV are HIV-related(7).

Figure D: death within a year of HIV diagnosis among people first diagnosed in England in 2018 by timeliness of diagnosis, England, 2019

Figure D is a bar chart showing death within a year of HIV diagnosis among people first diagnosed in England by timeliness of diagnosis, persons diagnosed in 2018. The chart shows that one year mortality rate for those with a late HIV diagnosis (CD4<350) is 8-fold greater than those with a prompt diagnosis (CD4 ≥350).

1.1.4 Optimising U=U

Increasing the number of people living with HIV infection with undetectable viral load is not only of clinical benefit but essential to reduce ongoing HIV transmission. It is now well established that people who receive treatment and have an undetectable viral load cannot pass on HIV infection to others during sex (including without condoms and PrEP) (22), (23), (^24). However, people cannot benefit from having undetectable levels of virus until we can diagnose those living unaware of HIV infection, and ensure those diagnosed are referred, retained in care with access to rapid ART and support to attain viral load.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 targets have been met with an estimated 94% of people living with HIV diagnosed, 98% of those diagnosed being on treatment and 97% of those on treatment having an undetectable viral load. This is equivalent to an estimated 89% of all those living with HIV being virally undetectable, above the international target of 73%.

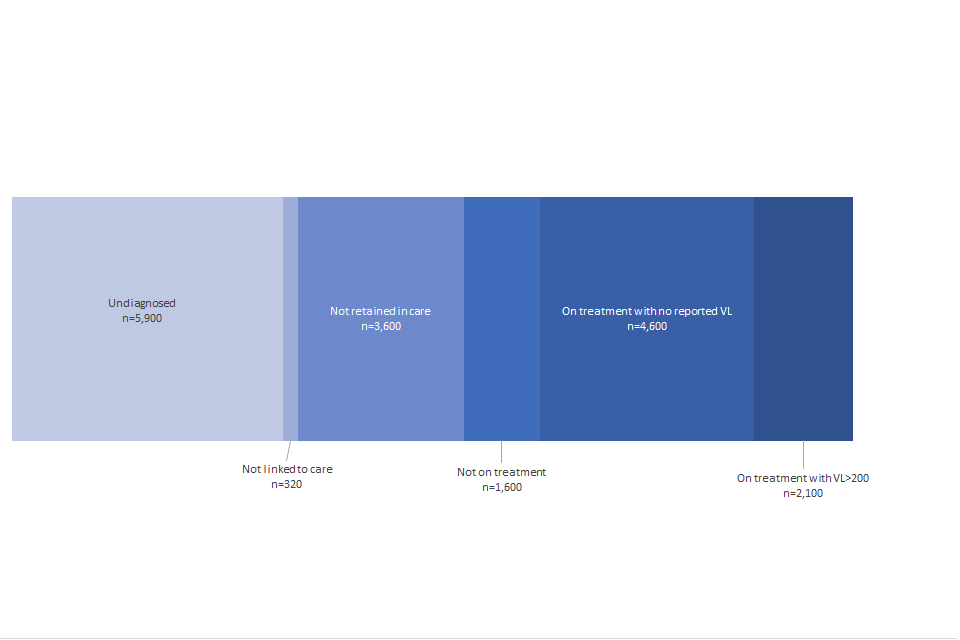

However, the UNAIDS approach does not consider people who have not been referred to care, retained in care and people for whom viral load information is missing. In England, using this approach, 11% (10,580) of people had transmissible levels of virus, the converse of the substantive 89% UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets for 2019. In 2019, UKHSA undertook further analyses to incorporate people with diagnosed HIV who were not in care and/or with missing information; these showed that up to 18,160 people were living with transmissible levels of virus, still above the substantive UNAIDS 90-90-90 target of 73%.

Of these 18,160 people living with transmissible levels of virus, an estimated 5,930 (CrI 4,430 to 8,710) (33%) were undiagnosed, 3,890 (21%) were diagnosed but not referred to specialist HIV care or retained in care, 1,630 (9%) attended for care but were not receiving treatment, and 2,110 people (12%) were on treatment but not virally supressed. The remaining 4,600 (25%) had attended for care but were missing evidence of viral suppression.

2. Access and uptake of HIV prevention programmes

2.1 Key points

-

Public knowledge of HIV infection can be improved. HIV prevention programmes delivered through social marketing campaigns have proved to be a cost-effective, scalable and impactful tool for normalising and providing information on HIV to at risk communities

-

Condoms are an effective way of preventing not only HIV but other STIs and pregnancy. Barriers include negotiation, loss of pleasure and embarrassment; evidence suggests postal condoms may be more easily accessible than face to face access

-

PrEP is extremely effective at preventing HIV transmission and to date almost £33 million has been invested in the provision of PrEP. However, over 95% of those using PrEP are gay and bisexual men; other groups who may benefit from it do not have equal access

2.2 Background

HIV prevention programmes have been key in ensuring people are aware of how HIV is transmitted, how to protect yourself, how to have an HIV test and the developments in HIV treatment. While condoms prevent HIV, other STIs and unwanted pregnancies, PrEP extremely effective at preventing HIV transmission and is routinely commissioned in specialist sexual health services and postal services.

Nonetheless the evidence suggests that awareness, accessibility, availability and uptake of primary prevention initiatives is variable in different demographics and addressing this disparity is key to HIV prevention.

2.3 Knowledge on how to prevent HIV infection

The 2021 report ‘HIV: Public Knowledge and Attitudes’ from the National Aids Trust (9) found almost two thirds (63%) of the public could not recall seeing or hearing about HIV in the last 6 months. While high majorities of the public could correctly identify the 3 main ways that HIV could be transmitted, many believed that HIV could be passed on through ‘no risk’ modes.

The report found that the opportunity to increase knowledge of a range of HIV prevention interventions, for example those with lower knowledge of transmission are less likely to think they can get an HIV test at a sexual health or general practice clinic than those with higher levels of knowledge. Additionally, only a quarter of participants believed there is medicine available that will stop someone acquiring HIV.

The report found scepticism towards U=U and the efficacy of PrEP, with many reverting to a belief that there is ‘no such thing’ as zero risk.

Several opportunities to share information and empower through knowledge exist throughout the life course and include (but are not limited to):

- Relationships, Sex and Health Education (RSHE) - A review of school based interventions to improve sexual health found that found that school-based interventions, specifically those targeting risky sexual behaviour and HIV prevention were effective in improving knowledge and changing attitudes, behaviours and health outcomes (25)

- peer interventions – well evidenced in both HIV care and other chronic conditions (for example hepatitis C, diabetes), peer interventions are found to be effective in promoting HIV testing, condom use and reducing condomless sex among a number of different audiences (26)

- trusted sources of information – respondents to the 2021 survey HIV: Public Knowledge and Attitudes (9) felt that General Practitioners, the NHS website, sexual health charities were the most trusted sources of information on HIV, and were seen as ‘official’ sources of medical information

2.4 HIV prevention programmes

HIV prevention programmes delivered through social marketing campaigns have proved to be a cost-effective, scalable and impactful tool for normalising and providing information on HIV to at risk communities (27). Evaluations of the National HIV Prevention Programme, as well as the recent findings of the Health Protection Report Unit report ‘Promoting the sexual health and wellbeing of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’ (18) suggest that social marketing and engagement through social media, apps, digital and print media is considered feasible and acceptable to a variety of audiences.

Evidence shows campaigns can be most effective when delivered intensively – HIV prevention strategies have been shown to have larger effects at extended periods (1 to 3 years) compared with briefer interventions (28). The most effective campaigns should consider cultures, social norms, messaging, multiple communication channels and digital exclusion in their design (29) and include people from the target population in the design and evaluation.

Successful examples are often commission by multiple sectors (voluntary, national, local, government, commercial) and include Public Health England’s ‘It Starts with me’ (30), London councils ‘Do it London’ (31), voluntary sector ‘Can’t pass it on’ (32) and ‘Me.Him.Us’ (33).

2.5 Condoms

Condoms physically stop sperm, vaginal fluids, viruses and bacteria getting from one person to another during sex. When used correctly, they are effective at preventing HIV transmission. Unlike other prevention tools they are also effective at preventing pregnancies and other sexually transmitted infections.

Over the last 40 years, condoms were a central part of strategies to prevent HIV transmission, but they now sit alongside a bigger toolbox of options forming HIV combination prevention. They remain cheap, easy to find, only used during sex (unlike biomedical interventions), free of side effects (latex free options are available), easy to use without support from a health worker. Condoms are an effective method of preventing the onward transmission of HIV with a ‘real world’ effectiveness (as opposed that of a Laboratory which is 99.5% effective) of between 70% to 80% for heterosexual couples (18), (16) and 70% (17) to 92% (19) for gay couples, where in both instances the couples use condoms every time they have sex when compared with couples that state they do not have sex at all.

Free condom distribution schemes are widely commissioned by local authorities. Evidence has shown condom distribution schemes successfully reach communities and groups at greater risk such as young people including those aged 16 to 19 years, individuals of ethnic minority backgrounds and those living in deprived areas.

However, condoms are not always used correctly and can break, and they are often not used consistently. For some people, they represent a barrier to pleasure, keeping an erection and intimacy.

A YouGov survey conducted in 2017 found that almost half of sexually active young people said they have had sex with someone new for the first time without using a condom and 1 in 10 sexually active young people said that they had never used a condom (34).

Condom usage among gay and bisexual men has declined. Data from the London Gay Men’s Sexual Health Survey (35) shows an increase in reported condomless anal sex from 43% in 2000 to 60% in 2016 in the 3 months prior to being interviewed. Use is likely to have decreased further due to the increasing availability of PrEP.

The Mayisha 2016 study into HIV testing and sexual health among black African men and women in London found that a fifth of women (20.7%) and a quarter (25.0%) of men reported condomless last sex with a partner of different or unknown HIV status in the previous year (36).

Partners are not always confident or able to negotiate use of condoms, particularly in unequal relationships. The Scottish Government commissioned a co-developed, mixed-methods Conundrum study with 16 to 24 year olds in 2019. Negotiating condom use with new sexual partners was often described as difficult (37).

The Conundrum study reported almost half of survey respondents did not know where to access free condoms. Access to services was further impeded by embarrassment about face-to-face interactions, concerns about anonymity, a perceived lack of understanding about condom sizes and fit, and perceived lower quality of free products. A YouGov study in 2019 found many young people indicated a preference for free condom services that require minimal face-to-face contact, with online ordering of condoms posted home by far the favoured option across all genders (34).

Free Condom Distribution Programmes have been proven to increase condom use, prevent HIV/STIs, and save money (11). Condom schemes successfully reach key vulnerable groups of young people including those aged 16 to 19 years, of black Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds and living in deprived areas (38), though it should be noted that this same access and availability of condoms does not extend to all populations.

2.6 Biomedical interventions

There are several established and emerging biomedical interventions for HIV prevention. Current options include the use of antiretroviral medication among people living with HIV to prevent transmission (treatment as prevention or treatment as prevention, also described as U=U) as well as the use by people without HIV before or after exposure to the virus (pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis, respectively). There are ongoing studies investigating the use of vaccines for HIV prevention and treatment.

2.6.1. PrEP

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the use of ART medication by HIV-negative people to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV. PrEP is taken before and after any potential exposure to the virus. PrEP can be administered through a variety of routes although in England, since October 2020, only oral PrEP using a fixed dose combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir (F/TDF) is commissioned by NHSEI. Oral F/TDF as PrEP has been shown to be highly effective at reducing the risk of acquiring HIV among all key population groups including men who have sex with men, transgender men and women, heterosexual men and women and injecting drug users(39). PrEP, as part of combination HIV prevention, has been shown to be cost-effective, and cost-saving in some scenarios, within England-specific health economic models (40).

Oral PrEP has been commissioned in specialist sexual health services in England since October 2020. NHSEI is responsible for purchasing the generic F/TDF. Local authorities cover the associated PrEP-related care for which additional funding was provided from central government (£11 million in financial year 2020 to 2021 and £23.4 million in 2021 to 2022). This PrEP-related care includes HIV testing, STI testing and treatment and renal monitoring necessary to safely provide PrEP in line with national clinical guidelines. Delivery routes for parenteral (not by mouth) PrEP include long acting injectable ART and vaginal rings. Long-acting injectable Cabotegravir (CAB LA) is delivered by injection every 8 weeks and shown to be superior to oral F/TDF for preventing HIV in the HPTN083 study. The dapivirine vaginal ring (DAP VR) has been recommended as a new choice for HIV prevention for women at risk of HIV by the World Health Organization following findings from the ASPIRE and The Ring Studies. Neither option is currently available in the UK although increasing the choices for how PrEP is used could help to increase uptake, as seen with contraception.

Data from the Impact Trial show some evidence that PrEP use is disproportionately distributed across key populations that could benefit from PrEP in England (41). Of the 24,55 individuals recruited to the PrEP Impact trial, 95.7% were gay or bisexual men. Of these, over half were between the ages of 25 and 50 years and 76% were white. Among the 1,040 individuals in the women and other groups, approximately equal numbers of trans and women were recruited (around 340 each) and trans and men (around 150 each).

Evidence from qualitative work with black African women suggests that PrEP prevention messages were targeting white men who have sex with men. To engage black African or black Caribbean women who might benefit from PrEP, campaigns will need to use multiple levels of influence that shape their safer sex perceptions. Helping women understand how PrEP fits into their personal relationships will be critical (42).

2.6.2 Post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is the use of ART medication by HIV-negative people to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV after a potential exposure to the virus. PEP must be started within 72 hours of any potential exposure and taken daily for 28 days (43). PEP can be given following an occupational exposure (for example, following a needle stick injury in a healthcare professional) or following a sexual exposure (following sexual exposure or nonoccupational). Currently, PEP is available through hospital accident and emergency departments and specialist sexual health services in England.

The most recent UK PEP guidelines have taken account of U=U and do not advise the use of PEPSE following condomless sex with someone who has an undetectable viral load. Likewise, PEP would not be needed for someone who is taking PrEP correctly. Once someone finishes PEP they can be started immediately on PrEP if appropriate.

2.6.3 Other biomedical prevention strategies

While there have been many HIV vaccine trials; none have yet demonstrated sufficient efficacy to support implementation of a vaccine for prevention. The HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) continues to fund and deliver HIV vaccine research with the goal of developing a safe, effective vaccine as rapidly as possible for HIV prevention globally. Should an efficacious vaccine be developed, work to understand how best to implement it within the UK context would be required.

3. HIV testing and national guidelines

3.1 Key points

- The UK offers free HIV testing in a wide range of settings that include sexual health services, primary care, secondary care, prisons, community testing, home and online regardless of residency status

- We have effective evidence-based HIV testing guidelines and high rates of HIV testing in sexual health services. However, rates have not reached 99% as observed in antenatal and blood donation settings. There are missed opportunities for testing with high rates of declining tests among heterosexuals, which contributes to high levels of late diagnoses

- There is patchy implementation of guidelines outside of sexual health services, but it is not possible to measure this well

- Partner notification is extremely effective tool, but it is a complex process requiring intensive work

3.2 Background

HIV diagnosis is the access point that enable prompt, effective treatment which both benefits individuals clinically and prevents the onward spread of infection, while a negative test result enables counselling and PrEP where appropriate. HIV testing is free and confidential for everyone, regardless of migration or residency status. The UK now offers testing in a wide range of settings that include sexual health services, primary care, secondary care, prisons, community, online and home.

Social marketing campaigns such as National HIV Testing Week play a crucial role in bringing to people’s attention the need and ease of testing, and in the promotion of testing options including the national self-sampling service.

However, due to the steady fall in the numbers of undiagnosed HIV infections, the number of tests that are now needed to diagnose one new HIV infection has increased and the proportion of tests that are positive has fallen.

3.3 Current HIV testing guidelines

The 2020 British HIV Association (BHIVA)/British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH)/British Infection Association (BIA) Adult HIV Testing Guidelines (44) and 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (45) recommend universal HIV testing in sexual health services and promote the normalisation of routine HIV testing in particular they support:

- HIV testing in primary and secondary care based on local HIV prevalence and patient risk

- HIV testing in community settings in areas with a high or extremely high prevalence and for groups and communities at a high risk of HIV

- self-sampling test kits for groups and communities with high rates of HIV

- offering HIV testing of people recently diagnosed with HIV through partner notification procedure

Despite national guidelines and recommendations, the implementation remains patchy resulting in many missed opportunities for testing (46). Unfortunately, there is no perfect system to measure HIV testing in settings outside of sexual health services.

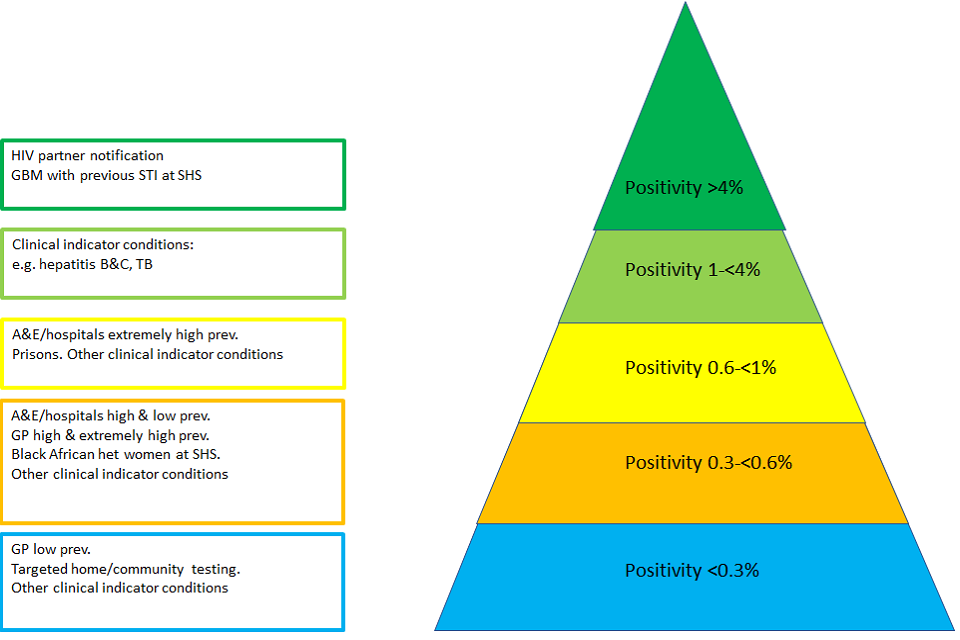

In England the number of new HIV diagnoses, late diagnoses and estimated incidence have been decreasing over the last 10 years. While this is good news, it makes it increasingly difficult to implement HIV testing in a cost-effective manner. Positivity, defined as proportion HIV diagnoses made among those tested, will continue to decrease and require more resources and targeting of HIV testing in groups and communities with high HIV positivity rates. Figure E outlines what is known of positivity in different settings. HIV positivity is highest through partner notification, but lowest in community/home testing settings in low prevalence areas.

Figure E: HIV testing positivity pyramid, England 2019

Figure E shows a HIV testing positivity pyramid, England 2019. Figure E is a pyramid with 5 layers. Each layer represents a different rate of HIV testing positivity in England. Areas with a positivity of <0.3% occur in settings such as testing via GP in low prevalence areas, targeted home/community testing and for other clinical indicator conditions. Areas with a positivity of 0.3-<0.6% include testing via A&E/hospitals in areas of high and low prevalence, via GP in high and extremely high prevalence areas, for black African heterosexual women at sexual health services and for other clinical indicator conditions. Areas with a positivity of 0.6-<1% include testing via A&E/hospitals in areas of extremely high prevalence, prisons and for other clinical indicator conditions. Areas with a positivity of 1-<4% include examples such as testing for clinical indicators conditions, for example hepatitis B&C, TB. Areas with a positivity of >4% relate to HIV partner notification and for testing for gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men with a previous STI at a sexual health service.

3.4 HIV testing in sexual health services and other health care settings

In 2019, 1,310,730 eligible attendees were tested for HIV in sexual health services. However, with a test coverage of 65%, 549,850 eligible attendees were not tested for HIV (2). The national positivity rate was 0.2% in 2019. While there has been a continued increase in HIV testing in sexual health services, this has been driven by increased testing of gay and bisexual men. Testing regularly remains a challenge among heterosexuals most at risk of HIV.

Most (77%) were tested in specialist sexual health services. Internet services have expanded rapidly and tested 232,740 people for HIV in 2019, a 63% rise since 2018, constituting 18% of those tested at all sexual health services. The demographic profile of those using internet services compared to specialist sexual health services was similar in terms of ethnicity and sexual orientation. However, 81% of those using internet services were aged under 35 compared to 73% at specialist sexual health services (2). This compares to universal testing implemented in antenatal and blood donation services which reach of over 99% coverage.

The following targeted interventions are based on higher positivity rates within these populations/settings (38), (39):

- In 2019, gay and bisexual men who have not tested within the last 2 years (at the same specialist sexual health services) were more likely to test positive for HIV compared to gay and bisexual men who tested more recently. This highlights the importance of offering all men who have ever had sex with another man a test for HIV.

- A high proportion of gay and bisexual men who are diagnosed with an anogenital bacterial STI test positive in the following year. However, less than half of gay and bisexual men diagnosed with an anogenital bacterial STI in 2017 tested for HIV at the same service in the following year. Test positivity within this group was 4.9%, with one HIV infection diagnosed for every 21 men tested (12).

- There has been a steep increase in A&E HIV testing resulting in a fall in positivity from 1.3% to 0.7%. Even with this fall, this reflects a higher positivity rate than in most settings (2).

- Increasing access to testing by promoting HIV testing at home and in the community. This includes use of HIV self-sampling, self-testing, community- based organisations, and pharmacies.

- All new arrivals and people transferring between prisons should be offered HIV tests. The programme of blood-borne virus testing in prisons identifies infections among those who may not access other testing services. The efforts to achieve the target testing threshold of 75% uptake are continuing. Between April and December 2019, the HIV test offer rate was 94%, however test uptake was 46%. Testing a total of 57,171 people in this setting in 2019 identified 401 HIV infections (0.7% positivity compared with 1.2% in 2017 to 2018) (2).

- Innovations such as the Zero HIV Social Impact Bond (SIB) are outcomes-based outcome-based projects funding short-term initiatives with long-term benefits. The SIB model ends in 2021.

3.5 Partner notification

Partner notification (PN) is a voluntary process where trained health workers ask people diagnosed with HIV about their sexual partners or drug injecting partners, and with their consent offer these partners HIV testing (47). Since HIV test positivity in contacts of recently diagnosed people living with HIV is much higher than that of people attending sexual health clinics, PN is extremely cost effective. It allows a linked chain of persons unaware they are living with HIV and linking them to care. PN is also important in identifying HIV negative partners who may be at higher risk of HIV and would benefit from effective HIV prevention (for example PrEP).

The overall HIV test positivity was 4.6%, this is substantially higher than the HIV test positivity in sexual health services overall (0.1%). A recent BASHH audit of 1,399 contacts tested through PN found 293 (21%) were newly diagnosed with HIV and regular partners were most likely to test positive (48).

PN can be done either by the person diagnosed with HIV through a direct conversation with their partner(s) or by the health service who confidentially trace and notify the partner(s) directly. It is a complex activity requiring considerable skills and resources at the clinic level, in particular support from specialist sexual health advisers, and might need modification of current service models.

There is a need to explore acceptability and costs of PN methods especially for key populations and for key partner types (for example, one off or anonymous partners). Ongoing work as part of National Institute for Health Research (49) will lead to the development of theoretically informed PN intervention for gay and bisexual men who have sex with men with ‘one-off’ partners for STIs and HIV.

4. Rapid access to treatment and retention in care

4.1 Key points

-

The quality of care of care from diagnosis is excellent in England.

-

Over two thirds of people living with HIV infection who have transmittable levels of virus are diagnosed and aware of their infection. They are either not linked to care, not retained in care, not yet on treatment or not yet virally suppressed.

-

While most people are linked to care within one month, people diagnosed in settings outside of sexual health services have more of a delay. There is variation between services in how quickly people start treatment

-

Peer support is established as useful tool to ensure retention in care and adherence to treatment

4.2 Background

Early initiation of HIV treatment and resulting prompt viral suppression limit the damage to the immune system and reduce the risk of developing complications and of death. In addition to the clinical benefits of treatment, achieving and maintaining viral suppression prevents onward transmission of the virus. It is well established that people who are virally suppressed cannot pass on HIV to partners, even if having sex without condoms and PrEP (22), (23).

In England, as elsewhere in the UK, the quality of care received by people living with HIV following diagnosis is excellent. In England people living with HIV are generally very satisfied with their HIV services (6). In 2019, it was estimated that 94% of people living with HIV were diagnosed, 98% were treated and 97% were virally undetectable (2), meeting the international UNAIDS targets for the third consecutive year (50). However, this metric overestimates the number of people with detectable virus as it does not account for people who are diagnosed but not yet accessing care and those not retained in care year on year.

While viral suppression varies between groups, in 2019 there was little geographical or demographic variation. Viral suppression was lowest among people aged 15 to 24 years (91%), people who probably acquired HIV through injecting drug use, (94%) and among people who probably acquired HIV through mother to child transmission (89%).

We need to ensure everyone who is diagnosed is referred to treatment rapidly and ensure that inequalities in access to and retention in treatment are tackled.

4.3 Transmittable viral load

In 2019, UKHSA analyses (that also take into account people diagnosed but not linked/retained in care and/or with missing viral load information) showed that up to 18,160 people living with HIV in England had transmissible levels of virus, equivalent to 19% of people living with HIV in England. Of these, an estimated 5,930 (CrI 4,400 to 8,700) were undiagnosed, 3,890 (21%) were diagnosed but not referred to specialist HIV care or retained in care, 1,630 (9%) attended for care but were not receiving treatment, and 2,110 people (12%) were on treatment but not virally supressed. The remaining 4,600 (25%) had attended for care but were missing evidence of viral suppression.

Figure F: estimated number of people living with HIV who have transmittable levels of virus, UNAIDS definitions: England, 2019

Figure F shows the estimated number of people living with HIV who have transmittable levels of virus, UNAIDS definitions: England, 2019. This shows that 5900 people are estimated to be undiagnosed, and 320 are estimated not to be linked to care. 3,600 are estimated not to be retained in care, and 1,600 are estimated not to be on treatment. An estimated 4,600 people are on treatment with no reported viral load, and an estimated 2,100 people are on treatment with a viral load in excess of 200 copies per ml.

An estimated 91% of people living with transmittable levels of virus were 15 to 59 years old. Gay and bisexual men constituted 41% of people living with transmittable levels of virus, 20% were heterosexual men and 30% heterosexual women (51).

4.4 Rapid link to care

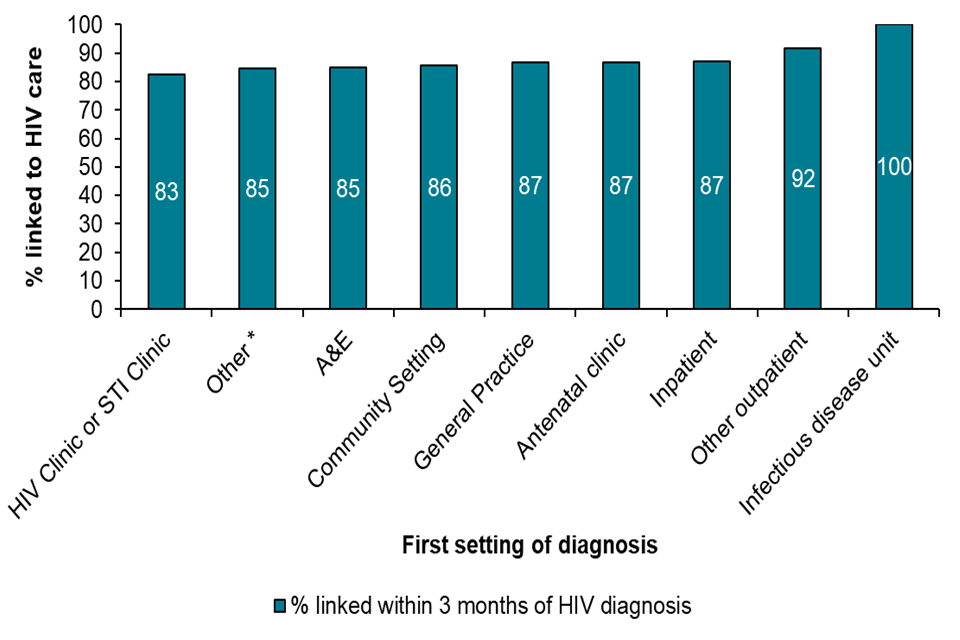

In 2019, among those living in England, 84% (3,080 out of 3,650) of adults who were newly diagnosed in 2019 were linked to specialist HIV care within 3 months, and 78% within one month. The number of individuals linked to specialist HIV care varied by first setting of diagnosis. For those linked within one month of diagnosis, by first setting, linkage was highest in those diagnosed in infectious disease units (98%) and lowest in those diagnosed in settings (75%) that included blood transfusion services, prisons, home testing, drug misuse services, self-sampling services, pharmacies, and setting/service not reported.

Figure G: Linkage to HIV care within 3 months among people diagnosed with HIV and living in England, 2019

Figure G is a bar chart showing the percentage of people linked to HIV care within 3 months among people diagnosed with HIV and living in England, 2019. This shows that 100% of patients in infectious disease units are linked to HIV care. 92% of people are linked to care in other outpatient settings, and 87% in inpatient settings, and 87% are linked to care in antenatal clinics and general practice. 86% are linked to care in community settings, and 85% within A&E. 85% are linked to care in other settings and 883% are linked to care in HIV or STI clinics.

4.5 Retention in care

Overall, 96% of people living with HIV in England who were seen for specialist HIV care in 2018 were seen again in 2019. The number of people not retained in care in 2019 was 3,600; 45% (1,600) had acquired HIV through sex between men, 18% (630) were black African women who acquired HIV through heterosexual contact, 46% (1,660) were living in London, 34% (1,219) were aged 45 to 69 years, 30% (1,072) 35 to 44 years and 26% (931) 15 to 34 years.

4.6 Early ART

In England, almost all people (98%) engaged in HIV care in 2019 were receiving ART. In 2019, 80% of people diagnosed with HIV and living in England received treatment within 91 days of HIV diagnosis. There was considerable variation in time to treatment between services (range 0 to 576 days).

4.7 Viral suppression

In 2019, of people receiving ART where a viral load result was reported, 97% were virally suppressed (defined as under 200 copies per ml). There was little geographical or demographic variation, however viral suppression was lowest among people aged 15 to 24 years (91%), people who probably acquired HIV through injecting drug use, (94%) and among people who probably acquired HIV through vertical transmission (89%).

4.8 Peer support

Peer support aids and encouragement by an individual considered equal, in taking an active role in self-management of their chronic health condition. The WHO guidelines state that peer support can help people prepare to start therapy (52), (53).

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis has demonstrated that ‘peer-support with routine medical care is superior to routine clinic follow-up in improving outcomes for people living with HIV. It is a feasible and effective approach for linking and retaining people living with HIV to HIV care, which can help shoulder existing services’ (54). The study demonstrated long term effects particularly in relation to retention in care.’

5. Emotional wellbeing and quality of life for people living with HIV and tackling stigma

5.1 Key points

-

People living with HIV have complex clinical needs, particularly as they age, and this impacts on quality of life. Knowledge of HIV in health services outside the field requires improvement.

-

People living with HIV have experience stigma and discrimination in the health service which has acted as a barrier to access

-

People are entitled to emotional wellbeing - without this it is very difficult to prioritise HIV care

5.2 Background

All people living with HIV should be entitled to emotional wellbeing, quality of life and freedom from stigma.

It is also important from an HIV prevention standpoint. It is not easy for anybody to prioritise HIV testing, HIV care and adherence to treatment if we are experiencing personal social, financial, or emotional difficulties.

Good quality of life and absence from stigma is key to ending transmission since it puts people in the best position to access services and maintain treatment and viral suppression in the long term.

5.3 Emotional wellbeing

HIV clinical outcomes are excellent for people living with HIV in England since provision of care and treatment is free and open access. However, as people with HIV age, they are faced with new challenges such as increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer.

Currently, 60% of people living with HIV manage a chronic condition in addition to their HIV, requiring the use of several, often non-integrated health care services (6). Lack of HIV knowledge outside of specialise care settings and HIV associated stigma creates inequalities in the provision of services and act as barriers to access the support needed. This is a particular problem for groups such as transgender people for whom trans specific culturally informed health services and organisations are lacking.

People living with HIV often experience many burdens associated with being HIV positive in addition to managing the condition itself. Many people living with HIV report psychological and social concerns affecting their wellbeing in addition to clinical symptoms and pain.

People living with HIV reported a high degree of unmet need. Overall, 31% of people living with HIV needed a psychologist or counsellor in the previous year; of those, 38% did not see one. Similarly, 21% needed help dealing with loneliness and isolation in the past year, but in 75% of cases this need was unmet.

HIV support services, often run by charity or voluntary organisations, provide services that meet the physical, mental and emotional health needs of people with HIV that are complementary to clinical care. Overall, 38% had used an HIV support service, with 92% of those who had used such a service reporting that it had been important to their health and wellbeing. However, of those who had used support services, 33% said that services had become more difficult to access over the previous 2 years (6).

Peer support is has also found to be invaluable in promoting emotional wellbeing and subsequent retention in care (section 4.6). The HIV and Later Life study found such interactions provided a range of social benefits including emotional support, practical information, social activity and safe space, as well as making an important contribution to reducing stigma (55).

5.4 Quality of life

Findings from the 2017 Positive Voices survey (6) showed that people with HIV reported high ratings on the 3 measures of health and wellbeing (self-rated health, life satisfaction, and health-related quality of life [EQ-5D]), reflecting HIV treatment outcomes in the UK. However, mental ill health is a primary concern among people with HIV, who also experienced a higher burden compared to the general English population. Over one third (37%) of people with HIV were diagnosed with a clinical mental health disorder in their lifetime. Around half (49%) of people with HIV reported symptoms of depression and anxiety on the day of the survey; much higher than in the general population (30%). One in 4 (28%) had a General Health Questionnaire score of 4 or more, indicating probable mental ill health at the time they were surveyed, compared to 19% of the general population.

5.5 Stigma and discrimination

Stigma and discrimination undermine confidence, causes fear, anxiety, depression, loneliness and isolation and overall poor mental health. People with poor mental health are also more likely to have less healthy life styles including smoking and use of alcohol and non-prescription drugs (56), (57), (58] and have fewer opportunities for employment and decreased access to financial support.

People living with living with HIV have reported experiencing stigma and discrimination within the health care services. Because of stigma and discrimination, in 2017, one in 10 avoided seeing health care when they needed to and one in 6 worried about being treated differently. One in 5 reported to have been treated differently to other patients (one in 12 in the last year) and one in 9 felt they were refuse healthcare or delayed a treatment or medical procedure (6% in the last year) (6). The National AIDS trust found that in 2020, 80% of people surveyed agreed people living with HIV often face negative judgement from others in society (9).

Social marketing can be an effective tool to challenge stigma (28). Addressing stigma should be considered as a component of all social marketing campaigns. A recent survey from NAT found increased knowledge about HIV transmission and treatment appeared to decrease (though not eliminate) discomfort about sexual relationships with people living with HIV (9), (28).

References

- Nakagawa F, May M, Phillips A. Life expectancy living with HIV: recent estimates and future implications. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2013;26(1):17-25.

- Public Health England. Trends in HIV testing, new diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2019. 2020.

- Brizzi F BP, Plummer MT, Kirwan P, Brown AE, Delpech VC, et al Extending Bayesian back-calculation to estimate age and time specific HIV incidence. . Lifetime Data Analysis. 2019;25(4):757-80.

- Presanis AM, Harris RJ, Kirwan PD, Miltz A, Croxford S, Heinsbroek E, et al. Trends in undiagnosed HIV prevalence in England and implications for eliminating HIV transmission by 2030: an evidence synthesis model. The Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(10):e739-e51.

- HIV and AIDS Reporting System. In: UK Health Security Agency, editor. Data from the HIV and AIDS Reporting System ed. London.

- Public Health England. Positive Voices: The National Survey of People Living with HIV. Findings from the 2017 Survey. 2020.

- Croxford S, Kitching A, Desai S, Kall M, Edelstein M, Skingsley A, et al. Mortality and causes of death in people diagnosed with HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy compared with the general population: an analysis of a national observational cohort. The Lancet Public health. 2017;2(1):e35-e46.

- Nakagawa F, Miners A, Smith CJ, Simmons R, Lodwick RK, Cambiano V, et al. Projected Lifetime Healthcare Costs Associated with HIV Infection. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125018.

- National AIDS Trust. HIV: Public knowledge and attitudes. 2021.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV Combination Prevention. Monitoring implementation of the Dublin Declaration on partnership to fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia: 2018 progress report. Stockholm; 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Condom Distribution as Structural Level Intervention 2019

- Public Health England. HIV in the United Kingdom: Towards Zero HIV transmissions by 2030: 2019 report. 2019.

- Changing Perceptions. Talking about HIV and our needs 2018

- HIV Commission. How England will end new cases of HIV: The HIV Final Report & Recommendations. 2020.

- Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV Survival. Time from HIV-1 seroconversion to AIDS and death before widespread use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative re-analysis. Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV Survival including the CASCADE EU Concerted Action. Concerted Action on SeroConversion to AIDS and Death in Europe. Lancet (London, England). 2000;355(9210):1131-7.

- Weller SC, Davis‐Beaty K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002(1).

- Smith DK, Herbst JH, Zhang X, Rose CE. Condom effectiveness for HIV prevention by consistency of use among men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2015;68(3):337-44.

- Giannou FK, Tsiara CG, Nikolopoulos GK, Talias M, Benetou V, Kantzanou M, et al. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on HIV serodiscordant couples. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2016;16(4):489-99.

- Johnson WD, O’Leary A, Flores SA. Per-partner condom effectiveness against HIV for men who have sex with men. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32(11):1499-505.

- HIV Prevention Trials Network. HPTN 052: A Randomised Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Antiretroviral Therapy Plus HIV Primary Care versus HIV Primary Care Alone to Prevent the Sexual Transmission of HIV-1 in Serodiscordant Couples 2021

- Yin Z, Brown AE, Rice BD, Marrone G, Sönnerborg A, Suligoi B, et al. Post-migration acquisition of HIV: Estimates from four European countries, 2007 to 2016. 2021;26(33):2000161.

- Prevention Access Campaign. Consensus Statement: Risk of sexual transmission of HIV from a person living with HIV who has an undetectable viral load. 2021.

- Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, Degen O, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. The Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2428-38.

- Cohen M, Chen Y, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour M, Kumarasamy N, et al. Final results of the HPTN 052 randomized controlled trial: Antiretroviral therapy prevents HIV transmission. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18.

- Denford S, Abraham C, Campbell R, Busse H. A comprehensive review of reviews of school-based interventions to improve sexual-health. Health psychology review. 2017;11(1):33-52.

- He J, Wang Y, Du Z, Liao J, He N, Hao Y. Peer education for HIV prevention among high-risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(1):338.

- LaCroix JM, Snyder LB, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT. Effectiveness of mass media interventions for HIV prevention, 1986-2013: a meta-analysis. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2014;66 Suppl 3:S329-40.

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2009;51(4):492-501.

- Public Health England. Sexually Transmitted Infections: promoting the sexual health and wellbeing of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. 2021.

- https://www.startswithme.org.uk/

- https://doitlondon.org/

- https://www.tht.org.uk/our-work/our-campaigns/cant-pass-it-on

- https://www.gmfa.org.uk/mehimus

- Campaign to protect young people from STIs by using condoms [press release]. 2017.

- Logan L, Fakoya I, Howarth A, Murphy G, Johnson AM, Rodger AJ, et al. Combination prevention and HIV: a cross-sectional community survey of gay and bisexual men in London, October to December 2016. 2019;24(25):1800312.

- Fakoya I, Logan L, Ssanyu-Sseruma W, Howarth A, Murphy G, Johnson AM, et al. HIV Testing and Sexual Health Among Black African Men and Women in London, United Kingdom. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(3):e190864-e.

- Lewis R, Blake C, McMellon C, Riddell J, Graham C, Mitchell K. Understanding young people’s use and non-use of condoms and contraception. A co-developed, mixed-methods study with 16-24 year olds in Scotland. Final report from CONUNDRUM (CONdom and CONtraception UNDerstandings: Researching Uptake and Motivations) 2021.

- Ratna N, Et al, editors. A quantitative evaluation of the London “Come Correct” Condom Card (C-Card) scheme: Does it serve those in greatest need? Fourth Joint Conference of the British HIV Association with the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV; 2018; Edinburgh.

- HIV Prevention Trials Network. HPTN 083: A Phase 2b/3 Double Blind Safety and Efficacy Study of Injectable Cabotegravir Compared to Daily Oral Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in HIV-Uninfected Cisgender Men and Transgender Women who have Sex with Men 2021

- Cambiano V, Miners A, Dunn D, McCormack S, Ong KJ, Gill ON, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men in the UK: a modelling study and health economic evaluation. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2018;18(1):85-94.

- Grimshaw C, Estcourt CS, Nandwani R, Yeung A, Henderson D, Saunders JM. Implementation of a national HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis service is associated with changes in characteristics of people with newly diagnosed HIV: a retrospective cohort study. 2021:sextrans-2020-054732.

- Nakasone SE, Young I, Estcourt CS, Calliste J, Flowers P, Ridgway J, et al. Risk perception, safer sex practices and PrEP enthusiasm: barriers and facilitators to oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in Black African and Black Caribbean women in the UK. 2020;96(5):349-54.

- British HIV Association. UK Guideline for the Use of HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis 2021 2021

- British HIV Association & British Association for Sexual Health and HIV & British Infection Association. Adult HIV Testing Guidelines 2020 2020

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. HIV testing: increasing uptake among people who may have undiagnosed HIV 2016

- Raben D, Mocroft A, Rayment M, Mitsura VM, Hadziosmanovic V, Sthoeger ZM, et al. Auditing HIV Testing Rates across Europe: Results from the HIDES 2 Study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0140845.

- Sullivan A, Rayment M, Azad Y, Bell G, McClean H, Delpech V, et al. HIV partner notification for adults: definitions, outcomes and standards 2015

- Rayment M CH CC, McClean H et. al. . An effective strategy to diagnose HIV infection: findings from a national audit of HIV partner notification outcomes in sexual health and infectious disease clinics in the UK. Sexually Transmitted Infections 2017;93(2):94-9.

- https://www.lustrum.org.uk

- UNAIDS. 90-90-90: Treatment for all 2021

- UK Health Security Agency. Bespoke Analyses.

- World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 2016.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2016-2021: towards ending AIDS. 2016.

- Berg RC, Page S, Øgård-Repål A. The effectiveness of peer-support for people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252623.

- Rosenfeld D, Anderson J. ‘The own’ and ‘the wise’ as social support for older people living with HIV in the United Kingdom. Ageing & Society. 2020;40(1):188-204.

- Zyambo CM, Burkholder GA, Cropsey KL, Willig JH, Wilson CM, Gakumo CA, et al. Mental health disorders and alcohol use are associated with increased likelihood of smoking relapse among people living with HIV attending routine clinical care. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1409-.

- Earnshaw VA, Eaton LA, Collier ZK, Watson RJ, Maksut JL, Rucinski KB, et al. HIV Stigma, Depressive Symptoms, and Substance Use. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2020;34(6):275-80.

- International HIV/AIDS Alliance. Quality of life for people living with HIV: what is it, why does it matter and how can we make it happen?; 2018.

-

Being diagnosed with HIV and having a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm³ (or certain indicator health conditions) would lead to a diagnosis of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). With effective antiretroviral treatment, very few people in the UK develop serious HIV-related illnesses. ↩