Cyber security longitudinal survey - wave three

Published 20 March 2024

Executive summary

Key findings

The purpose of the Cyber Security Longitudinal Survey (CSLS) is to investigate the change over time in organisations’ cyber security policies and processes, as well as looking at the relationship between these changes and the impact of cyber security incidents. This report covers the findings from the third wave of a multi-year survey, including comparisons to previous waves of the research (Wave One from 2021, Wave Two from 2022). It also summarises the differences between businesses and charities within Wave Three of the study, along with descriptive summaries of different sub-groups. The main stage survey for Wave Three took place between March and June 2023. Qualitative interviews took place between June and July 2023.

This report presents two types of analysis: cross-sectional and longitudinal. The cross-sectional analysis focuses on the differences between all responding organisations from each wave and therefore acts as a snapshot of organisations’ status at a given time. The longitudinal analysis, in contrast, analyses the organisations that have completed multiple waves of the survey and enables greater understanding of the changes these organisations experience over time. The longitudinal analysis is covered at the end of this chapter and in detail in Chapter 9.

This report also provides additional insight from 30 follow-up qualitative interviews with survey respondents that covered topics such as cyber security resilience, awareness and usage of the Cyber Essentials standard, record keeping, internal and external reporting, responsibility for cyber security, and monitoring of supply chains. These are presented alongside reporting on quantitative findings.

Broadly, businesses have a more formalised set of processes and policies in place than charities. This is particularly true among large (250 – 499 employees) and especially very large firms (500 or more employees), who are much more likely to have sophisticated approaches to cyber security. This is likely to reflect their higher budgets and ability to maintain specific cyber security staff. However, it is important to note that, for many organisations, the board is under-engaged and many of the processes that are in place are less proactive.

Overall, organisations have shown improvements in their cyber resilience since the first wave of the study. However, between Waves Two and Three, their resilience profile has largely remained stable. As budgets are often stretched and priorities are shifted, organisations may be less likely to invest heavily in cyber security and this may help to explain the broadly stagnant position between Waves Two and Three.

Below is a more detailed summary of key findings from each chapter of this report. The survey results are subject to margins of error, which vary with the size of the sample and the percentage figure concerned. For all percentage results, subgroup differences by size, sector and survey answers have been highlighted only where statistically significant[footnote 1][footnote 2](at the 95% level of confidence).

Cyber profile of organisations

As technology continues to develop, it has changed the way that people work. Changes range from remote working and cloud computing through to the growing importance of Artificial Intelligence (AI). These new challenges have necessitated shifts in the way that organisations respond to cyber security.

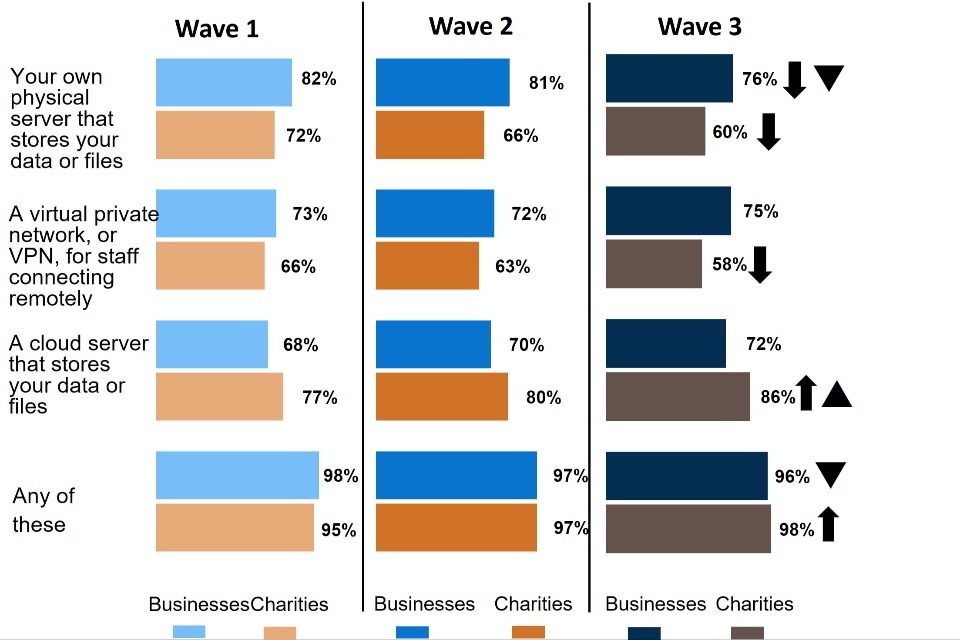

Almost all businesses (96%) and charities (98%) have a cloud or physical server to store data. Although, compared to previous waves of this study, this proportion has remained stable, the underlying trends have shifted. Increasingly, physical servers are less likely to be used by businesses (76% in Wave Three compared to 81% in Wave Two and 82% in Wave One) and charities (60% in Wave Three compared to 72% in Wave One).

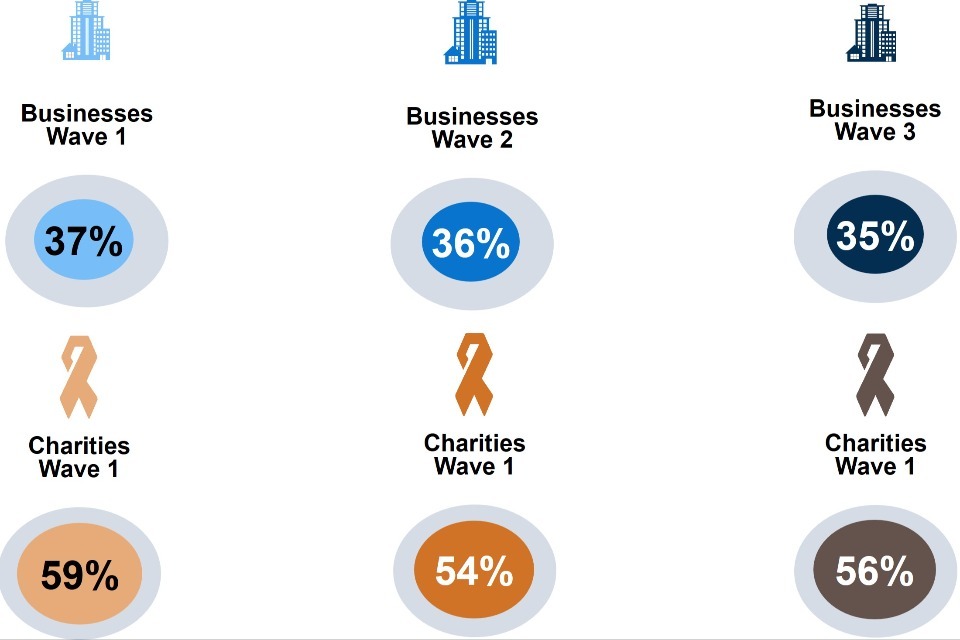

Charities are more likely than businesses (56% vs. 35%) to allow their staff to access their systems using a personal device. This has remained stable between the different waves of the survey. This is a good example of how charities tend to take a less formalised approach to cyber security than businesses. Further to this, given the lack of change between waves, it suggests that cyber security is not always a high priority for charities. In the qualitative phase, many respondents across businesses and charities noted that personal errors were likely to be the most common source of cyber breaches, suggesting that this topic is a vital area of improvement for organisations.

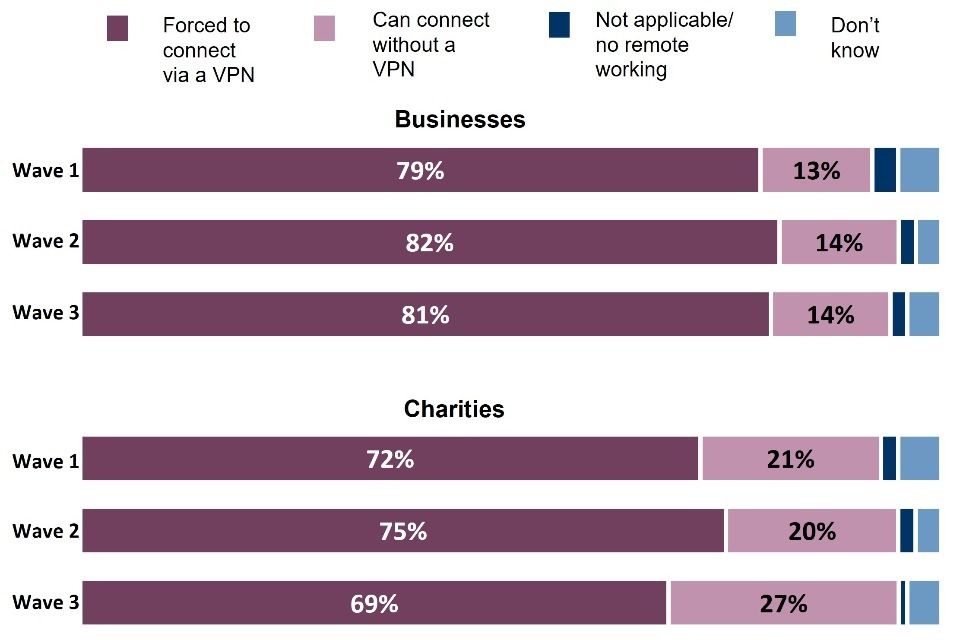

Mirroring the proportion of organisations that allow for access to systems with personal devices, businesses are also more likely than charities (81% vs. 69%) to require staff to use VPN for remote access, which has not dramatically changed compared to previous waves of the survey. Again, this suggests that businesses take a more formalised approach to cyber security.

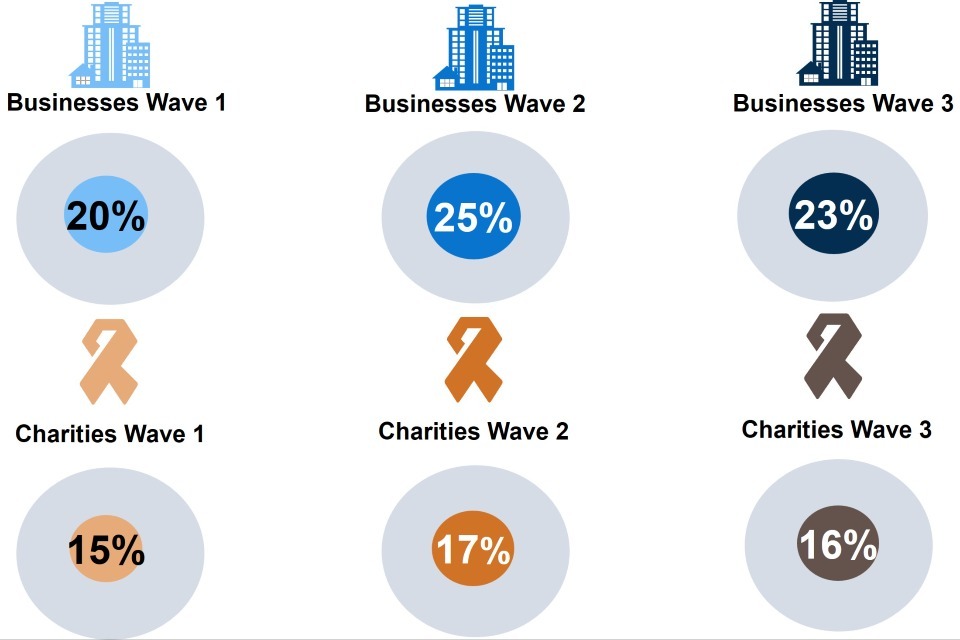

However, it is also important to note that both businesses (23%) and charities (16%) are currently not likely to use AI or machine learning as a means to improve their cyber resilience, which has not changed between Wave One and Wave Three. This suggests that organisations have not moved towards taking on cutting-edge technology to help improve their cyber resilience. Further, given the potential for these technologies to help organisations to act proactively, it is indicative of organisations’ reactive mindset.

Cyber security policies

Given the speed of developments in the cyber security area, it is vital that organisations keep their policies and governance up to date to ensure they remain secure and build their resilience.

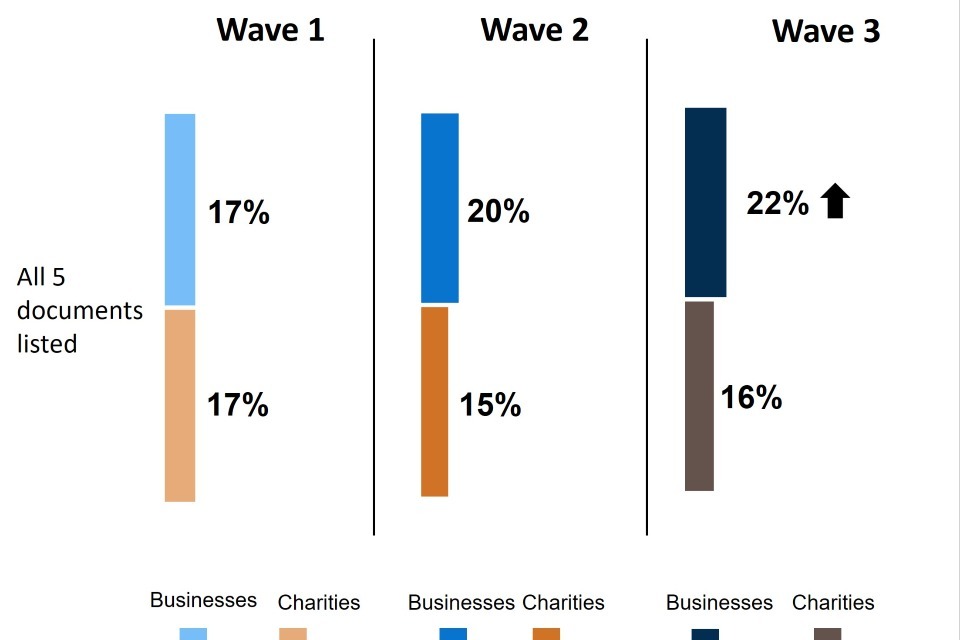

Respondents were asked about whether they have any of five best practice documents for cyber security governance: a cyber security business continuity plan, documentation to identify critical assets, a written list of IT vulnerabilities, a risk register, and a document outlining how much cyber risk they are willing to accept. Around nine in ten organisations have at least one of these five documents in place (89% of businesses and 92% of charities) This represents an improvement among businesses since Wave One. However, businesses are more likely than charities to have all five documents in place (22% vs. 16%). Although this is again indicative of businesses’ more holistic approach to cyber security, it also suggests most organisations still have room for improvement.

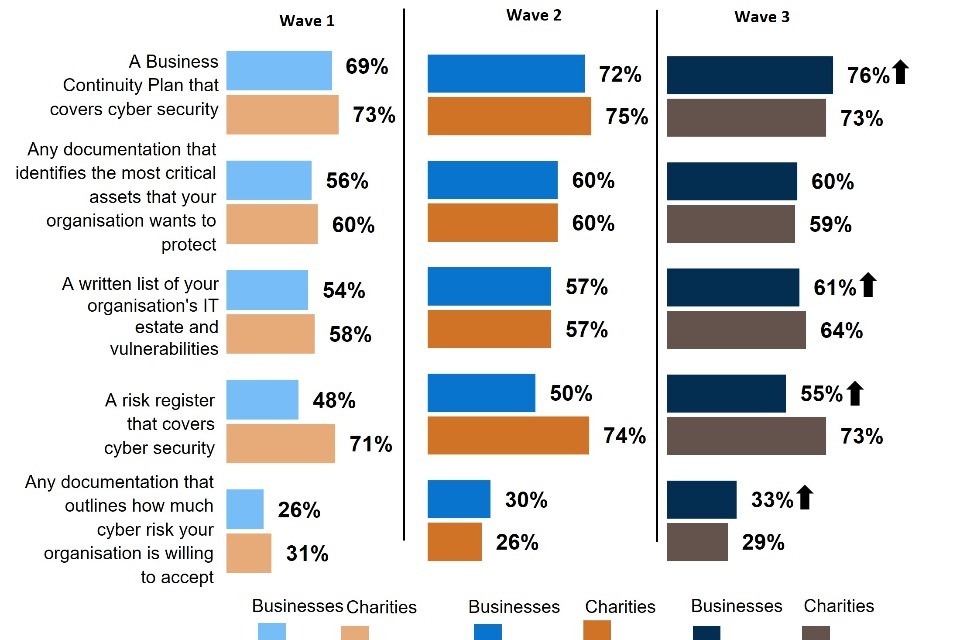

Since the first wave of the survey, an increased proportion of businesses have a business continuity plan that covers cyber security (76% in Wave Three vs. 69% in Wave One), a written list of their company’s vulnerabilities (61% in Wave Three vs. 54% in Wave One), and a risk register (55% in Wave Three vs. 48% in Wave One). However, there is little movement between Waves Two and Three. Charities by comparison are most likely to have a business continuity plan and risk register in place, which is consistent across waves.

The document that is least prevalent among organisations is a document outlining how much cyber risk organisations are willing to accept (33% among businesses, an increase compared to 26% at Wave One, and 29% among charities which is comparable to previous waves). Again, this indicates that organisations are not necessarily forward thinking in their planning for cyber security.

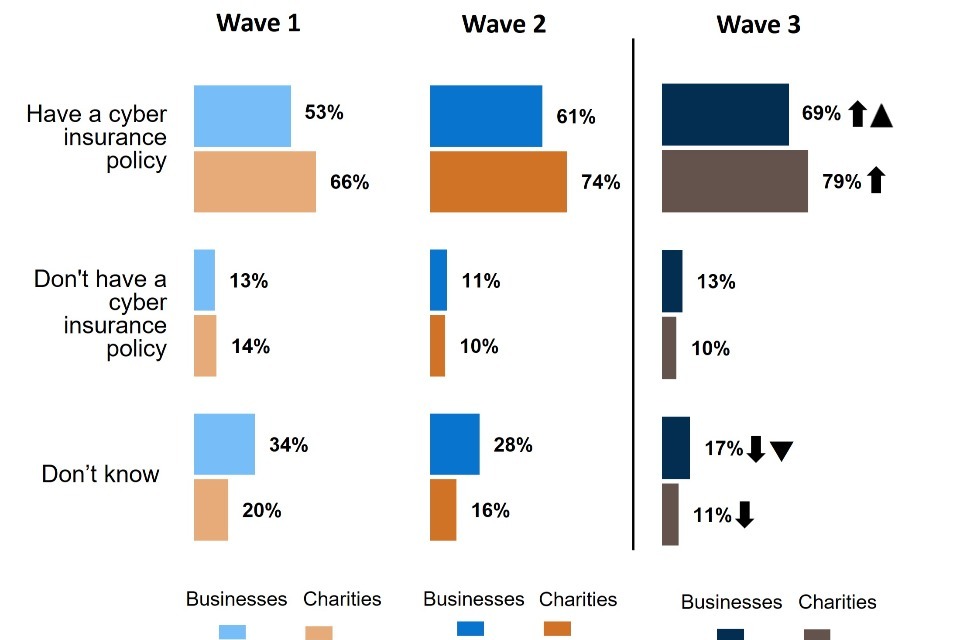

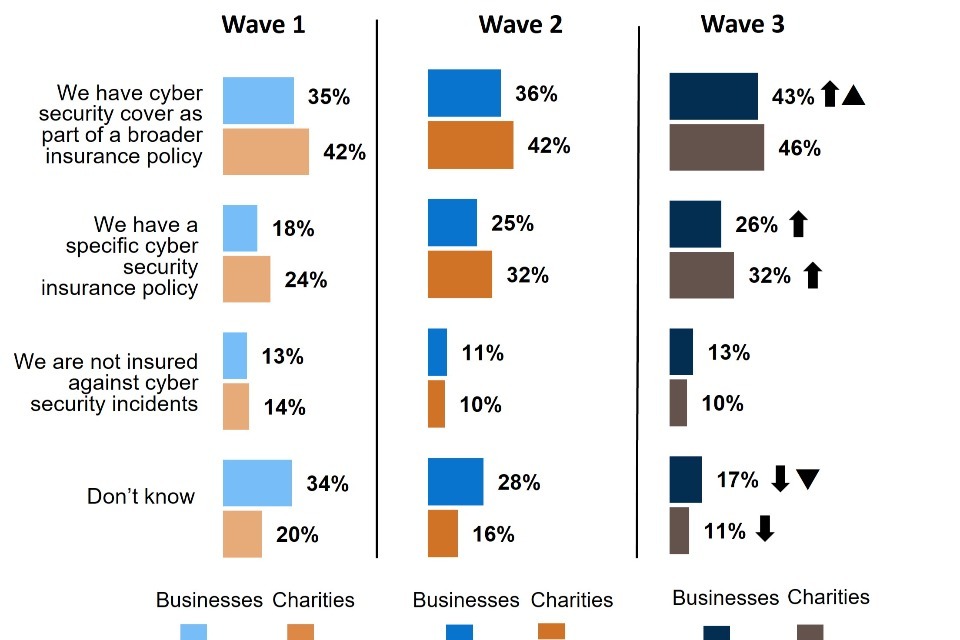

Businesses (69% in Wave Three vs. 61% in Wave Two and 53% in Wave One) and charities (79% in Wave Three vs. 66% in Wave One) are increasingly likely to have a cyber insurance policy. For businesses, this is most likely to be part of a broader insurance policy (43%), an increase on Wave Two (36%). Charities are also most likely to have a broad cyber insurance policy (46%), in line with previous waves (42% at both Wave One and Wave Two).

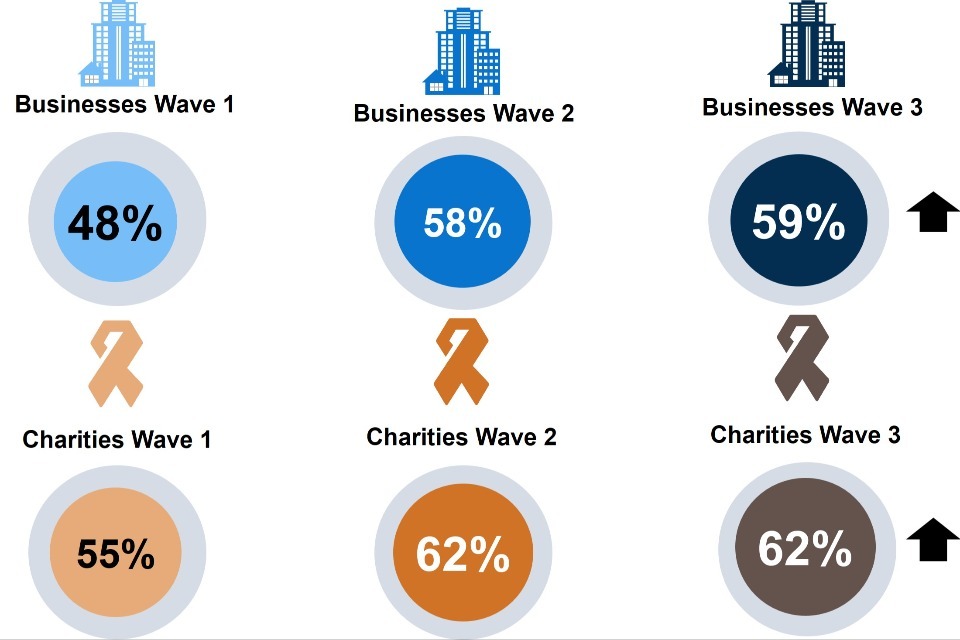

A majority of organisations have undertaken cyber security training or an awareness raising session, an increase on Wave One (59% of businesses in Wave Three vs. 48% in Wave One, and 62% of charities vs. 55% in Wave One). However, this has not changed substantively between Wave Two and Wave Three. This may indicate attempts among some organisations which have not put procedures in place to prevent their staff from accessing systems with their personal device, and to instead promote cyber security training and reduce human error.

Cyber security processes

In addition to updating their written policies and governance, organisations must also adapt their processes to ensure that they keep up with the changing cyber security environment. Respondents were asked about their adherence to three of the key cyber security certifications: Cyber Essentials Standard, Cyber Essentials Plus and ISO 27001.

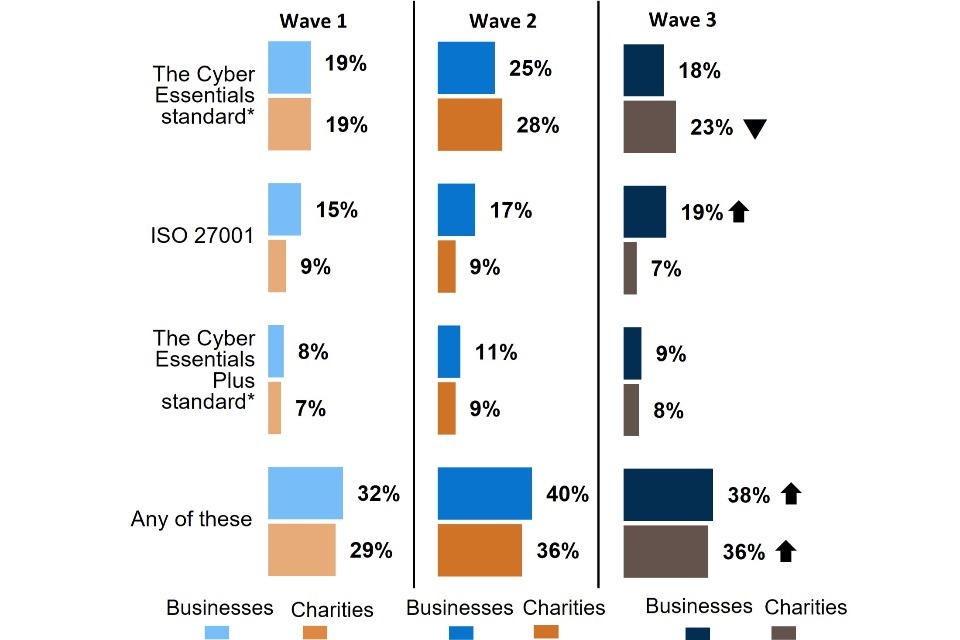

For both businesses and charities, more than one-third of organisations (38% of businesses and 36% of charities) adhere to at least one of these certifications. This represents a consolidation of the increases observed since Wave One but is comparable to the results from Wave Two.

Compared to Wave One, adherence to Cyber Essentials has increased among charities (23% in Wave Three vs. 19% in Wave One) but remains consistent for businesses across all three waves. Whilst it has not shown a significant improvement between Wave One (15%) and Wave Three (19%), findings from the qualitative interviews suggest the ISO 27001 certification is considered by businesses to be the most robust and substantive accreditation available.

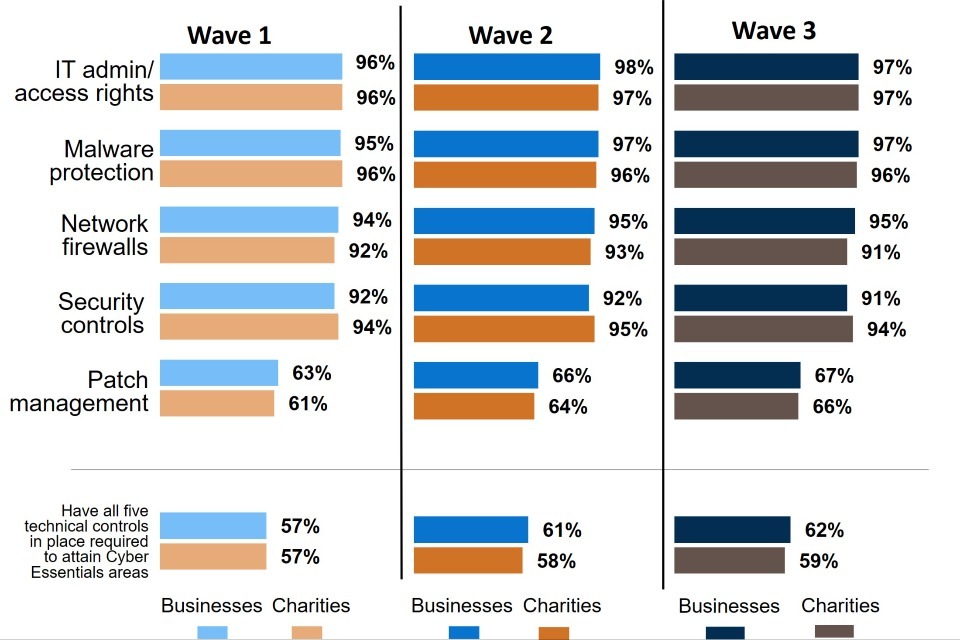

Consistent with previous waves of this survey, most organisations have put in place at least four of the five technical controls required to attain Cyber Essentials and around six in ten organisations (62% of businesses, 59% of charities) have all five. However, patch management (67% among businesses, 66% among charities) and user monitoring (58% of businesses, 55% of charities) remain the technical controls that organisations are least likely to have in place. There are two key implications of this: firstly, that organisations often do not invest in proactive measures and, secondly, that many organisations have put in place the controls required to attain Cyber Essentials but have not gained a full accreditation.

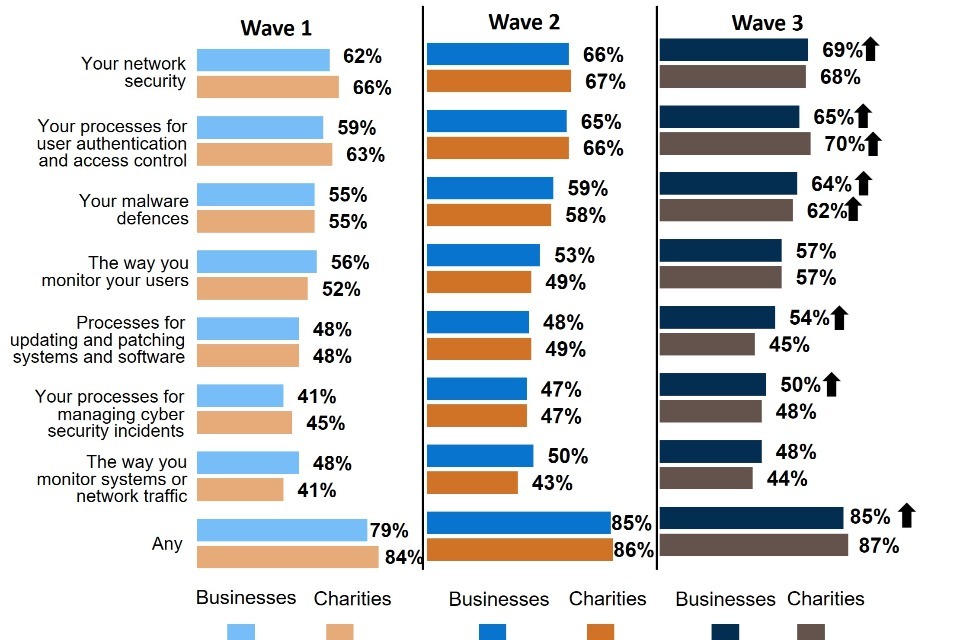

The proportion of businesses that have taken steps in the last twelve months to help identify risks to their cyber resilience has increased (90% in Wave Three, compared to 86% in Wave Two and 82% in Wave One). The proportion of businesses making changes in the last year to improve their cyber security has also increased since Wave One (85% vs. 79%), although it has remained consistent between Waves Two and Three (both 85%). This includes moves to integrate more proactive measures (for example, 54% of businesses have improved their patching systems), which suggests over time businesses are becoming more active in cyber security. This finding could potentially be worth further exploration in additional research.

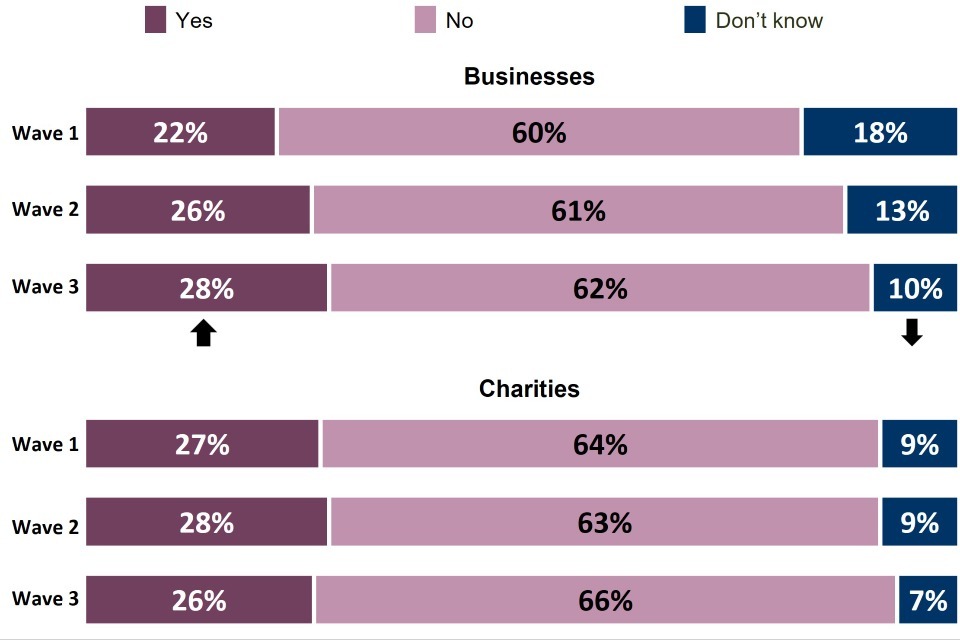

Broadly speaking, approximately one-quarter of organisations (28% of businesses and 26% of charities, comparable to previous waves of the survey) have measures in place to evaluate the quality of their suppliers’ cyber security measures. This is a clear area for organisations to improve as it poses a significant gap in organisations’ cyber resilience profile.

Overall, of these measures, there is a clear trend between business size and the sophistication of their approach to cyber security. For example, very large businesses (500+ employees) are nearly twice as likely as businesses overall to adhere to the Cyber Essentials Plus standard (16% vs. 9%) and are much more likely to have put in place all five technical controls required to attain Cyber Essentials (79%, compared to 62%). This is likely a reflection of the greater resources that these businesses are able to dedicate to managing their cyber resilience.

Organisations that have a cyber security certification often have further checks in place on cyber security. For example, organisations that adhere to a cyber security certification are more likely to report having completed a supplier cyber security risk assessment in the last twelve months. This suggests that firms that seek a cyber security accreditation also take a wider more holistic approach to their security either through necessity or choice.

Board involvement

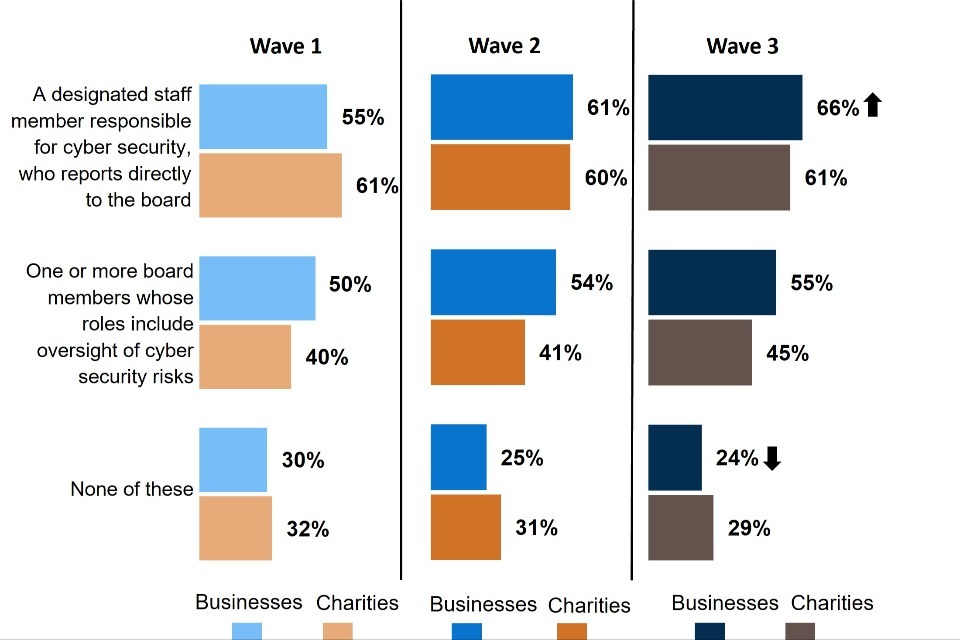

To ensure that organisations can maintain high levels of cyber resilience, it is vital that senior staff buy into the importance of cyber security. Indeed, there is some evidence that the presence of designated cyber responsibilities among senior staff is related to more robust cyber security processes. For example, around three-quarters (73%) of businesses and two-thirds (67%) of charities with one or more board members with oversight of cyber security have all five technical controls required to attain Cyber Essentials in place.

In Wave Three, approximately half of organisations (55% of businesses, 45% of charities) have a member on their board responsible for oversight of cyber security. More organisations (66% of businesses, 61% of charities) have a staff member that is responsible for cyber security that reports to the board. Among businesses this is an increase on Wave One (55%) but is comparable to Wave Two (61%).

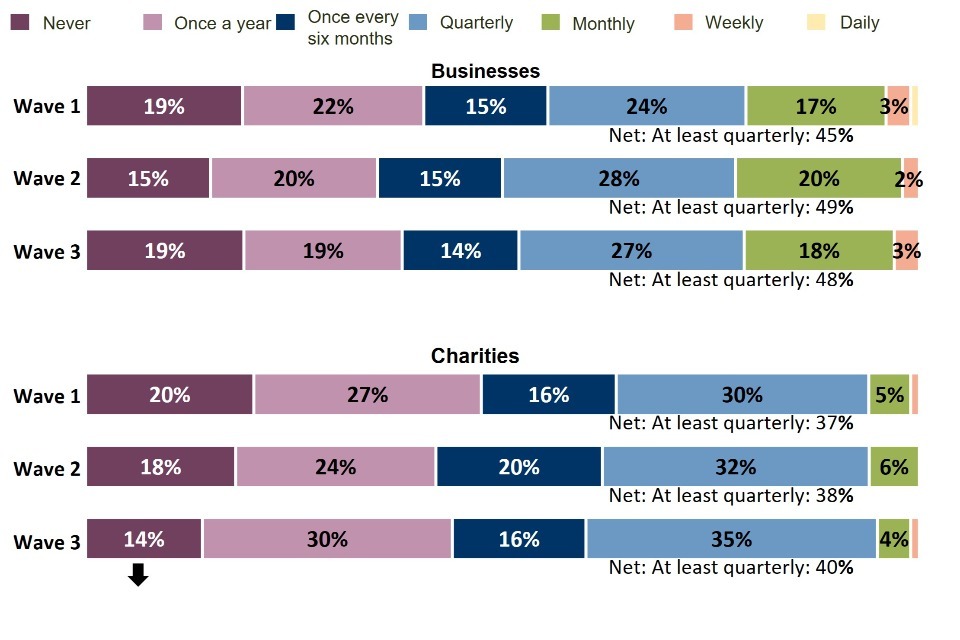

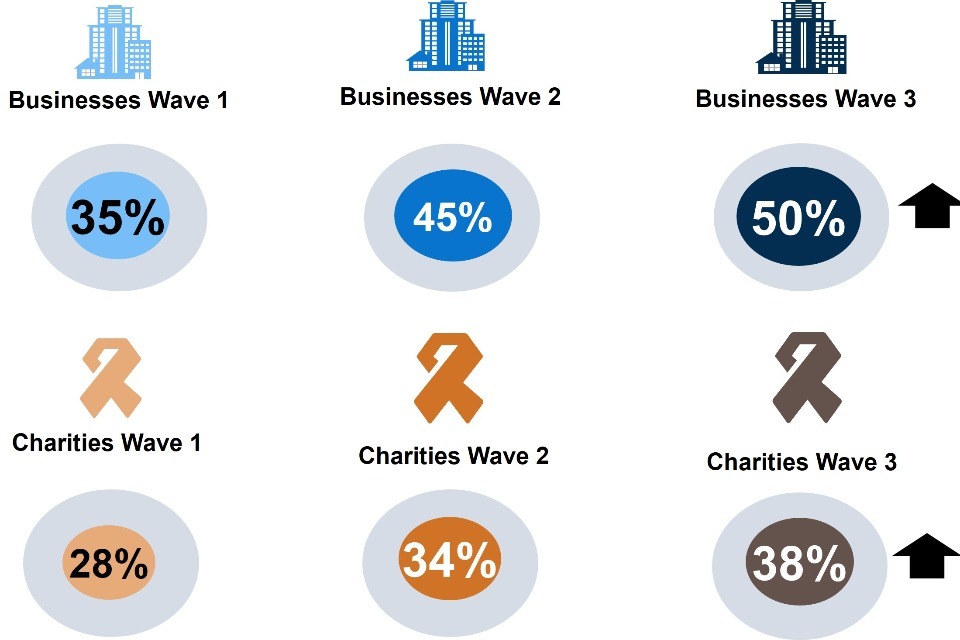

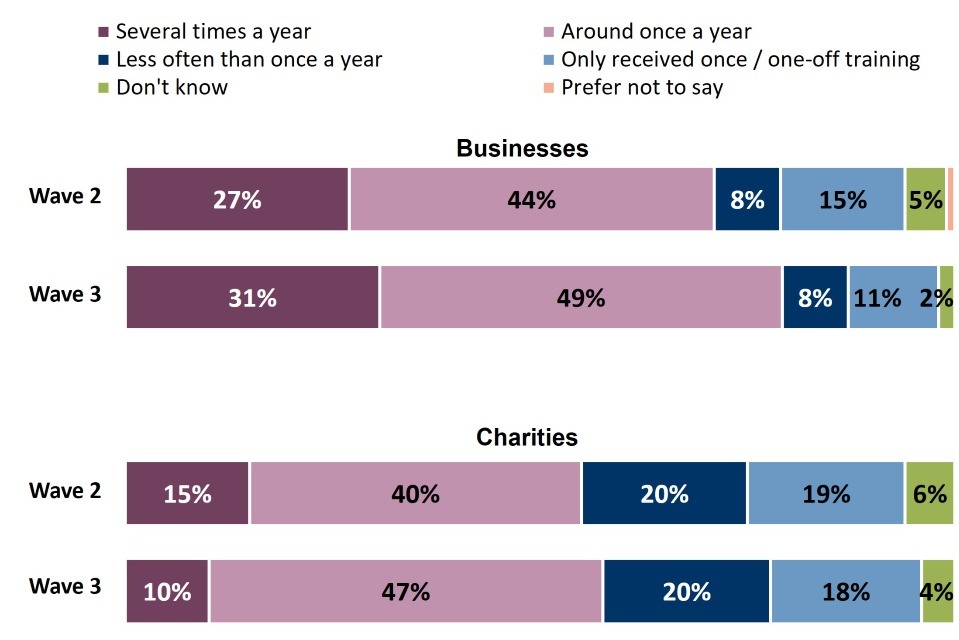

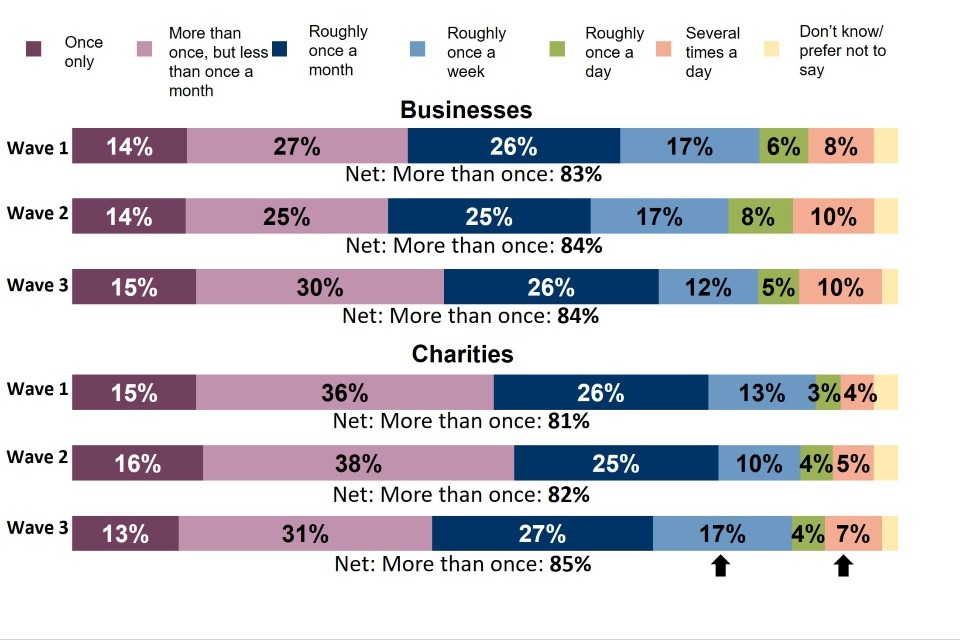

Further to this, board-level cyber security training has increased for both businesses (50% in Wave Three compared to 35% in Wave One) and charities (38% in Wave Three compared to 28% in Wave One) but has remained consistent between Wave Two and Three. This training is most likely to be completed once a year, although for around one-third (31%) of businesses this board-level training happens several times a year.

While this suggests that the majority of organisations understand the value of cyber security, it is important to note that the proportion of organisations reporting regular board-level cyber security discussions is quite low. Only 43% of businesses and 37% of charities’ boards discuss cyber security at least quarterly. Among businesses this has decreased in Wave Three (from 37% in Wave One) but has remained quite stable for charities. This suggests that improving regular board engagement remains a key area of focus to help improve cyber resilience.

Again, large businesses are more likely to have greater levels of board engagement. For example, 66% of very large businesses with 500+ employees report that their board has received cyber security training. This continues to suggest that larger businesses are able to take a more sophisticated approach to cyber security.

Sources of information

To ensure that organisations can remain informed of security best practice, it is important that they are able to access up to date and relevant information.

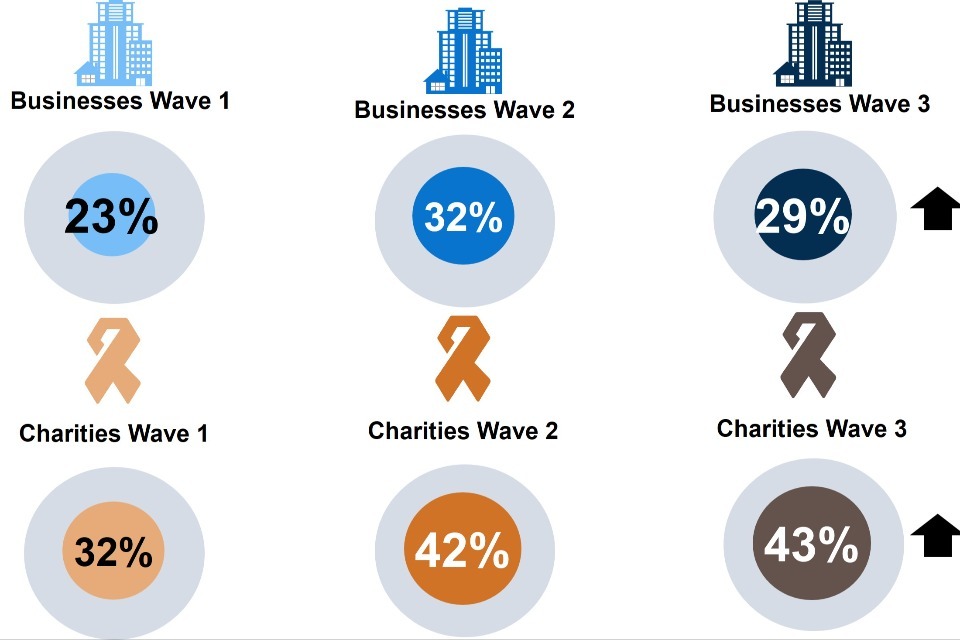

The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) provides a range of information resources for both businesses and charities[footnote 3]. Use of NCSC resources is more common among charities (43%) than businesses (29%). This represents an increase between Wave One and Wave Three for both businesses (29% in Wave Three vs. 23% in Wave One) and charities (43% in Wave Three vs. 32% in Wave One) but is comparable to Wave Two. The lower usage among businesses potentially reflects their greater resources and access to external consultants.

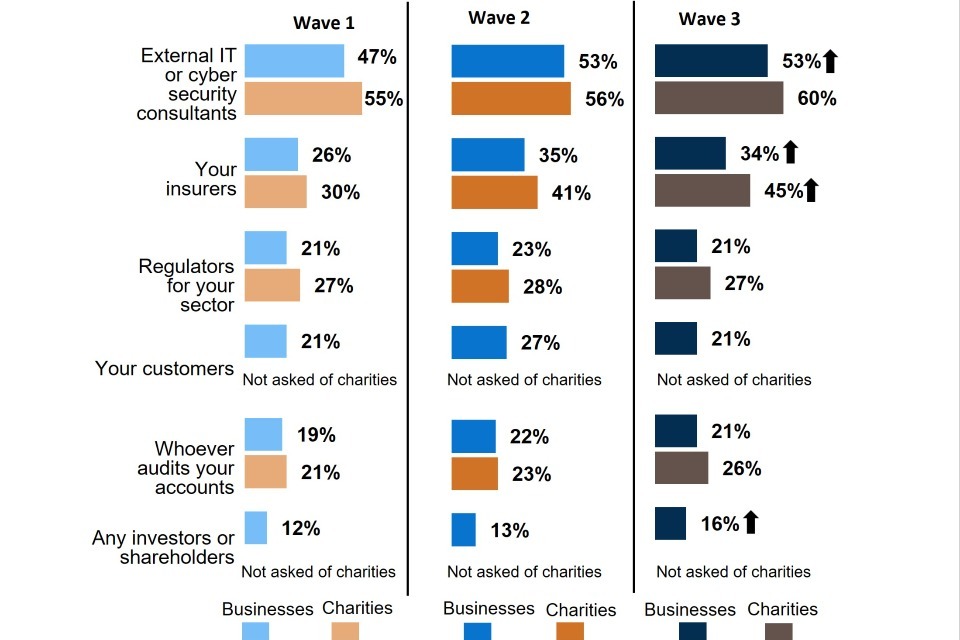

Indeed, businesses are also more likely to report being influenced by external consultants since Wave One (53% vs. 47%). However, there is little change between Wave Two and Wave Three.

Since Wave One, more businesses (34% in Wave Three vs. 26% in Wave One) and charities (45% vs. 30%) report their actions on cyber security being influenced by their insurers.

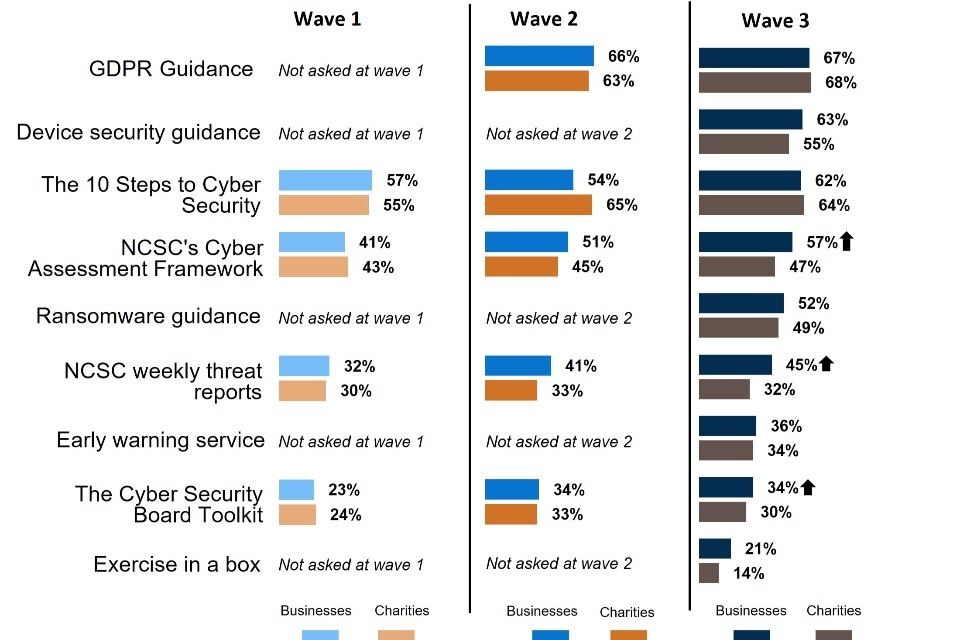

Among those organisations that use NCSC information or guidance, for both businesses and charities, the most common guidance accessed is General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) guidance (by 67% of businesses and 68% of charities), followed by the ‘“10 Steps to Cyber Security’ (by 62% of businesses and 64% of charities). This is consistent with previous waves of the survey.

In addition to this, among businesses, there has been an increase in usage of the Cyber Assessment Framework (57% in Wave Three vs. 41% in Wave One), NCSC weekly threat reports (45% vs. 32%), and Cyber Security Board Toolkit (34% vs. 23%).

Cyber incident management

Part of building organisations’ cyber resilience also relates to the management processes they have put in place for when a cyber incident happens.

A majority of organisations have a written procedure in place for responding to cyber security incidents (59% of businesses, 56% of charities). Among businesses, this represents an increase compared to Wave One (59% in Wave Three compared to 51% in Wave One), though it has remained consistent since Wave Two. For charities, there has been little change between waves of the survey. This suggests that there is still space for these management processes to become more formalised among charities in future.

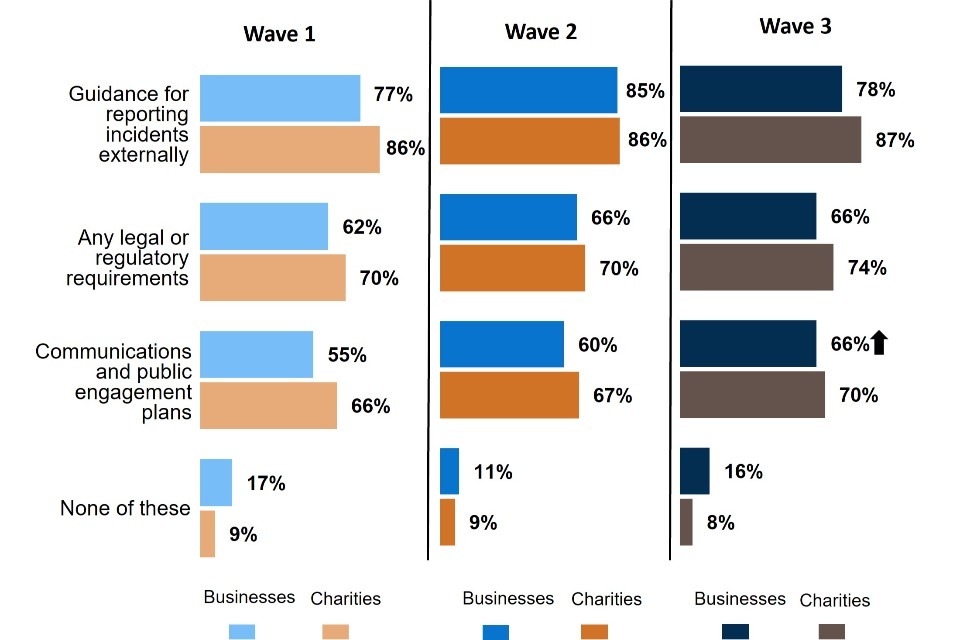

Among those organisations that have written incident management procedures, the most common security area covered is guidance for reporting incidents externally (78% among businesses, 87% among charities). For businesses, this represents a decrease when compared to Wave Two (78% in Wave Three vs. 85% in Wave Two) but is in line with Wave One. There is also an increase in the proportion of businesses that have a communications and public engagement plan in place (from 55% in Wave One to 66% in Wave Three). For charities, the results in Wave Three are roughly comparable to previous waves of the survey.

Approximately half of businesses (46%) have tested their incident response policies within the last twelve months. This represents an increase from Wave One (46% vs. 37%). Around one-third of charities (34%) have tested their policies, which is in line with previous waves.

Prevalence and impact of cyber security incidents

Beyond simply getting a sense of organisations’ cyber incident response processes, it is also important to understand the prevalence of these incidents and the impact that they can have on organisations.

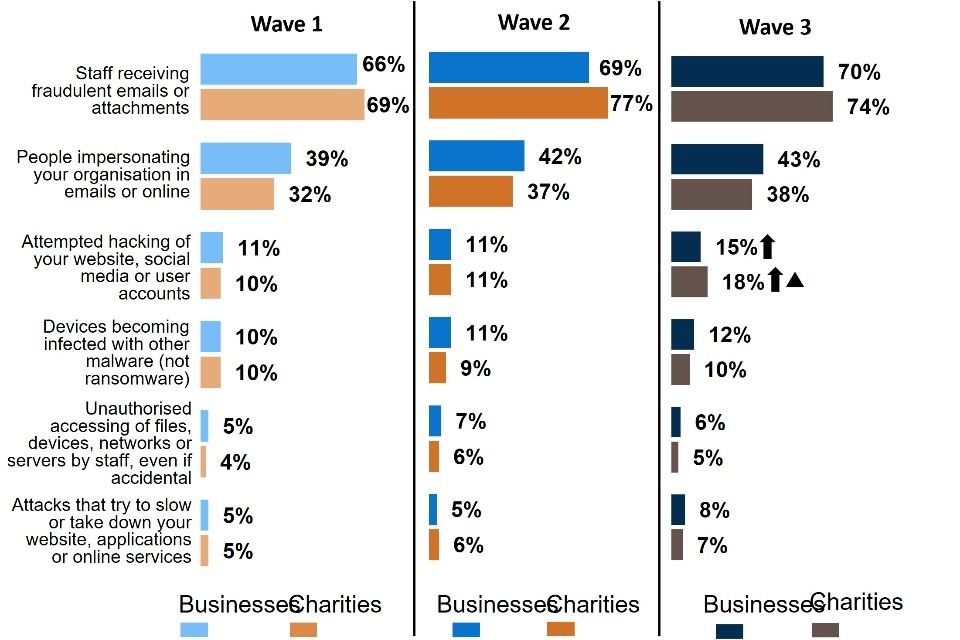

Three-quarters of businesses (75%) and around eight in ten charities (79%) have experienced a cyber security incident within the last twelve months. These findings are comparable across the three waves of the survey.

Despite this, the underlying data does show some change between waves. A higher proportion of charities experienced an attempted hacking of their website or social media accounts compared to Wave Two (18%, up from 11%). The equivalent proportion from businesses remained consistent across waves.

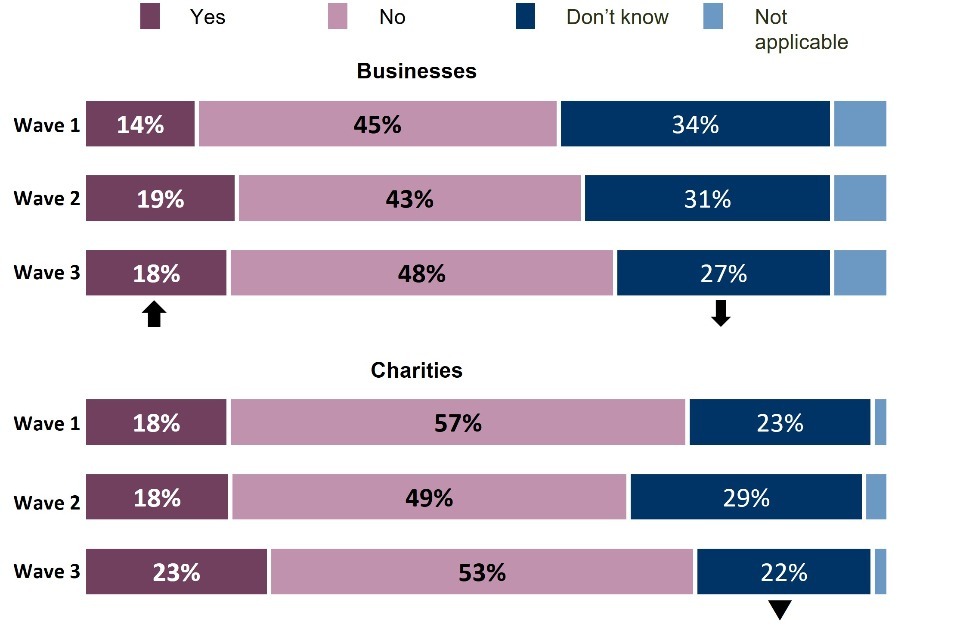

With regards to ransomware, the proportion of businesses that do not have a ransomware policy in place or are not sure whether they had one in place remained consistent with Wave Two. However, the proportion of charities who are unsure if a ransomware policy exists decreased in comparison to Wave Two (22% vs. 33%).

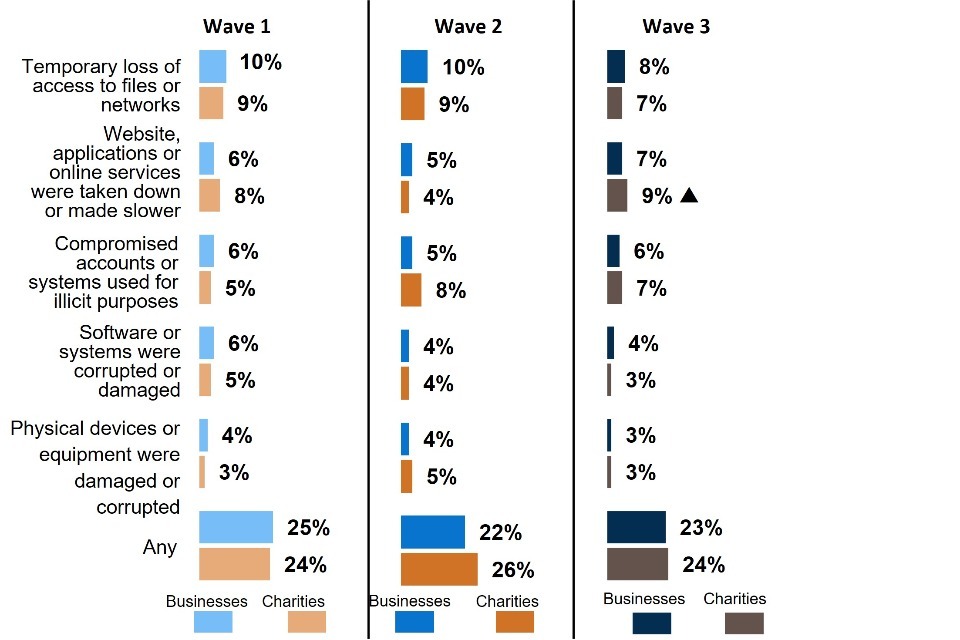

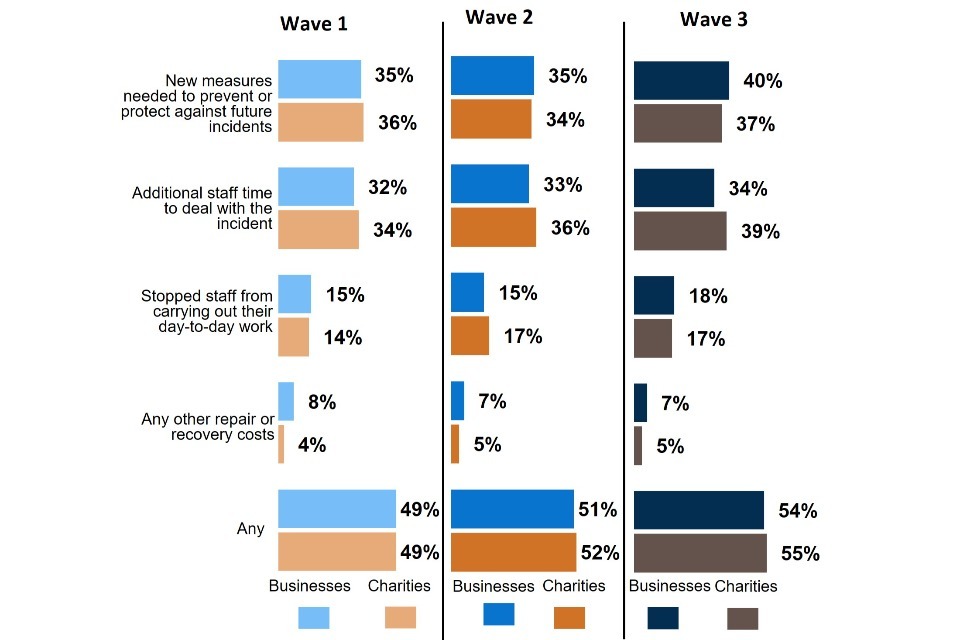

Broadly, organisations reported that most cyber security incidents only rarely cause a material loss (e.g., money or data). Only around one-quarter of businesses (23%) and charities (24%) experiencing incidents in the last year report material consequences. Further to this, most of these losses are short-term. Despite this, it is important to note that cyber incidents still have the potential to cause significant costs for organisations.

Longitudinal analysis

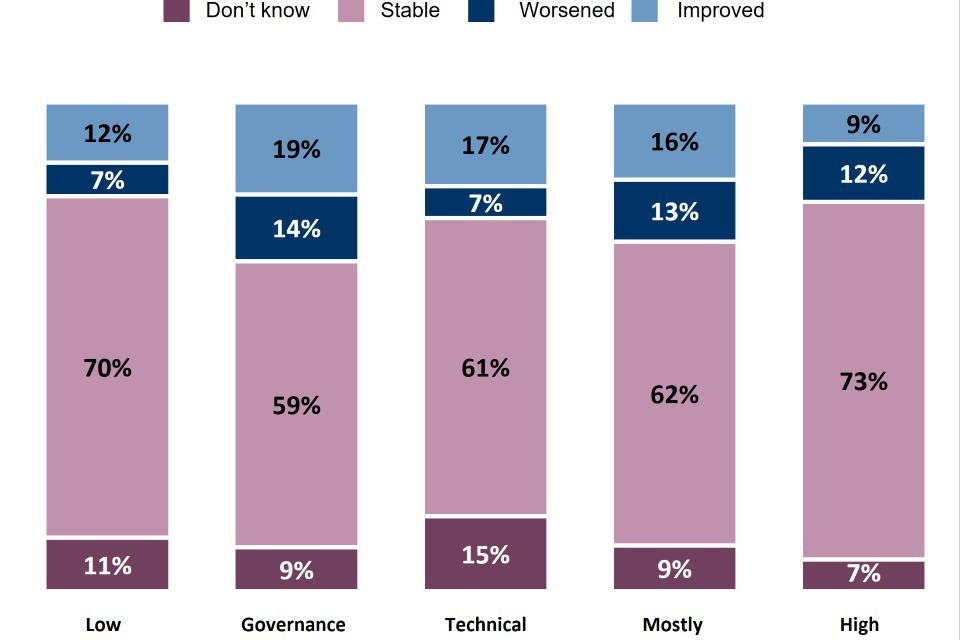

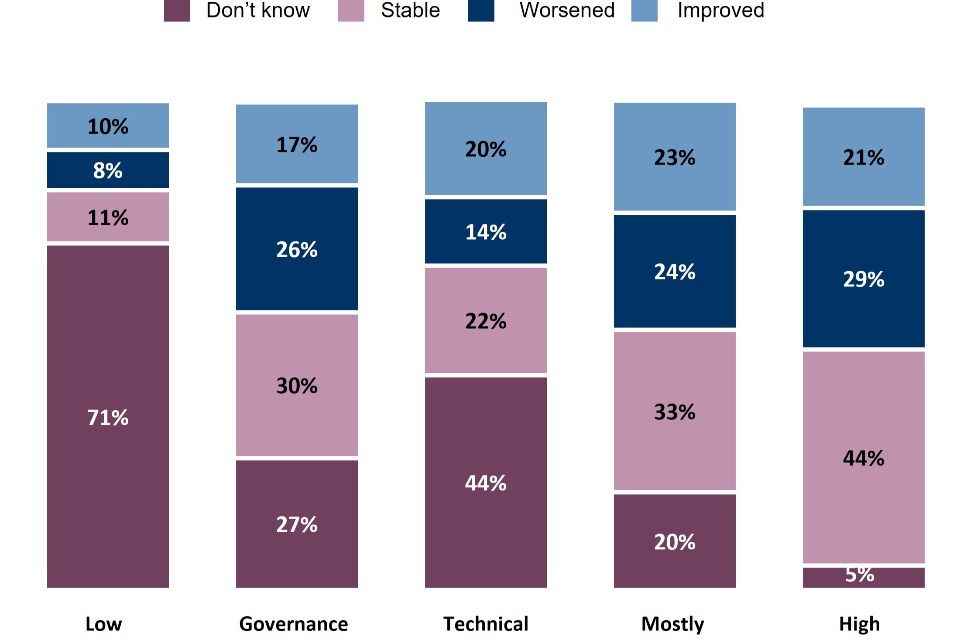

The longitudinal analysis is comprised of three components. First, a segmentation technique was used to group together organisations that used similar patterns of protective behaviours, policies and processes. It identified five distinct groups of organisations according to a combination of the number and types of protective practices used. The segmentation is based on robust cyber resilience requiring the adoption of technical and governance policies, procedures and tools to protect against incidents and mitigate impacts and outcomes. The five groups identified are:

- High level of preparation: protection well above the average level on all activities.

- Mostly prepared: mostly above average protection on all items but to a lesser extent than those in the ‘high’ level group.

- Governance led: protection was around or above average for policy and procedures but low on technical responses.

- Technical led: tended to have had recent improvements in network security, malware defence, authentication and secure backup but lower than average governance.

- Low level of preparation: protection was low across all activities, except secure cloud backup.

Patterns of cyber security resilience were found to vary across organisations with some organisations using many practices, others few; some organisations rely more on governance procedures and others on technical practices.

The pathways of cyber resilience are not one way. Some organisations take a step back and lower their levels of resilience, others take a step forward and many remain at stable levels.

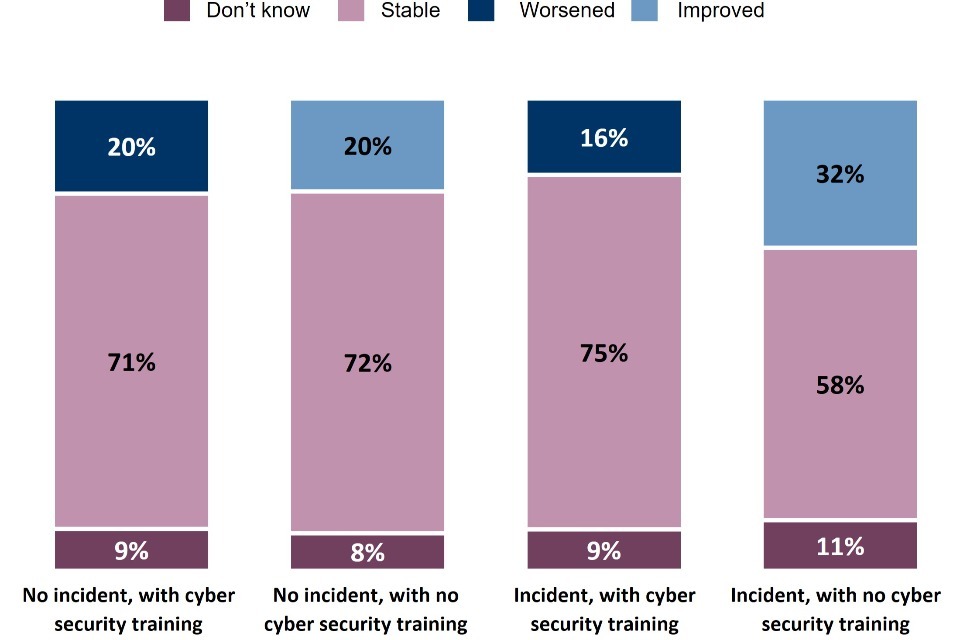

There is some evidence supporting the hypothesis that experiencing a cyber security incident acts as a trigger for improving resilience. However, this is not true for all organisations, as some experience an incident and show no change in their resilience or become less resilient. More needs to be known about the context and other factors influencing protective behaviours alongside experience of cyber incidents.

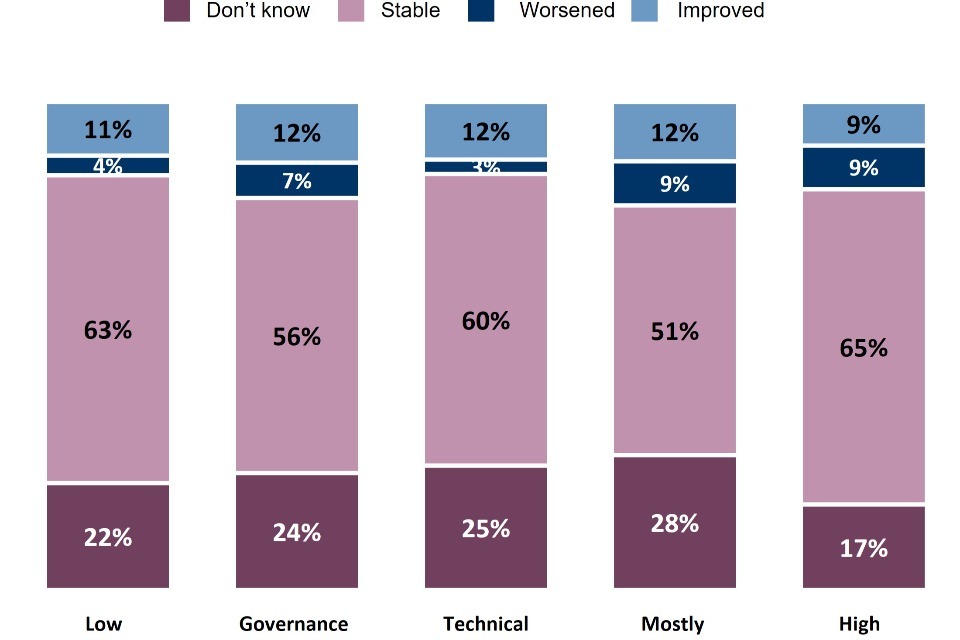

The second aspect of the longitudinal analysis looked at adherence to cyber security certifications or standards. The analysis found that:

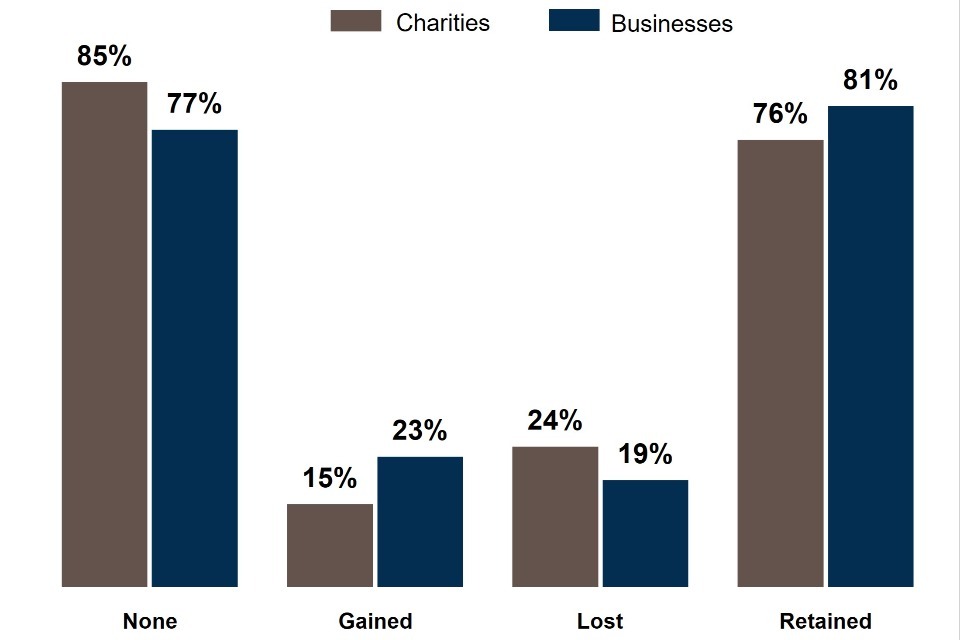

- Adherence to cyber security certifications or standards is quite low.

- Adoption of adherence to certifications or standards is most prevalent amongst those with stronger patterns of resilience than those with less resilient protection. Similarly, losing adherence to accreditations or standards was less likely among more resilient organisations.

- Businesses are more likely than charities to retain their adherence to accreditations or standards but no more likely to take up certifications.

- Experience of a cyber security incident appears to trigger either a take-up of adherence to certifications or standards or retention of these, albeit among a minority of organisations.

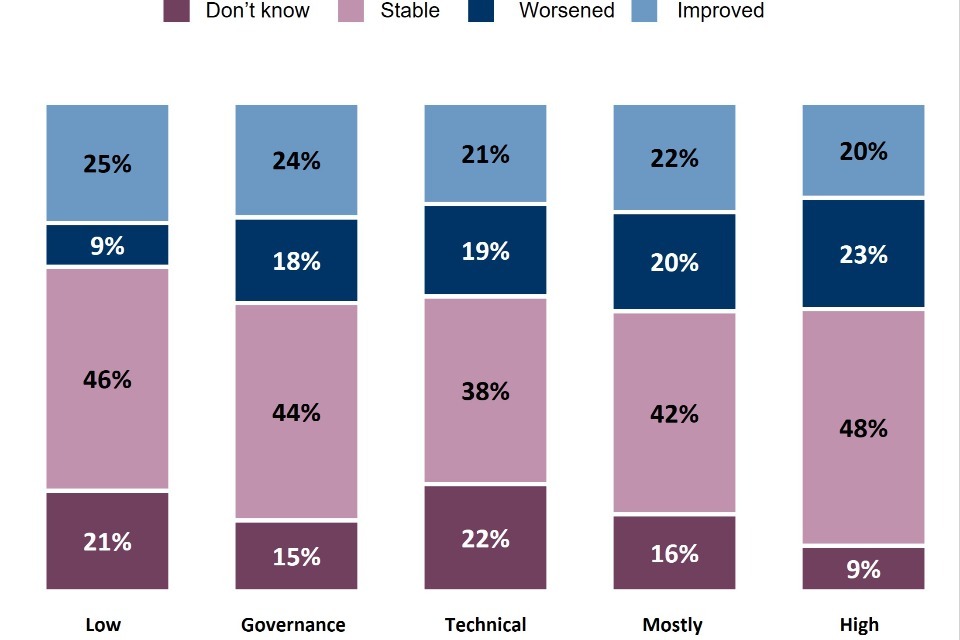

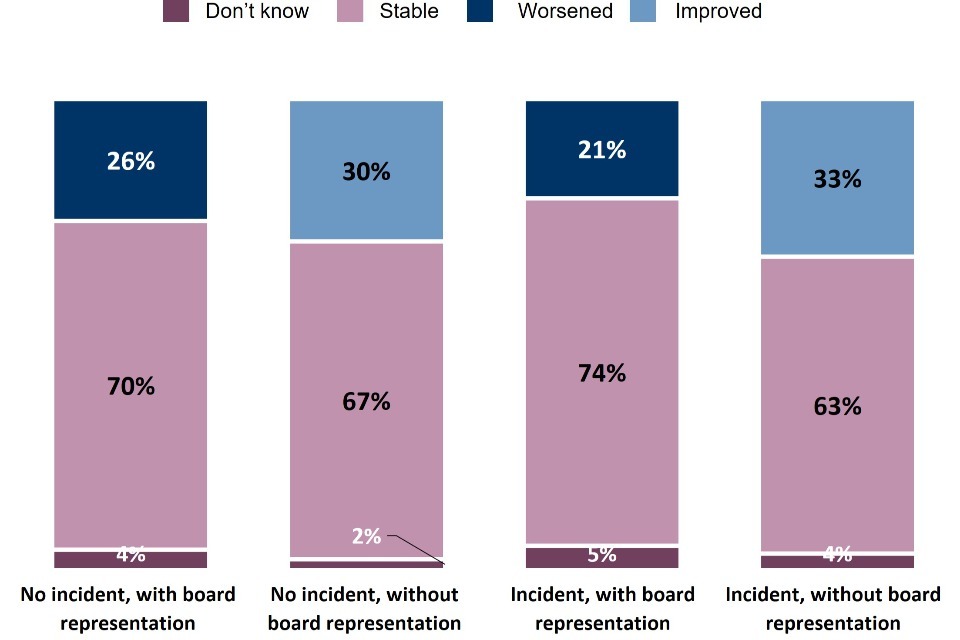

The third and final part of the longitudinal analysis covered board representation. The main findings include:

- Various board activities supporting cyber resilience exist, but substantial numbers of organisations do not appear to have much, if any, board engagement across these activities.

- Board engagement involves both negative and positive steps but generally the trend is towards more engagement over time (i.e., in the follow-up wave interview). Improvement is more apparent for organisations with lower patterns of cyber resilience.

- The experience of cyber security incidents again appears to trigger adoption of board activities and/or a lower rate of negative change in board engagement, although only for a minority of organisations that experience such incidents.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Baseline survey | Also see Wave One survey. The first research year of the survey that took place. |

| Cloud computing | Cloud computing uses a network of external servers accessed over the internet, rather than a local server or a personal computer, to store or transfer data. This could be used, for example, to host a website or corporate email accounts, or for storing or transferring data files. |

| Cyber attack | A cyber attack is a malicious and deliberate attempt by an individual or organisation to breach the information system of another individual or organisation. |

| Cyber profile | A cyber profile is a baseline set of minimal cyber security requirements for mitigating described threats and vulnerabilities, as well as supporting compliance requirements for a defined scope and type of a particular use case (e.g., industry, information system(s)), using a combination of existing cyber security guidance, standards and/or specifications baseline documents or catalogues. |

| Cyber security | Cyber security includes any processes, practices or technologies that organisations have in place to secure their networks, computers, programs or the data they hold from damage, attack or unauthorised access. |

| Impact | A negative impact on organisations did not have to involve a material loss. This could be issues relating to staff disruption or implementing new measures in the organisation. |

| Large business | Businesses with 250 employees or over. |

| Longitudinal survey | A longitudinal survey is a research design that involves repeated observations of the same variables (e.g., people or businesses) over short or long periods of time. |

| Malware | Malware (short for “malicious software”) is a type of computer program designed to infiltrate and damage computers without the user’s consent (e.g., viruses, worms, Trojan horses etc). |

| Managed Service Provider (MSP) | A supplier that delivers a portfolio of IT services to business customers via ongoing support and active administration, all of which are typically underpinned by a Service Level Agreement. A Managed Service Provider may provide their own Managed Services or offer their own services in conjunction with other IT providers’ services. |

| Medium business | Businesses with 50 to 249 employees. |

| Outcome | A negative outcome of an attack involved a material loss from an organisation, such as a loss of money or data. |

| Patch management | Having a policy to apply software security updates within 14 days of them being released. |

| Penetration testing | Penetration testing is where staff or contractors try to breach the cyber security of an organisation on purpose, in order to show where there might be weaknesses in cyber security. |

| Personally-owned devices | Personally-owned devices are things such as smartphones, tablets, home laptops, desktop computers or USB sticks that do not belong to the company but might be used to carry out business-related activities. |

| Phishing | Fraudulent attempts to extract important information, such as passwords, from staff with infiltration through a link or attachment sent via email. |

| Ransomware | A type of malicious software designed to block access to a computer system until a sum of money is paid. |

| Removable devices | Removable devices are portable things that can store data, such as USB sticks, CDs, DVDs etc. |

| Restricting IT admin and access rights | Restricting IT admin and access rights is where only certain users are able to make changes to the organisation’s network or computers, for example to download or install software. |

| Security breach | A security breach is any incident that results in unauthorised access of data, applications, services, networks and/or devices by bypassing their underlying security mechanisms. |

| Smart devices | Network connected devices, like personal assistants, locks, alarms, or thermostats. |

| Social engineering | Fraudulent attempts to extract important information, such as passwords, from staff with infiltration through an impersonation attempt of the organisation. |

| Threat intelligence | Threat intelligence is where an organisation may employ a staff member or contractor or purchase a product to collate in*formation and advice around all the cyber security risks the organisation faces. |

| Two-factor authentication | Two-Factor, or Multi-Factor, Authentication is an electronic authentication method in which a user is granted access to a network or application only after successfully presenting two or more pieces of evidence to an authentication mechanism (e.g., a password and a one-time passcode). |

| Wave one survey | Also see Baseline survey. The first research year of the survey that took place (2021). |

| Wave two survey | The second research year of the survey that took place (2022). |

| Wave three survey | The third research year of the survey. This is the current survey year (2023). |

Chapter 1 – Introduction

1.1 Background to the research

Publication date: 20 March 20 2023

Geographic coverage: United Kingdom

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) commissioned the Cyber Security Longitudinal Survey of medium and large UK businesses (50+ employees) and high-income charities (annual income of more than £1m) as part of the National Cyber Security Programme. The findings will evaluate long-term links between the cyber security policies and processes adopted by these organisations, and the likelihood and impact of a cyber incident. It also supports the government to shape future policy in this area, in line with the National Cyber Strategy 2022 and will inform future government cyber interventions and support future strategies with quality evidence.

This report is based on Wave Three (2023) of a multi-year study. This study has collected longitudinal data from 2021 (Wave One) and 2022 (Wave Two). Due to the longitudinal nature of the study, the aim is to track trends over time and speak largely with the same organisations in each wave. The design of this research was influenced by a study the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) previously commissioned to investigate the feasibility of creating a new longitudinal study of large organisations.

The core objectives of this study are to:

- Explore how and why UK organisations are changing their cyber security profile and how they implement, measure, and improve their cyber defences.

- Provide a more in-depth picture of larger organisations, exploring topics that are covered in less detail in the Cyber Security Breaches Survey (CSBS), such as corporate governance, supply chain risk management, internal and external reporting, cyber strategy and cyber insurance.

- Explore the effects of actions adopted by organisations to improve their cyber security on the likelihood and impact of a cyber incident.

1.2 Difference from the Cyber Security Breaches Survey

This study differs from the CSBS in multiple important respects. Firstly, it uses a longitudinal approach, where the aim is to track changes in cyber resilience over time, whereas the CSBS uses a cross-sectional sample that provides a snapshot of cyber resilience. This three-year longitudinal study collects data from the same unit (businesses or charities) on more than one occasion (up to three points in time), to analyse the link between large and medium organisations’ cyber security behaviours and the extent to which they influence the likelihood and impact of experiencing an incident over time. In comparison, results from CSBS track changes over time, and provides a static view of cyber resilience at a given time.

Secondly, this survey focuses only on medium, large and very large businesses, and high-income charities whereas the CSBS includes all businesses (micro, small, medium, and large), all charities, and educational institutions. Additionally, different questions are used, so while there are some similarities in the questions and topics covered by the two surveys, results are not comparable.

The CSBS is an official government statistic, and representative of all UK businesses, charities, and educational institutions. Therefore, for overall statistics on cyber security, results from CSBS should be used. Further detail on overlapping questions can be found in the Cyber Security Longitudinal Survey Wave Three Technical Report.

Please visit the gov.uk website to see publications of the Cyber Security Breaches Survey.

1.3 Methodology

There are two strands to the Cyber Security Longitudinal Survey. First, Ipsos undertook a random probability multimode[footnote 4] (telephone and online) survey covering 542 businesses and 310 UK registered charities between March and June 2023[footnote 5]. Of these, 786 interviews (92%) were completed via telephone and 66 interviews (8%) were completed through the online survey option. The data for businesses and charities have been weighted to be statistically representative of these two populations. Subsequently, 30 in-depth interviews were conducted in June and July 2023, to gain qualitative insights from some of the organisations that participated in the quantitative survey.

This longitudinal study tracks changes over time by following the same organisations in all three annual waves. In Wave Two, 899 organisations (599 businesses and 300 charities) agreed to be recontacted in Wave Three. All of these organisations were contacted again for Wave Three (2023). This constitutes the majority of completed interviews; 53% (451 interviews) of completed interviews in Wave Three were part of the longitudinal sample, comprising 280 interviews with businesses and 171 with charities. In contrast, 47% (401 interviews) of the achieved sample in Wave Three came from fresh sample, comprising 262 interviews with businesses and 139 with charities.

The Wave Three sample included seventeen interviews with businesses that were eligible (had 50 or more employees) when first interviewed in a previous wave but had dropped below this figure since then.

In addition to the organisations that had participated in the study in previous years, the survey was issued to businesses and charities that had not taken part previously. This allowed the survey to maintain a strong overall achieved sample size and as such ensure that robust analysis could be completed from this research. To avoid possible selection bias, the ‘fresh’ business sample was selected using random probability sampling. The business sample was proportionally stratified by region, and disproportionately stratified by size and sector.

More technical details, including methodological notes for the longitudinal analysis, and a copy of the questionnaire, are available in the separately published Technical Annex.

Profile of survey respondents

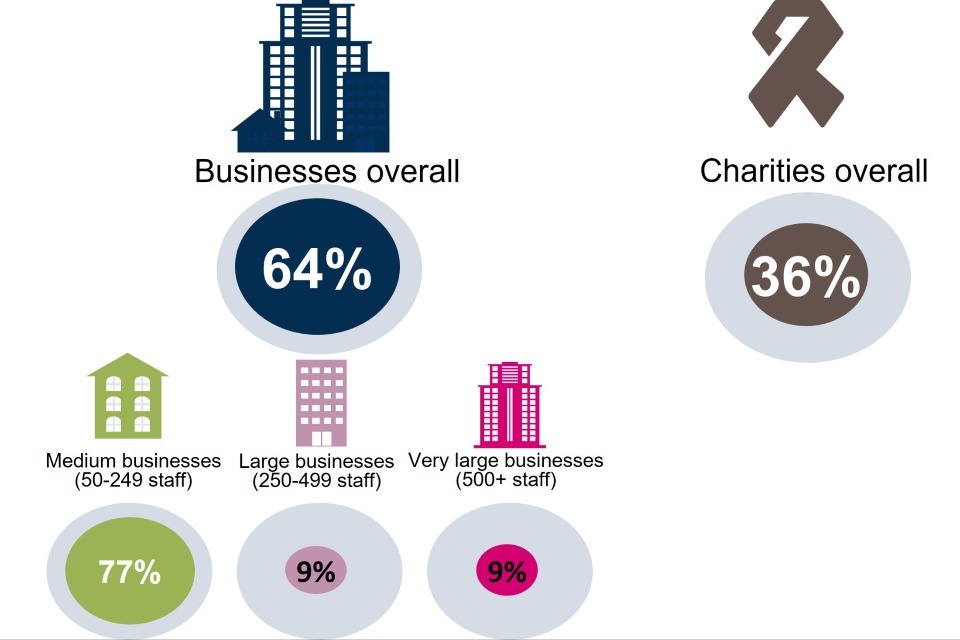

Figure 1.1: Businesses and charities overall and by business size (showing weighted %)

Percentage of the sample that were businesses, split by size, and charities.

Base: All businesses (n=542); Medium businesses (n=302); Large businesses (n=100); Very large businesses (n=123), includes 17 businesses in the longitudinal sample confirmed as eligible in previous waves but now with fewer than 50 employees and one business in the longitudinal sample that could not confirm their current number of employees; All charities (n=310).

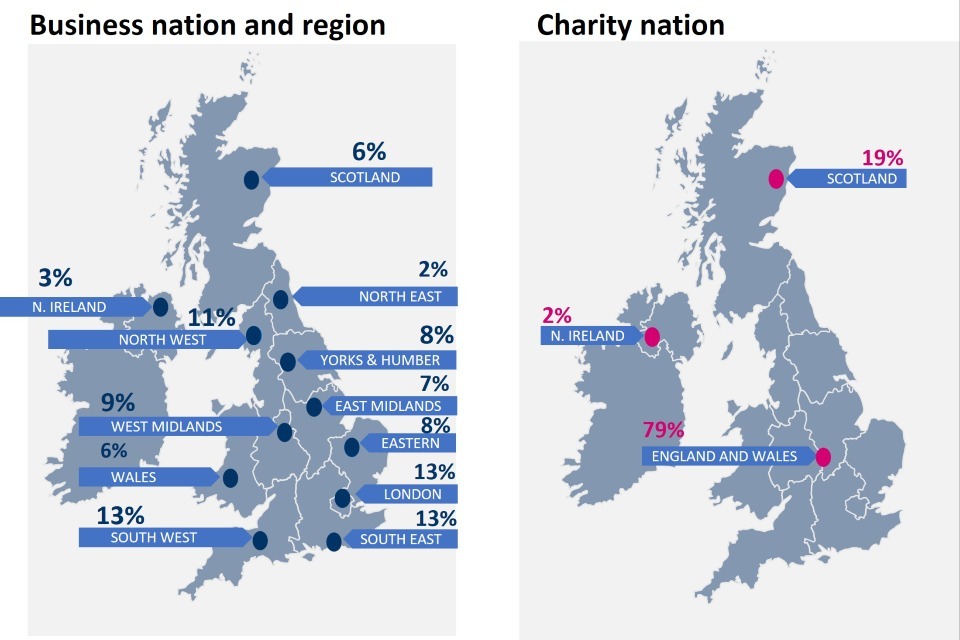

Figure 1.2: Businesses and charities by nation and region (showing weighted %)

The distribution of responding businesses and charities by UK nation and region

Base: All businesses (n=542); All charities (n=310). Businesses in East Midlands (n=37); Eastern England (n=48); London (n=65); North East (n=12); North West (n=58); Northern Ireland (n=21); Scotland (n=36); South East (n=67); South West (n=62); Wales (n=33); West Midlands (n=52); Yorkshire and Humber (n=51); Charities in England and Wales (n=244); Northern Ireland (n=7); Scotland (n=59).

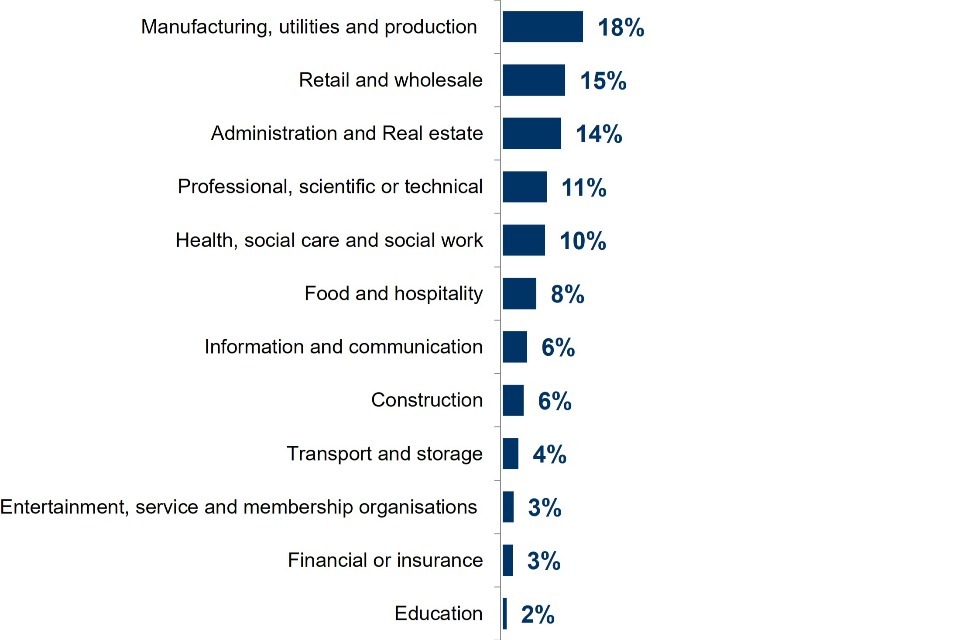

Figure 1.3: Businesses by sector (showing weighted %)

Distribution of responding businesses by sector

Base: All businesses (n=542); Administration and real estate (n=89); Construction (n=42); Education (n=16); Entertainment, service and membership organisations (n=12); Finance and insurance (n=15); Food and hospitality (n=56); Health, social care and social work (n=40); Information and communication (n=31); Manufacturing, utilities and production (n=116); Professional, scientific and technical (n=29); Retail and wholesale (n=73); Transport and storage (n=23).

Profile of qualitative respondents

Thirty follow-up interviews were carried out with representatives of organisations covered by the survey. They were selected in order to provide the following profile:

Table 1.1 Profile of qualitative respondents

| Category | Definition | Achieved |

| Type | Businesses | 20 |

| Charities | 10 | |

| Size (employees):(Businesses only) | Medium (50-249) | 7 |

| Large (250-499) | 5 | |

| Very large (500+) | 8 | |

| Sector (Businesses only) | Broad mix of sectors | 20 |

| Region (Businesses only) | Broad mix of regions | 20 |

Cyber security roles and responsibilities

Where possible both the survey and follow-up qualitative interviews were addressed to the person at each organisation with greatest responsibility for cyber security. However, in many organisations there is nobody with specific responsibility for cyber security so, in these cases, interviews were completed with representatives that took responsibility for various aspects of IT and data security. This was particularly the case within organisations that do not have an in-house IT department.

There are variations by sector but in general large businesses (especially ‘very large’ enterprises) are the most likely to have employees with dedicated IT and cyber security roles, as well as teams associated with these areas. This can be the case for many medium-sized businesses and charities, but often these smaller organisations fully outsource the management of IT and cyber security.

Respondents with a general, or less technically specific role, tended to have lower awareness of cyber security issues. Meanwhile people at organisations where the cyber security role is combined with other responsibilities are often stretched. As a result, they may not be able to give cyber security matters as much attention as they would like.

1.4 Interpretation of findings

The survey results are subject to margins of error, which vary with the size of the sample and the percentage figure concerned. For all percentage results, subgroup differences by size, sector and other survey answers have only been highlighted where they are statistically significant[footnote 6] (at the 95% level of confidence).

There is a guide to statistical reliability at the end of this report.

Subgroup definitions and conventions

For the purposes of analysis, businesses are divided into medium (50-249 employees) and large enterprises (250+ employees)[footnote 7]. In turn large businesses consist of both large (250-499 employees) and very large businesses (500+ employees). All charities included in the survey have a reported annual income of at least £1 million according to national charity regulator sample data [footnote 8].

Where figures are marked with an asterisk (*) these refer to base sizes smaller than 50 and should be treated with caution.

1.5 Acknowledgements

Ipsos and DSIT would like to thank all the organisations and individuals that participated in the survey. We would also like to thank the organisations that endorsed the fieldwork and encouraged businesses and charities to participate, including:

- The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC)

- The Home Office

- The Scottish Government

- The Charity Commission

Chapter 2 – Cyber profile of organisations

The development of technology in recent years has significantly shifted how people work. This has included the rise of remote working and the use of remote or cloud storage, all of which have forced organisations to adapt their cyber security requirements to this new environment.

This chapter summarises the extent to which organisations make use of different types of data storage and the methods that employees use to access data from work. It also outlines the extent to which businesses and charities deploy cyber security tools that use AI or machine learning, along with the use of external IT suppliers or consultants.

The ways in which organisations currently store and allow access to data show minimal changes from those reported in Wave One and Wave Two: As in previous waves of the survey, almost every business and charity (96% and 98% respectively in Wave Three) has a cloud or physical server to store data or uses a virtual private network (VPN) that allows staff to connect remotely. However, physical servers are increasingly less likely to be used, both by businesses (76% in Wave Three vs. 82% in Wave One) and charities (60% vs. 72%).

While more prevalent among charities (56% vs. 35% of businesses), the proportion of organisations that allow staff to access their network or files through personally owned devices is in line with previous waves.

The proportion of businesses (81%) and charities (69%) that require staff to use their VPN for remote access remains similar across waves and continues to be high.

For both businesses (23%) and charities (16%), the proportion employing AI or machine learning within their cyber security tools remains low in line with previous waves.

2.1 Data storage and access

In response to their workforces’ changing needs, businesses and charities have had to reconsider the ways in which their data is stored and accessed. In particular, Virtual Private Networks (VPN) have become a critical part of organisations’ cyber security given the rise of remote working and concerns around access of sensitive data.

As in previous waves of the survey, almost all businesses (96%) and charities (98%) have one or more of a cloud or physical server to store data or use a virtual private network (VPN) that allows staff to connect remotely.

Businesses remain more likely than charities to use physical servers (76% vs. 60%) and a VPN that allows staff to connect remotely (75% vs. 58%). In contrast, charities are more likely than businesses to store data or files in the cloud (86% vs. 72%).

While the overarching patterns in each wave have remained similar over time, there have been some changes since the Wave One survey. The use of physical servers is now lower than at Wave One among both businesses (76% compared with 82%) and charities (60% compared with 72%). Charities are also less likely to have a VPN than they were at Wave One (58% compared with 66%) but are now more likely to use a cloud server (86% compared with 77%). These trends have shifted consistently over the three years covered by this survey.

Figure 2.1: How organisations store or access their data and files

Does your organisation use or provide any of the following?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle.

2.2 Use of personal devices to access organisation’s network or files

The COVID-19 pandemic led many organisations to review their remote working capabilities and ensuring that employees can access sensitive data securely has become an important organisational need.

As in previous waves of the survey, charities remain more likely than businesses to allow staff to access their organisation’s network or files through personally owned devices. A majority of charities (56%) allow this, compared to around one in three businesses (35%). Findings are in line with Wave One and Wave Two.

Although correlation does not imply causation, those organisations that allow staff to access their network via personal devices are more likely to have experienced a data security incident in the past twelve months. This pattern was reported at Wave Two, and still applies at Wave Three with regards to charities. Of those charities that have experienced an incident (other than ‘phishing’) in the past twelve months, 63% allow network access via personal devices. Where no incidents are reported, a lower share of charities (46%) allow access via personal devices.

Further to this, in Wave Three, both businesses and charities that have been impacted negatively by a cyber security incident were more likely to permit staff to access their network through personal devices (42% of businesses negatively affected by an incident allow access through personal devices compared to 31% that have not been affected; 63% of charities negatively affected by an incident allow access through personal devices compared 51% that have not been affected). This suggests that allowing access to personal devices, does have potentially harmful consequences for organisations.

Figure 2.2: Use of personal devices to access organisation’s network or files

Are staff permitted to access your organisation’s network or files through personally owned devices? (% Yes)

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). There are no significant changes between Wave One and Wave Three or between Wave Two and Wave Three. Among businesses with a VPN, about four in five (81%) require their staff to use it when accessing the organisation’s network or files from outside the workplace. Although the figure is lower, almost seven in ten charities with a VPN (69%) also require staff to use this when working remotely. Both figures are in line with previous waves of the survey.

Figure 2.3: Use of VPNs outside the workplace

Are staff permitted to access your organisation’s network or files through personally owned devices (e.g., a personal smartphone or home computer)?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=909) and at Wave 2 (n=525) and at Wave 3 (n=420); All charities at Wave 1 (n=354) and at Wave 2 (n=235), and at Wave 3 (n=179). There are no significant changes between Wave One and Wave Three or between Wave Two and Wave Three.

2.3 Use of AI and machine learning

AI is an important element of cyber security. Pattern recognition algorithms can be applied to network data flows to automate threat detection, benefitting organisations. Machine learning (a subset of AI) can also be used to support security measures by ensuring systems ‘remember’ and take account of any new patterns identified from recent incidents.

With around one in four businesses (23%) using AI or machine learning, they are more likely than charities (16%) to be using cyber security tools that include this technology. Neither of these shares has changed significantly since Wave One or Wave Two, suggesting that overall take up in AI is not rising despite the increasing capabilities of the technology.

The use of AI and machine learning is more prevalent in larger businesses, with those employing 250+ employees (32%) more likely than medium-sized enterprises (20%) to say it is a feature of their cyber security tools. Use of AI and machine learning is also more common among businesses that have a specific cyber security insurance policy (33% compared with 23% of businesses overall). This is likely also a result of size, as businesses with specific cyber security insurance are usually larger.

Organisations are more likely to report having cyber security tools that include AI and machine learning technology if they have all documentation for all five of the technical controls required to attain Cyber Essentials in place. This applies both to businesses (27% compared with 14% of businesses that do not have all five rules or controls in place) and charities (23% compared with 6%).

Figure 2.4: Use of AI or machine learning

Does your organisation deploy any cyber security tools that use AI or machine learning? (% yes)

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). There are no significant changes between Wave One and Wave Three or between Wave Two and Wave Three.

2.4 Use of external IT providers

Many businesses and charities do not have the resources available to them to adequately adjust their cyber security infrastructure. To help them with this adjustment, they can outsource their technology requirements to external IT providers. Further information on this can be seen in section 6.2.

Within the qualitative interviews, businesses and charities were asked whether they used external IT suppliers or cyber security consultants. The majority did, often contracting an organisation or individual for a broad package of IT support and consultancy, including cyber security. In some cases, organisations contracted external suppliers for specific tasks such as penetration tests, or for support with Cyber Essentials accreditation.

“We have a company that run our emails and our website…we use them because they have expertise in hosting, they have the infrastructure and time.”

Business, Medium, Utilities or production

“There was someone in-house to do all that and they left, so they needed someone to pick it up. This company were growing fast, they had a good reputation.”

Business, Very large, Food and hospitality

“We chose our IT provider in 2014, when IT was becoming more of a talking point, but before compliancy became such a big deal. We spoke to the one logistically that was better, and was local as we need to be reactive, for instance with physical hardware, dropping phones and laptops off quickly.”

Charity, England and Wales

Where external advice was used most extensively, this tended to reflect a lack of in-house resources or knowledge. In some instances, especially for smaller and less technically minded organisations, this was considered more cost-effective than developing or maintaining in-house expertise.

“I don’t know everything - I know what I know, and I know where the gaps in my knowledge are. I’ve written [applications] for the ISO 27001 three times, but I don’t know about programming or IDS/IPS.”

Business, Very large, Education

“It made financial sense to get external support, as and when required, rather than employing someone full time … it’s also out of ease.”

Business, Medium, Construction

The selection process for external consultants was quite mixed. Some organisations conducted a formal selection process when choosing a consultant, whereas others chose a consultant based on a recommendation or personal knowledge.

“We spent about seven months speaking to a number of companies. They were already doing some work for us, but not on the current scale. We went through a selection process … experiences, number of staff, response times, their security within their own company. We whittled it down to two companies - who we thought we could work best with. Cyber security was part of the discussion.”

Business, Large, Health, social care or social work

“A lot of this is nepotism. You know someone that knows someone that works in that industry … they may have worked here at some point.”

Business, Large, Information and communication

“We have an IT contractor who sorts out our limited usage of IT systems. They were recommended by a former colleague, as we needed somebody and we just went with it. There’s a lot of value in that personal recommendation.”

Business, Medium, Utilities or production

Typically, relationships with external consultants were characterised by a high level of trust. This was based on positive experiences of the service over previous years, a perception of a high level of expertise, and good personal relationships.

“They have been with us since day one … no plan to change them … we trust them.”

Business, Large, Food or hospitality

“I suppose, I should not trust them … but because I ask them a lot of questions and they provide me with the correct answer, I trust them …. you also get a vibe when you meet people… if you feel uneasy about people, you just don’t work with them.”

Business, Very large, Utilities or production

“Great relationship, never let us down… full trust.”

Business, Medium, Construction

Chapter 3 – Cyber security policies

In a fast-developing space, it is increasingly essential that businesses have clear cyber security policies to ensure they remain secure from potential cyber threats. Improvements in governance and documentation, as well as insurance, will help organisations to build their cyber resilience. This chapter outlines the policies that organisations have put in place, including governance documentation, insurance policies and staff skills.

Between Waves One and Three, organisations are more likely to have a cyber security policy in place, with businesses in particular more likely to have adopted a cyber security policy than at Wave One. Compared to previous waves, the findings of greatest note are that:

-

Approximately nine in ten organisations (89% of businesses and 92% of charities) have in place at least one of the five documents considered part of an effective cyber security strategy. While this is almost identical to previous waves for charities, this represents an increase since Wave One among businesses (82% in Wave One).

-

The share of businesses that have all five types of documentation in place is higher than at Wave One (22% compared with 17%), while the share of charities has remained consistent (16% in Wave Three).

-

Businesses are more likely than in Wave One to have several types of cyber security documentation including: a Business Continuity Plan covering cyber security; documentation of the organisation’s IT estate and vulnerabilities; a risk register that covers cyber security; and ‘risk appetite’ documentation. This represents the continuation of a trend that started in Wave Two.

-

The maintenance of a risk register that covers cyber security remains more common among charities (73%) than businesses (55%).

-

Both businesses (up from 53% to 69%) and charities (up from 66% to 79%) are more likely than in Wave One to possess some form of cyber security insurance, even if this is covered within a more general policy. Organisations are also more likely to be aware of what insurance cover they have, compared with Wave One (Don’t know has declined from 34% among businesses and 20% among charities in Wave One to 17% and 11% respectively in Wave Three).

-

Around six in ten businesses (59%) and charities (62%) have delivered cyber security training or awareness raising sessions specifically for individuals not directly involved in cyber security. These shares are consistent with Wave Two and represent an increase on Wave One (48% among businesses and 55% among charities).

3.1 Governance and planning

As in previous waves, the survey asked about five types of documentation that organisations may have in place as part of an effective cyber security strategy. As detailed in Figure 3.1, these are: a Business Continuity Plan covering cyber security; documentation identifying critical assets; documentation of the organisation’s IT estate and vulnerabilities; a risk register that covers cyber security; and documentation of what is considered an acceptable level of cyber risk (‘risk appetite’).

Most organisations (89% of businesses and 92% of charities) have at least one of these documents in place. While the share of charities is similar to previous waves, the share of businesses represents an increase from Wave One (82%) and a continuation of the trend from Wave Two (86%). More than one in five businesses (22%) and a lower share of charities (16%) have all five types of documentation in place. Again, the share of businesses is higher than at Wave One (17%), while the share of charities is very similar to previous waves of the survey.

As illustrated in Figure 3.1, in Wave Three, a majority of businesses currently have each type of documentation in place, with the exception of ‘risk appetite’ documentation (33%). Most prevalent among businesses is a Business Continuity Plan that includes cyber security (76%). The proportion of businesses with these documents at Wave Three are higher than at Wave One for: a Business Continuity Plan covering cyber security (76% compared with 69% at Wave One); documentation of the organisation’s IT estate and vulnerabilities (61% compared with 54%); a risk register that covers cyber security (55% compared with 48%); and ‘risk appetite’ documentation (33% compared with 26%). For each of these types of documents, this trend has built upon changes first seen in Wave Two, although the changes between waves are only statistically significant between Waves One and Three.

Large and very large businesses (250+ staff) are more likely to have all five types of documentation in place (31%), compared with medium-sized businesses (19%). However, the difference is much smaller when comparing medium businesses that have at least one type of documentation in place (88% among medium businesses and 91% among large/very large businesses).

A ‘complete’ set of documentation is also more likely to be held where a business has some form of accreditation or board oversight of cyber security risk. For example, businesses where the board discusses cyber security monthly (30%) or at least once a year (27%) are more likely to have all five documents when compared to those businesses where the board never discusses cyber risk (4%). Similarly, businesses are more likely to have at least one of the documents in place if the board discusses cyber security monthly (93%) or at least once a year (91%) rather than not at all (79%).

The level of cyber security documentation within charities is similar to that of businesses. The only exception relates to the maintenance of a risk register that covers cyber security, which remains more common in charities (73%) than in businesses (55%). Around three-quarters of charities (73%) have a business continuity plan in place, but relatively few have documentation that outlines the level of cyber security risk they are willing to take (29%). The shares for individual documents are in line with previous waves.

Figure 3.1: Documentation in place to help organisations manage their cyber security risks

Does your organisation have any of the following documentation in place to help manage cyber security risks?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle.

Figure 3.2: Documentation in place to help organisations manage their cyber security risks

Does your organisation have any of the following documentation in place to help manage cyber security risks?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle.

3.2 Cyber insurance policies

Businesses and charities are both more likely than in previous waves to have some form of cyber insurance cover in place (Figure 3.3). About seven in ten businesses have some form of cover (69%), rising from 53% at Wave One and 61% at Wave Two. The share among charities has increased from 66% at Wave One to 79% at Wave Three.

Underlying the overall increase in insurance cover among businesses is the increase in the use of broader, non-cyber security specific insurance policies (Figure 3.3). Approximately one-quarter of businesses (26%) have a specific cyber security policy. This is similar to the share at Wave Two (25%), after an increase from Wave One (18%). By comparison, the usage of broader insurance policies to cover cyber security at Wave Three (43%) is higher than in both Wave Two (36%) and Wave One (35%).

In contrast, the increased share of charities reporting being insured against cyber security incidents is driven by increased prevalence of a specific cyber security insurance policy. In Waves Two and Three, about one-third (32%) have a specific cyber security policy, compared to 24% from Wave One. The share of charities with a broader insurance policy is in line with previous waves (46% in Wave Three, compared to 42% in both Wave One and Wave Two).

Importantly, around one in ten organisations (13% of businesses, 10% of charities) say they have no form of cyber security insurance in place. Others remain unaware of what insurance cover they have against cyber security incidents, although this proportion has fallen since Wave One, among both businesses (17% compared with 34% at Wave One) and charities (11% compared with 20% at Wave One).

Insurance cover is more frequently in place where businesses have also made wider investment in cyber security protection. For example, businesses with all five types of documentation mentioned above are more likely to have some form of cyber insurance cover (83%) than those without all five (65%) or none (40%). In addition, 83% of businesses that are certified to the Cyber Essentials standard have cover, as do 82% of businesses with Cyber Essentials Plus certification and 83% with ISO 27001. It is important to note that both Cyber Essentials certifications also allow organisations to claim free insurance, perhaps helping to explain this finding.

The share among those businesses holding none of these three certifications is 61%, and around one-quarter (23%) of these businesses have no insurance at all against cyber security incidents.

Figure 3.3: Organisations with cyber insurance

Which of the following best describes your situation?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle.

The increase in the share of businesses with cyber security insurance is reflected in the longitudinal sample (organisations first interviewed in Wave One or Wave Two). Among businesses in the longitudinal sample, 73% have some form of cyber insurance cover in place, higher than at Wave One (58%) and Wave Two (63%). The share of charities with some form of cyber insurance cover has also increased from Wave One (70%) to Wave Three (81%).

Figure 3.4: Type of cyber insurance policy organisations have

Which of the following best describes your situation?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle.

The qualitative interviews suggested that cyber security insurance can come at a considerable cost to the organisation, although it was noted that insurance premiums could be lower where organisations had Cyber Essentials accreditation or had other evidence of controls being in place. One business pointed out that the cost of insurance was cheaper than the cost of an attack.

“I guess it’s the cost of the premiums against what an attack would cost us.”

Business, Medium, Utilities or production

In addition to the financial benefit and mitigation of potential losses, cyber security insurance can provide wider organisational benefits. Part of the process of obtaining this insurance is to review and document procedures, which can prove helpful.

“They (insurance company) have a list of things they want us to have that they then audit…they won’t give us the insurance without it”

Business, Medium, Information and communication

Another business that was in the process of taking out insurance cover outlined how this would raise the profile of cyber security in the organisation, for example by making it more prominent at board level and including it in their annual report. This was seen as necessary in order to demonstrate the importance of cyber security to the insurers.

However, one business was critical of a perceived tendency for organisations to rely on insurance cover as a way of protecting themselves, rather than focusing on controls and procedures to prevent problems.

“Do you pay for insurance and don’t bother protecting yourself? It’s a flawed market.”

Business, Medium, Information and communication

3.3 Staff training

In the past twelve months, approximately six in ten businesses (59%) and charities (62%) have delivered cyber security training or awareness raising sessions specifically for staff and/or volunteers who are not directly involved in cyber security (Figure 3.5). These shares are consistent with Wave Two, after both shares had increased between Wave One and Wave Two (from 48% to 58% for businesses and from 55% to 62% for charities).

Very large businesses with 500+ employees (78%) are more likely to have delivered such training than large or medium-sized businesses (64% and 57% respectively). Other types of business that are particularly likely to have delivered this training include those with all five types of documentation required to attain Cyber Essentials (79%), those who say they adhere to the Cyber Essentials standard (75%) or the Cyber Essentials Plus standard (81%), and those with a specific cyber insurance policy (77%). As such, training appears to be part of a generally more holistic approach to cyber security threats. By contrast, around half (52%) of businesses not adhering to any of the three standards (Cyber Essentials, Cyber Essentials Plus or ISO 27001) and around four in ten businesses with no cyber security insurance (39%) had delivered such training.

Figure 3.5: Cyber security training or awareness raising delivered by organisations in the last 12 months

In the last 12 months, have you carried out any cyber security training or awareness raising sessions specifically for any staff or volunteers who are not directly involved in cyber security?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle.

In the qualitative interviews, some organisations stressed the value of staff training on cyber security, in raising staff awareness and emphasising the potential impact that a cyber incident could have on organisations.

“Everyone … that we have, we put them through the training modules on cyber security and I think the benefit to that training was increasing awareness among staff … I think that is why we do not have as many incidents. Most of our staff know to let me or [our external IT providers] know of anything suspicious.”

Business, Large, Food or hospitality

“There is a massive education piece around the user base - around what is and what is not good cyber security from a sharing data perspective … people definitely need cyber security training.”

Business, Very large, Utilities or production

Some organisations provided regular staff training, sometimes linked to cyber skills assessments of their workforce, although most organisations in the qualitative interviews said they did not carry out workforce assessments. However, some organisations recognised the value of assessments even if they did not do them at present.

“I think it’s a good idea, I am considering it for the future… you can’t improve without having a baseline, which I think assessment of your workforce can give”.

Business, Medium, Information and communication

Staff assessments or training often focused on phishing, for example using a phishing test or a simulation that checked whether staff responded appropriately.

As well as structured training, some organisations viewed cyber security training as a continuous process, involving frequent communication or staff bulletins, as well as measures such as poster campaigns or messages on screen savers.

Chapter 4 – Cyber security processes

Alongside cyber security documentation and training, it is essential that businesses put in place processes to help build their resilience to cyber incidents. This chapter investigates the prevalence of these processes among organisations, along with the standards and certifications that they currently have in place. It also outlines the ways in which organisations monitor and evaluate their policies, along with any improvements that they have made within the last year. By understanding the status of organisations on these policies, it will help to illustrate how businesses are improving their cyber security.

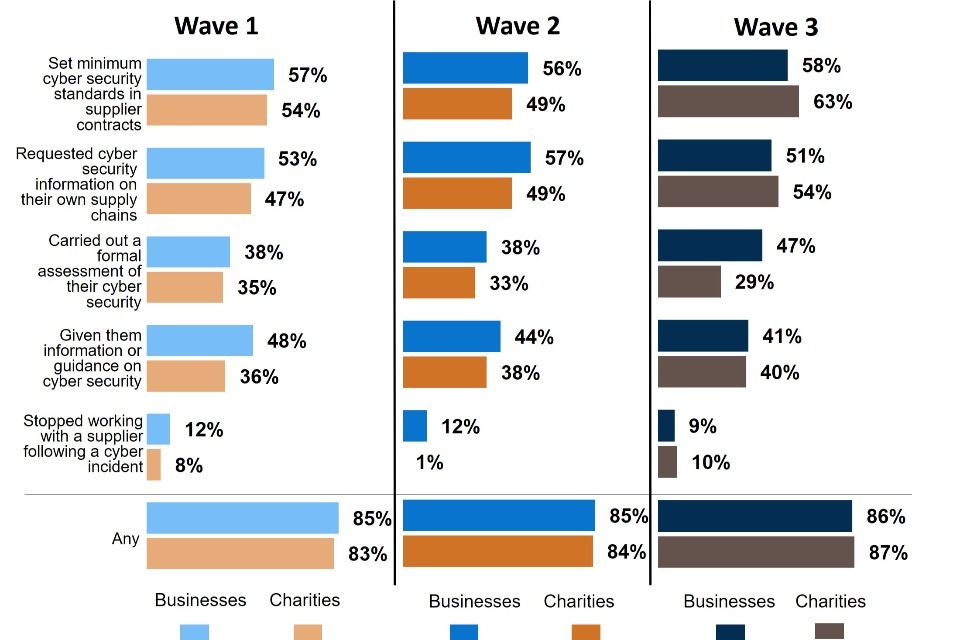

Overall, organisations’ cyber security processes appear to be strengthening, especially among businesses compared to Wave One. However, it is important to note that improvements have remained consistent since Wave Two rather than increasing further. Compared to previous waves of the study, the findings of greatest note are:

- For both businesses and charities, adherence to at least one of the three key cyber security certifications remains consistent since Wave Two but has increased between Wave One (32% of businesses, 29% of charities) and Wave Three (38% of businesses and 36% of charities). Adherence to the ISO 27001 standard among businesses has increased compared to Wave One (19% vs. 15%).

- As with the previous two waves of this study, most organisations have put in place four of the five technical controls required to attain Cyber Essentials certification. However, more proactive measures, such as patch management (67% among businesses, 66% among charities) and user monitoring (58% of businesses, 55% of charities), remain less common.

- Businesses especially have improved their cyber security measures to improve their resilience. Among businesses, the prevalence of cyber security incident identification measures has increased compared to Wave One (90% vs. 82%).

- Further, the proportion of businesses making changes to improve their cyber security processes within the last twelve months has also increased (85% in Wave Three compared to 79% in Wave One). However, this has remained consistent between Waves Two and Three.

- Only a small minority of organisations refer to cyber security in their annual report (18% of businesses and 23% of charities).

- Relatively few businesses and charities (28% and 26% respectively) take into account the risk that suppliers pose to their cyber security.

- Large businesses are much more likely than average to have a more sophisticated cyber security infrastructure in place, compared to medium sized businesses. For example, 47% of large businesses and 35% medium-sized businesses adhere to at least one of the three key cyber security certifications.

- Organisations that are accredited with a cyber security certification often have more substantial security processes and procedures in place. For example, 33% of businesses adhering to ISO 27001 mention cyber security in their most recent annual report compared to 18% of all businesses. This suggests they take a more holistic approach to their cyber security.

4.1 Standards and certifications

A number of cyber security certifications have been developed to encourage good practice in cyber security within organisations. These standards are often based on government guidance and their implementation helps organisations make themselves more resilient. This study focuses on three certifications: Cyber Essentials[footnote 9], Cyber Essentials Plus[footnote 10] and ISO 27001[footnote 11]. The survey asks organisations which of these standards or accreditations they adhere to, however they are not asked to confirm which certification(s) they currently hold. Please also note that between Waves Two and Three the questionnaire was changed to ensure that Cyber Essentials and Cyber Essentials Plus could not be selected at the same time. This ensured that for Wave Three, Cyber Essentials was not overrepresented in the data. For the data included in this report, we have edited the data from Waves One and Two to reflect this routing.

As seen in Figure 4.1, while the proportions of charities and businesses adhering to at least one of these standards increased between Wave One (32% of businesses, 29% of charities) and Wave Three (38% of businesses and 36% of charities), there has been little change between Wave Two and Wave Three.

ISO 27001 (19%) has narrowly become the most common certification adhered to among businesses, with more businesses adhering to it since Wave One (15%). Adherence to Cyber Essentials remained stable, with around one in five businesses adhering to Cyber Essentials in both Wave Two (19%) and Wave Three (18%). Adherence among businesses to Cyber Essentials Plus has also remained consistent (11% in Wave Two, 9% in Wave Three).

Among charities, however, Cyber Essentials remains clearly the most popular certification (23%). While this is in line with Wave Two (also 23%), it represents an increase compared to Wave One (16%). Cyber Essentials Plus (8%) and ISO 27001 (7%) are adhered to by far fewer charities.

Larger businesses are more likely to report that their organisation adheres to at least one of these certifications. Almost half of large or very large businesses (47%) do so, much higher than among medium businesses (35%). In particular, very large companies with 500+ staff are over twice as likely as medium businesses to adhere to the Cyber Essentials Plus standard (16% vs. 7%).

Figure 4.1: Standards and accreditations held by organisations

Which of the following standards or accreditations, if any, does your organisation adhere to?

Base: All businesses at Wave 1 (n=1,205) and at Wave 2 (n=688) and at Wave 3 (n=542); All charities at Wave 1 (n=536) and at Wave 2 (n=373), and at Wave 3 (n=310). Significance testing between Wave One and Wave Three is represented with a black arrow, and between Wave Two and Wave Three is represented with a black triangle. * Please note that the Wave One and Two data has been edited to reflect a change in questionnaire validation (participants mentioning both Cyber Essentials and Cyber Essentials Plus in those waves were re-coded to Cyber Essentials Plus only to match the validation in Wave Three).

Businesses that have experienced a non-phishing cyber incident in the past year are more likely to report that they adhere to at least one standard than the total for all businesses (45% vs. 38%). Although not statistically significant, two in five charities that experienced a non-phishing cyber incident in the last twelve months say they adhere to a standard (40%) compared to around three in ten charities that had not experienced an incident (31%). Crucially, more than two in five businesses (41%) and charities (45%) say their organisation does not adhere to any of the three certifications. The qualitative research again revealed mixed views of the usefulness of the different certifications. Several organisations that adhered to Cyber Essentials said they did so because it allowed them to meet a contractual requirement when working for the government or public sector in general, or because having the certification was felt to send a message to external stakeholders, board members, customers or insurers that the organisation takes cyber security seriously.

Some regarded Cyber Essentials as more of a ‘tick-box’ exercise or were sceptical of the value of an accreditation based on self-certification rather than external scrutiny. Larger organisations or those with a more explicit focus on IT tended to place more value on the ISO 27001 certification, which they saw as more rigorous. Conversely, some medium-sized organisations saw ISO 27001 as ‘overkill’ and too onerous for them to adopt.

“It was always going to be Cyber Essentials. The ISO standard - for the size of the business, we discounted that as not feasible. We don’t have the resource - it’s not a contractual or necessary requirement.”

Charity, Scotland

“It’s the appeal of having certification as a badge to show current and potential insurers that we take [cyber security] seriously.”

Business, Medium, South West

“There is no doubting the benefits [of Cyber Essentials] in terms of reviewing our system, identifying areas of vulnerability and addressing those. The challenge always for an organisation our size is to maintain that level of operation cyber-wise whilst also doing the business. It’s a real challenge - it’s onerous in terms of staff time and attention.”

Charity, Scotland

4.2 Cyber Essentials processes

To attain Cyber Essentials accreditation, organisations are required to have technical controls in place in five key areas. As seen in Figure 4.2, in Wave Three almost six in ten businesses (62%) and charities (59%) have all five technical controls in place. This is broadly comparable between waves. For all organisations, a very large proportion of both businesses and charities – over 90% - say they have each of the following controls in place:

- restricting IT admin and access rights to specific users

- up-to-date malware protection across all devices

- security controls on the organisation’s own devices

- firewalls that cover the entire IT network, as well as specific devices

Figure 4.2: Technical controls in place in the areas required to attain Cyber Essentials

Which of the following rules or controls, if any, do you have in place?

Base: All businesses at wave 1 (n=1,205) and at wave 2 (n=688) and at wave 3 (n=542); All charities at wave 1 (n=536) and at wave 2 (n=373), and at wave 3 (n=310). There are no significant changes between Wave One and Wave Three or between Wave Two and Wave Three.

Very large businesses (those with 500+ employees) are much more likely to have put in place all five technical controls – 79%, compared to 62% of businesses as a whole. This difference is accounted for largely by the much higher proportion of very large businesses that have patch management processes in place (81%).