Transforming Public Procurement - Government response to consultation

Updated 6 December 2021

## Transforming Public Procurement: Government response to consultation

Overview

Introduction

In December 2020, the Cabinet Office set out proposals for shaping the future of public procurement legislation with the publication of a Green Paper, Transforming Public Procurement. The overarching goals of these proposals are to speed up and simplify our procurement processes, place value for money at their heart, generate social value and unleash opportunities for small businesses, charities and social enterprises to innovate in public service delivery.

At around £300 billion, public procurement accounts for around a third of all public expenditure every year. By improving the way public procurement is regulated, the Government can not only save the taxpayer money but spread opportunity, improve public services, empower communities and restore local pride across every region of the country. A procurement regime that is simple, flexible and takes greater account of social value can play a big role in contributing to the Government’s levelling-up goals.

Procurement reform is not new but it has always had to work within the framework of EU based regulations. The latest EU Directives were transposed into UK law in 2015 and 2016. Following the UK’s exit from the EU, we now have an opportunity to develop and implement a new procurement regime, moving away from the complex EU rules-based approach that was designed first and foremost to facilitate the single market and instead adopt a new simplified approach that prioritises boosting growth and productivity in the UK, maximising value for money and social value, promoting efficiency, innovation and transparency.

The Green Paper sought feedback from stakeholders who will be involved in the new regime. This document summarises the feedback received to the consultation and provides the Government’s response to each individual question. We have considered carefully all of the comments received. In some instances, there is no change to the proposals set out in the Green Paper; in others the Cabinet Office has clarified or amended the proposals based on the feedback. Details are set out under the response to each of the consultation questions, however these all remain subject to change as we work to finalise the new procurement regime.

Consultation process

In developing the proposals for the Green Paper, Cabinet Office officials engaged with over 500 stakeholders and organisations through many hundreds of hours of discussions and workshops. This included stakeholders from central and local government, the education and health sectors, small, medium and large businesses, charities and social enterprises, academics and procurement lawyers.

The public consultation on the Green Paper opened on 15 December 2020 and closed on 10 March 2021.

The Green Paper was circulated to a range of stakeholders and was also made available publicly on the GOV.UK website at the commencement of the consultation in December 2020. The Cabinet Office ran a series of open workshops in early 2021 for public bodies, suppliers and other stakeholders aimed at providing an in-depth understanding of the proposals and to encourage interested parties to respond to the consultation. These workshops were attended by over 600 representatives from contracting authorities and over 300 stakeholders from suppliers, industry bodies and other interested parties.

The Cabinet Office has now analysed the consultation and what follows is a detailed review of the responses received. The Cabinet Office is grateful to all those who took the time to respond and for their help in developing the proposals.

Breakdown of responses

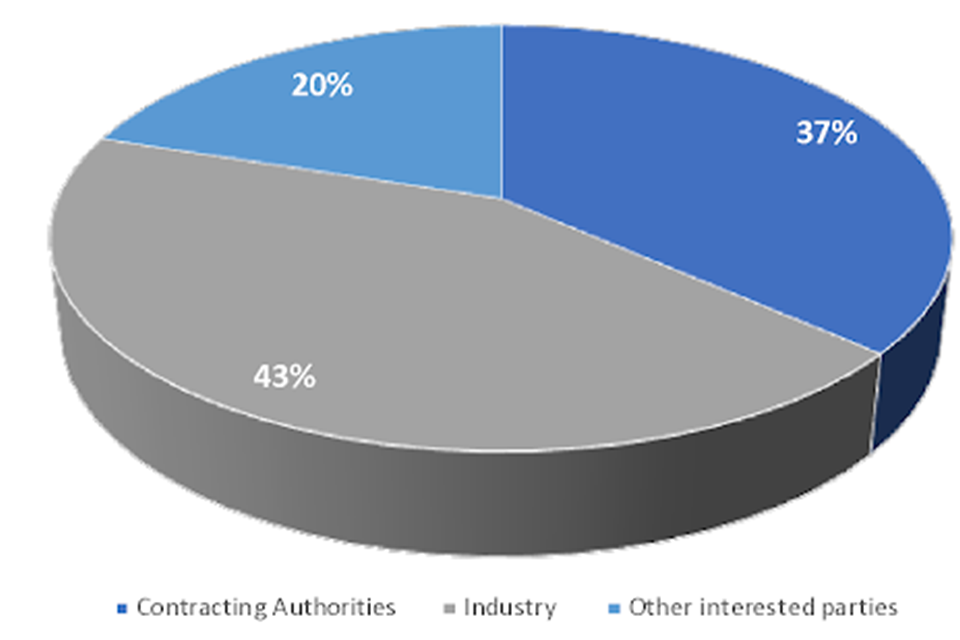

In total, 619 responses to the consultation were received. There was a mix of responses between contracting authorities who will be responsible for procuring within the future regime and suppliers to the public sector who will be bidding in procurements and delivering under contracts under the proposed regime. There were 226 responses from contracting authorities, 269 from suppliers and 124 from other interested parties such as academics, legal professionals and members of the public.

Chart 1 - Responses by respondent category

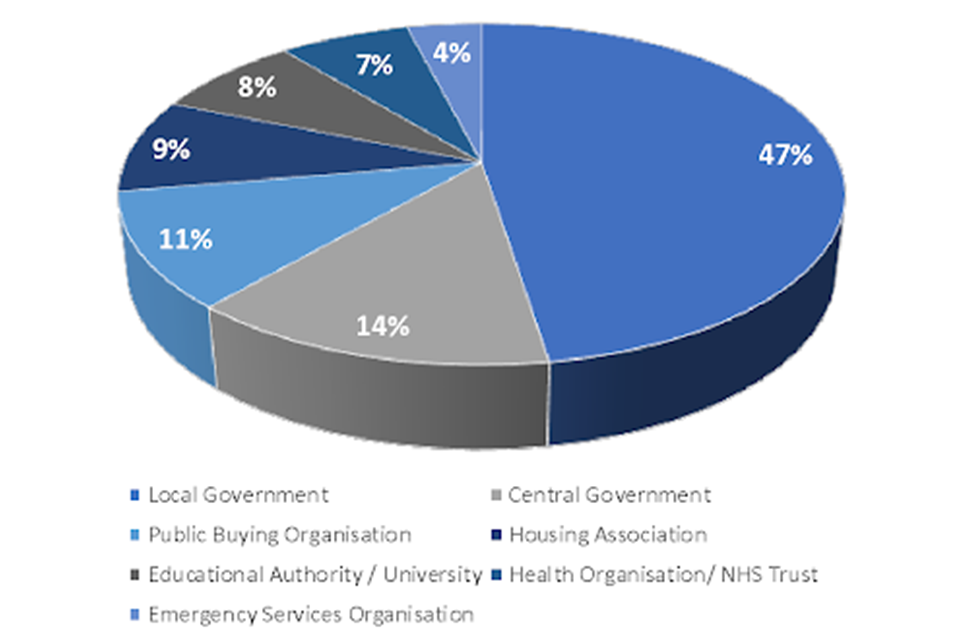

Of the 226 responses from contracting authorities, almost half of these were from local government. There were 32 responses from central government departments as well as representation from housing associations, educational institutions and NHS Trusts.

Chart 2 - Contracting authorities by type

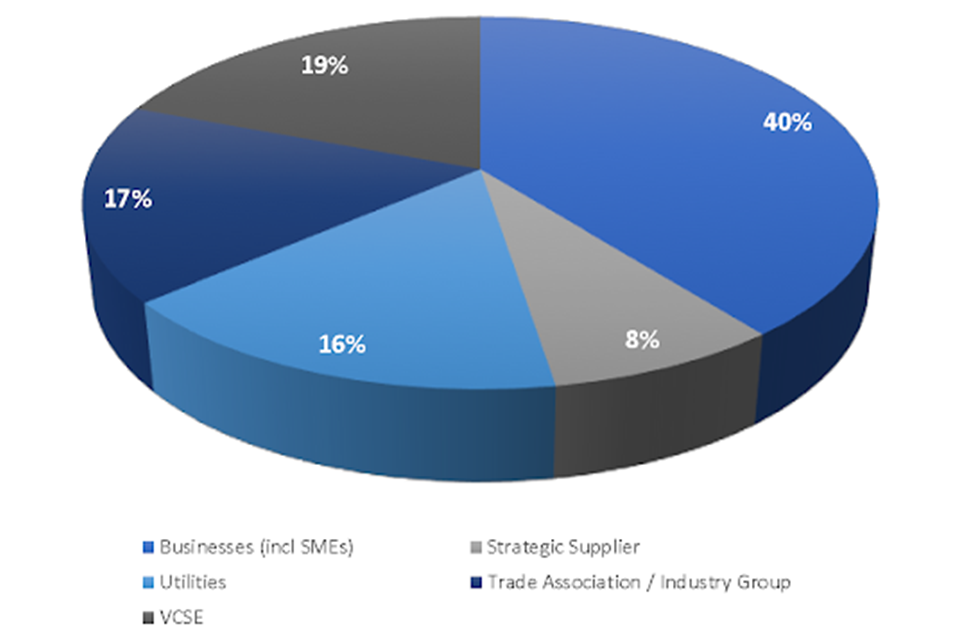

Of the 269 responses from industry, there was strong representation from SMEs and VCSEs. There were 21 responses from the Government’s strategic suppliers. There were 44 responses from the utilities sector.

Chart 3 - Responses from industry

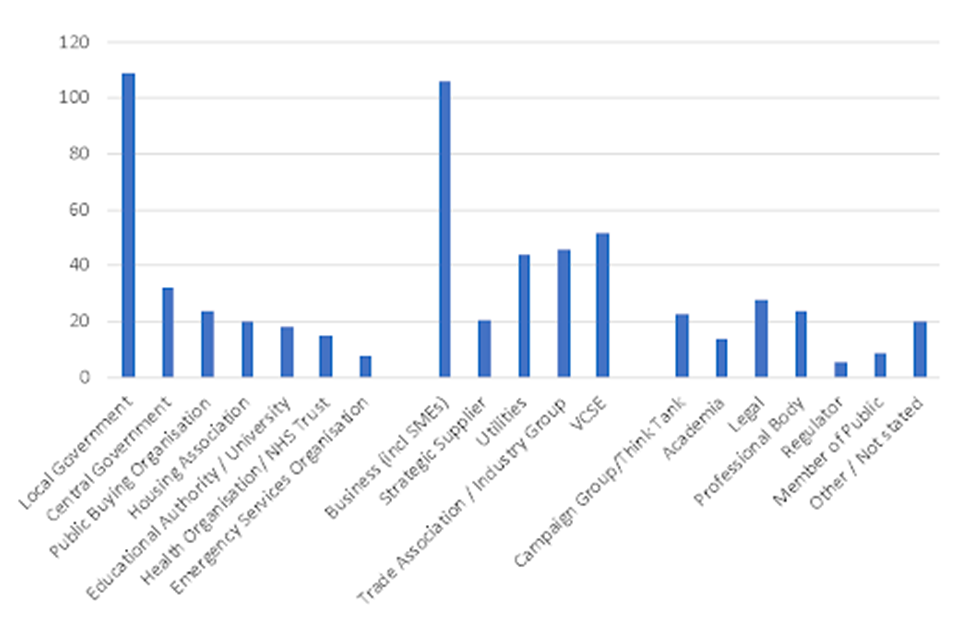

Other interested parties also provided a view, including legal firms, academic experts and professional bodies who responded on behalf of their members. This has provided a range of perspectives from different sectors.

The complete breakdown of responses demonstrates that there was a good range of engagement by contracting authorities and organisations who will be impacted by the reforms, and this provides a robust evidence base for the Government to analyse the proposals and take decisions on the way forward.

Chart 4 - Number of respondents by type

Key themes

Overall, levels of support for the reforms in the Green Paper were high and many responses recognised the ambition and breadth of the package of proposals. The majority of answers to individual questions were positive. A clear majority of respondents agreed with the overarching legal principles of public procurement. Many respondents also recognised that the reforms would present a significant implementation challenge in order to realise the expected benefits.

Most respondents agreed with the proposals to simplify the current legislation as far as possible into a single, uniform regulatory framework and agreed this would make things easier for suppliers engaging with the public sector. There were some concerns raised by organisations operating under the Utilities Contracts Regulations 2016 (UCRs) who were keen to ensure existing levels of flexibility within these regulations were retained, particularly with regard to commercial exemptions where they are competing with the private sector. We plan to ensure certain flexibilities within the UCR are retained. Additionally, there were some concerns around the impact of a simplified regulatory framework on contracts let under the Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations 2011 (DSPCR). Working closely with the Ministry of Defence, we plan to include a number of exemptions to ensure the security implications for these contracts are considered.

The Green Paper proposed the removal of the Light Touch Regime. A number of respondents raised concerns about certain contracts (such as care provision or special education) which, coupled with the proposed lowering of contract value thresholds bringing more contracts within scope of the new regime, would remove necessary flexibility. In light of additional stakeholder engagement, we agree it is helpful to retain the Light Touch Regime, but plan to make some improvements to its scope and application.

A series of changes to strengthen the approach to the exclusion of suppliers from procurements for misconduct such as fraud, corruption or poor performance were proposed. Feedback on these proposals was largely positive and we intend to take most of them forward. However, it was clear from the consultation responses and further engagement with stakeholders that in addition to these changes, a wider refresh of the legal framework for exclusions is needed. Many respondents noted that they found the existing regulations unclear and confusing, highlighting ambiguities around the scope of some of the exclusion grounds, the individuals and entities covered by the regime, the process to be followed to verify self-declarations and the purpose of self-cleaning. These concerns were common to all stakeholder groups, but particularly prominent among contracting authorities, who bear responsibility for considering the exclusion of suppliers from procurements on a case by case basis. Recognising these concerns, we intend to introduce a new exclusions framework which will be simpler, clearer and more focused on suppliers who pose an unacceptable risk to effective competition for contracts, reliable delivery, and protection of the public, the environment, public funds, national security interests or the rights of employees.

There was broad support for the focus on increasing transparency, with respondents recognising the importance of a transparent procurement regime. However, some respondents raised concerns around the parameters of transparency and the potential burden it could place on contracting authorities, slowing down processes and decision-making. Having considered these views and following additional engagement with stakeholders, we intend to ensure the transparency requirements are proportionate to the procurements being carried out and are simple to implement. Detailed guidance will also be published to support contracting authorities with implementing these requirements.

The Green Paper proposed capping the level of damages available to bidders that successfully challenge a contract award decision. There were mixed views on this proposal with some respondents agreeing this would discourage speculative challenges, however others highlighted potential unintended consequences which could slow down procurement processes and ultimately increase the cost to the public purse. Following additional engagement with stakeholders, we will not be taking this proposal forward, but are considering other measures aimed at resolving disputes faster which would reduce the need to pay compensatory damages to losing bidders after contracts have been signed.

Proposals on effective contract management and prompt payment were met with a broad level of support overall, with a number of useful comments on how they could be further improved. A majority of respondents recognised procurement’s role in addressing key issues such as tackling payment delays in public sector supply chains.

Many respondents recognised the need for a level of monitoring of compliance with the new procurement regime. However, some respondents raised concerns about the proposed new unit that would oversee the integrity of the public procurement system, in particular its interaction with existing governance in local government and the regulated utilities sector, as well as how it would operate alongside a formal route of challenge. We intend to amend this proposal to build on existing powers of investigation by the Minister for the Cabinet Office and to introduce a duty for contracting authorities to implement recommendations to address non-compliance of procurement law, where breaches have been identified.

The Green Paper acknowledged that the changes proposed to the regulatory framework would not in themselves deliver faster and more effective procurement, without contracting authorities also having the capability and capacity to realise the benefits. Many respondents raised the importance of training and guidance to support implementation of the new regime, flagging that there was a need for behaviour change, rather than just knowledge transfer. There were a number of suggestions about specific topics that could be included in this training and wider comments on general commercial capability outside the legislative reforms.

Next Steps

In May 2021, the Queen’s Speech announced that legislation to give effect to the Government’s plans to reform public procurement would be brought forward when Parliamentary time allows. Once the Bill becomes an Act, there will need to be secondary legislation (regulations) to implement specific aspects of the new regime.

We plan to produce a detailed and comprehensive package of published resources (statutory and non-statutory guidance on the key elements of the regulatory framework, templates, model procedures and case studies). In addition, and subject to future funding decisions, we intend to roll out a programme of learning and development to meet the varying needs of stakeholders.

We recognise that the scale of change to the procurement regime is significant, and organisations will need time to prepare themselves to function effectively under the new regime. Although it is not yet possible to confirm when the new regime will come into force, we intend to provide six months’ notice of “go-live”, once the legislation has been concluded, in order to support effective implementation. In any event, given the timescales around the legislative process, the new regime is unlikely to come into force until 2023 at the earliest.

Devolved Administrations

The new regime will apply to all public bodies in England. We are working closely with all the devolved administrations on the development of the new regime. On 18th August 2021 the Welsh Government published a written statement on The Way Forward for Procurement Reform in Wales confirming that provision for Welsh contracting authorities is to be made within the UK Government’s Bill. We are in discussion with the Northern Ireland Executive about whether some provisions may be extended to all contracting authorities in Northern Ireland.

Government Response

Chapter 1: Procurement that better meets the UK’s needs

The Green Paper proposed enshrining in law the principles of public procurement: the public good, value for money, transparency, integrity, fair treatment of suppliers and non-discrimination. We proposed legislating to require contracting authorities to have regard to the Government’s strategic priorities for public procurement in a new National Procurement Policy Statement. We proposed establishing a new unit to oversee public procurement with powers to review and, if necessary, intervene to improve contracting authorities’ compliance with the procurement regulations.

Q1 - Do you agree with the proposed legal principles of public procurement?

Summary of responses

Overall, a clear majority of respondents (92% of the 477 responses to this question) were in favour of the principles. Contracting authorities and the supplier community were almost unanimous in supporting the proposal.

There were some specific concerns raised, particularly around the removal of the EU principle of proportionality; 20% of respondents wanted to see proportionality re-introduced, mainly because of the benefits for smaller suppliers and the voluntary sector.

Respondents also asked for more clarity in defining the principles and their practical implementation, particularly in relation to the public good that some respondents thought should be broadened to reflect local priorities.

A number of respondents, particularly within local government, proposed rewording of “fair treatment” to “equal treatment”, indicating that this would be a less subjective criterion.

A small number of respondents (8%) expressed some degree of concern regarding the National Procurement Policy Statement and how this might conflict with local priorities.

Government response

The Government intends to introduce the proposed principles of public procurement into legislation as described in the Green Paper but with some amendments as set out below.

We will refine the proposed wording in the draft legislation on the principles previously proposed into ‘objectives’ and ‘principles’ so that the obligations on contracting authorities are clearer.

The response to the Green Paper showed strong support for the increased emphasis on transparency but highlighted some potential additional burdens on both contracting authorities and suppliers. We therefore propose to introduce procedural obligations at each stage of the procurement process setting out more explicit publication obligations that will provide clarity to contracting authorities on exactly what they need to publish. The transparency principle previously proposed will set a minimum standard in terms of the quality and accessibility of information where there is a publication obligation elsewhere in the Bill.

The principle of non-discrimination will remain, as it is a legal obligation in the UK’s international trade agreements. These agreements contain obligations for the contracting authorities covered by the agreement to treat suppliers from the trading partner country “no less favourably” than those contracting authorities treat domestic suppliers for the types of goods, services and works covered by the agreements.

The principle of “fair treatment of suppliers” will cover both equal treatment of suppliers and procedural fairness during procurement procedures, to provide clarity for contracting authorities. This will require contracting authorities to treat all bidders the same in pursuit of a level playing field.

In addition to the principles set out above, other concepts set out in the Green Paper will be established as statutory “objectives”, ensuring that they will influence decision-making in the procurement process. With some limited exceptions these objectives will apply throughout the procurement lifecycle.

We will introduce an additional objective of promoting the importance of open and fair competition that will draw together a number of different threads in the Green Paper that encourage competitive procurement.

The concept of “public good” will be framed as an objective of maximising the “public benefit” to support wider consideration of social value benefits, and address concerns about any potential conflict with local priorities. Similarly, value for money and integrity will be statutory objectives.

The National Procurement Policy Statement, which was published separately in June 2021, was drafted to reflect the views of some respondents to ensure that it is clear that local priorities can be considered alongside the strategic priorities set out by the Government.

The concept of proportionality is a key concept for the Government, as detailed in the Better Regulation Framework. To ensure this is captured and to address responses requiring more specific detail, we intend to introduce proportionality where it is required in the specific regulations. For example, the proposed legal regime will require the timescales of a procurement procedure to be proportionate to the cost, nature and complexity of the requirement, and that the conditions of participation in a procurement are a proportionate means of checking suppliers have the necessary capability to avoid treating smaller suppliers unfairly.

Q2 - Do you agree there should be a new unit to oversee public procurement with new powers to review and, if necessary, intervene to improve the commercial capability of contracting authorities?

Summary of responses

There were 460 responses to this question, with about half (52%) offering support for the concept of this unit. Of those who offered support, this was qualified with the majority of respondents wanting more information. The greatest support for the proposal came from VCSEs and suppliers to the public sector. Local government and utilities raised concerns about centralised control.

Respondents recognised that there was a need for stronger regulatory oversight of public procurement. Some argued that such a unit could replace or strengthen the existing Public Procurement Review Service (PPRS), and have a role in upskilling more generally, improving standards and ensuring greater consistency across the public sector.

Reservations over the role of a central oversight body included how it would operate across the public sector and whether it would have the necessary resources and capacity to operate effectively. A number of responses, especially from local government, raised concerns around the potential use of spending controls and the balance of increased monitoring with local decision-making. There were also concerns that the unit would be overly bureaucratic and open to abuse. Some respondents were concerned that intervention would delay delivery of the contract by intervening in individual cases of poor practice. Private utilities argued that they should not be included within the scope of any unit as they are already subject to independent regulation.

Government response

We have revised the proposals for this new unit. It will be known as the Procurement Review Unit (PRU), sitting within the Cabinet Office and will be made up of a small team of civil servants.

The PRU will continue to be able to deliver the same service as the Public Procurement Review Service (PPRS) does presently. The unit will be able to investigate cases of poor policy and practice reported by suppliers and make informal recommendations in the same way PPRS does now, including in respect of individual live procurements.

However, the PRU’s main focus will be on addressing systemic or institutional breaches of the procurement regulations (i.e. breaches common across contracting authorities or regularly being made by a particular contracting authority). To deliver this service, it will primarily act on the basis of referrals from other government departments or data available from the new digital platform and will have the power to make formal recommendations aimed at addressing these unlawful breaches.

The PRU will consult and be advised by a non-statutory panel of subject matter experts appointed by the Cabinet Office.

It will oversee procurements subject to the new procurement regime, including utilities and concession contracts, but not those utilities acting under special or exclusive rights.

In order for the unit to improve compliance with the new procurement regime on a wider basis, legislation will need to provide limited powers and duties to investigate the procurement functions of contracting authorities subject to the new procurement legislation (except private utilities operating under special or exclusive rights) and, where instances of non-compliance have been identified, provide a mechanism to ensure future compliance by contracting authorities.

The Minister for the Cabinet Office already has powers under section 40 of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 (SBEEA) to investigate the exercise by a contracting authority of relevant functions relating to procurement. We propose these powers should be repealed from the SBEEA, and included and built upon in the new procurement legislation. The Minister will have powers to act on the results of those investigations by issuing reports and recommendations. Therefore, we propose to:

- provide the Minister with a general power to investigate procurement functions carried out by contracting authorities that are within scope of the legislation;

- place a general duty on contracting authorities in scope to cooperate with an investigation;

- place a duty on contracting authorities within scope of an investigation to respond within 30 days to a notice requesting information or documents;

- provide that the Minister may publish the results of investigations.

Following an investigation, the unit may make recommendations to the contracting authority(ies) for the purposes of improving compliance with procurement functions under the new regime. These recommendations will not target specific procurement decisions (for example, the unit could not recommend a specific contract should be awarded to a particular supplier, or that particular award criteria for a specific procurement be amended). Instead they will be focussed on actions to ensure future compliance. Examples of valid recommendations might include a revision to local operating procedures which have been found to be discriminatory or that procurement staff undertake additional training in evaluation methodologies.

A contracting authority subject to these recommendations to address legal compliance will be under a duty to implement them (unless they can take sufficient alternative action) and to provide progress reports on implementation of those recommendations.

For non-central government contracting authorities, our intention is that the powers will only be used with the agreement of the relevant ministerial department responsible for the sector within which the contracting authority operates. Private utilities acting under special or exclusive rights will continue to be overseen by existing regulatory bodies. However, the unit may engage with the relevant regulatory body via existing governance mechanisms, to share relevant information where appropriate.

The unit may identify common patterns of non-compliance across a number of contracting authorities which could be addressed through statutory guidance. A power will be introduced in the Bill, to enable the Minister for the Cabinet Office to publish statutory guidance which contracting authorities will have a duty to have regard to when exercising procurement functions under the legislation.

Q3 - Where should the members of the proposed panel be drawn from and what sanctions do you think they should have access to in order to ensure the panel is effective?

Summary of responses

A whole range of options were presented in response to this question. Some suggested that the panel should consist of professionals currently working in procurement as opposed to those that have retired or are no longer in the profession.

A number of those responding expressed the need for panel members to specifically have experience of working in or with the public sector, placing an emphasis on fostering collaboration with contracting authorities as opposed to solely focussing on sanctions. Additionally, respondents suggested the panel should have a shared understanding of behavioural factors which influence procurement in order to drive improved performance and capability, sharing best practice and improving value for money.

A few responses indicated the need for a panel that is independent from the government, with involvement from appropriate sector and industry experts. Additionally, a few responses made the suggestion of creating separate panels or a rotating panel depending on the type and nature of the procurement to ensure membership includes representatives from different types of contracting authorities e.g. central government, charities, utilities as well as from suppliers and industry experts.

With regard to sanctions, about half of responses suggested that immediate punitive sanctions could be counter-productive to fostering an environment of innovation and improvement. Suggestions were made to form an initial position of advising on misdemeanours followed up with performance monitoring with perhaps defined interventions in the event that problems continue.

Government Response

The Government acknowledges the need for the panel to have relevant and up to date knowledge and experience; this needs to be balanced against the potential for conflicts of interest when employing panel members. The policy for the PRU and the panel, including the process for appointing panel members, will be developed in due course with the involvement of relevant stakeholders.

The final panel will need to have a breadth of expertise, to ensure the PRU can engage with experts relevant to the type of procurements being investigated. Therefore, for each investigation only a subset of panel members with the specific background, knowledge and understanding will be engaged.

The panel itself is unlikely to communicate directly with any contracting authorities during the investigation but will advise the officials in the PRU during the process of compiling a report and developing any recommendations. Whilst the views of the panel will be taken into account, it will ultimately be for the Minister for the Cabinet Office to issue, and decide the nature of, any recommendations. The panel will have no specific sanctions available to them.

Chapter 2: A simpler regulatory framework

The Green Paper proposed integrating the current procurement regulations (the Public Contracts Regulations 2015, Utilities Contracts Regulations 2016, Concession Contracts Regulations 2016 and Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations 2011) into a single, uniform framework.

Q4: Do you agree with consolidating the current regulations into a single, uniform framework?

Summary of responses

A clear majority (81% of 474 respondents) supported the proposal to consolidate the current regulations into a single, uniform framework although many wanted to know more about how it would work in practice. A small number (8%) opposed the proposal.

Respondents believed the proposal would make the regulations easier for suppliers to understand and remove complexities such as utility companies not being permitted to use frameworks set up under the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 and anomalies such as the lack of self-cleaning provisions in the supplier selection regulation of the Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations 2011 (DSPCR).

There were some concerns around consolidation of the current regulations, primarily from contracting authorities against a potentially more onerous and less flexible regime for the utilities and defence sectors. However, there was also recognition from a defence and security perspective that increased uniformity across public procurement is beneficial (for example by those companies that work across the defence and security markets and wider, who will no longer need to navigate a variety of different regulations, even though certain exceptions relating to defence and security procurement will remain). Industry respondents also thought that the consolidation of the current regulations into a single uniform framework could provide simplicity and cost reduction.

Some respondents highlighted the need to ensure non-clinical services procured under NHS procurement regulations were within the scope of the new legislation. Some respondents also felt that the regime for the commissioning of public services should be split from the purchasing of supplies to create a system better suited to delivering ‘user focussed’ services.

Government Response

The Government intends to combine the current four sets of regulations into a simpler legislative framework as described in the Green Paper, but with some amendments as set out below.

We believe a single, uniform framework consolidated to the greatest extent possible will remove duplication and make procurement more agile and flexible while still upholding fair and open competition. There is, however, some specific flexibility in the current UCR and DSCPR which we recognise need consideration.

Contracting authorities will find the structure of the new procurement legislation familiar and recognise similarities in its application, scope and definitions. The new provisions on principles, procedures, purchasing tools, conditions of participation, contract award, legal challenges and remedies will be set out in much simpler and clearer language than the EU terminology used in our current regulations. The legislation will also take powers to create secondary legislation where, for example, we might need to update the provisions to reflect changes in technology.

The Government is also taking forward reforms through the Health and Social Care Bill, and we recognise the need for integration between local authorities and the NHS (both for joint commissioning and integrated provision across health, public health and social care). The Cabinet Office and the Department for Health and Social Care are working together to ensure a coherent procurement regime for these and other types of user focussed services.

Q5: Are there any sector-specific features of the UCR, CCR or DSPCR that you believe should be retained?

Summary of responses

Only a few of the 343 responses to this question recommended retaining sector-specific features of the Utilities Contracts Regulations 2016 (UCR), Concession Contracts Regulations 2016 (CCR) or DSPCR.

A clear majority of utilities and other organisations which operate under the UCR wanted to retain the current flexibilities of the UCR, specifically with regard to procurement procedures, qualification systems and framework agreements.

In addition, some respondents asked for it to be made clear that a contract awarded by a utility that is not undertaking regulated utility activity should be excluded from the procurement regulations altogether, regardless of the value of the contract.

The small number of respondents who commented on the DSPCR focussed on national security issues and asked for the specific exemptions in the DSPCR to be retained for national security, co-operative armaments projects and government-to-government purchases.

The main concern of the small number of the respondents who commented on the CCR was to maintain sufficient flexibility necessary to award concessions contracts.

Government Response

The Government proposes that the new procurement regime will apply to the utilities sector where the following three conditions are satisfied:

- the entity awarding the contract is a ‘utility’;

- the contract is for works, services or supplies associated with a prescribed relevant utility activity that will generally match the UCRs except for relevant activities in the postal services sector that have been removed as the UK is not obliged to regulate under any free trade agreement; and

- the estimated value of the contract exceeds the relevant financial thresholds that are currently £378,660 for goods and services and £4,733,252 for works.

The Government agrees that contracts procured by utilities for the prescribed relevant activities that are directly exposed to competition should be exempt from procurement legislation, as procurement regulations are unnecessary where competition in a specific utilities sector is functioning well and access to the sector is unrestricted. We propose to create a power for the Minister of the Cabinet Office to be able to exclude utilities where they are directly exposed to competition, similar to that previously provided by the EU procurement directive for utilities which sets out a process to allow the European Commission to exclude from the regime those utility sectors that are subject to direct competition in the market.

We also agree that a number of the existing exemptions specific to certain utilities should be maintained as competition in those markets effectively provides a safeguard for consumers in terms of service quality, prices and efficiency. Specifically, we intend to include exemptions in the legislation for: contracts awarded for the purpose of resale or lease to third parties; contracts and design contests awarded or organised for purposes other than the pursuit of a covered activity or for the pursuit of such an activity outside the UK;

- contracts awarded by certain utilities for the purchase of water and for the supply of energy or of fuels for the production of energy;

- contracts awarded to an affiliated undertaking;

- contracts awarded to a joint venture or to a utility forming part of a joint venture.

The three procurement procedures proposed in the Green Paper - open, limited, competitive flexible - will maintain the freedom of choice and flexibility that utilities currently experience under the UCRs.

The Government proposes the new procurement legislation shall maintain the effect of qualification systems as a separate tool for utilities under similar terms to the UCRs to maintain how utilities currently:

- permit suppliers to apply to be “qualified” suppliers;

- exercise a choice to use a Tender Notice (which replaces the notice on the existence of a qualification system) as a call for competition;

- use lists of qualified suppliers in procurement procedures.

The Government also agrees that the duration of closed framework agreements for utilities should be long enough to allow utilities to cater for their business planning periods that includes requirements from their regulators, e.g. Ofgem sets price controls for the companies that operate the gas and electricity network for a period of five years. We are also considering additional flexibility where, exceptionally, contracting authorities and utilities rely on long term investment from their suppliers particularly with regard to the significant capital schemes and investment that they need to make to introduce new technology.

The Government proposes to allow utilities to retain the ability to make contract modifications for additional goods, works or services by the original contractor, without any financial cap, if the utility cannot change the supplier under the same conditions as Regulation 88(1)(b) in the UCRs. Utilities require this flexibility on large, complex infrastructure projects. A financial cap could be detrimental to the management of these projects resulting in additional costs. However, utilities, like other contracting authorities, will publish contract change notices to bring about greater transparency in contract management.

Aside from these specific aspects, procurements for utilities contracts will be subject to the new core regime.

The proposal for integrating the regulations for concession contracts into the core regime will be taken forward, however there will be specific provisions covering the definition of a concession, how a concession contract is to be valued and the duration of a concession contract. These specific provisions address the key points raised by stakeholders responding to the consultation. The Government also proposes retaining the higher financial threshold for concession contracts, the greater discretion with regard to the method of calculating the estimated value of a concession contract, and the express exemption for lottery operating services as well as some other specific exemptions which exist under the current regime. Aside from these specific aspects, procurements for concession contracts will be subject to the new regime.

The Government proposes maintaining a full suite of national security exemptions for sensitive defence, security, and civil procurement. The exemptions for international co-operation will reflect the Ministry of Defence’s unique range of international collaboration projects. We will ensure that the general provisions on procurement procedures together with defence and security specific parts are flexible enough to meet the needs of urgent operational requirements.

In terms of sector specific features, industry stated that it would be important to retain those provisions which necessarily distinguish the DSPCR from the PCR for reasons of national security e.g. in respect of use of the limited tender procedure for reasons of urgency.

We are currently considering defence and security sector specific features in the new regime to give greater flexibility around contract amendments and limited tendering. These include options in the event of a single supplier remaining in a competition, addressing gaps in capability, addressing issues around urgency and operational demands, enabling better exploitation of new and emerging technologies during the life of a contract. Additionally, changes to the core rules will be made to better suit the characteristics of defence and security procurement, for example the duration of framework agreements. Elements of the rules may be removed where these areas can be adequately covered within the tender documents themselves, for example specific provisions around security of information or security of supply.

In addition to these sector specific parts, contracting authorities will be able to exempt procurements from the requirements of the regime on national security grounds, including to ensure we are able to meet our defence and security needs going forward in line with the Defence and Security Industrial Strategy (DSIS) published in March 2021.

Changes to the procurement regime will sit alongside the wider initiatives set out in DSIS, including industry, government and academia working ever closer together to drive research, enhance investment and promote innovation. We will seek to improve the speed of acquisition and ensure that we incentivise innovation and productivity. We will continue to build on the strong links we enjoy with strategic suppliers to ensure we retain critical capabilities onshore and can offer compelling technology for international collaborations.

Chapter 3: Using the right procurement procedures

The Green Paper proposed overhauling the often complex and inflexible procurement procedures and replacing them with three modern procedures:

- a new ‘flexible competitive procedure’ that gives buyers freedom to negotiate and innovate to get the best from the private, charity and social enterprise sectors;

- an ‘open procedure’ that buyers can use for simpler, ‘off the shelf’ competitions;

- a ‘limited tendering procedure’ that buyers can use in certain circumstances, such extreme urgency.

The Government also proposed including ‘crisis’ as a new ground on which limited tendering can be used (to provide greater certainty for contracting authorities should there be a local or national emergency). We also proposed to make it mandatory to publish a notice when a decision is made to use the limited tendering procedure (on any ground). Given that the new competitive flexible procedure would allow the majority of actions currently allowed under the Light Touch Regime, the Green Paper proposed to remove the Light Touch Regime as a method of awarding contracts.

Q6: Do you agree with the proposed changes to the procurement procedures?

Summary of responses

50% of the 472 respondents were supportive of the proposal, with only 6% opposed. However, 44% of respondents caveated their answer so that it was not definitive.

The key concern raised by respondents was that the new competitive flexible procedure could introduce more complexity into procurements as it requires design and tailoring to the procurement being undertaken. There were concerns that this would require additional effort for contracting authorities as well as creating variances in procedures which could lead to increased cost and complexity for suppliers, particularly SMEs. There were also concerns about a consequential increase in legal challenges, allowing case law to add additional regulations in place of prescriptive procedures.

Concerns were also raised about the removal of the Light Touch Regime (including lowering the contract value thresholds) resulting in more services being subject to the full procurement regime. Additionally, some respondents pointed out the need for special consideration for procurements where there is an element of ‘service user choice’ provided for under separate legislation such as the Care Act 2014 (with the need for contracting authorities to comply with these choice requirements to be reflected in the new legislation). There were also concerns that important flexibility would be removed and contracts for services such as health/social care would be adversely affected, for example requiring set time limits could delay delivery of services.

Government Response

We recognise that use of any competitive flexible procedure may require more consideration by contracting authorities at the outset of a procurement in order to decide the best manner in which to run their procedure. However, it is thought this increased effort at the outset will enable more complex procurements to be better designed and run by contracting authorities. Contracting authorities will be obliged to set out how the procurement process is to function, and this will be laid out in a Tender Notice. The Tender Notice will cover any conditions for participation; time limits for contacting/responding to the authority; evaluation criteria, and the phases involved in any multi-staged procedure. As contracting authorities will have to conduct the procurement in compliance with the Tender Notice, this will provide suppliers with visibility and assurance. It is also important to note that for ‘off-the-shelf’ or straightforward procurements the open procedure can still be used.

In order to ensure consistency and compliance with legal obligations, we plan to issue guidance to support the new competitive flexible procedure. We intend to produce template options for contracting authorities to design their procedures, but without being so prescriptive that it stifles innovation or the use of bespoke processes where deemed appropriate. We will also provide case studies of how different procedures can be used in specific sectors (e.g. utilities) or for certain types of procurement (e.g. research programmes) to support implementation.

The Government response on the Light Touch Regime can be found at question 12.

Q7: Do you agree with the proposal to include crisis as a new ground on which limited tendering can be used?

Summary of responses

50% of the 462 respondents supported this proposal, with a small number opposing and the remainder asking for further clarification such as an exact definition of what would constitute a crisis and whether this could be applied for local as well as national events. There were concerns about the process for the declaration of crisis and whether this would in fact lead to additional delay in urgent procurements. Finally, there were concerns about transparency to ensure public visibility of how contracts were being awarded during a crisis. Additionally, a few respondents raised concerns about the word “crisis” and whether this would create confusion.

Government Response

The Government agrees that the need for contracting authorities to be able to act quickly and effectively in an emergency needs to be balanced against inadvertently allowing too much discretion to directly award contracts under the limited tendering procedure where that is unjustified (for example because there is time to run a competition or call off from an existing framework). The current provision allowing limited tendering in situations of extreme urgency brought about by unforeseeable events (Regulation 32(2)(c) in the PCR) is to be retained and likely to be sufficient to allow for most public contracts required to deal with urgent situations. However, the Covid-19 situation exposed some uncertainty in applying Regulation 32 where the situation is prolonged or evolving.

The Government is still considering the best way to address these issues. We plan to move away from the term “crisis” given the concerns raised and the proposal is to include a limited tendering ground, in the form of a new power for a Minister of the Crown (via statutory instrument) to ‘declare when action is necessary to protect life’ and allow contracting authorities to procure within specific parameters without having to meet all the tests of the current extreme urgency ground. The ground would be based on Article III of the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) which allows states to take steps necessary to protect public health, etc. It is envisaged that ‘necessary’ means “necessary to (a) protect human, animal or plant life or health, or (b) protect public order or safety”. This is subject to other GPA requirements such as those steps being proportionate and non-discriminatory. Any legislative mechanism such as a power for a Minister of the Crown to be able to declare this ground would only be used extremely rarely and would be subject to parliamentary scrutiny. Contracts awarded under extreme urgency and/or this ground would be notified via the new mandatory transparency notice requirement and therefore may be challenged if the reliance on these grounds is inappropriate.

Q8: Are there areas where our proposed reforms could go further to foster more effective innovation in procurement?

Q9: Are there specific issues you have faced when interacting with contracting authorities that have not been raised here and which inhibit the potential for innovative solutions or ideas?

Q10: How can the Government more effectively utilise and share data (where appropriate) to foster more effective innovation in procurement?

Q11: What further measures relating to pre-procurement processes should the Government consider to enable public procurement to be used as a tool to drive innovation in the UK?

Summary of responses

Given the significant overlap in the responses we have consolidated the four questions above. A dominant theme was the capability, competence, confidence and willingness of procurement teams in contracting authorities to embrace an innovative approach within the context of the flexibilities of the new regime. Nearly half of those who commented raised the need for learning and development activity to support implementation of the new regime.

Some respondents commented that SMEs are more likely to develop innovative solutions and that this should actively be encouraged. There were detailed accounts from a range of respondents of how current procurement and commissioning practice could work against the involvement of SMEs and VCSEs in public contracts. A common theme was innovation being hampered by insufficient or ineffective collaboration through lack of contracting authorities’ understanding of the market, lack of effective engagement and negotiation with prospective suppliers before and during the process and post-award. The challenge of managing differing risk appetites, internal processes and governance in collaborative projects was often mentioned.

Another commonly raised point covered the timeliness of procurement processes and in particular the need to allow sufficient time for innovative bids to be developed, to run efficiently once underway (with a number of responses highlighting the difficulty of managing delays in the process), and for contracts to run for appropriate time periods, avoiding short-termist thinking or locking suppliers out of swiftly-evolving markets. Barriers to SME and VCSE participation such as lack of resources to service complex and burdensome procurement procedures, disproportionate bidding requirements, excessively large contracts and problems with accessing information about potential contracting opportunities were frequently cited. Also frequently mentioned was the need for contracts to focus on the most appropriate factors in successful delivery: there was criticism of contracting authorities’ focus on inputs rather than outcomes and on price/cost rather than broader value considerations. Some responses highlighted the need to prioritise the perspective of service users in the procurement process.

Some responses highlighted the desirability of a common understanding of what comprised “innovation”; and the difficulty of evaluating innovation and innovative elements of tenders. Additionally, there was a view that public procurement could be quite restrictive in terms of the contract terms and conditions, with intellectual property rights cited as an issue, and amendments provisions limiting the level of change possible when the scope and requirement may be quite fluid.

Respondents provided a number of suggestions for improvement, including: awarding more contracts locally to assist SMEs and foster innovation; using different assessment and/or contracting methods; putting less emphasis on price and more on the suitability of the contract deliverable; and utilising customer testing or prototypes. It was suggested more could be made of gainshare or incentivisation based contracts that encourage collaborative rather than transactional relationships.

In addition to providing specific examples of barriers to innovation, respondents also used their answers to highlight other issues they experience with the current regime, or to predict those that they perceive may arise as a result of the implementation of the proposed new regime. Many provided details of aspects that they would like contracting authorities to take greater account of, for example more focus on social and environmental impact, more transparency, greater encouragement for use of Project Bank Accounts.

There were a number of ideas and suggestions of how data could foster innovation and be used to deliver broader benefits. There were three key themes running through these responses:

-

creating a more digital and integrated procurement system, linking different data sets using automation and data analytics to increase efficiency, visibility, accessibility, sharing enhanced insights as to what Government is procuring and opportunities for innovation, will deliver exponential value;

-

improving the quality, consistency, comparability, governance and management of data to enable more meaningful analysis by standardising, categorisation of products/services and through a mandatory database repository; overcoming limitations and barriers such as legal protections to commercially sensitive information, Intellectual Property Rights conditions, confidentiality, in addition to the potential for increased bureaucracy, resource and cost implications on both contracting authorities and suppliers e.g. redacting published information and the use of multiple systems across the public sector leading to data overload, and difficulty to access large volumes of unfiltered data can become unmanageable and therefore of little practical benefit.

The majority of respondents agreed that more should be done to promote and encourage pre-procurement market engagement as a key measure to drive innovation. There was a mixed view as to whether the approach should be addressed through further reform of the regulations or if this would limit its effectiveness and instead greater clarity is needed and more guidance should be provided around the process and procedures so as to maintain flexibility.

The four key themes running through these responses were:

- early market engagement - the need to promote and encourage timely market engagement to co-design the solution through guidance, training, sharing best practice/lessons learned, whilst also maintaining flexibility in the approach;

- regulatory challenges stifling innovation - the need to address the burdens and restrictiveness of the procurement regulations to encourage and enable innovation;

- innovation events and tools - greater encouragement of and access to innovation events, tools and resources (guidance, virtual/face-to-face demonstration days, workshops, innovation portal to showcase ideas, supplier portal) and mechanisms for incorporating pilots and testing services early into the commercial strategy; measures for incentivising innovation investment - driving innovation through incentivisation measures to support R&D and reduce supply side investment risks through funding, grants, gainshare and IPR treatment/protection.

Government Response

The Government wants to support innovation through public procurement. Many of the responses to these questions were about behavioural rather than regulatory practice, however within the new legislation we will create the flexibility to allow more innovative procurement. We will put more emphasis on planning and pre-market engagement and this should support effective use of the new competitive flexible procedure (which gives contracting authorities the ability to design and run a procedure that suits the market in which they are operating). The new public notice requirements for planning procurements and early market engagement will provide transparency of contracting authorities’ procurement pipelines and processes. We will support contracting authorities through guidance to encourage earlier engagement and openness in procurements to get potential suppliers involved sooner.

The competitive flexible procedure will drive greater innovation. Innovation proved critical to the Government’s response to the Covid pandemic, for example, the Ventilator Challenge programme resulted in over 15,000 ventilators being delivered in just over four months by UK manufacturers who applied significant innovation to develop new solutions based on their expertise in other areas of manufacturing. The new procedure will be a mechanism for encouraging and accessing innovation to transform the delivery of public services.

We will take forward a change from the use of the term Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) to Most Advantageous Tender (MAT), to reinforce the message to contracting authorities that they can take a broader view of what can be included in the evaluation of tenders when assessing MAT. This is addressed in more detail in question 13. In addition, the Government has already developed significant policy in this area within the bounds of the existing procurement regime through the introduction of a new social value model for central government so that social value benefits are explicitly evaluated in all central government procurement where relevant (rather than just ‘considered’ as currently required under the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012).

Our proposals on transparency demonstrate our commitment to ensuring that public procurement (and the operation of procedures and decision making) is open, fair and non-discriminatory, and there is appropriate scrutiny and accountability for the use of public money in procurement.

Q12: In light of the new competitive flexible procedure, do you agree that the Light Touch Regime for social, health, education and other services should be removed?

Summary of responses

Some (43%) of the 619 respondents did not answer this question, perhaps not surprisingly given that use of the Light Touch Regime is focused in specific areas of the public sector. Of those who did respond, 46% supported the proposal, 29% were opposed and the remainder of the responses were not clear in either direction. The largest reaction was from local government and of those who responded, 42% were opposed and 30% supported the proposal but in some cases that was in support of using the new procedure but maintaining the existing higher threshold.

There were a number of detailed responses. A key issue raised was around service user choice and allowing for individual care in cases such as adult and children’s residential care, fostering and special education. These are often highly tailored, specialised services which are required in short timescales. The message from those involved in procuring and supplying user-orientated services was very clear that these services for numerous reasons need to be treated differently to other types of public procurement. This was particularly important for local government, the education sector, and in health and social care, as well as, given the nature of the sector, a high proportion of VCSEs.

There were also concerns that in lowering the threshold for the current Light Touch Regime services, there would be a considerable increase in the number of contracts subject to the full regime, increasing the administrative burden and costs on both contracting authorities and suppliers. The extra work caused by such a move could cause a significant resource problem for those affected by such a change and could threaten the participation of SME and VCSE providers who do not typically have extensive resources to engage in competitive tendering exercises.

Government Response

The Government has carefully considered this feedback and will ensure the new legislation continues to allow certain services to be treated differently. Their treatment will be similar to the existing Light Touch Regime, but will reflect changes in the broader regime such as the noticing and transparency requirements. We are considering scope and whether some services which have never been procured using the Light Touch Regime can be removed.

The most commonly raised issue was that the lower threshold and the mandated time periods of the full regime would have a negative impact on the ability to deliver these services. The time periods in particular could delay the delivery of a service which was critical for the provision of care, as stated elsewhere. Key to these reforms is simplicity so while removing the Light Touch Regime is simpler on the face of it, it could instead build in more difficulties and delay which is not our intention.

We have actively engaged with a range of interested stakeholders and are grateful for their continued expert support. This has highlighted an underlying issue which simply reinstating the existing Light Touch Regime would not resolve. The current Light Touch Regime assumes that competition is the default, and while this is absolutely right where possible, where there are legislative obligations for choice such as those in the Care Act 2014 and the Childrens and Families Act 2014, local authorities should not have to navigate inappropriate procurement requirements and build unnecessary bureaucracy into their decision making to ensure they can comply.

To address this, we are considering the extent to which we can exempt from competition those services where service user choice is important. Our aim is to ensure that the individual is put at the centre of these procurements, with regulations that are as simple as possible for contracting authorities, not only in terms of the specific procurement obligations but the way they interact with other legislative requirements.

Chapter 4: Awarding the right contract to the right supplier

The Green Paper proposed retaining the current requirement that award criteria must be linked to the ‘subject matter of the contract’ but amending it to allow specific exceptions set by the Government. It proposed retaining the requirement for the evaluation of tenders to be made solely from the point of view of the contracting authority, but amending it so that, exceptionally, a wider point of view can be taken. It proposed using the exclusion measures to tackle unacceptable behaviour in public procurement such as fraud and exploring the introduction of a centrally managed debarment list. And it proposed reforming the procurement regime to allow past performance to be more easily taken into account in the evaluation.

The Government response to questions 16 to 19 has been combined and is set out after the summary of responses to question 19.

Q13: Do you agree that the award of a contract should be based on the “most advantageous tender” rather than “most economically advantageous tender”?

Summary of responses

In total there were 492 responses to this question and a clear majority (77%) of the respondents agreed with the proposed switch from Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) to Most Advantageous Tender (MAT). Respondents believed this would be an important change and further encourage contracting authorities to take account of social value in the award of public contracts. Respondents also believed the change would help procurements to focus on long term market sustainability and would encourage innovation.

There were concerns raised that moving away from the term “economically” would reduce the focus of the evaluation on value for money, and might create barriers for SMEs who might not have the capability or capacity to invest in projects in a way that would score well against a MAT evaluation. and there were a number of requests for guidance and support to help contracting authorities carry out evaluations based on MAT with examples of relevant award criteria that would be consistent with HMT’s Managing Public Money.

Government Response

The Government intends to introduce the proposal into legislation as described in the Green Paper.

Rather than referring to MEAT, contracts will be awarded on the basis of MAT. This change in terminology will provide further clarity for contracting authorities that when determining evaluation criteria, they are able to take a broader view of what can be included. It will support levelling up by encouraging contracting authorities to give more consideration to social value when procuring public contracts in their areas.

To address concerns about the potential burden on SMEs, we intend to ensure that award criteria used are required to be proportionate to the requirement by embedding concepts of proportionality as described in the response to question 1.

Q14: Do you agree with retaining the basic requirement that award criteria must be linked to the subject matter of the contract but amending it to allow specific exceptions set by the Government.

Summary of responses

There were 424 responses to this question and a majority (69%) were supportive of the proposals set out. Many believed that this measure could help deliver cross-government objectives. There were a number of suggestions for policy areas which would benefit particularly from this measure, for example Net Zero policy and Modern Slavery. Some respondents also indicated that training and guidance would be needed across the public sector to ensure that all buyers have sufficient confidence to carry out evaluations prior to using the exceptions.

Those who opposed the proposals stated that this measure could lead to evaluations becoming more complex and expensive if multiple exceptions were introduced into individual procurement projects. Further concerns were raised that there could be an increased risk of challenge where the criteria are ambiguous and it could lead to additional burdens on contracting authorities to robustly justify using such exemptions. Some suggested that the change would be inconsistent with local government legislation (i.e. section 17 of the Local Government Act 1988) which does not allow non-commercial considerations to be applied. A few respondents commented that SMEs and VCSEs may be dissuaded from bidding due to perceived disproportionate requirements.

Many respondents also commented that it would be beneficial for the Government to produce a full list of proposed exemptions in order to encourage consistency by contracting authorities in designing evaluations and to avoid the aforementioned concerns around disproportionate requirements.

Government Response

The Government intends to introduce the proposals into legislation as described in the Green Paper.

We will seek a power in the new legislation for a Minister of the Crown to make secondary legislation to reflect policy priorities that may have the effect of award criteria not being related to the subject matter of the contract. We are still considering whether the Minister will have the power to require contracting authorities to have regard to a relevant policy or whether this will be permissive.

The relevant policy areas where such criteria apply will be explicitly set out in the relevant secondary legislation. In order to address concerns raised about increased risk of challenge where such exemptions may be used inappropriately, we intend to include the following provisions in primary legislation:

- the overriding requirement for contracting authorities to comply with the principles of non-discrimination, transparency and fair treatment (equal treatment and procedural fairness) will remain and the effect of any measures must not have the effect of undermining or conflicting with this;

- in exercising their power to allow or require contracting authorities to break the link, the Minister will not amend any other requirements of the award criteria principles, including proportionality;

- award criteria unrelated to the subject matter of the contract will only be implemented strictly as set out by the Minister; contracting authorities will not be able to decide to apply unrelated award criteria in the absence of specific secondary legislation.

There were some concerns raised that the proposal to allow the removal of the link to the subject matter of the contract for award criteria in certain situations does not align with section 17 of the Local Government Act 1988. This legislation requires certain public procurement functions to be exercised by local authorities without reference to non-commercial considerations. Therefore, if local authorities are applying award criteria which are not linked to the subject matter of the contract, for example in respect of asking bidders to demonstrate commitment to creating jobs in their local area, this could conflict with the requirements of section 17 as it is a non-commercial consideration. We are proposing to introduce a power to disapply section 17 in certain circumstances, to ensure local authorities have the same freedoms to exercise the reforms as other contracting authorities.

Q15: Do you agree with the proposal for removing the requirement for evaluation to be made solely from the point of view of the contracting authority, but only within a clear framework?

Summary of responses

There were 404 responses to this question with the majority (58%) agreeing with the proposal. However, many wanted to see more information on how this would work in practice. Those in support commented that it would help to reinforce social value and give a greater focus on outcomes and solutions for communities, which would be especially helpful for those local authorities that have established local priorities. Some respondents commented that having this flexibility would allow for a more holistic approach to evaluation of tenders.

Those respondents (17%) who disagreed with the approach felt that adding more requirements to the scope of tender evaluation would increase resource pressures on contracting authorities or increase the risk of conflicts of interest or fraud.

Government Response

The Government intends to introduce the proposal into legislation as described in the Green Paper.

We will make clear that it is for the contracting authority to determine whether the evaluation should be made solely from its own point of view, or taking a broader perspective, for example by taking into account benefits or costs for contract users that may be outside the authority. Recognising concerns about unintended consequences, we plan to publish clear guidance so that procurers are well equipped to implement this new approach appropriately.

Q16: Do you agree that, subject to self-cleaning, fraud against the UK’s financial interests and non-disclosure of beneficial ownership should fall within the mandatory exclusion grounds?

Summary of responses

There were 377 responses to this question. A clear majority (90%) were supportive of the proposal. Reasons for support were mixed, with some welcoming any measures to strengthen the UK’s stance on corruption and transparency in procurement, while others thought that the changes would make procurements more robust. Some felt that the Government should go further and widen the exclusion grounds to include conviction for any kind of fraud, whether against the UK Government or other interests.

However, many respondents made their support conditional on the provision of clear guidance on the scope of the new grounds for exclusion, the evidence required to exclude a supplier, and what would constitute effective self-cleaning. This was a particularly prevalent view among some contracting authorities including from local government. A related point made by some respondents was that the proposed new grounds for exclusion, in particular with regard to beneficial ownership, would be difficult to enforce without central government action to align databases and other sources of information in order to allow contracting authorities to easily check which suppliers meet the grounds. Many respondents argued that non-disclosure of beneficial owners should be a discretionary ground instead of mandatory, both because it was seen as comparatively less serious than the other mandatory grounds, and because some respondents thought that suppliers might have reasonable excuses for not providing this information. This view was particularly prevalent among respondents from the legal profession.

Q17: Are there any other behaviours that should be added as exclusion grounds, for example tax evasion as a discretionary exclusion?

Summary of responses

There were 302 responses to this question. A wide range of possible exclusion grounds were suggested. The most popular suggestion was tax evasion, proposed by 164 respondents (54%).

Other common suggestions included:

- Modern Slavery (65 responses);

- environmental misconduct (34 responses);

- poor performance (23 responses);

- data protection failures (22 responses);

- health and safety violations (18 responses).

Some respondents were clear that exclusions should only apply where a relevant regulatory requirement had been breached. A smaller number of responses recommended using exclusions as leverage to advance the Government’s priorities and social value goals, with a small number advocating that suppliers should have to positively demonstrate their alignment with the public good in order to be able to participate in a tender.

As with the other questions relating to the grounds for exclusion, many respondents called for more clarity and guidance on the scope of the grounds and on how contracting authorities should assess suppliers. Some respondents made the point that local authorities should not be expected to have the resources or expertise to assess suppliers’ compliance on complex issues such as tax. A smaller number advocated for abolishing discretionary exclusion grounds, because of the relative complexity and risk of challenge to contracting authorities in using them, and just having mandatory exclusions.

Q18: Do you agree that suppliers should be excluded where the person/entity convicted is a beneficial owner, by amending regulation 57(2)?

Summary of responses

There were 359 responses to this question. The majority (75%) were supportive of the proposal that suppliers should be excluded where the person/entity convicted is a beneficial owner. Many supportive respondents stated that this measure would improve transparency and accountability in public sector procurement. Some stated that including beneficial owners would underline the message that supplier behaviour is often influenced by owners and senior leaders.

The most common concern across respondents from all sectors was defining what constitutes ‘beneficial ownership’, with respondents questioning how this would apply to different types of organisation including voluntary sector groups. As with the other exclusions questions, there was a clear concern from contracting authorities that guidance and support was needed to understand how to apply the exclusions to beneficial owners, and to enable due diligence to be done to verify supplier self-declarations. Some respondents felt that misconduct by beneficial owners should fall under the discretionary exclusion grounds, given the link to the risk posed by the supplier was not always clear-cut. Others felt that this was a matter for self-cleaning evidence to address.

VCSEs raised a particular concern around ensuring that the regime did not contravene the ethos behind the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act. They noted that, for many charitable organisations delivering services to people in the criminal justice system, those running the charity were often ex-offenders and may be subject to an exclusion ground for conviction of beneficial owners. Some argued for spent convictions to be exempt from the regulations.

Q19: Do you agree that non-payment of taxes in regulation 57(3) should be combined into the mandatory exclusions at regulation 57(1) and the discretionary exclusions at regulation 57(8)?

Summary of responses

There were 360 responses to this question. A clear majority (78%) were supportive. Most comments agreed that the proposal would help to simplify the exclusions regime. Some respondents argued that non-payment of taxes should either be a mandatory exclusion ground or discretionary, but not both. Others thought that non-payment of taxes was the wrong standard to apply, and that exclusion should be based on the criminal offence of tax evasion, or on a broader measure of good tax compliance. This often reflected a view that it was not the responsibility of contracting authorities to enforce tax compliance on behalf of HMRC; there was also an argument that exclusion would be disproportionate if only small amounts of tax were outstanding. A clear concern from contracting authorities was that the complexity of tax affairs exposed them to significant legal risk in excluding suppliers for non-payment. Contracting authorities wanted clear guidance on when this exclusion should apply, how to verify the tax status of suppliers – ideally via a central database – and what constituted good self-cleaning evidence.

Government Response to questions 16-19

The Government intends to introduce most of the proposals into legislation as described in the Green Paper.

However, it was clear from the consultation responses and from further engagement with stakeholders that in addition to these changes, a wider refresh of the legal framework for exclusions is needed. Many respondents noted that they found the existing regulations unclear and confusing. They highlighted ambiguities and inconsistencies around the scope of the exclusion grounds, the individuals and entities which need to be considered for the purpose of applying the exclusions to suppliers, the time period in which past misconduct can be considered, and the process to be followed to exclude suppliers. These concerns were common to all stakeholder groups, but particularly prominent among contracting authorities, who bear responsibility for considering the exclusion of suppliers from procurements on a case by case basis.