Human Rights and Democracy Report 2013

Updated 24 June 2014

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

Front cover - Syrian woman and baby. Photo Credit: UNHCR / S. Rich / April 2013

Executive Summary

This report provides an overview of activity in 2013 by the FCO and its diplomatic network to defend human rights and promote democracy around the world. It also sets out the analysis on country situations and thematic issues which directs that work.

An important new focus in 2013 was the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative (PSVI), which will reach another milestone on 10-13 June 2014, when the Foreign Secretary and the Special Envoy of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie, will co-chair a global summit on ending sexual violence in conflict. Other initiatives prioritised in 2013 were:

- the defence of freedom of religion or belief worldwide;

- agreement on the world’s first treaty to control the arms trade;

- the UK’s election and return to the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC); and

- the launch of the UK Action Plan on Business and Human Rights.

Our work to underpin democracy, defend freedom of expression, and promote wider political participation has included contributions through election observer missions and the Westminster Foundation for Democracy. In conjunction with many NGOs and civil society organisations, we have supported human rights defenders - courageous people who often face repression and harassment.

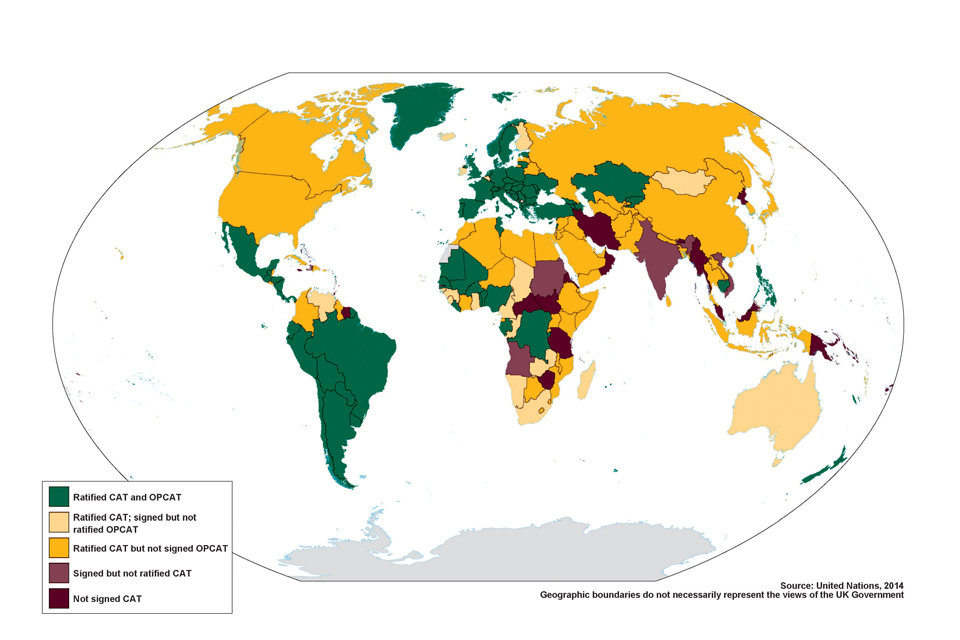

The UK has championed the rule of law overseas, working with national and international NGOs and through the UN on torture prevention initiatives. We have campaigned for states to ratify the Convention Against Torture and its Optional Protocol. Abolition of the death penalty remains a top priority, and we continue to lobby against its use in any circumstances, anywhere. Support for international criminal justice continues to be a fundamental element of our foreign policy. We support the International Criminal Court and other tribunals.

Freedom of religion or belief remains under threat. We have taken action, through project work in several countries, at the multilateral level (UN resolutions, EU advocacy), and by bringing together faith and political leaders to extol the benefits of pluralism.

At the Commission on the Status of Women, we took its 2013 theme, “the elimination and prevention of all forms of violence against women and girls”, and worked for agreed standards against which civil society can hold governments to account.

We promoted children’s rights through the UN, by co-sponsoring the omnibus resolution and, in this and other fora, strove to ban child labour. Bilaterally, we pressed countries to end forced and early marriage, and sexual exploitation.

We advocated a UNHRC resolution to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights internationally and, alarmed by reactionary legislation in several countries, including in the Commonwealth, combined lobbying with funding and working on practical projects to help protect communities at risk. In the EU we have supported the development of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) guidelines, which will be used by EU Delegations globally to promote LGBT rights.

The UK’s counter-terrorism work focuses on capacity building with the police and the judiciary, in ways which protect human rights and respect for the rule of law, thanks to our Overseas Justice and Security Assistance Guidance.

The adoption of a legally-binding Arms Trade Treaty was the culmination of seven years of work within the UN. On 3 June, the UK was amongst the first to sign. Underpinning our counter-proliferation efforts is our stringent export licensing regime.

We remain concerned by the number of conflicts worldwide. The UK National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security will help us reduce the impact of conflict on women and girls, and include them in conflict resolution. We continue to work through the UN on the protection of civilians and children in armed conflict.

Widespread implementation of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights is an important and achievable goal. In 2013, the UK became the first country to publish its own Action Plan on Business and Human Rights. We also work through other organisations, such as the EU, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the UN, to promote responsible business practices and combat corruption.

Protecting the human rights of the British community overseas is a priority for us. UK officials work with British nationals on a wide range of issues with human rights implications, from imprisonment to forced marriage, female genital mutilation and child abduction.

The UK takes seriously its responsibility for the security and good governance of the UK Overseas Territories. In 2013, the UK and territory governments pursued their programme to extend core UN human rights conventions to territories where this had not yet happened.

The final section of the report contains a review of the human rights situation in 28 countries where the UK government has wide-ranging concerns. We will continue to report on the countries of concern on a quarterly basis.

Foreword by Foreign Secretary William Hague

Foreign Secretary William Hague

This report sets out the steps we have taken to promote and protect human rights over the course of 2013. It was a tumultuous year, with setbacks, as well as successes. Human rights opportunities and obligations inspired our diplomats in every corner of the world, and shaped our policies in every forum. For that reason, though long, this report is far from comprehensive. It marshals information from across the Foreign & Commonwealth Office network, partner governments, international organisations and civil society, seeking to highlight themes, trends and priorities.

A key UK human rights objective is to end impunity for sexual violence in conflict, so we have added a new chapter on our efforts in this area. At a global summit in June, we will set out to turn the tide of global opinion so that we make accountability for these crimes the norm. We have expanded last year’s chapter on the Human Rights and Democracy Programme Fund to look more widely at the impact of our human rights initiatives: for example, our work on the Arms Trade Treaty and on freedom of religion or belief, publication of our Action Plan on Business and Human Rights, and the UK’s election to the UN Human Rights Council.

As before, the report contains a section on “countries of concern”. It follows a careful review of all countries with serious human rights problems, and was tested against criteria which are objective and widely-used. Our evidence base is robust. As a result of this analysis, we have added the Central African Republic to the list of “countries of concern”.

We have seen more turbulence in the Middle East, with Egypt suffering particular upheaval. South Sudan and Ukraine also stand out as examples of countries where the path to full democracy continues to be difficult. Most tragically of all, we will soon mark the third anniversary of conflict in Syria. A regime that claims to be fighting terrorism is terrorising its own people, using starvation and hunger as weapons of war. The UK has committed £600 million in humanitarian aid, our biggest ever contribution to a single crisis, and has been one of the most active countries in helping to push forward the “Geneva II” process.

I am deeply troubled by reactionary legislation and increasing persecution of the LGBT community in many parts of the world. The UK will remain active, both in close cooperation with expert NGOs and local communities. We will speak up, in public and in private, to protect individuals from discrimination and violence. And we will keep on working to build tolerant and pluralist societies in the long run, which is core business for our diplomatic and development strategies worldwide.

There were some positive developments in human rights during 2013. In January, the Burmese government signed a historic initial peace agreement with the Karen National Union after 63 years of conflict, although we continue to be concerned by the treatment of the Rohingya population in Rakhine state. Tunisia has sustained its democratic transition, and the Prime Minister’s decision to go to November’s Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Sri Lanka helped shine a spotlight on the situation there. We will work through the UN Human Rights Council to ensure that the search for lasting peace and reconciliation in Sri Lanka benefits from an appropriate international investigation.

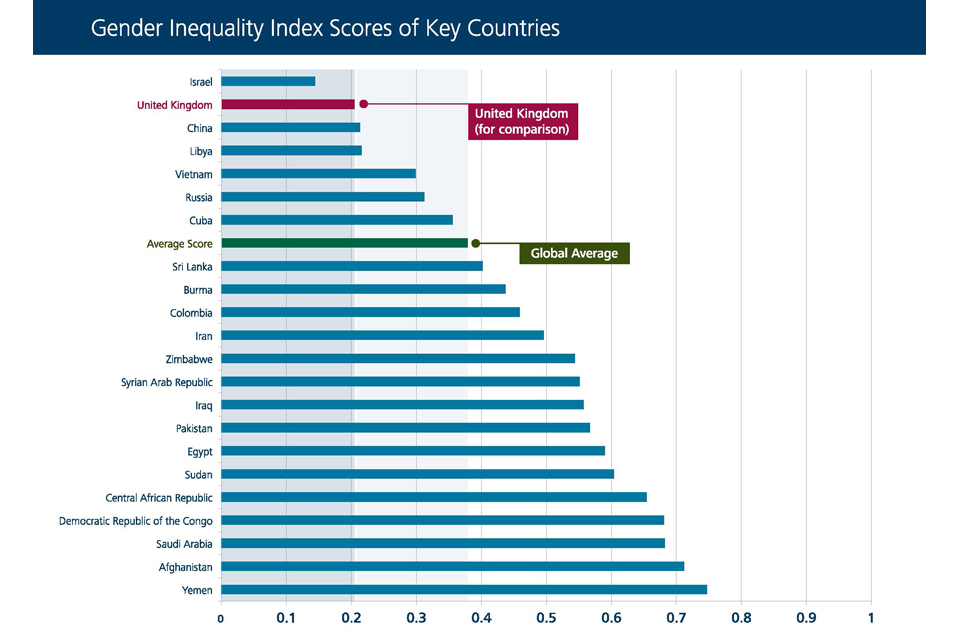

As promised during our campaign for re-election to the Human Rights Council, in 2014 the UK will protect those most vulnerable in society, promote human dignity for all, respond proactively to evolving challenges, and keep human rights at the heart of all our multilateral work. I am also determined that 2014 should see progress on what I believe is the greatest strategic prize of the 21st Century: full political, economic and social participation for all women everywhere. Events in many countries show that we can never take for granted the hard-fought gains in gender equality. They must be defended and expanded constantly.

On these and many other pressing issues, I look forward to working in 2014 with the members of my Advisory Group on Human Rights, who provide me with invaluable expertise and frank advice. I and my ministerial team hope this year’s report will help make support for action to promote and protect human rights as universal as the rights themselves. They are the most precious thing we have in common.

Foreword by Senior Minister of State Baroness Warsi

Senior Minister of State Baroness Warsi

Since my appointment as Minister with responsibility for Human Rights at the Foreign & Commonwealth Office in September 2012, I have been constantly torn between pride at what we have achieved, and frustration at how much more needs to be done.

Over the course of 2013, we have made good progress on our six global thematic priorities: women’s rights; torture prevention; abolition of the death penalty; freedom of expression on the internet; business and human rights; and freedom of religion or belief.

We have worked hard, with international partners, to end the impunity that surrounds the use of rape and sexual violence as a weapon of war. In April, during our G8 Presidency, we secured an historic G8 Declaration that recalled that rape and serious sexual violence in armed conflict are war crimes and also constitute grave breaches of the Geneva Convention. In June, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 2106, strengthening the UN’s capability to tackle this issue, while in September, at the UN General Assembly, we put forward a new Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, which has to date been endorsed by 141 countries.

On 26 June, I launched a campaign for increased ratification of the Convention Against Torture and its Optional Protocol. During 2013, Vietnam signed the Convention and both Norway and Burundi ratified the Optional Protocol. We will continue to persuade more states to do likewise in the months ahead.

We have worked with civil society and international organisations to influence those states that still use the death penalty. The most recent vote at the UN reinforced a global trend towards abolition, with 111 states voting in favour of a worldwide moratorium.

We continued to defend freedom of expression, online as in traditional media, and issued a toolkit and guidance to all our embassies about how to support human rights defenders further.

We also became the first country to publish an action plan to implement the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human rights. By working seamlessly across government and business to show how “human rights due diligence” is good for the bottom line, we will encourage other countries to follow our lead.

As the UK’s first Minister for Faith, defending and promoting freedom of religion or belief remains a personal priority for me. The rising tide of persecution across the world has been a particular focus. On 15 November, speaking in Washington, I called for a cross-continent, cross-religion response to a pattern of intolerance and sectarianism which has led to the persecution of minority communities, including a mass exodus of Christians from places where they have co-existed with the majority faith for generations.

In January and September, I brought together foreign ministers and senior diplomats from across the world, to deepen and strengthen the political consensus on Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18. We achieved that. Now is the time to see 16/18 implemented.

Violent episodes around the world have strengthened my conviction that freedom of religion or belief increasingly represents a frontline for promotion and protection of human rights. I am determined to use my position in the UK government and my network of expert advisers and international colleagues to stem the tide of violence committed in the name of religion.

In July 2013, working with “Remembering Srebrenica”, the UK became the first county to mark Srebrenica Memorial Day. Srebrenica was a stark demonstration of what can happen when hatred, discrimination and evil are allowed to go unchecked. Our commemoration of this genocide underlies our commitment to learn from the past, and to help ensure Bosnia and Herzegovina’s future as a stable, inclusive and peaceful country.

In addition to my responsibilities on human rights throughout the world, three countries where we have significant human rights concerns feature in my portfolio.

When I visited Afghanistan in March and November, I was struck by how far it has come since 2001 and the determination of the Afghan people to hold on to the gains made in all areas of society. However, the Afghan people, particularly women and girls, continue to face many challenges in the realisation of what are fundamental human rights. But the UK will remain committed to helping Afghanistan consolidate the progress made over the last ten years.

With regards to Pakistan, I congratulate the Pakistani people for placing their trust in democratic institutions in 2013. However, I am mindful of the wide-ranging and serious human rights issues the country still needs to tackle. I have not shied away from raising difficult human rights issues with the Pakistani government, and we will continue to support the people of Pakistan in their fight against terrorism and violent extremism.

In Bangladesh, it was hugely disappointing that the January 2014 elections were marred by political violence throughout 2013 and on elections day itself. I have also been deeply concerned by the negative impact labour strikes, protests and disruption have had on Bangladesh’s economy. We continue to encourage political dialogue, greater democratic accountability, and capacity building for participatory elections in the future, without the fear of intimidation or reprisals.

In the battle to translate international obligations and commitments into practical action, I am privileged to work with a wide range of human rights experts through the Foreign Secretary’s Advisory Group on Human Rights, and the sub-groups I chair on torture prevention, abolition of the death penalty, and freedom of expression on the internet. To strengthen this network, we have created a Sub-Group on Freedom of Religion or Belief, which I will also chair. These groups bring together NGOs, academics, parliamentarians and business representatives to ensure that our policies benefit from the best external expertise.

The start of 2014 presented major challenges for human rights, not least in Syria, the Central African Republic and Ukraine. But we remain committed to defending human rights because any violation is a threat to global peace and security. I want to pay particular tribute to the work of the brave women and men who risk their own lives to defend the rights of others. Their voices must be heard, in their own countries, and in every corner of the world.

Section I: Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative

Sexual violence in conflict is widespread. It affects not only large numbers of women, but also men and children. In addition to the physical and psychological trauma suffered by survivors, sexual violence adds to ethnic, sectarian and other divisions, further entrenching conflict and instability. It destroys lives, creates refugees and is often just one of a number of human rights abuses individuals and communities face.

The UK government believes that combating sexual violence in conflict is an issue of common humanity and an issue of conflict prevention. The culture of impunity that exists for sexual violence in conflict feeds conflict, and undermines peace and security in post-conflict countries. The Foreign Secretary believes that the UK has the moral obligation and the diplomatic power to change this. That is why, on 29 May 2012, he launched the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative (PSVI) with the Special Envoy of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie.

What does the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative seek to achieve?

PSVI aims to address this culture of impunity - and to increase the number of perpetrators held to account - by raising awareness, rallying global action, promoting more international coherence, and increasing the political will and capacity of states to prevent and respond to these crimes. It complements wider government work on women, peace and security and violence against women and girls.

The Foreign Secretary undertook to use the UK’s Presidency of the G8 in 2013 to ensure greater international attention and commitment to tackling the use of sexual violence in conflict, and to secure a clear political statement from the international community of its determination to make real, tangible progress on combating the use of sexual violence in conflict. This political campaign has been supported by a range of practical measures, including continued deployments of the UK Team of Experts, established as part of PSVI in 2012, and further support to the UN and other organisations.

What progress has PSVI made in 2013?

International commitment to tackling sexual violence in conflict

During 2013, the UK has worked to build political commitment and global momentum to tackle sexual violence in conflict. On 11 April, G8 Foreign Ministers adopted a historic Declaration on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict. The declaration contained a number of key political and practical commitments. This included agreement from G8 governments that there should be no peace agreements that give amnesty to people who have ordered or carried out rape; that all UN peacekeeping missions should automatically include provisions for the protection of civilians against sexual violence in conflict; that there should be no safe haven for perpetrators of sexual violence; that rape and serious sexual violence in armed conflict constitute grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, meaning that there is an obligation for states to prosecute suspects regardless of nationality; and that there should be new efforts to ensure support and justice for survivors of rape. G8 Foreign Ministers also endorsed the development of a new International Protocol, which will improve global standards in documenting and investigating sexual violence committed in conflict.

The Foreign Secretary speaking at a G8 Preventing Sexual Violence experts meeting in London, 12 February 2013

Building on the G8 Declaration, the Foreign Secretary sought to generate wider support for the campaign at the UN and in other multilateral and regional organisations. On 24 June, during the UK’s Presidency of the UN Security Council, the Foreign Secretary hosted a debate on tackling sexual violence in conflict, which focused on the need to challenge the culture of impunity and hold perpetrators to account. A new UN Security Council Resolution (2106) was adopted during the debate. This was the first resolution on the subject in three years, was co-sponsored by 46 states, and contained action to improve the UN response to sexual violence in conflict.

This political campaign culminated in the Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, which the Foreign Secretary launched on 24 September in the margins of the 68th session of the UN General Assembly.

The declaration was drafted with a range of countries, who also worked alongside the UK to build wider support for the text. It is action-oriented and ambitious, and expresses a shared commitment and determination to see an end to the use of rape and sexual violence as weapons of war. It has a clear focus on accountability and tackling impunity, but also contains a set of wider political and practical commitments. States also reaffirmed in the declaration that rape and serious sexual violence in armed conflict are war crimes, and constitute grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. The declaration has been endorsed by 140 UN member states to date, and we continue to encourage other states to endorse it.

The UK government has also worked with other multilateral organisations to build international support and coherence. The EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission, Baroness Ashton, supported the G8 Declaration, and has since underlined her continued support to exploring areas for coordination and closer cooperation on PSVI. In response to the African Union’s (AU) political commitment to address sexual violence in conflict, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) has been working closely with the AU’s Peace and Security Department, providing technical advice and funding the position of gender advisor; and through the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Sri Lanka in November, the UK obtained commitment from the Commonwealth Secretariat and member states to take action to tackle sexual violence in conflict.

Supporting political commitments with practical action at the national level

Our efforts to generate international political support for tackling sexual violence in conflict have been complemented by engagement and action at the national level to deliver the ambitious set of declaration commitments.

The Foreign & Commonwealth Office has been working with the Department for International Development (DFID), the UN, and others at national level to deliver these commitments. Work with individual countries varies according to the context, and for each we have assessed where the UK can add value to existing efforts. In particular, we have focused on combining political and diplomatic opportunities at national levels with technical support through the use of international and UK expertise, including deployments of the PSVI UK Team of Experts. We have continued to work closely with the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative for Sexual Violence (UNSRSG) and the UN Team of Experts on the Rule of Law to ensure that country engagement is both coherent and sustainable, including through focusing on strengthening national ownership and responsibility, and building local capacity.

Throughout 2013, we have carried out country work in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kosovo, Libya, Mali, Somalia and Syria.

The Foreign Secretary and Special Envoy of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Angelina Jolie visiting Nzolo Displacement Camp, near Goma, eastern DRC.

The FCO is also working closely with DFID on their work to improve international action to protect girls and women affected by violence in humanitarian emergencies. On 13 November, Secretary of State for International Development, Justine Greening, co-hosted a high-level Call to Action with the Swedish Minister for International Development to secure greater commitment from UN agencies, international NGOs and donors to improve the international response to protecting girls and women in emergencies. They agreed to act, or fund action, to prevent and respond to violence against women and girls from the first phase of an emergency, without waiting for evidence of specific instances of violence to emerge. Ms Greening also announced £21.6 million in new funding to help protect women and girls in emergencies.

Support to grassroots organisations working to tackle sexual violence in conflict

At the launch of the G8 Declaration in April, the Foreign Secretary announced new FCO funding of £5 million over three years to support grassroots and human rights projects on tackling sexual violence in conflict. This funding is part of the FCO Human Rights and Democracy Programme.

In 2013, we allocated nearly £2.7 million to support projects to be carried out in financial years 2013-14 and 2014-15. We used this to support 13 projects working to tackle sexual violence in a number of countries including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burma, Colombia, DRC, Guatemala, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sierra Leone and Syria. These projects are aimed at supporting the work of civil society organisations, including women’s organisations and human rights defenders and networks, to improve community-level protection against sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict environments; to help survivors of sexual violence to get better access to justice; and to promote greater accountability by national institutions responsible for tackling sexual violence.

International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict

A key element of PSVI has been the development of a new International Protocol on the documentation and investigation of sexual violence in conflict. G8 Foreign Ministers endorsed the development of the Protocol in April, and this was reinforced through the Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict. The UK is leading the development of the Protocol, drawing on the knowledge of experts from around the world.

The Protocol aims to set out ideal standards for the documentation and investigation of rape and other crimes of sexual violence in conflict. The application of these standards will help to ensure that information collected in conflict and post-conflict settings can support future investigations and prosecutions of sexual violence at the national and international level. These standards will aim to ensure that information is collected in such a way as to increase and preserve its evidentiary value, that survivors receive sensitive and sustained support, and – critically – that those involved in collecting information and working with survivors are doing so in a coordinated and mutually supportive way. It will build on existing local, regional and international guidance and be open to states, the UN system, regional bodies and NGOs for use in training and capacity building programmes.

To develop the Protocol, we have established a number of expert working groups according to thematic areas of expertise. These groups met in May, June and July and have begun working together to draft the Protocol. We also hosted a conference in Geneva in September to discuss the Protocol and to raise awareness of the challenges to documenting and investigating sexual violence in conflict with states, UN agencies, regional organisations and NGOs. In addition to these formal meetings, we have continued to engage informally with key experts on all aspects of the draft. In early 2014, we will carry out grassroots field testing of the Protocol and regional consultation which will feed into the drafting process.

Working through the UN

A central element of our approach has been close cooperation and support for the work of the UNSRSG, Mrs Zainab Hawa Bangura, and her Team of Experts (ToE) on the Rule of Law. In early 2013, we provided £1 million to support work of the ToE, and have also conducted joint assessment missions with them to the DRC and Somalia. We have also seconded a member of the PSVI UK Team of Experts to enhance the UN team’s knowledge of the Middle East and North Africa region, including on aspects of Sharia law. We strongly support the UNSRSG’s efforts to build coherence and coordination in the UN’s response to sexual violence in armed conflict through the cross-UN initiative, UN Action against Sexual Violence in Conflict, as well as her focus on national ownership and responsibility.

We have also continued our support for the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) Trust Fund for Victims, which aims to address directly and respond to victims’ physical, psychological, or material needs. In November 2013, the Foreign Secretary announced a UK contribution of an additional £300,000 to the ICC’s Trust Fund for Victims. This brings the total UK support to the ICC Trust Fund for Victims since 2011 to £1.8 million.

Looking ahead to 2014: the Global Summit on Ending Sexual Violence in Conflict

The focus of our efforts in 2014 will be on turning the political commitments secured so far into concrete action on the ground, thereby creating irreversible movement towards ending the use of rape and sexual violence in conflict.

On 10-13 June 2014, the Foreign Secretary and the Special Envoy of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie, will co-chair a global summit on ending sexual violence in conflict. The UK will invite each government that has endorsed the Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, along with representatives from civil society, judiciaries and militaries from around the world.

We want the summit to deliver practical and ambitious agreements that will once and for all shatter the culture of impunity for rape and sexual violence in conflict. It will deliver a set of practical agreements that bring together and focus the efforts of conflict and post-conflict affected countries, donors, the UN and other multilateral organisations, NGOs and civil society.

We want the summit to identify specific actions by the international community in the four areas where we believe greater progress is necessary. These four areas are:

- to improve investigations/documentation of sexual violence in conflict;

- to provide greater support and assistance and reparation for survivors, including child survivors, of sexual violence;

- to ensure sexual and gender based violence responses and the promotion of gender equality are fully integrated in all peace and security efforts, including security and justice sector reform; and

- to improve international strategic co-ordination.

We will also use the summit to launch the new International Protocol on the Investigation and Documentation of Sexual Violence in Conflict. In addition, we hope to secure agreement to: revising military doctrine and training; improving peacekeeping training and operations; providing new support to local and grassroots organisations and human rights defenders; developing the deployment of international expertise to build national capacity; improved support for survivors; and forming new partnerships to support conflict-affected countries.

There will be a large accompanying “fringe” of events alongside the formal meetings, which will take place across the world as well as in London. We hope this will be used to discuss a broader range of issues related to sexual violence in conflict, including conflict prevention, women’s rights and participation, men and boys, children affected by conflict, international justice, and wider issues of violence against women and girls. These will be an opportunity to showcase programmes and policies from around the world that have been successful.

Section II: UK Human Rights Initiatives, 2013

Human rights work across the world is never easy, and progress is often measured in decades rather than months or years. Within the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO), much of our human rights work is integrated into the day-to-day operations of our embassies and high commissions overseas and our teams in the UK, sometimes through discrete human rights projects or activities, often through the wider work they do to promote our political, security and prosperity objectives.

In this year’s annual report we want to highlight four human rights initiatives which the FCO prioritised in 2013: action to defend freedom of religion or belief around the world; agreement on the world’s first treaty to control the trade in arms; our election and return to the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC); and the launch of the UK Action Plan on Business and Human Rights. These four initiatives marked a successful year for our human rights work, and show the tangible difference that sustained and focused effort can make.

In addition to these initiatives, the Human Rights and Democracy Programme Fund continued to fund a portfolio of human rights projects to catalyse change, support democratic development, and help improve specific human rights situations in over 40 countries worldwide. The Department for International Development (DFID) also continued its work to support the human rights of poor and marginalised people in developing countries with the objective of ensuring that everybody can enjoy the economic, social, civil, political and cultural rights defined in internationally agreed human rights treaties.

Freedom of Religion or Belief

2013 has seen a rising tide of restrictions on freedom of religion or belief. Baha’is, Shias, Sunnis and Alawites, Hindus, Sikhs, atheists, Christians and many others have fallen victim to a new sectarianism that is breaking out across continents. For that reason, the FCO has ramped up its activities to promote freedom of religion or belief across the world.

We have done this in several ways. First, through multilateral organisations. We have continued our programme to support implementation of UNHRC Resolution 16/18 in individual countries. This resolution lays the foundation for combating discrimination against people based on their religion or belief. Political consensus is crucial in this area, so Senior Minister of State, Baroness Warsi, has brought together ministers and senior officials, from the Foreign Minister of Canada to the Secretary General of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, starting in London in January. She then held a further meeting in New York during UN General Assembly week in September. Follow-up meetings are planned in 2014, with an emphasis on building support for widely applicable practical solutions to sectarianism and violence, including the social, economic, and other benefits of pluralism.

Second, through bilateral engagement. Baroness Warsi has made freedom of religion or belief an FCO priority, and now every minister at the FCO is an ambassador for religious freedom, raising and promoting these issues in the countries with which they engage.

Third, through projects. We have worked hand-in-hand with NGOs, and human rights and faith-based organisations across the world. For example, we have helped to strengthen a network of human rights defenders working on this issue in South East Asia.

And fourth, training and expertise. The FCO is equipping its diplomats with the tools to appreciate and influence the role religion plays in global politics today. In addition, the Foreign Secretary has established a sub-group of his advisory group on human rights, which will focus on freedom of religion or belief. It will meet every six months and bring together a range of experts in the field, chaired by Baroness Warsi. It will make recommendations to the FCO to help us sharpen our work in this area.

In 2014, by these means and others, the FCO will strengthen the role and capacity of political, community and faith leaders to tackle religious intolerance. We will seek to build a cross-faith, cross-continent response to the problem, with a positive, practical focus on promoting the benefits of religious tolerance, pluralism, mutual respect and understanding.

Arms Trade Treaty

After seven years of work, the Arms Trade Treaty was adopted on 2 April 2013 at the UN General Assembly. An overwhelming majority of states (156) voted in favour of the treaty. Only three voted against (Iran, Syria and North Korea). This was a significant achievement for British diplomacy. The UK was one of seven countries that launched the campaign for the treaty, and we were one the first countries to sign the new treaty. At the time of writing, 116 states had signed the treaty and nine had ratified. The UK government signed on 3 June, and we expect to ratify the treaty early in 2014.

The Arms Trade Treaty now needs to be implemented effectively and globally. It contains the building blocks for a safer, more secure world. It requires states to refuse to export arms if there is an unacceptable risk that they will be used in serious violations of human rights. For the first time, it imposes legally-binding rules on the small arms that cause the greatest harm to innocent civilians. It will increase transparency and create a framework for calling the irresponsible to account. The UK has already pledged more than £400,000 to help other countries meet these standards.

UK election to the UN Human Rights Council

The UNHRC is an intergovernmental body within the UN system responsible for the promotion and protection of human rights around the globe. It is the premier world body on human rights, and has proven its ability to address mass atrocities and human rights violations and abuses across the world. The UNHRC is made up of 47 UN Member States, elected for three-year terms. Membership of the UNHRC brings the opportunity to influence the international human rights agenda, both by speaking and voting on issues brought before it by others, and by promoting within the UNHRC issues important to the UK. Election to the HRC for the term 2014-2016 was a priority for the UK government in 2013.

Baroness Warsi launched our election campaign in December 2012. During 2013, we used our diplomatic network to seek support from as many countries as possible, talking to them about our human rights policy pledges and commitments, which outlined our approach to human rights in the UK and our aspirations for the UNHRC. Our campaign was global, as illustrated by the Foreign Secretary’s specially recorded YouTube message.

The elections took place in November in New York. The UK was elected with 171 votes; which gives us a strong mandate as we take our seat on the UNHRC in January 2014.

During 2014, the UK will be active at the UNHRC on country-specific resolutions, and in thematic areas including freedom of religion or belief, preventing sexual violence, and business and human rights.

Publication of UK Action Plan on Business and Human Rights

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) were endorsed by the UNHRC in 2011. This framework comprises a three-pillar structure, distinguishing the state’s duty to protect human rights, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, and access to remedies. On 4 September 2013, the UK published its national action plan, “Good Business”, becoming the first country to have such a plan for the implementation of the UNGPs. The UK Action Plan was launched jointly by the Foreign Secretary and the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, Vince Cable.

The UK Action Plan embodies our commitment to protect human rights by helping UK companies respect human rights wherever they operate, in pursuit of respect for people’s human rights and sustainable business environments the world over. We want to help British companies to succeed, and for the UK to continue to show a lead on business and human rights, given the global reach and impact of UK business. The plan was developed in consultation with companies, trade unions, civil society organisations, academics and colleagues across government.

The action plan sets out our commitment to:

- implement UK government intentions to protect against human rights abuse involving commercial enterprises within UK jurisdiction;

- support, motivate and incentivise UK businesses to meet their responsibility to respect human rights throughout their operations, both at home and abroad;

- support access to effective remedies for victims of human rights abuse involving businesses within UK jurisdiction;

- promote understanding of how addressing human rights risks and impacts can help build business success;

- promote international adherence to the UNGPs, including for states to assume their duties to protect human rights and assure access to remedies within their jurisdiction; and

- ensure policy consistency across the UK government on the UNGPs.

We will report back each year on progress in the Annual Human Rights Report, and we commit to bring out an updated version of the action plan by the end of 2015.

The Human Rights and Democracy Programme Fund

The Human Rights and Democracy Programme (HRDP) is a dedicated source of funding within the FCO for human rights work overseas. In the financial year 2013-14, we allocated £6.5 million of funding to support 83 projects (with 26 of them running into financial year 2014-15), ranging in scale from £9,000 to £517,000. Most projects are delivered by civil society implementers working in coordination with the local British Embassy or High Commission.

In 2013, the HRDP had eight specific target areas, aligned with the FCO’s human rights priorities. These included preventing sexual violence, after the Foreign Sectary announced on 11 April that the FCO would spend £5 million over three years on projects tackling sexual violence. By focusing our efforts in this way, we believe we achieve greater impact. The areas were:

- discrimination against women;

- freedom of expression;

- business and human rights;

- abolition of the death penalty;

- global torture prevention;

- freedom of religion or belief;

- democratic processes; and

- preventing sexual violence in conflict.

Projects were required to focus on one or more of these issues and dovetail with the human rights work of the local British Embassy or High Commission. We gave priority to projects in countries of concern, or in countries where there were particular opportunities to promote and protect human rights. We encouraged bidding for projects in these countries, and 54% of funding was eventually committed to them.

An underlying objective of the HRDP is to promote the development of local civil society organisations. Even when we work with international implementers, we therefore strongly encourage them to use local partners in order to help expand their experience and develop their capacity.

Examples of HRDP-funded projects can be found throughout this report. Below are some case studies of work the programme supported in 2013.

Tackling violence against women

In Colombia, the British Embassy worked with local NGO Corporación Excelencia en la Justicia (Excellence in Justice Corporation) and the Attorney General’s Office to strengthen its capacity to prosecute crimes of sexual violence, and to increase awareness of the services available to survivors. The project delivered to government agencies a diagnosis of the obstacles in the justice system for victims of sex crimes in two main cities of Colombia. This diagnosis fed into a handbook for prosecutors, providing a practical tool to public officers investigating and prosecuting sexual violence, who regularly face a multiplicity of protocols and long manuals. The project outputs feed into a wider reform process led by the Attorney General, who is developing a new protocol for investigation and a future capacity-building programme for prosecutors, which the HRDP will support in 2014-15.

In the Kurdish region of Iraq, we funded the training of police and civilian staff from Family Protection Units to deliver an introductory course on “an effective police response to violence against women”. The curriculum and training manual was developed in partnership with local police, and is being incorporated into its academy’s own training programmes. The integrated EU rule of law mission (EUJUST LEX) also used the manual in its domestic violence prevention training with the Ministry of the Interior, reinforcing and multiplying the manual’s messages. Through this project we have been able to influence the police training curriculum, strengthening the content covering the response to violence against women.

In Anguilla we funded training for all frontline police officers and the Department of Probation on handling domestic violence cases. Selected officers were trained as trainers, who then facilitated comprehensive, high-quality training for the rest of their colleagues. A domestic violence “pocketbook” for officers was also produced. The course has improved the quality and sensitivity of the response to victims, provided specific guidance for officers, and increased awareness of a largely ignored issue. In press events promoting the training, the Minister for Home Affairs in Anguilla committed to passing domestic violence legislation.

Ensuring women’s participation in policy making

Women are under-represented in decision-making and public life in Burma. Through Action Aid and the British Council, we funded an empowerment project which supports and encourages Burmese women to take up leadership roles, promote women’s rights, and participate fully in the decisions that affect them. Participants belonged to different ethnic groups, and came from states and regions across the country. The project also successfully trained 100 senior government officials from a number of departments, including the Department of Social Welfare, on “Gender and the UN Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination against Women”. This increased their understanding and capacity to implement Burma’s first “National Strategic Plan on the Advancement of Women”, which was officially launched in October, and sets out the country’s priorities in this area from 2013-22.

In Colombia, we are helping the Organisation of American States’ Mission with supporting the Victims’ Unit to improve the participation of female victims in policy-making related to services and reparation for victims. The project designed a methodology for capacity building that has been adopted by the Victims’ Unit, and that will be replicated nationally. Action plans with specific commitments by local governments will be delivered in March 2014.

Supporting freedom of expression

The space for political debate has grown in Burma over the last couple of years, but existing legislation relating to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly still falls short of international standards. Through Article 19, a London-based international NGO, we funded a project to develop the capacity of legislators, civil society, media and ministries to amend and draft new legislation in this area. By bringing together stakeholders with an interest in promoting freedom of expression, such as media and civil society, a network has been formed to agree an “agenda for change”, which outlines the laws and policies needing reform in the years ahead. Article 19 also provided an analysis of existing laws which civil society can use for further advocacy activities.

In Russia, we are supporting a project aimed at contributing to greater freedom of expression, promoting equality and fighting discrimination, by equipping journalists with the skills to report ethically, responsibly and inclusively on ethnic, race and religious diversity in their regions. The project is being implemented in four Russian regions where there is a high level of ethnic tension: Dagestan, Stavropol, Saratov and Sverdlovsk. As part of the project, the Media Diversity Institute and the Russian Union of Journalists organised a number of training sessions on inclusive journalism and tolerant reporting on diversity for young journalists. One of the most important ways to overcome negative trends, including “hate speech” and labelling, is working together with experts and journalists towards improving the quality of reporting in the Russian media.

Torture prevention

In summer 2013, Kazakhstan adopted a National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) law, which should make it easier to prevent and detect torture within the justice system. However, there was concern that implementation would be delayed, as the capacity of the Ombudsman Institution and civil society organisations to form the NPM still needed further development. Through our Embassy, we funded a project implemented by Penal Reform International, based on a partnership between the Ombudsman Institution and civil society. It provided expert support in drafting specific regulations and rules for the formation and operation of the NPM, facilitated the election of its Coordination Council, and contributed to the training of potential NPM members (nearly 100). The Coordination Council, approved in January 2013, largely consisted of civil society representatives and academics, making the council stronger and helping to ensure its independence.

Freedom of religion or belief

In 2013, the British Embassy in Indonesia funded a project that focused on raising awareness amongst religious leaders of women’s rights. Human rights activists have reported that some recent by-laws have abrogated certain women’s and minority rights (particularly religious minorities). The project sought to ensure that, through training and awareness-raising, future by-laws will better comply with human rights standards.

Since 2011, our Embassy in Iraq has supported the Grassroots Religious Reconciliation Initiative, run by the Foundation for Relief and Reconciliation in the Middle East. The initiative promotes reconciliation in Iraq through dialogue between religious leaders across the sectarian divide at grassroots level. The leaders have established a monthly Peace Council and have had wide outreach, engaging with audiences across the country in key areas of instability. The relationship between the council members from different religious backgrounds is becoming stronger. They are making regular use of each other’s contacts to promote each other’s messages for peace, and to issue joint statements. The religious leaders are continuously working on increasing the reach of their messages endorsing peace, including by expanding grassroots networks.

Business and human rights

We continue to see an increase in numbers of extractive companies and other businesses operating in more isolated regions of Colombia. Through HRDP Funds, we have built a three-year relationship with the Colombian government, companies and civil society to implement the UNGPs in the country. The process has led to the development of a draft national Public Policy on Business and Human Rights, which will be incorporated into Colombian national policy on human rights in 2014. Our project work has also resulted in a system for public servants to monitor implementation of the policy and state grievance mechanisms, which will be launched in April 2014.

Abolition of the death penalty

Morocco has a de facto moratorium on executions; abolition of the death penalty would be a landmark achievement in the region. HRDP funding, in partnership with the NGOs International Bar Association and Ensemble Contre la Peine de Mort, enabled the practical training of over 80 lawyers across Morocco, and the formation of Morocco’s first Network of Lawyers against the Death Penalty. It also supported the Moroccan Network of Parliamentarians against the Death Penalty - the first network of its kind in the North Africa region - which has raised the level of media and parliamentary debate about the death penalty. In 2013, the network prepared a draft law on abolition. A recent seminar at the Moroccan Parliament, organised by the Parliamentary Network, was well-attended by MPs from across the Arab World, from Jordan to Mauritania. With UK support, the Moroccan campaign for abolition of the death penalty is not only breaking new ground domestically, but also setting an example for the rest of the region.

Supporting peace, development and women’s rights

In the Philippines, Bangsamoro (Muslim Mindanao) is one of the most disadvantaged regions in the country. The transition period ahead of the establishment of a system of devolved government for the region in 2016 provides a window of opportunity to embed strong human rights and democratic values in the new government. Over the last year, HRDP-funded work has focused on strengthening the party system for the ministerial form of governance in Bangsamoro, and entrenching women’s participation in its Basic Law.

The latter project involves a series of consultations with groups of women representing the Bangsamoro region. Once complete, the consolidated findings will be translated into provisions in the draft Bangsamoro Basic Law, thus enhancing women’s participation in politics and governance in the region.

Protection of journalists and their access to public information

In 2013, the HRDP funded projects in Vietnam that aimed to build a safer working climate for journalists and improve access to information: work by the “Centre for Research on Development Communications” with local authorities in central Vietnam, improving officials’ understanding of journalists’ rights and strengthening media and government cooperation; a study from the “Centre for Media in Educating Community”, revealing that the government acted on less than 10% of public complaints raised through the press, and providing follow-up media training for officials to improve the situation; and a project by The Asia Foundation, strengthening investigative journalism into the environmental impact of construction projects. Media regulation has also improved because of UK development assistance. New legislation now includes an offence of obstructing reporters, protecting for the first time more than 5,000 unregistered journalists, and official penalties for government spokespersons who provide incorrect information, or do not answer press questions.

The Department for International Development’s Work on Economic and Social Rights

The realisation of all human rights underpins sustainable development. Through its development programmes, the UK supports civil society and governments to build open economies and open societies in which citizens have freedom, dignity, choice and control over their lives. UK Aid also works to ensure that all segments of society, including the persistently poor, women, ethnic minorities and other marginalised groups, can gainfully participate in growth processes by tackling the specific barriers they face in accessing economic opportunities.

In 2013, the Department for International Development (DFID) continued to implement a range of programmes that protect and promote human rights. Some of these are highlighted throughout this report, for example on strengthening the rule of law, promoting democratic governance, and security, peace and justice. Other major achievements during 2013 included the following.

Girls and women

DFID has put girls and women at the heart of international development. The DFID Strategic Vision for Girls and Women committed us to improving access to financial services for over 18 million women, providing secure access to land for three million women, and helping ten million women to access justice through the courts, police and legal assistance by 2015. In 2012-13, DFID provided at least 8.9 million women with access to financial services, and helped two million women and girls to access security and justice services.

Health

Every year around seven million children under five die needlessly, from malnutrition, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other infectious diseases. Complications during pregnancy and childbirth kill 1,000 girls and women every day. DFID’s work focuses on reaching the poorest with health services, by funding the provision of good-quality, cost-effective, basic health services by public, private and NGO providers. In 2012–13, DFID helped 3.4 million additional women to use modern methods of family planning, ensured that 500,000 births took place safely, distributed 9.8 million insecticide treated bed nets, and fully immunised 48 million children against polio.

Education

Education enables people to live healthier and more productive lives, allowing them to fulfil their own potential, as well as to strengthen and contribute to open, inclusive and economically vibrant societies. Yet more than 57 million children are still out of school, of which 31 million are girls, and at least 250 million children cannot read or count, even if they have spent four years in school. DFID’s focus is for children not only to be in school, but also to be learning. In 2012-13, DFID supported 1.5 million children in primary and lower secondary school, of which 700,000 were girls, and 1.7 million teachers were trained through multilateral programmes supported by the UK.

Water and sanitation

Across the world, 2.5 billion people do not have access to sanitation and 780 million people do not have access to clean water. Inadequate access to water and sanitation is the principal cause of diarrhoeal disease, which kills 4,000 children every day, and is the leading killer of children under five in Africa. During 2012, the UK recognised the right to sanitation as an element of the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living, as provided for under Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. This is the same basis under which the UK recognised the right to water in 2006. In 2012-13, DFID provided 3.1 million people with sustainable access to clean drinking water, and 3.8 million people with sustainable access to improved sanitation.

Economic empowerment

Around 900 million people are in “working poverty”, defined as living under US$2 a day, predominantly in Africa and Asia, and 79% of jobs held by women are vulnerable, compared to 63% for men, in Africa. Economic development is key to enhancing economic opportunities and eradicating poverty. Growth is the main driver of long-term poverty reduction through the creation of jobs and higher incomes. More inclusive growth, particularly for girls and women, also requires action to tackle the structural barriers that deny poor people the chance to raise their incomes and find jobs. This includes improving access to finance, land and property markets, and employment opportunities. In 2012–13, DFID improved access to financial services for 19.5 million people, including at least 8.9 million women, helping enable them to work their way out of poverty.

Section III: Democracy

Democracy is fundamental to human rights, the rule of law and good governance. A democratic political system represents the will and interests of the people, sustained by and propagating the principles of transparency, participation, inclusion, and accountability.

The UK works to support democracy in individual countries, taking account of the individual characteristics of each, its history and its culture. Even in countries with significant challenges around the rule of law, it is possible to work to promote democratic values in a way that supports human rights and promotes development.

Democracy rests on foundations that have to be built over time: strong institutions, responsible and accountable government, a free press, the rule of law, and citizens who have a say in how they are governed. We do not seek to promote one particular model of democracy, but we recognise that these elements are valuable in themselves and critical building blocks of development. The way we act to support democracy in each country will differ, depending on the context and needs of the country concerned. Our approach is practical, and recognises where we can have most impact. In 2013, the Human Rights and Democracy Department funded democracy projects in Cambodia, Nepal and the Philippines.

In Cambodia, voter education is a key part of the multimedia civic education initiative known as “Loy9” which aims to increase youth access to information about civic life and opportunities for participation. The project, with BBC Media, included TV and radio public service announcements (PSAs) at peak times in the build-up to the National Assembly election in July 2013. The PSAs reached over 2.5 million young Cambodians, who received clear, relevant, practical information about the election procedures, and an explanation of the role of the Members of the National Assembly for whom they were about to vote.

The UK government also gave funding to the Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL), which worked to strengthen public confidence before and after the Cambodian National Assembly election on 28 July. Election observers were deployed to polling and counting stations countrywide to monitor whether registered voters were able to exercise their right to vote, and whether election officials performed their duties effectively, including accurate publication of the results. After the election, COMFREL continued to lobby the Cambodian government to implement third-party recommendations on election reform, particularly the 2008 EU Election Observation Mission recommendations.

In November, the FCO funded a visit to Nepal by four MPs to observe the Constituent Assembly elections. The long-awaited elections followed a period of political stalemate, when the first Constituent Assembly was dissolved after failing to agree a constitution. Alongside our diplomatic efforts and significant funding from the Department for International Development (DFID) to provide technical support, the MPs’ visit demonstrated the UK’s commitment to a democratic election process in Nepal. The elections were seen by all international and domestic observers as credible, free, fair and largely peaceful.

In the Philippines, we continued to share British expertise in conflict resolution and political devolution. This diplomacy was underpinned by small UK government-funded projects on the ground. Over the last year, these projects focused on political party building, women’s participation, and drawing on the UK experience of the Patten Commission. The chief negotiators on the Philippines government side and the Malaysian facilitator were valuable contributors at our Wilton Park conference on Conflict Resolution in South East Asia in November.

Looking ahead to 2014, we will continue our work with the EU, UN, the Commonwealth, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), embassies and diplomatic colleagues. Together with DFID, we will continue to fund projects aimed at strengthening democratic processes in key countries of concern using the Human Rights and Democracy Programme Fund, Arab Partnership Fund, and Confliction Prevention Pool. We will monitor the impact of such programmes closely.

Elections and Election Observation Missions

The FCO supports election observation missions (EOMs) since they build voter confidence, deter violence, and support the credibility of the electoral process. There is also a clear correlation between peaceful transition of power through elections and longer-term prospects for development. The FCO, along with DFID, provides financial and technical assistance to international organisations that carry out EOMs, particularly the EU, OSCE, and the Commonwealth.

Election observation helps to increase the legitimacy of elections, reducing the risk of fraud and violence in the transfer of power. EU EOMs took place in Jordan, Pakistan, Paraguay and Kenya. The EU selected 39 UK observers for EOMs. In 2013, the FCO provided UK observers for OSCE EOMs to Armenia, Azerbaijan, Albania, Georgia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Mongolia and Tajikistan. The OSCE also played a crucial role in supporting Serbian presidential elections in Kosovo. The Commonwealth sent missions to observe elections in Cameroon, Grenada, Kenya, the Maldives, Pakistan, Rwanda, Sri Lanka and Swaziland.

In 2013, Pakistan reached a crucial milestone. For the first time, power transferred democratically between one civilian government and another, after a full term. This is a vital step on the path to a strong, stable and democratic Pakistan. Some 50 million people went to the ballot box on 11 May to make a statement about the future they want for their country, based on accountable, democratic government. They clearly rejected terrorist violence and intimidation.

Following an invitation from the Pakistan authorities, the British High Commission established a UK EOM. Consisting of eight teams of observers, it was one of the largest international observation teams and deployed throughout Pakistan. Our teams observed elections in Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Lahore, Murree, Faislabad, Jhang, and Karachi.

Our work on democracy in Pakistan will remain one of our key aims in 2014. The people of Pakistan can be certain of the UK’s support for their democratic future. The UK has been a long-term friend of Pakistan, and these elections have strengthened our commitment to work together, based on mutual trust, mutual respect and mutual benefit. These values have underpinned our relationship in the past, and we will do our utmost to ensure they continue to do so for the future.

The UK EOM was in addition to both the UK’s support for the EU EOM and our part-funding of the Commonwealth’s election observers. Complementing the EU, the UK EOM observed the electoral process, including the work of the election administration, campaigning activities, the conduct of the media, the process of voting and counting, and the announcement of the results.

These elections were among the most credible in Pakistan’s history, with a strong electoral register and the highest ever number of women and new voters. To protect that credibility, we hope that all allegations of malpractice will be thoroughly investigated.

Following the impeachment of President Lugo in June 2012, Paraguay held presidential elections on 21 April 2013. The poll was the most observed in the country’s history, with more than 300 international and 1,200 national monitors. The EU mission, with 111 accredited observers, had the biggest presence. After the elections, observer missions noted that the elections passed off peacefully, and were judged to have been largely free and fair.

National elections were held in Cambodia on 28 July. The EU welcomed their peaceful conduct and high public participation. The opposition made significant gains, but observers noted a number of significant irregularities in the electoral process. These included names missing from voter lists, duplicate names and manipulation of the count. More broadly, observers highlighted flaws in the campaign environment; notably unequal media access and the misuse of state resources. The opposition rejected the election result and a political standoff resulted which is still ongoing. The UK, along with other international partners, continues to push for dialogue between the two sides, with the aim of securing agreement on long-term political and electoral reforms, which will strengthen the democratic process in Cambodia.

Kenya held elections on 4 March. The determination of the Kenyan people to express their political will was demonstrated by the impressive turnout and the way in which many Kenyans waited patiently for hours to vote. The elections were largely peaceful, in stark contrast to the violence of 2007-08. The courts resolved disputes swiftly and fairly. This is an important part of the checks and balances put in place by the new Kenyan Constitution, namely to ensure that disputes are taken to the courts.

Most UK aid (around £16 million) in Kenya was delivered through the UN Development Programme’s elections basket fund. The support contributed to production of a more accurate voter register using secure optical mark technology, and put in place an independent parallel vote-counting system. This helped ensure that over 14 million Kenyans were registered to vote, and had greater confidence that their vote counted.

Protests in Cairo, Egypt, 2013. Photo Credit: Mohamed Azazy (https://flic.kr/p/fvPgxm)

The Westminster Foundation for Democracy

The Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD) is the UK’s leading democracy-building foundation. Established in 1992, WFD is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the FCO. It works globally to support the institutions of democracy – principally parliaments, political parties and civil society in post-conflict countries and emerging democracies. It is uniquely placed to draw on the expertise of all the UK’s principal political parties which work with their overseas counterparts (“sister parties”), in order to develop the skills of politicians and political parties. The overall goal of WFD is to strengthen the institutions of democracy and good governance, including respect for human rights.

During 2013, WFD continued its work on supporting parliaments, multi-party systems and civil society in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Central to WFD’s work is the development of more democratic, representative and inclusive governance systems, and strengthening of human rights. Responding to citizen-led demands for more democratic governance and rights in MENA, WFD has significantly expanded its programmes in the region. These include a MENA-wide initiative to support the engagement of women in political life, and develop the leadership skills of women politicians, enabling them to pursue reforms and legislation that protect women’s rights. Prevalent among these reform efforts are those to introduce legislation outlawing domestic violence against women.

This programme complements a range of other interventions in the region to secure greater inclusivity by forging closer links between legislators and their constituents and supporting civil society groups in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Tunisia and Yemen. Common to these civil society initiatives is the pursuit of greater accountability on the part of governments to uphold the rights of all citizens. WFD has been advising the Moroccan parliament on the creation of a public accounts committee, which was established in late 2013 in the parliament’s rules of procedure. The committee is the first of its kind in an Arab parliament.

WFD undertakes similar work in Central Asia, where it established a programme in Kyrgyzstan after uprisings and the eruption of ethnic tensions which resulted in hundreds of deaths. Designed to support greater inclusivity and better representation of citizens, the Kyrgyzstan programme supports stronger engagement between civil society, local councils, and parliament. Two pilot initiatives have been established in Naryn, central Kyrgyzstan, and in Osh, the country’s second city and centre of ethnic violence in 2010. Through the programme, the Jogorku Kenesh Committee on Human Rights, Constitutional Law and State Structure (the Kyrgyz Parliamentary Human Rights Committee) initiated the first hearings on torture and migration in Osh.

Support for more representative governance and closer links between legislators and their constituents also forms the core of WFD’s programme in Kenya. The 2010 constitutional provisions for devolving powers to Kenya’s 47 counties followed a highly divisive period of unrest and post-election violence in 2008. WFD supports the new county assemblies to perform their oversight roles in pursuit of a more equitable distribution of resources, and a transition from a centralised unitary government to a devolved one.

Strengthening democracy, human rights, and the rule of law is also the goal of WFD’s programme in Georgia, where it supports a range of civil society organisations to advocate and engage effectively with legislators on a range of policy issues, addressing the needs of all sectors of society, including poor and marginalised groups. The Georgian programme has assisted civil society organisations to lobby for reform on internal displacement, protection for defendants’ rights within the criminal code, women’s access to paternity testing, and health care for prison inmates.

In 2013, WFD completed a five-year programme, the Westminster Consortium for Parliaments and Democracy, which worked with six parliaments in Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East, resulting in a range of self-sustaining initiatives to strengthen democratic procedures. These included the establishment of parliamentary study centres in Lebanon, Uganda and Mozambique, greater representation and inclusivity of civil society, more rigorous parliamentary reporting by the media, the establishment of freedom of information legislation, and a dedicated human rights committee in the Ugandan parliament. The programme significantly contributed to WFD’s reputation as a result- and learning-oriented organisation delivering quality programmes that can strengthen democracy, good governance and citizen engagement – a legacy on which WFD intends to build in 2014.

More information on the Westminster Foundation for Democracy and its programmes is available on their website: www.wfd.org

Freedom of Expression

Freedom of expression on the internet remained one of the FCO’s key human rights priorities in 2013. As the UK stated in an address at the November Council of Europe Ministerial Conference on Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age, freedom of expression and the media are essential qualities of any functioning democracy. People must be allowed to discuss and debate issues freely, to challenge their governments, and to make informed decisions. The vital role of the media in providing people with reliable and accurate information must also be protected.

2013 saw the threats to freedom of expression being increasingly extended beyond print media to the internet, with increases in blocking and censoring, which either directly restricted freedom of expression or created a broader chilling effect. There was an increase in the number of online journalists, bloggers and others who were obstructed in their work by being harassed, monitored, detained or subjected to violence and threats. Too often, countries referred to the need for “professionalism” and “responsibility” as pre-conditions for the enjoyment of the universal right to freedom of expression. The UK strongly believes that human rights apply online as they do offline, including freedom of expression, and that in the digital age the definition of “journalist” has expanded beyond traditional print media to include other media actors, including bloggers, netizens and citizen journalists.

In an address at the Seoul Cyber Conference in November, the Foreign Secretary argued that a free and open internet, one that allows for and enables freedom of expression, and benefits from collective oversight between governments, international organisations, industry and civil society, is the only way to ensure that the benefits of the digital age are expanded to all countries. State control of the internet often comes from a desire to control expression and curtail political freedom, and not only impedes the free flow of ideas, but also holds back economic growth and development.

To mark World Press Freedom Day this year, the FCO hosted the “Shine a Light” campaign, an online digital campaign to highlight the safety of journalists through the personal testimonies of journalists and bloggers from around the world who have faced harassment and other restrictions to press freedom. The stories, videos and pictures were collated on a bespoke World Press Freedom Day blog, and included material from Sudan, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Burma, Nepal, Hong Kong (SAR), Tunisia, Lebanon, Philippines, Iran, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Jordan, Egypt, Vietnam and Bahrain. In his statement on the day, the Foreign Secretary highlighted the “debt of gratitude” we owe to the courageous journalists, including citizen journalists, who risk imprisonment, injury and death to report from repressive countries or conflict zones around the world. In parallel, our embassies around the world hosted their own events, including two debates on press freedom co-hosted with the Universidade de Brasilia and Federal University of São Paulo in Brazil, as well as a reception for journalists and bloggers hosted by the British High Commission in Singapore.

Freedom of expression remained a key priority of the Human Rights and Democracy Programme Fund in 2013. The FCO funded 11 projects around the world, totalling over £800,000. These included a project in Kazakhstan aimed at strengthening the expertise of media NGOs, journalists and media lawyers to defend the rights of journalists more effectively; one in Vietnam aimed at increasing access to information and broadening public policy debate through strengthened investigative environmental journalism; one in Russia to build journalists’ capacity to report on ethnic, race and religious diversity; and one with BBC Media Action in Zambia focused on improving the capacity of the media in Zambia to facilitate dialogue and debate between ordinary Zambians and their leaders.

The UK continued to work to promote freedom of expression online through multilateral institutions including the OSCE, the Council of Europe and the UN. The UK co-sponsored two resolutions on the Safety of Journalists at the UN Human Rights Council (UNHCR) in September and at the UN General Assembly in November. In July, during a Security Council debate on the Safety of Journalists, the UK deplored the murder of journalists as an attack on democracy and free speech, and reaffirmed its commitment to the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, encouraging all member states to work together with the UN to implement its provisions. The UK also successfully lobbied to secure language reaffirming the principle that the same rights and responsibilities that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular, freedom of expression, in the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) Communiqué in November.