High stakes: gambling reform for the digital age

Published 27 April 2023

Command Paper: CP 835

ISBN: 978-1-5286-3581-3

Unique Ref: E02769112

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport by Command of His Majesty on 27 April 2023

Ministerial foreword

The gambling landscape has changed significantly since 2005. Few who were designing policy in the early 2000s could have foreseen the nature and extent of the changes which have since reshaped our society, the economy and this sector. Multinational tech businesses now provide gambling services which customers can engage with from almost anywhere and at any time of day or night. Newly available data and technology can both increase risks to players and facilitate innovative protections. Land-based gambling also finds itself in a very different place in light of these changes, with some of the assumptions which prevailed 18 years ago looking increasingly outdated. Likewise, our understanding of gambling-related harms and gambling disorder has developed enormously over recent years.

We launched this Review to take an objective, comprehensive look at the evidence. Our aim is to ensure our gambling regulation meets the challenges and seizes the opportunities which have come with the changes since the Gambling Act 2005 was passed. We received around 16,000 submissions to our Call for Evidence, and ministers and officials have held hundreds of meetings with a huge range of stakeholders to inform a package of policies which will make our gambling laws fit for the digital age. We are enormously grateful to all of those who have contributed to our Review, especially those with personal experience of gambling-related addiction and harms who have spoken out about their own struggles or those of people they love.

At the heart of our Review is making sure that we have the balance right between consumer freedoms and choice on the one hand, and protection from harm on the other. It has become clear that we must do more to protect those at risk of addiction and associated unaffordable losses. We must also pay particular attention to making sure children are protected, including as they become young adults and for the first time are able to gamble on a wide range of products. Prevention of harm will always be better than a cure, so we are determined to strengthen consumer protections and prevent exploitative practices.

This can and should be done in a proportionate way. Millions of us enjoy gambling every year and most suffer no ill effects, so state intervention must be targeted to prevent addictive and harmful gambling. Adults who choose to spend their money on gambling are free to do so, and we should not inhibit the development of a sustainable and properly regulated industry which pays taxes and provides employment to service that demand. What we will not permit is for operators to place commercial objectives ahead of customer wellbeing so that vulnerable people are exploited.

This white paper outlines a comprehensive package of new measures to achieve these objectives across all facets of gambling regulation, building on our work over recent years. Working with the Gambling Commission and others, we will now make online gambling safer with an overhaul of game design rules to remove the features known to exacerbate risks, and put new obligations on operators to prevent unchecked and unaffordable spending. We will tackle aggressive advertising practices like using bonuses in ways which exacerbate harms. We will also develop independent messaging that raises awareness of the risks of gambling harm while helping to remove the fear of stigma that stops people coming forward for help. We will work with the industry to create an ombudsman to adjudicate complaints and order redress when things go wrong. We will modernise the rules for land-based gambling and make sure that all gambling, be it online or offline, is overseen by a beefed up, better funded and more proactive Gambling Commission which can make full use of technology and data to keep abreast of the industry.

Great Britain has been seen as a world leader in the oversight of gambling, with our comparatively low problem gambling rate but internationally successful gambling sector. I hope this new package and the policies which we will work with the Gambling Commission and others to implement will continue to be seen as world leading.

To help ensure that, I encourage all of those with an interest in gambling regulation to continue working with us as we refine the ideas, consult on specifics, and deliver real change.

The Rt Hon Lucy Frazer KC MP

Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport

Executive summary

Ensuring that gambling happens safely is a top government priority. We recognise that people should be free to spend their money as they choose, but when gambling poses the risk of becoming a clinical addiction the government needs to ensure there are proper protections. That is why change is now needed. Having a strong regulator with the powers and resources needed to oversee an increasingly high-tech industry is essential to ensuring this. We also need to have the right controls in place on the products people can be offered, safeguards covering how those who gamble are treated by operators, and the right safety nets in place to stop harm where it occurs.

Gambling in its variety of forms is a popular pastime in Great Britain, with nearly half of all adults participating in at least one form (including the National Lottery) each month. Most spend small amounts which are similar to or less than spending on other leisure activities and do not report experiencing any harm from gambling.

However, around 300,000 people in Great Britain are estimated to be experiencing ‘problem gambling’, defined as gambling to a degree which compromises, disrupts, or damages family, personal or recreational pursuits, and a further 1.8 million are identified as gambling at elevated levels of risk. Gambling harms can wreck lives, impact families and communities, and even lead to suicide in extreme cases. The package of measures outlined in this white paper will significantly increase protections with the aim of preventing harm.

Our aim in the Review has been to assess the best available evidence to ensure that our goals can be delivered in the digital age, and that we have the balance of regulation right between protecting people from the potentially life-ruining effects of gambling-related harm while respecting the freedom of adults to engage in a legitimate leisure activity. We need to ensure that our regulatory and legislative frameworks continue to deliver on the three foundational principles of the 2005 Act: children and vulnerable people should be protected, the sector should be fair and open, and gambling should be crime free.

The Review launched with a call for evidence which ran from December 2020 to March 2021 and received 16,000 submissions. Ministers and officials have supplemented this with hundreds of meetings with a wide range of stakeholders. Key publications before and since the call for evidence have also contributed significantly to our understanding of the issues, including the report of the Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry, Public Health England’s (PHE) Gambling-related harms evidence review and the independent Review of the Regulation of BetIndex Ltd. We have also received advice from the Gambling Commission, which is being published alongside this white paper. We are grateful to all those who have contributed to the Review.

Online protections

The best available evidence suggests that particular elements and products within online gambling are associated with an elevated risk of harm. Equally, technological development has presented new opportunities to protect players. Making the most of these is central to ensuring our framework is fit for the digital age.

Operators are already required to identify customers at risk of harm and take action, but there have been too many cases of interventions coming too late, or in some cases not at all. Having worked closely with the Gambling Commission, we consider it necessary to put new obligations on operators to conduct checks to understand if a customer’s gambling is likely to be unaffordable and harmful.

The Gambling Commission will consult on two forms of financial risk check. Firstly, background checks at moderate levels of spend, to check for financial vulnerability indicators such as County Court Judgments. We propose these should take place at £125 net loss within a month or £500 within a year. Second, at higher levels of spend which may indicate harmful binge gambling or sustained unaffordable losses (we propose thresholds of £1,000 net loss within 24 hours or £2,000 within 90 days), there should be a more detailed consideration of a customer’s financial position. We also propose that the triggers for enhanced checks should be halved for those aged 18 to 24 given evidence on increased risk.

These enhanced checks are narrowly targeted and we estimate only around 3% of online gambling accounts will be affected. Our intention is that these checks will also be frictionless for customers and conducted online by credit reference agencies or through other means such as open banking in the first instance. Further information will only be requested from customers as a last resort where it is necessary to complete an assessment, and the use of any data gathered through such checks will be restricted to assessing financial risk and indicators of financial distress. Operators will be required to respond appropriately to any identified risks on a case-by-case basis, taking into account all the information they know about the customer, but it is not the intent that government or the Gambling Commission should set a blanket rule on how much of their income adults should be able to spend on gambling.

Individual operators can take steps to prevent harm on their own platform but people suffering gambling harms usually hold multiple accounts or can open new ones easily. Where there are serious concerns, operators must work together. The Gambling Commission intends to consult on mandating participation in a cross-operator harm prevention system based on data sharing, following assessment of the currently live operator trials which have had input from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the Commission. We will ensure this data sharing is never used for commercial purposes.

The Gambling Commission will review and consult on updating design rules for online products, building on its recent work on online slots to consider features like speed of play, illusion of player control and other intensifying features which can exacerbate risk. Products which are safer by design will help prevent harm at source.

Online slots have been shown to be a particularly high risk product, associated with large losses, long sessions, and binge play, but unlike land-based gaming machines they have no statutory stake limits. We propose to introduce a stake limit for online slots, consulting on a limit of between £2 and £15 per spin, to structurally limit the risks of harmful play. We will also consult on slot-specific measures to give greater protections for 18 to 24-year-olds who the evidence suggests may be a particularly vulnerable cohort. This will include options of a £2 stake limit per spin; a £4 stake limit per spin; or an approach based on individual risk.

As with other sectors, we want consumers to be empowered to make informed decisions and manage spending. We will take the insights from behavioural science to make player-centric tools better. For instance, the Commission will consult on implementing potential improvements to player-set deposit limits such as making them mandatory or opt-out rather than opt-in, and we will continue work with the gambling and financial services sectors to make customer-controlled gambling transaction blocks as robust as possible.

Certain types of competitions and prize draws which offer significant prizes such as a luxury home or car now operate online in ways which could not have been foreseen in 2005. We will explore the potential for regulating competitions of this type to introduce appropriate controls around player protection and, where applicable, returns to good causes.

Advertising, sponsorship and branding

Gambling advertising and marketing has expanded into new channels and grown significantly since the 2005 Act came into force. It is clear that gambling advertising can have a disproportionate impact on particular groups such as people who are already experiencing problems, and that some aggressive advertising practices can exacerbate harms.

In a sector with a known addiction risk, the online data-driven targeting of certain individuals with promotional offers to encourage further spending presents risks because it actively encourages individuals to incur larger and larger losses. We have seen evidence showing that customers who have claimed online bonus offers are more likely to engage in high-risk gambling behaviour, especially those already at a higher risk of harm who are also likely to be targeted with more offers. The Gambling Commission has recently strengthened restrictions on online VIP schemes to make sure they are not used to exploit gamblers, and has introduced rules to stop bonus offers and other marketing being targeted at people showing significant indicators of harm. It will now take forward work to review the design and targeting of incentives such as free bets and bonuses to ensure there are clear rules and fair limits on re-wagering requirements and time limits so they do not encourage excessive or harmful gambling. The Commission will consult on proposed new controls.

We want customers to have greater control over the types of marketing they receive, such as opting-in for online bonuses and offers for different types of gambling products. The Commission will consult on introducing such controls.

Our evidence also suggests that operators should go further in their use of technology to target online adverts away from children and vulnerable people, using the functionality available to automatically exclude people who are showing signs of being harmed or whose online profile is not clearly discernible as being someone over 18. We welcome that some major online platforms have introduced the facility for customers to opt-out of all gambling adverts, and strongly encourage others to do so. The Online Advertising Programme will explore further mechanisms to reduce harm from advertising across all sectors.

We will strengthen informational messaging including on risks associated with gambling, from information at the point of purchase to messages within advertising, and identifying what messaging works for different contexts and audiences. Replacing industry ownership, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and the Department of Health and Social Care will work together with the Gambling Commission, drawing on public health and social marketing expertise, to establish the most effective messaging and how it should be used.

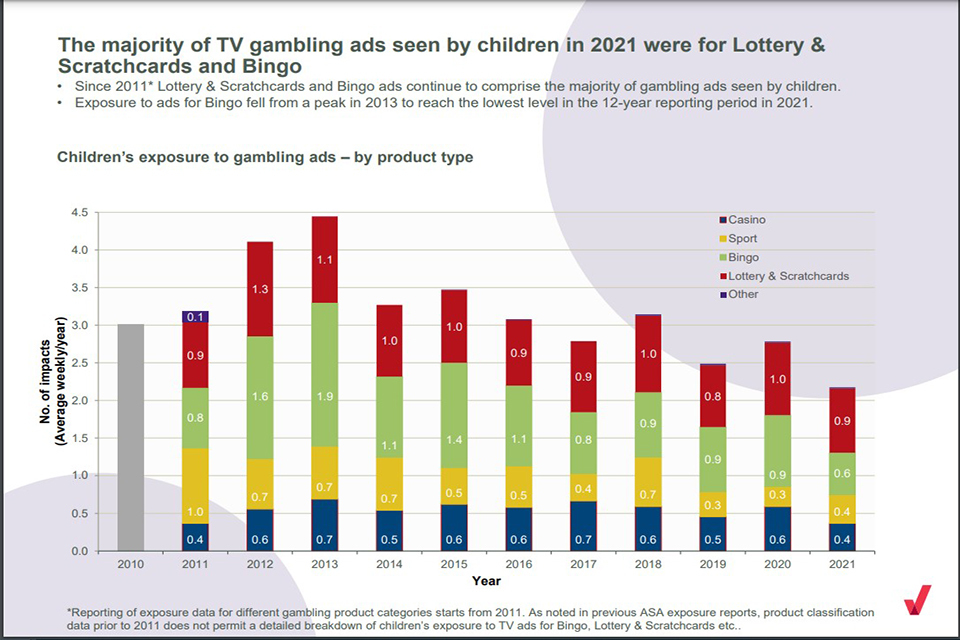

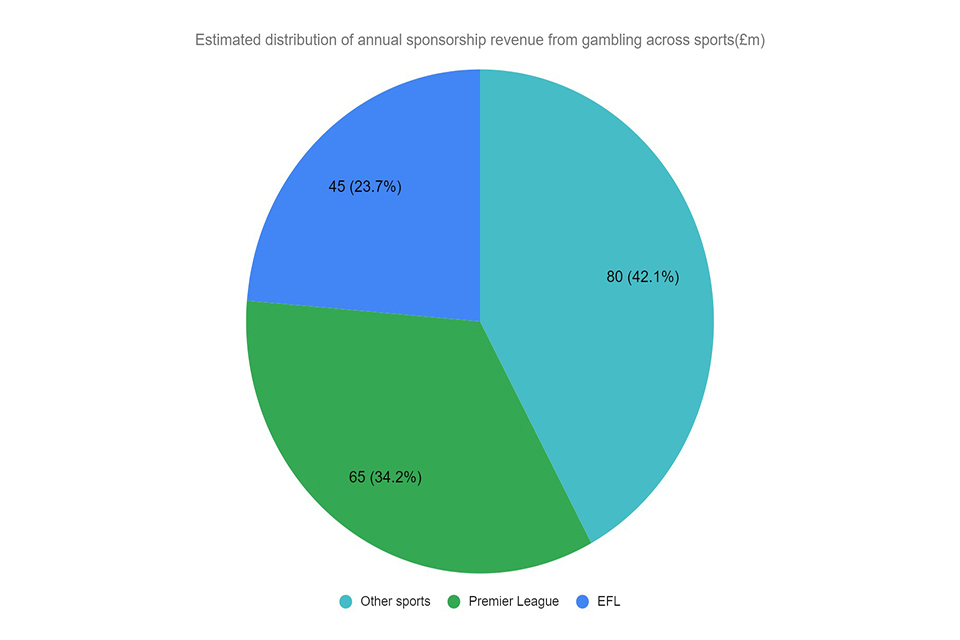

Advertising rules have changed to prohibit prominent sportspeople, in particular Premier League footballers, from appearing in gambling adverts, on the grounds of their strong appeal to children. In line with this, the Premier League has announced that it will remove gambling logos from the front of players’ shirts from the 2026/27 season. This should reduce children’s incidental exposure to gambling logos while watching football and particularly via products such as stickers and video games, as well as the direct association with star players.

We also welcome the commitment from governing bodies across the sport sector to develop a cross-sport gambling sponsorship code, with rules to make sure all sponsorship deals are socially responsible. We will work with sports bodies to refine the code over the coming months.

The Gambling Commission’s powers and resources

The Gambling Commission was created by the 2005 Act as the primary regulator for the gambling sector. We must ensure it has the powers and resources it needs to deliver its statutory remit, with the flexibility to meet future challenges.

The Commission regulates a complex and challenging sector that is constantly evolving. We will review the Gambling Commission’s fees during 2024 to ensure it has the resources to continue improving how it delivers its core responsibilities and the commitments across this white paper. We also note that the Commission has less flexibility than other regulators to adjust its own fees in light of inflation or emerging challenges. When Parliamentary time allows, we will replace the requirement to set every fee in secondary legislation with more suitable controls.

The Commission will become a more proactive regulator and it will now start building the capacity to require and analyse more data from online operators to identify non-compliance with licence conditions. Where breaches are spotted, the Commission will have increased resources to use its enforcement powers to full effect. It is also intended that more regulatory data, suitably anonymised, will be made available in due course to support independent research.

The threat of an online gambling black market does not mean we should avoid tightening controls on licensed operators. However, the threat does exist and could undermine the licensing objectives. Therefore, when Parliamentary time allows, we plan to give the Gambling Commission increased powers to support disruption and enforcement activity, such as to pursue court orders which require internet service and payment providers to take down or block access to illegal gambling sites.

We welcome the significant contributions industry has made to research, education and treatment (RET) since the introduction of the Gambling Act, and the substantial increase in funding the largest gambling operators have made available for treatment in recent years. However, we recognise that a sufficient quantum of funding is not the only requirement for effective RET arrangements and this alone will not achieve our objective for a system which is equitable, ensures a high degree of long-term funding certainty and guarantees independence. We think therefore that the mechanism for funding projects and services to tackle gambling harms should no longer be based upon a system of voluntary contributions. Government will introduce a statutory levy paid by operators and collected and distributed by the Gambling Commission under the direction and approval of Treasury and DCMS ministers. We will launch a consultation on the details of its design including proposals on the total amount to be raised by the levy and how it will be proportionately and fairly constructed. Our consultation will take into account the differing association of different sectors with harm and/or their differing fixed costs.

Government will also co-host workshops with UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the umbrella body for the UK research councils, Innovate UK and Research England, to stimulate interest and investment in gambling research. This aims to build capacity and start filling the key evidence gaps identified by PHE’s evidence review.

Dispute resolution and consumer redress

Approximately 2,000 customer complaints per year to alternative dispute resolution (ADR) providers and the Gambling Commission relate to social responsibility breaches, gambling harm and safer gambling. However, these are currently out of scope for ADR, and the Commission cannot require operators to repay individual customers. This means customers seeking personal redress in these areas currently have no choice but to pursue potentially costly and uncertain court action.

We want customers to have further protections quickly. We will work with industry and all stakeholders in the sector to create an ombudsman that is fully operationally independent and is credible with customers. The body will adjudicate complaints relating to social responsibility or gambling harm where an operator is not able to resolve these. The information that an ombudsman collates through complaints will assist the Gambling Commission in planning its enforcement activity and help industry to improve processes and support vulnerable consumers. We expect all operators to take steps to offer appropriate redress to customers where needed and if the ombudsman does not attract sufficient cooperation or deliver the protections as we expect, we will legislate to put its position beyond doubt.

Children and young adults

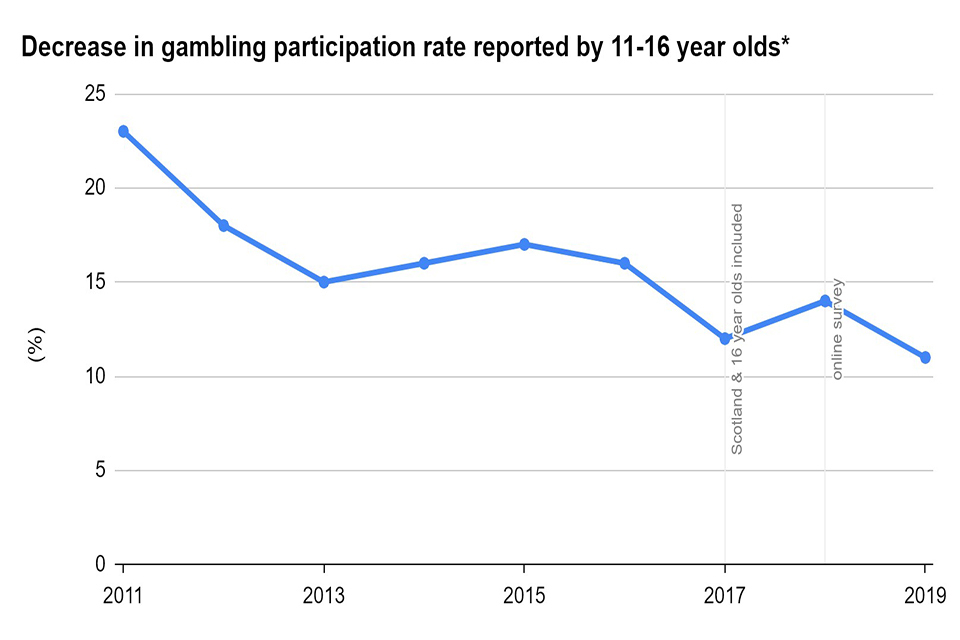

Safeguarding children from gambling-related harm is a priority. Self-reported gambling participation by 11 to 16-year-olds has fallen substantially over the last decade and most forms of gambling are already illegal for under 18s, but we will continue to strengthen protections.

Although we recently raised the age limit for the National Lottery to 18, other lottery and football pools products are still legally permitted from age 16. We welcome that most providers already voluntarily prevent play by 16 and 17-year-olds, and that participation is therefore minimal. We nonetheless challenge other providers to adopt this precautionary measure, so that there is no online or widely and easily accessible gambling for under 18s. When Parliamentary time allows, we will legislate to ensure consistency with the National Lottery and compliance across the sector.

We will also give legislative backing to the current voluntary measures preventing the use of Category D cash out slot machines by under 18s. This will create a clear distinction between gambling products for adults and lower risk products accessible to children (such as crane grabbers or coin pushers) which have non-cash prizes or are entirely unlike an adult gambling product.

There are strict and well-observed rules for age verification online and in many land-based venues. However, there are still too many instances of insufficient age verification in some venues, particularly those such as pubs, which can offer adult-only gaming machines but are not adult-only venues like many gambling premises. We challenge industry to improve age verification and will legislate when Parliamentary time allows to strengthen licensing authority powers in respect of alcohol-licensed premises by making provisions in the Gambling Commission’s code of practice binding. The Commission will also remove the exemption from test purchasing requirements for the smallest venues, ensuring all licensed venues are held to the same standards.

While most age-restricted products including gambling are permitted from age 18 in this country, there is evidence that young adults (such as those age 18 to 24) may be particularly susceptible to gambling-related harm. This is due to a combination of common life stage factors including continuing brain development impacting impulsivity control, changing support networks, and common financial circumstances such as managing money for the first time. Protections for this group will be increased, for instance through earlier interventions to assess financial risks, and structural controls such as a lower stake limit for online slots games. Operators will also be obliged to give specific consideration to age as a factor when considering potential customer vulnerabilities. The Commission will shortly release a statement on vulnerabilities to set out its expectations in line with its guidance on remote customer interaction.

Land-based gambling

The 2005 Act sets out a range of restrictions for land-based gambling based on the assumption that restrictions on supply (for example casino numbers and gaming machine availability) are an important protection. However, in the light of the availability of remote gambling, the characteristics of a product and quality of monitoring have now assumed greater importance.

The 2005 Act created new types of casino licence. Following progress by the sector to strengthen player protections, we will now take further steps to extend this regime. Where casinos whose licence originates in the Gaming Act 1968 meet the requirements of a 2005 Act Small casino, including for size and non-gambling space, they will be eligible for the same gaming machine allowance and we will align fees and mandatory premises licence conditions as appropriate. A single machine to table ratio of 5:1 will apply to Large and Small 2005 Act casinos and these larger 1968 Act casinos and they will be entitled to the same maximum 80 machine allowance. We will allow smaller casinos to benefit from more machines on a pro rata basis commensurate with their size and non-gambling space, subject to the same table to machine ratios and other conditions.

We will also permit casinos of all sizes to offer sports betting in addition to other gambling activities and will take steps to reallocate unused 2005 Act casino licences to other local authorities.

We recognise the internationally competitive market in which the small number of high-end casinos operate and the challenges the sector faces. To support their contribution to inward tourism, and as international cheques disappear as a product, we will legislate when Parliamentary time allows so that these casinos, and others which cater to the same customer group, will be able to offer credit to international visitors who have undergone stringent checks (to be set out by the Gambling Commission).

A key concern for some of the land-based sectors is the ban on direct use of debit cards on gaming machines and we recognise that substantial changes are happening to how payments in society are being made. Therefore, we will work with the Gambling Commission to develop specific consultation options for cashless payments, including the player protections that would be required before we remove the prohibition.

The Gambling Commission will undertake a review of gaming machine technical standards, to include the role of session limits across Category B and C machines.

We will adjust the 80/20 ratio which restricts the balance of Category B and C/D machines in bingo and arcade venues to 50/50, to ensure that businesses can offer customer choice and flexibility while maintaining a balanced offer of gambling products.

We will also look at the legislative options and conditions under which licensed bingo premises might be permitted to offer side bets.

We support allowing specific proposals for new machine games to be tested within planned industry pilots under certain conditions, with the close involvement of the Gambling Commission. We also support allowing trials of linked gaming machines, where prizes could accrue across a community of machines, in venues other than casinos (where they are already permitted). This is subject to further work to assess the conditions and how to limit gambling harm, and subject to Parliamentary time to legislate.

Licensing authorities have an important regulatory role alongside the Gambling Commission in licensing local premises. Empowering local leaders to take decisions in their area is a priority for this government and we support them in the use of the broad powers which the planning and gambling regulation frameworks give them to set licence conditions and consider applications. To increase their confidence in using these powers, we will align the regimes for alcohol and gambling licensing by introducing cumulative impact assessments when Parliamentary time allows and will consult on increasing the maximum fees they can charge for premises licences and permits.

Impact of reform

Measures in this white paper are designed to increase existing protections against gambling-related harm in a proportionate and targeted way. We have high confidence that the proposals address practices and products which can cause or exacerbate the risks of harm, but due to the complexity of gambling harms we cannot precisely project the reduction in gambling-related harm we expect to see at this stage. Any reduction in such harms is likely to reduce the associated societal and government costs.

It is likely that the proposals will come with costs to the gambling industry, both in terms of upfront delivery cost but also in reduced revenue compared to current levels. We currently estimate that the key proposals we can quantify will lead to between a 3% and 8% reduction in Gross Gambling Yield (GGY) across the gambling sector, with the main decrease being in online gambling (where we estimate a reduction of between 8% and 14% of GGY). Our expectation is that much of this will be foregone revenue from customers who were being harmed by their gambling, but this will be considered further through impact assessments alongside future consultations on policy. Further detail on our initial estimates of the likely or possible impacts of the package, including on sectors related to gambling such as horse racing, is at Annex A.

The government recognises the significant contribution that horse racing makes to British sporting culture and its particular importance to the British rural economy, and is keen to ensure that measures such as financial risk checks do not adversely affect the sector. We have therefore commenced the review of the horserace betting levy which we are required to undertake by 2024 and will take account of the changes set out in this document to ensure the levy delivers an appropriate level of funding for the sector.

Key white paper proposals and next steps

This white paper sets out a series of changes, and we will work with the Gambling Commission and others to implement them as soon as possible, consulting appropriately where necessary or desirable. The table below summarises the most significant proposals, how they will be delivered, and next steps. Our intention is that the main measures in the white paper will be in force by summer 2024.

| Key policy proposals summary | Proposed delivery vehicle | Next steps, noting that primary and secondary legislation is subject to Parliamentary time |

|---|---|---|

| More prescriptive rules on when online operators must check customers’ financial circumstances for signs their losses are harmful. These start with light touch checks at moderate spend levels (we propose £125 net loss within a month or £500 net loss within a year) and escalate to more detailed checks for the highest spenders (we propose £1,000 net loss within a day or £2,000 net loss within 90 days). | Gambling Commission powers | Gambling Commission consultation in summer 2023 |

| A stake limit for online slots games (which evidence suggests is the highest risk product) bringing them more in line with the land-based sector. Subject to consultation, the limit will be between £2 and £15 per spin, and we will also consult on measures to give greater protections for 18 to 24-year-olds who the evidence suggests may be a particularly vulnerable cohort. This will include options of a £2 limit per stake; a £4 limit per stake; or an approach based on individual risk. | Secondary legislation | DCMS consultation in summer 2023 |

| Making online games safer by design by reviewing game speeds and removing features which exacerbate risks. | Gambling Commission powers | Assessment of initial impact of changes to make online slots safer by design in spring 2023, followed by consultation in summer 2023 |

| Subject to trial outcomes, Commission to consult on making data sharing between online operators on high risk customers mandatory for collaborative harm prevention. | Gambling Commission powers | Initial trial results expected summer 2023 |

| Improvements to player-centric tools. For instance the Commission will consult on increasing the uptake of these tools, including whether it is appropriate to make online deposit limits mandatory or opt-out rather than opt-in. | Gambling Commission powers | Gambling Commission consultation in 2023 |

| Ensuring that incentives like bonuses and free bets are constructed in a socially responsible manner that does not exacerbate the risk of harm. | Gambling Commission powers | Gambling Commission consultation in 2023 |

| Strengthen informational messaging including on the risks associated with gambling. | Government | Government working group to commence summer 2023 |

| The Premier League has agreed to voluntarily end front-of-shirt sponsorships by gambling firms. | Voluntary commitment | Implemented from the end of the 25/26 season |

| Reviewing Gambling Commission fees to ensure it has the necessary resources to make more use of data in active enforcement and deliver commitments in this white paper. When Parliamentary time allows we will also give it new powers against the black market and replace the inflexible system of how fees are changed. | DCMS consultation on reviewing fees in 2024 | |

| Introducing a statutory levy paid by operators in scope directly to the Gambling Commission to fund research, education and treatment of gambling harms. | Secondary legislation | DCMS consultation on design and scope in summer 2023 |

| A new ombudsman to deal with disputes and provide appropriate redress where a customer suffers losses due to operators’ social responsibility failure. | Voluntary initially, with legislation if needed | Process for appointment to commence spring/ summer 2023. We expect the ombudsman to be accepting complaints within a year |

| Working with the sector and closing remaining gaps so that under 18s can do no forms of gambling either online, via fruit machines that pay cash, or on widely accessible scratchcards. Legislation when Parliamentary time allows. | Voluntary action and secondary legislation, followed by primary legislation when Parliamentary time allows. | DCMS consultation on secondary legislation on cash pay out machines summer 2023 |

| Helping the casino sector through making the rules on machines more consistent, permitting an upper limit of 80 rather than 20 to all casinos which meet rules on size, non gambling space and player protections rather than just a few. Allowing smaller casinos to benefit from more machines on a pro rata basis commensurate with their size, and also permitting sports betting in all casinos rather than just those licensed under the 2005 Act. Limited change to allow high-end casinos and others transacting with the same group of wealthy overseas visitors to offer credit, subject to protections. |

Combination of primary and secondary legislation | DCMS consultation on outstanding issues in summer 2023 |

| Working with the Gambling Commission to develop specific consultation options for cashless payments on gaming machines, including the player protections that would be required before we remove the prohibition | Secondary legislation and Gambling Commission powers | Consultation in summer 2023 |

| Relaxing the 80/20 machine rule to 50/50 so there can be an even split between low and medium maximum stake machines. | Secondary legislation | DCMS consultation in summer 2023 |

| A review of the premises licence fees cap for local authorities. When Parliamentary time allows, aligning the gambling licensing system with that for alcohol by introducing new powers to conduct cumulative impact assessments. | Combination of primary and secondary legislation | DCMS consultation in summer 2023 |

| Beginning the review of the Horserace Betting Levy to ensure the appropriate level of funding for horse racing is maintained. | Review outcomes will dictate | Stakeholder engagement, evidence gathering and analysis spring and summer 2023 |

Introduction

In December 2020, the government launched the Review of the Gambling Act 2005 with the publication of the Terms of Reference and Call for Evidence. The Review was set up to ensure our gambling laws are fit for the digital age and is the broadest examination of the regulatory framework for gambling since the 2005 Gambling Act.

The Terms of Reference said that the government’s three objectives for the Act Review were to:

- ‘examine whether changes are needed to the system of gambling regulation in Great Britain to reflect changes to the gambling landscape since 2005, particularly due to technological advances

- ensure there is an appropriate balance between consumer freedoms and choice on the one hand, and prevention of harm to vulnerable groups and wider communities on the other

- make sure customers are suitably protected whenever and wherever they are gambling, and that there is an equitable approach to the regulation of the online and the land-based industries’

This white paper sets out the government’s vision for the future of gambling regulation with a package of measures which meet the government’s objectives and reflect the latest evidence, including from our December 2020 to March 2021 call for evidence.

The white paper is structured around the six main themes in the call for evidence, followed by annexes on the estimated overall impact of our proposals and a summary of the submissions received to the call for evidence.

- online protections - players and products

- marketing and advertising

- the Gambling Commission’s powers and resources

- dispute resolution and consumer redress

- children and young adults

- land-based gambling

Developments since the 2005 Act came into force

1The Gambling Act 2005 sets out how gambling is regulated in Great Britain (gambling policy is almost entirely devolved to Northern Ireland). It does not cover the UK wide National Lottery which was set up by separate legislation. The Gambling Act came fully into force in 2007 and covers all types of in-person and remote commercial gambling, including gambling online. The Act created the Gambling Commission (replacing the Gaming Board) as the sector’s principal regulator, giving it responsibility for licensing, monitoring and, where necessary, taking enforcement action against gambling operators.

The Act initially covered gambling offered in premises based in Great Britain and also remote gambling offered by GB-based operators. It was subsequently amended in 2014 to extend to operators based anywhere in the world who are offering remote gambling to customers based in Great Britain. The change created a ‘point of consumption’ regulatory regime, meaning that any gambling company transacting with British consumers has to have a licence from the Gambling Commission and comply with the licence conditions.

The Act has been described as enabling legislation as it empowered the new regulator to respond to emerging challenges by setting new licence conditions, whether for individual operators, sub-sectors or across the industry. It also gives the Secretary of State the power to update specific provisions (such as the maximum stakes and prizes for gaming machines) and to set licence conditions via secondary legislation.

The Gambling Commission has used its power to update Licence Conditions and Codes of Practice (LCCPs) to deliver a number of key reforms. These have most recently included changes to the social responsibility code such as new requirements on age and identity verification, tighter rules on VIP schemes, the ban on credit cards for nearly all types of gambling, the ban on reverse withdrawals, new rules for online slot games, and tighter requirements on remote customer interaction.

Gaming machine stake and prize limits are set out in secondary legislation and have been changed a number of times by the Secretary of State since the 2005 Act. For instance, the 2016-18 review of gaming machines and social responsibility measures led to, among other measures, a cut in the maximum stake for B2 machines in betting shops from £100 to £2 in 2019.

In addition to the licence conditions and legislation governing how facilities to gamble are offered, all gambling advertising must comply with the UK Advertising Codes which are set by the Committees of Advertising Practice and enforced by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA). These have also been updated a number of times since 2005, with guidance also tightened where needed to mitigate particular risks (e.g. banning content with strong appeal to children from October 2022).

The 2005 Act also created a partnership between the Gambling Commission and 368 licensing authorities (Local Authorities) in England, Wales and Scotland for the regulation of land-based gambling. While the Commission licences operators and individuals, local authorities (and licensing boards in Scotland) licence premises and have the power to place conditions on licences as well as to grant or refuse them.

Gambling participation and prevalence of harm

Each nation in Great Britain conducts its own annual Health Survey to gather authoritative data on physical and mental health, and these periodically include gambling questions. The most recent year for which we have combined Health Survey data is 2016, in NatCen’s report Gambling Behaviour in Great Britain in 2016.

In addition, the Gambling Commission collects regular data on the extent and impact of gambling in Great Britain. As well as commissioning analyses of Health Survey data and a wider programme of research, the Commission conducts a quarterly telephone survey on participation and prevalence to track trends, but this is less robust than the full Health Surveys.

The coverage of these surveys is not perfect and there are gaps in the evidence and our understanding. However, Public Health England (PHE) compiled, assessed and reviewed evidence on gambling participation and harm as part of the Gambling-related harms evidence review which was initially published in September 2021, then revised in January 2023 by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities.

Overall, gambling is a popular activity in Great Britain. Excluding National Lottery only play, participation trends are broadly flat with some signs of a decline since 2010. Figure 1 presents the best available data on long-term trends in gambling participation.

Figure 1: Past year gambling participation (% of adults in Great Britain)

| Year | All gambling (except National Lottery) | Any gambling (including National Lottery) |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 46% | 72% |

| 2007 | 48% | 68% |

| 2010 | 56% | 73% |

| 2012 | 43% | 65% |

| 2015 | 45% | 63% |

| 2016 | 42% | 57% |

| 2018 | 40% | 54% |

Survey methodology varies over time - see labels below. HSE (2018) is for England only.

1999, 2007, 2010: British Gambling Survey

2012, 2015, 2016: Combined Health Survey

2018: Health Survey England

Sources: NatCen, British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010; Gambling Behaviour in Great Britain in 2016: NHS Digital, Health Survey for England 2018 – Supplementary Analysis for Gambling, 2019

The more recent data from the Gambling Commission’s quarterly telephone surveys suggests that in the year to December 2022, 44% of surveyed adults had taken part in at least one gambling activity in the previous four weeks (29% excluding those who only played the National Lottery).

The National Lottery has had a broad customer base since its launch in 1994 and remains the most popular gambling product (see Figure 2 below). It is regulated under a separate framework from commercial gambling, the National Lottery etc. Act 1993, and is not subject to this Review. Since its launch in 1994, the National Lottery has raised over £47 billion for good causes and its games are associated with among the lowest levels of problem gambling prevalence of any product.

Figure 2: Past four week adult gambling participation by product in year to December 2022

| Activity | % respondents participating in gambling |

|---|---|

| National lottery draws | 28.7% |

| Scratchcards | 7.7% |

| Another lottery | 13.4% |

| Football pools | 1.4% |

| Bingo | 2.3% |

| Fruit or slot machines | 3.2% |

| Online slot machine style games/instant wins | 5.0% |

| Casino games | 1.4% |

| Horse races | 3.8% |

| Sports betting | 4.9% |

| Private betting | 3.5% |

| Any other activity | 0.7% |

Source: Gambling Commission statistics on participation and problem gambling for the year to December 2022

When all forms of gambling are considered together, participation is higher among men (57.4% of men surveyed in England between 2012 and 2018 had gambled in the previous 12 months) than women (50.7%). Overall, the PHE evidence review found that the highest rates of gambling participation are reported among people who have higher academic qualifications, are employed, are relatively less deprived, and who reported better general psychological health and high life satisfaction. However, as outlined below, more deprived communities have higher rates of people experiencing problem gambling.

Gambling-related harms

The very nature of gambling involves risk and potential losses. It is clear that gambling-related harms can ruin lives, wreck families, and damage communities, with issues including mental health and relationship problems, debts that cannot be repaid, crime, or even suicide in extreme cases.

Gambling harm is often a result of the interplay between individual susceptibility, environmental factors, the products themselves and operator actions. However, as the PHE evidence review found, gambling and the associated harms are less well understood and researched than some other addictions such as alcohol misuse, and much of the available evidence is limited or varying in quality.

Firstly, the best available evidence suggests that the large majority of people who gamble suffer no ill effects. Most gamblers report having never experienced any of the 9 indicators of harm in the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) screen as measured in the questions below:

-

have you bet more than you could really afford to lose?

-

have you needed to gamble with larger amounts of money to get the same feeling of excitement?

-

when you gambled, did you go back another day to try to win back the money you lost?

-

have you borrowed money or sold anything to get money to gamble?

-

have you felt that you might have a problem with gambling?

-

has gambling caused you any health problems, including stress or anxiety?

-

have people criticised your betting or told you that you had a gambling problem, regardless of whether or not you thought it was true?

-

has your gambling caused any financial problems for you or your household?

-

have you felt guilty about the way you gamble or what happens when you gamble?

However, a small proportion do suffer significant harm as a result of gambling, and the PHE evidence review included a detailed quantitative analysis on this issue. Figure 3 shows the best available data on population problem gambling rates, which have remained broadly steady around or below 1% for over 20 years. Based on Health Survey data, we now estimate there to be approximately 300,000 people across Great Britain who meet the definition of being a ‘problem gambler’.

Figure 3: Population problem gambling rates (survey methodologies vary over time)

| Year | % of the adult population |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 0.6 |

| 2007 | 0.8 |

| 2010 | 1.2 |

| 2012 | 0.6 |

| 2015 | 0.8 |

| 2016 | 0.7 |

| 2018 | 0.5 |

1999, 2007, 2010: British Gambling Prevalence Survey, DSM-IV screen only

2012, 2015, 2016: Combined Health Survey, DSM-IV + PGSI

2018: Health Survey England only, DSM-IV + PGSI

Sources: NatCen, British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010; Gambling Behaviour in Great Britain in 2016, NHS Digital, Health Survey for England 2018 – Supplementary Analysis for Gambling, 2019

There are some recent signs of a decrease in problem gambling rates, with the Gambling Commission’s quarterly surveys finding a steady fall over recent years to a low of 0.2% in the year to December 2022. However, this is based on smaller sample sizes than the data in Figure 3 and on the PGSI mini screen rather than all 9 questions above. Figures may also have been impacted by the recent fall in gambling participation or other behaviour changes linked to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, including the unavailability of some gambling activities. In a recent pilot for a new approach to collecting data on population problem gambling rates, the Commission found the sample surveyed had a higher problem gambling prevalence rate of 1.3%, although this is an experimental rather than official statistic and the methodology is still being refined.

There is significant detail underneath this population problem gambling rate which the PHE review considered. In particular, it found men were more likely to be experiencing problem gambling than women and that 16 to 24-year-olds had the highest average PGSI score of any age group. There are also significant variations in the rates of problem gambling associated with each product, but consistent evidence that gambling online and the use of multiple gambling products are associated with higher PGSI scores.

The proportion of people suffering harm might also be identified through other sources such as bank transaction analysis, hospital admission data, and operators’ own harm detection algorithms which flag the customers displaying indicators of harmful gambling. However, there are limitations to all of these sources including incomplete coverage and lack of detailed information.

Harmful gambling is strongly correlated with and likely to exacerbate existing health disparities. There is a higher prevalence of problem gambling among people with poor health, low life satisfaction and wellbeing scores, and the problem gambling rate is higher among more deprived groups than less deprived groups. For instance, PHE’s evidence review found that the problem gambling rate is 0.3% among graduates, compared to 1.0% for people with no qualifications, and is around three times higher among unemployed people (2.1%) than employed people (0.7%).

It is also important to recognise that problems with gambling can be one of a number of harms individuals suffer simultaneously; for instance while gambling addiction can impact mental health and wellbeing, poor mental health and heavy alcohol use are commonly suffered alongside gambling harms. Due to a lack of longitudinal evidence the PHE report did not establish causal relationships with these other health harms, or in the case of mental health issues, found that relationships appeared to go in both directions.

In addition to the approximately 300,000 people categorised as ‘problem gamblers’, there are approximately 1.8 million people in Great Britain categorised as ‘at risk’. This includes approximately 1.4 million classed as low risk, who may not be suffering harm but occasionally engage in potentially harmful behaviours such as chasing losses, and around 440,000 classed as moderate risk, who may suffer some negative consequences such as having to gamble larger and larger amounts to get the thrill or feeling guilty about gambling. Alongside the harm to the individual, gambling-related harms can have negative impacts on other people and wider communities. A YouGov survey commissioned by GambleAware estimated that 6% of the population are negatively affected by someone else’s gambling (for example through relationship strain or financial hardship) and that women are overrepresented in this category.

Benefits of gambling

There are also benefits to gambling which should be weighed in decision making, although they do not negate the need to prevent gambling-related harm. For most people who participate, gambling is a leisure and entertainment activity, as explored in the Gambling Commission’s research into why people gamble and its research into customer journeys. While the risks vary by product and other factors, gambling participation is generally not in itself harmful and may even be positive. Gambling can be sociable, can help tackle loneliness and isolation, can enhance the enjoyment of other activities, and can be a valuable pastime in its own right, although quantifying these benefits is inherently difficult.

For the majority of people in the Gambling Commission’s research, gambling was just another normal activity which they reported feeling completely in control of. While motivations varied, around three quarters of respondents to the why people gamble study agreed that the opportunity to win money was a part of the enjoyment, while 66% agreed they ‘get a thrill from finding out if they’ve won or not’.

There are also economic benefits to having a well regulated industry to service this demand. The sector pays approximately £2 billion per year to the government in duties (excluding Lottery Duty), accounted for £5.7 billion or 0.3% of UK Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2019, and employed approximately 98,000 people in Great Britain in 2019. While many gambling companies do operate overseas hubs, the jobs in this country are geographically dispersed, with hubs of high skill work in areas like Stoke-on-Trent and Leeds.

The gambling sector also contributes significantly to other industries, including sport, advertising and racing. Horse racing in particular has a mutually beneficial relationship with betting, and the levy paid by bookmakers on their racing derived revenue contributes around £100 million a year to support the sport. Gambling can also contribute to tourism, for instance to seaside towns across the country, or high-end casinos attracting wealthy overseas visitors who spend across a number of other sectors while in this country. Additionally, some gambling products enable charities and other non-commercial organisations such as sports clubs to raise valuable funds. For instance, large society lotteries generated over £400 million in 2020/21 in returns to good causes.

1. Online protections - players and products

Summary

The evidence suggests that particular elements and products of online gambling are associated with an elevated risk of harm. Equally, technological development has presented new opportunities to protect players. Making the most of these is central to ensuring our framework is fit for the digital age. This chapter proposes a range of targeted interventions:

Account level protections

The Gambling Commission will consult on new obligations on operators to conduct checks to understand if a customer’s gambling is likely to be harmful in the context of their financial circumstances. This will target three key risks identified by the Gambling Commission in its casework: binge gambling, significant unaffordable losses over time and financially vulnerable customers.

In general, this government agrees with the principle that people should be free to spend their money how they see fit, so we propose a targeted system of financial risk checks that is proportionate to the risk of harm occurring. Assessments should start with unintrusive checks at moderate levels of spend (we propose £125 net loss within a month or £500 within a year), and if necessary escalate to checks which are more detailed but still frictionless at higher loss levels where the risks are greater (we propose £1,000 loss within a day or £2,000 within 90 days). We also propose that the triggers for enhanced checks should be lower for those aged 18 to 24. Once a suitably effective and secure platform is in place, the Gambling Commission will consult on making data sharing on high risk customers mandatory for all remote operators. Individual operators can take steps to prevent harm on their own platform, but people suffering gambling harms often hold multiple accounts. Where there are serious concerns, operators must work together.

While account verification is on the whole effective, there are difficulties in matching payment details to the account holder. This creates compliance risks and potential harms for those experiencing problem gambling and affected others. With new technologies and payment regulations now in place, the Commission will work with others to consider what more can be done to reduce this risk.

Safer games

The Gambling Commission will review and consult on updating design rules for online products, building on its recent work on online slots to consider features like speed of play which can exacerbate intensity and risk. Products which are safer by design will help prevent harm at source and reduce the reliance on reactive harm detection systems.

We propose to introduce a maximum stake limit for online slots games of between £2 and £15, subject to consultation. This would prevent slots play where there is an elevated risk of rapid losses and/or harm, while leaving the majority of customers who play at low stakes unaffected. We will also consult on measures to give greater protections for 18 to 24-year-olds who the evidence suggests may be a particularly vulnerable cohort. This will include options of a £2 limit per stake; a £4 limit per stake; or an approach based on individual risk.

Empowered customers

Tools like deposit limits can help people gamble within their means, but may be underused and not widely optimised for harm prevention. Informed by insights from behavioural science, the Gambling Commission will explore making these tools mandatory for players to use or opt-out rather than opt-in, as well as other changes to reduce friction and help people gamble safely before any problems arise.

While GAMSTOP is the principal means of online self-exclusion, we welcome that banks and payment providers offer opt-in gambling transaction blocks. The gambling industry should work with financial service firms to enable the blocks to be extended to other payment methods like bank transfers.

Online operators use data to identify and restrict accounts in response to suspected fraudulent activity and for commercial reasons (for example customers betting too successfully). It is important that customers are made aware of the circumstances in which such restrictions may be applied and provided with explanations where it does occur. This is consistent with the Commission’s rules for clear and accessible terms and conditions and the regulator will monitor operators’ compliance in this area.

Operators sometimes put artificial behavioural barriers in the way of consumers doing what they want. Activities such as withdrawing winnings, closing accounts and accessing important information should be made as frictionless as possible. Behavioural barriers and friction should only be used to keep customers safe rather than impede them from taking decisions.

Changing landscape

‘White label’ describes a commercial arrangement whereby a licensee offers remote gambling under a brand provided by a third party which does not itself hold a remote gambling licence. While the risks are not fundamental to such arrangements and licensees are rightly held to account, there have been examples of non-compliance associated with these arrangements. The Gambling Commission will consolidate and reinforce expectations for operators on contracting with third parties, including white labels.

Prize draws and competitions have been able to grow significantly and advertise widely in the digital age. These competitions, unlike lotteries, are not regulated. This is because they offer a free entry route (for instance via ordinary post) or have a skill-based element. We propose to explore the potential for regulating the largest competitions of this type to introduce appropriate controls around player protection and, where applicable, returns to good causes, and to improve transparency.

1.1 The current position

The online gambling landscape now is very different to the one which existed in 2005. Online gambling overtook land-based gambling by GGY – the total value of funds staked minus any winnings or prizes paid out – in September 2019 and continues to grow. In the year to December 2022, 18.6% of British adults had gambled online in the last four weeks, excluding National Lottery products, compared to 14.4% in the year to December 2018. This has largely been driven by a channel shift from land-based gambling, where participation has fallen from 24.7% to 19.5% of adults in the same period (excluding the National Lottery). While the lasting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic remain to be seen, it seems likely that the shift towards online participation, as we have seen in many other sectors, will continue.

Perhaps more significant change has occurred underneath this wider channel shift, as new technologies have also reshaped where, when and how people gamble online. In 2015, just 23% of online gamblers had used a mobile phone to gamble online in the previous 4 weeks, compared to 50% in 2020. Online gamblers can now gamble at any time and in any location they choose, and while online gambling from home remains the most popular choice, in 2020 1 in 5 had done so outside the home.

Technological change has also enabled innovation in both the betting and gaming product offer. For betting, this has predominantly entailed increased betting opportunities. Not only is there an unprecedented variety of international sports and fixtures to bet on, ‘in-play’ betting (while an event is taking place), ‘request a bet/ build a bet’ (where gamblers pick their own combination of outcomes to wager on) and peer to peer betting exchanges are now widely and frictionlessly used, having been in their infancy or non-existent in 2005. Online gaming products too have changed as the sector has matured, with rapid, stimulating and intense random number generator powered games like online slots becoming increasingly popular and making up a larger portion of operator profits over time. Further change is inevitable.

While all gambling carries a risk of harm, there are warning signs that aspects of online gambling in its current form are associated with particular risks for consumers, including the 24/7 accessibility via mobile devices; the ease of access to funds and use of digital monies; the ability to gamble without some element of direct human supervision, including when intoxicated; and the immersive nature of online activities in general. According to the 2018 Health Survey for England, excluding National Lottery draws, 4.2% of people accessing any online gambling were experiencing problem gambling, compared to 1.3% of people accessing any gambling activity. These trends have also been identified in evidence highlighted by PHE. While drawing on predominantly cross-sectional evidence from multiple jurisdictions, a meta-analysis of research around the risk factors for harmful gambling found that ‘internet gambling’ had the strongest association with problem gambling, exceeding any other product type and various demographic or socioeconomic factors. Online gambling is also increasingly flagged by individuals accessing treatment or support services: in 2021/22 around 75% of patients of the National Gambling Treatment Service across Great Britain primarily gambled online, and 84% of GamCare helpline callers mentioned online gambling against 30% for offline.

Some academics, treatment providers and groups with personal experience have also argued the environment of online gambling and certain structural characteristics of online products are inherently risky for all customers, and particularly for those who are otherwise vulnerable. For example, 40% of online gamblers who had experienced mental health problems agreed they did not feel like they were spending real money online, compared to 26% of those with no experience of mental health problems. We also received evidence from charities that people facing challenges like social isolation or cognitive dysfunction (such as following a brain injury) could be particularly attracted to remote gambling opportunities and fail to understand or properly assess the risks.

However, the online environment also provides many opportunities to make sure people are gambling safely. All online play is account-based, and recent years have seen significant strides in the development of harm detection algorithms which monitor every aspect of a customer’s gambling to spot signs of risk and trigger interventions without human input. Equally, customers can be easily empowered with a range of tools like financial limits which are inherently harder to implement offline.

Our vision for remote gambling is that the risks are mitigated, and that we maximise the use of technology and data to protect people in a targeted way at all stages of the customer journey. The proposals outlined will deliver:

- new account level protections to make sure operators are adequately protecting all online gamblers

- measures to make online products safer by design, including controls on structural characteristics like speed and stake

- steps to empower all online gambling customers to understand and control their gambling

- a new approach to specific issues which are part of the changing landscape in the ever innovating online gambling environment

Current protections

This section takes stock of the existing protections in place for online gamblers to contextualise the proposals outlined later in this chapter. Online gambling is a fully regulated sector, and the rules governing it are largely set out in licence conditions or technical standards on remote operators rather than in statute. This enables the requirements to be more detailed and to be amended more quickly over time to respond to technological change or new risks to consumers.

Protections applied by the consumer

All licensed online operators must provide customers with a range of tools to help them gamble safely, such as gambling activity statements, ‘time out’ functionality, and facilities to set limits on spend. While the use of these tools by customers is voluntary and operators are afforded a degree of discretion around how they are designed, there are requirements attached to certain tools. For example, the option to set a deposit limit must be available to all customers from when they first open an account or deposit funds, and increasing a deposit limit must take at least 24 hours to come into effect.

While most gambling management tools are provided to help customers gamble safely, all operators must also offer self-exclusion facilities to help those who wish to stop gambling altogether. In March 2020, it became mandatory for licensed operators to sign up to GAMSTOP, the multi-operator self-exclusion scheme. According to GAMSTOP’s submission to the DCMS Select Committee which was published in March 2023, 345,000 individuals have registered with the scheme since April 2018.

Other sectors and non-profit organisations can also help consumers manage their gambling. Approximately 90% of UK current accounts from retail banks now offer opt-in gambling blocks which prevent card payments to gambling companies once activated. Similar tools are increasingly available from other payment providers like PayPal. Services such as Gamban and BetBlocker also allow consumers to block access to gambling apps and websites on internet devices. When used in conjunction with self-exclusion, payment and website blocks can add a further layer of protection for people recovering from gambling harm.

Gambling participation and prevalence of harm

However, while these tools are helpful for many online gamblers, they are not enough to fully mitigate the risks, so there are also a range of obligations on operators to identify and prevent gambling-related harm. All operators must monitor player behaviour and use the wealth of data they have available to identify those who may be at risk and take action to protect them, in line with the Commission’s detailed guidance. Where needed, the actions taken must include encouraging or requiring a player to set limits, actively signposting to support services, suspending marketing in cases where there are strong indicators of harm, and unilaterally suspending or closing accounts.

While operators’ approaches to achieving this vary, the strengthened Gambling Commission rules which came into force in September 2022 and February 2023 clarify operator responsibilities around customer interaction and mandate consistency across the sector. These rules specify seven relevant categories of ‘indicators of harm’ which all operators must monitor from the moment an account is opened (Figure 4), and set out how operators must tailor the action they take based on these behavioural indicators.

Figure 4: ‘Indicators of harm’ online operators are required to monitor and example constituent indicators

Patterns of spend

- binges

- high amounts at set times (eg. payday)

- escalation of gambling

Customer spend

-

amounts spent, taking into account affordability

-

amount spent compared to other consumers

Time indicators

- amount of time spent gambling

- time of day (eg. late night)

Behaviour

- multiple products

- chasing losses

- choice of higher-risk products

- in-play betting

- erratic patterns

Customer-led contact

- complaints

- indicators of vulnerability such as bereavement

- hints of not coping

- chat room comments

Use of gambling management tools

- refusal to use tools

- changing limits

- previous self-exclusion

- repeated use of time out

Account indicators

- failed deposits

- multiple payment methods

- types of payment

Source: Gambling Commission, Remote Customer Interaction Guidance

In addition, the regulator also sets the Remote Technical Standards which outline the security and technical standards for remote gambling operations. As well as specifying how certain account level protections should function, these include specific rules for online gambling product design, aimed at making sure games operate in a socially responsible manner and do not encourage potentially harmful gambling activity. Under the Commission’s product testing strategy which was updated in February 2020, games are subject to pre-release testing for randomness and fairness and, once released, subject to annual audits by testing houses.

In February 2021, the Gambling Commission announced revised standards for online slot games to make them safer by design. These mirror many of the existing controls on gaming machines and tackle some of the features which exacerbate the risk of harm to gamblers; for example, increasing the intensity of play or encouraging a false perception of the game, such as feeling in control of the game outcome or believing a game is due a payout.

Finally, there is also a range of other universal controls to make the online gambling experience safer, largely imposed through licence conditions on gambling operators. For example, there are strong age verification measures for setting up accounts to prevent children gambling, reverse withdrawals have been banned since October 2021 (building on guidance issued in May 2020), and the use of credit cards to gamble online was banned in April 2020, which the evidence suggests has been useful in preventing harm.

Evidence

Given the Review’s focus on ensuring our gambling laws are fit for the digital age, it is unsurprising that a significant amount of evidence was submitted in response to the remote gambling questions in our call for evidence. Key evidence as it relates to our policy proposals is discussed in more detail below, but a number of overarching themes emerged across the submissions.

Firstly, there was significant discussion of the existing controls and the majority (including industry stakeholders) presented evidence that current protections could and should be further improved.

Operator responses largely put this in the context of the recent changes which have been introduced through voluntary industry codes or Gambling Commission mandated action. For instance, many discussed the significant changes to their harm detection systems since the Commission updated its customer interaction requirements and guidance in July 2019, and others mentioned measures like the ban on credit cards in April 2020. Most industry submissions pointed to recent Gambling Commission data (which has since been updated) which suggests a decline in the population problem gambling rate, as evidence that the incremental changes are having the desired effect. They therefore make the case for continued changes, but cautious ones which fully evaluate the spate of recent measures before proceeding.

Conversely, many outside the industry submitted evidence on the harms which individuals had suffered in spite of the existing controls, which they argued were therefore ineffective. In their view, significant new controls are needed to curb the risk of harm presented by certain features of online gambling including industry practices.

In particular, some of the evidence submitted by academics, treatment providers and those with lived personal of harm argued that the current data-led system of personalised monitoring and interventions to prevent harm is not (for all its theoretical promise) currently delivering on the government’s objective of keeping customers safe as it is by definition reactive. A number of individuals submitted evidence including case studies which showed that signs of harm can be missed and that individuals are permitted (and occasionally encouraged) to continue gambling.

To support this position, many respondents cited the Patterns of Play interim report. This included data on operator interactions, showing that just over 3% of online gambling accounts spent over £2,000 in a year, but only 35.5% of these were subject to any safer gambling interaction (such as an email or pop up message), and just 0.84% received a safer gambling telephone call. These individuals may not have been spending more than they could afford, but many respondents felt operators should have been doing more to check.

The account data used in this report came from 2018/19, and it does appear that operators’ use of play data has improved since then, although we note that Gambling Commission enforcement activity has continued to find more recent failings. One major operator’s evidence reported a threefold increase in the number of customer interactions compared to two years ago and increased positive impact from their interventions (according to their own evaluation). Many operators were confident that their current and increasingly sophisticated harm detection algorithms would have prevented ‘historic cases’ where harm occurred without sufficient action. Some contended the models can now even identify and prevent harm before it occurs, but this is hard to verify. Operators broadly argued in favour of these tailored controls, rather than measures which may limit the enjoyment of gambling for the majority of players who suffer no ill effects and may (if curtailed in their gambling) turn to unlicensed operators.

How gambling operators use the data available to them was also covered by campaign and consumer groups, with some levelling specific criticisms regarding data governance and processing. In addition to failing to identify those suffering harm, respondents identified wider practices which might be detrimental to consumers, such as the profiling of customers and the restriction of winning accounts. This was part of a broader sentiment across some respondents that consumers needed to be better empowered in their dealings with remote gambling products and companies.

In addition to submissions to the call for evidence, we also received advice from the Gambling Commission, which emphasised the importance of measures to prevent harm throughout the remote customer journey, and committed to build on recent work to improve protections.

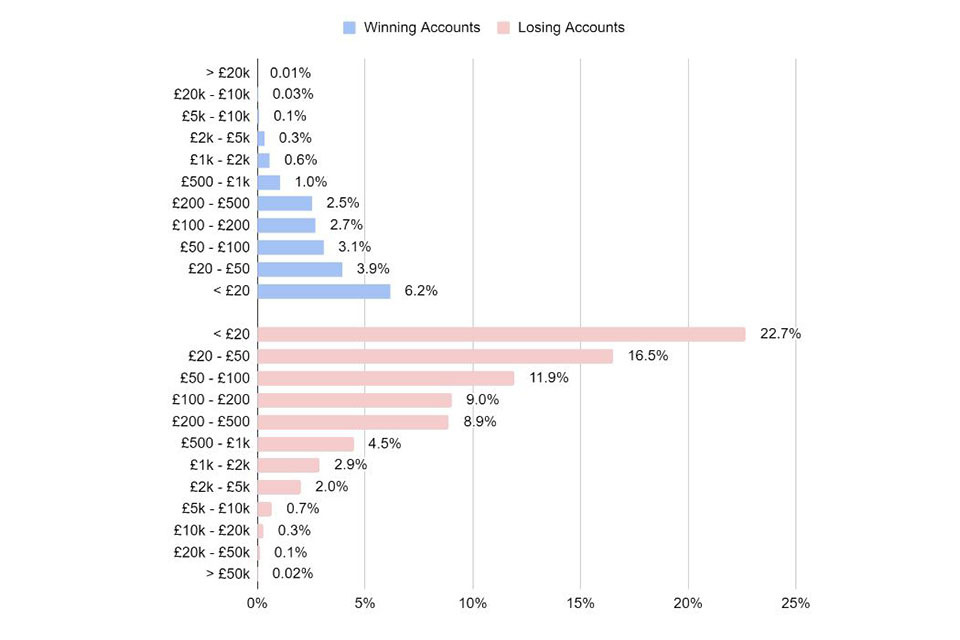

Box 1: Losses and harms across online gamblers

Most online gamblers have relatively modest losses. The Patterns of Play research commissioned by GambleAware found that between July 2018 and July 2019, 21% of accounts made a net gain, 60% lost less than £200, 13% lost between £200 and £1,000, 5% lost between £1,000 and £5,000, and around 1% lost more that £5,000 (see Figure 5 below). This suggests most customers do not spend above levels which would be usual in other leisure sectors, although personal circumstances on whether these losses are acceptable will vary.

This distribution means that operator revenue is predominantly derived from a relatively small cohort of high spending customers. The range of estimates submitted to our call for evidence suggest that (ignoring accounts which net win), around a quarter of Gross Gambling Yield is derived from 1% of accounts, approximately 60% comes from the highest spending 5%, and around 75% from the top 10%, although this varies by product. Some submissions pointed out that a reliance on a high spending minority is not unusual in other sectors (such as air travel) and that higher than average spending on gambling is not in itself evidence of harm as discretionary income varies significantly across individuals.

Nonetheless, this is a potentially concerning pattern in a sector with a known addiction risk, and where a key manifestation of that addiction is high spending. In responses to our call for evidence, estimates of the Gross Gambling Yield derived from harmful gambling varied significantly, as they have in previous evidence such as that reviewed by the knowledge exchange GREO in 2019, which found estimates range between 15% and 50%. A recent survey of UK gamblers estimated that moderate-risk and problem gamblers (collectively comprising 14.1% of the sample population) accounted for 43.5% of overall gambling spend but more for certain product types. While there are real complexities that make it difficult to pinpoint a precise figure, the weight of the evidence suggests that those being harmed by gambling are overrepresented among those with high gambling spend. Therefore, a general shift in the economic model of remote gambling away from a reliance on a high spending minority is likely desirable to achieve the government’s objectives and create a more sustainable industry.

Figure 5: Distribution of total spending (wins and losses) across accounts

Source: Natcen Patterns of Play Slide 40

1.2 Account level protections