Integrated care partnership (ICP): engagement summary

Published 23 March 2022

Applies to England

Foreword

One of the lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and the vaccine rollout was the level of local collaboration between the NHS, local authorities, and local partners in the best interests of residents. In many areas, the pandemic galvanised joint working and showed what could be achieved if the different parts of the system worked together to achieve shared objectives.

Improving outcomes and experience through the integration of services can be done where the NHS, local authorities, social care providers, voluntary and community organisations, social enterprises, and wider partners come together to deliver in the best interests of residents in their area.

The Health and Care Bill’s proposed duty on integrated care boards (ICBs) and local authorities to form integrated care partnerships (ICPs), seeks to put this best practice at the heart of the health and social care system, and make collaboration and co-operation across bodies an intrinsic part of how the health and care system delivers.

This paper sets out what we heard as part of a trilateral engagement exercise undertaken by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England (NHSE) and the Local Government Association (LGA) over recent months. This engagement included stakeholders with an interest in the formation of ICPs, and will inform how DHSC, NHS England and the Local Government Association guide and support the development of these new partnership arrangements ahead of their implementation in July 2022 and beyond.

This paper seeks to inform and shape conversations taking place across England, aiding local areas to find the arrangements that suit their populations and circumstances, rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all model from above. It forms part of an ongoing process of engaging, listening and supporting which will continue up until the establishment of integrated care partnerships and beyond.

We hope that this document will prove to be of use as designate ICB leaders; local authorities and system partners navigate this important development in the health and care landscape. We want to help develop a health and care system which is passionate about partnership and its potential to deliver better outcomes for people.

Executive summary

This document summarises the trilateral engagement undertaken by DHSC, NHSE and LGA following the publication of ICP engagement document: integrated care system (ICS) implementation in September 2021 by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England (NHSE) and the Local Government Association (LGA).

What we heard

Our engagement was based on the 5 expectations of integrated care partnerships (ICPs), we have summarised our main findings below and included our key conclusions.

Expectation one: ICPs will drive the direction and policies of the integrated care system (ICS)

Strong relationships and a collaborative culture are critical to the development of ICPs. The level of development of these relationships differed in each area but where systems were undertaking broad engagement early, system development was working well.

The legislation enables this in a number of ways, including through the statutory duties in the Health and Care Bill and the proposed Care Quality Commission (CQC) reviews of ICSs, that will look at the functioning of the system for the provision of relevant health care, and adult social care. We expect that those reviews will look at the dynamic between the ICP and the integrated care board (ICB).

Expectation 2: ICPs will be rooted in the needs of people, communities, and places

There was strong support for the inclusive engagement of people and communities in the activities of the ICP. However, there were some questions about the potential for duplication of engagement between systems and places. The ICP should draw upon insights from the existing work of partners to inform its work.

Representation within the ICP was frequently raised in our engagement. The permissive nature of the legislation allows for local areas to make arrangements that are most appropriate for their circumstances and is conducive to collaborative working. Where appropriate, however, we have set our expectations or given suggestions about what ICBs and LAs will want to consider when establishing their partnerships. The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England (NHSE) and the Local Government Association (LGA) will continue to engage with stakeholders on the representation of specific voices over the coming months and as ICPs are established.

Expectation 3: ICPs create a space to develop and oversee population health strategies to improve health outcomes and experiences

There was support for the idea that ICPs will play a crucial role within the system to bring together partners and look beyond traditional organisational boundaries to address population health, health inequalities and the wider determinants of health, by giving the space to look at complex, long-term issues that require integrated approaches to succeed. This approach will be further reflected in the integrated care strategy guidance due to be published this summer.

We expect that public health experts, including directors of public health and their teams, will play a significant role as they can support, inform, and guide approaches to population health management and improvement.

Expectation 4: ICPs will support integrated approaches and subsidiarity

Much of our engagement confirmed the importance of ensuring that work at system level complements and supports the work undertaken at place level. Much of the transformation and integration will happen at place level and the ICP should avoid duplicating the work of the Health and Wellbeing Board or other work underway at place level, especially where there are similar geographical footprints. The Health and Care Bill and DHSC’s recently published Integration White Paper reflect these intentions, including through the single accountable person for shared outcomes at place.

There was also discussion about some of the practical roles that the ICP, rather than places could undertake including:

- advocating new approaches for places

- enabling, encouraging, and challenging places to improve and innovate

- developing system level integration strategies

Expectation 5: ICPs should take an open and inclusive approach to strategy development and leadership, involving communities and partners, and utilise local data and insights

There was a consensus that there should be an open and inclusive approach to strategy development by ICPs. Whilst DHSC does not intend to produce detailed guidance on what should be in every integrated care strategy, there was interest in who should be engaged in its development, beyond the statutory requirements.

Leadership and culture were also key factors that were raised, including who should be the ICP Chair. This is a matter for local areas, but we would expect the local authority and ICB to be actively involved in the choice of Chair so that maximum consensus can be built. A good culture will be driven by an approach that is based on shared goals and evidence and is informed by the local communities that ICPs serve. This will be underpinned by strong relationships, dedication, and hard work from the leaders within the system.

Emerging Models for ICPs

A broad and diverse range of approaches to ICP governance models are emerging, including forums, and small committees amongst the ICS areas who are further along in their ICP development.

Some areas intend for the ICB Chair to also chair the ICP, subject to the passage of the Bill, whilst some will have a Chair drawn from an LA. Some have opted for a shared or rotating co-chair model.

Membership of the ICP varies across areas, but commonly membership includes the ICB CEO, representatives from LAs, NHS healthcare providers, voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) representatives, Healthwatch and public representatives. Many ICPs have also planned to have place representatives, and others are planning to draw representation from other partners including; higher education and further education, social care providers, housing, police, justice, and Local Enterprise Partnerships.

Case studies have been included in Annex B to illustrate how systems are setting up governance models and some of the partnership working that ICPs might champion in their strategies. These case studies are intended to support conversations within systems about how they might set up their ICPs and the themes they might wish to address through partnership.

Resources and Support

DHSC, NHSE and the LGA have several resources and support programmes in place. There are others in development including:

- sharing emerging ICP practice, including via this document

- the NHS Confederation’s Integrated Care Systems (ICS) Network

- the LGA, NHS Providers and NHS Confederation’s Leading Integration Peer Support Programme

The LGA-led Care and Health Improvement Program recommended next steps

Recognising that ICPs will be at different stages of development, and vary in complexity, we have set out an indicative timeline to help all systems identify the key milestones in developing the ICP and the integrated care strategy, with 2022 to 2023 being a transitional year.

| Indicative date | Activity |

|---|---|

| April – June 2022 | DHSC to engage with systems to inform the guidance on the integrated care strategy |

| July 2022 | ICP formally established by local authorities and ICBs (subject to parliamentary passage) |

| July 2022 | DHSC to publish guidance on the integrated care strategy |

| December 2022 | Each ICP to publish an interim integrated care strategy if it wishes to influence the ICB’s first 5-year forward plan for healthcare to be published before April 2023. |

| June 2023 | DHSC refreshes integrated care strategy guidance (if needed) |

Summary of key findings and further action

Expectation one: ICPs will drive the direction and policies of the ICS

Key findings

- designate ICB leaders and local authorities should be having active discussions about the role and running of their ICPs and reaching out to wider partners if they are not doing so already

- each ICP should publish a single point of contact by April 2022, so that local partners can get in touch and discuss how they might be involved

Further actions

We expect that the CQC ICS reviews will assess the functioning of the system for the provision of relevant healthcare and adult social care, and we expect that they will look at the relationship between the ICB, and ICP.

Expectation 2: ICPs will be rooted in the needs of people, communities, and places

Key findings

- ICPs should promote a listening and responsive culture across the entire ICS, whether at system, place, or neighbourhood level, and ensuring that decisions are made as close to the people and communities they serve as possible

- Healthwatch and VCSE partners will have a critical role to play in supporting this aspect of ICPs’ work, and the ICP will need to consider the capacity of local Healthwatch organisations to do so effectively

- it is expected that mental health representatives will play a significant role in partnerships

Further actions

DHSC will:

- include in its guidance, recommendations for ICPs on who to consider engaging in the preparation of their integrated care strategies

- produce guidance setting an expectation that the ICP should consult local children’s leadership, and children, young people, and families themselves, on the integrated care strategy

- continue to work with organisations representing social care providers to develop principles for their involvement ICPs and ICBs

- ensure that guidance for the integrated care strategy is aligned with guidance for ICBs and providers on working with people and communities

- along with NHSE and the LGA, continue to engage with stakeholders on these issues over the coming months and as ICPs are established

Expectation 3: ICPs create a space to develop and oversee population health strategies to improve health outcomes and experiences

Key findings

- an ICP’s membership and approach should reflect its role in focussing on wider population health outcomes. All members need to recognise that it is an equal partnership.

- systems can learn from each other on how to create the right culture and dynamic between partners.

Further actions

Guidance on the integrated care strategy can further reinforce the role of the ICP to focus on the challenges and opportunities that go beyond traditional boundaries and are best addressed at system level.

Expectation 4: ICPs will support integrated approaches and subsidiarity

Key findings

- the ICP should consider the existing and potential role of place and neighbourhood to ensure that there are clear mechanisms to enable subsidiarity of decision making and that decisions are taken once at the most appropriate local level

- during the establishment phase, ICPs should actively learn from emerging models around place and ICP governance, so that they can see how similar systems are designing themselves

Further actions

- statutory guidance on the integrated care strategy should set out the challenges and opportunities which are likely to be best overseen by ICPs, as opposed to the other parts of systems (places, local authorities and ICBs)

- DHSC will refresh guidance for Health and Wellbeing Boards in the light of the wider system changes, and those proposed in the Integration White Paper.

Expectation 5: ICPs should take an open and inclusive approach to strategy development and leadership, involving communities and partners, and utilise local data and insights

Key findings

- local authorities and ICB leaders need to work together to build consensus in the selection of the ICP chair. Where local authorities and ICB are not able to identify a chair who has all their support, the local area may wish to contact DHSC, NHSE for support (see chapter on resources and support below) or the LGA to obtain help in finding a solution.

- successful ICPs will need to build a positive culture of inclusion and collaboration to achieve shared population health outcomes – the support offer is intended to assist local authorities and ICBs to achieve this

Further actions

- DHSC will publish statutory guidance on the integrated care strategy in July 2022

- DHSC will include engagement expectations in its guidance on ICP strategies

Introduction

Following the publication of the Integrated Care Partnership (ICP) engagement document: integrated care system (ICS) implementation in September 2021, DHSC, LGA and NHSE engaged with a range of stakeholders (see list at Annex A) between September 2021 and January 2022 on ICP implementation.

Key ICP requirements in the Health and Care Bill

- The Health and Care Bill proposes that the Integrated Care Board (ICB) and all upper-tier local authorities that fall within the footprint of the ICB must establish an Integrated Care Partnership (ICP).

- The ICP may make their own procedures including appointing the Chair and further members and determining the ICP’s arrangements.

- The ICP must prepare a strategy on how to meet the needs of the population – as identified in the joint strategic needs assessment from the health and wellbeing board/s that fall within the area of the ICB – through the exercise of functions by the ICB, NHSE and the upper tier local authorities.

- The strategy must address whether the needs could be met more effectively through the use of NHS/local authority section 75 agreements and may include a view on how health and social care could be more closely integrated with health-related services.

- The ICP must have regard to the Secretary of State’s mandate to NHS England (national NHS priorities) and the statutory guidance on the integrated care strategy; and the ICP must involve Healthwatch and local people and communities in preparing the strategy.

- When an upper tier local authority and an ICB receive an integrated care strategy, they must produce a joint local health and wellbeing strategy to meet the needs through the exercise of their (and NHS England’s) functions.

- The upper tier local authorities, ICBs and NHS England must have regard to the integrated care strategy and the joint local health and wellbeing strategy in exercising their functions, including the preparation of the joint-forward plan.

Other key areas of policy that were both developed by DHSC concurrently with this document were the Adult Social Care White Paper published in December 2021, and the Integration White Paper, published in February 2021. The Integration White Paper focuses on ambitions to go further and faster in joining up integration of health and social care. It sets out the ambition for developing shared outcomes for systems which will galvanise joined up approaches. It is DHSC’s aim that this will both empower place-based delivery within systems and support and drive more integrated approaches at every level.

The Adult Social Care White Paper is also designed to escalate the scale and pace of integration of health and care services at place level. It is DHSC’s view that ICPs will play an important role in bringing together housing, transport, care providers and other system partners to realise the ambition of the white paper on delivering person-centred care and support.

Furthermore, the NHS Planning Guidance for 2022 to 2023, published in December 2021, identified July 2022 as the target period for Integrated Care Boards to go live, subject to the passage of the Health and Care Bill. This followed a joint assessment between DHSC and NHSE on the factors affecting timing, including an assessment of the time needed to allow proper scrutiny of the Bill by Parliament.

This document, developed in partnership with NHSE, and the LGA, summarises the topics that were regularly raised during our engagement. In response, we have drawn out some of the initial findings from our engagement and indicated where we plan to take further action. The document has been designed with the intention of aiding those who are responsible for establishing ICPs from July 2022 (subject to the passage of the Bill), that is, local authorities and ICBs. It will also be of interest to those system partners who are critical to the success of ICPs.

This document is not a one-size-fits-all guide on how to set up and run ICPs, nor do we intend to provide that, as local areas will be able to find the arrangements most appropriate for them.

This document:

- sets out what we heard during the engagement exercise

- addresses key questions and concerns

- shares emerging practice from local partners in developing their ICP

- provides an indicative timeline and next steps for developing ICPs in 2022

- signposts available support and contact information

DHSC will publish statutory guidance on the integrated care strategy in July 2022. However, DHSC does not intend to produce detailed guidance on what should be in every Integrated Care Strategy, as there was no demand for further detailed or prescriptive guidance in this space. Rather, it intends to focus on the challenges and opportunities on which ICPs are best placed to lead, such as work that would benefit from a partnership approach, and the inclusion of specific voices.

Whilst we recognise that ICPs will be at different stages of development and that 2022 to 20 23 is a transition year as systems get established, we are encouraging, but not mandating that all ICPs to have at least an interim integrated care strategy by the end of 2022. This will ensure that, as far as possible, ICP strategies can inform and influence the first 5-year forward plan[footnote 1] which each ICB, must publish before April 2023 to fulfil their statutory duty. We would expect ICPs and their integrated care strategies to continue to evolve and mature over time.

We are grateful to everyone who engaged with this document and gave us feedback. This has shaped the document and, in turn, the work to support the development and implementation of ICPs. If you have any further feedback, please contact: icp-policy@dhsc.gov.uk

What we heard

We engaged with a wide range of stakeholders from September 2021 – December 2021 (see Annex A for the full list). This chapter summarises our main findings, to help local areas develop the most appropriate ICP for their circumstances. This section also commits to further actions to support ICP development and implementation.

Over the course of our engagement, conversations evolved as stakeholders’ awareness and understanding of the proposals in the Bill grew. Our conversations captured the diversity of ICS progress and opinion across England. Generally, there is support for the Bill’s permissive approach; and the phrase “one size isn’t going to fit all” came up repeatedly. However, there was also a view that the transition from existing system working to ICPs should build upon, and enhance, existing structures. We noted that positive culture, behaviours, and relationships enabled swifter progress.

The 5 expectations for ICPs

Our engagement discussions were largely framed around the 5 expectations we set for ICPs in our original engagement document. As such, we have also structured this paper to report back on what we heard about these 5 themes:

- expectation one: ICPs are a core part of ICSs, driving their direction and priorities

- expectation 2: ICPs will be rooted in the needs of people, communities, and places

- expectation 3: ICPs will create a space to develop and oversee population health strategies to improve health outcomes and experiences, and address health inequalities

- expectation 4: ICPs will support integrated approaches and subsidiarity

- expectation 5: ICPs should take an open and inclusive approach to strategy development and leadership, involving communities and partners to utilise local data and insights and develop plans

We heard broad support for the 5 expectations for ICPs set out in our ICP engagement document. This support was accompanied by significant discussion about how they could be embedded in practice, and what some of the challenges might be. We address what we heard about each expectation in more detail below.

Expectation one: ICPs will drive the direction and policies of the ICS

This expectation is key to ensuring we achieve our vision for systems, by ensuring that partnership approaches are at the heart of every ICS. Our engagement conversations focussed significantly on the importance of this expectation and how it can be successfully implemented.

We heard that many felt this period – prior to ICBs and ICPs being established in law subject to the passage of the Health and Care Bill – was critical to the successful implementation of ICSs. Some stakeholders said they were already communicating with the Chair designate of the ICB about how they would work together on the establishment of the ICP. In most areas, ICB Chair designates and local authorities are already working well together to establish their ICP arrangements. Several stakeholders reinforced that all partners should be engaging proactively to build the foundations for strong future relationships.

However, this was not the case everywhere. Some local authorities did not yet feel like they had established the ‘equal partnership’ with ICBs that the Health and Care Bill aspires to. Furthermore, some potential partners outside of the NHS or local authorities said that they were unclear on who they should be contacting regarding ICP establishment, and that they were unsure of how to get involved. In our engagement, it was clear that for some areas, the current focus on the operational and technical work required to establish ICBs meant that ICPs were being established more slowly.

We would expect local authorities and ICB Chair designates in every area to be having discussions about their vision for the ICP, and how they want to work together and lead it. If there are areas where this is not happening, ICB Chair Designates and local authority leaders should be reaching out urgently to make those connections.

Whilst we recognise that the ICB will play a key role in the establishment of the ICP, we heard from stakeholders that where system development seems to be working best is when designate ICB leaders, local authorities and local stakeholders engage early in the process of establishing their ICP. We expect local authorities and ICBs to be co-designing ICPs and we are clear that designate ICB leaders should not be leading the design of ICPs alone, as these are not NHS structures.

Some concerns were raised about the fact that no additional funding is being provided to support the establishment of ICPs. We expect this to be considered as part of the governance arrangements for ICPs as there are no plans for national funding to be made available for the ICPs. We do recognise that this will challenge organisations who are facing funding or resourcing pressures. However, we expect that investment in ICPs will improve partnerships and enable a better response to local needs, which will, in time, lead to a more efficient and sustainable system. To achieve this, the ICB and local authorities will want to consider how best to mutually support the ICP in its establishment phase.

We heard concerns that the ICP may struggle to influence the ICB, a statutory NHS body with local NHS priorities where these priorities may differ from those of the ICP. Some concerns were also raised about the potential for the ICB to dominate within a system given its scale; the resources available to it, and its status as a statutory body rather than a statutory committee like the ICP. We have listened carefully to those concerns and want to provide reassurance that the Health and Care Bill is specifically designed to counter this dynamic as the ICB and ICP are complementary and intrinsically connected within the legislative framework.

The Health and Care Bill includes a statutory duty for all ICBs to have regard to the integrated care strategy when exercising their functions and specifically in developing their 5-year forward plans. The Bill also requires that local authorities have regard to the integrated care strategy in exercising their functions. The legislation also provides that the ICB and LAs will establish the ICP jointly, we would therefore expect the ICB to be fully engaged with the work of the ICP. Whilst the relationship and dynamic between the ICP and ICB may differ across systems, it is important that the ICB and ICP should agree how they will work together and set out these arrangements including how the integrated care strategy will be reflected in the ICBs plans. For more detail about the duties of the Health and Care Bill relating to ICPs, please see Annex C.

The proposed CQC reviews of Integrated Care Systems will allow the CQC to look broadly across the system to review how ICBs, local authorities and providers of health, public health and adult social care services are working together. This can include, for example, the role of the ICP and ensuring that ICBs and ICPs are equal partners within the system. DHSC will continue to engage with CQC on these issues as they develop their ICS review methodology.

DHSC, NHSE and the LGA are clear that all ICBs and their partner NHS trusts will need to demonstrate how they have considered any relevant joint local and health and wellbeing strategies, joint strategic needs assessment, and the integrated care strategy in preparation of their 5-year forward plans. We are clear that the ICB can only exercise its statutory responsibility if it is taking full account of the integrated care strategy.

Many areas are already working to ensure a balanced relationship between the ICP and the ICB, by creating a strong and empowered ICP from the outset. There is much to learn from these examples; establishing a collaborative and outcomes-focused culture and approach from the outset will be the key to delivering a successful and influential ICP.

Key Findings

- designate ICB leaders and local authorities should be having active discussions about the role and running of their ICPs and reaching out to wider partners if they are not doing so already

- each ICP should publish a single point of contact by April 2022, so that local partners can get in touch and discuss how they might be involved

Further actions

We expect that the CQC ICS reviews will assess the functioning of the system for the provision of relevant healthcare and adult social care, and we expect that they will look at the relationship between the ICB, and ICP is operating effectively.

Expectation 2: ICPs will be rooted in the needs of people, communities, and places

We expect that the design of ICPs will place people, communities, and places at their heart. There was strong support for involving partners and communities in an inclusive way, but this expectation generated some questions and discussion concerning the respective role of systems and places in engaging with the needs of people and communities and about membership.

ICPs will specifically be tasked to work with people and communities on the development of their integrated care strategy through existing engagement channels of all partners, making connections to existing community fora and democratic representatives. This will allow decision making within the ICP to be informed by the views of people and communities.

NHSE and DHSC are producing statutory guidance for ICBs and providers on working with people and communities. This will be subject to public consultation before publication in Summer 2022. We recognise the need to ensure that broader engagement is aligned across the different parts of systems, and that people and communities are involved from neighbourhood level upwards. We will therefore need to ensure that guidance for the integrated care strategy is aligned with guidance for ICBs and providers on working with people and communities.

We heard some concerns around duplication of engagement within systems. ICPs should use insights from existing work with residents to inform the strategy and work of the ICP, and not duplicate engagement already being done by partners. ICPs should draw on the diverse thinking of local people, including those who need care, and unpaid carers to shape their plans, working with Healthwatch and VCSE partners to reach local communities.

Healthwatch has a specific statutory role within ICPs. The proposed legislation will require ICPs to involve their local Healthwatch organisations on the preparation of their strategies. Healthwatch England sees the role of local Healthwatch organisations within the ICP as embedding a culture of active listening, responding to community concerns across the whole system, and scrutinising local decisions. Local people and patients will want to know that their voices are being heard and their views are acted upon. As the public champions in health and social care, and with links into seldom heard communities, local Healthwatch organisations are well placed to support work of the ICP. In determining their arrangements, ICPs will want to consider how they will engage their local Healthwatch organisations, and other organisations focused on public involvement, in their work, and arrangements, especially true where there are multiple, similar organisations in an area. We will continue our work to involve Healthwatch England in the development of ICPs and ensure that they are rooted in the needs of people and communities.

Our engagement also covered the broader question of membership of ICPs. We understand the desire for clarity on the structure and membership of the ICP. However, ICPs will have the freedom and flexibility to find the best arrangements for their areas. We will work with systems and places to identify good practice in ICP development from which other areas can learn, and we welcome further engagement from stakeholders on models that are working well for their geography or sector.

Some stakeholders expressed a preference for amending the legislation to extend statutory membership of ICPs. We recognise concerns about ensuring appropriate representation but feel this is a decision best left for local determination, recognising the diversity in approaches and circumstances across systems.

Some local authority stakeholders were concerned that the ICP may not understand Borough and District Councils’ contributions to health and wellbeing. The legislation will allow for systems to determine their structures and memberships to reflect the breadth of the local authorities’ contributions to health and wellbeing most appropriately. In some areas, there will be place-based representatives, and ICPs may choose, where applicable, to have their lower-tier local authorities represented. Stakeholders that sit across the footprint of more than one ICS area were concerned about capacity if they have to sit on more than one ICP, for example, Ambulance trusts. We expect ICPs to consider the capacity of their partners, and where appropriate, make arrangements that will facilitate the effective involvement of those partners.

Social care providers were keen to play a part in developing the integrated care strategy but also concerned about their capacity to play an active role in ICPs due to the time and resource required to participate. We would expect ICPs to find ways of working with social care providers to enable their participation. One home care provider felt that they were “quite literally invisible”, sometimes “GPs do not even know who their home care providers are.” We recognise this challenge, given the number of social care providers and settings in any given system. This is why, DHSC and NHSE are working with organisations representing social care providers to support the involvement of the sector in both the ICP and ICB and to ensure systems understand the important role that social care providers play.

There was an ask for greater clarity about what “representation” means in the context of ICPs, and whether non-statutory members will have voting rights on the Partnership. We understand that the issue of voting rights is an important matter for many, but we would expect partners to work together to build a shared strategy and that the ICP will determine its arrangements in a way that builds consensus for that strategy.

Because of the scale and breadth that ICPs are intending to cover, engagement will be broad and some ICPs may need a steering group to bring the strategy together. We expect the partnership arrangements and culture to extend far beyond formal ICP meetings, to relationship building that generates real alliances, insights, trust-based relationships, and genuine influence over the direction of travel. This might be via working groups, or wider reference groups and workstreams. In ICPs, the ability to influence should be the key factor, rather than voting rights.

There was particular concern from the following groups about how their specific voices would be heard by ICPs and we have set out our response so far to these concerns below.

Babies, children, young people and families

Subject to the passing of the Health and Care Bill, the Secretary of State will issue statutory guidance for ICPs in connection with the preparation of the integrated care strategy. We intend that this will, contain guidance on how the ICP can best consider the assessed needs of children and young people, including their health and wellbeing outcomes. The legislation provides that ICPs may include in the strategy a view on how arrangements could more closely integrate health services, social care services and health related services. It is intended that the guidance will particularly include how an ICP can address integration of children’s and family services.

Social care providers

DHSC are working with providers to support their engagement in the work of ICPs and systems.

Mental health

It is expected that mental health representatives will play a significant role in these partnerships, given the importance of ensuring parity of esteem across mental and physical health. To reinforce this, the Government brought forward an amendment to the Health and Care Bill to clarify that the meaning of “health” includes “mental health” (unless the context otherwise requires).

Unpaid carers

The Health and Care Bill provides an opportunity to create a health and care system that is more accountable and responsive to the people that use it. As part of this we are committed to ensuring that the voices of carers – as well as those who access care and support – are properly embedded in Integrated Care Systems (ICSs). The Bill provides a duty on integrated care boards (ICBs) to and involve carers when exercising their commissioning functions and we would expect ICPs to also involve carers.

There is of course a broad spectrum of stakeholders who will be keen to have their voices heard on ICPs, so this list is not intended to be exhaustive of the range of voices we heard during the engagement process, but it does provide a sense of the range of interest groups. Local Healthwatch organisations and VCSE partners will have a critical role to play in ensuring a broad range of voices are engaged in the ICPs’ work. The ICP will need to ensure that when determining their arrangements, they are mindful of the level of resource and capacity available to the local Healthwatch organisations, and VCSE partners to contribute effectively to the work of the ICP. DHSC, NHSE and LGA will continue to engage with stakeholders on these issues over the coming months as appropriate and as ICPs are established.

Key Findings

- ICPs should promote a listening and responsive culture, between the local authorities, ICBs and system partners, whether at system, place, or neighbourhood level, and ensuring that decisions are made as close to the people and communities they serve as possible.

- Healthwatch and VCSE partners will have a critical role to play in supporting this aspect of ICPs’ work, and the ICP will need to consider the capacity of local Healthwatch organisations to do so effectively.

- it is expected that mental health representatives will play a significant role in partnerships.

Further Actions

- DHSC will include recommendations on who to consider engaging in the preparation of integrated care strategies in its guidance on integrated care strategies

- DHSC will also set an expectation that the ICP should consult local children’s leadership, and children, young people themselves, in the preparation of the integrated care strategy. DHSC and NHSE are working with organisations representing social care providers to support involvement of the sector in ICSs

- we will ensure that guidance for the integrated care strategy is aligned with guidance for ICBs and providers on working with people and communities

- DHSC, NHSE and LGA will continue to engage with stakeholders on these issues over the coming months as appropriate and as ICPs are established

Expectation 3: ICPs create a space to develop and oversee population health strategies to improve health outcomes and experiences

In our engagement, we heard support for the idea that the ICP, when developing their integrated care strategy, will bring together wider system partners to address health inequalities; to tackle the wider determinants of health that require a joined-up, multi-agency approach. This was seen as one of the key opportunities for ICPs – to marshal the experience of health and care organisations, but also to reach beyond the traditional boundaries. This may be to organisations such as, but not limited to, VCSE sector, housing, family hubs, employment, and criminal justice partners. There are also opportunities to engage with organisations with an interest and role in supporting the design and delivery of health and care services to the whole population. This will also include groups who represent those with mental health needs, learning disabilities and autism, babies, children, young people, and unpaid carers. This approach to joint working will develop proactive and preventative approaches that turn the dial on population health; health inequalities and improve people’s overall experience of care and support.

Stakeholders, particularly those outside of the NHS, were concerned to ensure that the system, and ICPs in particular, take a wider perspective on population health. The ICP is intended to provide a protected space within each system to consider longer-term issues which are complex to solve and require joined-up approaches, such as, but not limited to, addressing the health needs of socially excluded and marginalised populations such as inclusion health groups.

ICPs provide an opportunity to look beyond traditional organisational boundaries by sharing learning and insights. We expect the approach to be led by local data and evidence, as well as co-production with the wider health and care system and community representatives. This will be further reflected in the guidance on the integrated care strategy that DHSC intend to publish in July 2022.

Directors of public health (DPHs) have sought greater clarity on their role in ICPs and across the ICS as a whole. We expect public health experts to play a significant role in these partnerships. Local authority directors of public health and their teams can support, inform, and guide approaches to population health improvement, and in plans to identify and address health disparities, with directors of public health having an influential role in the ICBs and Partnership. DHSC are working with stakeholders to help describe further, the outcomes we hope to collectively achieve and the ways in which directors of public health can best add value to the system’s impact on health overall. For example, the Bill includes a duty on Integrated Care Boards to seek advice from persons with the appropriate expertise on prevention and public health – this may include directors of public health (which complements the existing duty in section 6C regulations for local authorities to provide the NHS with public health advice).

Key findings

- the ICP’s membership and approach should reflect its role in focusing on wider population health outcomes and reducing health inequalities, making use of up to date and shared insights and data to maximise outcomes

- systems can learn from each other on how to create the right culture and dynamic between partners

Further actions

Guidance on the integrated care strategy can further reinforce the role of the ICP to focus on the challenges and opportunities that go beyond traditional boundaries and are best addressed at system level.

Expectation 4: ICPs will support integrated approaches and subsidiarity

Our engagement reiterated the importance of ensuring that the work undertaken at system level complements, supports, and enables the work undertaken at place level. There was a broad agreement that integration and transformation happen largely at place level, where much of the collaboration between the NHS and local authorities will be devolved from system to place level. We are clear the ICP should not be duplicating or undermining that work. Decision making and service delivery needs to happen at the right level and in many cases, when it came to integration, that level was place.

This thinking is embedded in the design of the legislation – it is why the legislation, if passed, will require the integrated care strategy to set out how the needs assessed in the joint strategic needs assessment (JSNA) for the ICB area are to be met by the exercise of NHS and local authorities functions. In the preparation of the JNSAs, the responsible local authorities, and partner ICBs must involve the Local Healthwatch organisations for the area and involve the people who live or work in that area; and where applicable, each relevant district council. The JSNAs will be complemented by the Joint local Health and Wellbeing Strategy prepared by each local authorities’ health and wellbeing board and their partner integrated care board/s in response to the integrated care strategy, which are expected to be particularly important in large ICSs with multiple local authorities. For Further detail on the Health and Care Bill, see Annex C.

This thinking underlines that identifying needs and integrated solutions to meet them starts with individuals, their families, and neighbourhoods, building up to place. From April 2023, as set out in DHSC’s Integration White Paper, it is proposed that there will be a single accountable person for shared outcomes at place. This will then build up to system level, joining up care for whole populations.

The ICP will need to work with places to agree on the right activity at the right level and avoid duplicating work. This was an issue raised particularly in those systems that were geographically small, where there is often only a single ‘place’ per system.

In many of those areas, solutions were already being found. In some smaller systems, the HWB and ICP cover a similar geography and will meet at the same time, with largely the same membership. However, the meeting agenda will make clear that there are different statutory roles being undertaken by each body.

In other areas, where there are multiple places and local authorities within an ICS footprint, there was clear acknowledgement that place will play a strong role in transformation and integration. The ICP will provide an overarching set of strategic shared priorities and enabling strategy, with flexibility for places to develop priorities specific to each place.

During our next engagement exercise, between April to June 2022, we will be using the opportunity to further engage around what will be the responsibilities of the ICP. We had initial conversations about some of the practical roles that the ICP, rather than places, would best undertake, including:

- advocating new place-based approaches – the legislation, once passed, would require that ICBs and local authorities take account of integrated care strategies, so ICPs are well positioned to advocate for considering how the needs of a place are met, whether that be through more integrated approaches, research, innovation, or investment in services for particular populations and cohorts.

- enabling, encouraging, and challenging places to improve and innovate – ICPs will be able to take an overarching look across their systems and identify differences in place-based planning and provision and opportunities for collaboration, research, peer support and learning to spread good practice. For example, the ICP can identify if one place is innovating in a new integrated delivery programme, or designing a new pooled budget, and suggest that might be something another area could learn from. They could spread ideas and expertise on transformation programmes.

- system level integration strategies – there may be particular areas of integration that could benefit from strategic oversight at system level. For example, looking at the integration of children’s health and public health services; or building an integrated workforce strategy that looks across a system footprint and links in with place-based workforce planning; or considering how the system as a whole can support wider socio-economic development and the relationship between work and health.

Key findings

The ICP should consider the existing and potential role of place and neighbourhood to ensure that there are clear mechanisms to enable subsidiarity of decision making and that decisions are taken once at the most appropriate local level. During the establishment phase, ICPs should actively learn from emerging models around place and ICP governance, so that they can see how similar systems are designing themselves.

Further actions

- statutory guidance on the integrated care strategy should set out the challenges and opportunities which are likely to be best overseen by ICPs, as opposed to the other parts of systems (places, local authorities and ICBs).

- DHSC will refresh guidance for Health and Wellbeing Boards in light of the wider system changes, and those proposed by the Integration White Paper.

Expectation 5: ICPs should take an open and inclusive approach to strategy development and leadership, involving communities and partners, and utilise local data and insights

It was generally agreed that there should be an open and inclusive approach to strategy development, particularly given that all local areas already have Health and Wellbeing Strategies, and that non-statutory ICSs may already have some form of integrated strategy. DHSC does not intend to produce detailed guidance on what should be in every integrated care strategy, as participants in our engagement did not want further detailed or prescriptive guidance in this space. However, there was some interest in who should be engaged on the development of the strategies – such as children, young people and families, and social care providers.

On the question of inclusive leadership, there was keen interest in who would be appointed to chair the ICP, which will be a decision for the ICP founding organisations (one from each local authorities and one from the ICB). In some areas, the designate ICB Chair was also the proposed chair of the ICP. In other areas, it was felt that a democratic representative would make the best chair, such as a councillor or directly elected mayor. The appointment of the ICP Chair is a local matter, but we would expect the local authorities and ICB in an area to be actively involved in the choice of chair. We would be interested to hear further if there are specific areas where the choice of ICP Chair has been a cause of concern, and to understand why.

The open and inclusive culture we are expecting from ICPs relies on encouraging and instilling the right behaviours, building trust-based relationships, and encouraging supportive and respectful engagement within and across partnerships. We heard some inspiring examples of where these sorts of cultures are already in place. We also heard of areas where more work is required to develop this sort of culture.

We recognise that the proposed legislative change is not a ‘silver bullet’. Changing culture requires hard work and dedication from all local leaders and communities. It is important that, once these relationships are established, the approach is driven by evidence and informed by the communities served by the ICP. Below we outline the support to systems to encourage an effective ICP. This will also be addressed in DHSC guidance on the ICP’s integrated care strategy in July 2022.

Key findings

- local authorities and ICB leaders need to work together to build consensus in the selection of the ICP chair. Where local authorities and ICBs are not able to identify a chair, who has all their support, the local area may wish to contact DHSC, NHSE for support (see chapter on resources and support below) or the LGA to obtain help in finding a solution

- successful ICPs will build a positive culture of inclusion and collaboration to achieve shared population health outcomes; the support offer in the next section is intended to assist local authoritiess and ICBs to achieve this

Further action

- DHSC will publish statutory guidance on the integrated care strategy in July 2022

- DHSC will include recommendations on who to consider engaging in its guidance on integrated care strategies

Emerging models of ICPs and next steps

Emerging models of ICPs

There is significant variation in ICS geographies across the country and, unsurprisingly, we also heard about significant variation in approaches to ICPs. Areas with a small well-defined geography or where the existing non-statutory ICS is already fulfilling much of the future role of the ICP tended to have more developed thinking on ICPs, but this was not yet the case everywhere.

There is large variation across systems in the emerging models and approaches to ICPs. For example, some areas are approaching the ICP as a broad forum with over forty members whilst others will be less than half that size.

The approach to the chair also varies with some proposing the ICB Chair will also be their ICP Chair, whilst others are proposing that they will be chaired by a local authority representative, typically an elected member on a permanent basis, co-chair with the ICB chair or a rotating convenor.

Membership typically includes the ICB CEO, local authority representatives (including particular professions or expertise e.g., children’s services), NHS providers, VCSE representatives, Healthwatch and public representatives. Many ICPs are also planning to have specific place representatives. Some areas plan to draw representation from educational institutions (higher education and further education), social care, housing organisations, police, justice, and Local Enterprise Partnerships.

We have provided some case studies (Annex B) to illustrate how systems currently are working on setting up their governance models. These examples are not a blueprint but are intended to support conversations and reflections on how systems could approach their ICP in particular to give insight into the relationship with the ICB and with place.

Resources and support

Several resources are already in train or planned to support ICP establishment and development. DHSC welcome views on what further support and resources would be most useful.

DHSC, NHSE and LGA will continue to share emerging ICP practice, building on the case studies and examples that accompany this report, and using mechanisms such as national webinars, websites, and network meetings.

NHSE regional teams and the LGA Care and Health Improvement Advisers and Principal Advisers work closely with NHS and local government partners at system and place footprints and are well placed to understand specific support needs and opportunities and signpost to appropriate regional and national support.

The NHS Confederation’s ICS Network is an independent national network which supports ICS leaders. This will include a dedicated national network for ICP Chairs, delivered in partnership with the LGA.

NHSE commissions a sector-led Leading Integration Peer Support Programme from the LGA, NHS Providers and the NHS Confederation to support partnership development in health and care systems including ICPs and can be deployed for tailored support to systems that would value this.

DHSC commissions the LGA-led Care and Health Improvement Programme which can also be deployed to support ICP development involving local government and wider system partners such as the NHS and social care providers.

Recommended next steps

Recognising that ICPs will be at different stages of development, and vary in complexity, we have set out an indicative timeline to help all systems identify the key milestones in developing the ICP and the integrated care strategy, with 2022 to 23 being a transitional year.

| Indicative date | Activity |

|---|---|

| April to June 2022 | DHSC to engage with systems to inform the guidance on the integrated care strategy |

| July 2022 | ICP formally established by local authorities and ICBs (subject to parliamentary passage) |

| July 2022 | DHSC to publish guidance on the integrated care strategy |

| December 2022 | Each ICP to publish interim a strategy if it wishes to influence the ICB’s first 5-year forward plan for healthcare to be published before April 2023. |

| June 2023 | DHSC refreshes integrated care strategy guidance (if needed) |

Annex A: list of stakeholders

During our engagement, we heard feedback from the following stakeholders:

Association of Ambulance Chief Executives

Carers Trust: Network Partner’s Policy Forum

Home Care Providers

ICS Clinical and Care Professional Leader’s Network

ICS Readiness Reference Group (Healthwatch)

Integrated Care Delivery Partners’ Group

LGA Community Wellbeing Board

LGS ICS engagement workshop

Local Government Health and Care Sounding Board

Mental Health Policy Group

National Children’s Bureau

NHS Confederation - ICS Network

NHS Providers

NHSEI Regional Roadshow: Southeast

NHSEI Regional Roadshow: East of England

Social Enterprise UK

Southeast ADASS

The Care Provider Alliance

VCSE and ICS Leaders Network

Annex B: case studies

During our engagement we heard examples of where systems were already thinking about how to structure their ICP as well as inspiring examples of how partnership approaches can lead to improved outcomes and experiences. We had requests to share examples that other systems could learn from. We expect all ICPs, including the examples below, will continue to evolve and mature. We hope that these examples will help systems to reflect on their own approach and support productive conversations, but recognise that these are a snapshot in time, and may yet be subject to change. We aim to add to our repository of case studies over time.

Governance models

The examples below show the approach that some systems are taking when developing their ICP. These are not the final position given that the legislation has not yet been commenced and will continue to evolve over time, but they give an idea of the proposed membership and role of the ICP.

Emerging model one: Surrey Heartlands

Surrey Heartlands are designing their ICP to be a collaborative forum where local government, the NHS and the voluntary, community and faith sector can build a partnership rooted in the needs of Surrey’s people, communities, and places. This builds on a long standing and ambitious partnership between Surrey Heartlands and Surrey County Council.

The key intentions for the ICP are to:

- drive ICS direction and priorities

- create a space to develop and oversee population health strategies to improve health outcomes and experiences

- support integrated approaches and subsidiarity

- take an open and inclusive approach to strategy development and leadership, involving communities and partners to utilise local data and insights

The ambition is that, by harnessing the involvement of the wider system, the ICP can build greater collaboration between the NHS, local government, and the community sector, and leverage the resources and the influence of the wider system to improve health and care outcomes for residents, addressing health inequalities to ensure that no one is left behind.

The strategic direction of Surrey Heartlands ICP, in addressing health inequalities, will build on and align with the priorities and goals of the Surrey-wide Health and Wellbeing Strategy. The ambition is that the ICP becomes the forum that drives Surrey Heartlands Health and Care Partnership’s preventive and community-led approach to tackling health inequalities. The partnership will address shared challenges such as workforce, estates, and digital transformation, supporting the ICS’s work with the wider system.

The ICP will start meeting in shadow from March 2022 and is currently developing the terms of reference. The partnership will be chaired by the Leader of Surrey County Council, who is also Chair of Surrey’s Health and Wellbeing Board. Membership of the ICP is drawn from Surrey Heartlands ICS, Surrey County Council, representatives of Surrey’s district and borough councils and representatives from Surrey’s voluntary, community, and faith sector. The Partnership includes the Director of Public Health, the Executive Director of Children, Families and Lifelong Learning, the Joint Executive Director for Integrated Commissioning and Adult Social Care (a joint appointment between Surrey Heartlands ICS and Surrey County Council) and the Joint Executive Director for Public Service Reform, whose role supports pan-ICS thinking with regards to estates, data and business intelligence, research and innovation and the wider public sector reform agenda.

Emerging model 2: Coventry and Warwickshire

Since December 2017, Coventry and Warwickshire Health and Wellbeing boards (HWBs) have been meeting as the Coventry and Warwickshire Place Forum. Coventry City Council and Warwickshire County Council are key partners in supporting the development of the ICS arrangements for Coventry and Warwickshire.

Place-based partnerships

Leaders within Coventry and Warwickshire have agreed the primacy of place within the ICS. As part of this they have endorsed the creation of 2 ‘place-based partnerships’ referred to as the Coventry Care Collaborative and Warwickshire Care Collaborative. The care collaboratives will constitute a partnership of organisations responsible for organising and delivering health and social care within the Coventry and Warwickshire footprints. They will take responsibility for translating the ICB plan and ICP strategy into action for Coventry and Warwickshire respectively ensuring they meet the healthcare needs of the population.

Partnership board membership

The Coventry and Warwickshire Health and Care Partnership Board works across organisational boundaries for all communities across Coventry and Warwickshire. The Partnership Board has an Independent Chair, and its other Partnership Board members include the chief executives and most senior leaders of the NHS, public health, and social care services. The Partnership Board oversees all the Coventry and Warwickshire Health and Care Partnership work programmes

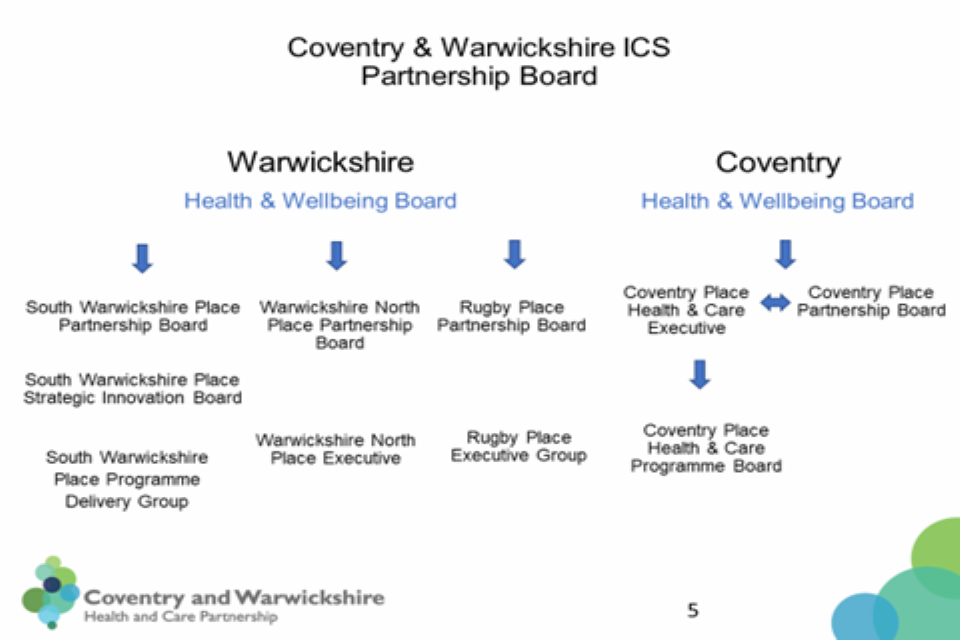

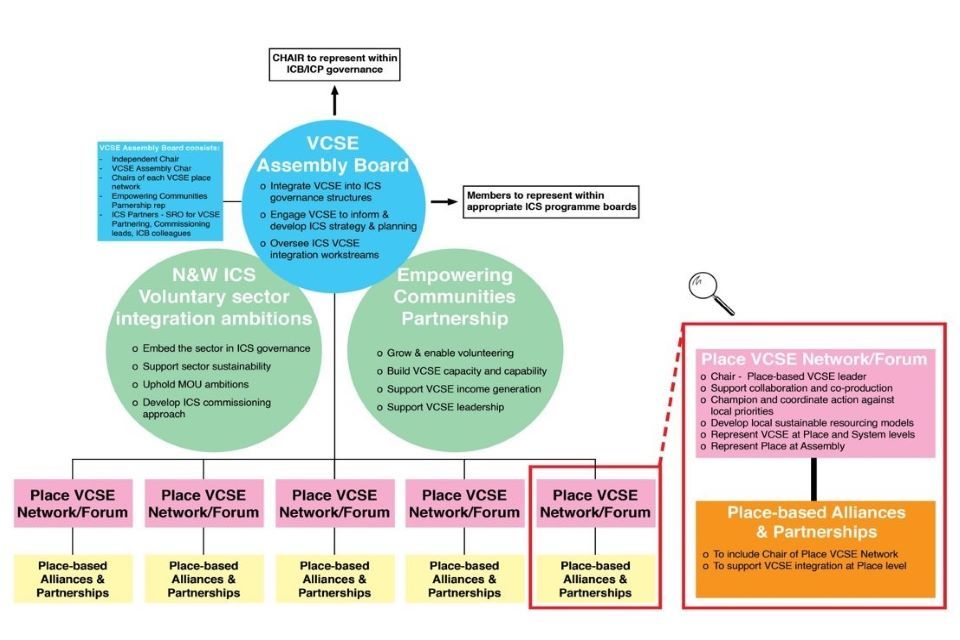

The Coventry and Warwickshire ICS Partnership Board is supported by the health and care partnership arrangements that have been developed in each of the 4 places: Coventry, Warwickshire North, Rugby, and South Warwickshire. Each of these has their own Place Partnership Board which will bring together local organisations. The Warwickshire North Place Partnership’s stakeholders, for example, include representatives from the VCSE sector through the Warwickshire Community Action and Voluntary Action group, as well as the police, Healthwatch, community pharmacists, primary care networks, and district and borough councils

Organogram of the Coventry and Warwickshire ICS Partnership Board and Health and Wellbeing Boards

Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership Board organogram

Emerging model 3: Frimley

Frimley has a complex geography which covers more than one local authority area including Bracknell Forest, Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, Slough, Surrey Health and North East Hampshire, including Farnham.

Frimley has taken a collaborative approach to the development and future working of its integrated care partnership (ICP). It undertook a period of intense stakeholder engagement during the Autumn which included a series of semi-structured interviews with elected members, local authority executives and primary care practitioners. This engagement period explored options for the development of the ICP with several thematic issues identified which are being built into the final design choices being made.

Proposals for the composition of the integrated care board (ICB) and a set of principles for the operation of the ICP were based on this engagement work and a design group was established co-chaired by the ICB Chair Designate, Dr Priya Singh, and a local authority representative. The design group is currently working through the final level of detail required to establish the ICP with the aim of leading by example around their key principles, including taking a behavioural and values approach to change.

Key principles – findings from the stakeholder engagement period

The role and remit of the integrated care partnership

- at the heart of our new systems, structures, and constructs there must be a focus on communities and populations, not governance, organisations, or sectors.

- ‘wider determinants’ of population health and wellbeing need to be a stronger and more explicit theme of our future shared focus e.g., housing, education, transport, skills and the green agenda

- this group will be a core component of our collective effort to reduce health inequalities and take a population health improvement approach to strategy development.

- the ICP must keep setting the tone of the partnership to continue defining what “integration” really means. If all partners engage in their most productive way, then anything could be possible

Design elements of the integrated care partnership (and associated constructs such as ICB, place)

- the ICB and the ICP work in unity as a broader partnership, and we will need to ensure the ICP can operate in a way which reflects this elevated role within the ICS

- all of our places are different but none of them are “detached” from our ICS – we need to recognise and tailor our approach to suit this with an ICP which reflects our diversity and connection with and between places

- there is a challenge in balancing inclusivity with a meeting / partnership that is effective in discharging its aims - too many attendees could be unwieldy or dilute our approach

- we must capitalise on our expertise where we find it – for example, local authorities have the experience and expertise of broader social and economic development

Who needs to be part of the ICP

The ICP is an important part of our new way of working; it must have broad representation from all organisations, including VCSE and patient representatives.

What success looks like

- ‘success’ is our residents having better underlying health and quality of life, and not needing to use services as much

- all partners in the ICS will feel like they have an equal voice on behalf of their populations, and high trust and strong relationships with each other

- success will be underpinned by effective communication, having wider voices and positive collaboration, with strong willingness to listen and open to influence

Our biggest risks to achieving this

- ICP strategy does not have the desired influence on partner organisations in the system. There is a risk that complexity hinders intuitiveness as well as accessibility and understanding of wider partners and public

- entrenched silos, entrenched culture. Protection of structures and influence can win out over transformation and the ICP must be a guardian against this risk

To ensure continued collaboration the ICP will operate as an assembly to bring members together to discuss issues, to reach a conclusion about what they think should happen. The Partnership will be led by a convenor elected on a time limited basis rather than by a chair.

Membership will be drawn from all local authority organisations within the ICB area (Unitary, County Council and District / Borough Councils) including:

- chief executive or director of adults and / or director of children services

- health and wellbeing board representatives

- all NHS organisations within the ICB area (ICB, Berkshire Healthcare FT, Frimley Health FT, Surrey and Borders Partnership FT)

- GP Practices within the ICB area, represented by primary care networks through a representative model (to be determined)

- all Healthwatch organisations within the ICB area (either individually, collectively or through a rotation model)

- voluntary, charity and social enterprise representatives

The ICP will start meeting in shadow form later in 2022.

Future membership of the ICP is likely to include alumni from Frimley’s own leadership academy network established in 2018 to encourage and cultivate leaders in its system who are innovative, empowered, and influential leaders working at the coal face, to make change happen working across traditional organisational boundaries to positively impact the local population and communities.

Emerging model 4: anonymous ICP

Purpose and function

This shadow ICP’s primary purpose will be to act in the best interest of people, patients, and the system as a whole rather than representing the individual interests of any one constituent partner, although during phase one, membership will include representation from both partners and individual organisations.

The shadow ICP will:

- be a forum to build on the joint positive working between the NHS and local authorities during Covid-19

- oversee integration between the NHS and social care (including conversations about shared budgets and Better Care Fund) and the NHS and public health

- drive the delivery of a shift of resources into prevention

- provide the opportunity to unblock obstacles to success emerging in local place alliances

- hear the voices of those on the frontline so that they inform strategic thinking and planning

- sign off the strategic intent for the health and social care system including the development of the integrated care strategy

- develop a clear view on the contribution of the health and social care system into prevention and the determinants of health, including our collective “anchor” approach

- support the work of the health and wellbeing boards (HWBs) and respond to their strategies

- work with broader partners on the wider determinants of health and develop the framework for its future approach to these

Membership

Members are selected to be representative of the constituent partnerships, although it is acknowledged that in phase 1 individuals may be representing both their respective organisations and their constituent partnerships and will attend to promote the greater collective endeavour.

Members are expected to make good 2-way connections between the ICP and the constituent partners, modelling a collaborative approach to working and listening to the voices of people, patients, and the public. District council members attend on behalf of the other district councils and therefore have an obligation to feed in and out from the broader group of district councils.

It is expected that members will prioritise these meetings and make themselves available; exceptionally where this is not possible a deputy of sufficient seniority may attend. They will have delegated authority to make decisions on behalf of their organisation in accordance with the objectives set out in the terms of reference for this group. For local authority representatives, this will be in accordance with the due political process. Members are expected to attend at least 75% of meetings held each calendar year.

The membership is as follows:

Rotating chairs (3):

- city council Health and Wellbeing Board chair

- county council Health and Wellbeing Board chair

- ICB board chair

Vice chair: as above

Statutory local authority officers (3) comprising:

- director of adult social services

- director of children’s services

- director of public health

Political leadership (4) comprising:

- chairs of Health and Wellbeing Boards

- council cabinet member for adult social care and health

- council cabinet member for children and young people

- council cabinet member for public health

Statutory district council chief officers (2)

District council elected members (2)

NHS partners (11) comprising:

- ICB (3) to include the ICB chair (part of rotating chair arrangement), the ICB CEO and a further executive or non-executive member

- 5 acute CEO representatives (one ambulance service)

- primary care network (PCN) clinical director

- place partnership chair

- provider GP leadership board chair

- clinical professional leadership board chair

VCSE (2)

Healthwatch (2)

Public and patient experience will feed into the ICP through its engagement activities and its citizens panel, which will inform all the work of the partnership.

Thematic case studies

The thematic case studies demonstrate the potential of ICPs to develop and drive forward partnership approaches in their areas. We hope these case studies may provide some inspiration for areas as they consider the opportunities to improve outcomes and experiences that can arise from partnership approaches.

Thematic case study one: out-of-hospital care models for people experiencing homelessness (OOHCM)

Location: Brighton and Hove

People experiencing extreme social exclusion, including homelessness and rough sleeping, have significantly poorer health outcomes and die much earlier lower life expectancy than the general population. The mean age at death was 45.9 years for males and 41.6 years for females who were homeless in 2020. These groups are often less able or willing to access health care in the community, and therefore make greater use of urgent and acute health care services. This includes attending, and being admitted to, hospital many times more than the general population, often staying for longer, but also self-discharging or being discharged to the street. Readmissions are common.

Local health, care and housing ‘systems’ often fail to come together to provide appropriate homes, care and support at the right time, to prevent a return to homelessness following a hospital visit, and further health crises.

To overcome this problem, Brighton and Hove Council working with UHSFT (acute trust), SCFT (community trust), SPFT (mental health trust), introduced the Out-of-Hospital Care Model (OOHCM). This includes ‘Step Down from Hospital’ accommodation of 5 new units of 24 hour supported accommodation with clinical in-reach, on site care services and resettlement and reconnection support.

This provision fills a gap in Brighton and Hove’s already well-developed health and care system for people experiencing homelessness, which includes a specialist ‘inclusion health’ GP practice (Arch Health CIC), a community nurse team and a mental health team, and a specialist ‘Pathway’ hospital team. Working with housing and support services, including Brighton’s Street Outreach Service, these services come together to support people to stay healthy and well in the community, and are now also able to support the safe and timely discharge of people who need to use the hospital.

Individual challenges faced:

- it takes time for workforces to be trained to understand what the new service does and how to access it: there was an initial lack of clarity about the referral criteria, particularly in A&E

- lack of suitable accommodation to move on to, after a stay in the ‘step down’ accommodation, meant many residents have stayed for longer than necessary, preventing others from accessing the service

- patients/residents are often ‘entrenched’ and building a relationship of trust can be a slow and gradual process limiting obvious ‘success’

- despite specific mental health services, these are insufficient to meet needs identified by the OOHCM service

Solutions and ways of working:

- new services/ways of working need adequate planning time to co-create a vision for the project, to define and align access criteria from the beginning

- consideration to mental health needs, and engagement with mental health services should be built in from the start

- a balance needs to be struck between flexibility, and clear processes, pathways, and structures

- one referral route into Step Down accommodation streamlines and simplifies the process

Thematic case study 2: rapid access to (alcohol) detox acute referral (RADAR)

Location: Greater Manchester

RADAR is a partnership between the local acute hospitals and the local mental health NHS provider and the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation (GMMH) who operate the Chapman-Barker Unit.

Alcohol problems are becoming a major public health concern, with alcohol admissions an increasing burden on acute hospitals. The RADAR pathway at the Chapman-Barker Unit, was introduced to address this problem. RADAR has 4 main aims: reducing the burden on acute trusts, improving clinical outcomes for service users, providing improved experience for service users in a therapeutic setting and demonstrating cost-effectiveness. In accordance with these aims, the service focused on specific subgroups of alcohol related admissions such as those who frequently present to acute hospitals.

The RADAR pathway transfers acute presentations from 11 A&Es in Greater Manchester to a specialist in-patient detoxication facility, which is run by the Chapman Barker Unit. This service admits patients 24/7 a day, 365 days a year. The Chapman Barker Unit identified 10 beds and a specialist detox programme, combining the benefits of a 5 to 7-day detoxification with the delivery of a range of psychological interventions, including physical and mental health care and support and a strong focus on assertive aftercare. The RADAR pathway is extremely cost-effective and beneficial for service-users. An independent academic of RADAR has shown that 50% of unplanned admissions maintained not drinking at a 4 week follow up.

Individual challenges faced:

- during the outset of RADAR there was difficulty of understanding the pathways aims, and objectives.

- the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance can be limiting, it recommends inpatient detox only as a ‘last resort’ when community options have failed

- complex cases, such as alcohol-related brain damage, or homeless patients may lead to delayed discharges from in-patient care

- perceptions that the care pathway is being used as a fast track to detox; there have been occasions where community teams have advised patients to present to A&E and ask for RADAR admission rather than the primary aim of preventing admissions to acute hospitals

Solutions and ways of working:

- identified a RADAR led to offer regular updates and training to all areas

- the inpatient detox provider, the Chapman-Baker Unit works closely with A&E’s and acute hospitals to ensure ownership of the pathway

- regular engagement with the 11 acute hospitals, including annual event held at the unit