Health and social care integration: joining up care for people, places and populations

Updated 11 February 2022

Applies to England

Foreword: Rt Hon Sajid Javid, Health Secretary and Rt Hon Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

The storms we have weathered over the past 2 years have been a great test, but also a great teacher.

We have learned, most notably from our world-leading vaccination programme, that we are stronger when we work together and are united in our purpose and resolve.

We have also seen the moral outrage of persistent health disparities, mirroring other disparities in our society, illuminated as never before in our lifetimes. We have been reminded, once more, of the inextricable link between health services and social care.

So, as we recover and level up, it is right that we draw on our experience of the pandemic to bridge the gaps between health and social care, between health outcomes in different places and within society that are holding us back.

This is what our white paper aims to achieve by bringing together the NHS and local government to jointly deliver for local communities.

It sets out a new approach with citizens and outcomes at its heart instead of endless form-filling, unnavigable processes and a bureaucracy which sees too many people get lost in the system, not receiving the care they need. It is the start, not the end, of a new wave of reform which will both put power and opportunity in the hands of citizens and communities and build a state that is sustainable and just.

Through introducing a single person accountable for delivery of a shared plan at a local level, our proposals will ensure a more joined-up approach between health and social care. It will give health and social care professionals access to the right data and technology to make more informed decisions, and it will also help to create a more agile workforce with care workers and nurses easily moving between roles in the NHS and the care sector.

Moreover, the white paper also delivers on our ambition to level up health outcomes over the long term.

It champions health and well-being as a real priority and places a much greater emphasis on prevention.

To that end, it promotes community-centred care to help people with disabilities, who are suffering from dementia and other mental health issues to live independent and healthy lives.

Crucially, we are proposing measures to help bridge the gap in healthy life expectancy (HLE) between local areas by making sure there is universal access to high-quality treatments and support in all parts of the country.

At every step, this white paper has been shaped by the real-world experience of people as well as nurses, care workers and doctors on the front line, drawing on some of the great examples of collaborative working we have seen at a local level in recent years, not least over the pandemic.

It presents the next component of a bold vision for the future of health and social care in this country with people and patients at its very heart.

Executive summary

The NHS and local government have delivered remarkable things for the public, in the most challenging circumstances, over the last 18 months. From the extraordinary success of the vaccine programme, to meeting the needs of people previously identified as clinically extremely vulnerable and many other examples of reshaping services to continue to deliver care safely. There is a lot for local government and the NHS to be proud of and to learn from as we move into recovery from COVID-19. Through multi-agency community hubs, integrated neighbourhood teams, and other locally developed arrangements, local partners developed a shared understanding of local needs and made flexible use of resources across services to ensure that people got the support they needed. A vast range of other activity has been jointly delivered by various organisations thanks to a combined commitment to go beyond normal organisational boundaries and do whatever has been required to support their local residents. The resilience, commitment to finding a way through for citizens, and the willingness to innovate will all be just as important as we tackle the challenges ahead.

Among the lessons of the pandemic is the need to do more to bring the resources and skills of both the NHS and local government together to better serve the public. So, as well as record investment, NHS and local government reform will be needed to recover from the pandemic and deliver on the government’s priorities, including on its central mission to level up every part of the UK. Our health and care system needs to take this agenda forward with real urgency if the challenges the sectors face – both in the short and long term – are to be met; and this will need to be done with the full involvement of local leaders and the public.

Successful integration is the planning, commissioning and delivery of co-ordinated, joined up and seamless services to support people to live healthy, independent and dignified lives and which improves outcomes for the population as a whole. Everyone should receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time.

We want to go further and faster in building integrated health and care services. People should experience joined up care which makes the best use of public resources and services. While a more integrated approach clearly will not address all of the challenges facing staff, joining up services around users can also improve job satisfaction for the staff delivering them – removing some of the barriers that stop staff delivering care as they would like. This requires change that builds on improvements made across the health and care sectors in recent years.

While progress has been made, our system remains fragmented and too often fails to deliver joined up services that meet people’s needs. The goals of different parts of the system are not always sufficiently aligned to prioritise prevention, early intervention and population health improvement to the extent that is required. That needs to be our focus if we are to continue building better health, tackling unjustifiable disparities in outcomes, and ensuring the sustainability of the NHS and other public services. People too often feel like they have to force services to work together, rather than experiencing joined-up health, public health, social care and other public services.

This paper is part of a wider set of mutually reinforcing reforms: our adult social care reform white paper, People at the Heart of Care; the Health and Care Bill and reforms to the public health system. It sets out our plans to make integrated health and social care a reality for everyone across England and to level up access, experience and outcomes across the country. Specifically, this paper:

- sets out our approach to designing shared outcomes which will place person-centred care, improving population health and reducing health disparities at the centre of our plans for reform, and ensuring that accompanying oversight arrangements and regulatory structures have a clear focus on the planning and delivery of these outcomes

- sets out proposals to strengthen the health and care services in places that feel familiar to the people living in them. While strategic, at-scale planning is carried out at the integrated care system[footnote 1] (ICS) level, places will be the engine for delivery and reform

- introduces an expectation for a single person, of accountable at place level, across health and social care, accountable for delivering shared outcomes and strong, effective leadership

- sets out how we will make progress on the key enablers of integration (workforce, digital and data and financial pooling and alignment) required to further join up services around people and populations

- reinforces the role of robust regulatory mechanisms to support the delivery of integrated care at place level

Joined up care: better for people and better for staff

As people who use health and care services require ever-more joined up care to meet their needs, achieving this will make all the difference both to the quality of care and to the sense of satisfaction for staff. Without a decisive shift to consistently joined up care, we will continue to see fragmentation for people and frustration for staff. For example, closer working between primary and secondary care will improve access to specialist support and advice and enable care to be delivered closer to home, managing risk more effectively and keeping people healthy and independent. And closer working between mental health and social care services can reduce crisis admissions and improve the quality of life for those living with mental illness.

Unlocking the power of data across local authorities and the NHS will provide place-based leaders with the information to put in place new and innovative services to tackle the problems facing their communities. A more joined up approach will bring public health and NHS services much closer together to maximise the chances for health gain at every opportunity.

Shared outcomes which prioritise people and populations

Shared outcomes are a powerful means of bringing organisations together to deliver on a common purpose for the people they serve. We have set out the case for a new approach for designing and measuring progress against these. We will work with stakeholders to develop and introduce a framework with a focused set of national priorities, and an approach for prioritising shared outcomes at a local level, focused on individual and population health and wellbeing. We will set out a framework which makes space for local leaders to agree shared outcomes that meet the particular needs of their communities, whilst also supporting national priorities. Places will be able to choose health and care priorities that matter most to their citizens, alongside national commitments. Implementation of shared outcomes will begin from April 2023. There will be robust arrangements in place to assure both the planning and delivery of both national and local outcomes.

Ensuring strong leadership and accountability

Effective leadership, accountability and oversight are key to delivering integration. Local leaders – including in local government and the NHS, in partnership with their citizens – have a unique understanding of, and relationships with, their populations. We will make changes that bring together these leaders to deliver on shared outcomes in an accountable and transparent manner, through formal place-based arrangements which provide clarity over the responsibility for health and care services in each area. Several places such as Tameside have already successfully adopted arrangements of this kind.

We will set out criteria for place-level governance and accountability for the delivery of shared outcomes. We have suggested a model which meets those criteria and expect places to adopt either this specific governance model, or an equivalent, by spring 2023. The key characteristics needed in any model will be for it to develop a clear, shared plan and, crucially, to be able to demonstrate a track record of delivery against agreed shared outcomes over time, underpinned by pooled and aligned resources.

Local NHS and local authority leaders will be empowered to deliver against the agreed outcomes and will be accountable for delivery and performance against them. Any governance model should also provide clarity of decision-making, covering contentious issues, practical arrangements for managing risk and resolving disagreements between partners, and agreeing shared outcomes. There should be a single person, accountable for shared outcomes in each place or local area, working with local partners (for example, an individual with a dual role across health and care or an individual who leads a place-based governance arrangement). This person will be agreed by the relevant local authority or authorities and integrated care board (ICB). We would expect place-based arrangements to align with existing ICS boundaries as far as possible. We recognise that in some geographies this can be challenging, and we expect NHS and local authority partners to work together (drawing, where needed, on the flexibilities that the legislation will provide, subject to Parliament) to ensure that all citizens are able to benefit from effective arrangements wherever they live. These proposals will not change the current local democratic accountability or formal accountable officer duties within local authorities or those of the ICB and its chief executive.

Places will be supported by central government, NHS England, ICBs and others to develop arrangements which deliver the best outcomes for their populations.

Finance and integration

Financial frameworks and incentives can play a key role in enabling the integration of services and supporting service innovation.

Local leaders should have the flexibility to deploy resources to meet the health and care needs of their population, as necessary. NHS and local government organisations will be supported and encouraged to do more to align and pool budgets, both to ensure better use of resources to address immediate needs, but also to support long-term investment in population health and wellbeing.

Working within the principles set out in this paper, we will work with partners to develop guidance for local authorities and the NHS to support going further and faster on financial alignment and pooling. We will also review existing pooling arrangements (for example, section 75, NHS Act 2006), with a view to simplifying the regulations for commissioners and providers across the NHS and local government to pool their budgets to achieve shared outcomes. This will continue to be subject to both NHS and local authority partners agreeing what constitutes a fair and appropriate contribution.

Digital and data: maximising transparency and personal choice

A core level of digital capability everywhere will be critical to delivering integrated health and care and enabling transformed models of care. When several organisations are involved in meeting the needs of one person, the data and information required to support them should be available in one place, enabling safe and proactive decision-making and a seamless experience for people.

Digital tools will empower people to look after their health and take greater control of their own care, offering flexibility and support – through the NHS App and NHS.UK, remote monitoring and digital health apps. We will aim to have shared care records for all citizens by 2024 that provide a single, functional health and care record which citizens, caregivers and care teams can all safely access.

We will support digital transformation by formally recognising the digital, data and technology profession within the NHS Agenda for Change and including basic digital, data and technology skills in the training of all health and care staff. We will support all health and care staff to be confident when recommending digital interventions to patients and individuals using services, based on what we know works and what people want to access.

To support place-based organisations, ICSs will develop digital investment plans for bringing all organisations to the same level of digital maturity. These plans will outline how ICSs will ensure data flows seamlessly across all care settings and use tech to transform care so that it is person-centred and proactive at place level.

The digital and data transformations outlined in this document provide an opportunity for greater transparency. We will look to introduce mandatory reporting of outcomes for local places, putting citizens at the heart of what we do.

Delivering integration through our workforce and carers

The health and care workforce are our biggest asset, and they are at the heart of wrapping care and support around individuals. We want to ensure that staff feel confident, motivated and valued in their roles and that they can work together in a person’s interests regardless of who they are employed by. Staff numbers and skills across teams should be planned to meet the needs of their local populations and places. They should also be able to progress their careers across the health and social care family, supporting the skills agenda in their local economy. Our proposals in this paper build on our proposals to support the social care workforce, as outlined in our adult social care reform white paper, People at the Heart of Care.

To achieve this, ICS will support joint health and care workforce planning at place level, working with both national and local organisations. We will improve initial training and ongoing learning and development opportunities for staff, create opportunities for joint continuous development and joint roles across health and social care and increase the number of clinical practice placements in adult social care for health undergraduates.

What this means for people and communities

Taken together, these reforms will support a better joined up health and care system, with people’s wishes and wellbeing at its heart. Citizens with access to more information will be more empowered to make decisions about their care and have more choices about where and how they access care. Working with local places and ICSs, we will remove unnecessary barriers so places will be empowered to do what is best for their citizens. They will be supported to be transparent and accountable for the delivery on the outcomes which matter to communities, and variations in performance between areas will be addressed. The financial frameworks and incentives which support this will be reformed over time so that the way funding is allocated and accounted for does not prevent places and ICSs doing the right thing for the people they serve.

These reforms will help us develop a world-leading health and care system which works for every person, and where people work together to deliver continuous improvement in the delivery of health and care services. This is possible and necessary, and we will start making it a reality now.

1. Introduction: delivering more integrated services for the 21st century

The case for going further and faster on integration

1.1. When health and care organisations have a shared mission, work with their local citizens, and pool their ideas, energy and resources to serve the public, the result is often the delivery of outstanding quality and tailored, joined up care, which improves the experience and outcomes for individuals and populations. In recent years, and in particular during the pandemic, we have seen many examples of the power of collaborative working.

1.2. This is, however, far from the norm everywhere, and as the challenges of demography, the possibilities of technology and the expectations of citizens all grow, we will need to move beyond a health and care system where organisations and services operate in a compartmentalised way. People have a range of needs which cannot always be addressed neatly by one organisation or another. There is a greater need for holistic care that fits around these needs; our services, processes, institutions, and policies need to catch up. We know that, currently the public often experiences:

- a lack of coordination between the range of services looking after them. Information or actions can be lost between primary and secondary care; where primary care and hospital teams might have to form treatment plans without the crucial insights from a person’s carer; or different specialists might focus only on one or two conditions, without considering the needs of a person holistically

- organisations that are forced or incentivised – by regulation or the financial framework – to focus on their narrow set of organisational outcomes, rather than a health and care service that considers the health needs of the whole community

- duplication in use of resources or patients’ time. People being asked for the same information multiple times, by different organisations, which can lead to delays in diagnosis or treatment; or the use of NHS personal health budgets without considering whether an individual also has a personal budget for social care (and vice versa) and the impact on them of managing both budgets simultaneously

- delays in being discharged as a result of competing budgets and care processes

1.3. Ensuring there is holistic care that fits around people needs includes ensuring that people receive the right care and support, and can maintain healthy independent living, beginning with where they live, and the people they live with. Getting these housing arrangements right for individuals and communities is one example that requires the joining up of not just health and care partners, but a wider set of local government functions and housing providers. Today, too many people with care and support needs live in homes that do not provide a safe or stable environment. People’s homes should allow effective care and support to be delivered regardless of their age, condition or health status. We want people to have choice over their housing arrangements, and we also want to ensure places ‘think housing and community’ when they develop local partnerships and plan and deliver health and care services.

1.4. Over the last few years, there has been a great deal of valuable work to bring about greater integration:

- GP practices are already working together with community health services, mental health, social care, pharmacy, hospital and voluntary services in their local areas in groups of practices known as primary care networks (PCNs). Building on existing primary care services, they are enabling greater provision of proactive, personalised, coordinated and more integrated health and social care for people closer to home NHS Chief Executive, Amanda Pritchard, has asked Dr Claire Fuller (CEO Surrey Heartlands ICS) to lead a stocktake of how systems can enable more integrated primary care at neighbourhood and place, making an even more significant impact on improving the health of their local communities. This will report later in the spring

- the Better Care Fund was introduced to support places to integrate better by pooling budgets and ensuring there is joint planning between NHS commissioners and local authorities to deliver care. Better Care Fund plans have aided integrated work to support people to remain independent for longer, integration of reablement and improved performance on hospital discharge[footnote 2]

- new models of care and sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) considered local health priorities, encouraged better joint planning of services and tested innovative models of integrated care. For example, provider collaboratives in mental health have been empowered to reconfigure local services to reduce out of area placements and bring people closer to home to aid their recovery. STPs aimed to develop sustainable services to improve person-centred care in key areas and to improve hospital performance

- devolution, such as that seen in Greater Manchester, allows local places to have more flexibility to integrate care around the needs of their local populations

- local government and the NHS have jointly planned and commissioned some health services, to join up people’s experience of care and address both prevention and treatment

1.5. We know there is more we can do to better integrate health and care services, joining up planning, commissioning and delivery. We must go further, faster. The experience of COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on the health disparities which persist across the country. We need to prioritise prevention decisively and collectively, so that we build health resilience and are well placed to meet the multiple health and care challenges of our changing demographic. Done right, integration will enable concerted, collaborative effort across the whole of the health and care system to reduce the disparity gap and improve population health. In February 2021 we set out our ambitions for the future of health and social care, and for legislative reform to support this, in Integration and innovation: working together to improve health and social care for all. These proposals, including (subject to Parliament) establishing statutory integrated care boards (ICBs) and statutory integrated care partnerships (ICPs), ensure the health and care system will be much better equipped to collaborate across boundaries, make joint decisions and form alliances to tackle shared problems.[footnote 1]

1.6. These proposals were based on the learning from those at the forefront of delivering more integrated care and support locally; in particular how important their partnerships had been when responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. We remain committed to this direction of travel and just as proud of the achievements of our health and care services as they continue to rise to the ongoing operational challenges they face.

1.7. The creation of ICSs as a formal part of our health and care system is a critical opportunity to remove remaining barriers to integrated care and create the conditions for local partnerships to thrive. This paper builds on those ambitions and provides further detail on our plans to empower leaders and strengthen collective working between the NHS and local government at place to work in partnership to achieve the best for those they serve.

Case study: Teesside

Sexual health services across Teesside’s 4 local authorities, 2 CCGs and NHS England are collaboratively commissioned by one prime provider. With a strong focus on prevention, the new service has both improved access and achieved savings, and is highly rated by users, consistently getting a high score on the ‘Friends and Family’ test. It has enabled a greater focus on improving the sexual health of young people, including chlamydia screening, provision of young-people friendly services, access to contraception and outreach, and the prioritisation of HIV prevention. Using equity measures they monitor progress, not just at borough level but using universally shared outcomes.

Our vision for integrated health and care services

1.8. Integration is not an end in itself, but a way of improving health and care outcomes. Successful integration is the planning, commissioning and delivery of co-ordinated, joined up and seamless services to support people to live healthy, independent and dignified lives and which improves outcomes for the population as a whole. Everyone should receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time. Our vision is that integration makes a significant positive impact on population health through services that shift to prevention and address people’s needs promptly and effectively; but it is also about the details and the experience of care – the things that often matter most to people, carers and families. This is captured in the ‘Think Local Act Personal’ statement below:

Everyone should be able to say: ‘I can plan my care with people who work together, to understand me and my carer(s), who allow me control, and bring together services to achieve the outcomes important to me.’

National Voices, TLAP 2013

1.9. This paper seeks to deliver this vision, through the introduction of shared outcomes, agreed by all local health and care organisations, and the delivery of which all local leaders will be held to account for. To facilitate this, we outline the place level accountability arrangements to underpin delivery and the arrangements for aligning and pooling of resources, digital transformation and changes to regulation that will enable change.

1.10. Integration needs to be delivered at every level:

- individuals: for people wanting to live lives which are as healthy and independent as possible, their communities, for carers and families

- neighbourhood and communities: areas covered by, for example, primary care and their community partners

- place: a geographic area that is defined locally, but often covers around 250,000 to 500,000 people, for example at borough or county level

- system: usually larger geographies of about one million people which often (but not always) cover multiple places

- national: in this case, the whole of England

1.11. Our focus in this document is at place level. It is where local government and the NHS face a shared set of challenges at a scale that often works well for joint action. Strong places are also important for effective working at both system level (with many ICSs investing a great deal of effort into developing places within their geography) and at neighbourhood and community level (where the support of places in making improvements happen is critical to success). Our responsibility in central government to facilitate and support improvements at place level, ensuring the right structures, accountability and leadership are in place to enable effective integration locally.

1.12. Whilst children’s social care is not directly within scope of this paper, places are encouraged to consider the integration between and within children and adult health and care services wherever possible. The transition to ICSs represents a huge opportunity to improve the planning and provision of services to make sure they are more joined up and better meet the needs of babies, children, young people and families. The Independent Review of Children’s Social Care is taking a fundamental look at the needs, experiences and outcomes of the children supported by children’s social care. We will consider and respond to the recommendations and final report of the care review once it is published. Government is championing the continued join up of services, expanding family hubs to more areas across the country, and funding key programmes such as Supporting Families and supporting the implementation of the Early Years Healthy Development Review. At the recent Budget, we announced a £500 million package for these services, to provide more support for families so that they can access the help and care that they need. Ensuring that every area has joined up, efficient local services, that are able to identify families in need and provide the right support at the right time, will enable children and young people who rely on multiple public services to thrive.

1.13. This paper sets out our ambition for better integration across primary care, community health, adult social care, acute, mental health, public health and housing services which relate to health and social care.

1.14 Our plans will support the development of a health and care system which:

- is levelled-up in terms of outcomes and reduced disparities

- ensures people have access to health and care services which meet their needs, and experience outstanding quality care

- transforms where care is delivered, according to people’s preferences (including at home and in the community). This includes ensuring that people are discharged in a timely, safe and efficient way from hospital

- enables people to access personalised information about their health and care – to give them more control over their own health and care journey – informed by excellent, timely data and integrated care records

- enables data and information sharing to support joined up and informed decisions around an individual’s care, and better understanding of the needs and priorities of local populations

- is delivered by a capable, confident, multidisciplinary workforce which wraps services around individuals and their families and carers

- allows and encourages innovation and digitisation to ensure that we have the right tools which enable people to have their needs met in the right place

- has joined up, workforce planning at the system level to ensure the right people, with the right skills and training to deliver collaborative, person-centred care

- incentivises organisations to prioritise the same shared outcomes and goals, so rather than a narrow focus on their own organisational targets, they can think about health and care journeys and outcomes, to ensure people don’t fall through gaps between services or settings, or bounce around the system

- incentivises organisations to collectively prioritise upstream interventions for individuals and communities, and increasingly allocate resource to improve population health and address disparities

- is driven forward by decisive leadership, who listen to and understand the needs of their local people and have clear accountability for delivering those outcomes

1.15. There is a widespread commitment to this agenda – we know health and care professionals and leaders want to do more to join up services. People want the services they use to be better joined up around their needs. Better integration can facilitate better care for people now, as well as in the long-term, as the importance of prevention grows.

1.16. Change is needed, and the potential reward – in better outcomes and value for citizens – is significant. Integration does not, of itself, guarantee improved outcomes – doing it well is what is required.

Our policies, interventions and the support we provide will therefore continue to promote the benefits of flexibility, local learning and the evolution of ways of working at place and system. The truly radical possibilities in this agenda are much more likely to be identified and realised by local organisations than through central prescription.

Case studies

Tom and Maureen

Tom is 85 years old and has mild undiagnosed dementia, he is currently living at home with his wife of 60 years, Maureen, who has been his constant support. The couple have lived in their home for 55 years. Maureen, who is of similar age to her husband, suffers with pain in her heart from angina and has high blood pressure. It is of increasing concern to their children, Dan and Sarah – who do not live locally, that the couple do not receive support from local services. Tom and Maureen are unaware of where to seek help as they are both unfamiliar with and lack confidence when using digital technology and feel like they are able to support themselves. Tom suffered from a fall down the stairs and fractured his hip.

Bunmi

Bunmi is a woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoarthritis and early dementia. She lives in sheltered accommodation and is moving around less than she usually would. Bunmi still tries to attend church every Sunday, however over the past few weeks she has been struggling to get out because of her worsening health and it is affecting her mood.

Kwame

Kwame is from the North East of England and has just celebrated his 18th birthday. Kwame loves to be outdoors and is a big fan of Star Wars. He also has a learning disability, autism and when anxious, he can display behaviour that can be particularly challenging to services.

Kwame has spent several years in an out of area residential, educational placement arranged by the local authority. This caused considerable increase in his anxiety and behaviours, placing himself, staff and other children at risk. This led to him spending more time in self-imposed seclusion. He was admitted for treatment at a specialist children’s hospital where he seriously assaulted a member of staff. To make the situation safer for people around him, Kwame’s interaction with family and staff was done through a glass pane and intercom system.

Madeleine

Madeleine is 65 years old and lives alone with her guide dog. She has been visually impaired since birth. She has 2 grown-up children and one grandchild all of whom live abroad. Good technology means that she is in contact with them on a daily basis but gets practical support from being involved in her local community. In common with most visually impaired people, Madeleine does not have any statutory support but relies on the services provided by Guide Dogs for the Blind Association.

Mandeep

Mandeep is a 24-year-old who struggles to maintain a job due to issues with his mental health. He had learning difficulties which were undiagnosed, resulting in his inability to gain a formal qualification. This affected Mandeep’s relationship with his family who did not understand why he was not achieving. Mandeep left home at 16 and stayed with friends or in supported accommodation when he could. He has type 2 diabetes and is often tired which has caused issues for him in the workplace. Mandeep is at risk of homelessness as he does not have a steady income and is unsure of where to go for help.

Richard

Richard has long-term schizophrenia. He has spent many years constantly bouncing in and out of long stay psychiatric inpatient admissions, but he wanted to live at home independently. After a recent relapse and hospital admission, the ward team identified that part of the reason for his psychotic relapse was that he was falling behind with rent payments and his house had damp and heating problems that he couldn’t fix. While the clinical team on the ward worked to stabilise Richard, including taking his medication, they also sought early input from local authority housing workers who work into the ward and could start on the paperwork to maintain Richard’s tenancy and arrange work to get the damp sorted.

2. Shared outcomes

Summary

Collaboration is essential to delivering joined-up care. Our frameworks should support organisations and systems to work together in pursuit of the same goals, which focus on individuals and population health and wellbeing.

It is right that the national government sets some delivery standards for organisations, to ensure that the public receive a consistent standard of care. But if we are to allow local leaders to work together to make the most of their shared resources on behalf of local people, we need to better support organisations to pull in the same direction.

Some outcomes and goals are appropriately set nationally, but we also need to make space for local leaders to agree shared outcomes that meet the particular needs of their communities. We need a new approach to setting shared priorities which is integrated and focuses on key outcomes which matter for people’s health and wellbeing and improve population health. Some local organisations will be focused on the delivery of outcomes relatively independently of other organisations; but to respond to increasing complexity and multi-morbidity, services should be free to support partner organisations, even when they are not the main delivery agent. For example, hospitals should be incentivised to support public health outcomes, and primary care should be incentivised to support social care outcomes.

Following further work with stakeholders, we will set out a framework with a focused set of national priorities and an approach from which places can develop additional local priorities.

Implementation of shared outcomes will begin from April 2023. In parallel, we will ensure that accompanying oversight arrangements and regulatory structures have a clear focus on the planning and delivery of these outcomes.

As part of the shared outcome setting process, we will review alignment with other priority setting exercises and outcomes frameworks across the health and social care system and those related to local government delivery.

Why shared outcomes matter

2.1. Shared outcomes bring organisations and the people they serve together, and shared outcomes with clear plans for delivery make impactful change happen. We have seen this in both the ICSs that have made the most progress in recent years and in the collaborative working during the pandemic. Priorities tend to be most effective when they are outcome-focused (rather than focusing on output or inputs), when they are specific, and when they reflect clearly the most important issues for local people. The right outcomes will encourage local innovation and positive change.

2.2. Currently, we have many and varied priorities and outcomes for the health and care system, used by different organisations for different purposes, albeit with some areas of overlap and alignment. There are outcomes frameworks for each of public health, the NHS and adult social care, as well as outcomes for local government more broadly. In parallel, priorities have been set in the NHS Long Term Plan and in the government’s mandate to NHS England. Organisational priorities are also shaped by the broader regulatory framework and by statutory duties.

2.3. In recent years we have seen systems and local partnerships working together to deliver shared outcomes and we need our national frameworks to reflect the increasing importance of collaboration in pursuit of joined-up care for local people. Whilst acknowledging the varying roles the current outcomes do serve across the system, it is important that they do not pull local leaders away from collaboration, but rather enable partner organisations to work together to deliver against outcomes that truly matter to the people they serve.

2.4. As we increase our expectations of integrated working at system and place, it is right that we revisit how outcomes are articulated and prioritised- nationally and locally – to ensure that we are doing all we can to support the achievement of greater integration. This will be vital if we are to achieve a decisive shift to a model focused on population health and delivered through a shared understanding of population need and what can be done to improve services. Outcome frameworks, prioritisation exercises and associated processes designed for one or more organisation- or sector-specific purposes will need greater alignment if we want to go further and faster on integration.

2.5. What counts as a good outcome will, in many cases, require much closer working with people who use health and care services. This should result in people having more control in decision-making about what matters in their individual lives. This is perhaps more developed in social care than in health care, and it is becoming an increasingly important element of effective support for people with multiple conditions. In defining shared outcomes, success will therefore be reflective of what individuals want for their own care and what will maximise their wellbeing, focused not only on an individual organisation’s services but also the connections between organisations and services they provide.

2.6. A new approach to shared outcomes will ensure that organisations can work together, focusing on shared goals which improve outcomes for people and populations, and underpinned by measures which support this aim. Following publication, we will work with stakeholders to set out national priorities and a broader framework for local outcome prioritisation for implementation from April 2023.

Design principles for a shared outcomes framework

2.7. Generally, places are best placed to prioritise the outcomes for local people that matter the most.

2.8. Shared outcomes will need to be designed by partners across the system and with citizens, grounded in shared insight and understanding of the needs of the population.

2.9. Integration of services and ambition in improving outcomes go hand in hand. Where there is strong alignment, trust and common purpose between partner organisations, accompanied by a strong local role in identifying priorities, we expect to see high levels of ambition in the outcomes which places identify.

2.10. An approach for agreeing local outcomes will be an essential part of the shared outcomes framework. Some national priorities will, of course, always be needed to secure the improvements in care and outcomes that the public expect – such as those to support elective recovery and hospital discharge to ensure people receive the right care in the right place at the right time. To this end, the government will continue to set a mandate for NHS England. We intend to set out a small and focused set of national priorities, which all places will be expected to deliver alongside their own local priorities. Local and national prioritisation and goal-setting processes should therefore be complementary and realistic. Central government will need to ensure that the priorities set at national level allow sufficient space for local prioritisation in pursuit of the needs of their local populations.

2.11. Outcomes will sit alongside – and complement – systems’ and organisations’ statutory responsibilities and wider regulatory frameworks, and our intention is to address the problem of organisations being pulled in different directions by competing outcomes and targets.

2.12. There is also an important national role in ensuring that national and local outcomes work and sit together coherently such that there is clarity and consistency, and so that local organisations and partnerships are able to consider their own progress in comparison with others.

2.13. We do not intend that shared outcomes should add to the overall burden of national requirements. In defining national outcomes, we will consider what can be aligned or replaced from our current priority and outcome setting exercises and frameworks.

2.14. We want to focus on outcomes rather than outputs. Although outcomes are harder to measure and can take longer to deliver, they offer the best prospect of decisions and services which are both person-centred and improve population health over time. When outcomes are long term, we will need to identify interim or proxy metrics which demonstrate that organisations are collectively making progress towards them.

2.15. Our outcomes-centred approach must therefore be focused on the end goals of better person-centred health and care, improving population health and addressing disparities rather than on the process of integration per se. So, for example, outcomes should focus on areas such as people’s experience of care, wellbeing, and independence, not on organisational processes or decision-making. Further illustrative examples of outcomes are provided below.

2.16. National bodies with a regulatory or oversight role will consider the setting and delivery of outcomes in discharging their regulatory duties.

Illustrative examples of shared outcomes

Mental health

A shared outcome for mental health could mean people with mental illness living well in the community. A shared set of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), could help align NHS clinical support with local authority support through social care, housing, and other services to improve recovery rates and quality of life for people living with mental illness.

Maternal smoking

Greater Manchester (GM) have taken a whole system approach to addressing smoking in pregnancy. Working collaboratively with foundation trusts, clinical commissioning groups, maternity services and across 10 local authorities. GM have implemented a financial incentives scheme, which enables women to access shopping vouchers at certain timepoints during pregnancy and beyond, conditional on them remaining smoke free. Outcomes from this integrated approach include an increase in the number of women successfully stopping smoking, higher average birth weight of babies and reductions in the number of babies requiring neonatal care.

Enhanced heath in care homes

Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) provides proactive care for care home residents and is delivered through a whole-system collaborative approach across health and care providers. Primary Care Networks must ensure that every care home has a named clinical lead, receives a weekly home round, and is supported by a multi-disciplinary team, and that every care home resident has a personalised care and support plan within 7 working days of admittance or readmittance. It involves a range of partners, including those from health (both primary and community care services), social care, voluntary, community, and social enterprise (VCSE) sector, as well as care homes, who are expected to work collaboratively with care homes to improve their local models over time.

As part of the care model, there are various shared outcomes which these providers are trying to achieve including:

a. high-quality personalised care within care homes

b. access to the right care and the right health services in the place of their choosing

c. reducing unnecessary conveyances to hospitals, hospital admissions, and bed days while ensuring the best care for people living in care home

Hospital discharge

Discharging people from hospital is an activity that needs acute, community, primary care and adult social care to work together. A shared outcome around discharge could bring together a group of outcomes in various existing frameworks to look beyond discharge to ‘right care, right place’.

What we will do

2.17 The government will undertake further engagement with partners and stakeholders and use these discussions to set a focused set of national outcomes alongside a broader framework for local outcome priorities. Initially, outcomes will focus on health services, the public’s health and adult social care. National and regional partners will play a key role in setting coordinated and consistent strategies to enable all organisations within the wider health and care landscape to align their activity to these national and local outcomes.

2.18 Places, working with local people and communities, will then identify and agree their local outcome priorities with reference to the broad framework. Places will agree action required to meet national and locally identified priorities.

2.19 ICSs will provide support and challenge to each local area as to the assessment of need and local outcome selection and plans to meet both national and local outcomes. Plans should be in place for implementation from April 2023.

2.20 We expect local arrangements, and the ICSs they are within, to take the lead on identifying issues and barriers to delivery and bring about real change for citizens. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) will consider outcomes agreed at place level as part of its assessment of ICSs. The CQC will also continue to develop its assessment of individual providers, to ensure their contribution to plans that improve outcomes at place and ICS level are assessed as part of the overall oversight framework.

2.21 These will build on existing oversight arrangements, some of which we are aiming to strengthen through the Health and Care Bill. The CQC will play a critical role. In addition to its current role in regulating and inspecting health and care providers, the CQC will review ICSs including NHS care, public health, and adult social care and assess local authorities’ delivery of their adult social care duties.

2.22 Working with partners, the CQC will consider both the starting position for each ICB and local authority, and the local and national priorities each area needs to manage, to help understand how all those responsible for health and care services are working together to deliver safe, high quality and integrated care for the public. Further work is underway to develop the detail and methodology of the CQC reviews, in line with existing oversight and support processes.

We will engage with partners and stakeholders to effectively design and implement shared outcomes. We will invite views on the following questions:

- Are there examples where shared outcomes have successfully created or strengthened common purpose between partners within a place or system?

- How can we get the balance right between local and national in setting outcomes and priorities?

- How can we most effectively balance the need for information about progress (often addressed through process indicators) with a focus on achieving outcomes (which are usually measured and demonstrated over a longer timeframe)?

- How should outcomes be best articulated to encourage closer working between the NHS and local government?

- How can partners most effectively balance shared goals or outcomes with those that are specific to one or the other partner – are there examples, and how can those who are setting national and local goals be most helpful?

3. Leadership, accountability and finance

Summary

Leaders are essential for bringing partners together to deliver outcomes that really matter to people and populations.

We will empower effective leaders at place level to deliver the shared outcomes that matter for their populations by setting an expectation that by spring 2023, all places within an ICS should adopt a model of accountability, with a clearly identified person responsible for delivering outcomes, working to ensure agreement between partners and providing clarity over decision making.

We will also work with the CQC and others to ensure there is effective regulation and oversight and that these new models achieve their purposes. CQC reviews will consider both how services deliver safe, high quality and integrated care to the public and the strength of integration within an ICS.

We will develop a national leadership programme, addressing the skills required to deliver effective system transformation and local partnerships, subject to the outcomes of the upcoming leadership review.

We want to build on progress in recent years to go further and faster in pooling and aligning funding to enable delivery at place level. Our expectation is that aligned financial arrangements and pooled budgets will become more widespread and grow to support more integrated models of service delivery, eventually covering much of funding for health and social care services at place level. These should be supported by robust frameworks to manage risk and deliver value for money.

To support this, we are reviewing section 75 of the NHS Act 2006 (which allows partners such as NHS bodies and councils to pool and align budgets) to simplify and update the underlying regulations.

Finally, we are reaffirming our commitment to personal health budgets, personal budgets, and integrated personal budgets as a means for supporting integration around individual patients and people who draw on care services.

3.1 Leaders are essential for bringing partners together to deliver outcomes that really matter to people and populations.

3.2 There are many great leaders in health and care across places in England who have made incredible progress to integrate health and care services and to join up care to improve outcomes for their populations.

3.3 At place level, this is especially important. Local leaders – including clinical and professional leaders – are well placed to understand the health and care needs of their local populations and to deliver the right change to level up health and care outcomes.

3.4 Effective local leaders are responsible – and seen to be responsible – for delivering the right outcomes and value for money, tackling health disparities, and for how well they have brought together the relevant partners to do so. We need to create the conditions to make this the norm in all places.

3.5 Many leaders, however, find that significant effort, persistence and resources are required to achieve the levels of collaboration and integration that match their ambitions and commitment. In particular:

- financial flows, priorities set nationally, and regulations can pull organisations away from shared goals

- managing complexity and a multitude of relevant actors can make partnership working difficult to do

- a reliance on relationships and ‘soft’ levers can work well in areas where there are strong relationships built over time, but lacks resilience as it is vulnerable to change in leadership, and is not universal

- support and incentives for leaders often focus on developing effective leaders for individual organisations within their siloes, rather than effective leadership of partnerships

Developing effective leadership for integration

3.6 The Health and Social Care Leadership Review will look to improve processes and strengthen the leadership of health and social care in England. It will consider how to foster and replicate the best examples of leadership and will aim to reduce regional disparities in efficiency and health outcomes. The review will report to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care in early 2022 and will be followed by a delivery plan with clear timelines on implementing agreed recommendations.

3.7 Without pre-empting that review, we believe effective local leaders for health and care should:

- bring their partners together around a common agenda with decisive action in the interest of local people, even when it runs counter to organisational interests

- be able to judge when it is right to remove or challenge organisational boundaries and when it is better to make connections between distinct organisations

- be responsible for delivering outcomes, ensuring data is used and shared safely and effectively, to provide shared insight and a holistic understanding of the health and care needs of their local population

- focus decisions both on what happens at the point of care, and on what is of most benefit from a population perspective – taking a strong interest in what delivers value for money over time

- listen to the voices of people who draw – or may need to draw – on services when designing and improving those services and in defining which outcomes matter to individuals and populations

- support and enable clinical and adult social care leadership in the development and delivery of services

3.8 Again, subject to the recommendations of the leadership review, we will also look to develop a national leadership programme, addressing the skills required to deliver effective system transformation and local partnerships. This programme will also help to build locally the relationships and shared mission that we know is so important to successful integration.

Clear accountability

3.9 Effective integration and local prioritisation require both a strong, shared sense of purpose and clarity of accountability at place level, so everyone is clear who is responsible for delivering what, with which levers and what budgets. This has been demonstrated time and again in local places and wider health and care systems with a strong track record on integration.

3.10 All areas should ensure there is excellent value, good outcomes and improved experience for people. However, the specific areas for action will differ from place to place, as will the accountability arrangements that work best; as is already the case in the most successful places and systems. We therefore have not prescribed either. We do, however, want to ensure the benefits of integrated care are experienced in all places and as soon as possible, and to that end will set out criteria for local governance and accountability for the delivery of shared outcomes. We have suggested a model which meets those criteria.

3.11 Success will depend on making rapid progress towards clarity of governance and clarity of scope in place-based arrangements. We are therefore setting the expectation that, by spring 2023, all places within an ICS should adopt either a governance model as outlined below, or an equivalent model which achieves the same aims. The characteristics we would expect a governance model to have are:

- a clear, shared, resourced plan across the partner organisations for delivery of services within scope and for improving shared local outcomes

- over time, a track record of delivery against agreed or shared outcomes

- a significant and, in many cases, growing proportion of health and care activity and spend within that place, overseen by and funded through, resources held by the place-based arrangement

3.12 We would also expect a governance model to provide clarity of decision-making covering:

- contentious issues such as reshaping services within the place (and contributions to wider decisions such as reconfigurations across a wider geography)

- clear, practical arrangements for managing risk, resolving disagreements between local partners, and for agreeing the outcomes to be pursued locally in addition to any set nationally, with strong involvement for the health and care provider organisations for that place

- a single person, accountable for the delivery of the shared plan and outcomes for the place, working with local partners (for example, an individual with a dual role across health and care or an individual lead for a ‘place board’ as outlined from paragraph 3.18). The single person will be agreed by the relevant local authority or authorities and ICB. This proposal will not change the current local democratic accountability or formal accountable officer duties within local authorities, those of the ICB Chief Executive or relevant national bodies, such as the ability of NHS England to exercise its functions and duties

3.13 These arrangements should, as a starting point, make use of existing structures and processes including Health and Wellbeing Boards and the Better Care Fund. They should also provide clarity about what is done at place and at system levels.

An accountability model and local innovation

3.14 We expect all local areas to put in place-based arrangements to bring together NHS and local authority leadership. This will include responsibility for effective commissioning and delivery of health and care services. Local health and care leaders set and agree the shared outcomes and will be held accountable for delivery of these outcomes.

3.15 Places will be able to decide which model they adopt, and we have outlined one illustrative model (the place board model) that is a good basis for delivering the characteristics described above.

3.16 This will build on ‘Thriving Places’, the joint Local Government Association (LGA)- NHS England (NHSE) guidance published in September 2021.

3.17 Places will be supported in this work by their ICSs and by an NHS England or local government support offer.

The place board model

3.18 In this arrangement, a ‘place board’ brings together partner organisations to pool resources, make decisions and plan jointly – with a single person accountable for the delivery of shared outcomes and plans, working with local partners. In this system the council and ICB would delegate their functions and budgets to the board. Integration of decision-making would be achieved through formal governance arrangements (likely to include definition of membership; responsibility for outcome-setting; responsibility for delivery of functions or programmes delegated; financial arrangements including pooling; and dispute resolution and decision-making). The place board lead would be agreed by the ICB and the local authority (or authorities) for the place.

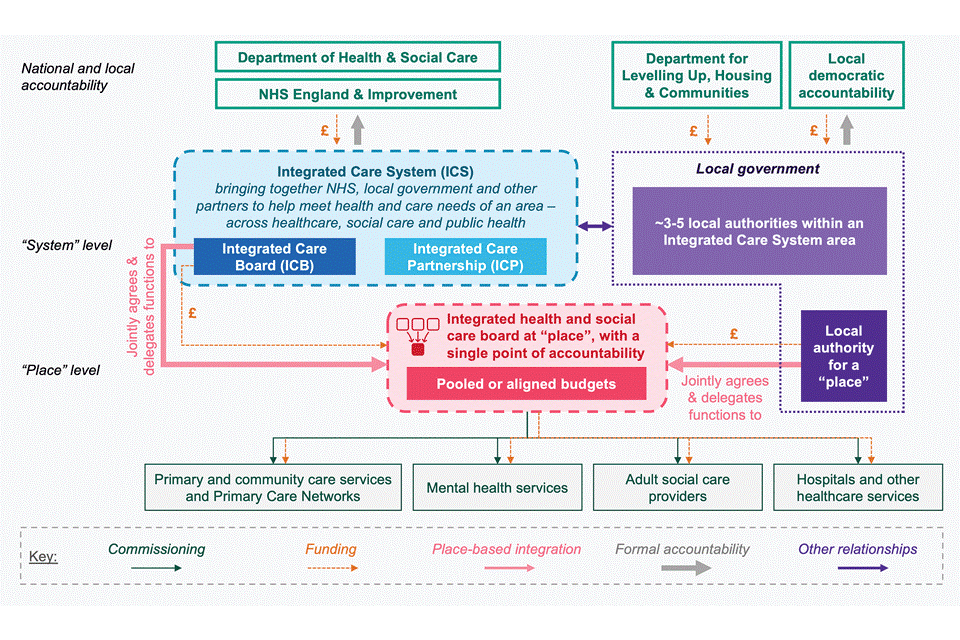

Note: This diagram this is a simplified example of potential governance arrangements and not a full representation of the richness, complexity and range of partnership working across the organisations within systems.

3.19 As the development of ICSs has shown, there is enormous potential within the health and care system to find innovative ways of managing and improving care, and we want to bring that same spirit to the development of places. We are likely to secure more value through setting challenges than through setting limits on that innovative potential. We would therefore stress that the model described here is simply a model, and not the only one. We believe it meets the criteria we have set out above, and so serves as a helpful illustration of what is needed; but the criteria are what really matter. Both places and ICSs vary in size, with some ICSs covering nearly 3 million people and others scaled to the same size as places within other systems. Strong systems and strong places complement and support each other; and this means that it will be important for all relevant partners to work together to agree suitable, proportionate, complementary governance arrangements at place and at system level. In the small number of cases where systems and places are effectively the same geography, we would not expect both place-based and ICS arrangements to be set up as that would be bureaucratic and unhelpful. There are no national plans for further changes to ICS boundaries.

3.20 In addition to clarity of governance, all places will need to develop ambitious plans for the scope of services and spend to be overseen by ‘place-based’ arrangements. From April 2023, arrangements for national and local shared outcomes will go live.

3.21 Those able to go further should do so by putting in place extensive inclusion of services and spend at a local level.

3.22 All local areas should work towards inclusion of services and spend by 2026. Of course, local partners would need to agree fairness in pooling arrangements set out at para 3.24 in working towards this goal.

Financial frameworks and incentives

3.23 Financial frameworks, like other critical enablers of integration such as leadership, workforce and digital are essential to realising our vision of integrated care. However, financial frameworks cannot and do not operate in isolation. They must align with and reinforce our wider strategic objectives and delivery approach, including regulatory, accountability, behavioural and organisational frameworks.

3.24 However, in practice, over the last decade, financial frameworks have often been cited as a barrier to the development and delivery of integrated approaches. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, given how different local systems are in terms of the populations they serve and the existing organisations they contain. However, this complexity is challenging to navigate, often requiring complex workarounds which make it hard to plan and share risk – this being critical to delivering integrated approaches. There are mechanisms that places can use to overcome this (for example, pooled budgets underpinned by legislation through section 75 of NHS Act 2006), but there is scope to simplify and update these mechanisms. In this document, we refer to both ‘pooling’ and ‘aligning’ of resources. Pooling requires a more formal agreement while aligning resources – which can include significant resource and collaboration – is less formal. We want to ensure there is flexibility to enable as much collaboration and integration as possible. In some cases, particularly as arrangements at place mature, it may well make sense to put in place more formal pooling arrangements, and we would expect the overall level of pooling to increase in the years ahead. Pooling agreements will remain subject to both NHS and local authority leadership and NHS system and place leaders agreeing what constitutes a fair and appropriate contribution. A clear sense of fairness for all partners is an important basis for integration and, as we have seen in the most effective systems and partnerships in recent years, a strong culture of trust and mutual accountability allows partners to then focus on the pursuit of shared outcomes.

3.25 We have recognised these challenges. Within the NHS, through the Health and Care Bill (subject to bill passage) we are seeking to enable different parts of the health and care system to work together as part of a move towards a whole population-based approach. This will be underpinned by a collective approach to managing resources, with ICSs as the primary unit for NHS financial planning and accountability, operating with a single system funding envelope across acute, ambulance, community, mental health and primary care (starting with general practice).

3.26 Subject to bill passage, these changes will be complemented by other measures such as Joint Committees, as well as a holistic set of statutory duties and oversight. For example, there is the Triple Aim duty which covers the health and wellbeing of people in England, the quality of services provided or arranged by both themselves and other relevant bodies (NHS England, trusts and foundation trusts, and ICBs), and the sustainable and efficient use of resources by both themselves and other relevant bodies. There are strengthened duties to cooperate, as well as clauses on system collaboration and financial management agreement in NHS standard contracts. We are also joining up services for individuals through expanding the use of personal health budgets (PHBs). The NHS Long Term Plan sets out the commitment to grant individuals more control over their own health, and more personalised care when they need it, through initiatives such as the national roll-out of the NHS’s comprehensive model for personalised care across the country and accelerating the roll-out of personal health budgets to give people greater choice and control over how care is planned and delivered (with up to 200,000 people benefiting from a PHB by 2023 to 2024).

3.27 Pooling of funding to support joint delivery of services is not new and we have established mechanisms for doing this (such as the Better Care Fund (BCF) and section 75 of the 2006 Act). Many areas already use these mechanisms to ensure that the right funding is in the right place to support the delivery of shared objectives with pragmatic mechanisms to manage financial risk. There are examples of systems using these to enable ambitious models of integration which involve pooling a significant proportion of their funding. However, there are also examples of bureaucracy and conflict which prevent pragmatic attempts to improve services. This is not in the interests of those receiving or providing care – local organisations have a shared responsibility to maximise the outcomes of patients, service users and value for the taxpayer.

3.28 Our proposals in the Health and Social Care Bill seek to simplify the governance mechanisms around these arrangements, making it easier for local organisations to collaborate. However, as set out above, we want to go further to drive progress. Our vision for integration, centred around individuals and local populations requires shared objectives, dynamic and collaborative leadership; alongside mechanisms to enable joint working (such as pooled or aligned budgets). When set up effectively, framed around people and service delivery, these are an important way of putting the public pound towards a shared purpose.

3.29 The current system allows a lot of ambition using pooled budgets, but it largely relies on local leadership to drive this. Since 2015, through the BCF, local NHS commissioners (CCGs) have pooled a proportion of their allocations, alongside funding from local government to enable the delivery of joint plans to support person-centred integrated care. The 2019 review of the BCF concluded that it had been effective in incentivising areas to work more effectively, with over 90% of areas saying that the BCF had improved joint working in their locality consistently since 2017,[footnote 3] and that any attempt to remove or dismantle a pooled budget scheme would be a clear backward step on integration. Moreover, places have voluntarily pooled increasing amounts of money into the BCF year-on-year. In 2020 to 2021, voluntary contributions totalled £3 billion above the nationally mandated minimum, double the figure in 2015 to 2016. This represents significant progress and demonstrates what can be achieved through a framework with an element of national requirements and scope for local partners to go further. Later this year we will set out the policy framework for the BCF from 2023, including how the programme will support implementation of the new approach to integration at place level.

3.30 Despite this, we know that local systems say the arrangements to pool budgets can be complex and there are limitations which prevent the most ambitious models of integration. To address this, we will review the legislation covering pooled budgets (section 75a of the 2006 Act) and publish revised guidance. As indicated above, this will continue to be subject to both NHS and local authority partners agreeing locally what constitutes fair.

3.31 Local organisations must, of course, demonstrate careful consideration of value for money and use available funding in line with their respective accountabilities and delegations. Our vision is that this can, and should, also serve shared objectives and secure wider value. Wherever possible, pooled or aligned budgets should be routine and grow to support more integrated models of service delivery, eventually covering much of funding for health and social care services at place level.

3.32 Some systems are already doing this, and it needs to become the norm along with shared objectives and shared delivery plans to improve outcomes for patients and those who use care services. In line with our wider approach, we will not at this point mandate how this is achieved, but our expectation is that funding should be pooled and aligned around pathways where the case for joined up care is most pressing. As progress accelerates, we will need to carefully consider the implications for existing mechanisms, including the BCF.

3.33 We will also build on the roll-out of personal budgets and personal health budgets across health and social care. The overarching aim is an outcomes-based approach to provide patients and people who draw on social care and support with greater flexibility, choice and control over their care that enables services to be tailored to their particular health and care needs.

3.34 Integrated budgets support integration at an individual level by ensuring support is holistic and can improve a range of health, social care, work and education outcomes for people. Alongside reaffirming our commitment to personal health budgets and personal budgets we will continue to identify opportunities to promote the roll-out by supporting places with guidance and sharing best practice.

Oversight and support

3.35 The Health and Care Bill, if passed into law, places a new duty on the CQC to review ICSs as a whole. This will help inform the public about the quality of health and care in their area and review progress against our aspirations for delivering better, more joined up care across ICSs. These reviews are required to look at how system partners are working together to deliver care. The use of resources will be a running theme in the different reviews and assessments, along with delivery against shared outcomes. The CQC will consider outcomes agreed at place level as part of its assessment of ICSs. CQC will also continue to develop its assessment of individual providers, to ensure their contribution to plans that improve outcomes at Place and ICS level are assessed as part of the overall oversight framework.

3.36 Working with partners, the CQC will consider both the starting position for each ICS and local authority, and the local and national priorities each area needs to manage to help understand how all those responsible for health and care services are working together to deliver safe, high quality and integrated care to the public. Further work is underway to develop the detail and methodology of the CQC reviews. This work will be complementary to existing oversight and support processes (including those used by NHS England to support ICSs, and sector led improvement in local government).

3.37 We will also work with others to ensure that local authorities also receive appropriate support to play their part in place-based arrangements.

To ensure these proposals on accountability, financial frameworks and oversight will be implemented effectively, we will engage with stakeholders and partners, inviting views on the following questions:

- How can the approach to accountability set out in this paper be most effectively implemented? Are there current models in use that meet the criteria set out that could be helpfully shared?

- What will be the key challenges in implementing the approach to accountability set out in the paper? How can they be most effectively met?

- How can we improve sharing of best practice regarding pooled or aligned budgets?

- What guidance would be helpful in enabling local partners to develop simplified and proportionate pooled or aligned budgets?

- What examples are there of effective pooling or alignment of resources to integrate care or work to improve outcomes? What were the critical success factors?

- What features of the current pooling regime (section 75) could be improved and how? Are there any barriers, regulatory or bureaucratic, that would need to be addressed?

4. Digital and data

Summary

Joining up data and information is central to integrating services. All citizens should expect to have access to their own shared care record and for it to cover their health and care journey, with full access, where appropriate, for all the staff they come into contact with.

Health and adult social care providers within an ICS must reach a minimum level of digital maturity, and these providers should be connected to a shared care record. This will ensure each ICS has a functional and single health and adult social care record for each citizen by 2024, with work underway to enable full access for the person, their approved caregivers and care team to view and contribute to. A suite of standards for adult social care, co-designed with the sector, will enable providers across the NHS and adult social care sector to share information. This will begin with the consolidation of existing terminology standards by December 2022. Data to support an understanding of population health, including unmet need and disparities, should be fully shared across NHS and local authority organisations, to allow ‘place boards’ or equivalents, and ICSs to plan, commission and deliver shared outcomes, including public health and prevention services.

Each ICS will implement a population health platform with care coordination functionality that uses joined up data to support planning, proactive population health management and precision public health by 2025.

Digital integration will open up new ways for individuals to access health and adult social care services. There has been rapid expansion of digital channels in primary and secondary care services, but there is more we can do to ensure individuals can choose how they interact with services. By 2022, one million people will be supported by digitally enabled care pathways at home.