6. Gender Spotlight

Updated 18 November 2021

Applies to England

Introduction

This Spotlight is part of a series within the COVID-19: mental health and wellbeing surveillance report. The report is about population mental health and wellbeing in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. It includes up to date information to inform policy, planning and commissioning in health and social care. It is designed to assist stakeholders at national and local level, in both government and non-government sectors.

The report is regularly updated with the most recent information available, and follows a standard structure to enable regular and easy use.

The Spotlight series describes variation and inequality in the population. Spotlights have also been published for age,ethnicity and pre-existing mental health conditions.

This Spotlight presents intelligence on potential inequalities by gender. Evidence of different mental health and wellbeing experiences are presented for people grouped according to their self-identification as male or female. So far, data has not enabled a more nuanced approach to gender, for example an analysis of the experience of adults who identify as a different gender to the one they were assigned at birth or of people whose experience of gender is more fluid. Any analysis of this will be included in the surveillance report once it is publicly available.

This Spotlight is composed of 2 main categories of information:

- Weekly data drawn from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study up to week 38 of 2020 (week ending 18 September).

- Analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects up to week 36 of 2020 (week ending 4 September).

The 2 categories of information have separate purposes.

Weekly data serves as an early warning system for large changes and differences between groups. It should not be used to draw conclusions about smaller changes or differences between groups from week to week. This is because the data has not been analysed to control for any confounding factors or potential biases.

The analysis from academic research offers a more precise picture of change over time and differences between groups. This intelligence is the basis for more nuanced interpretation and feeds into the Important findings chapter.

The latest available version of the data presented in this spotlight can be found in the Wider Impacts of COVID-19 on Health (WICH) tool.

Note:

Any deterioration of mental health captured in studies and weekly reporting should not be automatically interpreted as an increase in mental illness or need for mental health services. This is a difficult and stressful time for many, and some increases in psychological distress and anxiety are to be expected.

Note:

To enable this Spotlight to be as up to date as possible some pre-print (and therefore not yet peer reviewed) academic research is presented. Even with this approach there is still a time delay between data being gathered and findings reported.

Note:

The UCL COVID-19 Social Study focuses on the psychological and social experiences of adults living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study is not representative of the UK population but instead was designed to have good stratification across a wide range of socio-demographic factors with data weighted to the national population.

This study sample was refreshed in late August and around 16,000 participants who had stopped submitting data routinely re-engaged. The study also changed from weekly to monthly follow up with participants allocated to one of 4 weeks.

The impact of these changes is not yet fully understood, therefore reporting of data from the point of change is indicated by a dashed line. Early interpretation of this data should be undertaken with caution. It is also important to note that some of the baseline levels for the UCL COVID-19 Social Study graphs use data from other countries and therefore may not be wholly representative of UK pre-COVID-19 levels.

The basis for the intelligence included is presented in the Methodology document.

Graphs tracking gender inequality in the population

The graphs in this section are based on weekly data, and are included as an early warning system for large changes and differences between groups.

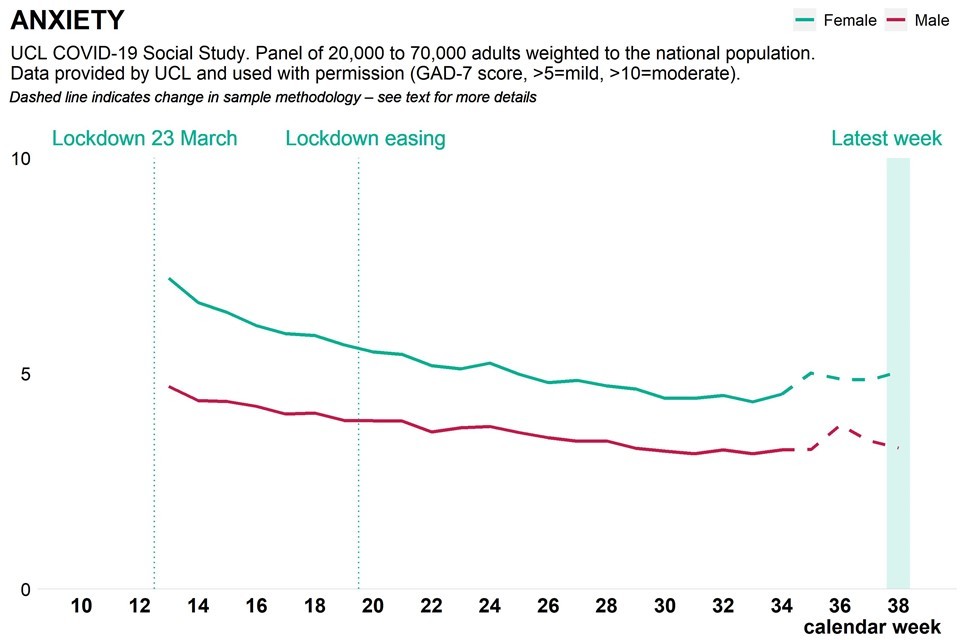

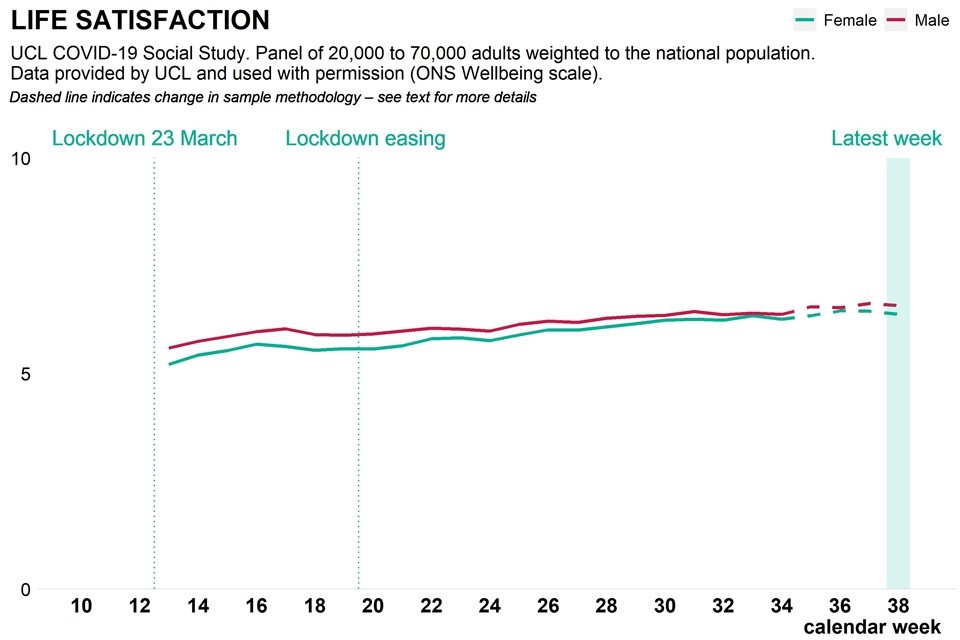

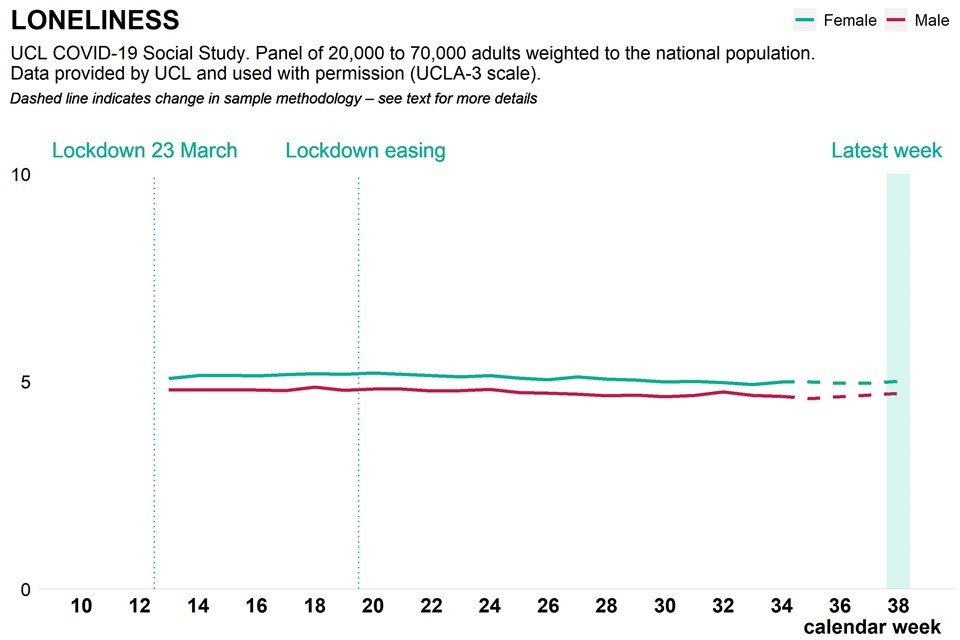

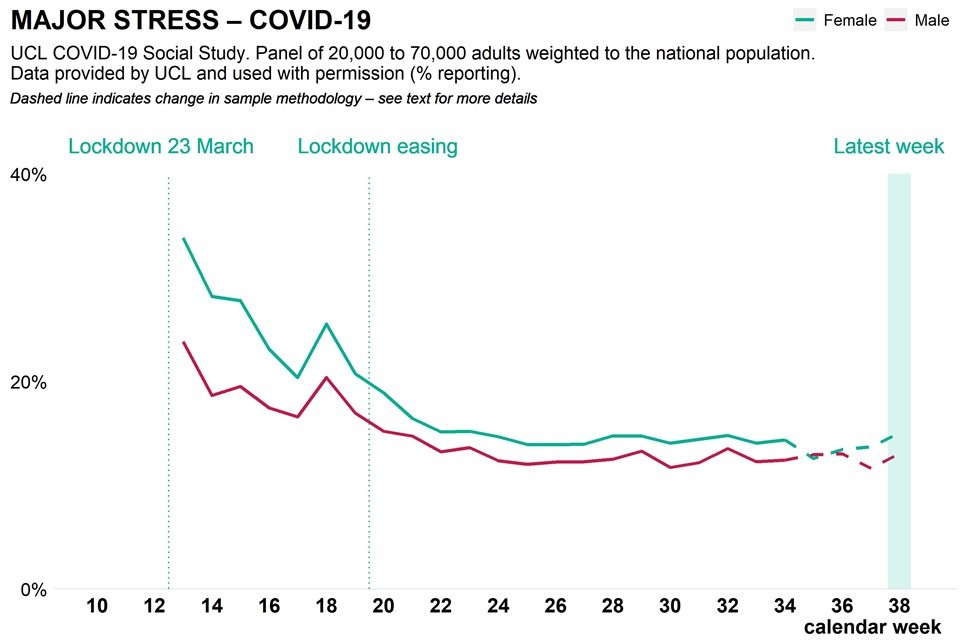

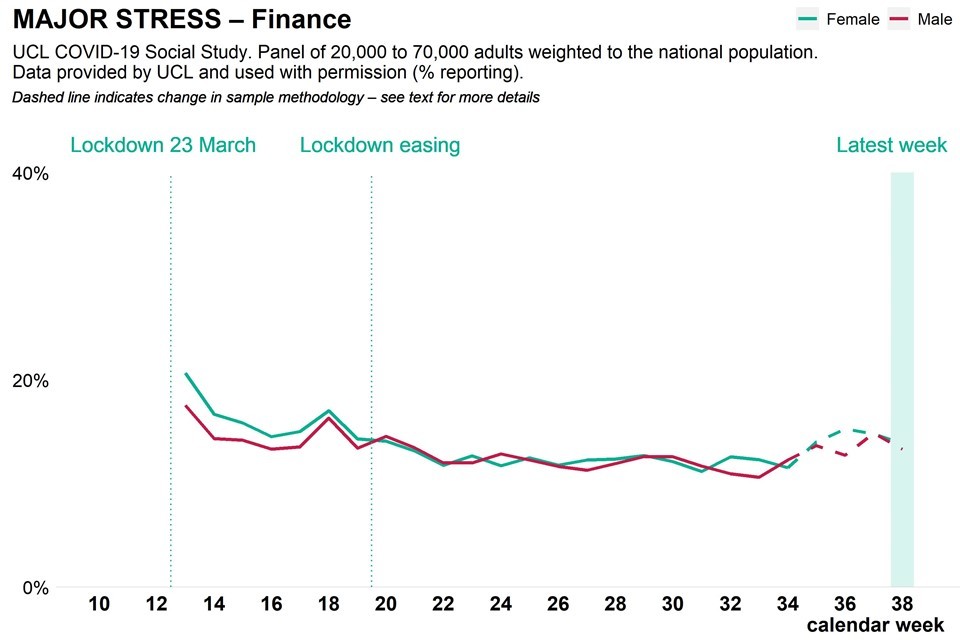

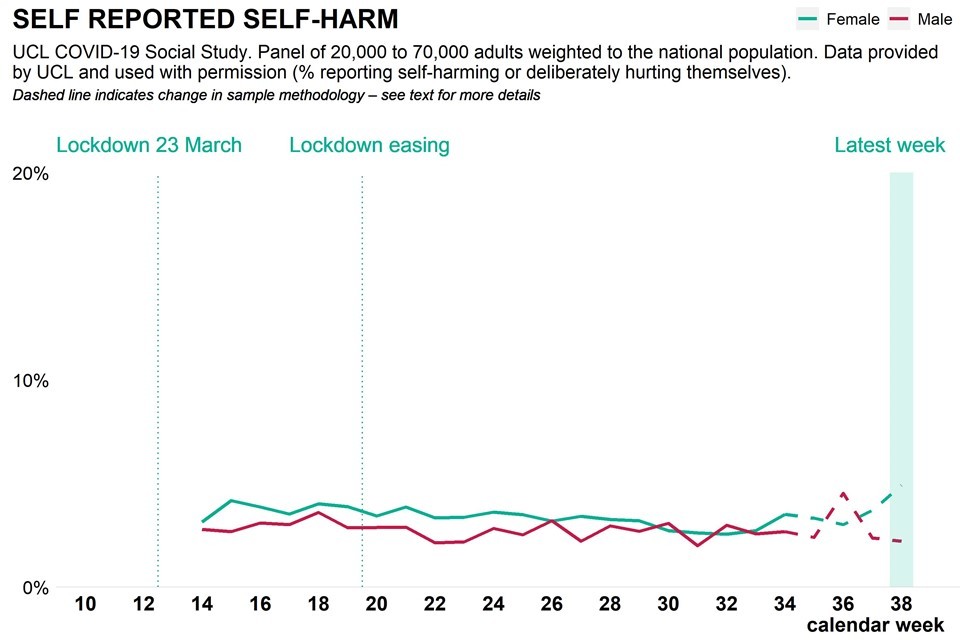

The figures below are taken from UCL COVID-19 Social Study. Most show that women tend to report worse mental health and wellbeing during the pandemic than men. These differences may have narrowed over the weeks since lockdown. However, there is no obvious difference between women and men for reporting of finance-related stress, thoughts of death or self-harm and self-reported self-harm.

Reported decreases in average scores for anxiety and depression, and increase in average life satisfaction scores since lockdown suggest some improvement in mental health and wellbeing for both women and men. It is too soon to draw any conclusions about possible changes in average levels seen for some of these measures over recent weeks.

Up-to-date data is available on the WICH tool.

Graph showing population anxiety measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population depression measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population life satisfaction as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population loneliness as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population Covid related stress as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population finance related stress as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population reported thoughts of self harm as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Graph showing population reported actual self harm as weekly time trend over pandemic, broken down by gender

Analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects

The analysis in this section is based on ongoing academic research, and is included to inform a more precise picture of change over time and differences between groups.

Is there evidence of variation in mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic by gender?

The following is based on findings from multiple longitudinal cohort studies which are presented in the sections below. The summary statements are:

-

post pandemic self reporting of mental health and wellbeing showed a deterioration among both women and men when compared to pre pandemic levels

-

since April 2020 women have reported worse mental health and wellbeing than men, however this was also true before the pandemic

-

the initial deterioration in mental health measured at the start of lockdown was greater for women than men

-

some evidence suggests the initial deterioration has been followed by a period of greater improvement in mental health and wellbeing for women than men

-

reported gender differences in mental health and wellbeing may apply to the White British population only

What happened to the mental health and wellbeing of women and men early on during the pandemic?

Both men and women reported a deterioration in mental health and wellbeing during the early lockdown. This deterioration was greater among women and self reported mental health problems were more common and on average more severe among women.

Main findings include:

-

in April and May 2020 women and men were more likely to report higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, psychological distress and sleep loss than before the pandemic, and levels were more likely to be higher among women than men (references 1-7)

-

one study found no evidence of a difference in the prevalence of depression between women and men in April 2020 (contrary to some studies referenced in the above point), but that men were more likely to report high levels of stress

-

in April 2020 the reported frequency of being a victim of abuse, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm was higher among women than men

-

during April and May 2020 women were more likely than men to report feeling lonely, and for that loneliness to be increasing over time (references 9-11)

-

in May 2020 women were more likely than men to report higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety and loneliness in 4 different age cohorts (19, 30, 50, and 62 years), but both rates and the difference decreased with age

Was the early impact of the pandemic and the lockdown greater for women or men?

To understand variation in the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing by gender, it is important to understand variation before the pandemic.

Evidence from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey suggests that there was variation in the population’s mental health by gender before the pandemic. In 2014, 1 in 5 women (19.1%) reported symptoms of common mental disorders, compared with 1 in 8 men (12.2%). Women were also more likely than men to report severe symptoms (9.8% of women, compared with 6.4% of men). Comparisons with APMS surveys conducted since 1993 suggest that these differences may be increasing over time.

Bearing in mind evidence of variation before the pandemic, there is now evidence that women experienced a larger deterioration in mental health and wellbeing than men in April and May 2020. Multiple studies using data from the same cohorts of people surveyed before and during the pandemic help to provide this evidence. These studies find that:

-

the estimated levels of psychological distress (measured using GHQ-12) among adults increased from 24.3% between 2017 and 2019 to 37.8% in April, and the increase was 6.9 percentage points greater among women than men

-

women reported worse mental health than men before and during the lockdown as well as larger increases in psychological distress between 2017 and 2019 and April 2020 (references 12, 14)

-

comparing psychological distress scores among individuals, after adjusting for time-trends and predictors, increases between 2017 and 2019 and April 2020 were particularly large for women (0.9 points on GHQ-12 scale, compared to 0.5 among the general population)

-

between 2017 and 2019 and April 2020 average GHQ-12 scores among women aged 16 to 24 years rose by 2.5 percentage points more than predicted had there been no pandemic, and the percentage of young women reporting a severe problem doubled from 17.6% to 35.2%

-

an analysis of 3 age cohorts (ages 30, 50 and 62) found that a higher proportion of those aged 30 reported psychological distress during lockdown than when previously assessed, and the increase was more pronounced among women

There is evidence that family and caring responsibilities as well as social factors may have played a role in this observed difference in impact between genders. Women were more likely to have made larger adjustments to manage housework and childcare during the lockdown than men, and there is evidence of an association between these adjustments and psychological distress (references 17-18)

Adults living with children have been more likely to report worse mental health than adults living without children since the onset of the pandemic – lone mothers may be particularly vulnerable.

Women also reported (PDF, 5.1MB) having more close friends than men, and a larger increase in loneliness subsequently during the lockdown.

What has happened to the mental health and wellbeing of women and men since May 2020?

Findings from longitudinal cohort studies are beginning to provide evidence of change in mental health and wellbeing since the lifting of the first lockdown restrictions. Initial findings include:

-

after rising to 37.8% in April 2020, the prevalence of psychological distress among adults dropped to 34.7% in May and 31.9% in June, with particularly large decreases in distress observed among women (although not back to pre pandemic levels or to the levels reported by men)

-

compared to April 2020, by August the levels of anxiety and depression reported by women and men had decreased and the difference between them had narrowed

Controlling for ethnicity

Early evidence about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and wellbeing by ethnicity suggests that on average, Bangladeshi, Indian, Pakistani and White British men have all reported significant declines in mental health. Also, Pakistani and Bangladeshi men have reported larger declines than White British men.

Among women, there was no evidence of a difference in mental health decline across ethnic groups. Further, among Black, Asian and minority ethnic adults, there was no evidence of a difference in mental health decline by gender. This suggests that the gender gap, with a larger deterioration in mental health among women than men reported across a number of studies, is a phenomenon mostly seen within the White British population (references 21-22)

It is important to note that the sample sizes for minority ethnicity respondents in these studies are relatively small. This makes the estimates less precise. In addition, ethnicity and gender may be correlated with other factors including income, employment as a key worker and family or caring responsibilities that may cause a difference. It remains difficult to draw conclusions about ethnicity, interactions with gender and mental health during the pandemic.

Variation by ethnicity is covered in more detail in the Ethnicity Spotlight.

In summary

There appears to be an underlying relationship between gender and the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing. Women reported worse symptoms and a larger deterioration in mental health after the onset of the pandemic than men.

There is evidence of faster recovery among women than men in May and June 2020, but not yet back to pre-pandemic levels, or to the levels reported by men.

With respect to psychological distress, these gender differences appear to only apply to White British adults. There is less evidence of variation in psychological distress between women and men among non-White British adults.

References

-

Burchell B, Wang S. Cut hours, not people: No work, furlough, short hours and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.:23

-

Proto E, Quintana-Domeque C. COVID-19 and Mental Health Deterioration among BAME Groups in the UK. 2020;56. (PDF, 1.45MB)