3. Employment and income Spotlight

Updated 18 November 2021

Applies to England

Introduction

This Spotlight is part of a series within the COVID-19: mental health and wellbeing surveillance report.

The Spotlight series describes variation and inequality in the population. Spotlights have also been published for age, gender, ethnicity and the experience of people with pre-existing mental health conditions.

This Spotlight is composed of 2 main categories of information:

-

weekly data drawn from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study up to week 4 of 2021 (25 January)

-

analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects made publicly available by week 1 of 2021 (6 January)

The 2 categories of information have separate purposes.

Weekly data serves as an early warning system for potentially large changes and differences between groups. It should not be used to draw conclusions about smaller changes or differences between groups from week to week. This is because the data has not been analysed to control for any confounding factors or potential biases.

The analysis from academic research offers a good picture of change over time and differences between groups. This intelligence is the basis for more nuanced interpretation and also feeds into the Important Findings chapter.

The latest available version of the data presented in this spotlight can be found in the Wider Impacts of COVID-19 on Health (WICH) tool.

Note:

These data do not reflect changes in financial status over the course of the pandemic, for example due to redundancy or furlough.

Note:

Any deterioration of mental health captured in studies and weekly reporting should not be automatically interpreted as an increase in mental illness or need for mental health services. This is a difficult and stressful time for many, and some short-term increases in psychological distress and anxiety are to be expected.

Note:

To enable this Spotlight to be as up to date as possible, some pre-print (and therefore not yet peer reviewed) academic research is presented. Even with this approach there is still a time delay between data being gathered and findings reported.

Note:

The UCL COVID-19 Social Study focuses on the psychological and social experiences of adults living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. This self-selected study sample is not representative of the UK population though was designed to have good stratification across a wide range of socio-demographic factors. Results were weighted to the national population.

It is also important to note that some of the baseline levels for the UCL COVID-19 social study graphs use data from other countries and therefore may not be wholly representative of UK pre-COVID-19 levels.

The basis for the intelligence included is presented in the Methodology document.

Main findings

The relationship between mental health and income or employment is complex and can work in either direction. Long periods of unemployment can stimulate a deterioration in mental health. Similarly, periods of mental ill health can make finding and retaining employment more difficult, and mental disorder is an important reason of why people are on low income.

During the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

unemployed adults and adults with lower incomes have reported higher levels of psychological distress, anxiety, depression and loneliness than adults with higher incomes

-

however, there is not evidence that this gap has changed since before the pandemic; all income groups as well as adults with and without employment reported an initial deterioration in mental health and wellbeing in April 2020, followed by a period of recovery

-

some groups of employed adults have reported larger deteriorations in mental health and wellbeing than others, such as those who are self-employed or work for small companies

-

loss of income and employment has been associated with worsening mental health, even after household income is considered

-

on average, any connection to a job or income is better than none for good mental health and wellbeing, even if reduced compared to before the pandemic

Graphs tracking mental health and wellbeing in the population by income

Adults participating in the UCL COVID-19 Social Study are asked about their annual income. They were asked to select from 6 grouped categories, ranging from ‘less than £16,000 per year’ to ‘more than £120,000 per year’.

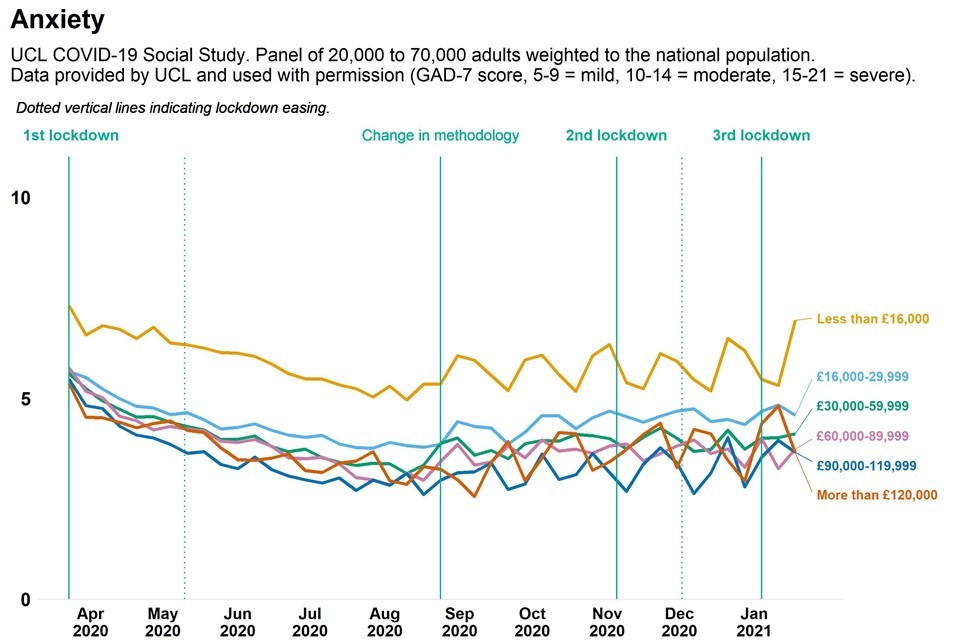

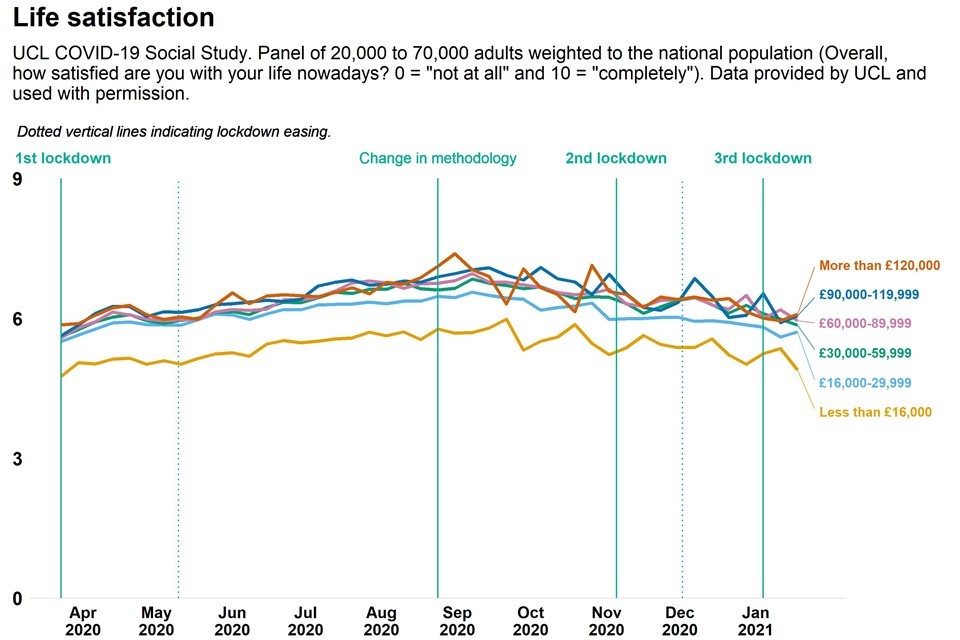

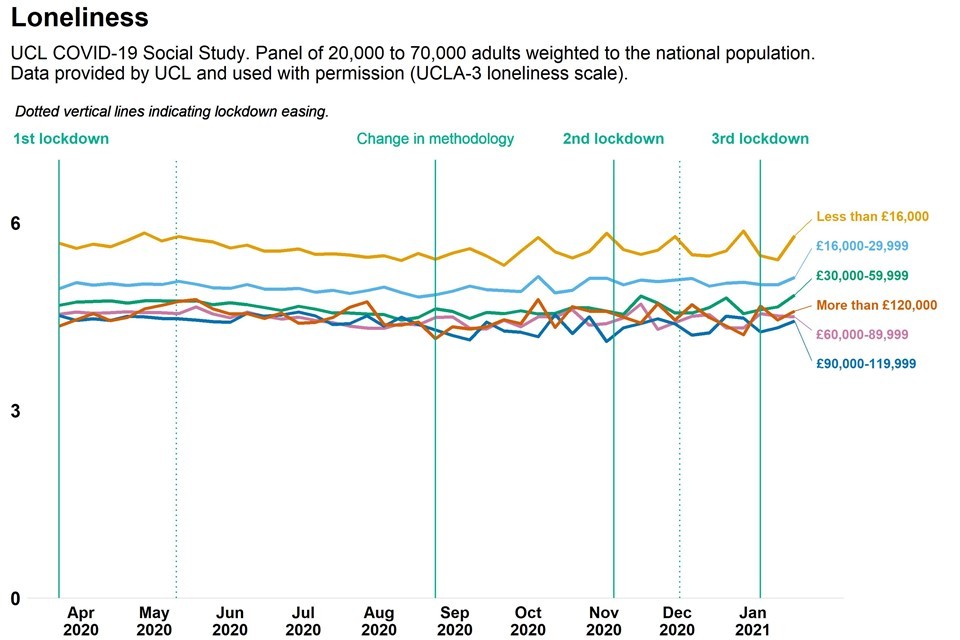

Respondents with an annual income of less than £16,000 have been more likely to report higher average levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness, and lower life satisfaction than respondents with higher annual incomes.

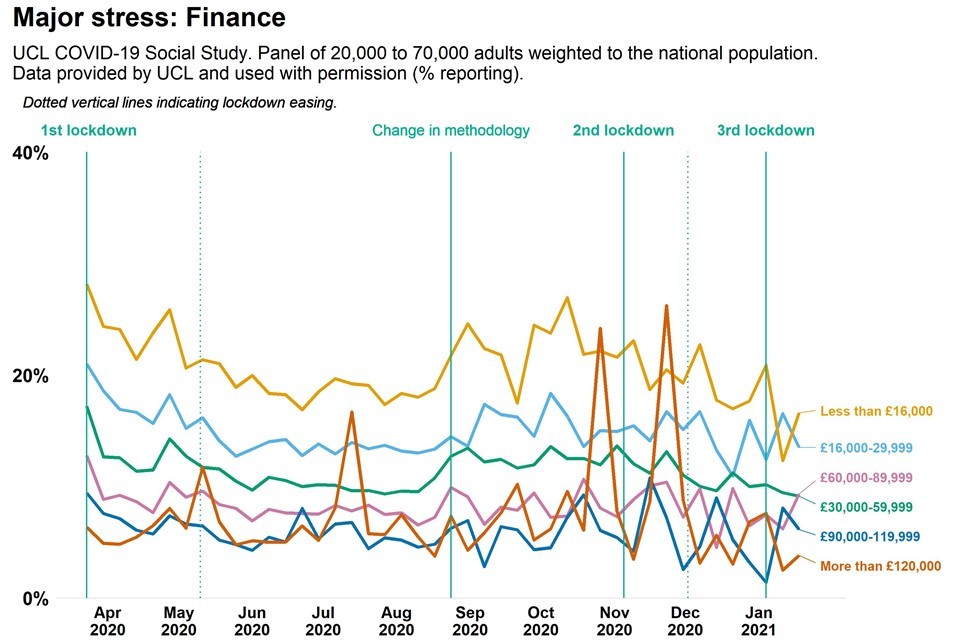

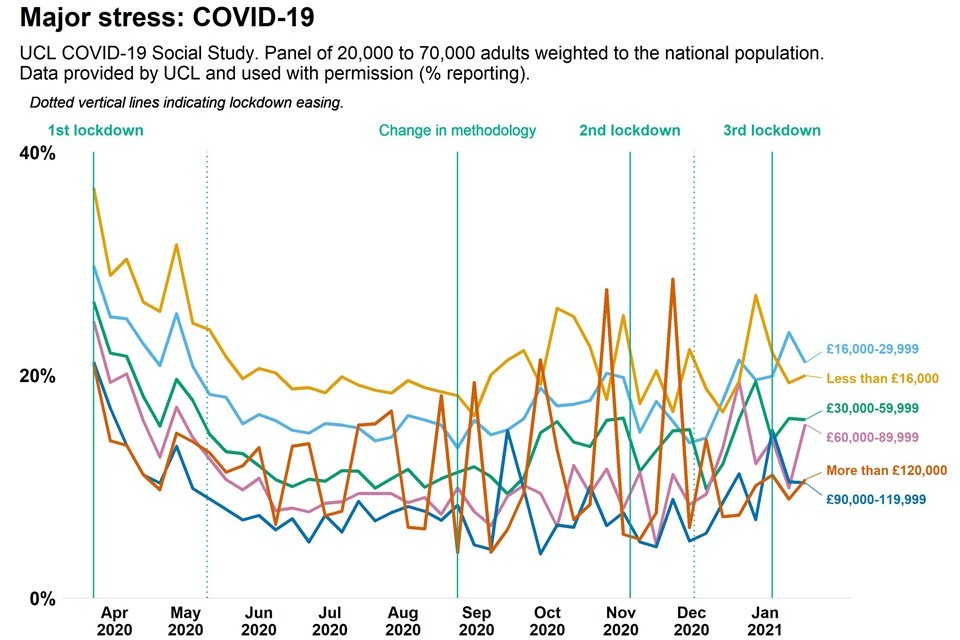

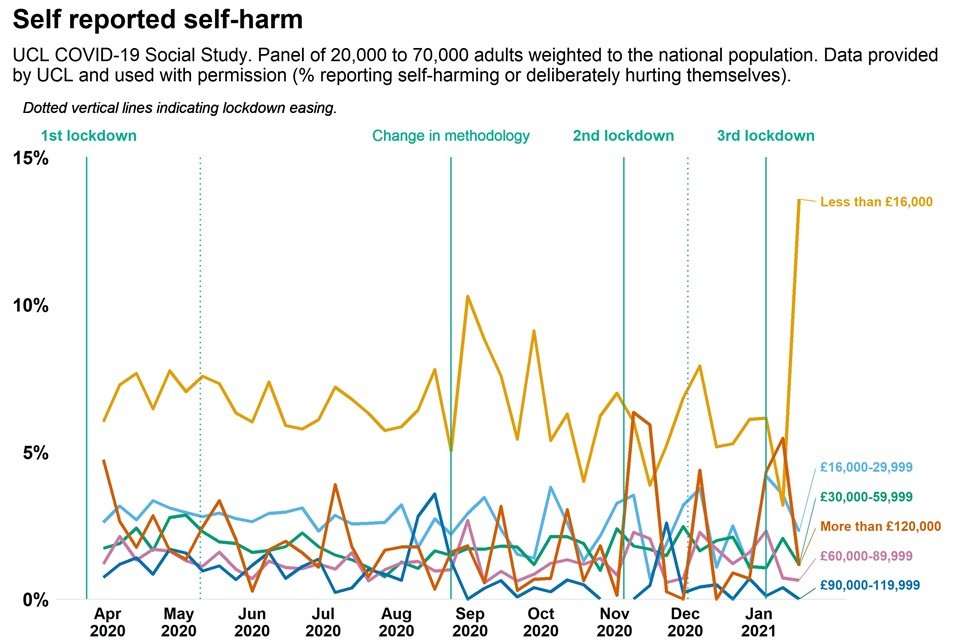

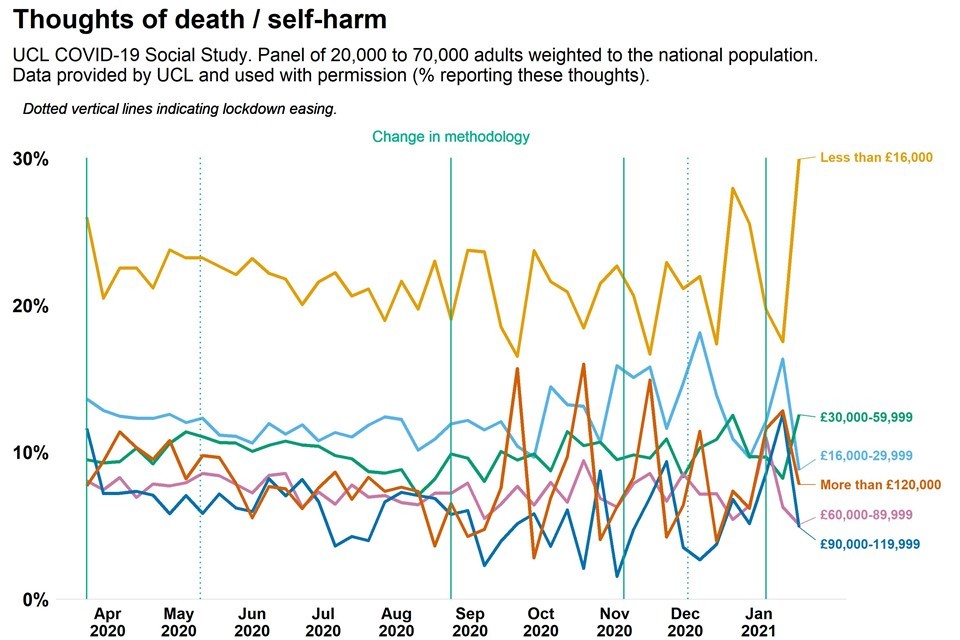

Respondents with an income of less than £16,000 have also been more likely to report major stress related to finance and COVID-19, as well as self-harm and thoughts of death and self-harm. Since September 2020 this distinction has been less clear for the self-harm and major stress measures.

The raw data does not show a clear income gradient beyond the £16,000 group. This means that higher income may not be associated with better mental health once income is above a certain threshold.

Average levels of anxiety, depression and life satisfaction improved marginally between April and September 2020 for all income groups, but may have deteriorated again after that.

Average levels of loneliness, self-harm and thoughts of death and self-harm appear to have remained relatively stable overall in each income group between April 2020 and January 2021. The large jump in week 4 of 2021 in thoughts of death and self-harm among adults with an income of less than £16,000 will need to be monitored.

Major COVID-19 and finance related stress decreased between April and August 2020 for all income groups. Since then it has either stabilised or started to increase again.

The increase in variation seen post September 2020 is likely to be due to a revision in methodology introduced at this time.

Each of these observations are based on data that has not yet been analysed. Further analysis of the data (such as that presented below) will be able to give more accurate details, as well as explore whether changes over time or differences between groups are clinically or statistically significant.

Up-to-date data is available on the WICH tool.

Graph showing population anxiety measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population depression measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population life satisfaction measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population loneliness measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population financial stress measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population COVID19 related stress measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population self reported self harm measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Graph showing population thoughts of suicide and self harm measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults by income

Analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects

Was there an association between mental health and wellbeing and income or employment before the pandemic?

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey was last conducted in 2014. It found that common mental health disorders were twice as common among unemployed adults than employed adults, and 4 times as common among adults who were in receipt of benefits than adults not in receipt of benefits.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic inequalities in chronic health conditions, employment status and housing conditions had the strongest associations with inequalities in psychological distress (PDF, 1.13MB) (from a range of sociodemographic factors). This means that the association between each of these factors and psychological distress was relatively strong.

In April 2020, ‘age and gender’ had the strongest association with psychological distress. Chronic conditions, employment status and housing conditions were still important, but not as strongly associated with psychological distress as ‘age and gender’.

By July 2020, soon after the first national lockdown was eased, the association between psychological distress and ‘age and gender’ (PDF, 1.13MB) had decreased to a level similar to before the pandemic. The original 3 factors returned to having the strongest associations with variation in psychological distress. However, local health and leisure facilities (as a measure of neighbourhood characteristics) now had a stronger association with psychological distress than before the pandemic.

Mental health and wellbeing by income

Overall, adults with low income or who have experienced loss of income have reported worse mental health and wellbeing symptoms than the general population since the onset of the pandemic.

Anxiety and depression

Evidence collected at the start of the first national lockdown highlighted that adults with lower incomes were more likely to report higher levels of anxiety and depression than adults with higher incomes (references 3, 4). Adults who experienced loss of income early in the first lockdown also reported higher levels of anxiety than the general population.

National data collected in 2019 and 2020 suggested that adults who were unable to afford an unexpected expense were more likely to experience some form of depression during the pandemic. Another study found that low socioeconomic position was associated with moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms between the end of March and the beginning of May 2020.

One study has found that adults in a lower socio-economic position reported larger increases in depression and anxiety following adverse experiences between April and May 2020 than adults in higher socio-economic positions. Adverse experiences included major loss of income or loss of employment.

Analysis of weekly data from March to August 2020 suggests that income related inequalities in anxiety and depression persisted throughout the period. There was no evidence to suggest that rates of deterioration or subsequent improvement were related to household income.

A comparison of data collected in the south west of England in April and June showed that adults with a history of financial problems were at greater risk of persistent anxiety.

Another local study, this time concentrating on mothers in Bradford, found that clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety during the first national lockdown were more common among mothers with more economic insecurity. The 2 variables with the strongest associations with clinically important increases (greater than 5 points) in depression and anxiety were loneliness and financial insecurity.

Psychological distress

Studies analysing psychological distress have found similar results to those measuring anxiety and depression. Adults in the lowest income group reported higher levels of psychological distress than adults in the highest income group. Adults who experienced loss of income early in the first lockdown also reported higher levels of psychological distress than the general population. However, net personal income did not predict changes in psychological distress in April 2020.

Moreover, once other factors are controlled for (such as chronic conditions, employment status and housing conditions), the association between income and psychological distress was relatively low (PDF, 1.13MB).

Loneliness

While the overall proportion of adults reporting that they felt lonely was stable throughout the first national lockdown, there was variation between sub-groups.

In April, adults with a lower income and the economically inactive were more likely to report being lonely than adults who were either employed or had a higher income. Adults with a low income or who were economically inactive were also more likely to report increasing rather than decreasing loneliness between the end of March and the beginning of May 2020.

Other measures

One study found in April 2020 that the reported frequency of abuse, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm were higher among people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage and unemployment. Another found that adults with perceived financial difficulties were more likely to report sleep loss.

Mental health and wellbeing by employment status

Loss of employment and changes in work patterns since the onset of the pandemic have been associated with worse mental health, with some groups affected more than others.

Unemployment

Early in the first national lockdown it was observed that having a job was protective against psychiatric distress and loneliness.

Adults who were unemployed or economically inactive reported higher levels of psychological distress than those in employment or who were retired.

Another study found that adults who were unemployed were 3 times less likely to say they were coping ‘very well’ than adults in employment. They were also more likely to say they were not coping well. Less than a third of the unemployed adults in this study reported that maintaining a healthy lifestyle aided their ability to cope with the stress of the pandemic.

Variation among adults in employment

Adults who were employed or retired before the pandemic reported higher than expected increases in psychological distress following the onset of the pandemic (based on trends between 2014 to 2019).

Adults who were unemployed or otherwise inactive reported higher average psychological distress than the comparison group, but the increase followed an expected path (based on trends between 2014 and 2019). In particular, adults working in ‘small employers and own account’ occupations have reported larger increases in psychological distress than unemployed adults and adults working in ‘managerial and professional’ occupations.

Working parents have reported larger increases in psychological distress than those without children. This has been associated with increased financial insecurity and time spent on childcare and home schooling. These burdens have not been shared equally between men and women, or between richer and poorer households.

Women in lower socioeconomic positions have been more likely than women in higher socioeconomic positions and men in general to be furloughed, working as a key worker or in a person facing role. Women in lower socioeconomic positions have been slightly more likely to report higher levels of psychological distress than women in higher socioeconomic positions although this does not follow a clear socioeconomic gradient (PDF, 933KB).

Change in employment status

Change in employment status has also been associated with changes in mental health and wellbeing.

Leaving paid work has been associated with poorer mental health, even after household income and other relevant factors are considered (such as age and gender). In contrast, having some paid work or some continued connection to a job has been better for mental health than not having any work at all.

Adults who were part-time employed before and during the pandemic, adults who are involved in the furlough job retention scheme, and adults in transition from full-time to part-time employment all report a similar level of psychological distress (PDF, 895KB) as those who have continued to work full-time.

There may be a widening gap in mental wellbeing resulting from the widening socioeconomic gap between immigrant and native-born working men. Employment disruption has not necessarily impacted on the mental well-being of native-born men, as long as their income has been protected. For immigrants, however, work hour reduction has generally been accompanied by psychological costs, with greater mental suffering among immigrant men who experience work hour reduction without income protection – particularly in the scenario of reduction to no work hours.