Remote education research

Updated 18 February 2021

Applies to England

Introduction

Since March 2020, the need for and the expectations placed on remote education have changed considerably. From the middle of March and for most of the summer term, the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic led to school buildings in England being closed for most pupils. There was no requirement to provide remote education during this period, although some guidance was published.[footnote 1] Schools were open to all pupils from September 2020 but, given the need for class and year group bubbles and self-isolating pupils, the Department for Education established a continuity directive for mandatory remote education.[footnote 2] School buildings were again closed to most pupils in January 2021. From that point, remote education has been a requirement, so that pupils can continue with their learning.[footnote 3]

At the beginning of January, we published guidance on ‘What is working well in remote education’.[footnote 4] As England entered a third national lockdown, that short paper was intended to provide the sector with some immediate advice and reassurance on useful remote education approaches that had been distilled from our recent research activities.

Remote education matters. Until mass vaccination is achieved, local lockdowns, class and year group bubbles and individuals self-isolating are likely to remain part of daily life. This will have a continuing impact on schools’ capabilities in delivering a broad and balanced curriculum to all pupils. Schools are likely to continue to rely on remote solutions to provide coverage and mitigate against learning loss. Furthermore, evidence from our interim visits suggests that given the amount of time and resources that school leaders have placed into developing their remote solutions over the past 10 months, it is likely that schools will incorporate aspects of remote education into their teaching after the pandemic.[footnote 5]

Understanding what successful remote education is has been a priority for Ofsted during the pandemic. Education providers have of course been learning ‘on the job’, and many will now be well advanced in their own understanding. This paper sets out what we have learned through our research and visits and we hope providers find it helpful.

What is remote education?

At Ofsted, we have defined remote education as being more than just education delivered through digital methods. The term ‘digital education’ has developed as a term that means involving or relating to use of computer technology.[footnote 6] However, we also need to take non-digital elements into consideration. Some schools may still be at the early stages of incorporating digital technology into their remote solution or, as our evidence indicates, may have decided against using any form of digital education due to their local contexts and other barriers to delivery. The following definitions therefore apply throughout this paper:

- Remote education: any learning that happens outside of the classroom, with the teacher not present in the same location as the pupils. This includes both digital and non-digital remote solutions.

- Digital remote education: remote learning delivered through digital technologies, often known as online learning.

- Blended learning: a mix of face-to-face and remote methods. An example would be the ‘flipped classroom’, where main input happens remotely (for example through video), while practice and tutoring happens in class.

- Synchronous education: this is live, typically a live lesson but also reflects other live practices such as chat groups, tutorials and one-to-one discussions that also happen in a live online setting. Asynchronous education is when the teacher prepares the material and the pupil accesses it at a later date. Asynchronous can involve both digital (pre-recorded videos) and non-digital (textbooks) materials.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic

A lot of the research literature on remote or online education focuses on its use in higher education, which, before the pandemic, was the area of education in which remote education was most used in England. Therefore, a lot of this literature is less relevant as it covers success characteristics in online education environments that are typically associated with adult learners.[footnote 7] Students in higher education will tend to be better at self-regulating their own learning. They will also have a level of expertise in their studies that has implications for successful distance learning. Novice learners, on the other hand, are more likely to struggle without appropriate prior knowledge or clear facilitation being provided.

From the papers that do exist on schools’ use of remote education, the findings are not strong. Studies on online charter schools[footnote 8] in the United States have found that students tend to perform worse on standardised assessments in these types of school compared with their peers who attend traditional settings.[footnote 9] Similar findings have also been found when comparing virtual learning environments to regular classes in US high schools.[footnote 10] The dominance of independent study in these online schools is likely to contribute to these outcomes, because students received less teacher contact time a week than in conventional schools.[footnote 11] Without clear scaffolding, for instance, online learning environments can be less effective for more novice learners.[footnote 12] School principals also reported that maintaining student engagement was their greatest challenge by far.[footnote 13] Pupils’ motivation to participate has also been identified as one of the main barriers to successful implementation of flipped learning models of teaching.[footnote 14] This is drawn out further in the evidence we have gathered on pupil engagement later in this report.

The body of research on digital technologies used within schools (not remotely) is more substantial. However, the quality of these studies varies considerably. Some feature narrow measures of impact.[footnote 15] Others emphasise the vision and innovation of the technical offer at the expense of adequately commenting on the quality of teaching and impact on learning.[footnote 16] For instance, a review of research on the use of tablet devices in schools found a lack of detailed explanations given to teachers about how or why using tablets in certain activities can improve learning.[footnote 17] In general, however, the evidence does give several helpful insights. For instance, digital technology can be useful when used to supplement teaching, particularly if the technology used and the desired learning outcome are closely aligned. Technological benefits have also been noted about methods that support teachers to give more effective feedback and through systems that can motivate students to practise more.[footnote 18]

Since the COVID-19 pandemic

More recent studies have focused on the degree of learning loss that pupils have encountered while learning from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. One paper, on the Dutch primary school system, highlights that pupils had made little or no progress while learning from home. This is despite a relatively short (8-week) lockdown and the country having a high degree of technological preparedness.[footnote 19] These results suggest much larger losses are likely in countries that are less prepared for remote education. Closer to home, a report from the University of Southampton has calculated that in the first month of the lockdown, pupils in England suffered from a high degree of learning loss.[footnote 20] It is worth noting, however, that at the start of the first national lockdown in England, schools were not required to provide remote education. Both of these papers report that the loss was more pronounced for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds than for other children. This builds on evidence of learning loss that we highlighted in our most recent annual report.[footnote 21]

From the picture described above, remote education would appear to be a poor replacement for normal classroom practice. However, even if not a full replacement for classroom teaching, it is a lot better than not having a remote education offer at all.

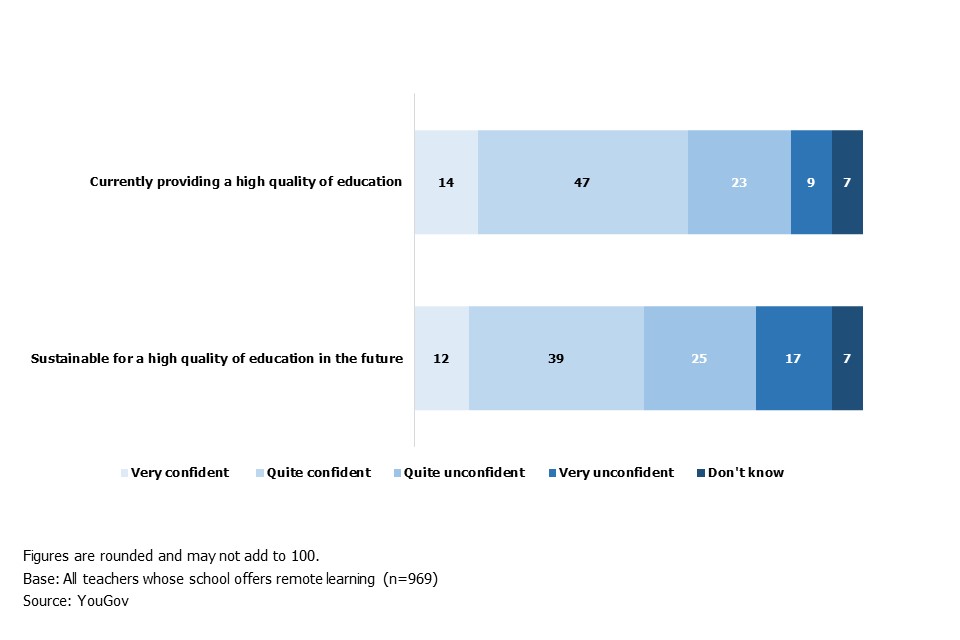

Although based on self-reported views, the findings from our YouGov survey show that three-fifths of the teachers responding were quite confident that they were providing a high-quality education through their school’s remote education solution when this was needed.[footnote 22] In addition, just over half were confident their solution was sustainable for the future (figure 1). On this basis, it is likely that a large proportion of schools in England providing a remote solution are doing well at mitigating the amount of learning loss that children experience.

Figure 1: Teachers’ responses to the question ‘How confident are you that your remote education solution is of high quality?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

It is important to understand the factors associated with the remote education solutions that confident teachers are delivering in more detail. We expect that a clearer picture of their activities will provide more helpful insight for other schools in developing quality remote solutions as well as aiding policy decision-making in the future. That is what the remainder of this report will aim to do.

Curriculum alignment in remote education

Some schools found it easier than others

The potential for learning loss at the beginning of the pandemic was exceptionally high for children in England.

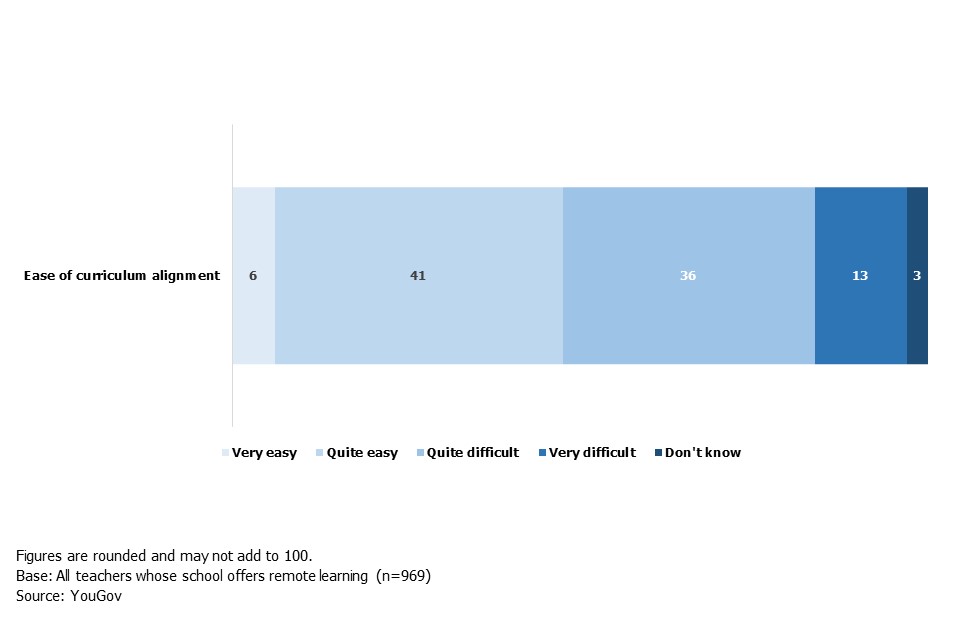

This is reflected in the responses on the YouGov questionnaire, where 49% of teachers thought that aligning remote education with their curriculum was a difficult process (figure 2). The evidence from leaders, however, suggests that this could be mitigated where schools already had a strong foundation of quality thinking around curriculum and pedagogy in place prior to the pandemic. In these cases, leaders spoke confidently about their curriculum design, but also reported an easier transition into delivering education remotely.

Figure 2: Teachers’ responses to the question, ‘How easy or difficult has it been to align remote learning with the curriculum?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

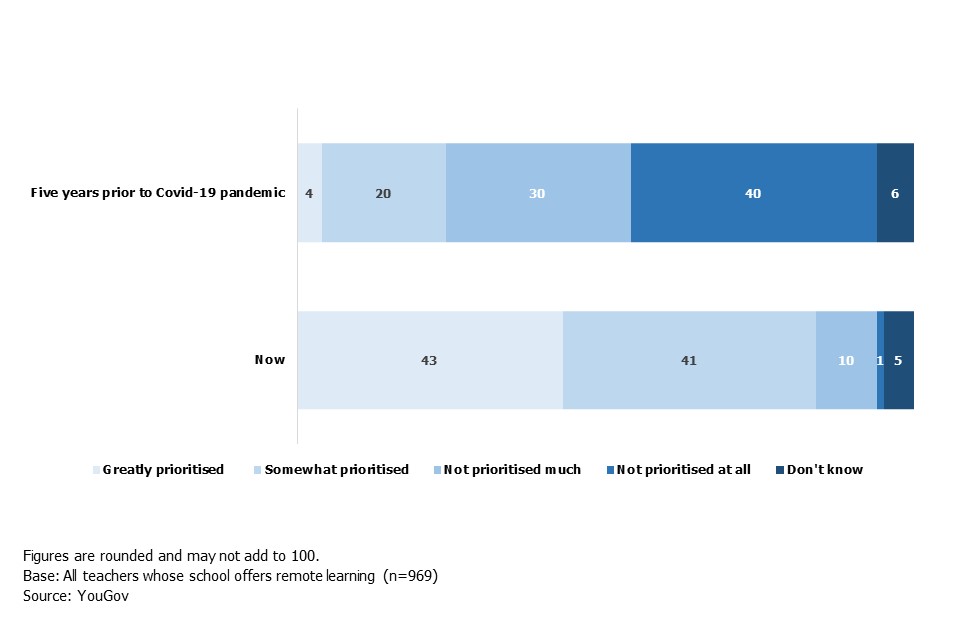

In other ways, the transition to remote education was more difficult. For instance, some schools decided to deliver their curriculum through a digital remote education solution. However, most teachers responding to the YouGov questionnaire said that the extent of digital investment in their school in the years before the pandemic had not been a priority previously (figure 3). Since the first national lockdown, however, this has drastically changed. The interviews with experts in the summer term also suggested that most of the barriers to remote education that schools following a digital pathway had encountered during the first national lockdown were due to a lack of investment in educational technology in the sector over the last 10 years. As one participant stated, ‘we were unprepared’.

Figure 3: Teachers’ responses to the question ‘To what extent was investment in digital education prioritised?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

Where the transition to remote education was easiest, it built upon existing provision. Some leaders displayed a degree of foresight before the March 2020 lockdown. These leaders anticipated that some form of remote education would be necessary and began preparations several weeks before official announcements were made. This provided them with time to lay the groundwork for their future solutions. In general, leaders in these schools had made early, effective decisions on the direction their remote systems would take, be that a focus on non-digital or on digital solutions. This included deciding on clear and simple protocols to provide remote education that everyone understands. A few leaders specified that attempting to integrate a number of different platforms and approaches into a single solution was problematic, as this tended to overload or confuse staff, pupils and parents.

Leaders from the focused interviews were keen to highlight that, despite their starting points and the advancements they have made over the last 10 months, they still consider that their remote strategy is maturing. They had not reached an end-point and there was still much more to do. This was particularly the case in their thinking around aspects of teaching and assessment and how further adaption is required to enhance these components. Similarly, evidence from the interim visits showed that schools are at quite different stages of development to each other and that their remote learning offers vary widely.

Adapting a classroom curriculum to remote education

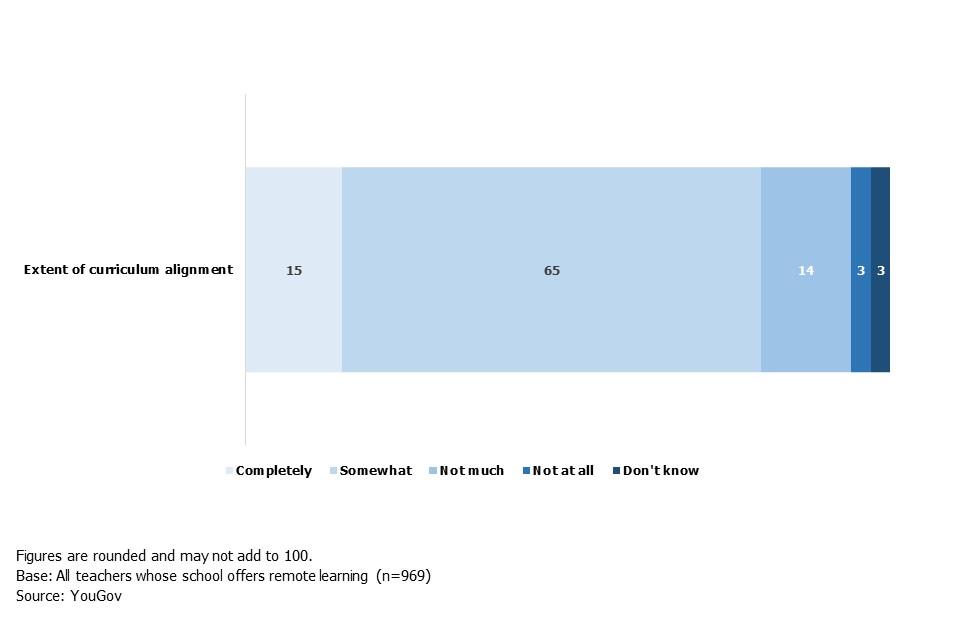

The YouGov questionnaire data highlights that only a small proportion of teachers (15%) reported that their school had managed to align their remote education solution completely to their intended curriculum (figure 4).

Figure 4: Teachers’ responses to question, ‘To what extent would you say remote education has been aligned with the curriculum?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

Several leaders from the focused interviews mentioned how effective remote education should conform to what we already know about human cognition and how people learn. They were clear that remote education, as the medium for teaching, does not change how pupils learn. Principles of curriculum design such as scaffolding, interleaving and retrieval practice are still therefore important within their solutions for aiding pupils to know more and remember more.

In addition, most of the leaders spoke about aligning their curriculum to mirror sequences of learning, with an emphasis on subject breadth and depth. Several leaders argued that the breadth and depth of the curriculum should not be compromised or narrowed for remote education.

Interestingly, unlike some at the interim visits, only one of the school leaders we spoke to from the focused interviews used the phrase ‘recovery curriculum’ to describe their curriculum offer. This suggests that there may be some conflict between the aims of minimising learning loss – which could lead to programmes that necessarily lower curriculum expectations – and ensuring that the rigour of a wide and deep curriculum is maintained.

Large adjustments to curriculum content in these schools was rare. Leaders stated that tweaking the curriculum was generally enough for re-purposing for a remote environment. One leader referred to this as ‘trimming the fat’. It gave staff opportunities to examine current schemes of work and adjust them to ensure that the focus was on the essential core knowledge required. They were not creating specific curriculums for remote education.

Leaders also regularly referred to the use of widely available free online resources and materials to help deliver the curriculum remotely. However, in these cases, resources were selected to complement and enhance the existing schemes of work rather than used to deliver one-off lessons or activities. A few leaders mentioned that, where these resources did not fit their programmes of work, they had taken away some core principles of this solution and developed their own resources instead. This was particularly the case with staff developing their own pre-recorded lessons. In this way, external resources were adapted to fit into the existing sequencing of learning with the school’s curriculum.

There was, however, general agreement from these leaders that some subjects were more difficult to deliver remotely. Art, science, physical education and design and technology were commonly cited as problematic. This is because of their practical aspects, which develop pupils’ disciplinary knowledge in parts of these subjects. Despite difficulties, leaders explained how they managed to get around these issues to ensure that as full a curriculum offer as possible was still guaranteed for pupils. The following are a few examples of how these schools achieved this:

- In a few cases, the curriculum was re-arranged so that more theoretical content could be delivered during lockdown, with practical components reserved for the full return to classroom practice. However, staff were careful in how this was arranged so that it did not undermine an appropriate sequence of knowledge.

- Some of the schools used their internal resources and delivered art materials to pupils’ homes so that they could continue with the planned curriculum. For instance, one school had ensured that all pupils had access to a water-colouring pack and had prepared the curriculum to cover this artistic technique for the period of lockdown.

- Similarly, some schools provided their pupils with music equipment. Students were also able to upload small compositions onto the schools learning platform, so this could be assessed by teachers.

- For science, these schools had generally adapted practical lessons so that teachers modelled and demonstrated concepts and phenomena through live or pre-recorded lessons.

- A few leaders discussed how the curriculum in some subjects (particularly science and cooking) had been adapted to make use of common household materials to resource practical elements of subjects.

- Leaders spoke about the importance of physical education. Some schools set a range of activities (using either resources that they had created or by sending links to external activities) for pupils to do at home, with family members as well.

- Language departments had realised the importance of pupils hearing how to pronounce dialogue in the target language to secure their knowledge. They uploaded audio files to the schools’ online platform to help pupils. Primary schools were also applying similar methods for delivery of phonics lessons.

Ultimately, leaders in these schools did not see remote education as a barrier to curriculum delivery. They thought the learning opportunities, level of engagement and expectations should be the same regardless, through a centralised, aligned curriculum.

Curriculum equity in blended learning approaches

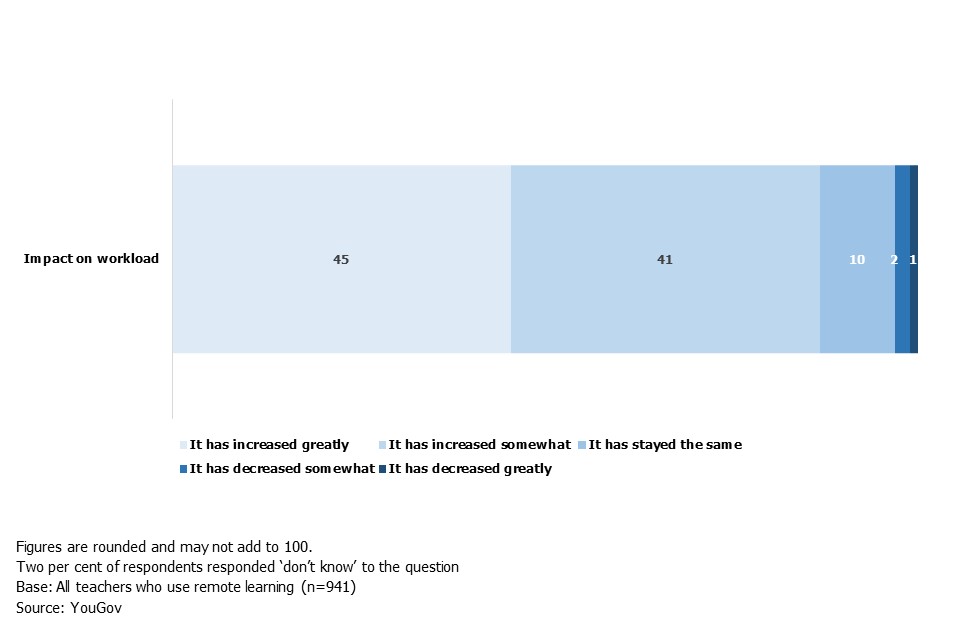

A common message from school leaders in the focused interviews and the interim visits was how remote delivery had become trickier during the autumn term. This was due to the changing context. Remote education solutions were now subservient to curriculum delivery mostly happening in the classroom following the return of all pupils to school. Leaders frequently cited the workload burden that this placed on teachers. Two of the experts from the summer term interviews commented that delivering both classroom and remote education from September onwards would be very challenging for any teacher. This corroborates with the findings from the YouGov questionnaire, where over four-fifths of teachers specified that their workload had increased since the implementation of remote education.

Figure 5: Teachers’ responses to question, ‘Thinking about time spent on planning for and teaching remote learning, to what extent has your workload increased or decreased since remote education was implemented?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

Leaders from the focused interviews suggested this was less of a concern when sending class or year group bubbles home. In general, teachers would revert to their school’s full remote education solution in these situations. However, in the case of self-isolating pupils, some leaders said that pupils would generally receive a different offer compared to their peers. This would typically consist of the same content and resources as the class lesson but with reduced contact time and feedback from the class teacher. Despite some of these schools using teaching assistants to provide individual support and putting in place assessment checks on the pupils’ return to school, this method appears to have some implications for curriculum equity.

A few of the leaders, however, did explain that their schools were using blended learning approaches to get around this issue. For them, removing the friction between the physical classroom and learning from home was the main priority. In these cases, a versatile online platform was central to the blended approach. The leader of one school explained that a platform like this allowed a teacher to be video-recorded and the lesson streamed (live or pre-recorded) to pupils situated in another classroom or at home. This ensured that pupils who were not in the physical classroom would have access not only to the full content of the lesson but also digital tools to facilitate real-time scaffolding and feedback. This included touch-screen technology for posing immediate questions to the teacher, the use of chat-boxes or the ‘raising hand’ feature of video meeting software.[footnote 23] Another leader explained how a blended approach was helping them to re-engage disaffected learners, particularly those who are anxious or overstimulated in a physical classroom setting, by allowing them to stream lessons from the school’s on-site inclusion centre.

These leaders felt that it did not matter whether the experience uses synchronous or asynchronous (or mixed) approaches. What was important was that pupils could receive the same curriculum, pedagogy, assessment and level of socialisation to support their learning. However, this is not a quick fix solution. These schools had been using digital technology for numerous years before the pandemic. Leaders had already invested in the technical capacity and staff and pupil training required to reach the scale of implementation in this blended learning approach. What these examples do show is that curriculum equity can be managed for the long-term, once solutions become more mature.

Pedagogy – keeping it simple

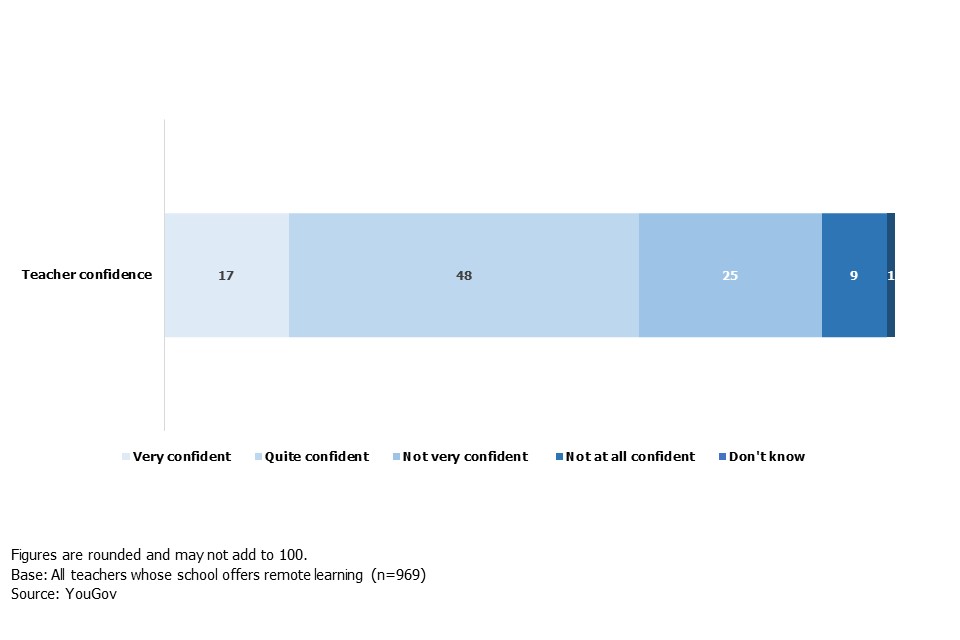

Teacher responses to the YouGov questionnaire highlight that around a third lack confidence in teaching through a remote solution (figure 6). However, an effective solution does not need to be over-complicated. As the leaders we spoke to suggested, some level of adaptation to the remote medium is required, but this should not override principles of delivering effective teaching.

Figure 6: Teacher responses to the question ‘How confident are you in teaching through remote methods effectively?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

All of the leaders reported that the importance of the quality of teaching is the same in remote education as it is for classroom-based provision. There need to be effective systems in place for scaffolding learning, demonstrating, responding to pupil questions and providing feedback. Most of them specified that the focus must remain on ensuring that pupils are learning rather than on the technology: ‘just because you’re doing live lessons doesn’t mean it’s good teaching’. Several participants commented that their teachers were expected to deliver lessons as they would in person, with pedagogical aspects such as modelling, questioning and feedback happening as a matter of course.

They were clear, however, that remote teaching does need a slightly different approach. This is because many dynamics of classroom teaching – such as pupil interactions, relationship building, providing feedback, delivery of practical components of a lesson and other experiences – are not directly replicable in a remote environment. Adaptations to teaching remotely that the leaders we spoke to had used included:

- a closer focus on verbal explanations and exposition, and presenting concepts in ‘bitesize’ segments, so that pupils could concentrate for short bursts of time and teachers could check pupils understood the learning points regularly

- shortening the length of lessons to aid pupils’ concentration spans and to reduce screen time when working at home

- using a variety of different ways of presenting information, although still making sure they are an appropriate fit to the task; for example, modelling on a whiteboard, using videos, teacher demonstrations of practical work to introduce and reinforce key concepts, using dual coding (combining words and visuals such as graphics and images) to present ideas and concepts

- ensuring time for pupils to practise what they have learned, for example through independent work or pupil discussion

- avoiding open-ended tasks that can potentially overwhelm pupils (just as in the classroom, most pupils will be novices in the content being taught) but providing opportunities to scaffold concepts

Leaders from the autumn discussions reported that a mix of live and pre-recorded lessons were generally used to deliver content. Some felt that interaction and engagement was greater during live lessons. They felt that this made checking pupils’ attendance, responding to their questions and giving immediate feedback easier. Several used a mix of synchronous and asynchronous approaches, which they suggested made better use of remote provision. For instance, this may involve the main content of the lesson being delivered live, but with independent work, activities or retrieval practice taking place offline (often to reduce screen-time) before returning to a group environment with pupils to discuss what they had learned.

Some leaders prioritised pre-recorded lessons above live sessions, stating teachers’ relative lack of confidence in front of the camera as a rationale for this. However, this was usually complemented with a mechanism for discussion with pupils at a later stage in order that teachers can check their conceptual understanding.

Most leaders thought that seeing and hearing their teacher and peers is important for pupils, particularly for their well-being and engagement with their work. One school reported that when pupils could see each other using cameras, they had more energy for lessons than when they were solely using audio. There was recognition from some leaders that their staff had needed to cross the line from ‘being scared of behaviour and safety issues’ to ‘we want to learn [how to do this]’. Some schools have used regular staff training to enhance teachers’ application of pedagogical principles in a remote lesson (for instance, where to stand, improving exposition or use of white boards) to increase their confidence in front of the camera. This has subsequently led to an increase in the number of live or pre-recorded lessons being delivered by teaching staff to their pupils.

Checking what pupils are learning

Learning is not fundamentally different when done remotely. Feedback and assessment are still as important as in the classroom. It can be harder to give immediate feedback to pupils remotely than in the classroom, but teachers have found some clever ways to do this, as outlined below.

Feedback

Quality feedback should allow pupils to know:

- where they currently are in terms of the topic, task or knowledge they are working on

- where they need to get to

- how they can close any gap between the two

Whether delivered remotely or in the physical classroom, quality feedback is dependent on the same mechanisms: the ability of a teacher to see pupils’ learning processes, understand their needs and to suggest ways for improvement in both daily activities as well as in summative assessments.

Similar to the interim visit evidence, most of the leaders from the focused interviews highlighted that this was still a developing area within their remote education solutions. One issue they highlighted was that picking up on pupil misconceptions in the learning process was not quite as immediate as in the classroom. For instance, they highlighted the fact that even in live lessons, the inability to ‘wander round and look at pupils’ faces in the classroom’ was a barrier to normal informal feedback approaches, as it is more difficult to check whether pupils are confused from their expressions and body language. They also frequently specified that feedback needs to be proportionate to the solution. One leader mentioned that ‘children aren’t daft – a thumbs up wears thin!’ However, several examples of how their schools were delivering regular feedback were picked up from the discussions:

- A few leaders specified that they were attempting to pre-empt the misconceptions pupils may encounter in their planning for remote lessons, particularly those that are pre-recorded.

- Others indicated that their solutions involved more direct communication with pupils to provide feedback. This included the use of chatroom discussions, 1-to-1 calls, interactive touch-screen questioning in live lessons and the use of adaptive learning software.

- In another example, digital exercise books were being used where immediate commenting, editing and feedback between students and teachers could be managed to communicate misconceptions and aid learning throughout the lesson.

However, several participants mentioned that the quality and richness of feedback are still more important than the ways in which feedback is delivered. For example, one school emphasised the importance of instant feedback in adapting individual pupils’ remote education activities. Leaders explained that pupils complete their work at home; the teacher discusses their work daily via phone and/or video calls; the work is then adapted for the next day if it was found to be too hard. In this case, the teacher highlighted the value of regular communication, so the medium could be adapted to needs to improve learning. However, we should not underestimate the workload implications here.

Assessment

Assessment was one of the main areas that schools from the interim visits considered they needed to think more about. School leaders were often monitoring attendance (if digital) and ‘engagement’ to some degree, but often not really assessing learning – they identified this as the next priority. Similarly, there was general recognition from the focused interview participants that ‘the offer [had] developed and improved over time’. However, these leaders specified the importance of assessment to check pupils’ understanding and inform curriculum planning. For instance, one mentioned that ‘assessment needs to be clear: it’s the bridge between teaching and learning’. They understood that just having data to show that pupils are simply accessing resources (either through synchronous or asynchronous means) is not nearly enough to speak about pupils’ progress.

Despite limitations to observing real-time learning processes, some of the schools assessed pupils’ substantive knowledge on a daily basis. This was linked to lessons they had just completed or used for means of retrieval a few weeks later to check how much learning had been retained. Generally, pupils’ substantive knowledge was checked through low-stakes testing, such as online forms, quizzes and the use of chat boxes and polls in online platforms. Some spoke of using multiple choice questions that directed pupils to follow up when they provided an incorrect answer.

A few of the schools also had systems in place to regularly assess pupils’ progress through the curriculum. Leaders in these schools considered this to be essential for pupils’ learning. They felt that low-stakes quizzing was less useful for checking how pupils could place their knowledge into relevant contexts. This typically required pupils to submit more detailed written work or photographs of outputs from activities to an online platform. Teachers could then annotate and mark the work to provide more detailed assessments of pupils understanding and identify what pupils needed to work on further. Some leaders referred to summative assessments taking place remotely at previously defined assessment points, such as end-of-year exams. In these cases, they used a secure digital exam platform, which alerts teachers to data on plagiarism and cheating. A couple of schools said that they used ‘gap assessment’ to complement rapid quizzes. For example, one primary school used dedicated time for pupils to ask questions in an open environment for extra support, alongside using interactive learning diaries, to keep teachers informed of whether pupils had the necessary understanding to move on to the next part of their learning.

A few leaders were particularly clear about the purpose of their assessment processes: that it was for feeding back into the curriculum and subsequent remote lesson planning. In these examples, leaders were insistent that the curriculum would not be rushed through if pupils had failed to grasp important concepts. They were also able to provide evidence of how they knew their assessment systems were working. For instance, in a couple of schools, staff were able to identify where pupils had not completed work independently but had received a lot of parent input. This allowed leaders to remind parents that this practice did not benefit their pupils’ learning.

Most of the leaders pointed out the need to respond more quickly to assessment information for remote education compared with in school, to maintain the focus and pace of learning remotely and to plan the next steps in pupils’ learning. There is a real danger that if assessment is left until pupils return to school, it could greatly contribute to their learning loss.

Engagement

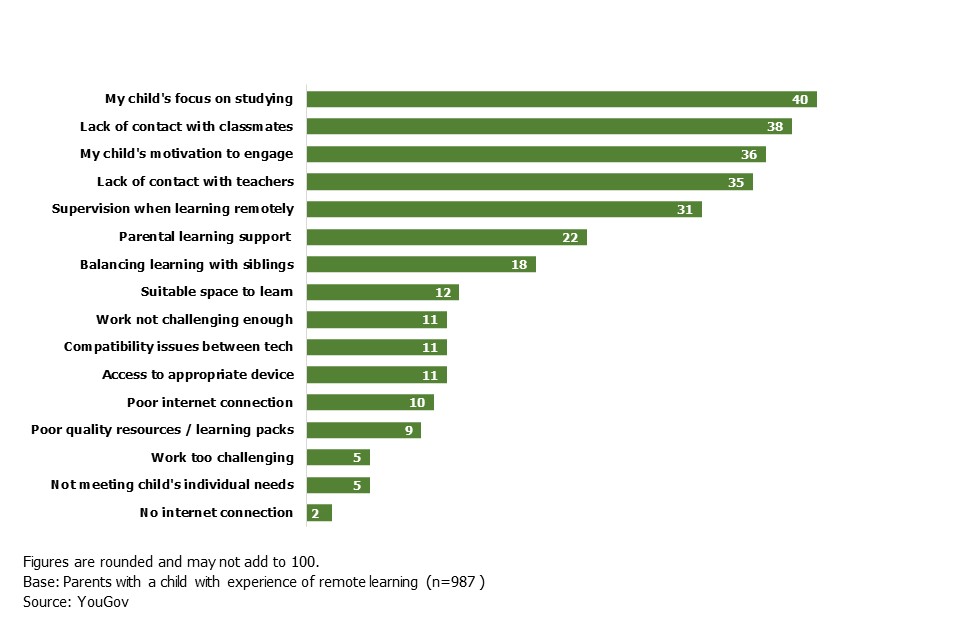

Much emphasis has previously been placed on the lack of resources at home, especially digital technology, for pupils to fully access and participate in remote education. However, parents’ responses to the YouGov questionnaire highlight that their children’s motivation is of greater concern to them (figure 7). The data highlights that 11% of parents saw access to an appropriate device as a challenge, compared to 40% who responded their child’s focus on studying was a worry.

Figure 7: Parents’ responses to the question ‘What have been the main challenges for your child when learning remotely from home?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

Interestingly, the parents’ responses align with the literature on the main weaknesses of online charter schools in the United States. Not only does pupil engagement feature as a concern, but also lack of contact with teachers (35%). These views also corroborate recent data from the Office of National Statistics. While 52% of parents suggested that a child in their household was struggling to continue their education while at home, only one in 10 of these parents identified that a lack of devices was the reason for struggling. Instead, most of these parents (77%) identified a lack of motivation as the main concern around continuing with their education.[footnote 24] We will provide further insight into pupil participation, particularly on the scale of the problem, as part of our spring term monitoring visits.

From evaluations of their own remote provision, school leaders in the focused reviews also identified pupil motivation as a common weakness in their early remote solutions. Consequently, they had developed a range of tactics to combat and increase pupils’ curriculum engagement. Nearly all mentioned they were developing better systems for pupil and teacher interactions. Often, interactions were facilitated by tools embedded in each providers’ chosen digital learning platform. For example, several platforms offered the capacity for an ongoing dialogue between the teacher and pupil on individual pieces of work.

Similarly, a few leaders specified that their schools had tried to create opportunities for student-to-student interaction to boost motivation and morale in their cohort. This was done through breakout rooms online, or through messaging boards/apps. A couple of schools mentioned that their nativity play was able to be streamed remotely. Leaders believed that this had created a sense of stability and community for the pupils involved. Another school arranged for children to sing to a local care home through a live online platform.

Some leaders felt that it was hard to ascertain the ‘true’ engagement of pupils. However, most of the leaders interviewed had also adopted some form of engagement monitoring. Again, this monitoring often took place through a feature in their digital platform. A number of schools had enhanced their approach. A commonly cited policy was to directly contact pupils’ parents when pupil motivation appeared to be lacking. A strength of the more effective platforms was that they not only provided a more accurate picture of engagement, for example by showing data on active hours or tracking pupils’ activity within the application, but they then linked this back to assessment that tracked pupils’ progression through the curriculum.

Remote education systems

Digital learning

Most of the leaders we spoke to who focused on a digital remote solution mentioned that access to digital devices was an initial barrier to remote education for some of their pupils. This was particularly the case for pupils from more disadvantaged backgrounds. However, by the time we spoke to these leaders in the autumn term, most of the schools had overcome these issues. This was often because school leaders were highly concerned with the digital divide and went out of their way to ensure that all pupils could access their digital platform.

Most used parental questionnaires to identify where gaps in digital provision existed so they could provide targeted support to those who needed it. They were then pro-active in sourcing appropriate devices, typically computer laptops or similar, from the local community. Some schools mentioned that they had worked with local businesses, charities and other external stakeholders to acquire devices. A couple of leaders mentioned they had used their COVID-19 catch-up premium funding to purchase digital equipment. Only a few leaders interviewed stated that access to digital provision was still an ongoing obstacle. These leaders were generally providing non-digital solutions for these pupils, such as slide-packs and worksheets, that matched the curriculum content other pupils were receiving.

Accessibility

The data from the interim visits highlighted the fact that, while there is an increasing use of live and recorded lessons in all types of schools, other barriers to the effective delivery of this remain. The views of leaders from the focused interviews emphasised this further. Leaders were clear that simply providing a device for all pupils is not necessarily a solution for access. The additional issues they raised, in some cases, affected decisions on the design of a remote solution, include the following:

- device appropriateness – mobile phones and tablets were generally considered a poorer tool for accessing and making use of content than a laptop

- poor quality or no internet connection – a few leaders had prioritised access to dongles or pre-loaded data cards for families that lacked access

- sharing with siblings – live lessons in a timetabled approach are more problematic in this scenario because pupils may not always have access to a device at times that align with a predetermined timetable

- availability of parental support – particularly for primary-aged children

- an appropriate environment for learning – the physical, social or emotional environment pupils find themselves in under remote conditions may not always be conducive to equality of access to remote provision

While the leaders from the focused interviews generally felt that they had alleviated most of these concerns, leaders in some schools from the interim visits were still struggling with these issues.

Flexible solutions

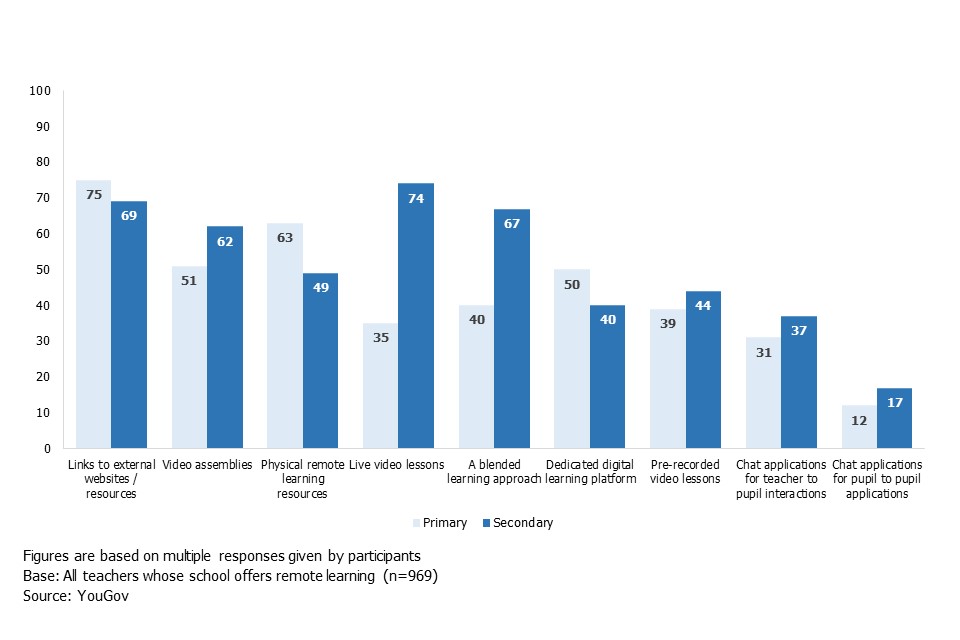

A strong theme from each school’s remote education journey was that there was no one-size-fits-all approach. This is further confirmed by the YouGov questionnaire data, which identifies the various methods teachers are applying as part of their remote education solution (figure 8). Live lessons are a much more common feature in secondary school solutions, whereas primary school teachers indicated they were more frequently delivering content through physical resources and materials.

Figure 8: Teachers’ responses to the question ‘Which of the following remote education approaches does your school offer?’ (in percentages)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

School leaders are clearly making different choices about how best to deliver remote education. Each school has needed to consider carefully the multiple contextual factors at play for the design they have ultimately decided to use. The barriers discussed in the previous section were also a strong part of the decision-making. Leaders approached this in a range of ways:

- Some offered a remote timetable that was the same as the usual school timetable. This usually consisted of most aspects of engagement being delivered through live sessions. Proponents of this approach argued that it helped maintain consistency and routine for pupils and allowed for teachers to manage engagement well.

- Some offered a primarily digital-based asynchronous remote solution, which normally made use of pre-recorded lessons. Commonly cited rationales for this approach included reducing pressures on families and parents (for example, where parents may also be working from home and unable to support, or multiple children are sharing one device), as well as identifying and solving disengagement, where teachers feared students may not be able to stay engaged for the duration of a full-length live lesson. Asynchronous approaches tended to offer more flexibility for pupils/parents to take control of their learning at home. These schools had some live systems available to provide feedback for pupils, such as through tutorial sessions.

- A smaller number of schools offered primarily non-digital asynchronous remote solutions. In these cases, teachers delivered most of their teaching though paper-based ‘work packs’, worksheets, textbooks, and other physical resources, such as art supplies, which one school delivered to pupils’ homes. The schools offering this type of approach usually, however, had some form of digital provision for teacher–pupil interaction, feedback, assessment and tracking.

- A few schools had adopted a mixed delivery approach, which combined synchronous and asynchronous elements in line with their school’s specific context and needs.

Non-digital remote education

A few of the leaders from the focused interviews explained that they were not providing their pupils with a digital remote education offer but were instead providing learning resources in a more paper-based approach. In some cases, non-digital solutions were preferable to their digital alternatives, for example:

- for pupils with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND) who risk sensory overload when working at a screen

- for early years children, who rely on physical experiences as part of their development for which digital alternatives may not be adequate

- for schools that had difficulties in securing adequate digital access for their pupils

As stated in our shorter guidance published earlier this month, a good textbook, slide-pack or worksheet can provide suitable remote education when used thoughtfully and in line with the school’s curriculum.[footnote 25]

The biggest concern with remote education delivery is not how it is delivered but the dialogic aspect of the teacher–pupil relationship, which is central to pupils’ progression. Non-digital solutions should still offer opportunities for regular pupil feedback and assessment. For instance, we heard a few examples, in the context of self-isolating pupils, of staff waiting until pupils returned to the classroom to assess learning loss. The danger is that this may well be too little too late.

Digital solutions have some obvious benefits for remote education. The potential for immediacy of feedback is an important one. Certain digital learning platforms appear to aid these types of teacher–pupil interaction. Some schools are already well on their way to developing robust feedback and assessment systems into their remote offer. Whether digital or non-digital remote education (or a mixture) is most suitable for a particular school is less important than making sure that the quality of delivery is not lost in the transition from in-school to remote provision.

Evaluating and reviewing

Most leaders reported that their current remote education solution had been established through a process of continuous development, adjustment and refinement. As one leader put it, ‘we learned along the way and adapted to changing circumstances’. Leaders, teachers and other decision-makers in schools showed remarkable agility and innovation as they incorporated different strands into their offers – described by some as a process of ‘trial and error’. As repeatedly reflected elsewhere across our evidence base, there was no uniform approach to schools’ ongoing adaptations. The common thread was that schools regularly monitored and evaluated their approaches to ensure consistency and effectiveness in this solution. That is, identifying what works and what does not. Leaders considered relevant research alongside close consultation with staff, pupils and parents and official guidance when deciding on next steps. Some of the approaches to adaptation were as follows:

- Regular ‘quality assurance’ of remote provisions: several schools described incorporating insights about what was working and what was not into their ongoing professional development and made changes accordingly. This was done at a range of intervals – some schools did this half-termly, others fortnightly, weekly, even daily. The chosen approach depended very much on each school’s specific context and needs.

- Some schools implemented various ‘models’ that corresponded to different rates of attendance within their cohorts. Schools variously described models for situations where:

- individual students within a class are isolating and the rest of the class is in school

- a large ‘bubble’ or group within a year group are isolating

- the whole year group is isolating

- the teacher is isolating

- Some schools had attempted to create a unified experience across different contexts. Others had different defined strategies in place for each situation. In many cases, this move towards greater differentiation was an aspect of the growing maturity of a school’s remote education offer.

- It was often reported that schools had engaged with pupils’ parents and carers to try to work out which aspects of their provision needed improvement. Although this was most commonly referred to in the context of access (that is, working out which students were affected by digital inequality) leaders also mentioned this engagement in other contexts, centred around improving remote provision more generally.

Overcoming common challenges

Leaders in the sector, subject experts, schools, parents and teachers all told us of several common challenges they had experienced in moving to remote education. This section of the report outlines what those challenges have been and some of the ways in which schools have overcome them.

Pupils in the early years and key stage 1

The primary school leaders we spoke to said that they had additional challenges that were unique to their settings that impacted on the design and delivery of their remote education solutions. This was typically due to the age of their younger pupils.

Some primary leaders felt that curriculum alignment had been particularly difficult to achieve. For instance, one leader referred to the content being covered, but often found that pupils’ conceptual understanding was lacking. Due to the activity-based nature of many early primary experiences, remote education was a particular concern where resources for pupils were not commonly available in pupils’ homes. Several leaders also felt that pupils may experience learning loss in their social and communication development – a lack of socialisation with other children was a big concern for most of the primary leaders. However, schools in the focused interview sample had developed numerous ways to provide curriculum coverage:

- ‘stretch’ tasks, such as ‘deeper thinking’ challenges into remote resources, allowing students to challenge themselves and complete extra work

- online tools to facilitate some content delivery, particularly for English and mathematics

- phonics in particular seemed to translate well to a digital medium. Some schools used readily available phonics videos and software. Others recorded their own instructional videos and audio clips for pupils, which pupils could access from a website or digital learning platform

- physical resources delivered to pupils’ homes so that they could still access learning in practical-heavy subjects, such as art and science

- digitally-aided peer-to-peer interaction time so that pupils could maintain their social skills

Many younger pupils have not yet developed reading skills to access written content and instruction. To overcome this, most of the leaders mentioned that teachers were using videos to some extent. One particularly innovative school also introduced a facility for children to upload their own videos as an alternative to providing written answers. However, live lessons were felt by some leaders to be a less appropriate delivery method for their youngest pupils. A common theme identified was that engaging younger pupils was a much more challenging task when done remotely. As one leader put it, ‘it’s impossible to get a bunch of reception children listening [in live lessons]… the novelty will quickly wear off’. A few leaders also explained that they had concerns about the amount of screen-time their youngest pupils were accessing and the impact this may have on their behaviour. These concerns led to most of the primary leaders in the sample using shorter pre-recorded video lessons instead. Leaders were nevertheless still ensuring that any external resources used fitted appropriately with their intended programmes of work.

Every leader talked about how important parental involvement was in the remote education of their younger pupils, no matter whether this was being delivered synchronously or asynchronously. They felt that progression and development of younger pupils was heavily reliant on adult support. However, leaders highlighted several barriers that prevented pupils from getting the support that they required at home. For instance, some parents struggled with accessing content due to literacy issues or a lack of digital know-how. Employers who were ‘not sympathetic’ to children needing to be at home during the pandemic also made it difficult for parents to support their children.

Conversely, a few leaders reported that their assessment processes had identified parents who were engaging too heavily in their children’s learning. They were concerned over how much help pupils were getting from parents (as well as older siblings) in completing work and about the impact this was having on pupils’ knowledge. Similarly, one leader was worried that parents were ‘cherry picking’ their child’s best work for submission to teachers and were unwilling to show what they described as the ‘warts and all’ components needed to accurately check conceptual understanding.

Leaders we spoke to had applied some common approaches to help mitigate some of the concerns mentioned above:

- regular contact with home – this included through telephone calls, texts, emails, home visits, posts on blogs and through websites and social media; a few schools also made regular contact through the delivery of food and breakfast parcels

- providing pedagogical support, through guidance videos, learning supports, prompts and ‘cheat sheets’; some leaders also mentioned providing more formal training, which included to other family members (such as older siblings).

- collecting feedback regularly about what types of support would be most useful, as well as which aspects of remote education were working/not working

- tracking/monitoring parental engagement – one school set up IT accounts for parents and followed up with those not logging on regularly to see what additional support they required

- building confidence for parents – some schools mentioned providing pastoral and emotional support for parents during lockdowns, including expressing regular encouragement that they were doing a great job of home schooling

- holding remote/virtual parent’s evenings

- translation tools for parents with English as a second language

Most of the leaders mentioned that a central aim for them was to develop their pupils’ independence, so as to ease the burden on parents. This included providing training on how to access online platforms and to carry out more complicated tasks, such as photographing and uploading their work. A few leaders also said that, when planning lessons, they considered which activities would require the least parental supervision to help minimise the burden.

Adapting for pupils with SEND

Providing a remote education solution that is inclusive, one that pupils with SEND can meaningfully engage with and benefit from, is a concern for both parents and schools. The YouGov survey found that 59% of parents of a pupil with SEND said that their child has been disengaged with remote learning, compared with 39% of parents of children without additional needs. In terms of progression, schools were also concerned that learning gaps would be greater for pupils with SEND. Leaders are also worried that the negative social and emotional impact of the disruption of remote learning would be more severe for some of these pupils.

That said, the leaders from the 2 special schools interviewed had some specific examples of ways they had adapted their curriculum, teaching and support to the needs of their pupils with SEND. Both schools emphasised the fact that a central focus of their remote curriculum offer for pupils was to make it ‘tangible’ rather than digital. This is because some of their pupils with complex sensory needs found it difficult to engage exclusively with a screen.

Some leaders were also worried about pupils’ loss of routine and familiarity. They therefore developed mechanisms to mitigate this:

- Where pupils had a strong relationship with a teaching assistant, a learning support assistant or other adult, schools arranged for the adult to record voice messages for pupils, so that they could hear a familiar and friendly voice.

- Schools placed importance on a timetable that mirrored the in-person timetable to minimise changes in routines, which can be particularly disruptive to some pupils with SEND (although, for some, asynchronous approaches were more suitable).

- Where one-on-one reading support was not possible, schools sometimes used digital tools, such as assisted reading, to support pupils.

- Some pupils had additional resources or equipment delivered to their family home to ease the transition from school to home and to support their learning. For instance, sensory equipment was sent home for some pupils, so that they could learn in an appropriate environment. In other cases, schools provided equipment to help with muscle development for pupils with profound and multiple learning difficulties. Other schools delivered desks to pupils’ homes so that they had the appropriate means to study.

- Schools gave training to parents to improve their confidence with the specialist equipment their children needed.

However, the YouGov survey data suggests that there is more work to be done. Fewer than half (46%) of the teachers surveyed stated that their school offered additional remote learning arrangements for pupils with SEND.

The overall message was that the most effective solutions for pupils with SEND were bespoke, taking into account the specific needs and circumstances of each individual child. Greater focus and planning will be needed in the future to ensure that the worst effects of learning loss and the physical, social and emotional impacts of lockdown are mitigated for these pupils. Conversely, for some children, there have been benefits to remote education including being able to:

- work more at their own pace

- take breaks when they need rather than at prescribed times

- work in a space in which they experience less sensory overload

Post-pandemic, it would be beneficial to pupils with SEND if schools could consider how they might retain some of these benefits going forward.

Safeguarding

All schools are required, as they usually are, to be active partners in safeguarding children and to make referrals to the local authority where they have concerns about the safety of children at or outside their homes. Online or offline, effective safeguarding requires a whole-school approach. Planning for remote education should include the school’s safeguarding team as part of the planning process. Pupils should be reminded of who they can contact within the school for help or support.

Most schools told us they are checking in regularly with pupils about their well-being. Other schools are going to great lengths to support children and families, for example by delivering food packages and other resources to their homes and checking in with parents as well as children. Schools recognise that when children struggle with the social and emotional impact of the pandemic, their remote learning is likely to be affected. Schools are working to mitigate that.

When it comes to remote education, considerations around protecting the safety of students, particularly in online environments, posed a central challenge since March 2020. Many schools we spoke to stated safeguarding as a key consideration when making decisions about which platforms and digital tools to use for their remote offers. In particular, there were concerns about cameras. Some schools opted to disable cameras in the interests of safety. Others felt face-to-face contact online was fundamental to the well-being of staff and pupils and so made a risk-assessed decision to keep them on based on this. A number of schools made reference to having additional staff present for live lessons. Other safeguarding considerations mentioned less frequently in the interview sample were around data protection (one school leader worried about the sharing of pupil data with ‘big tech’ companies) and keeping screen time at a healthy level. It is, of course, important that schools consider their own contexts and their own pupils when making decisions.

The April 2020 COVID Addendum to the Guidance for Safer Working Practice outlines for leaders and staff what they should consider when assessing the risks around their remote learning solutions.[footnote 26] We have summarised their key points below:

Senior leaders should:

- review and amend their online safety and acceptable use policies to reflect the current situation

- ensure that all relevant staff have been briefed and understand the policies and the standards of conduct expected of them

- have clearly defined operating times for virtual learning

- consider the impact that virtual learning may have on children and their parents/carers/siblings

- carefully consider the context of their own setting and appropriate use of live lessons; consider whether other options might be more suitable in some contexts – for example, using audio only, pre-recorded lessons or existing online resources

- be aware of the virtual learning timetable and ensure that they have a capacity to drop in, unscheduled, on a range of lessons

- take into account any advice published by the Department for Education, local authority, multi-academy trust or their online safety/monitoring software provider

Staff should:

- adhere to their establishment’s policy

- be fully dressed

- ensure that a senior member of staff is aware that the live lesson/meeting is taking place and for what purpose

- only record a lesson or online meeting with a pupil where this has been agreed with the headteacher or other senior staff, and the pupil and their parent/carer have given explicit written consent to do so

Adults should not:

- contact pupils outside the operating times defined by senior leaders

- take or record images of pupils for their personal use

- record virtual lessons or meetings using personal equipment (unless agreed and risk assessed by senior staff)

- engage online while children are in a state of undress or semi-undress

Leaders and staff should familiarise themselves with the full document (this sample is taken from section 24a).

In some cases, staff may need to speak to children one-on-one, for example teaching assistants might be providing extra support to children with SEND. Where this is the case, staff should ensure that parents are aware, and invited to, any one-to-one interactions with pupils and that those interactions are necessary (for example, for teaching assistants supporting SEND children). Senior staff should also be aware and have the option to join. Staff should also be clear about expectations around behaviour, for example, a ‘classroom standard’ of behaviour is expected from all participants.

For further advice and information, schools should familiarise themselves with guidance from the Department for Education.[footnote 27]

Teacher well-being

Workload increase was a real concern for many at the outset of the pandemic and is an ongoing, if not increasing, challenge. In particular, mixed delivery situations were seen as posing a threat to staff well-being. It was reported a number of times that staff were required to deliver content to students both in and outside of the classroom simultaneously. Without an appropriate blended learning model, this was regarded as a particularly challenging situation. In addition, creating videos, live lessons and planning all take time, especially when needed at short notice. Leaders were also conscious of the social and emotional impacts of the pandemic, and of staff getting to grips with delivering content digitally where they perhaps lacked the skills or confidence to do so.

Encouragingly, many school leaders appeared to be making decisions through (at least in part) the lens of staff well-being. Every leader in our focused interview sample mentioned their desire to preserve staff well-being. Some offered some practical examples of how they did so:

- regular staff meetings, with consideration given to not keeping staff tied up in too many meetings – a few leaders mentioned how they were now doing staff meetings online

- making use of existing external resources, rather than creating everything from scratch; the caveat here is that some time needs to be spent on aligning those resources with the subject or school curriculum

- regular continual professional development (CPD), as well as readily available CPD and other support materials – often these were accessible digitally, so could be drawn on at any time staff wished

- increased time allocated for planning and reflection; some leaders mentioned that their staff were planning remote lessons as a team

- when making decisions about digital learning platforms/software/other resources, taking into account which solutions would be most conducive to a manageable staff workload

- creating clear and widely accessible (to both staff and parents) guidance documents to ease both parental and staff anxiety about ‘what is actually happening’

That said, a few leaders mentioned that they felt ‘it was important not to overburden staff’ but did not offer concrete instances of how and when they had done this. This may suggest that staff well-being needs to take a more central role in future decision-making in some settings. We saw from the interim visit evidence that leaders and decision-makers themselves have reported low levels of well-being and high workloads. This needs to be taken into account. Some schools have also been more impacted by COVID than others, depending on areas where outbreaks were more or less prevalent in autumn. This means that some schools were able to plan while others were dealing with regular COVID-19 cases among pupils or staff.

Training on remote education resources or tools

One of the challenges of remote education is the need for teachers to be trained in both the use of the technology solution planned and adapting the curriculum and their teaching approaches for a remote education environment. Schools also need to provide information for pupils and parents on using the technology or learning resources available. The evidence from the interim visits indicated that training for remote education has evolved: increasingly, schools are expanding their training to how the curriculum should be delivered remotely. However, in a small number of schools, staff had received no formal training in relation to remote education.

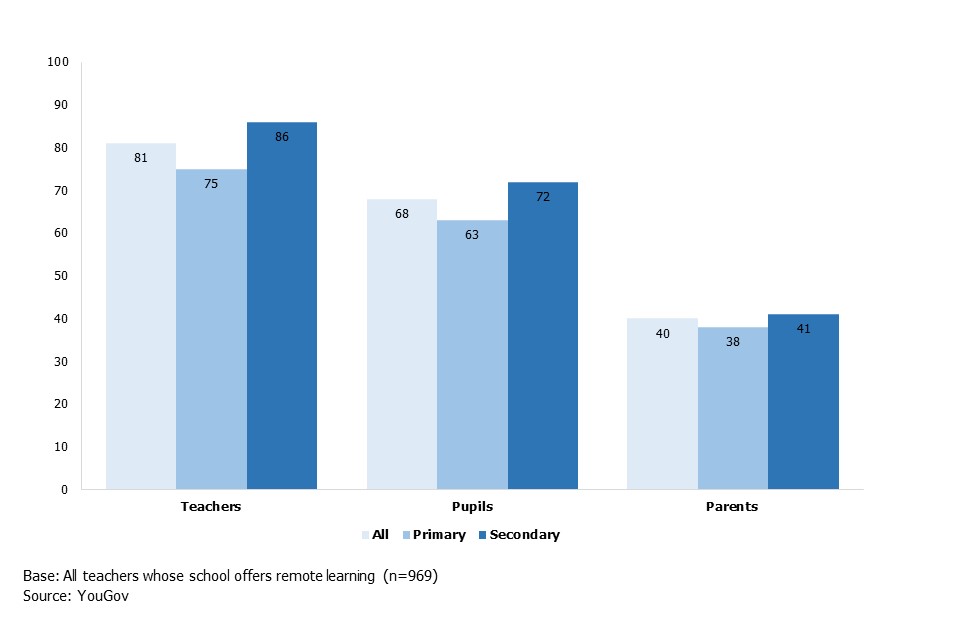

We also surveyed teachers about the extent of training or provision of learning resources for different groups and received mixed results:

Figure 9: Teacher responses to the question ‘Has your school offered training or learning resources on how to use remote education tools to any of the following?’ (percentages that said ‘yes’)

Download the data used in figures (CSV format).

Leaders who have overcome more of the barriers associated with remote education have broken down the elements of learning to teach remotely, helping children learn remotely and communicating effectively with parents who support the whole process.

Many of the leaders from the focused interviews discussed training regarding improving teacher and/or pupils’ skills in accessing digital platforms and remote learning software. However, as with the interim visit findings, not all had moved beyond this scope. Several leaders mentioned that teaching and learning approaches were widely discussed, but formal training in specific pedagogy for remote education had not always been well developed. For instance, a few leaders noted that virtual classes should mirror live classroom activities, so no specific pedagogical training for the medium had taken place.

However, most of the leaders from the focused interviews had moved beyond this starting point. They explained that while ‘training staff to use technology came first, pedagogy came later’. They typically argued that a ‘different pedagogy’ is needed to enable better use of language, explanations and active participation from pupils. A few schools had developed resources, such as a ‘pedagogical practice newsletter’, to share good practice across their departments or their multi-academy trust’s subject communities. Several said that they had developed their training on pedagogical approaches from freely external video lessons and materials available from the Education Endowment Foundation.[footnote 28]

Most of the leaders mentioned that they had found ways to engage parents, as well as children, in using their remote education solution. This was particularly the case with the primary school leaders spoken to. Many had created surveys, videos and newsletters to help communicate the design of their remote solution and expectations for pupils to parents. As an added benefit, leaders suggested that this improved relationships with parents and built trust.

Future benefits to remote education

Leaders from both the focused reviews and interim visits did not always regard remote provision as an entirely inferior or temporary measure but expressed a desire to retain some aspects of their remote education provision when their schools return to ‘normal’ modes of teaching. Having spent time and resource over the last 10 months developing new systems, they were able to identify some positive benefits that may aid pupils learning in the future. These included:

- video lessons from subject experts to provide teacher cover (this has some potential workload benefits)

- video lessons where there are subject specific teacher recruitment and retention issues

- supporting anxious or excluded students off site or in other on-site learning areas

- availability of pre-recorded lessons for revision purposes or where pupils miss lessons due to illness

- provision of teaching and learning during snow days, extended periods of pupil illness or absence, holidays, interventions for over and underachievement and potentially INSET days, to minimise learning loss (eg ‘We have lost snow days forever! May upset students.’ and ‘Huge opportunity to make sure that not a single day of a child’s education is lost to events beyond their control.’)

- improvements to homework delivery

- giving pupils the means to manage aspects of their own learning. Several primary school leaders in the interview sample felt their pupils had gained independence from their remote learning experiences. Many referred to engaging in discussions around metacognition with their learners – this may have positive benefits for these pupils’ future understanding of their educational journey

For some pupils with SEND, there were some notable positive opportunities posed by remote learning. Different platforms could be used to cater for different needs and overcome issues that may have previously excluded pupils from parts or all of certain lessons. Pupils with sensory overload issues, for example, could be taught remotely for a portion of a lesson and then reintroduced to the main class later on when the environment had ‘calmed down’.

Many schools also mentioned additional future-oriented benefits that fell outside of the area of pupil learning but still offered exciting prospects for an improvement to schools’ overall offer. These included:

- up-skilling (both of staff and pupils) – teachers gaining digital proficiency had led to the potential for an improved learning experience in the future

- the social aspect of remote provisions, particularly in the context of improving communication/relationships with parents, carers and families of pupils. Schools generally all expressed that relationships with parents had been bolstered and parents felt they were more involved in their child’s learning. Many schools stated that they felt remote learning had created or strengthened the ‘community’ or ‘team-like’ nature of their schools’ environment

- safeguarding: some schools said that it was easier to safeguard vulnerable children because they have found it easier to communicate with them more regularly

Conclusion

Our evidence shows that current remote education solutions across schools vary considerably in design. There does not appear to be a perfect one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, school leaders are taking into account their specific local contexts to design flexible remote solutions for pupils, staff and parents.

From speaking to those leaders with maturing systems in place, we can infer the following general overview:

- The curriculum should not be seen as a separate entity. Remote education is just another way for the planned curriculum to be delivered. Therefore, principles of good curriculum design still apply in maintaining the rigour of a wide and deep curriculum.

- Pupils still learn in the same way, so principles of good pedagogy, such as the importance of practice, retrieval and feedback, need to be developed in any remote system.

- Assessment is an area of development, but the evidence indicates that pupil engagement is not the same as learning. Pupils’ conceptual understanding still needs regular assessment to ensure that they progress through the curriculum.

- While elements of remote education have proved useful, poorer pupil engagement, access to appropriate resources, staff well-being and the pressure remote education places on families and parents can remain real barriers to pupils’ learning and development.

Clearly, the message from the evidence is not that we should not be doing remote education. It is an imperfect but necessary substitute in mitigating against learning loss where classroom teaching is not possible. Pupils are still learning more than they would without any school support.

Within this report there are some clear examples of how school leaders are developing their systems and providing solutions for the barriers that exist. We hope this provides helpful advice for other leaders and staff with the future refinement of their remote education solutions.

Annex: Methods

Ofsted carried out several strands of research work during the summer and autumn terms 2020. We had 3 main research questions:

- How have schools adapted their teaching in response to COVID-19 (coronavirus)?

- What barriers exist to creating a remote education solution that provides children with the same quality of education they would receive in the classroom?

- What does a good quality remote education look like, in proportion to the barriers outlined above?

We carried out this work to inform and improve our own knowledge and understanding of remote education. We also wanted to use our resources to provide national insights to the education sector to help schools plan and review the quality of their own remote education solutions.

We gathered the following forms of evidence between summer and the end of 2020.

Rapid review of the literature on digital remote education

First, we carried out a review of current research and literature to determine some core principles of quality digital remote education. However, the existing evidence base for remote digital education in schools was slim and what we found was similar to what the Education Endowment Foundation had found previously.[footnote 29] Where relevant, we have included references to other research in this paper.

Semi-structured and structured interviews with professionals

Semi-structured interviews with 4 leading experts

The rapid review of literature was supported by interviews with 4 experts who were particularly invested in teaching and learning, and digital education. Our senior research lead on this project carried out these interviews in July 2020. Participants were asked about:

- what they considered to be the main features of high-quality digital remote education

- how digital technology could support teaching during the pandemic

- what the barriers were that existed in delivering this

Their evidence gave us some working assumptions that we used to help design the questions in the interim visits, focused interviews and questionnaire work that followed.

Semi-structured interviews with school leaders during interim visits

The interim visits we made during the autumn term 2020 included questions for leaders on the remote education that each school was providing. In total, we analysed the evidence from 798 of these visits.[footnote 30]

Semi-structured interviews with remote education leads in schools

We also selected a purposive sample of 25 schools in which we carried out in-depth semi-structured interviews with the main decision-makers (referred to as ‘leaders’ in the body of the report) on remote education in each school. Because our purpose was to define quality aspects of remote provision, we selected participant schools on the following bases:

- that they already had a developed approach to curriculum development and delivery in place

- available information suggested that their remote education solution was sufficiently mature

The sample consisted of:

- 11 primary schools

- 11 secondary schools

- 2 special schools

- 1 pupil referral unit

Eight of these had received an interim visit earlier in the autumn term. We designed these interviews replicating aspects of a methodology we previously applied in phase 2 of our curriculum research.[footnote 31]

The interview questions were designed by the senior research lead and two lead Her Majesty’s Inspector (HMI). Twenty-six Ofsted inspectors carried out the interviews. Each interview was carried out online by 2 Ofsted inspectors. They shared the responsibility of asking questions and taking notes to ensure the evidence collected was sufficiently detailed. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes.

Structured interviews with teachers, commissioned through YouGov

We commissioned YouGov to carry out in-depth interviews with 20 of the teachers who responded to a questionnaire (see below). These interviews explored how remote learning was being developed and implemented in these teachers’ schools. YouGov also asked about the perceived impact of remote education on children’s learning. We selected teachers who opted into this follow-up study according to a mix of school type, school phase, location and the proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals on roll.

Teacher and parent questionnaires

We commissioned YouGov to carry out separate teacher and parent questionnaires. The objective of this work was to give us supporting evidence to the interim visit data collected by inspectors. We particularly needed this because the interim visit methodology meant we were less able to engage with teachers and were not able to engage with parents at all. The quantitative data from this work also gave us evidence on the strengths and weaknesses of remote education being delivered nationally.

For both questionnaires, we developed the content of an online survey with YouGov. The survey was open for 2 weeks in late November and early December. In total, 1,003 teachers and 2,020 parents responded. The figures used in this report have been weighted and are representative of:

- all parents in England by family type, age of family reference person, social grade and region

- all teachers by school type, teaching level, region, gender and age

Focus groups

With our own inspectors

Our regional director for London held several meetings with groups of inspectors, including Senior HMI, across all our regions. These were for inspectors to share information and practice that they had discussed with school leaders during the interim visits. They also shared their observation and evaluation of the remote education practice that school leaders had told them about.

With 7 digital leaders from EdTech demonstrator schools