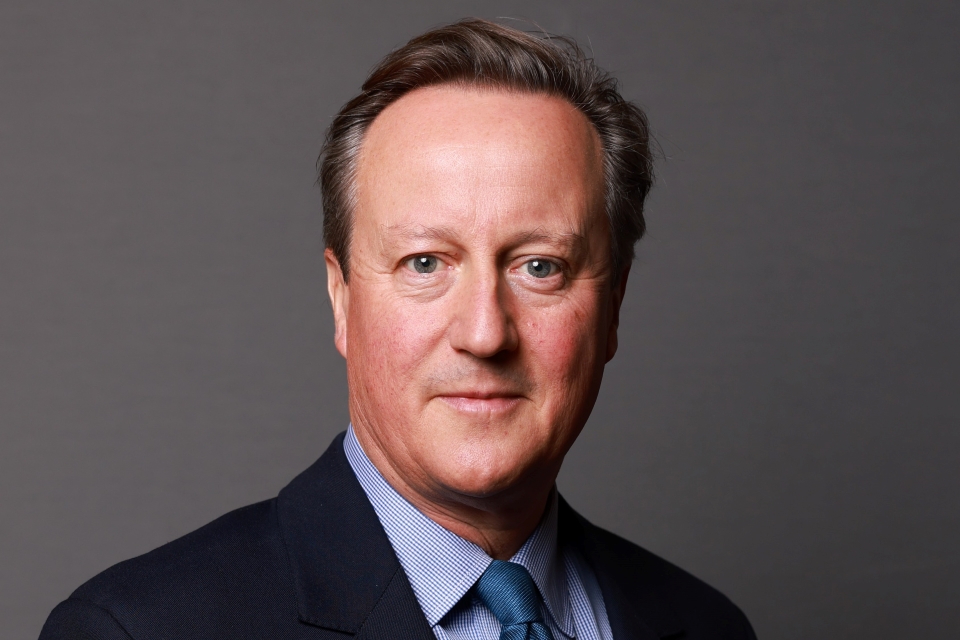

Reopening of the Imperial War Museum: David Cameron’s speech

The Prime Minister gave a speech at the reopening of the Imperial War Museum London.

When I launched our plans for the First World War centenary, I said that the renovated Imperial War Museum would be the centrepiece of our commemorations.

And what a fitting centrepiece this is – a national focal point in which we can all take great pride.

When it was first opened in 1920, this museum opened its doors to those who had experienced the war first-hand.

To mothers who had lost their sons, women who had lost their sweethearts, soldiers who had lost their health and a nation that had lost a generation.

Today, not a single person who visits this building will have served in that conflict.

Very few will remember it – there are only a handful of people still alive in Britain who were aged 10 or more in 1914.

That gives this museum a huge challenge: to bring that past to the present; to turn the sepia to technicolour.

Looking around today, it’s clear you have absolutely risen to that challenge.

You have created something which brings home the reality of the war, the reasons we fought, and why it is relevant to us today. And I’d like to say a word on each.

First, the film footage, photographs, letters, diaries and artefacts truly convey the reality – the sheer enormity – of the First World War.

They show us that this conflict wasn’t just fought on the Western Front. It was fought in the deserts of the Middle East, the plains of Poland, the frozen mountains of Austria, and beyond.

It wasn’t just fought in the trenches. It was fought in the sky, on the seas – even underground, through miles of tunnels.

It wasn’t just Britons who secured Allied victory. It was Indians, Canadians – even a Chinese Labour Corps.

And it wasn’t just men on the frontline. It was boys, too – many of them just a few years older than my own children.

These galleries also show the realities of war closer to home.

And here we can see fragments of shells that rained down on Scarborough; the camisole of a woman rescued from the passenger ship, the Lusitania; even the remnants of zeppelins that bombed London.

Second, this museum helps us think again about the reasons why we fought.

In the century since this conflict began, too many have cast it as a pointless war. One fought by young men who didn’t know why they were fighting or what the objective was.

And that impression is only made more vivid by the war poets and writers who wrote of the colossal waste of life and how futile it all felt.

But we should never forget that those who volunteered and fought believed they did so in a vital cause: to prevent the domination of Europe by one power; to defend the right of a small country – Belgium – to exist.

They were right to believe these things, and that is something that I believe should be remembered and paid tribute to – and this museum is an important part of that.

Third, these galleries succeed in making this war relevant 100 years on.

For me, it’s personal.

Six of my relatives died in the First World War and many others served. All around the museum I see flickers of their fates.

Alastair Geddes died in 1915, and the museum has a wallet belonging to a fallen comrade from his regiment.

Hoel Llewellyn was in the Tank Corps, and on display here we have a Mark V tank, the type his Battalion would have used.

Ewan Cameron was gassed, but survived.

And on display we have a soldier’s shrunken glove, showing on clothing what the poison did to soldiers’ organs.

These are just some of my family’s stories; I’m adding others to the museum’s ‘Lives of the First World War’ digital archive, and I would encourage everyone else to do the same.

Because with these family links, I’m not unusual.

We are all descendants of the Great War – either directly or indirectly.

Most of us will have ancestors who fought, many from what is now the Commonwealth; the majority of us will live in a place that lost men; just 50 of Britain’s 17,000 parishes welcomed all of their heroes home. And every single one of us is indebted to that generation – because their legacy is our liberty.

There are certain places in the world where you can feel the magnitude and the solemnity of the First World War, like the Menin Gate, covered with the names of 55,000 who fell but were never found and like the cliffs of Gallipoli, overlooking the beaches of those doomed landings.

The Imperial War Museum is one of those places – showing us so powerfully what our ancestors went through and its relevance to us today.

So thank you once again to everyone involved.

You have created something fitting and lasting – something of which we can all be proud.