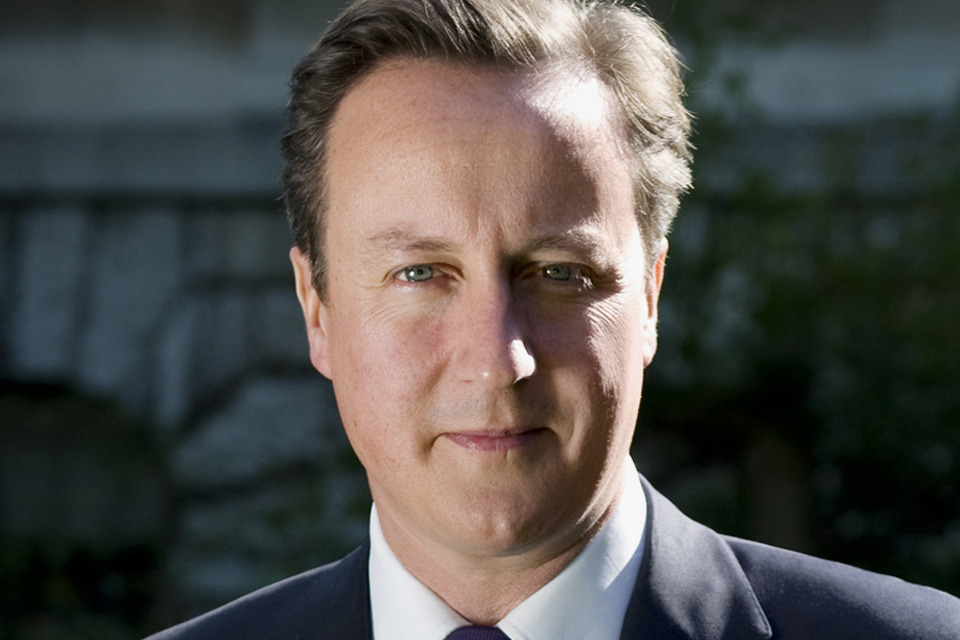

PM at 2015 Global Security Forum

David Cameron discussed current security challenges at GLOBSEC 2015, held in Bratislava.

We meet at a time when Europe faces extraordinary challenges. There’s the threat of ISIL-inspired terrorism - luring our young people to fight in the Middle East and casting a shadow of terrorism over us at home.

There’s the Russian-backed aggression in Ukraine - attempting to redraw Europe’s borders and sowing fear among those people and nations that dwell on Russia’s periphery.

There’s the combination of the failed states and criminal gangs in North Africa - driving desperate migrants across the Mediterranean in the hope of reaching our shores.

That’s to say nothing of the risks of cyber-attacks, of climate change and of global pandemics that threaten us all.

Britain’s commitment

Let me start by saying this: Britain is committed to Europe’s security.

I speak as Prime Minister of a country whose military aircraft are flying patrols over the Baltic; whose troops are training Ukrainian soldiers; whose Royal Air Force is delivering the second highest number of air strikes over the terrorist-held territory of Iraq; whose soldiers, medics and aid effort are combatting Ebola in Sierra Leone, and preventing its spread, and whose Royal Naval amphibious assault ship, HMS Bulwark, has pulled nearly 3,000 migrants from sinking dinghies that have set off from Libya. Our soldiers, our airmen, our sailors are out there every day, doing their job.

They are part of a long tradition: Britain has never stood by when Europe’s security is in peril. This year we mark the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Europe from Nazism, in which my country played a leading part.

Last year, we marked a quarter of a century since the Iron Curtain was torn down and freedom rolled across the continent. In the decades of division which followed 1945, Britain always stood firm in defence of liberty.

And we do so now. The challenges we face today are large and they are many. But I remain confident we will meet them. I believe we’ve succeeded in the past when we’ve stood by the values that have made European nations strong and successful. Democracy, freedom of speech, free enterprise, equality of opportunity, human rights these are the things that unite us. And history shows that we succeed when we stand up for them – and when we do so together.

Tyranny, fascism, hatred – they have always come off worst when confronted by our determination to defend our values and our way of life.

Other voices

But we should recognise the dangers today from the people who say that this time things are different. This time, in the case of Russia, they say that what’s required is understanding rather than condemnation so we should engage with them instead of imposing sanctions.

In the case of terrorism, they say that the rise of ISIL shows the dangers of getting involved so we should turn our backs on the Middle East. In the case of migrants being tricked and trafficked, they say this is something that should be managed rather than solved, so we should carry on allowing them to attempt this perilous crossing. I think these arguments are profoundly wrong. And I am very clear about the principles that need to be applied.

Economic strength

First, we need to be clear about the primacy of economic strength and success. Without prosperity, there is no security.

It’s simple: if our economies in Europe are not strong, then there won’t be money to spend on defence or on addressing problems in failed states around the world or on providing our law enforcement with the tools they need to keep our people safe.

With the second largest defence budget in NATO, and the largest in the EU, Britain is investing heavily in modernising the defence of our own nation and our forces available to the Atlantic alliance.

Over the next 10 years we are spending over €220 billion on the latest military equipment – the largest 2 aircraft carriers our Navy has ever seen, new Hunter Killer Submarines, state-of-the-art air defence destroyers and new frigates. Forces to protect our own country. Forces to make sure we can honour our commitments to our allies.

And let us be clear: this is only possible because we have a strong and stable economy. We’re only able to buy this equipment and upgrade our capabilities because we’ve taken the difficult decisions on our public finances and stuck to a long-term economic plan. But economic stability doesn’t mean we should rest on our laurels. We must go further.

For a start, in Europe we must drive forward the completion of the single market. And we must open that market up to trade around the world. Britain is a trading nation – we want to reach out to other countries and make connections across continents.

Trade is perhaps the oldest form of cooperation known to man. Open markets, it is rightly said, open minds. We believe that building bridges through trade provides prosperity for working people at home and security abroad. That’s why we want to go further and open up European nations to free trade around the world.

That means more trade with India, with Latin America. It means working towards an EU-China free trade agreement. And it means, above all, moving rapidly to agree a free trade agreement with America that sees trade flowing even more freely across the Atlantic.

Clarity

The second part of the approach we need is clarity. In ISIL we have one of the biggest threats our world has faced. We need to be clear about the nature of that threat. The scale is formidable and growing. It stretches right across this continent with young people leaving Belgium, Sweden, Austria, France and Britain for the Middle East.

The nature of the threat is grave. These are young people, boys and girls – leaving often loving, well-to-do homes, good schools, bright prospects – travelling thousands of miles from home to strap explosives to their chest and blow themselves up and kill innocent people; to live in a place where marriage is legal at the age of 9 and where women’s role is to serve the jihadists; to be part of a so-called state whose fanatics are plotting and encouraging acts of despicable terrorism in the countries from which they have come.

It’s what we’ve seen this week with the youngest suicide bomber in our history in Iraq. It’s what we may have seen with 3 women and their young children who went to Saudi Arabia to perform their pilgrimage and who are thought to have gone to ISIL territory.

Only if we are clear about this threat and its causes can we tackle it. The cause is ideological. It is an Islamist extremist ideology one that says the West is bad and democracy is wrong that women are inferior, that homosexuality is evil. It says religious doctrine trumps the rule of law and Caliphate trumps nation state and it justifies violence in asserting itself and achieving its aims.

The question is: how do people arrive at this worldview?

How does someone who has had all the advantages of a British or a European schooling, a loving family, the freedom and equality that allow them to be who they want to be turn to a tyrannical, murderous, evil regime?

There are, of course, many reasons – and to tackle them we have to be clear about them. I am clear that one of the reasons is that there are people who hold some of these views who don’t go as far as advocating violence, but who do buy into some of these prejudices giving the extreme Islamist narrative weight and telling fellow Muslims, “you are part of this”.

This paves the way for young people to turn simmering prejudice into murderous intent. To go from listening to firebrand preachers online to boarding a plane to Istanbul and travelling onward to join the jihadis. We’ve always had angry young men and women buying into supposedly revolutionary causes. This one is evil; it is contradictory; it is futile – but it is particularly potent today.

I think part of the reason it’s so potent is that it has been given this credence.

So if you’re a troubled boy who is angry at the world, or a girl looking for an identity, for something to believe in and there’s something that is quietly condoned online, or perhaps even in parts of your local community, then it’s less of a leap to go from a British teenager to an ISIL fighter or an ISIL wife, than it would be for someone who hasn’t been exposed to these things.

That is one of the factors.

There are others – not least questions of national identity and making sure young people in our country feel truly part of it – and we need to deal with all of these things. But if we are to really tackle this threat, we need to confront extremism in all its forms, violent and non-violent, to stop our young people sliding from one to the other.

We also need to be clear about the ideology’s methods. It may be medieval in its outlook, but it is modern in its tactics with the internet as the main tool to spread its warped worldview. Being clear about these things will allow us to develop the powers we need to root out this poison.

And being clear where responsibility does and doesn’t lie is also key. Too often we hear the argument that radicalisation is the fault of someone else. That blame game is wrong – and it is dangerous. By accepting the finger pointing – whether it’s at agencies or authorities – we are ignoring the fact that the radicalisation starts with the individual and we would be in danger of overlooking many of the ways we must try to stop it at the source.

We need to treat the causes, not just the symptoms. Of course, we will do everything we can to help the police and intelligence agencies to stop people travelling to Syria. But we mustn’t miss the point: they are not responsible for the fact that people have decided they want to go.

In Britain we are strengthening the ability of the police and security services to disrupt terrorist plots, giving them all the tools they need. And we are working with the internet industry to tackle terrorist propaganda – removing over 90,000 pieces of material since 2010. We are also working with other EU member states to set up an EU-Internet Referral Unit, based on the British model – and that will be up and running from next month.

And we’re doing these things because we acknowledge just how widespread, how complex and how dangerous this threat is.

Uncompromising

Third, we must be uncompromising about the attempts to redraw Europe’s borders by force. We are clear: Crimea and the Donbas are part of the territory of Ukraine. They were recognised as such by Russia and by the rest of the international community. What Russia has done and continues to do is in breach of its own obligations under international law.

Our first task is to make diplomacy succeed. We must be uncompromising in insisting that the Minsk agreements are fully honoured by all. We must also be uncompromising in our support for Ukraine. President Poroshenko’s government deserves support to deliver vital political and economic reforms, and we must provide that support. Britain is doing so through our Good Governance Fund, and we are looking at what more we can do and we should be clear: the Ukrainians are victims, not aggressors.

Confidence

Fourth, we need to be optimistic and ambitious. This is particularly the case when it comes to our ability to address failed states. We are currently seeing unprecedented migration from troubled states in Africa and the Middle East on Europe’s southern flank.

It is a tide of humanity desperately seeking a better life.We must of course do what we can to help those in danger of losing their lives at sea – and we are. Britain will always meet its obligations to provide refuge for the most vulnerable. We already participate in the UN’s programme to resettle refugees who have fled from their home countries, including those affected by conflict or civil war.

And we also set up our own scheme for particularly vulnerable people fleeing the conflict in Syria, including women and children at risk who couldn’t be protected in the region. And today I can announce that we will work with the United Nations to modestly expand this national scheme so that we provide resettlement to the most vulnerable fleeing Syria – those who cannot be adequately protected in neighbouring countries.

But we won’t resolve this crisis unless we do more to stop these people leaving their countries in the first place; until we break the link between boarding a boat and settling in Europe. This is where we need to work together as European nations, to tackle the root of the problem, not merely alleviate its symptoms.

Again, clear thinking is needed. All the evidence shows that the most important factor in someone’s decision to make this journey is how they will be treated in terms of being allowed to stay in Europe. So schemes of relocation don’t solve this problem.

What works is what the Spanish did when migrants arrived in their thousands in the Canary Islands. They worked with the countries people were coming from and travelling through. They made sure they had the right police, coastguard, aid and governance resources to stop people taking the decision to leave. And they made sure that the economic migrants who did end up leaving were returned safely.

We need to do the same – on a larger scale. We should be leading the world on promoting development and helping our international partners build stronger institutions. Now despite difficult economic times, Britain has kept its commitment to spend 0.7% of our GDP on aid. It’s the right thing to do to build prosperity for the world’s poorest – and it’s the right thing to do to help stabilise and secure countries in the long run – protecting our security here in Europe.

Conclusion

From Eastern Europe to the Middle East, these security threats, they often have one thing in common: a failure of governance in other countries.

It is the failure of governance in African states that leads many to want to leave. It is in part the failure of Libyan governance which has allowed the traffickers to profit from human misery. It was the failure of Ukrainian governance in the years before 2014 which led to discontent and instability. It’s the failure of governance in the Middle East which has left a vacuum within which ISIL can proliferate.

The fear of the family in eastern Ukraine listening to the Russian shells get closer and closer to their home and the desperation of the family in Eritrea willing to risk everything in order to reach the edge of Europe – all this human tragedy comes back to a failure of governance in these countries.

So let us now show that we can deal with this.

Let us show that we understand the primacy of economic security and political stability, that we are clear about the threats, that we’re uncompromising in our response, and we’re confident of our ability to address failed states because if we do all those things – and I have no doubt that we can – we will be able to deal with these threats and we will successfully protect the security of all our nations.

Thank you.

Transcript of Q&A

Question

Hello. I have two questions for you. You mentioned spending on NATO, so what about the 2% budget that would be necessary to continue with your spending on NATO? And then secondly, you evoked the idea of economic stability. How would a British exit from the European Union affect Britain’s economic stability and therefore its ability to provide the defence that’s required?

Prime Minister

Okay, well first of all, on NATO and spending, Britain is a country that has continually met its 2% spending commitment. We met it last year. We’re meeting it this year. We have a spending review that we’re conducting now and we’ll announce the conclusions of that in the autumn. I think when you look around Europe the tragedy is so few countries actually come anywhere close to meeting 2%. It’s good that countries, including many in this part of Europe are now increasing their spending to get closer to the 2%, but the 2% is an obligation on all and particularly at – in Wales at the NATO Summit – we made a particular point about the emphasis on those who are way lower than 2%, making up the spending.

What I set out in my speech today is important as well because, as well as the level of spending, what actually matters is what you’re spending the money on. And the most important thing of all is that you have deployable equipment, usable equipment, and modern equipment. It’s no good having a large standing army if it doesn’t actually have the equipment to be able to deploy it rapidly to trouble spots and to protect your vital interests in the world. So that investment of £160 billion, over €220 billion, over the next ten years is particularly vital.

As for Britain’s place in Europe, my aim is to secure Britain’s place in a reformed European Union. I’m a great believer that, if you have a problem, if you have difficulties, which Britain has had with the European Union, then the best thing to do is to have a strategy and a plan for overcoming them. I think people have looked at the European Union in recent years and have seen, instead of it being a source of growth and jobs and innovation, there’s been too much economic stagnation. So let’s fix that and that’s very much part of my plan. People in Britain have seen that sometimes the European Union seems to want to get involved in issues that are for nation states, so let’s try and fix that, have a plan and then hold that referendum. And I’m confident that my strategy, that my plan, will deliver this outcome of Britain in a reformed European Union.

And I make this point here because I think this reform will actually be of benefit to the whole of Europe. We all need Europe to tie up to the fast growing economies of the world and to sign these trade deals. We all need Europe to invest in completing a single market and digital and services in energy so that we’re source of growth and investment and jobs rather than a source of stagnation. So yes this programme is important for Britain and our membership of this organisation, but I think it’ll bring real benefits for others as well.

Gentleman here in the middle.

Question

Thank you Mr Prime Minster. You mentioned something very important about the new plan for resettling vulnerable Syrian refugees out of neighbouring countries, can you provide us some more details about this, and specifically looking at the larger picture on Syria, not only on the ISIL aspect but the broader conflict in Syria, what is your position on any kind of announcement that you can make today? Thank you.

Prime Minister

Okay. First of all on what Britain and other countries can do to resettle vulnerable families, this is only ever going to be a very small part of what needs to be done. What we have done in the past is measured in the hundreds of families that are particularly vulnerable, that can’t be looked after in the region, as I’m saying today. We think that that can be modestly expanded, but let’s be frank about it – the situation with millions of refugees and displaced people inside Syria, in Lebanon, in Jordan and elsewhere – this needs a massive humanitarian aid effort of money going into region, and Britain is the second largest bilateral aid donor to make sure those people can have the shelter and the food and the protection that they need.

But the long-term answer cannot be for people to live in camps year after year, it’s got to be to go back to the countries they came from, which leads to your second question, which is, what is the route to a more secure Middle-East, particularly in Syria and Iraq? Well, we could spend all day on that, but I would just say in a sentence both countries need the same thing, which is a government that can represent all of their people. It is this failure of governance that I talk about that’s at the heart of the problem. Why did ISIL take hold in Syria and then Iraq? Well because Bashar Assad was one of the greatest drivers to ISIL because of the butchery of his own people. Why did ISIL succeed in taking hold in Iraq? Because Maliki was not a prime minister for all of the Iraqi people, Sunni, Shia and Kurd.

So while it will be a very complicated and difficult path to have a new Iraq and a new Syria, the end goal is simple: you need a government that can represent all of the people. Then you’re more likely to have the peace and stability required and people can return. Until then, Britain will continue to fulfil its humanitarian and moral obligations by being one of the biggest aid donors to the region and making sure people are given a place of safety.

Sir?

Question

It was great hearing you talk so toughly about Putin’s attack on Ukraine, and I’m sure there are many people in the room who were very glad to hear that, but Britain’s stance toward Mr Putin would be much more effective if rich Russians weren’t finding Britain such a wonderfully convenient place to buy property. Look, I mean, the city of London has the reputation in Russia as being the place you need to go if you want to launder a really large amount of money. Smaller amounts go to Cyprus or somewhere like that, but if it’s a really big amount go to London, because the banks and the lawyers and the accountants there are the really good experts at listing dodgy companies and putting large amounts of money into co-ops.

Prime Minister

Well let me take the two bits of your questions. First of all, London as a financial centre – I would argue that we actually have some of the toughest rules on money laundering on tax evasion anywhere in the world. In fact we are the first country in the world – and the head of the OECD is nodding at me as I say this. He’s sitting two down from me. We are the only country in the world that has pledged to introduce, and is on the way to introducing, a register of beneficial ownership so you can see who owns every company. I put that on the agenda at the G8 in northern Ireland, Britain has taken the first step, every other G8 country has signed up to having an action plan to put in place similar arrangements, so I don’t accept for a moment that London is somehow backward when it comes to being a proper policeman on these issues.

I would also argue, and I would hope that my fellow prime ministers and presidents from Central and Eastern Europe will back me up on this, when it comes to arguing for sanctions against Russia because of the action taken in Ukraine, Britain has been in the lead. We have been the ones arguing time and time again, we have to take a tough and united response, and we’ve played an important role in keeping the EU and the United States together. Now, in the end there is no military solution to this conflict, so the best thing that Europe and America can do is a very strong response to Putin and to Russia to say that, unless you fulfil the Minsk agreements, those sanctions will not be relieved, and in fact, if you go further, if you encourage another grab of territory in Ukraine, more sanctions will be put in place. So I think Britain has played a very strong role in spite of the fact that this might lead to reduced trade flows or investment flows in terms of Russia.

We know that there is a much more important long-term consideration, and I would make this point to anyone in the European Council who thinks perhaps now is the time to take the foot off the gas. Of course there might be some short term relief in terms of relieving sanctions, but the longer term loss to Europe of saying it is okay to re-draw boundaries by force, that it’s okay to give up the rules of the international road, that would be disastrous for Europe, and that’s why the argument for tough sanctions against Russia has won the day and I believe will continue to win the day in the European Council next week.

Gentleman back here.

Question

Good afternoon. Prime Minister, when a small but significant part of this Globsec community met last December at Château Béla there was considerable frustration that you were focusing too much on your home audience with the Europe agenda. Do you now have the confidence that you are bringing a convincing agenda on Europe to this region, which is a natural ally on many agenda items on Europe, and what response are you getting from your counterparts?

Prime Minister

Well first of all I would say that having an agenda of wanting to reform and renegotiate Britain’s place in Europe doesn’t exclude you from making important breakthroughs on other foreign policy priorities. As I said at the beginning of my speech, you know, Britain is seriously engaged in a number of activities, whether it’s flying air policing missions over the Baltic. We’re the second largest participants in the coalition against ISIL in Iraq. We took on the responsibility really for the whole of Sierra Leone and dealing with the Ebola crisis, just as America took on the whole of Liberia in terms of what they were doing dealing with the crisis. So I don’t accept that you can either have a European strategy or a global strategy. A country like Britain, that is members of the G8, the G20, the EU, NATO, the Commonwealth, we should be using all the networks and all the links we have to make sure that Britain is a successful trading and investing nation right around the world.

In terms of how my EU reform agenda is going, look it’s going to be hard work to convince everybody that change is necessary, but I’m absolutely convinced that it’s right. I think it’s right for Europe, we need more competitiveness. We need fair rules between those that are in the Euro and those that are out of the Euro. We need to crack this problem of large migratory movements around Europe, far bigger than what the founding fathers ever envisaged, and I think the right way to do that is greater determination of national welfare systems. And also I would argue we should deal with those issues that Britain feels particularly strongly about in terms of our European membership, that we’ve always believed that this is about joining an association of states that cooperate and work with each other rather than believing that the final destination is some federal state or European state. Britain has never believed in that. We don’t believe in that. That is not the reason for our membership, and I want that made explicit, which is why I make such attention to these words: ‘ever closer union’. This is not what Britain seeks.

When it comes to our membership, we’re the first to argue for completing the single market, we’re the first to argue for sanctions against Russia or Iran, we’re the first to say that the structural funds that have helped economies in Eastern and Central Europe to be so successful, these are great things, but we never joined the European Union for an ever-integrating Europe, that’s not our path. It may be the path of some others. The eurozone countries: I believe they need to integrate more, in order to avoid the Greece of the future. That’s my view. I don’t want to stop them from doing that.

But in a nutshell it comes down to this. Is the European Union a flexible enough organisation so that it can include and work for eurozone members and non-eurozone members? That is the question. I believe the answer will be yes, but with my fellow heads of government and state we’ve got to prove that point, because that I think is the question that the British people will rightly be asking.

Time for one more? Gentleman over here.

Question

Thank you sir. Prime Minister, what would be your opposition of your government for inviting Montenegro to become next member of NATO after the end of this year?

Prime Minister

I think there’s a very strong case for Montenegro to be the next member of NATO. We supported that at the successful NATO conference we hosted in Cardiff in Wales, and I believe it will be a very big feature of the upcoming NATO discussions. I think the only point we would make is that, you know, NATO membership’s a very important move for a country, a very important set of obligations, and it needs to have the strongest possible domestic support; that when a country takes this step, the greater the political consensus and public consensus behind membership, the better.

If I think of my country we have parties of the left, parties of the right, and parties that want to pull out of Europe. Everyone agrees that NATO membership is a vital part of Britain’s national interest, that we’re a leading player in this organisation – as I said, the biggest defence budget for NATO in Europe. The greater consensus you can have about these things, the greater role your country will be able to play in NATO, and the greater support other members will be able to give you.

Can I thank you again for a very warm welcome. It’s been a really good discussion, and I wish you well for the rest of the conference. Thank you.

Updates to this page

-

Transcript of Q&A added.

-

First published.