Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020

Published 21 February 2015

Middle aged woman and older woman with photo album

Prime Minister’s foreword

Since I became Prime Minister, fighting dementia – and helping those living with the condition – has been a personal priority of mine.

The fall-out on people’s lives can be simply catastrophic. Those coping with dementia face the fear of an uncertain future; while those caring can see their loves ones slipping away.

Dementia also takes a huge toll on our health and care services. With the numbers of people with dementia expected to double in the next 30 years and predicted costs likely to treble to over £50 billion, we are facing one of the biggest global health and social care challenges - a challenge as big as those posed by cancer, heart disease and HIV/AIDs.

But though the challenge is great, I believe that with the expertise of our scientists, the compassion of our care workers, the stoicism of the British people – and with real political will – we can meet this challenge.

That’s why in March 2012 I launched a national challenge to fight dementia – an unprecedented programme of action to deliver sustained improvements in health and care, create dementia friendly communities, and boost dementia research.

Three years on and there has been significant progress – with more people now receiving a diagnosis of dementia than ever before, over 1 million people trained to be dementia friends to raise awareness in local communities, and over 400,000 of our NHS staff and over 100,000 social care staff trained in better supporting people with dementia. Our efforts on research have been world leading, with major research and infrastructure programmes now in place, supported by a doubling of research spending on dementia. We now spend well over £60 million on dementia research each year.

Now I want to see this work taken to the next level, building on all the brilliant work that’s been done in three short years.

By 2020 I want England to be:

- the best country in the world for dementia care and support and for people with dementia, their carers and families to live; and

- the best place in the world to undertake research into dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases.

As we look to the future, it is clear that we all have a part to play. This is not just about funding from Government, or research by scientists, but understanding and compassion from all of us. Together, we can transform dementia care, support and research.

David Cameron

Prime Minister

Executive summary

Cecil: a person living with dementia

We are working harder than ever to improve dementia care, to make England more understanding of dementia, to find out more about the condition and to find new treatments which delay onset, slow progression or even cure dementia.

There is still much more to be done as we look ahead to the next five years and the challenges that need to be tackled.

People with dementia have told us what is important to them. They want a society where they are able to say[footnote 1]:

-

I have personal choice and control over the decisions that affect me.

-

I know that services are designed around me, my needs and my carer’s needs.

-

I have support that helps me live my life.

-

I have the knowledge to get what I need.

-

I live in an enabling and supportive environment where I feel valued and understood.

-

I have a sense of belonging and of being a valued part of family, community and civic life.

-

I am confident my end of life wishes will be respected. I can expect a good death.

-

I know that there is research going on which will deliver a better life for people with dementia, and I know how I can contribute to it.

Informed by these outcomes, our vision is to create a society by 2020 where every person with dementia, and their carers and families, from all backgrounds, walks of life and in all parts of the country – people of different ages, gender, sexual orientation, ability or ethnicity for example, receive high quality, compassionate care from diagnosis through to end of life care. This applies to all care settings, whether home, hospital or care home. Where the best services and innovation currently delivered in some parts of the country are delivered everywhere so there is more consistency of access, care and standards and less variation. A society where kindness, care and dignity take precedence over structures or systems.

We want the person with dementia – alongside their carer and family to be at the heart of everything we do. Their wellbeing and quality of life must be uppermost in the minds of those commissioning and providing services. There needs to be greater recognition that everyone with dementia is an individual with specific and often differing needs including co-morbidities. Those with dementia and their carers should be fully involved in decisions, not only about their own care, but also in the commissioning and development of services.

More broadly, we want a society where the public thinks and feels differently about dementia, where there is less fear, stigma and discrimination; and more understanding.

We want people to be better informed about dementia and helped to take action, such as through lifestyle changes, to reduce their personal risk of developing the condition.

People want hope for the future, to know that real progress is being made towards preventing and treating dementia, and that there is a global effort to find a cure.

This document sets out the areas where the government believes it will be necessary for society to take sustained action in order to deliver this vision and to truly transform dementia care, support and research by 2020.

The government’s key aspirations are that by 2020 we would wish to see:

-

Improved public awareness and understanding of the factors, which increase the risk of developing dementia and how people can reduce their risk by living more healthily. This should include a new healthy ageing campaign and access to tools such as a personalised risk assessment calculator as part of the NHS Health Check.

-

In every part of the country people with dementia having equal access to diagnosis as for other conditions, with an expectation that the national average for an initial assessment should be 6 weeks following a referral from a GP (where clinically appropriate), and that no one should be waiting several months for an initial assessment of dementia.

-

GPs playing a leading role in ensuring coordination and continuity of care for people with dementia, as part of the existing commitment that from 1 April 2015 everyone will have access to a named GP with overall responsibility and oversight for their care.

-

Every person diagnosed with dementia having meaningful care following their diagnosis, which supports them and those around them, with meaningful care being in accordance with published National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Quality Standards. Effective metrics across the health and care system, including feedback from people with dementia and carers, will enable progress against the standards to be tracked and for information to made publicly available. This care may include for example:

-

receiving information on what post-diagnosis services are available locally and how these can be accessed, through for example an annual ‘information prescription’.

-

access to relevant advice and support to help and advise on what happens after a diagnosis and the support available through the journey.

-

carers of people with dementia being made aware of and offered the opportunity for respite, education, training, emotional and psychological support so that they feel able to cope with their caring responsibilities and to have a life alongside caring.

-

-

All NHS staff having received training on dementia appropriate to their role. Newly appointed healthcare assistants and social care support workers, including those providing care and support to people with dementia and their carers, having undergone training as part of the national implementation of the Care Certificate, with the Care Quality Commission asking for evidence of compliance with the Care Certificate as part of their inspection regime. An expectation that social care providers provide appropriate training to all other relevant staff.

-

All hospitals and care homes meeting agreed criteria to becoming a dementia friendly health and care setting.

-

Alzheimer’s Society delivering an additional 3 million Dementia Friends in England, with England leading the way in turning Dementia Friends in to a global movement including sharing its learning across the world and learning from others.

-

Over half of people living in areas that have been recognised as Dementia Friendly Communities, according to the guidance developed by Alzheimer’s Society working with the British Standards Institute[footnote 2]. Each area should be working towards the highest level of achievement under these standards, with a clear national recognition process to reward their progress when they achieve this. The recognition process will be supported by a solid national evidence base promoting the benefits of becoming dementia friendly.

-

All businesses encouraged and supported to become dementia friendly, with all industry sectors developing Dementia Friendly Charters and working with business leaders to make individual commitments (especially but not exclusively FTSE 500 companies). All employers with formal induction programmes invited to include dementia awareness training within these programmes.

-

National and local government taking a leadership role with all government departments and public sector organisations becoming dementia friendly and all tiers of local government being part of a local Dementia Action Alliance.

-

Dementia research as a career opportunity of choice with the UK being the best place for Dementia Research through a partnership between patients, researchers, funders and society.

-

Funding for dementia research on track to be doubled by 2025.

-

An international dementia institute established in England.

-

Increased investment in dementia research from the pharmaceutical, biotech devices and diagnostics sectors, including from small and medium enterprises (SMEs), supported by new partnerships between universities, research charities, the NHS and the private sector. This would bring word class facilities, infrastructure, drive capacity building and speed up discovery and implementation.

-

Cures or disease modifying therapies on track to exist by 2025, their development accelerated by an international framework for dementia research, enabling closer collaboration and cooperation between researchers on the use of research resources – including cohorts and databases around the world.

-

More research made readily available to inform effective service models and the development of an effective pathway to enable interventions to be implemented across the health and care sectors.

-

Open access to all public funded research publications, with other research funders being encouraged to do the same.

-

Increased numbers of people with dementia participating in research, with 25 per cent of people diagnosed with dementia registered on Join Dementia Research and 10 per cent participating in research, up from the current baseline of 4.5 per cent.

Why dementia remains a priority

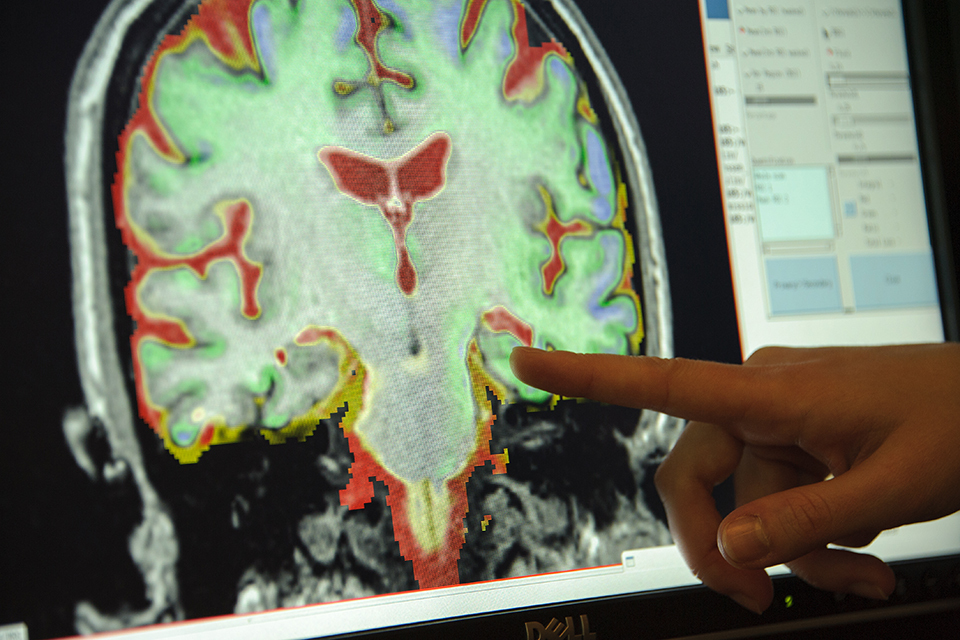

Scan of brain with alzheimers

What is dementia?

The term ‘dementia’ describes a set of symptoms that include loss of concentration and memory problems, mood and behaviour changes and problems with communicating and reasoning. These symptoms occur when the brain is damaged by certain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, a series of small strokes or other neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s Disease. Around 60 per cent of people with dementia have Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common type of dementia, around 20 per cent have vascular dementia, which results from problems with the blood supply to the brain and many people have a mixture of the two. There are other less commons forms of dementia,[footnote 3] for example dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia[footnote 4].

Throughout this document, dementia is used as shorthand for this broad range of conditions. It is important, however, to recognise that no two people with dementia or their carers are the same and individuals will have unique and differing needs.

Dementia is a progressive condition, which means that the symptoms become more severe over time. People with dementia and their families have to cope with changing abilities such as the capacity to make decisions about major life events as well as day-to-day situations.

The reality for many people with dementia is that they will have complex needs compounded by a range of co-morbidities. A recent survey by Alzheimer’s Society found that 72 per cent of respondents were living with another medical condition or disability as well as dementia. The range of conditions varied considerably, but the most common ones were arthritis, hearing problems, heart disease or a physical disability.[footnote 5]

Currently, dementia is not curable. However, medicines and other interventions can lessen symptoms for a period of time and people may live with their dementia for many years after diagnosis. There is also evidence that more can be done to delay the onset of dementia by reducing risk factors and living a healthier lifestyle.

Advanced dementia can be very difficult for the individual and their family and it is not always possible at this late stage of the condition to ‘live well’, but compassionate treatment, care and support throughout the progression of the condition is essential to enable people with dementia to one day ‘die well’. There is also a great deal that can be done to help people with dementia at earlier stages. If diagnosed in a timely way, people with dementia and their carers can receive the treatment, care and support (social, emotional and psychological, as well as pharmacological) to enable them to better manage the condition and its impact. For example, there is much that can be done to help prevent and ameliorate symptoms such as agitation, confusion and depression.

Brian Hennell was born in London in June 1938. In 1968 he married June and had three children. It was early in 2005 that Brian seemed to be changing, developing feelings of lesser wellbeing than he had had before. Mood swings and irrationality were noticed. At times he was irascible, unreasonable and unkind.

June suspected that the decline in Brian’s feel-good factor was linked to his failing memory. They couldn’t go on this way and, having run out of self-help options realized that the time had come to involve their GP.

In August 2008, June and Brian visited their GP who undertook simple tests on Brian. By late September 2008, a consultant old age physician was able to report, following a thorough examination, that in his opinion there was no underlying medical reason for Brian’s deteriorating condition and that he would benefit from referral to a memory clinic and the help of a consultant psychogeriatrician. He also ordered a CT head scan which showed nothing abnormal.

An initial assessment by a memory service followed a month later, but real progress was made when Brian was seen by the consultant psychogeriatrician.

June’s diary reflects that this was a massive turning point for them and that the specialist was wonderful. After a three-hour consultation he gave a probable diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, practical help such as advising about an Enduring Power of Attorney, considering their home arrangements, and whether downsizing to live nearer family may be wise.

Thanks to receiving a diagnosis, they could evaluate how to go forward. Having a diagnosis is really important for many reasons. It stops you worrying that something even more serious, like a brain tumour, is causing the problem. It provides some light at the end of the tunnel.

Next steps for the couple included:

- selling their large home of 26 years and downsizing to live near their two sons and their families in Gloucestershire, at their request, so that they would be on hand to provide help and support.

- making Enduring Powers of Attorney.

- informing the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) of Brian’s difficulties and receiving permission from them to keep driving for another year.

Not every day is wonderful and there are certainly some difficult times - but we are going forward, taking risks and living life to the full. There is still confusion and the need to make adjustments, to be flexible and learn. Of the future, we both agree that this is an unknown quantity. We work closely as volunteers with the NHS and many other organisations. Both Brian and June have given and received positive help from support groups.

Hello, I’m me! Living well with dementia, Chapter 30, June and Brian Hennell, Oxford University Press

The impact of dementia now and in the future

Dementia is a growing, global challenge. As the population ages, it has become one of the most important health and care issues facing the world. The number of people living with dementia worldwide today is estimated at 44 million people, set to almost double by 2030[footnote 6].

In England, it is estimated that around 676, 000 people have dementia[footnote 7]. Dementia has, and will continue to have, a huge impact on people living with the condition, their carers, families and society more generally as summarised below:

Mortality

- Dementia is now one of the top five underlying causes of death and one in three people who die after the age of 65 have dementia[footnote 8].

- Nearly two thirds of people with dementia are women, and dementia is a leading cause of death among women – higher than heart attack or stroke[footnote 9].

Prevalence

-

Dementia mainly affects older people, and after the age of 65, the likelihood of developing dementia roughly doubles every five years[footnote 10].

-

Estimating the prevalence of dementia in England is not an exact science. The Delphi approach is a consensus statement based on experts reviewing a series of international studies whereas the Cognitive Function and Ageing II Study (CFAS II) uses real data from three populations in England, allowing for more granular estimates of prevalence, for example at Clinical Commissioning Group level, and indicates that there are ranges.

-

Dementia can start before the age of 65, presenting different issues for the person affected, their carer and their family. People with young onset dementia are more likely to have active family responsibilities – such as children in education or dependent parents – and are more likely to need and want an active working life and income. Family members are more frequently in the position of becoming both the sole income earner, as well as trying to ensure that the person with young onset dementia is appropriately supported.

-

The number of people with dementia from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups in the UK is expected to rise significantly as the BAME population ages. It is estimated that there are nearly 25,000 people living with dementia from BAME backgrounds in England and Wales. This number is expected to grow to nearly 50,000 by 2026 and over 172,000 by 2051. This is nearly a seven-fold increase in 40 years. It compares to just over a two-fold increase in the number of people with dementia across the whole UK population in the same time period[footnote 11].

-

People with learning disabilities have an increased risk of developing dementia than other people and usually develop the condition at a younger age. This is particularly true of people with Down’s syndrome, one in three of whom will develop dementia in their 50s[footnote 12].

Fear

- People over the age of 55 years fear dementia more than any other disease[footnote 13].39 per cent of over 55s fear getting Alzheimer’s the most, compared to 25 per cent who worry most about cancer.

Care

- There are around 540,000 carers[footnote 14] of people with dementia in England [footnote 15]. It is estimated that one in three people will care for a person with dementia in their lifetime. Half of them are employed and it is estimated that 66,000 people have already cut their working hours to make time for caring while 50,000 have left work altogether.

Economy

- Dementia costs society an estimated £26 billion a year, more than the costs of cancer, heart disease or stroke [footnote 16].

- It is estimated that if there was a disease-modifying treatment from 2020 that delayed the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by 5 years, by 2035 there would be 425,000 fewer people with dementia, with accumulated savings from 2020 of around £100 billion[footnote 17].

- A recent study estimated that by 2030, dementia will cost companies more than £3 billion, with the numbers of people who will have left employment to care for people with dementia set to rise from 50,000 in 2014 to 83,100 in 2030. Yet if companies increased their employment rate of dementia carers by just 2 per cent over the years to 2030, for example by offering more flexible terms of employment, the retention of these skilled and experienced staff would deliver a saving of £415 million [footnote 18].

- Businesses have started to recognise this issue, with one in twelve companies (8 per cent) having made attempts to accommodate the needs of a member of staff with dementia, and more than half (52.1 per cent) considering taking such action in the future.

Hospital care

- People with dementia are sometimes in hospital for conditions for which, were it not for the presence of dementia, they would not need to be admitted. An estimated 25 percent of hospital beds are occupied by people with dementia[footnote 19].

- People admitted to hospital who also have dementia stay in hospital for longer, are more likely to be readmitted and more likely to die than patients without dementia who are admitted for the same reason[footnote 20].

Care homes and care at home

- An estimated one-third of people with dementia live in residential care and two-thirds live at home.

- Approximately 69 per cent of care home residents are currently estimated to have dementia[footnote 21].

- People with dementia living in a care home are more likely to go into hospital with avoidable conditions (such as urinary infections, dehydration and pressure sores) than similar people without dementia.

Loneliness

- The Alzheimer’s Society Dementia 2014 survey reported that 40 per cent of people with dementia felt lonely and 34 per cent do not feel part of their community [footnote 22]. There is a similar impact on the carer.

Progress on improving dementia care, support and research

Art classes for people with dementia

Since the launch of the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia[footnote 23] significant progress has been made in improving health and care for people with dementia and carers, creating dementia friendly communities, and boosting dementia research. The government has also initiated new work to lead international collaboration across the world to accelerate efforts to improve the treatment and care of those with dementia.

Improving health and care

-

Greater awareness of risk management and reduction:

Public Health England has a developing evidence base on risk reduction via publication of the Blackfriars Consensus[footnote 24]. There is agreement that this is an area where there should be a greater focus and public health action. There is some evidence that the effects of vascular dementia can be minimised or prevented altogether through a healthy lifestyle. Smoking and obesity, for example, affect many types of dementia, in particular vascular dementia.[footnote 25][footnote 26]

-

Improved diagnosis rates:

The government set the first ever national ambition on dementia diagnosis that two-thirds of the estimated number of people with dementia should receive a diagnosis and appropriate post-diagnosis support by March 2015 so that they can access the right care at the right time. In 2010/11 in England less than half (42 per cent) of those estimated to have dementia were being diagnosed. The latest figures show this has risen by 17 percentage points to 59 per cent.

-

Greater identification and referral of dementia in hospitals:

In the hospital setting, through NHS England’s Dementia Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) incentive[footnote 27] (mandatory from April 2013), with around 4,000 referrals a month, it is clear that more people with dementia in hospitals are being identified and assessed. Since April 2013 to November 2014 there have been 81,110 referrals as a result of the introduction of this CQUIN incentive.

-

More targeted inspection of dementia care in hospitals:

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) has committed to appointing a new national specialist adviser for dementia care. They will train inspectors across all inspecting teams to understand what good dementia care looks like so that their judgements are consistent and robust. These judgements will include a separate section in hospital inspection reports showing how well hospitals care for people living with dementia.

-

A better aware, educated and trained NHS and social care workforce:

Over 437,920 NHS staff have already received Tier 1 (foundation level) dementia training[footnote 28] and more than 100,000 social care workers have received dementia awareness training. The College of Social Work is producing good practice guidance for social workers to improve the contribution that they can make in achieving best outcomes for people with dementia and carers.

-

Supporting better provision of post-diagnosis support:

The government’s mandate to NHS England for 2015/16 includes a commitment to improve diagnosis, treatment and care for people with dementia[footnote 29]. This is supported by the government’s commitment that from 1 April 2015 everyone, including people with dementia, will be supported by a named GP with overall responsibility and oversight for their care. In February 2014 the Secretary of State for Health set out his ambition that everyone diagnosed with dementia should be offered high quality support after receiving a diagnosis of dementia. This may include personalised information, a dementia adviser, access to support services such as counselling and ongoing specialist care provided by specialist nurses. To support GPs and other primary care staff, an online Dementia Roadmap was launched in May 2014. The tool provides a framework that local areas can use to provide local information about dementia. It is aimed at assisting primary care staff to more effectively support people with dementia and their carers. People newly diagnosed with dementia and their carers are now able to sign up to a new email service on the NHS Choices website to get essential help and advice to support them to adjust to their recent diagnosis.

-

Greater support for provision of integrated care:

Councils and the NHS are now working with one another, and are encouraged to work with other partners including the independent and voluntary sectors, to provide better and more joined up care to local people through the £5.3 billion Better Care Fund. Around a quarter of the Better Care Fund plans highlight improving dementia care as one of their priorities, including for example providing local access to high quality post-diagnosis support.

-

Improving care and support through the National Dementia Action Alliance:

Leading organisations and groups from across health and social care have come together to provide collective leadership and commitment to act to improve the quality of life for people affected by dementia. Since the Alliance was established in 2010, the number of member organisations has increased from 40 to 150[footnote 30]. The Alliance has been leading the way in delivering change across health and social care, for example on improving hospital care for people with dementia, support for carers and each organisation has made its own commitment towards becoming more dementia friendly.

-

Investment in dementia friendly hospitals and care homes:

£50 million has been invested in the creation of dementia friendly environments in hospitals and care homes. The projects have now been completed and evaluated, with the key findings being issued in guidance to the service in the spring.

-

Greater support for carers:

£400 million has been provided between 2011 and 2015 so that carers can take breaks and the government has introduced significant legislative changes to better support carers, who for the first time will have the right to an assessment of their eligible needs[footnote 31].

-

Increased transparency of information to drive service improvement:

In November 2013, the government published the Dementia State of the Nation interactive maps, which for the first time allowed the public to enter their postcode to see how local dementia services in their area were performing and to view the performance of dementia services across the country. Additional dementia information is also available on the MyNHS website, which is a new comparison website tool that allows health and social care organisations to see how their services compare with those of others.[footnote 32]

Dementia Friendly Communities

-

Creation of a more dementia friendly society:

Public Health England and Alzheimer’s Society launched a major TV and online campaign in May 2014, with the aim of getting one million Dementia Friends by March 2015. A Dementia Friend learns what it is like to live with dementia and then turns that understanding into action – for example, by giving time to a local service such as a dementia café or by raising awareness among colleagues, friends and family about the condition. Since then we have recruited over 1 million Dementia Friends and pledges have been made by corporate partners, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and public sector organisations to continue to deliver more Friends[footnote 33].

-

More dementia friendly communities:

With help from Alzheimer’s Society, we now have 82 communities across England signed up to the national Dementia Friendly Communities recognition process, exceeding the original ambition in the Prime Minister’s Challenge of 20 by March 2015. These are communities that are working to help people live well with dementia.

-

Building a dementia friendly generation:

With the support of Alzheimer’s Society and their ambassador Angela Rippon, younger people are more educated and aware about dementia than ever before. Hundreds of schools have taken part in the dementia friendly schools programme and awareness is gathering pace within youth movements around the country.

-

Action by businesses and industry:

Businesses and industry have provided strong support for the Dementia Friends campaign, with major employers such as Marks & Spencer, Asda, Argos, Homebase, EasyJet, Aviva and Lloyds Banking Group committing to creating Dementia Friends from among their staff. A number of sectors have led the way to become dementia friendly by developing their own charters, for example the Dementia Friendly Financial Services Charter published in 2013[footnote 34] and the Technology Charter launched in June 2014[footnote 35].

Better research

-

World leading, major programmes of research and significant investment in infrastructure:

We have doubled research spending on dementia since 2009/10 from £28.2m to £60.2m in 2013/14, and are well on track to achieve the target of £66m for 2014/15. This investment includes major research on issues that matter to people with dementia and their carers, such as the world’s largest – £20 million - social science research programme on dementia. It also includes Dementias Platform UK (DPUK), a £53 million public private partnership led by the Medical Research Council. The DPUK’s aims are early detection, improved treatment and ultimately, prevention, of dementias.

-

The UK is a key player in the European Union (EU) Joint Programme - Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND)[footnote 36]:

This is the most coherent international activity in dementia research with a research strategy agreed by 28 countries, reaching beyond Europe. UK scientists are well connected with international programmes, such as JPND, Centres of Excellence in Neurodegeneration (COEN)[footnote 37] and the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)[footnote 38]. UK scientists are at the centre of current efforts to harmonise and accelerate research at the global level. The UK is also leading the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia Consortium (EPAD) which is focused on creating a novel environment for testing interventions targeted at delaying onset of clinical symptoms or progression in dementia.

-

The increasing role of the charity sector:

The charity sector is becoming ever more active in galvanising public awareness and support for dementia research. Alzheimer’s Research UK announced a £100 million research pledge campaign. Alzheimer’s Society has also committed to spend at least £10 million annually for the next decade on dementia research.

-

Expansion of the dementia research workforce:

We have invested significantly in expanding the dementia research workforce, via National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training for medical researchers, and via a new scheme led by the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health and Care (CLAHRCs), to train nurses, social care and allied health professionals to become dementia researchers. Alzheimer’s Society has also funded a major network of Doctoral Training Centres across the UK. The establishment of research infrastructures as part of DPUK, such as in imaging, stem cell modelling and informatics, as well as long term support through Medical Research Council (MRC) Units, will provide a foundation for attracting basic scientists and bioinformaticians into the area and help grow capability.

-

Greater participation of people with dementia in research:

The number of people with dementia involved in studies in 2012/13 was 11,859 (3.7 per cent); the forecast figure for 2013/14 was 13,583 (4.5 per cent), more than ever before. 2013/14 was also a record year in terms of the number of NHS Trusts involved in dementia research (200) and the performance of dementia studies, with over 85 per cent completing on time. ‘Join Dementia Research’ has been launched by the NIHR, Alzheimer’s Research UK and Alzheimer’s Society to increase the numbers of people participating in research. This allows patients, carers, public and professionals to sign up and take part in high quality studies in dementia research.

-

Increased research in care homes:

Much needed research in care homes has been advanced through NIHR Enabling Research in Care Homes (ENRICH), a network of over 1000 research enabled care homes.

Global action against dementia

-

Leading international collaboration across the world:

Following the first G8 Dementia Summit in December 2013, the UK has been leading international efforts to fight dementia. A series of follow up events have taken place across the G7 to support progress on the commitments, which were agreed upon at the G8 Summit. In June 2014, the international community gathered in London to discuss finance and social impact investment. In September 2014, Canada and France jointly hosted an event focused on ways to improve collaboration between academia and industry. In November 2014, Japan hosted an event focused on innovation in care and prevention. In February 2015, a final legacy event was held in the US, focusing on research. On 16 - 17 March 2015, the World Health Organization will be hosting their first Ministerial Dementia Conference. The event will review the progress that has been made under UK leadership and seek to expand future work beyond the G7.

-

Establishment of the first World Dementia Envoy and World Dementia Council:

On 28 February 2014, the Prime Minister appointed Dr Dennis Gillings as the first World Dementia Envoy. Dr Gillings has since created a World Dementia Council[footnote 39] to provide global leadership on the key dementia challenges and the council currently has 18 members from a number of countries, representing a wide range of expertise and disciplines, including a person living with dementia.

-

Action to accelerate progress on dementia research and the development of possible drugs:

On 2 December 2014, it was announced in the Autumn Statement that the UK government plans to invest £15 million in a public-private fund to stimulate and increase investment in dementia research and to progress the development of possible drugs to treat dementia.

-

World leading collaboration with regulators:

Following the Prime Minister’s call for an active response to the challenge of drug development and the use of accelerated regulatory pathways, the government has been working with Raj Long of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to nurture a strong, close and frank relationship with regulators. The UK is leading global efforts to bring together regulators in order to accelerate drug discovery and development. Regulators have now, for the first time, formed a working group to come together and tackle the challenges involved in developing dementia drugs.

-

Launch of the first Global Alzheimer’s and Dementia Action Alliance:

In May 2014, the launch of the Global Alzheimer’s and Dementia Action Alliance (GADAA) brought an important civic dimension into the Global Action Against Dementia work[footnote 40]. It seeks to enhance global efforts to reduce stigma, exclusion and fear about dementia, and to harness the power of those with dementia, their carers and the wider community.

-

Bolstering the human rights of those living with dementia:

The UN Independent Expert on the Human Rights of Older People, Rosa Kornfield-Matte, has demonstrated her commitment to the programme. The government is exploring ways that we can work with her in order to bolster international commitments to the human rights of those living with dementia.

-

Developing international standards of care for dementia:

We are developing globally recognised standards reflective of different care systems, with a focus on outcomes for the individual. This will be achieved through global collaboration and shared learning. Sustaining and improving care delivery mechanisms for dementia is an international priority.

-

The EU Joint Action on Dementia 2015-18:

The Joint Action will focus on specific areas of the dementia system: diagnosis and post-diagnostic support; crisis and care coordination; the quality of care in residential care settings; and dementia friendly communities. The majority of the Joint Action will focus on testing evidence of best practice in localities to enhance understanding of how change and improvement in dementia services can be taken forward in practice.

Transforming dementia care, support and research by 2020

Patient in a care home with a carer

To achieve our vision, both supporting those who are currently affected by dementia, and looking at how we can improve the health of the population in to the future so we can minimise the number of people developing dementia, we need to look critically at where we’ve come from and where we need to be by 2020.

Improving health and care

Risk management and reduction

We now have a developing evidence base on risk reduction and a consensus that this is an area where there should be a greater focus and public health action. Messages on prevention are, however, sometimes contradictory and can be confusing to the general public. It is important that clearer and better targeted information is provided to people in mid-life about how they can reduce their personal risk of dementia. Public Health England’s strategy for the next five years identifies reducing the risk of dementia, its incidence and prevalence in 65-75 years, as one of seven key priorities[footnote 41]. This includes action over the next 18 months to support people to live healthier lives and manage pre-existing conditions that increase their risk of dementia, such as depression or diabetes.

Peterborough City Council set out to ensure that during an NHS Health Check people identified at risk of, or diagnosed with dementia, were connected with the services they required.

In September 2014 estimates suggested Peterborough had over 1,000 people living with dementia in the community with only 45% of them having been actually diagnosed. The Peterborough public health team identified a significant gap in knowledge across health and social care professionals, regarding the potential for lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of developing vascular dementia.

The NHS Health Check provided an opportunity to promote Peterborough’s investment in dementia services, including a new Dementia Resource Centre. It also provided a platform for addressing the knowledge and skills gap among professionals.

A GP referral pathway from the NHS Health Check to relevant dementia services was developed for people with concerns around memory loss. This includes signposting to the Dementia Resource Centre, which provides access to advice and information from the Alzheimer’s Society, assessment and diagnosis from Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust (CPFT) NHS Memory Clinic and post diagnostic support groups and activities for both people with dementia and their carers and loved ones.

Practices are being supported in implementing the dementia component to the NHS Health Check through a clinical coach (Coronary Heart Disease clinical nurse lead) employed by Peterborough’s Public Health department. During 2013/14 dementia awareness raising, as part of the NHS Health Check, made up 25% of the total number of the NHS Health Checks delivered.

By 2020 we would wish to see:

-

Improved public awareness and understanding of the factors, which increase the risk of developing dementia and how people can reduce their risk by living more healthily. This should include a new healthy ageing campaign and access to tools such as a personalised risk assessment calculator as part of the NHS Health Check.

-

A developed global consensus that risk reduction is a key means through which the global burden of dementia can be reduced. As such, risk reduction will play a central role in public health policies and campaigns and non-communicable disease actions plans around the world.

Improving diagnosis

The NHS is making a national effort to increase the proportion of people with dementia who are able to get a formal diagnosis, from under half, to two-thirds of people affected or more. The objective for the NHS is to continue to make measurable progress towards achieving this in 2015/16 [^42]. This includes ensuring timely diagnosis and the best available treatments for everyone who needs them, including support for carers.

Breaking down the stigma of dementia is important and encouraging diagnosis and post-diagnosis support closer to a patient’s home can shorten the time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis.

It is encouraging that the number of people receiving a diagnosis of dementia has steadily increased, that there is a greater awareness of the benefits of diagnosis both by individuals and clinicians, and that different models of diagnosis are being utilised for people at all stages of the condition; for example, diagnosis being undertaken in-drop in clinics in primary care settings, without the need for a referral from a GP.

The South Manchester Memory Service is based on the Gnosall model where a memory specialist spends a session in a local GP practice in South Manchester. The initiative has been very well received by patients and their families and has facilitated the early referral and diagnosis of people with dementia who otherwise would not have been seen. Referrals can be more easily directed toward the appropriate specialist within the memory service and the diagnosis can be made in primary care. In addition, by examining carefully the coding of memory problems, the numbers of patients with a diagnosis of dementia can be increased.

This is consistent with the Five Year Forward View[footnote 43] for the NHS, which sets out a clear direction for the NHS moving towards, in the future, new models of integrated care. This means far more care delivered locally through greater joint working between health and social care, but with some services in specialist centres, organised to support people with multiple conditions, not just single diseases. This is particularly relevant for people with dementia who often have a range of other conditions or co-morbidities alongside their dementia. To ensure that services are truly integrated around the needs of people, future models will expand the leadership of primary care to include nurses, therapists and other community based professionals. These models will also harness the critical contribution of volunteers, for example in helping to reach out to seldom heard groups to improve access to services.

Within this context, there are a number of challenges we need to address in the future including improving information on the prevalence of dementia at both national and local level, supporting Clinical Commissioning Groups to reduce unwarranted variation across the country both with regard to diagnosis rates and waiting times for assessments through to diagnosis and with regard to the latter, in particular, improving the diagnosis of dementia for people of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic origin and other seldom heard groups, for whom the evidence shows diagnosis rates are particularly poor.

Connecting Communities is an Alzheimer’s Society project that sees volunteers from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds designing and delivering awareness raising activities that are culturally appropriate for their communities.

Many different communities are represented in London with different cultural perspectives on volunteering, dementia and local support services. This project is addressing recognised issues around BAME groups’ engagement with dementia care services, including:

- low awareness of dementia in BAME communities.

- low numbers of people accessing early intervention dementia services and instead engaging with support at a crisis point.

- the diversity of local volunteers who are not reflective of local populations.

This project is working to influence London-wide dementia service commissioning and set a standard for volunteering good practice.

There are real opportunities to improve our understanding of the way dementia affects local communities, including identifying and supporting more people with dementia in a timely way, for example by harnessing the knowledge and experience of those regularly working with older people in the community. This spans wider than the pivotal role of GPs, for example to practice nurses, district nurses, health visitors, paramedics, pharmacists, audiologists, optometrists, podiatrists, home care workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social care staff and voluntary organisations.

By 2020 we would wish to see:

-

In every part of the country people with dementia having equal access to diagnosis as for other conditions, with an expectation that the national average for an initial assessment should be 6 weeks following a referral from a GP (where clinically appropriate), and that no one should be waiting several months for an initial assessment of dementia.

-

All Clinical Commissioning Groups and Local Health and Wellbeing Boards having access to improved data regarding the prevalence of dementia at local and national level and using this data to inform the commissioning and provision of services so that more people with dementia receive a timely diagnosis and appropriate post-diagnosis support.

-

An increase in the numbers of people of black, Asian and minority ethnic origin and other seldom heard groups who receive a diagnosis of dementia, enabled through greater use by health professionals of diagnostic tools that are linguistically or culturally appropriate.

-

The UK playing a key role in advancing care and support for people with dementia, through Scotland’s leadership of the EU Joint Action on Dementia.

Support after diagnosis

There is greater awareness now about the importance of support after diagnosis often termed ‘post-diagnosis support’, both for improving the individual’s quality of life and for the potential to reduce more costly crisis care, for example by avoiding emergency admissions to hospitals and support in care homes. There is also a greater understanding about the broad array of services and support that this may include, for example information about available services and sources of support; an appropriate adviser or care co-ordinator such as a Dementia Adviser to provide advice and facilitate easier access to relevant care; Cognitive Stimulation Therapy as a treatment for people with mild to moderate dementia, Admiral Nurses and others to provide specialist support to families.

Social action solutions such as peer support and befriending services can also provide practical and emotional support to people with dementia and carers, reduce isolation and prevent crisis. The impact of these interventions is being robustly tested so that evidence on the most effective interventions can be disseminated.

Mr Brook is a 73 year old man and he lives with his wife, who is also his carer. Before he visited the local Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Adviser he was not sure where to go for help and admitted feeling concerned. He wanted some more information about dementia but also about his legal rights. Mr Brook and his Dementia Adviser discussed his diagnosis, general health and care needs as well as some of his background and general interests for about two hours. The Dementia Adviser recommended the couple attend the local dementia café for more information about dementia and the adviser agreed to continue to provide support.

Mr Brook was interested in more information about a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) so the adviser gave them a copy of the form so they could see what was involved. Mr Brook agreed that the information the adviser provided was relevant, easy to understand and had helped him and his wife access services both within the Society and externally. Mr Brook also felt listened to, involved and encouraged to make decisions by the adviser.

Mr Brook felt the two things that he valued most about the Dementia Adviser service were the provision of information about dementia and the emotional support he received. In his own words Mr Brook wrote about the service:

I always feel better in myself after the adviser has left because after discussing things with her, her explaining, her help and understanding makes me feel better in myself that day.

Excellent post-diagnosis support is being provided in some parts of the country. The challenge now is to reduce unwarranted variation and to make those services available everywhere, and to ensure that they meet the specific needs of local communities. In order to make this happen, there needs to be a better awareness by local health and social care commissioners of what services are required and which are already being provided for example by the voluntary and independent sector. At national level there needs to be better dissemination of best practice and what works including the effectiveness of different types of post-diagnosis support, the cost-benefits and how to deliver these services in practice.

The Greenwich Advanced Dementia Service, part of Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust, is helping people in the borough remain in their own homes for longer by supporting carers to increase their resilience. The service was developed by nurses and doctors working in Oxleas with partners from the Royal Borough of Greenwich, Alzheimer’s Society, Greenwich Carers Centre, GPs and community health services. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients by enabling them to live in their own home with their loved ones, minimise unnecessary emergency admissions to hospital, and provide a comprehensive package of community-based support for people with dementia and their families.

Before the service was developed, people with advanced dementia tended to be cared for in a care home, often spending time in hospital. To date Greenwich Advanced Dementia Service has supported over 100 people to live and die in their own homes and is saving up to £265,000 a year on reduced care home costs and hospital admissions.

In general, 30 per cent of local acute hospital beds are occupied by people with dementia who usually have longer admissions than others. Members of the team made urgent visits to 75 per cent of patients as an alternative to A&E, and acute hospital admission. Over one year, nine patients experienced some form of crisis, requiring urgent home visits from the service. These would otherwise have been A&E admissions.

People’s experience of living with dementia or caring is significantly determined by characteristics such as their ethnicity, age, pre-existing disabilities or whether they have a carer living with them. Local commissioners and providers need to continue to improve their understanding of the best ways to tailor post-diagnosis support services to diverse needs. For example there is evidence that shows that BAME communities in particular have lower rates of access to these services.

Looking to the future, we wish to encourage greater personalisation in the provision of post-diagnosis services – this means building support around the individual with dementia, their carer and family and providing them with more choice, control and flexibility in the way they receive care and support – regardless of the setting in which they receive it.

Homecare provider Somerset Care has spent a number of years developing a service, known as PETALS. This service focuses on six key features: Person-centred, Empowerment, Trust, Activities, Life History and Stimulation.

The service places the individual and their family at the centre of the support package. This includes creating individual life stories, working with families to produce a memory box, maintaining daily living skills, regular leisure opportunities, inclusive mealtimes and creative use of activities to stimulate and motivate the person with dementia when they are on their own. As a result the service can help to ensure people using the PETALS service feel involved in their care, remain independent and active at home, are left with meaningful activities once staff leave, and are supported by a small dedicated team who are flexible to their needs.

The Care Act 2014 provides a new legislative focus on personalisation by putting personal budgets into law for the first time, increasing opportunities for greater choice, control and independence.

In addition, the government recognises that for many individuals an integrated budget containing both their health and social care funding would be very beneficial. To this end, NHS England has launched the Integrated Personal Commissioning programme (the IPC)[footnote 44]. The first wave of the IPC will run for three years and will be aimed at four groups of individuals. One of these focus groups will be people with multiple long term conditions, particularly the frail elderly and we anticipate that this will include some individuals with a dementia diagnosis.

By 2020 we would wish to see:

-

GPs playing a leading role in ensuring coordination and continuity of care for people with dementia, as part of the existing commitment that from 1 April 2015 everyone will have access to a named GP with overall responsibility and oversight for their care.

-

Every person diagnosed with dementia having meaningful care following their diagnosis, which supports them and those around them, with meaningful care being in accordance with published National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Quality Standards. Effective metrics across the health and care system, including feedback from people with dementia and carers, will enable progress against the standards to be tracked and for information to made publicly available. This care may include for example:

-

receiving information on what post-diagnosis services are available locally and how these can be accessed, through for example an annual ‘information prescription’.

-

access to relevant advice and support to help and advise on what happens after a diagnosis and the support available through the journey.

-

carers of people with dementia being made aware of and offered the opportunity for respite, education, training, emotional and psychological support so that they feel able to cope with their caring responsibilities and to have a life alongside caring.

-

-

Every newly diagnosed person with dementia and their carer receiving information on what research opportunities are available and how they can access these through ‘Join Dementia Research’.

Supporting carers

The Care Act 2014 in many respects marks a quiet revolution in our attitudes towards carers. For the first time carers are recognised in the law in the same way as those they care for. Under the Care Act 2014, local authorities have a responsibility to assess carer’s eligible needs for support. This will mean more carers, including carers of people with dementia, are able to have an assessment, comparable to the right of the people they care for, and a support plan setting out how their needs will be met. This is supported by NHS England’s Commitment to Carers, which offers carers a health check, information and support[footnote 45].

Carers of people with dementia undoubtedly provide a vital role and we know that the availability of appropriate care and support and the quality of services has a significant bearing on whether carers feel able to take a break from their caring responsibilities[footnote 46].

Sophie, 27, put her career on hold when her much loved gran was diagnosed with vascular dementia. They’d always been very close when she was growing up and Sophie wanted to be there for her. Having just completed a university degree she decided to become a full time carer to her gran.

Sophie said:

Gran lived in her own house but started to neglect everything and began to have falls. She was very aware that things weren’t right but didn’t want to go into a home. I came back from university to look after her – she’d always been there for me when I was younger. At first it involved a lot of prompting her to do things – to get dressed, to wash. If she could still do it herself I would encourage her to, but her condition slowly deteriorated and it became impossible for me to leave the house. She couldn’t understand how things worked - she’d put a pan on the hob and forget about it. She was confused and scared and would wander off outside. I had to have eyes at the back of my head!

It became a 24-hour job, seven days a week caring for Gran. In the end, after caring for her for one-and-a-half years, I just couldn’t cope and it became too much for Gran as well. She went into residential care in 2011 – it was such a difficult decision, it broke my heart. It was a big transition for her because she had to change her routine but she’s settled now. I’m now training to be a dementia nurse. – Gran would be proud if she understood.

There is evidence that providing carers with better information, training and coping strategies, including emotional and psychological support, improves their quality of life and is also cost-effective, with costs being off-set by reduced use of services[footnote 47].

Looking to the future, we believe it is important that commissioners consider how they can improve the supply and quality of appropriate support services for carers, for example respite services, including inviting and acting on feedback from carers about services.

There is evidence that providing support to carers of people with dementia in an informal rather than medicalised setting can reduce perceived stigma and that the voluntary and community sector is well placed to facilitate this environment[footnote 48]. These providers can also tap into and share the expertise of carers, for example by facilitating social action interventions such as peer support or mentoring.

Carers should be made aware of and offered the opportunity for training to help meet the emotional and practical demands of caring and also to help them gain the skills they need to cope with balancing their caring responsibilities with employment. Involving carers in the training of health and care professionals is also important.

Dudley now has three dementia gateways with a team of seven dementia advisors as well as specialist dementia nurses who are based in the local gateway day care centres. Support for carers is a priority. For every person diagnosed with dementia the service aims to assess the needs of their carers and provide them with a number of programmes aimed at supporting them through information provision, advice, sign posting and educating. Every carer is offered an education programme including information on what dementia is; how it impacts on individuals; and what strategies a carer can develop. Linked to the programme is the expert patient programme, and centres also offer short term respite care to allow carers to attend. In the mid to later stages of dementia, where people are likely to have more complex needs, the centre offers a range of activities and opportunities aimed at developing and maintaining existing skills as well as potential new skills, through to helping people with end of life care support.

There should also be greater recognition by health and care professionals that if a person with dementia has a carer, the carer is a full partner and should be fully involved in decision making. Use of models such as for example the ‘Triangle of Care’ provide a useful framework[footnote 49].

By 2020 we would wish to see:

-

Carers of people with dementia being made aware of and offered the opportunity for respite, education, training, emotional and psychological support so that they feel able to cope with their caring responsibilities and to have a life alongside caring.

-

More employers having carer friendly policies and practice enabling more carers to continue working and caring.

Care at home

A YouGov poll for Alzheimer’s Society (June 2014) found that 85 per cent of people would want to stay at home for as long as possible if diagnosed with dementia, rather than go into a care or nursing home. Changes of environment can be particularly unsettling for people living with dementia[footnote 50].

Homecare workers provide a growing range of vital care and support services to enable people to live well with dementia in their own homes, including personal care, administration of medication and more general support.

In a relatively short period of time, dementia care in the home has progressed significantly, and continues to evolve as a result of improved training methods, new technology and a wider understanding of what the condition entails.

There should be greater recognition by commissioners across health and care services of the value of homecare services, both for those that receive them and in reducing more costly crisis care.

We want to see greater provision of innovative and high quality dementia care at home, delivered in a way that is personalised and appropriate to the specific needs of the person with dementia, their family and carers. This requires greater efforts in making working in homecare an attractive profession and enabling a degree of freedom and flexibility to allow providers to incorporate new ideas including technology solutions into everyday practice.

Trinity Homecare, a live-in care specialist, believes care continuity is a key aspect of creating a person-centred approach to dementia care. They create their rotas to ensure that the same carers remain with the same person they are caring for over an extended period of time. This allows the carer and the person using the service to develop a close bond and trust. This also helps the carer to build a connection to the likes, dislikes, history and feelings of the person they are sharing a home with. This can be a significant advantage in developing a care package which is focused upon each individual and creates an environment for the person living with dementia that they are most familiar and comfortable with.

There is a real opportunity for closer working between local dementia leads and homecare providers and housing staff, who are able to build a close understanding of the individual they work with, in spotting the early signs of dementia and helping to refer individuals for assessment.

We also want to see greater information and support for people with dementia to access housing options which meet their care and lifestyle needs, including appropriate support to remain in the home of their choice. For example, as set out in the recent Memorandum of Understanding with the housing sector[footnote 51], health, social care and housing services working together to plan for homes and communities that people can live out their lives in such as greater provision of ‘specialist’ housing available for those who need more support, including sheltered and extra care housing, with staff trained in dementia care.

By 2020 we would wish to see:

- Increased numbers of people with dementia being able to live longer in their own homes when it is in their interests to do so, with a greater focus on independent living.

Care in hospitals and care homes

While many hospitals and care homes offer excellent support, some are not doing enough to provide high quality, personalised care that helps individuals to live as fulfilling a life as possible. This is evidenced by the Care Quality Commission’s (CQC) review of dementia care involving the inspection of a sample of care homes and hospitals across England, looking at people’s experiences of dementia care as they move between care homes and hospitals[footnote 52].

While overall CQC found more good care, delivered by committed, skilled and dedicated staff than poor, in the care homes and hospitals they visited, the quality of care for people with dementia varied greatly.

Key areas highlighted for improvement included assessments, which in some hospitals and care homes did not comprehensively identify all of a person’s care needs; aspects of variable or poor care regarding how the care met people’s mental health, emotional and social needs; and variable or poor care regarding a lack of understanding and knowledge of dementia care by staff including GPs, community nurses and district nurses.

To improve staff awareness and understanding of the needs of patients with dementia in hospital, Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust have piloted the Butterfly Scheme.

Developed by a carer, The Butterfly Scheme is aimed at improving the wellbeing of people with dementia during their time spent in hospital. The scheme trains staff to offer a positive and appropriate response to people with memory impairment and provides staff with a simple, practical strategy for meeting their needs.

When a patient or carer opts in to this scheme, the patient is given a discreet butterfly symbol prompting all staff to follow a special response plan. Family and friends are invited to fill in a carer sheet, offering insight so that staff have greater information to ensure that the patient is cared for and supported in best way possible in line with their individual needs.

The scheme has been adopted by over a hundred hospitals who have found that it has helped their staff to care for patients in a more dementia-friendly way.

Wherever possible, we want to avoid people with dementia having to go into hospital through better local provision of community services, education and training. When people are admitted, we want them to receive high quality, compassionate care and to be discharged in a timely and appropriate way so that they can continue to live at home or in community settings.

Outside of the hospital setting, we want more care providers including care homes to take tangible action to improve the experience and care of people with dementia and their families, including greater use of evidence-based training for staff and greater participation in research.

There is an opportunity created by the Better Care Fund, for the NHS and Social Care to work together to develop new models of in-reach support, including for example medical reviews, medication reviews and rehabilitation services. This means care homes engaging and involving the wider community to improve their support for people with dementia, including GPs and healthcare professionals, with the aim of improving quality of life and reducing inappropriate admission to hospital. We also want to see more care homes helping people with dementia to remain active and engaged, with regular opportunities for social interaction and activities focused on the individual.

The Otto Schiff care home in Golders Green is run by Jewish Care and has 54 residents, most of whom have dementia.

Residents’ and carers’ needs are met by specialist, trained staff and great emphasis is placed on strong links between residents and the wider community, including encouraging many different people from the local community to participate in activities. These include arts-based activities, music, singing, gardening, cooking, films and laughter yoga. The community centre is beside the care home and local groups are encouraged to use its facilities. For example it hosts activities such as Yiddish and art classes.

The Disability and Dementia Services Manager has said:

‘There are about 30 official volunteers at the moment who come in for groups, discussions, exercise, singalongs, befriending and other things. There is also a great amount of cross-generational activity.’

Local synagogues run services in the home, including a special service dedicated for people with dementia. The home also welcomes visits from a mother and toddler group and those arranged by local schools.

‘Local community members feel this is a two-way thing - not only is it beneficial for the people living in the home, but children also get to learn, see a different environment and meet older people.’

‘The aim is to break down the sense of isolation that people in homes can feel.’

‘It is important that many of the people who come along live in the community rather than in the home. This helps to destigmatise and address people’s preconceptions about living in a care home. We often hear remarks from them about how nice the place is - it’s really reassuring for people.’

By 2020 we would wish to see:

-

All hospitals and care homes meeting agreed criteria to becoming a dementia-friendly health and care setting.

-

Fewer people with dementia being inappropriately admitted to hospital as an emergency through better provision of support in community settings, which enables people to live independently for longer.

-

More research being conducted in, and disseminated through, care homes, and a majority of care homes signed up to the NIHR ENRICH ‘Research Ready Care Home Network’

Reducing the inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medication

A particular issue affecting people with dementia is the inappropriate use of antipsychotic medication, normally in response to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Antipsychotic drugs should only be prescribed to people with dementia in exceptional circumstances and if prescribed, this should be reviewed on a regular basis.

Significant progress has been made reducing the use of these drugs in England. The NHS Information Centre’s 2012 audit of antipsychotic prescriptions for people with dementia found that antipsychotic prescriptions for people with dementia had reduced by 52 per cent between 2008 and 2011[footnote 53]. The government is committed to continuing to monitor the level of prescribing of antipsychotic medication and regional variation, with the aim of maintaining and supporting a further reduction in inappropriate prescribing.

There must be continuing action at a local level in England to ensure antipsychotic drugs are not used as a first resort, but that person-centred responses are used in initial responses to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, also referred to as behaviours that challenge. If these behaviours are better understood and treated earlier they have the potential to reduce admissions to hospitals and care homes as the most challenging behaviours are often the result of other issues. For example, untreated urinary tract infections, which can lead to delirium, untreated pain, lack of understanding of cognitive capacity, poor nutrition and hydration, poor communication, lack of knowledge about the person’s history, poor general care, boredom and unmet emotional needs. Getting this right could mean an end to inappropriate antipsychotic prescribing and unnecessary use of physical restraint.

Home Instead has developed a City and Guilds accredited dementia training programme for its caregivers. The programme teaches innovative techniques for dealing with dementia. Rather than focus on the symptoms and treatments of the condition, caregivers are trained in effective techniques for managing the many different and sometimes challenging behaviours associated with dementia including refusal, delusions, aggression, false accusations, wandering and agitation. A key outcome is that caregivers learn to respect the person with dementia as an individual and how to tailor care to their specific needs.

By 2020 we would wish to see:

-

A continued significant reduction in the inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia and less variation across the country in prescribing levels.

-

All relevant health and care staff who care for people with dementia being educated about why challenging behaviours can occur and how to most effectively manage these.

-

When the person’s needs are complex, that there is skilled assessment and care available so that the person is not disabled or harmed by inappropriate care or prescribed inappropriate medication.

End of life care

Early conversations with people with dementia are important so that people can plan ahead for their future care, including palliative and end of life care. Care co-ordinators can play a central role in this ensuring that people with dementia at the end of life get the right care at the right time and are able to die in the place of their choosing.

Mrs S was resident in a care home. It became clear that she was nearing the end of her life. The care home worked together with the GP and Mrs S’s daughter to support her to remain in the care home up to the point of her death. Her daughter was allowed to stay with her through the night, and was able to interact with her mother, brushing her hair and having physical contact. There were pleasant things for her to see and smell, such as photos of her husband and fresh flowers. Mrs S’s Christian faith was also respected, and the care home agreed to hymns playing in the background. Her daughter said “it was actually better than going to a hospice because the staff had grown very fond of Mum and they did take the best care of her and she didn’t have the disruption of having to go out of somewhere that she was familiar with, so she was surrounded by familiar sights and sounds and smells

For more information see My Life until the End: Dying Well with Dementia (Alzheimer’s Society)

There are examples of best practice around the country, but more needs to done to ensure all areas offer high quality end of life care for people with dementia. We know that too many people with dementia are not supported to have early discussions and make plans for their end of life care [footnote 54]. This means difficult, emotional decisions are often made in crisis and the wishes of the person with dementia, including for example where they want to die, cannot be taken into account.

By 2020 we would wish to see

-

All people with a diagnosis of dementia being given the opportunity for advanced care planning early in the course of their illness, including plans for end of life.

-

All people with dementia and their carers receiving co-ordinated, compassionate and person-centred care towards and at the end of life including access to high quality palliative care from health and social care staff trained in dementia and end of life, as well as bereavement support for carers.

-

A right to stay for relatives when a person with dementia is nearing the end of their life, either in hospital or in the care home.

Dementia education, training and workforce

People with dementia and their carers interact with a wide range of health and care professionals and other care workers. It is vital that these staff understand the complexity of the condition, what it means to be a carer of a person with dementia and are able to provide high quality care because this is fundamental to improving quality of life.